Belvin Olasov Co-Editor in Chief

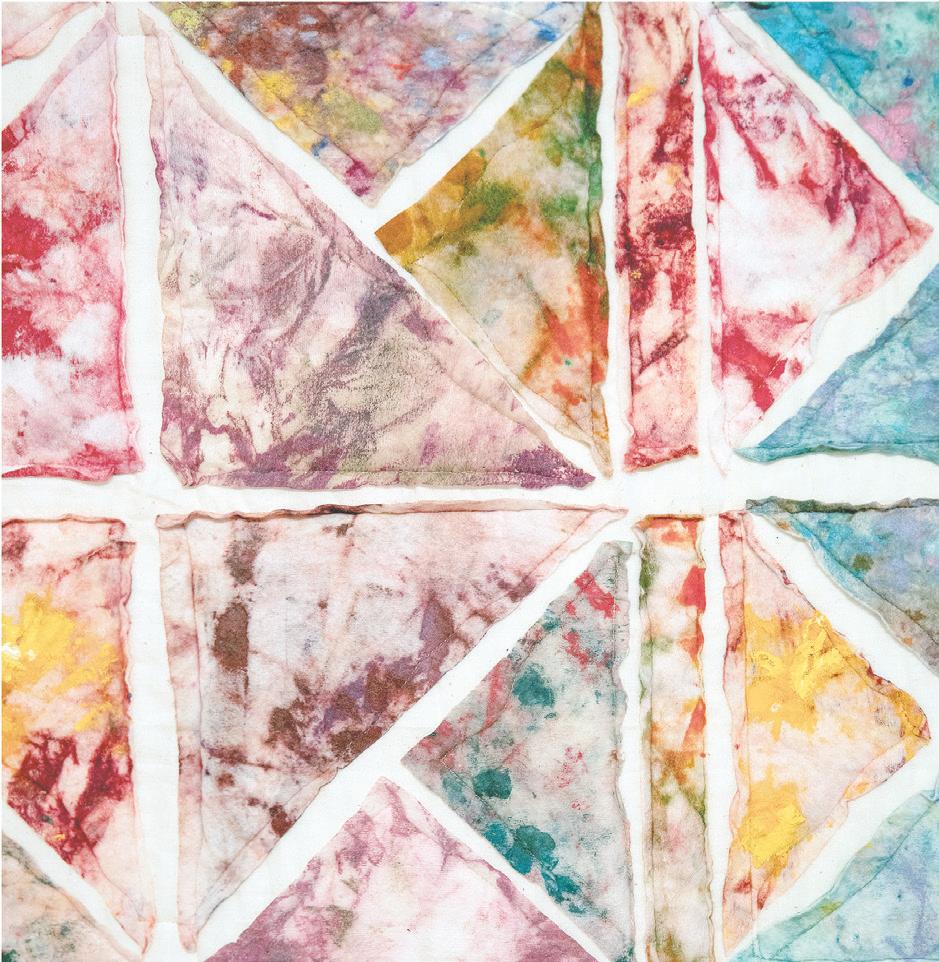

Ester Araujo is a multidisciplinary artist currently based in the Charleston area of South Carolina.The methods she uses to execute ideas are heavily influenced by nature, textile processes, and animated films. Araujo’s work explores connections between rhythms in nature and mark making.

Find her work at esteraraujo.com or @esteraraujo on Instagram.

It takes a village to protect a village. I’m grateful for the many partners, like CCL, SELC, and Mary Edna Fraser, who contributed media to this issue of Surge diving into the 526 extension and its consequences.

If you’re reading this and want to make the ecofriendly, climate-conscious, or just the fiscally responsible choice, vote no on Special Questions 1 & 2. If you think you want the 526 extension, I urge you to read on. To invest in this highway would be to lose what is most precious in the Lowcountry, and for nothing.

Love, Belvin Olasov, Surge Co-Editor in Chief

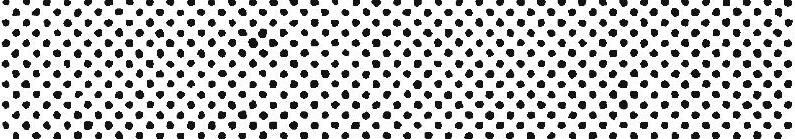

I-526, also known as the Mark Clark Expressway, is the highway connecting Mount Pleasant to North Charleston that ends around Citadel Mall in West Ashley. It ended there in the 80’s because of the environmental permits that would’ve been required to fill in the wetlands along the Stono River.

For the next couple of decades, an extension plan was pushed: to bridge West Ashley over the Stono River to Johns Island then on to James Island, where it would tie into the James Island connector at Folly Road.

This vision was scuttled in 2015 when the state infrastructure bank balked at the price rising to $725 million. (Which, to save you a calculator trip, is less than a third of the current estimated cost.) But even though the state lost interest in the project, Charleston County government did not, and has continued their attempts to push through the extension.

Now, the 526 extension would be the only priority project on the new $5.4 billion half-cent transportation sales tax referendum. By a 2021 estimate, it would cost $2.3 billion.

On your ballot, Charleston County is proposing a 25-year transportation sales tax that would primarily fund the destructive Mark Clark (I-526) Extension, a new highway that would plow through James Island County Park and historic African American communities, destroy wetlands, and exacerbate flooding and traffic, especially in the busy downtown medical district. Charleston County has only finished one project from the 2016 sales tax—they clearly cannot be trusted with our taxpayer dollars.

Vote no on local questions 1 and 2.

Explore the impacts on our interactive map.

This election, many Charleston voters are going to be voting on the 526 Mark Clark extension without having any idea they’re voting on the 526 Mark Clark extension.

At the end of the ballot, they’ll be asked to approve a half-cent sales tax for the next 25 years, $5.4 billion for transportation projects and greenbelt funding. But what isn’t made clear in those questions is that the only priority project for the tax, and therefore the only piece guaranteed to be built, is the $2.3+ billion 526 extension to Johns Island. Instead of focusing on more targeted road improvements, walk/bike infrastructure, mass transit, and greenspace funding, the priority funding will go to a hyperexpensive road project that the state wouldn’t bankroll.

“We call them zombie projects, because even when you think that you’ve killed it, it comes back,” said Emma Berry, Communities & Transportation Manager at the Coastal Conservation League, which has been a longtime opponent of the extension.

Berry sees the 526 extension project as expensive and ineffective. She points out that there are a host of smaller, more targeted road projects that the County has neglected for years that could more directly help with traffic, like the $15 million James Island intersection improvements or the $52 million Maybank Pitchforks.

“I think we’re just thinking about this in the wrong way. The traffic issues that we’re seeing on Johns Island are because of the lack of a road plan on Johns Island. There are other very significant changes that need to be made throughout the infrastructure on the actual island that would alleviate a lot of the traffic,” Berry said.

But more than wasteful, she sees the project as destructive. Environmentally, it’s projected to remove 38 acres of wetlands and 46 acres of the north side of James Island County Park, where the climbing wall currently stands. Then there’s the threat to Johns Island’s rural character – already beset by overdevelopment, the concern is that putting several new traffic lanes

Fi

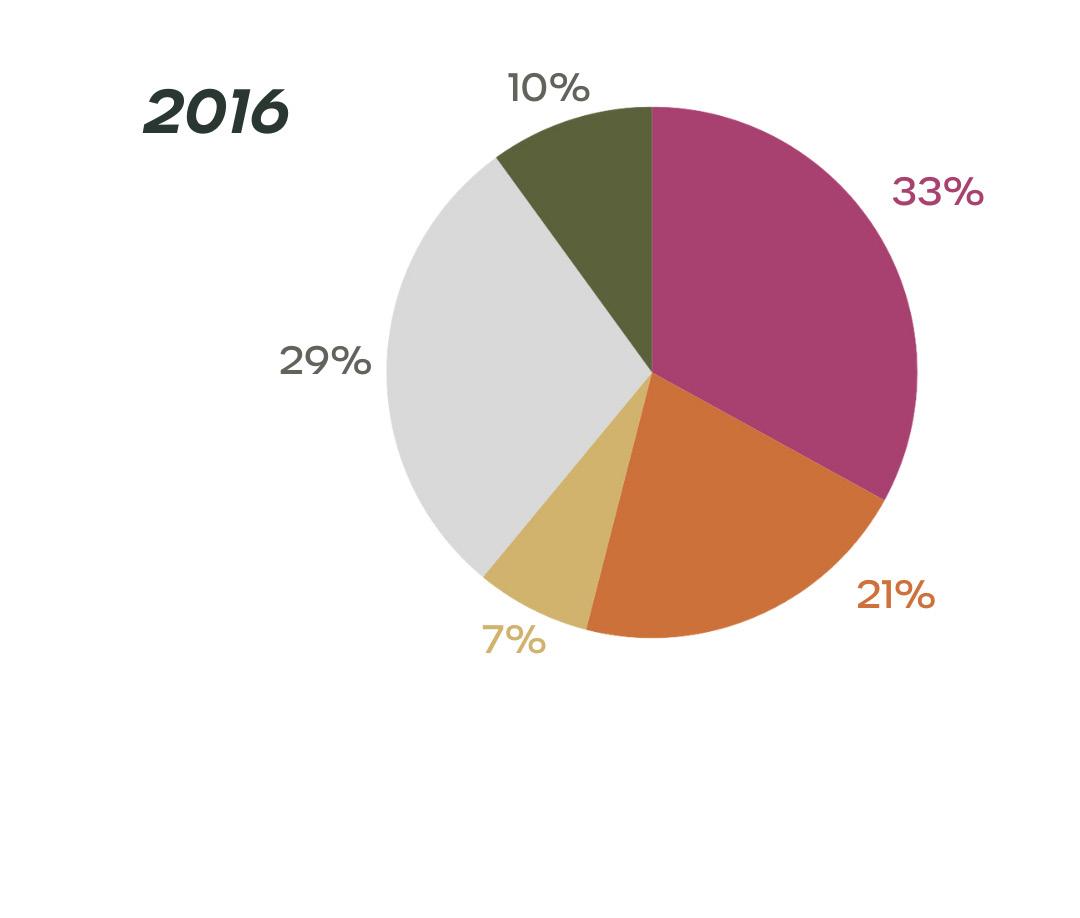

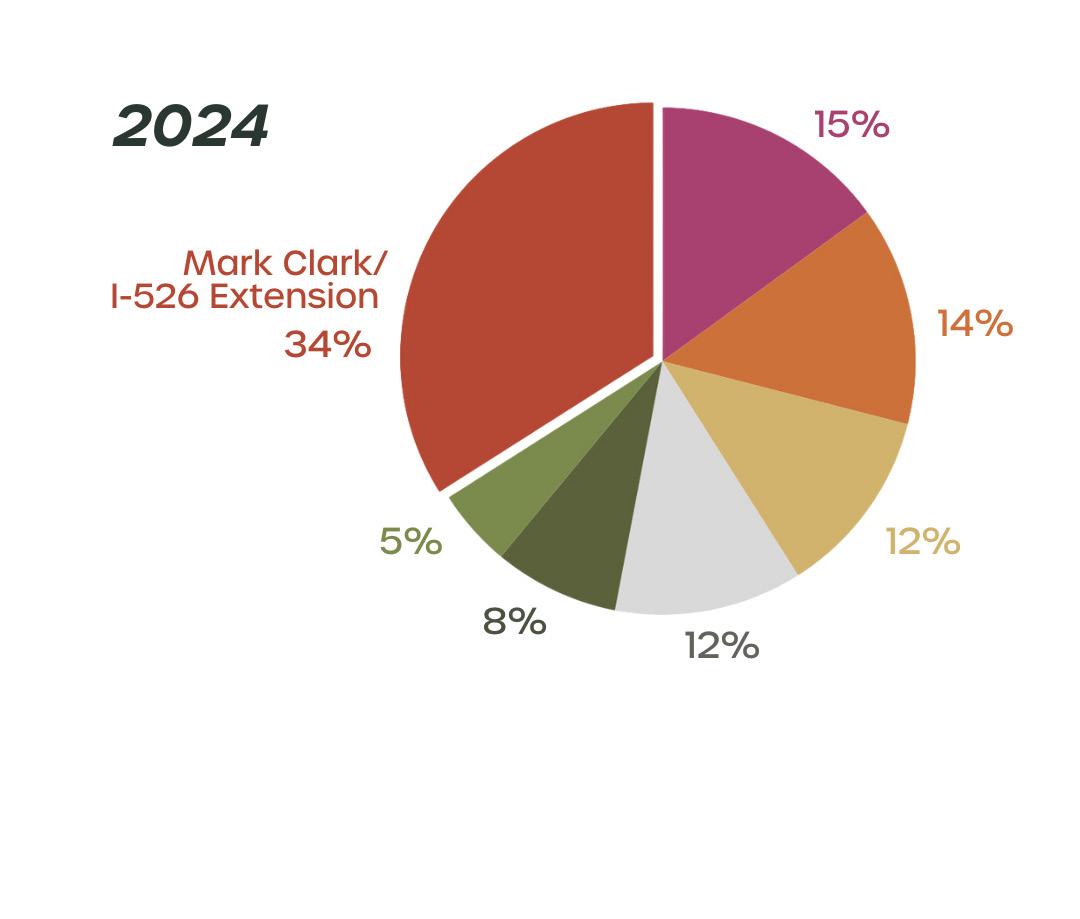

The Transportation Sales Tax up for a vote now has very different priorities than the 2016 tax we’re currently paying. CARTA funding for public transit as a share is down from 29% to 12%, and the Greenbelt Program is down as well.

on and off it would send development into overdrive. And the project would seize 92 parcels of land through eminent domain, many from Black settlement communities.

“Looking at where the interstate or expressway is expected to go, and where these communities are, it’s pretty much just African-American communities that are going to be impacted,” Berry said. “There’s a couple other places, but it’s almost like they just drew the line right through these communities. They said they have like 36 to 39 alternatives, proposals, and routes, and then the one that they picked somehow seems to be affecting these communities most.”

The Coastal Conservation League and a number of other environmental partners like the Southern Environmental Law Center and the Charleston Climate Coalition (handsome producer of this magazine) and community voices like Nix 526 have been getting the word out on the issues with the project. But many folks with congested commutes in West Ashley, Johns Island, and James Island see the gridlock around them and say Something Must Be Done.

How much would the Johns Island 526 extension actually help traffic? Is the projected environmental damage really so severe? And how would 526’s buildout affect vulnerable communities in Johns and James Island?

Susan Handy, Director of the National Center for Sustainable Transportation and professor at the Department of Environmental Science and Policy at the University of California at Davis, is an expert on the relationships between transportation and land use and on strategies for reducing automobile dependence. Her work involves looking at smart growth, cycling and ebikes as a transportation solution, and microtransit (like on-demand shuttles) – cutting-edge alternatives to the car culture we have in the US. That has not left her impressed with the efficacy of highways.

“Expanding highways does not reduce congestion except in the very short run. So it’s a really expensive and also very temporary solution to the problem,” Handy said. “What the research shows is, on average, you’re back to where you were in about five years.”

That’s the mechanic of induced demand, where new lanes of traffic lead to more cars on the road, nullifying any potential traffic benefit. It’s been a known phenomenon since the 60’s, and yet DOTs and highway advocates continue to apply highway expansion to traffic congestion like hammers to nails.

Handy breaks down how induced demand works like this:

“So if you expand or extend the road, you are increasing capacity. And what that does in the short run is reduce travel times, which is like reducing the cost of driving, because a big part of the cost of driving is the time that it takes. So what do people do if you reduce the cost of something? They tend to consume more of it. And that’s exactly what happens – people adjust their choices about

travel in ways that end up increasing the amount of driving, and within a few years you’re back to similar congestion levels as you were at the beginning.

“You’re spending a whole lot of money for that short term benefit. Not to mention the fact that you have to live through the construction,” she said. “The construction itself is gonna make congestion worse for a while. So you want to factor in the pain of the congestion versus that short term benefit you get once the congestion’s finished.”

Handy believes what actually reduces traffic is a combination of pricing the road and offering viable alternatives, like public transit or bike infrastructure – or better yet, reducing the need for long trips in the first place.

“Reducing congestion, I think, is the wrong way to think about the problem. Congestion has been a fact of life in urban centers for 150, going on 200 years. It’s a natural part of a vibrant economy… that’s not how we should be thinking about the solution,” Handy said. “Instead, we should be thinking about giving people alternatives to being stuck in traffic. And that could be transit. It could be walking. It could be biking. But it could also be not having to drive as much and not having to drive as far.

“We do things differently with our land use so that people don’t need to drive such long distances to get what they need. That’s another way to solve the problem. If you never have to get on a freeway, you don’t care about the congestion on the freeway.”

Fi

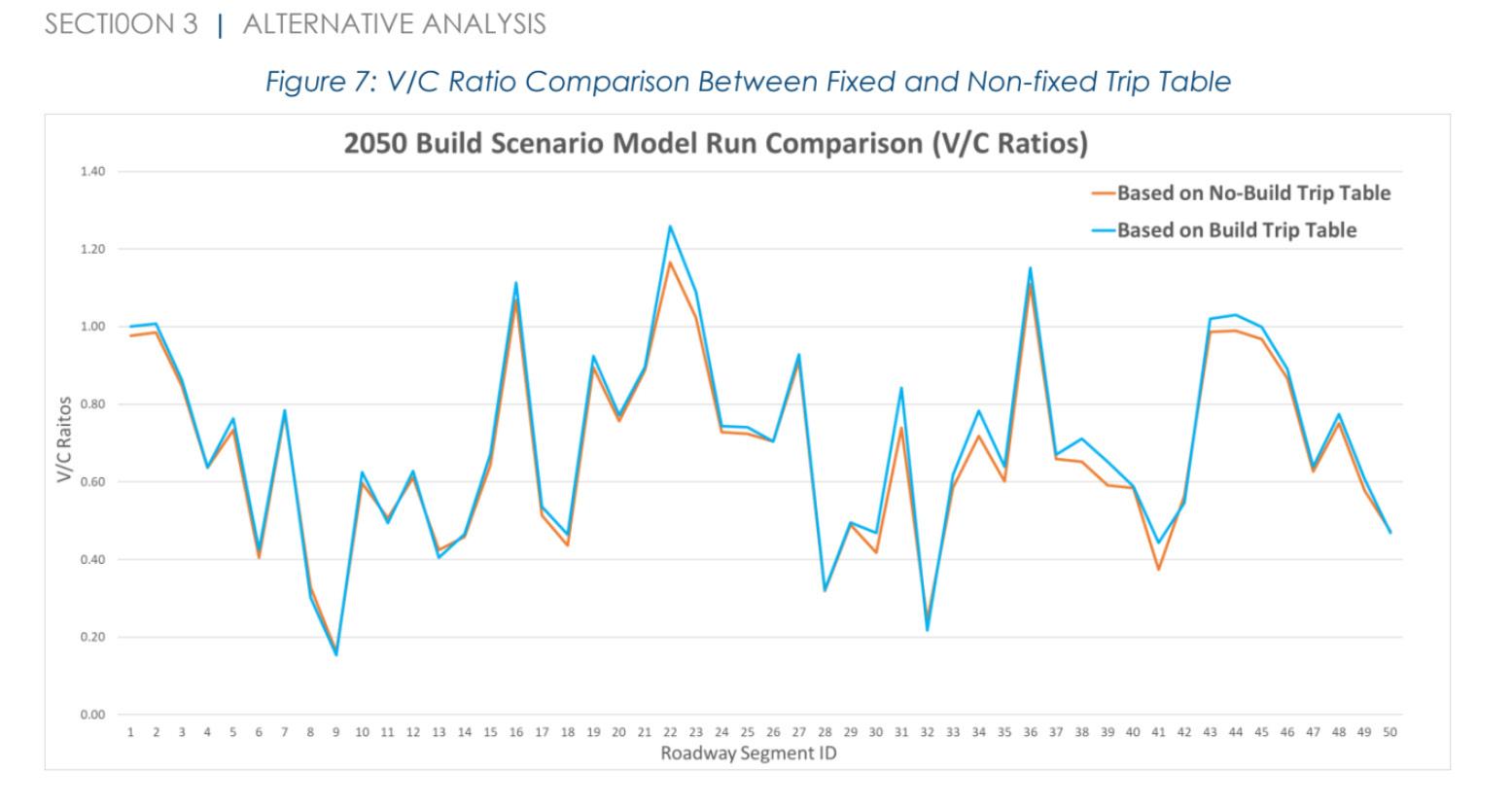

This graph is from the County’s official environmental impact report showing the difference in traffic congestion with and without the 526 extension.The graph summarizes 50 different trip simulations across West Ashley and James and Johns Island, with the travel times shown in orange (Build 526) and blue (No Build 526). As you can see, it’s a tiny difference – just a 1% change.

Source: Select Appendix D: Travel Demand Modeling Technical Memorandum off of scdotmarkclark.com/documents

FEATURES:

Interdisciplinary courses with expert faculty

Networking with environmental professionals

Preparation for diverse sustainability careers

Hands-on experiential learning • Immersive field trips• Research and thesis projects • Internships

Scan the QR code to learn more about the EVSS program at CofC!

Scan the QR Codes to learn more!

When Dr. Phillip Dustan, a marine ecologist and biology professor at CofC, is not spreading the word on the vulnerability of coral reefs, he’s occupied with the impact of urbanization on the watershed ecology of coastal waters. He sees the 526 extension as an incredibly foolhardy move that would endanger a crucial ecosystem. The Stono River that snakes around Johns Island is classified as shellfish collecting habitat (SCH), which means that the water is sufficiently clean for shellfish to be safe to eat from it.

“We think of our salt marshes as precious, and they really are. They’re nursery grounds for virtually all the commercial and recreational fisheries that we have… birds, turtles, mammals, you name it. The plants that live there tend to purify the environment,” Dustan said.

As a Johns Islander, he’s observed the effect of the existing bridges connecting Johns Island to the mainland and the way they deaden the nature around them.

“Look under the Maybank Bridge, which goes over the Stono River. The first thing you realize when you walk alongside it is there is road trash everywhere. And there’s a well-defined edge that seems to reduce the growth of plants,” Dustan said. “When you go underneath, there’s basically an ecological dead zone.”

There are no requirements for runoff mitigation on SC bridges, and so pollutants from car travel are dumped directly into the water and marshes below. That’s gasoline, motor oil, and tire pollution, not to mention the 1000 different pollutants gas vehicles emit, from Carbon Monoxide and Nitrogen Dioxide to heavy metals like Cadmium and Zinc.

But the impact on the local ecosystem from new highways and bridges doesn’t just come from runoff. The concept of a “roadway corridor” means recognizing how impact can be much wider than a road’s width, depending on whether it’s upslope or downslope, upwind or downwind, and what wildlife is around it. A road can have an impact of up to a kilometer (over half a mile) around it in terms of its damage to ecosystems. And where 526 is supposed to extend, there would be a lot of affected wildlife.

“Grass shrimp that live around roadways within 100m will show reduced reproduction in the marsh. Birds don’t like to nest within a quarter mile because of the noise,” Dustan said. “Songbirds like to live at about the level of noise as you have in a library, and when that noise gets to 42db, that reduces their reproduction. Earthworms that live along the side of roads – when the ground vibrates, they’ll come out of the ground and there will be more animals feeding on them.”

Dustan worries that the base of our coastal foodchain, the larvae of the marsh, will be overcome by pollutants and disruption. That would ripple up to fish, shellfish, birds, mammals, and the humans who fish and hunt them. Runoff pollution from elevated highways can be higher than that of untreated municipal wastewater.

“When an activity raises threats to harming human health or the environment, we should say, it must be shown that this will not harm anybody,” Dustan said. “The precautionary principle is what we need to apply when we begin to do development projects of this sort.”

The history of 20th century highway expansion is one of Black neighborhoods across America being plowed through, chopped up, and cordoned off by highways. Now, Black settlement communities on Johns and James islands, including Ferguson Village and Cross Cut, are facing displacement and pollution. One slated taking from the 526 extension, 1950 Delaney Drive, exemplifies the massive human cost of the project.

Delaney Drive has hosted Candace Ackerman’s family for six generations. Nestled within marsh and forest, she came of age playing on the dirt road, surrounded by family homes. Her grandparents farmed watermelon and corn. She’d go out in the woods to pick blackberries and grab figs and pecans from the trees. Wandering out to Riverland Drive was forbidden; Delaney Drive was her safe space.

“I grew up on Delaney, so this area has been a part of my life forever. I’m 57 years old now. I have raised my two daughters in this area. Now I have two granddaughters. So the peace and tranquility associated with this area and just the idea that it could all be disrupted by 526 is just sickening and disheartening,” Ackerman said.

The Godfrey and Richardson families have been in the crosshairs of the project for decades. Ackerman, her grandmother, her granduncle Isaac Godfrey, and the rest of the Godfrey and Richardson families were relieved when they fought 526 to a standstill in 2016. But now her grandmother and granduncle have passed, and the family property is once again under threat.

The James Island touchdown would land through the back property and around the front, placing a highway directly along Delaney Drive and its homes.

Despite this massive impact, Delaney Drive’s residents have yet to be contacted by the County.

“I hadn’t heard of any mention of any noise barriers for the residents. I feel like they’re just dismissing us and say, just deal with it, this is what we’re gonna do and that’s that,” Ackerman said. “There’s been no conversation with them in terms of getting our feedback or our thoughts and our feelings about this whole project. Never one.”

The human health consequences from proximity to highways are well documented. Living within 300 feet of a main road is associated with a higher risk of mortality from stroke and an increase in the risk of wheezing illness in children.

Ackerman’s granddaughters come out to Delaney Drive to play and visit their grandma the way she did when she was a girl. The oldest’s favorite thing to do is come out on the family dock and catch crabs. Ackerman isn’t sure what the future of the property is for them.

“It’s gonna impact a lot of people. A lot of people. And I just really don’t understand why,” she said. “That should be a deterrent within itself, just the idea of how many folks this will potentially impact. That should be the quick answer to say, hey, we can’t do this.”

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

The history of 20th century highway expansion is one of Black neighborhoods across America being plowed through, chopped up, and cordoned off by highways. Now, Black settlement communities on Johns and James islands, including Ferguson Village and Cross Cut, are facing displacement and pollution. One slated taking from the 526 extension, 1950 Delaney Drive, exemplifies the massive human cost of the project.

Delaney Drive has hosted Candace Ackerman’s family for six generations. Nestled within marsh and forest, she came of age playing on the dirt road, surrounded by family homes. Her grandparents farmed watermelon and corn. She’d go out in the woods to pick blackberries and grab figs and pecans from the trees. Wandering out to Riverland Drive was forbidden; Delaney Drive was her safe space.

“I grew up on Delaney, so this area has been a part of my life forever. I’m 57 years old now. I have raised my two daughters in this area. Now I have two granddaughters. So the peace and tranquility associated with this area and just the idea that it could all be disrupted by 526 is just sickening and disheartening,” Ackerman said.

Despite this massive impact, Delaney Drive’s residents have yet to be contacted by the County.

“I hadn’t heard of any mention of any noise barriers for the residents. I feel like they’re just dismissing us and say, just deal with it, this is what we’re gonna do and that’s that,” Ackerman said. “There’s been no conversation with them in terms of getting our feedback or our thoughts and our feelings about this whole project. Never one.”

NOV. 1-10

SESSIONS

The human health consequences from proximity to highways are well documented. Living within 300 feet of a main road is associated with a higher risk of mortality from stroke and an increase in the risk of wheezing illness in children.

Ackerman’s granddaughters come out to Delaney Drive to play and visit their grandma the way she did when she was a girl. The oldest’s favorite thing to do is come out on the family dock and catch crabs. Ackerman isn’t sure what the future of the property is for them.

The Godfrey and Richardson families have been in the crosshairs of the project for decades. Ackerman, her grandmother, her granduncle Isaac Godfrey, and the rest of the Godfrey and Richardson families were relieved when they fought 526 to a standstill in 2016. But now her grandmother and granduncle have passed, and the family property is once again under threat.

The James Island touchdown would land through the back property and around the front, placing a highway directly along Delaney Drive and its homes.

“It’s gonna impact a lot of people. A lot of people. And I just really don’t understand why,” she said. “That should be a deterrent within itself, just the idea of how many folks this will potentially impact. That should be the quick answer to say, hey, we can’t do this.”