6 minute read

Editor’s Corner Interview with Michael Crick

from 0th Week Hilary 2022

by Cherwell

Advertisement

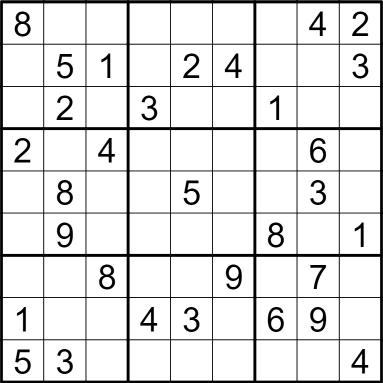

Adjacent digits along the red lines must have a difference of at least 5.

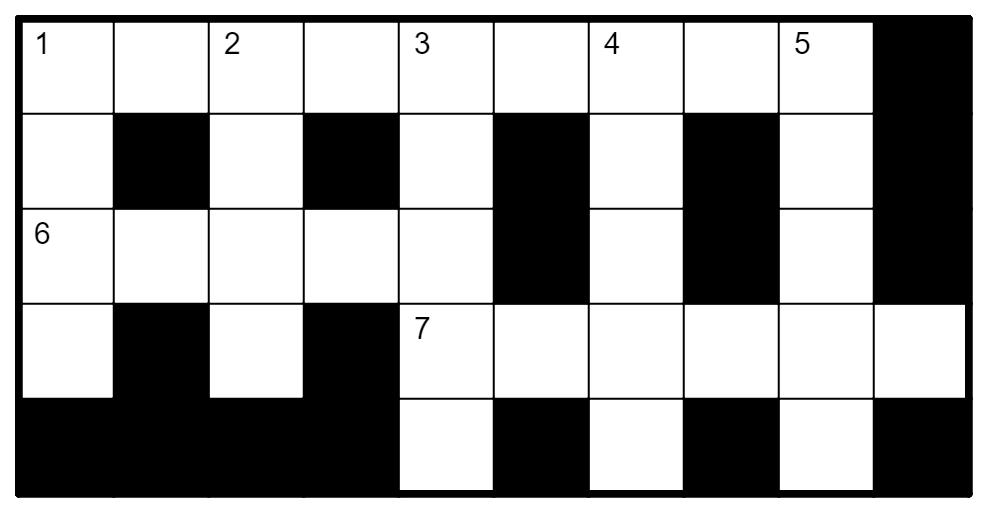

Across:

1. Used organ recklessly – not safe! (9) 6. Top of house hides back in complicit tabloid (5) 7. Student passes driving test, now gets paid (6)

Down:

1. Lottery ends in a stalemate (4) 2. Wrong tone for F (4) 3. Become profcient at spreadsheets (5) 4. Mash old pear for show (5) 5. Head of St. John’s makes even odd (5)

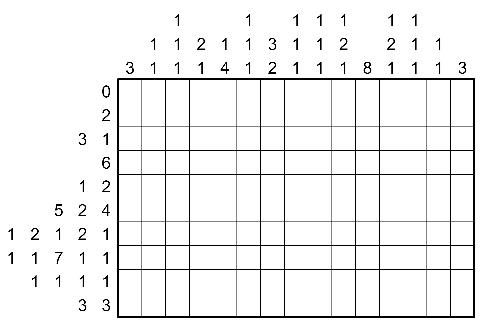

Pencil Puzzle - Hanjie

Hanjie comes from an old Japanese word meaning ‘judge picture’. It is also known as Nonogram, Oekaki-logic and other names. It was frst created by Non Ishida, a Japanese graphics editor whose work on using skyscraper lights in 1987 led her to create the puzzle and called it ‘Window Art’. Japanese puzzler Tetsuya Nishio also independently created the puzzle at around the same time.

The numbers at the start of rows and columns tell the number of squares shaded in along it. For example, a clue of “4 1 6” would mean there are sets of 4, 1 and 6 black squares, in that order, with at least one white square between each set.

Send your solutions to puzzlescherwell@gmail.com

Editor’s Corner: Michael Crick

Michael Crick was Editor of Cherwell in Michaelmas Term 1977. He went on to become one of England’s leading political journalists, was a founding member of the Channel 4 News Team and has worked extensively with the BBC.

How would you describe your experience working at Cherwell? Exhilarating and exhausting. A dress rehearsal for life.

What is your best memory from your time at Cherwell? The layout sessions in the cramped offce behind the Union which lasted from about 6pm on Wednesday night to about 6am the following day. Then, next morning, I often went on the trip by car to the printer, Roger Goodhead, in Bristol, where we would reward our all-night efforts with a huge cooked breakfast in the greasy spoon cafe next door while the papers were being printed off.

In those days, we had no computers and had to lay out the pages ourselves by pasting typeset columns of copy onto a layout board for each page. We had to construct the headlines by rubbing letters onto the layout boards from transfers printed on plastic sheets known as Lettraset - a delicate, time-consuming process, and often the letters cracked. I wasn’t a very good editor but I saw myself as the master of Lettrasetting.

What is the biggest lesson you learnt during your time as editor? Check your facts. I think it was actually the term after I was editor, on one of the trips to Bristol, that half-way through the paper being printed, a colleague rang from Oxford to say that the fag on All Souls College was at half-mast, and when he’d asked why at the All Souls lodge, the porter told him it was because the University Chancellor, the former Prime Minister Harold Macmillan, had died. I felt so pleased when we managed to squeeze ‘MACMILLAN DEAD’ into the Cherwell Stop Press. Only it wasn’t true. All Souls - and thereby me and Cherwell - had been the victim of a student hoax, and Macmillan would live for another ten years. Still, I’m probably the only journalist ever to kill off a Prime Minister. Remarkably, even though Macmillan was Chancellor of the University, there were no repercussions. Crick had failed to make the most elementary of checks. Mind you, a national newspaper - the Telegraph, I think - fell for the hoax too!

Would you have done anything differently as editor? I would have concentrated a lot more on producing serious, fresh journalism which was likely to make an impact beyond Oxford. So much of our energy and time in those days was taken up with other aspects of the venture - the business side, the layout, and terrible factional battles. The journalism was almost an after-thought at times.

Did your experience at Cherwell help you in your career? Undoubtedly, though I’d previously been involved in a fortnightly paper, The Mancunian, at my school, Manchester Grammar, and several Cherwell editors - including Howard Davies, Haig Gordon, Martin Sixsmith & Mike Thompson - had previously edited The Mancunian.

Perhaps the bigger infuence on me was that I was also business manager of Cherwell a couple of terms before I was editor, which probably gave me even more valuable experience than editing the paper. The challenge was to raise £300 in advertising revenue every week, which involved a lot of trudging round Oxford shop by shop. The two roles of being business manager and editor led to me founding a couple of OUSU publications, the Oxford Handbook and the Oxbridge Careers Handbook, which both lasted 30+ years, and raised huge sums for both Cherwell and OUSU over that time. My personal ambition was that eventually Cherwell should be a daily paper, like the Harvard Crimson, but I was in a minority of one on that, and it never happened, of course.

I also set up my own short-lived publishing business in my fnal year at Oxford which lasted for 2-3 years. I became quite entrepreneurial at Oxford, and this was an important feature of my reformist campaign when I twice ran for Union president in 1979 (the second time successfully). I sometimes wish I’d gone into business rather than journalism.

What was the biggest story you published? The then Union president and future deputy PM Damian Green being thrown dangerously into the Cherwell river by a bunch of drunken rugby club louts from Magdalen, while the future Attorney General Dominic Grieve looked on. The story was revisited by the national press a few times in recent years.

How did Cherwell change throughout your time on staff? I introduced a new feature - the Pushy Fresher contest - which lasted for at least ten years, and future winners included the socialite fraudster (and Boris Johnson chum) Darius Guppy, and also Nick Robinson (about which I occasionally tease him), while Jacob Rees-Mogg was also nominated for the dubious honour. Two years after I was editor, in 1979, when I was President of the Union, I anonymously wrote the Pushy Fresher column, assessing the nominations week by week, only to be exposed in the fnal issue by that term’s editor who, without warning me, thought it only fair that I be credited for my work. This led to me being accused of trying to infuence the Union elections - in alleged breach of the Union’s then absurd and draconian election rules. To avoid conviction by the Union election tribunal - and possible expulsion from the presidency with only a few days to go - I disappeared to Cambridge and lay low.

How have you seen the paper evolve since? Cherwell has changed hugely since 1977. We only had enough advertising income for about 8 pages a week, which is tiny compared with the current 40 or so. The modern Cherwell breaks a lot more stories - I notice it makes great use of Freedom of information. And it’s a lot more serious, but it can also be be dull at times, and be far too earnest, and lack a sense of fun. Computers have also transformed production, and eliminated the need for professional typesetting. Cherwell also seems to have several co-editors at once, whereas in those days it was almost always one overall editor per term. None of this “collective” nonsense - I was frmly in charge and the buck stopped with me, though I admit I was a pretty poor editor overall. But it was one of the formative experiences of my life. Wonderful, heady days. I only wish I had a few more pictures from that time.