The People’s Shed: a collaborative arts project

Evelyn Broderick and A Radical Imagination Residency

The People’s Shed: a collaborative arts project

Evelyn Broderick and A Radical Imagination Residency

The People’s Shed: a collaborative arts project

Siobhán Geoghegan

In April 2022 Evelyn Broderick’s proposal, The People’s Shed, was awarded the community based residency A Radical Imagination.1 Since it was established The People’s Shed provided a common space that offered the simplicity and anonymity of printing with wood, writing with stencils, assembling and carving wood, sculptural seating, playing music, singing, conversations and collective blanket making. However, The People’s Shed generated more than activities or making. This vital gathering and safe space brought local people together in studio 468, Rialto and across Inchicore in community spaces creating ‘caring imaginaries’ where connections were made and the regenerative bonds of support and care, mutuality, endurance, patience, friendships and alliances were developed. The commons and care are evidenced in Evelyn’s socially-engaged practice and were

central to The People’s Shed.2 In the Shed we witnessed and recognised a new commonage and a generous sharing of a tradition that utilises its informality, creates an equality of sharing and listening and offers the power of the collective. The musician Fintan Vallely remind us in his paper that the commons are a heritage that demands care.3 This was evidenced throughout The People’s Shed where many acts of care and conversation took place over 18 months. These gatherings were explicitly and implicitly grounded in the reciprocal interchange of knowledge between traditional Irish music, visual arts and community development practices.

In this publication Aoife Granville writes about Victor Turner’s term ‘communitas’, a space that fosters a special kind of community spirit and togetherness that is both temporary and heightened.4 Evelyn and the groups she engaged with held that spirit, through events, seasonal marking and working together. They were present to each other without the act of consumption and anchored a rich connection to The People’s Shed, where a warm and welcome atmosphere created deep relationships that live beyond Evelyn’s residency. As Emma Mahony also writes, The People’s Shed and Evelyn offered and unravelled an abundance of social wealth positioning itself in opposition to the current reign of carelessness that we witness across the globe. It challenges the forms of possessive individualism exacerbated during Covid and offers us all instead resource sharing and community building.

Common Ground’s work is energised by staying true to the local. Recently, we were forwarded The Care Manifesto, 5 by artist Seoídin O’Sullivan whom we have

previously worked with. The manifesto identifies and recognises that putting care centre stage means recognising and embracing our interdependencies. Seoídin felt the manifesto spoke to our work as an arts organisation and how our work has emerged over the last 10 years.

In Common Ground we hoped that A Radical Imagination as a public call would consider and augment the labours of care by many community, voluntary groups, activists and artists that go into repairing and reimagining our communities. It was also our commitment as an arts organisation to stitch care into our work and practice.

We prioritise applying hope and care to all our relationships alongside acts of allyship6 and resistance. It is important to validate and celebrate the labours of care that go into repairing and creatively responding to and supporting our communities. Our work as an arts organisation, with the artists, groups and activists we work with, is dedicated to that. The community and neighbourhoods where we work are continually adjusting to physical and social change. Consequently making space for the arts and creative activities is critical for community connectedness.

For the last 25 years we have formed relationships and partnerships with artists and communities of place and interest, responding and working through collective processes that respond and speak to issues of spatial and social justice, communities of care, housing development, climate change, ecology and the urban environment, and more recently, to the impact of Covid-19. Making art is a response to those ever-present realities. We recognise how our practice, approach and current projects mirror the

following text from The Care Manifesto:

‘the care of activists in constructing libraries of things, co-operative alternatives and solidarity economies, and the political policies that keep housing costs down, slash fossil fuel use and expand green spaces. Care is our individual and common ability to provide the political, social, material, and emotional conditions that allow the vast majority of people and living creatures on this planet to thrive – along with the planet itself’.7

Critically, throughout the last 15 years, through the recession and throughout Covid-19 we have found mutual local supports and alliances that are essential to maintaining, expanding and augmenting our work with artists and community groups. We are reminded that we have to act in solidarity with each other. They also inspire, extend and ultimately critique our interdisciplinary practices, influencing how we connect to communities in and beyond Dublin 8.

In our neighbourhoods many community spaces have been dismantled and closed, libraries, community centres, small inclusive spaces of immense value. This has had an enormous impact on many of the groups we work with. We know that now more than ever, people and communities need safe social spaces where they can gather and create. We would like to propose that we all adopt The People’s Shed manifesto as a part of daily life,

The People’s Shed is a place to:

Share skills

Celebrate culture

Talk about what’s going on in the area

Discuss needs and wants

What we need is:

A quiet place to share skills and stories

An inclusive space

A place where everyone looks out for each other

1 A Radical Imagination 2022 – 2024 was a community based residency awarded by Common Ground that built on The Just City Counter Narrative Neighbourhood award 2020 – 2022. A Radical Imagination offered collaborative or socially engaged artists/arts collective/community partners an opportunity to be based in Dublin. The timing of the award also marks when Dublin 8, the area in which Common Ground works and is located continues to experience multiple changes to its urban and social fabric as we navigated our way through a pandemic. studio 468 is programmed by Common Ground in partnership with the Rialto Development Association since 1999. studio 468 receives funding to support artists from the Arts Council and Dublin City Council.

2 S. Stavrides (2016) Common Space: The City as Commons, Zed Books Ltd, London UK. Pg. 3-2.

3 F. Vallely, Playing, paying and preying: cultural clash and paradox in the traditional music commonage, Community Development Journal Vol 49 No S1 January 2014 pp. i53 –i67

4 V. Turner, (1969) Liminality and Communitas in The Ritual Process: Structure and AntiStructure. Aldine Publishing, Chicago.

5 5 Collective, C 2020, The Care Manifesto: The Politics of Interdependence. Verso.

6 Ng, W., Ware, S. M., & Greenberg, A. (2017). Activating Diversity and Inclusion: A Blueprint for APRIL 2 Museum Educators as Allies and Change Makers. Journal of Museum Education, 42(2), 142 – 154

7 Collective, C 2020, The Care Manifesto: The Politics of Interdependence. Verso.

Dr Aoife Granville

Lá áirithe go dtugas cuairt ar stiúdeó 468 i Rialtó, bhíos ag súil i dtreo an fhoirgneamh nuair a chuala comhrá agus staraíocht mnáibh ag druidim im’ threo. Ar mo ghabháil dom níos congaraí don ndoras, thosnaigh amhránaíocht binn álainn laistigh. Sa tseomra fhéin, do bhí slua mhaith mnáibh bailithe timpeall, gléasta go slachtmhar le dathanna geala bríomhara agus iad suite go gealgáireach ag éisteacht leis an t-amhránaí gleoite. An t-atmasféar, an spiorad agus an meas a bhí sa tseomra sin –d’fhan sé liom ó shin. B’é seo Seid na nDaoine.

Níl aon dabht fé ach gur chruthaigh an t-ealaíontóir Evelyn Broderick pobal eisceachtúil i stiúdeó 468 i Rialto. Pobal lán de spioraid, cruthaitheacht, gean agus an cuma air go raibh na h-éinne ana-chompórdach lena chéile i spás aoibheann oscailte a chruthaigh Evelyn sa duthaigh i stiúdeó 468 i gcomhar

On one of the occasions that I visited Evelyn in studio 468 in Rialto, as I walked towards the building, I could already hear the laughter and chitter-chatter coming from The People’s Shed. As I got to the door, the singing, sweet and beautiful began. Inside the room, a good crowd of women were gathered around, dressed beautifully and they sitting smiling and listening to the singer. The atmosphere, the affection and the respect in the room has stayed with me. That was The People’s Shed.

There is no doubt that Evelyn Broderick created an exceptional community in The People’s Shed in studio 468 in Rialto. A spirited and creative community and one where everyone seemed to me to be completely at ease with one another in an open space created by Evelyn during her residency in studio 468, with Common Ground. While there

le Common Ground. Cé go raibh béim ar a bheith ag déanamh blaincéidí agus ábhar eile

sa spás fhéin, bhí béim níos mó fiú ar a bheith ann i gcomhluadar compórdach daoine eile. Ní rabhas ach cúpla neomat ann sula raibh muga tae is briosca im’ lámh agus suíochán tugtha dom. Bhí beirt im’ aice, duine acu ag cabhrú leis an nduine eile leis an cniotáil agus cáirdeas álainn eatarthu. D’fhoghlaimíos mar gheall orthu ábhairín agus d’insíodar liom mar gheall ar an bpobal áitúil, monarchan fúáile a bhíodh timpeall agus taibhsí fiú amháin. Bhí ana-chomhrá againn.

Do stad an comhrá ar feadh cúpla neomat nuair a thosnaigh amhránaí eile sa chiorcal. An uair seo, amhrán spleodrach greannmhar mar gheall ar ‘bhan- garda’ is taispeántas thar a bheith fuinnúil ag an amhránaí. Idir gáire agus gol a bhíomar ar fad is sinn ag éisteacht.

was emphasis on making and creating blankets and other garments and objects, I felt there was more emphasis on just being there together in the space. I was only there a couple of minutes before I had a mug of tea and biscuit in my hand and space was made for me to sit. There were two lovely ladies beside me, one helping the other with her knitting. A lovely friendship between them. I learned about them a little, about the area, the sewing factories and even some ghosts! We had a lovely conversation.

The space fell silent for a few minutes when we had another singer in the circle. This time, a lively, hilarious ditty about a ‘BanGarda’, sung with gusto and verve. We were in stitches. Some of the ladies quietly continued their making as the song unfolded, others were completely focused on the singer. I always feel it is so natural for song to break out when

Do lean cuid dos na mnáibh leis an cniotáil is an déanamh ach cuid againn dírithe go hiomlán ar an dtaispeántas ceoil. Braithim fhéin go bhfuil bua na hamhráin spleodracha ag muintir Bhaile Átha Cliath agus go nádúrtha tosnaíonn na hamhráin in aon ciorcal pobail nuair a bhíonn an t-atmasféar i gceart. Sa Seid, bhí an t-atmasféar sin amhlaidh. Beidh spásanna mar seo níos tabhachtaí ná riamh ag imeacht ar aghaidh sa saol is na seana-spásanna a bhí againn chun bailiú ag dul i léigh is ag athrú go mór. Ní bhíonn spásanna séimh mar seo, spásanna chun cruthaitheachta (ceol agus ceird) chomh comónta is a bhíodh agus cheart dúinn ar fad aire a thabhairt dóibh. Tuigeann Evelyn go maith an tábhacht seo, gan dabht. Braithim saibhreas an traidisiún in Evelyn, ina chuid saothar, a chuid ceoil agus an cur chuige álainn atá aici. De shíolra muintir

the circle and space are comfortable and as a Kerry woman, I am always admittedly jealous of the wonderful, limitless repertoire of songs from Dublin. There was a lovely atmosphere in the Shed that morning – one which certainly invited song and stories. These sorts of spaces will become increasingly important going forward and I know that Evelyn certainly understands this. The spaces which were open to singing and meeting are getting fewer and have changed considerably. The gentle spaces which makes creativity in craft and music possible – we need to mind them.

I really feel the richness of our traditions when I talk to Evelyn. Tradition impacts her work, her music and her lovely approach. As one of the musical Broderick family from Galway, this comes as no surprise. Evelyn is a wonderful flute player and she has been

Broderick na Gaillimhe is ea í agus ní haon ionadh sin. Fliúiteadóir den scoth agus duine go bhfuil a shaol caite aici i gciorcail idirghlúine an cheoil traidisiúnta. Tá an tionchar sin le feiscint go mór sa chur chuige atá ag Evelyn i measc an pobal seo. Tionchar leis ag a seanamhuintir ar an ndearca a bhí ag Evelyn le linn an togra seo i Common Ground – ó láithreacht an bórd cistine, an soláthar leanúnach tae is brioscaí go dtí an fáilte croíúil a chuir sí roimh na héinne a shiúil isteach thar tairseach an dorais. Bhraitheas compórdach ón gcéad lá a chuas thairis an tairseach sin. Lúann sí tionchar a sheanmháthair go mór sa chaint. Mar a thárlaíonn sé bhí tionchar ana-mhór ag sean uncail le Evelyn ar mo chuid ceoil ar mo cheol fhéin go háirithe nuair a bhíos ag fás aníos. Duine de laochra an cheoil traidisiúnta ab ea Vincent Broderick agus scéalta álainn cloiste

surrounded in traditional music community since a young age, a community which prides itself on intergenerational communication and understanding. I feel that this influence on Evelyn was really clear especially in terms of how she undertook the residency. She spoke of her family quite a lot and the influence of her grandmother in particular and this influence is visible, from the central placing of the kitchen table, the continuous supply of tea and biscuits to the fabulous hearty welcome given to everyone who passes over the threshold and into the shed. I felt immediately comfortable there from the first minute I entered. As it happens, Evelyn’s grand-uncle Vincent, was an early musical influence on my own flute playing. His picture placed in prime position in the Shed, overlooking all of the activity, reminded me of some of his beautiful

agam faoí. A phictúir crochta sa chistin sa Seid ag féachaint ar an gceardaíocht ar fad. Bhí an cruthaitheacht go smior i Vincent leis agus é aitheanta mar dhuine dos na cumadóirí ceoil is fearr sa traidisiún leis. Is deas an cruthaitheacht sin a fheiscint teacht síos tríd na glúinte. Tá traidisiún fada bainteach le meitheal bhan ag teacht le chéile chun obair láimhe ar nós fíodóireacht, cniotáil agus lás a dhéanamh. Cá bhfios cé chomh fada siar is a théann sé dáiríre. Deineann sé ciail go mbailíodh mná le chéile ag ceirdíocht, ag caidiríl agus ag togaint briseadh ó chúrsaí eile an tí nuair a bhí deis acu. Tá aireachas agus rithim ar leith bainteach leis an saghas ceardaíocht seo chomh maith gan dabht, b’fhéidir gur bhraith ár sinsear sin níos fearr ná sinne. Sa Seid na nDaoine i Rialto bhraitheas go raibh aireachas bainteach leis an saothar do ana chuid dos

compositions. Vincent is seen as one of the finest composers in the tradition and I have heard lovely stories about him over the years. It is wonderful to see the creativity and approach passing down through the generations.

There is a long tradition of people, especially women, gathering together to craft, to sew, knit, embroider and make lace. Who knows how far back the tradition actually goes. It makes sense that women gathered to craft, to chat, to take a break from other housework when they did get the chance. There is a rhythm and mindfulness attached to such crafts of course as well and perhaps our ancestors understood that a lot better than us. In The People’s Shed I really felt that mindfulness in the making process for everyone gathered. While some chatted, others worked quietly on blankets, others knitted and

na mnáibh a bhí bailithe le chéile. Fhad is a bhí an caint ar siúl, bhí daoine ag cniotáil is ag fíodóireacht leo agus rithim álainn sa tseomra dá bhárr. D’aithin Evelyn tábhacht na ceardaíochta is í ag cur an togra seo chun cinn. Sa chiorcal neamhfhoirmeálta sa Seid na nDaoine i Rialto, bhraitheas ceangal speisialta ann – idir na mnáibh ar fad agus Evelyn agus bhraitheas fáilte ar leith uathu ar fad ar mo chuairt. Scriobh an antraipeolaí cáilúil Victor Turner mar gheall ar ‘communitas’ – nuair bhíonn spiorad speisialta pobail i gceist ar feadh tamall. Tárlaíonn sé le linn ócáidí ar leith, tréimhsí ar leith agus i spásanna ar leith go mbíonn spiorad pobail speisialta árdaithe idir dhaoine – sin a bhraitheas a bhí i gceist sa Seid na nDaoine.1

Chuaigh na cuimhní a bhí deartha ar na fallaí go mór i bhfeidhm orm – cuimhní

there was a beautiful rhythm and calmness in that space which was quite special. Evelyn fully understood the significance and potential impact of crafting when she began this project.

In the informal circle at The People’s Shed in Rialto, I felt a very special connection there – between the women gathered and Evelyn and I felt a really warm welcome there too. The renowned anthropologist, Victor Turner wrote prolifically about ‘communitas’. He described it as a special kind of community spirit and togetherness which was temporary and heightened. It happens, as he suggested, in particular spaces, during specific events and at certain times of the year. I felt I understood exactly what Turner spoke of when I experienced The People’s Shed.1

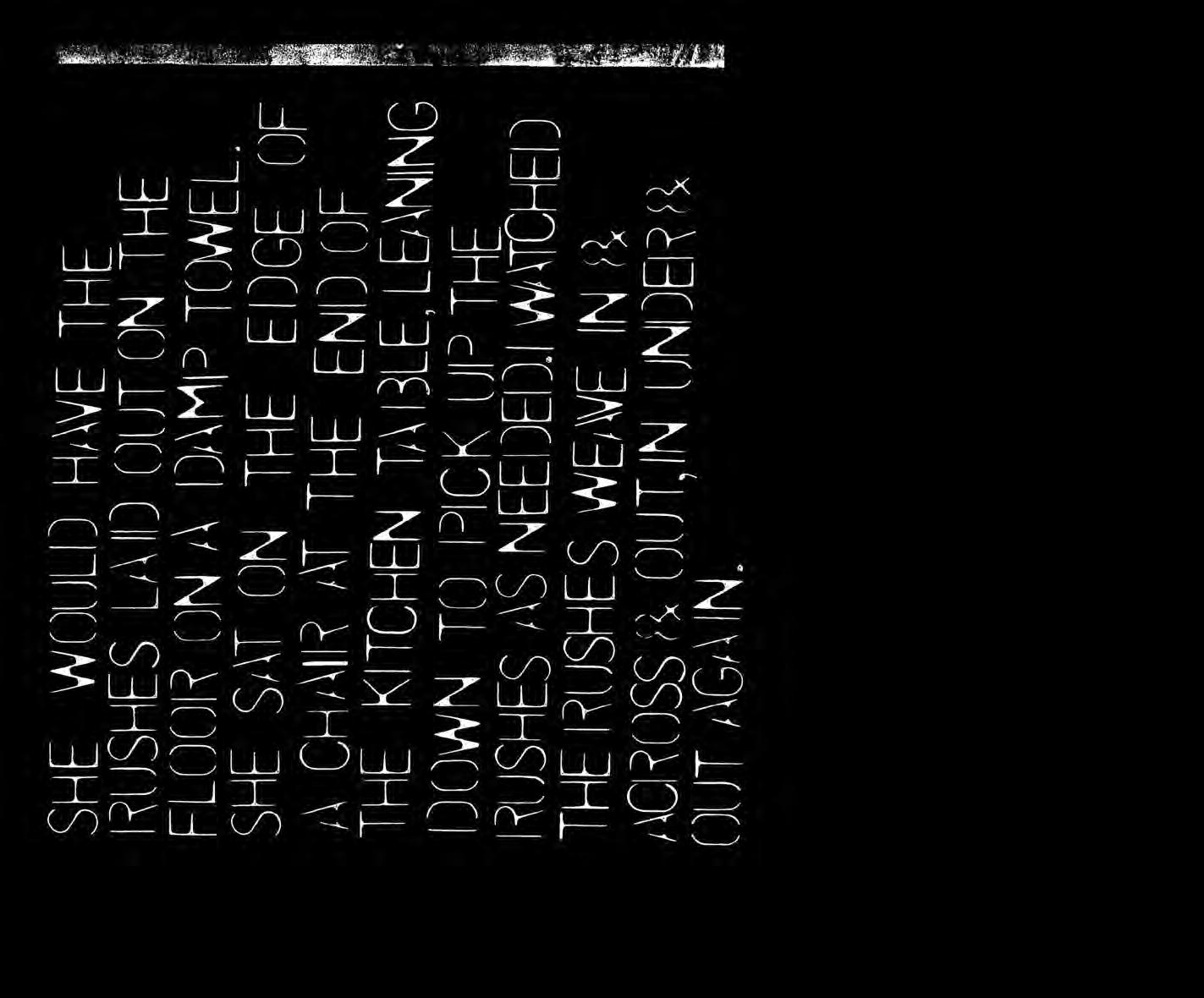

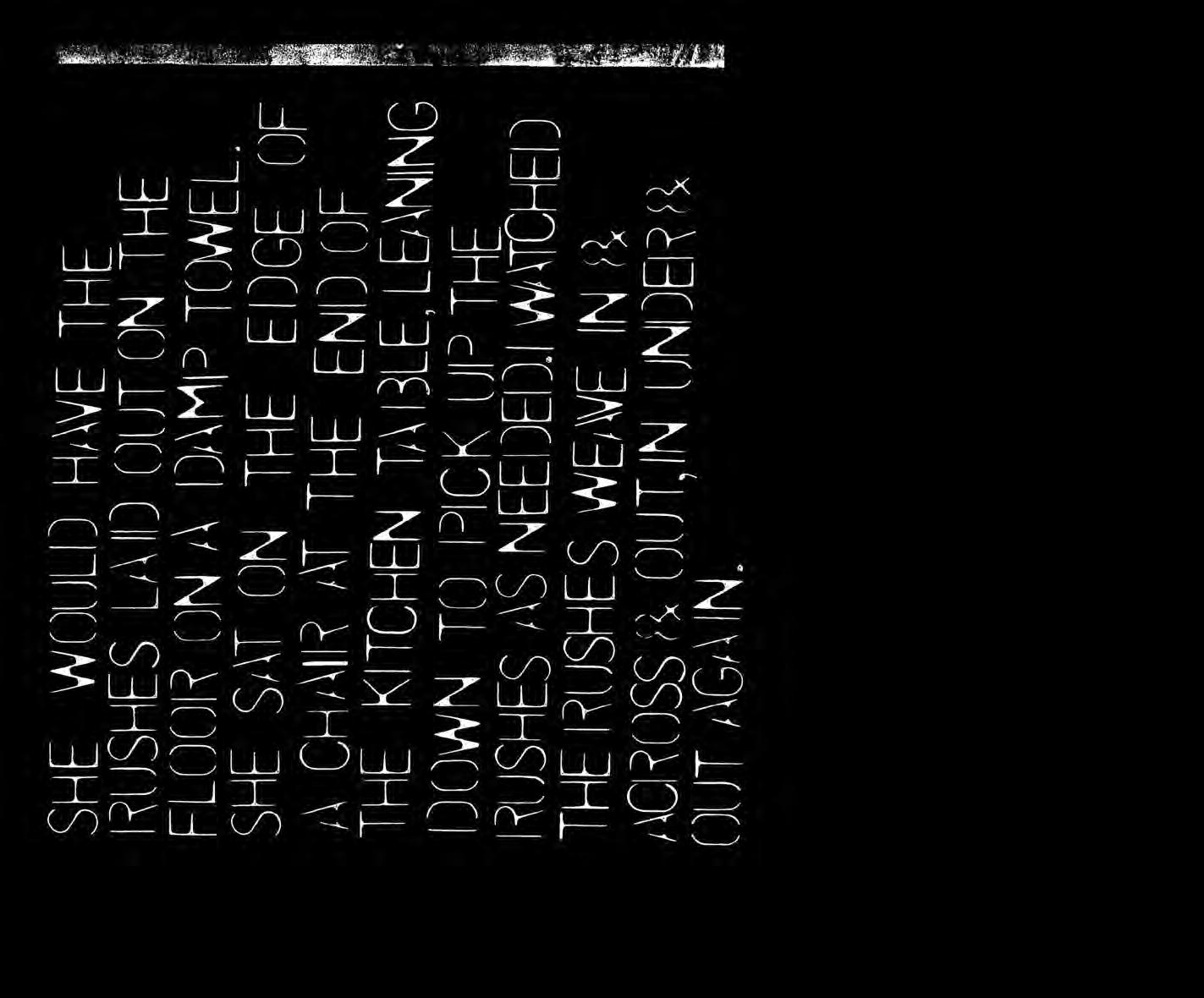

I was very taken by the lino cutting of quotes and memories from members –

pearsanta dhaoine a thagann isteach go dtí an spás. Ceann ag cur síos ar bean is í ag tabhairt fé cros a dhéanamh le luachra. ‘Sing or Dance’ scríobhta ar an dtalamh chun daoine a spreagadh chun amhrán nó rince. Cur síos ar cad is brí leis an Seid na nDaoine leis:

‘The People’s Shed a space for sharing skills and knowledge, exploring ideas of how a communities social fabric can be discussed, honoured and fostered through collective hand skills, sharing, making and thinking’

Chuaigh sé seo ar fad go mór i bhfeidhm orm agus d’fhéadfadh ana chuid spásanna eile tionchar a fháilt ón Seid na nDaoine agus an manna taobh thiar do.

Tá seana-thraidisiún Éireannach ann maidir le teacht le chéile i ‘meitheal’. ‘Meitheal’ ab ea grúpa comharsain a chabhródh lena chéile ar an bhfeirm, grúpa a thagadh le chéile chun

personal memories. One described a woman working with rushes, perhaps for a Brigid’s cross. ‘Sing or Dance’ was written on the floor of the shed, inspiring anyone gathered to perform and share their talents. I loved the description of what The People’s Shed was:

‘The People’s Shed a space for sharing skills and knowledge, exploring ideas of how a communities social fabric can be discussed, honoured and fostered through collective hand skills, sharing, making and thinking’

It really impacted me and the memories were really quite moving. I think that many other spaces could learn from The People’s Shed and the aim behind it.

The Irish term ‘meitheal’ also came to mind when thinking about what Evelyn achieved during her residency. The ‘meitheal’ is when neighbours help each other – from working on

cabhrú le bídh le linn tórramh agus mar sin de. Bhraitheas an traidisiún seo go mór sa Seid.

Gach éinne ag cabhrú lena chéile nuair a bhí gá, ag caint lena chéile, ag braith ar a chéile.

Tá sé rí-shoiléir gur ealaiontóir ar leith í Evelyn. Is duine ar leith í. Cinnte, pé togra ealaíne go bhfuil baint aici leis, beidh tionchar ag an dtogra sin ar dhaoine eile. Ní na héinne a bhíonn mar sin agus is léir go bhfuil Evelyn tar éis dul i bhfeidhm go mór ar an bpobal seo. Bhraitheas, fhad is a bhíos ann, go raibh rí thuiscint aici ar an áit, meas ar leith aici ar na daoine agus de bhárr, d’éirigh go hiontach léi. D’éirigh léi meitheal álainn cruthaitheach a tharraingt le chéile chun tabhairt fé ceardaíocht traidisiúnta agus chun cabhrú lena chéile. Obair ealaíne pobail thar a bheith inspioráideach.

1 Turner. V (1969), Liminality and Communitas, in the Ritual process: Structure and Anti Structure. Chicago, Aldine Publishing.

the farming to helping with food for funerals. I really felt that tradition in the Shed – everyone helping each other when there was a need, talking to each other, relying on one another. It is clear that Evelyn is a very special artist and more importantly a very special person and I am sure that any art project she will undertake in the future will benefit others as well. As we know, not everyone is like that! It was abundantly clear to me that Evelyn really had an impact on the wider community during the residency. I felt the respect in the room for her because of her respect for the place, the people and the crafts. Evelyn brought together a gorgeous, creative meitheal who together created the most beautiful crafts – community arts at its best and tremendously inspiring.

Dr Emma Mahony

Under neoliberalism time is linear, future orientated, driven by speed, measurable and quantifiable. It comes with the expectation that we must continuously strive to do more in less time in order to reach peak efficiency. Time is money.

Caring is necessarily incompatible with the speeded up time of neoliberalism. Care, in contrast, is fluid, relational and cyclical; it does not have clear boundaries. More often than not, caring (properly) requires ‘making time’ when there is not enough time.1

It is with projects like The People’s Shed by Evelyn Broderick that our attention is brought back to the centrality of care in our lives. It reminds us of our interdependence on each other in the face of the capitalist economy that thrives and grows through separating us from each other, through the monetisation of our time, and the devaluing of our care work.

The People’s Shed is a temporal proposition that seeks to disrupt the future-orientated, accelerated time of neoliberalism. It is a space where care-time is generated. Broderick and her participants in The People’s Shed make time for each other through little acts of kindness, by welcoming strangers, telling stories, listening, sharing problems and making cups of tea.

The People’s Shed is also a pedagogical proposition where participants learn from Broderick and from each other, by sharing often forgotten craft skills, like making súgán chairs – wooden stools with seats woven from straw or hemp – but more importantly, they are engaged in a process of unlearning the values of neoliberalism, namely independence, impatience, competitiveness, selfishness and greed.

But most of all, The People’s Shed is a radical proposition; precisely because the most radical thing to do in our neoliberal reality is to be ‘unproductive’; to take time, to slow down, to degrow, to unravel, to unlearn and to engage in reproductive labour.

Just because The People’s Shed might be described as an ‘unproductive space’, it doesn’t mean that nothing happens there. Women’s labour in the home has also been described by capitalism as unproductive, yet plenty happens in the home, it’s just not valued in the same way as so-called productive waged labour is. Without this hidden reproductive labour, this provision of care, the socioeconomic system would collapse.

The People’s Shed might be considered to be unproductive because nothing that can be easily measured and quantified is being produced, at least not through the existing neoliberal value system. The People’s Shed

has no fixed outcome per se, no deliverables. Broderick places no demands or expectations on her participants, she asks no commitment of them. ‘People don’t need to leave with a perfect, finished product or even mastery of a skill’, Broderick stresses, and they don’t ‘have to commit to coming back’.

But despite its laid-back attitude, lots of things are happening none-the-less. The People’s Shed is creating an abundance of social wealth, as opposed to ‘cultural value’ in its narrowly defined and quantifiable form. Groups, communities, relations, commons and connections are being forged. Lost skills are being shared and re-learned. A sense of pride in one’s creative ability is being nurtured. The participants are practicing solidarity and mutual aid and generating new affective bonds to repair the social bond that neoliberalism has torn asunder.

I witnessed much of this first hand during my two visits to The People’s Shed, which is housed in studio 468 located in a former red brick Methodist church and school that is now St Andrew’s Community Centre in Rialto, first with a group of students from the National College of Art & Design (NCAD), and later with the women’s group that gathers in The People’s Shed every Thursday from 11am to 1pm. On both visits the atmosphere was warm and welcoming, and the mood was industrious, but informal.

I brought my students to meet Broderick so they could experience an artist’s studio in action, in order to bring our classroom discussion on Daniel Buren’s 1971 essay ‘The Function of the Studio’ to life. I explained that this wasn’t a typical artist’s studio where works of art are produced, stored and then shipped off to be exhibited in a gallery

somewhere. I told them that Broderick’s art practice is embedded in its local community, that her role is more that of a mediator, a host and a facilitator for local community groups. That The People’s Shed provides a social context where groups can come together to share knowledge and craft skills and to make things and form connections.2

When we arrived, Broderick directed us towards a circle of chairs positioned around a large kitchen table with a brightly coloured plastic table cloth.

A plate of biscuits and lots of mugs awaited us and we sat drinking tea as Broderick spoke about her socially-engaged art practice, her background in traditional music – she plays flute – and her interest in alternative pedagogical spaces. She explained how The People’s Shed functions to bring all of these elements together under one roof.

She gestured towards a garden shedlike structure that stood at the back of the space. She told us that the shed has morphed and grown during the 20-month duration of the project. When we saw it, it had been embellished with woven blankets, crocheted flowers and finger knitted garlands, and she told us of the plan to roof it with súgán panels made from bright orange twine that are currently being crafted against the back wall of the shed. She showed us two chairs she had crafted with the same orange twine forming their súgán seats. Two of my students volunteered to work on the roof panels, while others took turns weaving a woollen blanket on a wooden frame and stencilling statements on pieces of paper.

On my second visit I encountered the women’s group sitting around the kitchen table chatting, drinking tea and eating cake.

I listened as they finalised the details of their Christmas party and pointed to some of the craft projects they had contributed to around the room. They praised each other’s work and told me to ‘ask X to show me photos of her amazing embroidery that took her years to complete’, and that ‘Y taught us how to make these woven blankets’, and that ‘the big pink one on the frame in the corner is nearly finished’, it was ‘for Z’s grandchild to put on her pram’.

When the tea was finished, a group of us began the slightly more complex process of helping to ‘tie-off’ the pink blanket, before it could be cut free from the frame. X told me that they ‘fluff up wonderfully if you put them into the tumbledryer, but only for 30 seconds mind’.

I had to leave before the session finished to get back to NCAD to give a lecture, but I told them I’d be back the following week. As I wandered back through the drizzly streets of Rialto, I felt elated from the warm welcome I had received and the meditative craft processes I had engaged with, but I also felt a bit sad.

I was wondering if these amazing women (and all of the other groups who engaged with The People’s Shed) will still gather and support each other when The People’s Shed is sadly no more. My gut tells me the answer is yes. That Broderick’s embedded relationship with each group has empowered them to continue independently of The People’s Shed and that she, and they, will continue to find new ways to host her ‘drop in’ sessions.

1 de la Bellacasa, Marià Puig (2020), ‘Soil Times: The Pace of Ecological Care’, in Matters of Care: Speculative Ethics

in More than Human Worlds. Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, pp.206.

2 Buren, D. (1971) ‘The Function of the Studio’, October 1971.

Evelyn Broderick

In 2010/2011 Evelyn graduated respectively with a BA in Fine Art Painting, Limerick School of Art and Design and H.Dip in Art and Design Teaching at Crawford College of Art and Design.

In 2015 Evelyn relocated to Liverpool to develop her arts practice where during her three years in North West England, she graduated with an MA in Fine Art from Liverpool John Moores University. Evelyn spent a year in Sweden 2017/2018 where the Nordic pedagogical practices have had an influence on her thinking and artistic practice.

Evelyn was co-founder of artist and art education co-operative Quad Collective CIC. From 2014 – 2017, Quad acted as an educational freelance group working alongside Tate Exchange, Tate Liverpool, The Office of Useful Art, The Uses of Art Project, L’internationale, STATIC Gallery, The Walker Art Gallery and Museo Reina Sofia. Projects include Art Gym at Tate Liverpool, Our Studio at The Walker Art Gallery and See/Think/Do with Collaborative Arts Partnership Programme (CAPP).

In 2020/2021 Evelyn was artist in residence at UCD’s Parity Studios at the College of Social Science and Law. She was awarded an Arts Council of Ireland, Arts and Participation bursary and Common Ground’s A Radical Imagination residency award 2022 – 2023. Evelyn is the recipient of a two year socially engaged residential studio award at Firestation Artist studios, Dublin and Create’s Artist in the Community Scheme bursary, 2023.

Dr Aoife Granville

Aoife Granville is from Dingle, Kerry, and is a performer, educator and researcher who holds a PhD in Folklore/Ethnomusicology (Dingle Wren & European Carnival Cultures). She lectures in Traditional & Popular Music, Folklore & Festival and currently holds the post of Lecturer in Folklore/Béaloideas at the Folklore Department, UCC. Previously, she lectured at the Department of Music (UCC), the International Centre for Music Studies at Newcastle University (UK) and with various visiting US universities to Ireland.

Aoife is regarded as an influential figure in the contemporary Irish fluting tradition and is currently working on her third solo album. A regular contributor to radio and television, Aoife works and publishes in both Irish and English. She was the Director of Ionad Cultúrtha Arts Centre in Gaeltacht Mhúscraí from January 2019 to December 2021 and previously sat on a variety of boards and committees pertaining to Arts Centres for Dingle as well as the External Advisory Board to the Vice-President and later President of UCC, 2018 – 2021. She is a board member of the Arts Council of Ireland and Ionad Phoenix Dingle. Aoife has also been involved in festival management as well as arts advocacy and mentorship for many years.

Emma Mahony’s research is situated in the interstitial spaces between the fields of contemporary art, spatial practice, curatorial studies, radical pedagogy and activism. Her research focuses on investigating how critical institutionalism and spatial practices can resist and rewrite the neoliberalisation of the public art sector in Europe. Her SPACEX research will examine how the practices and principles of commoning engendered by marginalised groups, can proactively shape how public cultural institutions deliver and manage their programmes, operational structures, day-today activities, collections and archives.

She is the Course Leader for the BA in Visual Culture at the National College of Art and Design, Dublin where she also works as a lecturer in the School of Visual Culture. She sits on the editorial board of Art & the Public Sphere journal. From 2004 – 8 she was Exhibition Curator for Hayward Touring, Southbank Centre, London. She is currently co-editing a Routledge Companion on Spatial Practice and the Urban Commons with Mel Jordan, Andy Hewitt and Socrates Stratis (2025).

Siobhán Geoghegan is the Director of Common Ground, an arts development organisation based in Inchicore, Dublin. She was employed in 1999 to set it up along with other local activists.

Siobhán was born and reared in London. She moved to Ireland in 1980 and was educated at Limerick School of Art & Design, Crawford College of Art & UCD. In 2011 she completed an MA in Art in the Contemporary World NCAD. Siobhán has been living in Rialto, Dublin 8 since 2000.

Common Ground is a celebrated locally based arts organisation in the heart of a historic and ever-changing area in the south west inner city of Dublin. It’s been working for nearly 25 years to ensure equal access to and participation in the arts in its immediate community, and in communities nationally.

Acknowledgements

Common Ground wishes to thank everyone who connected with Evelyn Broderick and The People’s Shed 2022 – 2024 during the A Radical Imagination residency award.

Special thanks is extended to:

Evelyn Broderick and her family, The Thursday morning women’s group, the young women’s group from Dolphin House, Rialto, Tony May and the Rialto men’s health group, Eilish Comerford, Sinead Clancy, Family Resource Centre St. Michaels Estate, Rita Fagan, John Bissett, Tony Mac Carthaigh, Siobhán Kavanagh, Ray Hegarty, Kate O’Shea, St Andrew’s Community Centre, Siobhán

Geoghegan, Ger Nolan, Catherine Marshall, Rialto Youth Project, the D8 Men’s shed, Mairéad O’Donnell and Sheena Barrett.

Published by Common Ground.

ISBN: 978-0-9539024-8-4

Photography: Sophia Tamburrini, Ray Hegarty

Design: Ruth Martin

Print: Print Media Services