Preserving long-term care ministries 4 Executive changes 7

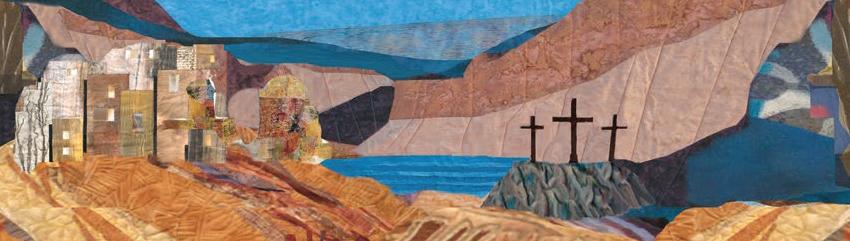

Allison Q. Salopeck, president and chief executive of the Jennings eldercare organization, visits with Sr. Margaret Mary Grochowski at her jubilee. The last surviving member of the Sisters of the Holy Spirit congregation, Sr. Grochowski died Nov. 7, 2021. The congregation moved to a lay sponsor ship model for Jennings in 2020.

Congregations encouraged to act to ensure eldercare ministries endure

By JULIE MINDA

Founding congregations of large Cath olic hospital systems in the U.S. began methodically grappling decades ago with how best to preserve their ministries and charisms as their congregational ranks decreased.

Many congregations chose to create a new sponsorship structure — a ministe rial juridic person — to allow for continu ity of their ministries and charisms under the sponsorship of lay leaders. They cre ated formation programs to instill in lay

Continued on

CHI Health prioritizes mental health needs of rural youth

Funding supports school, community efforts to strengthen families, address trauma

By JULIE MINDA

The prevalence of mental illness is about the same in rural populations as it is in urban populations, but there is far less access to mental health services in rural areas.

CHI Health has been working with local partners to identify the mental health issues affecting rural communities in its service areas and helping to set up and fund pro gramming to address unmet needs. A top focus is the mental health of youth.

CommonSpirit Health, CHI Health’s parent system, has made grants to fund a wide variety of community-based mental health interventions. The programming includes providing consultation and train ing on mental health to teachers and other school staff, offering mental health first aid training in schools, building mental health referral networks, establishing wellness centers that include mental health services, and providing technology to connect teach ers and students which has been shown to lead to greater student engagement and

Ethicists see need for clinical training for next generation

By LISA EISENHAUER

The immersive experience Amanda Altobell got in Catholic health care ethics, mission and spiritual care through a virtual internship fol lowed by an in-person fellowship within Bon Sec ours Mercy Health provided a vital link between her academic studies and her career.

She completed the semester-long online internship last fall as part of her work toward a PhD with an emphasis on Catholic health care ethics that she’s close to finishing at Duquesne

Continued on 2

Providence-supported academy readies community health workers for clinical settings

By LISA EISENHAUER

Jessica Verdugo credits the training and experience she got from the Community Health Worker Academy with opening her eyes to how seemingly minor barriers can keep people from accessing needed health care and to the many ways she can guide patients past them.

“I didn’t think that something as little as helping people make a phone call or helping them schedule an appointment would make a difference for them,” says Verdugo, who graduated in February from the academy which is based at Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science in Los Angeles. She was one of 13 students in the certificate program’s second class.

Since then, she’s been working full time at clinics affiliated with Torrance Memorial Medical Center in the south Los Angeles suburb of Carson. The medical

Throughout Catholic health care, ethics and spiritual care openings are going wanting for lack of qualified candidates. Interns and fellows who gain experience in clinical settings to complement their academic training are better prepared for professions where they will lead complex, often high-stakes discussions with patients and administrators.

Blessed be the pets

Several hospitals across the ministry celebrated the Oct. 4 Feast of St. Francis of Assisi by hosting blessings for pets events in early October. Here, Scout sits pretty to receive his blessing from Fr. Sam Maranto at Our Lady of the Lake Regional Medical Center in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. Stephanie Manson, center, Scout’s companion and the hospital’s chief operating officer, looks on.

3

Micaela Reyes, a senior community health worker, hands a list of community resources and some new clothing to a patient in the emergency department at Providence Little Company of Mary Medical Center in Torrance, California. Reyes assists patients who are experi encing homelessness in finding shelter and supportive services.

Micaela Reyes, a senior community health worker, hands a list of community resources and some new clothing to a patient in the emergency department at Providence Little Company of Mary Medical Center in Torrance, California. Reyes assists patients who are experi encing homelessness in finding shelter and supportive services.

Continued on 5

4

Continued

on 6

Lori Henrichs, center, a parent educator with Southwestern Community College, takes part in a Parents As Teachers home visit with a Corning, Iowa, mother and daughter. CHI Health provides funding to sup port the Parents As Teachers program.

Story PAGE

Altobell

NOVEMBER 1, 2022 VOLUME 38, NUMBER 17 PERIODICAL RATE PUBLICATION

Pandemic, abortion ruling bring ethical issues to forefront

Just as the COVID-19 pandemic height ened awareness of the function of health care ethicists, the Supreme Court ruling that pushed decisions on the legality of abortion back to the states has the poten tial to do the same, some Catholic health care ethicists say.

Nate Hibner, a senior ethics director at CHA, believes both the pandemic and the Dobbs abortion ruling have shaken up the health sector and made the role of those trained to lead ethical discussions more apparent and vital.

“When we get these kind of disruptors, people start to say, ‘Do we continue to do the things we’ve always done or do we have to do something differently?’” Hibner says. “That kind of ambiguity, that gray ness, is where we ethicists thrive.”

The University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing says it found in a study that clinical ethicists have “played an expanded role during the pandemic, supporting hospital operations across the country.” The topics the ethicists have been asked to advise leadership teams on have included end-of-life care, resource scarcity and care decisions for incapacitated patients without health care advocates.

Becket Gremmels, vice president of theology and ethics at CommonSpirit Health, says he thinks the pandemic has brought to the forefront the skills in leading complex and sensitive discussions that ethicists bring to the table.

Training next-gen ethicists

From page 1

University in Pittsburgh. The online curri cula included rounding with clinicians and joining ethics consultations involving doc tors, patients and families.

The fellowship was at Bon Secours hospitals in Richmond, Virginia, where she spent six months training under the mentorship of senior ethics leaders. She got exposure to discussions and decisions around ethical and spiritual challenges that arise in intensive care, palliative care and other units. By the end, Altobell was leading ethics consultations.

This summer, Altobell was hired on as director of mission at Bon Secours South side Medical Center in Petersburg, Virginia, and Bon Secours Southern Virginia Medical Center in Emporia, Virginia. She is also lead ethics consultant for those hospitals and collaborates with another consultant at five other Bon Secours hospitals in Richmond.

“I would say I was very fortunate that through Bon Secours Mercy Health I was able to really get the experience I needed to be well versed and trained and be able to provide guidance for the clinical team and launch my career,” Altobell says. “I would not be where I am now without it.”

Scarce opportunities

Throughout Catholic health care, lead ership and mid-level mission, ethics and spiritual care openings are going wanting. An onslaught of retirements has added to the strain. For years, it’s been hard to fill vacancies because of a dearth of candidates.

In 2021, CHA set up an online Career Center and has promoted it with commu nications across the ministry. The cen ter created a space within the ministry to link employers and qualified applicants for some of the harder-to-fill posts. In mid-October, a majority of the 23 positions listed on the job board included ethics, mis

During the pandemic, Gremmels says ethicists have been asked to weigh in on urgent issues in which various stakehold ers had competing interests, such as how to equitably distribute the early and scarce supply of COVID vaccines.

“I found that ethicists being involved in those discussions has been very helpful for our leaders,” Gremmels says. “We had at least a framework to go with when they were ready to start thinking through those questions.”

Jason Eberl is a professor of health care ethics and philosophy and director of the Albert Gnaegi Center for Health Care Ethics at Saint Louis University. Early in the pandemic, he helped survey hospitals across the nation on their ventilator triage policies to ensure that best practices and fairness were observed in the treatment of COVID patients, including in the event that resources had to be rationed. One of the survey’s findings, Eberl says, was that about half the hospitals did not have a policy.

Some Catholic hospitals called on Eberl and other faculty from the Gnaegi Center to help establish those policies, he says. It was just one example of how they have been tapped by health systems to offer guidance amid the thorny issues raised by the health care emergency.

Michael McCarthy is associate profes sor and director for the graduate program in health care mission leadership at the Neiswanger Institute for Bioethics and Healthcare Leadership at Loyola University Chicago. He says he thinks ethicists were brought into more meetings when critical

decisions were being made during the pan demic than before the health crisis began and that their participation led to more open conversations.

McCarthy is hopeful that Catholic health care ethicists will be invited to play similar roles in framing and clarifying ethical, theo logical and medical issues that are arising around the Supreme Court’s ruling on abortion in the Dobbs v. Jackson case. The decision struck down a national protection for abortion access and left the issue up to individual states to decide.

Dr. Kelly Stuart, vice president of ethics for Bon Secours Mercy Health, points out that states’ reaction to the Dobbs ruling has been political. Stuart moved to ethics from neonatology.

Some states, she says, are legislating policies that fail to reflect medical stan dards of care and that are more proscrip tive than what is prohibited for Catholic health care providers established in the Ethical and Religious Directives for Catholic Health Care Services by the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops. That policy defines abortion as “the directly intended termination of pregnancy before viability or the directly intended destruc tion of a viable fetus.”

“I think part of ethicists’ role, especially around the Dobbs decision, is helping clearer heads to prevail so that we can think about what is good policy — one that acknowledges the medical vulnerability of both mother and baby and seeks to protect both,” Stuart says.

— LISA EISENHAUER

openings for ethics and mission leaders as “teeny.” The system’s own fellowships have proven to be a primary source for new hires.

“We have kept the vast majority of the people we’ve trained,” she says. “They’ve gotten very good jobs in our health system and really been assets to the system.”

Stuart says Bon Secours Mercy Health uses a model for its on-site training that is tailored to its own structure and might not suit those of other systems. She points out, for example, that since the system has few positions that deal only with ethics, the fellows also are immersed in mission and spiritual care work.

The fellowship program goes back years and is open to applicants with advanced education in ethics or extensive clinical experience. The health system’s virtual internship started last year and is a col laboration restricted to graduate students at Duquesne University’s Center for Global Health Ethics.

Jessica Weingartner, director of mission for Bon Secours’ Greenville, South Caro lina, market, says the online experience was borne from necessity during the pandemic. When clinical sites cut off in-person train ing because of the contagion, Weingartner and Alex Garvey set up the internship. Gar vey, who received his PhD in health care ethics from Duquesne, was vice president of mission in Bon Secours’ Greenville mar ket at the time.

The Greenville market is now host to its third Duquesne intern and plans to con tinue the semester-long program. The interns participate virtually in ethics edu cation, ethics committee meetings, ethics consults and other real-time events from 500 miles away.

Weingartner considers the experience gained through internships and fellowships like those at Bon Secours Mercy Health to be a critically important complement to the academic training of health care ethicists.

“One of the interns that I had said ‘I think about some of these things completely dif ferently now, seeing it in the context of actual patients in the actual hospital rather

Catholic Health World (ISSN 87564068) is published semimonthly, except monthly in January, April, July and October and copyrighted © by the Catholic Health Association of the United States. POSTMASTER: Address all subscription orders, inquiries, address changes, etc., to CHA Service Center, 4455 Woodson Road, St. Louis, MO 63134-3797; phone: 800-230-7823; email: servicecenter@chausa.org. Periodicals postage rate is paid at St. Louis and additional mailing offices. Annual subscription rates: CHA members free, others $29 and foreign $29.

sion or pastoral care in the descriptions; several of the jobs were director-level or executive posts. Many of them listed expe rience within Catholic health care as an essential qualification.

Internships and fellowships like those Altobell took advantage of to gain that criti cal experience remain scarce. There is no central repository for those opportunities; only a few health systems appear to offer them.

Brian Kane, a senior ethics director at CHA, says experience in clinical settings is a key part of the training ethi cists and mission leaders need in their roles as facili tators of complex discus sions that delve into medical science, law, public health, financial sustainability and more. The discussions may involve hospital executives, clinicians, patients, families and communities.

Kane says ethics consultants must be ready to “lead structured conver sations around questions that others might not have considered and also to

make them aware of the limits of their decision-making.” As an example, he points out that sometimes people who think they have agency to make choices such as around end-of-life decisions do not, and ethicists have to help explain the complexi ties involved.

Shortly before the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted many health care training pro grams, CHA issued a call across the Catholic health ministry for the creation of more eth ics and mission fellowships. The call came at the behest of members who reported on how challenging it was to recruit qualified candidates for ethics and mission positions.

It’s unclear how many systems took up the call. Providence St. Joseph Health, for one, reports that it is developing an ethics fellowship. Trinity Health offers a mission integration fellowship that covers “leader ship and Catholic identity, formation, eth ics, and spiritual care ethics training.”

Grow your own

At Bon Secours Mercy Health, Vice Pres ident of Ethics Dr. Kelly Stuart describes the pool of qualified candidates for her system’s

Opinions, quotes and views appearing in Catholic Health World do not necessarily reflect those of CHA and do not represent an endorsement by CHA. Acceptance of advertising for publication does not constitute approval or endorse ment by the publication or CHA. All advertising is subject to review before acceptance.

Vice President Communications and Marketing Brian P. Reardon

Editor Judith VandeWater jvandewater@chausa.org 314-253-3410

Associate Editor Julie Minda jminda@chausa.org 314-253-3412

Associate Editor Lisa Eisenhauer leisenhauer@chausa.org 314-253-3437

Graphic Design Norma Klingsick Advertising ads@chausa.org 314-253-3477

© Catholic Health Association of the United States, Nov. 1, 2022

Michael McCarthy, Esther Berkowitz, center, and Lena Hatchett, who are all affiliated with Neiswanger Institute for Bioethics and Healthcare Leadership at Loyola University Chicago, participate in a simulated ethical consultation. The simulation is part of a tool called Assessing Clinical Ethics Skills that uses case studies to put students into virtual situations closely based on those that take place in clinical settings.

Hibner

Gremmels

Eberl

Stuart

Kane

McCarthy

2 CATHOLIC HEALTH WORLD November 1, 2022

than just thinking about it theoretically, which is totally different,’” Weingartner says.

She was a graduate assistant in ethics at Ascension and a mission fellow with Bon Secours before she moved into the mission director position.

Pipeline proposal

Becket Gremmels is vice president of theology and ethics at CommonSpirit Health and among those recognized in 2018 as one of CHA’s Tomorrow’s Lead ers. He had a fellowship at an Ascension hospital as he pursued his PhD in health care ethics. He went from that experience into director of ethics posts with Ascension before moving on to CHRISTUS Health and then to CommonSpirit.

Gremmels says that he got a solid grounding in Catholic theology and ethics from his higher education at the University of Notre Dame and Saint Louis University. However, he says his on-site clinical experi ences were what prepared him for his dayto-day ethics work.

“I think the biggest benefit that grad school teaches you for this field is how to learn, because I’d say what I use on a daily basis, 90% of it, I learned in the field after I finished classes,” he explains.

CommonSpirit is among the Catholic systems that offer ethics internships. Its one-year program gives students system wide training and practical experience in resolving ethical challenges. The program, which is remote and unpaid, has five stu dents in its current cohort. CommonSpirit has a relationship with several universi ties that allow the interns to receive course credit for their work.

Gremmels is part of what he calls a loose-knit “coalition of the willing” who

CHA, members collaborated to meet need for mission and ethics leaders

Almost a decade ago, CHA members surfaced concerns about a shortage of qualified applicants for high-level mission and ethics openings, especially given a number of impending retirements.

In response, CHA collaborated with its members to establish a multistep pro cess to assess the scope of the shortage and identify the competencies needed in entry-level, middle management and leadership positions.

The first step was an initiative named Project Legacy. Nate Hibner, a senior director of ethics at CHA, says it was focused on data collection and framed as a call to action to create a pipeline of tal ent for ethics, mission and pastoral care positions.

It was followed up by Faithfully For ward, an initiative that CHA launched in 2019. “This is the stage where we created resources and implemented strategies,” Hibner explains.

favor designating a professional association to accredit clinical ethics fellowships that provide advanced on-site training for min istry and secular posts. Once that happens, the coalition hopes to persuade the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services to fund the fellowships, just as the federal agency does for other health professionals such as chaplains and pharmacists.

Gremmels has drafted a proposal to create a pipeline of Catholic health care

As part of Faithfully Forward, CHA worked with members to produce a bro chure that sets out the qualifications and competencies for ethicists in Catholic health care, such as knowledge of the Catholic moral tradition and the Ethi cal and Religious Directives for Catholic Health Care Services established by the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops. It also put out a summary of best practices in fellowships and intern ships in mission and ethics.

Because of the COVID-19 pandemic and the workforce challenges it has spurred, training programs across the health care sector have been disrupted. “With that crisis seeming to ease, and the increased visibility of ethical challenges facing health care today, CHA is hopeful that new energy will be placed into the training and recruitment of qualified ethi cal consultants,” Hibner says.

— LISA EISENHAUER

ethicists that calls for a stairstep approach to training. “Developing consistent entrylevel positions with a relatively small scope of responsibility is critical to this process,” the proposal states. “In no other field would a regional director for six hospitals be con sidered entry-level, yet for ethics it often is.”

Simulated training

Michael McCarthy is an associate pro fessor and director for the graduate pro

gram in health care mission leadership at the Neiswanger Institute for Bioethics and Healthcare Leadership at Loyola Univer sity Chicago. The online program offers advanced degrees in mission leadership and bioethics. McCarthy says the program attracts top-notch students, many of them already in health care, who can bring their knowledge and skills to Catholic health systems.

Because there are few opportunities for its students to get hands-on training before they take on lead roles in the min istry, the Neiswanger Institute has devel oped tools that simulate experiences like those that ethicists have in clinical set tings. One of those tools, called Assess ing Clinical Ethics Skills, takes students through a series of case studies in ethics consultations to develop their compe tency and proficiency.

While the tools aren’t replacements for actual experiences, McCarthy says they get ethicists-in-training closer than most class room settings do to what it’s like to be in consulting and lead roles.

CHA offers a one-year ethics internship that is in its third year. The current fellow, Amanda Berg, is working on her PhD in theology and health care ethics at Saint Louis Uni versity. Berg says she feels her studies have given her a strong theoretical under standing of Catholic health care, ethics and morality.

Berg

Her hope for her fellowship, she says, is to learn to apply that theory. “I don’t have a lot of practical experiences,” she says.

“That’s partially why I’m excited to be a fel low at CHA this year.” leisenhauer@chausa.org

All God's creatures

Several Catholic hospitals sponsored blessings for pets as part of their celebrations of the Feast of St. Francis in October. St. Francis is considered the patron saint of animals because of his love of all creatures. At top, dogs gather at the feet of Fr. Callistus Chukwudi Onumah to be anointed at HSHS St. John’s Hospital in Springfield, Illinois. All pets were welcome, but the event went to the dogs, like the one at left awaiting his turn for the attention of Fr. Onumah, who is HSHS St. John’s priest chaplain. The Hospital Sisters of St. Francis were the founding congregation of HSHS. At far left, Fr. James Dominic Thekkemury smiles as he blesses a picture of a cat held by a sister in a park across the street from St. Francis Medical Center in Monroe, Louisiana. St. Francis Medical Center arranged the blessings. The hospital is part of the Franciscan Missionaries of Our Lady Health System.

Global Health Networking Zoom Call Nov. 2 | Noon – 1:30 p.m. ET Virtual Seminar: Mission Leadership Nov. 7 and 9 | Noon – 4:30 p.m. ET Faith Community Nurse Networking Zoom Call Nov. 15 | 1 – 2 p.m. ET Ecclesial Relationships in Catholic Health Care: A Course for Sponsors and Leaders — Part Three Nov. 10 | 3 – 4:15 p.m. ET United Against Human Trafficking Networking Zoom Call Nov. 16 | Noon – 1 p.m. ET Upcoming Events from The Catholic Health Association chausa.org/calendar

November 1, 2022 CATHOLIC HEALTH WORLD 3

Congregations customize approaches to preserving their ministries

By JULIE MINDA

As congregations sponsoring eldercare facilities lay plans to ensure their minis tries will flourish with or without them, they must devise customized strategies to reflect their circumstances and goals.

Two eldercare ministries shared with Catholic Health World how they’ve proceeded.

Allison Q. Salopeck is president and chief executive of Jennings, a Catholic organization with four Northeast Ohio eldercare campuses. She said that since the Sisters of the Holy Spirt made the decision to transition to lay sponsorship for Jennings, the system has been intentional about pre serving the order’s legacy and charism.

For the first 50 years of Jennings’ 80-year history, the sponsor was a three-person corporate member that included the supe rior of the congregation, the bishop of the Diocese of Cleveland and the president of Catholic Charities in Cleveland. In the 1990s the structure changed and the supe rior of the congregation became the sole sponsor.

In about 2010, the sisters began dis cernment on the future of their order; and, in 2015, they planned to move toward the order’s dissolution with the death of the last sister.

The congregation wanted Jennings to continue as a Catholic system. To achieve this, in May 2020, the sisters formally deter mined with the support of the Cleveland bishop and a team of advisers to transition

Eldercare ministries

From page 1

sponsors and management the essence, purpose and priorities of running a com plex business as a ministry.

More recently, founding congregations of eldercare ministries have been working through these succession issues and dis cerning how best to maintain fidelity to the mission when congregation members no longer work at or even sponsor their facili ties. Some are doing so with the overhang of pressing concerns over keeping their min istries financially viable in what can be a scorching economic landscape for nursing home operators.

Ownership of Catholic continuing care facilities is more decentralized than it is on the acute care side of the ministry.

Many Catholic nursing homes operate as stand-alone facilities without the finan cial shield that can come from being part of a large and sophisticated organization.

Susan McDonough, a Catholic eldercare and post-acute care special ist with Ziegler Investment Bank, said while the minis terial juridic person model has proven an ideal structure for sponsor ship of many ministry systems, it is not a viable choice when congregations have just one or a few facilities. And the structure of sponsorship is related to the Catholicity of an institution; it does not solve financial challenges.

She said many congregations have sought to enter into mergers, affiliations or other types of partnerships with other Cath olic systems or to sell their facilities to them, to ensure the continuation of their minis tries. Some have not been able to make such a match but have had success with merging with another nonprofit that is faith-based or that is not faith-based but is willing to agree to provide a space for religious worship and to hire chaplains to see to residents’ spiri tual needs.

McDonough said there is a great value in preserving Catholic eldercare facilities for the high-touch, compassionate and high-

Jennings sponsorship to a five-person cor porate member body. That group included the first lay sponsors and the final superior of the congregation. She died in 2021. The last sister also died in 2021. The current cor porate member body is comprised of four lay members and a priest.

Salopeck said the sisters knew as they were making these decisions that Jennings would be in good hands.

The sisters’ influence runs deep as Jen nings leaders and associates who worked alongside the sisters and counted the sisters among their friends share funny, heart warming and bittersweet stories of the sis ters with colleagues and residents.

Salopeck says in her three decades with Jennings, she grew close to many of the sis ters, with some of them attending her wed ding and the baptisms of her children.

Artifacts from the congregation’s former home including photos are displayed at every Jennings facility. The residence has been converted to affordable housing.

Lisa Brazytis, Jennings chief marketing officer, is creating a storyline display about the sisters that will go in the lobby of Jen nings’ flagship facility.

Salopeck said of the remembrances of the sisters and their legacy: “It touches something that resonates with people. They remember why they said yes to work ing here, and residents remember why they said yes to living here and staying here.”

Welcoming others

ters’ charism of love for the elderly contin ues to permeate their facilities.

Sisters maintain an ongoing presence in the congregation’s facilities, which are located in Florida, Iowa, Illinois, Kentucky, Massachusetts, New York, Ohio and Penn sylvania. Many of the sisters have worked as administrators or in other leadership roles at Carmelite facilities or have served on the facilities’ boards. Sponsors serve on the board of the Carmelite System. Each of the system’s facilities also has its own board.

Members of the Carmelites’ leadership council and other sisters serve on those boards.

This has helped congregation members become intimately connected with those facilities and their work. Sisters also fill mis sion integration roles at the facilities.

The Carmelites offer a formation pro gram for lay leaders of their facilities and ongoing formation and mission education for all employees.

To preserve the sisters’ legacy, Jennings has been forming its sponsor members in the order’s charisms and in Catholic iden tity. Much of the formation curriculum is from CHA.

Salopeck said Jennings also has been intentional about teaching staff about the history of Jennings and their role in carrying on the mission.

Mother Mary Rose Heery, O CARM, is prioress general and general coun cil member of the Carmel ite Sisters for the Aged and Infirm in Germantown, New York. She said with 138 sisters that congregation has enough mem bers to maintain its role as sponsor of the congregation’s 20 long-term care facilities in the U.S. and Ireland and to ensure the sis

Mother Heery said the Carmelite Sisters restructured their ministries to allow for the full integration of the facilities of the Sisters of Charity of Ottawa to become part of the Carmelite congregation's system. The Sis ters of Charity’s D’Youville Life & Wellness Community in Lowell, Massachusetts, is being folded into the Carmelite System. The two congregations have been undertaking a three-year transition that will end in June 2023.

Mother Heery said the Carmelites are open to assuming responsibility for other congregations' eldercare facilities.

arranging for the last 37 sisters who lived at a motherhouse in Southern Illinois to move to a Benedictine continuum of care complex.

Matchmaking

McDonough has served as matchmaker for small congregations that have agreed to reside together in a facility for the aged. Sometimes congregations have instead chosen to move into their own wing of an eldercare facility.

McDonough explains that this can happen in several ways. When the sisters own an eldercare facility and transfer it to another party, they may agree with the acquirer in advance of the transfer which wing will be for the sisters’ use. As vacancies occur, other sisters could move into that section. Once the sisters’ numbers dwindle, then laypeople would be admitted to that area. These arrangements would be con tingent upon the sisters having a payer for their care.

quality care they provide. She has advised many congregations on how best to plan for their facilities’ ongoing operations as the congregations’ membership declines.

She says her main concern is that sponsors be proactive and “think early about their options, before there are very few options left.”

Letting go

As CHA’s senior director of theology and sponsorship, Fr. Charles Bouchard, OP, advises sponsors of stand-alone nurs ing homes and small eldercare systems and other eldercare services in the Catho lic health ministry on succession planning to ensure their ministries endure without the active involvement of congregation members.

Fr. Bouchard said congregation mem bers may delay the information-gathering and decision-making process as they strug gle with accepting a diminished presence and influence over a ministry they built and nurtured. They must discern whether they want to, or can, maintain some active involvement or whether it’s time to let go of

any control or connection.

He said there are a small number of dwindling congregations that sponsor one or a few facilities that may be waiting too long to make decisions. “This means they have limited time to look for partners, and less opportunity for the sisters to have a personal influence on their successors while the sisters are actively involved,” he said.

McDonough said religious sponsors shoulder a “huge responsibility” and deci sions about the viability of their congrega tions’ ministries and the services they pro vide to communities can weigh heavily. She wants to impress upon sisters and brothers that the best chance to get as close as possi ble to their vision of how the ministries will continue will come from being proactive in planning.

McDonough said if decisions lead to the divestiture of motherhouses, convents and other facilities that once housed aged and infirm members, congregations also must plan to ensure their members are well taken care of until their deaths. The Adorers of the Blood of Christ did this earlier this year,

In some instances, sisters move from a place they own, into a new building that they do not own. If a unit in the new place is empty, the sisters may contract to all move into that same unit, with the proviso that as rooms become vacant on that wing, they would be offered to members of that congregation. This arrangement could come into play when the congregation is relinquishing their property and making a related agreement that will ensure they have a place to live and receive the care they need.

Some congregations decide they don’t need to have all members living in one unit of a facility.

Arrangements will vary based on the desires of the congregation and its mem bers and the availability of living space in the place where they are moving, says McDonough.

The aim usually is to keep as many of the congregation members together under one roof, though that becomes more diffi cult as numbers decline and congregation members need differing levels of care, some of which may not be available in a single location.

jminda@chausa.org

McDonough

Sr. Rose Anthony Mathews, center, joins other residents of Benedictine Living Community — At The Shrine for a chair yoga session. Sr. Mathews is one of 37 Adorers of the Blood of Christ who moved to the eldercare community in Belleville, Illinois, earlier this year as their convent was closing.

Lisa Eisenhauer/@ CHA

The sisters’ influence runs deep as Jennings leaders and associates who worked alongside the sisters and counted the sisters among their friends share funny, heartwarming and bittersweet stories of the sisters with colleagues and residents.

Mother Heery

4 CATHOLIC HEALTH WORLD November 1, 2022

Community Health Worker Academy

From page 1

center and its clinics, part of the CedarsSinai system, provide care to many commu nities that are economically challenged and have high concentrations of immigrants.

Verdugo lives in a com munity near Carson with similar demographics and she speaks fluent Spanish, the language of many of the patients she assists. “I think that’s very important,” she says. “A part of it is that they’re comfortable with me and let ting me know what they need.”

Verdugo’s job includes helping patients follow through on referrals from primary care physicians to cardiologists, neurolo gists and other specialists. She helps sched ule appointments for them and arranges transportation to the visits. She links expectant and new mothers to prenatal and postnatal support groups.

New rule, new training

The Community Health Worker Acad emy is a collaboration between Providence St. Joseph Health and Charles R. Drew Uni versity of Medicine and Science, a private nonprofit school that has the federal desig nation of Historically Black Graduate Insti tution. The academy’s main goal is to train people as community health workers capa ble of assisting patients in clinical settings and in addressing social determinants that impact health outcomes.

Jim Tehan, senior direc tor of community health investment for Providence Southern California, says the partnership launched in 2018. He explains that while Providence has employed community health workers for 20 years to reach underserved populations, for the most part their work has been done outside of clinical settings and often in rural areas. It’s a fairly new approach to put com munity health workers in clinics and hospi tals in urban areas, he says.

The move to incorporate the work ers into clinical settings in California got a boost in July from a rule change that allows care providers to get reimbursement for the services community health workers pro vide to patients enrolled in the state’s Med icaid program. That program, known as Medi-Cal, covers an estimated one-third of the state’s population. The reimbursement

required approval from the federal Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

The list of conditions Medi-Cal says community health workers may address is long and includes the prevention and man agement of chronic illness, mental health conditions including substance use disor ders, reproductive health, environmental health, child health and development, oral health, aging and domestic violence.

CMS defines community health work ers as “trusted members of their commu nity who help address chronic conditions, preventive health care needs, and healthrelated social needs.” The agency says the workers must demonstrate minimum qualifications through one of several path ways, such as by completing a certification program.

Tehan says that because California had no statewide certification program for com munity health workers, Providence was interested in finding an academic partner to establish one.

“As we increased the use of community health workers in a variety of roles, it was like training every person every time, there was no formalized training,” he explains. “It just seemed like kind of a smart idea to develop a pipeline.”

Creating standards

Providence found the partner it needed in Charles R. Drew University, where Hec tor Balcazar, former dean of the College of Science and Health, and Sheba George, associate professor in the Department of Preventive & Social Medicine, already were working on a curriculum for community health workers.

George says she and Balcazar thought standards needed to be developed for training for the workers and to establish a niche within the health care community to tap these workers’ strengths, such as their understanding of the social determinants shaping the health of their communities.

The program trains people to assume entry-level positions in health care. To enter the academy, students must be U.S. citizens who are at least 18 and have a high school diploma or its equivalency. Students do not need clinical experience, although it is preferred.

The academy gives students five weeks of online classroom training to familiarize them with how hospitals and clinics oper ate and to teach them basic skills on how to link patients to medical and social sup port services. Then the students move to

paid internships at sites affiliated with one of several health care providers, including Providence and Dignity Health, which is part of the CommonSpirit Health system. The academy also provides ongoing tech nical assistance to the clinics and hospitals to navigate challenges related to integrat ing community health workers into their teams.

Tehan says Providence finds the hospi tal and community clinic partners for the internships and also manages students’ internship experiences at all of the sites, with particular attention to mentoring and coaching them while they are in the field.

Job security

Providence says the goal of the train ing program is “to create long-term job placements for community health work ers in hospital and clinical settings.” That is one of the reasons that a large chunk of the program’s initial funding came from the California governor’s Office of Busi ness and Economic Development. Other funders include Providence and the university.

Of the 28 students in the first two classes, 26 got offers of full-time positions, many from the providers where they did their internships.

The academy welcomed its third class this fall and Tehan reports that there is already talk of expanding enrollment. Providence is pursuing funding from foun dations and Los Angeles County to bring interns to more sites, including some in the Los Angeles city limits. Tehan says the plan is to continue to keep the class sizes to 15 or fewer and the length of the training at four months but to have two cohorts during each session.

“Many of these participants have not ever worked before,” Tehan says. “As we get to populations that are more of our lived experience population (with little health care background), we feel like it’s important to have that size where people feel like not only are they learning from the training, but they’re also learning from each other.”

Peer to peer

Roland Hinds went through the class room training in the Charles R. Drew acad emy at the suggestion of his supervisor even though he was already a community health worker based in the emergency room at Provi dence Holy Cross Medical Center in Mission Hills. His primary role is to link peo ple experiencing homelessness to shelter, mental health care, substance abuse treat

ment and other services.

When the academy’s second cohort con vened, Hinds went back as a lecturer, and he has joined the board that oversees the academy’s curricula. He also mentors grad uates. He says students have told him that they found the role-playing aspect of the training that introduces real-world skills, such as how to interact with clinicians, as particularly helpful.

He says the academy has allowed hos pitals and clinics to broaden the outreach of community health workers in suburban south Los Angeles County from the Latino community, where they have historical roots. The academy’s graduates are from a range of ethnic and cultural backgrounds as are the area’s residents.

“I can’t stress more that the diversity aspect of it is very important,” Hinds says. “Who knows your neighborhoods bet ter than the person who resides in the neighborhood?”

Easing the burden

Nazaret Núñez, the academy’s program manager, is a former community health worker. She says commu nity health workers face barriers in establishing a footing in clinical settings.

“There’s a lot of work in helping community health workers clarify to other team members and to patients what their role is and what it is that they bring that is different from other health care team members,” she says.

As the daughter of Mexican immigrants, Núñez knows well that someone who can connect with patients based on culture and lived experience can be an invaluable guide to better health outcomes. She remembers as a teenager stepping in to help as she saw how complicated it was for older members of her extended family to get treatment for chronic health conditions.

Núñez says that experience was not unique to her family or to her Latino com munity. She’s aware that many Black and Asian households are just as befuddled by the hoops that they sometimes have to jump through to access health care and social services.

“It makes me really happy to see com munity health workers entering clinical set tings because, hopefully, now there’s family members who can take a little bit more of a step back and find support in the clinic and in the hospital rather than trying to navigate these additional barriers all by themselves,” she says.

leisenhauer@chausa.org

Include your organization’s Christmas message in the Dec. 15 issue of

Verdugo Tehan

George

Hinds

Núñez

Verdugo Tehan

George

Hinds

Núñez

Catholic Health World invites you to extend a holiday greeting to your employees and to colleagues in the Catholic health ministry. Share the joy of the season with a Christmas message to the ministry Visit chausa.org/Christmas for more details. Send an email to ads@chausa.org to reserve your ad space. Ads due by Nov. 22. November 1, 2022 CATHOLIC HEALTH WORLD 5

MENTAL HEALTH CHALLENGES SOAR

Rates of childhood mental health concerns rose steadily between 2010 and 2020.

Mental health of rural youth

From page 1

Ashley Carroll is the division manager of community benefit and advocacy for CHI Health, which has 28 hospitals and a net work of other facilities in Nebraska, south west Iowa, North Dakota and Minnesota. She says, “Behavioral health has been iden tified as a top need virtually everywhere in our service area. As a leading behav ioral health service provider in our region we have been asking how do we fill the gaps by complementing clinical services with com munity-based prevention programs.” The grant dollars and community partnerships have been helping them to do this.

“Behavioral health has been identified as a top need virtually everywhere in our service area. As a leading behavioral health service provider in our region we have been asking how do we fill the gaps by complementing clinical services with community-based prevention programs.”

— Ashley Carroll

A heavy lift

Analysis from the Rural Health Infor mation Hub indicates that people in rural areas can have challenges getting the men tal health services they need because of the poor accessibility, availability, affordability and acceptability of such services there. The Rural Health Information Hub is sup ported by the Health Resources and Ser vices Administration.

The analysis says the accessibility issues are related to the long distances rural dwell ers often must travel to reach service pro viders. The availability problems have to do with the chronic shortages of mental health professionals in these areas. The afford ability concerns relate to the fact that many people in remote areas struggle to afford insurance and can’t pay out-of-pocket costs for health care. The acceptability issue has to do with the stigma attached to mental ill ness in many rural areas and the difficulty of maintaining confidentiality when access ing services in a small town.

Carroll says CHI Health’s community health needs assessments underscore that mental health concerns are interwoven with socio economic pressures that are prevalent in many rural communities.

Joyce Westphal is a social worker and infant and early childhood mental health

consultant who is contracted by CHI Health to help early childhood education pro viders and day cares in Iowa’s Taylor and Adams counties to identify and address mental health concerns among very young children.

She says that mental health stressors are widespread among both children and their teachers in economically depressed communities. Many teachers and students have suffered multiple adverse childhood experiences, or ACEs, that cause or contrib ute to mental health concerns. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says adverse childhood experiences can include witnessing or experiencing violence and abuse or growing up in a family with mental health or substance use problems.

Without intervention, these and other mental health stressors in a child’s life can

The pandemic intensified the youth crisis — ER visits for all mental health emergencies, including suspected suicide attempts, have increased dramatically across the country.

More than 140,000 children in the U.S. lost a primary and/ or secondary caregiver during the pandemic, with youths of color disproportionately impacted.

have a lifelong impact on their well-being. Carroll says: “We’re hearing that there are profound challenges, and we need to be increasingly attuned to the needs of these children. They often are carrying more than backpacks on their shoulders.”

Spectrum of interventions

Lucia Rodriguez Alvizo and Sarah Stan islav are coordinators of Healthier Communities & Community Benefit, the community benefit arm of CHI Health. Rodriguez Alvizo says all the program ming that the system devel ops to address dispari ties in access to mental health services is done with community partners, including schools, early childhood centers, social ser

vice agencies and first responders. Stanislav says a goal is to develop strong referral path ways in communities for families in socioeconomic need.

Carroll says the program ming that CHI Health and its partners are developing is aimed at increasing fami lies’ protective function and reducing their risk factors for mental illness. “We’re trying to spot socioeconomic issues, assess unmet needs and connect families with resources. We ask how can we get them set on a healthy and positive trajectory.”

One of the longest-running and most expansive collaborations is through CHI Health Mercy Corning in Corning, Iowa, where Carroll says CHI Health has funded a spectrum of interventions for youth

LEADERSHIP

NOW AVAILABLE LIVE AND ON-DEMAND

Leaders in Catholic health care recognize the crucial importance of formation in ensuring the Catholic identity of our ministries. In response to member needs, CHA is pleased to introduce Foundations On-Demand as a sister program to Foundations Live.

Foundations Live

JANUARY 31 — MARCH 23,

Foundations Live is an interactive eight-week (virtual) program with sessions each Thursday from 1–3:30 p.m. ET

BUILD COMMUNITY

Engage in meaningful dialogue with ministry colleagues from your system and across the country.

Foundations On-Demand

ALWAYS AVAILABLE

Foundations On-Demand is ideal for new leaders who miss scheduled formation opportunities locally or with CHA. The program is also for those who have difficulty getting away from their work to attend a scheduled program.

DIALOGUE PARTNER

A local dialogue partner supports On-Demand participants as they work the program at their own pace.

Registration is now open for both programs.

CHAUSA.ORG/FOUNDATIONS TO LEARN MORE.

Contact Diarmuid Rooney, CHA senior director of ministry formation, at drooney@chausa.org or 314-253-3465

VISIT

FOUNDATIONS of CATHOLIC HEALTH CARE

Questions?

2023 ✦

✦

✦

✦

By 2018 suicide was the second leading cause of death for youth ages 10-24.

The American Academy of Pediatrics, the American

Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and the Children’s Hospital Association declared a national emergency in child and adolescent mental health in October of last year.

Source: American Academy of Pediatrics resiliency.

Carroll

Westphal

Rodriguez Alvizo

Stanislav

6 CATHOLIC HEALTH WORLD November 1, 2022

mental illness. CHI Health is part of the Behavioral Health Coalition of Taylor and Adams County, Iowa, which has secured more than $1 million in grant dollars since 2017 from the Mission and Ministry Fund, the grantmaking program established by Catholic Health Initiatives and carried on by its parent CommonSpirit.

Programming, training and technology the Behavioral Health Coalition has put in place using CommonSpirit grants and healthy communities funds and other phil anthropic funding along with government investments includes:

Parents As Teachers. The program sends early childhood educators to the homes of toddlers and preschool students to conduct developmental assessments and help parents access services for their kids if warranted. Of the families in the pro gram, 84% were at or below 200% of the fed eral poverty level.

Trauma-informed training for admin istrators and staff of early childhood educa tion centers and day cares, including help ing them understand the impact of trauma on behavior. The training is credited with reducing negative behaviors in preschool classrooms by 90%.

Technology that enables chroni cally truant school-aged children to attend school virtually, either for a short or extended time period. The program has boosted school attendance by 88% among those students.

Sexual abuse prevention training

that teaches youth and their parents to recognize grooming behavior in potential predators.

Mental health first aid training that gives community members the knowledge to assist people with mental illness and direct them to organizations that can pro vide services.

Early intervention

Under her contract with CHI Health, Westphal teaches the staff and administra tors in early childhood education centers and day cares about the social-emotional development of young children and how to use trauma-informed approaches to aid children who may have a mental health problem, or a parent with a mental health problem, and are not thriving in the classroom.

She says that in day care and childhood education, staff often don’t have a formal education beyond high school. Those who do have an associates’ certificate in child development may have had very limited, if any, training in childhood mental illness. She offers practical information about how to work with emotionally troubled children and their parents.

She also provides consultations for staff and administrators who are having trouble managing kids’ behaviors in their centers. And she helps staff and administrators reflect on how their own early childhood traumas and the strains they are experienc ing both at work and in their personal lives

are impacting their response to the children they care for.

“We all have our own emotional stuff that impacts our relationships with others, including children, and the more we are able to reflect on how our emotional trig gers intersect with what a child is experienc ing or how they are communicating with us through their behavior, the better we are able to make adjustments in our responses that will enhance the child’s experiences and development,” Westphal explains.

She says her focus is on teaching adults how to foster healthy relationships.

She says this type of guidance enables early childhood center staff to better relate to the children in their care, to identify and help address mental health issues among the children before they escalate and to ensure they’re creating a nurturing envi ronment for those children. She says early intervention is key in heading off acute mental health issues.

A similar philosophy guides additional mental health programming CHI Health supports in primary schools in Taylor and Adams counties.

Carroll notes that training school staff to be tuned in to the mental health needs of the community’s youth improves the chances that issues can be identified early and addressed.

Visit chausa.org/chworld for additional examples of CHI-supported youth mental health initiatives. jminda@chausa.org

PRESIDENTS AND CEOS

Trinity Health of Livonia, Michigan has made these changes: Montez Carter to president and chief executive of Trinity Health Of New England, from president and chief executive of St. Mary’s Health Care System of Athens, Georgia. Carter succeeds Dr. Reginald J. Eadie, who accepted an appointment as senior vice president of physician enterprise devel opment for Trinity Health. David Spivey to interim president of St. Mary’s Health Care System. He was president of Trinity Health St. Mary Mercy Livonia and senior vice president of community health and well-being for Trinity Health Michigan. Shannon Striebich is interim president of St. Mary Mercy Livonia and continues as president of Trinity Health Oakland and senior vice president of operations for Trinity Health Michigan.

Dr. Rick Thompson to president of CHI Health Nebraska Heart in Lincoln. The facil ity is part of CommonSpirit Health.

ADMINISTRATIVE CHANGES

Dr. Michele Arnold to vice president and chief medical officer of St. Mary’s Medical Center in Grand Junction, Colorado. St. Mary’s is part of Intermountain Health care’s SCL Health.

Peter Gilhooly to executive director of information services and chief information officer of St. Mary’s Healthcare of Amster dam, New York.

Mike Mudd to chief operations officer for Mercy Hospital Northwest Arkansas of Rogers, Arkansas.

Brian Cordasco to vice president of hos pital and clinic operations for Our Lady of the Lake Children’s Hospital in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, part of Franciscan Missionaries of Our Lady Health System.

GRANT

Sioux Falls, South Dakota-based Avera will receive $1 million per year for four years through the Rural Maternity and Obstetrics Management Strategies Program of the Health Resources and Services Administra tion. The grant aims to help increase access to obstetrics services and reduce the incidence of preterm labor, low birthweight babies and infant mortality in rural east ern South Dakota and surrounding tribal communities where there are significant barriers to obstetrics services and related care access. Avera will implement remote patient monitoring and telehealth and will coordinate between medical and social service aspects of obstetrics care.

Sioux Falls’ Avera McKennan Hospital & University Health Center will collaborate on this work with health care facilities in Aber deen, Mitchell, Pierre and Yankton, South Dakota. This grant program pairs with the previously awarded Health Resources and Services Administration’s OB Primary Care Training and Enhancement – Community Prevention and Maternal Health Grant. That $2.3 million grant, which runs through June 2026, is for recruiting and retaining medical providers in rural locations and supporting them with obstetrics training.

KEEPING UP Project1_Layout 1 10/4/22 11:03 AM Page 1

Carter Spivey Arnold

MuddGilhooly Cordasco

March 1, 2022 CATHOLIC HEALTH WORLD 7November 1, 2022

8 CATHOLIC HEALTH WORLD November 1, 2022

Micaela Reyes, a senior community health worker, hands a list of community resources and some new clothing to a patient in the emergency department at Providence Little Company of Mary Medical Center in Torrance, California. Reyes assists patients who are experi encing homelessness in finding shelter and supportive services.

Micaela Reyes, a senior community health worker, hands a list of community resources and some new clothing to a patient in the emergency department at Providence Little Company of Mary Medical Center in Torrance, California. Reyes assists patients who are experi encing homelessness in finding shelter and supportive services.

Verdugo Tehan

George

Hinds

Núñez

Verdugo Tehan

George

Hinds

Núñez