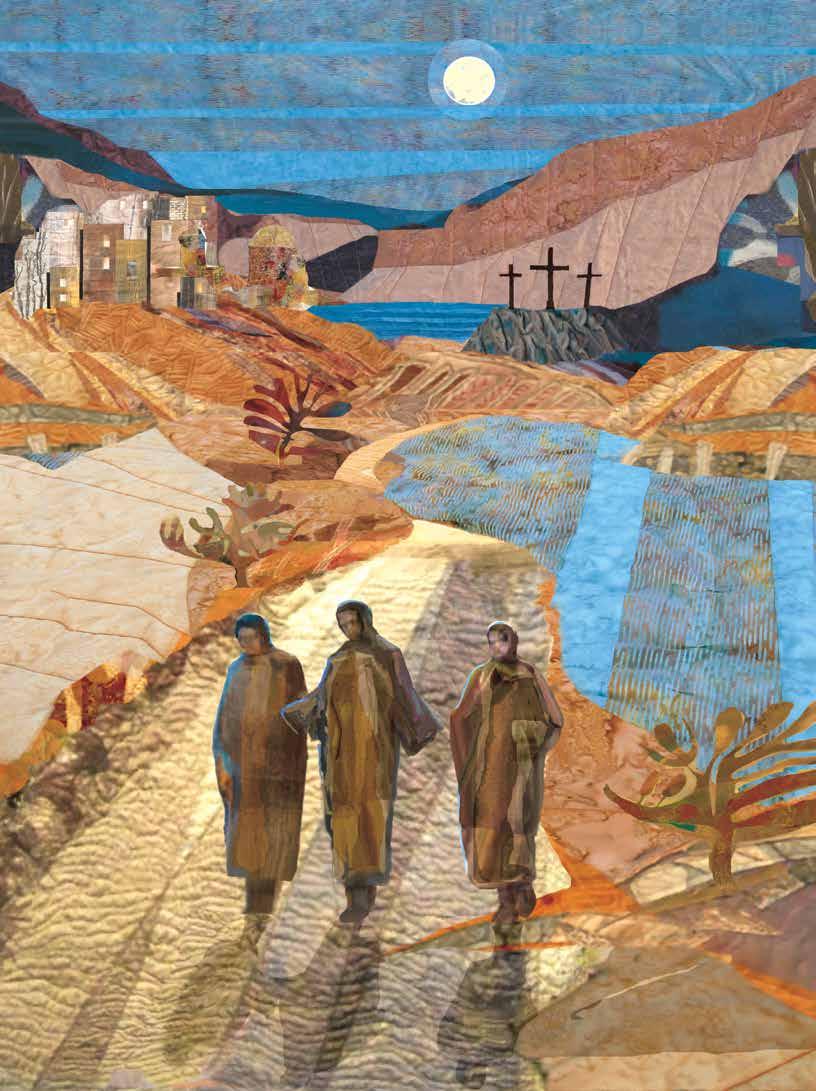

Illustrations by Nathan Hackett

4 TIPPING THE SCALE IN FAVOR OF CHILDREN’S HEALTH

Allen Sánchez

11 MODERN MEDICINE, TIME-HONORED PRACTICES: A PERSONAL AND PROFESSIONAL JOURNEY IN PEDIATRIC INTEGRATIVE MEDICINE

Anu French, MD, FAAP, ABoIM

18 HELPING TEENS TO NAVIGATE STRESS

Elena Mikalsen, PhD, ABPP

21 DEBUNKING ONLINE INFORMATION TO KEEP TEENS SAFE

Kelly Bilodeau

27 PREVENTING TEEN SUICIDE: TAKING MEASURES TO ENSURE AN ATTEMPT NEVER OCCURS

Cecelia Horan, PsyD, and Rick Germann, MA, LCPC

31 ADVOCATES FOR AT-RISK STUDENTS EASE THE TRANSITION BACK TO SCHOOL

Amy Onofre, PhD, LPC

36 FINDING THE RIGHT FIT: PROGRAMS FOSTER STUDENT INTEREST IN HEALTH CARE, DIVERSIFY FUTURE WORKFORCE

Robin Roenker

44 REFLECTION: BUILDING A PLAYBOOK FOR LIFE TO INSPIRE JOY, OVERCOME CHALLENGES

Sr. Lisa Maurer, OSB

48 PROGRAMMING TO PAIR YOUNGER AND OLDER GENERATIONS BRINGS MEANINGFUL CONNECTIONS

David Lewellen

53 AUTISM, NEURODIVERGENCE AND TRANSITIONING TO ADULTHOOD: THE NEED FOR SUPPORTED DECISION-MAKING AND SUPPORTED ENGAGEMENT

Nanette Elster, JD, MPH, and Kayhan Parsi, JD, PhD, HEC-C

2 EDITOR’S NOTE CHARLOTTE KELLEY

57 COMMUNITY BENEFIT Flourishing Children Benefit All of Us — For Generations To Come ALEXANDER GARZA, MD, MPH

60 FORMATION

Hope Is Not a Strategy. Or Is It? DARREN M. HENSON, PhD, STL

63 ETHICS

Stumbling Stones: History at Our Feet to Honor Humanity, Confront the Past BRIAN M. KANE, PhD

66 THINKING GLOBALLY

Opening Our Ears and Welcoming In Bold Change — Staying In by Leaning Out BRUCE COMPTON and HEATHER BUESSELER, MPH

69 MISSION

Why You Need a Chaplain on Your Personal Board of Directors JILL FISK, MATM

35 FINDING GOD IN DAILY LIFE

72 PRAYER SERVICE

IN YOUR NEXT ISSUE FAITH AND MEDICINE

As a child, whenever Christmas drew near, I looked forward to watching A Charlie Brown Christmas on TV. In the holiday special, Charlie Brown is feeling down despite the Christmas season and bemoans its commercialism.

To lift his spirits, Charlie goes with his friend Linus to look for a tree for the school’s Christmas play. However, the small tree he selects doesn’t go over well with the other kids, who are all looking forward to a great big, shiny aluminum tree.

“I’ll show them,” Charlie says, bringing the little tree home to fix it up into something grand. But his attempts fail, and his little tree sags to the ground from just one ornament. “Everything I touch gets ruined,” he says, and walks away.

But Linus approaches the sad tree, and says, “I never thought it was such a bad little tree. … Maybe it just needs a little love.” He then takes his blanket and lovingly wraps it around the bottom of the tree, perking the sapling right up. The other kids follow suit, decorate the tree and within seconds, a glorious, thriving tree takes shape.

And that’s all it took: just one person who believed in that little tree to start the chain to bring it fully to life.

In this issue of Health Progress, themed on Helping Youth Thrive, I encountered stories throughout Catholic health care and community partners about how just one mentor or advocate in a young person’s life, someone who believes in them and their potential, can help them flourish.

In her article about the Community Advocacy Project for Students in Lubbock, Texas, Amy Onofre, the program’s director, explains how the initiative pairs advocates with at-risk students at their schools to help kids set goals and navigate academic and life struggles, letting them know their voices matter. In another article, Sr. Lisa Maurer, OSB, director of mission integration and formation for Duluth Benedictine Ministries, who also

serves as an assistant football coach at the College of St. Scholastica in Minnesota, talks about the importance of having a value-laden playbook for life, especially when working with young people. Having one, she notes, can encourage youth to think about the values most important to them so they can confidently make decisions.

In another story about career training and job shadowing in Catholic health care for middle and high school students, we learn how experiencing just one day imagining themselves as health care professionals can transform a child’s dreams. When asked if he had known what a physician assistant was before spending a day with one particular program, a student answers, “No, but I’m going to do it.”

Also, thriving doesn’t stop when we get older, it only continues, as evidenced by writer David Lewellen’s article about intergenerational programs to pair younger and older people together. Whether by connecting generations through housing, art collaborations or in children’s classrooms, both younger and older participants gain social connection and meaning in their lives. “We give them power; they give us power,” says one older resident about the young children she encounters daily in her intergenerational living facility.

Even as I started planning this issue, Health Progress Editor Betsy Taylor began an academic leave to pursue professional development. Her endeavor is just another example of how we continue to flourish in all stages of life.

So, as some of you may start to see your own Christmas trees close in on their final days in the New Year, look around to see if there are any opportunities where you can help spark new life and hope. After all, providing love and a listening ear to those around us never goes out of season.

VICE PRESIDENT, COMMUNICATIONS AND MARKETING

BRIAN P. REARDON

EDITOR

BETSY TAYLOR btaylor@chausa.org

INTERIM EDITOR

CHARLOTTE KELLEY ckelley@chausa.org

GRAPHIC DESIGNER

NORMA KLINGSICK

ADVERTISING Contact: Yvonne Stroder, 4455 Woodson Rd., St. Louis, MO 63134-3797, 314-253-3447; fax 314-427-0029; email ads@chausa.org.

SUBSCRIPTIONS/CIRCULATION Address all subscription orders, inquiries, address changes, etc., to Service Center, 4455 Woodson Rd., St. Louis, MO 63134-3797; phone 800-230-7823; email servicecenter@chausa.org. Annual subscription rates are: complimentary for those who work for CHA members in the United States; $29 for nonmembers (domestic and foreign).

ARTICLES AND BACK ISSUES Health Progress articles are available in their entirety in PDF format on the internet at www.chausa.org. Photocopies may be ordered through Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Dr., Danvers, MA 01923. For back issues of the magazine, please contact the CHA Service Center at servicecenter@chausa.org or 800-230-7823.

REPRODUCTION No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from CHA. For information, please contact copyright@chausa.org.

OPINIONS expressed by authors published in Health Progress do not necessarily reflect those of CHA. CHA assumes no responsibility for opinions or statements expressed by contributors to Health Progress.

2024 AWARDS FOR 2023 COVERAGE

Catholic Press Awards: Magazine of the Year — Professional and Special Interest Magazine, First Place; Best Special Section, First Place; Best Special Issue, First Place; Best Coverage — Political Issues, First Place; Best Essay, First and Second Place; Best Feature Article, Third Place; Best Reporting on Social Justice Issues — Dignity and Rights of the Workers, Second Place; Best Reporting on Social Justice Issues — Life and Dignity of the Human Person, First Place; Best Reporting on Social Justice Issues — Option for the Poor and the Vulnerable, Third Place; Best Reporting on Social Justice Issues — Rights and Responsibilities, Third Place; Best Writing — In-Depth, Honorable Mention.

American Society of Business Publication Editors Awards: All Content — Enterprise News Story, Regional Gold Award; All Content — Government Coverage, Regional Silver Award; All Content — Editor’s Letter, Regional Silver Award.

Produced in USA. Health Progress ISSN 0882-1577. Winter 2025 (Vol. 106, No. 1).

Copyright © by The Catholic Health Association of the United States. Published quarterly by The Catholic Health Association of the United States, 4455 Woodson Road, St. Louis, MO 63134-3797. Periodicals postage paid at St. Louis, MO, and additional mailing offices. Subscription prices per year: CHA members, free; nonmembers, $29 (domestic and foreign); single copies, $10.

POSTMASTER: Send address changes to Health Progress, The Catholic Health Association of the United States, 4455 Woodson Road, St. Louis, MO 63134-3797.

Trevor Bonat, MA, MS, chief mission integration officer, Ascension Saint Agnes, Baltimore

Sr. Rosemary Donley, SC, PhD, APRN-BC, professor of nursing, Duquesne University, Pittsburgh

Fr. Joseph J. Driscoll, DMin, director of ministry formation and organizational spirituality, Redeemer Health, Meadowbrook, Pennsylvania

Tracy Neary, regional vice president, mission integration, St. Vincent Healthcare, Billings, Montana

Gabriela Robles, MBA, MAHCM, president, St. Joseph Fund, Providence St. Joseph Health, Irvine, California

Jennifer Stanley, MD, physician formation leader and regional medical director, Ascension St. Vincent, North Vernon, Indiana

Rachelle Reyes Wenger, MPA, system vice president, public policy and advocacy engagement, CommonSpirit Health, Los Angeles

Nathan Ziegler, PhD, system vice president, diversity, leadership and performance excellence, CommonSpirit Health, Chicago

ADVOCACY AND PUBLIC POLICY: Lisa Smith, MPA; Kathy Curran, JD; Clay O’Dell, PhD; Paulo G. Pontemayor, MPH; Lucas Swanepoel, JD

COMMUNITY BENEFIT: Nancy Lim, RN, MPH

CONTINUUM OF CARE AND AGING SERVICES: Indu Spugnardi

ETHICS: Nathaniel Blanton Hibner, PhD; Brian Kane, PhD

FINANCE: Loren Chandler, CPA, MBA, FACHE

GLOBAL HEALTH: Bruce Compton

LEADERSHIP AND MINISTRY DEVELOPMENT: Diarmuid Rooney, MSPsych, MTS, DSocAdmin

LEGAL, GOVERNANCE AND COMPLIANCE: Catherine A. Hurley, JD

MINISTRY FORMATION: Darren Henson, PhD, STL

MISSION INTEGRATION: Dennis Gonzales, PhD; Jill Fisk, MATM

PRAYERS: Karla Keppel, MA; Lori Ashmore-Ruppel

THEOLOGY AND SPONSORSHIP: Sr. Teresa Maya, PhD, CCVI

HELPING YOUTH THRIVE

ALLEN SÁNCHEZ President and Mission Leader, CommonSpirit St. Joseph’s Children

New Mexico: The Land of Enchantment, where you can find many opportunities for adventure but very few opportunities for our children. In 2010, the Annie E. Casey Foundation reported that the children of New Mexico ranked 46th in children’s wellbeing in the country,1 with 63% graduating high school and 80% of fourth graders falling below the proficient reading level.2 Three years later, in 2013, New Mexico would fall even further, ranking 50th in the nation for children’s well-being.3 Horrific, high-profile deaths of children at the hands of their parents and caregivers made headlines in the local and national media.

New Mexico is one of the largest oil producers in the nation, holding the rights to the majority of this liquid gold. At the time, this ranking, of a state holding the third-largest sovereign wealth fund in the nation4 (which today ranks as the secondlargest), was not just a sign of inequity but of a contrast for a dismal future for the well-being of the children of New Mexico. The state neglected to make the human capital investment necessary to uplift its children.

Yet, in the state’s coffers, what is known as the Land Grant Permanent Fund, which benefits from the state’s gas and oil revenues, was bulging. The situation could be best described by an image of a scale, with one side of it representing gas and oil royalty revenue pouring into the third-largest sovereign wealth fund in the nation and, on the opposite side of the scale, the worst outcomes for children, with the state ranking 50th in the nation in health and well-being. The fulcrum of the scale had to be moved to tip in favor of the children.

It was obvious that for years, the state’s policymakers had neglected to invest in its residents’ social capital. Through close examination during a strategic planning process — which included CHI St. Joseph’s Children (now known as CommonSpirit St. Joseph’s Children), New Mexico Voices for Children, Partnership for Community Action and others — many of the answers to preventing negative health outcomes pointed to an early mitigator: early childhood education and care programs.

To help policymakers comprehend how dire the situation was, CHI St. Joseph’s Children in Albuquerque, New Mexico, used the image of a potter spinning clay to form a vessel. It is like a child in the last trimester of pregnancy and through the age of 3, when approximately 1 million neural connections per second are being created, building the architecture of the brain.5 As

that beautiful, wet clay is being formed, like the brain, the adrenaline of toxic stress and adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) can poke holes in it, slowing down or even diminishing the development of the brain’s synapses. When the state then takes the largest investment it makes, K-12 education, and tries to pour it into the vessel, the pot cannot hold the liquid. The child arrives at kindergarten already behind — and stays behind — and we wonder why the child is unable to take full advantage of the educational opportunities.

CHI St. Joseph’s Children led its advocacy effort by example, creating one of the largest home visiting programs in the nation. This was funded by an endowment created from the divestiture of St. Joseph’s Hospital in Albuquerque by Catholic Health Initiatives, resulting in the community health organization known as CHI St. Joseph’s Children in 2000. We knew that home visiting develops the relationships that are the mitigators of toxic stress, trauma and ACEs that, years later, manifest themselves into poor health

outcomes.

With the support of case managers, trained home visitors go into the homes of first-time parents once a week for three years with a curriculum of health, well-being and school readiness. The case managers, who we refer to as Enhanced Referral Navigators, connect the families to all the safety net services for which they’re eligible. The program is open to any first-time parents in New Mexico and is offered at no cost to the participants. It was this example of leadership that gave legislators and policymakers a vision that they could embrace.

As an anchor organization in the community, CHI St. Joseph’s Children took on the banner to advocate for full funding of early childhood programs, which would create systemic change and bring health and well-being to the current and future generations of the state. In 2010, the organization Invest in Kids NOW began and had a membership of more than 40 nonprofits — including Partnership for Community Action, New Mexico

Voices for Children, Youth Development, Inc., and Lutheran Advocacy Ministry-New Mexico — to bring the fight to the state legislature to support such programs.

Everything was on the table, including raising taxes or the reappropriation of funds. There was no political will for a tax; what became an obvious source was the state’s Land Grant Permanent Fund. This was going to require a change in the distribution formula of the fund, created in 1910 by the Enabling Act, the law required for later creating the state of New Mexico in 1912. The Enabling Act stated that it would require a constitutional amendment, approved by the voters, to redirect money to the youngest residents of the state. This meant having to pass through the state legislature a resolution to place the question on the ballot for voters and would require a 2/3 majority vote of the elected bodies of the New Mexico State House of Representatives and the Senate.

Although polling indicated that 72% of registered voters in New Mexico were in favor of placing this resolution on the ballot,6 what seemed to be a logical solution turned into a 10-year battle with the state Senate. Entrenched senators of the powerful Senate Finance Committee had deemed the Land Grant Permanent Fund a sacred idol that could not be touched. Many elusive influencers of the state, protecting special interests such as the stock market and oil companies, seemed to sway that small group of powerful senators away from overhauling the long-needed distribution formula.

What made the yearslong battle an even greater indignity was that the oil money was flowing from lands seized from Native peoples by the federal government; the very lands creating the wealth were not benefiting the poorest populations from whom that land was taken.

This was a battle to create health and wellbeing for the population of the state, 7 one that

included a direct confrontation with the status quo of institutional racism. The ugly arm of institutional racism reached all the way back to the U.S. Congress, in its creation of the Land Grant Permanent Fund, by placing a requirement on New Mexico and Arizona as the only states in the country that must return to Congress for ratification for any changes to be made in their constitution dealing with state lands.

Invest in Kids NOW sounded the alarm on the plight of the children of New Mexico. Their campaign created an annual rally called the 1,000 Kid March to raise awareness in support of boosting early childhood education programs through the fund; its inaugural march was held in 2014. Each year that the event occurred, the state capitol, known as the Roundhouse, would be brimming with parents pushing strollers, leading toddlers by the hand and marching around the iconic capitol.

Parents faced legislators who were armed with misinformation, denying the scientific evidence of the benefits of early childhood education and planting fears that the state’s sovereign wealth fund, which at the time was over $15 billion and is now more than $30 billion,8 could not stand the additional withdrawal. The arguments by the fiscal hawks became a debate of what was the reasonable percentage to be withdrawn from a trust fund. Advocates turned this question on its head and returned with an additional question: What was the reasonable number of children to be left behind?

To elevate the detrimental effects that ACEs were having on the children of the state, CHI St. Joseph’s Children implemented a campaign in 2016 that parodied the state’s popular and successful tourism media campaign known as New Mexico True. This parody was known as New Mexico Truth9 — not just to tell the natural wonders of the state but to expose the statistics that showed the detrimental social conditions in which its children were living. The campaign didn’t ask

The campaign didn’t ask readers and viewers to take any specific action. Rather, it served as an educational campaign, like good prophets, first calling on the community to acknowledge and grieve for the injustices that had placed its children in peril.

readers and viewers to take any specific action. Rather, it served as an educational campaign, like good prophets, first calling on the community to acknowledge and grieve for the injustices that had placed its children in peril.

The Land of Enchantment was being challenged to see itself in the light of decades of institutional racism. The campaign featured such messages as, “New Mexico and its glowing hot air balloons rising to new heights where you can find the highest rate of children living in poverty in the United States.” Others included, “New Mexico, with its magnificent vistas and its unique cuisine, where our people turn a blind eye to its hungry

Powerful senators not in favor of the campaign’s mission influenced the media to editorialize their opposition through op-eds and Sunday cartoons depicting early childhood advocates as robbers and thieves. They went as far as declaring the 1,000 Kid March the Pre-K Gang, ready to hold up the Wells Fargo stagecoach carrying the chest of the Land Grant Permanent Fund with a cartoon of one man stating to another, “Keep yer eyes peeled! I hear the Pre-K Gang hangs out in these parts!”10

By being the first state in the union to make early childhood services a constitutional right, the health of New Mexico’s population will be forever changed.

children who rank second highest in the nation for children experiencing hunger.”

But the truth set the state free, and, with the public educated about the statistical conditions of the children of New Mexico, the logjam was broken. After 10 years of battling with the state legislature, the constitutional amendment, known as the House Joint Resolution 1 Early Childhood Constitutional Amendment,

placed on the November 2022

ballot and was approved by the voters with a mandate vote of 70.33% in favor.11

The ballot initiative authorized an additional withdrawal of 1.25% of the Land Grant Permanent Fund, but the ugly head of institutional racism planted more than a century earlier, still required ratification by the U.S. Congress. In the final hours of the congressional session ending on December 31, 2022, with the help of Sen. Martin Heinrich, D-New Mexico, and Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, D-New York, the ratification was placed in the omnibus budget package, approved and sent to President Joe Biden’s desk for his signature.

In the process of this battle, additional distribution was approved, and, in a political sidestep to try and derail the Land Grant Permanent Fund distribution, a separate Early Childhood Trust Fund was created in 2020, also receiving oil money from the oil severance tax. In addition, a new department known as the Early Childhood Education and Care Department, with a cabinet secretary overseeing its activities, became the deliverer of early childhood services. On July 1, 2023, the funds began to flow. Today, the department’s budget for delivering early childhood services is nearly $800 million in a state with a population of approximately 2 million people.12

In the process of this work, the Early Childhood Advisory Council was created to advise the newly appointed secretary, and, with the exposure of institutional racism, a state Council for Racial Justice was convened in 2020. This council works at the governor’s will to illuminate racism from state institutions.

By being the first state in the union to make early childhood services a constitutional right, the health of New Mexico’s population will be forever changed. The immediate impact on children’s health is evident: The first-of-its-kind universal child care in the nation places children in a safe environment, lifts their parents up by creating the ability to seek employment and raises the family out of poverty.13 In many cases, that employment brings health insurance coverage to the family. Universal Pre-K ensures that children reach kindergarten ready to learn, and home visiting connects parents to safety net service organizations, reassuring them that babies do come with instructions.

Home visitors, as part of CommonSpirit St. Joseph’s Children’s Joyful Parenting Partnership program, connect families and babies to a medical home and teach parents resilience and how to advocate for their child. They also bring access and connection to housing assistance, vaccinations, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program and other food services. Furthermore, they build relationships in which parents feel safe to self-disclose their need for referral and follow through to address issues such as postpartum depression or alcohol or substance abuse. In fact, the state can attest to a decrease in visits to the emergency room in the first year of a child’s life.14 New Mexico is blessed to have a revenue stream from royalties on gas and oil, but all states can discern how they, too, can make this constitutional right for their youngest children and invest it in the fundamental foundation for their lifelong health. Prioritizing health is a battle worth fighting.

ALLEN SÁNCHEZ is president and mission leader of CommonSpirit St. Joseph’s Children in Albuquerque, New Mexico. He is also executive director of the New Mexico Conference of Catholic Bishops and a member of the New Mexico State Investment Council, which manages the nation’s current second-largest sovereign wealth fund.

1. “The Annie E. Casey Foundation 2010 Kids Count Data Book,” Annie E. Casey Foundation, 2010, https://assets.aecf.org/m/resourcedoc/AECF2010KIDSCOUNTDataBook-2010.pdf.

2. “Common Core of Data: America’s Public Schools,” National Center for Education Statistics, January 2015, https://nces.ed.gov/ccd/tables/acgr_2010-11_to_ 2012-13.asp; “Early Warning! Why Reading by the End of Third Grade Matters,” Annie E. Casey Foundation, 2010, https://assets.aecf.org/m/resourcedoc/AECF-Early_ Warning_Full_Report-2010.pdf.

3. “2013 Kids Count Data Book: State Trends in Child Well-Being,” Annie E. Casey Foundation, 2013, https://assets.aecf.org/m/resourcedoc/AECF2013KIDSCOUNTDataBook-2013.pdf.

4. The New Mexico State Investment Council is a sovereign wealth fund that manages the investments for New Mexico’s four permanent funds: the Land Grant Permanent Fund, the Severance Tax Permanent Fund, the Tobacco Settlement Permanent Fund and the Water Trust Fund. Tiziana Barghini, “Largest Sovereign Wealth

Funds (SWFs) 2015,” Global Finance, November 1, 2014, https://gfmag.com/features/largest-sovereignwealth-funds/.

5. “Why 0-3?,” Zero to Three, https://www.zerotothree. org/why-0-3/.

6. “2021 New Mexico Early Childhood Statewide Survey,” CHI St. Joseph’s Children, January 11, 2021, https://stjosephnm.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/ New-Mexico-Early-Childhood-Statewide-SurveyPresentation.pdf.

7. “New Mexico Could Not Hear the Train,” Century Lives, November 1, 2023, https://open.spotify.com/ episode/6eSsNu3xlWfxWcdjo2YGfa.

8. “Permanent Fund Investments to Surpass Oil and Gas Revenue, Securing New Mexico’s Future by 2039,” New Mexico Department of Finance and Administration, https://www.nmdfa.state. nm.us/2024/09/17/permanent-fund-investments-tosurpass-oil-and-gas-revenue-securing-new-mexicosfuture-by-2038/.

9. New Mexico Truth, https://newmexicotruth.org.

10. Andrew Oxford, “Kids March on Capitol for Early Education Funds,” Santa Fe New Mexican, January 2018, https://www.santafenewmexican.com/news/

education/kids-march-on-capitol-for-earlyeducation-funds/article_adca512e-024b-596f-8322ed67b37bc0b7.html.

11. Phill Casaus, “Sánchez’s Persistence Helps Turn a Pipe Dream Into Early Education Milestone,” CommonSpirit St. Joseph’s Children, November 12, 2022, https://stjosephnm.org/2024/05/24/sanchezspersistence-helps-turn-a-pipe-dream-into-earlyeducation-milestone/.

12. Susan Dunlap, “ECECD Expects Slightly Smaller Budget than Requested,” New Mexico Political Report, March 2, 2024, https://nmpoliticalreport.com/ nmleg/ececd-expects-slightly-smaller-budget-thanrequested/.

13. “With Costs of Child Cares Soaring, New Mexico Finds a Way to Make It Free for Many,” NBC Nightly News, October 29, 2024, https://www.nbcnews. com/nightly-news/video/with-costs-of-child-caressoaring-new-mexico-finds-a-way-to-make-it-free-formany-223008837777.

14. “New Parent Home Visiting Program Reduces Infants’ Need for Medical Care During First Year of Life,” RAND, December 15, 2016, https://www.rand.org/news/ press/2016/12/15.html.

Health Progress’ Diversity, Equity and Inclusion

Discussion Guide supports learning and dialogue to move toward a greater understanding of patients, care providers and ways to work together for improved diversity, equity and inclusion in Catholic health care settings.

GUIDE INCLUDES

Introduction on how to use the materials.

Health Progress articles for reflection, discussion and as a call to action.

Opening and closing prayer from CHA’s resources.

OR SCAN THE QR CODE

HELPING YOUTH THRIVE

ANU FRENCH, MD, FAAP, ABoIM SSM Health Cardinal Glennon Pediatrics and Integrative Medicine

As I approach 30 years in clinical practice, walking into our SSM Health Cardinal Glennon Pediatrics and Integrative Medicine office at SSM Health DePaul Hospital in St. Louis reminds me of the poem I wrote as my mission statement when I was only dreaming of such a possibility.

Holy Encounter:

As I step over the threshold, I ask to be blessed with kind usefulness each day.

As I wash my hands, I ask to be mindful and motivational each day.

As I brew my morning tea, I ask to be humble and receptive each day.

As I take the history, I ask to listen keenly to the story each day.

As I recognize the honor, I ask for the courage to be connected each day.

As I feel the healing, I ask for the clarity to see the wholeness in each day.

As I tend the mind-body-spirit, I ask for surrender to the sanctity of each day.

As I nourish and flourish, I offer deep gratitude for the privilege of each day.

My presence: holy moment. My journey: holy labyrinth.

My office: holy space. My patient: holy encounter.

Sometimes, I pinch myself because 15 years ago, I was in such a different space. I was professionally and personally burned out, disinterested in the revolving sickness door of primary care pediatrics, and exhausted from the merry-

go-round of home and work. I had just attended a weekend gathering of integrative healers committed to improving health care for children. In the therapeutic journaling session, we were asked to write about something that had changed who we were professionally and personally. As the room fell silent, I realized that the time had come for me to acknowledge that I was burned out.

AN INTEGRATED PATH TO HEALING

I had lived most of my adult life with chronic disease that had taken its toll on me. It was becoming apparent to me that I was not an effective resource unless I was truly committed to being on the journey to healing myself. Creating tools to build intergenerational resilience in myself, my children, my patients and their caregivers had to become a priority.

In 2011, I answered an email about a fellowship on integrative medicine at the Andrew Weil Center for Integrative Medicine at the University of Arizona. I took a leap of faith and completed the training and board certification in this fledgling specialty.1 It was a healing-oriented medicine that looked at the whole person/child, teaching appropriate use of both conventional and evidence-

informed complementary remedies. I learned about self-care and started to nourish myself and my family through music and art.

The graphic shown below from The National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health of the National Institutes of Health, which researches the use and safety of complementary health approaches, shows how these remedies can be integrated into a whole-person health framework.2

Dr. Kathi Kemper, a respected pioneer in this specialty and professor of pediatrics at The Ohio State University College of Medicine, defines pediatric integrative medicine (PIM) as caring for the whole child in the context of their values, their family’s beliefs, their family system and their culture in the larger community. The specialty also considers a range of therapies based on the evidence of their benefits and costs, which aligns with SSM Health’s mission and values.

In 2015, Dr. Kemper invited me to be part of the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Section on Integrative Medicine PIM Leadership Summit. The white paper we wrote included compelling data that showed complementary therapies are of great interest to parents and that the use of these therapies in pediatrics is significant. The National Health Interview Survey, conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Health Statistics in 2012, revealed that 12% of children use complementary therapies chosen by their families, and studies in specific

chronically ill populations have reported complementary therapy use in up to 80%. 3 More than 1,500 parents solicited through a survey answered questions regarding integrative therapies they’d like to see offered in a pediatric practice and their willingness to advocate for insurance coverage of PIM therapies.

In 2019, with the support of leadership at SSM Health Cardinal Glennon Children’s Hospital, the PIM office came into being after five years of planning. And, in the last five years, we have had the privilege of being on healing journeys with many courageous families that have children with medically complex illnesses, which has renewed my zest for medicine. Integrative medicine nudged me in a fresh direction and connected me with a vibrant community of healers and teachers, both globally and in my own backyard of St. Louis, who continue to show me how to bring mind-bodyspirit medicine into our office and into my home.

In her groundbreaking book The Deepest Well: Healing the Long-Term Effects of Childhood Adversity, Dr. Nadine Burke Harris, founder of the Center for Youth Wellness and former Surgeon General of California, writes: “Sleep, mental health, healthy relationships, exercise, nutrition and mindfulness — we saw in our patients that these six things were critical for healing [of adverse childhood experiences]. ... Fundamentally, they all targeted the underlying biological mechanism

Source: The National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health

Integrative medicine nudged me in a fresh direction and connected me with a vibrant community of healers and teachers, both globally and in my own backyard of St. Louis, who continue to show me how to bring mind-bodyspirit medicine into our office and into my home.

— a dysregulated stress-response system and the neurologic, endocrine and immune disruptions that ensued.”4 Integrative medicine is dedicated to looking at the whole person and using the latest science to improve health and well-being.

When 6-year-old Maya, whose name has been changed for privacy, and her family arrived at our office, they had seen multiple health care practitioners. They were tired, scared, frustrated and looking for answers. As a trauma-informed office, our first goal is always to make sure that we are creating a safe space where the child and family feel seen, heard and affirmed.5

The importance of providing this level of care and attention is especially true for a neurodivergent child such as Maya, who is on the autism spectrum with behavioral, sleep and focus concerns. As family physician and psychiatrist Dr. Lewis Mehl-Madrona says in his beautiful book, Narrative Medicine: The Use of History and Story in the Healing Process, “We need to develop an approach that will allow the patient and his or her family to be active collaborators in the healing process.”6 So, our next goal was to come up with a therapeutic plan — one that was culturally competent, economically affordable and guided by the family — which included all of pediatric integrative medicine’s pillars of health (shown in the graphic on page 15).

Building intergenerational resilience is one of the priorities of PIM, and luckily for us, Maya loved music, art and mindful movement. Research on yoga is expanding at the National Institutes of Health, which currently lists several studies on its benefits.7 In 2016, recognizing how important the holistic approach to shifting health care paradigms was, AAP’s Section on Integrative Medicine released a clinical policy statement on the use of mind-body therapies in children and youth.8 A review on the effectiveness of yoga as a comple-

mentary therapy for children and adolescents, which I was asked to co-author, was included in the statement.9 This inspired me to complete yoga teacher training for kids through the YoYo Yoga School in St Louis.

The practice of yoga has been shown to decrease stress via downregulation of the sympathetic nervous system, the fight or flight response. I enjoyed bringing some of these tools into our office for Maya’s treatment plan, including using our breath to hum and buzz like bees as we did our mindful yoga poses of a tree, a mountain and a butterfly.

The benefits of sound and music examined in a scoping review show a range of their effects on the neuro-immune-endocrine systems. 10 In ancient cultures, the use of sound for healing was a highly developed sacred science. In 2018, a pilot study conducted at our SSM Health Cardinal Glennon Pediatric Primary Care Clinic at SSM Health DePaul Hospital was funded and published through the AAP’s Section on Integrative Medicine, demonstrating calming brain wave patterns in 25 parent-child volunteers — including improved sleep — who listened to healing harp music. 11, 12 Music therapy became part of Maya’s bedtime routine, in addition to soothing guided imagery routines practiced with her parents.

Once we gained the trust of Maya and her parents, we moved on to discuss incorporating an anti-inflammatory diet into the family’s shopping and cooking schedule and adding highquality supplements and botanicals to support deficiencies we found in her lab work.13 In the integrative psychiatry fellowship I completed in 2020, we were taught about the emerging field of nutritional psychiatry, which uses nutrition to optimize brain health and treat and prevent mental health disorders.14 As noted in an EBioMedicine article, using food as medicine points to the “immune system, oxidative biology, brain plastic-

ity and the microbiome-gut-brain axis as key targets for nutritional interventions.”15

It is encouraging for me to see, as someone who has found her way back from it, that burnout prevention is being given priority. The Missouri Chapter of the AAP collaborated with the Missouri Child Psychiatry Access Project16 and the Missouri Department of Conservation to host a physician wellness retreat in September, where I spoke on the anti-inflammatory diet and how to incorporate it into our homes and offices.

The Care for the Caregiver program at SSM Health Cardinal Glennon Children’s Hospital, through the generosity of the SSM Health Cardinal Glennon Children’s Foundation, facilitates weekly sessions for all the hospital’s care team members that include meditation, breath work, yoga, pet therapy, art therapy, massage and more. I was grateful to be invited to share a virtual sound healing meditation at one of the sessions this past fall with my Tibetan bowls. The baby steps we suggest to our patients and their families for lifestyle modification become important steppingstones for our own healing journeys so that we can all find what brings pleasure and fulfillment in our lives.

Dr. Andrew Weil, a world-renowned leader

and pioneer in the field of integrative medicine, emphasizes that good medicine should be based on good science, be inquiry-driven and open to new paradigms where one should use natural, effective, less-invasive interventions whenever possible.17 Maya had been showing steady improvement in all her symptoms as we addressed her sleep, diet, relationships and physical environment. She was back in school and getting the full benefit of all her therapies while the burden of worry on her parents had lifted considerably. Our wonderful PIM team makes these success stories possible.

Dr. Weil also discusses how important it is to train the next generation of practitioners to be models of health and healing, committed to the process of self-exploration and self-development. The Academic Consortium for Integrative Medicine & Health includes more than 75 academic medical centers, nursing schools and health systems that advance integrative health care education, research and clinical care.18 The SSM Health Cardinal Glennon Children’s Foundation sponsored a grant in 2014 that supported our SSM Health Cardinal Glennon Pediatric Primary Care at SSM Health DePaul Hospital in offering an elective accredited by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education in integrative medicine for third-year Saint Louis University pediatric residents as part of the Pediatric Integrative Medicine in Residency pilot.19

When the Integrative Medicine for the Underserved policy committee went to Capitol Hill in 2018 to attend a bipartisan congressional caucus on integrative approaches to address the chronic pain epidemic, I went with them and saw firsthand how sharing information on rigorous scientific research and sustainable models of clinical care can inform current health care policy.20 I am honored to be a clinical mentor for pediatricians who are currently doing their fellowship training in integrative medicine at the Andrew Weil Center for Integrative Medicine and giving back to the program that started my own journey to better health.

As we enter the new year, it will be 25 years for me with the mission of SSM Health, and I look forward to the next five-year plan of expanding our integrative medicine services to continue to provide equitable, affordable, accessible and

Inspired by an “I Am Centered” artwork piece hanging in one of the exam rooms at SSM Health Cardinal Glennon Pediatrics and Integrative Medicine’s office in St. Louis (shown left), a 6-year-old patient created her own artistic interpretation of the piece and gifted it to integrative pediatrician Dr. Anu French (shown right). Art, music and mindful movement can play important parts in integrative medicine’s holistic approach to care.

holistic pediatric care to all children regardless of their social determinants of health. I continue to research how music, mindfulness and art can rebuild and rewire brains and hearts, and I look forward to going to work each day.

Many of us get defined by the diseases we are told that we have. I was labeled with so many, and I thought I would have to coexist with them for the rest of my life. Painting “I Am” affirmations became a joyful way to connect with my two beautiful daughters and my own inner child. The affirming art that I created to bring me back from the brink of burnout is now hanging in the waiting room and exam rooms of our SSM Health Cardinal Glennon PIM office.

Maya was inspired by my “I Am Centered” artwork hanging in one of our exam rooms and gifted me with her interpretation of it, which sits proudly on my desk at work. I have come full circle, helping children and families access their innate selfregulatory systems as I continue to learn how to access mine.

DR. ANU FRENCH is an integrative pediatrician with SSM Health Cardinal Glennon Pediatrics and Integrative Medicine in St. Louis and is also an artist, musician and author.

1. “Andrew Weil Center for Integrative Medicine,” The University of Arizona, https://awcim.arizona.edu.

2. “What Does NCCIH Do?,” National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health — National Institutes of Health, https://www.nccih.nih.gov.

3. Lindsey Black et al., “Use of Complementary Health Approaches Among Children Aged 4–17 Years in the United States: National Health Interview Survey, 2007–2012,” National Health Statistic Report 10, no. 78 (February 2015): 1-19; Anna Esparham et al., “Pediatric Integrative Medicine: Vision for the Future,” Children 5, no. 8 (August 2018): https://doi.org/10.3390/ children5080111.

4. Dr. Nadine Burke Harris, The Deepest Well: Healing the Long-Term Effects of Childhood Adversity (Mariner Books, 2018).

5. “Professional Tools and Resources for TraumaInformed Care,” American Academy of Pediatrics, https://www.aap.org/en/patient-care/ trauma-informed-care/professional-tools-resources.

6. Dr. Lewis Mehl-Madrona, Narrative Medicine: The Use of History and Story in the Healing Process (Bear & Company, 2007).

7. “Yoga: Effectiveness and Safety,” National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health — National Institutes of Health, August 2023, https://www.nccih. nih.gov/health/yoga-effectiveness-and-safety.

8. Section on Integrative Medicine, “Mind-Body Therapies in Children and Youth,” Pediatrics 138, No. 3 (2016): https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-1896.

9. Dr. Lawrence Rosen, Dr. Anu French, and Grace Sullivan, “Complementary, Holistic, and Integrative Medicine: Yoga,” Pediatrics in Review 36, No. 10 (2015): https://doi.org/10.1542/pir.36-10-468.

10. Genevieve A. Dingle et al., “How Do Music Activities Affect Health and Well-Being? A Scoping Review of Studies Examining Psychosocial Mechanisms,” Frontiers in Psychology 12 (September 8, 2021): https://doi. org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.713818.

11. Dr. Anu French and Kristy Shaughnessy, “Testing the Impact of the ‘The Magic Mirror’ Harp Music as a CostEffective Biofeedback/Neurofeedback Tool to Relieve Stress, Build Intergenerational Resilience and Teach SelfRegulation,” Pediatrics 144, No. 2 (August 2019): https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.144.2MA6.530.

12. “Pediatric Pilot Study: Presentation at the American Academy of Pediatrics National Conference,” Amy Camie: The Healing Harpist, https://www. amycamie.com/pediatricpilotstudy.html.

13. “Dr. Weil’s Anti-Inflammatory Diet,” Dr. Weil, https://www.drweil.com/diet-nutrition/ anti-inflammatory-diet-pyramid/dr-weilsanti-inflammatory-diet/.

14. Dr. Drew Ramsey, “What is Nutritional Psychiatry?,” Drew Ramsey, MD, July 7, 2022, https://drewramseymd .com/brain-food-nutrition/what-is-nutritionalpsychiatry/.

15. Felice N. Jacka, “Nutritional Psychiatry: Where to Next?,” EBioMedicine 17 (March 2017): http://dx.doi. org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2017.02.020.

16. “Missouri Child Psychiatry Access Project (MO-CPAP),” University of Missouri School of Medicine, https://medicine.missouri.edu/departments/ psychiatry/research/missouri-child-psychiatry -access-project.

17. “Meet Dr. Weil,” Dr. Weil, https://www.drweil.com/ health-wellness/balanced-living/meet-dr-weil/.

18. “Academic Consortium for Integrative Medicine & Health,” https://imconsortium.org.

19. “Integrative Medicine in Residency,” Andrew Weil Center for Integrative Medicine at the University of Arizona, https://awcim.arizona.edu/education/imr.html.

20. “IM4US: Integrative Medicine for the Underserved,” https://im4us.org.

Integrative medicine is dedicated to looking at the whole person and using the latest science to improve health and well-being. The discipline explores the role that music, mindfulness, art and other complementary therapies can play on the journey to healing and wellness.

1. How do you feel about adding complementary therapies to treatment plans for patients suffering from chronic or complex diseases? What complementary resources are available to your patients, or how could you encourage them and your colleagues to include these as part of a treatment plan?

2. In addition to explaining the benefits of integrative medicine for her patients, author Dr. Anu French shares in her article how it has helped on her personal healing journey and suggests that the discipline can be a tool in burnout prevention. Does your health system offer integrative medicine as part of its well-being program for staff? If so, how can you and your colleagues take advantage of this?

3. As a system administrator, how can you explore adding art, meditation or other integrative medicine tools into your well-being program for clinicians and staff?

4. As a faith-based health care ministry, what are some ways you can incorporate spirituality into an integrative approach to healing for your patients? How can you include a spiritual component in your organization’s well-being efforts for staff?

ELENA MIKALSEN, PhD, ABPP Chief, Division of Pediatric Psychology, CHRISTUS Children’s

Some parents may notice that their teens seem more stressed every school year. And they are correct. According to The American Institute of Stress, 27% of U.S. teens feel extreme stress during the school year, approximately 18% experience an anxiety disorder caused by stress, and almost 30% report feeling depressed.1

Parents of teens may remember feeling stressed when they were teens and expect their children to navigate the years successfully, as they did. Teens today still face the same normal developmental stressors, such as finding peer groups, navigating the highs and lows of team sports, and increasing academic pressure, according to experts. In addition, pediatricians and mental health practitioners are also concerned about the growing impact of unrestricted social media access, increasing academic pressures at school, climate change, gun violence and, finally, the still lingering effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on current teen mental health.

Prior to the pandemic, pediatricians and mental health professionals were already noticing increasing rates of stress and mental illness in adolescents. However, the pandemic caused a significant psychological impact on youth and families. A recent American Psychological Association survey on stress in America pointed out that our society continues to experience psychological impacts of stress and traumatic experiences in the aftermath of pandemic lockdowns, school closures and disruptions in family routines. 2 Additionally, families and experts are still seeing the aftereffects of social isolation and academic underachievement on teen stress levels.

Another new factor increasingly affecting teens is social media. Experts are warning parents that prolonged social media use is associated with low self-esteem, depression, anxiety, poor sleep, eating disorders and suicide risk. Teens who spend more than three hours on social media per day face double the risk of mental health difficulties, according to an advisory from the U.S. Surgeon General in 2023,3 but studies have emerged showing that teens spend on average 4.8 hours per day navigating different social media platforms.4

The risk of negative mental health consequences from social media overuse is particularly high for adolescent girls. Girls are prone to comparing themselves to peers and defining their identity via others’ opinions, making them more vulnerable to depression after repeated exposure to social media. Girls, ages 13-19, have been found to spend more than five hours per day on social media,5 which means they feel the pressure to be “clever, smart and popular” all day, first at school and then on social media. It also means teens are being judged and criticized all day long, exposing them to constant social pressure. A rumor spread on social media can reach thousands of people in a matter of seconds.

Daily stress is definitely part of life, and it is

important to teach children how to navigate it. Long-term stress, however, is a risk for a variety of mental health difficulties. Stress can also cause significant wear on the immune system and lead to poor physical health. While experiencing stress is not necessarily detrimental for teens, how they cope with it is important. From my observations, teens are more likely to report using passive coping strategies, such as taking a nap or listening to music. While these methods work, they often don’t allow for learning active coping strategies, which help embrace and navigate stress, rather than just distract from it.

The following are some active ways of coping that parents can easily discuss with and teach to their children.

Manage social media use. Ever-increasing social media use is worsening teens’ stress levels, mental health, social skills, sleep and academic performance. The U.S. Surgeon General’s recent advisory cautioned that social media use in adolescence interferes with learning self-control, emotional regulation, learning and social skills and recommends parents take steps to prevent negative and spiraling effects of social media on teen mental health and stress levels.6 The following are some strategies that parents can do:

1. Parents should not allow their teens to access social media until they are 16. If they do decide to let them use it, they should consider an Instagram Teen Account, which includes some safeguards and parental controls.

2. Parents can create boundaries around family social media use. Parents should not allow smartphones to be used during meals or family activities. They should also serve as a good example to their teens by putting their phones away when talking, listening and eating.

3. Parents can teach teens how to handle social comparisons forced on them by social media. They can discuss how influencers and algorithms can affect them and how social media posts don’t portray real-life experiences.

4. Parents can teach their children how social media is often used for cyberbullying. They can encourage them to block bullies and stay connected only to peers who are positive, fun and supportive. They should also report all cyberbullying and exploitation of their teen.

Engage in physical activity. Only 15% of teens get enough daily exercise.7 Exercise is one of the most effective stress and anxiety relievers. It can also work as well as antidepressants or cognitive-behavioral therapy to reduce symptoms of depression.8 Any of these activities are helpful: yoga, hiking, biking, walking, dancing, running, basketball, rock climbing and skateboarding. The best activity is one that involves a social component, but it doesn’t need to be a team sport.

Get enough sleep. The recommended amount of sleep for teens is eight to 10 hours, according to recommendations from the American Academy of Pediatrics.9 However, surveys find that most teens sleep, on average, less than eight hours per night.10 Lack of sleep is connected to increased levels of stress, anxiety, depression and decreased academic performance. Teens who don’t get enough sleep are four times as likely to develop depression as those who are well-rested.11

Resist academic pressure. Teens are pressured more than ever to make high-stakes choices, know exactly who they are, perform perfectly all the time and achieve more. There is competition, social judgment and pressure from parents, teachers and society. Parents can teach their teens that they don’t have to be perfect, don’t have to get it right at any age, and can always change their minds when they are older. What they do now academically will not determine their entire lives.

Parents should discuss the importance of sometimes saying no to academic pressure. Their teen does not need to take every AP class their school recommends and participate in every club, sport and leadership activity. I recommend no more than two organized after-school activities for teens to allow for more time socializing with peers and engaging in self-care activities.

Parents can encourage their teens to engage in social and fun activities, not just required school activities. They should also allow them enough time to participate in religious youth groups, craft and talent activities, camps and community events. It’s also important that they keep in mind that colleges look for happy and well-rounded students, not just students with good grades and a multitude of standard activities.

Engage in meditation and mindfulness. Mindfulness refers to paying attention to life in the

present, being fully aware of our surroundings and what we are doing, and being in the moment and enjoying it fully, rather than constantly being distracted by electronics, social media and text messages. When we don’t have the ability to be in the moment, anxiety grows, and we become too overwhelmed to solve problems.

Teens who are always distracted and worried about the future begin to struggle with chronic stress and anxiety. Parents can teach their teens to put away their phones at the dinner table and turn off the TV the next time their family is eating dinner. They can encourage them to focus on eating their food and enjoying its flavors. Or the next time their teen is watching a show, they can suggest they don’t chat about it on social media or text friends at the same time, and instead stay fully tuned in to the program. Parents can encourage their children to do activities that require calm concentration, such as crafts, prayer, reading, science experiments or playing a musical instrument.

Talk about stress. Parents can teach their teens to talk to them and other family members daily about their stress. Even if their teen seems unwilling to open up, they can try to ask about stress on a daily basis and discuss ways they can handle their own stress. When adults show teens how they actively cope with stress, they tend to repeat their good skills. Parents can encourage teens to set limits on how much they absorb peers’ stress. Teens listening to their friends is OK, but always feeling the pressure to solve their problems is not.

I advise parents that if they think their teen needs more help dealing with stress and anxiety, they should talk to their pediatrician or search for a mental health provider. While family is often the best place to learn coping skills for stress, sometimes teens’ mental health requires careful evaluation and psychotherapy. For example, cognitivebehavioral therapy has been demonstrated as an effective and quick intervention to help teens learn stress management.12

By teaching teens to be proactive in building the tools needed to live happier and more balanced lives, they can gain confidence to better manage everyday stress.

ELENA MIKALSEN is the chief of pediatric psychology at CHRISTUS Children’s in San Antonio

and an associate professor of pediatrics at Baylor College of Medicine.

1. “The Most Important Statistics About Teen Stress,” The American Institute of Stress, https://www.stress. org/more-stress-information/#teen-stats.

2. “Stress in America 2023: A Nation Grappling with Psychological Impacts of Collective Trauma,” American Psychological Association, November 1, 2023, https://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/2023/11/ psychological-impacts-collective-trauma.

3. “Social Media and Youth Mental Health: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory,” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2023, https://www.hhs.gov/sites/ default/files/sg-youth-mental-health-social-mediaadvisory.pdf.

4. Jonathan Rothwell, “Teens Spend Average of 4.8 Hours on Social Media Per Day,” Gallup, October 13, 2023, https://news.gallup.com/poll/512576/teensspend-average-hours-social-media-per-day.aspx.

5. Rothwell, “Teens Spend Average of 4.8 Hours on Social Media Per Day.”

6. “Social Media and Youth Mental Health: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory.”

7. “The 2022 United States Report Card on Physical Activity for Children and Youth,” Physical Activity Alliance, 2022, https://paamovewithus.org/wp-content/ uploads/2022/10/2022-US-Report-Card-on-PhysicalActivity-for-Children-and-Youth.pdf.

8. Lynette L. Craft and Frank M. Perna, “The Benefits of Exercise for the Clinically Depressed,” Primary Care Companion to The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 6, no. 3 (2004): https://doi.org/10.4088/pcc.v06n0301.

9. Melissa Jenco, “AAP Endorses New Recommendations on Sleep Times,” AAP News, June 13, 2016, https://publications.aap.org/aapnews/news/6630/ AAP-endorses-new-recommendations-on-sleep-times.

10. Anne G. Wheaton et al., “Short Sleep Duration Among Middle School and High School Students — United States, 2015,” Centers for Disease Control, January 16, 2018, https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/67/wr/ mm6703a1.htm.

11. Maanvi Singh, “Less Sleep, More Time Online Raise Risk For Teen Depression,” Your Health, NPR, February 6, 2014, https://www.npr.org/sections/ health-shots/2014/02/06/272441146/less-sleep-moretime-online-amp-up-teen-depression-risk.

12. Stefan G. Hofmann et al., “The Efficacy of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy: A Review of Meta-Analyses,” Cognitive Therapy and Research 36, no. 5 (July 2012): 427-440.

KELLY BILODEAU Contributor to Health Progress

Medical misinformation used to arrive on the back of a magazine or matchbox cover. Ads for questionable, gimmicky products were often clunky, unsophisticated and met with an eye roll.

“I’m not going to be able to go buy a belt and put it around my waist and have it jiggle, and that’s going to suddenly make me have that beautiful hourglass figure,” said Robin Henderson, chief executive of behavioral health at Providence Oregon.

But thanks to social media, medical falsehoods are now served in quick digital bites that are entertaining, believable and ubiquitous. Nearly 30% of the information people encounter online is false, according to the American Psychological Association (APA).1 “It’s a lot more slick, credible and enticing,” Henderson said.

This deluge of false health information creates problems in the doctor’s office, where it’s a struggle to debunk erroneous information to keep teens healthy.

“It has made our jobs a little bit more difficult at times and required us to be way more intentional in the way that we approach our patients. We need to engage and search out what they may be thinking and seeing, and then replace that with trusted information,” said Dr. Benson Hsu, a pediatric critical care specialist at Avera McKennan Hospital & University Health Center in Sioux Falls, South Dakota.

Health professionals and organizations, such

as the APA and the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), have been studying this new media landscape to determine the best way to steer teens away from false facts. Health care providers are gaining ground in this fight using novel tools and an enhanced understanding of how misinformation spreads and how to combat it. But it’s still a sizable challenge. “We haven’t quite figured out the secret sauce in social media, how to debunk myths and get accurate information out there,” Henderson said.

More health care organizations need to start communicating online. There’s not enough reputable information to balance out the nonreputable sources, said Dr. Alisahah Jackson, president of CommonSpirit Health’s Lloyd H. Dean Institute for Humankindness & Health Justice.

The spread of misinformation online is insidious because it’s effective. Video shorts or influencer content may be emotionally charged and seemingly aimed at keeping people “safe,” which increases the urgency to share it.2 Social media algorithms reward engagement, not accuracy. A teen who shows interest by clicking on a fake story may be fed a steady diet of problematic content,

which can reinforce the information. Research shows people are more likely to believe the same false information when exposed to it multiple times, according to the APA.3

Not surprisingly, teens may have trouble telling the difference between reliable and questionable information. One study published in Frontiers in Psychology found that less than half of teens trusted accurate health messages more than phony ones, and 41% thought that fake and real messages were equally trustworthy.4 People are also more likely to believe fake information if it confirms already held beliefs, aligns with their identity or worldview, or they are feeling emotional when they see it, according to the APA.5 Compounding the problem, one study found people were 70% more likely to share a fake story than a real one.6

Information that teens encounter doesn’t only affect themselves. They may share the information with older relatives. A patient navigator at CommonSpirit Health sent a woman a text message to schedule a COVID-19 vaccine appointment. “She responded back and said, ‘My grandkids are telling me not to take this vaccine, so I’m going to hold off,’” said Brisa Hernandez, system director of operations at CommonSpirit’s Lloyd H. Dean Institute for Humankindness & Health Justice.

misinformation during aimless scrolling. In other instances, they’re looking for answers often on topics they’re embarrassed to ask about, such as sexual health, appearance, weight or dieting, Hsu said.

Parents or providers are often alerted during a casual conversation that a teen has encountered misinformation. For Dr. Anisha Abraham, a pediatrician and spokesperson for AAP, it was a strange request from her teenage son about shampoo that tipped her off. He asked to buy a pricey brand to avoid stripping the oils out of his hair. “And I said, ‘Why am I paying $30 for this bottle of shampoo, and where did the stripping your oils come from?’” she said. “It was just this really interesting conversation.”

“The average age that young people start dieting is age 9 in the United States, which is really disturbing. There’s so much targeting to young people that can lead to either disordered eating or binge eating or other eating-related issues.”

— DR. ANISHA ABRAHAM

Why is there so much misinformation online? The reasons vary. Some of it is misinformation or incorrect or misleading content often spread unwittingly. Some content is deliberately deceptive, defined as disinformation.7

“I do believe that the monetary aspect of things probably has affected the desire to put out clickbait, things that will attract attention and viewership,” Avera’s Hsu said. “There is definitely a financial incentive to do that.”

Teens, who spend an average of 4.8 hours a day on social media, are at high risk for exposure to misinformation, according to the APA.8 Nearly 90% of their time is spent on the three most popular social media channels: TikTok, Instagram and YouTube. Sometimes teens encounter medical

Another red flag is a change in habits. Some teens have been swearing off sunscreen or looking to take specific supplements, CommonSpirit’s Hernandez said. Or it could be a shift in eating habits. There is a huge market for weight loss products, and kids start to feel the pressure to be slim early. “The average age that young people start dieting is age 9 in the United States, which is really disturbing,” Abraham said. “There’s so much targeting to young people that can lead to either disordered eating or binge eating or other eating-related issues.”

These topics prey on common insecurities, for example, the desire to build muscle, which can lead teens to seek out expensive, often unnecessary, and potentially dangerous supplements or steroids.

Helping kids become savvier about online risks also includes educating them about companies that may target them to make money. “The vaping industry very much targets young people,” Abraham said. “I’ve had conversations with kids and say, ‘Look, they don’t offer caramel-flavored

products for adults. It’s for you because they know that if a 13- or 14-year-old starts vaping, they have a lifelong vaper or smoker. Doesn’t that make you really angry that you’re being targeted and that they want your money and they want you hooked?’”

FINDING SOLUTIONS

Finding solutions and keeping kids on the right track isn’t easy. “Even as a parent and a pediatrician, I don’t always know what my kids are hearing and seeing,” Abraham said. However, health care providers can help ensure kids get accurate health information by using key strategies.

Become a trusted resource.

Doctors and nurses are among the most trusted professionals, CommonSpirit’s Jackson said. That can help make teens more receptive to taking their advice. “If you have a longitudinal relationship, if it’s somebody that you’ve seen as they’ve grown up, I think that’s an important way to build that trust as you engage them on topics,” Hsu said. That relationship should extend not only to the teen but to the family. Encourage parents to reach out with questions or concerns.

Study the media landscape.

It’s crucial to understand the information kids are being exposed to that might affect their health. For example, CommonSpirit Health embarked on a study in 2021 to understand vaccine hesitancy in their communities.9 They found that while many people were wary of vaccines, the reasons why they opted not to get the shot were very different between their study groups, Latinos in California’s Central Coast area and Black Americans in Little Rock, Arkansas. Don’t assume that patients are motivated by the same factors; ask.

Ask broad questions.

Go beyond the traditional screening topics when working with teens, which usually center around medical and safety-related topics such as selfharm, firearms, injury prevention and vaccines. “I think it’s important for providers to engage in things that may not necessarily fall under the umbrella of our usual health care topics, and to provoke discussion with teenagers and adolescents about things that they may be searching on their own, that they may be embarrassed to bring up in a clinic visit,” Avera’s Hsu said.

Tread lightly.

If a teen does believe misinformation, handle the discussion carefully.

Sometimes the best approach is to ask questions, allowing teens to come to their own conclusions. “It’s really creating a trusted, safe environment, and coming at it with a sense of curiosity, not judgment,” Hsu said. “Don’t say, ‘Well, obviously that’s wrong.’ Instead ask, ‘Why do you believe that?’”

The same approach can also apply to parents, who are paddling in the same sea of misinformation. “I don’t believe there are adults out there who intentionally want to mislead their kids,” Hsu said. “I think all adults are coming from a place of care and compassion. But they’re seeing their feed filled with information that I don’t necessarily agree with or that I believe is scientifically accurate.” Approach the discussion in good faith. “I think that’s way more effective than to come down and say, ‘Oh my gosh, I can’t believe you believe that that is so inaccurate and so wrong,’” he said.

Ultimately, patients have the right to make their own choices. “At the end of the day, we still have to be open to the fact that our patients and parents have opinions that may be different than ours, and we will have to agree to disagree,” AAP’s Abraham said.

Block and report. Don’t interact.

Let teens know they should respond to questionable information by unfollowing or blocking it. The same advice is also true for providers who may be tempted to comment on social media posts to debunk misinformation. Engaging with bad information can amplify it, expanding engagement.

“What we know is most effective is actually to report it,” Hsu said. This strategy can be frustrating because reporting may feel like playing WhacA-Mole. “It’s very easy to shut down an account and open another account to post the same thing again. But it’s just part of the battle,” Hsu said. “We have to just keep being engaged.”

Provide an alternative.

When teens encounter false information, doctors can debunk it by correcting the record with detailed factual information. Giving people accurate information up front, or “prebunking,” can also make them less likely to believe false facts, according to the APA.10 Some organizations are

prebunking by using online resource centers and educational outreach to schools, sports teams and even local media organizations.

“Providence has steeped themselves in this, especially when it comes to youth mental health,” Henderson said. “We’ve invested in developing a curriculum that’s free of charge, available to any district in the country.”

The organization collaborated on a free teen mental health website, Work2BeWell.org, which includes a host of validated resources to keep teens in safe corners of the internet, Henderson said. This information includes controversial topics.

Work2BeWell partnered with the documentary Hiding in Plain Sight: Youth Mental Illness to develop curriculum focused on youth mental health, including self-harm. “I heard from a parent recently who was saying, ‘Oh my gosh, if my kid watches this, they’re going to learn about self-harm,’” she said. But it’s far better for teens to learn about a challenging issue in a controlled environment rather than encountering risky content when scrolling alone online.

Establish an online presence.

There aren’t a lot of health care organizations with a strong online presence in the social media sphere aimed at addressing misinformation and disinformation. But that’s slowly changing.

CommonSpirit hopes to establish a foothold on social media channels, such as Instagram, Facebook and LinkedIn, to get evidence-based medicine and health-related information to patients, Jackson said. “It is still pretty new, but we have a social media communications platform strategy,” she said. “We’re really looking at making sure that people are aware of the science of kindness, compassion, empathy and trust.”

Amplify reliable sources.

Teens like to get information online, so providers can help ensure they get accurate information by recommending reliable material. “We verified everything that’s on our Work2BeWell site. Every resource we list has been verified, and we have a 50-state resource list, so there’s something for everybody in every state. It’s all clinically verified and free,” Henderson said. “A lot of sites that seem really credible, as you dig into them, they’re trying to sell you something. And that’s my first red flag.”

It’s far better for teens to learn about a challenging issue in a controlled environment rather than encountering risky content when scrolling alone online.

Speak out when dangerous misinformation arises. Appropriate organization leaders can reach out to local media if particularly troubling information starts to spread online. They’re usually willing to provide information that corrects the record and prevents harm.

Choose the right voice.

Kids tend to be more receptive to information when it comes from peers, so Henderson said they’ve developed tools that include teen voices, such as Work2BeWell’s podcast Talk2BeWell. “We have over 100 podcasts on Talk2BeWell that talk about different youth mental health issues of all shapes and sizes. Having them listen to other teens talk about something [is a] whole lot better than having them listen to a group of adults,” Henderson said.

Take a lesson from others.

Other countries are seeing some success with education initiatives designed to target online misinformation. “I think we can learn from other countries. Sweden and Denmark, for example, have implemented a curriculum in their schools for kids around how they can use social media, and how to discern what’s true and not true,” Jackson said.

MOVING THE NEEDLE TOGETHER

Ultimately, navigating online misinformation and disinformation is a huge challenge for the medical profession, and it’s a problem that won’t be solved anytime soon. However, a team approach can help move the needle.

“I think what we have to do is really work together within our communities, between health care and our educational system and with other parents to network, watch the trends and debunk these myths as a community together when we can,” Henderson said.

KELLY BILODEAU is a freelance writer who specializes in health care and the pharmaceutical industry. She is the former executive editor of Harvard Women’s Health Watch. Her work has also appeared in The Washington Post, Boston magazine and numerous health care publications.

1. “Using Psychological Science to Understand and Fight Health Misinformation: An APA Consensus Statement,” American Psychological Association, https:// www.apa.org/pubs/reports/misinformationrecommendations.pdf.

2. “Confronting Health Misinformation, The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on Building a Healthy Information Environment,” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2021, https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/ surgeon-general-misinformation-advisory.pdf.

3. Tori DeAngelis, “Psychologists Are Taking Aim at Misinformation with These Powerful Strategies,” American Psychological Association, January 1, 2023, https://www.apa.org/monitor/2023/ 01/trends-taking-aim-misinformation.

4. Suzanna Burgelman, “41% of Teenagers Can’t Tell the Difference Between True and Fake Online Health Messages,” August 29, 2022, Frontiers, https://www.frontiersin.org/news/2022/08/29/ psychology-teenagers-health-fake-messages/.

5. DeAngelis, “Psychologists Are Taking Aim at Misinformation.”

6. “Confronting Health Misinformation.”

7. “Health Misinformation,” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, https://www.hhs.gov/ surgeongeneral/priorities/health-misinformation/ index.html.

8. Tori DeAngelis, “Teens Are Spending Nearly 5 Hours Daily on Social Media. Here Are the Mental Health Outcomes,” American Psychological Association, April 1, 2024, https://www.apa.org/monitor/2024/04/ teen-social-use-mental-health.

9. Brisa Urquieta de Hernandez et al., “A Health System’s Approach to Using CBPR Principles with Multi-Sector Collaboration to Design and Implement a COVID-19 Vaccine Outreach Program,” Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved 33, no. 4 (November 2022): https://dx.doi.org/10.1353/ hpu.2022.0172.

10. “Psychological Science Can Help Counter Spread of Misinformation, Says APA Report,” American Psychological Association, November 29, 2023, https://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/2023/11/ psychological-science-misinformation-disinformation.

With misinformation on the internet growing, so does the need for helping teens distinguish between truths and falsehoods. As health care ministries, we are simultaneously tasked with keeping them safe and giving them access to reliable information.

1. Author Kelly Bilodeau writes in her article that, according to the American Psychological Association, nearly 30% of the information people encounter online is false. This presents a huge challenge for everyone but especially for teens, who may be looking for quick answers and may not be as discriminating as adults when it comes to vetting sources. As health care providers, how can we help teens navigate such a difficult landscape and share reliable resources that they can use instead?

2. Bilodeau also mentions in her article that teens often turn to the internet for answers when the topic is something they are too embarrassed to ask about, such as sexual health, appearance, weight or dieting. What can health care providers do to make teens more comfortable in asking them for help with their most pressing questions, rather than leaning away from them and turning to unreliable sources?

3. According to the article, teens are spending 90% of their social media time on three main platforms: TikTok, Instagram and YouTube. The more these platforms learn about teens’ habits, the more their algorithms influence their choices and what they see on social media. How can we counteract this? As health care professionals, is there a way we can debunk misinformation, such as by creating online resource centers or conducting educational outreach to schools?

CECELIA HORAN, PsyD Director of Child & Adolescent Services, Ascension Illinois Alexian Brothers Behavioral Health Hospital