ISLAND

It’s time to find the perfect spot for your pride and joy. With 18 stunning locations, MDL has the best cruising grounds and expert teams to take care of your boat. Plus, with inclusive storage ashore and unlimited WiFi, you’ll find the right berth for you.

boat at Chatham.

Corlett-Pitt

EDITORIAL EDITOR

Sam Jefferson 020 3943 9261 sam.je erson@chelseamagazines.com

GROUP EDITOR Rob Peake

ART & PRODUCTION EDITOR Gareth Lloyd Jones WRITER AND SUB EDITOR Sue Pelling

PUBLISHING CONSULTANT Martin Nott

PUBLISHER Simon Temlett simon.temlett@chelseamagazines.com

ADVERTISING

ADVERTISEMENT MANAGER Mark Harrington 020 7349 3734 mark.harrington@chelseamagazines.com

SENIOR SALES EXECUTIVE

Charlene Homewood 020 7349 3779 charlene.homewood@chelseamagazines.com

GROUP SALES DIRECTOR

Catherine Chapman

HEAD OF SALES OPERATIONS

Jodie Green

ADVERTISEMENT PRODUCTION

Allpoints Media Ltd allpointsmedia.co.uk

CHAIRMAN Paul Dobson

CHIEF FINANCIAL OFFICER Vicki Gavin

MANAGING DIRECTOR James Dobson

Published by:

The Chelsea Magazine Company Ltd Jubilee House, 2 Jubilee Place, London, SW3 3TQ Tel: 020 7349 3700

© The Chelsea Magazine Company Ltd 2020. All Rights Reserved. ISSN 1367-5869 (print) ISSN 2059-9285 (digital)

THEY SAY THAT YOU know you're geting old when policemen start looking young. That might be true but to me a still more accurate gauge is when technology starts to completely ba e you. This has already happened to me sadly and I am regularly left scratching my head as I'm guided through the latest piece of navigation software by some enthusiastic marketing representative. My general tactic is to emit a series of enthusiastic yet noncommittal 'hmmm's', and do all I can to stifle any yawns. It is perhaps for this reason that my own boat remains stubbornly technology free, boasting nothing more than a depth sounder. In general this is su cient but I am well aware that others might find this Luddite approach both annoying and perhaps even a touch risky, given the amount of technological help there is out there to ensure we sail from A to B in comfort and safety.

Yes, whatever your feelings are on tech and yachts, there is one thing that I know I am right about. All of these navigational aids beep WAY too much. From the moment you switch on any of these bits of kit, they emit a reassuring beep to let you know they are working. Fair enough I suppose but from here on they develop a mind of their own. Many is the time that I have been lining up to moor a boat on test when two or three alarms decide to start beeping simultaneously. Often it's to tell you that the depth is low (because you are coming in to moor) or the bow thrusters are activated or have stopped working, or are thinking about restarting. Whatever the reason, it's precisely the sort of distraction you do not need as you are backing in to moor your boat. Similarly, I recently helped deliver a very smart brand-new yacht across the Med. Night watches were balmy and magical; the boat forging ahead across silvery waves gilded by the sea of stars overhead. In the magical silence you became entranced by the stars, the infinite beauty... then...BEEEP! You were regularly jolted from your reverie by some pointless alarm . I asked the skipper what it was for and he just shrugged and showed me how to mute it. I am therefore o cially launching a campaign to silence the beeps.

Online: Did

know

can

Oversee your

and digital subscriptions online today simply by signing up at https://www. subscription.co.uk/chelsea/Solo/. Stay up to date with the latest issues, update your personal details, and even renew your subscription with just a click of a button.

Post: Sailing Today, Subscriptions Department, Chelsea Magazines, Tower House, Sovereign Park, Lathkill Street Market Harborough LE16 9EF

The

Magazine Company Ltd makes every

Chelsea Magazine Company Ltd full set of terms and conditions please go to chelseamagazines.com/terms-and-conditions

JESS LLOYD MOSTYN is a writer and blue water cruiser who is currently moored in Singapore

twitter.com/ SailingTodayMag editor@ sailingtoday.co.uk

TOM CUNLIFFE is an author, journalist and TV presenter, and one of Britain's best-known cruising sailors

ANDY RICE is a journalist and veteran dinghy racer who has won championships at both ends of a ski

Dinan Marina is on the beautiful Canal d’Ille-et-Rance – the inland waterway that connects the Atlantic Ocean and English Channel. Located in town of Dinan, and home to a 14th-century castle, this is a real beauty spot to explore when transiting the Canal.

Photo: Gary le Feuvre/iStock

Photo: Gary le Feuvre/iStock

Dramatic styling combined with a dramatic turn of speed make for a photo that captures the power of a fast boat, hard driven. In this case it’s the ClubSwan 80 My Song being pushed hard on her sea trials. The boat is owned by Italian businessman Pier Luigi Loro Piana.

Photo: NautorCommunication

Photo: NautorCommunication

Voting is still open for our British Yachting Awards until midnight on Sunday 6 November – and Sailing Today with Y&Y readers can book limited tickets to the event via a link below.

We organise the awards annually with our parent company Chelsea Magazines to celebrate the best of the racing and cruising worlds.

It’s up to you to decide the winners – you can cast your votes after persusing the nominations, listed online at britishyachtingawards.com.

There are categories for the best new boats launched in the last 12 months, the best pieces of new sailing kit and clothing, the best marinas, as well as categories that recognise personal sailing achievements.

The winners are announced and trophies presented on 28 November, at an exclusive ceremony at the Royal Thames Yacht Club in Knightsbridge. Limited tickets for this event will be released for sale nearer the time – watch this News section and online. The winners are also revealed in our February issue, published on 30 December in the UK.

Among the nominees are 16-year-old Cal Currier who sailed solo across the Atlantic, the 22-year-old White triplet brothers who won

Marine insurance specialist Pantaenius is sponsoring the Sailor of the Year category in the British Yachting Awards.

Pantaenius supported the category last year, when octogenarian Murdoch McGregor won the vote after having sailed solo around Britain.

Simon Hedley, Pantaeniuis’ Head of Commercial Partnerships (pictured left), said: “The Pantaenius Group has been at the heart of sailing for over 50 years, and we are proud to sponsor theSailor of the Year award. The dedication and commitment of the nominees must be collectively celebrated and promoted to inspire others.”

Nominees in the 2022 Sailor of the Year category are: 83-year-old Kenichi Horie who sailed solo across the Pacific; 20-year-old Ellie Driver who completed the Round Britain & Ireland Race, with her father Jim; the crew of Ziggy, for their Cowes Week performances on a budget; the crew of Dark n Stormy, for their summer of racing success at Cowes Week, the Round the Island Race and elsewhere; Richard Palmer and Rupert Holmes on Jangada for winning the Sevenstar Round Britain & Ireland Race.

silverware at Cowes Week, and the school-age crew of Embley, who won the Round the Island Race’s ISC category, beating more than 500 entries – as well as the best boats, events, marinas and sailing kit of the last year.

Group editor Rob Peake said: “There are always some great stories among the British Yachting Awards nominations and 2022 has come up trumps with a series of heart-warming and impressive personal and crew achievements on the water. The industry, meanwhile, never ceases to innovate and evolve and our shortlist reflects that.

“We are proud to have seen the British Yachting Awards become a highlight of the marine industry calendar. It’s a moment when we can pause and take stock of the greatest achievements in the sailing world. The category shortlists are put together by our editorial team and expert panel of contributors.

“Now it’s up to you, our readers, to decide who wins.”

Vote at britishyachtingawards.com and book your ticket, including a champagne and canapés reception, for £90, via sailingtoday.co.uk

The Centennial Celebration of the Cruising Club of America was held at Newport, Rhode Island, in September.

The esteemed yacht club invited all its Blue Water Medal recipients to attend, including our correspondent Bob Shepton, who was given the medal for a circumnavigation he completed with a crew of young people some years ago.

Others included Jean-Luc Van Den Heede who has sailed six circumnavigations, and Randal Reeves and Steve Brown, who completed figure of eight voyages round the Americas via the NorthWest Passage and Cape Horn. Sir Robin Knox-Johnston gave an entertaining talk on his life at sea. There was also a talk called Heavy Hitters on Heavy Weather, by Sail Magazine, combining the wisdom of Randall Reeves, Rich Wilson, Jean-Luc, Steve Brown, and chaired by Frank Bohlen, Emeritus Professor of Marine Sciences, on ways of combatting heavy weather.

Bob Shepton presented a talk about the late Bill Tilman, also a Blue Water Medal recipient, called Tilman’s Legacy in the Modern Age. Bob said of his own exploits, sailing in high latitudes: “It was Tilman’s innovative vision to sail to remote regions and climb mountains from the boat. Maybe we were taking his vision to extremes.”

Co-organised by our columnist Andy Rice (see page 20), the 14th edition of the Seldén SailJuice Winter Series kicks o with the Fernhurst Books Draycote Dash on 19-20 November.

Seldén is back for the fourth year as title sponsor of the series, which since 2009 has aimed to provide “the fairest possible handicap racing for small boats in the UK”.

Founder Andy said: “Seldén has stayed with us through a very tough couple of seasons and we’re hoping that this will be the first season since the pandemic to be completed without any hitches or setbacks.”

As ever, the series aims to appeal to as many classes as possible, with typically almost 100 di erent types of boat represented across the season, from fleets as diverse as the traditional Norfolk Punt and National 18, to niche classes like the Hadron H2 singlehander.

Some fleets choose to use some of the events as their class championship, such as the RS Aero, which typically brings up to 50 boats for the concluding event of the season, the Oxford Blue. Contact Simon Lovesey if you’re interested in choosing one, some, or all the events in the series to form your own class championship, at simon.lovesey@sailracer.co.uk.

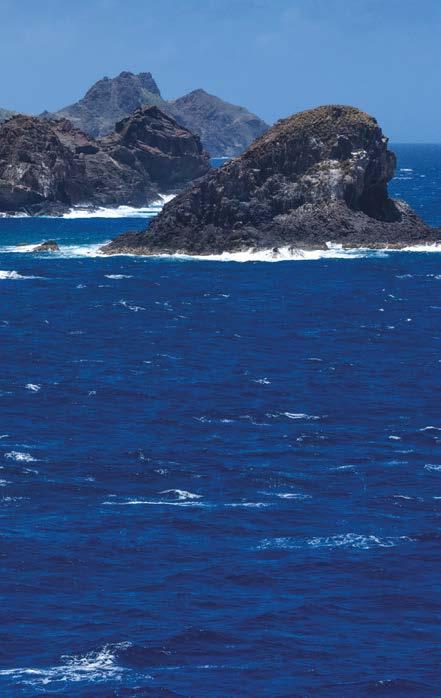

There have never been so many IMOCA entries in the famous two-week transatlantic race, now called La Route du Rhum-Destination Guadeloupe, which sets o from Saint-Malo on 6 November. With 37 boats set to take the start line, there are more podium contenders than in any previous edition. The British sailors include Pip Hare on Medallia, Sam Davies on a new Initiatives Coeur 4, and the young James Harayda on Gentoo (pictured).

The 2018 edition saw a dramatic finish with Paul Meilhat taking the IMOCA title. He returns with a new boat in the colours of his new sponsors Biotherm. His is just one of seven new IMOCAs which have been launched over the last four months. There are four pairs of sisterships now, creating some fascinating races within the race. Vendée Globe winner Yannick Bestaven’s new Maitre Coq V is a Verdierdesigned sistership of 11th Hour Racing-Mâlama, while Sam Davies’ new Initiatives Coeur 4 is sistership to the Sam Manuard-designed L’Occitane en Provence Three boats come from completely new moulds. There is the Verdier Holcim – PRB by Kevin Esco er, Manuard’s Charal2 by Jérémie Beyou and the VPLP designed new Malizia – Sea Explorer of Boris Herrmann.

Kévin Esco er (Holcim - PRB) believes that the “new boats will not be favourites, it is will be the boats of the 2020 generation that are more reliable that will have the advantage”. The dominant Charlie Dalin (APIVIA) and Thomas Ruyant (LinkedOut) both have new IMOCAs in build and this will be their last race with their current monohulls. Dalin, second in the Vendée Globe, is the recent winner of the Guyader Bermudes 1000 Race and June’s Vendée Arctic race and remains undefeated this season. But he has never competed in the Route du RhumDestination Guadeloupe, while Thomas Ruyant, who won the Transat Jacques Vabre last year is also a contender for the win.

There are also 13 rookies, including Swiss sailors Justine Mettraux (Teamwork. net) and Oliver Heer (Oliver Heer Ocean Racing), the Chinese Jingkun Xu (China Dream-Haikou), and James Harayda.

Juliet Costanzo of Australia and the crew of Easy Tiger Racing take a cooling leap overboard as they prepare for the Corfu round of the Women’s

Match-Racing Tour – the 2022 EUROSAF Women’s European Championship. Twelve of the world’s top women’s match racing teams were in Corfu for the event in October. The Tour claims to be the “world’s first and only professional sailing series for women”. Also competing was British skipper Sophie Otter with her Otter Racing Team of Scarlett Anderson, Amy Sparks, Hatty Ward and Hebe Hemming. womenswmrt.com

Wendy Schmidt and the crew of Deep Blue won the 54th edition of the Barcolana presented by Generali, which was held in Trieste in sunny conditions and 25kt gusts, with a fleet of 1,614 boats taking part. It means the Barcolana Cup is heading to the New York Yacht Club for the first time. Deep Blue crossed the finish line in just under an hour, after completing the course in the bay of Trieste. Wendy Schmidt, who is also behind the 11th Hour Racing Team, said: “Thank you, Trieste. Everyone has been absolutely wonderful here and it was a pleasure to sail and enjoy this beautiful natural landscape. Now I get why everyone loves taking part in this regatta in this city.”

Speaking of an award she received for female leadership, she said: “There are so many great, passionate, smart, talented female sailors. Sailing is a wonderful sport that knows no gender, age, or barriers. I always encourage people to sail because we are all linked to the ocean: whether we know it or not, we are all part of its future.”

The major international marine trade show known as METS opens its doors in November after last year partially blighted by the pandemic. The trade event takes place in Amsterdam with the celebrated DAME award as its centrepiece.

Niels Klarenbeek, Director METSTRADE, says: “The industry is eager to be back at the world’s largest B2B leisure marine industry event after an extraordinary 2021 edition. We have created a balanced layout with key points of interest in every hall in close co-operation with our partners such as ICOMIA and the Exhibition Committee. This allows us to accommodate METSTRADE’s growth with more exhibitors, more space, more focus and an enhanced visitor experience. We cannot wait to see everyone return to Amsterdam in November.”

Udo Kleinitz of industry body ICOMIA said: “Following the pandemic’s challenges, key industry stakeholders and associations are telling us it is more pivotal than ever for suppliers and buyers to connect with their industry peers. METSTRADE is the leading platform for leisure marine professionals wanting to stay relevant and up-to-date in the industry. With the entire sector present from across the full supply chain, it is the best place to source, connect and learn to help your business grow.”

Multihulls have become incredible living and cruising platforms, o ering more space than many first homes! Have we reached a zenith in design and build?

At any single point, it is hard to imagine what can be improved and what we can expect next, but the designers always amaze us with what can be achieved. For example, introducing a full-height door through to the forward cockpit has single-handedly transformed what can be achieved in terms of living space. As technology and material improvements continue to advance, we can expect even more ways to enhance life on board.

Multihulls are billed as the ultimate bluewater cruisers. What sort of trips are your customers doing? Despite being designed and built to go anywhere, we have several customers who simply want the finest catamaran that is available on the market, even if their sailing plans don’t require such remarkable build quality. Those who do choose to set their sights on the horizon are often drawn toward the Pacific Islands.

Is there an average multihull buyer in 2022 and how do they use the boat?

Our most recent deliveries have been to newly retired people, who plan to explore the globe with family and friends joining them en route. This group tend to make up the majority of our owners but there is also an increase in younger couples and families looking to achieve similar things, often inspired by YouTube vloggers or the desire to live ‘o -grid’.

How has Privilège maintained its position in such a competitive market? Privilège to catamarans is very much what Oyster is to monohulls and a much-envied position. The brand ethos is to continue to build the strongest,

safest, most reliable and highest quality catamarans available, which is a remarkably unrivalled section of the market, as the volume builders strive to supply the charter market.

To what extent can an owner customise their new Privilège?

A significant amount is the short answer. Recent projects have included a jacuzzi, dedicated bike storage and a dive equipment room.

The Signature 580 gives direct access to the owner’s cabin from the forward cockpit. Any other superyacht touches?

This has been one of the biggest recent design advances in the range and really well received by the market. Privilège interiors are designed by Franck Darnet, who has built his reputation with superyachts and you can see a lot of influences from his larger yacht projects.

Is the perception still true that the multihull market continues to do better outside the UK?

Yes – there are plenty of UK-based buyers, but they generally intend to keep them in the Med or Caribbean. Most of this is driven by how they intend to use the boat, spending longer periods onboard but this is also amplified by the lack of appropriate marina berths in the UK. Even if UK marinas could re-configure their spaces to accommodate multihulls better, the drive is still to take them to sunnier climes.

There will always be peaks and troughs, but sailing appears to be less a ected than power, as a sail boat tends to be a more considered purchase, often tied in with a life event such as retirement. We find that it takes a lot to derail peoples’ long-term plans and dreams and in some cases, global upheaval often drives people to achieve their dreams sooner.

inspirationmarine.co.uk

More than 83,000 people visited the 53rd Southampton International Boat Show in September, with more than 14,000 people getting afloat on the show’s Try-a-Boat stand and other initiatives that allowed visitors to try paddleboarding, sailing and motorboating.

Lesley Robinson, CEO, British Marine, said: “Visitors have also been able to get out on the water onboard a selection of fascinating and historic craft including the Morgenster tall ship, F8 landing craft, motor gun boat 81, and the high-speed launch 102. I would like to o er my thanks to Rockley Watersports, Flexisail and Portsmouth Historic Dockyard for making the on the water experiences such a huge success.”

The show boasted more exhibitors, debuts and boats than ever before – a total of 685 stands and berths across the event’s 70,000sq m footprint. Over 650 craft were on display, with 300 in the marina.There were 126 new companies this year and the show hosted 167 UK and world debuts.

Lesley said: “There has been a fabulous atmosphere at this year’s show and the feedback we’ve received from exhibitors from across the industry has been exceptional, with many indicating very strong sales. The show has put a real smile on everyone’s face with a fantastic mix of products, talks, entertainment and refreshments, plus our stunning new VIP experience. We’ve welcomed everyone from boating newbies to seasoned sailors and watersports enthusiasts, and the wide choice of sailing yachts, motorboats, accessories, paddle boards, kayaks and services has been incredibly well-received.”

British Marine said the three days of national mourning and the closure of the show for one day as a mark of respect for Queen Elizabeth II had impacted visitor numbers but declared the resultant nine-day event a huge success.

A new addition to the 2022 show was a Quayside Club VIP experience, which proved popular.

This new foiling boat, FlyingNikka, in the style of an AC75 used in the America’s Cup, stole the headlines at Les Voiles de SaintTropez in October. Designed by a team led by Irish designer Mark Mills, the 19m posted speeds in excess of 40kts. She was built in Valencia at the King Marine yard. Team manager Alezio Razeto said: “The owner, Roberto Lacorte, was keen to have a thoroughbred race boat, built for speed. We’d witnessed the development of foils on the IMOCA class sailboats and the America’s Cup yachts, so we said to ourselves: why don’t we have articulated foils on a race boat in the Mediterranean? It’s Roberto Lacorte, the owner, who helms the boat. The crew largely has an America’s Cup background. Helming a foiler isn’t the most di cult aspect. The real di culty lies in trimming the sails and the foils. There are a huge number of elements which need configuring to get her up on a plane, airborne and nicely balanced, especially given that the pressure in the sails is never constant. Adjusting the foils is the most complicated element, particularly when you’re flying along at over 30 kts!”

The event attracted around 250 modern and classic yachts, including 46 Maxis, with 2,800 sailors. This year was the 160th anniversary of the organiser, the Société Nautique de Saint-Tropez.

a new meaning to sailing high or low

A new sport called Sail Surfing is taking o in the dinghy classes, swapping surfboards or windsurfers for something with a sail and tiller. The sport can trace ancient origins in the Pacific islands, where the fisherman’s ability to surf his sail-powered multihull into the beach, carrying a boatload of fresh fish, was a skill on which the welfare of the entire island depended. Fast forward several centuries and it took root again among surfers in California. Tired after long days standing on their boards, they would use the last few waves of the day surfing more comfortably in Lasers, Aeros or even the Flying Dutchman, whose 20ft loa became known for its wavecatching ability. While the sport began in beach wave conditions, regattas have now spread across the world with competitors utilising big wind-over-tide conditions to similar e ect. As well as the round-the-buoys race, marks are given for how high above your opponent’s head you can get your boat. Judges on the racecourse measure this using altimeters. It gives an entirely new meaning to the terms sailing high and low.

Marks are given for how high above your opponent’s head you can get your boat...

PORT SOLENT

PORT SOLENT

The ClubSwan 41 is the latest in the new generation of one-design racers launched by the Finnish manufacturer. The boat sits between the ClubSwan 36 and 50 in its range, and promises a similar blend of amped up performance combined with dramatic looks and potential for extremely fast cruising.

Like the other boats in the range, the 41 is designed by Juan Kouyoumdjian and will compete in ORC Category B.

As you’d expect, the boat is very light at 6,200kg and also features a massive sail area with the mast stepped almost centrally allowing for a very large fore triangle. This is a serious racing machine but the interior remains important and Swan has worked with New Zealand studio Pure Design & Engineering and Lucio Micheletti to create a modern, comfortable space.

l nautorswan.comFrench manufacturer Fountaine Pajot has built a solid reputation as a multihull manufacturer by producing affordable cruising catamarans in the 40-60ft’ size bracket. The unveiling of a new 80 footer is therefore something of a step change for the company as it catapults the marque into a somewhat different market. Nevertheless, the new 80 embodies many of the features seen in the smaller boats in its range, including high levels of comfort and class-leading accommodation space. At the same time, it’s all just a bit bigger and more luxurious. The price? A cool 4.9m Euro.

l catamarans-fountaine-pajot.com

Hanse began a revamp of its range last year with the launch of the Hanse 460, and has followed on with its new 510. Like the 460, it breaks with Hanse’s heretofore go-to designer Judel/Vrolijk and switches to the Berret/Racoupeau team who have worked extensively with French manufacturers Beneteau and Jeanneau in the past. The new boat is strikingly modern in its looks and features a high volume hull with plentiful beam carried right aft, and has twin rudders.

Hanse is aiming to up the quality of the product somewhat with its latest generation, and this means a somewhat more plush interior. As you’d expect there is also masses of accommodation space, making this an ideal fast cruiser.

l Inspirationmarine.co.ukA look at the latest launches from around the globe

The Beneteau First 44 picks up squarely where the manufacturer left off with the First 53. This is to say that the boat is most definitely a cruiser/racer which delivers decent amounts of comfort and speed. The boat is competitively priced (starting price is 335,000 Euros) and the design team of Roberto Biscontini, who penned the hull lines, and Lorenzo Argento, who did the deck and interior, have produced a stylish, fast yacht that remains easy to handle. Displacement is moderate and the aim has been to create a yacht that is well adapted to the light winds of the Med but also has the power to stand up to strong winds. To gain this much coveted blend, the designers have produced a boat fine on the waterlines but with plenty of flare aft reducing wetted surface area, despite the fact this is a twin rudder yacht. This is a yacht that takes aim at Dehler, Solaris and X- Yachts and offers an exciting alternative.

beneteau.com

Croatian boatbuilder Salona has been slowly but steadily revamping its range, and the announcement of this new 39ft cruiser/racer further augments its range. The lines are penned by Italian design house Cossutti who has drawn up a fairly conservative design with modest beam and plenty of taper aft married to a single spade rudder and a lead bulbed T-Shaped keel. Displacement is a relatively modest 6,200kg. Accommodation is generous, with a large double aft cabin, and stateroom forward in standard format. The price is also attractive, making this an interesting alternative to, say, X-Yachts or Arcona.

l salonayachts.com

Of all the sounds I’ve ever heard on a boat, the most terrifying is the shuddering ‘crump’ of a heavy wave cascading onto the cabin roof. I’ve only heard it once but it is truly nerve- shattering. I’m not talking about the harmless slap of what might be called an ‘ordinary’ wave against the topsides; I’m talking about that moment when your poor boat suddenly feels the true weight of the sea. It shakes you to the core. I’ve only felt it once, but it was memorable.

I was hove-to in something a bit short of a gale, west of the Azores. e seas were far removed from that chilling description, ‘high’, but it was certainly bouncy and I spent most of the day in my bunk except when I got my hourly muscular workout trying to make tea. e ‘crump’ came in the middle of the night. One wave, bigger than the rest, must have appeared out of nowhere - I didn’t see it coming. e boat, having ridden over the others with little di culty, was brought to a shuddering halt by this concretelike wall of water. e bang was as stunning as a canon shot, and to be in the cabin at that moment was to be like a nut in a shell, crackers about to attack you. I feared the worst. But nothing happened. e boat was ne, the mast still standing, the portholes sound, although my heart was ogging like a storm jib in a tack. e next morning I discovered the Avon dinghy had gone over the side and may have been well on its way to America by then, but that’s a story for another time.

I am telling you this because in the safety of my own home, a similar thump resounded around the house the other morning. It was the landing on my doormat of the latest edition of that classic book, ‘Heavy Weather Sailing’.

As a 22 year old with my rst little 17 footer, and with no knowledge of how to sail, why was this the rst and scariest ever volume I purchased? I suppose because the ultimate storm is everyone’s greatest dread, and while it is easy to gather routine experience over the years, there’s not much that can prepare you for a life-threatening blow. So I read what it was like for other people, hoping to learn

When it comes to the environment, where is the balance to be found? facebook.com/ sailingtoday @sailingtodaymag sailingtoday.co.uk

something from them, and taking mental notes, in between prayers. at early edition of mine, which to my great regret I no longer have, was the work of K Adlard Coles who did immense service in communicating, as well as practising supremely well, the art of cruising under sail in the 50s and 60s. e publishing company which still carries his name maintains his tradition of being steadfastly enthusiastic about everything to do with the sea from a cruising boat point of view. I imagine that the boats I read about nearly y years ago would have been far removed from those of today. Ga rig was still hanging on, and I dare say there were still a few with canvas sails. GRP was in its ascendency, but still not fully trusted. I once owned a GRP boat built around this time and the hull was as thick as a bank vault because the builder didn’t fully trust that plastic stu . e latest edition is skilfully edited by Martin omas and Peter Bruce who have brought their own wealth of experience to the task, but I wonder what Adlard - who was probably used to cruising with hemp rope smelling strongly of stockholm tar -would have made of the chapter on icy, high latitude sailing, now a commonplace activity, or handling a RIB in heavy weather. ‘A RIB?’ he might ask, ‘and what would that be?’ ere’s even a chapter on sailing with ‘foils’ which, to my eye,and probably his, are inconvenient sticky-out things which make you go faster but prevent you ever putting out fenders. Adlard, and I, would probably take a hacksaw to them.

e book makes for an instructive read but do we, as everyday sailors, need to focus so much on heavy weather? Need it spoil a good night’s sleep? When we learn to drive we don’t fret about coping with a car crashes, so why fret about the worst that sailing can throw at you.

Seriously heavy weather is quite rare. A wide-ranging American cruising sailor, Beth Leonard ,sailed all the oceans of the world with her husband, keeping careful log of the conditions she encountered. She reported that for something over 75% of the time, there was too little wind rather than too much. So enjoy ‘Heavy Weather Sailing’ but don’t let it give you nightmares.

Paul reflects back on one of the most spine chilling reads of our times. No, the author is not Stephen King, it’s K Adlard Coles, whose Heavy Weather Sailing is a bona fide classic

‘The boat, having ridden over the other waves with little di culty, was brought to a shuddering halt by this concrete-like wall of water’

I’m half way through an eight-week tour of Europe which has been a good reminder of the full breadth and diversity of our sport. From commentating at the Bosphorus Cup in Istanbul and the Barcolana in Trieste, to the hardcore competition of the 470 Europeans in Turkey and Formula Kite Worlds and Europeans in Sardinia and Greece respectively.

e Bosphorus Cup and the Barcolana are both big boat races but more than races they’re a parade of sail, a festival of fun which also happen to help promote the cities in which they take place. Sailing through the Bosphorus is a real treat, one that event founder Orhan Gorban created more than 20 years ago when he convinced the authorities to close the narrow passage between the Black Sea and the Mediterranean to commercial shipping for a six-hour window. If you’ve never heard of the Bosphorus Cup before, Google it and then nd out how to charter a boat next year! e same for the Barcolana. Even though entries were down this year (at a mere 1619 boats on the start line), it is a breathtaking tra c jam of sailing yachts. Most people are there for the sheer experience of being part of the biggest sailboat race in the world, others are there very much for the win. So much so that one Maxi skipper threw a glass of beer over a rival who had protested him and now nds himself at the mercy of a Rule 69 hearing for Gross Misconduct. I spoke to a rules expert about this and he said the best thing to do - if you choose to douse your rival with beer - is to laugh while doing it. Don’t scowl and look like you mean it, otherwise Rule 69 will come calling. Intent is everything.

Talking of protests, there are strong signs that the young and fun riders on the Formula Kite circuit are having to grow up quicker than they might have liked. Turning from a beach event where riders are there for the pure fun of it, but now to a high-intensity campaign where achieving a particular result determines whether or not you’ll receive funding for the coming season - the priorities are beginning to shi .

On the nal day of the European Championship on a windy day in Nafpaktos, Greece, and there was a touching of control lines between two riders in one of the seminal heats. Generally the riders have all signed up to a ‘gentleman’s agreement’ where they shrug o marginal contact between lines or kites as part of the game. is time, however, Gisela Pulido from Spain decided to protest her rival from France, Poema Newland.

With their 15 square metre kites hovering above them on

the beach, the two riders stood with their backs to each other as the three-person jury reached their shoreside verdict. Newland was in oods of tears as she was told of her disquali cation while Pulido bounced back into the waves, ready to contest the four-rider nal, from which she would take the bronze medal.

Pulido copped a lot of heat on social media, the weight of opinion seemingly against the Spaniard. But that protest is an inevitable part of growing pains as the sport loses its naivety and innocence to modernday Olympic campaigning and all the pressures that go with it.

Pulido’s point of view is pretty straightforward: “When we go out and race each other, we are racing with the knife in the teeth, it’s full-on war. When we come ashore we are friends again.” Newland and others will take some persuading to come around to this point of view but, like it or not, Pulido’s point of view will win out in the end. When you make a pact with the devil, ie becoming an Olympic class, sometimes the fun and the friendship is pushed down the priorities.

Where Pulido will struggle to win her side of the battle is the growing size of kitefoilers. Even in light winds, in fact especially in light winds, the heavier riders are able to hold down bigger kites and generate higher levels of apparent wind. With top-end upwind speeds of 23 knots, even in just 8 knots of true wind, and downwind speeds sometimes in excess of 40 knots, heavy bodyweights are easily justi ed. e fastest female riders are operating between 68kg and 80kg, while Pulido has to do long hours in the gym to get herself over 60kg.

Daniela Moroz, who has just won her sixth world title, has increased her weight to close to 70kg, although she’s not particularly happy doing so. e American rider is keen to see maximum kite sizes limited to take the pressure o the women having to get fat to be fast.

Toni Vodisek, the 95kg Slovenian who has just won his rst men’s world title, walks around proudly with his dad bod, even though he’s in his early twenties.

As a sailing journalist and TV commentator Andy has unparalleled knowledge of the performance racing scene, from grassroots to elite level

e same challenge faces the windsur ng athletes who used to try to be as skinny as possible for the now extinct RS:X board. Now they are trying to bulk to be as heavy as possible for the foiling replacement, the iQFOiL. It’s a tricky subject and one that will need resolving if athletes are to be encouraged to look like athletes.

“More than races they’re, a festival of fun which also help promote the cities in which they take place”

eaving on any passage leaves me with a dry taste in the mouth, a pile of butter ies in the stomach and a lot of ticking o of checklists. e boat is stu ed from stem to stern with enough food for four ocean passages. We have enough spares to x just about anything on board, though Sod’s Law dictates that the one spare we do need will be the one we omitted. It’s kind of endearing that, however many times we get ready for a passage, it is still a daunting experience setting o into the open sea on a small boat. e nerves get to you every time and the bravado

on the dock is notably muted. e one item on a check-list that all of us keep looking at is the weather and, importantly, whether there is bad weather in the o ng. Even in these days of grib forecasts, using half a dozen di erent models, the weather gods can wreak havoc.

I’m pretty thorough in my research of historical weather records for an area or a passage, and we also monitor several weather websites to get a sense of what is happening. And yet it can all turn to custard, and we need to be prepared for heavy weather.

Probably my go-to tactic for heavy weather was gleaned from Moitessier’s e Long Way when he described how running before

a storm that he stopped trailing warps and let Joshua go at its own pace over the waves. Even in a heavy old boat like Joshua he could run under bare poles and safely surf over the waves keeping a sort of rhythm with the sea.

In early December 2003 we le Las Palmas Marina on Gran Canaria heading for Guadeloupe in the Caribbean. Seven Tenths was a 36 (11m) Pedrick Cheoy Lee with three of us on board. We were ve days out when the weather began to deteriorate, and we reduced sail to run with 45-50kts of wind.

Rod Heikell provides some pointers on heavy weather sailing techniques drawn from his extensive experiences

Our weather was once a day from checking in on the SSB net when an American boat ahead of us that had satellite coms would relay the forecast. As we surfed down the waves Lu got the forecast and would draw up a sort of synoptic chart and come out to tell me the bad news: “ is is tropical storm Peter and this is us”, she said showing me the chart. We were e ectively tracking the storm at about the same speed and we were squarely inside the southeast quadrant.

As Seven Tenths surfed down the watery slopes of this out of season tropical storm in the Atlantic, I remember looking up in awe at the storm cells leaking lightning and

A mainsail with a deep third reef has always served me better than a trysail

While a storm jib is a more viable option than a trysail, a staysail or even a roller furling headsail have worked for me

In Antigua before setting o across the Atlantic, I suggested to the crew that they rig the storm jib and trysail that had come with the boat, while I was o doing some paperwork. When I returned three hours later, they were still struggling to get the storm jib and trysail on – and that’s in the marina.

For the last 30 years I have ordered any new slab reefing main with a deep third reef about equivalent to the size of a trysail. Ask your sailmaker to reinforce this third reef with extra cloth and added stitching. If you have a roller reefing main get the sail reinforced for the area that will be out when reefed right down. We keep this third reef rigged with reefing lines all the time, as it can be useful even in calmer weather when heaving-to, or slowing the boat down at night for a daylight entrance to a harbour or anchorage.

Whenever the weather has deteriorated to the point where a trysail and storm jib are needed, I use the main reefed down to the third reef, and either the roller reefing genny with just a bit out, or a staysail partly reefed. Modern sail material is marvellous stu compared to 20 years ago and, in most cases, the critical issues have not been the material itself, assuming it is in good condition, but stitching, fixtures and fittings. Blocks, the

attachment points for reefing lines, the furling line for the headsail, cringles and reinforcement points will often break before the sail material does.

The furling line for roller reefing headsails is often a weak point when hitherto unnoticed chafe lets the whole shebang out in 50kts of wind and ,trust me, getting that lot down and tamed is intimidating.

I’m sure someone will pop up here and tell me that this is an irresponsible and unseamanlike attitude but rigging a storm jib and trysail in bad weather at sea is to my mind unseamanlike. Getting the storm jib hanked on and up on a heaving foredeck doesn’t captivate me either, but should the need arise it’s a lot easier to get the storm jib on than to get the trysail rigged.

That said headsail roller reefing systems are a lot more robust than most people think and I’ve yet to rig a storm jib in gale force winds. Let’s face it: in 50 kts of wind it’s damned di cult to hold onto flapping Terylene let alone get it hanked on and flying. In both Seven Tenths and Tetra I’ve hove-to in 5060 kts sustained with a deep-reefed main and a patch of roller reefing jib, and while I may just have been lucky to avoid damage to the sails, we all need a bit of luck out there.

dangerous amounts of wind all over the night sky. It was scary stu and it’s di cult to describe the menace of 50kts plus of wind, and clouds full of lightning trails. Seven Tenths was behaving well with the waves but we needed to heave-to to let the storm pass. I put the main up with its deep third reef and let a little bit of genny out on the roller ree ng, and backed the genny and magically we were hove-to. We had practiced this before but in much less wind and I was surprised at how calm things were. We still had waves breaking over the boat, but from the bows and she sat at 15 degrees or so o the wind, slowly clocking up and back o the wind. I went to my bunk a er being up for 36 hours or so and Lu and Ian kept watch.

I could be forgiven for thinking that someone up there has got it in for me. Tropical Storm Peter battered the crew of Seven Tenths as it passed close northwest of us with the wind recorded at a constant 60kts and with a de nite hurricane eye. NOAA were just about to classify it as a hurricane before it hit a cold front and petered out. e thing is that this was the rst time since 1887 that a tropical storm had been recorded

in the Atlantic in December. And the irony of it all was that Lu and I were going to the Caribbean to get married. My future fatherin-law was called Peter.

e lessons are plain: Bad weather can brew up at odd times of the year, especially with climate change a ecting things. Running o is an ok tactic but not with tropical storms and hurricanes where you need to get out of the way of the system and head for the equator. And that deep third reef proved its worth yet again.

In mid-Paci c on our way to Palmerston Island, I noticed the wind speed was creeping up over 30kts. Lu had just gone o -watch and was not best amused at being called up, until she looked out the back at the evil greeny-grey cloud stretching right across the horizon. Time to reef the main I said while reducing the roller-ree ng genny. By the time Lu was up at the main, the wind speed was up over 40kts

and, as she wrestled the main down the wind speed kept going up.

Time to get rid of it all together. Once Lu had tamed the main the wind was over 50kts and climbing. I rolled up the genny completely and we scooted along under bare poles at 7-8kts with the wind at 60kts plus. We donned life jackets and harnesses – I know, but better late than never – and steered Skylax directly downwind. A er a couple of hours, the wind was down to 50kts and then 40kts. Strange

how 40kts and dropping is a relief a er so much wind. I remember reading in Moitessier’s e Long Way that the art now is to keep letting out a bit of sail, usually the roller ree ng genoa, to keep the boat going fast enough so it is not pooped by the sea that has built up.

We still got a couple of wavefulls into the cockpit, where the biggest annoyance was the cockpit cushions floating around our shins. And I was worried about the engine start panel in the cockpit,

which had been underwater a few times from the waves washing in. As it turned out it was ok except it lost its buzzer when you turned the ignition on.

We got off lightly. The middle sprayhood was knocked flat. The MOB aid on the transom was washed away. But apart from everything in the cockpit getting drenched, we were ok. After four hours we were back to full genny and a double reefed main, on our way to Palmerston Island.

BELOW LEFT Skylax in brisk trade wind conditions – two reefs in the main and a partially furled genoa BELOW RIGHT Hustling along in the Paci cSometimes it is not the sheer force of the wind that makes a voyage hard going but the overall situation visà-vis wind, the season and current. We were at the bottom of the Red Sea getting out of Bab El Mandeb, the Gate of Tears, at the wrong time of year with a war going on aswell. Bab El Mandeb is the southern entrance to the Red Sea with the small channel on the east side and the main channel, including the shipping channel with separation zones, between the Yemeni island of Mayyun with a coastguard station on it and the Djibouti coast on the other side. Currents mostly ow northwards here, but there are tidal streams as well that will increase or decrease the current.

‘ is is the BBC World Service. ere are reports that Eritrea has invaded the Hanish Islands near the bottom of the Red Sea and occupied Greater Hanish Island. A number of Yemeni soldiers manning the garrison have been killed and the commander of the Eritrean force reports that 80 soldiers have been taken prisoner. e Yemeni

government is sending forces to repel the invading force including a number of naval cra and Mig ghters.’ None of us said anything but just looked at each other as we tacked towards the Yemen coast under Greater Hanish. We had spent ve days in the anchorage at the top of the island wistfully hoping the strong southerlies of 30-35kts would die down a little. Partly because we were getting frustrated at just sitting there and partly because Colin had to y back to London, we had decided to buckle down and beat to windward whatever the wind gods were doing in this part of the world. Now it seemed there was going to be a bit of a war as well.

I had le Turkey in September and sailed Tetra down to Cyprus where Colin and Frank were to join me. Tetra is an old fashioned, long keel yacht built by Cheverton on the Isle of Wight in 1962 and, at just 31 , a rather small yacht for this sort of voyage against the prevailing wind and current. Once through the Suez Canal we pottered around the coast a bit before picking up a good northerly blow, reaching Massawa in Eretria in something under ve

days. Even loaded down, the old lady had averaged 130 plus mile days.

In Aden a er nally escaping through the Gate of Tears

e problem was that I knew that the wind and current would likely be against us from then on, but only in theory. e bruising reality of beating to windward in 30kts and against the current meant that a day’s run was lucky to be 50 miles and it was di cult to sleep, eat or do anything except wedge yourself in the cockpit and turn your head away as green water cascaded over the deck and into the cockpit. ere were times I wished for 150 of ocean-going motor yacht instead of 31 of old-fashioned sailing yacht. Our worst patch was 12 miles made good in 10 hours, but eventually we made the small strait on the east side of Bab el Mandeb and, as we passed through the Gate of Tears, we had our own personal version of why it was called thus and it had nothing to do with sorrow at leaving the bottom of the Red Sea.

In the bumpy bits at the bottom of the Red Sea I had rashly promised all sorts of things to Colin and Frank to keep our spirits up. Amongst these promises was a slap-up meal with all the beer they could drink. e thing

A shing dhow in the Hanish Islands tied up alongside Tetra

We always make a libation to the wind and sea gods wherever we go

is, nobody had mentioned that in the last war in 1994, the north had won and being more fundamentally minded than the south, alcohol was banned. Except for a few of the large hotels where beer was $5 for a small can. It was an expensive promise but a er the bruising experience of getting out of e Gate of Tears I was more than happy to pay up and more than happy I had ordered new sails for Tetra including a main with a deep third reef in it.

None of us wants it and, in practice, you are unlikely to experience bad weather when sailing in the right season for a stretch of ocean. Most damage comes from squalls where the wind speed may peak at 40-50kts for a short time, o en accompanied by the wind veering dramatically. As long as you keep an eye out astern for squalls, and reef down before one arrives, then you will likely avoid damage. It is the gung-ho sailor who keeps all white sails up in a squall who will come to grief. Normally this will just be sail damage, though it is also possible to damage the rig. at said, there can be occasions when sustained bad weather does happen at sea and skipper and crew need to have a bit of an idea on what to do. I say a bit of an idea because we all have scenarios we have read, on dealing with heavy weather, but in practice things can be a little more uid and involve more guesswork than following a recipe of what to do in gale force winds.

From my experience, the following has worked ok up until now.

As long as you have sea room, run o before the gale. Reduce all sail except for a bit of jib or put up the storm jib and run with the wind. You will likely have to hand steer so make sure you are clipped on. Even under bare poles I’ve done 7-8kts in winds up to 50-55kts with a reasonable amount of control. What is important, is to start increasing sail area as the wind begins to drop and the by now big waves start to collapse on the top. You need to keep speed up to avoid being badly pooped by these collapsing waves.

ere are those who are fans of a sea anchor let go from either

A retro tted electric winch can make life a lot easier in heavy weather

the stern or the bows. I’ve had no experience of these and gured if I was running o downwind I could always trail warps and the kedge anchor we keep on the pushpit.

If running o is not an option, or is the wrong option for other reasons then I usually heave-to. With a deep third reef in the main and a scrap of backed jib, you can tie the helm o so the boat fore-reaches into the wind and importantly into the seas. Depending on the boat, you can be anything from 20-60 degrees o the wind. My previous boat Seven Tenths, a Cheoy Lee Pedrick 36 was ‘better’ at heaving-to than my present boat Skylax, a Warwick Cardinal 46. Being hove-to is remarkably calm and you are meeting the seas with the sharp end of the boat, which just seems a better way to do it.

Lying ahull has never worked for me. e boat tends to lie across the seas and the waves smash into the hull with some force, forcing the boat over every time a wave hits. In really big seas it seems to me there is the danger of a B2 knockdown and I have only ever tried lying ahull in 35-40kts a couple of times. It is not my preferred option.

Books have been written about dealing with heavy weather so this is no more than an outline, but I will stress again that you are unlikely to encounter a full gale at sea if you are in the right stretch of water in the right season. You will always encounter gale force winds for a short duration when squalls come through.

Back in the days when boats still leaked and electronics weren’t even a glimmer in the sunrise, I learned many a useful lesson from the foreman at the Elephant Boatyard up the Hamble River. e late, great Davey Elliot was a classic Solent longshoreman of the old school. I really don’t think there was anything about boats he didn’t know, but his talents reached far wider. He was an

accomplished student of the human condition, he had a tongue that would split solid oak to take down any upstart sailor who fancied himself, and he was a natural healer.

is latter gi was kept private and I had no inkling of it until one day, su ering more than usual from a cartilage injury, I was limping back to my boat from a trip to the skip when he called over to me.

“Looks like you’ve got a problem with your knee, Nipper,” he said.

Catch up with Tom’s columns now and in the future at sailingtoday.co.uk

Although I was then pushing 50, he’d called me that ever since I was a 6 6in 22-year-old struggling with my rst wooden boat.

“Come on over to my emporium and I’ll see what I can do.”

Not knowing what to expect, I tottered across to the shipping container where he kept his tools and work bench. Few of us on the yard were ever invited into this sanctus sanctorum, so I must have been doing something right. What

CUNLIFFEwhen

comes to close quarters handling in a marina

I recall best is the wonderful scent of the place. Fresh wood shavings mixed with Stockholm tar blended with linseed oil made a heady whi , while dri ing over it all was the pale blue fug of Davey’s pipe, which was rarely seen out of his mouth. At the end farthest from the door stood his well-worn sea chest, dating from his time as a ship’s carpenter going deep-sea. He sat me down on this and sized me up. We’d known each other for a quarter of a century. Although I was never a natural with caulking irons, saw and chisel, I like to think he had developed a sort of respect for me as an honest tryer who did at least make a habit of disappearing over the horizon and returning with a few tales to tell.

Davey didn’t say anything. He just held his cupped hands around my knee and seemed to go o into some sort of trance. He wasn’t touching me at all, but a er half a minute or so, my knee began to heat up. is was no illusion. It was pulsing with warmth and, a er a little while, he pulled his hands back as though they were being burned.

“ at’s enough for now,” he said, shaking his wrists. “It’s too hot for me. Must be doing some good. Come back tomorrow at ve o’clock when I knock o . We’ll give it some more.” And with that, he shooed me out, locked up the container and strolled back to the gangway of the traditional shing boat where he lived.

My knee felt better in the morning, and at 1700 I came back into the yard to report for treatment. Davey didn’t show up, so I waited until six o’clock then went to the pub next door for a refresher. In the bar I fell in with a neighbour from the yard. He looked sick and I was about to tell him that Davey hadn’t appeared, which was out of character, when he broke the news that my old friend had literally dropped dead that a ernoon.

Several pints later, more of Davey’s acolytes had gathered at the bar. Still in a state of disbelief, we remembered his sayings, his cuttingo of fools, and the kindness he was always ready to show to decent folk in need of a leg up. One incident had

stuck rmly in my own mind and it will be there until I join Davey in the big shipyard down the far blue yonder. I was a young skipper in charge of a yacht with a heavy tonnage and a very large turning circle. One grey morning, the river was quiet, the tide slack and I was manoeuvring among moored yachts under power. I had to turn my boat through 180 degrees and, rather than opting for the prudent method of going ahead and astern, using the prop-walk to make the most of the small amount of space available, I decided to go for an all-or-nothing turn under full power with the rudder hard over. e propeller was bang in front of a large rudder. With lots of grunt coming o the prop, the blade diverted the gushing water, allowing me to swing round a lot more tightly than the yacht’s natural inclination. All was going ne. I was halfway through the manoeuvre and heading brie y towards a row of yachts secured fore-and a on a series of piles when the engine coughed and gave up the ghost. e silence was deafening but the heavy yacht hardly broke her stride. She kept right on going, but bere of her mighty propeller it was soon obvious that rather than get comfortably round, she was going to tee-bone one of the yachts on the trots ahead. I was leaning all my weight on the big tiller with

ABOVE e late, great Davey Elliot

BELOW

Slipping into a simple berth. Would it were always so easy!

ABOVE e late, great Davey Elliot

BELOW

Slipping into a simple berth. Would it were always so easy!

“bereft of her mighty propeller it was soon obvious that rather than get comfortably round, she was going to tee-bone one of the yachts on the trots ahead”

disaster looming and no clue about what to do next when Davey appeared in the companionway of the lovely varnished hull that was plumb in my sights. Taking his pipe calmly from his lips he pointed it to the gap between his long counter stern and the pile to which it was secured with a very large rope. Steering into this dubious haven was a possibility, because it involved easing the tiller. In any case, nobody with any sense of emotional survival argued with Davey, so I did as I was told. As the spoon bow of my long-keeled yacht rode up on Davey’s stern line he whipped a couple of turns o the bollard to which it was secured and expertly surged it away. Somehow, he gauged the friction just right and shrugged o the last of my way just before I hit anything. As the boats slowly came together with no damage at all, the cockpits fell alongside one another and he looked me square in the eye.

“Next time you’re heading for a line of yachts, Nipper,” he

A heady cocktail of tangled ropes, no fenders, confused crew and bemused onlookers – Davey would not have been impressed

said, re-lighting his pipe with much sucking and pu ng, “you be sure to pick a cheap one!”

Tom has been mate on a merchant ship, run yachts for gentlemen, operated charter boats, delivered, raced and taught. He writes the pilot for the English Channel, a complete set of cruising text books and runs his own internet club for sailors worldwide at tomcunli e.com

I think about this incident every week as folk ask me to help with their sailing problems. Looking back on my own career I realise it’s no coincidence that the most popular questions are about manoeuvring under power. Speci cally, how the devil to get in and out of a tideswept nger berth hemmed in by ranks of pontoons sited far too close, and for which the annual fee would buy a respectable used car. Much is written in magazines about sure- re ways of defusing these horrors. Some of them work some of the time, but the bottom line is that there is o en no easy answer.

I always advise marina visitors to tell the berthing master when they call up that they have an awkward boat, that they are inexperienced –whether they are or not – and that they really need an up-tide berth.

Sending people into a down-tide

cul-de-sac with the wind up their chu with a nal tight turn against the propeller is handing them a ticket to nowhere. We must insist on better service, but if there’s no help for it and you’re stuck with a non-starter, it’s a good idea to rig fenders on both sides, remember to keep up-tide when approaching along a pontoon corridor, take your time and work out what’s the most wretched result that can happen if it all goes belly-up. Be prepared for that while hoping for the best,_ and you’re a lot better o than the chancer who comes zooming in with no contingency plan, no fenders rigged and a foredeck crew still trying to untangle a line that’s too short anyway.

While you’re at it, look hard at any potential victims, price them up quickly and make sure you land up on the cheapest. You may not get your knee xed, but you can award yourself a wry chuckle at the end of the day.

“In any case, nobody with any sense of emotional survival argued with Davey, so I did as I was told”

lex omson may have relinquished the wheel when he announced his decision not to go again for the next Vendée Globe, but he has certainly not let go of his passion for solo o shore sailing.

Far from it. For the last 12 months, the ve-time Vendée veteran has been seeking a way to channel his expertise and pass on the knowledge he gained from two decades of campaigning his IMOCA 60 Hugo Boss –during which he broke multiple world records and scooped two Vendée podium positions.

Of many applications and o ers, he has narrowed it down to one. Now, the hard work begins with the announcement of an exciting new partnership that sees Canadian businessman Scott Shawyer as president and omson as mentor of an all-new, fully professional o shore sailing team.

Canada Ocean Racing aims to become the rst ever Canadian team to complete the Vendée Globe. Along the way, they plan to spearhead the development of o shore sailing in Canada by inspiring others, creating performance pathways, and by constructing a groundbreaking, long-term business.

omson will be providing his unrivalled expertise both on and o the water, and says the aim is to enter a competitive boat in the 2028 Vendée Globe; for 2032, the target will be to top the podium.

e current intention is for Shawyer to be the race skipper – but that’s not set in stone, as the scope of this campaign stretches way beyond one person. e team is also considering entering e Ocean Race in future – although the forthcoming start in January 2023 is way too close to be realistic, as is the next edition of the Vendée in 2024.

Instead, this is a seriously big picture campaign in a class that is becoming ever more competitive

ABOVE– not to mention technical, with the advent of fully foiling IMOCAs likely by the 2028 Vendée. But there is both eagerness and con dence, and Shawyer – delighted to have omson’s backing – has described him as “the best in the business”.

Thomson himself is aware of the difference a good mentor can make; several helped shape the early stages of his own career, including Kevin Townsend, Sir Robin Knox-Johnston and Sir Keith Mills – all of whom he says “have had huge influences in my life. Now it’s nice to be able to start doing the same.”

Thomson is already recognised as one of the highest profile ambassadors for our sport; as well as his racing accolades, his trilogy of audacious stunts on board Hugo Boss have drawn many millions of views worldwide, and he has spent many years helping to shape the IMOCA 60 class.

Where next a er years of Vendée Globe campaigns? Georgie Corlett-Pitt chats to Alex omson as he launches an exciting new project…Interview

His role in this new project he says is a “natural t” and – as well as enabling him to spend more time with his young family when not in Canada – he is looking forward to a fresh direction and to promoting the sport to new audiences. “I get to carry on living the dream,” he smiles.

He’s also hugely excited about working with Shawyer, who was inspired to do the Vendée while watching the last edition during lockdown at a time when he was su ering from anxiety, and drew energy and motivation from following the race.

But, surprisingly perhaps, omson’s chosen protégé is no stereotypical rookie, rather a successful businessman with a penchant for adventure and a philanthropic vision to spread the sport of o shore sailing. Equally

unexpected is the fact that, despite being a lifelong sailor, at the age of 50, Shawyer has only a small amount of o shore experience; the delivery of the team’s newly acquired IMOCA 60 from Portsmouth, UK to Halifax, Canada, coming as something of a baptism of re. His previous sailing experience had largely been in dinghies, A-Class cats and cruising yachts, but for a man who counts trekking to the North Pole for charity, and representing Canada in downhill ski racing among his other sporting achievements, he is clearly not short of grit.

He also has, according to omson, a deep-running passion for the sport together with resolute determination and a proven ability to commit – traits which omson himself identi es with, and which

ABOVE LEFT Canada Ocean Racing's newly acquired IMOCA 60

ABOVE RIGHT omson in pensive mood

BELOW Entrepreneur, philanthopist, adventurer and potential future Vendée skipper Scott Shawyer

are fundamental building blocks in a campaign of this sort.

“He’s an inspiration. I take my hat o to him, I really do,” omson says. “ ere are lots of things you can teach about the sailing part, but you can’t teach the desire and you can’t buy the desire – that has to come from within.”

e newcomer now faces an intense sailing programme of 30,000-50,000 miles a year, set out for him by omson and with full support from omson’s highly respected campaign management team. It will be the springboard Shawyer needs to succeed in his ambition – but it won’t be easy.

“He’s a lot less emotional than I am,” omson appraises. “He’s analytical and constantly wants to improve; he’s happy to take constructive criticism. But for someone with that amount of success in other areas behind him, it’s hard to be at the top and go right back and start again.”

omson himself is relishing the opportunity to impart his knowledge to someone so determined. Coaching clearly comes naturally, as he describes himself as being from a “sailing school background”; his own big break came when he famously skippered a team of amateur sailors to win the 1999 Clipper Round the World Race, aged just 25.

But even throughout his own successful career, the o shore pro admits he hasn’t launched a programme as comprehensive and far-reaching as this.

“We’re starting from scratch,” omson explains, as he outlines Canada’s currently scant opportunities for o shore sailing. “We want to be able to thread the Vendée into people’s lives in Canada. We rst need to build an audience, and to do that there’s no better way than to have the boat there, have people see it, feel it, and talk to the skipper, the crew. Our plan in touring the boat in Canada over the next two months is to connect with people and tell the story. Once we have proved the value, then we will have a starting point for how this is going to work commercially.”

omson is unlikely to pick any sort of “quick hit solution”; he reveals it took 11 years for his Hugo Boss-sponsored endeavours to attain the top levels of campaign budgets and attract others such as Nokia to the fold. “ is is a strategic plan,” he says, noting the risk of under-selling the campaign in the shortterm. “As much as we would all love it to be a non- nancial thing, ultimately money matters and you have to be able to raise the right money to give you the right tools to fully do the job.”

Shawyer will bring another level of business acumen to the table – gained through 25 years as president and CEO of leading industrial automation and systems integration company

JMP Solutions – and with it a unique advantage that has led omson to a rm, “With that kind of knowledge, con dence and ability to achieve, I’m happy to stand behind them because I do, I totally believe.”

The challenge comes in applying this to sailing and to capturing the attention of Shawyer’s home nation. But with 30 percent of Canadians speaking French and given the huge popularity of offshore sailing among the French, Thomson is positive about gaining traction. The international fanbase for the IMOCA class he says is “rising exponentially” and he points to Germany’s debutant skipper Boris Herrmann who shot to “national hero” status following his fifth place in the last Vendée Globe. “With a few more countries involved we will end up truly global; I really want to be part of that story, to build-up the Vendée and this part of the sport into something big,” he says.

In addition to their current boat tour and ongoing fan engagement activities, Canada Ocean Racing’s campaign will

ABOVE e boat was launched in 2011 under the name Acciona and is very much a means of getting the team up to speed with the challenges of sailing an IMOCA 60

BELOW

Shawyer brings business acumen, enthusiasm and drive to the project

also create youth and female talent pools, and an inspiring platform for the next generation. Training initiatives for support roles in rigging, composites and so on, will help form a much-needed technical skills base and network in Canada.

For now, the team will train using an IMOCA 60, launched in 2011 as Acciona , more recently campaigned by Offshore Team Germany in The Ocean Race Europe. A new boat is likely to follow the 2028 Vendée, the team not wanting to risk reliability issues ahead of the start. Instead, the focus will be on competing in the IMOCA Globe Series to build experience ahead of qualification for the 2028 Vendée. With more and more skippers being drawn to this pinnacle solo circumnavigation, ensuring a spot on the startline is likely to become more difficult, and Thomson knows that consistency is critical; get the fundamentals right and performance improvements will naturally follow.

Their target of winning in 2032 is, after all, a decade away.

“Scott is not just buying a boat and going off and doing it; he’s committed to doing it properly and I’m excited to see how far this person can go,” he says. “I don’t want to put any pressure on, but I’ve got high hopes for him.”

And might Thomson feel any regrets at not being on the startline himself? “Maybe, a little,” he muses – but it’s something he tries not to worry about. For now, it’s about enjoying the start of a new chapter in his own career, and in that of ocean racing.

ur intention for the summer of 2021 was to sail our Westerly Fulmar, Ophelie, from our Marconi Sailing Club mooring on the River Blackwater in Essex, up the east coast travelling anti-clockwise towards Scotland. ere is not the space to give a full account of our journey, so this is just a small part of the adventure.

Finally ready, my wife Jane and I, accompanied by our friend Peter set o for our shakedown sail, restoring our sea legs, in home waters via West Mersea, Brightlingsea and on to the River Orwell with the hope the weather would change its mind. Slogging up the Wallet while it blew a vigorous north easterly, the wind over tide produced rather uncomfortable conditions. is was not a very favourable prospect for the next 300-plus miles.

Looking at the weather charts for the following week, I suspected the wind was going to stay in that direction for some time, so a change of plan was rapidly drawn up; we would go clockwise and along the south coast. I understand there is a ‘law’ regarding this phenomenon, so we sailed, in

e west coast of Scotland is acknowledged as one of the nest cruising grounds in the world. Mervyn Maggs spent a summer exploring

southwest/northwest breezes, as far as Plymouth where Peter sadly le us. From here, Jane and I pushed on up the Irish sea and on to our goal of Troon in bonny Scotland, and this is where this bit of the story will begin. is year was blighted with Covid, but as some compensation, the weather as we went further north so ened down and we could move on most days. e plan was that friends, Lawrence, Helen and Benjamin would drive up from Maldon to crew on this part of the voyage. For Lawrence this was a test of his memory and fond recollections of his stomping ground many moons ago, where he learnt to sail in his youthful innocence. All the extra essentials of our crew were stowed in every nook and cranny, hoping that we would all work well together and not wake anyone up in the night due to the necessities of age.

Casting Lawrence’s memory back possibly 40 years of sailing on the Firth of Clyde, we planned to voyage to Oban, with its handy railway connection, so they could return to Troon to pick up their car and go home. On our rst night together, we treated ourselves to some of the nest sh and chips bought from a shop on the sh dock. To prove the excellence, we queued for at least half an hour to order, and another 20 minutes for it to be cooked. Everyone in the queue exclaimed it was worth the wait. Talking of sh, Benjamin thought he might just dangle a line over the

side to pass the time in the marina and to everyone’s surprise he caught a mackerel. is took us all aback and it was decided to return the sh to its habitat in the crystal-clear water full of small shoals of sand eels and fry. is year the water was exceptionally clear, and we surmised it might be because of the minimal rainfall and the lack of peat being washed into the sea from the land.

Sailing from Troon northwards, our rst anchorage was at Little Cumbrae, sailing in light winds that proved to be a good speed for shing. We caught two mackerel that made a delicious starter that evening. We arrived a er ve hours and anchored behind Castle Island where Helen and son went to explore the Castle using the in atable dingy in this quiet and picturesque anchorage; the dingy is a great asset for these parts.

Anchor up the next morning and we made our way east of the Isle of Bute in the Firth of Clyde

along its corridor of high ground that receded into the Kyles of Bute. e shore around us grew and the channel narrowed, heightening our expectations of what was to come, and we were not disappointed.

Wiggling our way through the Eilean Buidhe, we passed Eilean Mor in limited depth to nd an anchorage just inside Caladha Harbour, to the northwest of Eilean Dubh, in very shallow water and mud ground. Luckily for us we found a place to anchor, as space is very limited. e harbour boasted a lighthouse at one end and proved good for exploring in the dinghy.

e following day we made our way down the West Kyle to Ardlamont Point and headed north to East Tarbert as our next port of call. East Tarbert proved to be a lovely harbour, providing some good walking and a castle to explore. Jane

and I investigated the possibilities of eating out in order to sate our desire for some of the infamous sea food of this area. ere were lots of places to choose from, but they were mostly booked up and o ered too little of what we wanted. Also, we had a desire to eat kippers from these parts, as Loch Fyne Kippers are regarded very highly. So, spotting two old boys drinking in front of a pub, I asked them their advice on purchasing some kippers in the area. Without hesitation, they told us of a local shmonger just around the corner where there would be kippers and much more. ey highly recommended the smoked haddock, the chosen sh for the west coast. It took a while to nd the shop, tucked away down an unmarked alleyway, out of sight of most tourists. We all returned the next morning to buy fresh langoustines, smoked haddock and, of course, the kippers that sated our appetites.

ABOVE LEFT Looking down on Loch Tarbert

BELOW LEFT Beautiful conditions at Eilean Dubh

Waiting for a lock in the Crinan Canal

Moving on to the Crinan Canal, having booked ahead as required due to the limit on boats that are able to transit, and the reduced opening times of the canal. In preparation we carried a fender board, plenty of standard fenders, two round buoys for springing o plus two long lines. Self-su ciency is required to travel the nine-mile canal, which can apparently be transited in just six hours, but only when it’s fully operational and you have the energy. Further to this, the locks have a high rise and fall, requiring assistance ashore to open and close the gates, long lines and the ability to pass them up to the bollards. We found that a crew ashore, plus two long boat hooks were a very good way of dealing with this.

We arrived at Ardrishaig in the pouring rain at the designated time, crew ready, oilies on and went straight into the sea lock, ready to take on the task at hand. We were

assisted by the lock keepers at some points of that day’s journey through four locks and under one bridge. It was great having crew, I was on the helm and just pointing the boat in the right direction while Jane, Helen, Lawrence and Benjamin all did their bit of taking lines, opening and closing lock gates. For this part of the journey, we decided to take the lock keepers advice and stop before lock ve at Cairnbaan to enjoy the scenery and the pub. The following day we paired up with another Westerly Fulmar that had a willing crew on board, halving the work through a further nine locks and two bridges. Finally, we entered the Crinan Basin and tucked into a snug berth for the night alongside a grass verge in what is a small harbour. We found a café supplying coffee and cakes plus the added benefit of a Clyde puffer tucked away in its berth.

We were lucky to only catch the end of Highland Week, which could have made life extra complicated through the canal, due to the higher number of boats. Luckily, we were heading in the opposite direction as we locked out through the nal sea lock into the Sound of Jura and went onto Oban Marina on the Isle of Kerrera. Here we had a pizza under Covid conditions eating plein air. A request by Benjamin to have square onions on his square Pizza, was met without a blink in our order. We all slept soundly that night. e following morning, we slipped over to the Oban Transit marina to say a sad goodbye to our crew and friends, who caught the train back to Troon to pick up their car and head home.

Oban is a bright bustling port/ terminus with ferries going to all the various islands. ere are also many good shops and places to eat, as well as being an interesting location especially if you like amphitheatres.