Shona McAndrew ROSE-TINTED GLASSES

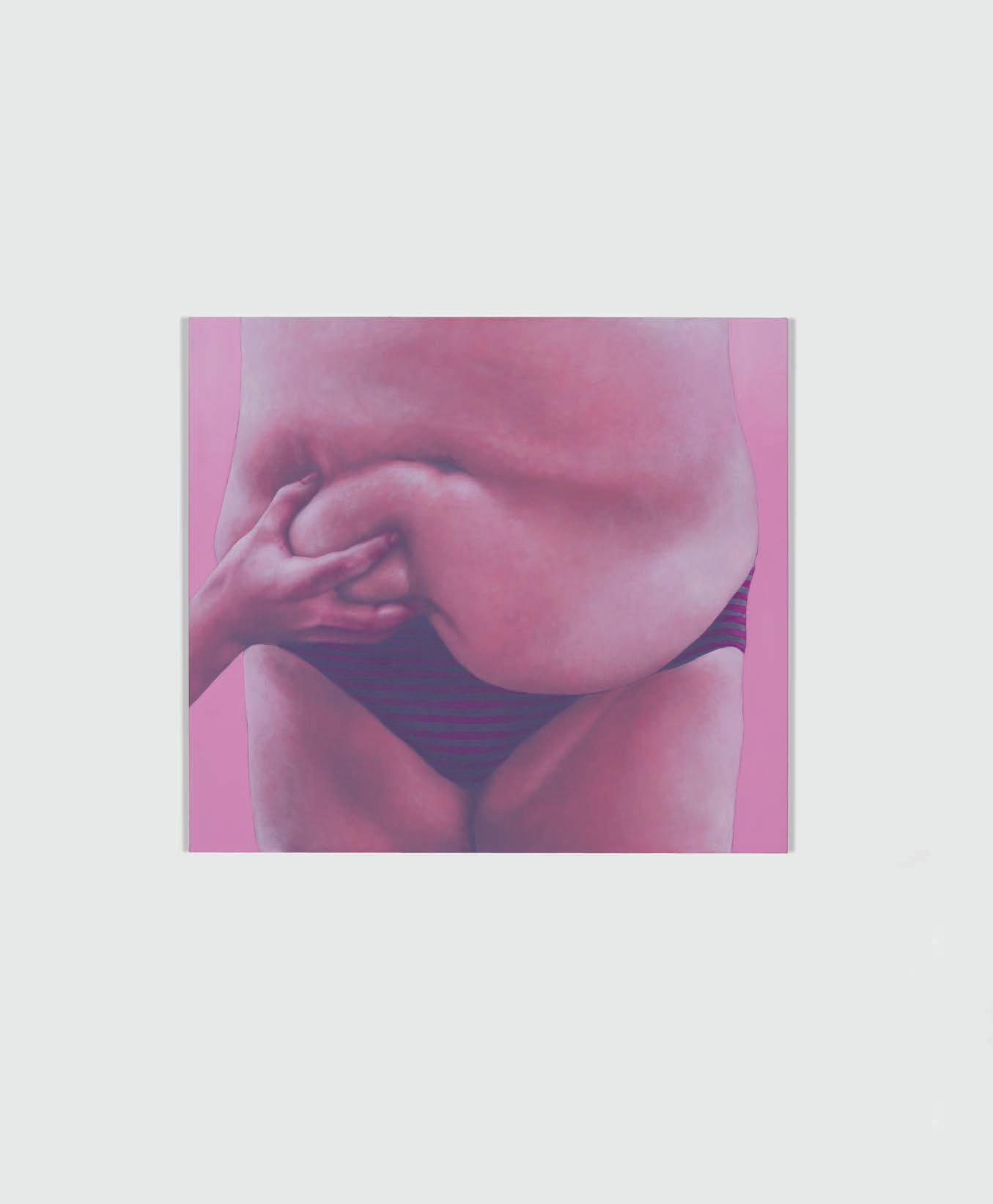

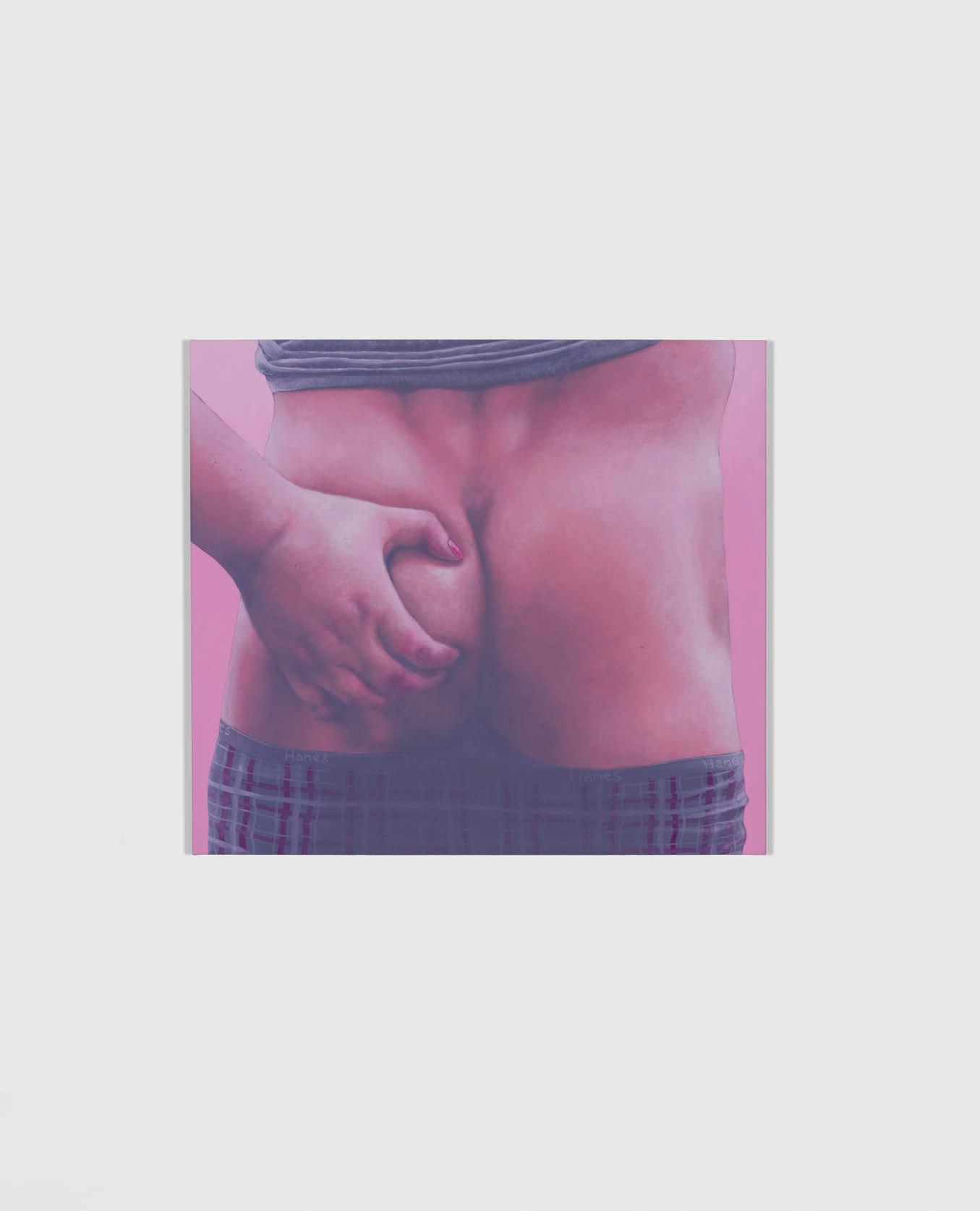

I have always struggled with touching and being touched. As a child, I would even recoil from my mother’s loving caresses. Being touched always felt like an uncomfortable breach of my personal space. The most distressing being the violently nauseous discomfort of having my belly button prodded. So I started by painting my boyfriend poking my belly button.

In searching for references, I found myself drawn to the Baroque sense of drama. To this point, I had eschewed action from my work. Not wanting my work to feel like it depicted a moment just before or after an event, the paintings remained suspended in a contemplative but unchanging present. To begin incorporating action, I started looking to artists like Caravaggio and Bernini, masters of high drama. I wanted to transform their morbidly murderous compositions into tender embraces and moments of affection, taking what is culturally coded as masculine violence and re-present it as feminine tenderness.

In titling the show “Rose-Tinted Glasses,” I hoped to accentuate this tender approach to the work. As a fat woman, society tends to essentialize me in a distinctively negative light. For a time, I came to believe that I didn’t deserve intimacy, shouldn’t express happiness in the presence of others and certainly should not be proudly showing my large naked body to anyone, let alone a global group of art loving strangers. This body of work hangs in defiant opposition to this view. “Rose-Tinted Glasses” embodies this new approach towards myself, looking lovingly at my double chin, a floppy boob or a handful of my belly fat.

I have been thinking a lot about what it means to be vulnerable, both as an artist and as a woman.

A virtual studio visit with Shona became an immersive discussion about the artist’s life and work. She is a talkative introvert with a rhythmic and assured manner of speaking. Our conversation came on the heels of her therapy session. She was unfazed by this and dismissed my question of whether she needed a minute before we started. As she strolled around the studio showing me her paintings and the sculpture in progress, her partner Stuart was working in the background. They’ve been together for seven years. Their two dogs, Charlie and Lily, were sleeping side by side. Soft pink chairs, an orange velvet couch, and strewn pillows added to the usual studio disarray. The scene was one of contentment and purpose. Shona spoke enthusiastically about her family’s impending visit over the holidays and how she looked forward to having them there while she worked. She adores her family. She speaks to her brother every day and she reveres her mother who in turn is fully supportive. It’s an astonishing and enviable amount of fondness, and this is what informs her practice—all the love.

SHONA McANDREW’S career began with self-portraiture but she has spent recent years painting and sculpting other women. Two previous solo shows at CHART, Haven (2021) and Muse (2019), privileged the female gaze and sisterly camaraderie with an emphasis on body positivity. These new works of Rose-Tinted Glasses are no exception, but now it is the artist’s turn to become subject and object, and to demand the same vulnerability from herself as she did from her models. In 2017, Shona made a small-scale sculpture of a woman in a bathtub, called Elizabeth (her mother’s middle name), based on her mother’s memory of noticing her body changing while pregnant. For years Shona wanted to make a life-size version of that sculpture, and now she has. The result is her own likeness in the bath, a papier-mâché figure that is eight feet tall when upright. The full breasts and physique summon a joyous version of a prehistoric figurine, albeit one in a rapture of pearly bubbles. Sculpting the human form is a means to get at something both immediate and undying—to become both “creator and source,” to quote Frankenstein

It can be a way to apprehend our own fallible monstrousness, lay waste to our enemies, and, in a roundabout way, to stake a claim to inviolability.

I am reminded of Kate Millett’s Naked Lady sculpture of a giantess installed atop the Los Angeles Woman’s Building in 1978, or Kara Walker’s scathing sphinx, A Subtlety (2014). Reimagining stories and selves through tactile ventriloquism, our hands externalize what goes unsaid (or is unsayable).

“The bathtub sculpture is coming together and I’m already falling in love with her. We just figured out the pedestal she will be displayed on and I can’t wait to see it. From her checkered tiled pedestal to a pinkish bubble bath, she is going to be glorious! Cross my fingers and toes. She is the largest sculpture I’ve ever made.”

Shona McAndrew, 2022

“Happiness! Delight!

My figure is a woman standing and weeping, her head in her hands. You know that movement of the shoulders when one cries.

I wanted to kneel before it. I said a thousand absurdities. The sketch is half a yard high, but the statue will be life-size. It will be a defiance to good sense. Really; why?

[...] I like this clay better than my skin.”

Marie Bashkirtseff, 15 February 1883

Shona’s new paintings loosely summon an art historical lineage, borrowing from canonical works by Artemisia Gentileschi (Mary Magdalene in Ecstasy, ca. 1613-20), Caravaggio (The Incredulity of Saint Thomas, 1603; Narcissus, 1597-99; and Judith Beheading Holofernes, 1599), Gian Lorenzo Bernini (The Rape of Proserpina, 1621-22), Michelangelo (Pietà, 1498-99), and Diego Velázquez (Venus at Her Mirror, 1647-51). Shona’s renditions of these works, based on allegories of religion, mortality, and vanity, feature stagings of herself, her partner Stuart, their pets, and her mother. These compositions are downtempo homages to connectivity, yet there is a quiet drama:

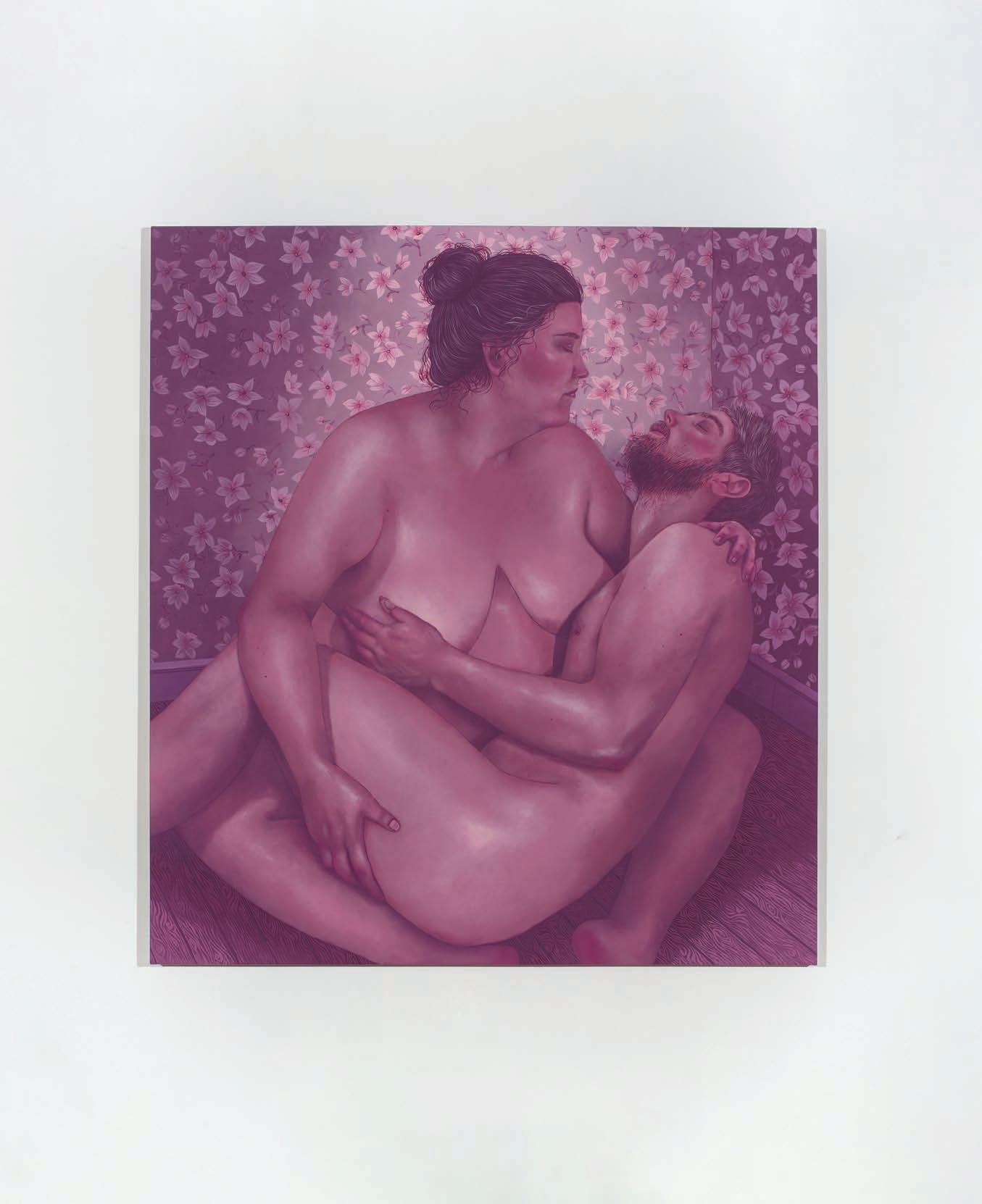

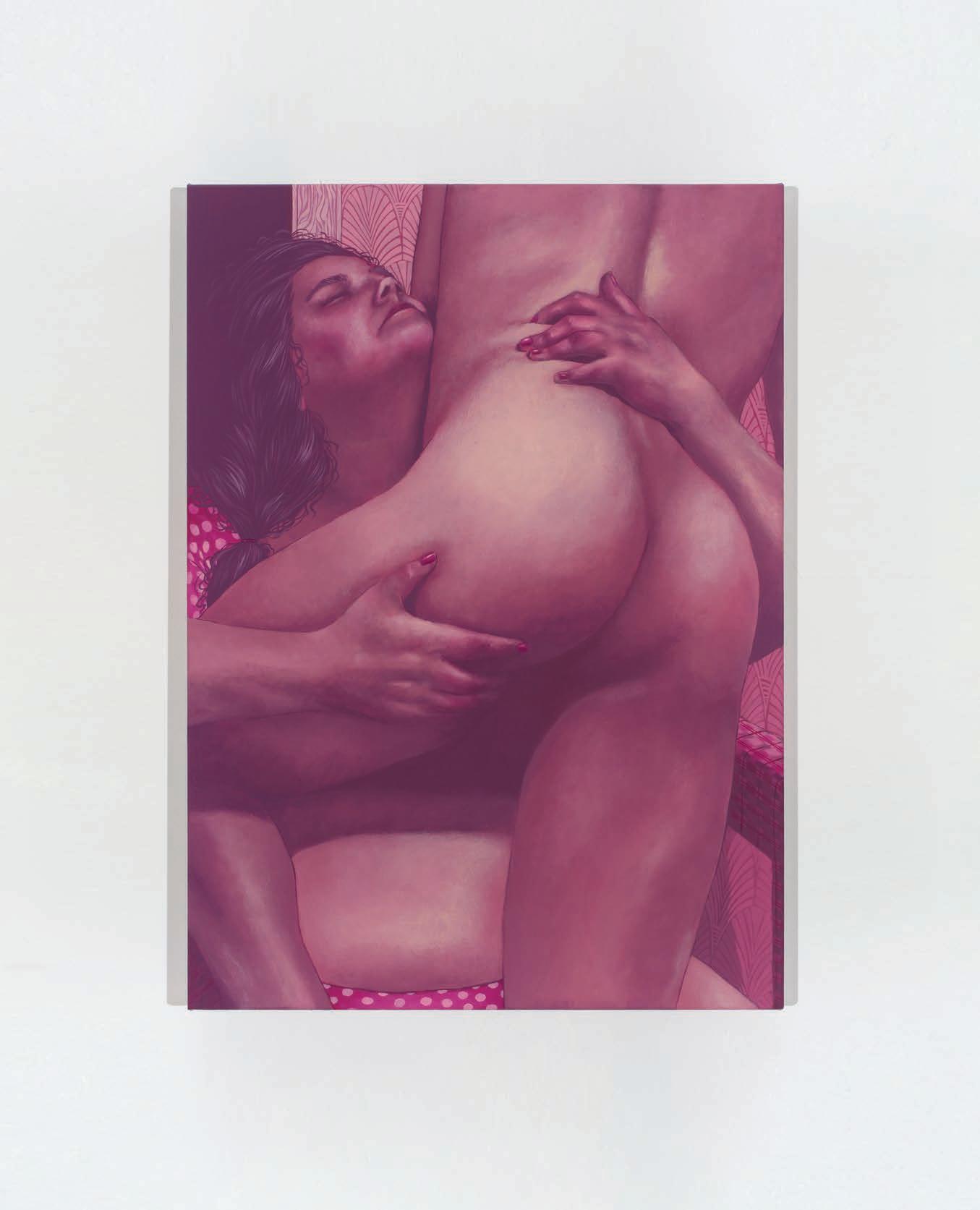

a room full of nude self-portraits is liable to have an effect, no matter how seemingly nonchalant. Touch is not predicated on suspicion when we see the artist and Stuart enacting a gesture from The Incredulity of Saint Thomas. His finger jabs into her navel through belly folds—nothing as grisly as St. Thomas’s skepticism of Christ’s wound, yet there is uneasiness in having one’s belly button prodded. The umbilicus, a severed channel to the mother’s nourishment. Too sensitive, like a fontanelle that doesn’t quite ossify. Nerve endings that remember what we don’t.

The body is a site of shared knowledge (seeing is believing)—and the artist’s hands connect us to her sensuality and dexterity. Touch is everything in these new works. Giving and receiving. Viewers might perceive egotism or bravado in a series of nude self-portraits, but let’s remember nuance in our time of brazen performativity. Confidence and peace with oneself is hard-won here: Shona went nearly a decade without looking in the mirror before unlearning timidity and body dysmorphia. She says: “I grew up very uncomfortable with being touched; perhaps that has to do with being neurodivergent.” Being touched also impinges upon the cocoon of solitude that keeps us “safe” from others. It’s no wonder that as a child, Shona was an ardent reader who retreated into books. When she says she is an introvert, she means it. “My life is very insular. I don’t need a lot of stimulation or experiences that other people have to feel very complete.” There is a wisdom in this that lends itself equally to imperviousness and heightened sensitivity.

Now the artist fills a room with nascent self-reckoning. These new paintings and the bath sculpture are “the first steps in a long career where I will invent my own worlds and feel very free in them…” Loved ones are included in those worlds. In this sense, art is a means of outing one’s interiority and publicly sharing it. Overcoming her fears has been a long process for her. Using mimesis as a means to infiltrate or skew, Shona’s new works insert herself into the frame. She cites Devan Shimoyama’s work as an enviable example of fabricating one’s own worlds (and thriving). Comfortable embodiment is a fraught prospect for many people, but being fat means

Gian Lorenzo Bernini, The Rape of Proserpina, 1621-22 Shona working on Molliebeing susceptible to othering. Being othered leads to erasure. “I disassociated from myself for a long time, like I was a cartoon or not an actual human being… things that happened to others couldn’t happen to me because I’m not someone that something happens to. From finding a partner to having a career, I envisioned nothing for myself. Maybe this show is also a way for me to deal with my material form.”

Consider what’s at stake: a lived life. Sincerity and care. Offerings are not taken lightly. The lovers respect each other and inhabit the work. There’s a fullness in the rosy canvases that hold all the fervor of hard and fast brushstrokes. The paint is flesh. Stomach fat is clenched in a fist; a handful of buttock is firmly gripped. We are invited to look closely, and then closer. Positions alternate, scale changes, and bodies shift.

Painting takes a cue from sculpture. Smaller canvases depict tightly cropped details of larger ones, but are not exact replicas. In one case, our focus is brought in on Stuart’s torso curled in Shona’s lap. In this portrayal of Michelangelo’s Pieta sculpture, the pose in the detailed smaller painting differs slightly from the full scene: Stuart’s hand cups Shona’s breast in one but lies slack in the other. The postural variations lend an episodic effect, underscoring the fits and starts of artmaking. The imperfect repetition also mirrors our own organic glitchiness and how we are constantly recasting ourselves.

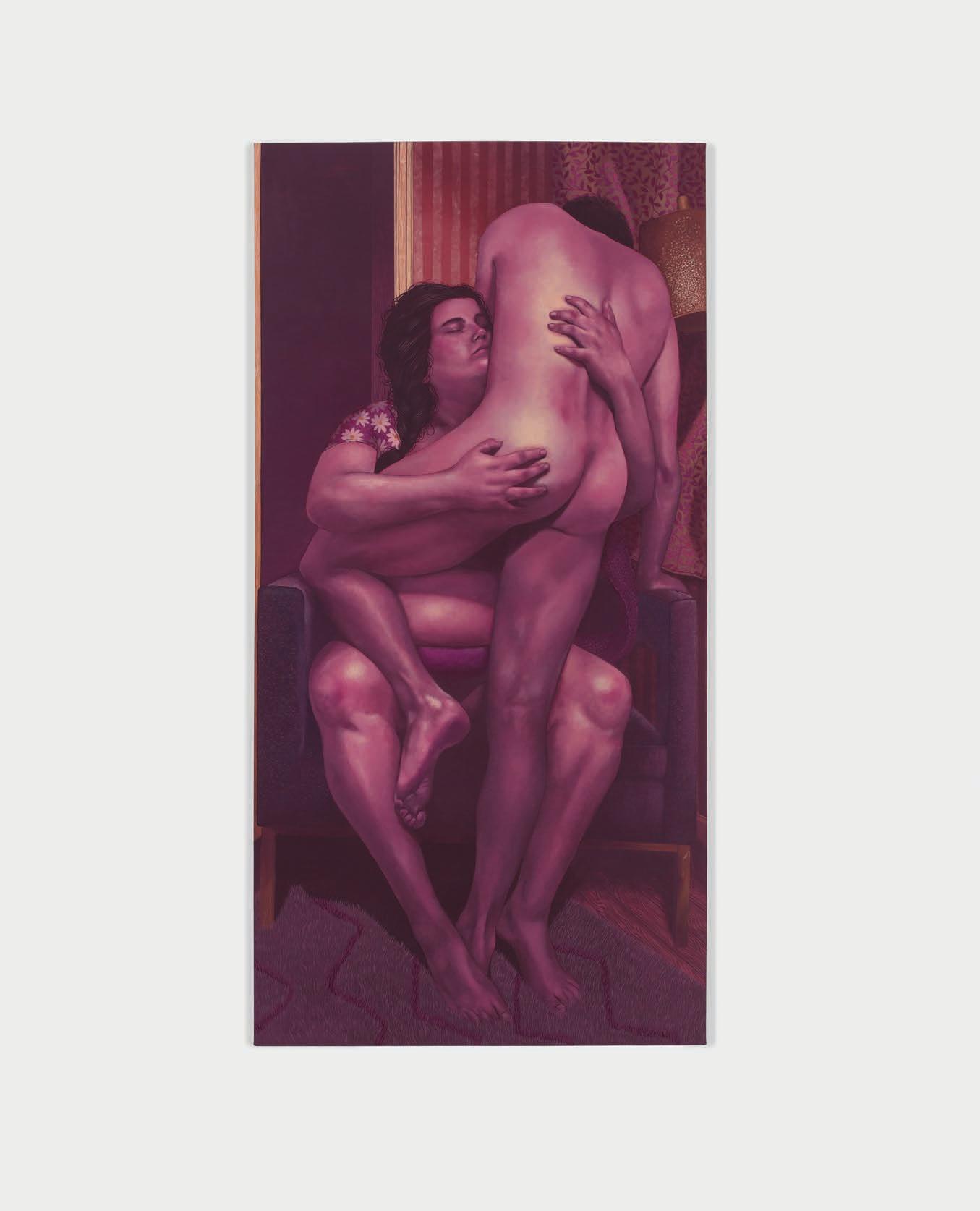

Storytelling is interpretive across this body of works, and gender roles don’t easily congeal. The palette’s dusky pinks unify the figures with low accents of light. Bernini’s Baroque sculpture

The Rape of Proserpina gets an affecting spin: Proserpina (Stuart) stands naked before Pluto (Shona, seated in an armchair), facing her as she embraces him. He seems to half-climb through her arms, on top of her, over her. She holds him firmly, lovingly, with her eyes closed. No violence or lack of consent. Being held is what’s happening.

“I like theatrics but I don’t like action,” Shona said. What is celebrated is calm tenderness, even in a scene modeled after Judith Beheading Holofernes.

The murderous fable (many versions of which have been painted) has achieved a kind of notoriety as a signifier for feminist rage—Judith is the emblematic poster girl who’s going to get the job done. Shona, however, renders the cathartic moment instead as one of solicitude, showing herself and Stuart on a comfortable sofa. A red beaded bracelet on her wrist vaguely hints at the blood spilling decapitation in the Biblical story, while Stuart’s hand on her hand on his neck conveys sweetness. The contact is soft. She gazes down at him. He gazes at the viewer. Resting one’s head in someone’s lap is an articulation of trust, and a rare pleasure. It’s the epitome of being told that everything is going to be okay. There’s no conflict here. You can relax.

When British artist Rolinda Sharples painted

The Artist and Her Mother in 1815, depicting herself at the easel with her mother alongside peering at the canvas, she was showing a bigger picture of what happens when a woman is supported to make art. In that scene, the walls in the background are amply hung with framed paintings, while the work in progress shows a young and elderly woman in a landscape. The full atelier indicates that the artist is prolific, and Sharples did in fact enjoy a career as a painter—a rare privilege. Her mother Ellen and her father James were both artists who made their living doing portraiture, and they saw it fit to encourage Rolinda’s skill. Ellen taught her daughter to draw and the family formed a traveling band of portraitists, living semi-itinerantly as they earned commissions. In the case of Rolinda Sharples, pursuing portraiture with familial support meant that an uphill battle of being a “lady artist” was transformed into a crafty enterprise. If anyone could intervene and lend a guiding light, thus sparing her daughter from sequestered and inert wifedom, it was her lively artist mother who also helped establish an art academy that offered life-drawing classes for women.

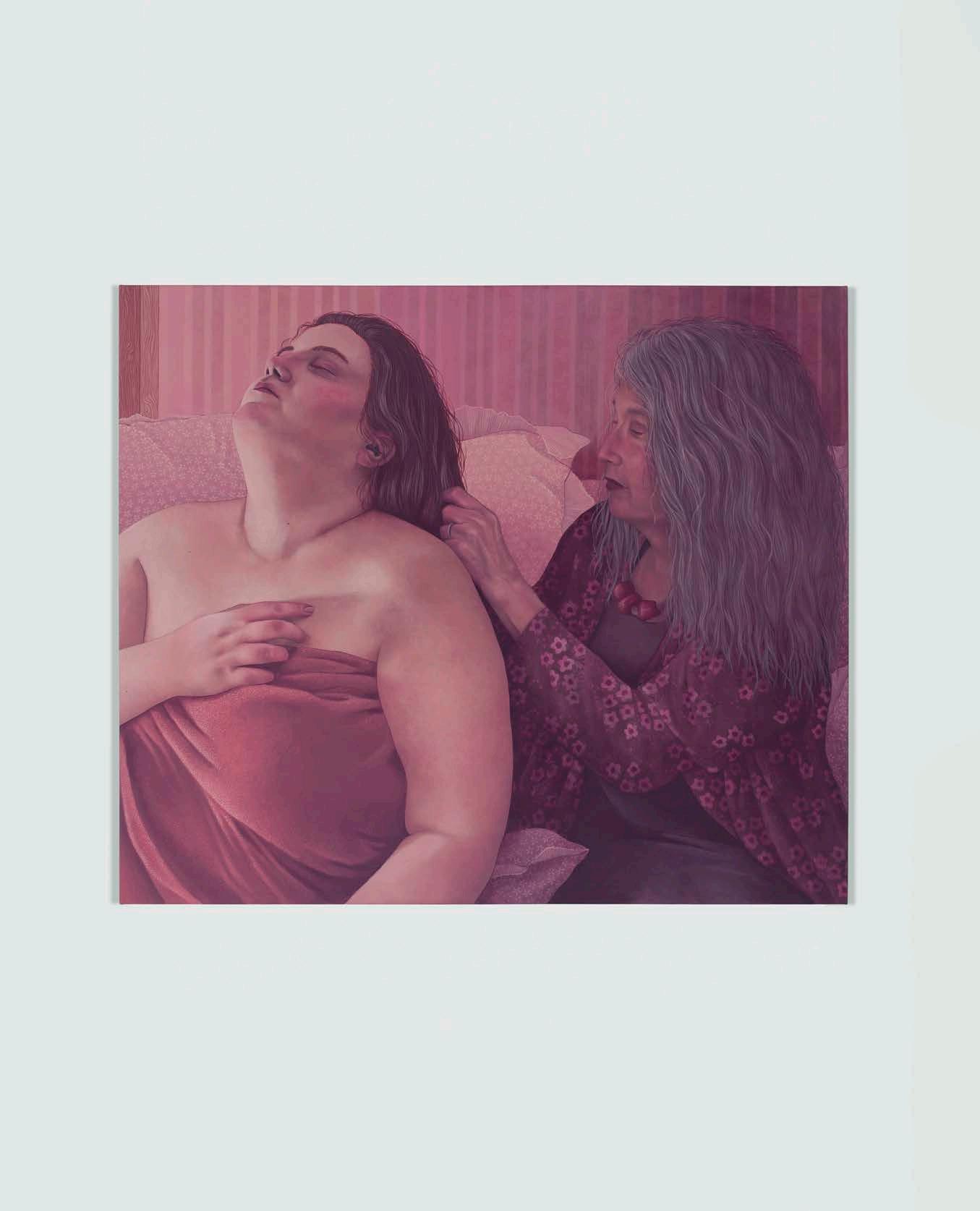

Much is debated and written about becoming a mother these days, but for many adults our own aging mothers still tend to fade out of the picture or become tropes discussed in therapy. According to Shona, when her mother Moira visited her studio while these new works were underway, she was “incredibly moved” by the bathing woman sculpture and “spent the whole time papier-mâchéing” the form. They posed together for a photo that

would be used to create Shona’s take on Artemisia Gentileschi’s Mary Magdalene in Ecstasy, with Moira combing Shona’s hair. The scene is connected to Shona’s childhood memory of sitting in front of her mother to have her hair brushed—an arduous activity that can be both physically uncomfortable and reassuring for a child. In Shona’s painting is the grace of accepting care. Mary of Magdala is commonly portrayed as the penitent woman of sin, whose long hair she uses to dry her tears and clean the feet of Christ the Redeemer. Some accounts describe her as being nude, her body covered with her long tresses. The pervasive Western notion that she was a prostitute likely says more about scripture’s shady editors than it does about the actual woman, who might have been an apostle (if she was even a real person).

Artemisia Gentileschi’s elusive Mary Magdalene in Ecstasy had a brief emergence in the spotlight when it was located in a private collection in France, subsequently put up for auction in 2014, and whisked away to another private collection. Gentileschi’s Mary Magdalene (or is it the artist herself?) is seen close-up, half-reclining in a loose blouse, her hands clasped over a knee, head tilted back and eyes closed with a serene light upon her face. There’s no stagey affect: no tears, no props, no alabaster vessel. Just appreciative quiet.

Artemisia Gentileschi, Mary Magdalene in Ecstasy, ca. 1613-20

Caravaggio, The Incredulity of Saint Thomas, 1603

Artemisia Gentileschi, Mary Magdalene in Ecstasy, ca. 1613-20

Caravaggio, The Incredulity of Saint Thomas, 1603

Shona paints herself and her mother in a similar tenor, reducing a much rewritten story to a compositional framework without the baggage of allegory—just as Artemisia Gentileschi did. Shona’s insertion of a matrilineal theme is a protective gesture that plays out across her new work.

The blind seer Tiresias in Ovid’s Metamorphoses issued a prophecy regarding the fate of young Narcissus: “This loveliest of nymphs gave birth at full term to a child whom, even then, one could fall in love with, called Narcissus. Being consulted as to whether the child would live a long life, to a ripe old age, the seer with prophetic vision replied ‘If he does not discover himself.’” Yet how in-depth does that self-discovery need be for it to become self-destructive? As it happens, a surface knowledge would suffice. Historically, the mirror is a fine line between annihilation and affirmation. This motif persists today, with the ubiquitous phone camera (also a mirror of sorts) rather complicating things. Perhaps ours is an epoch in which Narcissus-style self-sabotage is a legitimate peril for some, while others are all too guarded. It’s feast or famine in a time of visual extremes, and participation can be difficult to navigate. Shona says: “Before making this show I worried that it would be self-centered to make a show about myself. It’s not just just painting a body, it’s painting a large body. There’s this literal and figurative extra weight. I’ve been enjoying the process—it’s been hard at times, and draining, but very empowering.”

Shona leans over a running bath and gazes at her reflection in a painting inspired by Caravaggio’s The Myth of Narcissus. She offered an addendum to the ancient myth as it relates to her own quest to know (and admire) herself:

“I still think there’s a certain amount of power for women to be proud of themselves and in love with themselves. The hand touching my reflection is me touching me, me looking at me: as a bigger woman, it’s revolutionary. We’re asked to not

love ourselves—or to do what I did for ten years and not even look at myself in the mirror. I did what I was told to do. That’s the conversation I’m having.” Instead of Echo, Shona’s dog perches over the tub as the water fills. They both stare into the swirls; the artist’s right forefinger traces her reflection as if painting it, breaking the surface of the water into concentric ripples. She lies her head on the back of one hand which rests on her breast on the rim of the bath. The gridded tile wall anchors the contemplative scene.

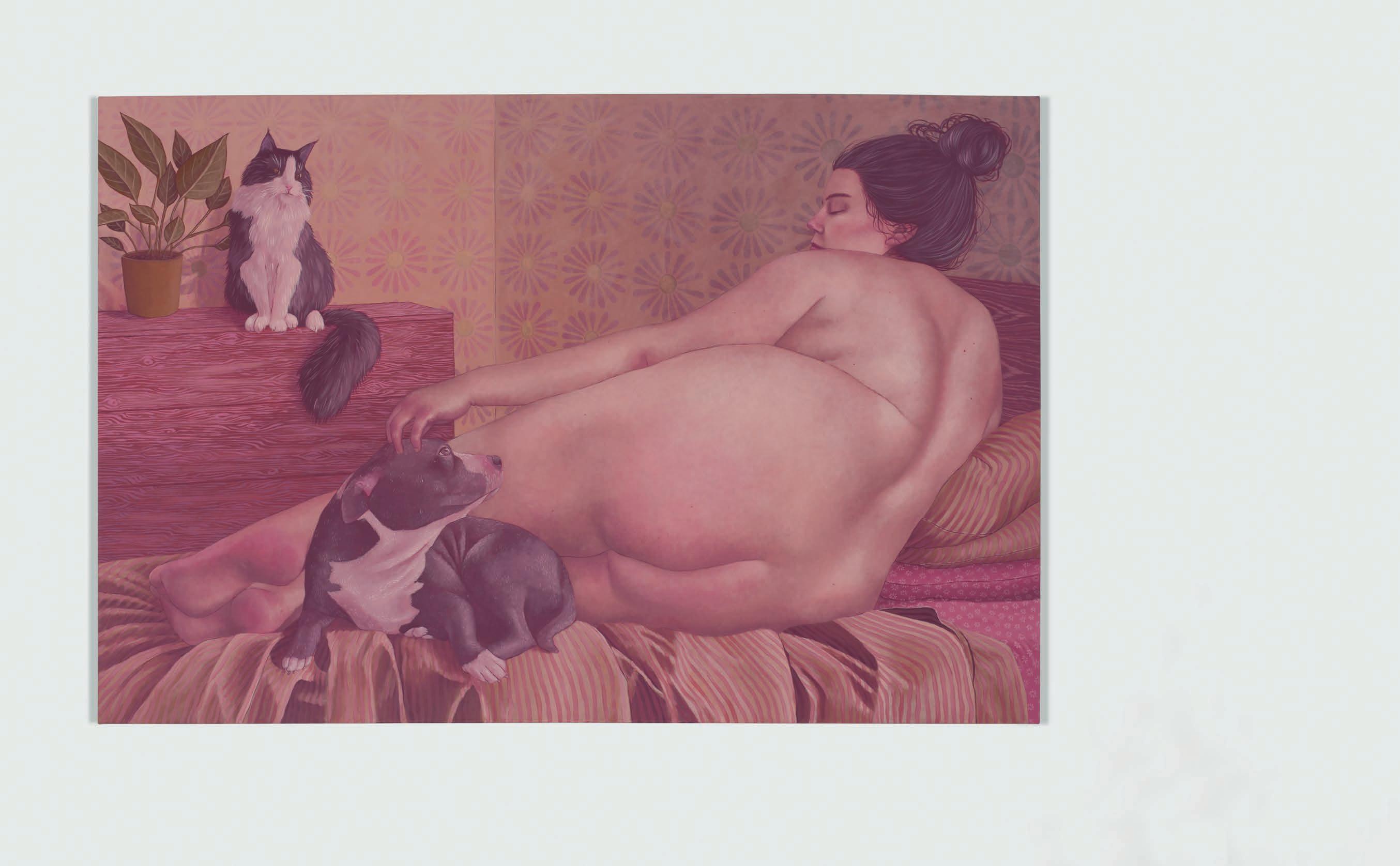

There’s an unassuming naturalism and lack of provocation in these works’ nudity. Breasts are neither the nutritive wellspring of motherhood nor carnal enticement. Shona’s parents were nudists when she was growing up in France, therefore nakedness is perhaps not as synonymous with sexuality as it is for some people. She expresses surprise at the idea of a viewer seeing sex in these paintings which are paeans to trust. The rise of selfies occurred during the period of time when Shona didn’t look at herself in the mirror, and by opting out maybe she preserved a degree of innocence—imagination intact. “I’m almost a foreigner to the concept of selfies,” she says. “We all want to be seen for all the good and wrong or right reasons. I try to bring in as much fantasy as I can, learning as I go.” When the artist assumes the pose of Venus at Her Mirror and paints her curves into the familiar staging of a disrobed goddess in repose, she includes her cat Bo and her cherubic dog Lily for good measure. Just like almost any allegorical painting, the parable itself is a feint and, in a sense, not the point. What Shona McAndrew’s work suggests is that all the roles have always been interchangeable and our lives are rife with opportunities for revision.

Charity Coleman is a writer and editor based in New York

Mollie

2022-2023, paper mâchée, acrylic, steel, foam, apoxy clay plywood, twine

Overall sculpture: 41 x 34.5 x 74 inches, 104.1 x 87.6 x 188 cm

My Mom and I

2023, acrylic on canvas, 56 x 62 inches, 142.2 x 157.5 cm

My Mom and I

2023, acrylic on canvas, 56 x 62 inches, 142.2 x 157.5 cm

Poke

2022, acrylic on canvas, 16 x 20 inches, 40.6 x 50.8 cm

Poke

2022, acrylic on canvas, 16 x 20 inches, 40.6 x 50.8 cm

Sunset at Home

2022, acrylic on canvas, 28 x 36 inches, 71.1 x 91.4 cm

Sunset at Home

2022, acrylic on canvas, 28 x 36 inches, 71.1 x 91.4 cm

Oh, To Be Loved

2023, acrylic on canvas, 66 x 56 inches, 167.6 x 142.2 cm

Oh, To Be Loved

2023, acrylic on canvas, 66 x 56 inches, 167.6 x 142.2 cm

The Embrace 2022 acrylic on canvas, 32 x 22 inches, 81.3 x 55.9 cm

Hold You 2022, acrylic on canvas, 34 x 38 inches, 86.4 x 96.5 cm

The Embrace 2022 acrylic on canvas, 32 x 22 inches, 81.3 x 55.9 cm

Hold You 2022, acrylic on canvas, 34 x 38 inches, 86.4 x 96.5 cm

Pieta 2022, acrylic on canvas, 62 x 56 inches, 157.5 x 142.2 cm

Pieta 2022, acrylic on canvas, 62 x 56 inches, 157.5 x 142.2 cm

Holding Tight

2022, acrylic on canvas, 36 x 26 inches, 91.4 x 66 cm

Holding Tight

2022, acrylic on canvas, 36 x 26 inches, 91.4 x 66 cm

Movie Night

2022, acrylic on canvas, 78 x 44 inches, 198.1 x 111.8 cm

The Embrace

2022, acrylic on canvas, 46 x 34 inches, 116.8 x 86.4 cm

The Embrace

2022, acrylic on canvas, 46 x 34 inches, 116.8 x 86.4 cm

Bedtime

2023, acrylic on canvas, 48 x 72 inches, 121.9 x 182.9 cm

Published

Shona McAndrew

February 23– April 1, 2023

Essay: Charity Coleman

Photography: Neighboring States

Design: works_for_art, frauke ebinger

Associate Designer: Kristen Wasik

Printing: Project

74 Franklin Street | New York, NY 10013 | 646. 799.9319 | chart-gallery.com