The Klan Moves North In the 1920s, the Ku Klux Klan emerged in Chicago to fight the perceived dangers of urban life. DAV I D C R A I N E

F

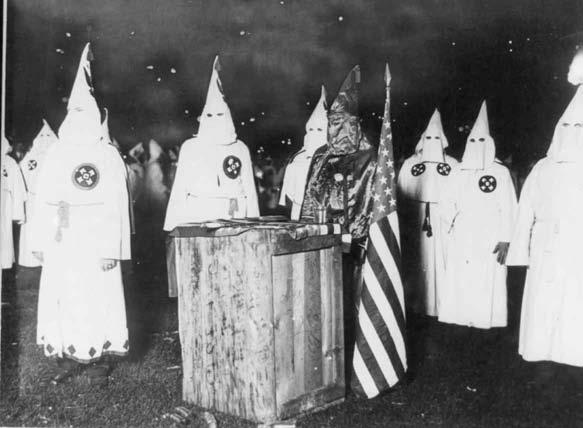

Leaders preside over a meeting of thousands of Klansmen from Chicago and northern Illinois, c. 1920.

4 | Chicago History | Fall 2006

rom 1921 to 1925, Chicago became embroiled in a controversy that many associated with the South. As part of a nationwide movement, the Invisible Empire of the Ku Klux Klan established itself in the city and within a year attracted thousands of adherents. Preaching “100 percent Americanism” and white Protestant supremacy, the Chicago Klan found fertile ground for its ideals of bigotry. Unlike its Reconstruction-era predecessor, the Klan of the 1920s tailored its message of hate to each territory it invaded. In Chicago, the message preyed predominantly on the insecurities and fears of Protestants against Catholics. For four years, the Klan flourished, publishing a weekly newspaper and holding meetings, social events, and recruitment drives. In response, a small group founded the American Unity League (AUL), devoted to the eradication of the Klan in the city and across the country. Publishing its own newspaper, the AUL made significant inroads in their mission against the Klan. But, after an intense four-year battle, the Chicago Klan and its detractors disappeared, all but forgotten to memory and history. Led by Colonel William Joseph Simmons, the revival of the Ku Klux Klan occurred atop Stone Mountain in Georgia in November 1915, two weeks before the Atlanta opening of D. W. Griffith’s cinematic homage to the Klan of the Reconstruction era, Birth of a Nation. The original Klan was founded as a Southern, rural, antiblack movement after the Civil War. The group’s reemergence in the early twentieth century was a reaction to societal changes of a different nature.