5 minute read

Sounds of campus life spark unique compositions that open ears and eyes to the power of imagination

found sound

sBY DAWN BONKER

Advertisement

Listening to campus life sparks unique compositions that open ears and eyes to the power of imagination.

How do you capture a sunset in sound? Would a cupcake parade be noisy or as soft as buttercream frosting? And how do you transform such thoughts into music?

Those were some of the challenges tackled by students in a Chapman University music technology course this spring semester. The young composers were challenged to write such music in an assignment you could liken to a mashup of old-fashioned games like charades, musical chairs and telephone. The result is a collection of contemporary minicompositions that represent the sounds of campus life as heard and interpreted by the students in Principles of Music Technology.

“There's just so much creativity because it's so open-ended and flexible,” says Adam Borecki ’12, who teaches the class offered by the College of Performing Arts’ Hall-Musco Conservatory of Music.

The project began with a deceptively simple assignment early in the semester. Students went to a place on campus where they’d never been. There, they turned off all devices, including headsets and phones. They sat, observed and listened. The campus-listening part of the assignment was completed before Chapman shifted to remote instruction due to the coronavirus pandemic.

Using only the inspiration of what they saw and heard, the students drew a picture.

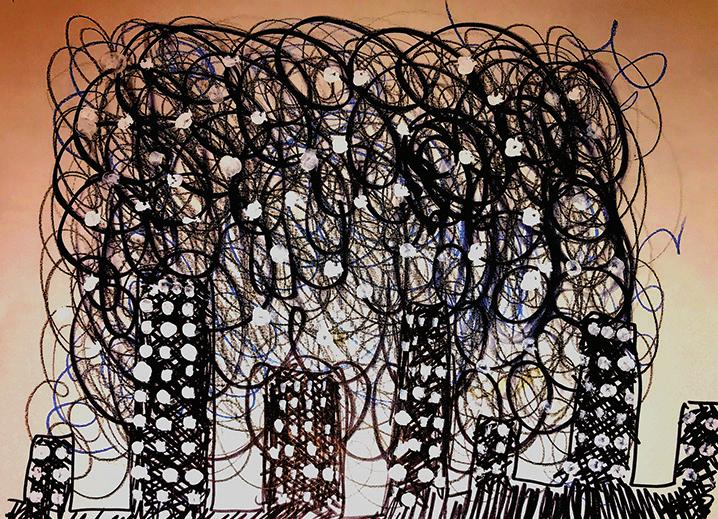

To hear students' mini musical creations inspired by graphic compositions like the one shown above, open the QR code reader or camera app on your smartphone and scan the code here. Or find the compositions online at news. chapman.edu/2020/06/09/found-sounds/.

ADAM BORECKI ’12, instructor of music technology in the Hall-Musco Conservatory of Music

The campus-listening part of the assignment was completed before Chapman shifted to remote instruction due to the coronavirus pandemic. The software used for this style of electronic composing was free, and Adam Borecki's Zoom classes kept students on pace with the work. The drawings were set aside for about a month while Borecki helped the students master music composition software. Then the artwork – called graphic scores or graphic notation in experimental music – returned. Each student received a classmate’s graphic score and from that wrote a 30-second piece of music using a vast array of electronic sound files, ranging from high-pitched droning hums to snippets of more conventional music, like a few notes strummed on a guitar.

The result is a collection of compositions, each piece a bit of unique, collaborative art. The software used for this style of electronic composing was free, and Borecki’s Zoom classes kept students on pace with the work.

“The idea that students create their own work, and then they give it away and somebody else has to re-create it, is exciting because part of creativity is embracing uncertainty,” Borecki says.

For Jack Ruhl ’21, the process was eye-opening. He sat atop Keck Center for Science and Engineering from late afternoon until sunset. His graphic score reflects how he tried to “listen from left to right.” He drew a kind of highway down the center of his score – certainly not reflective of the view from Keck, which overlooks Wilson Field. Rather, it was symbolic of how he perceived the sounds there.

“I do see images when I listen to things,” says the television writing and production major who is minoring in music technology. “I thought, ‘What if I told everything from left to right?’ So that affected the types of buildings I put in there. And on the right, I put some birds in the distance, and on the left the birds are bigger because I heard them more.”

At the other end of the assignment was the task of composing music from another person’s drawing or sketch. Mady Dever ’21 couldn’t help but smile when she saw Kylee Kamikawa’s ‘21 graphic score, a clutch of pastel cupcakes inspired by a fundraising event.

“I thought, ‘How does this relate to sheet music in any way?”’ says Dever, a screenwriting major minoring in film music composition who partners with her actress sister Kaitlyn Dever (“Booksmart”) in the folk-pop duo Beulahbelle.

Dever embraced the challenge of the class project.

“I was only getting happy from the image, so I knew I had to make some majorsounding melody. I think you have to take the initial emotion you get from the visual,” she says.

Hearing what a classmate did with his black and white graphic score was revelatory for Ruhl, too.

“I was expecting something completely different. Maybe something cyberpunkesque or like something from ‘Blade Runner,’” he says, laughing.

Instead, classmate Jacob Hepp ’22 composed a softly ominous piece with instrumental moments.

Of course, that’s all part of what Borecki intends for the class. While they learn new musical technology skills, students also hone the oldest tool of all – imagination.

Inspired by what they hear during a first-time visit to a campus location, students in Adam Borecki's music technology class draw a picture, known as a graphic score. Then another student interprets the score as a musical composition.