44 minute read

Building belonging in both places: Learning to adapt to different paces of life at home and at university

from 0th Week Hilary 2022

by Cherwell

Becca Funnell discusses enjoying solitude and being mindful whilst transitioning between living at

Iremember anxiously sitting on the kitchen floor at home just before Hilary Term in my first year, telling my family how I didn›t want to return to a place where I had few close friends and I felt pressure to show my tutors I was “good enough” to be there. I did not feel like I belonged.

Advertisement

It took the best part of two years for me to build the sense of belonging I have now. These days I feel most myself when I’m living in college with my fantastic roommate; when a friend hears me laughing across the quad and sticks her head out the window to shout hi; and when I’m among the sweaty joyful mass of Wadhamites at the end of a BOP, stubbornly refusing to give up on swaying with a person on my shoulders until the end of ‘Free Nelson Mandela’.

My problem now is that I miss all these things during the long Oxford holidays, and I struggle to feel like myself. My frustration at being stuck in the middle of nowhere, coupled with worrying that I’m not getting enough done and feeling lonely at times, makes me pretty gloomy. This version of me feels so different to how I am at uni, and I don’t like it, which adds to the general gloom.

One person I’ve been inspired by regarding this issue is the author Katherine May who uses the word “wintering” to describe the practice of slowing down, resting, and retreating. For me, the holiday is a kind of enforced wintering, where I don’t have any other choice but to slow down quite abruptly from the exciting chaos of term. Borrowing May’s perspective, I can begin to see this slowing down not as a bad, boring thing, but simply as a change in pace that allows me to rest, reflect, and find a new way of living with different habits and routines. Creating these new habits and breaking out of term-time patterns often isn’t easy. One friend told me that she takes herself out on a solo walk every day, giving herself “thinking time” to reflect on how she is feeling. Although it sounds like a pretty middle-aged habit, I’ve also started making this part of my life during the holidays. I find so much joy in exploring green spaces around where I live, and it definitely has helped me reflect, creating more space in my mind to calmly process. This in turn allows me to enter a state which psychologists call “flow” which involves the practise of deep concentration, enabling me to let go of time and of my problems. Sound good to you? Then I really recommend trying a calm slow walk, or another activity like drawing or yoga, and paying attention to your thoughts.

As well as giving me the space to think and reflect, walking is one way I can enjoy spending time alone. Being alone can seem like quite a scary thing sometimes. In a world where social media is flooded with images of people doing awesome things together, aloneness is portrayed as a bad thing, synonymous with loneliness. We forget about the other side of the coin to loneliness – solitude. Stephen Batchelor, Buddhist teacher and author, talks about solitude as an “art” or a “practice” that enables imagination and creativity, offering a much-needed positive perspective on aloneness. His view on solitude is that it can only be found by getting in touch with your physical and sensuous body. I agree that being less in your mind and more in your senses is central to enjoying aloneness. Recently on my walks I’ve started to engage more sensorially with the spaces around me: touching leaves, hugging trees, the whole shebang. I get a lot of funny looks when I tell people about this, but you can’t knock it till you try it, and I promise it will help you get more into your senses.

Another “practice of solitude” that has helped me with my university to home transition is journaling. Like many people, I don’t have the patience to write a detailed diary so I use a very systematic list-like way of journaling that takes me about 10 minutes before bed. The general structure goes as follows: 1. “Today, three moments/things/ people I am grateful for are…“ 2. Something I did that day that was brave or new 3.A super quick description of my day 4.A check-in with how I am feeling – “I feel…” 5.A phrase that gives me perspective on whatever I have experienced that day. “It took the best part of two years for me to build the sense of belonging I have now..”

E.g.: “you live and learn” and “nothing is worth sacrificing sleep over” This way of journaling ensures I’ve processed everything that happened in a day so I can get a good sleep, and it provides many laughs when I read back particularly dramatic entries - the ones I write after a night out are hilarious and mostly illegible. Most importantly, it helps me work out what has affected my mood and what has brought me joy. By reflecting on my daily activities whilst living at home, I have been able to create new patterns that leave me feeling fulfilled, and like I belong. The number one thing I find myself grateful for at the end of the day are the people I’ve been around and the conversations we’ve shared. Reflecting on how much people mean to me prompts me to put an effort into connecting with friends from uni during the holidays, as well as spending “Being less in your mind time with friends and family at home. and more in your senses Connecting with is central to enjoying aloneness. ” people both indirectly and directly makes a huge difference to my happiness and sense of belonging, and its only something I’ve realised through practising solitude. There is a paradox here: by spending time alone and turning inward, we discover the value of human connection and togetherness. I find practising solitude and building belonging as practices really encouraging. This perspective frees me up to keep learning new ways of living without the pressure to get it right the first time, and dissolves the stigma attached to periods of loneliness. It›s all a constant work in progress. While it might seem daunting that we will never really be done with finding our belonging, I think its much better than unconsciously moving through our lives without reflecting on what makes us feel good at the end of the day. Without this reflection, we tend to subscribe to how someone else defines a “good life”.

John Evelyn

An inside look at the Oxford Union

Much like John Evelyn, the union has decided that, after a long spell of messy and toxic matchups, this term it’s time to branch out and try a three-way.

You might recall that the last time something similar happened, the Union was about to couple up with an Australian gentleman, but some chap called Ron got in the way. As is often the case when one’s first option falls through, the Union ended up in a four-way with some slightly older folks and things got a bit weird. Hopefully, this time, the longer build-up will mean everyone is more comfortable when the moment finally comes.

The Rapid Climber has reConnected with the dynamic duo that is European Girlboss x European Boyboss. The LMH Enforcer, on the other hand, was Inspired by the musical clout of David Guetta and the career prospects of the Campus Ambassador. John Evelyn hears he is planning a 70 person slate social this Saturday at LMH in paralysing fear that he might not get his campaign started soon enough. The Univ Queen has renewed her OUCA Prime subscription and express-shipped two veteran hacks from the university’s other favourite society. John Evelyn hopes she remembered to put the purchase on her personal debit card and presents her with the Garbage Collector of the Week award for reaching deep enough into the bin to pull these two out.

It’s dating season in the union, as each slate desperately tries to fill its final officer position. John Evelyn has heard that the ROs are thinking of putting all the slate leaders and eligible single hacks on an island together to see if they can find The One. They say there are many Fish in the sea, but at present no one seems to be getting any bites. Senior appointed are currently sheltering together in a coffeeproof bunker, however a little birdie told John Evelyn that one member may have been temped over to the electoral dark side…

Meanwhile, all wait with bated breath to see who, if anyone, the Privately-educated Progressive will look down upon favourably from her high throne. We can only wait and see whether this planned three-way does indeed come to climax, or if someone pulls out beforehand with cold feet. More to come. John Evelyn x

Daniel Moloney Second Year Brasenose College History Cherpse!

Daniel and Eliza

Eliza Browning Third Year LMH English

First impressions?

She was sweet and fashionable.

Did it meet your expectations?

Surpassed them – I was unsure what to expect.

What was the highlight?

Both of us trying to fgure out if we were each other’s blind date.

What was the most embarrassing moment?

I asked what her name was twice.

Describe the date in 3 words:

Interesting, funny, great.

Is a second date on the cards?

Yep.

Looking for love?

Email cherwelleditor@gmail.com or message one of our Life editors!

First impressions?

He’s really cute and I liked his jacket.

Did it meet your expectations?

She was really nice and easy to talk to.

What was the highlight?

Yes! We had coffee and an interesting conversation for about an hour.

What was the most embarrassing moment?

We both looked around for each other a bit and I was nervous to say anything in case it was the wrong person. Luckily I was right.

Describe the date in 3 words:

Fun and relaxed.

Is a second date on the cards?

Yes :-)

Words of Wisdom from...

RUSTY KATE

*WARNING* This mildly comedic column has been written by a drag queen agony aunt. It is not for the faint hearted and contains sensitive topics which may cause distress to some readers. Be prepared for dirty douche water, relationship issues, adultery, and fnding out why your Dad never loved you. Hate men? Losing the will to live? Wondering how to remove that Alpecin-Caffeine shampoo bottle from your arse? Good old Aunt Rusty is here to help! Rusty Kate is Oxford’s premier cum-flled crossdresser, known for turning looks, tricks, and straight men seven nights a week. She’s decided to take a short break out of her busy schedule of carrying Plush’s Drag & Disorderly shows to act as Cherwell’s Dragony Aunt, and help sort out your pathetic little lives one horrendously uncensored column at a time. Remember to submit your questions through the link on the Cherwell Facebook page – you’re guaranteed complete anonymity. Unless you lose an Alpecin-Caffeine shampoo bottle up your arse (looking at you, Ben Jureidini) Right, onto the issues that the SU are currently writing some very important petitions to the university about… Dear Rusty, I think I fell in love with one of my closest friends last term. I thought the separation from her over the vac would help me come to my senses, but I think I’m still in love with her. Is it in my head? Am I confusing close friendship with romance? Do I tell her knowing she probably doesn’t feel the same? Help an emotionally confused gal out!

Love is always in the head, dear. Just give her some and I’m sure she’ll give you a yes or no answer. You do need to tell her how you feel, though. There’s no use bottling all it up just for it to all come squirting out later (that’s how lesbianism works, right?). In the words of the great Macklemore, love is love, and by the sounds of it, you’ve got some loving to give her. Romance and close friendship can be hard to separate, especially as queer people – we shag our friends, and are borderline celibate with our partners. Why not ask her out with the angle of an open relationship? Those always go well!

How the hell do I fnd someone who is not completely insane, not a weirdo and just interested in something casual? I want a no strings casual hook up - is that too much for a girl to ask for? I’m dying here, Rusty, help. Where are all the hot men hiding?

Darling, the answer is simple – all hot men who are completely devoid of attachment or any ability to sustain intimacy are gay. You’ll fnd a plethora of options on Grindr – bisexuals and homofexibles alike will be perfectly happy to give you everything and more, as long as it’s seen as casual. They don’t want to meet your parents, but they will pound you close enough to death that you’ll be meeting your maker. Just remember, the diamond emoji doesn’t mean they like jewellery – you’ll need to bring something smokable for those types. How can I get out there without using dating apps? Go out there just like your mother used to do, the good old-fashioned way. I’ve heard the hard shoulder on the M40 is a good place to meet people.

The British higher education system: Rigorous or rigid?

Viren Shetty discusses the failings of the British education system and looks to other countries for a solution.

‘I first realised I wanted to study History and only History when I was 7 and visited the Tower of London on a school trip. From then on, History was the only lesson I looked forward to and became all I wanted to study all day every day.’ I’ve endured almost three years of study at Oxford and, more recently, spent hours trying to convince employers that the skills from my degree really are ‘transferable’. Reflecting now and comparing myself to others around the world in the same position, I’m forced to ask whether I really was speaking honestly at interview or if a couple of Maths or Economics courses in my third year would have served me better for the world of work ahead. Choosing one or two subjects to study at university at 18 seems like a very normal, natural progression in the English system. Eleven subjects at GCSE, three or four at A-Level and then, finally, you pick your favourite one. Oxbridge interviews are set up not only to find the most gifted at particular subjects, but those most passionate. ‘Passion’, we’re told, is what will get us through twelve essays a term in the same subject, every term, for three years. The vast majority of university students, however, are not passionate enough to take their love of their subject further. Love for one’s subject mysteriously, and quite suddenly, peters out in the third term of one’s third year as most of us hit the job market and the idea of masters or PhD level studies terrifies us. An education system which takes this ito account, which isn’t gearing us up to fall in love or out of love with the academic profession is surely more desirable. Being forced to or even just having the option to take a wider array of courses ought to make us more attractive on the job market and prepare us for life. Taking this back further, a broader 16-18 curriculum, which doesn’t let us drop Maths, essay subjects or

numerical, reasoning and language skills to refer to. However, this isn’t an argument for general studies courses or more practical education post-16. It’s a case against siloing young adults into specific departments and in favour of interdisciplinary studies. The liberal arts program and high school curriculum in the United States speaks

volumes for the advantages of an interdisciplinary education. Many universities lay out compulsory courses in essay-writing, modern foreign languages or science for freshmen and sophomores, while allowing students to pursue their interests by majoring and minoring in subjects in their final two years. It also gives university professors a lot more freedom to curate interesting, popular courses that don’t necessarily fit within a particular department’s framework. ‘Beyoncé Feminism, Rihanna Womanism: Popular Music and Black Feminist Theory’ at Harvard or ‘How to Stage a Revolution’ at MIT are two examples of ‘out-of-the-box’, interdisciplinary courses that we rarely see the likes of in the UK. In an academic climate gripped by movements to diversify the canon, encouraging universities to make their options ‘popular’, to fight it out on the ‘student market’, is surely a good thing.

The English academic’s rebuttal would be that three years of specialised learning in Biochemistry, Classics or Maths takes one to a far higher standard than one could get by taking a few ‘major’ modules a year. The liberal arts education leads to a surface-level understanding of a few subjects, without taking you to the depth of knowledge which you would need for ‘proper research’ to really add something to the discipline with your final dissertation. There is a case for specialisation in certain subjects in which knowledge is cumulative. This is particularly evident in subjects like Law or Medicine, where the English system somewhat ‘fast-tracks’ 18year olds and shaves a couple of years off their professional debut. However, the case for a multidisciplinary approach in the humanities and even some science subjects is strong. From personal experience, I would argue that being able to take papers in Philosophy, Economics and English would add significantly to my study of history and might mean I didn’t ignore the parts where politics becomes ‘mathsy.’ Equally, the benefits of interdisciplinary ‘modes of thinking’, applying a ‘scientific brain’ to ‘artsy questions’ have been well researched and argued. Moreover, few would suggest that top institutions in the United States, Continental Europe, or Asia are hampered in the quality of their graduates, teaching staff or research capabilities by a secondary or tertiary education program which does not encourage specialisation. In fact, exposing students to new subjects, ones which they might not have considered at school level, can give birth to high quality graduates and researchers whose passion for their subjects started late in their academic careers. Multi-disciplinary study at university could also help to address this country’s youth employment or higher education crisis. Ever since increasing numbers of young people started attending university at the start of the century, cries about ‘pointless degrees’ or ‘too many people going to university’, often from the right, have dominated debates about the place of universities in society. If we do want to maintain higher education as a valuable tool for social mobility, perhaps broadening curricula, even at top universities, is the answer. Perhaps it could encourage universities like Oxford to consider our education holistically: what skills do we really want to come away with, which untapped areas do we still want to explore? This would evidently be more beneficial than a drive for first-class degrees at any cost and, in the Oxbridge context, competition between colleges and within departments.

While Liberal Arts courses have popped up at a number of institutions in the UK, the norm still remains the specialised degree and the underprepared graduate. Even the process of choosing A-Levels is a restrictive process for young people. Students are often likely to pick their options based on particular departments’ track record or the ease with which they can achieve top grades. The decision to drop a particular subject simply because of a bad teacher, department or school type is evidently restrictive and problematic. Often the case for taking a particular subject is strengthened by a particular charismatic teacher or which subjects are deemed popular. Many schools, moreover, are pressured by the harsh quantitative scrutiny of league tables to push students into taking ‘easier’ subjects or those taught by the best department. The positive feedback cycle here is damaging: worse departments with fewer students at A-Level end up receiving less funding, and so on. For certain subjects, this can also feed into a worsened state-private school divide once at university, with subjects like Classics often seen as the domain of the economic elite. With the aim of equal opportunity, therefore, a less narrow school-level education may be a solution. The most obvious argument for specialisation at A-Level arises from the fact

that everyone has different strengths. We should allow teenagers to express their individuality, choose their subjects and excel in their strengths. This is rooted in a particular view of education which sees all children as different, with different processing abilities: people think in different ways and everyone has their own strengths. Not letting people drop subjects which they’re bad at could lead to disillusionment, poor mental health, and all-round negative associations with school. Letting every teenager choose their own subjects, it is argued, allows them to engage with their interests and fulfill their potential. A-Levels, moreover, aren’t mandatory. the standardised English education system ends at 16, with a range of options, from BTECs to the increasingly popular apprenticeship scheme, available after. Those who argue in favour of a more ‘practical’ education often focus on the fact that ALevels are not and have been increasingly less important for career aspirations. This isn’t unique to England: Germany has Berufsschule (‘vocational schools’), which allow those over 16 to study alongside a three- or four-year apprenticeship, while France has a separate stream for those who want to take the ‘vocational baccalaureate’. Mandating a core curriculum until 18 is, therefore, potentially linked to the United States’ higher high school dropout rate than the UK and more general dissatisfaction with education.

This is compounded by the fact that the A-Level system is very popular. The English Education System is, undeniably, quite highly regarded around the world. Cambridge International A-Levels are taken by the economic elites all over the world, from Hong Kong, to India, to South America. They are seen as a gateway to academic success, to prestigious higher education institutions and a demonstration of true academic mastery. It’s important, however, to deconstruct this reverence for English schooling. Education has been an area particularly defined by the colonial experience in many countries around the world. The idea of being part of an educated super-class still runs deep and possibly shapes existing feelings of respect towards the A-Level system. Alternatives are on offer within the UK too. Scottish schoolchildren take more

subjects to Highers Level and many private schools have opted to also offer the International Baccalaureate, which forces students to pick a true range of six subjects, taking three to ‘Higher’ Level. The impact of the IB on low-income US students was found to create ‘more rigorous classrooms, students who participate in more extracurricular subjects and who had greater higher educational aspirations.’ However, the likelihood of us as a nation or schools more generally switching to such a system appears unlikely. Gavin Williamson, former Secretary of State for Education, recently said that the purpose of education is to ‘give students the skills for a fulfilling working life’. While the answer to this could be vocational training from a young age, I’d argue that the key to a more ‘useful’ education is to treat young people as individuals and parts of the workforce, rather than as potential future academics. A more holistic education, one which accepts a need for depth while maintaining linguistic, literary and numeracy skills developed from a young age, could reinvigorate teachers and students and improve falling university satisfaction rates.

Editor’s Response

The Cherwell Features Editors give their thoughts on this week’s article.

Jessica DeMarco-Jacobson

While the grass may seem greener on the other side, the American education has its share of issues. One of the major issues in the system is the lack of cohesion. Each state has its own standards, so curriculums are different depending what state you live in. As someone born and raised in Georgia, I experienced the effects of this frsthand. I attended half of elementary school in a low-income area, and I distinctly remember the tattered textbooks and supplies that the district provided the school.

My mother (who works as a public elementary school teacher) has often expressed her frustrations about the school district. The gives teachers only a short time of the day to teach social studies and science, putting less importance on those subjects. Because her school is in a low-income area, it receives extra funding. However, the Title I program provides only $500-600 of funding per student per year and often fails to improve school services and activities. In brief, the American education institution may look better on paper, but in reality, it suffers from many systemic complications.

Leah Mitchell

I started my secondary education in the International Baccalaureate (IB) system, following the Middle Years Programme (MYP) framework. When it came time to apply for my IB sixth form subjects, I hit a snag; it turned out that although I had thought being able to take six subjects would grant me greater breadth and fexibility, in fact the strict requirements on which subject combinations I had to take combined with the diffculties for the school of effectively timetabling students for so many different lessons meant that I was not able to take the subjects I wanted.

Ultimately, I ended up moving to another school and taking four A-Levels and an AS level instead, granting me both my desired amount of breadth and the fexibility which, counterintuitively, I found lacking in the IB system. Although I went on to study a single subject at university, I chose one (Classics) which I felt to be inherently interdisciplinary. I can well admit the value of a well-rounded education - but we should not jump to conclusions about how this goal is best achieved.

Hope Philpott

As a fellow History student, I share Viren’s concern at the potential uselessness of our single honours degrees when we step into the real world. I fnd it sad that at age 14 I resigned myself to nine subjects, at 16 to three and at 18 to one, because that’s all my school offered and I was told a single honours de -gree was less competitive. I also envy the diverse learning experiences of other universities and programmes. Years abroad should not be restricted to languages courses as they are at Oxford; they should be encouraged and subsidised for all students. I believe in education for education’s sake, because I think learning is pretty powerful. The current UK education strips students of the right to enjoy an interesting range of subjects for longer, and break up historic tomes with some coding, theories of music or differentiation.

In Conversation with Lech Wałęsa

Charlie Hancock interviews the former President of Poland, Leader of Solidarity, and Nobel Peace Prize laureate Lech Wałęsa about the fall of Communism in Europe, and the rise of populist leaders in Poland and Hungary.

There can’t be many people who have inspired both an opera and a U2 stadium anthem. President Lech Wałęsa may well be one of the most famous electricians in the world, having been awarded the Nobel Peace Prize win 1983 for his non-violent agitations against communist rule in Poland as leader of the Solidarity movement. The frst recognised independent trade union to be recognised in a Warsaw Pact country, Solidarity directly caused the end of communist rule by pressuring the government to hold an election in 1989, which saw Wałęsa become the frst President of Poland to be elected by popular vote. We speak via an interpreter over Skype. Wałęsa is in Gdańsk, the city which includes the enormous shipyards where Solidarity was born. He is an animated speaker, gesticulating freely to emphasise important phrases. He still has his iconic moustache which made him instantly recognisable in photographs from the time, albeit now white and slightly more groomed. He’s wearing a grey rollneck sweatshirt bearing the KONSTYTUCJA – ‘Constitution’ – slogan which has become a symbol of protest against the populist government. He wore a similar shirt to the state funeral of President George H.W. Bush, and has even said he will ask to be buried in it. Wałęsa describes himself as a practical man. which affects not only the way he approaches problems, how he breaks their solutions down like an instruction manual. Practicality, to Wałęsa, emphasises action and learning from one’s mistakes for the future, even if those mistake are painful. “I never forget anything I have practiced. I have eight children with my wife!” he says mischievously at one point Wałęsa’s success as a labour organiser can in part be attributed to this practical approach, and his persistence in organising industrial action and negotiations. He attributes his drive to stand up to communism, despite its risks, to his upbringing. “I took it in with my mother’s milk”, he says, adding that his family had a history of anti-communism. “Whenever there were conversations about anti-communism at home, I lapped it up.” The People’s Republic of Poland was formally established in 1952, seven years after the Red Army ‘liberated’ Warsaw and established a provisional communist government. “The Communist system was imposed on Poland after the war. It was never accepted by Polish people,” Wałęsa says as we discuss the history of anti-communist resistance in the country. The post-war years saw severe political repressions, and a state of near civil war as partisans loyal to the government on exile who had once fought against the occupying Nazis turned their attention to the communist authorities. Both partisans and civilians were subject to mass arrests and executions. Anticommunists responded by attacking prisons and detention camps, attempting to free the political prisoners they held. “In the 1940s and 50s we tried an armed struggle – that didn’t work. In the 60s and 70s we tried strikes – that didn’t work”, he says, refecting on how opposition to the Communists changed. The strikes of the 60s and 70s may not have led to the fall of the regime, but they taught Wałęsa and other activists hard lessons which led to the later success of Solidarity. March 1968 saw protests erupt across the country against the government over the high price of food, and frustration that the promised liberalisation under Gomulka’s leadership had failed to materialise. The month also saw protests by students, writers and intellectuals who were branded as Zionists, with the explicit implication that the dissidents were not Polish. Wałęsa encouraged workers at the Gdansk shipyard not to join the supposedly spontaneous protests against the dissidents which were sanctioned by the government. The shipyard because the centre of huge protests in December 1970 against rising food prices. The strikers, which spread to cities across Poland were met with gunfre, killing 45 and injuring 1000 people. He lost his job at the shipyard, was arrested multiple times as punishment for this agitation. But as an organiser of further protests, he got results. Further mass-protests and strikes in protest against high food prices, and in favour of gaining greater civil liberties erupted in August 1980. The strike in Gdansk was ignited by the fring of Anna Walentynowicz, a crane operator who had been involved in organising earlier protests. The striking workers successfully pressured the shipyard’s management into meeting their demands over pay and labour rights. The resulting Gdańsk Agreement, signed by the strikers and communist authorities, permitted the formation of trade unions which were unaffliated with the state. Solidarity was founded as the country’s frst free trade union on September 22nd. “Many of the people at the top of the Communist pyramid studied in the West,” Wałęsa explains. “They were slightly sceptical and they weren’t so much trying to defend Communism as they were trying to defend their positions of power. So it was possible to do a deal.” The Gdańsk Agreement didn’t stop the government from imposing martial law in December 1981 to counter political opposition and Solidarity, which represented a third of the working population. Wałęsa was arrested, as were 6000 other Solidarity activists, and imprisoned for almost a year. Solidarity moved underground, albeit with the backing of the CIA who provided funding, organisational advice, and helped them spread their message through clandestine newspapers. Wałęsa tells me that Solidarity’s resistance through his time is thanks to the organisation’s determination and reasonableness: “Communism couldn’t combat that.”

After his release, Wałęsa was awarded the 1983 Nobel Peace Prize for “non-violent struggle for free trade unions and human rights in Poland.” He didn’t collect the award in-person in Oslo, fearing that he would not be allowed to re-enter Poland. His wife Danuta accepted the award on his behalf.

Despite the international acclaim Wałęsa has received for his undoubtedly enormous contribution to the course of history, he has been facing accusations that he had acted as a paid informant of the secret police in the 1970s. Wałęsa has denied these accusations, claiming that they are politically motivated. A special court cleared him of charges of collaboration in 2000. The controversy reared its head again in 2016, when documents which appeared to show his involvement were found by the Institute of National Remembrance, an organisation dedicated to identifying and archiving crimes committed under the Soviet and Polish Communist regimes. Again, Wałęsa defended himself, saying that the documents were forged to discredit him. Historians have acknowledged that the secret police used to fabricate documents to compromise members of the opposition.

What made Solidarity different from previous movements? The movement’s size and breadth meant that it encompassed otherwise polarised facets of Polish society: the anti-communist left and political right wings, liberals and nationalists, and the intelligentsia and workers, as well as atheists and believers. Wałęsa tells me that the hatred of communism acted as a common denominator between these disparate groups. “Through a system of trial and error, we realised if we all came together in solidarity we could achieve success. We realised we had to be a monolith to stand against communism.” “When the Soviet Union collapsed, we lost that common denominator. In modern times, we no longer have that to unify different people.” Wałęsa answers become longer as our conversation turns to the present political situation in Poland, pausing more regularly so our interpreter can keep pace. His presidency saw Poland transition towards a free-market economy under the Balcerowicz Plan. He tells me he sees the present political order as going through a transition of its own – a transition from an age where nation states defne the world, to an age of continents and globalisation which he believed is yet to solidify. He calls this in-between state the “Epoch of the Word and Discussion”. What kind of discussions are taking place in this epoch? Wałęsa breaks the answer down into three questions. What should the coming epoch be based on? He identifes a confict between people who want to build a society on freedoms, and those who say that we can only start talking about rights once the core values of a society have been laid out. What should the economic system be? “Certainly not communism,” he makes clear. “Not because it’s good or bad, but because it’s never worked anywhere.” But equally, the current form of capitalism won’t do. “It worked for the old system of states and countries. But it led to a rat race of nations, which led to mass unemployment. Many people just couldn’t keep up with the pace.” His third question is one I knew I wanted to explore the moment our interview was confrmed: How do we deal with the demagoguery of populist politicians? “Populists and presidents give the same diagnosis, that everything needs to be changed. It’s just that the populists’ solutions to the problem are wrong.” Wałęsa is a ferce critic of the current Polish government, who he has accused of attacking the rule of law and democracy. In 2020, the NGO Freedom House downgraded its assessment of Polish democracy as ‘consolidated’ to ‘semiconsolidated’. In the fve years since the Law and Justice Party (PiS) came to power in 2015, they have used their control over the formerly independent body responsible for appointing judges to promote party loyalists to the newly created Disciplinary Chamber. Polish judges and international observers feared that the chamber would put pressure on the judiciary to issue rulings which fall in line with the government’s wishes.

The problem is that we’re only learning democracy, we’ve never had it before,” he says. He sees the situation as so dire that he has claimed a ‘dictatorship’ is being created in Poland. “In Poland, we are less than 50% of a

practical democracy,” he says, according to the ‘Wałęsa Model of Practical Democracy’, which he uses to break the system down into three practical areas. Poland scores full marks for its constitution and legal system, but voter turnout in elections is low, and Wałęsa doesn’t think many people are willing to stand up for change. Poland’s political troubles extend beyond the country’s borders and into Europe. Along with Hungary and Viktor Orbán’s Fidesz Party, the PiS frequently clashes with Brussels over the bloc’s promotion of progressive values and attempts to encourage the rule of law. Wałęsa has said that Poland should be thrown out of the EU over the PiS’s advances on the judiciary. But he also opposes ‘Polexit’, and speaks at Pro-European demonstrations alongside Donald Tusk, the former President of the European Council, who was an active member of Solidarity’s Youth Committee. “I’ve been saying this for twenty years: every vehicle must have a “Practicality, to Wałęsa, emphasises action and driver. The fght against Communism was a Polish matter which involved Polish people. Once that learning from one’s battle was won, we came to the challenge of trying to rebuild Europe. I passed this challenge mistakes for the future.” on to the Germans. “I would like it if Poland was the driver. But Poland doesn’t have the resources or infuence. Germany does. Together with France and Italy, they have the ability to enact changes and fnd two solutions for each problem.” But implementing solutions in the EU requires consensus between member states. Poland and Hungary recently vetoed the bloc’s COVID-19 recovery plan and €1.8 trillion seven-year budget because of plans to link a member state’s access to funds to their adherence to the rule of law. “If we can’t do it with Poland and Hungary in the camp, let them destroy the European Union,” he says bluntly. “And fve minutes later, we’ll propose a new one.” In order to access the rights and opportunities presented by this new union, prospective members would have to agree to a fresh series of obligations. “We have to establish these rights and obligations in such a way that this nonsense we see couldn’t possibly happen.” Wałęsa now travels the world promoting Poland’s non-violent transition to democracy, speaking about human rights and the challenges and opportunities posed by the Epoch of Discussion he told me about. He has a Wikipedia page dedicated to the many awards, state decorations, and honorary degrees he has received from across the world. Wałęsa never studied beyond his vocational training as an electrician, which he tells me he regrets. “Had I been a student, I would have ten Nobel Prizes, not just one!” In the model of many US Presidents, Wałęsa founded a eponymous institute to preserve the memory of the Solidarity movement and its place in history, and to educate future generations. I end by asking him what message he would give if he was speaking to an audience of students at Oxford. “My generation opened up opportunities for your generation. The world is yours. My generation has broken down a lot of barriers. Now you have to make the best of it, without these barriers and borders. It’s up to you to decide whether my generation has succeeded or not. Because if you fail, you’ll blame us. “Previous generations were scarred by wars and revolutions. Nobody trusted anyone. It’s up to you to convince people and open up your minds to other people. Because right now, the populists have taken over the initiative and everyone is sitting around and watching.”

“We realised if we all came together in solidarity we could achieve success.” “The populists have taken over the initiative and everyone is sitting around and watching.” With thanks to Anthony Goltz and Roman Picheta. Image Credit: Jindřich Nosek / CC BY-SA 4.0

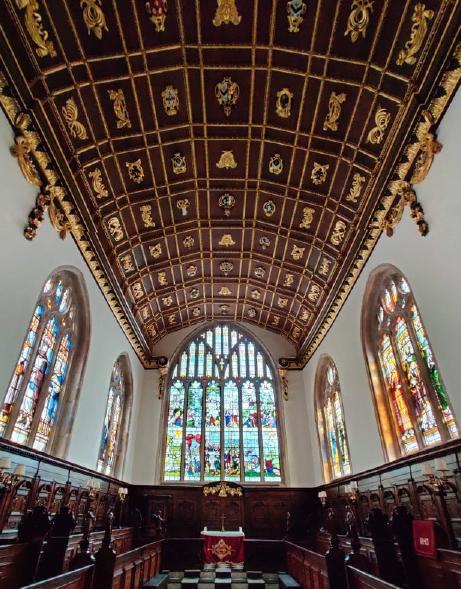

What’s going on in the chapel?

Alice Main (she/her) on her role as a Chapel Warden at Lincoln College.

When coming up with an idea for a column, I found myself thinking of my college chapel. I am a chapel warden at Lincoln College chapel which is very important to me, so I thought it might be nice to share some of the things we get up to and explain some of the more confusing things that go on in college chapels. Before we begin, it might be good to start with a little note about some of the language that can be used to describe what happens in chapels, as things can get a bit confusing. Denomination is a term used to describe which branch of Christianity a chapel is part of, and these different branches may infuence the different services offered or styles of worship (Lincoln chapel is Church of England, for reference). Incidentally, you of the Eucharistic prayer. I fnd this all slightly nerve wracking due to the fact that the water and wine are kept in very delicate (and I assume very expensive) glass bottles, and the chapel foor is marble which of course is a recipe for disaster if you arent paying attention to what you are doing. Weekday communion services usually take place at lunchtimes or in the evening, so they are a good option if you would like to take communion during the week. I would tend to go to an evening service because I can combine it with a formal dinner (also our chapel is gorgeous at night!). However, these tend to be quieter services, so if you prefer something slightly more social then a Sunday service or evensong might be nicer for you.

Sunday service

The stereotypical church service! This is nearly identical to the weekday Eucharist, but there will probably be slightly more people (so you may not be picked on to do a reading!) The highlight for some is probably the ‘breakfast’ afterwards, which in Lincoln consists of various pastries and pieces of fruit with a lot of coffee and tea. If you have had a bit of a rough week I would recommend this, as its a good opportunity to have a nice chat with friends. However, you do have to be wary of ‘Serious Theological Discussion’ which can be slightly intense but please don’t be put off by it as we usually get back to just general chatting. Evensong The big one. If you want to get the full Oxford Chapel Experience, go to an Evensong at least once. At Lincoln, this service consists of readings, organ recitals, the choir singing and often a visiting preacher to do the sermon. I would advise turning up slightly early to get a good seat and staying for drinks afterwards, which is a good way of either asking the visiting preacher any questions you may have or meeting up with friends before formal (my main bit of advice would be to get to the drinks before the choir do!) One of my more memorable evensongs (technically lessons and carols, please forgive me.) is when I got stuck in the anti-chapel with a small child, my tutor and a large bottle of red wine that had smashed all over the foor. It’s safe to say that it’s never dull in Lincoln chapel!

Whilst this isn’t an exhaustive list of all the things that go on in college chapels (I haven’t even mentioned the book clubs or other events run by the chaplains!), it will hopefully be useful if you are slightly confused about what goes on. As this column series continues, I will go through some of the people you may meet in a college chapel and take you on a little tour of some of the notable chapels in Oxford. I look forward to having you along with me and I hope we have fun! Image Credit: Matthew Foster

Questioning Otherness

Jacob Grech (he/him) on how migration is inspiring new visions of Europe.

The late Franco Battiato was one of Italy’s greatest, but also most improbable, music stars. After decades experimenting with avant-garde styles, Battiato achieved major commercial success in the 1980s with albums that offered a unique interpretation of the cantautore (singer-songwriter) tradition, crafting lyrics rich in esoteric, philosophical and religious imagery.

His best-known song, 1981’s dance foor hit Centro di gravità permanente, begins with a reference to Matteo Ricci, a 16th-century Jesuit scholar who travelled to the court of the Ming dynasty emperors. In Voglio vederti danzare, he sings about dervishes, hinting at his interest in Sufsm.

Battiato went on to participate, together with fellow artist Alice, in the Eurovision Song Contest as an established musician - may also hear terms like ‘high church’ or ‘low church’ being used to describe churches- this sounds very odd, but it’s just a way of indicating how much ritual is involved in a church service. I would probably describe Lincoln as a mixture of ‘high’ and ‘low’, which will make slightly more sense when I begin to walk you through a mini calender of the services in our chapel.

Morning Prayer Seeing as this is the frst service of the day, Morning Prayer seems like a good place to start. If you aren’t a morning person, I’m not sure this would be the service for you as you do need to be up a bit early. I fnd that combining it with a college breakfast in the company of the other wardens (much nicer than soggy cereal by yourself!), gives me the incentive to get up on time. Our Morning Prayers are fairly simple and last no longer than 20 minutes so you could describe this as our most ‘low church’ service. One thing that I think makes Lincoln slightly unique is that our Morning Prayers are sung, which in most circumstances is a lovely way to start the day. However, when you are full of freshers fu and mid essay crisis it might be a better idea to go back to sleep for a bit (take it from me, week 4 of Michaelmas was something I would rather not revisit). If you like simple and quick worship, then Morning Prayer is for you- just remember to wear a jumper, because chapels are very cold in the morning!

Weekday Eucharist For those who haven’t encountered the term Eucharist before, please don’t run away; this column isn’t about to become a theology lesson! Eucharist is another term for Holy Communion, where worshippers are offered the blood and body of Jesus in the form of bread and wine. One of our jobs as chapel wardens is to assist the chaplain during Eucharist, which is mainly carrying things to and from the alter and ringing a little bell in the important bits

mainstream, but uncomfortably so. Although Eurovision is intended as a celebration of a shared Europeanness, it is also associated in the minds of many with musical reenactments of long-running conficts between countries.

Battiato’s entry, I treni di Tozeur, does something quite different. It invokes the landscape and history of another continent altogether. Tozeur is a town in southwestern Tunisia, and the frontier referenced in the lyrics is the nearby Saharan border with Algeria. Although the song goes on to reference interstellar voyages and spaceships, setting a Eurovision entry in part on a North African railway seems more than whimsical or eccentric, although Battiato’s music celebrates both these qualities.

In all three songs I’ve mentioned, Battiato toys with the frontiers between the orient and the occident, but in so doing, questions how ‘natural’ they are. Beyond a fascination with their cultures, there is in his music a certain identifcation with people frequently labelled as ‘other’ than European.

North Africa has had a particularly complicated relationship with Europeanness – from the insistence that Algeria was as French as Paris, to the many thousands of Italians, French, Spanish and Maltese who settled across the region in the nineteenth century. This history remains a painful one to address. Subtler infuences, such as the role of Islamic philosophers like Ibn Sīnā in translating, interpreting and preserving Greek and Roman texts over the Middle Ages, are seldom acknowledged.

One element has not changed: for the purposes of defence, Europe extends far into North Africa. In recent years, this has meant strengthening barriers against migrants; the Central Mediterranean route is increasingly the main concern. With the deal between the Turkish government and Brussels to hinder migrants from making the perilous journey across the Aegean or EU-Turkey land border, it is from Libya and Tunisia that migrants increasingly depart. This is a dramatic reversal from 2015, when nearly 900,000 made use of the eastern route, in comparison to just over 150,000 in the Central Mediterranean.

Over 650,000 refugees, primarily from SubSaharan Africa and the Middle East, arrived in Sicily alone in the last decade. The ability of parties like Matteo Salvini’s Lega (formerly a party that advocated for the secession of Italy’s north) to make gains across Southern Italy indicates in part the power of hostility to migration.

However, there are important counter currents. Consider the NGOs maintaining search-andrescue vessels. National governments, when they do not refuse outright to accept these ships into their ports, frequently delay and leave vulnerable people in limbo. COVID-19 has only made this more common - Maltese authorities, for instance, frst closed their ports altogether and have continued to argue that they can offer no “safe place” because of domestic infection rates - and, being on the frontline, are “full up”.

Frequently, those who have stepped in are leaders at the local level – mayors and the coalitions of citizens they are able to rally. Palermo’s mayor, Leoluca Orlando, frequently defed Salvini when he was interior minister to admit rescue vessels and has campaigned to abolish the residence permit that restricts the mobility and employment possibilities of many arrivals. The former mayor of Riace, a small town in Calabria, Domenico Lucano, revitalised his declining community by assigning empty properties to refugees – frst Kurdish refugees in the late 1990s and later people from dozens of countries.

Besides humanitarianism, what drives these projects is frequently a recognition of the perennial multiculturalism of their own homelands. Migrants can be a source of renewal, a springboard for critical thinking. As Orlando puts it, they “helped us question that idea of state, as Europe’s constituent fathers began to after the war”, not least because they provide an opportunity to reassert an identity that goes beyond current political borders – a cosmopolitan Mediterranean identity.

This means reinterpreting Palermo’s Arab history, which lives on in its geography and Moorish architecture, and asserting the city’s connections to Istanbul and Beirut as much as Paris or Berlin. This is a call for a cultural reimagining – a long-term project to alter people’s relationships with their past and, it is hoped, the demographic changes of their present. In often surprising ways, this is already happening, with migrants themselves in the lead.

But the outlook remains bleak – fortress Europe is institutionalised and deeply popular. Mayor Lucano was sentenced last year to thirteen years in prison for “aiding and abetting illegal immigration”. Among his offences, assigning garbage collection contracts to migrants’ cooperatives and helping a Nigerian mother gain a residency permit through marriage. Throughout much of Europe, activists operating in a similar spirit of internationalism face harassment and regular clampdowns from authorities, not to mention abuse fuelled in part by legacy media.

It seems a truism to say that the arrival of migrants causes those already living somewhere to contemplate, however briefy, their own identity. The typical response is defensive; ‘the other’ can only dilute and threaten cultures understood as monoliths. But perhaps it can also be genuinely inquisitive and creative, causing people to question who they were, and who they might be.