Editorial staff Editor’s note

Erica Veal Guest Editor

Erica Veal is a founding member of the Lowcountry Action Committee. Her background is in natural and cultural history interpretation and she believes in the unification of Africa and the diaspora under scientific socialism.

Belvin Olasov Co-Editor in Chief

Belvin Olasov is the co-founder and co-director of the Charleston Climate Coalition. His background is in creative writing and believes in bringing vision-making and art to climate work.

Sydney Bollinger Co-Editor in Chief

Sydney Bollinger (she/her) is a writer and editor affiliated with Surge and The Changing Times. She aims to connect communities to climate action through narrative and collaborative storytelling. Find her online @sydboll.

Blake Suárez Designer

Blake Fili Suárez is a graphic designer with a focus on branding and illustration. He is a co-founder of The Marsh Project and he works out of a room that looks out on a little meadow he is planting with his kids.

Hailey Williams Creative Writing Editor

Hailey “Pell” Williams is a Charleston native, poet, and swamp-trekker. You can find her work in The Birmingham Poetry Review and Tupelo Press’s June 2023 30/30, amongst others.

Brittney Washington Cover Artist

Brittney (Blue) Washington (she/they) is a multidisciplinary artist, cultural organizer, and co-founder of Flowers for Palestine, a Black, femme-led group of Lowcountry artists and organizers. She serves as a visual arts producer for social justice groups, studies filmmaking, moonlights as a doula, and is a registered art therapist who has facilitated internationally to illuminate the historical events that shape our current experiences of racialized poverty, trauma, and disconnection. She curates arts-based spaces where folks can be brave, vulnerable, and imaginative about how to shape a liberatory future. See their work on Instagram (@thegalwhofellfromspace) and online at www.labrittneyarts.com. For commissions, email bnw.washington@gmail.com

Cover Art: “Cousin Earth”

Marker & Ink on Paper

10.25 x 10.5 inches

2024

Greetings Gentle Readers,

Welcome to the Lowcountry Action Committee’s Gullah Geechee and Earth takeover issue of Surge. The Lowcountry Action Committee (LAC) is a Black led grassroots organization dedicated to Black liberation through service, political education, and collective action in the Lowcountry. All contributors to this issue are either founders, general body or incoming members of LAC who identify as Gullah Geechee or as having Gullah Geechee roots.

LAC has been a member organization of the Charleston Climate Coalition for a couple of years now and, in 2024, we were inspired to take a more active role in exploring the intersections of the climate catastrophe, environmental racism and the human rights crisis. It is our duty to draw attention to how this triple threat impacts African descended people in the Lowcountry and take the lead in the environmental movement to fight against it. We cannot take a backseat in this struggle when our homes are flooding on a regular basis, our food supply is being poisoned and we face racial disparities rooted in slavery and Jim Crow apartheid that perpetuate our second-class citizenship in society.

As you make your way through this issue, please keep in mind that LAC does more than just write. We also feed people, host educational programs and cultural events, sponsor travel to Cuba, scholarships and more. For more information about LAC, follow us on all social networks @lctakesaction or visit www.lctakesaction.com. You can also support our work by volunteering with us or donating to our Venmo @lctakesaction or CashApp $lctakesaction.

A special thank you to Joshua Parks for providing the photography for this issue, Brittney “Blue” Washington for providing the cover art and our contributors Mosiah Asad, Rashad Brown, Karl Noble, Salifu Mack and Akua Page!

In solidarity, Erica Veal Surge Issue 8 Guest Editor

INFORMATION, EMAIL surgemagchs@gmail. com

Climate Reparations as SOCIAL JUSTICE SOCIAL JUSTICE

WRITTEN BY AKUA PAGE

As a Gullah Geechee college student studying environmental science, I am deeply concerned about the impact of climate change on my community. Gullah Geechee people, descendants of West and Central Africans enslaved on the coastal regions of South Carolina, North Carolina, Georgia and Florida, have a unique community with a rich cultural heritage deeply rooted in the land and sea. Our culture and way of life is currently under threat due to climate change fueled by environmental racism. These threats, however, are not just about rising sea levels, but include a broader range of environmental changes that are impacting our way of life. Climate reparations, a concept that is gaining traction globally, could be a key part of the solution to our historical problems.

Climate reparations refer to the idea that those who have contributed the least to climate change but are suffering the most from its impacts should receive compensation. This concept is rooted in the principles of justice and equity.

For Gullah Geechee people, whose traditions are intrinsically tied to our environment, climate reparations is deeper than just addressing current and future environmental challenges--they are also about rectifying historical injustices. We have faced centuries of marginalization and exploitation, which have left us particularly vulnerable to environmental changes. We depend on the land and sea to sustain us and, as climate change continues to impact our region, we face new challenges that threaten our way of life.

For instance, the warming of ocean temperatures has caused a decline in blue crab, a staple in the Gullah Geechee diet, economy and a significant part of our cultural practices. South Carolina recently attempted to pass a bill (S.955) regulating the harvesting of blue crabs to address their declining population. While proponents argue that a licensure program is necessary for their numbers to rebound, this could disproportionately burden Gullah Geechee fishermen and women who may lack the resources to navigate the complexities of a licensure program. This could result in the exclusion of Gullah Geechee people from a fishery that has sustained our maritime culture for centuries. Climate reparations could address this by providing financial support and grants to Gullah Geechee crabbers to access sustainable fishing gear, boats, and infrastructure and by investing in restoring and protecting critical blue crab habitats, such as salt marshes and estuaries. Reparations could also provide funding for educational programs on blue crab biology, behavior and migration patterns in response to climate shifts and seek to involve Gullah Geechee fishers in decision-making processes related to fisheries management, conservation, and climate adaptation. Finally they could establish community-based cooperatives that allow crabbers to collectively manage resources and share knowledge

Climate reparations could help address historical injustices and the climate crisis by providing much needed resources that will allow Gullah Geechee people to adapt to environmental changes, preserve our cultural heritage and build a sustainable and resilient future.

PHOTO | Nathalie Marie Visuals

PHOTO | Joshua Parks

Digging Toward Death: Phosphate Mining through a Gullah Geechee Lens

WRITTEN BY KARL NOBLE

Though phosphate rock was first discovered in the Lowcountry during geological surveys in 1795, it was not mined commercially until 1868. The phosphate industry thrived in the South Carolina Lowcountry for about 20 years before dying out and, in this short time, was responsible for about 50% of the phosphate used worldwide, absurd profits and the destruction of tens of thousands of acres of river beds. The accompanying chemical manufacturing polluted Lowcountry soil, air, and waterways, and diminished the quality of life for Gullah Geechee people who served as the main labor force in this destructive industry.

After the Civil War, the decline of the rice industry left many plantation owners struggling to maintain the massive plots of land they occupied, due to the loss of access to slave labor. At the same time, the phosphate mining industry emerged and there was a rush to found mining companies and worker towns, and sell or lease land to mining investors. Newly emancipated Africans were the preferred labor source in this industry. They were seen as conditioned to work in the harsh subtropical environments and resistant to some of the rampant mosquito-borne diseases that plagued the area. Though Gullah Geechee laborers could now earn a wage, most were only paid around $1/day for performing back breaking, dangerous work year round. Those who opted to live in mining towns often found themselves perpetually indebted to mine stores who provided them and their families with everything from medical care to food rations at exorbitantly high interests. Workers did exercise some autonomy though by refusing to work from noon on

Saturday until noon on Monday, so they could instead work for themselves.

Phosphate deposits as large as 100 feet deep and 20 feet wide were found along riverbeds and tributaries from Charleston to Beaufort. River mining was preferred as phosphate deposits were closer to the surface and higher in quality. The Ashley River was home to some of the largest mining companies which produced an average of 600 tons of phosphate rock per acre across thousands of acres, leading to mass destruction of marsh ecosystems. Working conditions were especially brutal at these riverside mines where workers dug through pluff mud along the riverbed at low tide and dove to the bottom of the river bed pits, holding their breath while extracting the phosphate rock until their fellow workers pulled them back to the surface. To make matters worse, phosphate mining also exposed workers to industrial chemicals.

PHOTO | Joshua Parks

Trace amounts of uranium were emitted during phosphate rock excavation, exposure to which has links to the development of cancer. Initially, companies shipped the phosphate off to be processed into fertilizer, but later began processing it on site. This required the production and handling of sulfuric acid:

“Sulfuric acid manufacture was probably the most dangerous of all aspects of [phosphatebased fertilizer] production. Chambers that were not well-maintained posed threats not only to the men through chemical burns and inhalation of highly poisonous gases, but leaky chambers also affected local crop lands and polluted the environment. As with labor information, information on work hazards and health effects of fertilizer production has yet to be synthesized.”

Workers had no fail-safes in place to ensure their safety nor that of the local environment and nearby communities in which they lived. While all the phosphate mines in South Carolina have since closed, their legacies live on in fertilizer manufacturing plants that still operate in the area today.

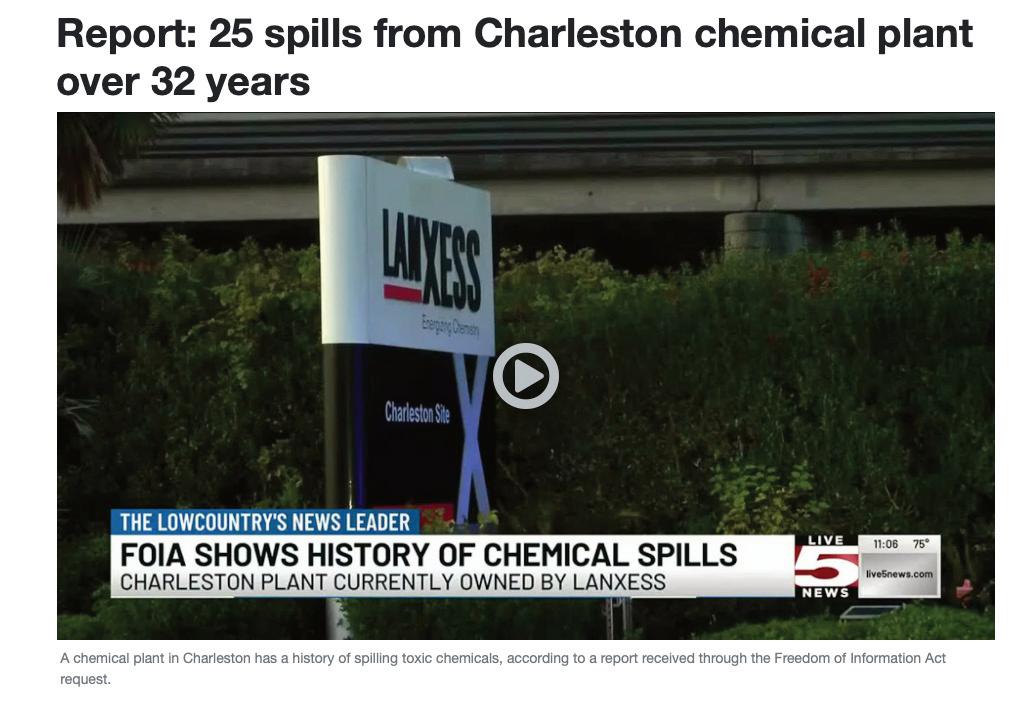

Lanxess, for example, is located on King Street Extension in North Charleston where another fertilizer company named Imperial once stood. It operates in close proximity to about a dozen Black neighborhoods. It is less than a mile away from Rosemont and Union Heights, just over a mile away from Accabee and Chicora Cherokee and there are another dozen or so Black communities within a five mile radius. A 2023 FOIA request revealed Lanxess had at least 25 incidents over a 32-year period where toxic chemicals were released into the environment despite OSHA and DHEC regulations. The EPA has stated that people living in the 29405 zip code (where Lanxess is located) have a higher chance of developing asthma, cancer and other pollution related health problems. This is the same zip code where the phosphate mining industry thrived 160 years ago. In the face of this ugly and deeply rooted history of environmental racism, it is grossly irresponsible for the State of South Carolina to allow Lanxess to operate with its reputation for neglecting the health of local communities and ecosystems. I urge all Lowcountry residents who care about and respect the environment to sign the petition linked above (see QR code) calling for the closure of Lanxess today!

PHOTO | Joshua Parks

A u g u s t 1 4 | 5 : 3 0

P a l m e t t o B r e w i n g

D r o p i n t o m e e t t h

l e a r n m o r e a b o u t

i s s u e s c l o s e t o h o w a y s t o g e t i

35 years of keeping nature & community in balance

T o v i e w o t h e r u p c o m i n g e v e n t s ,

v i s i t c v s c . o r g / e v e n t s c o a s t a l c o n s e r v a t i o n l e a g u e . o r g

Cuba’s Life Task And the lowcountry

WRITTEN BY SALIFU MACK

PHOTOS BY ERICA VEAL

I ran into an elder recently who greeted me warmly and gave me the tightest hug. While making small talk, she said to me “Baby, I don’t have a good feeling about this comin’ hurricane season.”

I asked her why and she replied, “I can feel it in the air. And when you turn on the news and you see everything that we [the US] out here doing in the world, you can’t be surprised.”

She expressed her concerns about vulnerability to natural disasters, and how she feels Black people, or Africans as I will continue to refer to us, have never been protected from them here. And she’s right. My comrades Karl Noble and Erica Veal recently wrote that:

“Our [US based Africans] relationship to environmental racism stretches back to the emergence of the local phosphate mining industry in the 1860’s and manifests today in the disproportionate exposure of Black and low income residents to environmental hazards.”

When we talk about hurricane season as Africans, we are talking about an intimate fear of the winds spinning out of control off an ocean that was once forced to swallow us whole during the transatlantic slave trade. And when we talk about the damaging effects of climate catastrophe, the South Carolina Lowcountry needs more priority. We have on our hands a number of sea islands (sacred sites for Gullah Geechee people), and low lying areas which are vulnerable to rising tides and shore erosion.

plastic bags under the kitchen sink, and reusing plasticware.

So in a society more obsessed with profits than human life, where can we look for guidance? The answer: 780 miles off the coast of Charleston on the island of Cuba. The island nation, led by the Communist Party of Cuba, has a plan that very few people living in the United States are aware of. It’s called “Tarea Vida” which literally means “Life Task,” and it’s Cuba’s long term plan to confront climate change.

Tarea Vida works first by naming the most at-risk populations and regions of the island and then lays out a chain of “strategic areas” and “tasks.” Climate scientists, ecologists, and social scientists are brought in to work in collaboration with local communities, specialists, and authorities to respond to specific threats. It’s been in play since 2017 and has targeted actions planned through the year 2100.

The government has instituted a series of measures to ensure that Tarea Vida’s goals are met. They include a ban on building new homes in threatened coastal settlements, reducing population density in low-lying coastal areas, developing new infrastructures adapted to coastal flooding, and adapting agricultural activities to the changes in land use caused by sea level rise. Reducing cultivation in areas close to the coasts, diversifying crops, planning the urban reorganization processes of the threatened settlements and infrastructures, and using lower cost measures like beach recovery and reforestation are also a part of the plan.

We also have a state and federal government with no real commitment to protecting them, or the people that have managed to continue inhabiting them despite ruthless displacement. Any policies that do exist are more so about maintaining the profits of golf resorts and wedding destinations.

This mentality is in direct opposition to Gullah Geechee culture, which was born rooted in cultivating non-exploitative relationships to the land. My grandmas, for example, are natural conservationists. They don’t collect more than they need, and almost every item that they own serves a multi purpose. However, the crisis of climate in the world today will require much more substantive solutions than crop rotation, storing

The first task of Tarea Vida is to protect vulnerable communities through relocation. The Cuban state foots the bill for relocation, including construction. However, relocation is not mandatory, and in instances where people have opted not to move, they’ve had the ability to propose their own strategies for adaptation. How is Cuba able to afford this? Well, as a socialist country, Cuba boasts the benefit of a planned economy. Unlike the United States, which leaves most economic planning to “free markets,” the Cuban government firmly regulates the economy, enabling real people to make practical decisions which will benefit society, not just profits.

Helen Yaffe, economist and author of We Are Cuba!, has written extensively about the other factors which make it possible for the island, facing a genocidal economic blockade by the United States, to invest in such an ambitious project. In addition to central planning, Yaffe highlights Cuba’s Civil Defense System. Instead of responding to troubling natural phenomena as they occur, Cuba stands on offense at the provincial, municipal, and neighborhood levels. Communities across the island are highly organized, with a system of procedures and tools to monitor, prepare, and act at the first sign of danger. As Cuban meteorologist Eduardo Planos has explained:

“Local governments set up local defense councils, which organise how the system works, distribute basic foodstuff so people don’t go without, and check electrical installations and the evacuation plan.”

On a practical level, this requires an intimate level of familiarity with your neighbors and all of those who live around you. Which homes contain elders? Young children with special needs? Who in the neighborhood is strong enough to carry sacks of rice? Who can command an audience and explain the plan? These are all questions Tarea Vida demands that citizens in Cuba’s most at-risk regions be able to answer. It’s much more than a 1800 number or fancy government office that may or may not answer the phone in the event of an emergency.

A 2020 review of the goals of Tarea Vida speaks to its effectiveness. Yaffe points out that, in just three years since its implementation, 11% of the most vulnerable coastal homes were relocated, coral farms had been set up, 380 km² of mangroves were recovered, serving as a natural coastal defense, and reforestation programs raised forest cover to 30% since 1959.

If you are a person that lives in the United States, you’ve probably been fed a lot of misinformation about Cuba. However, Cuba has accomplished all of this, even while facing massive economic and social oppression by the United States. Imagine what we could learn if we were able to cooperate with them without the threat of sanction and political repression. Cuba demonstrates the necessity of the working class taking control of the functions of the State. This is what many socialists call “the dictatorship of the proletariat.” In the Lowcountry, we live under the dictatorship of real estate developers and other industrialists whose personal interests are in direct contradiction with our lives. Before Cuban citizens were able to institute a life saving strategy like Tarea Vida, they had to band together to eject their ruling class from the driver's seat. For the sake of your children, and for the sake of my elder, there may be no better time for us to act than now.

Trouble in the Water

Forever Chemicals and Lowcountry Military Bases

WRITTEN BY RASHAD BROWN

During the great migration, large numbers of Gullah Geechee people relocated from rural communities surrounding Charleston to the industrial North area of present-day North Charleston. They came in search of jobs, benefits, and nearby housing for them and their families. What they didn’t anticipate was being exposed to toxic chemicals that would leave many dealing with terminal illnesses for decades. The Navy Yard, also known as the Naval Base, was the largest employer in North Charleston and the overall economic backbone of the city. While many have commented on the economic repercussions of its closure in 1996, what isn’t widely discussed are the levels of pollution and “forever chemicals” the base left behind that plague the people of the Lowcountry to this day.

Perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances," or PFAS, are more widely known as forever chemicals because they can take thousands of years to break down. They accumulate in the bloodstream, liver, and kidneys of those exposed and cause health problems like ulcerative colitis, thyroid disease, various cancers, myelomas and more. Evidence suggests that these chemicals can even be transmitted from mothers to babies via breast

milk as well as in utero.

Forever chemicals are used in various products from non-stick cookware to waterproof clothing. Due to their ability to effectively repel water and extinguish fires, the U.S. Military began utilizing PFAS in its fire extinguishing foam in the 1960s. This foam was regularly sprayed at Charleston’s Military bases during fire drills. A chemical mist was also used on the Naval Yard to reduce the amount of chromium emissions released into the air during the ship building process. The main two producers of the foam were Dupont and 3M. 3M first made discoveries about the toxic nature of PFAS during the 1950s. Both companies and the Food and Drug Administration conducted studies revealing PFAS to be toxic the following decade, yet the Navy only began to assess PFAS pollution in 2018. While Navy scientists noted the dangers of the extinguishing foam in 1976, they didn’t make the information public. Documents published in 2019 exposed that hazardous amounts of PFAS have made their way into the ground water beneath the former Naval Base. One test revealed PFAS amounts to be thousands of times higher than suggested limits.

In 2021, former Navy Fireman

Michael Sloan filed a lawsuit against 3M after he developed testicular cancer. Sloan had been exposed to extinguishing foams while stationed on the Navy Yard and various naval ships in the early 1980s. Both 3M and Dupont made multi billion dollar settlement deals following thousands of lawsuits from various individuals and water providers nationwide as PFAS contaminants have been found in bodies of water across the country. The latest Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) recommendations for the maximum amount of PFAS in drinking water is four parts per trillion (ppt). Charleston Water Systems says they will increase customers rates to meet these standards, but that may not be enough as PFAS in our waterways don’t just affect people.

Environmental Scientist Dr. Patricia Fair and her team discovered dangerous amounts of PFAS in Charleston area dolphins. The 2019 journal Environmental Research revealed PFAS rates in edible fish collected from the Ashley River averaged at 18,600 ppt. In a study from October 2022 the Department of Health and Environmental Control (DHEC) discovered PFAS in blue crab collected from the Ashley River near Northbridge Park at a rate of 69.03 nanograms per gram, which is more than three million times the EPA’s recommended limits. Blue crab, and other local seafood, are staples of Gullah Geechee diets and the high rates of PFAS present in Charleston waterways put people who fish these contaminated waterways at risk.

Although the Naval Base closed in 1996, the Joint Air Force Base in North Charleston still poses a continuing threat to the neighboring community and the nearby Ashley River. A 2015 study done by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) reported dangerous levels of PFAS in the area of the Air Force Base along the Ashley (and former Navy Yard along the Cooper River). This report also revealed levels of forever chemical sediments in Charleston are the highest of any urban area in the United States. The Joint Base ranks 10th highest for PFAS detected in ground water among over 700 military installations across the country. Although evaluations have been made–no clean ups have been started at or near Joint Base to date.

The forever chemicals crisis is only one of the many ways the U.S. Military pollutes the environment. The old Naval Base was also a major contributor of asbestos exposures which resulted in above average pleural cancer diagnoses among residents near the base, and especially among former shipyard workers. The U.S. Military is the biggest consumer of fossil fuels on the planet making it one of the largest emitters of greenhouse gases. The Joint Base in Charleston occupies 24,000 acres of land along 22 miles of coastline. From asbestos exposure, greenhouse emissions, to PFAS contamination, the U.S. Military is an active threat to the Lowcountry and its residents and we need to think critically about why we allow these toxic institutions to occupy our communities.

Sign the petition demanding state agencies release consumption advisories about PFAS contamination in locally caught seafood!

PHOTO | Joshua Parks

PHOTO | Joshua Parks

JOURNALISM

Make a one-time, monthly or annual donation to Charleston City Paper

WRITTEN BY MOSIAH ASAD

Ringworm

“De wata bring we and de wata gwine tek we bak.”

-Gullah Proverb

as close as we live to the ocean ain’t nobody got gas for the beach, so we be excited for rain, for floodwater. my mama don’t be, come ya out that water, fool ass

she won’t say it, but I listen so I know our elders were eaten alive, done by cancer they say, but we say a body betrayed, zoned for sacrifice by poisoned land and overworked hand. they had the best recipes and the meanest truths. now they haunt the air, they heavy it, sitting prematurely on a humid spirit plane.

they whisper

Ringworm, Ringworm but i’on wanna turn my head i’on wanna see my granny receded into herself, a deflation of the women who had master the earths ways of wastelessness and the waters way of weightlessness. with them went our greatest rituals. we were church people outside the Church. we used to meet in the clearing, the swamp-like, land-water with our New Afrikan water-ways

i want to step in their pluff mud prints, sink and sink until i find lost ingredients: sweetgrass, bullrush, pine, palmetto is it not ours? the river roads have our prints, as many of us drowned here, the rivers that rides em are bodyfilled-bountiful kin but i hear my mama now

the boy playin in that flood watta again churn be missing what they never held themselves we smell the brackish on our daddy’s breath, the salt in the wake of his step, we be ready to pull jumping fish scales from our skin, to be robed in light, dirt, and the attention of our knowing fathers. our mother’s

they speak of running the yard barefoot, sugar cane in mouth, honey suckle in sight, watermelon on deck, hands stained with granny’s berries, the water calling them by nickname now all we get is get out that floodwater, that’s why dem boy call you ringworm, now and don’t drink that tap, they can’t answer our pleading how comes, maybe it’s the same way we can smell the sky about to open, and can’t help but plot our play,

our brown-water baptism reminds us of how they shipped nana n ‘nem from marsh field to factory, how we are stream softened and river roughed people who better reintroduce themselves to the tides that will swallow us first

PHOTO | FLOOD BY BRITTNEY WASHINGTON

Invest in local journalism

Charleston leader Paul Stoney believes in the importance of having strong independent voices in journalism to challenge the status quo, strengthen democratic institutions and spread news that connects people to their communities.

“Independent newspapers like the Charleston City Paper prove they are committed to building inclusive, dynamic communities by publishing stories like those that outline the historic importance of the new International African American Museum. Support South Carolina’s independent journalists with a gift today.”

Paul Stoney, president and CEO of the YMCA of Greater Charleston, supports the Charleston City Paper’s community journalism initiatives. Photo by Ruta Smith.

The Lowcountry Action Committee Charleston Climate Coalition

Freedom Bag Food Drive

The Lowcountry Action Committee hosts a monthly Freedom Bag Food Drive every 3rd Saturday of the month and our August 2024 event will be a dual food and back to school drive!

Make a tax deductible contribution and help us purchase food and school supplies for our community!

LAC Sponsorship Levels

Platinum | $1000

Gold | $500

Silver | $250

How to Donate

Venmo @LcTakesAction

CashApp $LcTakesAction

Questions

Email LcTakesAction@gmail.com

It is an honor and a privilege to serve the people!

Thank you for your support!

Charleston County Climate Action Plan

Help drive local climate action by supporting the Charleston County Climate Action Plan! The County CAP is an important guiding document for investment in green & affordable buildings, public transportation, clean energy, and more.

Here's how you can support:

1. Sign and share the petition

2. Help get local organization sign-ons — if you have a connection or are part of a local organization that would like to see climate action please pass on our letter sign-on page.

3. Reach out to your local County Councilmember and tell them you support the CAP.

4. Follow Charleston Climate Coalition on Instagram or Facebook for updates and other ways to get involved.

5. Check out a full list of the CAP actions

Scan this QR Code to take action now!