32 minute read

The Klan Moves North

In the 1920s, the Ku Klux Klan emerged in Chicago to fight the perceived dangers of urban life.

DAVID CRAINE

Advertisement

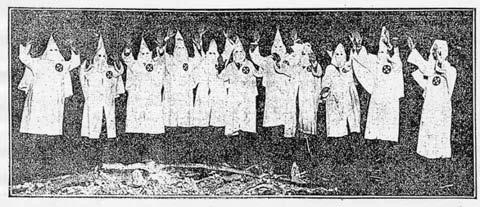

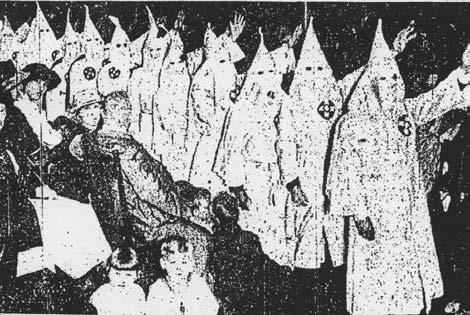

Leaders preside over a meeting of thousands of Klansmen from Chicago and northern Illinois, c. 1920. F rom 1921 to 1925, Chicago became embroiled in a controversy that many associated with the South. As part of a nationwide movement, the Invisible Empire of the Ku Klux Klan established itself in the city and within a year attracted thousands of adherents. Preaching “100 percent Americanism” and white Protestant supremacy, the Chicago Klan found fertile ground for its ideals of bigotry. Unlike its Reconstruction-era predecessor, the Klan of the 1920s tailored its message of hate to each territory it invaded. In Chicago, the message preyed predominantly on the insecurities and fears of Protestants against Catholics. For four years, the Klan flourished, publishing a weekly newspaper and holding meetings, social events, and recruitment drives. In response, a small group founded the American Unity League (AUL), devoted to the eradication of the Klan in the city and across the country. Publishing its own newspaper, the AUL made significant inroads in their mission against the Klan. But, after an intense four-year battle, the Chicago Klan and its detractors disappeared, all but forgotten to memory and history.

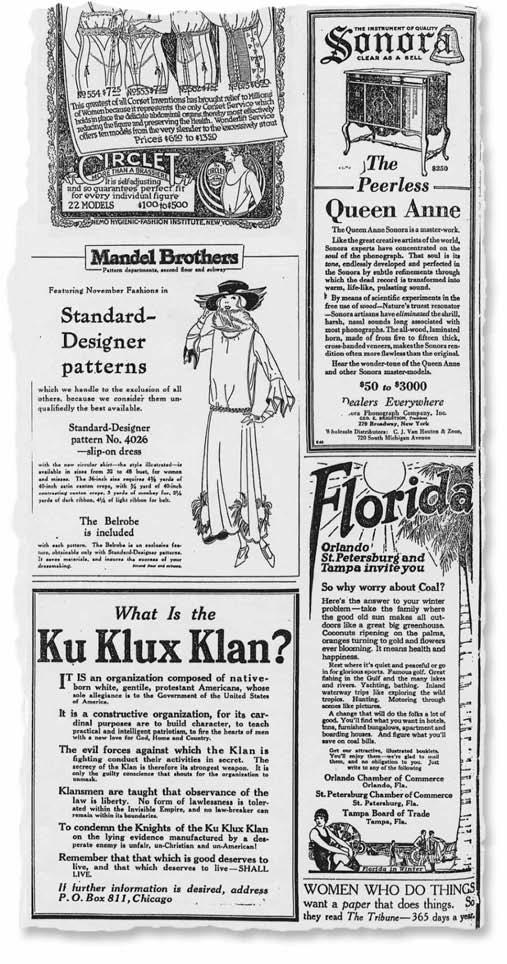

Led by Colonel William Joseph Simmons, the revival of the Ku Klux Klan occurred atop Stone Mountain in Georgia in November 1915, two weeks before the Atlanta opening of D. W. Griffith’s cinematic homage to the Klan of the Reconstruction era, Birth of a Nation. The original Klan was founded as a Southern, rural, antiblack movement after the Civil War. The group’s reemergence in the early twentieth century was a reaction to societal changes of a different nature.

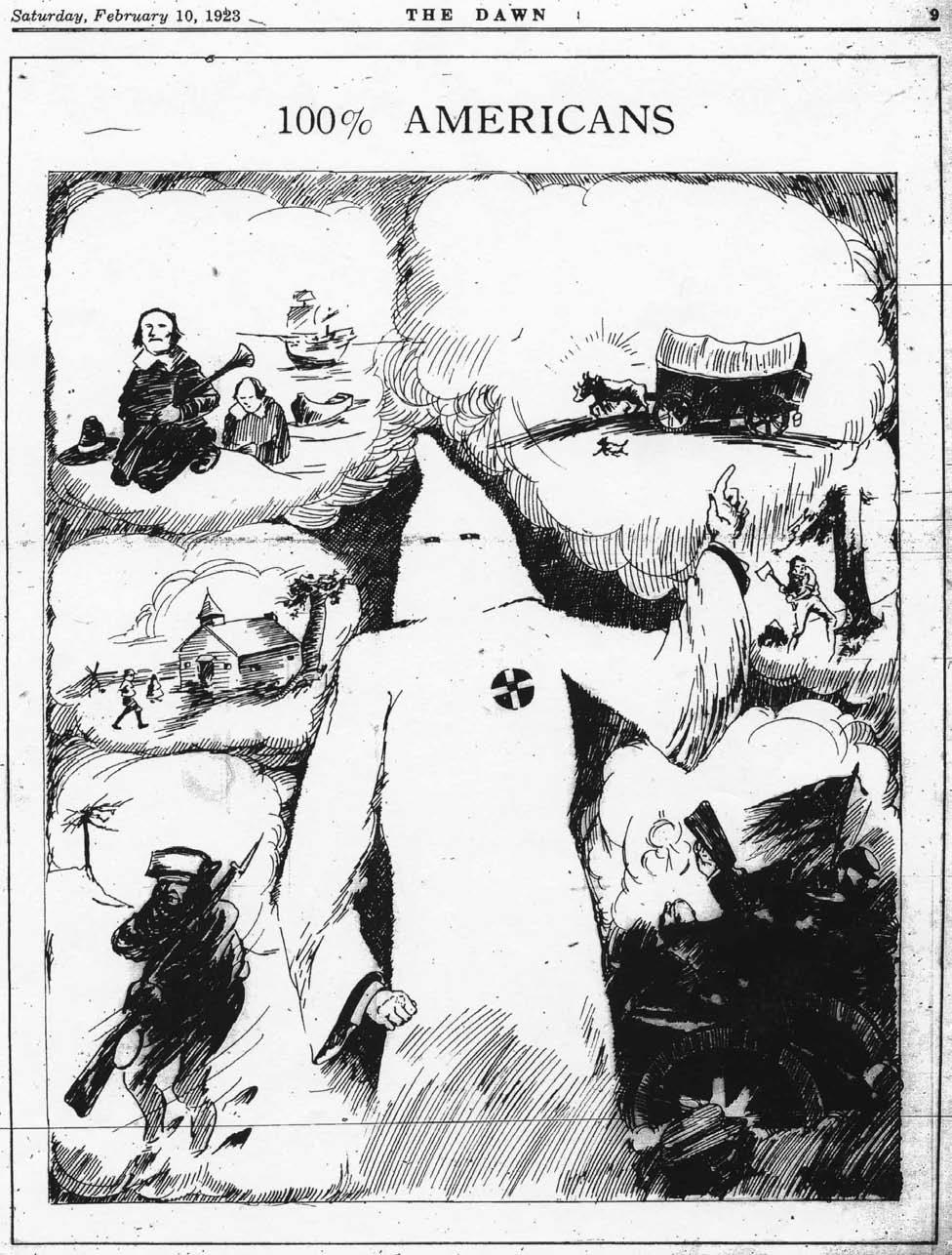

Dawn, the Klan-endorsed newspaper, published this depiction of “100 percent Americans” in February 1923. The sketch groups Klansmen among pilgrims, pioneers, and soldiers.

The census of 1920 showed that for the first time more Americans lived in cities than in rural areas, bringing significant changes to the country’s cultural landscape. Urban popular culture—with its jazz rhythms, mass media, bright lights and literary experimentation—lured millions of young, rural Americans. For many with traditional conservative values, however, urban culture remained bewildering and frightening. The forces of modernity and diversity inherent in twentiethcentury urban culture triggered in many a desire to return to times of so-called normalcy. The flappers and rogues of the Jazz Age, whose lifestyles touted fast cars, suggestive music, and loose sexuality, epitomized the dangers of urban life.

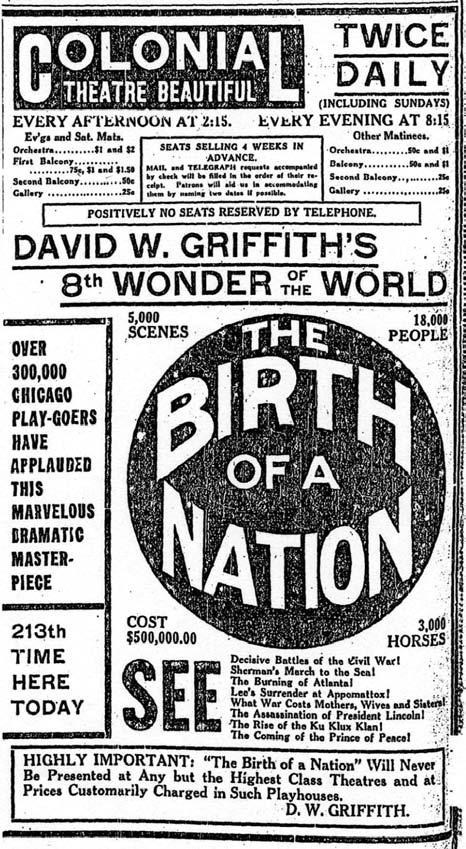

In the early twentieth century, the ideals of the new Klan appealed to many Americans, as evidenced by the popularity of Birth of a Nation, D. W. Griffith’s cinematic portrayal of the Reconstructionera Klan, which opened in 1915. To advance their cause and solicit memberships, the Chicago Klan placed advertisements in local newspapers. Such ads ran among promotions for women’s clothing, furniture, and Florida vacations.

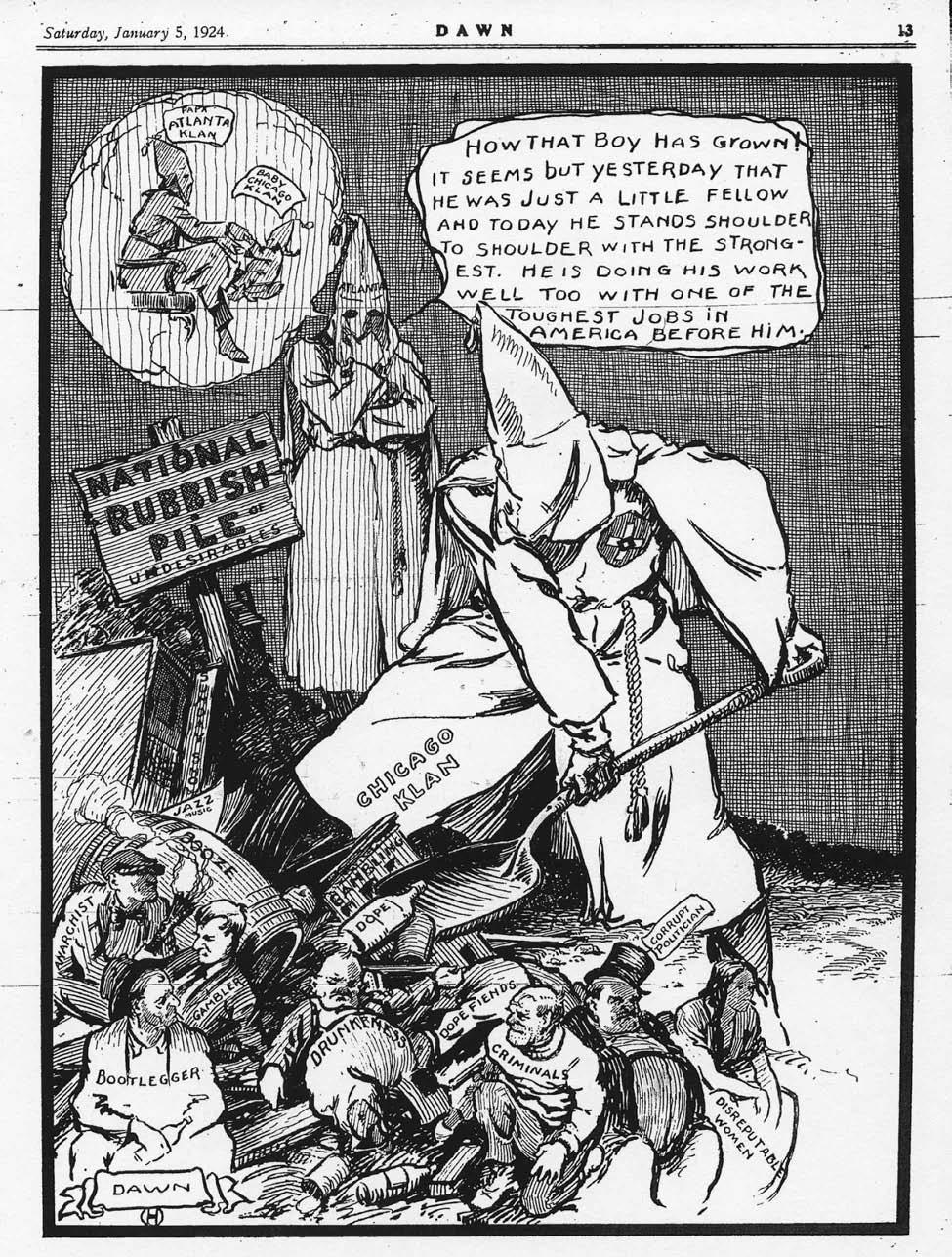

In response, the Ku Klux Klan offered an illusory hope of imposing rural values on this environment by returning to an idealized version of the status quo of the 1890s: fundamental Protestantism, white supremacy, marital fidelity, and respect for paternal authority. All laws were to be obeyed—particularly Prohibition. The Klan also targeted criminals, dishonest politicians, prostitutes, bootleggers, gamblers, and grafters. In their struggle to resist the modern world, the Klan believed that “liberals were a worse menace than foreigners.”

The growth of American cities, particularly in the industrial North, was due in large measure to the huge

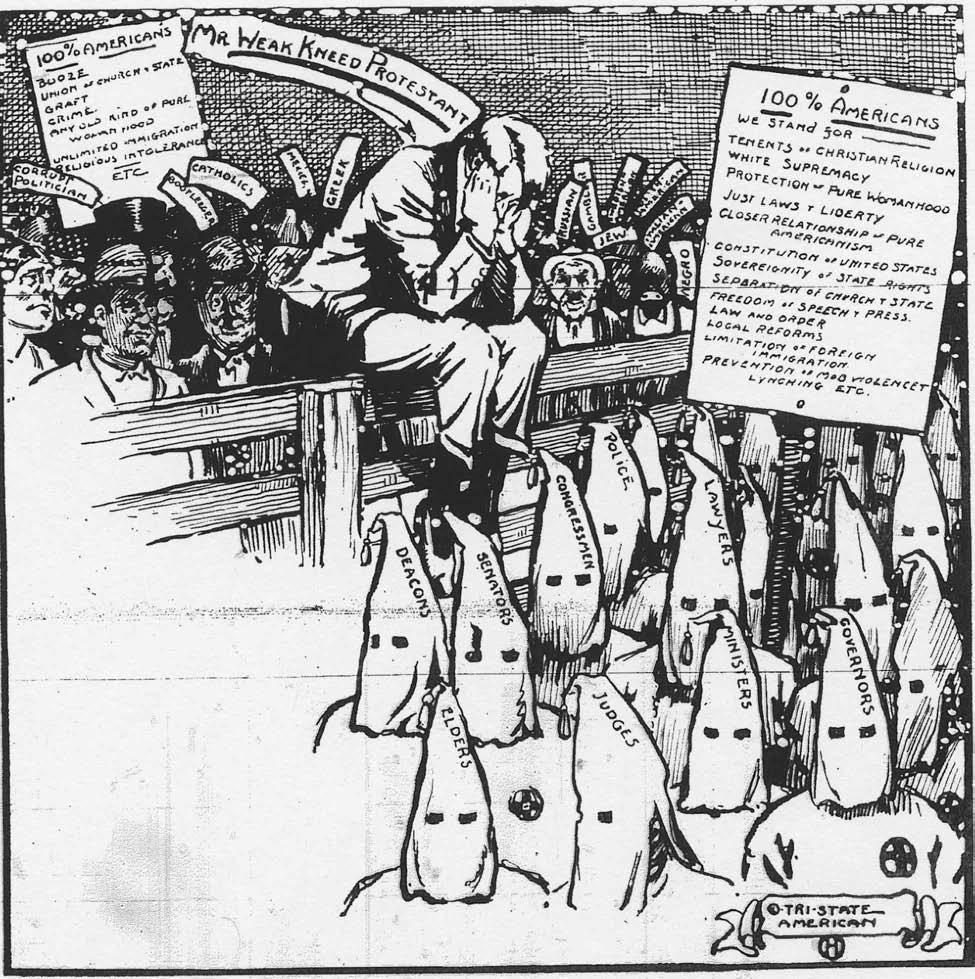

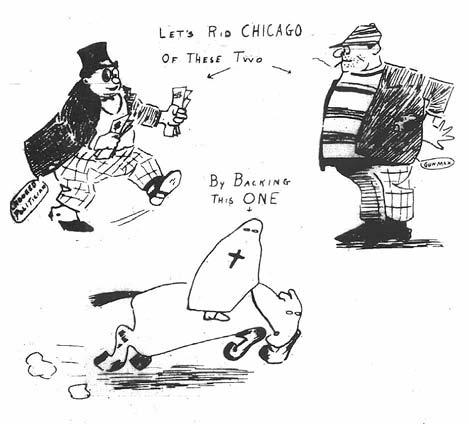

The Chicago Klan portrayed itself as a national force against undesirable urban influences such as booze, anarchists, dope fiends, and disreputable women.

influx of eastern and southern European immigrants, whose languages, customs, appearance, and, perhaps most significantly, religions were distinctly different from those of earlier immigrants from northern and western Europe. These new immigrants—Poles, Italians, and Russians, in particular—were largely Catholics and Jews. While the new Klan did not discard the old Klan’s attitudes toward African Americans, it focused primarily on Catholics. Ridiculed as “popery” and “Romanism,” antiCatholicism proved to be an effective recruiting tool. The Klan portrayed Catholics as being disloyal to the United States, their true allegiance reserved exclusively to the Pope, whose alleged secret mission was world domination. Fantastic stories circulated about Catholic plans for revolution. One rumor claimed Catholic families celebrated the births of their babies by burying a gun and fifty rounds of ammunition for each child beneath the local church. When the children reached shooting age, the guns would supposedly be excavated and used to seize power and give the United States to the Pope. In Kokomo, Indiana, when a rumor spread that the Pope was “pulling into town on a southbound train from Chicago to take over,” a mob formed and stoned the train.

Other events help explain the climate that made the revival of large-scale Klan support possible. Widespread disillusionment over World War I left many desiring a return to isolationist policies. Government-sanctioned discrimination against Germans and the Espionage and Sedition Acts conditioned many Americans to accept intolerance of differences. The anticommunist crusade of Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer and the trial of anarchists Sacco and Vanzetti illustrated an America where dissent, especially when brandished by immigrants, was not to be tolerated.

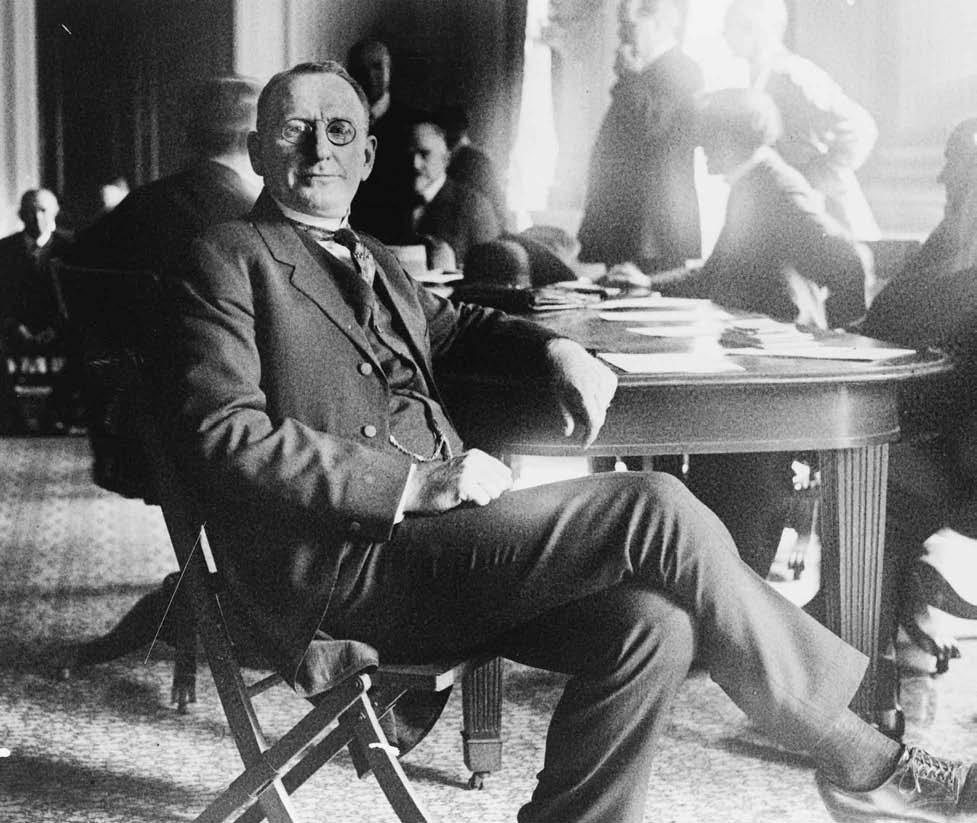

Klan leader William Joseph Simmons, known among members as the Imperial Wizard, sits at a table during the U.S. Congress’s investigation of his organization.

While the Ku Klux Klan had roots in the rural South, the new Klan spread rapidly through the urban North, and by 1922, Chicago had the largest membership of any metropolitan region in the United States. This exponential growth was unforeseen by Simmons in 1915; in the first five years of its existence, Simmons’s Klan had procured a meager membership of less than three thousand Southern men. National expansion and the Klan’s growth in the urban North was the result of two events: Simmons’s agreement to turn over recruitment to two enterprising promoters in 1920 and an exposé of the renewed Klan in the New York World in 1921.

Edward Clarke and Elizabeth Tyler formed the Southern Publicity Association in 1917 and used their talents to market organizations, including the AntiSaloon League, the Salvation Army, and the Red Cross. After Tyler’s son-in-law joined the Klan, Clarke and Tyler contracted with Simmons to create a propagation department in exchange for 25 percent of each new recruit’s ten-dollar initiation fee. To expand recruitment nationwide, Clarke and Tyler devised a strategy where paid organizers studied their local territories to identify groups that might be considered “enemies” to nativeborn Protestant whites: Mormons in Utah, union radicals in the Northwest, and Asian Americans on the Pacific Coast. Using contemporary marketing and advertising techniques, the organizers began by soliciting their friends and acquaintances and followed all contacts with Klan membership applications, propaganda, and requests for dues. The national office sent lecturers—often ministers—to speak about the need for the Klan’s crusade of militant Protestantism. Their strategy worked. During the first six months of their efforts, Clarke and Tyler claimed the recruitment of

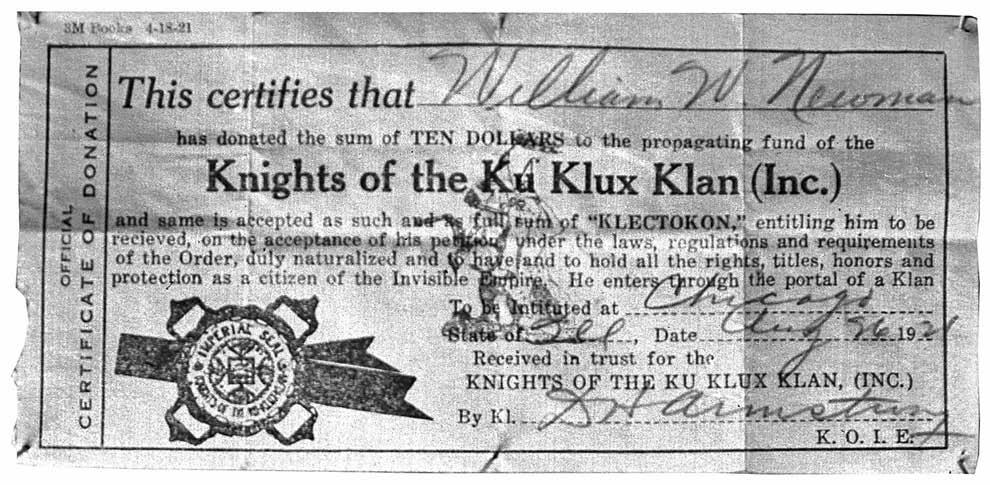

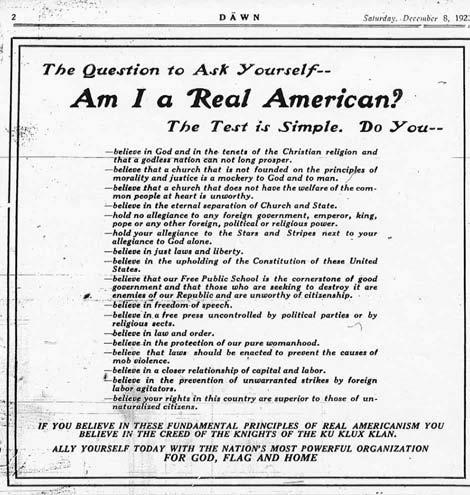

Above: Klan certificate of membership issued to William W. Newman of Chicago. Below: Dawn printed this “test” for potential Klansmen above a tear-off, mail-in membership coupon.

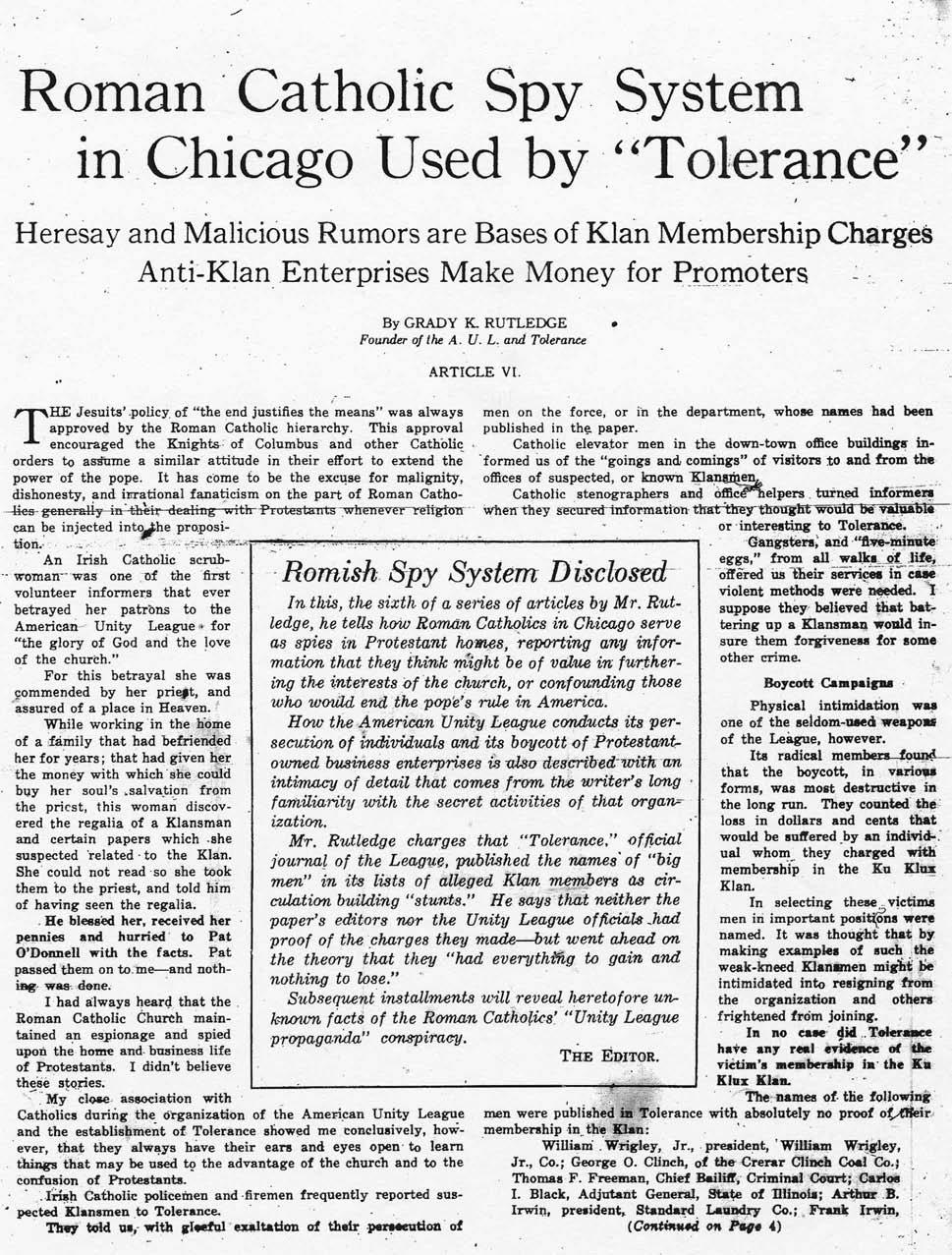

After founder Grady Rutledge left the American Unity League, he joined the Klan and became a regular contributor to Dawn. Many of his articles exposed the inner workings of the AUL’s newspaper, Tolerance.

eighty-five thousand new members. Ironically, the marketing strategies they employed to sell the Klan mirrored many of the same techniques being used by the advertising industry to market the urban culture of the Jazz Age—movies, radio, magazines, automobiles, and clothing— that the Klan was challenging.

Alarmed by the Klan’s growth nationwide, the New York World began a threeweek exposé of the group on September 6, 1921. Based on months of research by reporter Rowland Thomas, the articles placed particular emphasis on the more violent aspects of the Klan and were carried by eighteen newspapers across the country. Partly as a result of the World’s coverage, the U.S. Congress began an investigation of the Klan. Simmons was called to testify and used the occasion to promote the Klan’s virtues. He stated that the organization neither promoted nor tolerated violence of any kind and that the Klan’s oath and ritual were a matter of public record rather than cloaked in secrecy. He further testified that the violent actions attributed to the Klan were perpetrated by troublemakers hiding behind the robes of a Klansman. According to historian Kenneth T. Jackson, Simmons dramatically swore: “If the Ku Klux Klan were guilty of a hundredth part of the charges made against it, ‘I would from this room send a telegram calling together the grand kloncilium [executive council] for the purpose of forever disbanding the Klan in every section of the United States.’” In the end Congress did nothing, partly because Representative W. D. Upshaw of Atlanta introduced a bill calling for similar investigations of other “secret” societies, including the Catholic-based Knights of Columbus.

Through the newspaper reports and investigations, the Klan received free, nationwide publicity. Newspapers across the country carried the New York World’s exposé, and the Klan became a popular topic of conversation. Within a year, membership applications—many of them facsimile blanks printed in the newspapers—poured into Klan headquarters, increasing the rolls from one hundred thousand to almost one million nationally.

At first glance, Chicago seemed to be an unlikely place for Klan recruitment. The city’s staggering growth—from just five hundred thousand in 1880 to almost three million in 1920—was largely a result of immigrants from southern and eastern Europe and growing migration from the South. The census of 1920 showed that Chicago was home to more than one million Catholics; 800,000 foreign-born immigrants; 125,000 Jews; and 110,000 African Americans. The city also seemed to

This map illustrates the distribution of the Chicago Klan in 1923. Each asterisk represents two hundred Klansmen. Although the organization charted chapters throughout the city, many were based in neighborhoods on the North and South Sides.

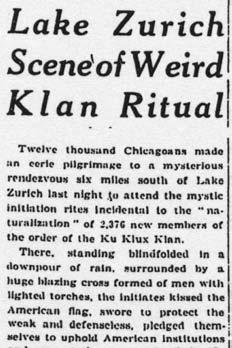

The Chicago Tribune covered the Klan’s event.

embrace and embody all that was modern and exciting in the Roaring Twenties. Breweries, speakeasies, and underworld crime gave the city a national reputation for vice, corruption, and lawlessness. Yet by 1922, Chicago had the largest Klan membership of any city in the nation. Fully 13 percent of those eligible—adult, white, Protestant men—in Chicago had joined the Klan. What accounted for the unprecedented popularity of such a rural-based movement in a giant, cosmopolitan metropolis like Chicago? The answer almost certainly lies in the origins of the Protestant population of Chicago.

The Klan was small-town in spirit, and in some ways, so was Chicago. The Klan of the 1920s flourished in newer cities and those that had grown dramatically within a generation or two: Detroit, Milwaukee, Pittsburgh, Dayton, Indianapolis, Denver, and Chicago. While immigrants made up a significant portion of Chicago’s population growth, hundreds of thousands of newcomers had arrived from the farms and small towns of the Midwest. In addition to those lured by the excitement of the big city, many rural white Protestants were driven off their land by low crop prices, new machinery, and competition from corporate farms They came to Chicago to work in the city’s growing industries and brought with them the educational limits and social insecurities of the decline of rural America. According to historian Geoffrey Perrett, the Klan offered comfort to people who lamented the loss of a way of life that they felt defined America:

And what a sensation they caused on a Friday night in some drab little town when they paraded holding blazing torches. A Klan parade passed by in utter silence, a silence so complete, some claimed, that you could almost hear the breathing of the crowd. What a release this was from the inferiority complex of these grade-school graduates, struggling for a crust in a severe economic recession, forced by an industrialized, urbanized world into daily awareness of their position at the bottom of society. They fastened like the shipwrecked to the one positive attribute they possessed— their old-stock Americanism. In their daft way, they believed that this single virtue qualified them to be guardians of society. Don the flowing robes, converse in the cryptic speech of the Klansman, parade past a crowd awed into silence, and for a while the burning sense of inferiority was gone. A nobody in the world became a somebody in the Klan.

True to the marketing techniques of Clarke and Tyler, the Chicago Klan adapted its message to its constituency. With African Americans comprising only four percent of the city’s population in 1920, the Chicago Klan focused its efforts on capitalizing on Protestants’ fears about the one-million-plus Catholics scattered across the city.

The Chicago Ku Klux Klan began its recruitment drive in earnest in June 1921 with the arrival of Regional Commander C. W. Love from Indianapolis. Setting up shop on Clark Street, Love and his staff of forty-one recruiters worked through the summer to line up prospective Klansmen. Their initial efforts culminated on the evening of August 16, when 2,376 candidates were initiated in a meadow six miles south of suburban Lake Zurich. Headlines in the Chicago Tribune the next day proclaimed, “Ku Klux Rites Draw 12,000.” As a result, Colonel John V. Clinnin of the United States district attorney’s office in Chicago initiated an investigation into the Klan. The Chicago Tribune reported that after months of research, “Clinnin declared that although the organization would foster disorder and anarchy, he could find nothing on which to base legal action.” The Chicago City Council moved as well, unanimously passing the following resolution on September 19:

Whereas the traditions and odium attached to the

Ku Klux Klan and the acts which have been attributable to it make it a menace to a city like Chicago, having a heterogeneous population and different religious creeds; now therefore be it: Resolved, that the city council of Chicago officially condemns the presence of the Ku Klux Klan in Chicago and pledges its services to the proper authorities to rid the community of this organization.

But investigations and resolutions did not have the desired effect, and membership rolls increased dramatically in the following months. Typically, the Klan would only charter one chapter per city or town, but Chicago was eventually able to support more than twenty neighborhood Klan units. Groups were chartered in South Side neighborhoods with rapidly increasing numbers of African American residents, including Englewood, Woodlawn, and Kenwood. Charters were also granted in ethnically diverse areas on the North and West Sides: Irving Park, Logan Square, and Austin. By the summer of 1922, large-scale Klan demonstrations were held both near Joliet and at Ninety-first Street and Harlem Avenue in Chicago.

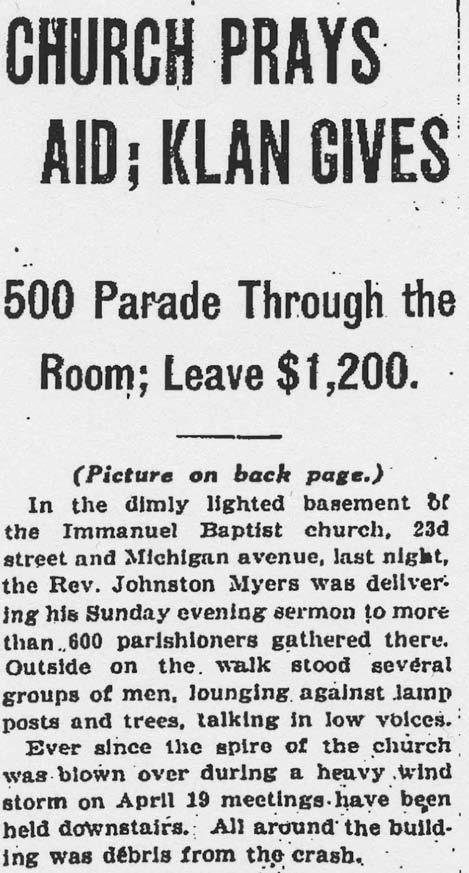

Image enhancement became a priority for the Chicago Klan and church visits a regular activity. Groups of robed Klansman interrupted Protestant church services by walking up the aisle to leave a monetary donation, then departing as quickly as they had arrived. Such visits took place at Douglas Park Christian Church, Pacific

In an attempt to improve its image, the Chicago Klan began ostentatiously interrupting Sunday morning services to give donations to select Protestant churches. Above and below: Newspaper coverage of one such event promoted speculation about the church’s complicity.

Dawn’s common topics included attacks on the rival publication Tolerance and the AUL and promoting the Klan’s anti-Catholic agenda by rallying against the Pope and “his spies.”

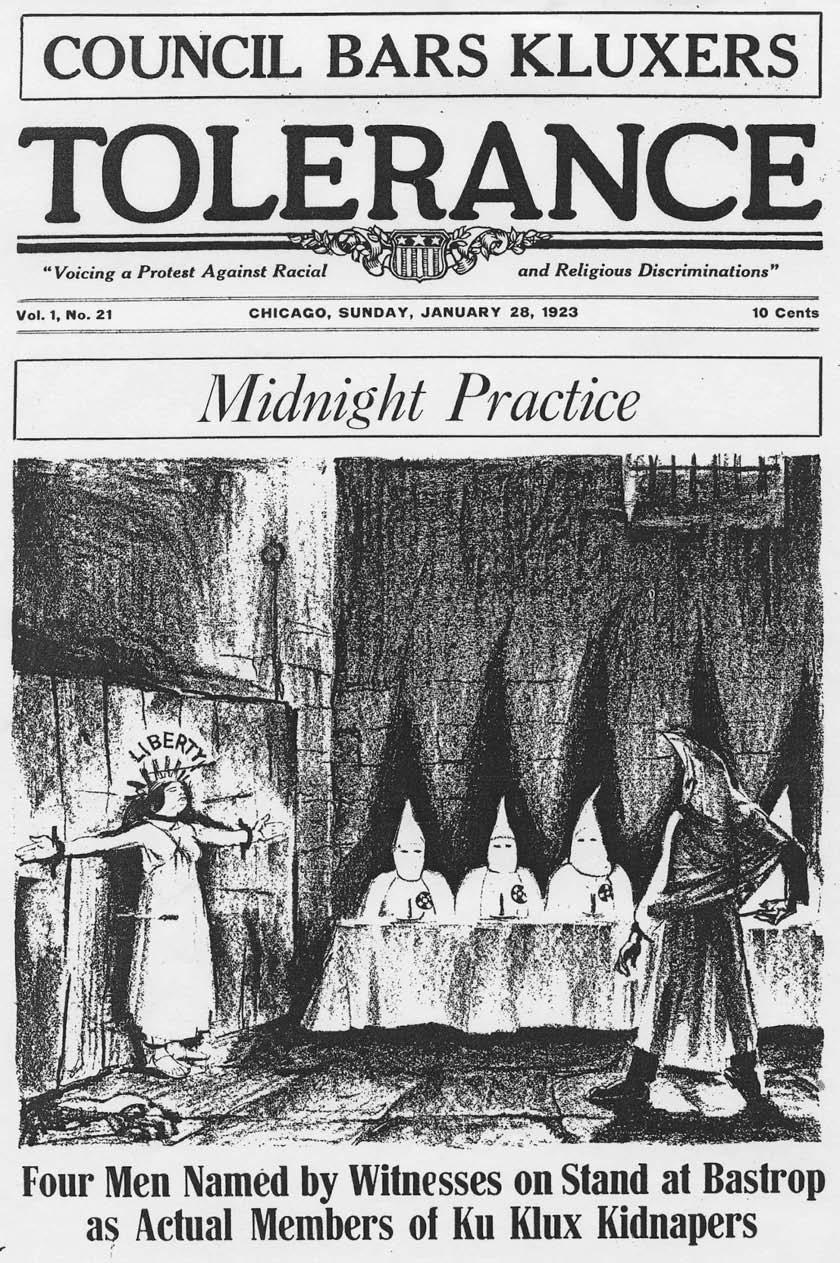

Although the editors of Tolerance criticized Dawn, their main agenda was to discredit and break apart the Chicago Klan. Their most effective, if imperfect, tactic was to publish lists of names reportedly from Klan membership rolls.

Congregational Church, Third Congregational Church, the Southfield Community Church, and the Nazareth Evangelical Church. At Immanuel Baptist Church at Twenty-third Street and Michigan Avenue, about five hundred Klansmen filed past the minister, dropping contributions in a large basket. The presence of a Chicago Tribune photographer, who snapped pictures for the following day’s edition, added to the speculation about the church’s prior complicity.

Klan recruitment even reached the Chicago public schools. Superintendent Peter A. Mortenson ordered an investigation into the practice of Klan members paying Chicago schoolchildren to collect the names and addresses of Protestant classmates’ families. The mothers of the families were then sent circulars, addressed “To Protestant Women of American Birth,” extolling the virtues of the Klan and asking for their help recruiting “gentlemen” members. Mortenson declared that the Klan’s activities were a clear violation of school rules and would not be tolerated. Interestingly, he only took issue with the methods the Klan employed, backing off from a denunciation of the Klan itself. The Chicago Tribune quoted him as saying, “No one is permitted to obtain names and addresses of schoolchildren, except as the roster of graduates appear in the annuals.” Mortenson continued, “I would take the same action against any society or organization. This is not a crusade on my part against the Ku Klux Klan particularly.”

By October of 1922, the Chicago Klan’s imageenhancement plan included the first edition of a weekly publication. Originally published in the Hyde Park neighborhood on the South Side, Dawn extolled the virtues of “100 percent Americanism” and in its first issue made this claim to brotherhood:

Not to advocate the oppression of any people, white or black. Not to malign anyone. Not to foster hatred in any way, but for the purpose of bringing together in whose union all one hundred percent Americans, The Dawn enters the field. Brazenly, as we will be quoted, we announce “our creed” and what could be more glorious than the creed of the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan.

From October 21, 1922, until its final edition of February 9, 1924, Dawn was published weekly, coming out every Saturday at a price of ten cents. With the exception of its somewhat crudely drawn cover, Dawn was a small but professional publication that kept readers informed of Klan-related activities nationally and locally.

In the winter of 1922–23, the Chicago City Council began to investigate Chicago firemen suspected to be members of the Klan. Ultimately, the firemen were relocated or asked to resign.

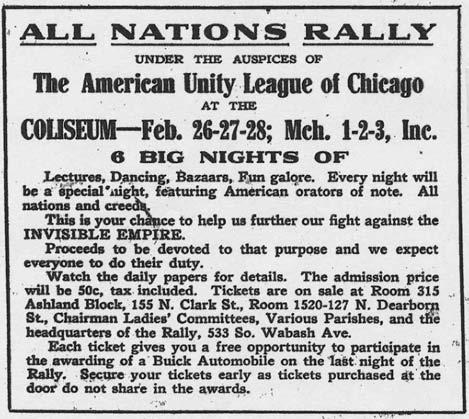

The AUL sponsored a six-day event at the Chicago Coliseum in the spring of 1923. The advertisement in Tolerance (above) stated, “Proceeds to be devoted to [the fight against the Ku Klux Klan] and we expect everyone to do their duty.”

Letters to the editor, editorials, advertisements for local businesses, and classifieds gave the paper a mainstream look. Generally eschewing the overt racism one might expect from a Klan publication, Dawn tended to focus on its anti-Catholic, anti-immigrant theme. In its drive for public acceptance, the Klan of the 1920s portrayed the threat of Catholicism not in religious terms, but political. According to Evans, “The real objection to Romanism in America is not that it is a religion—which is no objection at all—but that it is a church in politics; an organized, disciplined, powerful rival to every political government.” The Chicago Klan attempted to flex its political muscle in response to two legal moves by the city of Chicago and the state of Illinois. The first was the City Council’s investigation of Chicago firemen suspected of being Klansmen. As a result of the investigation, Fire Commissioner John F. Cullerton asked Fire Marshall Arthur F. Seyferlich to force a reputed Klan recruiter to retire and scatter four other firemen to widely separated stations. The reputed recruiter, Fireman George Green, was asked to retire but allowed to keep his pension. The other four were all members of engine company no. 117, stationed at Chicago and Laramie Avenues. Cullerton defended the decision by stating, “Consider the public danger of a situation should firemen refuse to extinguish a blaze because the owner or occupant of a building belongs to a race or creed opposed by a secret order to which they might belong.” The Chicago Tribune reported that two of the transferred firemen were “hit hard” by orders that placed one of them in “the heart of the Ghetto,” engine company no. 6, at 559 South Maxwell Street, and the other “into the center of a Polish district,” hook and ladder company no. 19, at Chicago Avenue and May Street.

Largely as a result of the city council’s actions, Republican State Representative Adelbert H. Roberts of Chicago’s Third District introduced an anti-mask bill in the Illinois Legislature on January 16, 1923. Designed to outlaw public displays by secret societies, the measure became law in the summer of 1923.

Faced with its first serious legal challenges, the Chicago Klan reacted by running or supporting local politicians in the upcoming elections. In the Republican mayoral primary, Arthur M. Millard, a political unknown, finished a surprising third ahead of Municipal Court Judge Bernard P. Barassa. Millard, rumored to be a Klan candidate, garnered 51,054 votes in an almostsecret campaign, offering some indication of the Klan’s strength in Chicago in 1923. The victor in the Republican primary, Arthur C. Lueder, a Lutheran, faced Democrat William E. Dever, a Catholic. Rumors of Klan support for Lueder were fanned by the distribution of anti-Catholic pamphlets throughout the campaign. The Chicago Defender’s endorsement of Dever offset the antiCatholic vote, and Dever’s election by 105,000 votes was interpreted as a decisive defeat for the Chicago Klan. The aldermanic elections saw similar results. Klan-backed candidates in the Eighth, Thirty-seventh, Thirty-ninth, and Fortieth Wards were all soundly defeated.

The American Unity League arose as the greatest opposition to the Chicago Klan. Founded on June 21, 1922, by Robert H. Shepherd, Grady K. Rutledge, and

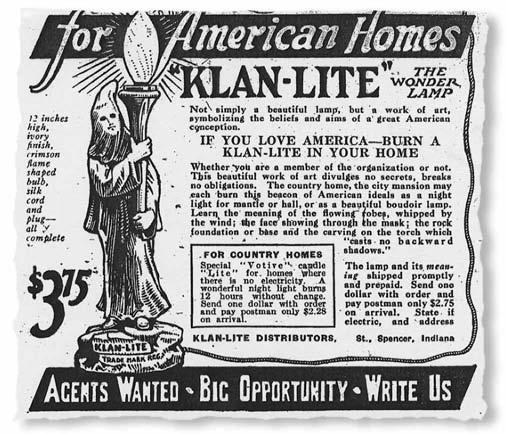

Dawn printed many advertisements for Klan-friendly businesses and products, including the “Klan-Lite,” which was described as a “work of art” and offered for homes with or without electricity.

Joseph G. Keller, the AUL’s sole purpose was the eradication of the Ku Klux Klan. Its main weapon was the weekly newspaper, Tolerance, which was sold at newsstands, bus stops, and Catholic churches for a dime. The two publications, Dawn and Tolerance, became the focus of the ongoing battle over the Klan in Chicago. By 1923, the majority of the editorial space in Dawn was devoted to discrediting its opponent. The intensity of this rivalry resulted in a high-stakes struggle, complete with intrigue, traitors, payoffs, double-crosses, and lawsuits.

The two publications had several similarities. Both were weeklies of similar size and length. Both began publication in the fall of 1922, and neither lasted beyond the middle of the decade: Dawn stopped publication in February 1924, Tolerance lasted until January 1925. Dawn claimed a Chicago circulation of 35,000 and was published more consistently. Tolerance managed to sell 150,000 copies in its heyday, but due to legal problems, was forced to shut down operations for several weeks twice during its short run. Dawn was also able to procure more advertising from local merchants, lawyers, contractors, undertakers, and restaurants. At least initially, scores of local businessmen—especially on the South Side and in the Loop—were eager to advertise in the publication. A local coffee company stressed their “Kuality, Koffee, and Kourtesy” in their ad.

In assessing how best to attack the Klan, the AUL learned well the lessons of the past. Exposing the Klan’s beliefs and tactics was ineffective and counterproductive; their ideals appealed to many Americans, as evidenced by the success of Birth of a Nation and the Klan’s growth after the New York World’s exposé. Instead, the AUL reasoned that the way to bring down the Klan was to expose the members themselves. As Louisiana Governor John Parker told an AUL audience in Chicago, “Tell their neighbors just who these people are who seek to lie hidden while they plot against the community and the nation, and their neighbors will take care of them.”

On September 17, 1922, in its first issue, Tolerance listed the names, addresses, and occupations of 150 Chicago Klansmen. AUL chairman Patrick H. O’Donnell introduced the “visibility campaign” and stated the policy of the newspaper:

We feel that the publication of the names of those who belong to the Klan will be a blow that the masked organization cannot survive. Many Klansmen are in business or the professions and are dependent largely upon patronage of those groups they classify as alien. We feel that it is only just that their attitude be made public.

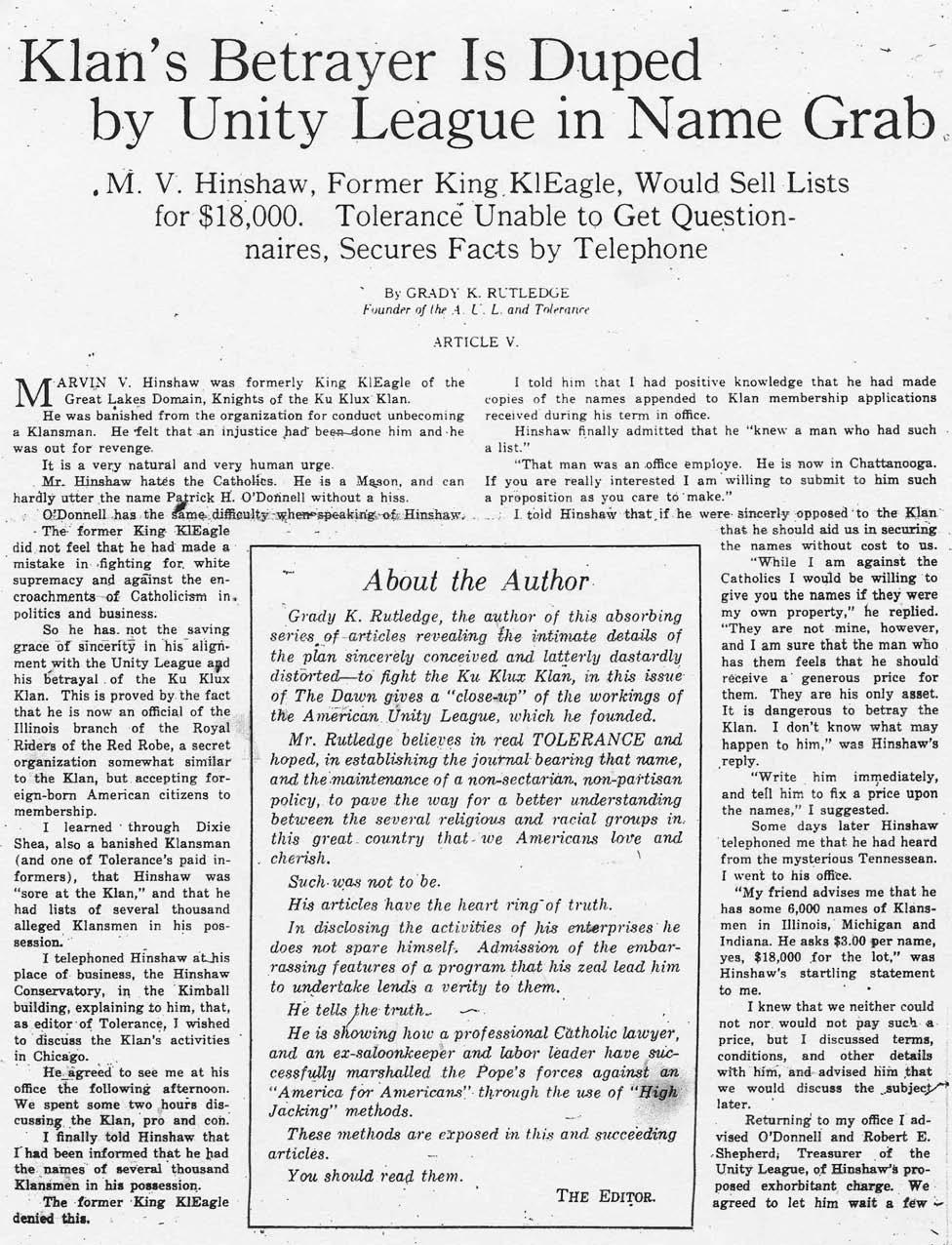

The trick, of course, was gaining access to the names, as Klan membership rolls were a closely guarded secret. The American Unity League employed as many as seven investigators, but the bulk of the names came from former Klansmen. Some had been banished from the Klan, some had left over power struggles, and some were double agents. Dr. Mortimer E. Emrick, who provided the AUL with its first list, was a leader in the Woodlawn Klan who resigned after unsuccessfully attempting to reorganize the South Side chapters. Dixie Shea, W. A. Hill, and Louis D. Wisbrod were all AUL informants who managed to secure positions inside the Klan. The most prolific name supplier, however, was a professional musician named Marvin V. Hinshaw, a former recruiter for the Great Lakes chapter who was banished for “conduct unbecoming a Klansman.” Hinshaw approached the AUL claiming to have a “friend in Chattanooga, Tennessee,” who had a list of six thousand names of Chicago Klansmen for sale at the rate of three dollars per name or $18,000. Hinshaw rejected the AUL’s initial counteroffer of $600. When the offer was raised to $2,500, Hinshaw showed up at AUL headquarters at 127 North Dearborn with the names. Lulled into a false sense of security by an impressive stack of cash on the table, Hinshaw gave the names to Grady Rutledge, editor of Tolerance and secretary of the AUL. Rutledge excused himself to another room to supposedly compare the list with others acquired by the AUL. Sprinting out a back door, Rutledge dashed through the Loop to the law offices of Patrick O’Donnell at Clark and Randolph Streets, where the list was locked in a secret vault. Hinshaw’s payout turned out to be less than $350.

Attorney Patrick H. O’Donnell, pictured here in 1908, became the chairman of the AUL.

Grady Rutledge’s articles in Dawn included a first-hand account of the “real” story behind the selling of Klansman’s names to Tolerance.

By January 1923, Tolerance had printed the names of four thousand Chicago Klansmen and was prepared to print six thousand more. It is impossible to determine exactly how many Klansmen renounced their memberships as a result of the listings, but evidence suggests the number was substantial. Several small businessmen testified in court that their businesses suffered as a result of being exposed by Tolerance. The president of the Washington Park National Bank was listed in the fifth issue of Tolerance, and by the time the bank’s board of directors convinced him to step down, the bank had lost thousands of dollars in withdrawals. “I signed a petition for membership in the Klan several months ago,” the bank president lamented. “But I did not know it was anything else than an ordinary fraternal order.” The most telling evidence of the effectiveness of Tolerance’s visibility campaign was the Klan’s reaction to it. Blasting the group’s methods as a “miserable weapon of cowards,” the Klan sued the AUL for revealing its secrets and temporarily succeeded in stopping the publication of Tolerance.

Printing Klan membership rosters proved to be a mixed blessing for the AUL. Undeniably effective as a tool for reducing the ranks of the Chicago Klan, the visibility campaign inevitably included inaccurate listings. Some names were originally forged by Klan recruiters to artificially bolster their recruiting numbers and others were listed by the informants out of spite. The careers of several apparently innocent people were harmed, and the American Unity League itself was irreparably damaged by dissension and lawsuits as a result of printing erroneous names.

A plumber and a physician each sued the AUL for $25,000, and J. William Brooks, an attorney with an undertaking business, filed a $100,000-slander suit. Brooks claimed that as a result of his name being published “practically all his clients had deserted him, members of his parish church avoided him, and the undertaking business was ruined.”

William Wrigley Jr., millionaire gum manufacturer and owner of the Chicago Cubs, filed the most damaging of the suits against the AUL. Tolerance had gained possession of a Klan application in Wrigley’s name with his signature apparently on it. After the editors published his name, Wrigley filed a $50,000 lawsuit against the American Unity League and offered another $50,000 to charity in the name of anyone who could prove he had signed a membership application for the Klan. The signature, which resembled the fictional signature printed on the wrapper of Wrigley chewing gum but bore no likeness to his actual signature, was described by the gum manufacturer as “a rank forgery and about as much like mine as the north pole [is] like Vesuvius.” Eventually, the Klansman who claimed to have taken Wrigley’s application admitted it was a forgery.

The demise of the AUL began when the editors incorrectly published William Wrigley Jr.’s name as part of their visibility campaign. The action initiated a serious lawsuit and caused dissent among AUL founders, which ultimately led to Rutledge leaving the organization.

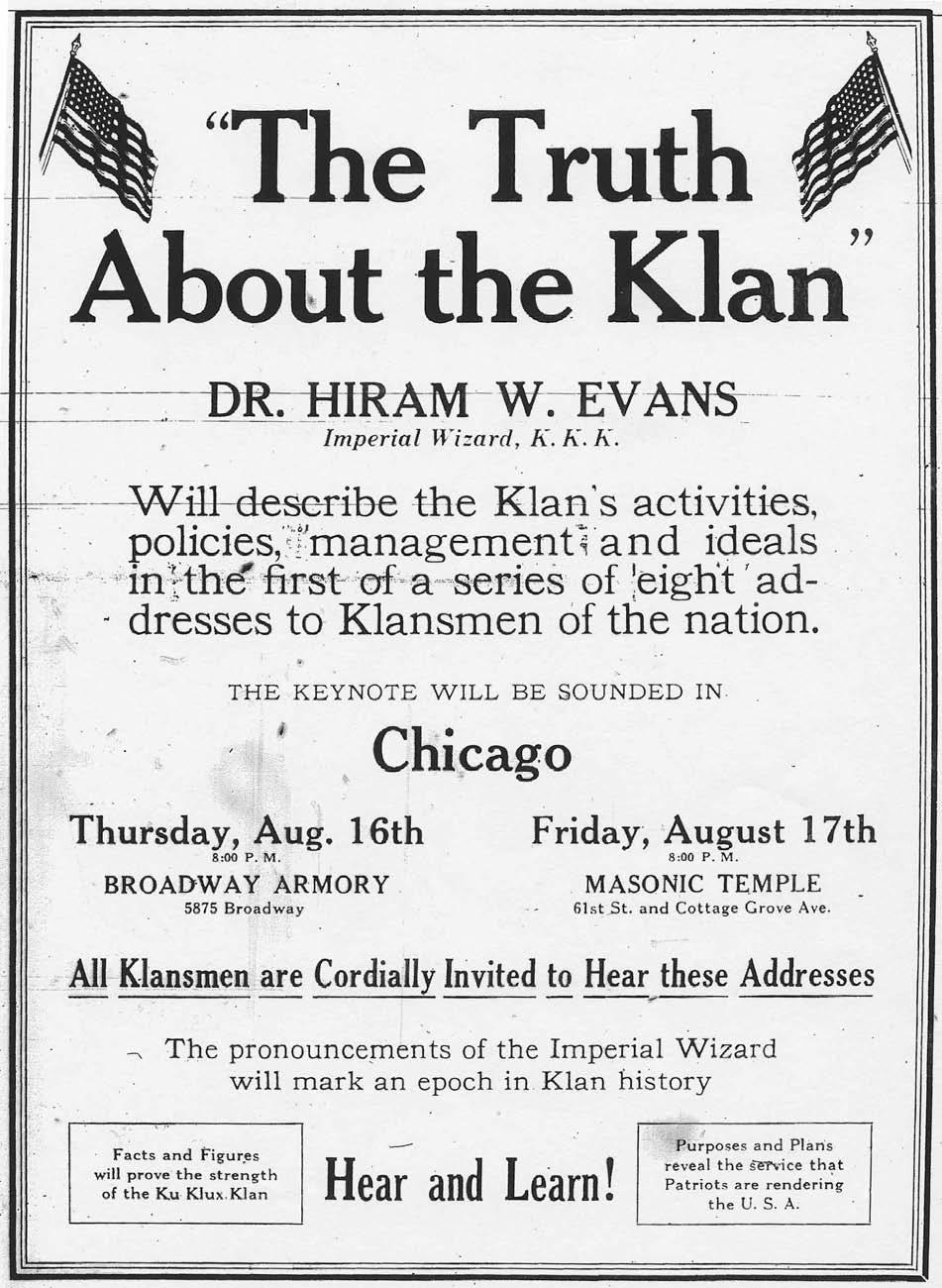

Dr. Hiram Evans came to Illinois in 1923 in an attempt to reunite and restructure the Chicago Klan. His visit was advertised in Dawn.

As local Klan membership declined, the intensity of the content published in Dawn increased. Printed in October 1923, this cartoon ran below the headline, “The ‘Man on the Fence’ Becomes Uncomfortable,” and urged the indecisive to join the powerful members of the Klan.

Grady Rutledge later charged that AUL chairman Patrick O’Donnell was behind the Wrigley scheme from the start. Rutledge claimed that soon after Tolerance began publishing names, O’Donnell instructed him and treasurer Robert Shepherd to “get the goods” on Wrigley, stating that he was sure Wrigley was a member of the Klan. Rutledge contacted his usual informants but could not find evidence linking Wrigley to the Klan. Several weeks later, after returning from out of town, Rutledge discovered that Shepherd had secured an application to the Klan in Wrigley’s name. Rutledge found this unusual for several reasons. “Of all the names published in Tolerance while I was editor, that of William Wrigley, Jr. was the only one that came through a separate source,” he said. “It was the only name I ever knew of coming to us singly. And it was the only name that we ever had that was backed up by an original questionnaire—forged or otherwise.” When O’Donnell and Shepherd published Wrigley’s name over Rutledge’s objections, he secured an injunction restraining O’Donnell and Shepherd from interfering with the publication. When O’Donnell and Shepherd won the ensuing legal battle, Rutledge left the AUL and defected to the Klan.

Rutledge’s surprising about-face was comprehensive. He not only joined the Klan; he became the featured writer for Dawn for the remainder of the newspaper’s run. Rutledge’s articles exposing the inner workings of the AUL and Tolerance became the centerpieces of the newspaper. In the articles, Rutledge lambasted his former colleagues. He maintained that the organization’s membership was grossly exaggerated and alleged, “Tolerance editors have no evidence of Klan membership against nine out of ten men whose names they publish.” The disgruntled founder of the AUL went as far as to suggest, “Anyone wishing to contribute his hard earned money to finance O’Donnell, Shepherd, et al. in their effort to unite Catholics, Jews, Negroes and foreigners in a fight with White, Gentile, Native, Protestant Americans for the control of our country should send his contribution to the Pope’s branch office, AUL headquarters, 127 N. Dearborn Street, Chicago.”

By late 1923, internal dissension and the AUL’s visibility campaign began to take their toll on the Chicago Klan. On the national level, founder William Simmons had been duped into accepting a ceremonial position. Meeting in Atlanta, Klan leaders turned control over to Dallas dentist Hiram W. Evans. By the time Simmons discovered the ruse, it was too late. The group adopted changes that stripped him of any real power and sold land he had set aside for building a university. Incensed, Simmons decided to form a women’s Klan. He took control of the White

Disagreement among the AUL eventually made headlines as the editors went to court to determine the future of the organization.

In an effort to strengthen the organization and encourage new members, the Klan held an afternoon festival in the fall of 1923. Advertisements announced that all “eligible” friends and families were welcome.

American Protestant Study Club of Oklahoma, changed its name to Kamelia, and called it the official ladies’ auxiliary of the Ku Klux Klan. Simmons’s failed attempt to regain control resulted in a tangle of lawsuits, which eventually sent him into quiet retirement and solidified Evans’s hold over the Klan.

In Chicago, the national power struggle created local dissension. Simmons visited in July 1923 and was able to corral the loyalty of four of the city’s largest and most influential chapters. Evans immediately suspended the charters of the four groups and came to Chicago in August to try to quell the schism by urging all members to adhere to the duly constituted authorities in Atlanta. Despite the loyal support of Illinois leader Charles Palmer, the Chicago chapters remained deeply divided. In November 1923, Palmer dismissed the presidents of ten Chicago chapters; the following year, he banished fourteen thousand Illinois members for disloyalty. The upheaval caused the national office to replace Palmer by the end of 1924. By then the Chicago Klan was in disarray and the end was near. Dawn had ceased publication in February 1924, and in May, all twenty-six Chicago chapters had merged into one unit, none of them retaining enough members to operate on their own.

The Ku Klux Klan’s emergence in Chicago in the 1920s involved a significant number of people for a short period of time. As part of a nationwide resurgence of the Klan, the Chicago movement drew headlines more for the threat it posed than for any particularly newsworthy events. The most significant aspect of the rise of the Ku Klux Klan in Chicago in the 1920s is the relative insignificance with which it was perceived at the time. Racism and bigotry were so much a part of many people’s lives that the resurgence of the Klan did not inspire the kind of revulsion and indignation that would be expected in modern society. In many ways, and to many people, the Ku Klux Klan was just another fraternal organization.

Chicagoans joined the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s by the thousands because they believed in its message of white, Protestant supremacy. Thousands left the Klan when their identities were revealed to their Catholic, Jewish, and African American neighbors, who then refused to do business with them. The remainder left when it became apparent that the organization was unable to prevent the changes occurring in society. Evidence of Klan activity was sporadically reported in Chicago in 1925 and 1926, but for all practical purposes, the Chicago Klan was dead.

David Craine teaches American history at St. Patrick High School in Chicago. He is a graduate history student at Northeastern Illinois University. Throughout the early 1920s, the Chicago Klan continued to target Catholics and immigrants as well as corrupt politicians and criminals.

ILLUSTRATIONS | 4, courtesy of the Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-64768; 5, reprinted from Dawn, 10 Feb. 1923; 6 left, reprinted from the Chicago Tribune, 19 Sept. 1915; 6 right, reprinted from the Chicago Tribune, 1 Oct. 1922; 7, reprinted from Dawn, 5 Jan. 1924; 8, courtesy of the Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-104018; 9 top, Chicago History Museum Daily News collection, DN-0074501; 9 bottom, reprinted from Dawn, 8 Dec. 1923; 10, reprinted from Dawn; 11, map from Kenneth T. Jackson’s The Ku Klux Klan in the City, 1915–1930, 1st ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1967); 12, reprinted from the Chicago Tribune, 17 Aug. 1921; 13, reprinted from the Chicago Tribune, 21 Aug. 1922; 14, cover of Dawn, 21 April 1923; 15, cover of Tolerance, 28 Jan. 1923; 16, reprinted from the Chicago Tribune, 31 Jan. 1922; 17 top, reprinted from Tolerance, 28 Jan. 1923; 17 bottom, reprinted from Dawn; 18, Chicago History Museum Daily News collection, DN-0005776; 19, reprinted from Dawn; 20, reprinted from the Chicago Tribune, 4 Feb. 1923; 21, reprinted from Dawn; 22, reprinted from Dawn, 13 Oct. 1923; 23, reprinted from the Chicago Tribune, 3 Feb. 1923; 24, reprinted from Dawn; 25, reprinted from Dawn, 11 Nov. 1922.

FOR FURTHER READING | Kenneth T. Jackson’s The Ku Klux Klan in the City, 1915–1930, 2nd ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1967; Chicago: I.R. Dee, 1992) is a comprehensive look at the nationwide Klan movement in the early twentieth century. Additional texts of interest include David Mark Chalmers’s Hooded Americanism: The History of the Ku Klux Klan, 3rd ed. (1981; repr., Durham: Duke University Press, 1987) and Kathleen M. Blee’s Women of the Klan: Racism and Gender in the 1920s (Berkeley: University of California Press,