Chanter

Chanter would like to thank the following:

Our generous alumni donor

Professor Matt Burgess

The Mac Weekly and their office

Facilities Services, for key access to said office

CSLE

Toby Hozier

The Link

Making things fit

Brueggers Bagels and the Brothers Dunn

Editor-in-Chief: Zoë Roos Scheuerman

Literary Editor: Nguyễn Trung Kiên

Art Editor: Emma Nguyen

Submissions Manager: Jamila Sigal Vásquez

Editor: Ian Glejzer

Staff:

Kelsey Blickenstaff

Brooke Bound

Caleb Coney

Addie Daab

Charlie Gee

Ellen Pendrak

Rosie Smith

Paul Wallace

An ounce of April tastes bitter when swallowed before the meal

An ounce of April tastes bitter when swallowed before the meal 8 Sarah Tachau

Ode To Dining

Hall Meals With Friends 10 Alex Sonnabend

Exercise 11 Chloë Moore

seasonal allergies 12 Violet McCann

Hamlet’s Eighth? 14 Holiday Rosa

B.A. in Psychonautics 15 Zelda Rose

Eructation 16 Kano Ottinger

I’ve eaten all the goats under my bed. 17 Marvellous Ogunsola

A meditation on paradox 19 Natalie Mazey

Lovers Return at Dawn 20 Nolan Manz

Inside the Moon 21 Zoe Grigsby Jolene 23 Luca Schira

[THE RISK OF WRITING

A NEW POEM] 38 Lucy Clementine

There is no innocent museum in america 39 Kaliana Andriamananjara

On Baguettes 40 Emma Nguyen The Pilgrimage 41 Nguyễn Trung Kiên

Passing Light 43 Cecelia Bauer

Darling I prayed for you 44 Marcus Alexander saving space 45 Gavia Boyden You Can Quit

Whenever You Want 46 Brooke Bound Tempest 47 Lucy K Hoberg diálogo 49 Laszlo Jentes

My Grandfather’s Chair

(A Letter I’ll Never Send) 50 M. W.

Flotsam and Jetsam 51 Rachel Lock lights off 52 Jamila Sigal Vásquez

Art ~

Summer Weeds 24 Ayuna Lamb-Hickson

Bubble 25 Leah Long Gulf Flounder 26 Jane Skjonsby

Four Horsemen 27 Noah Hanson

Claw Cleaning

in the Great Ketelsian Swamp 28 John Bunting

Flowers for Christmas 29 Nicholas Lobaugh

Gender as a Holographic Trading Card 30 Charlie Gee

Lily pads 31 Julia Bintz

Materiality 4/5 32 Aahanaa Tibrewal number 45 - to be read from right to left 33 Asa Rallings

The Fall (16 & 20) 34 Gabby Simpson

This Is Not The End 35 Bernadette Whitely

Marriage Bound 36 Maddie Sabin Red Tide 37 Miriam Ruiz

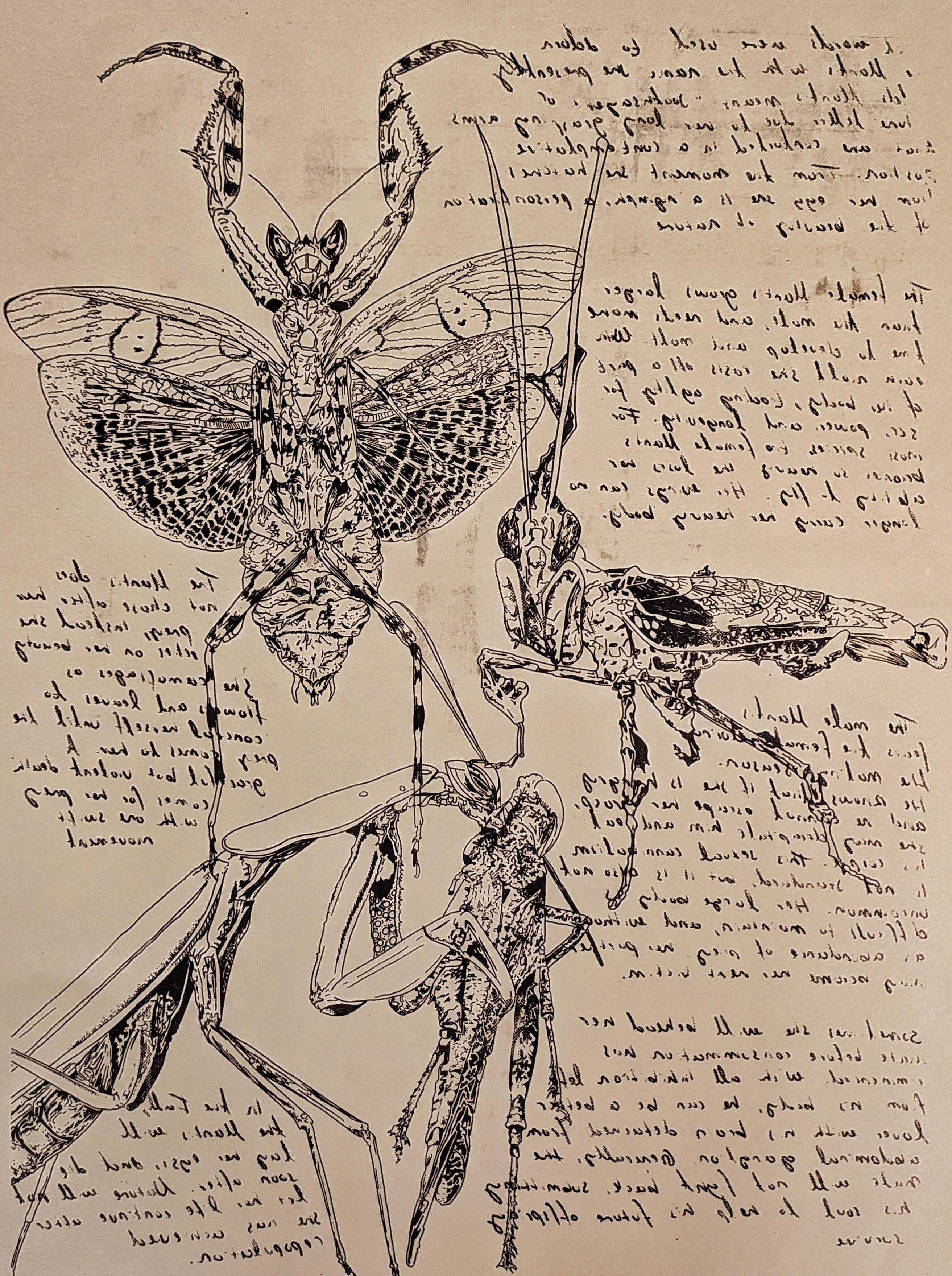

Cover art: The Female Mantis screenprint

Editor’s Note

Chanter’s power is its ability to unite and celebrate Macalester’s incredibly talented, sometimes criminally low-profile student artists. This collective makes production weekend worth it even when yet another round of copy-edits liquifies the Chanter team’s brains: Is that by-line in Garamond or Times New Roman? Comic Sans or Papyrus? C-H-A-N-TE-R is Wingdings! Especially after fall 2020, when I virtually attended my first Chanter meeting from my COVID-empty freshman dorm and printing physical copies was out of the question, I treasure every moment I can spend in community with people who respond to life’s beauty and brutality by making incredible art. As graduation looms on the horizon, those moments are also nearly over. I’ve tried to savor my time with Chanter this semester like a kid struggling to ration dessert, conscious that This Is It, and it still suddenly feels like there isn’t enough time and space to fully express how proud I am to have been a part of this amazing publication. Thank you to the staff, submitters, and readers who have become classmates, coworkers, role models, and friends, as well as the returning and incoming board members, whose work on this edition proves that they will do a fantastic job in the years to come. I am honored to have led the magazine and read your works, and I’m beyond excited to see what future editions will hold! The boat is tipping over the edge of the waterfall, so I’ll stop stalling and pass you the cargo: please enjoy the Spring 2024 edition of Chanter!

Zoë Roos Scheuerman Editor-in-Chief, 2023-2024

An ounce of April tastes bitter when swallowed before the meal Sarah Tachau

Apparently it’s January but the kids are whipping frisbees across the lawn, girls clustering behind the sleeping big tree to whisper, hands cupped to warm mouths shielding the wind from stealing their secrets, classmates cartwheel by, others twirl, arms outstretched drinking the sticky sweet sunshine and 60 degrees. The flag is back to standing at full staff, its cold shadow stains this camouflage lawn cropped cut and spotted with pink picnic blankets. An ounce of April tastes bitter when swallowed before the meal. No seed sprouts on an empty stomach. But that’s not what we want to hear. So swing on in oblivion, hang your hammocks from trees’ arched backs, aching.

A certain kind of beauty, we coin it.

My seasons are spent, broke from August rains and powdered Februaries, when boot-high snow caked the dormant earth, the ugly face of uncertainty adorned in a magnificent mask.

Sure, I see it now, the pre-spring pill is kicking in. I spin, my arms slice the air into a breeze, my hands uproot the fruit of an early bloom with a greedy yank and a sweaty tug, my teeth dig into the unforgiving flesh, I peel the pupa from its cocoon, “The birthing has begun” I cry to the chrysalis. Let us stare into the sun like children who know no better.

Sky, so blue I name you a blessing.

This May, waking before dawn. This January, dressed in June’s tunic.

I skip along chapped sidewalks, past weeping snowbanks, charred black like a neglected lung, and pretend I am a child twirling through this pleasant April afternoon.

Ode To Dining Hall Meals With Friends

Alex Sonnabend

Come friend, let us sit upon this discolored chair at this soda-sticky table. We both have teeth, enamel-coated and off-white — perfect for chewing. Our enzymes work in tandem, masticating carbs into sugar. Tell me about your day. Do you like your food? Is this what you dreamed of? Are we more than blood and bone? Laugh with me in between sips of something that’s either Mountain Dew or battery acid. Smear the grease on your lips with a napkin, brush the crumbs off your lap, let our presence linger like the taste of garlic on the tongue, wash it out with chewing gum. Come friend, share this meal. We are hungry and we are sated and we are loved.

Exercise

Chloë Moore

Autumn. We throw apples, the crab sort, for the dogs. One of ours finds antlers. Bleached bones. In an old essay the bats flickered above the still waters. We go boating. I adopt a Cat. Or I think about it. I catalogue tent caterpillars in the nearby trees. These Days are dreary. I mistake an owl for a dove. I remember last year, when I got stuck in an Elevator. It made a metal envelope around me. I felt Fragile. It was a new kind of fear. We

Giggled to make it through the tension while the machine gurgled around us.

Heartstopping lurches, until we got out. Later that year we built an Igloo. My mother learns to dye with indigo. She mails me skeins of blue. I abandon Jargon for joy. Housepainting instead of Kangarooing between projects. This too is a kind of Love. The lilies aren’t blooming anymore except in a voice on the phone. I slice lemons. It’s Mellow. I climb more mountains. It’s nice.

Nutmeg season is approaching. Until then it’s still rosemary and cumin. I haven’t peeled an Orange in quite some time. The stickiness — I evade it. The sections, like pieces of a Puzzle. When it comes together the pandemonium

Quiets for a moment. In the gleaming sink the dregs of dinner Ripple. My body is still ridden with things I don’t understand. Shampoo, a luxury sometimes. I use an electric Teapot. It’s terrifying, being like this. But maybe also Universal. I make sickness an umbrella. It

Vines its way around me. It’s velveteen and violent. I snip it and vase it. My bones go White on the

X-Ray. It’s been nearly long enough since this started. A Year. Two. And I’m no longer yours. Instead I’m a Zombie of myself. Beyond death. Maybe: alive.

seasonal allergies

Violet McCann

Winter passed, and he went inside. He slipped his shoes off just before he entered and left them out in the hall. Taking a deep breath, he stepped into his apartment, careful not to cause unnecessary air movement that might rustle his clothes or hair or the stuff that remained on his skin, and he swiftly took off his socks. Then he unwound his tie and paled, thinking of it flapping around in the wind as he walked like a tape trap for flies. Lips pressed tightly together, his nose plugged pre-exhalation, he unbuttoned and removed his linen white dress shirt he’d worn for his last day in the office. Then, methodically, his third-favorite pair of cotton navy trousers. He was almost unable to hold his breath any longer by the time he reached for the waistband of his briefs. Swiftly, in one direct, pre-planned hypotenuse from the foyer to the kitchen, he thrust it all into the oven, already steady at 430 degrees before he left for the office. Then, he crept to the shower, careful not to disturb the balance of the particles on his skin. He scoured his scalp with unscented shampoo until the only flecks remaining were dandruff, and some of his hair follicles bled. No conditioner. Then, he washed himself thrice from the folds between his toes to the crevasses behind his ears; first, a dish sponge and body wash, then a loofah and a fresh bar soap, and finally a towel soaked in disinfectant spray. He dried off with a towel he had pre-positioned, then immediately went back to the kitchen and tossed it in the oven as well.

He would never use the oven to cook, so there in the oven, the clothes and the towel would remain, at 400 degrees for the day, then sealed away at nothing for the rest of them. The stovetop was suitable. A week prior, he had bought 272 cans of chicken noodle soup, 136 frozen chicken breasts, 340 portions of oatmeal, and 136 bags of potato chips. Additionally, 272 coffee pods for his coffee machine. The soup, oatmeal, and potato chips were stacked against the bedroom wall. The coffee pods were ordered by day on the kitchen countertop. He would have to have it bitter, as he was short on sugar.

In the bedroom, he pulled on a pair of cotton jeans and a t-shirt from his closet, which had been ordered new two weeks prior and hand-sterilized the night before. Then, he grabbed his laptop from his bedside table, and took it to the pseudo-living room beside the kitchen. There, he sat on the squared-gray chair across from his television, and cradled the device, for a moment. For a minute. For thirty. Then he opened it, and started to type.

Mr. Moore,

Thank you very much for my time at your advisory firm. Although I’ve enjoyed this Winter with the team, I will not be able to come to work anymore. Please discard anything I’ve left at my desk.

Unsure of what else to say, he shifted his attention to the singular window in his apartment only to remember that he’d sealed it shut with glue and rubber, and that he’d put a dark film over it so that the light wouldn’t promote any residual particles. He was sure that he’d missed at least a few hundred. He couldn’t think of the possibility of a thousand.

He sent the email prior to signing it. Then, he scrolled through his contacts, deleting each conversation, then the contact information of each one. Except for Dave. So, he turned on the television and began his hibernation. There was a segment about bees on his favorite news channel, and he hoped the news was that the insects had all died.

A scream ricocheted between the walls of his apartment building and the neighboring one. Then another. Then cohesive cries for help.

He got up and turned on the stove. He tried once, twice, thrice, but he couldn’t hear the gas click-clickclick over all the noise.

The screams became bellows, then cries, then sobs.

His only pot was already on the stove, put there that morning. He retrieved a soup can from his bedroom wall and cracked the top.

Then, it was silent.

But for the bubbling of the chicken noodle soup and the soft tink of his fingernails grazing the side of the can as he moved it to the sink. And for the solemn hum of the oven, which he would turn off in an hour. Letting his soup simmer, he made his way back to the chair. He reopened his computer and deleted Dave’s number.

When he retrieved his soup, he left the residue in the pan. He would wash it later. For the start of Spring, he sunk into his chair to see if all the bees were dead yet.

Hamlet’s Eighth?

Holiday Rosa

on grandma’s hard candy and my 11th grade english class

nothing nothing writing my nonsense prose

Wonka’s fever dream — a set undone

Poor Yorick has gummy worms out his nose

Ophelia’s choking on bubble gum monologuing on abt sugar-high-joy see ‘cause ‘the chocolate lake is the thing, wherein I’ll catch that little Dutch boy’ and his mama will go on pretending

Rosencrantz went south tasting candy floss

Guildenstern sucking on chewable slacks

did Roald Dahl imagine this chaos

Hamlet and Charlie are the same in fact first, a man, and second, sweets to the sweet wish I had a sugar pencil to eat

B.A. in Psychonautics

Zelda Rose

Fuck Nancy Reagan! Give me a D.A.R.E. t-shirt to cut short at the ribs and a capsule of stardust to swallow, a note to pass in class or pass to the girl who puts it under her tongue, sour as sinking your teeth into a swollen lemon. The trick to having fun is to remember that we will not become faeries tonight. We are the worst of witches, playing with poisons to dance naked around the fire, pupils blown wide and black as the new moon — all the better to see your smile with, my dear! Is the shadow in the woods paranoia or instinct, something long dormant finally awake for six hours to trick me into thinking myself a genius? I want to walk to the stream like the silent deer, to kneel and drink or to slip in, to dissolve like a tissue dropped into the sink, all thoughts spiraling around the drain.

Eructation

Kano Ottinger

Racing up A dark and tight Tunnel

Emerging to only find The unforgiving confines of the world

Yet they keep coming Who can tell those That bring remnants Of the past To stop — surely, not I

For I am the one That loves them the most Encourages them Despite knowing it’d Be best For both, to stay in

I’ve eaten all the goats under my bed.

Marvellous Ogunsola

After Robert Frost Ghosts.

I’ve eaten all the ghosts under my bed.

They came to take me away, to take me to my grandfather. I refused. I refused once. Maybe twice. I remember the pink-haired ghost sitting, //embellishing heaven like it needed more marketing. I sat there, plotting a quick escape.

Poems about the end of the world: Robert Frost will never melt. If the ninth hell is ice, then what are the odds it’s just like Minnesota?

Goat farm. He lived for his goat farm, he loved his goats. He sold them, milked them, mutilated them. He was very macho, ablaze in fire and glory. I’ve sought refuge in my bed, my comfort abode. The recession is never coming so I have no excuse for this //laziness, the grief left right after the phone call, so I have no excuse to be in bed. You need cruelty to survive, //he said.

Poems about the end of the world: Robert Frost will never melt. If the Cats movie adaptation is bad, does that mean I have bad taste?!

My burgeoning sorrow bleats for help bleakly. My grass-fed heart blames myself. Eating muffled //sobs, muddled thoughts, muzzled muffins. He was a do-nothing, no-good terror, //lashing-out-at-babies type, ne’er-do-well, finger-crackling, caterwauling evil old man. He made fun of my pronunciation //all the time.

I don’t miss him!

Poems about the end of the world: Robert Frost will never melt. If everyone is sad, then why is everyone at work and looking good doing life?

I’m not going. I know where I am, I know where I come from. I come from a lineage of dogeaters: eat dog, eat world, eat labia, eat gun, eat everything. Just survive. I’m eating //my grandfather’s favorite goat.

Poems about the end of the world: Robert Frost will never melt. If the world is ending, then why are the poets waxing and writing?

I feel full. I leave my bed to get water. From here on out, I leave my bed every day.

Poems about the end of the world: Robert Frost will never melt. If the final stage is acceptance, then how on earth will I live with myself?

A meditation on paradox

Natalie Mazey

When I decide I must become a blank slate I call to tell you I cut my hair and you tell me I am not built for suffering painting laugh lines along the corners of my eyes your revelations pierce the dark your freckles strewn like constellations echoing the brushstrokes of a heaven I am unsure exists you tell me you’ve seen miracles happen right under my nose and to you that is proof enough

I tell you I’ve seen the sky christened in hues of gold and found that etchings of seafoam feel far from strangers but still this vastness does not tell me to concede so I tell you my only miracle is that I can look to you

Maybe believing in God is like believing in a person who believes in God let my faith in you be faith enough

Lovers Return at Dawn

Nolan Manz

His rough skin waits for me somewhere the noise of burning skateboard wheels on red brick echoes in the summer heat. I returned home and I stared absently into the nothingness of West Texas highways and the world felt tighter in the flayed air. I remember being inside his Jeep at night as we sat and cried in our long silences, sorrows being taught in our time together and guilt being built while now across this cracked asphalt ocean his uprooted long hair shines on the highway’s horizon under that oppressive sun, as I wait for you with coppery, burnt skin.

Inside the Moon

Zoe Grigsby

Only thirteen years of age, I was nothing but a gardener, sneaking outside at midnight to water the carrots; In the dark, my aim was poor, and water escaped my grasp like a poorly rehearsed confession; I was unaware of when it met the earth, or when my vegetables had grown.

So I looked to the night sky for help, and when the moon felt me staring, he met my gaze with his, and his craters transformed into small portals to dimensions beyond the boundaries of Pluto and Mars and nighttime and herbs.

I floated out of the garden and towards his sparkling crater-portals. Each celestial gateway emitted vibrant music: Chimes, and hymns, and a pot banging against an aluminum countertop. In one portal, I saw my grandmother playing a flute as a young girl — simple melodies drenched the dark chamber. In a different lunar tunnel, I saw my own body, transformed into metal, plastic, and synthetic fear. Violins and cymbals and cicadas made symphonies.

Another portal illuminated the murky pond by my house, but its surface held the reflection of a frozen tundra from some untouched civilization.

A child whistled a tune I should’ve recognized, but couldn’t.

I don’t remember how long I stayed in these sound tunnels —

being shot through moon’s songful subterranean subway system — until the planet spit me out, feet first.

When I finally got my bearings, I found myself in a familiar garden, but here, my carrots were fully grown. And in the distance, Bach’s Cello Suite in G major played in reverse.

Jolene

Luca Schira

I fear my mother will not live to see my children

Her words linger loose in my room

So shockingly soft and fragile

But there they lie like kindling

Feeding the picky flame in my head

I take my shirt off and see her there

Sand on her boots and soot on her face

She picks a cone from the hot ground

Longleaf pines are charred in her wake

Months later they flourish, still warm

I fear my mother will not live to see my children

Mortality clogs my ears yet I don’t flinch

Finding peace lying on the leaves

Still wishing I wasn’t deaf to the world

But all the streams here are frozen

After the funeral she drives me a decade younger

Her child is grasping dearly for his life

Learning he must die too

Her words soothe him like peepers at night

Inspired by her mother before her

Walnut Grove Church Road

My little feet fall from my mother’s truck

She takes me to the free pile

There I find my treasure

A shard of blue plastic at my feet

My soft hand grabs it

Twists it between chubby fingers

And extends it to my mother

Thirteen years later we both return

Sending off the last signs of my life here

I search between the gravel

There’s still treasure to be found here

Summer Weeds watercolor

Gender as a Holographic Trading Card earthenware, mixed media

Charlie Gee

Lily pads print, etching

Julia Bintz

Materiality 4/5

digital photography

number 45 — to be read from right to left digital photography

Asa Rallings

The Fall (16 & 20) graphite

This Is Not The End

multimedia collage

[THE RISK OF WRITING A NEW POEM]

Lucy Clementine

I think there might be more. Just for a moment, more to this one.

Have you ever shared it with anyone?

The poem you keep on the underside of your wrist?

The one on the outside of your ribcage?

The poem that cannot be concerned with tomorrow, that does not remember yesterday, it is creating and being created between your forehead and my neck, another between your palm and my stomach, one more between my leg and your hip.

Have you ever shared that poem, on the underside of your wrist, with anyone?

Have you ever let yourself be sad and called perfect?

Do you want to? Nod your smiling lips, undermine, slide to my neck to the poem I keep behind my ear, your whisper like rustling ivy spreading across my skin and planting hundreds of gentle roots. Not all voices write poems, and those that do pull up one tiny root and find a way to write about the sting for months.

Replant and refuse its oxygen, oh, to care for and never be cared for.

Leave your ink your voice like ivy traced all over my skin I do not write a poem. I do not write this one.

You are the author of all, author of me, author of the poem I keep on the underside of my wrist — that one that has been waiting to be written, the one undermine.

There is no innocent museum in america Kaliana Andriamananjara

Every time I go to the art museum in my city I go to their Africa section

— one room below a floor with hundreds of rooms dedicated to each decade of America and Europe. They say “This is Africa” of their 20 exhibits from 15 of Her 54 countries. Countries carved by the knife of England, who still bleed gold and oil for it.

I know the countries in that room, and those who aren’t but I still look for mine. I don’t find it. We aren’t even Africa.

They have Tanzania near Senegal, who wouldn’t be neighbors outside this place. Whose house was raided for this Maasai Mask? Whose tomb was ransacked for this Yoruba tusk? Someone’s face and hands bled to model and make this beautiful shrine — the exotic word for “memorial”— Only for 18-year-old white boys to laugh and call it ugly. There isn’t an artist or model name on the plaque. They are several oceans, countries, centuries away, but they are my sisters.

When I was in France, I went to the Louvre. They have a section called Pavillon des Sessions, one room for, to quote, “Africa, Asia, Oceania and the Americas.” I searched every piece, looking for my country. You would think our colonizer would have our art on display, the way a fisherman boasts a fish, a hunter mounts a deer head. But they keep our art in their basement — they don’t even give it back. I don’t know if it would have hurt more to see our art put up: A layered alo alo on a red French wall, to be demeaned next to Da Vinci, or a valiha on a stand for mustached Frenchmen to compare to a guitar.