HEALTH PROGRESS

www.chausa.org

JOURNAL OF THE CATHOLIC HEALTH ASSOCIATION OF THE UNITED STATES

OUR

WINTER 2023 LIVING

CATHOLIC IDENTITY

➲ Beginning this January, join us as we renew our rhythms of well-being — intentionally, mindfully, prayerfully and communally. chausa.org/renewyear YEAR R E NEW START THE YEAR WITH A FOCUS ON WELL-BEING MISSION MONDAY • TIME TO THINK TUESDAY WONDER WEDNESDAY • THANKFUL THURSDAY • REFOCUS FRIDAY 20 23 I came

they might have life and have it more abundantly. — JOHN 10:10

so

DEPARTMENTS

WINTER 2023

2 EDITOR’S

BETSY

54

Survey Reveals Encouraging Trends — and Concerns —

Mission Leaders

58

BENEFIT CHA Guide Incorporates Equity Into All Aspects of Community Benefit JULIE

BSN, MS 61 ETHICS What Is Abortion?

PhD 65 AGING Mapping

Diversity, Equity and

in Aging Services JULIE

MS 68

Transforming Health in

Changing World

31 POPE FRANCIS — FINDING GOD IN DAILY LIFE 72 PRAYER SERVICE 4 MAINTAINING IDENTITY AND INCLUSIVITY IN CATHOLIC HEALTH CARE John O. Mudd, JD, JSD, and John Shea, STD 10 HARNESSING OUR POWER THROUGH CHARISM Fr. Joseph J. Driscoll, DMin 15 ENSURING QUALITY CARE MEANS PRIORITIZING THE MOST VULNERABLE: A Q&A WITH DR. ALISAHAH JACKSON Kelly Bilodeau 19 A GUIDE TO MAINTAINING CLINICAL TRIAL INTEGRITY IN CATHOLIC HEALTH CARE Pukar Ratti, CIM, CCRP, FACMPE, and Steven J. Squires, PhD, MEd 25 UNPRECEDENTED TIMES CALL FOR REVAMPED LEADERSHIP SKILLS Martin Schreiber, EdD 32 FLOURISHING THROUGH FORMATION: CATHOLIC IDENTITY IS REINFORCED WITH THOUGHTFUL APPROACHES Sarah Reddin, D.HCML 38 THE EVOLUTION OF SPONSORSHIP MODELS: A PROGRESS REPORT Fr. Charles Bouchard, OP, STD 45 WHY LISTENING MATTERS FOR BETTER UNDERSTANDING IN A DIVIDED CHURCH Bishop John Stowe, OFM Conv. LIVING OUR CATHOLIC IDENTITY HEALTH PROGRESS www.chausa.org WINTER 2023 1 HEALTH PROGRESS®

48 FINDING HEALTH: MAYBE WE NEED TO LOOK ELSEWHERE?

IN YOUR NEXT ISSUE THINKING STRATEGICALLY

NOTE

TAYLOR

MISSION

for Future of

DENNIS GONZALES, PhD, and JILL FISK, MATM

COMMUNITY

TROCCHIO,

BRIAN M. KANE,

the Road to

Inclusion

TROCCHIO, BSN,

THINKING GLOBALLY

a

BRUCE COMPTON

FEATURE

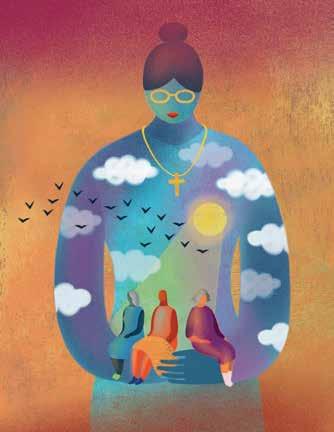

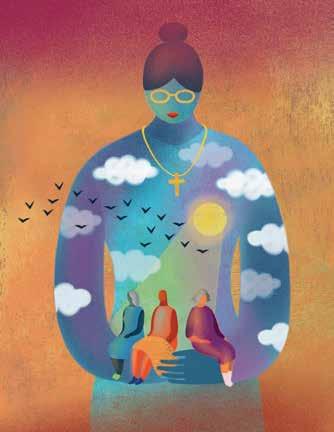

Alexander Garza, MD Illustrations

by Anna Godeassi

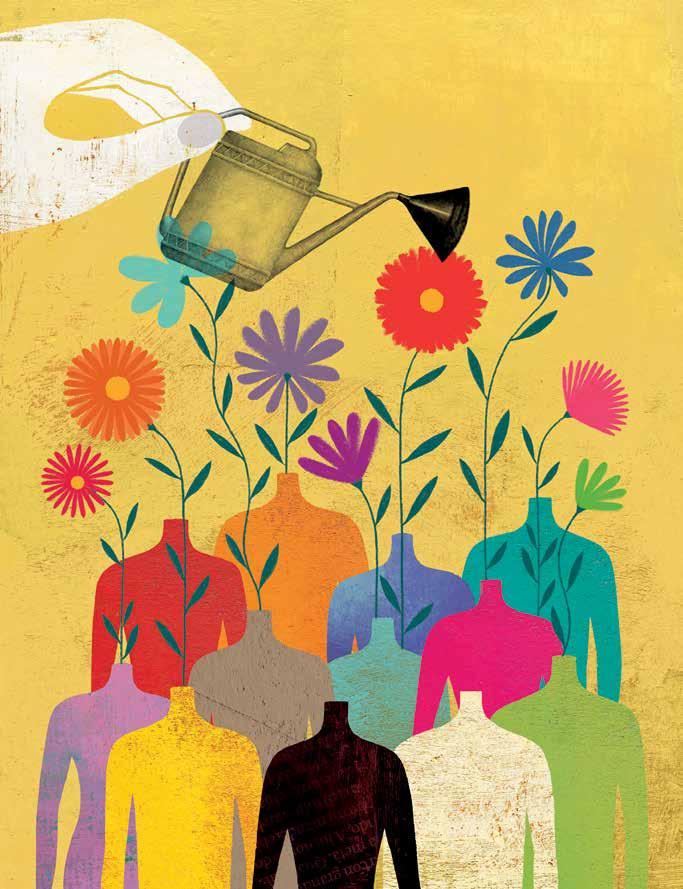

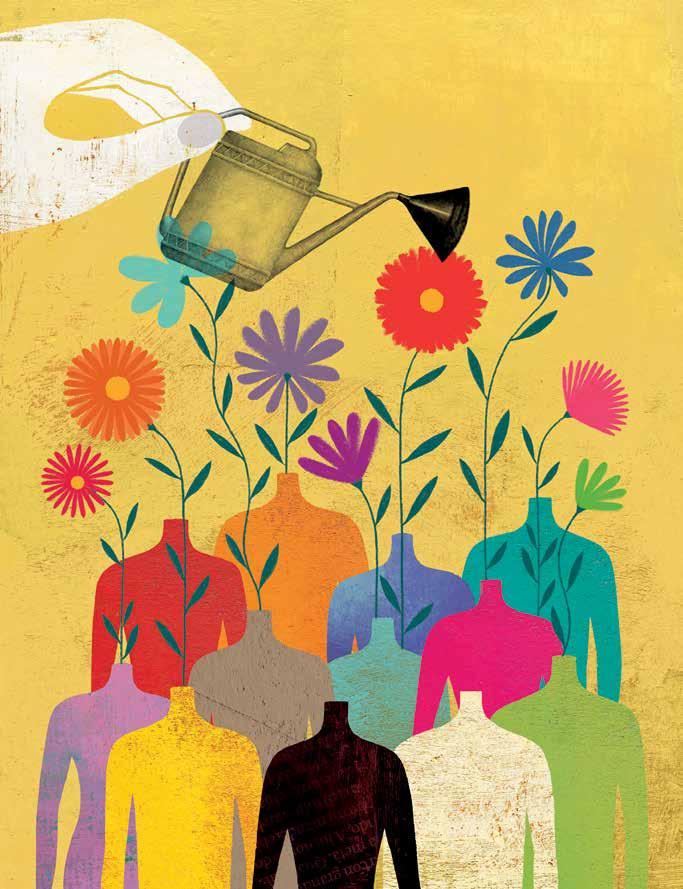

People long to connect with community, to believe their work is meaningful and to feel spiritually whole. At CHA, we’ve certainly been asked by the membership to focus on well-being and caring for the whole person.

because from the 1970s to the 2010s, Catholic Mass attendance in the United States dropped by roughly half, according to a survey highlighted in a recent National Catholic Register article. The less populated pews have become even more pronounced after the height of the COVID pandemic, as parishioners have not returned to prepandemic numbers.1

BETSY TAYLOR

And this issue of Health Progress, along with previous ones, reinforces that shared identity can make a difference in Catholic health care systems. In the opening article of this issue, two authors with longtime ties to Catholic health care, John Shea, STD, and John Mudd, JD, JSD, explain that they’ve found one of the best ways to allow Catholic identity to thrive is to not water it down. This includes not only using language and examples that others understand, and finding connections that resonate with people who have diverse backgrounds and experiences, but also knowing that the faith’s central messages resonate broadly and remain timeless and powerful.

Health Progress has included a few articles in recent issues where health care executives in human resources, mission and formation are increasingly collecting data, while from relatively small sample sizes, showing that the Catholic identity of the ministry work can be a recruitment and retention factor for some employees. Ascension’s Vice President of Ministry Formation and Mission Integration Sarah Reddin, D.HCML, makes that point in this issue as well, noting that one of Ascension’s leadership programs has found participants much more likely to stay with the system for at least two years than those who do not take part.

This resonates as being all the more striking

If we know the central, beautiful truths of Catholicism have lifted believers across millennia, and we know that people are actively seeking ways to feel connected and whole, is it possible that Catholicism needs to improve its invitation and approach, perhaps to focus less on what divides us, and more on what we share in common? That is, maybe not further refine the message itself, but instead its delivery?

While it is not a Catholic concept, one that I return to is tikkun olam from Judaism, the concept of engaging in acts of kindness to repair the world. As we embark on a new year, I am always filled with hope — hope that I may bring my best self both to my work and my life outside of it. And I also hold hope that as people search for meaning and healing, we may offer the hand of hope or healing they seek.

NOTE

1. Joan Frawley Desmond, “The Catholic Church Battles to Fill the Pews,” National Catholic Register, Dec. 1, 2022, https://www.ncregister.com/news/ the-catholic-church-battles-to-fill-the-pews.

EDITOR’S NOTE

2 WINTER 2023 www.chausa.org HEALTH PROGRESS

®

VICE PRESIDENT, COMMUNICATIONS AND MARKETING BRIAN P. REARDON EDITOR BETSY TAYLOR btaylor@chausa.org

MANAGING EDITOR CHARLOTTE KELLEY ckelley@chausa.org

GRAPHIC DESIGNER NORMA KLINGSICK

ADVERTISING Contact: Anna Weston, 4455 Woodson Rd., St. Louis, MO 63134-3797, 314-253-3477; fax 314-427-0029; email ads@chausa.org.

SUBSCRIPTIONS/CIRCULATION Address all subscription orders, inquiries, address changes, etc., to Service Center, 4455 Woodson Rd., St. Louis, MO 63134-3797; phone 800-230-7823; email servicecenter@chausa.org. Annual subscription rates are: free to CHA members; $29 for nonmembers (domestic and foreign).

ARTICLES AND BACK ISSUES Health Progress articles are available in their entirety in PDF format on the internet at www.chausa.org. Photocopies may be ordered through Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Dr., Danvers, MA 01923. For back issues of the magazine, please contact the CHA Service Center at servicecenter@chausa.org or 800-230-7823.

REPRODUCTION No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from CHA. For information, please contact Betty Crosby, bcrosby@ chausa.org or call 314-253-3490.

OPINIONS expressed by authors published in Health Progress do not necessarily reflect those of CHA. CHA assumes no responsibility for opinions or statements expressed by contributors to Health Progress.

2022 AWARDS FOR 2021 COVERAGE

Catholic Press Awards: Magazine of the Year — Professional and Special Interest Magazine, Second Place; Best Special Issue, Second Place; Best Layout of Article/Column, Second and Third Place; Best Color Cover, Honorable Mention; Best Guest Column/Commentary, First Place; Best Regular Column — General Commentary, Second Place; Best Regular Column — Pandemic, Second Place; Best Coverage — Pandemic, Second Place; Best Essay, First and Third Place, Honorable Mention; Best Feature Article, First Place and Honorable Mention; Best Reporting on a Special Age Group, Second Place; Best Writing Analysis, Third Place; Best Writing — In-Depth, Third Place.

Produced in USA. Health Progress ISSN 0882-1577. Winter 2023 (Vol. 104, No. 1).

Copyright © by The Catholic Health Association of the United States. Published quarterly by The Catholic Health Association of the United States, 4455 Woodson Road, St. Louis, MO 63134-3797. Periodicals postage paid at St. Louis, MO, and additional mailing offices. Subscription prices per year: CHA members, free; nonmembers, $29 (domestic and foreign); single copies, $10.

POSTMASTER: Send address changes to Health Progress, The Catholic Health Association of the United States, 4455 Woodson Road, St. Louis, MO 63134-3797.

Follow CHA: chausa.org/social

EDITORIAL ADVISORY COUNCIL

Trevor Bonat, MA, MS, chief mission integration officer, Ascension Saint Agnes, Baltimore

Sr. Rosemary Donley, SC, PhD, APRN-BC, professor of nursing, Duquesne University, Pittsburgh

Fr. Joseph J. Driscoll, DMin, director of ministry formation and organizational spirituality, Redeemer Health, Meadowbrook, Pennsylvania

Tracy Neary, regional vice president, mission integration, St. Vincent Healthcare, Billings, Montana

Gabriela Robles, MBA, MAHCM, vice president, community partnerships, Providence St. Joseph Health, Irvine, California

Jennifer Stanley, MD, physician formation leader and regional medical director, Ascension St. Vincent, North Vernon, Indiana

Rachelle Reyes Wenger, MPA, system vice president, public policy and advocacy engagement, CommonSpirit Health, Los Angeles

Nathan Ziegler, PhD, system vice president, diversity, leadership and performance excellence, CommonSpirit Health, Chicago

CHA EDITORIAL CONTRIBUTORS

ADVOCACY AND PUBLIC POLICY: Lisa Smith, MPA

COMMUNITY BENEFIT: Julie Trocchio, BSN, MS

CONTINUUM OF CARE AND AGING SERVICES: Julie Trocchio, BSN, MS

ETHICS: Nathaniel Blanton Hibner, PhD; Brian Kane, PhD

FINANCE: Loren Chandler, CPA, MBA, FACHE

INTERNATIONAL OUTREACH: Bruce Compton

LEGAL: Catherine A. Hurley, JD

MINISTRY FORMATION: Diarmuid Rooney, MSPsych, MTS, DSocAdmin

MISSION INTEGRATION: Dennis Gonzales, PhD

THEOLOGY AND SPONSORSHIP: Fr. Charles Bouchard, OP, STD

HEALTH PROGRESS www.chausa.org WINTER 2023 3

Maintaining Identity and Inclusivity in Catholic Health Care

JOHN O. MUDD, JD, JSD, and JOHN SHEA, STD Consultants on Catholic Leadership Formation Programs

In Catholic health care, an ever-changing workforce can present new opportunities to enhance and preserve its identity and culture. This endeavor — to tie one’s calling with the ministry’s mission — can, however, invite new challenges, especially when welcoming staff with increasingly diverse backgrounds that are both religious and nonreligious. Those who regularly encounter this dynamic know it has no easy resolution.

For the last 20 years, we have grappled with this issue in formation and administrative settings, working with hundreds of Catholic health care leaders. From our experiences, we offer lessons learned on some areas of concern. It is our hope that by continuing this vital conversation, Catholic health care can find new ways to carry on the healing ministry of Jesus.

TWO WRONG APPROACHES

Before offering our suggestions on how to respond to a changing workforce and its beliefs, while still remaining faithful to Catholic health care’s mission and identity, we first want to rule out two approaches that have been proven not to work — based on our time in Catholic health care. The first is trying not to offend those with different beliefs by avoiding language or engaging in practices that might be considered “religious” or “spiritual.” For example, recently a mission leader was asked to give a short reflection to a gathering of donors, but to not say “Jesus.”

The goal of this strategy — what might be called a “watered-down” approach — is to be sensitive. However, this tactic can result in excluding

conversations on topics and traditional practices that are central to the Catholic ministry’s identity.

A second approach is trying to blend the ministry’s mission and values with the dominant secular culture, perhaps even implying that the Catholic and secular cultures are virtually the same.

History is filled with examples of health care and educational organizations that are secular today but were founded within a religious tradition. Their transition from religious to secular was usually not the result of an intentional decision to drop their religious heritage, but rather the cumulative effect of small decisions and shifts in practice that eroded that tradition over time. Ultimately, the decision to become secular became merely a recognition of what had already occurred.

The result of either watering down the Catholic heritage or trying to blend it with secular culture is inevitably the loss of Catholic identity. Over time, the ministry becomes Catholic in name only — an organization that may still deliver quality health care, but is no longer connected with or defined by the Catholic tradition.

Instead of these fruitless approaches, we offer

HEALTH PROGRESS www.chausa.org WINTER 2023 5 LIVING OUR CATHOLIC IDENTITY

three principles to guide how the ministry can be faithful to its Catholic identity while still welcoming into the ministry people from diverse backgrounds.

Principle One: Values Alignment

Everyone who chooses to serve in a Catholic ministry must demonstrate their commitment to the ministry’s values. This is not optional. Only when the ministry holds staff accountable for living up to its values is the ministry itself being faithful to its identity. If a staff member fails to show respect for patients and colleagues, for example, that person does not belong in a ministry that professes the value of respect. Demonstrating a commitment to the ministry’s values does not mean being perfect, but it does mean that the everyday speech and behavior of those who work in the ministry must be in line with the values the ministry professes.

The source of the Catholic ministry’s values is its theological understanding of God, Jesus and the human person. Those with different religious or philosophical backgrounds are free to ground the values in their own traditions. For example, while everyone in the ministry must demonstrate respect for others and excellence in their work, they may base those values on their own philosophical or religious understanding. A Buddhist and a secular humanist will ground the values of compassion and respect differently. What is essential is that they demonstrate the values in their words and actions.

and experience? Similarly, the ministry’s performance evaluation process should assess whether employees’ words and actions are consistent with its values, and, if they fall short, it should have effective improvement plans and respectful ways to separate those who fail to improve.

It can be challenging to deal with a person who is failing to uphold the ministry’s values but who otherwise has valuable skills. The temptation is to overlook where the person exhibits deficits in the values of the ministry to retain their other contributions. Yet, if some staff get away with unacceptable behavior, that tells others the ministry doesn’t really care, and a “staff infection” spreads. On the other hand, when the ministry makes clear that everyone, even high-profile people, must demonstrate the values, the message also spreads that this ministry walks its talk and is faithful to its identity.

Principle Two: Respect

To ensure that all are committed to the ministry’s values, its hiring processes should include a focus on them and help those who are hiring determine if candidates have demonstrated values like respect, integrity, compassion and excellence. They should ask themselves: Is there evidence of those values shown in the person’s life

Those who choose to work in the Catholic ministry must show respect for its Catholic tradition and heritage, regardless of their own beliefs. When a person with different beliefs accepts the invitation to work in a Catholic ministry, it is like visiting the home of someone from a different culture. If the invitation is accepted, the guest is expected to respect the host’s culture. The same would be expected of Catholics who choose to work in a Jewish or Adventist hospital. For those working in a Catholic ministry, respect for its tradition includes participating in practices like reflections before meetings, celebrations of milestones in the ministry’s history, and orientation and educational programs that explain its heritage. Respect extends in a special way to the ministry’s organizational and ethical principles. One does not need to personally agree with the ministry’s principles and positions, but must show respect for them, and, consistent with their responsibilities, must follow them.1

Principle Three: Welcoming Diverse Traditions

The third principle is the reciprocal of the first two — the ministry must demonstrate respect for the diverse backgrounds of its staff. The model is Jesus welcoming everyone, including outsiders.

6 WINTER 2023 www.chausa.org HEALTH PROGRESS

Demonstrating a commitment to the ministry’s values does not mean being perfect, but it does mean that the everyday speech and behavior of those who work in the ministry must be in line with the values the ministry professes.

LIVING OUR CATHOLIC IDENTITY

Welcoming all who work in the ministry means at the outset not suggesting any effort to convert them. While it is essential to explain the tradition and heritage of the ministry in which they work, it must also be made clear that the ministry respects their beliefs and does not intend to proselytize or indoctrinate them.

In a formation program for senior executives, a question was asked of every group: “What do you not want to happen in this program?” The number one response in every cohort was, “No proselytizing.” The deep-seated fear was that the Catholic faith-based organization would try, in one way or another, to make converts. The prevalence of this suspicion suggests it has to be explicitly rejected.

A welcoming attitude can be demonstrated in many ways. One way is to show how the Catholic tradition, its stories, language and practices share elements with other traditions. When describing the value of compassion, for example, the ministry’s stories of compassion may be complemented with stories from other traditions. Jewish, Sufi and Buddhist traditions — to name a few — are rich with spiritual teachings and stories. Incorporating them shows a welcoming attitude and how the Catholic tradition shares values with others.

emphasis and why it is central to the ministry’s work.

Another way to show respect for those with different backgrounds is to avoid using “insider” language. Like others in the health care world — for example, clinicians, information technology specialists and accountants — Catholics have their own specialized terms. But using insider terms leaves some outside of the conversation and can generate confusion and misunderstanding. In explaining the Catholic tradition, it is essential to use language that is understandable and tailored to the role of the listener. A floor nurse may need to understand only a few Catholic terms, whereas an executive will need to understand and be able to use many.2

While it is essential to explain the tradition and heritage of the ministry in which they work, it must also be made clear that the ministry respects their beliefs and does not intend to proselytize or indoctrinate them.

A similar approach can be used in explaining the centrality of the Catholic social tradition. The newcomer may never have heard of any “social tradition,” much less one that is Catholic. It can help to start the explanation with what is familiar: all clinical professions share the humanitarian tradition of providing excellent, compassionate care and respecting patients, regardless of their personal or economic status. This humanitarian tradition includes working for the common good, or, as expressed in the U.S. Constitution, promoting “the general Welfare.” Religious traditions of the East and West also foster respect and care for others, especially those who are vulnerable. When explained in the context of humanitarian or other religious traditions, the Catholic social tradition becomes less mysterious and more like the Catholic dialect of a language newcomers have already heard. Starting with what is familiar also makes it easier to highlight the Catholic social tradition’s areas of

A number of words Catholics commonly use need explaining to those new to the ministry. Some examples include: What is a sister? (Few entering Catholic health care today have known, much less worked with, a Catholic sister.) What is a congregation, religious order, superior, province, provincial council or a charism? What is a layperson, bishop, archbishop, diocese or a hierarchy? What is a ministry, sponsorship or sponsor? What is canon law, the Vatican, a dicastery, a public juridic person, an ecumenical council or Vatican II? What are encyclicals or the ERDs, and what does preferential option for the poor, subsidiarity, and, more recently, synodality mean?

Words like these can be translated into more familiar terms. For example, an order of sisters’ “province” or a church “diocese” might be translated as a “region” or “geographic territory”; “canon law” as “church law”; a “public juridic person” as a “church corporation”; or a “dicastery” as a “Vatican department.” As with any translation, nuances from the original may be lost, but the listener will better understand the concept and will appreciate being welcomed into the conversation,

HEALTH PROGRESS www.chausa.org WINTER 2023 7

not left wondering what is being said.

Some of the ministry’s practices will also be unfamiliar to a newcomer. The practice of starting meetings with a reflection may be seen at first as a formality, something like singing the national anthem before a ballgame. Explaining that the reflection is a time to pause, be fully present, and connect the meeting with the mission and values can overcome the misinterpretation. The newcomer can learn to appreciate that the reflection should not be simply listening to a few pious words or a management quotation, but a time to consider the “why” of the work before diving into the “who, what, where and when.”

Catholic ministries have found creative ways to welcome those with different traditions. For example, when a Catholic system assumed ownership of a hospital serving a predominantly Jewish community, the hospital’s dedication ceremony included local rabbis placing mezuzahs at the entrances to patient rooms along with chaplains placing the traditional crosses. Another Catholic hospital set aside a special room where its Muslim staff and visitors could pray. Catholic hospitals have found ways to connect regularly with local religious leaders by inviting them to engage with the ministry and to teach hospital staff about cultural sensitivities of patients and ways to honor their healing and end-of-life customs. These are all ways the ministry maintains the interfaith openness of its Catholic identity.

The challenge of maintaining Catholic identity while being welcoming also arises when a Catholic ministry enters a close relationship with an organization that is not Catholic. While this complex topic is beyond the scope here, there is a parallel challenge of ensuring that the partner organization is committed to the values of the Catholic ministry and, if the Catholic identity is intended

to remain, that the ministry’s practices are not diluted or lost because of the relationship.

CONCLUSION

When the founding communities of sisters began to transfer the leadership of their ministries to laypersons more than a generation ago, some doubted that the ministries could remain Catholic without sisters at the helm. The widespread development of orientation and formation programs, along with maintaining cultural practices, have proven effective in keeping Catholic identity and heritage alive. An ongoing challenge is to engage Catholic health care’s increasingly diverse leaders and staff so they feel ownership of their ministry’s Catholic heritage and share the commitment to pass it on.

JOHN O. MUDD served as system mission leader for Providence Health & Services (now Providence St. Joseph Health) before retiring in 2016 and continued to assist with Providence St. Joseph Health’s formation programs.

JOHN SHEA is a consultant to faith-based organizations, dioceses and parishes, and provides theological, mission and formation services. He is working with Providence St. Joseph Health on Forming Formation Leaders and the Community of Formation Practice.

NOTES

1. Chad Raith, “How to Strengthen Catholic Identity in a Diverse Workforce,” Health Progress 102, no. 2 (Spring 2021): 63-68, https://www.chausa.org/publications/ health-progress/archives/issues/spring-2021/how-tostrengthen-catholic-identity-in-a-diverse-workforce.

2. Framework for Ministry Formation (St. Louis: Catholic Health Association, 2020), https://www.chausa.org/ store/products/product?id=4363.

8 WINTER 2023 www.chausa.org HEALTH PROGRESS

MINISTRY

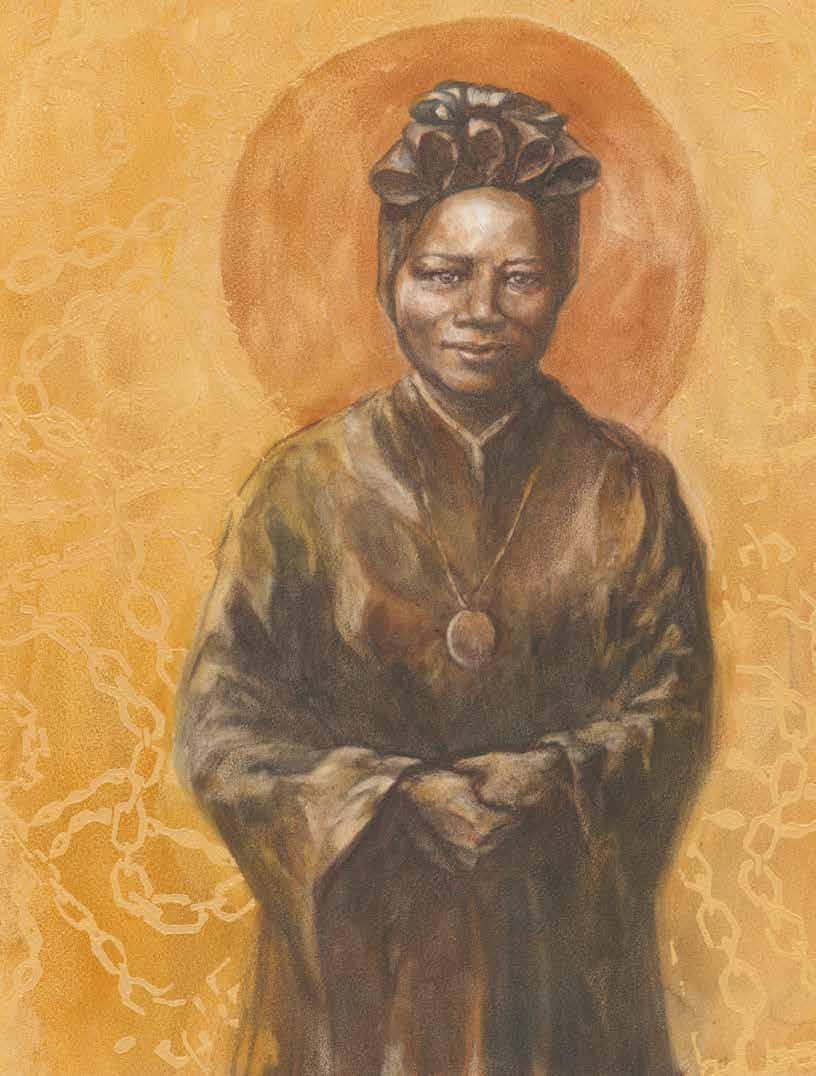

FOR THE CATHOLIC HEALTH

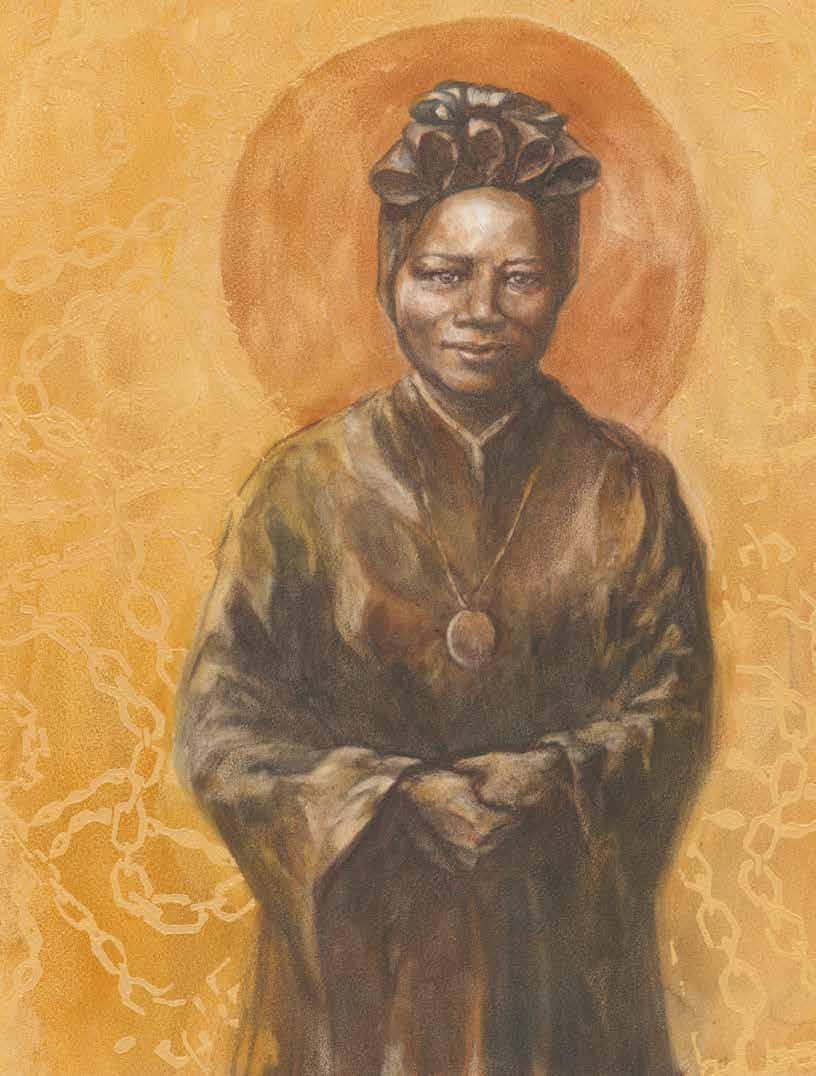

INSPIRED BY THE SAINTS CONTEMPLATIONS

A series of huddle cards depicting the lives of seven saints who represent the core commitments of CHA’s Shared Statement of Identity. Featuring original artwork from Lydia Wood, St. Louis-based artist and activist. Visit chausa.org/saints to order your cards and accompanying audio files.

ST. JOSEPHINE BAKHITA

ST. JOSEPHINE BAKHITA

LIVING OUR CATHOLIC IDENTITY

LIVING OUR CATHOLIC IDENTITY

Harnessing Our Power Through Charism

FR. JOSEPH J. DRISCOLL, DMin

He’s 50 years old. It’s the 1960s. A white Catholic priest is sent as pastor to St. JohnSt. Hugh’s Church in Roxbury, a small Black Catholic community in Boston’s inner city. He remembers well the hot summer day when his Baptist neighbors across the street invited him to their porch for a tall glass of cold lemonade.

Smiling in the retelling of the story years later, the priest, Fr. John Philbin, says, “I knew that with that invitation, I was no longer an outsider, but had been now accepted by my neighbors.”

Rocking back and forth in the porch chairs during the leisurely conversation that day, his neighbor suddenly turned to Fr. John and said, “You know, I know where you get your power from.”

Smiling, curious and somewhat amused, the priest replied, “You do?”

settings ever venture such a statement?

Even more telling, have we ever in the Catholic health ministry asked ourselves the question: Do we know where we get our power from?

Our powerhouse is the “real presence” of the Holy Spirit and a unique gift to a founder of a ministry that meets a need in specific times and circumstances that attracts others.

“Yes,” his neighbor said, pointing to the rectory across the street and the chapel’s bay windows. “From that box over there.”

His neighbor explained that he could see Fr. John sitting in the chapel every morning with his eyes closed, saying his prayers before he went out to do his day’s work.

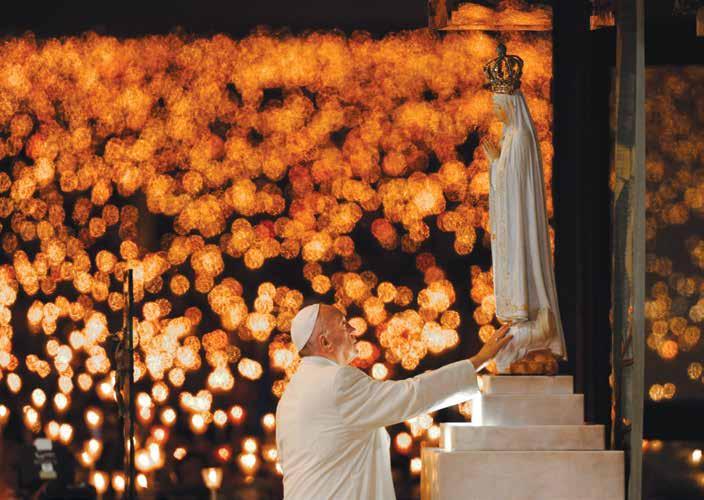

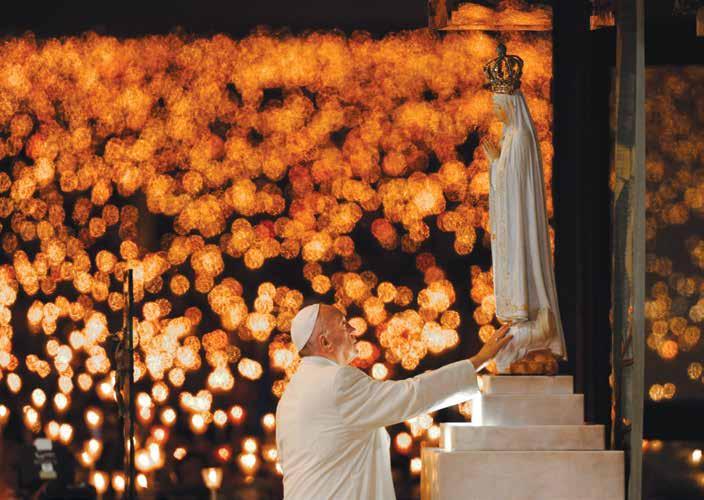

The box, the “powerhouse,” was the tabernacle where the Blessed Sacrament was reserved. In the Catholic tradition, we believe that the real presence of Christ is in the consecrated hosts. Not just symbolically, but Christ truly present sacramentally in his body and blood.

CHARISM AS SOURCE AND POWER

“I know where you get your power from.”

Would the people coming into our ministry

Let’s be clear. We do not get this from our mission, values or vision. Those are all after the fact. Those statements are our reflection upon, discernment about, and articulation of an experience with the Divine power. A Divine power initiates a particular ministry and mission from a time past, sustains both in the present, and promises that ministry and mission in a future, yet unknown, time.

Our “box” is instead the “charism.” Our powerhouse is the “real presence” of the Holy Spirit and a unique gift to a founder of a ministry that meets a need in specific times and circumstances that attracts others.

And this presence still attracts others — and continues to do so in specific times and circumstances.

HEALTH PROGRESS www.chausa.org WINTER 2023 11

Charism, in the biblical and ecclesial tradition, is not generic. Charism is unique and specific to a story. No more than the Christ, the promised Anointed One of Israel, was generic, but rather born — and given the name Jesus in historical and narrative accounts — in a Jewish family in Palestine and in a specific time and circumstances.

This is an important point because presently, from Rome to some of our ministries here in the U.S., there are conversations about the possible emergence of a new charism generalized as “Catholic health care.” This use of the notion of charism is not supported by the tradition.

All our ministries share in common this healing ministry of Jesus Christ. Charism, however, is the coming of the promised Spirit, the impetus or power to establish these healing ministries of Jesus Christ with specificity, to the time and circumstances, and with particularity, to a spirituality emerging from a founder’s story and faith.

For the Sisters of the Redeemer, for example, this healing power of Jesus is viewed from, and experienced in, the cross. Essentially, the suffering before us in our ministries is united with the suffering of Christ, and the promise of “redemption,” something of worth is going to come out of this suffering, that the founder saw as bringing “life in fullness.”

From Paul’s letter to the Corinthians through to, and culminating with the rediscovery and renewal of charisms at, and following, the Second Vatican Council, these gifts are the real presence of the Spirit initiating, sustaining and promising our ministry and mission. Different perhaps; changed and changing, yes; but as Pope St. John Paul II asserts, even “in this newness, however, the Spirit does not contradict him[her]self.”1

CHARISM AS COMMUNITY SENT ON MISSION

At the end of Vatican II, the bishops writing in Perfectae Caritatis recognized the “wonderful variety of religious communities” and the way the gifts “differ according to the grace which is allotted to them.”2, 3 This diversity of gifts is represented in all the ways the Spirit initiates, sustains and promises a ministry and mission that meets the needs of God’s people, and in our case — in Catholic health care — those who are sick, suffering and dying.

Unique and particular to each institution’s founding and emerging story, charism, a particular gift, is of the one Spirit, and is the power and source of our ministry and mission. Charism is the real presence of the Spirit and the gift — then, now and always.

A charism is invisible, real, alive, active, moving and mysterious. It creates the ministry and discovers and discerns its mission.

Not only in our history, but now, every day, in every way, in every place, where we proclaim and live this ministry as a community sent by the Spirit in mission to the world, charism is present.

The irony in this is that we may have inadvertently undermined the power of charism present in our daily operations by creating our legacy walls and celebrating annually our founder’s feasts memorialized in time past. Charism is not past or passive.

Charism is invisible. Like the wind, it “blows where it wills, and you can hear the sound it makes, but you do not know where it comes from or where it goes; so it is with everyone who is born of the Spirit.” (John 3:8) We experience the charism even as we struggle to articulate this gift we cannot actually see, but true to the Gospel metaphor, we feel it like the wind.

Charism is real, active and moving. Like the Pentecostal experience of that first outpouring of the Spirit, “suddenly there came from the sky a noise like a strong driving wind,” and then there “appeared to them tongues as of fire, which parted and came to rest on each one of them.” (Acts 2:2-3)

This power felt from above was real, and experienced by individuals and the community. It is further described as active power, as they were “all filled with the Holy Spirit and began to speak in different tongues.” This power was then recounted as moving out to others, “devout Jews from every nation under heaven staying in Jerusalem,” for “at this sound, they gathered in a large crowd.” (Acts 2:4-6)

12 WINTER 2023 www.chausa.org HEALTH PROGRESS

Unique and particular to each institution’s founding and emerging story, charism, a particular gift, is of the one Spirit, and is the power and source of our ministry and mission.

LIVING OUR CATHOLIC IDENTITY

And finally, charism is mysterious. We cannot define it, but we can and must describe it.

The founders themselves did not define the ministry. They did not have a strategic plan and map for what would become their ministry and mission. It was first “an experience of the Spirit” that needed time “to be lived, safeguarded, deepened and constantly developed by them in harmony with the Body of Christ continually in the process of growth.”4

Even today, hundreds of years later, some of our present-day leaders of these founding religious communities still work to describe anew the “genuine originality”5 of their charism, while at the same time “scrutinizing the signs of the times and of interpreting them in the light of the Gospel. Thus, in language intelligible to each generation.”6

Mystery is the nature of the Holy Spirit. Ultimately, we cannot define either the Divine or the Divine’s actions in a word-limited sentence. Yet, we can and must describe with human words as best we can while approaching this mystery, and seek to uncover its meaning anew.

To notice, understand and appreciate charism makes more conscious the source of the ministry and the movement in mission. The sharper the awareness, the better the understanding; and the deeper the appreciation, the more it prepares each of us to recognize that this is ultimately God’s work through us. It is God calling us in vocation to this work.

brought forth by a creative and free Spirit. This Spirit brings unity in diversity and creates order out of chaos. These fruits of the charism are core to who we are (ministry) and what we do (mission) in the practical day-to-day.

CHARISM AS DAY-TO-DAY PRACTICALITY

The challenge is for our present-day ministry leaders and frontline staff to notice, understand and appreciate that there “is” an invisible power that moves above, underneath, inside and through the ministry community, and then outside as mission into the world.

This invisible power moves in every aspect of our ministry community, whether in direct care of patients and residents, or institutional structures such as our boards in deliberation, or strategies decided and acted upon at our management meetings. This invisible power is in our care delivery places, in our hallways and parking lots, as well as in our chapels and spiritual practices, everywhere, in every way, every day.

At Redeemer Health in Meadowbrook, Pennsylvania, we have been on a two-year initiative to help all our ministry partners become more aware of the charism in the ordinary, better understand the charism as a real presence in the now, and more deeply appreciate and watch for the charism in the day-to-day work of ministry and mission.

This invisible power is in our care delivery places, in our hallways and parking lots, as well as in our chapels and spiritual practices, everywhere, in every way, every day.

If charism is in fact that which distinguishes us from all other health care, nonprofit and forprofit alike, then it seems the focus on charism is critical for maintaining, enriching and renewing our Catholic identity. We need to consciously and actively go back to the source of our power. This charism is what moves us in our good works through a ministry community in a mission to the world.

We need to point back to God through Jesus’ revelation to us of a powerful love, one that is

Redeemer Health provides health care in Pennsylvania and New Jersey, including an acute care hospital, home health and hospice services, three skilled nursing facilities, personal care, a retirement community, low-income housing, an independent living community, a transitional housing program for homeless families, and multiple homes for intellectually and developmentally disabled adults.

Inspired by, and in response to, the 2019 general chapter of international congregation of the Sisters of the Redeemer — headquartered in Würzburg, Germany — we prioritized this formation initiative on charism. Their resolution mandated “the continued deepening and educating of Sisters and our partners in mission in Redeemer Charism and Spirituality.”7

With the support of the Redeemer leadership, a Redeemer charism and spirituality work group was formed in the fall of 2020 in order to oversee — even guarantee — the integration of charism

HEALTH PROGRESS www.chausa.org WINTER 2023 13

and spirituality in all we do. Assuring maximum buy-in from leadership, our CEO recommended the oversight group consist of two sisters, two sponsor board members, two board of trustee members and two executive leaders (the CEO and mission leader).

Through the group’s work, a program called “Charism Animators of Redeeming Love” has emerged, scheduled to begin in early 2023. It is a one-year program that will consist of 25 participants and begin with an initial retreat, gatherings every other month and a closing integrative retreat. The program’s impact will be measured through qualitative preprogram and postprogram surveys on charism.

The program’s two retreats are core to its effectiveness, as strengthening awareness of the invisible power of charism is a spiritual exercise that needs time and space. Quieting the outside noise allows people to become more sensitive to the inner movements and to the subtle, mysterious ways that we can become more aware of the Divine in and around us, especially in our day-today work in ministry.

Unlike other ministry formation programs, the attempt here is more akin to group spiritual direction, not so much the individual’s path, but the organization’s spiritual journey.

We hope that by heightening spiritual skills such as observation, listening, discernment and deliberation that our leaders will develop a curiosity, and take those skills back into their day-today work: to “sense” the invisible, name the experience and to help others appreciate this is the charism at work.

As these cohorts grow in number, we envision making these opportunities available to frontline staff through 15-minute reflection modules developed to increase this awareness, understanding and appreciation through the entire organization and the communities we serve.

CONCLUSION

As invisible and mysterious as our charisms may be, people who encounter us — staff, patients and residents — have an almost intuitive sense of this power and source in charism. How often do we hear people in our institutions say, “There is something different about coming here,” or, “I

have worked at many facilities, but this one just has a feeling that is unlike the others in which I have worked.”

Wouldn’t it be something to move from intuitive ambiguity of this “difference” to a more conscious and concrete affirmation of who and what it is that is moving through our ministry and mission everywhere, every day and in every way?

One of our sisters recently shared a powerful story that summarizes the power of charism.

During a lunch she had with a 95-year-old resident in assisted living — a long-time benefactor and friend of the ministry — her friend tearfully said to the sister, “I don’t know what it is with your people, but it seems they all have ‘it.’” She went on to ask, “Do they come in with ‘it’? Or do they absorb ‘it’ here? For me, it’s really profound.”

We know the ‘it’ is our invisible, real, alive, active, moving and mysterious charism at work as it was in past times, is now, and always will be.

FR. JOSEPH J. DRISCOLL is director of ministry formation and organizational spirituality for Redeemer Health in Meadowbrook, Pennsylvania.

NOTES

1. Pope John Paul II, Vita Consecrata, section 12, https://www.vatican.va/content/john-paul-ii/en/apost_ exhortations/documents/hf_jp-ii_exh_25031996_ vita-consecrata.html.

2. Second Vatican Council, Perfectae Caritatis, section 1, https://www.vatican.va/archive/ hist_councils/ii_vatican_council/documents/ vat-ii_decree_19651028_perfectae-caritatis_en.html.

3. Second Vatican Council, Perfectae Caritatis, section 8.

4. Sacred Congregation for Religious and Secular Institutes, “Directives for the Mutual Relations Between Bishops and Religious in the Church,” section 11, https:// www.vatican.va/roman_curia/congregations/ccscrlife/ documents/rc_con_ccscrlife_doc_14051978_ mutuae-relationes_en.html.

5. Sacred Congregation, “Directives for the Mutual Relations,” section 12.

6. Second Vatican Council, Gaudium et Spes, section 4, https://www.vatican.va/archive/ hist_councils/ii_vatican_council/documents/ vat-ii_const_19651207_gaudium-et-spes_en.html.

7. “Sisters of the Redeemer General Chapter Resolutions 2019,” Sisters of the Redeemer.

14 WINTER 2023 www.chausa.org HEALTH PROGRESS

Ensuring Quality Care Means Prioritizing the Most Vulnerable

A Q&A WITH DR. ALISAHAH JACKSON

KELLY BILODEAU Contributor to Health Progress

Alisahah Jackson, MD, is the first president of the new Lloyd H. Dean Institute for Humankindness & Health Justice at CommonSpirit Health. She stepped into this role in November 2022 after serving as CommonSpirit’s vice president of population health innovation and policy. As part of her mission to improve health equity, she helped to establish the system’s Vulnerable Populations Council. This interdisciplinary executive leadership group is improving care by creating initiatives to address social determinants of health and to support vulnerable patients across the organization. The 25-member group coordinates with the Vulnerable Populations Care Collaborative, an assemblage of clinical leaders who put these strategic plans into use across the organization, which includes more than 1,000 care sites and 140 hospitals in 21 states. Health Progress recently spoke with Jackson about the council and its goal of promoting quality care.

Can you tell me about the origins of the Vulnerable Populations Council and how CommonSpirit Health addressed vulnerable populations prior to its formation?

One of my responsibilities was to help our system think through how we care for our vulnerable populations. What I found when I got here was that there were so many departments and providers doing great work and taking care of what we may consider vulnerable populations. But it was very siloed. As I learned more and more, I said we really need to have some sort of infrastructure that can bring all these people together: 1) to acknowledge, recognize and celebrate the great work that they are doing; 2) to identify where there are opportunities to align work; 3) to leverage some of those best practices; and then ulti-

mately, 4) to start thinking about how to measure our work, so that we can speak to the outcomes that it is having. That’s how the Vulnerable Populations Council came about.

What was the council’s first initiative?

We realized pretty early on, as the conversations were happening nationally around COVID, that communities of color were disproportionately affected. We were seeing that in our facilities as well as in the national data. So, we educated our communities on that information and other risk factors. People with chronic medical conditions like diabetes and asthma were at higher risk, and we presented that information in a way that was culturally sensitive to those communities that were disproportionately affected.

HEALTH PROGRESS www.chausa.org WINTER 2023 15 LIVING OUR CATHOLIC IDENTITY

We realized that we needed a process to do that. So, we worked with our marketing and communications teams to create material. They vetted it through the Vulnerable Populations Council, making sure that from a health literacy standpoint, it was at a basic reading level, using a lot of graphics and pictures to try to get the information out there.

We also had to create educational materials for our providers as well — that was an ongoing process. We were updating the information as more was coming out from the CDC and other studies. We were updating our providers on that new information.

And then, as the vaccine became available, we recognized that communities that were disproportionately affected were also hesitant to get the vaccine. So, we created a whole vaccineawareness campaign. We went into those communities in a lot of our markets, partnering with trusted community providers and organizations, like churches, universities, and of course, public health departments. It required multiple organizations coming to the table, but getting out of this mindset of always expecting the patient to come to us, the care provider, and instead for us to really get out into the community. We had multiple vaccination events, including drive-through clinics, at community locations, like schools and churches, and at farms with migrant workers. That was extremely powerful, and we were able to serve so many more patients.

How did you track your outcomes?

For COVID, we had a COVID dashboard created by our organization’s quality and data analytics teams and patient-safety leader. We were able to look at everything from hospitalizations to vaccine administration. We could leverage heat maps [graphs that show the values of data represented by a color scale] — actually even look at the zip code level — to see how we were doing. I can’t stress enough the need for collaboration, and having the data to support and validate the work that we were doing.

Are there other council-driven changes that have made a difference in patient health?

Health literacy — clearly that was a big focus as it related to COVID. But we started to realize that we had that same issue across a lot of our different patient-education materials and information. We formed a committee to specifically focus on health literacy across our organization that also includes language services. So, making sure that we have the appropriate resources for language services in the communities we serve, and recognizing that those needs are different for each community.

There are also some things that we focused on standardizing; for example, how we collect information around someone’s preferred language. With the work on COVID, we recognized that we weren’t consistently capturing that information in all of our markets but that it was something we needed to do.

CommonSpirit Health uses a broad definition when defining vulnerable populations, noting that all are vulnerable at times. For the council’s work, Dr. Alisahah Jackson explains they prioritize populations that are systematically excluded, face significant health disparities and are often invisible. These groups include, but are not limited to, communities of color, LGBTQ+ people and those with low health literacy.

Dr. Alisahah Jackson

Dr. Alisahah Jackson

16 WINTER 2023 www.chausa.org HEALTH PROGRESS

How do you collect information about your patient populations?

Information collection is done as a part of the registration process. Our Office of Diversity, Inclusion, Equity and Belonging, which participates in the Vulnerable Populations Council, really took that on. They expanded the work around how we’re collecting race, ethnicity and language data in a consistent, standardized way. One example includes working with our vendors, like those who support our electronic health records, to make sure that those fields are standardized throughout our different systems. And then training our staff on the best practice for allowing the patient to self-identify [or allowing them to choose not to disclose] those characteristics, but also recognizing that we needed to actually train our staff to feel comfortable having that conversation with the patient. We also train them to explain to the patient why we are now being much more intentional about collecting that data.

How has obtaining that type of detailed information helped your organization?

This year we are really leveraging that information to look at some of our quality measures. I think this is what hospitals and health systems should be doing, even though it’s not necessarily a requirement, just yet. I think that will likely be changing as well, given some of the guidelines that you’re seeing from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and other payers. It allows us to do a deeper dive into how we’re doing on quality.

I think that’s important because often when we aggregate data, we may get a false sense of our performance. Without the ability to start to disaggregate that data to look at specific populations, we may not realize that there’s a certain population that, for example, doesn’t have good diabetes control. Or maybe there’s a specific clinic where patients don’t have good diabetes control. Often, I would say it’s more due to process or resource issues versus it being that the doctor is treating that patient with bias. Nine times out of 10, that is not the case. It usually does go back to a system that is perpetuating disparities. So, we have to get to the root cause of what’s happening in that system, in that process, that’s contributing to the problem. That’s how we’re now able to leverage the data around race, ethnicity and language.

LIVING OUR CATHOLIC IDENTITY

Have you learned anything surprising from your data?

I do think that for some of my colleagues, there have been eye-opening moments. One has been assuming that processes are working as designed. If you actually go and do the deep dive or an audit, you often find that the process isn’t necessarily working as designed. One example I can give is around blood pressure control. In some offices, we saw a discrepancy around blood pressure control for a certain patient population. So, we dove deeper into what was going on. There’s a best practice around taking blood pressure. If a patient comes into an office and their blood pressure is elevated, you let them sit in the office for about 10 minutes in the exam room and let them kind of calm down. Then, you go back in and recheck it. And what we found is that the medical assistants saw significant turnover. Even though they had received training on this, they weren’t consistently doing that blood pressure recheck. That’s a process issue. We had to retrain them and make sure that providers knew to look for the documentation of a second blood pressure if it was noted as elevated, and if not, rechecking it themselves. And that actually improved some of the numbers that we were seeing. So, I think that’s just an example of what you can do from a quality improvement standpoint if you’re looking at the data in a different way.

Do you think that the council will help your organization to improve outcomes among vulnerable patients?

I definitely do because this council is specifically focused on caring for the vulnerable and making sure that we keep that front and center as we do our work. For us, it’s a part of our mission and remaining true to it. I think having this space, where people feel comfortable and safe in bringing up some of their concerns, has been really helpful. I want to emphasize that, because I think sometimes those spaces aren’t created for these types of conversations. I do think that’s been a huge driver for some of the initiatives and programs, and, quite frankly, the outcomes that we’ve now been able to look at on the organizational level.

KELLY BILODEAU is a freelance writer who specializes in health care and the pharmaceutical industry. She is the former executive editor of Harvard Women’s Health Watch. Her work has also appeared in The Washington Post, Boston magazine and numerous health care publications.

HEALTH PROGRESS www.chausa.org WINTER 2023 17

Earn

your advanced degree in Healthcare Ethics

Duquesne University offers an exciting graduate program in Healthcare Ethics to engage today’s complex issues.

Courses are taught face-to-face on campus or through online learning for busy professionals.

The curriculum provides expertise in clinical ethics, organizational ethics, public health ethics and research ethics, with clinical rotations in ethics consultation.

Doctoral students research pivotal topics in healthcare ethics and are mentored toward academic publishing and conference presentation.

MA in Healthcare Ethics (Tuition award of 25%)

This program requires 30 credits (10 courses). These credits may roll over into the Doctoral Degree that requires another 18 credits (6 courses) plus the dissertation.

Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) and Doctor of Healthcare Ethics (DHCE)

These research (PhD) and professional (DHCE) degrees prepare students for leadership roles in academia and clinical ethics.

MA Entrance – 12 courses

BA Entrance – 16 courses

Graduate Certificate in Healthcare Ethics

This flexible program requires 15 credits (5 courses). All courses may be taken from a distance. The credits may roll over into the MA or Doctoral Degree (PhD or DHCE).

Questions?

or chce@duq.edu

412.396.4504

duq.edu/globalhealthethics

LIVING OUR CATHOLIC IDENTITY

A Guide to Maintaining Clinical Trial Integrity in Catholic Health Care

PUKAR RATTI, CIM, CCRP, FACMPE System Director, Research and Academics, CHRISTUS Health STEVEN J. SQUIRES, PhD, MEd Vice President of Ethics, CHRISTUS Health

Those who don’t do clinical research in Catholic health care settings may hope a program can grow “despite” its faith-based setting. Those of us who do this work in faith-based organizations realize these settings can be truly beneficial and structured to allow ethical and significant research programs to grow and thrive. At the CHRISTUS Institute for Innovation and Advanced Clinical Care, we infuse Catholic identity, Church teaching and mission — along with federal regulations and clinical research operations — into all of the institute’s operational processes. The impact of this integration goes far beyond regulatory compliance for those involved in CHRISTUS Health’s nearly 700 active clinical studies and more than 10,000 participants.

This standardization and incorporation of mission and ethics into the program’s operations fuels the growth of CHRISTUS Health’s clinical research programs. The health care system has developed informational resources and makes subject matter experts available to sponsors and scientific investigators to ensure research protocols and practices are appropriate to a faithbased setting. In fact, the average time from a new study’s submission to the research central office until its launch at CHRISTUS Health is less than 75 days, compared to the industry’s average of 90 days. We believe that our approach would be useful to others in Catholic health care, and to mission- and values-driven secular health care. Our hope is that others find insights from this model and replicate its components for their clinical research programs. Throughout the COVID-19

pandemic, those working in health care so often saw how clinical research advances life-saving treatments.

ABOUT THE INSTITUTE

Driven by the mission to extend the healing ministry of Jesus throughout its work, CHRISTUS Health offers coordinated and organized advanced clinical care and research for patients through its Institute for Innovation and Advanced Clinical Care. The institute is an integrated, multidisciplinary enterprise that provides strategic planning, expert consultation and catalyst support services for clinical research growth across the health system. It includes a system office that delivers essential services to conduct and support research, such as an institutional review board, compliance, research education,

HEALTH PROGRESS www.chausa.org WINTER 2023 19

finance and reporting, and pre- and post-award services for clinical research studies.

The participating ministries of CHRISTUS Institute for Innovation and Advanced Clinical Care are organized across the United States into five geographic regions: 1) Louisiana, 2) Southeast Texas, 3) South Texas, 4) Northeast Texas and 5) New Mexico. Each of these five research hubs is led by a research leader — who reports to one system research executive. This forms a hub-and-spoke organizational chart, where one major location serves as a central point for coordinating clinical research initiatives to and from other locations. Some of the major clinical research focus areas at CHRISTUS Health include oncology, cardiology, electrophysiology, pediatrics, neurology, COVID19 and wound care.

ENSURING ERD INTEGRATION INTO CLINICAL RESEARCH

To affirm integration of the Ethical and Religious Directives for Catholic Health Care Services (ERDs) into relevant clinical research matters, the institute created and deployed a multi-integrated operating model. (See graphic on page 21). To ensure its success, relevant stakeholders were involved during each step. Internally, we refer to these stages through the acronym “FIRE CONTROL.”

1. Feasibility Review

The first step in the process is the feasibility review, which is an internal review that involves research leaders, local mission leaders, senior leadership team members and other department leaders who use a feasibility analysis tool to assess together if the clinical research project is an operational fit for the ministry. The tool captures and documents responses to a series of questions in six major categories: mission alignment; patient population and recruitment; study design; local operations and support; contract and research coverage analysis; and budget.

The review’s mission alignment section allows each evaluator an early opportunity to assess whether the clinical research project abides by the ERDs by reviewing elements that may conflict with Catholic teaching. Examples include sterilization, some types of gene therapy or genetic modification of human tissue, or use and/ or distribution of contraception. This section also

checks if the project plans to exclude research participants with limited English proficiency, unless clinically justifiable. If any aspects of research are identified as not aligning with the ERDs or Catholic teaching, identity or mission during feasibility assessment, it is either immediately rejected or returned for appropriate revisions. For instance, a sponsor requested CHRISTUS Health participation in a clinical trial for a medicine used to treat infertility. The research protocol required sites to keep and distribute contraceptives. CHRISTUS’ clinical research institute deemed the study ‘not feasible’ after failing to find an appropriate alternative.

2. Informed Consent Form Review

For some medium- to high-risk clinical research projects, a pregnancy prevention clause may be necessary within the research informed consent form for those initiatives that require disclosure per policies set forth by the Office for Human Research Protections and/or the Food and Drug Administration (FDA).1, 2 A research informed consent form is typically a description of clinical investigation, risks, benefits, participation fees, confidentiality, compensation and/or medical treatment for injury, voluntary participation and more. CHRISTUS Health’s institutional review board requires that the standard language for pregnancy prevention be used in all applicable research-informed consents, in addition to all parental permission and participant agreement forms for subjects aged 13-17 years.

As a Catholic ministry, CHRISTUS Health provides standard clauses that avoid unethical actions within CHRISTUS Health (moral agency) or associated with CHRISTUS Health (moral cooperation) by emphasizing appropriate birth regulation means and not specifying certain pregnancy prevention means via inclusion of approved template language. In 2016, we developed a series of seven standard clauses — ordered from most preferred to least preferred — to allow flexibility for our clinical research sponsors and investigators. After review in 2021, our mission and ethics leaders developed two standard clauses in English and Spanish in lieu of the prior seven standard clauses to capture pregnancy precautions during and after study. If any adaptations of the standard clause result, they require reapproval by mission and ethics leaders before the clinical

20 WINTER 2023 www.chausa.org HEALTH PROGRESS

research project can be submitted for ethical and board review.

3. Institutional Review Board/Ethics Review

Under FDA and Department of Health & Human Services regulations, all human subject research must be reviewed by an institutional review board prior to its start. Furthermore, the board should consist of reviewers with both scientific and nonscientific backgrounds, and not affiliated with the institution to ensure a balanced scientific and ethical review that protects participants’ rights, integrity and welfare.3, 4

CHRISTUS Health’s institutional review board consists of additional reviewers, such as ethicists and mission leaders, to ensure alignment with Catholic teaching, the ERDs and protection of the most vulnerable populations (such as children, elderly, those who are poor and racial minorities). Additionally, to better serve our communities, CHRISTUS Health has established several academic partnerships — both Catholic and nonCatholic. By combining our strengths on research, these academic partnerships enable our communities more access to research participation without compromising our identity or integrity.

4. Contract Review

As part of launching a clinical research project, CHRISTUS Health enters into contractual agreements with all legal parties involved. These agreements allow for the legal exchange of clinical research funding, materials and data between the two parties, and memorializes the rights and obligations of each party. In each clinical research agreement at CHRISTUS Health, the parties are required to acknowledge that 1) CHRISTUS Health is a faith-based organization, 2) all operations at CHRISTUS Health are in accordance with the ERDs, as interpreted by a local bishop, and 3) CHRISTUS Health’s operations — in accordance with the ERDs — and its principles and beliefs of the Roman Catholic Church are a matter of conscience. If CHRISTUS Health were to determine that any aspect of an arrangement would violate the ERDs, the options are to work together in good faith to resolve or terminate participation. Secondly, our health system ensures that each clinical research agreement is accompanied with a fair reimbursement and payment schedule for services rendered to remain

Research Review for Mission Alignment A look at the stakeholders responsible for each aspect of CHRISTUS Health’s “FIRE CONTROL” operating model. FEASIBILITY REVIEW • Regional Research Leaders • Research Executive • Ethics Executive • Mission Leaders FIRE CONTROL OPERATING MODEL COMPONENTS • Stakeholders INFORMED CONSENT FORM REVIEW • Regional Research Leaders • Research Coordinators and Nurses • Institutional Review Board • Ethics Executive • Research Sponsor INSTITUTIONAL REVIEW BOARD/ ETHICS REVIEW • Institutional Review Board CONTRACT REVIEW • Legal Counsel • Contracts Analyst • Research Sponsor POLICIES AND STANDARD OPERATING PROCEDURES • Research Executive • Institutional Review Board Staff INITIAL AND ONGOING EDUCATION • Research Executive • Institutional Review Board Staff LANGUAGE ACCESS SERVICES • Research Coordinators and Nurses • Language Access Service Vendors • Health Equity, Diversity and Inclusion Department Source: CHRISTUS Health HEALTH PROGRESS www.chausa.org WINTER 2023 21 LIVING OUR CATHOLIC IDENTITY

responsible stewards of health care resources. Thirdly, we aim for favorable language in clinical research agreements for our patients (especially those in vulnerable situations) to ensure that there is a clear arrangement on how patients will be compensated in the rare event of a clinical research-related injury.

5. Policies and Standard Operating Procedures

Clearly written policies and standard operating procedures eliminate uncertainty, ambiguity and/ or misinterpretation about how to apply the ERDs in clinical research. These allow CHRISTUS Institute for Innovation and Advanced Clinical Care to follow standardized processes and reduce errors. Some of the clinical research policies in effect cover topics such as research-informed consents, language access services and institutional review board, to name a few.

6. Initial and Ongoing Education

CHRISTUS’ clinical research institute is committed to providing comprehensive initial and ongoing education opportunities to its clinical research workforce, medical residents and fellows, institutional review board members and physician investigators involved in its clinical research. As part of this effort, the institute rolls out an annual lecture series program on good clinical practices. Subject matter experts give bimonthly presentations on relevant and timely topics, including lectures specific to Catholic teaching, such as the “ERDs and Clinical Research” and “Ethical Research.”

7. Language Access Services

Access to language services is not only about potential research participants, but also for all those impacted by the study’s clinical research results and validity. Excluding groups with limited English proficiency from studies leads to biased and exclusionary results, not only with medications and treatments, but clinical protocols and algorithms.5 As noted by specific directives in the ERDs, duties to the community and vulnerable persons compel Catholic health care to minimize any communication barriers to prevent further exclusion (beyond those of the study) and the growth of any existing vulnerabilities.6

Secular rules are in unison with faith-based commitments. Since 1964, the United States has

passed a series of acts, laws, executive orders and regulations to enhance language access services to all in health care. Provisions in federal government and FDA regulations require investigators to obtain informed consents in a language that is understandable to the clinical research participant or their legally authorized representative.7, 8

The CHRISTUS Institute for Innovation and Advanced Clinical Care ensures fair and equitable selection of volunteer research subjects for its clinical trials and research projects and therefore promotes health equity, diversity and inclusion. This commitment encourages potential clinical research subjects who altruistically volunteer despite any English-speaking barriers, including non- or limited-English proficiency, deafness and hearing difficulties.

We have set the tone for reliable and consistent language access services at the system level for all our patients by establishing a system policy, adopting standardized processes and retaining credible vendors. We provide our clinicians and other team members with the tools necessary to deliver language access services through: 1) live/ onsite professional interpretation, 2) qualified bilingual staff, 3) document translation, 4) video remote interpretation and 5) over-the-phone interpretation.

In addition to these day-to-day steps related to clinical care, CHRISTUS Health requires the fulllength informed-consent document to be translated into the subject’s language. We also use a CHRISTUS-approved bilingual witness for clinical research studies with linguistic distribution of more than 1,000 study subjects, or more than 5% of the study’s subject population (whichever is greater). In addition, we use a translated shortform consent with a CHRISTUS-approved bilingual witness for clinical research studies with linguistic distribution of less than 1,000 study subjects or lower than 5% of the study subject’s population (whichever is smaller). These services are available at no cost to clinical research subjects and their legally authorized representatives. Per our policy, we do not allow minors or family members of patients to serve as interpreters during the informed-consent process.

As a result of the use of professional interpreters and translators in clinical research, many benefits emerge, including the assurance of clinical research participants’ understanding,

22 WINTER 2023 www.chausa.org HEALTH PROGRESS

LIVING OUR CATHOLIC IDENTITY

upholding the quality and efficiency of interpretation services, and reducing or eliminating clinical research participant safety risks to study participants due to misinterpretation.

MODEL’S IMPACT ON CLINICAL RESEARCH

Having mission- and ethics-based standards that go beyond federal regulations and expanding clinical research programs are not mutually exclusive. Faith-based or not, it is imperative that all clinical research institutions follow applicable federal regulations. Sometimes these regulations may conflict with the Church’s teachings. Examples include pregnancy prevention methods, gene therapy research and selection of subjects. However, our FIRE CONTROL operating model helps to maintain the delicate balance between the ERDs, federal regulations and clinical research operations.

CHRISTUS Health’s clinical research institute has expanded significantly while hardwiring mission, identity and teachings rooted in sources such as the ERDs. Since the application of our innovative operating model, the total number of active clinical research studies has more than doubled in the last five years, including a growth of 28% in fiscal year 2021 (compared to the previous fiscal year) — despite the period’s height of COVID-19 cases — and a continued growth of 12% in FY2022, so that the system is involved in almost 700 studies a fiscal year. Furthermore, the number of our research participants per fiscal year has consistently been between 10,000 and 15,000 since FY2017, and we continue to recruit from diverse populations.

CONCLUSION

By sharing our FIRE CONTROL operating model, we hope others may draw from it to find new ways to advance the care provided through clinical research. By using clinical research that is innovative, ethical and financially responsible, not only can we improve the experience of research participants and the potential study outcomes, we can help to ensure the human dignity of every patient.

PUKAR RATTI is system director of research and academics at CHRISTUS Health in Irving, Texas. STEVEN J. SQUIRES is vice president of ethics at CHRISTUS Health in Irving, Texas. He was recognized as a member of the CHA 2016 class of Tomorrow’s Leaders.

NOTES

1. “2018 Requirements (2018 Common Rule): 45CFR46.116,” U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, January 2019, https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/ regulations-and-policy/regulations/45-cfr-46/ revised-common-rule-regulatory-text/index.html.

2. “CFR–Code of Federal Regulations Title 21: 21CFR50 Subpart B,” U.S. Food and Drug Administration, July 2022, https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/ cfdocs/cfcfr/CFRSearch.cfm?CFRPart=50.

3. “Title 45: Part 46 — Protection of Human Subjects,” Electronic Code of Federal Regulations, July 2018, https://www.ecfr.gov/on/2018-07-19/title-45/ subtitle-A/subchapter-A/part-46.

4. “CFR–Code of Federal Regulations Title 21,” U.S. Food & Drug Administration, July 2022, https:// www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfcfr/ CFRSearch.cfm?CFRPart=56.

5. Gau Bugeja, Ajay Kumar, and Arup Banerjee, “Exclusion of Elderly People from Clinical Research: A Descriptive Study of Published Reports,” British Medical Journal 315, no. 7115 (October 1997): 1059, https:// doi.org/10.1136/bmj.315.7115.1059; Susan Reverby, “Inclusion and Exclusion: The Politics of History, Difference, and Medical Research,” Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 63, no. 1 (January 2008): 103-13, https://doi.org/10.1093/jhmas/jrm030; Darshali Vyas, Leo G. Eisenstein, and David S. Jones, “Hidden in Plain Sight — Reconsidering the Use of Race Correction in Clinical Algorithms,” The New England Journal of Medicine 383, no. 9 (August 2020): 874-882, https:// doi.org/10.1056/NEJMms2004740.

6. United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, “Directive 3” and “Directive 8” in The Ethical and Religious Directives for Catholic Health Care Services: Sixth Edition (Washington, DC: United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, 2018).

7. “Title 45,” Electronic Code of Federal Regulations. 8. “Title 21,” U.S. Food & Drug Administration.

HEALTH PROGRESS www.chausa.org WINTER 2023 23

CONTENTS INCLUDE: Complete searchable version of the Ethical and Religious Directives for Catholic Health Care Services Glossary of important ethics terms Collection of relevant articles and resources addressing important clinical issues in Catholic health care

Info at Your Fingertips! FOR CHA MEMBERS CHA’S ETHICS APP is a valuable collection of ethics information for clinicians who provide patient care and for the ongoing education of ethicists, mission leaders, ethics committees and clinicians in Catholic health care. To download the app, visit www.chausa.org/EthicsApp (member login required)

Ethics

Unprecedented Times Call for Revamped Leadership Skills

MARTIN SCHREIBER, EdD Vice

“A health care organization that is efficient and capable of addressing inequalities cannot forget that its raison d’être … is compassion ... .” 1

— Pope Francis

The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated a reimagination of our current models of health care and intensified the focus on health equity for those who are poor and vulnerable, while bringing with it a cadre of additional and complex leadership challenges. Successful leadership in this age of health care requires a renewed leadership focus on mission, purpose and vision, along with updated strengths and skills to best advance the healing ministry of Jesus.

In response to these challenges, Providence is preparing leaders in new ways, beginning with a commitment to individual self-discovery, compassion and whole-person leadership. As noted by author and psychiatrist Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, “People are like stained-glass windows. They sparkle and shine when the sun is out, but when the darkness sets in, their true beauty is revealed only if there is a light from within.”2 Advancing Catholic health care’s mission will require us to think differently. At Providence’s Mission Leadership Institute, we think of individuals on a pilgrimage with caregivers walking a path to selfdiscovery. To support leaders’ introspection, this work toward personal growth takes some nontraditional approaches to break down the walls that protect our weaknesses and fears, to recognize our own biases and to confront our vulner-

abilities. This extraordinary time in health care has made us realize that an honest examination by leaders of their internal inventory can help build their personal resilience. We believe in aiding them as they develop a wealth of resources. By drawing upon these helpful tools, our leaders can be better equipped to support and motivate others.

SHAPING LEADERS FOR HEALTH CARE’S FUTURE

During the volatile period triggered by the pandemic, Catholic health care systems experienced a variety of unprecedented events: the need to rapidly and skillfully care for unusually high volumes of patients; to adapt to immediate technological changes; and to coordinate rapid responses to urgent health inequities. A level of “mission fragility,” a genuine concern about being

President, Providence Mission Leadership Institute, Providence St. Joseph Health

President, Providence Mission Leadership Institute, Providence St. Joseph Health

HEALTH PROGRESS www.chausa.org WINTER 2023 25

LIVING OUR CATHOLIC IDENTITY

LIVING OUR CATHOLIC IDENTITY

able to meet needs and to respond to patients and other care providers in the way we are called to do, was introduced. It warranted an urgent redesign of leader preparedness. Leadership success demanded quicker responses, broader communication skills, engagement of an entire campus and a whole-person sensory awareness. This work included approaches developed as a result of the ongoing overstimulation and burnout experienced by health care professionals during the pandemic. One way to protect against that overstimulation was to bring back the necessary focus on one’s five basic senses and intuition like never before (what we call “5S + leadership”).

Based on the changing circumstances of health care, we began to reimagine how we train leaders, pivotal to securing the future of Catholic health care. A new style of leadership became necessary: one that is more agile, more connected and responsive to constant fluctuations in health care environments, and better facilitated by reimagined strategy and leadership training centered on the mission.

TRANSFORMING LEADERSHIP TRAINING AT PROVIDENCE

human life. This includes respecting the principle of subsidiarity — which calls us to empower decision-making to those most directly impacted — and meeting the needs of those who are poor or uninsured, especially children, pregnant women, immigrants and other vulnerable populations.3 In addition, the Catholic tradition of health care connects social justice with the delivery of care. Carolyn Woo, PhD, who holds the role of Distinguished President’s Fellow for Global Development at Purdue University, was one of the institute’s keynote speakers on the topic of the whole

Leadership success demanded quicker responses, broader communication skills, engagement of an entire campus and a whole-person sensory awareness.

person. She said: “What I say and what I do must align.”4 She motivated us to look beyond our current crisis and rise toward a new dawning.

The leadership training redesign at Providence was initiated in June 2020, drawing from the vision of Dougal Hewitt, chief mission and sponsorship officer, and Rod Hochman, MD, president and CEO. The Providence Mission Leadership Institute launched in November 2021 as an accredited program in mission-centered leadership. It guides individuals through accelerated leadership development in three main areas: immersive learning, mindfulness in practice and activating one’s purpose.

After reviewing several global leadership approaches, it became clear to fulfill the mission, purpose and vision, created by the Providence legacy congregations, that this curriculum focus — supplemented with renowned speakers from across the U.S. — was the best option.