Our Lady of the Lake’s Faith Fund counters predatory lenders

By LISA EISENHAUER

Our Lady of the Lake Regional Medical Center in Baton Rouge joined a coalition of organizations determined to convince the Louisiana State Legislature in 2015 to rein in payday lenders, whose predatory practices were ensnaring some of the medical center’s team members.

The coalition wanted the state to put an end to tactics that drive interest rates on the lenders’ short-term loans outrageously

CENTERING CARE ON MOMS-TO-BE

high, in some cases up to 3,000%. Their effort didn’t end well.

“We failed miserably,” recalls Coletta Barrett, vice president for mission at Our Lady of the Lake. In effect, Barrett says the lawmakers told the coalition: “These poor people have no other options or alternatives. You just need to continue to let them be prey.”

Rather than throwing in the towel, Our Lady of the Lake and others decided to

Continued on 2

CommonSpirit sees care navigation networks gain momentum

By JULIE MINDA

It’s been about a year since CommonSpirit Health formally launched community health worker networks in six of its markets and several of those networks are gaining traction and having a measurable impact on the lives of vulnerable people who previously had struggled to access health and social services.

Working with the nonprofit Pathways Community HUB Institute, CommonSpirit spurred the creation of, and provided seed funding for, the networks. The networks engage community health workers in identifying vulnerable individuals and guiding them on specific pathways to attain services so they can address the most pressing socioeconomic concerns they face. Under the approach, the community health workers’ pay is partly based on their ability to

Continued on 6

PACE providers use satellite model to extend services to seniors in congregate housing

Here, yoga and mindfulness instructor Kahlil Kuykendall, left foreground, teaches balancing and stretching poses to, clockwise from center, Nevaeh Weathers, 20, of West Baltimore; Jnai Player, 20, of Baltimore; Destiny Johnson, 22, of West Baltimore; and Keimyra Pumphrey, 21, of Baltimore. Participants learn to advocate for themselves with care providers and they build supportive friendships. Story on PAGE 8 same for a third.

By JULIE MINDA

By JULIE MINDA

About a decade ago Cardinal Timothy Dolan challenged ArchCare — the Archdiocese of New York’s health care ministry — to help develop a solution for the growing number of elderly clergy who wished to age in place but whose congregations could not meet their health care needs.

ArchCare came up with an effective answer: It would extend the comprehensive medical and social services ArchCare already provided frail seniors through its PACE centers to the retired clergy in the congregate living centers they called home. Since then, ArchCare has created PACE center satellites for two congregations in New York state and is preparing to do the

“Cardinal Dolan wanted retired religious to get services from an organization that understands the importance of them staying in religious community,” says ArchCare President and Chief Executive Scott LaRue. “We developed a program to meet those needs and that allows much independence for the religious (men and women). We understand religious communities. This is the perfect fit for a health care ministry of the church.”

PACE stands for Program of AllInclusive Care for the Elderly. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services pay PACE providers to deliver comprehensive medical and social service to keep frail, elderly

Trinity’s brand campaign

Executive

Master class in mission 3 Continued on 4

5

changes 7

Loans since founding 1,742 Total loaned $6.4 million Average interest rate 5.9% Retained wealth for borrowers $18 million

A Sister of Charity of New York strolls with a staff member at the Kittay Senior Apartments in New York City. An ArchCare Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly provides services to sisters at the complex, so that they can age in place.

THE FAITH FUND

Research shows that the CenteringPregnancy group prenatal care model in use at Mercy Medical Center in Baltimore improves birth outcomes for Black women and their babies.

MARCH 1, 2023 VOLUME 39, NUMBER 4 PERIODICAL RATE PUBLICATION

Jennifer McMenamin

The Faith Fund

From page 1 take an if-you-can’t-beat-‘em-join-‘em approach, but with a consumer-friendly twist. In 2018 they launched The Faith Fund.

Since its founding, the microlending fund has provided 1,742 loans totaling $6.4 million at an average interest rate of about 5.9%. The fund’s directors calculate that the loans have resulted in more than $18 million in “retained wealth,” meaning money that otherwise would have gone to pay off interest and fees to payday lenders.

‘Poverty is endemic’

Any resident of the Diocese of Baton Rouge can apply for a loan from The Faith Fund, although 95% so far have been to team members of Our Lake of the Lake or its parent system, Baton Rouge-based Franciscan Missionaries of Our Lady Health System. The system promotes the fund on its intranet and in employee communications.

The fund is a complement to the team member assistance program that FMOLHS started in 2005 to provide grants of amounts that vary depending on the circumstances to workers in urgent need of a onetime financial lifeline. Since 2021 the system also has offered its team members Payactiv, a service that lets them access earned income before payday.

Barrett says the three programs are evidence of the health system’s commitment to its workers and to the common good. “If we can identify things that are pretty endemic in our population — and poverty is endemic — and we have access to sustainable resources to address the systems and structures that got them there in the first place, then that’s our calling, to do what we can,” she says.

The U.S. Census Bureau says 24.4% of Baton Rouge’s population lives below the federal poverty level. That’s more than double the national rate of 11.6%.

FMOLHS FINANCIAL ASSISTANCE PROGRAMS

Franciscan Missionaries of Our Lady Health System offers its 18,000 team members several financial assistance and counseling programs.

Team member assistance fund: This fund offers onetime grants to workers with immediate needs. Workers must submit an application that includes bills and financial documents. They also must agree to financial counseling. The applications are reviewed by HOPE Ministries, a workforce development program that does the financial counseling. HOPE Ministries makes a recommendation to FMOLHS on whether to approve applications. There is no ceiling for grants.

The Faith Fund: Enrollment costs $5. Loan applicants get financial counseling and assistance applying for loans. Loan recipients agree to an affordable repayment plan with withholdings from their paychecks. A small portion of the loan repayments flow into a savings account for the loan recipient, meant to help them build a rainy day fund.

Payactiv: Enrollment is free. For a $5 fee, enrollees can make up to five transactions per pay period via a smartphone app. Workers don’t need permission to access earnings prior to payday. The service also includes tools for budgeting, saving and managing debt.

Financial counseling: The system partners with Lincoln Financial Group to offer a variety of virtual and in-person classes on topics that include budgeting, investing, retirement, Social Security, and financial wellness. In 2022, 509 team members participated in these courses.

Payday lenders typically loan money to people who have incomes but little to no savings and poor credit. A review by The Pew Charitable Trusts found that Louisiana is one of 23 states with few consumer safeguards on payday lending. The review found that, on average, the cost to borrow $500 from a payday lender in Louisiana for four months was $435, or an interest rate of 405%.

Catholic Health World (ISSN 87564068) is published semimonthly, except monthly in January, April, July and October and copyrighted © by the Catholic Health Association of the United States. POSTMASTER: Address all subscription orders, inquiries, address changes, etc., to CHA Service Center, 4455 Woodson Road, St. Louis, MO 63134-3797; phone: 800-230-7823; email: servicecenter@chausa.org.

Periodicals postage rate is paid at St. Louis and additional mailing offices.

Annual subscription rates: CHA members free, others $29 and foreign $29. Opinions, quotes and views appearing in Catholic Health World do not necessarily reflect those of CHA and do not represent an endorsement by CHA. Acceptance of advertising for publication does not constitute approval or endorsement by the publication or CHA. All advertising is subject to review before acceptance.

Vice President Communications and Marketing

Brian P. Reardon

Editor Judith VandeWater jvandewater@chausa.org

314-253-3410

Associate Editor Julie Minda jminda@chausa.org

314-253-3412

Striking out alone

Barrett says it was because of the team member assistance fund that the system became aware of how many staffers had fallen victim to payday loans. Grant applicants are required to submit copies of their bills and financial statements. Although reviews of those documents now are done by a third party, they initially were done by a committee with representatives from various departments within the health system. Those committee members saw how payday loans often were at the root of their colleagues’ financial hardship.

the credit union has a mission to provide financial services to communities that otherwise would have little access.

The partners set up an eight-member oversight board for The Faith Fund. Each organization appoints two members. Barrett is the board’s executive sponsor.

Sustainable funding

A key part of making The Faith Fund sustainable was to identify a funding source to guarantee the loans. That happened with the help of Barrett’s husband, a certified public accountant. He encouraged her to look into how FMOLHS was using the money left over from flexible medical spending and dependent care accounts. Employees fund those accounts with pretax earned income, but eventually unspent dollars revert to the employer.

It took Barrett several phone conversations to find those funds in the budget and then to get approval to have them transferred to the Our Lady of the Lake Foundation. From there, the money was redirected to launch The Faith Fund. The funds covered $50,000 in start-up costs for the loan program. Funds from that source also “reseed” the program as needed.

Depending on the size of the loan, the term usually runs one to two years. Borrowers do not have to put up any collateral, but they do have to agree to have loan payments withheld from their paychecks.

While The Faith Fund initially was envisioned only as a means to provide payday loan relief, Barrett says applicants can request funds for other needs. One urgent need has been relief from car loan scams that are almost as predatory as payday loans. Through its partnership with the credit union, which has an arrangement with car rental giant Enterprise, the fund can help buyers get loans for year-old cars that remain under warranty.

‘A huge blessing’

Crystal Bell is one of the FMOLHS team members who has turned to The Faith Fund for aid. Bell is an administrative assistant to three senior FMOLHS executives, including Pete Guarisco, senior vice president of mission integration. Bell says she was aware of The Faith Fund’s mission since its launch but didn’t expect to be one of its applicants.

Bell first applied for a loan in 2020, when her hours and pay were impacted due to the pandemic. She used the money to make ends meet until her full pay and hours resumed.

“That was a huge blessing to me,” Bell says. “Being a divorced mom with three children, it was a struggle to look at possibly losing my income, so that helped me get through that.”

She was still paying off her original loan when Hurricane Ida hit in 2021 and damaged her house. She got a second loan from The Faith Fund to cover those repairs.

Bell’s car was ruined in a flood and she financed a replacement through a dealership. From The Faith Fund’s financial counselor, Bell says she learned she could refinance her car loan through the New Orleans Firemen’s Federal Credit Union. That change dropped her interest rate to 6.98%, less than half of what the dealership was charging. Her payments were cut significantly while the term of the loan was unchanged.

Bell says the assistance she has gotten through The Faith Fund has been “life changing.” She is now one of FMOLHS’ representatives on the fund’s board.

Even though The Faith Fund’s services are accessible online, its directors wanted a visible presence in the community. With a $150,000 grant from FMOLHS’ sponsoring congregation, Franciscan Missionaries of Our Lady, The Faith Fund opened an office in an economically challenged part of Baton Rouge where many payday lenders have storefronts.

Barrett says the hope is that the office will help the fund become part of the fabric for uplifting the community by addressing issues such as intergenerational poverty.

Pay access with dignity

Associate Editor Lisa Eisenhauer leisenhauer@chausa.org

314-253-3437

Graphic Design

Norma Klingsick Advertising ads@chausa.org

314-253-3418

After getting the brush-off from the state legislature, Our Lady of the Lake in partnership with Catholic Charities of the Diocese of Baton Rouge decided to do an assessment of sustainable microlending programs. They won a $75,000 grant from the Catholic Campaign for Human Development, the domestic anti-poverty program of the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, to fund the assessment.

The study found that there were many alternatives to payday lending that were succeeding in other places with community support. The findings prompted Our Lady of the Lake and Catholic Charities to partner with MetroMorphosis, a nonprofit focused on urban renewal in Baton Rouge, to develop their own program.

The three put out a request for proposals for a fourth partner to take on the fiscal duties. They settled on the New Orleans Firemen’s Federal Credit Union. As a community development financial institution,

As part of the partnership, Our Lady of the Lake makes up 60% of loan defaults. The credit union secured a $1 million grant that it uses to cover the other 40%. So far, the fund’s default rate has not exceeded 6.3%. That is below what Barrett says is the industry standard of about 10%.

She describes The Faith Fund and the team member assistance fund as “great rescue and emergency strategies,” but neither provided a means for workers to get in front of sudden expenses. That was why the system began offering Payactiv’s service, to give employees access to their earnings without having to wait until payday.

In the fund’s first years, 879 FMOLHS team members, about 5% of the almost 18,000-member workforce, have enrolled in Payactiv. Just under half are in the system’s lowest pay rungs, earning between $12-$16 an hour; the rest are spread across the pay scale. The members’ pay advance requests average about $100. To date, the advances total more than $2.8 million.

Payactiv didn’t require any investment from FMOLHS except staff hours from information technology and human resources employees to set up access to payroll records.

Barrett says one of the blessings of Payactiv is that it empowers team members. Workers don’t have to make an appeal to anyone or reveal any details of their finances to get their pay ahead of schedule.

“This is true dignity at work,” she says. “I don’t have to ask anyone’s permission to access funds that I’ve already worked for and earned.”

— Coletta Barrett

leisenhauer@chausa.org

© Catholic Health Association of the United States, March 1, 2023

“If we can identify things that are pretty endemic in our population — and poverty is endemic — and we have access to sustainable resources to address the systems and structures that got them there in the first place, then that’s our calling, to do what we can.”

2 CATHOLIC HEALTH WORLD March 1, 2023

Crystal Bell, rear, and her daughter Brenna Leigh Bell pose in front of the car Crystal was able to refinance through a credit union affiliated with The Faith Fund. The refinancing slashed the interest on the family’s car payment by more than 50%. Crystal is an administrative assistant at Franciscan Missionaries of Our Lady Health System.

Providence St. Joseph institute helps ‘culture bearers’ deepen their inner lives

Formative experiences guide participants in self-renewal, spiritual growth and community building

By JULIE MINDA

An institute that Providence St. Joseph Health launched in November 2021 is guiding leaders across the system in developing a richer spirituality and inner life so that they can better engage in carrying out Providence’s mission.

The Mission Leadership Institute includes an academy that provides hundreds of Providence leaders at a time with experiential learning, presentations from experts on mission-based leadership and team building with colleagues across the system. Another institute program helps aspiring and new mission leaders to discern their calling. And a third offering promotes the spiritual growth and well-being of established mission leaders.

Martin Schreiber is vice president of the Mission Leadership Institute. He says the institute focuses on forming leaders at every level of the organization — at facilities throughout Providence — for centering their work around mission. “We’re responding to a need for a new type of leadership — for leaders who are more richly developed.”

He says the institute is guiding participants in self-development, self-renewal and community building. “We want them to be able to bring their whole self” to their work, he says.

Search for meaning

Schreiber, who has a doctorate in education and a master’s in divinity, has been working in mission leadership roles in Catholic health care for a decade — first at what was Presence Health and then at Chesterfield, Missouri-based Mercy before joining Renton, Washington-based Providence in June 2020. (In 2018 Ascension acquired Presence Health, which was an Illinois health system.)

In addition to Schreiber, the institute’s full-time staff includes Crystal Hasan and Nancy Jordan. Hasan is senior program manager and leads the institute’s operations and program implementation. Jordan is associate vice president of the institute

and directs curriculum and instruction.

Schreiber, Jordan and Hasan were creating the institute during the height of the pandemic when Schreiber says so many health care staff and leaders were burning out and pondering questions of life’s meaning — and this brought to the fore the need to help Providence staff nurture their well-being and growth.

Schreiber met with mission leaders at Providence and at other health care facilities across the U.S. to generate ideas for the institute’s programming.

The institute’s offerings complement Providence system and facility formation programming, says Schreiber.

Culture bearers

The institute recruited participants by asking nearly 1,000 executives across Providence’s seven-state network to nominate leaders on their teams who those executives view as “culture bearers,” people who influence and guide the culture in their facilities. The nominees could be from any department in any of Providence’s facilities. The institute selected its first cohort of about 300 associates last year, aiming for diversity, including when it came to participants’ geographic locations, backgrounds and job roles.

Cohort members have been meeting every other month, and will do so for 15 months. Each meeting lasts two days. The institute’s staff has broken the cohort into geographically determined pods that range in size from about 20 to 60 people each.

Members meet in-person at locations central to their pod group.

Each academy session includes reflections, presentations, discussions and sensory experiences. The presentations on mission topics are delivered in live broadcast format by people the institute calls luminaries. Speakers have included Chris Lowney, CommonSpirit Health board chair; Maureen Bisognano, president emerita and senior fellow of the Institute for Healthcare Improvement; Carolyn Woo, past president and chief executive of Catholic Relief Services and now fellow for global development at Purdue University; Sr. Mary Haddad, RSM, CHA president and chief executive officer; and Dr. Ira Byock, founder and senior vice president for strategic innovation for the Institute for Human Caring at Providence.

The topics the presenters explore have to do with key Catholic health care principles including human dignity, care that addresses people’s needs holistically, empowerment of the vulnerable, the pursuit of the common good, the desire for justice, the importance of stewardship and the essentiality of the Catholic Church’s health care ministry. Questions and discussions are encouraged.

Interspersed with the presentations are interactive learning labs that engage the senses — and the intuition — of academy participants to make them more astute observers and more attentive listeners. Drawing on sensory experiences while cooking, “forest bathing” or listening to

Upcoming Events from The Catholic Health Association

play lists curated by a symphony director, teaches participants to use their senses be more present and fully engaged in the moment, Hasan explains.

Jordan says each academy pod completes a “signature assignment,” which she describes as “a collective capture of participant learnings in an electronic portfolio.” She says through word, photos, videos, and other expressions, pod members document concepts and experiences that inspire them during their time in the academy.

Academy participants earn a certificate worth 12 graduate credits in mission leadership from the University of Providence.

The next academy cohort starts in November.

Mission leader support

The institute is offering a graduate certificate worth 12 graduate credits in mission integration from the University of Providence for Providence associates who are discerning a mission leadership vocation. This mission integration programming is similar to the other graduate certificate but contains additional coursework related to mission integration for leaders.

Aspiring mission leaders are paired with experienced ones to have dialogues on topics covered in the coursework. The institute calls the aspiring mission leaders “pilgrims” and their partners “companions.”

The institute also offers a “masterclass” for more seasoned mission leaders at Providence that takes a deep dive into mission leadership topics.

Schreiber says that while the overwhelming majority of institute students are Providence staff, there are a few Seattle archdiocese leaders taking part in the academy. The system plans to open program participation to leaders from other organizations as well, including ministry systems and facilities. Academy participants from outside Providence will pay tuition.

Sacred space

Heidi Davis manages a community teaching kitchen and food pantry for Providence Milwaukie Hospital in Milwaukie, Oregon, about 7 miles outside of Portland. Programming is focused, Davis says, on nourishing wellness while improving food security through nutrition counseling, culinary medicine, food pharmacy and community outreach. Culinary medicine teaches patients what foods are best for their individual conditions, and food pharmacies increase access to healthy foods.

Davis is part of the academy class that began in November 2021 and concludes this month. She’s built relationships with colleagues throughout her region, many of whom she’d never met before. She says her pod mates are a “tribe of people to talk with” about a range of mission-related topics.

Through large- and small-group discussion, reflections and resources and personal journaling, she says she’s been growing spiritually. Davis says she’s gained a greater understanding of what it means to be a mission-centered leader and how to nurture that aspect of herself. Alignment with mission “calls for internal and external congruency,” she says. She adds that the institute has given academy participants a sacred space to explore how they can become more engaged and invested in their role as leaders in a Catholic health ministry.

“At Providence mission is the compass for leadership at every level,” she says.

jminda@chausa.org

Deans of Catholic Colleges of Nursing Networking Zoom Call March 7 | 1 – 2 p.m. ET Sponsorship Institute: The Art of Partnership March 15-17

only) Theology and Ethics Colloquium: Catholic Identity and American Culture March 15-17 (Invitation only) Global Health Networking Zoom Call May 3 | 1 – 2 p.m. ET Mission in Long-Term Care Networking Zoom Call (Members only) June 7 | 1 – 2 p.m. ET Assembly 2023 (Virtual) June 12-13

(Invitation

A Passionate Voice for Compassionate Care® chausa.org/calendar

At a ‘sound bath’ in September, participants in the Providence St. Joseph Health Mission Leadership Institute relax as they concentrate on the tones emanating from a singing bowl. The curriculum exposes people to sensory experiences to heighten their observation skills.

Schreiber

Davis

Hasan

Jordan

March 1, 2023 CATHOLIC HEALTH WORLD 3

Nick Perkiss, Providence

PACE satellite model

From page 1

participants out of nursing homes and living in the community. With few exceptions, participants have low incomes and are covered by both Medicare and Medicaid insurance.

Trinity Health PACE’s MERCY Life program has had similar success extending the PACE model of care to men and women religious in congregant living. And both ArchCare and Trinity Health PACE have been taking PACE programs to secular congregate living developments, including low-income apartment complexes for seniors.

Anne Lewis, chief operating officer of Trinity Health PACE, says, “As a Catholic health care ministry, our core values and mission closely align with those of the religious communities we serve. We are grateful to be able to give back to our founding orders by providing supportive services in the place the religious members call home.”

She adds, “We are open to all opportunities to expand PACE. PACE expansion is near and dear to our hearts.”

Opportunity for creativity

According to the National PACE Association, PACE is for people aged 55 or older and certified by the state to need nursing home care although capable of living safely in the community with the benefit of supportive services.

PACE provides its enrollees with primary medical care; referrals to medical specialties; behavioral health services; physical, occupational and recreational therapy; prescription drug benefits; meals; nutritional counseling; adult day care; home health care; personal care assistance; social services; caregiver respite care; and other services that allow frail clients to age in place in their homes.

Most of these services are provided in PACE centers and at enrollees’ homes. PACE coordinates hospital and nursing home care for participants.

Currently there are 149 PACE programs operating 306 PACE centers in 32 states. In 2021, the National PACE Association launched a broad-based effort to help PACE organizations grow more quickly. Its strategies included efforts to broaden the PACE eligibility criteria to open the program to younger people with life-altering disabilities.

If they qualify based on age, income and their disability status, older adults in the numerous housing complexes surrounding Draper Hall in East Harlem also can join that PACE program. ArchCare expects there will be a lot of Hispanic and Chinese clients and it is hiring staff who speak the enrollees’ languages.

ArchCare is contracting to provide PACE services to adult home facilities in the Bronx and Staten Island for seniors, many of whom have complex health needs. The facilities are run by the W Group Assisted Living Communities, an operating company that runs 21 senior housing facilities in New York and one in Florida.

At the satellite outposts, ArchCare hires and employs all the PACE staff, and ArchCare maintains the relationship with and receives capitated payments for enrollees’ care from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. LaRue says providing PACE in satellite locations is not a revenue generator but more of a break-even venture for ArchCare.

Elizabeth Rosado, vice president of PACE for ArchCare Senior Life, says there’s no “one-size-fits-all” when it comes to how ArchCare provides PACE services. Rosado says of enrollees, “We make sure we’re honoring all their wishes, when it comes to how they want to be cared for.”

In some cases, the hub center’s staff goes to the satellite location to provide services to the seniors there. In other cases, PACE staff members exclusively care for seniors in their residences.

LaRue says seniors who take advantage of PACE offerings suffer less social isolation, and have better quality of life and better health outcomes than peers not enrolled in PACE.

Relationship building

Trinity Health PACE owns or manages 14 PACE programs in nine states, that have a total of 22 PACE centers. Its Mercy LIFE PACE program in Philadelphia uses the satellite model to provide services to retired members of four Pennsylvania religious communities: the Sisters of Mercy at McAuley Convent in Merion Station, the Sisters of Saint Francis at Assisi House in Ashton, the Sisters of the Immaculate Heart of Mary at Camilla Hall in Malvern and the Jesuits’ Manresa Hall in Merion Station.

their reach by offering their services via the satellite model in buildings and neighborhoods with clusters of PACE-eligible people.

These areas of expansion included housing complexes subsidized by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development or Veterans Administration and assisted living complexes.

An equalizer ArchCare has PACE centers in Manhattan, the Bronx, Staten Island and Westchester. About eight years ago, it signed on to establish PACE services — as an extension of its Bronx PACE center — at Murray-Weigel Hall, a close-by residence owned by the Jesuits that houses retired Jesuits. PACE has 39 Jesuit clients at Murray-Weigel Hall.

Soon after bringing PACE to the Jesuits, ArchCare began offering PACE services from its Harlem PACE center for retired Sisters of Charity at a nearby supportive housing complex called the Kittay Senior Apartments. It currently has about 20 sisters enrolled in PACE at the complex. Later this year, ArchCare will begin providing services out of its Westchester PACE center to sisters at two convents in Rockland County, New York.

Last month, ArchCare launched PACE services through the satellite model for residents of Draper Hall, a governmentsubsidized 201-apartment building which has been renovated for low-income seniors.

Trinity Health PACE provides services to more than 250 clergy between the four sites. Mercy LIFE staff operate out of PACE centers to deliver their services to the men and women religious in their residence halls. Clergy clients can receive services at the PACE centers as well.

Trinity Health PACE provides PACE services to several secular sites. It opened Mercy LIFE Valley View in 2014 at a residential campus in Elwyn, Pennsylvania, for seniors who are deaf. Currently 23 people there receive PACE services. And in fall 2022, Mercy LIFE launched PACE services at Kinder Park Community in Woodlyn, Pennsylvania. The affordable housing complex for seniors is operated by the Delaware County Housing Authority.

As with ArchCare, Trinity Health PACE maintains the relationship with CMS.

When it comes to the sites serving women and men religious, Mercy LIFE has a staffing agreement with the religious communities, based on the number of congregation members enrolled in the program. Under this arrangement, Mercy LIFE pays for the staff working with congregation members enrolled in PACE.

Lewis says Mercy LIFE staff work to understand the religious communities or the secular partner organizations and the characteristics and needs of the PACE participants living in those communities. “We learn what they want and what they don’t want.”

It’s all about what will work for the partner organizations and their members, she says.

jminda@chausa.org

Trinity Health PACE provides Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly services in Pennsylvania through the Mercy LIFE program. In Philadelphia, Mercy LIFE clients include retired members of a Jesuits order at Manresa Hall in Merion Station. Fr. Joseph Godfrey is among those receiving the PACE services.

Lewis

Trinity Health PACE’s Mercy LIFE provides PACE services to residents of Mercy LIFE Valley View in Elwyn, Pennsylvania. Valley View is the first PACE program in the United States to serve a community of deaf senior adults. Here from left, PACE participants Alice Grube and Clara Baxter play a game with Montel Little, senior recreation assistant.

An ArchCare staff member provides PACE services to a Sister of Charity at New York City’s Kittay Senior Apartments.

Robert Greenwood, National PACE Association senior vice president of communications and member engagement, says even before the 2021 expansion effort began, PACE centers had been extending

4 CATHOLIC HEALTH WORLD March 1, 2023

Greenwood

Mercy signs letter of intent to acquire two-hospital southeast Missouri system

Mercy of Chesterfield, Missouri, is in negotiations to acquire SoutheastHEALTH, a two-hospital system in Cape Girardeau, in southeast Missouri.

If the acquisition is finalized, Mercy’s sponsor body, Mercy Health Ministry, would become the “sponsoring entity” of SoutheastHEALTH, said Ajay Pathak, Mercy senior vice president and chief strategic ventures officer.

SoutheastHEALTH would become a Catholic organization, adhering to the Ethical and Religious Directives for Catholic Health Care Services

He said the organizations have yet to determine the financial specifics of the deal.

SoutheastHEALTH is a secular system with a 244-bed flagship hospital in Cape Girardeau and a 48-bed hospital in rural Dexter, Missouri. SoutheastHEALTH also has a network of 50-plus primary and specialty care clinics and other facilities.

Mercy has more than 40 acute care, managed and specialty hospitals and a network of other facilities in Missouri, Arkansas, Oklahoma and Kansas. Mercy Hospital Jef-

ferson in Festus, Missouri, is the Mercy hospital that is closest to SoutheastHEALTH’s main campus in Cape Girardeau. The distance is about 80 miles.

Mercy and SoutheastHEALTH are conducting due diligence and expect to complete a definitive agreement in the summer. A press announcement says the organizations anticipate the integration will take place in the fall.

SoutheastHEALTH’s board had determined the organization should join a larger system and it issued a request for proposals. The board selected Mercy from among respondents. SoutheastHEALTH President and Chief Executive Ken Bateman said in the announcement that Mercy was selected because it was the best strategic fit. This is in part because of its strong willingness to invest to expand health care access and make the system a regional hub in southeast Missouri and in the tristate area SoutheastHEALTH serves.

Mercy will host community listening sessions and planning exercises in southeast Missouri in preparation for the transition of ownership.

Pathak said Mercy and SoutheastHealth will work together to come up with a new name for the acquired entitity that honors the system and community.

Trinity Health spotlights its brand in ‘We See All of You’ campaign

Trinity Health has launched its first brand marketing campaign. Its tagline “We See All of You” spotlights the system’s brand promise to deliver holistic care that recognizes the interconnectedness of body, mind and spirit.

A media release called the national campaign “a natural progression for Trinity Health as it continues to grow and leverage the knowledge and expertise of a large national health system to improve care, access and the patient experience in each of

the communities it serves.”

Three regional health systems across five states introduced the campaign in January. Those systems are Trinity Health MidAtlantic in southeastern Pennsylvania and Delaware; Trinity Health Michigan in western and southeastern Michigan; and Trinity Health Of New England in Connecticut and Massachusetts.

The system developed the campaign with Detroit-based advertising and marketing communications agency Campbell

Ewald. The multimedia campaign includes TV, radio, social media and print ads highlighting specialty medicine, including cancer and cardiac care and how these services are delivered with “personalized care.” The campaign has been integrated into the Trinity Health, Trinity Health Mid-Atlantic, Trinity Health Michigan and Trinity Health of New England websites.

Mike Slubowski, Trinity Health president and chief executive, called the campaign “a direct reflection of our brand promise.” He

G’DAY TO THE USA

added: “Not only does it share the Trinity Health patient experience story, but it also shares the Trinity Health staff and colleague story. The campaign’s message is core to who we are at Trinity Health and represents how our collective expertise and culture work together to act as a transforming healing presence within our communities.”

Trinity Health is based in Livonia, Michigan, and operates in 26 states. The system has 123,000 colleagues. Its facilities include 88 hospitals and 135 continuing care sites.

Monday 28 - Wednesday 30 August 2023 The Westin Hotel, Perth, Western Australia Register now for Catholic Health Australia’s national conference Join us and 300 board directors, CEOs, and senior executives from Catholic Health Australia’s hospital, aged and community care providers for the National Conference to be held in the beautiful Western Australia city of Perth. For more details go to cha.org.au/events or email secretariat@cha.org.au

SoutheastHEALTH has this flagship campus in Cape Girardeau, Missouri. Mercy of Chesterfield, Missouri, is in talks to acquire SoutheastHEALTH.

March 1, 2023 CATHOLIC HEALTH WORLD 5

PATHWAYS PILOT PARTNER ORGANIZATIONS AND THEIR ROLES

CommonSpirit Health has been partnering with the Pathways Community HUB Institute to launch care coordination networks in some of the health system’s service areas. All the networks are slightly different but all generally contain nonprofit organizations that work together to meet the needs of specific vulnerable populations.

In the Omaha, Nebraska, market, these are the organizations involved in the network, and the roles each plays:

ORGANIZATION

Pathways Community HUB Institute

ROLE IN THE NETWORK

Technical support and founder of model

Omaha Community Foundation Hub

CommonSpirit Health’s CHI Health Funder and health system

Healthy Blue

Funder and health plan

Nebraska Total Care Funder and health plan

United HealthCare Community Plan of Nebraska Funder and health plan

Medica Health plan

Nebraska Medicine Health system

Children's Hospital and Medical Center Hospital

Methodist Health System Hospital

Charles Drew Health Center

Community health center

One World Community Health Center Community health center

The Wellbeing Partners Community-based organization

United Way of the Midlands

CyncHealth

Community-based organization

Host of technology platform

hub organizations have been growing the client base and network as they prove to their existing and prospective partners the validity of the approach. The networks have shown that they have been very effective in connecting clients to services, improving their health outcomes, stabilizing their socioeconomic circumstances and improving how they access care.

Brian Li, CommonSpirit system director of community health strategic initiatives, notes that Pathways network partners get access to the data the community health workers put into the database. He says that data is extremely valuable to CommonSpirit — it reveals which social service and medical needs are most difficult to meet in its communities. This intelligence can illuminate gaps in community services that CommonSpirit can address through programming and investment.

The institute’s 21 pathways

The Pathways Community HUB Institute model involves community health workers assessing and addressing social determinants of health and other needs. At the outset of a relationship with a client the community health worker fills out an intake form that identifies the client’s unmet needs.

The assessments will help the community health worker determine which of 21 different pathways to take in guiding the client to resolving the concerns.

The 21 standard pathways are:

Adult education

Developmental referral, for when a client’s child may have developmental delays

Employment

Family planning

Care navigation networks

From page 1

Douglas County Health Department Partner meet their clients’ needs.

Ji Im is senior director of community and population health at CommonSpirit, which has 140 hospitals and 1,000-plus additional care sites in 21 states. She says, “This is a community care model, not a hospital program. This Pathways program is owned by and sits in the community. We are a community partner in this. And this is a significant shift” from approaches in which hospitals lead such efforts.

The Pathways work is an offshoot of CommonSpirit’s ongoing efforts around what it calls Community Connected Networks. These networks link clinical care providers and social service organizations within a referral system and technology platform to address people’s needs.

Hub and spoke

Im says CommonSpirit became aware of Pathways Community HUB Institute as it was seeking to enhance community-based care coordination programs it had established in some of its markets.

The institute has developed a hub-andspoke model that has a community organization at the center of a network of agencies in a particular locality. Two or more agencies in the network hire community health workers to engage and coach people in addressing their pressing health and social service needs.

Also involved in these collaborations are organizations that have an interest in or a direct hand in meeting the needs of the program’s clients. Those partnering organizations can include health systems, federally qualified health centers, managed care organizations, government entities and social service providers. The partners fund the work with grants, philanthropy and payments from some insurers.

The institute helps train and certify the organization at the hub of the model and the community health workers.

The community health workers guide clients in the completion of pathways, or specific steps toward resolving particular health and social service concerns (see sidebar). The workers do this by connecting the clients with organizations that can address their needs. The community health workers track and document clients’ progress along the pathways in a database.

with the Pathways Community HUB Institute around 2020, it committed $1 million to the work the institute would need to do to support communities in CommonSpirit service areas as they implemented the model. That $1 million investment spurred an additional $3 million in investments from other funders that helped pay for startup infrastructure.

About two years ago, CommonSpirit hosted an informational session on the model with all its markets and invited those that wished to pilot the institute’s model to do so. The six markets that were ready to move forward were Omaha, Nebraska; Brazos County, Texas; King County and Pierce County, Washington; San Joaquin, California; Clark County, Nevada; and Maricopa County, Arizona.

Some have moved from the pilot phase to full commitment to the model. CommonSpirit intends to expand it to more of its markets.

Catalyst

Im says because all the CommonSpirit service areas differ in terms of their assets, resources, needs and shortcomings, each has been proceeding at its own pace and each looks a little different in its implementation of the Pathways model. “Every community is a snowflake,” Im says.

But in all six markets, CommonSpirit and its hospitals are functioning as catalyst, connector, collaborator and informal consultant in building out the hub-and-spoke network.

Im says the hub organizations have been starting small, with client populations identified as among the most vulnerable. The

Community bank

In some cases managed care organizations are involved in and support the networks and pay for the services their members receive from the community health workers. However, in many cases, there is no reimbursement source. So, the care navigation networks rely on a “community bank” approach, says Im.

Organizations in the networks put money into a community bank. The money can cover the Pathways hub organization’s operating costs, including infrastructure and community health worker services.

For instance, the care navigation network in Omaha is addressing the needs of pregnant women at risk of poor birth outcomes. CommonSpirit and three managed care organizations — United HealthCare Community Plan of Nebraska, Healthy Blue Nebraska and Nebraska Total Care — each have contributed funds to the network’s community bank. Those funds are going toward the hub’s operations and toward reimbursing for the community health workers’ services to navigate clients to any additional services from other organizations, such as prenatal services from a health care provider.

In markets that have advanced beyond the pilot stage, some of the capital pays bonuses that the community health workers earn when their client completes a pathway. The amount of the bonus varies by market.

Im says CommonSpirit is early in the Pathways work. The partners are finding that when it comes to addressing the social determinants of health and health inequities, efforts are “most effective when they are owned by and centered in the community.”

Food security

Health coverage

Housing

Immunization referral

Learning

Medical home

Medical referral

Medical adherence

Medical reconciliation, for when there is a need for medical providers and/or pharmacists to evaluate a client’s prescribed medications

Medical screening

Mental health

Oral health

Postpartum

Pregnancy

Social service referral

Substance use

Transportation

Whole-person approach

Julie Tousa is a social worker and the Pathways Agency program manager at CommonSpirit’s Dignity Health St. Rose Dominican in the Las Vegas area. In Clark County that CommonSpirit hospital is the Pathways Agency and St. Rose Dominican employs the network’s four community health workers. A Pathways Agency is a single organization that has adopted the model.

The Nevada Ryan White Program that serves people with HIV and the hospital’s R.E.D. Rose Program that promotes breast cancer screening and provides diagnostic services at no cost to uninsured women are primary funders of the network. The community health workers follow up on referrals from partner organizations and invite people with HIV or cancer and low-income pregnant women to join the Pathways program.

The community health workers are bilingual in English and Spanish and have deep roots in the community. They build trust and offer support to clients working toward goals set out in pathways.

According to data from Tousa, the community health workers in Nevada aided 73 clients in 2022. That included closing 260 pathways. As a sampling, 10 of those were housing pathways, 24 were medical pathways, and 24 were food security pathways.

Tousa says the reason Pathways succeeds where other programs may fail in addressing social determinants is in large part that Pathways “takes a whole-person care approach.

“This allows us to look at the person and their family and all their risks. And we follow up (on solutions). And because of the trust that the community health workers build with the clients, the clients are more willing to engage.”

jminda@chausa.org

signed

Pilots When CommonSpirit first

on

Im

CommonSpirit Health’s Dignity Health St. Rose Dominican in the Las Vegas area is part of a group of community organizations that is collaborating to provide community health worker support to people in vulnerable populations. Here, community health worker Maria Ambriz, left, meets with client Roxana Henriquez to complete a risk assessment.

Li

6 CATHOLIC HEALTH WORLD March 1, 2023

Tousa

KEEPING UP

PRESIDENTS AND CEOS

St. Louis-based Ascension has made these changes: Polly Davenport to senior vice president, Ascension, and ministry market executive for Ascension Illinois, from interim ministry market executive. Carol Schmidt to senior vice president, Ascension, and ministry market executive, Ascension Michigan. Schmidt was senior vice president, Ascension, and chief operating officer for Ascension Medical Group and Ascension’s clinical initiatives.

Facilities within CommonSpirit Health’s CHI Saint Joseph Health in Kentucky have made these changes: John Yanes to president of Saint Joseph Mount Sterling in Mount Sterling. He will continue as president of Saint Joseph London in London and Saint

Joseph Berea in Berea. At Mount Sterling, Yanes replaces Jennifer Nolan, who has accepted a position with CHI Saint Joseph Health, in addition to her role as president at Flaget Memorial Hospital in Flaget. In addition to Yanes, the leadership team for the Mount Sterling, London and Berea facilities will include Dr. Shelley Stanko, chief medical officer; Andrea Holecek, vice president of nursing; and Brady Dale, vice president of operations.

Theresa Guenther to chief executive of Avera Creighton Hospital in Creighton, Nebraska, from interim chief executive.

ADMINISTRATIVE CHANGES

Joseph Mazzawi to vice president of mission of Bon Secours St. Francis in Green-

ville, South Carolina. Dave Rigsby to executive director for Peace Harbor Medical Center Foundation of Florence, Oregon.

GRANTS

Saint Francis Hospital of Wilmington, Delaware, part of Trinity Health, has received a $1 million grant from Highmark Blue Cross Blue Shield Delaware’s BluePrints for the Community program. Saint Francis will use the funding to support The Healthy Village at Saint Francis Hospital. The Healthy Village is a model of care that aims to address social determinants of health. Saint Francis said in a release that it is among the first in the nation to apply the Healthy Village concepts. According to information from the World

Health Organization, Healthy Village concepts have evolved organically around the world and have to do with improving quality of life and enriching the vitality of neighborhoods while protecting their heritages, histories and residents by working with community-based partners whose services address the drivers of health.

Trinity Health’s St. Mary Medical Center in Langhorne, Pennsylvania, has received a $1 million gift from the Bristol Myers Squibb Foundation to support major equipment and software upgrades to the cardiac catheterization labs in the St. Mary Heart and Vascular Center. This gift is the single largest corporate donation to date to St. Mary Medical Center’s Heart and Vascular Center campaign, according to a press release on the gift.

CHA VICE PRESIDENT, SPONSORSHIP AND MISSION SERVICES

The Catholic Health Association seeks candidates for the position of vice president, sponsorship and mission services.

The Catholic health ministry is the largest group of nonprofit health care providers in the nation. It is comprised of more than 600 hospitals and 1,600 long-term care and other health facilities. To ensure vital sponsorship and a vibrant future for the Catholic health ministry, CHA advocates with Congress, the administration, federal agencies, and influential policy organizations to ensure that the nation’s health systems provide quality and affordable care across the continuum of health care delivery.

CHA’s vice president of sponsorship and mission services plays a leadership role within the organization. The position reports directly to CHA’s president and chief executive officer and the vice president is a member of the president’s advisory council and senior management. This executive will be responsible for providing leadership and strategic vision in the design, development, implementation, evaluation and coordination of programs and services that advance CHA members’ Catholic identity and promote a vision and understanding of the Catholic health ministry as an essential ministry of the church.

The vice president will be responsible for the coordination of the association’s member services involving mission integration, theology and ethics, ministry formation and sponsorship. This executive will ensure CHA services in these areas enhance member value and align with CHA’s strategic plan. Duties include serving as a CHA spokesperson on sponsorship and mission issues in conjunction with the association’s president and chief executive officer and maintaining effective relationships with CHA members and leaders in other national organizations. Travel is required.

CHA seeks candidates who are practicing Catholics with a minimum of 12 years’ experience in a Roman Catholic ministry. The successful candidate will have broad knowledge of religious and lay sponsorship models and Catholic moral and social traditions and a working knowledge of health care and health system management. Candidates should have a minimum of 5 years’ experience in management including supervision of staff.

This position requires a master’s degree or Ph.D. in Roman Catholic theology or equivalent work experience.

Interested parties should direct resumes to:

Cara Brouder Sr. Director, Human Resources Catholic Health Association cbrouder@chausa.org

Further inquiries: 314-253-3498

To view a more detailed posting for this position, visit the careers page on chausa.org.

For consideration, please email your resume to HR@chausa.org

Davenport Schmidt Yanes

Holecek Stanko Dale

Join us for Assembly 2023 chausa.org/assembly

TOCONNE C T JUNE 12—13 | VIRTUAL March 1, 2022 CATHOLIC HEALTH WORLD 7 March 1, 2023

A TI ME

Group prenatal program teaches women to be strong self-advocates in maternal care

By LISA EISENHAUER

When she was expecting her first child eight years ago, Rebecca Bernadel remembers feeling like she was just following orders from her care providers.

“It was like, you do this, you do this, you do this,” says Bernadel, who is expecting her second child in August with her boyfriend and first-time father-to-be Jabarri Johnson. “This experience, I really wanted to be in tune with how I can advocate for myself, and Jabarri can advocate for me and the baby, and all of our options.”

That’s why Bernadel and Johnson accepted the invitation of their midwife to try the CenteringPregnancy care model that Mercy Medical Center in Baltimore started last year. In the care model, women at or near the same stage of pregnancy attend prenatal visits with their providers that extend into group learning sessions. The providers encourage the expectant mothers to develop supportive relationships with each other.

“We really wanted to be fully educated on our experience but also have that support from a midwife and from other women in the group,” Bernadel explains.

Even though they are early in the program, Johnson says he is already excited about its patient-centered approach and the education it is providing on topics like nutrition during pregnancy, exhaustion, breastfeeding, mindfulness and mental health.

“When you want the example of how people of color want health care, I think this is a prime example when it comes to maternal health care,” Johnson says. “I wish everybody could have that experience.”

Rebecca Bernadel and her partner, Jabarri Johnson, are taking part in CenteringPregnancy at Mercy Medical Center. Their child is due in August. Bernadel says they both want to be educated on how to advocate for the best maternal care and on their care options.

Attuned to disparities

The couple’s midwife, Kia Hollis, wants all of Mercy’s maternity patients to have the opportunity to feel similarly seen and empowered. Hollis is the director of Mercy’s CenteringPregnancy program.

She says the hospital and its Metropolitan OB/GYN provider group was motivated to start CenteringPregnancy by research that shows the care model gets high marks from participants and improves outcomes for mothers and newborns, especially for Black patients.

Mercy serves a largely African American population in the heart of Baltimore, a city whose poverty rate of 20% exceeds the national average of about 11.6%. It is one of the city’s main maternity hospitals. Last year, 2,600 babies were born there.

Hollis says she and her colleagues are attuned to the dismal statistics on maternal outcomes for women of color compared to white women. She notes that those racerelated disparities appear across income and education levels.

“We are trying to educate women about their bodies so that they know what warn-

ing signs and symptoms to look out for so that they can be a stronger advocate for themselves when they actually present to care,” Hollis says. “Through this program, we hope to decrease those poor health outcomes.”

Racial maternal disparities include a pregnancy-related mortality rate for Black and Hispanic women that is up to three times higher than that of white women and higher rates of preterm births, low birth weights, and births in which women received late or no prenatal care, the Kaiser Family Foundation says.

The nonprofit Centering Healthcare Institute created and oversees CenteringPregnancy practices at more than 400 sites in 44 states. The institute cites data that suggests its model counters racial disparities.

For example, a study published in May 2012 in the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology compared the birth outcomes of women in group prenatal care to those who got traditional prenatal care. One of its findings was “the racial/ethnic disparity in rates of preterm birth seemed to diminish for the women who participated in group care.”

Group sessions, group support CenteringPregnancy follows the schedule of 10 prenatal visits recommended by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists — monthly appointments in the early weeks of pregnancy and twice a month from week 28 through delivery. Its sessions are 90 minutes to two hours long. During the first part, the mothers-to-be meet with their providers for health assessments. For the rest of the session, they take part in educational group discussions.

Mercy started its CenteringPregnancy program in October. Through February, seven cohorts were underway with five to

eight participants in each; most participants are expectant mothers but a few of them are partners like Johnson. Each cohort started at different times with women in their 12th to 16th week of pregnancy. The women are referred to the program by Metropolitan OB/GYN providers. Participation is optional.

Hollis is leading three of the cohorts. She conducts the 10 interactive group discussions that focus on different topics each session. The first one covers the typical discomforts of pregnancy, prenatal testing, what drugs are safe to use while pregnant and what drugs aren’t. The second delves into nutrition and includes a healthy cooking demonstration. Participants are offered free produce delivery from a Mercy partner called Hungry Harvest, a benefit that’s available through their 36th week.

That’s just one of the wraparound services participants are offered. Another is free Uber service to and from the sessions. They also can get referrals to agencies that address other needs such as child care and mental health.

Empowerment, connection

Christina Albo is the adviser from the Centering Healthcare Institute who is working with Mercy to develop its CenteringPregnancy model. She says the model’s success requires a systemic shift within organizations away from a one-onone model to the group care model.

Albo helps organizations set up the steering committees for CenteringPregnancy, figure out billing and medical coding and plan how to recruit and retain patients.

“For the sites that engage in the Centering implementation plan, we meet on a regular basis and I provide that advisory kind of perspective, answering any questions that they might have,” she says. “I’ll also work with anybody within their system that needs a little extra orientation or practice around what the model of care is.”

The benefits of CenteringPregnancy’s evidence-based model are vast, Albo says. In addition to having regular access to their care providers, the participants discuss issues like what it means to be safe and healthy during pregnancy and how to a speak up for themselves with care providers. They also get a chance to develop a network of support with other expectant mothers from their community.

“People come out of it feeling empowered, connected, and with improved health outcomes,” Albo says.

She sees the social aspect of CenteringPregnancy as particularly important as Americans emerge from the long period of isolation brought on by the pandemic. “I think we’re in a unique moment where building connection and community just feels kind of supremely important,” Albo says. “I think that the Centering model really offers that in spades.”

‘I found somebody’

Quira Carver participated in Mercy’s CenteringPregnancy program before she gave birth in January. She says she valued the group interaction, especially as a firsttime mom.

“It was very important because a lot of people are going through the same emotions or the same problems,” she says. “It helped you understand that you’re not the only person going through things or feeling a certain type of way during your pregnancy.”

Carver’s daughter, Cailey, arrived a little underweight but otherwise healthy.

Hollis says getting expectant months to join the CenteringPregnancy program isn’t easy, perhaps because the sessions are about two hours long or because the groups meet during traditional working hours. However, the retention rate for women who have attended a session is about 90%.

She recalls one patient who didn’t have much in the way of a personal support system and seemed to be growing increasingly depressed about going it alone. Hollis persuaded her to join the CenteringPregnancy program even though she was well into her pregnancy.

At the last CenteringPregnancy group meeting the patient attended, she and another expectant mother clicked. Hollis remembers the joy it brought the

woman.

leisenhauer@chausa.org

young

“She was like, ‘Miss Kia, I found somebody that I can go to and we’re planning on doing walks together when we both have our babies and we’re just, you know, trying to be there for each other,’” Hollis says.

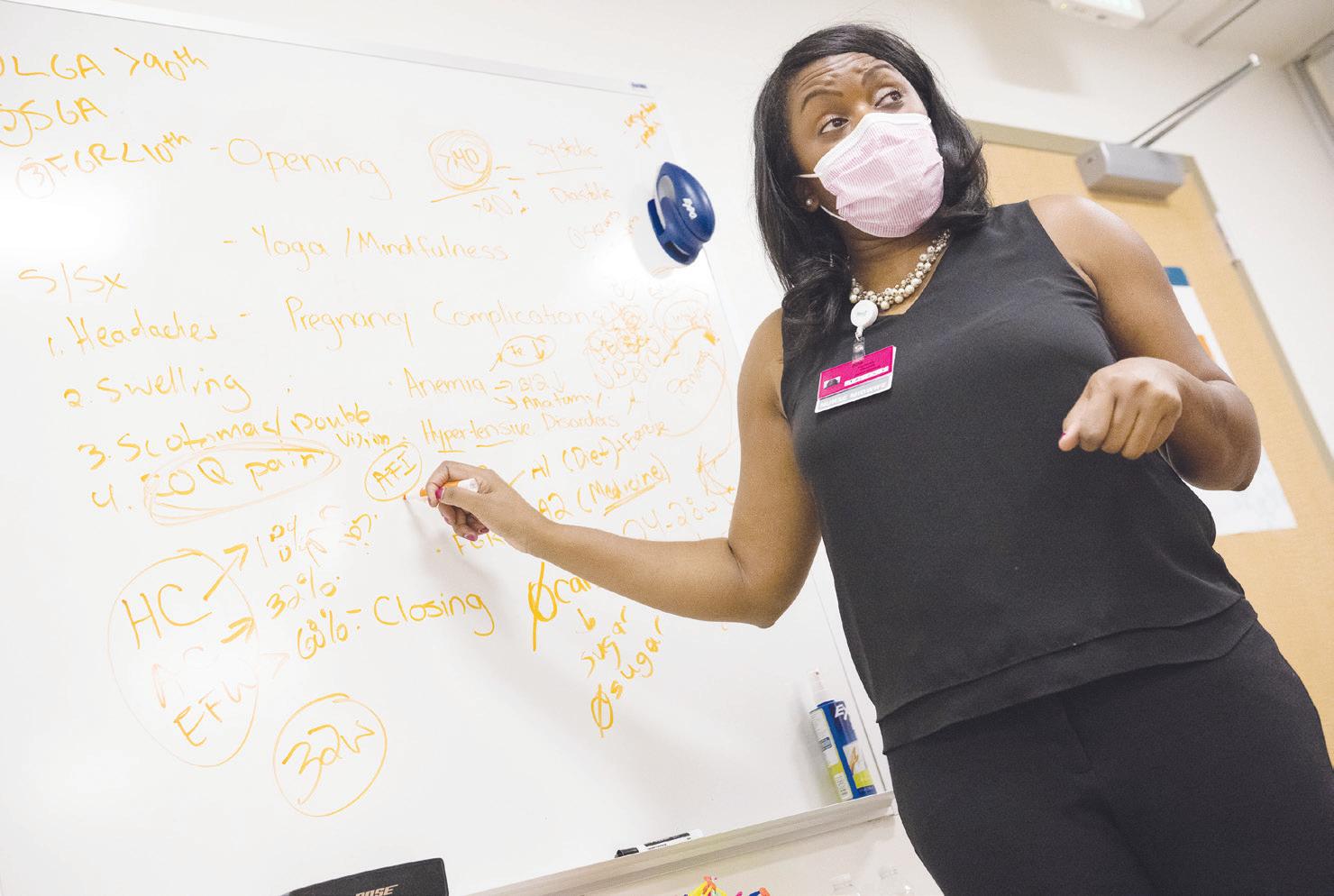

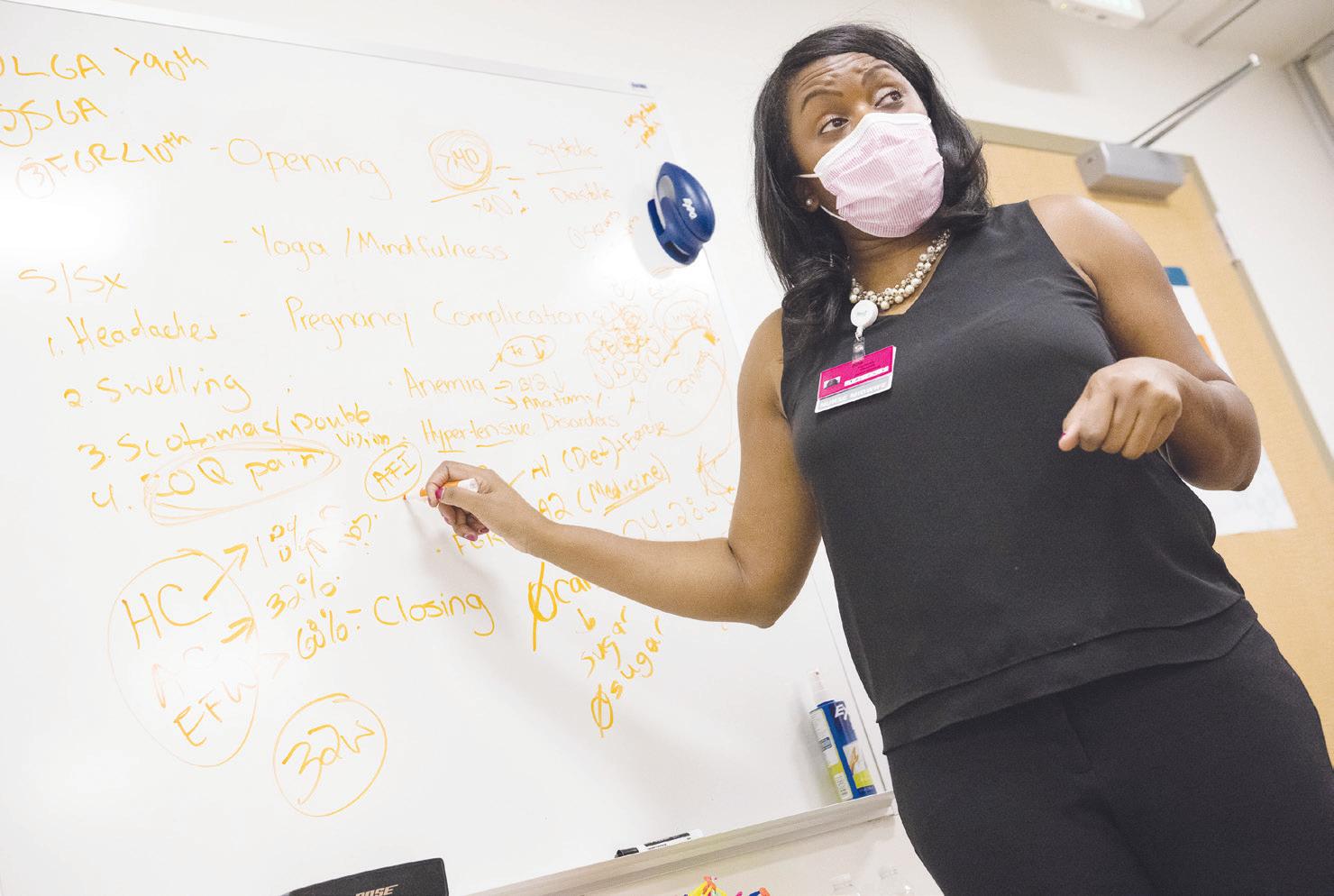

Kia Hollis, director of CenteringPregnancy at Mercy Medical Center in Baltimore, leads a discussion with a group of expectant mothers about pregnancy complications, such as anemia, allergies and gestational diabetes. The CenteringPregnancy model is used at more than 400 sites across the country.

Quira Carver was in a CenteringPregnancy cohort at Mercy Medical Center before the birth of her daughter, Cailey, in January. She says the program helps women understand that they aren’t alone in what they are experiencing.

Keimyra Pumphrey practices mindfulness and prenatal yoga at a CenteringPregnancy session at Mercy Medical Center. Each of the cohorts has five to eight participants. The partners of the women are welcome, too.

Jnai Player struggles to drink the beverage that must be consumed in between blood draws to test for gestational diabetes. The glucose test was part of her prenatal care in Mercy Medical Center's CenteringPregnancy program.

Albo

Jennifer McMenamin

Jennifer McMenamin

8 CATHOLIC HEALTH WORLD March 1, 2023

Jennifer McMenamin

By JULIE MINDA

By JULIE MINDA