R James Healy

CFPR Editions / 20 GOTO 10

Artists who span subject disciplines and cross-disciplinary boundaries are rarer than one might imagine. Most artists tend to remain in the area they know. R. James Healy is one of those rare artists who has transcended traditional boundaries. His current work encompasses 3D printing, sculpture, and animation – a digital narrative from a lifetime in the film industry, plus a love of physically making an aesthetically pleasing object.

Healy’s training was in computer animation. A graduate of the National Centre of Computer Animation, he contributes to major visual effects studios worldwide.

Converting from 3D rendering in films and animation to 3D printed Zoetropes has led him to his current sequential sculpture, which explores the theme of time. To create a 3D printed object that does not look like it is 3D printed, one needs a wide range of skills and an innate knowledge of one’s discipline.

The idea that one pushes a button to create an exact facsimile is far from reality. Firstly, the ability to think in 3D and mentally conceive internal and external spaces while drawing complex shapes is required.

Secondly, a comprehensive familiarity with 3D drawing software, a constantly changing landscape of commercial software and freeware with numerous add-ons, all of which do something slightly different.

Lastly, understanding how the software transcribes from a screen rendering to physical output is not so easy given the vast proliferation of different 3D printers, each presenting different materials and printing processes. Most importantly, one has to consider the printing material to create an appealing appearance.

In Healy’s case, the extra narrative dimension creates a sequential series of physical objects with a coherent and understandable story. James has drawn upon his many years in the film and animation industry, which shows in his work.

Professor Stephen Hoskins Centre for Print Research

20 GOTO 10

My practice began in visual effects animation. Over time I began to miss the experience of working with real physical artworks. This led me to create 3D zoetropes.

A zoetrope is a pre-cinema animation device invented in the 1830s. It’s a slotted cylinder containing a sequence of images. The viewer spins the cylinder and looks through the slots. The slots function as a strobe, presenting the images as animation.

My zoetropes replace the 2D animation sequence with 3D printed objects. As the work evolved, I began to use 3D printing for other elements. The slotted cylinders, lamps and internal mechanisms were all fabricated this way.

A 3D zoetrope has many considerations. Together they form a cohesive experience. The residency at the Centre for Print Research provided a platform for me to explore 3D printing as the sole medium. For this artwork I condensed my artistic practice to focus on a static sculpture.

As a visual artist I am preoccupied with perception. We experience the world through our senses, but we cannot always trust them. I know that the animation strip inside a zoetrope is a sequence of static images, but viewed through the spinning slots I perceive motion. My brain is playing tricks on me.

Screen animation and 3D zoetropes function using the same principles, but the experience of each is quite different. I began to wonder what other means of perceiving motion I could explore. When developing an animated sequence, it is conventional practice to create a storyboard. Its panels relay the major action. When reading a storyboard, the viewer experiences the passage of time in their head. They don’t see it, but they understand it. I find this fascinating and wanted to explore the phenomena as a physical artwork.

81 x 61 x 61 cm /

32 x 24 x 24 in (zoetrope)

25 x 36 x 36 cm /

10 x 14 x 14 in (lamp)

“As a visual artist I am preoccupied with perception. We experience the world through our senses, but we cannot always trust them.”

Oposite: Made in Strathcona. 3D printed zoetrope by R James Healy.

My artistic practice involves time as a medium, but has never addressed it as a topic. My perception of time has changed throughout my life. It feels to have sped up, but of course it hasn’t. I know this because we can measure it. Take that measurement away and things start to unravel.

Time is linear, it only moves forward. The future becomes the present, which in turn becomes the past, but our experience of time is cyclical. Day follows night always. It’s why analogue clocks are round. Reflecting upon this I concluded that a sculpture about time should be circular.

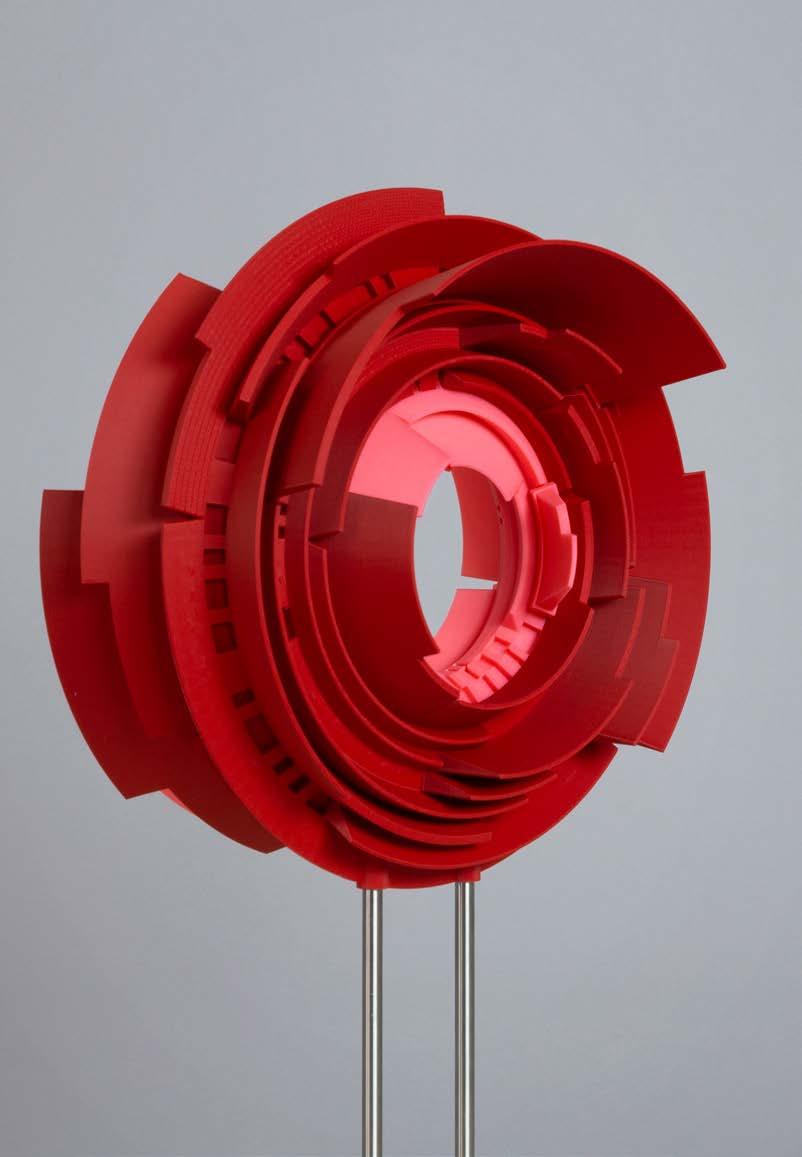

Outside of measurement, time in the future is imagined. The past is memory. The older we are the more memories we have. Some memories are clear and ever present, others are vague, but when considered become clearer. The fins of the sculptures represent memories. There are too many to count, yet they don’t come close to what’s in our heads. There’s also a scattering of holes. Those moments are lost forever.

Two colours were a practical requirement of the artwork. The sculptures were printed in coloured plastic, which limited the available palette to the manufacturers range. The precise geometrical form of the sculptures has a mechanical aesthetic. I selected red and pink to provide a visceral human quality. The red is a deep blood hue, the bright pink provides a tonal contrast. The sample swatch reminded me of caricatures of the human brain, which felt appropriate as it’s where our construct of time occurs.

The title 20 GOTO 10 is a common line of code in 8-bit computer programming. The command returns program flow to line 10, repeating it indefinitely. I selected this title to acknowledge the computational elements of the work. It also infers the endless repetition of time.

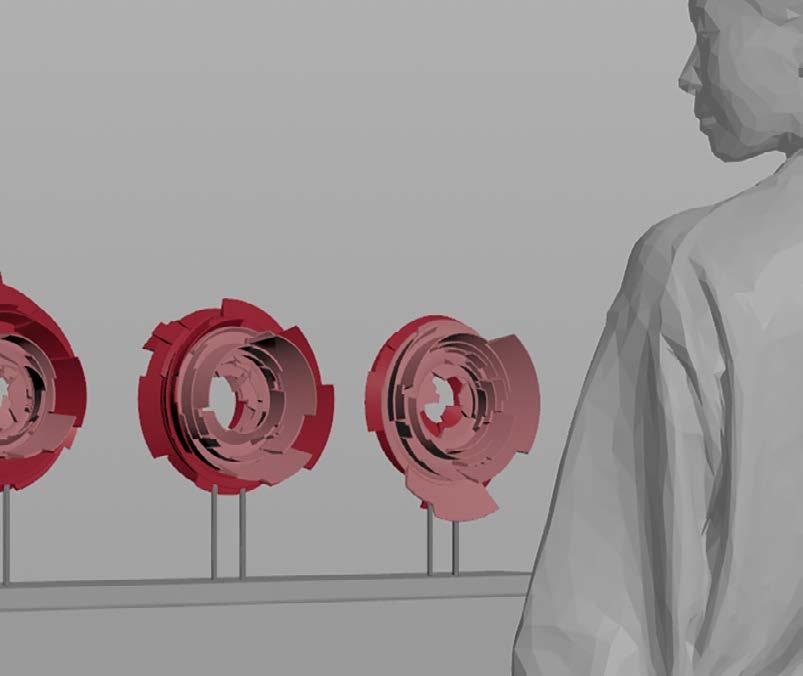

Below: 20 GOTO 10 scale concept. SideFX Houdini viewport render.

20 GOTO 10 was developed digitally using SideFX Houdini software. The completed files were executed in PLA on a Bambu Lab X1 Carbon 3D printer.

Houdini is a 3D animation package used in the visual effects industry. It’s used to create simulations for film and TV sequences and provides a node based (flowchart) programming environment for modelling and animation.

Prior to becoming a sequential sculpture, 20 GOTO 10 is an animation. Each sculpture in the sequence is a freeze-frame from that animation. There are five sculptures (frames) taken at equal intervals from a 120 frame sequence.

The aesthetics of static sculpture are not the same as moving image. I developed a setup within Houdini which allowed me to visualise both together, enabling me to fine tune the animation to accommodate the requirements of sculpture.

Each sculpture in the sequence is a torus, has two colours and approximately 100 fins. Their form and animation is complex. It’s not practical to manage the design or motion of such complexity by hand. Instead, I generate it algorithmically via a set of rules. Here’s an example of such rules in pseudo code:

1. Make a torus.

2. Split the torus into twenty rings.

3. Split each ring into five elements.

4. Extrude a fin from each element.

5. Randomly scale each fin.

“The aesthetics of static sculpture are not the same as moving image.”

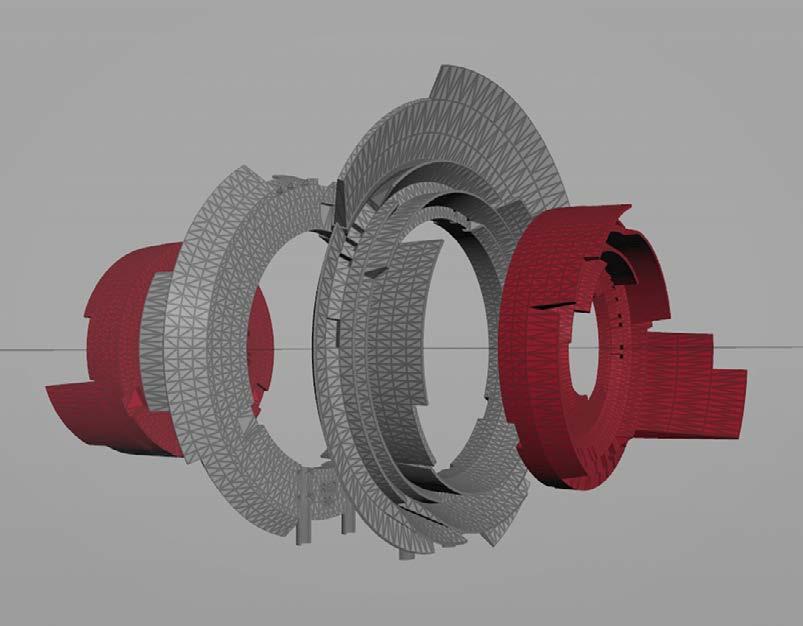

Opposite: SideFX Houdini viewport renders showing various parameter (rule) settings.

When the digital design of an object is complete, it must be prepared for printing. The Bambu Lab X1 Carbon is an FDM (Fused Deposition Modeling) printer. It prints thin layers of plastic (0.12 mm high) from the bottom upwards.

This methodology has limitations. Some objects cannot be printed in the orientation they were designed. For example: the capital letter “Y” can be printed from the bottom upwards. The two angled arms that diverge from the stem are self supporting. The capital letter “T” cannot be printed this way. The horizontal crossbar has nothing to support it. The solution is to print it upside down. That way the print bed supports the crossbar and the stem supports itself.

It’s often necessary to cut an object into components to achieve the desired orientation. Once printed they’re reassembled as designed. 20 GOTO 10 was no exception.

20 GOTO 10 is a sequence. For practical reasons I had to make a choice about how long that sequence would be. I reasoned that three was the shortest, fewer than that is a pair and fewer than that is not a sequence at all.

Conventional animation is developed as a series of keyframes. They’re the extremes of a movement. In-betweens help the viewer make the connection between these keyframes. Adding in-betweens to my sequence expanded it to a count of five. This was a manageable sequence quantity and provided a clean read.

I did not approach this artwork with a preconceived notion of what it should be, but I had developed a brief. 20 GOTO 10 is a 3D printed sequential sculpture exploring the theme of time. I began by exploring concepts of growth to evoke the passage of time. Each sculpture grew as it progressed through the sequence, but the eye is drawn to the largest, final silhouette. It made a linear sequence with a conclusion. To keep the sequence alive, I needed a loop.

A loop requires the start and end to be the same. With only five steps this limited change to the silhouette, so I examined the object’s surface. I made one side black and the other white and then experimented with ways of swapping them. I settled on a torus with a sliding surface. This is more easily described as a doughnut with a hole in the centre. The doughnut has icing on one side. The icing swaps sides by sliding through the hole.

To continue the doughnut analogy: there are five doughnuts in the sequence. The first doughnut has icing on the left. The last doughnut has icing on the right. The icing changes sides over the sequence. A viewer experiences the doughnut as a loop because they never know which side the icing started on.

Opposite: Exploded 3D mesh showing the four print components of 20 GOTO 10 sculpture #3. SideFX Houdini viewport render.

Below: Initial sketch exploring a growth sequence. Marker pen & digital.

“The variety of scale means that closer viewing reveals more detail.”

A crucial principle of 220 GOTO 10 is that the viewer creates the motion in their mind. They may enter the sequence at any point, free to move forwards or backwards. Unlike moving images, they have the opportunity to study a single static element. For this reason, the sculptures must work as a sequence and individually. I created interest around each sculpture by extruding fins perpendicular to the torus. Regardless of viewing position, there are fins pointing towards, away and in-between. The variety of scale means that closer viewing reveals more detail.

The quantity is such that the viewer does not pick out individuals. The exceptions are the five hero fins. They are larger and draw the eye. They guide the viewer’s eye around each sculpture and along the sequence. They create an imbalance when a sculpture is viewed alone, but cohesion when viewed as a group.

20 GOTO 10 has two colours. To date my works have been 3D printed in grey, then finished with airbrushed acrylic, providing a wide range of colour and specular options. That approach wouldn’t work here as the quantity of surfaces and angles make it impractical. The solution was to print the sculpture in two different coloured plastics.

The Bambu Lab X1 Carbon is designed to print up to five materials. But the process is overly time consuming and difficult to troubleshoot. I prefer to print each colour separately. This requires the digital sculpture to be prepared accordingly. Material separation and print orientation do not relate to the aesthetics as they are technical requirements. Depending on the step in the sequence, 20 GOTO 10 was designed in two or four components. These were printed in the relevant material and then assembled. The five sculptures are created from a total of 16 individual prints.

Opposite: 20 GOTO 10 sculpture #5 (detail). 3D printed PLA.