HEALTH PROGRESS

A series of huddle cards depicting the lives of seven saints who represent the core commitments of CHA’s Shared Statement of Identity. Featuring original artwork from Lydia Wood, St. Louis-based artist and activist.

Visit chausa.org/saints to order your cards and accompanying audio files

63106:

Sally J. Altman,

EDITOR’S NOTE

TAYLOR

A

A BARRIER

Lezinsky

COMMUNITY BENEFIT

Raising the Bar for Equity and Community Health

TROCCHIO, BSN, MS

FORMATION

Responding to the Signs of the Times: CHA Launches On-Demand Foundations Leadership Program DIARMUID ROONEY, MSPsych, MTS, DSocAdmin

AGING

Creating a New Paradigm for Aging: 10 Proposals and a Story — America’s Aging Future

DORIS GOTTEMOELLER, RSM

MISSION

Engaging Community to Achieve Health Equity DENNIS GONZALES, PhD

ETHICS

Mission Guided by Prudence

BLANTON HIBNER, PhD

THINKING GLOBALLY

Continued Call to Global Solidarity BRUCE COMPTON

POPE FRANCIS

PRAYER SERVICE

Are you truly collaborative? If you spend some time thinking about what it means to collaborate successfully, you know it involves a complex set of skills. Collaboration, at its most basic level, involves working together toward completing a common task or shared goal. At its highest level, when collaboration succeeds, it leads to worthwhile reform, whether a better process at work, a safer living environment or improved health.

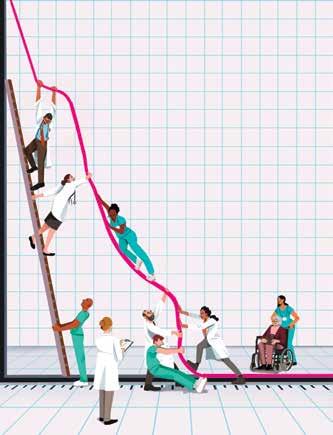

It’s not easy; it is rewarding. The thing is, true collaboration is a challenge. It involves more than motivated people signing on to help out with something be cause they’re joiners or achiev ers. Our cover image shows how collaboration involves think ing about who should be at the decision-making table and then changing that table to include the necessary voices that you’re not hearing from. It involves listening and deep thinking about what you’re trying to accomplish. It in volves unifying around reaching a shared end result, and knowing enough about the data, the best practices, the funding, the culture and the personalities involved to stay the course. Whew. Not easy, but worth it.

This issue of Health Progress looks at care and community collaborations both inside and outside of health care settings. Some of the articles detail wonderful collaborations you may not have heard much about. Others may be more familiar but delve further into the specific

processes for what has worked or been a stum bling block to true collaboration. There has long been the thinking that competition lies at the heart of improvement in health care. But sev eral of the authors make a case for collaboration, that teams where people bring their individual strengths and talents can build toward a whole that will make a difference when tackling a prob lem or working for change.

Another lesson from this issue is that good col laboration sometimes requires saying “no.” No, that’s not where our focus should be. No, I don’t think this project uses my particular skills to the best advantage and use of my time. But it leads to the “yes” of where we’re trying to go, and how. Here’s where our priorities are, and here’s why. Here’s the metrics we’re trying to move and how we’re going to get there. Here’s where we need to reach people where we haven’t before, or here’s a service we’re adding to make people’s lives easier. Because all that collaborative work ultimately can lead to new opportunities or improved systems for patients and others we serve. Collaboration can be messy; it can slow things down, but when done well, it can result in real and lasting good.

®

ADVERTISING Contact: Anna Weston, 4455 Woodson Rd., St. Louis, MO 63134-3797, 314-253-3477; fax 314-427-0029; email ads@chausa.org.

SUBSCRIPTIONS/CIRCULATION Address all subscription orders, inquiries, address changes, etc., to Service Center, 4455 Woodson Rd., St. Louis, MO 63134-3797; phone 800-230-7823; email servicecenter@chausa.org. Annual subscription rates are: free to CHA members; $29 for nonmembers (domestic and foreign).

ARTICLES AND BACK ISSUES Health Progress articles are available in their entirety in PDF format on the internet at www.chausa.org. Photocopies may be ordered through Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Dr., Danvers, MA 01923. For back issues of the magazine, please contact the CHA Service Center at servicecenter@chausa.org or 800-230-7823.

REPRODUCTION No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from CHA. For information, please contact Betty Crosby, bcrosby@ chausa.org or call 314-253-3490.

OPINIONS expressed by authors published in Health Progress do not necessarily reflect those of CHA. CHA assumes no responsibility for opinions or statements expressed by contributors to Health Progress.

Catholic Press Awards: Magazine of the Year — Professional and Special Interest Magazine, Second Place; Best Special Issue, Second Place; Best Layout of Article/Column, Second and Third Place; Best Color Cover, Honorable Mention; Best Guest Column/Commentary, First Place; Best Regular Column — General Commentary, Second Place; Best Regular Column — Pandemic, Second Place; Best Coverage — Pandemic, Second Place; Best Essay, First and Third Place, Honorable Mention; Best Feature Article, First Place and Honorable Mention; Best Reporting on a Special Age Group, Second Place; Best Writing Analysis, Third Place; Best Writing — In-Depth, Third Place.

Trevor Bonat, MA, MS, chief mission integration officer, Ascension Saint Agnes, Baltimore

Sr. Rosemary Donley, SC, PhD, APRN-BC, professor of nursing, Duquesne University, Pittsburgh

Fr. Joseph J. Driscoll, DMin, director of ministry formation and organizational spirituality, Redeemer Health, Meadowbrook, Pennsylvania

Tracy Neary, regional vice president, mission integration, St. Vincent Healthcare, Billings, Montana

Gabriela Robles, MBA, MAHCM, vice president, community partnerships, Providence St. Joseph Health, Irvine, California

Jennifer Stanley, MD, physician formation leader and regional medical director, Ascension St. Vincent, North Vernon, Indiana

Rachelle Reyes Wenger, MPA, system vice president, public policy and advocacy engagement, CommonSpirit Health, Los Angeles

Nathan Ziegler, PhD, system vice president, diversity, leadership and performance excellence, CommonSpirit Health, Chicago

Produced in USA. Health Progress ISSN 0882-1577. Fall 2022 (Vol. 103, No. 4).

Copyright © by The Catholic Health Association of the United States. Published quarterly by The Catholic Health Association of the United States, 4455 Woodson Road, St. Louis, MO 63134-3797. Periodicals postage paid at St. Louis, MO, and additional mailing offices. Subscription prices per year: CHA members, free; nonmembers, $29 (domestic and foreign); single copies, $10.

POSTMASTER: Send address changes to Health Progress, The Catholic Health Association of the United States, 4455 Woodson Road, St. Louis, MO 63134-3797.

Follow CHA: chausa.org/social

ADVOCACY AND PUBLIC POLICY: Lisa Smith, MPA

COMMUNITY BENEFIT: Julie Trocchio, BSN, MS

CONTINUUM OF CARE AND AGING SERVICES: Julie Trocchio, BSN, MS

ETHICS: Nathaniel Blanton Hibner, PhD; Brian Kane, PhD

FINANCE: Loren Chandler, CPA, MBA, FACHE

INTERNATIONAL OUTREACH: Bruce Compton

LEADERSHIP AND MINISTRY DEVELOPMENT: Brian P. Smith, MS, MA, MDiv

LEGAL: Catherine A. Hurley, JD

MINISTRY FORMATION: Diarmuid Rooney, MSPsych, MTS, DSocAdmin

MISSION INTEGRATION: Dennis Gonzales, PhD

THEOLOGY AND SPONSORSHIP: Fr. Charles Bouchard, OP, STD

Chief Sponsorship Officer for Markets and Shared Services at Bon Secours Mercy Health JESSICA WEINGARTNER, MA

Director of Mission at Bon Secours St. Francis Health System

Access to employment that is both meaningful and productive is a key concept of Catholic social teaching. However, there is a recognized gap for young people who have cognitive impairment. While several programs assist this group to transition from school to work, many fall short. Project SEARCH is a school-to-work transition program designed to bridge this gap. It challenges the health care system, school districts and state supportive agencies to join forces to create an arena where human dignity flourishes, communities prosper and the hospital workforce experiences benefits. Participants are provided with the opportunity not just to live life, but to live life in abundance.

Through an effort to bring Project SEARCH to its Greenville, South Carolina, market more than five years ago, Bon Secours St. Francis Health System — through collaboration with community partners — provides an on-the-job hospital train ing program for high school-aged students with disabilities.

For a parent of a child who has disabilities, one of their greatest fears is the thought of, “What will happen to my child when I am gone?” This is certainly not an unfounded worry. Young people with disabilities have a more difficult time secur ing employment following high school gradua tion than their peers without disabilities. This is especially true for young adults with autism spec trum disorder and intellectual and developmen tal disabilities. Students on the autism spectrum have some of the lowest employment rates in the years following high school, even among their peers with other types of disabilities.1

In Catholic health care ministry, we are called

to “bring alive the Gospel vision of justice and peace” through a commitment to the principles of Catholic social teaching, including human dig nity, justice and the common good.2 One of the core themes of Catholic social teaching is the dig nity of work and rights of workers. In the Cath olic social tradition, work is not just a means of obtaining the money required to support oneself and one’s family but is a way in which a person achieves fulfillment as a human being.3 One area where the Catholic health care ministry can con tribute to “the dignity of the individual and the demands of justice”4 is through promoting ave nues for meaningful employment for people with disabilities. This allows them new ways to be pro ductive, flourishing and participating in the life of their community.

Each year, between 70,700 and 111,600 teens on the autism spectrum will transition from schoolbased supportive services into adulthood.5 A.J. Drexel Autism Institute’s 2017 National Autism Indicators Report found that only 14% of surveyed adults on the autism spectrum held a paying job

in the community, and 15% worked in sheltered workshops, typically for less pay than commu nity-based jobs. 6 The students with the worst outcomes often have compounding vulnerabili ties in addition to their diagnosis, including lower household income, difficult family situations and a family history of behavioral health conditions.7

The typical model of transition services for stu dents with cognitive limitations involves a com bination of special education classes with either simulated work environments or short-term community employment; however, the simulated work environment fails to help students meaning fully connect learned skills to the context of real, community-based employment.8 Improving poor employment outcomes requires providing ways to connect students with opportunities to have integrated, community-based work experiences, discover their passions and develop employment

skills. One such program, integrated within the hospital setting, provides Catholic health care ministries the opportunity to live out our Gospel calling to promote the dignity and human flour ishing of these young individuals.

In 1996, a program called Project SEARCH was developed at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center that would not only enable young adults with autism and other disabilities to suc cessfully transition from school to adult life, but would improve the hospital’s workforce as well. Project SEARCH is a high school-to-work transi tion program for young adults with disabilities, with the goal of achieving competitive employ ment. Competitive employment is understood as part- or full-time employment, integrated within the community (for example, not in a sheltered workplace), with compensation at the same rate as other workers without disabilities. Students

involved in the program have varying physi cal, intellectual and developmental disabilities, including autism spectrum disorder, intellectual and developmental disabilities, Down syndrome, hearing and visual impairments, and traumatic brain injury, among others. The program com bines classroom training in employability, inde pendent living and immersive job skills, which empower the students to develop both the hard and soft skills necessary for attaining and main taining competitive employment.

Bon Secours St. Francis Health System brought Project SEARCH to the Greenville market in 2016, joining the health system’s other programs in the Richmond and Hampton Roads regions in Virginia. Pope Saint John Paul II reminds us in Laborem Exercens that it is the responsibility of the entire community to “pool their ideas and resources” to achieve a critically important goal “that disabled people may be offered work according to their capa bilities,” for this is demanded by their dignity as persons and as subjects of work.” 9 With that call in mind, Bon Secours St. Francis began to seek out willing community partners. We quickly formed meaningful ministerial relationships with the Greenville County School District and the South Carolina Vocational Rehabilitation Department — which prepares and assists eligible South Car olinians with disabilities to achieve and maintain competitive employment — to introduce this program to our hospital and the Greenville com munity. Both agencies were familiar with the pro gram and delighted to join our health system in this venture. Program participants are either high school seniors or recent graduates from Green ville County School District, and most are or were followed by South Carolina Vocational Reha bilitation Department throughout their school careers. The program is also supported by the South Carolina Department of Disabilities and Special Needs, Able SC and Goodwill Industries. The collaboration between these agencies is the hallmark of the program’s success.

The program’s operating expenses are covered through Bon Secours St. Francis’ mission depart ment budget. It is housed in the hospital where

a workforce coordinator arranges unpaid intern ships. However, after the young people have the needed job skills and are hired, they earn the same pay as their peers. The Greenville County School District provides a full-time special education teacher and a skills coach, and South Carolina Vocational Rehabilitation Department provides a full-time skills coach and ongoing professional counseling as needed. Together, this core team provides immersive on-the-job training for stu dents. Such placement is crucial to train interns to fill essential, high-turnover, entry-level positions within the hospital. Over the course of the school year, the students rotate through three 10-week internships in various departments throughout the hospital, such as linens, central sterile pro cessing, patient transport, endoscopy and food services.

Candidates with potential to succeed in the program are nominated by special education teachers with the school district. Accompanied by a parent or family member, the candidates come to our site to undergo a skills test. The test is not designed to exclude candidates, rather, it is to identify skill sets, create an entry point for placement, and best indicate which candidates will excel in the program. After the selection is completed, the candidates are notified by a let ter sent to their home. One parent of a candidate recalled the excitement of receiving the letter of acceptance by explaining, “When I opened the letter, I felt like I was opening the golden ticket to Willy Wonka’s Chocolate Factory.” The feeling of joy is shared across the community through social media posts, school system announcements and often a letter of praise from elected officials. The success of the program has had an incredible impact on the lives of the students, their families and the community we serve.

This model is successful because it provides not only on-the-job training, but a multitude of

One parent of a candidate recalled the excitement of receiving the letter of acceptance by explaining, “When I opened the letter, I felt like I was opening the golden ticket to Willy Wonka’s Chocolate Factory.”

other tools for success — which go far beyond the necessary physical skills — required to achieve and maintain competitive employment. Through classroom instruction, the students learn inde pendent living skills, how to manage their per sonal finances and essential self-advocacy skills. The graduates can understand and advocate for their rights in the workplace, articulate their skills and limitations, and request appropriate job accommodations. In addition to general and spe cific job skills, the students learn how to navigate the employment process. The students leave the program having created resumes, completed job applications and interviewed for their positions. The internships are not just assigned to each stu dent, but the students must apply and interview for each rotation. As a result, students learn not only marketable job skills, but also how to look for a job, know what types of jobs they are quali fied for, and come away equipped with the tools needed to be a successful employee.

Perhaps the greatest impact on interns is to their self-confidence and personal growth. Unfortu nately, many students come from a school envi ronment where they are marginalized at best, and actively bullied at worst. Therefore, often their ability to relate to another is lacking as the trust factor has been fractured. Work, as in life, is really all about developing soft skills, which often is a difficult — yet vital — part of securing their employment. Soft skills are best learned through working in an integrated setting with other hospital employees. This is one key component to provide interns insight into gaining an understanding of workplace culture, helping them not just to keep their jobs, but to thrive in them. The integrated work place experience allows for the development of communication skills, attitudes and professional workplace behaviors that employers desire.10

The following is an example of where God’s love for God’s people shines through the creativ ity of the teaching team. Last year, Liam, an intern on the autism spectrum, was doing an excellent job in the linens department but did not speak to his coworkers. The teachers compiled a list of questions for Liam to ask and set the timer for every 20 minutes on his phone. Liam’s instruc

tions were simple, noted as: When the timer goes off, look at your phone and turn to the person on your right and ask the question. Often, the ques tions were: How was your weekend? What is your favorite football team? Why do you love this job? This simple exercise helped Liam to break out of his shell and become comfortable communicat ing with and relating to his coworkers. Enacting such simple practices in the environment allows the intern to flourish and builds the trust needed for success.

The second component of success is twofold, one in how the interns both develop in a caring work environment and the other in how they change the entire culture of the organization. It is easy to witness how our interns are accepted and integrated with our frontline staff. The presence of the interns throughout the hospital is a hardwired part of the organization. Once the interns are ingrained in their roles, they become part of this team. Often high-reliability, high-function ing departments that welcome an intern express the greatest associate satisfaction scores. They are welcomed in birthday parties, invited to staff lunches and fully integrated with their cowork ers. For many interns, outside of their families, this is the first time they have ever functioned in a highly inclusive culture. Working alongside other hospital employees as equals provides a safe environment to learn and develop the soft skills required to flourish in community-based, inte grated employment.

At first, some leaders found it difficult to envi sion a role for interns within their department. In the past five years, the experience of seeing the interns working and flourishing in their work led to the interns being valued and loved members of the St. Francis team. We now have 25 departments with opportunities to place interns — more than the number of interns we have in a given year — and our staff are disappointed if an intern is not assigned to their department for a rotation.

Another great example of this impact is

The second component of success is twofold, one in how the interns both develop in a caring work environment and the other in how they change the entire culture of the organization.

Justin, an intern on the autism spectrum who was nonverbal for most of his life. Justin had been provided with supportive services throughout his schooling, but interning in the hospital really allowed him to flourish. Thanks to supportive coaching and associates who truly included and valued him as a member of the team, Justin slowly began to allow his voice to be heard. His mother recounted one day at the end of the school year when Justin came home after interning. He told his parents, “Hey guys, I got a job.” It was the first time they had heard his voice in years. Justin’s mother says this is the only time she has ever seen her husband cry.

Meaningful ministerial relationships occur when the community’s greatest needs or desires inter sect with the passion of a health care system. The dynamic partnership between Bon Secours St. Francis, Greenville County School District and South Carolina Vocational Rehabilitation Depart ment created media attention, which led to fur ther goodwill and a promise of hope within our community.

The community partnerships that formed to

make this work possible represent the principle of the common good in action. The hallmark of the principle is understanding human beings as essentially social beings and that, in the words of Pope John XXIII, “individual human beings are the foundation, the cause, and the end of every social institution.”11 Striving for the common good unites people of goodwill towards a common pur pose. The common good, says America magazine contributing editor Bill McCormick, SJ, “orders us in reason toward justice, creating social bonds that can be strengthened by charity.”12

The philanthropic community stood with Bon Secours St. Francis in helping to bring the Proj ect SEARCH vision to fruition. The monumen tal success of the program in its first few years led to incredible generosity from businesses and individuals in the community. This gen erosity allowed us to purchase Chromebooks for every intern. In 2021, we expanded the Proj ect SEARCH classroom — thanks to a gener ous donor and our foundation, which secured a $750,000 donation — into an entire training center able to accommodate up to 18 interns at a time. The training center features a classroom with state-of-the-art technological capabilities,

offices for the staff and skills trainers, mock hospital rooms where the students can practice skills before applying them in their internship rotations, and conference space for meetings and interviews.

The program is as beneficial to the hospital as it is to the students it serves and allows us to live out our mission. The internships are designed to train the students to fill real, essential support posi tions within the hospital — they are not merely invented for the sake of a diversity job hire, but are important and needed positions. The roles that the graduates often fill are high-repetition, high-turnover, entry-level positions that hospi tals usually have a difficult time recruiting and maintaining with qualified candidates. The part nerships with support services such as vocational rehabilitation — which often continue after the student has graduated and achieved competitive employment — help the student to be success ful in maintaining their job. Therefore, hiring our graduates is incredibly beneficial to the hospital by filling essential roles and reducing turnover.13

The joy which a family experiences in under standing that their loved one works in an environ ment where they are respected, appreciated and allowed to work to the maximum of their poten tial cannot be underestimated. Competitive, integrated employment provides not only essential income and benefits that will support these individuals throughout the continuum of life, but allows their human dignity to flourish through meaningful work and radical inclusion.

ALEX GARVEY is chief sponsorship officer for markets and shared services at Bon Secours Mercy Health. He is also the scholar in residence at Duquesne University Center for Global Health Ethics. JESSICA WEINGARTNER is director of mission for Bon Secours St. Francis Health System in Greenville, South Carolina, and system ethics lead for Bon Secours Mercy Health.

1. Paul T. Shattuck, “Postsecondary Education and Employment among Youth with an Autism Spectrum Disorder,” Pediatrics 129, no. 6 (June 2012): 1042-49, http://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-2864.

2. “A Shared Statement of Identity for the Catholic Health Ministry,” Catholic Health Association, https:// www.chausa.org/docs/default-source/mission/shared-

statement-flyer_english.pdf?sfvrsn=34ba02f2_4.

3. Pope Francis, Laudato Si’, paragraph 128, https:// www.vatican.va/content/francesco/en/encyclicals/ documents/papa-francesco_20150524_enciclicalaudato-si.html.

4. Pope Benedict XVI, Caritas in Veritate, paragraph 32, https://www.vatican.va/content/benedict-xvi/en/ encyclicals/documents/hf_ben-xvi_enc_20090629_ caritas-in-veritate.html.

5. “Autism Statistics and Facts,” Autism Speaks, https://www.autismspeaks.org/autism-statistics-asd.

6. Anne M. Roux et al., “National Autism Indicators Report: Developmental Disability Services and Out comes in Adulthood,” A.J. Drexel Autism Institute, Drexel University, 2017, https://drexel.edu/~/media/Files/ autismoutcomes/publications/Natl%20Autism%20 Indicators%20Report%202017_Final.ashx; “Subminimum Wage,” U.S. Department of Labor, https:// www.dol.gov/general/topic/wages/subminimumwage.

7. Holly N. Whittenburg et al., “Helping High SchoolAged Military Dependents with Autism Gain Employ ment through Project SEARCH + ASD Supports,” Military Medicine 185, no. 1 (January/February 2020): 663-68, https://doi.org/10.1093/milmed/usz224.

8. Susie Rutkowski, “Project SEARCH: A Demand-Side Model of High School Transition,” Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation 25, no. 2 (November 2006): 85-96.

9. Pope John Paul II, Laborem Exercens, paragraph 22, https://www.vatican.va/content/john-paul-ii/en/ encyclicals/documents/hf_jp-ii_enc_14091981_ laborem-exercens.html.

10. Paul Wehman et al., “Competitive Employment for Transition-Aged Youth with Significant Impact from Autism: A Multi-Site Randomized Clinical Trial,” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 50, no. 6 (June 2020): 1882-97, https://doi.org/10.1007/ s10803-019-03940-2.

11. Pope John XXIII, Mater et Magistra, paragraph 219, https://www.vatican.va/content/john-xxiii/en/ encyclicals/documents/hf_j-xxiii_enc_15051961_ mater.html.

12. Bill McCormick, SJ, “We Need to Make the Common Good More than Just a Slo gan,” America, February 17, 2022, https:// www.americamagazine.org/faith/2022/02/17/ common-good-arturo-sosa-pope-francis-242385.

13. Bonnie O’Day, “Project SEARCH: Opening Doors to Employment for Young People with Disabilities,” Mathematica, December 30, 2009, https://www. mathematica.org/publications/project-search-openingdoors-to-employment-for-young-people-withdisabilities.

Duquesne University offers an exciting graduate program in Healthcare Ethics to engage today’s complex issues.

Courses are taught face-to-face on campus or through online learning for busy professionals.

The curriculum provides expertise in clinical ethics, organizational ethics, public health ethics and research ethics, with clinical rotations in ethics consultation.

Doctoral students research pivotal topics in healthcare ethics and are mentored toward academic publishing and conference presentation.

MA in Healthcare Ethics

(Tuition award of 25%)

This program requires 30 credits (10 courses). These credits may roll over into the Doctoral Degree that requires another 18 credits (6 courses) plus the dissertation.

Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) and Doctor of Healthcare Ethics (DHCE)

These research (PhD) and professional (DHCE) degrees prepare students for leadership roles in academia and clinical ethics.

MA Entrance – 12 courses

BA Entrance – 16 courses

This flexible program requires 15 credits (5 courses). All courses may be taken from a distance. The credits may roll over into the MA or Doctoral Degree (PhD or DHCE).

AUSTIN SCHAFER, MA, BCC Manager for Mission and Pastoral Care with TriHealth

ustin Schafer serves as the manager for Mission and Pastoral Care for the Good Samaritan Hospital region with TriHealth in Cincinnati, Ohio. He’s also a student in Loyola University Chicago’s Health Care Mission Leadership doctoral program. Schafer had Carter Dredge, the senior vice president and lead futurist with SSM Health, as a guest speaker for one of his classes, and wanted to further explore the health care utility model Dredge spoke about there, as his curiosity was piqued about its future applications in the Catholic health care ministry. Dredge advances SSM Health’s research and development, innovation and new venture activities.

A Carter, welcome. First, would you share how you became involved in health care?

I grew up in a four-generation home, sur rounded by people who had a lot of health chal lenges. I had a mother who was paralyzed before I was born. I had a grandfather who was helping take care of my mother and me when I was young. And at the same time, he was also taking care of his mother, who was born in the 1800s. And I just became very passionate about how we take care of one another, particularly individuals who have a lot of health challenges and in many cases oper ate at the margins of society. I work for a Catho lic health care system, SSM Health, which I truly love. I love the mission of the organization, and I’m in the business of alleviating human suffer ing. We’re talking about health care utilities today, because I think they have significant promise to scale the way that we do philanthropic and ministry-oriented work in Catholic health care to an

entirely new level.

Could you describe the basics of what a health care utility is for those who may not have heard about it?

A health care utility is a new type of nonprofit organization that has a social mission to provide essential health care products and services at the lowest sustainable cost possible — in short, it’s a powerful business model for doing good. The term “utility” is a reference to models for other commonly shared basic services like water or electricity. The mission of a health care utility is to make an essential service accessible to every one at the same low cost.1

There are four main aspects that define a health care utility. The first is how it’s structured and governed. Health care utilities are not owned by anyone, but they’re managed by stewards — people who have responsibility to ensure the

services are delivered in the most appropriate way and at the lowest sustainable cost. Second, they’re funded by those stewards/governing members, so they have a customer financing component, and they do so through debt and not equity. That’s really important, because financing is designed to produce low-cost goods and services, not a return in and of itself. So, funding these businesses is a means to getting greater access for essential goods and services. They’re set up to deliver criti cal access and services to the many, particularly those who are vulnerable, and for services that have become very costly.

Third — and this is where it gets its name “util ity” — they provide the services at a transparent and low cost that’s the same for everybody. They provide the services to everyone on equitable terms. It’s not about squeezing out additional profit; it’s about delivering health care at the low est sustainable cost possible so that people can get access to these essential services. And fourth, it’s about the market in which they operate. These entities are not run by the state or a government. Instead, they’re a private enterprise that competes in the marketplace, which means they’re dynamic. And while they are dynamic, they are access maxi mizers, not price maximizers.

Many times when businesses are setting up their marketing strategy, they will ask, “What is the price the market will bear?” That’s not health care utilities. These entities are asking a funda mentally different question: “What is the lowest sustainable cost that I can provide this to the mar ket?” As a result, it actually brings competition to the market.

The most widely known health care utility to date is Civica Rx. Major health systems and phi lanthropists pooled their resources to create a generic drug company that provides drugs used in hospitals for essential inpatient care at a lower cost than those sold by large pharmaceutical companies.

How do health care utilities positively dis rupt the health care marketplace?

This type of collaboration is what we call dis ruptive collaboration. It is collaboration not to maintain the status quo, but collaboration to drive an innovative change. Sometimes, with disruptive innovation, you’re talking about a new technology or a novel way of doing something, like an innova tive technological process. In this case, with dis ruptive collaboration, what we’re doing is we’re bringing innovation to known essential products

by changing the way we work together. The col laboration is a structural innovation, not a tech nological one. So, for example, one of the things that we’re doing is introducing low-cost insulin. It’s not like we have to invent insulin; it’s a prod uct that already exists. However, there are certain elements of the current market that have been keeping insulin at a very high cost even though the medical application of insulin is 100 years old. Insulin is an essential product for people to live, but yet, the drug companies still demand an exces sive — if not extractive — premium to the point where a quarter of Americans who rely on insu lin have to inappropriately ration it.2 The notion behind disruptive collaboration is this: by pulling together the scale of multiple institutions that then make long-term commitments to deliver low-cost services — focused on the needs of the community and the patient — it can positively disrupt the sta tus quo and change health care for the better.

Carter, that’s a major and complex problem in health care — that people can’t afford essen tial medications.

Many times in health care, the reason some thing is expensive is because there’s just a handful of firms that provide it. You could use the term oli gopoly. If there’s less than that, maybe it’s a duo poly. And maybe if there’s just one, it’s a monop oly. In many of these instances, the economies of scale are significant, and no one individual organization, no matter how big they are — even the biggest health care system in the United States — can do it alone. One health system, for instance, doesn’t have the scale to compete with pharma. But if you pull enough of them together, then you have the needed scale. And when you align that scale in a mission-oriented and patient-centric way to create low-cost, high-access services, then you can not only create scale that translates into low cost, you can create scale that translates into low price.

In my doctoral course, you shared that almost all FDA prescription drugs and most health care technological innovations in the U.S. are developed by for-profit entities. And so, if Catholic health care doesn’t increasingly enter this space to compete, I really think the ordinary fabric of U.S. health care is going to become more unaffordable, especially for the poor and vulnerable.

You spoke earlier about turning to the health

care utility model to offer insulin at a lower cost. Civica Rx, as a health care utility, was formed in 2018 by a group of health systems and philan thropies, many Catholic. What are the latest developments with Civica and its impact?

For those not familiar with Civica Rx, it started with a group of 10 organizations: seven health systems — four of which were Catholic health care systems, two other nonprofits and one forprofit health care system — and three philanthro pies. We raised $100 million to create Civica Rx. Nobody owns Civica Rx. It’s financed by health systems and philanthropies, not by external par ties that are trying to create value in the financing itself. With the lower cost medicines that we pro duce, everyone gets the same price. Members of the management team were hired from the phar maceutical industry and the health systems, and members of other organizations also sit on the board of directors.

We now offer more than 60 generic drugs to hospitals and have over 55 health systems as mem bers. We also sell products to the U.S. Depart ment of Veterans Affairs and the Department of Defense. This reach amounts to approximately a third of the total hospital inpatient capacity in the United States.

Additionally, a Civica subsidiary partnering with mission-aligned insurers and other orga nizations — called CivicaScript — is dedicated to lowering the cost of select high-cost generic medicines in the retail setting. It recently recommended that pharmacies charge patients no more than $171 for its first retail medicine used to treat prostate cancer that has spread to other parts of the body. That is about $3,000 per month less than the average cost of this medicine, Abiraterone, for many patients.3

Do you get any political backlash? To me, it sounds like it’s really the best of both worlds — it’s helping the poor and vulnerable, but it’s also something that is competing in the free market.

The great news is that we absolutely have strong bipartisan support for these types of ini tiatives. Once we showed this was working, the federal government got involved as part of a mul tiparty grant — of which Civica was a member — to help build a dedicated pharmaceutical facility in Virginia.4 We will produce essential medica tions at this new manufacturing facility and con tinue to supply both the market and the strate gic national stockpile to ensure that we have an

end-to-end secure pharmacy supply chain pro cess in the United States.

That connects to our Catholic social thought tradition and the fact that health care is a uni versal human right and so critical for promoting human dignity and full human flourishing.

One thing that I’m so passionate about, and just one of the many reasons that I’m so grateful for what CHA does, is that with the innovation of the health care utility model, it comes back to the roots, honestly, of how Catholic health care came to be. There’s a tradition of religious orders for women and others in Catholic health care who have said, “We can’t accomplish what we need to accomplish alone.”

panies to accomplish very specific and focused objectives — with many of these objectives being extremely aligned with those of Catholic health systems. So, while the new health care utilities are not a Catholic entity, they include Catholic entities as founding and governing members, and therefore don’t do anything that would violate the ERDs. These utilities focus on market failures that are hurting people. And that is very aligned with where we need to be: How can we alleviate suffer ing? Catholic health care systems have been great examples of innovation throughout their history because they’ve taken on problems that have not been easily addressable. Taking care of the poor and the vulnerable is an essential thing to do, but that doesn’t mean it’s easy.

Catholic health care systems have been great examples of innovation throughout their history because they’ve taken on problems that have not been easily addressable. Taking care of the poor and the vulnerable is an essential thing to do, but that doesn’t mean it’s easy.

The first hospitals emerged when people realized the need was beyond that of individual groups, and communities came together to basi cally build the institutions we have today. In a sim ilar analogy, we’re realizing that some next-gener ation problems are beyond the scope of the indi vidual institutions of today. We now need to come together again and solve these new and pressing problems. Our communities are counting on us.

That’s an incredible vision because it also connects deeply to the Ethical and Religious Directives for Catholic Health Care Services. The U.S. bishops state that Catholic health care “should distinguish itself by service to and advocacy for those people whose social condi tion puts them at the margins of our society.”

The health care utility model sounds like it does just that as it advocates for the common good, creates greater access to more affordable health care, and focuses on our call to stewardship. How are health care utilities connected with our Catholic mission?

The utility model creates new operating com

Is there a role for mission leaders in this work?

As mission leaders and other leaders in Catholic health care become more deeply aware of how these new business models work, they’re likely to be one of the most in tune groups of lead ers to step back when looking at a problem and to ask, “Is this a utility problem?” This is because they’re already the ones who are per sonally engaging in their respective communities and seeing the problems up close. They will be able to see where the system is lacking coordina tion or scale to adequately solve a problem. They have the potential to catalyze their health minis tries to see the value of this “disruptive collabora tion” mindset and to see opportunities for them to join or create some of these utilities.

What’s the future for health care utilities beyond pharmaceuticals?

We’ve identified over a dozen potential utility applications and think there could be even more; there will be more details as I can talk about them.

At a recent conference that SSM Health hosted in partnership with the University of Cambridge’s Judge Business School in the United Kingdom, we brought together about 30 health care lead ers from numerous countries to talk about new health care utility businesses and what’s next. 5 We’re also working to create a health care utility fund to increase and streamline the production of more health care utilities. This approach has the

potential to reduce human suffer ing and produce innovative nonprofit health care companies that will address some of the most pressing essential access challenges. When I see people engage in this type of utility work, I can see the flame of passion and self less commitment like the collaborative spirit that helped create Catholic health care long ago.

AUSTIN SCHAFER, MA, BCC, is the manager for mission and pastoral care for the Good Samaritan Hospital region at TriHealth in Cincinnati, Ohio. TriHealth is a 50/50 joint operating agreement between CommonSpirit Health and Bethesda, Inc. TriHealth has six hospitals and more than 130 points of care in the Greater Cincinnati region.

1. Carter Dredge and Stefan Scholtes, “The Health Care Utility Model: A Novel Approach to Doing Business,” NEJM Catalyst, July 8, 2021, https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/ full/10.1056/CAT.21.0189.

2. Darby Herkert et al., “Cost-Related Insulin Underuse among Patients with Diabetes,” JAMA Internal Medicine 179, no. 1 (January 2019): 112-14, https://doi.org/ 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.5008.

3. “CivicaScript Announces Launch of Its First Product, Creating Significant Patient Savings,” Business Wire, Aug. 3, 2022, https://www.businesswire.com/ news/home/20220803005101/en/ CivicaScript%E2%84%A2-AnnouncesLaunch-of-its-First-Product-CreatingSignificant-Patient-Savings.

4. “Civica to Build an Essential Medicines Manufacturing Facility in Virginia,” Business Wire, Jan. 21, 2021, https://www.business wire.com/news/home/20210121005790/ en/Civica-to-Build-an-Essential-MedicinesManufacturing-Facility-in-Virginia.

5. “A New Healthcare Utility Initiative to Develop Not-for-Profit Healthcare Business Models Is Launched by Cambridge Judge Business School and SSM Health,” Univer sity of Cambridge Judge Business School, July 19, 2021, https://www.jbs.cam.ac.uk/ insight/2021/new-healthcare-model/.

REX HOFFMAN, MD, MBA, and D.W. DONOVAN, DBe, BCC Chief Medical Officer and Chief Mission Integration Officer, Providence Holy Cross Medical Center

REX HOFFMAN, MD, MBA, and D.W. DONOVAN, DBe, BCC Chief Medical Officer and Chief Mission Integration Officer, Providence Holy Cross Medical Center

Achief medical officer (CMO) routinely interacts with other members of the senior leadership team, including the chief executive, chief nursing officer and chief financial officer. While these relationships may be expected, there is another member of the senior leadership team that chief medical officers should strongly consider partnering with more fully: the chief mission integration officer (CMIO).

So, what does a chief mission integration offi cer do? The chief mission integration officer is an executive-level leader who brings an exper tise in theology and ethics, coupled with a strong familiarity with health care operations, to ensure that the mission and values of a Catholic health care ministry are fully integrated into the dayto-day operations and strategic direction of the ministry. This work can manifest itself in a num ber of ways, including contributing as a strategic partner, assisting in the navigation of complex ethical issues and advocating for both high-qual ity spiritual care and the needs of the poor and vulnerable.

In our roles as CMO and CMIO, we have developed a close working relationship. By sharing examples of how we have mutually benefited by bringing our skill sets and expe rience together, we hope to invite others in these roles to consider how closer collabora tion could better serve the ministry.

On May 1, 2020, in the midst of the COVID-19

pandemic, the Food and Drug Administration approved remdesivir for patients under certain conditions through an Emergency Use Authori zation, with the stipulation that it be administered in a hospital or health care setting capable of pro viding acute care comparable to inpatient hospi tal care.1 This was the first pharmaceutical treat ment to receive FDA approval for COVID-19, and shortly thereafter was released in limited supply.2

Two weeks later, on May 14, 2020, Providence Holy Cross Medical Center received its first allo cation of remdesivir. The amount received was enough to treat, at most, four of the 61 COVIDpositive patients being cared for at the time.

Following the recommendations of both the Providence Office of Theology and Ethics and the California Department of Public Health, lead ership at Providence Holy Cross formed a clini cal discernment team to wrestle with questions about the just and ethical allocation of such a scarce resource. Participants included physi cians from palliative care and infectious disease, as well as hospitalists, intensivists and clinicians from infection control, pharmacy, nursing

administration and ethics. Together, as CMO and CMIO, we chaired the discernment team.

The team was aware that unconscious or implicit bias had the potential to cloud our pro cess. Therefore, as a safeguard, we established a set of inclusion and exclusion criteria that was grounded in the medical literature existing at the time, drawn from the initial finding of the remdesivir study,3 and consistent with guidelines provided by the California Department of Public Health.4

The value of the collaborative partnership between the two of us became particularly evident when the team found itself spending a significant amount of time discuss ing issues around quality of life and whether or not this should be a fac tor in determining if a patient would be offered the medication. Through team discussions and literature review, some argued that reduced physical capac ity and the dependence upon others for assis tance with daily activities of living should “count against” a particular patient when assessing their suitability for receiving this medication.

themselves, doctors rely heavily on both advance medical directives and physician orders for lifesustaining treatment. But for a chief medical offi cer in a senior decision-making role, it is critical to understand that there are nuances to these tools that a particular physician may not have been able to fully appreciate.

Combining our skill sets — the medical knowledge and professional credibility of a CMO with the ethical training and moral credibility of a CMIO — we made a persuasive argument that only evidence-based, objectively observed factors should be considered.

This was not merely an academic exercise — a slight drop in a patient’s overall assessment could remove them from consideration for this invalu able medication. Combining our skill sets — the medical knowledge and professional credibil ity of a CMO with the ethical training and moral credibility of a CMIO — we made a persuasive argument that only evidence-based, objectively observed factors should be considered. Ulti mately, our discernment team developed a pro cess that made this treatment available to the most appropriate patients in the fairest possible way.5

For any provider, ensuring that patients have suf ficient information to make informed decisions dates back to early training in medical school. Medical students absorb lessons by watching more experienced colleagues speak with patients or their surrogate decision-makers.

When talking to a patient, doctors routinely describe potential risks, how treatments may help them and additional options or information they may need when deciding next steps. In cases where patients are no longer able to speak for

Recently, the two of us responded to a medi cal/surgical floor where the nursing staff had alerted us to a concerning situation. A chart had a note from the attending physician that the patient lacked decision-making capacity. There was an advance medical directive that named the patient’s husband as her durable power of attor ney for health care. The consulting surgeon had read the chart and spoken to the husband, receiv ing his consent on behalf of his wife to proceed with the procedure. The patient’s nurse, however, felt strongly that capacity should be reevaluated in light of conversations she had with the patient that morning. However, the consulting surgeon had already left for the operating room and was reluctant to return.

Upon arriving to the floor, the chief medical officer spoke with the patient to get a sense of her capacity while the chief mission integration officer reviewed the advance medical directive. There were several subtle elements that called the validity of it into question, one being that the first page was missing. Also, one of the witnesses on the signature page was the husband (California law does not allow for an advance medical direc tive to be witnessed by the appointed durable power of attorney) and the second witness had the same last name of the husband, which further called the authenticity of the document into ques tion. Finally, the number of pages recorded by the

notary public did not match the number of pages in the advance medical directive, nor did it even come close.

When we were able to speak with the attend ing physician, he admitted to us that he had not personally reviewed the document, nor would he have necessarily noted those inconsistencies. Ultimately, the surgeon did reevaluate the patient and affirmed that she did have decision-making capacity. He thanked the nurse and had a very dif ficult conversation with the husband as to why we might not be moving forward with the procedure. Additionally, we explored in more detail with the patient who she wished to serve as her durable power of attorney in the event she did truly lose decision-making capacity.

While working within the parameters of informed consent is critical to our work, the real ity is that subtle complexities can confound even the most attentive physician. Because this issue is so fundamental to the autonomy and dignity of the patient, the CMIO can be a valuable resource to partner with in this area. Physicians might also consider speaking to their facility’s ethics com mittee or risk management team for advice.

The birth center of a hospital can be a wonder ful place and can sometimes feel comparatively like the one location where good things happen in a hospital. However, things can — and do — go amiss there, and when they do, the provider is often in need of a listening ear and mutually respectful dialogue.

To provide some consistency in how ethi cal issues are addressed in health care delivery throughout the country, the Ethical and Religious Directives for Catholic Health Care — drawn from the Catholic Church’s theological and moral teachings — cover a wide range of issues, includ ing significant attention to matters at the begin

ning of life. An important aspect of the chief mis sion integration officer’s job is to ensure that the local ministry acts consistently with the collec tive identity of the ministry within the Catholic tradition, something that relies on true collabora tion with providers.

For example, the directive regarding the Catho lic commitment not to directly take a life through abortion is clearly stated. But what about those times when the clinical situation is such that an indirect termination is required in order to avoid losing the lives of both mother and unborn child?

A typical situation might evolve as follows: It is late at night when a pregnant woman comes to the emergency room due to her membranes rup turing prematurely. She is 18 weeks pregnant and is devastated with the news that she may lose this pregnancy. The medical team has informed her that the onset of infection is nearly inevitable and that it will not only result in the termination of the pregnancy, but will also put her life at substantial risk.

Despite having worked with such cases in the past, and despite caregivers and providers having worked for many years within a Catholic hospital, such cases almost always invite additional con cerns and discussion. Thus, it is quite common for a chief mission integration officer to arrive fairly quickly — despite the late hour — and to gather the providers and nurses together for a conversation.

In this case, the treatment team affirms their understanding that the premature rupture alone is insufficient a reason to initiate termination of the pregnancy. But few may be able to articulate the ethi cal rationale that grounds this course of action. Some may even voice their concern that religious beliefs are interfering with their ability to provide the best possible care.

The chief mission integra tion officer can reassure the treatment team that religious beliefs and medical practice are not incompat ible. The principle of double effect — which rec ognizes that significant harm, even death, can be morally tolerated (but never embraced) when it is the inevitable secondary effect of a primary, intended, proportionally justifiable action — requires that one has a valid and current medical

While working within the parameters of informed consent is critical to our work, the reality is that subtle complexities can confound even the most attentive physician.

reason for initiating an intervention that has such serious consequences.

When speaking directly to the physician, the chief mission integration officer attests that it is neither his intention nor within his scope to ques tion the doctor’s clinical judgment as to when intervention is needed, and only asks that the pro vider acts in good faith, proceeding with a mor ally undesirable intervention only when there are clinical grounds to do so. He goes on to list a few examples such as a rising temperature or rising white blood count and reiterates that this deter mination is medical rather than ethical in nature. Through this communication, the chief mission integration officer subtly invites the physician into a covenant of integrity, working together to honor a princi ple that is held dear in Catholic social teaching.

As a ministry, we trust that our providers are people of integrity who will collaborate to uphold these principles, and we predicate that cov enant on an agreement that the pro vider is the medical expert who will determine when to move forward, addressing the not-sohidden fear that “doctrine” will trump medical judgment. Through this partnership of trust and understanding, a chief mission integration offi cer can help to ensure a good relationship exists between the obstetrics department and hospital administration.

cians, and several members of the medical staff have a long-standing relationship with him as a confidant and sounding board.

Together, the chief medical officer and chief mission integration officer offer two access points for medical staff to reach out to when they need someone to talk to. Although rates of physician burnout have been higher than ever these past few years,6 we are optimistic that our unified approach at Providence Holy Cross likely contributes to our ministry having one of the highest rates of physi cian well-being across all of Providence in a 2020 survey.7

Together, the chief medical officer and chief mission integration officer offer two access points for medical staff to reach out to when they need someone to talk to.

By working as true partners, a CMO and CMIO can address some of the most challenging issues faced in health care. At Providence Holy Cross, we have found through pairing our unique — but complimentary — skill sets, we can navigate even the most complex issues faced today.

One of a chief medical officer’s primary responsi bilities is attending to the well-being of the medi cal staff, something that became even more imper ative during the COVID pandemic. One helpful approach is to be accessible to them by offering an open-door policy and encouraging them to reach out at any time. When a CMO meets with a phy sician, it is essential to listen intently and try to assist them in any way possible.

Unfortunately, a CMO is only one person and does not have eyes and ears everywhere, thus may only be aware of a portion of those in need. There is a void that potentially exists at hospitals if the CMO is attending to the medical staff alone.

At Providence Holy Cross, the chief mission integration officer fills this void successfully, even without being asked. Although he is not a medical doctor, over time, he has gained the trust of physi

We have found our collaboration to be invalu able. It is likely that others have found the same to be true. But for those who have not yet capitalized on the potential of this relationship, we suggest that what is true in both medicine and ministry is certainly true in our experience: when people with good intentions join their talents together, the results are not merely additive, but truly transformative.

REX HOFFMAN is chief medical officer of Providence Holy Cross Medical Center in Mission Hills, California. D.W. DONOVAN is chief mission integration officer of Providence Holy Cross Medical Center.

1. “Coronavirus (COVID-19) Update: FDA Issues Emer gency Use Authorization for Potential COVID-19 Treat ment,” U.S. Food & Drug Administration, May 1, 2020, https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-

announcements/coronavirus-covid-19update-fda-issues-emergency-useauthorization-potential-covid-19-treatment.

2. “Important Information About Veklury,” U.S. Department of Health & Human Ser vices, https://aspr.hhs.gov/COVID-19/ Therapeutics/Products/Veklury/Pages/ default.aspx.

3. John H. Beigel et al., “Remdesivir for the Treatment of Covid-19 – Final Report,” The New England Journal of Medicine 383, no. 19 (November 2020): 1813-26, https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/ NEJMoa2007764.

4. “California Health and Human Services Remdesivir Distribution Fact Sheet,” Cali fornia Department of Public Health, May 29, 2020, https://www.cdph.ca.gov/Programs/ CID/DCDC/Pages/COVID-19/Remdesivir-

Distribution-Fact-Sheet-.aspx.

5. D.W. Donovan and Rex Hoffman, “Provi dence Holy Cross Outlines Steps for Ethical Distribution of a COVID Medication,” Health Progress 101, no. 4 (Fall 2020): 57-60, https://www.chausa.org/publications/ health-progress/archives/issues/nurses/ providence-holy-cross-outlines-steps-forethical-distribution-of-a-covid-medication.

6. Joy Melnikow, Andrew Padovani, and Marykate Miller, “Frontline Physician Burn out during the COVID-19 Pandemic: National Survey Findings,” BMC Health Services Research 22, no. 1 (March 2022): http:// doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-07728-6.

7. “Southern California AMA Medical Staff Survey Results — Providence Report,” Provi dence Holy Cross Medical Center, 2020.

Chief Medical Officer Rex Hoffman and Chief Mission Integration Officer D.W. Donovan at Providence Holy Cross Medical Center in Los Angeles describe the importance of partnerships and knowing where one job ends and another begins as the roles relate to challenging medical and ethical decisions in health care environments.

1. If you are in a chief medical officer or chief mission integration officer role, do you make time to talk about how and when you communicate with each other? When more people need to be a part of a conversation, is a good, prompt system in place that allows for that?

2. Does your health care organization have clear guidelines in place to avoid bias in complex decision-making? Is there a clear understanding of foundational standards and the timing and process of decision-making? What can be done to make sure you’re communicating with patients and their loved ones in a way that is empathetic, clear and provides them with the information and support they need?

3. How can senior leaders do a better job making sure other employees understand the responsibilities of chief medical officers and chief mission integration officers and how they can convey questions or concerns to them?

from The Catholic Health Association

Virtual Program: Community Benefit 101

Oct. 25 – 27 | 2 – 5 p.m. ET

Diversity & Disparities Networking Zoom Call

Oct. 25 | 1 – 2 p.m. ET

Global Health Networking Zoom Call

Nov. 2 | Noon – 1:30 p.m. ET

Virtual Seminar: Mission Leadership

Nov. 7 and 9 | Noon – 4 p.m. ET

Faith Community Nurse Networking Zoom Call

Nov. 15 | 1 – 2 p.m. ET

United Against Human Trafficking Networking Zoom Call

Nov. 16 | Noon – 1 p.m. ET

chausa.org/calendar

NADINE NADAL, MPH, CPH, CHES Director, Community Health Development, CHRISTUS Health

NADINE NADAL, MPH, CPH, CHES Director, Community Health Development, CHRISTUS Health

n the Highland neighborhood of Shreveport, Louisiana, 22-year-old Robert Renter leans against a table inside a home called a Friendship House. Part residence and part community center, the Friendship House has come to mean a lot to Renter, who ner vously finds his words to explain to visitors something so sentimental to him: “I am a young Black man in America, and five or six years ago, I wasn’t exactly a model student.”

Today, Renter — who works in Shreveport for a telecommunications company — says, “Life is good.” He smiles as he talks about his girlfriend and a younger brother he says he might spoil too much. Of his mentor at the Friendship House, Diedra Robertson, he says, “Ms. Diedra helped me get here by giving me an after school outlet where I could be with my good friends. Matter of fact, I’m best friends to this day with my friend from here.”

neighbor. Strategically located in high-crime, lowemployment areas, the homes are meant to be a beacon of hope to young people and others.

Strategically located in high-crime, low-employment areas, the homes are meant to be a beacon of hope to young people and others.

Robertson lives in a Friendship House with her husband, and she is a supervisor to a grow ing number of Friendship Houses in the Shreve port-Bossier City area. The eleventh Friendship House is scheduled to open soon. Robertson explains that the goal of the Friendship Houses effort — operated under the nonprofit Commu nity Renewal International — is to mentor, build mutually beneficial relationships and to solve problems internally, street by street, neighbor to

“We’re a place that’s safe, where afterschool programs, adult literacy programs and other community activities are hosted,” says Robert son. “Actually, we held our first community health fair just a few weeks ago. It was a success.” Of the health fair’s 20 community partners in atten dance, two — St. Luke’s Episcopal Medical Min istry and Shreveport Green — were funded by the CHRISTUS Community Impact Fund. The fund — which is the grantmaking arm of CHRIS TUS Health — works to invest in communitybased, long-term, transformative and sustainable

Access to healthy foods

Walkability

Violence and trauma

Community participation

Social connection

Racism

Access to health care

Access to primary care

Health literacy

Food insecurities

Housing instability

Employment

Source: The Department of Health and Human Services

Early childhood education and development

High school graduation

Higher education completion

strategies that address the underlying causes of poor health and, most importantly, reenvisions the role of a funder into a collaborator. Through these partnerships and other collaborations, CHRISTUS Health is working to transform the health and well-being of its communities.

Although CHRISTUS and its ministries alone can not solve all of society’s problems, the health care system can play a role in convening and collabo rating with other organizations to create innova tive solutions to complex and long-standing local challenges. Each year, CHRISTUS Health, through the Community Impact Fund, provides financial support and capacity-building opportunities to 30-40 grantees across its U.S. ministries within Texas, Louisiana and New Mexico. We respond to the needs voiced in the communities we serve and partner with organizations like Shreveport Green’s Mobile Market, St. Luke’s Episcopal Medical Ministry (see sidebars) and Community Renewal so that we can do more together through collaborative relationships. CHRISTUS’ mission calls us to do this: extend the healing ministry of

Jesus Christ. We strive to achieve this with others beyond the walls and brick-and-mortar of hospi tals, clinics and family health centers.

Working in partnership with community orga nizations is a way the CHRISTUS Community Impact Fund addresses the social needs and social determinants of health of individuals and com munities. The Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion of the Department of Health and Human Services groups social determinants of health into five areas: economic stability; edu cational access and quality; health care access and quality; neighborhood and built environment; and social and community context.1

To “revillagize” its communities — or to build relationships and strengthen neighborhoods — one of CHRISTUS’ partners, Community Renewal, seeks to work on strengthening eight aspects of what it means to be a healthy commu nity: mutually enhancing relationships; housing; safe environment; health; education; culture of caring; leadership system (the ability to effectively negotiate and mobilize resources); and meaning ful work. Many of these elements fall under the same pillars of social determinants of health. For

example, mutually enhancing relationships falls under social and community context and safe environment falls under neighborhood and built environment determinants. Part of this work to restore village-like connections includes a series of activities for each community to tell its history and shape its identity, countering previous soci etal narratives and bringing neighbors together.

Through an investment of $467 million over the last fiscal year to its Community Benefit program and $3 million to its Community Impact Fund, CHRISTUS Health is committed to improving the well-being of its communities. These community

benefit initiatives include charity care, unreim bursed indigent care and the community services and partnerships the system does as a team — the internal campaign called One CHRISTUS — to address these social determinants of health.

Data from the Louisiana Department of Health’s 2021 Louisiana Health Report Card shows that in Region 7, where Shreveport sits, cancer, heart disease, diabetes and other chronic diseases are drivers of mortality in northwest Louisiana, and that significant racial and ethnic disparities exist with these conditions, resulting in higher mortality rates among historically marginalized

Part of CHRISTUS Health’s process when conducting its Community Health Needs Assessment involves the use of a data visualization platform called Metopio. Through this mapping technology, the tool is able to show health disparities by zip code. During the COVID-19 pandemic, CHRISTUS Health’s Community Impact Fund evolved to apply an equity lens in its process. One of the fund’s equity approaches involved identifying communities of concern — which are zip codes that rank highest within the area deprivation, social vulnerability and hardship index — to help CHRISTUS understand the most under-resourced areas and allocate our investments for greater impact.

individuals. 2 Identified within the 2020-2022 CHRISTUS Shreveport-Bossier Health System’s Community Health Needs Assessment (CHNA), prioritized areas were access to care, child safety and well-being, and disease prevention and man agement. As further revealed in the 2021 Louisi ana Health Report Card, Black Louisiana residents have been disproportionally affected by COVID-19, particularly in the early months of the pandemic.3

While the coronavirus might have exacerbated existing health inequalities influenced by zip code and shed more light on national social vulnerabili ties, it has always been on the mind of people like Rev. Mack McCarter. After seminary, McCarter spent 20 years pastoring churches in West Texas before returning to his hometown of Shreve port, where he started Community Renewal, a nonprofit faith-based organization, in 1994. His early work to get people to open their doors and develop relationships resulted in several com munity outreach strategies like the Friendship Houses, Haven Houses and the Renewal Team to transform neighborhoods into safe havens of friendship and support.

Other community organizations across Shreveport are also partnering with the CHRISTUS Community Impact Fund. A recent example includes the nonprofit Shreveport Green’s Mobile Market, a program that offers nutritional food assistance, cooking education and social gathering opportunities for anyone who needs them. The Mobile Market serves neighborhoods that lack access to healthy foods. It brings fresh fruits and vegetables from more than 20 community gardens to consum ers in these food deserts, offering them at a manageable price and showing them healthy ways to prepare them.

Every three years, CHRISTUS Health gathers qualitative and quantitative data from its Com munity Health Needs Assessment (CHNA) to better understand the communities it serves. In the 2020-2022 CHRISTUS Health ShreveportBossier CHNA, addressing nutrition-related illnesses like obesity, heart disease and Type 2 diabetes was identified as a great need.

According to the U.S. Department of Agricul ture, not only is inaccessibility to healthy fresh food a big problem in Shreveport, but so is its expense and the lack of knowledge in prepar ing it. Through its partnership with Shreveport Green, CHRISTUS Health is addressing food insecurity to sustain healthier lives for Shreveport-Bossier residents.

The first of Community Renewal’s three pri mary strategies, the Friendship Houses, serve as a bridge to improved change and redevelopment for residents and neighbors who are at highest risk of experiencing isolation, discrimination and other social determinants of health. Community Renewal trains and employs community coordi nators. They and their families move into these homes and live as neighbors — not as 9-to-5 ser vice providers. Through building trust and rela tionships with their neighbors while living in the Community Renewal-owned homes, community coordinators help residents to set and achieve basic goals by facilitating in-house programs like afterschool activities, adult education, family events, service projects and more.

“You can email someone across the world, but you don’t know who’s living and dying five houses from you.”

To avoid ending up in an emergency room or becoming severely ill, CHRISTUS Health’s Shreveport-Bossier CHNA also indicated that residents of northwest Louisiana need easily accessible and affordable health care. Working off its relational model that worked success fully with Community Renewal and the Mobile Market, CHRISTUS Health found a like-minded community partner in St. Luke’s Episcopal Medical Ministry. Using an RV that brings the physician’s office directly into neighborhoods where needed, this team provides an outlet for community members to manage their physical ailments or chronic diseases through preventive health screenings, basic primary care health services, medication refills, health education and medical referrals — all free of charge. The team serves not only those without health insurance — including the community’s homeless population — but also people with coverage who may be experiencing barriers to access due to transportation, system naviga tion difficulties or other issues.

Serving northwest Louisiana’s underserved residents since 2008, St. Luke’s Mobile Medi cal Ministry offers 20-22 clinics each month. Funding comes from individual donors, grants, community organizations and the Episcopal Diocese/churches. Staff consists of a group of registered nurses, nurse practitioners and physicians. By playing a prominent role in preventive care for residents in need, the orga nization is helping to improve the quality of life for the region’s medically underserved while empowering them to make healthier choices.

Another Community Renewal initiative, Haven House, brings together caring residents who are willing to reach out to their neighbors. Identified as a Haven House by a “We Care” sign in their front yard, Haven House leaders are trained vol unteers who turn strangers into friends on their own neighborhood block. They may host block parties or bring meals to a sick neighbor, find a lost pet, mow someone’s yard or bring their trash bin in from the street.

Connected to the same mission of creat ing stronger communities, another strategy, the Renewal Team, consists of volunteers who build relationships citywide by uniting individuals, faith groups, businesses, civic groups and others as caring partners.

“You can email someone across the world, but you don’t know who’s living and dying five houses from you,” McCarter often explains, taking Jesus’ “Love Thy Neighbor” imperative seriously.

Michael Leonard, a retired Shreveport den tist, spent a few years volunteering for Commu nity Renewal. When he retired from his prac tice, he decided to join the team as a Community Renewal staff member. “Positive relationships put into a system can renew collapsing communities and societies,” says Leonard. Now serving as the organization’s associate coordinator, he further explains, “When communities flourish, it posi tively impacts our health and well-being.”

Community Renewal has been making an impact on communities for more than 25 years, and CHRISTUS Health is proud to partner with the organization to continue its efforts to restore safe and caring communities. Their work is even expanding and getting attention in many other communities across the globe, including coun tries as far as Cameroon, Africa.

With all partnerships, knowing the impact that endeavors make is key to further refine efforts, and data helps to show what works. The Shreve port Police Department reported a drop in major crime by 70% from 2001 to 2019 and a drop of 61% in total reported crime in the city’s Allendale neighborhood.4 CHRISTUS is developing an out comes tracking system to see what sort of measur able impact we may be experiencing by investing in this work. It includes performance measures and tracks end results as a way to make future decisions and set budgets.

To measure the effects of Community

Renewal’s work, the Community Impact Fund requires the Results-Based Accountability model to track outcomes at the population and program matic levels. At the programmatic level, the model helps CHRISTUS and its partners understand how many individuals the program serves, how well the program was delivered and how many individuals are better off due to the program’s interventions.

Marlin Blaze sees the qualitative value of Com munity Renewal. As a volunteer neighborhood ambassador for the program, Blaze is dedicated to developing positive relationships in his Allendale neighborhood, an area once plagued with crime and drugs. It is a neighborhood he describes as once brutal and one where he grew up without much support. “I didn’t meet my dad or my dad’s side of the family until I was 30 years old,” he says.

Blaze chose a different path than many of his friends and is building positive relationships in his new role. He’s on the same track of building up others as is his friend and Community Renewal colleague, Pam Morgan.