32 minute read

Yesterday’s City Henry Field’s Legendary Expeditions

Henry Field’s Legendary Expeditions

S. J. REDMAN

Advertisement

Henry Field (left) and Dimna, an excavation specialist, examine a four-wheeled chariot, two wheels of which are exposed, during the 1927–28 expedition. The oldest-known wheels for transport were discovered at Kish; two are in the Field Museum’s collection. M useums build their collections through a variety of ways. Some receive artifacts following the death of a private collector. Many purchase or collect objects in exchange with other institutions. None of these traditional methods of collecting, however, bring to mind the glamour and adventure of the classic museum expedition. Henry Field, who began his career at the Field Museum as assistant curator in 1926 and became curator of physical anthropology there from 1934 to 1941, lived for this sort of odyssey. The remnants of some of Field’s legendary expeditions now rest in the Chicago museum that bears his family name, on the shelves of a department of anthropology storeroom. This collection consists of nearly four thousand catalogued artifacts obtained during his North Arabian Desert Expeditions in 1927 and 1928.

Henry Field, the grand-nephew of department store giant Marshall Field, wanted to work in a museum from a very young age: “My first desire, after graduating from Oxford, was to work in a museum, and it had been my dream since childhood to return someday to Chicago. Both desire and dream were to be realized, for I received a position as assistant curator of physical anthropology at Field Museum of Natural History.” Marshall Field’s fortune and vast connections had helped found the Field

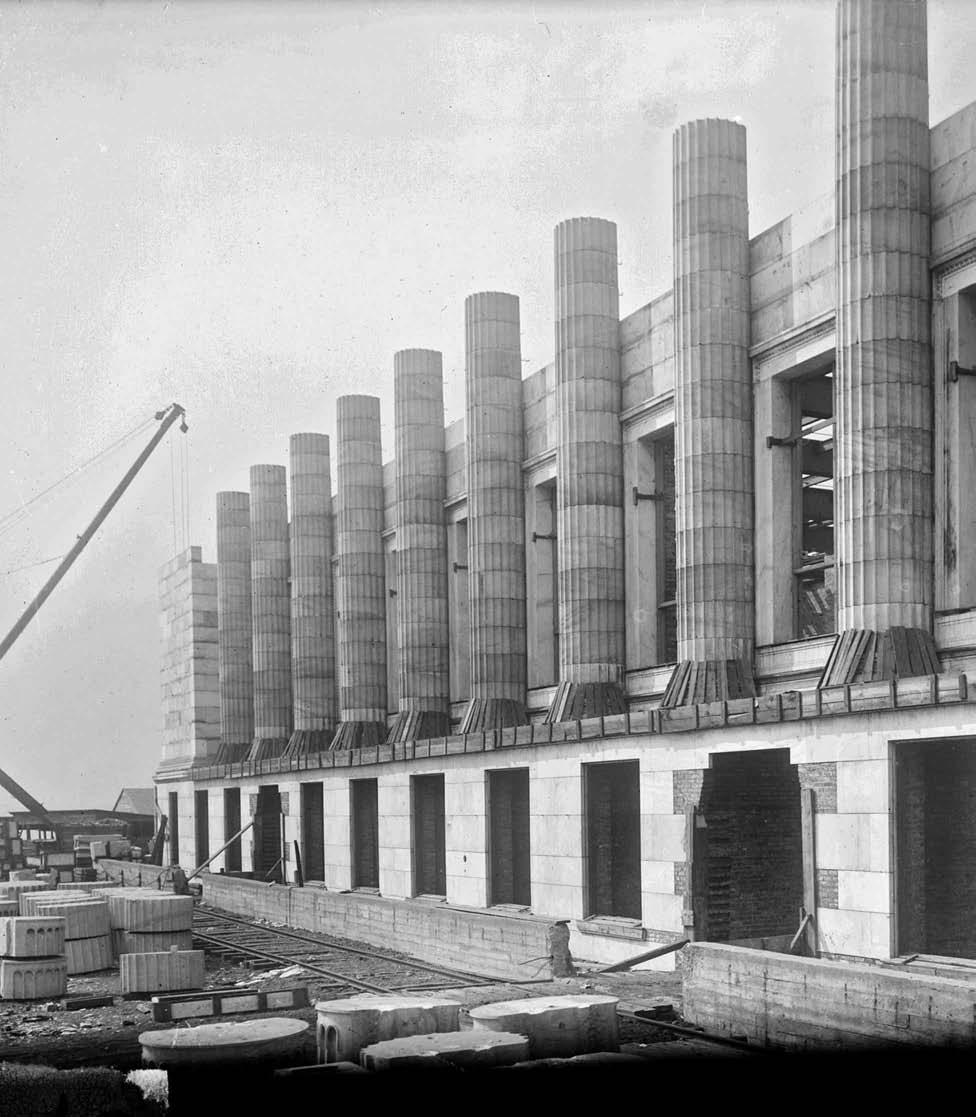

Above: The groundbreaking ceremony for the new Field Museum building in 1917 included members of the administration, curators, and other museum staff. The museum moved from its building in Jackson Park (now the site of the Museum of Science and Industry) to its current location in the Museum Campus on Lake Michigan (opposite).

Fredric Ward Putnam, chief anthropologist of the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893, (right) helped transform artifacts from the fair into exhibits for the new Field Columbian Museum. He worked at the museum until 1919. Columbian Museum—now the Field Museum of Natural History—in 1894. When the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893 drew to a close, Marshall Field’s first museum donation allowed a team of anthropologists, including Franz Boas and Fredric Ward Putnam, to secure objects exhibited at the world’s fair for the new museum. Boas and Putnam, with the help of one hundred assistants, had orchestrated a massive campaign to organize fair’s enormously successful Anthropology Building. After Marshall Field died in 1906, his will bequeathed millions of dollars to help fund the new Field Museum building that opened in 1921. Marshall’s nephew (and Henry’s cousin) Stanley Field ran the museum as its president and, later, board chairman for fifty-six years until his death in 1964.

While Henry Field possessed obvious connections to the Field Museum, he also had a genuine passion and dedication for the museum’s disciplines. While studying at Oxford and Heidelberg under L. H. Dudley Buxton, one of the world’s top anthropologists, archaeologists, and historians, he became interested not only in the study of physical anthropology, but also prehistoric and ancient history. In late 1925, before Field had completed his work at Oxford, his grand-uncle, Barbour Lathrop, gave him one thousand dollars to travel to the archaeological site of Kish in Iraq. The Field Museum had been participating in collaborative excavations with the Ashmolean Museum at Oxford and the Baghdad Museum since 1923. Field’s funds allowed him to invite Buxton to travel with him on the brief journey.

During the first excavations at Kish, Field routinely arranged side trips and day journeys, searching for evidence of prehistoric man in the region. Field and Buxton were escorted by the British Royal Air Force (RAF), who maintained several landing grounds in the region of the survey. The team, which included several RAF officers, often recorded the location of their finds based on the names of these landing grounds, such as “Landing Ground K” or “Landing Ground H.”

Stopping their armored vehicles periodically, the RAF would allow Field and Buxton to survey the desert ground for short periods of time, looking for pieces of flint worked by early man. Field noted that the process was rather unusual: “It still seemed strange to have been searching for prehistoric man in two Rolls-Royce armored cars mounted with machine guns.” Field dramatically described the first major discovery of the expedition:

Suddenly Buxton shouted, “Come here, I’ve found one.” I ran over to him, and sure enough he had picked up the first flint flake chipped by ancient man

Above: Stanley Field, Henry Field’s cousin, was president of the Field Museum, then chairman of the board, until 1964. Below: Field Museum employees inspect specimens, including crates filled with stuffed and mounted animals, acquired during a field expedition to Abyssinia (now Ethiopia).

L. H. Dudley Buxton, Henry Field’s primary mentor, greatly influenced his future field exhibition work. Here Buxton clears a skeleton during the Field Museum-Oxford University Kish expedition in 1925–26.

found in that part of the world. Up to this time no evidence of prehistoric man had been found east of the great lava bed we had passed; in fact the North Arabian

Desert was believed to have been a barrier to migration.

Conditions in the desert were less than perfect. The team ate canned food and suffered from lack of water and extreme temperatures. Members of the Royal Air Force warned the team that certain regions were too dangerous to set up overnight camps because of the constant threat of bandit attacks. The men took turns driving and sleeping in the vehicles, which bounced over the rough terrain. Field wrote: “We all looked dirty and our unshaven faces made us look more than a little like convicts. I glanced in the back again and wondered who could have recognized two distinguished Oxford dons.” He later noted: “Books and lectures seemed less appealing after our adventures in Iraq.”

Still, during his time at the Field Museum, Henry Field’s work clearly reflected his seemingly boundless enthusiasm. Soon after he started at the Field, he began preliminary work on two of the museum’s bestremembered exhibits that would open years later: the Hall of the Races of Mankind, later known as the Hall of Man, and the Hall of Prehistoric Man. The Hall of the Races of Mankind displayed sculptures of what were considered to be examples of various racial types. Following the anthropological thought of the time, Field believed that there were 164 types of peoples. In his early work, Field had attempted to utilize anthropometrics, or skeletal measurements, to articulate the differences between various peoples. Anthropologists now recognize many of these attempts as scientifically flawed and driven by racist agendas. While Field’s work does not appear to have been driven by these agendas, the work of many of his colleagues has been debunked, tarnishing the reputation of anthropometrics as a discipline.

In 1930, when anthropometrics was still regarded highly, the Field Museum commissioned sculptor Malvina Hoffman to travel around the world and create life-like bronzes for display. After Hoffman had circled the globe twice, her work resulted in twenty full-size bronze figures, twenty-seven busts, and one hundred “face masks”. The Hall of Races opened in time for Chicago’s world’s fair in 1933 and was an instant success. Field wrote in The Track of Man: “No one can see these bronzes and fail to be impressed by the innate dignity of man. . . . Each race has its own distinction and its own dignity.” The Field Museum still displays many of these sculptures.

Buxton (at left) and his car got stuck in the sand en route to Jemdet Nasr.

In addition to his expeditions, Henry Field worked on some of the museum’s best-known exhibitions, including the Hall of the Races of Mankind, featuring sculptures by Malvina Hoffman.

Still, despite his museum research, Field longed to continue his expedition work:

I had wanted to continue the desert hunt for Stone

Age man ever since Buxton had found the flint implements lying on the surface of the desert between Amman and Baghdad. They had left so many questions in my mind. . . . Often at night in

Chicago as the foghorn boomed across the lake, I had lain awake wondering and thinking.

Field turned to Field Museum chief curator Berthold Laufer, who “suggested . . . I should return to Kish for the winter to continue my North Arabian Desert archaeological survey, to record additional anthropometric work in Iraq, and to excavate all the skeletal material found that season at Kish. The triple assignment thrilled me.”

Field was able to reach Kish in time for the 1927–28 expedition season. He chose the location for the initial survey based on a “hunch”: “This seemed a possible location for the discovery of prehistoric implements because the wells were reputed to be very ancient, and there was a large wadi [gully] nearby.” Field’s use of pedestrian surveys, or simply walking over an area in an attempt to find evidence of occupation, while not an uncommon practice in archaeology, relied on a fair amount of luck.

On his way to Kish, Field again turned his attention to the evidence of the existence of prehistoric man in the region. Before passing through the city of Falluja, the team made what they believed to be additional significant discoveries, such as stone tools shaped like the letter “T”, as Field described:

Next day, north of Landing Ground “K,” I found many types of flint implements, including hammerstones, scrapers, knives, and hundreds of rejects and flakes. Suddenly I saw a T-shaped flint implement, a type brand new in this region, which showed an excellent flint-flaking technique. Within an hour we had a small series.

Working with the joint team at Kish, Field built a substantial collection of stone tools and a small library worth of anthropometric measurements and photographs for the Field Museum’s archives. The most spectacular finding of the expedition, however, was Field's discovery of a 5,000year-old chariot, long cited as the oldest existing wheeled vehicle. He also uncovered evidence of an inundation of the city of Kish in Mesopotamia, that he later said might have indicated evidence of Noah’s flood.

The Chicago Tribune announced Henry Field’s 1927 expedition to Europe and Asia and reported that he would search for “relics which will cast light upon the progress of prehistoric man from about 500,000 B.C. until the dawn of civilization.”

Above: Eric Schroeder and Henry Field clearing the skeletons of wild animals during the Field Museum-Oxford University 1927–28 Kish expedition.

Right: One of Field’s most exciting finds at Kish consisted of two ancient chariot wheels, which the Chicago Tribune reported was believed to have been part of a vehicle that a warrior rode into battle around 3000 B.C. The newspaper called the discovery “one of the most valuable in recent years.”

Once Field returned to Chicago, he turned much of his attention to proving the significance of the stone implements he had found. While the importance of the collection from Kish was seemingly self-evident, Field spent a significant amount of time studying his North Arabian Desert collection. Upon returning to work at the museum, he wrote to the new department of anthropology chair Paul Martin: “This collection, representing more than 400 open-air sites in the high desert regions of Iraq, TransJordan, and Syria, is unique and forms the basis for my studies on the Prehistory of this area.”

Field returned to the Middle East several times in his career, including a final Field Museum North Arabian Desert Expedition of 1934, where he hoped to continue to build his collection of anthropometric data. While his primary goal was to collect skeletal measurements, he again spent time roaming the desert attempting to find stone tools to bring back to Chicago. Field’s later expeditions to Africa and Asia took place under the auspices of the Peabody Museum at Harvard and the University of California.

From left: Field Museum Anthropology Department curators Henry Field, Wilfrid D. Hambly, J. Eric Thompson, and Berthold Laufer, c. 1927. Laufer encouraged Field to continue his explorations of the Kish region.

Although Field may have been influenced in his ideas by other collections of artifacts, such as museum exhibits he had seen in Europe, he clearly believed that his discoveries were the most important of the archaeological material that had been discovered in the region. In an article entitled, “The Cradle of Homo Sapiens,” he briefly discussed his theories on the locality of the earliest Homo sapiens. Field presented competing scholar’s arguments for the evidence of ancient man on each continent and described his finds:

Archaeological evidence shows that men in Paleolithic and Neolithic phases of culture inhabited the North

Arabian Desert. A typologically coup-de-poing [a type of stone tool] was found by the writer at a total depth of eleven feet six inches in the gravels near Bayir, which lies some forty five miles east of Petra. Also, many thousands of flint implements were collected from surface sites in this region.

Field briefly mentioned several other archaeological and anthropological discoveries that he believed provided him with further evidence for his conclusions. He spent a good portion of the work discussing the anthropometric research he conducted at the ongoing Kish excavations. He concluded, “The area suggested by the writer as the probable homeland of Neoanthropic man has yielded archaeological evidence of its continuous inhabitation from early Paleolithic down to contemporary times, and its geograph-

The Field expedition team studied not only artifacts, but also the area’s population. This image from the expedition shows a large native group near the Tigris River in Mosul, a city in northern Iraq.

Henry Field had a deep interest in anthropometrics, the use of skeletal measurements to study the difference between races. During the Kish expeditions, he measured various native peoples (above).

These figures (image of an eye, above, and animal figurines, below) were discovered in Kish during the 1927–28 expedition. ical location occupies a central position between Africa, Europe, and Asia.” Field returned to the subject a year later when he wrote the article “The Antiquity of Man in Southwestern Asia” for the journal American Anthropologist, again using the findings of his recent expedition.

Unlike Henry Field, L. H. Dudley Buxton was never a major proponent of the value of the artifact findings. While Field clearly held the collection in high regard, and mentions it repeatedly in both his academic and popular work, he never appears to have fully convinced other scholars of its primacy in the study of prehistoric migrations in the area. Buxton mentioned the finds of their first season in Iraq almost in passing in the last paragraph of an article published in Man in 1926:

In crossing the desert between Amman and Ramadi in the Narin transport going out, we found a few worked flints. By the courtesy of the Air-Vice

Marshal commanding in Iraq, we were allowed to return in an armoured car patrol. We investigated numerous sites in the desert, and found that worked flints were abundant in certain localities. The specimens are, unfortunately, somewhat atypical, but it would appear that some are Mousterian and other are probably late Paleolithic; some, not unlikely, are

Neolithic. All show a very considerable skill in flintworking and suggest a permanent occupation of what to-day is an area only occasionally visited by wandering tribes.

Although he enjoyed his museum work, above all else throughout his career, Henry Field valued his archaeological field expeditions.

Although Henry Field returned to Kish in later years, none of his future pursuits were as fruitful as the 1927–28 expedition. Field (in pith helmet) and two Arab men cross the Euphrates River on a ferry, 1934.

Henry Field’s visible enthusiasm for his North Arabian Desert collection could have been due to his position as a curator for the artifacts. Field probably felt it his role to encourage other researchers to take interest in the objects housed in his institution. An observer looking back at Henry Field’s North Arabian Desert Expedition could argue that Field overstated the importance of the collection. On the other hand, Field enjoyed moderate success publishing academic articles surrounding the finds and is often remembered for his colorful popular accounts of his adventures. Today, historians tend to recognize that scholars like Field can be deeply influenced by their personal experiences. Field wanted to use his collection to prove that the North Arabian Desert hadn’t been the barrier to migration as some academics had previously thought. In attempting to accomplish this goal, it is possible that Field over-emphasized the importance of his collections, thereby demonstrating that those who study science and history are equally subject to human nature as the rest of us.

Henry Field left the Field Museum in 1941 to join President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s staff as anthropologist and personal advisor. Field remained in Washington, D.C., until late 1945, and later worked with the Peabody Museum at Harvard University and the University of Miami. His expeditions to the North Arabian desert in the 1920s, however, seem to have had the most impact on the ideas of a man who greatly influenced the worldview of those who visited the Field Museum. Due to the current turmoil in many of the lands in which they studied, it is possible that scholars such as Field make an even greater impact today than in previous generations. Henry Field’s lasting influence on the collections of the Field Museum will assuredly be felt for generations to come.

Samuel J. Redman is a graduate student in the Department of History at the University of California, Berkeley.

The Field Museum team uncovered intact artifacts during the 1927–28 expedition, including these two spouted pots and a vase.

Henry Field engaged in one of his favorite pursuits—studying expedition ruins, 1931.

ILL USTRATIONS | 44–45, © The Field Museum, CSA59632; 46 top, © The Field Museum, GN88635; 46 bottom, © The Field Museum, GN81578_A; 47, DN-0064869; 48 top, ICHi-18020; 48 bottom, DN-083335; 49, © The Field Museum, CSA58509; 50–51, © The Field Museum, CSA58576; 52–53, © The Field Museum, ANT401A; 54, Chicago Tribune, July 16, 1927; 55 top, © The Field Museum, CSA59623; 55 bottom, Chicago Tribune, March 10, 1928; 56, © The Field Museum, A98869; 56–57, © The Field Museum, CSA66118; 58, © The Field Museum, CSA76484; 59 left, © The Field Museum, CSA58034; 59 right, © The Field Museum, CSA66037; 60–61, © The Field Museum, A84535_1264; 62, © The Field Museum, CSA67064; 63, DN-0094861.

FOR FUR THER READING | Henr y Field published many volumes about his expeditions during his lifetime, including: The Early History of Man: with Special References to the Cap-Blanc Skeleton (Chicago: Field Museum of Natural History, 1927); The Field Museum-Oxford University Expedition to Kish, Mesopotamia, 1923–1929 (Field Museum of Natural History, 1929); Contributions to the Anthropology of Iran (Field Museum of Natural History, 1939); Ancient and Modern Man in Southwestern Asia (Coral Gables, Fla.: University of Miami Press, 1956–61), and North Arabian Desert Archaeological Survey, 1925–50 (Cambridge, Mass.: Peabody Museum, 1960). His most famous work, however, is probably The Track of Man: Adventures of an Anthropologist (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1953). The Henry Field papers are housed at the University of Miami, Otto G. Richter Library Archives and Special Collections Department. For more on Field Museum explorations, read The Natural History of the Field Museum: Exploring the Earth and its People by Bruce Hatton Boyer (Chicago: Field Museum, 1993). Culture and the City: Cultural Philanthropy in Chicago from the 1880s to 1917 by Helen Horowitz (University of Chicago Press, 1989) offers further historical information on Chicago’s museums. The Field Museum recently received a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities to fund further work on the museum’s Kish project, mainly based on research collected during expeditions from 1923 to 1933. For more information, visit www.fieldmuseum.org.

Index to Volume 34

This index includes author, title, and subject entries. In each page reference, the issue number comes first, followed by a colon and the page numbers(s) on which the reference appears. Illustrations are indicated in italics. If a subject is illustrated and discussed on the same page, the illustration is not separately indicated. activism, 1:8 “Art and Labor” (Starr), 1:18

A

Accardo, Anthony, 2:9

Addams, Jane, 1:5, 6, 9

First Report of a Labor Museum at Hull-House

(Addams and Starr), 1:19 Art classes, 1:13

Twenty Years at Hull-House, 1:8

Twenty Years at Hull-House binding, 1:30

Administration Building

(World’s Columbian Exposition), 2:48–49

Aesthetics, degradation of, 1:12, 14

African American Ninth Battalion, 2:34 Balkans, 2:43 Battery C, ING, 2:24 Big Shoulders Fund, 1:61

African American

bombings, map of, 3:28

discrimination in housing, 3:26–43

Al Capone’s Chicago (museum), 2:15

Amateur Athletic Union, 2:64

American Basketball League, 2:64

American Protestant Study Club of Oklahoma, 3:25

American Unity League (AUL), 3:4, 10, 17–20, 23

Annunzio, Frank, 2:18

Anthropology Building

(World’s Columbian Exposition), 3:46

Anthropometrics, 3:50, 58

Anti-Saloon League, 3:9

“The Antiquity of Man in Southwestern Asia” (Field),

3:59 Art and the Progressive Movement, 1:11 and spirituality, 1:12 universal value of, 1:17 Arts and Crafts Movement, 1:6, 14, 17 Associated Negro Press, 3:43 Attar of roses (Bulgarian product), 2:55 Ayers, Thomas, 1:60 B

The Banjo Palace, 2:9 Barassa, Bernard P., 3:17 Barnett, Claude, 3:43 Basketball Association of America, 2:64 Basketball Hall of Fame, 2:60 Batters, Joe (Anthony Accardo), 2:9 Bellamy, Edward, Looking Backward 2000–1887, 2:48 Berger, Sherry, “Bookbinding and the

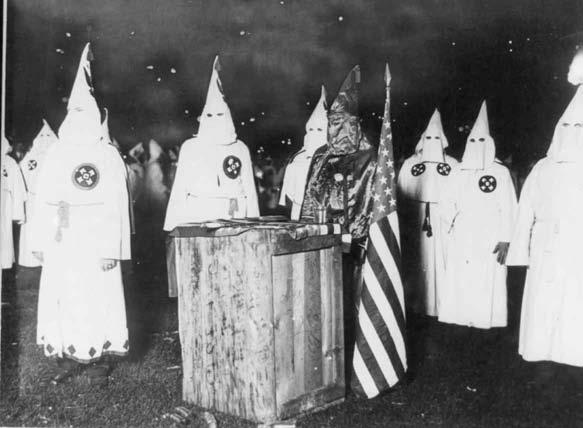

Progressive Vision,” 1:4–31 Berman, Chris, 2:18 Bernardin, Joseph, 1:61 Bielski, Ursula, 2:9 Anti-mask bill, 3:17

Biograph (theater), 2:16, 17 Birth of a Nation (motion picture), 3:4, 6 Bivins, Joy L., “Emmett Till’s Day in Court,” 1:32–51 Black Belt, 3:34–35

Blaustein, Solomon, 2:58 Blue Demons basketball team, 2:64, 66, 68–70 Boas, Franz, 3:46 Bolton, Horace W., History of the Second Regiment, 2:28 “Bookbinding and the Progressive Vision,” article by

Sherry Berger, 1:4–31 Bradley, Mamie Till, 1:34, 35. See also Till-Mobley, Mamie Breeland, Jesse “J. J,” 1:44 Bricks, from St. Valentine’s Day Massacre site, 2:9 Bristow, George W., 3:36 Brooks, J. William, 3:20 Brundage, Avery, 2:64 Bryant, Carolyn, 1:32, 46 Bryant, Roy, 1:32–51, 47 Buckner, Major John, 2:34–35 Bulgaria, 2:43–59 Bulgarian Curiosities, 2:42, 55 Bulgarian Pavilion, 2:54 Bunzey, Rufus S., 2:27–29 Burke, James Joseph, 3:35 Butler Art Building, 1:6, 11 Buxton, L. H. Dudley, 3:47–49, 50, 59 Bynoe, Peter C., 2:17 C

Cahn, Sammy, 2:4 Caldwell, James Hamilton, 1:37 Camp Lincoln, Springfield, Illinois, 2:21–42

Commissary staff at, 2:35 Camp Logan, Springfield, Illinois, 2:27 Capone, Al, 2:4–19 Capone, Salvatore “Frank,” 2:17 Carthan, Wiley Nash, 1:35 Catholic philanthropy, 1:61 Catholic Youth Organization, 2:62 Catholicism, and the Klan, 3:8, 10, 14, 17 Charities, 1:61 Chatham, Gerald, 1:36, 37 Chicago. See also World’s Columbian Exhibition

Bears, 2:60 Black Belt, 3:34–35 bombings, 3:28 central business district decline, 2:7 Commission on Chicago Landmarks, 2:11, 17 convention business, 2:15 crime melodramas, 2:4, 7 crime rate, 2:9, 15 Cubs, 2:68–69 Democratic Party, 2:9 Field Museum of Natural History, 3:45–63 first social settlement, 1:5 gangster tours, 2:15, 17 Gresham neighborhood, 1:53 Hull-House, 1:5 image of, after Capone, 2:4, 7, 9 immigrants, 3:8, 11 job loss, 2:15 Ku Klux Klan in, 3:4–25 labor strikes, 1:6 landmarks, commission on, 2:11 Midway Plaisance, 2:55, 56–57 museums, 1:62, 2:15 Nineteenth Ward, 1:6–7 open housing movement, 1:61 organized crime in, 2:4–19 population decline, 2:15 Progressive Movement in, 1:5–8, 11 public schools, and the Klan, 3:16 race relations, 3:26–43 Race Riot (1919), 3:29 restaurant bombings, 2:9 Sawyer, Eugene, 2:17 Second City title, 2:15 South Side, 1:53, 2:11, 17, 3:29 stockyards, 2:4, 7, 15, 48 suburbs, growth of, 2:7 Union Stock Yard, 2:4, 7, 15 Washington Park subdivision, 3:29–32 West Side, 1:5 white flight phenomenon, 3:43

White Sox, 2:7, 18, 60, 68

Woodlawn neighborhood, 3:32

World’s Fair attempt (1982), 2:11 Chicago Arts and Crafts Society (CACS), 1:14, 17 Chicago Bears, 2:60 Chicago City Council, Klan resolution, 3:13 Chicago Commission on Race Relations, 3:28 Chicago Cubs, 2:68–69 Chicago Daily Tribune, 2:52 Chicago Defender, 2:35, 3:17, 35 Chicago firemen, Klan membership, 3:16, 17 Chicago Lawyers Guild, 3:31 Chicago Public School Art Society (CPSAS), 1:11–12, 17 Chicago Sun Times, 1:62–63, 2:17 Chicago Tribune, 2:18, 3:13 Chicago White Sox, 2:7, 18, 60, 68

Capone at a Sox game, 2:19 Children, art classes for, 1:13 Childs, Susan Gates, 1:8 Christ of Cynewulf (binding), 1:24–25 Civil Rights Movement, 1:32–51 Clarke, Edward, 3:9 Clerk (Emmett Till trial), 1:48 Clinnin, John V., 3:13 Cobden-Sanderson, T. J., 1:21, 28 Commissary staff, Camp Lincoln, 2:35 Commission on Chicago Landmarks, 2:11, 17 Commonwealth Edison, 1:52, 54 Company H, First Regiment Infantry, 2:23 Conference for the Elimination of Restrictive

Covenants, 3:42 Connecticut National Guard, 2:23 Convention business, in Chicago, 2:15 Cook, Albert S., 1:25 Cook County Democratic Party, 2:9 Corman, Roger, 2:9 Cothran, John, 1:36 Court Reporter (Emmett Till trial), 1:49 Covenants, restrictive, 3:26–43 Craftsmanship, 1:17–18, 21–22 Crime, 2:9, 15

Crime melodramas, 2:4, 7

Crime Story (television series), 2:15 Crusade of Mercy, 1:61 Cullerton, John F., 3:17

D

Daley, Richard J., 1:57, 2:7, 9, 15 Davis, Allen F., 1:5

Dawn (Klan newspaper), 3:5, 14, 16, 18, 23, 25 Dee, Ruby, 3:26 Delaney, Margaret Mary, 2:66 Democratic Party, in Cook County, 2:9 DePaul University, 2:60, 62, 69

Blue Demons basketball team, 2:64, 66, 68–70

Dever, William E., 3:17

Devine, Michael J., 2:18 Dickerson, Earl, 3:30–31, 35–36, 40, 41, 43

Dillinger, John, 2:4, 17 Dimna (excavation specialist), 3:44 Discrimination. See Racial discrimination

Drake School, 1:12 Dunne, Edward E., 2:28

E

Edgar, Jim, 1:59 1893 World’s Columbian Exhibition, 2:4, 11, 42–59.

See also Midway Plaisance Eighth Regiment, ING, 2:34–35 “Emmett Till’s Day in Court,” article by Joy L. Bivins, 1:32–51

Emrick, Mortimer E., 3:18

England, Arts and Crafts Movement in, 1:17 Enright, James, 2:66 Espionage and Sedition Acts, 3:8 Evans, Hiram W., 3:21, 23, 25

Evans, Susan, 1:58

The Fables of Bidpai binding, 1:22 Fair Housing, 3:26–43 Faulkner (businessman), 3:38–39 Ferdinand (Prince), 2:54 Field, Henry, 3:44, 45–63

“The Antiquity of Man in Southwestern Asia,” 3:59

The Track of Man, 3:50 Field, Marshall, 3:45 Field, Stanley, 1:62, 3:46, 48 Field Columbian Museum. See Field Museum of

Natural History Field Museum of Natural History, 3:45–63 The Fight over Faith (documentary), 1:62 Firemen in Chicago, and, Klan membership, 3:16, 17 First Bulgarian Agrarian-Industrial Exposition, 2:51–52 First Illinois Cavalry (ING), 2:20, 25 First Infantry Brigade (ING), 2:29 First Regiment Infantry (ING) officers, 2:21 First Report of a Labor Museum at Hull-House (Addams and Starr), 1:19 Foreman, Colonel Melton J., 2:28 Fraley, Oscar, 2:7

G

Gambling, and organized crime, 2:9 Gangster tours, 2:15, 17 Giancana, Antoinette, 2:11–12

Giancana, Sam, 2:11–12 Gibson, Truman K., “We Belong in Washington Park,” 3:26–43

“The Gilded Age of Camp Lincoln, 1886–1916,” article by Eleanor L. Hannah, 2:20–41 Gilfoyle, Timothy J., “Making History: Interviews with

Carol Marin and James J. O’Connor, 1:52–64 Golovanov, Filaret, 2:44 Governor’s Day, Illinois National Guard, 2:28 Grange, 1:8 The Great Exhibition of Works of Industry of all Nations, 2:51 Green, George, 3:17 Gresham neighborhood, 1:53 Griffith, D. W., 3:4, 5 H

Hall, James Lowell, 3:32 Hall of Man, 3:50 Hall of Prehistoric Man, 3:50 Hall of Races of Mankind, 3:50, 52–53 Hambly, Wilfrid D., 3:56 Handicrafts. See Craftsmanship Hannah, Eleanor H., “The Gilded Age of Camp

Lincoln, 1886–1916,” 2:20–41 Hansberry, Carl, 3:26, 29, 31–32, 35, 38–39, 43

“A Plan for the Negro’s Advancement in Business and Industry,” 3:41 Hansberry, Lorraine, A Raisin in the Sun, 3:26–27, 36 Harlem Globetrotters, 2:65, 68 Harvard Annex, 1:9, 10 Hastie, William, 3:39 Hate crimes, 1:32–51 Hayes, Charles, 2:18 Hayes, David, 2:62 Henrici Restaurant, 1:5–6 Hill, W. A., 3:18 Hinshaw, Marvin V., 3:18 History of the Second Regiment (Bolton), 2:28 History vs. heritage, 2:18 Hodges, Robert, 1:40–41 Hoffman, Malvina, 3:52 Holtzman, Jerome, 2:62 Horne (businessman), 3:38–39 Hotel Employees and Restaurant Employees

International Union, 2:9 Houghteling, Sergeant J. L., 2:37 Housing codes, 3:26–43 Howitzer, 2:24 Hull-House, 1:5–6, 8, 10, 11, 15–16

Hull-House Labor Museum, 1:18, 19–20 Hull-House Maps and Papers, 1:18 Hutchins, Robert Maynard, 3:35–36, 37, 43 I

Illini Student Union, 1:53 Illinois Central Railroad (Seventy-first Street station), 2:61 Illinois Historic Preservation Agency, 2:18 Illinois Historic Sites Advisory Council, 2:18 Illinois National Guard (ING), 2:20–41 Illinois State Register, 2:29 Illinois Supreme Court, 3:39 Immigrants, 3:8, 11 Industrial Arts Magazine articles by Starr, 1:26, 29 Industrial Revolution, 1:12 Industrialism, effects of, 1:17–18 ING. See Illinois National Guard (ING) Internal Revenue Service, 2:4, 12 International world’s fairs, beginnings of, 2:51 Interstate National Guards Association, 2:23 Invisible Empire of the Ku Klux Klan, 3:4–25 Ireland, George, 2:63 Isolationism, 3:8 Ivanov, Petko, “To Chicago and Back: Bulgaria and the

World’s Fair of 1893,” 2:42–59 J

Jackson, Kenneth T., 3:11 Jefferson, Bernard, 3:39 Jeffrey Theater, 2:61 John Paul II, 1:60 Jordan, Michael, 2:18 Jury (Emmett Till trial), 1:50–51 K

Kamelia (Klan organization), 3:25 Karamanski, Theodore J., “The Legend of Scarface,” 2:4–19 Kay, Dick, 1:63 Keeper of the National Register, 2:18 Keeping the Faith (documentary), 1:62 Keller, Joseph G., 3:18 Keogan, George, 2:63, 66 Keough, Don, 2:69 Kerner, Otto, 2:9

“The Klan Moves North,” article by David Craine, 3:4–25 Konstantinov, Aleko, 2:43–50

Krone, Philip, 2:17–18 Ku Klux Klan, 3:4–25

Kupcinet, Irv, 2:17

L

La Touraine (ship), 2:44 Labor Museum, 1:18, 19–20

Lake Zurich, Illinois, Klan rally in, 3:12, 13 LaSalle Cavaliers (basketball team), 2:64

Lathrop, Barbour, 3:47 Laufer, Berthold, 3:54, 56 Lears, T. J. Jackson, 1:14 “The Legend of Scarface,” article by Theodore J.

Karamanski, 2:4–19

Levell, Mark P., 2:18

Levi, Ed, 3:36

Lexington Hotel, 2:4, 10, 11–13 Liberal Arts Building (World’s Columbian Exposition), 2:50

Liebling, A. J., 2:7 Lila’s Hope (documentary), 1:62 Lillie, Frances Crane, 1:31 “The Liturgy of Palm Sunday and Holy Saturday” (Starr), 1:8

Longworth, Richard, 2:18 Looking Backward 2000-1887 (Bellamy), 2:48 Los Angeles population overtakes Chicago, 2:15 Love, C. W., 3:13

Loyola University Law School, 2:62 Lueder, Arthur C., 3:17

Lujan, Manuel, 2:18

Magers, Ron, 1:56, 57 “Making History: Interviews with Carol Marin and

James J. O’Connor,” article by Timothy J. Gilfoyle, 1:52–64 Making History Award winners

Marin, Carol, 1:52–64

McKenna, Andrew James, 2:60–72

Meyer, Ray, 2:60–72

O’Connor, James J., 1:52–64 Malloy, Edward “Monk,” 2:69 Mandela, Nelson, 1:61 Manley Career Academy, 1:62 Manufactures Building (World’s Columbian

Exposition), 2:50, 51 Marin, Bernice (Johnson), 1:52 Marin, Carol, 1:52–64 Marin, Knut, 1:52 Marin Corp Productions, 1:62 Marshall, Colonel John R., 2:35, 36 Martin, Paul, 3:55 Massachusetts National Guard, 2:23 McKenna, Andrew (elder), 2:60 McKenna, Andrew James, 2:60–72 McKenna, Anita Fruin, 2:60 McMahon, Franklin, 1:32–51 McNeil, Claudia, 3:26 McReynolds, James, 3:41 Merritt (General), 2:28 Meyer, Barbara (Hummel), 2:60 Meyer, Joey, 2:68 Meyer, Joseph, 2:60 Meyer, Margaret Mary (Delaney), 2:66 Meyer, Ray, 2:60–72 Michigan City White Caps, 2:68 Midway Plaisance, 2:55, 56–57, 58–59 Milam, Juanita Thompson, 1:47 Milam, J. W., 1:32–51 Militia, 2:23–24 Millard, Arthur M., 3:17 Mims, Benjamin “B. L.”, 1:36 Ming, Robert, 3:39, 41 Miss Kirkland’s School for Girls, 1:9 Modernity, impact on aesthetics, 1:12, 18 Mollison, Irvin C., 3:32, 35, 39, 41 Moore (lawyer), 3:41 Morris, Art, 2:66 Morris, William, 1:17 Mortensen, Peter A., 3:16 Mosley, Don, 1:58, 64 Motion picture theaters, 2:16, 61 Murphy, Morgan, 1:60 Museums, in Chicago, 1:62, 2:15 “My Kind of Town” (popular song), 2:4 N

NAACP, 3:31 Nabrit, Jim, Sr., 3:39 National Association for the Advancement of Colored

People, 3:31 National Basketball Association, 2:64 National Basketball League, 2:64 National Collegiate Athletic Association tournament, 2:66 National Park Service, 2:18 National Register of Historic Places, 2:17–18 National Wrecking Company, 2:9 NBC Today show, 1:56 Ness, Eliot, 2:7 New York World, Klan exposé, 3:9, 11 Niagara Falls, 2:46 North Arabian Desert Expeditions, 3:45–63 Notre Dame University, 2:63 Nuclear energy, at Commonwealth Edison, 1:57 O

O’Connor, Ellen, 1:59, 60 O’Connor, Fred, 1:53 O’Connor, Helen (Reilly), 1:53

O’Connor, James J., 1:52–64 O’Donnell, Patrick H., 3:18, 23 Oglesby, Richard J., 2:27, 29 Oil wells, 3:38–39 Open housing movement in Chicago, 1:61 Organized crime, 2:9 P

Pace, Harry H., 3:31, 32 Palmer, A. Mitchell, 3:8 Palmer, Charles, 3:25 Paradise Lost binding, 1:27 Park Forest, 2:7 Park Manor (Capone family residence), 2:4, 14, 17 Park Manor Neighbors Community Council, 2:18 Parker, John, 3:18 Patey, George, 2:9 Paul, Leander, 2:62 Pauley, Jane, 1:56 Peabody Museum, 3:55 Perrett, Geoffrey, 3:12 Philanthropy, 1:61 “A Plan for the Negro’s Advancement in Business and

Industry” (Hansberry), 3:41 Poitier, Sidney, 3:26 Prishlets (Bulgarian émigré society), 2:55 Progressive Movement, 1:5–8, 11, 20, 28 Prohibition, 2:4, 7 Protestants in Chicago, and the Klan, 3:12–13, 16 Public School Art Society (Chicago), 1:11 Putnam, Fredric Ward, 3:46 Q

Quentin, Jarloth, 2:62 Quigley Prep School, 2:62 R

Race Riot (1919), 3:29 Racial discrimination, 1:32–51, 61, 2:35, 70, 3:26–43 Radoslavov, Stoian, 2:44 A Raisin in the Sun (Hansberry), 3:26–27, 36 Ray, Lieutenant Cary T., 2:26, 30, 40 Real-estate covenants, 3:26–43 Red Cross, 3:9 Redman, S. J., “Yesterday’s City: Henry Field’s

Legendary Expeditions,” 3:45–63 Reed, Willie, 1:42–43 Regenstein Library, 2:43 Reinsdorf, Jerry, 2:68 “The Renaissance of Handicraft” (Starr), 1:17, 27 Restaurant bombings, 2:9 Rivera, Geraldo, 2:12 Roberts, Adelbert H., 3:17 Robin and the Seven Hoods (motion picture), 2:4 Rockford Female Seminary, 1:9 Rockford Seminary Magazine, 1:17 Rolling Meadows, Illinois, 1:52–54 Romanism. See Catholicism, and the Klan Rosenwald, Julius, 1:62 Ruskin, John, 1:17–18 Rutledge, Grady, 3:10, 17–20, 23 S

Salvation Army, 3:9 Samuelson, Timothy, 2:17 Sawyer, Eugene, 2:17 Schroeder, Eric, 3:55 Schwarz, Sidney, 2:67 Schwarz Paper Company, 2:60, 63–64, 67 Settlement Movement, 1:5–6 Seventh Regiment, ING beer riot, 2:34 officers, 2:26 Seyferlich, Arthur F., 3:17 Shannon, McKenzie, 3:41 Shea, Dixie, 3:18 Sheil, Bernard, 2:62 Shepherd, Robert H., 3:17, 23 Shopov, Vulko, 2:52–54 Simmons, William Joseph, 3:4, 8, 9, 11, 23, 25

Sinatra, Frank, 2:4 60 Minutes, 1:56 Skeletal measurements, 3:50, 58 Smith, Lieutenant Bruce D., 2:36 Smith, Robert B. III, 1:37 Social values, and art, 1:8 Socialist Party, 1:6 Sofia Stefan Aivazyan, 2:55 Sofronieva, Tzveta, 2:59 Some German Woodcuts of the Fifteenth Century (binding), 1:28 Some Like It Hot (motion picture), 2:7 “Soul Culture” (Starr), 1:17, 27 South Side, 1:53, 2:11, 17, 3:29.

See also Washington Park subdivision Southern Publicity Association, 3:9 Spanish American War, 2:23, 39 Spirituality, and art, 1:12 Sponsa Regis, 1:8 Springer, Jerry, 1:57–59 Springfield, Illinois, 2:27 St. Agatha’s school, 2:62, 66 St. Ignatius High School, 1:53 St. Patrick’s High School, basketball championship, 2:62–63 St. Philip Neri parish, 2:60 St. Valentine’s Day Massacre, 2:4, 7, 8, 9 Stack, Robert, 2:7 Stagg, Amos Alonzo, 1:53 Starr, Caleb Allen, 1:8 Starr, Eliza Allen, 1:9 Starr, Ellen Gates, 1:4, 5–31

“Art and Labor,” 1:18 conversion to Catholicism, 1:9, 11

Industrial Arts Magazine articles, 1:26, 29

“The Liturgy of Palm Sunday and Holy Saturday,” 1:8

“The Renaissance of Handicraft,” 1:17, 27

“Soul Culture,” 1:17, 27 Steiger, Rod, 2:7 Stockyards, 2:4, 7, 15, 48 Stradford, C. Francis, 3:31 Strider, H. C., 1:34, 47 Strikes, and Illinois National Guard interventions, 2:23 Sunbow Foundation, 2:11–12 Supreme Court, 3:39 Supreme Liberty Life Insurance Company, 3:31, 35, 38 Swain, Col., 2:24 Swango, Curtis, 1:33 T

Tanner, John R., 2:34 Tanner, Mrs. John R., 2:20 Television, journalism vs. entertainment, 1:56–59 Texas grip (rifle position), 2:26 Thomas, Rowland, 3:11 Thompson, J. Eric, 3:56 Till, Emmett, 1:32–51 Till, Louis, 1:32 Till-Mobley, Mamie, 1:32 “To Chicago and Back: Bulgaria and the World’s Fair of 1893,” article by Petko Ivanov, 2:42–59 To Chicago and Back (travelogue), 2:43–50 Tolerance (anti-Klan newspaper), 3:15, 18, 20, 23 Tommy Gun’s Garage, 2:13, 15 Tourism, 2:48, 50–51 The Track of Man (Field), 3:50 Travel, for business vs. intellectual quest, 2:48, 50 Turkey, opposition to Bulgarian presence at the

Columbian Exposition, 2:52 Turkish Building (World’s Columbian Exposition), 2:51 Twenty Years at Hull-House (Addams), 1:8, 30 Tyler, Elizabeth, 3:9 U

U. S. Camera Corporation, 2:63 Unicom, 1:56 Union Stock Yard, 2:4, 7, 15 Unions, and organized crime, 2:9 United States Supreme Court, 3:39 United Way, 1:60, 61

University of California, 3:55 University of Chicago, 3:35–36 law school, 3:35

Regenstein Library, 2:43 Untouchables Tours, 2:13, 15, 17 The Untouchables motion picture, 2:13, 15 television drama, 2:7 Upshaw, W. D., 3:11 Urban vs. rural life, 3:6, 8 Utley, Jonathan, 1:54 V

Vaults (Al Capone’s), 2:12–13 Veblen, Thorstein, 1:14 Vedernikov, E. (cartoon by), 2:46 Veeck, Bill, 2:67 Velo, Kenneth, 1:64 Verberg, Peter, 1:23 Victory Gardens Theater, 2:16 W

Walleen’s World (television show), 1:54 Ward, Harris, 1:55, 60 Warner Brothers melodramas, 2:4 Washington Park subdivision, 3:29–32. See also

Woodlawn Property Owner’s Association Waugh, William F., 2:5 WBIR-TV, 1:56 “We Belong in Washington Park,” article by Truman K.

Gibson, Jr., 3:26–43 West Side, 1:5 Wheeler, Harris A., 2:28 White Caps (baseball team), 2:68 “White City,” 2:4

See also World’s Columbian Exposition White flight phenomenon, 3:43 White Sox

See Chicago White Sox Wisbrod, Louis D., 3:18 Without Sanctuary: Lynching Photography in America (exhibition), 1:32 WMAQ-TV, 1:56–59 Women educational opportunities, 1:9

Klan auxiliary, 3:23, 25 labor strikes, 1:6

Sunbow Foundation, 2:11–12 Woodlawn neighborhood, 3:32 Woodlawn Property Owner’s Association, 3:32–33, 35 World’s Columbian Exposition, 2:4, 11, 42–59, 3:46.

See also Midway Plaisance World’s fairs, beginnings of, 2:51 Wright, Moses, 1:34, 38–39 Wrigley, William, Jr., 3:20, 23 WSM-TV, 1:56 WTTW, 1:63 Y

Yates, Sidney, 2:18 “Yesterday’s City: Henry Field’s Legendary

Expeditions,” article by S. J. Redman, 3:45–63 Yovchev, Iliya, 2:55–56