25 minute read

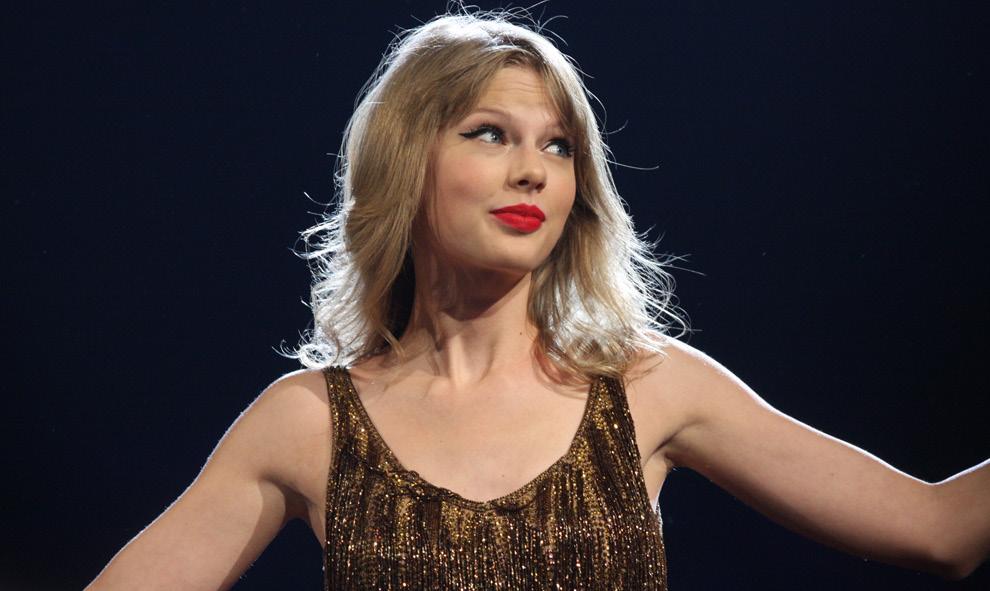

On misunderstanding Taylor Swift

from MT2 Cherwell Week 7

by Cherwell

True innovation in literature is hard to achieve — the same is true of music. But we can still see the value in certain stories and works. If we were to begin applying different metrics to music, we might be able to see a new value in what we listen to today. Looking at the ancient Greek literature of Homer from c. 800 BC and Taylor Swift can change the way you think about musicians today.

The poems of the earliest Greek poets, such as Homer, were not original in content; they were innovative in the way they drew together multiple different sources. When we consider that all stories can arguably be boiled down to seven basic plots, it is not hard to imagine why even the Greek poets struggled to come up with something new. This is demonstrated by Homer’s Iliad, one of the oldest Greek poems that we have today. The story of Achilles would have been familiar to Homer’s audience, who would have been acquainted with the broader narrative context of the Trojan Cycle, a key theme in the songs of many contemporary poets.

Advertisement

One of the central aspects of Homer’s Iliad is the grief of Achilles over the death of his loved one, Patroclus. This is borrowed from the Akkadian Epic of Gilgamesh (a twelfth century BC text from Ancient Iraq) – the titular hero suffers great anguish at the death of Enkidu, his loved one. Thematically, even Homer’s considerations such as tragedy of mortality set against the backdrop of immortal gods are borrowed from Gilgamesh. In a longer piece, further extensive correspondences could be highlighted (and caveats included), including those found in other ancient Greek texts. None of this diminishes the value in reading the Iliad, but it is worth noting that Homer is leaning heavily on precedent texts.

The way these poems have been constructed constitutes a large part of what makes them so impressive. Looking particularly at the Iliad, we see the central framework of the story: there is a tripartite structure, with Books 1-9 constituting the setup of Achilles’ wrath, Books 10-16 being the consequence of Achilles’ continued wrath, and Books 17-24 constituting Achilles’ return to battle and the ramifcations. This is the basic core of the poem.

The text is then overlaid with ring composition to bind the whole poem together and underlined with sub-narratives of anger to refect the overall plot of the poem. Another distinctive structural feature is how pairs and triplets of events build into each other, such as the deaths of Sarpedon, Patroclus, and Hector all making the next one more intense, each with an emotional setup, buildup, and climax. Most of these events ft into three categories: either stock stories like the ‘anger cycle’ taken from Homer’s tradition, real events including the death of Hector lifted from their shared tradition, or parallels to earlier traditions, such as the Gilgamesh. These infuences were distilled into a framework handed down to Homer, and the bard was able to process it all into a fnely woven composition.

Again, this is not to deny the value in analysing the themes that occur in the poem, nor to suggest that it is not a joy to read for its indepth characterisation, engrossing descriptions, and exciting passages of narrative. Instead, I am merely trying to highlight another metric by which to analyse the poems: intricacy of composition.

Innovation in music is also arguably diffcult: it suffers from the same narrative constraints as literature, and there are limitations imposed by the sonic form. For instance, across a set of parameters, every melody has been produced by a computer and copyrighted, while there are only 243 combinations of 3 notes by 5 notes, demonstrating that there is a limit to the potential of sonic innovation. Admittedly, we may be far from this ceiling, but I think that the existence of limits should prompt us to consider new ways to analyse song writing. One way could be the same as epic literature, exploring the way musical precedent is used to weave intricate and complex compositions.

A quick example of this is the use of sampling: often, musicians take other musicians’ work and incorporate the sounds into the fabric of their own song to great effect – consider Kanye West’s sampling of Daft Punk’s ‘Harder Better Faster Stronger’; and ‘Harder Better Faster Stronger’ sampling Edwin Birdsong’s ‘Cola Bottle Baby’. In all these cases, musicians have been able to take songs from completely different genres and work them into their own compositions. Similarly, the ancient poet Hesiod included didactic literature, apocalyptic prophecies, and catalogue poetry in his Works and Days. But this should not be viewed as negative: instead, artists have and continue to draw on different genres to produce masterful works.

Just as certain sounds recur, certain themes are repeated in song writing. There are an incredibly large number of songs about heartbreak revolving around themes of affairs, falling out of love, and lovers being taken too soon. World Peace seems to be a popular subject too, just consider ‘Imagine’, ‘Give Me Love’, ‘Heal the World’, ‘We are here’ and the like.

Sometimes, motifs are also shared between songs, including singing from the perspective of the devil.

Khusrau Islam examines the history of literary innovation, from Homer to Taylor.

This is common to the rock genre, demonstrated in ‘Devil’s Child’ (Judas Priest), ‘Friend of the Devil’ (Grateful Dead), and, of course, ‘Sympathy for the Devil’ (The Rolling Stones). While these examples are inexhaustive, they should demonstrate how, in thematic terms, songs tend not to innovate but rather build upon motifs and tropes with a broder universal appeal to produce something intricate and unique, much like the incorporation of other sounds through sampling. ‘Devil’s Child’, for example, uses the Devil motif in combination with those of heartbreak – thus drawing on different genres, motifs, and traditions. Instead of focussing on the artistic talent of innovation and creativity, we should focus on the composition, like we do for the Iliad.

Taylor Swift’s music is indicative of this sort of composition. She has been lambasted for the use of repetitive motifs and themes, particularly those surrounding heartbreak. However,her work is highly versatile, if not on thematic terms then in composition. ‘Look What You Made Me Do’ (LWYMMD) highlights Taylor’s ability to use structure, contemporary events, and narrative to create complex musical pieces. She has successfully performed the transition from the country genre through to pop, gaining mastery over the latter genre’s song structure. She has consistently incorporated different ideas and infuences into her music, even as she shifts again into the alternative genre. This is where we can see artistic value: the composition of her music is intricate and complex.

‘LWYMMD’ is a useful starting point to highlight Swift’s understanding of different motifs, and how she uses them to derive meaning. Classic FM analysed ‘LWYMMD’ from a music theory standpoint, and came to the conclusion that the song consistently leads the listener’s expectations in ascertain direction before failing to satisfy these expectations. After hearing this lead single, pundits from news outlet NPR predicted Taylor would play the victim on the rest of ‘Reputation’. Upon the release, it became clear the album is not a bitter collection of vitriolic songs, but actually mostly explores her feelings in a new relationship. Throughout ‘Reputation’, Taylor points to what she could have done – a grand chorus, or a bitter revenge album – but instead takes it in a different direction. In the opening section of the Odyssey, Zeus discusses justice and revenge, leading the audience to expect a story centred around these themes. However, Homer instead goes in a different direction: he has hinted at what he could explore but instead proceeds to write about different subject matter. In the same way, ‘LWYMMD’ points to certain themes and techniques that she could have chosen to use, the rest of the album is almost completely different.

The weaving of different themes and qualities into her music is best seen in her transition through to pop. By the publishing of ‘1989’ in 2014, Taylor had dropped her country accent almost completely, increasingly conforming to the standards of pop in spite of criticism. However, she has not dropped her country roots. Firstly, she still sings of troubles specifc to her, a motif common to country music and has also borrowed tropes such as escaping the small town. As she progresses to pop, Taylor keeps hold of the emotional energy of country, with all its personal power.

When she does reach pop music, she exerts an extreme amount of control and mastery over commonly used sonic structures. ‘Blank Space’ parodies both the narratives surrounding her and general pop structures. This is done by the marking out of the chorus and the excessive use of four chords that are commonly used throughout music. The basic structure of a song is tripartite: setup, build-up, and climax, often corresponding to the sections verse-chorus, verse-chorus, bridge-chorus. ‘Shake It Off’, as basic as it may seem, is one of the most complex songs on the album ‘1989’. This is because each sub-setup, build-up, and climax have their own setup, build-up, and climax. We praise Homer for his ability to expand on his basic structural frameworks: to appreciate the artistry of the compositions, we should look at Taylor’s songs in the same way. Her use of the bridge is a good example of structural frameworks being adapted to great effect. Though others might be regarded as the “classic” Taylor Swift bridges, such as ‘Death by a Thousand Cuts’ and ‘All too Well’, the bridge in Illicit Affairs (IA) is demonstrative of this. The song discusses an affair from the perspective of “the other woman”. Throughout, Swift addresses how affair partners are forced to hide their trysts, resulting in the need to deny the feelings they have. This is echoed in the bridge where she writes about how she was shown “colours you know I can’t see with anyone else” and taught “a secret language I can’t speak with anyone else” – there is nothing she can do about her feelings. She disrupts the ordinary song structure by having the bridge fade into the outro, and not another chorus. Here, the bridge leads nowhere, just like an illicit affair, in which you must deny all your true feelings and hide it from everyone you know, cannot lead anywhere. Through her song structure, Swift supports the narrative thesis of the song.

Another example is the use of set phrases to convey meaning. Homer does this to an extent: while his use of epithets is often dictated by metrical constraints, it can sometimes derive meaning. This happens in Iliad Book 22, where the phrase “swift-footed Achilles” is used to foreshadow Achilles’ eventual catching of Hector, enabled by his speed. The use of the phrase foreshadows the eventual event.

This use of phrases to derive specifc meaning can also be seen in Swift’s music. For example, in ‘Hey Stephen’, she sings the line ‘I can’t help it if you look like an angel / can’t help it if I wanna kiss you in the rain’: on a surface level it is easy to see how the use of angel imagery evokes a positive impression of love. On ‘White Horse’, she sings, ‘Say you’re sorry, that face of an angel / comes out just when you need It to’: on the next track of the album, the angel imagery has been twisted to produce opposite feelings of heartbreak. The way of using this image is not new – consider the angel motif in ‘You Give Love a Bad Name’ – but just because the motif is repeated or inherited does not reduce its value: the use of the phrase gives meaning within the song. Just as Homer adapts stock imagery to his needs, here Swift uses a common motif in multiple ways to offer value.

Swift is also able to draw on a wealth of ideas and infuences, further highlighting her artistic talent. It is certainly true that in the past she was considered to have written solely about love, or ‘silly’ themes like teenage heartbreak, but enough people, even national newspapers like the Washington Post, have acknowledged the versatility in her themes. A few examples of this versatility include social anxiety in ‘Mirrorball’, dealing with her mother’s illness in ‘Soon You’ll Get Better’, her love for her late grandmother in ‘Marjorie’, or discussing teenage love from different perspectives in two consecutive singles, ‘White Horse’ and ‘Love Story’. With over 150 songs in her discography, it would be surprising if she had not written lyrics across a broad spectrum of themes.

However, it is worth noting how she draws different ideas and themes into the makeup of her songs, such as in Cardigan. Here, she explores affairs (“chase two girls, lose the one”), growing up (“when you are young, they assume you know nothing”), and heartbreak (“chasin’ shadows in the grocery line”). The imagery combines fairy tales (“Peter losing Wendy”), fashion (“high heels on cobblestones”, etc.), and broken families (“leaving like a father”). These are very brief examples that highlight the way in which Swift has returned to the realm of high school love triangles to give a much more nuanced perspective. At this point, rather than simply providing an indepth exploration of one theme, or a completely innovative narrative, she layers in all manners of imagery to craft a refection on cheated on

“One way could be the same as epic whilst young. With examples like ‘IA’, ‘LWYMliterature, exploring the way musical MD’, and ‘Cardigan’ in particular, I hope to have shown how value precedent is used to weave intricate and meaning can be derived from the way the songs are composed. and complex compositions.” There are many other features of her music I could have explored, such as the sampling of ‘I’m Too Sexy’ in LWYMMD or of her own heartbeat in Wildest Dreams. However, this past section has aimed to show there is an inherent artistry behind Taylor Swift’s songs in the way different themes and structures have been layered into what we hear. I believe this analysis could be fruitful for music in general. True innovation is possible, but it becomes increasingly diffcult and rare to fnd. Instead, we can derive value from the way music is composed. Of course, a song could be the most impressively intricate and complex song ever created, and people would not be obliged to enjoy it. This exploration is not a demand for people to start enjoying music on these grounds. Certainly, I listen to Taylor Swift almost solely because I enjoy listening to the sounds and lyrics of her music. However, I believe this sort of analysis could lead to a new appreciation of different songs. The poems of Homer have value outside of their composition yet analysing the poet’s craft reveals “True innovation is possible, but it their true skill in writing. Similarly, by analysing becomes increasingly difficult and modern music on these terms, we might reach a rare to find.” new level of appreciation for modern artists. The poems of Homer have value outside of their composition yet analysing the craft behind them reveals the true skill of the bards composing these poems. Similarly, by analysing modern music on these terms, we might reach a new level of appreciation for modern artists. Image Credit (top-bottom): Eva Rinaldi/CC BY-SA 2.0; Pixabay.

CONTENTS

CULCHER

14 | Art as escapism 15 | Reshuffling our thoughts

THE SOURCE

16 | Omoroca, Leah Stein

MUSIC

18 | A night at the Sheldonian

FILM

19 | Back to school: Sex (re)education

BOOKS

20 | Books in translations

STAGE

21 | Review ‘Murder in Argos’

FASHION

22 | Hot off the runway: fashion soc returns to Oxford 23 | In conversation with Yasmin Jones-Henry

COVER ARTIST

The Pitt Rivers Museum

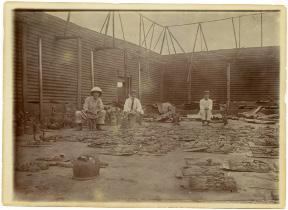

This week, Cherwell’s Culture section introduces an upcoming collaboration with the Pitt Rivers Museum to highlight the Benin bronzes and their legacy. Issues of labelling, return, and colonial violence are vital to contemporary debates on museums, and the erasing legacy that they both represent and contribute to.

Cherwell’s Culture editorial this week explains how the display of these artefacts is a manifestation of colonial violence, as well as highlighting the work of artist Leo Asemota on illuminating the power of these artefacts as representations and methods of interpretation.

The PRM has kindly contributed our cover photo, an interior of King’s compound burnt during fre in the siege of Benin City, with three British offcers of the Punitive Expedition [from left, Captain C.H.P. Carter 42nd, F.P. Hill, unknown], seated with bronzes laid out in foreground.

Accession # 1998.208.15.11 Photographer: Reginald Kerr Granville Date of Photo: 1897 Continent: Africa Geographical Area: West Africa Country: Nigeria Region/Place: Benin City Cultural Group: Edo [Benin] Named Person(s): Captain C. H. P. Carter, F. P. Hill Format: Print black & white Size: 165 x 115 mm Acquisition: Hugh Nevin Nevins ? - Donated?

Escape to the culture-side

Georgia Brown on the art in the pandemic, and the importance of escapism.

There is a certain magic in the escapism that art offers, in our ability as humans to completely fall into worlds and emotions that do not belong to us. Not to be underestimated as mindless distraction, there is something powerful in how art permits us to create a different reality to the one we fnd ourselves in.

Since the beginning of the pandemic, the question of how long art can exist as a form of escapism is something I have ruminated over quite a bit. As the world seemed to spin out of control in the frst lockdown, we cannot be blamed for seeking out alternate realities. Some people discovered new creative outlets, whilst others flled their days with consuming art, whether that be artworks, flms, books, music or TV shows. Our willingness to become lost in stories where words such as lockdown or pandemic had little meaning is unsurprising, and evident in trends from the time.

Take the Normal People phenomenon of April 2020. Without detracting from the show’s deserved success, arguably the twelve-hour intimate exploration of the protagonists’ relationship resonated so widely due to the audience’s desperation for, well, normality. The show’s emphasis on the signifcance of physicality and touch only played upon people’s longing for connection. It was a reminder of the lives and emotional ties that had been paused, a respite from our strange new surroundings.

This relief could only be offered for so long, however. It was inevitable that the new emotions and anxieties would seep into the art being produced. Yet interestingly, many early creations were met with mixed receptions. Love in the Time of Corona, a hasty pandemic project released in August 2020, was particularly attacked by critics. Critic Adrian Horton remained “sceptical that there’s anything that can capture a period we’re still very much in”, which confrms the suspicion that people still wished to suspend belief for a moment longer. It was, quite simply, too soon to see our newsfeeds replicated in the fction that we turned to for escape.

Yet, as we distance ourselves from the past two years, I would argue that there is value in seeing the world around us refected in the art we consume. In her book Funny

Weather: Art in an Emergency, Olivia Laing discusses how art certainly cannot solve everything. It cannot provide a concrete answer, nor can it explain fully what has happened. It can, however, be reparative for the future. It offers a new way of seeing, opens our eyes to the alternate possibilities surrounding us. The best art, in her opinion, is “more invested in fnding nourishment than identifying poison”. Whilst art may not allow us to change what has already happened, it can provide us with the hope of what follows.

I think, most importantly, art allows us to catch our breath. Whilst we are so desperate to rush towards getting back to normal, I will speak for myself in saying that I am not ready to move on just yet. As the days ahead stretch out and are flled with seeing friends and family, alongside gratitude, I can still feel the discombobulating nature of what we have experienced upon my shoulders. As if I am foating somewhere in the sphere of the new normal, not quite grounding my feet. Art allows us to sit in moments like these; it freezes time and gives emotions the space to be felt. It allows us to make better sense of ourselves. I would like to catch my breath. Whilst I agree that reminders of bleak lockdowns are not in demand, I would like to see art that refects the shift in our collective experience and channels our emotions. I would like to see art that discusses where we are right now, here, in the aftermath.

“As the world That offers a light for this messy in-between seemed to spin out stage where everything is yet to fall into place and lets us know that we are not alone. of control in the I hope we do begin to see stories of people first lockdown, we trying to scramble back into social interactions; university freshers who haven’t had cannot be blamed normality since they were sixteen, twentyfor seeking out somethings thrown into the adult world unexpectedly, people grieving for the time alternate realities.” that was lost. Stories of how love has been changed; people who fell into connections immediately, people who still can’t seem to shake the distance placed upon them. Tales that feature the pandemic of course, but at their heart are mostly just about people learning to live again. Escapism will always have its blissful moments, but there is also a kind of beauty in the strangeness around us. I hope we don’t turn away from it.

Reshuffling our thoughts

Flora Dyson on the concept of the album in the age of digital music.

Sunday saw a shock decision by Spotify, which has fundamentally shaped the concept of the album in the digital age. Adele’s new album, 30, can no longer be shuffled as the streaming giant followed the artist’s conviction for her musical material from ‘I Know There’s An Answer’ into ‘Hang On To Your Ego’ which provides reflective threads on the previous angst within the album’s narrative and compliments the contemporaneous technology it would be album to be heard as a cohesive, narrative whole. Whilst the loss of a small button may seem inconsequential to many, I believe it intrinsically alters our conceptualisa“Music listening is tion of the album in an increasingly disparate, modern now based upon its musical age. Arguably many of the 20th and 21st century’s finest albums act as a musical entity, rather than a collection reception rather than its artist of disparate songs. Adele’s 30 follows an explanatory intention.” narrative as she follows her divorce. The singer says her album, amongst others, “tells a story and our stories should be listened to as we intended.” Yet Adele is not the first to use her album to ex- press a narrative. Bruno Mars’ and Silk Sonic’s recent a l bum, An Even- ing With Silk Sonic, uses funk inspira- tion which is novel i n comparison to t h e poppy tone of the Mars’ oeuvre. The rest of funk-king Bootsy Collins announc- es the work in ‘Silk Sonic Intro’ which makes the album appear as if it is a recording of a live performance, conceptualised as a narrative whole and situated in time,.

The structure of An Evening With Silk Sonic and 30 hark back to a by-gone age of analogue listening. Music was heard on vinyl, with the needle cutting through tracks in the artist’s intended order. Connections across an album would be recognised by the attentive listener. The Beach Boys’ seminal work, Pet Sounds, transfers melodic played on as it would allow the listener to recognise a revision of material within the passage of time. Music- playing technol- ogy has funda - mentally changed our concept of the album and its narrative. Stream- ing allows us to drag-and-drop our preferred tracks into curatable playlists based on mood or the music’s association in a display of listener agency. Listenership has moved from passively appreciating an artist’s work to reforming it to fit our taste. It is almost as if the album has become a box of chocolates; we pick our favourites and discard the rest. However, the album is not a disposable commodity and is, in most cases, a piece of art with personal to its creator and cultural value to its listener. Do you read a chapter of a novel at random, only to put it down again, or select your favourite objects in a painting? Alas, I thought not. The album, like a painting or a book, should be considered as a whole work. Music-disseminating technology devalued the album to pander to listener preferences in a seismic shift of musical authority. Music listening is now based upon its reception rather than its artist intention. Artists release their albums into the public realm and express their innermost artistic creativity through such mediums. Surely we would be doing them a disservice to reorder and cherry-pick the fruits of their labours?

PITT RIVERS EDITORIAL

On the first floor of the Pitt Rivers Museum, in a corner framed by fire extinguishers is a display case entitled ‘Court Art of Benin’ which holds bronze plaques, sculptures etc., many of which were looted during the 1897 Punitive Expedition of the Kingdom of Benin, Nigeria. The proximity of the fire extinguishers makes all more apparent the scorch marks along the large and elaborately carved ivory tusk, most likely a scar from the military campaign itself, a reminder of the violence that facilitated the entrance of these objects into museums such as the PRM.

The debate surrounding the objects looted during the punitive expedition is not new, and has been front and centre in current talks of repatriation and restitution. The scorch marks and tears in the bronzes are not the only marks of violence and displacement in the display case, but the case label itself enacts a type of violence that is much less overt but perhaps more pervasive. As part the Labelling Matters project, the PRM undertook a review of their displays and interpretation. Employing euphemistic language, the Benin case labels effectively take control of narrative by turning it in favour of colonisers. It locates them at the heart of production of knowledge and grants them interpretative agency whilst at the same time silencing, erasing, and invalidating the ways of knowing and understanding of others; also known as epistemicide.

The current museum label’s narrative of ‘ambush and retaliation’ is built to obscure the severity of the crimes committed on the side of the British military, and the retaliation mission is presented as a proportional response to this assault, but what is left out is the actual violence, physical and cultural causalities. The label decidedly tells a story that is far more forgiving on the side of the British military. It rationalises and justifies lawless action by crafting a story of cause (ambush) and effect (retaliation).

Guided by the hope of beginning to further illuminate the issues of interpretation and ownership surrounding the Benin objects the PRM is collaborating with Nigerian artist Leo Asemota on a commission funded by the Art Fund. The overall collecting project was envisioned to collect contemporary objects that act simultaneously as artefacts and new forms of interpretation by speaking directly to the existing collection. The project with Asemota is an offshoot his Ens Project, which formative and creative impetus are ancient and contemporary Nigeria’s Edo peoples of Benin’s rich tradition of art and ceremony, Victorian Britain’s history of invention, exploration, and conquest in which the sacking and looting of the former Kingdom of Benin is of particular interest.

The collaboration with the PRM focuses on the epistemicide that occurs through the displacement and decontextualization of the objects that occurs within the museum’s display. Asemota seeks to provoke thought on this subject by mimicking that displacement by using the same media that was first used to disseminate information and images of the Punitive Expedition, the printed press. On 10 April 1897, the Illustrated London News published an article titled Spoils from Benin, which featured images of objects taken during the expedition accompanied by a dehumanising account of the Edo people. The PRM and Asemota are partnering with Cherwell in 2022, the 125th anniversary of the punitive expedition, to create a special edition of the newspaper. The special edition newspaper project seeks to create that jarring sense of decontextualization as a means to sparking more conversation and understanding around what truly occurs when cultural heritage is taken and withheld without consent.

With most Benin court objects stored behind glass cases in European countries the ritual life of these objects had forcefully been stopped. A valuable link was lost as these belongings used to serve as material anchors mediating between people environment and the sacred. The stillness surrounding the objects on display here is no serene silence, it is rather a discomforting quiet that speaks to a history of violence.