CHICAGO HISTORY

S P R I N G 2 0 2 2

This issue of Chicago Histor y is dedicated to the memor y of T I M U E L D . B L A C K J R . (December 7, 1918–October 13, 2021)

Vice President of Marketing and Communications

Thema McDonald

Editors

Heidi A. Samuelson

Esther D Wang

Designer

Bill Van Nimwegen

Photography

Timothy Paton Jr

O F F I C E R S

Daniel S. Jaffee

Chair

Mar y Lou Gorno

First Vice Chair

Warren K Chapman

Second Vice Chair

Mark D Trembacki

Treasurer

Denise R . Cade Secretar y

Donald E L assere

Edgar D. and Deborah R. Jannotta President

H O N O R A R Y T R U S T E E

The Honorable

Lori Lightfoot

Mayor, City of Chicago

Copyright © 2022 by the Chicago Historical Society

Clark Street at North Avenue

Chicago, IL 60614-6038

312 642 4600

chicagohistor y org

ISSN 0272-8540

Articles appearing in this journal are abstracted and indexed in Historical Abstracts and America: Histor y and Life

T R U S T E E S

James L Alexander

Denise R Cade

Paul Carlisle

Walter C Carlson

Warren K Chapman

Rita S. Cook

Patrick F Daly

James P Duff A Gabriel Esteban

L afayette J Ford

T Bondurant French

Alejandra Garza

Timothy J. Gilfoyle

Gregor y L Goldner

Mar y Lou Gorno

David A. Gupta

Brad J Henderson

David D Hiller

Tobin E Hopkins

Daniel S Jaffee

Ronald G K aminski

R andye A Kogan

Judith H. Konen

Michael J Kupetis

Donald E L assere

Robert C Lee

R alph G Moore

Maggie M Morgan

Stephen R ay

Joseph Seliga

Steve Solomon

Samuel J Tinaglia

Mark D Trembacki

Ali Velshi

Gail D Ward

L awrie B Weed

Monica M Weed

Jeffrey W Yingling

Robert R . Yohanan

H O N O R A R Y L I F E T R U S T E E

The Honorable

Richard M. Daley

The Honorable R ahm Emanuel

L I F E T R U S T E E S

David P Bolger

L aurence O Booth

Stanley J Calderon

John W. Croghan

Patrick W Dolan

Paul H Dykstra

Michael H Ebner

Sallie L Gaines

Barbara A Hamel

M Hill Hammock

Susan S Higinbotham

Dennis H Holtschneider C M

Henr y W. Howell, Jr.

Edgar D Jannotta

Falona Joy

Barbara L Kipper

W. Paul Krauss

Josephine Louis

R Eden Martin

Josephine Baskin Minow

Timothy P Moen

Potter Palmer

John W Rowe

Jesse H Ruiz

Gordon I Segal

L arr y Selander

Paul L Snyder

T R U S T E E S E M E R I T U S

Catherine L Arias

Bradford L Ballast

Gregor y J Besio

Michelle W Bibergal

Matthew Blakely

Paul J Carbone, Jr

Jonathan F Fanton

Cynthia Greenleaf

Courtney W Hopkins

Cher yl L Hyman

Nena Ivon

Douglas M Levy

Erica C Meyer

Michael A Nemeroff

Ebrahim S Patel

M Bridget Reidy

James R Reynolds, Jr

Elizabeth D Richter

Nancy K Robinson

April T. Schink

Jeff Semenchuk

Kristin Noelle Smith

Margaret Snorf

Sarah D Sprowl

Noren W Ungaretti

Joan Werhane

*As of June 30, 2021

The Chicago Histor y Museum acknowledges support from the Chicago Park District and the Illinois Arts Council Agency on behalf of the people of Chicago

C H I C A G O H I S T O R Y

C H I C A G O H I S T O R I C A L S O C I E T Y

Cover: Timuel Black outside the One East Erie building in Chicago's River North neighborhood Courtesy of Bart Schultz.

C O N T E N T S 4 Remembering Timuel D. Black Jr. T R I B U T E 20 The Presentation — St. Joseph Twinning and Sharing Relationship in the 1970s K E V I N R YA N 30 The Good Communists and the Chicago Health Movement of the 1970s: A Speculative Retrospective J U D I T H K E G A N G A R D I N E R D E PA R T M E N T S 40 Making History T I M O T H Y J . G I L F O Y L E T H E M A G A Z I N E O F T H E C H I C A G O H I S T O R Y M U S E U M • V O L U M E X LV I , N U M B E R 1 CHICAGO HISTORY S P R I N G 2 0 2 2

Remembering Timuel D. Black Jr.

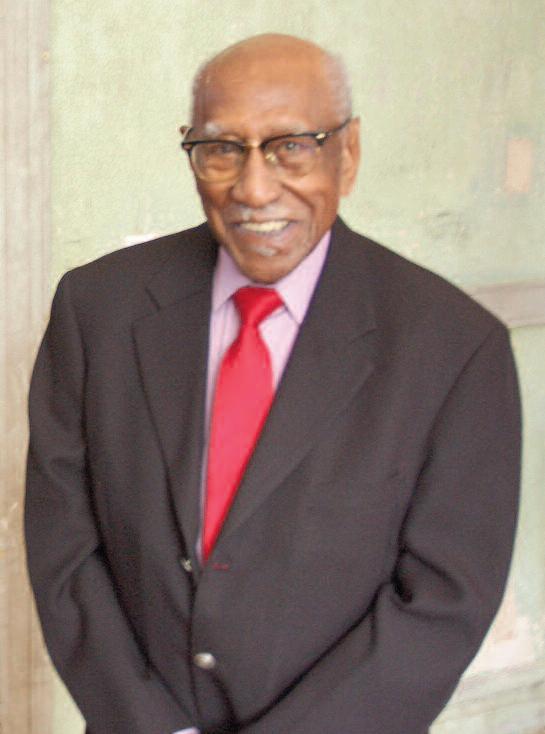

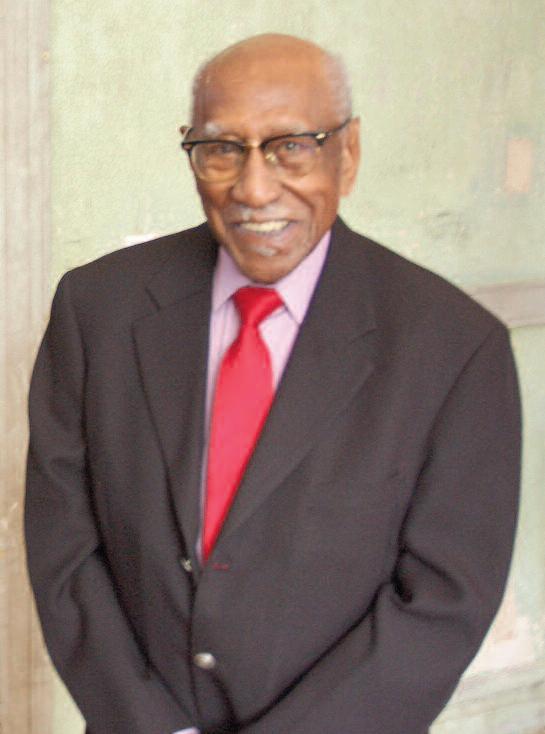

Last year, noted Chicago historian, teacher, mentor, author, and civil rights leader Timuel D Black Jr died at the age of 102 A friend to the Chicago Histor y Museum, Black received our prestigious John Hope Franklin Making Histor y Award for Distinction in Historical Scholarship in 2006, named after its first recipient, Dr. John Hope Franklin, and an honor shared with William Cronon, Garr y Wills, and Robert V Remini He was recognized, in part, for his two volume Bridges of Memor y publication, one of the most ambitious oral histor y projects on the histor y of Chicago, featuring his conversations with Black Americans who migrated to Chicago from the South in search of economic, social, and cultural opportunities

We invited some of those who knew Tim as he was called by many to share their memories and the impact he had on their work and life.

4 | CHICAGO HISTORY | Spring 2022

Timuel Black, photographed in Chicago on July 13, 1978

Eve L. Ewing

Author (Maya and the Robot, 1919, Ghosts in the Schoolyard: R acism and School Closings on Chicago’s South Side, Electric Arches) Assistant Professor, the University of Chicago

When it was time for me to do a school project about the Great Migration, my mother told me I had to talk to two people: my grandmother and Timuel Black In retrospect, it makes me giggle t h a t o n e o f t h e n a t i o n ’ s f o r e m o s t experts on the subject should be presumed to be available to assist in a middle school histor y project. But for those who knew Tim, it will come as no surprise that he took the time Looking back, with that encounter, I am pretty sure he became the first Black scholar I ever interacted with in my life I am awed to think of all the moments, all the blossomings, all the blessings that were made possible with that one quiet insight: there are Black folks who read and write books to make their living, who make it their business to be seekers and keepers of our stories, to find threads of meaning and patterns and, yes, histor y in the helter skelter of ever yday life And moreover, that it’s not only possible but fully necessar y that if you want to be one of those folks, part of your job is to stick around your people and to keep that magic in plain sight. In over a centur y, how many people bloomed through that moment of recognition with Tim? I weep to think of it I weep with joy, and with gratitude

Robert Hanserd, PhD

Associate Professor of African, Atlantic, and African American Histor y Columbia College Chicago

I will always remember the first time I met Timuel Black. Some twenty years ago, I was a graduate student intern at the Chicago Historical Society, now Chicago Histor y Museum (CHM) I worked on the Neighborhoods: Keepers of Culture exhibit that displayed artifacts and archival materials collected from Chicago’s diverse communities. As part of the internship, I visited the CHM librar y and read extensively on the life of historical figures in Chicago, including Timuel Black I can remember how absorbed I was in the research into his life Apparently, I was a little too excited CHM invited Emeritus Professor Christopher Reed, a treasure trove of Chicago histor y in his own right, to join the exhibition team, and he introduced me to Timuel Black Walking down Wabash near Congress on a warm afternoon, L trains moving noisily above, I was gushing to Reed about my knowledge of Timuel

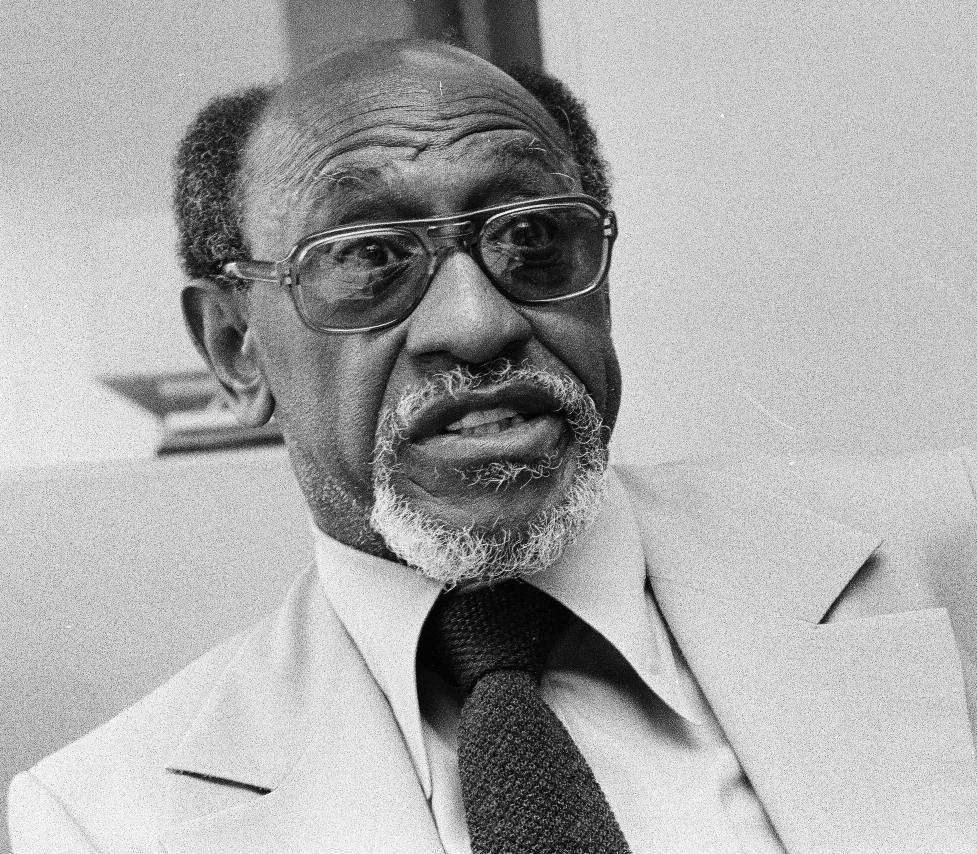

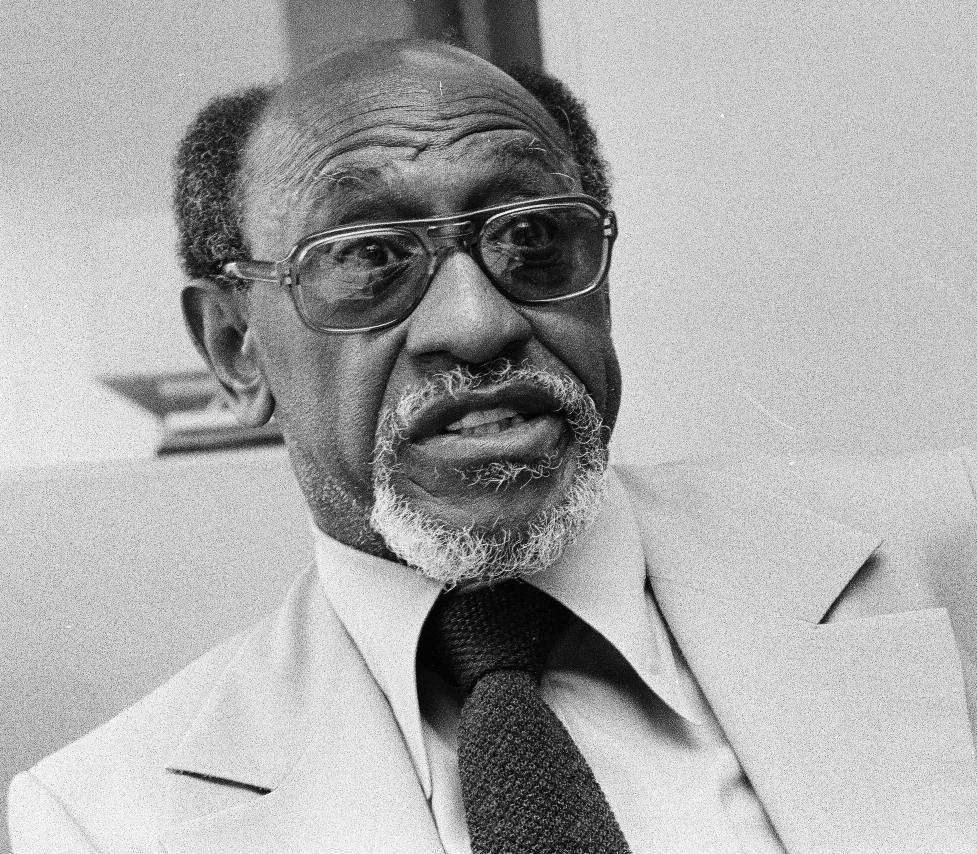

( F r o m l e f t ) : Z e n o b i a J o h n s o n - B l a c k , Timuel Black, and Eve Ewing on December 8, 2018, at “ The Life and Times of Timuel D. Black: A Centenar y Symposium” hosted by the University of Chicago

Timuel D. Black Jr. | 5

Black, filling the space between trains’ sounds with his stor y. Then, to my surprise, we saw Timuel Black walking up the street in our direction The first thing Professor Reed said when we met was: “ This boy here says he’s your cousin ” They both laughed heartily, and I finally did also As we discussed our efforts on the exhibition, I got to see the personhood and demeanor of the man who encouraged me to continue to study histor y From that moment until the last time I saw him (at a South Side restaurant taking time to work with a student from Indiana University), he always greeted me warmly. Thousands of miles from Chicago, I write this reflection from West Africa, Ghana Despite the distance, I feel gratitude to Timuel Black, whose example of living histor y motivated my own efforts to bring historical knowledge and social justice to communities in Chicago and beyond.

Rick Kogan Chicago newspaperman and author

On the night of March 4, the birthday of the city, in 2008, Tim Black and I walked into the Congress Room on the second floor of Roosevelt University We were playing a small part in the six-month-long series of free public programs celebrating Harold Washington, who Tim might have known as well as anyone, since this was where they attended college, first met one another, and shared dreams of social equality and justice

Tim and I walked into an almost empty room

“Do you think any more people will be coming?” he asked.

“Of course, ” I told him

The Harold Washington Commemorative Year, the Illinois nonprofit corporation that created the programming series, had done a fine job of promoting its events But when we started talking there were no more than a dozen people listening

What a shame I asked questions and Tim provided answers, which engagingly took the form of l o n g s t o r i e s , c r a m m e d w i t h humor, insight and detail, and not a whiff of self-importance. He told of the weekly poker games with Washington and others so evocatively that I would have eagerly sat in, even if it meant losing ever y hand, and he did not talk about himself, his years as a social worker, high school and college teacher, union organizer, and community political activist. He did not even mention his Bridges of Memor y books compelling oral histories of the African American experience in Chicago

Tim was nearing 90 then, and he said, “I have lived a lot of the city’s histor y

Histor y is, of course, available by many means and in many forms But histor y delivered firsthand is a rare commodity and it packs a punch that dazzles more than the flashiest website

The next time you have the opportunity to hear about histor y from a living link, do that. Do that in honor of Tim.

”

6 | CHICAGO HISTORY | Spring 2022 B l a c k ( r i g h t ) w i t h L o r e n z o Yo u n g , a B r o n z e v i l l e a c t i v i s t e d u c a t o r, o n D r exe l B o u l e v a r d a f t e r a U n i v e r s i t y o f C h i c a g o panel on the Red Summer of 1919

Tracye A. Matthews, PhD Executive Director Center for the Study of R ace, Politics, and

In some ways, Tim was Chicago to me.

Culture at the University of Chicago

I was still in graduate school and beginning to write my dissertation when I moved to Chicago and got my ver y first “ real” job at the Chicago Historical Society (now the Chicago Histor y Museum) That’s when I first met Timuel Black. It was 1994. I had just been hired by the Museum to coordinate their 1990s-era, groundbreaking initiative, Neighborhoods: Keepers of Culture The project was designed as a series of collaborations with diverse communities to create exhibitions, youth-produced video oral histories, and public programs to be launched at the Museum and then travel to those neighborhoods. The idea was to identify and connect with the culture-keepers in communities, who held the knowledge and lived experiences that would help to tell a different and more complete histor y of Chicago than what is usually told

Tim offered me his trust; he vouched for me in our first neighborhood, Bronzeville, a community I hardly knew, a community suspicious of the sudden and unprecedented attention of the city ’ s histor y museum In my mind, the task at hand was akin to community organizing And I was discovering what Tim already knew, that if you wanted to understand the Black experience in America you had to know Bronzeville

We spent months planning and preparing for community engagement at a level not previously experienced by most of our team We were studying secondar y sources, participating in antiracism training, and honing oral histor y collecting techniques, but it was Tim’s introduction that made the work possible Tim held the keys to Bronzeville He let us in and encouraged the residents to trust us, all of us. And it was remark able.

B

b

b y t h e B r o n z e v i l l e M e r c h a n t s A s s o c i a t i o n on September 24, 2009.

Timuel D. Black Jr. | 7

Ti m u e l B l a c k t a l k s a b o u t t h e h i s t o r y o f

r o n z e v i l l e d u r i n g t h e u n v e i l i n g o f t w o

r o n z e o b e l i s k s a t 3 5 t h a n d S t a t e S t r e e t s

The approach to community engagement begun with Neighborhoods: Keepers of Culture still guides the work of the Chicago Histor y Museum nearly thirty years later As many have observed, Tim was generous with his time, his ideas, and his stories As both a public intellectual and a scholar activist, he understood that stories could change lives. He knew that knowledge production wasn’t the exclusive domain of the academy or the museum And he understood that the memories of regular, ever yday, extraordinar y people held the secrets of the past and the promise of the future.

Marcia Walker-McWilliams, PhD Executive Director - Black Metropolis Research Consortium University of Chicago Librar y

I’ll never forget my first time meeting Timuel Black in Januar y 2010 Tim had agreed to my request to interview him about his friend and fellow Chicago labor activist, Reverend Addie Wyatt I was working on a dissertation about Addie Wyatt, and ever yone kept urging me to connect with Tim Black. I was nervous to interview Tim given his immense knowledge of the city and its Black histor y I had just finished reading Bridges of Memor y and worried that my own interviewing and oral histor y skills would fall woefully short of Tim’s expectations Recorder and questions in hand, I arrived at Tim’s door ready to conduct the interview at his home, as I had done with other interviewees But Tim had other plans He met me at his door wearing his coat and hat In his direct way, he let me know that he was hungr y, and we were going to lunch at a local Hyde Park diner, Salonica I knew then that this was not going to be a traditional interview

Tim was intent on sharing his stor y, and, on the fly, I had to learn how to weave my questions into his narrative. I scribbled notes as he shared what it was like to attend DuSable High School in Chicago in the late 1930s when I asked if he and Addie were classmates I learned that the formation of the Chicago chapter of the Negro American L abor Council in the early 1960s was a turning point for Black labor activists like Black and Wyatt. In amazing detail, Tim shared what it was like to march in Marquette Park during the Chicago Freedom Movement and how he watched Addie Wyatt continue marching after her car was destroyed and set on fire by a white mob With

R e v D r M a r t i n L u t h e r K i n g J r s i t s w i t h James Bevel, Al R aby, Andrew Young, and others at a press conference in the Sahara I n n , S c h i l l e r Pa r k , I l l i n o i s , w h e r e K i n g announces plans for the Chicago Freedom Movement on Januar y 11, 1966

8 | CHICAGO HISTORY | Spring 2022

stor y after stor y, Tim provided insight and a perspective that I would not find anywhere else More than six decades separated us in age, but it was I who had to keep up with him that day.

I am so grateful that Tim was generous with his time, his sense of humor, and his stor y. On several other occasions at a meeting of retired Black labor activists, at a program on Black political activism in Chicago, and at a m e e t i n g o f t h e V i v i a n G . H a r s h Society I heard Tim tell more of his stor y Tim ensured that others would benefit from his knowledge by donating his personal papers to institutions like the Chicago Histor y Museum and t h e C h i c a g o P u b l i c L i b r a r y Researchers and historians like myself a r e g r a t e f u l f o r h i s f o r e s i g h t . H i s papers are a treasure trove of information for those seeking to learn more about his life as well as the vast organizations, networks, and movements that shaped Chicago’s histor y all from the vantage point of one of its most active and engaged citizens

Bart Schultz, PhD Director of the Civic Knowledge Project Senior Lecturer in the Humanities The University of Chicago

Bart Schultz, PhD Director of the Civic Knowledge Project Senior Lecturer in the Humanities The University of Chicago

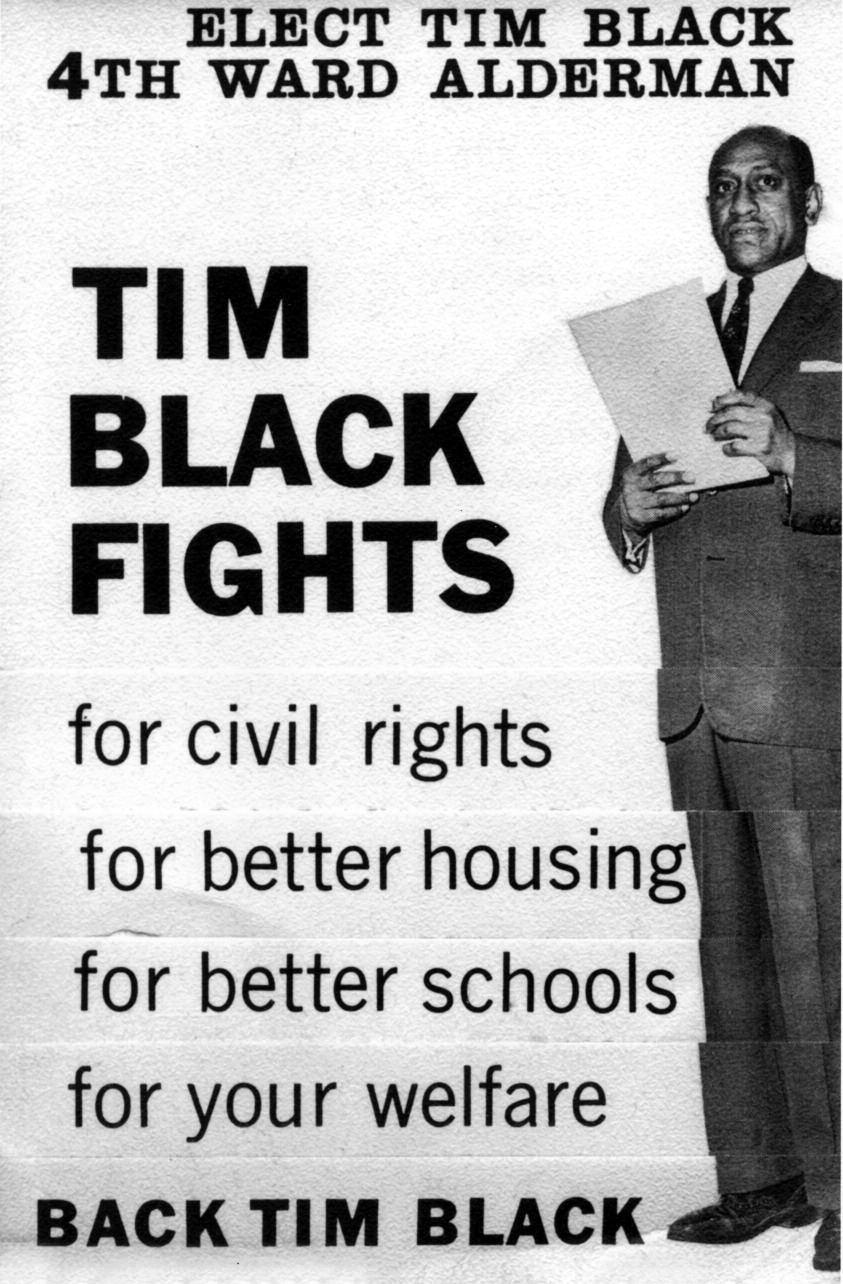

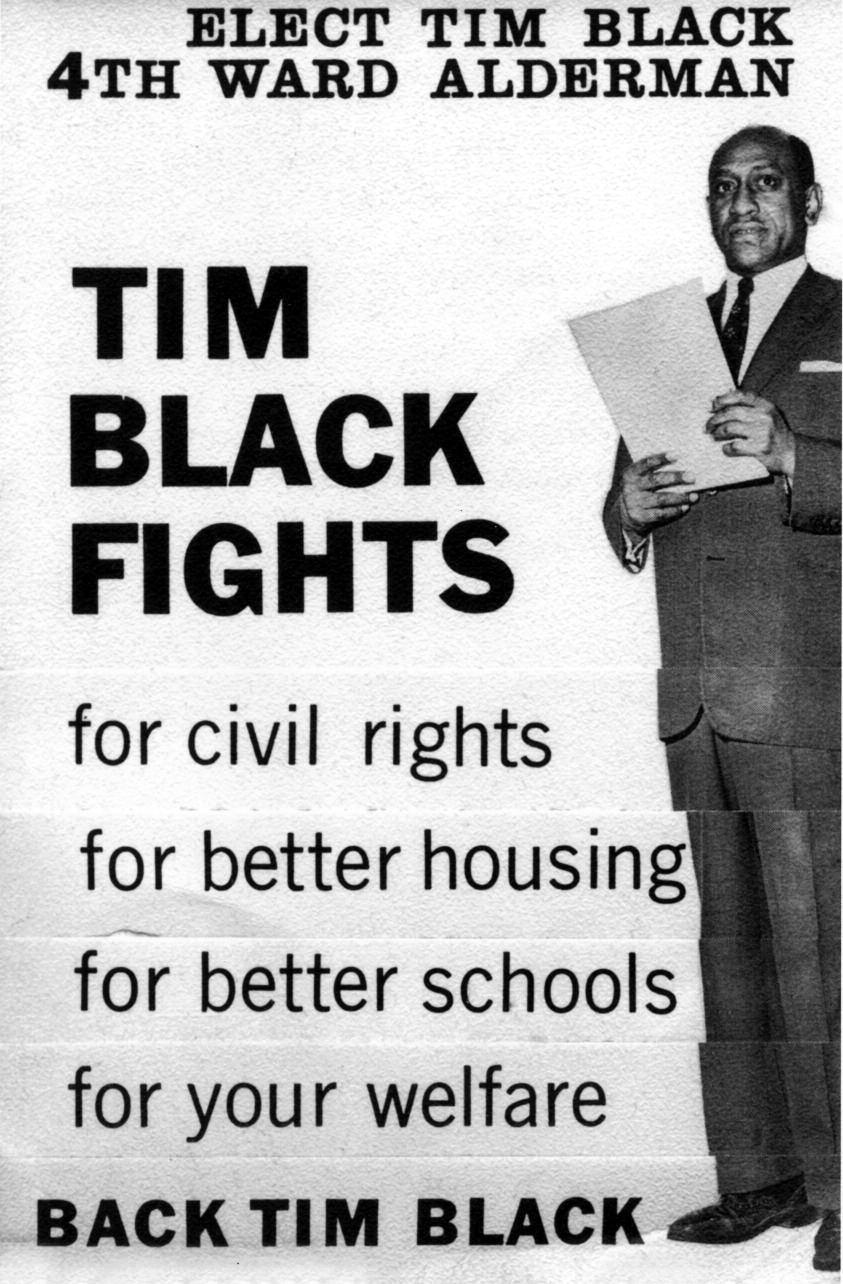

“ To Change Ever ything, We Need Ever yone, ” as recent environmental activists put it, was a ver y familiar thought to Timuel D. Black, the activist, educator, and historian of Chicago’s South Side, who is being honored, and rightly so, in this special issue But Black Tim, as he was known to his friends went beyond anyone in any movement to live that line, to make such protest slogans a meaningful and impactful reality. With his passing, at nearly 103 years of age, we lose perhaps the best-loved radical Chicago has ever known, someone who talked to the elders and the youngers, who built Bridges of Memor y from the past to the present, and the present to the future

To be sure, Tim himself was an endless source of amazing stories and memorable quotes, as his memoir, Sacred Ground: The Chicago Streets of Timuel Black, so amply demonstrates He loved to punctuate his talks and conversations with gems about being “ retired but not tired,” or how he “used to be your age, ” or about working to “make this world a better place,” with that assurance from Sam Cooke that “ a change is gonna come ” He famously condemned “plantation politics” in Chicago, especially during the reign of the first Mayor Daley and the “Silent Six” Black aldermen who always followed the mayor ’ s orders. He could joke with his friends that “there’s only one Black person on the City Council and he’s white,” referring to his friend from the Fifth Ward, Daley critic Leon Despres, who famously opposed the mayor ’ s racist urban renewal policies. His conversation always sparkled with

Timuel D. Black Jr. | 9

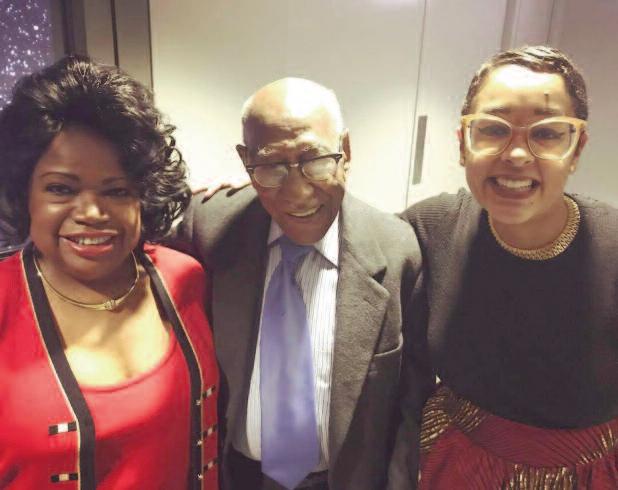

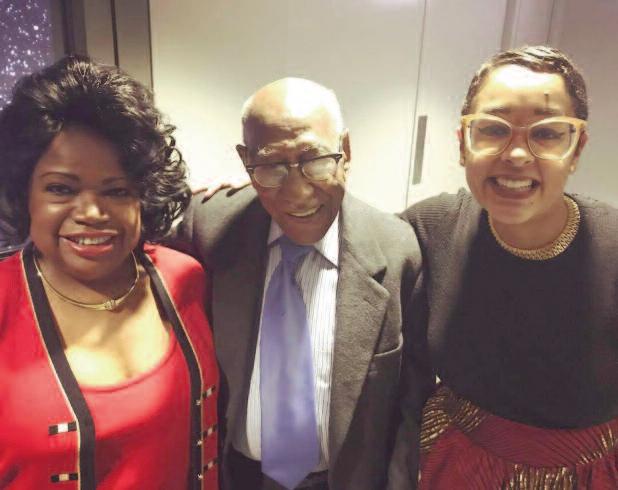

Timuel Black at a book event for Sacred Ground at Wilmette Public Librar y in 2019

insights, humor, and hope for a better world; though with most politicians, he would invoke the words of his beloved grandmother: “I cain’t hear whatcha sayin’ cause whatcha doin’ talks so loud.”

Yet, he was not one of those historic figures living on their past social capital He loved histor y, especially the histor y of his “Sacred Ground,” Chicago’s Bronzeville neighborhood, and he wanted people to learn from it, but he was not trapped in it Being with him was always an exercise in growth wonderful and warm in friendship and fellowship, while carr ying you along in living that change that he was going to do ever ything in his power to bring about He loved and embraced new movements for social justice, whether it was Black Lives Matter or Critical Environmental Justice (both reflected in the University of Chicago garden built in his honor, the Timuel D Black Edible Arts Garden)

As his friend, I was blessed to share some of his time and place, to witness his endlessly supportive enthusiasm for the growth of social justice movements and protests to meet the new and daunting crises confronting the world He might have preferred the words of Rev Dr Martin Luther King Jr , with whom he worked closely, about our all being tied together in “ a single garment of destiny,” but he could also go with “ To Change Ever ything, We Need Ever yone ” He could, more than anyone else I have ever known, truly talk with just about anyone, connect and communicate in real terms, and build in practice the Beloved Community

Warren K. Chapman, PhD Strategic A dvisor Institute for Policy and Civic Engagement University of Illinois at Chicago

Chicago Histor y Museum, Trustee

As Timuel Black traveled through the 102 years of his life, he wore the titles of historian, author, educator, and civil rights activist. However, to know Tim Black in any of these roles is to also know something about jazz Tim loved jazz and constantly intermingled it into his life One could say that his close relationship to this purely American art form is both coincidental and purposeful

Ti m ’ s c h i l d h o o d a n d a d o l e s c e n c e p a r a l l e l s t h a t o f t h e J a z z A g e (1920s–1930s). The South Side of Chicago, where Tim Black grew up, proved to be on the forefront of this cultural period He would often refer to the fact that: “ You couldn’t walk down the street in this neighborhood, any street, and not hear some jazz We grew up immersed in and surrounded by the music Jazz and music were one and the same ”

At the young age of 5, Tim’s mother took him to see Louis Armstrong play at the Vendome Theatre on Thirty-Third and State streets The young man became mesmerized with the artist and his music. Not long after, he met the artist in person, when his neighbor, “Mr Armstrong,” as Tim referred to Louis, would periodically take a group of kids on the block to the movies

By the time Tim reached high school, the world was engulfed in the Great Depression As Tim would often state: “ They called it the Depression, but we weren’t depressed. You see we were already poor, and we found ways to make it, plus, we had the music to inspire us ” In high school, the first student Tim met in his homeroom was named “Nathaniel Coles ” As Tim recalls, “He told me to call him ‘Nat,’ and I was assigned to sit in front of him, it was part of the alphabetical order of the class ” Tim’s new friend would later be known as “Nat King Cole,” the famous jazz vocalist and pianist.

It was at DuSable High School, with its famous jazz band, where Tim Black, began to infuse his love for jazz with education. In his book Sacred Ground,

10 | CHICAGO HISTORY | Spring 2022

“Mr Armstrong” in a promotional photograph from 1944

Tim states: “As a youngster, I didn’t play the music, but I wanted to get to school on time to hear the music The music stimulated me to do better even in all my nonmusical classes. . . . For me, music helped carr y me through adolescence, attracting me to school and increasing my joy and the fun of it ”

Years later, as an educator, Tim attempted to recreate this stimulating environment in his classrooms by integrating jazz into his social studies lesson plans “My focus has been on preserving Chicago’s unique jazz heritage and reinstating it in our high schools, not just by exposing young people to jazz through one-time experiences, but by building and enshrining jazz education programs and partnerships in our high schools for the long term ” Over the past three decades, Tim Black served on the Board of the Jazz Institute of Chicago In this role, he worked tirelessly to increase the love of jazz across generational, racial, and gender lines. He always promoted the idea that jazz was a universal language that contains a common spirituality

There were countless jazz musicians who Tim followed, but it was the music of Duke Ellington that Tim embraced most often In one of his moments of reflection, Tim stated: “ There were times when I was working with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. that the going was tough. But when those times came, I would often recite the lyrics of Duke Ellington’s ‘Come Sunday ’ from his Sacred Concert. ”

Lord, dear Lord above, God almighty, God of love, please look down and see my people through. I believe that God put sun and moon up in the sky, I don’t mind the gray skies ‘ cause they ’ re just clouds passing by

Tim continued: “ Those words would rekindle my spirit and strengthen my belief that we could overcome anything that was in front of us ”

From my perspective, Tim Black always brought a certain passion, rhythm, and beat to whatever task he was tr ying to accomplish Some of his friends and colleagues like singer, songwriter, and civil rights activist Oscar Brown Jr often said: “Brother Tim and I are older than jazz itself, and he could call whatever he was doing Jazz ” For more than 20 years, the Institute has annually awarded the Dr Timuel Black Community Service award to a deserving individual who has actively used jazz as a form of community building and activism in Chicago

Thomas Dyja

Author of The Third Coast: When Chicago Built the American Dream and NEW YORK, NEW YORK, NEW YORK: Four Decades of Success, Excess, and Transformation

Timuel Black’s greatest quality as a historian, I think, was that he saw histor y as something urgent, as a living thing that could bind communities and change the world Only first we needed to see it; we needed to find it where it was living among us, hidden in plain sight So he went out into Black Chicago and found it in the voices of people who hadn’t been listened to, who hadn’t been asked to speak before when it came time to tell the city ’ s histor y He found it in their material culture, collecting the details of life as it was lived here, thus preserving it for future study And he found it by exposing injustice, by providing a record of the structures and indignities that had been overcome. The resulting two volumes of Bridges of Memor y are truly fire now, lighting the way for generations after But histor y to Black was about more than just knowing it was about doing. Those books don’t just light the

Timuel D. Black Jr. | 11

T h e c o v e r s o f Ti m u e l B l a c k ’ s t w o - v o l u m e work: Bridges of Memor y: Chicago’s First Wa v e o f B l a c k M i g r a t i o n ( N o r t h w e s t e r n U n i v e r s i t y P r e s s , 2 0 0 3 ) a n d B r i d g e s o f Memor y: Chicago’s Second Generation of Black Migration (Northwester n University Press, 2008)

study of histor y, they light the way forward against the darkness around us, they come with imperatives. They make others listen to the unheard. They call for improvements in the way people live Most of all they demand justice now Histor y is more than a bridge to memor y; today more than ever, just, accurate, and inclusive histor y is our bridge to the future, and if we are able to reach the other side, it will be in no small part because of the path laid for us by Timuel

Black

Timothy J. Gilfoyle, PhD Professor of Histor y

L oyola University Chicago

Chicago Histor y Museum, Trustee

Timuel Black’s multivolume Bridges of Memor y oral histor y project was and remains a landmark publication, one of the most ambitious oral histor y projects on the histor y of Chicago But in ways unique to any historian of Chicago, Black’s life embodied and personified the ver y essence of the people and movements he chronicled.

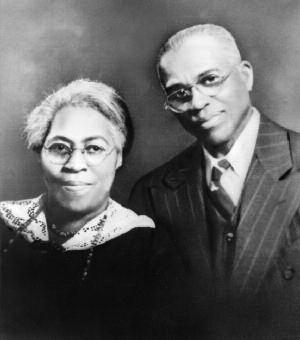

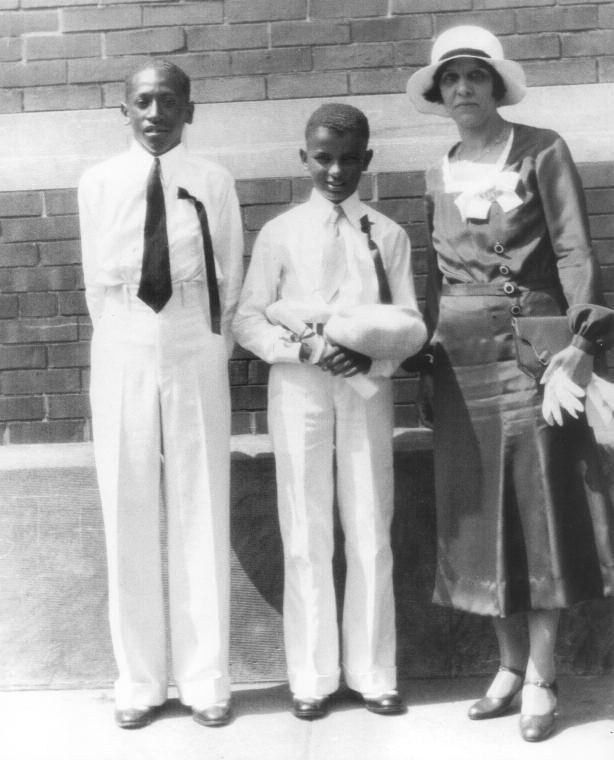

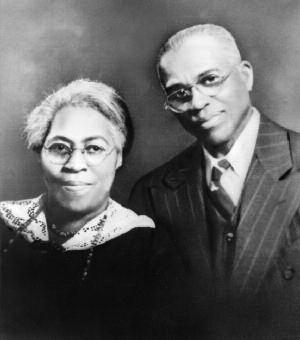

Black’s family migrated to Chicago from Alabama in 1920 and were confined to a “kitchenette” apartment His father found employment in the stockyards

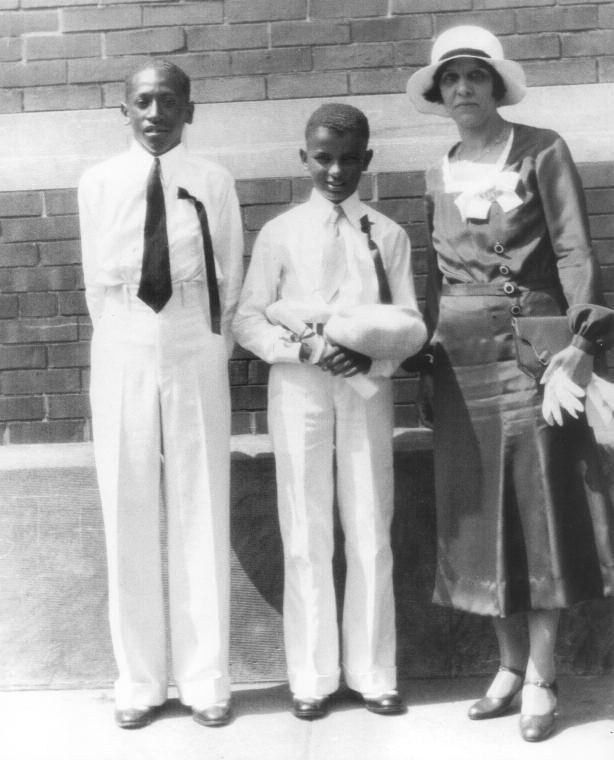

Growing up in Bronzeville, Black’s schoolmates at Wendell Phillips High School [renamed Jean Baptiste Point DuSable High School in 1939], included Nat “King” Cole, Dempsey Travis, and Harold Washington He was also a member of the historic Phillips High School basketball team in 1935–36

Like many young African American adults, Black migrated among a variety of different jobs: a field representative for the Robert Coles Chicago Metropolitan Funeral System, a tanner y worker in Milwaukee, and as a research assistant to the famed sociologist St Clair Drake After participating in the Battle of Bulge in World War II, he returned to Chicago, earned degrees at Roosevelt University and the University of Chicago, and taught in Chicago and Gar y, Indiana, public high schools for 37 years Not surprisingly, Black was one of the first to teach African American histor y He then went on serve as an administrative leader in the City Colleges of Chicago system.

12 | CHICAGO HISTORY | Spring 2022

Exterior view of Wendell Phillips High School (later DuSable High School) located at 244 East Pershing Road in Chicago, c 1904

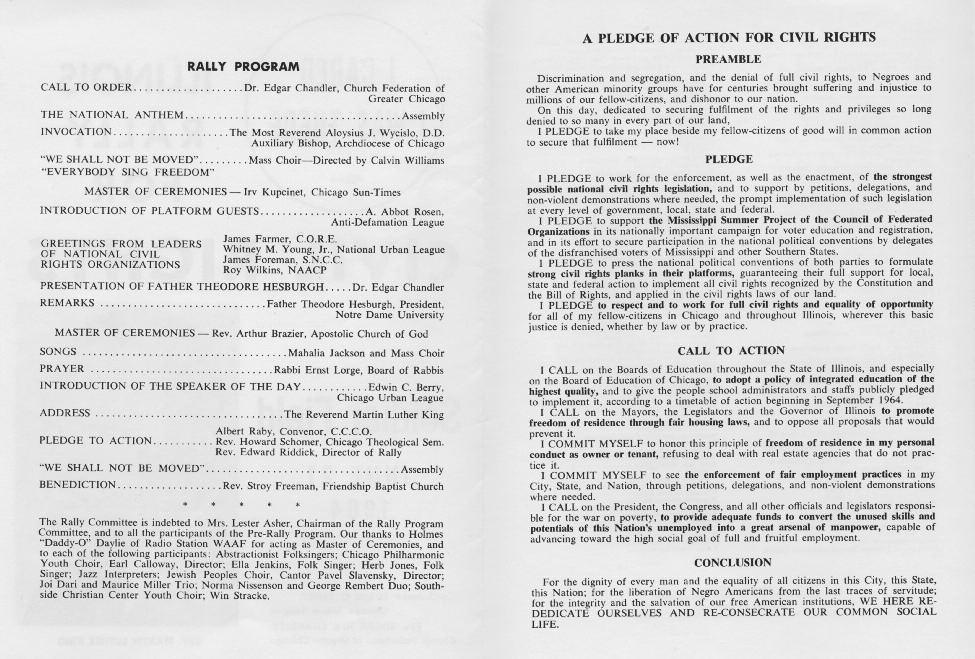

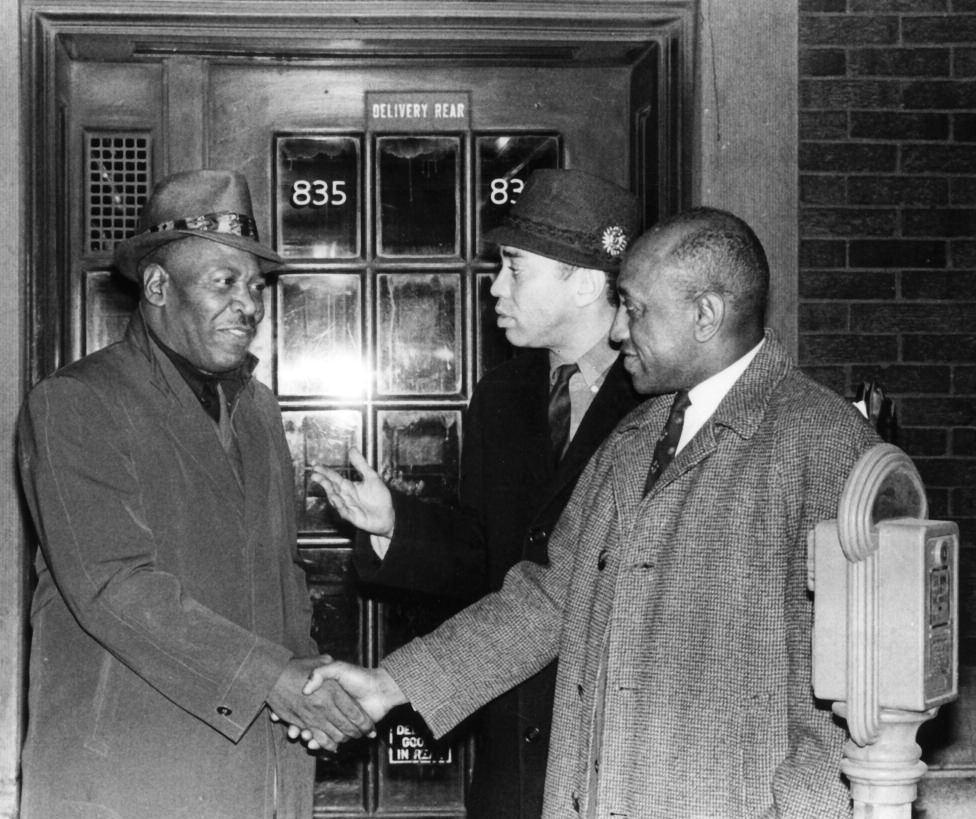

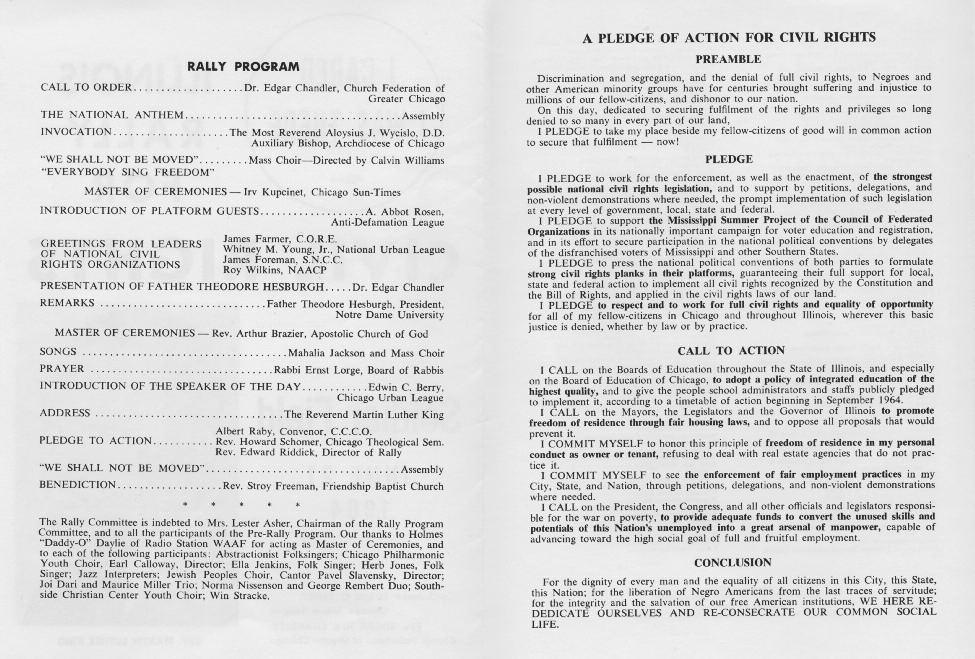

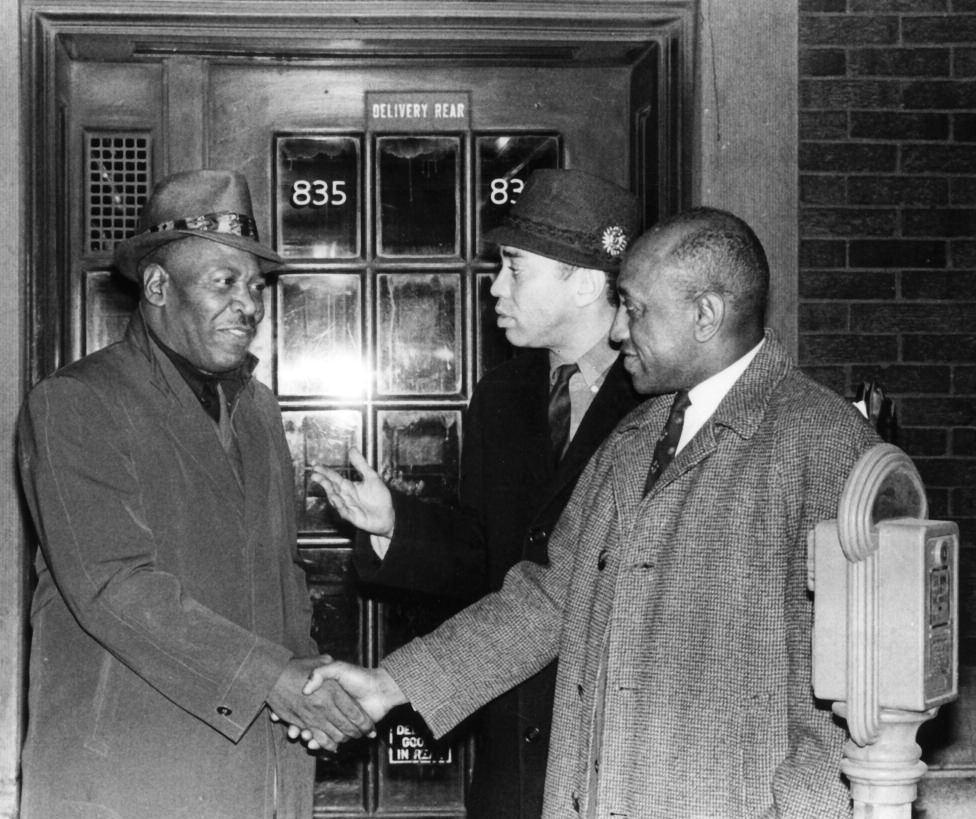

For Timuel Black, histor y was something to live In 1955, he participated in the Montgomer y, Alabama, bus boycott, where he first met Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr He later served as president of Chicago chapter of the Negro American L abor Council and was among the leading Chicago organizers of the famed March on Washington in 1963 Black is often credited with coining the phrase “plantation politics” in reference to the isolated and segregated position to which African Americans were confined in Chicago’s political structure In these and many other ways, Timuel Black the person and the life was historic

Alaka Wali, PhD

Curator of North American Anthropology

The Field Museum

Jacob Campbell, PhD

Environmental Anthropologist

Keller Science Action Center

Field Museum

On July 25, 2019, Timuel Black visited the Field Museum to speak with the Green Ambassadors, a high school summer internship program under the sponsorship of the Keller Science Action Center The Ambassadors came from high schools across Chicago and spent the summer working on documenting social and natural assets in their communities Community partners also brought young people, and Field Museum staff were invited to attend We were thrilled when he agreed to speak to the youth He had already reached his centur y mark but was going as strong as ever Alak a had interviewed him a few years earlier for a project on Bronzeville histor y Jacob interviewed him more extensively later, and both of us were moved and inspired by these conversations. We visited Tim in his home, surrounded by memorabilia from his

R o y W i l k i n s a n d o t h e r c i v i l r i g h t s l e a d e r s g a t h e r o n t h e l a w n i n f r o n t o f t h e Wa s h i n g t o n M e m o r i a l a t t h e M a r c h o n Wa s h i n g t o n f o r J o b s a n d F r e e d o m o n

August 28, 1963 They are carr ying signs from the United Auto Workers

Timuel D. Black Jr. | 13

many activist moments, photos of him with countless iconic figures, and family photos In the interviews, Tim provided vivid descriptions of the Bronzeville he loved He especially enjoyed telling the stor y of the Hansberr y family Here is an excerpt from the interview:

But the Hansberr ys, I was their grocer y boy at Fifty-Ninth and Michigan They were Mr Hansberr y was a businessman and he inherited some of the property, which the white ownership would sell after they had gotten money enough. So he also owned kitchenettes. That’s another part of the stor y of segregation and concentration But Mr Hansberr y believed that p e o p l e s h o u l d h a v e o p p o r t u n i t y t o l i v e w h e r e v e r t h e y w a n t e d i f t h e y could pay the price So, he took the first case to the Supreme Court in 1939 or ’40, that’s Hansberr y v. Lee. So, the family that I serviced at FiftyNinth and Michigan as a grocer y boy, they lived in that block, and they o w n e d t h a t h o u s e T h e y b u i l t i t a n d s o I w o u l d h a v e a c h a n c e t o s e e them; so Carl and Perr y and Lorraine, their sister, they were all younger than me. They were in high school, but I was just out of high school. So, I got to know them quite well

Tim began his presentation to the Green Ambassadors by saying that he first visited the Field Museum in 1925 and has loved it ever since. The youth were visibly in awe of this elder in their presence with a life experience that stretched back so far He was warm and engaging with them The interns led the discussion, asking him questions about the legacy of the Great Migration for Chicago, life in the Black Metropolis, and knowing Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr , Harold Washington, and Barack Obama He urged them to dream big and fight for what they believed in He spoke in clear terms about the horrors he witnessed in World War II and the racism he endured in his life But his message focused on the limitless power of working together toward a common cause and the human potential to overcome adversity We all left that room inspired and moved by this man ’ s example of a life courageously and joyfully lived.

O u t s i d e t h e S u p r e m e L i f e B u i l d i n g o n a t o u r o f T h i r t y - Fi f t h S t r e e t w i t h h i s t o r i a n

Timuel Black, age 82, on July 31, 2001

14 | CHICAGO HISTORY | Spring 2022

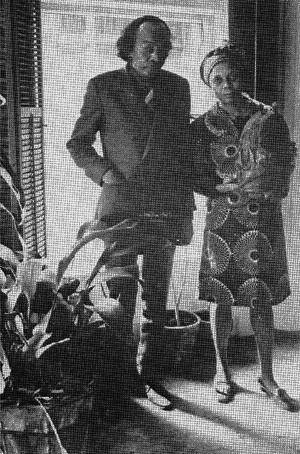

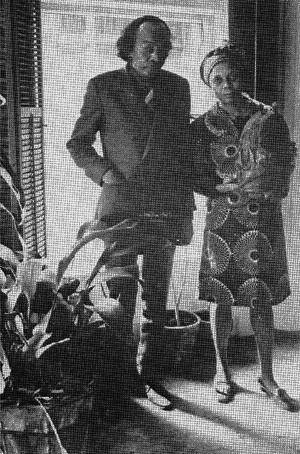

John Russick Senior Vice President Chicago Histor y Museum

I met Timuel D Black Jr in the fall of 1998 at the home he shared with his wife, Zenobia. I was working on my first project for the Chicago Historical Society, an exhibition titled Chicagoans Going Strong. Inspired by the work of o r a l h i s t o r i a n a n d a u t h o r D a v i d I s a y, t h e ex h i b i t i o n f e a t u r e d o l d e r Chicagoans still passionately engaged in their work Tim (he immediately asked me to call him Tim) was a perfect fit for the project, an older Chicagoan who had made histor y many times over and was still at it In addition to Tim, the exhibition featured four other remark able Chicago seniors: Carlos Cortez, Harue Ozaki, Florence Scala, and Art Shay Tim turned 80 just a few weeks later. I had no idea this was the beginning of a relationship that would last more than two decades

Tim passed away last October at age 102 Throughout his life, he remained an advocate for including marginalized voices in historical narratives, specifically the Black experience. A recipient of CHM’s prestigious John Hope Franklin Making Histor y Award for Distinction in Historical Scholarship and the namesake of the Chicago Metro Histor y Fair’s [now Chicago Metro Histor y Day] Timuel Black Teacher of Excellence Award, Tim’s work helped guide the Museum as we sought to build our collection to represent a wider range of communities and people His two -volume publication, Bridges of Memor y provided new and profound perspectives on the Black experience in Chicago and helped foster a new era of historical documentation at the Museum.

Timuel D. Black Jr. | 15

a

E

l l e n c e A

d

t t

g o M e t r

D

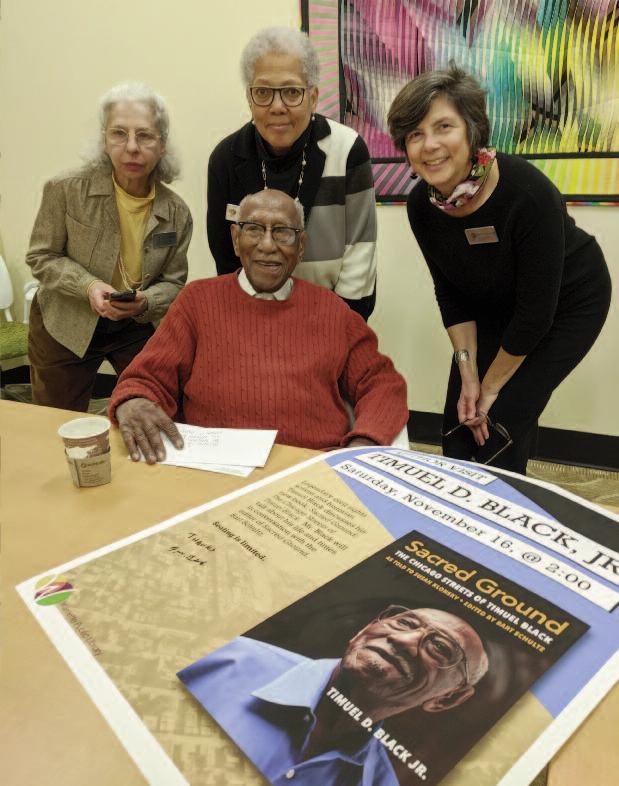

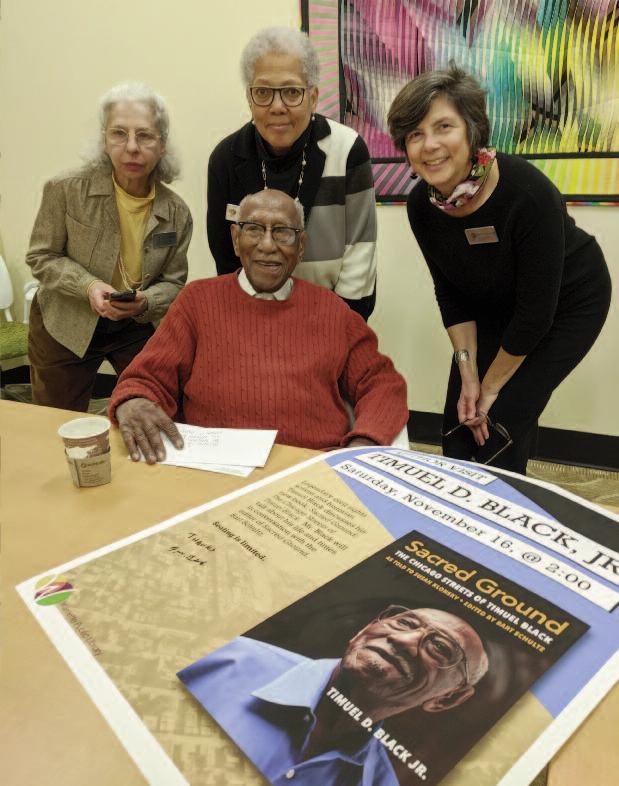

Timuel Black (right) and Zenobia JohnsonB l a c k ( s e c o n d f r o m r i g h t ) w i t h t w o r e p r esentatives from Edwards Dual L anguage & Fi n e a n d Pe r f o r m i n g A r t s I B S c h o o l

c c e p t i n g t h e Ti m u e l B l a c k Te a c h e r o f

xc e

w a r

a

h e C h i c a

o H i s t o r y

a y ’ s ( f o r m e r l y C h i c a g o M e t r o Histor y Fair) Spark Awards

ceremony held a t t h e C h i c a g o H i s t o r y M u s e u m o n M a y 21, 2019.

Beginning in the 1990s, Tim served as both a community collaborator and a scholar for our first collection of projects designed to share the histories of Chicago neighborhoods called Neighborhoods: Keepers of Culture Tim worked to make sure we connected with the people who best understood the histor y from a local perspective. He also convinced many of them to share their knowledge and their collections of photographs, documents, and artifacts with us Needless to say, we could not have done this important work without him

In 2018, the Museum acquired the Chicago Sun-Times photography archive and began developing, Chicago Exposed, a book designed to highlight the significance of the collection Tim, a veteran himself, graciously agreed to let the Museum include an excerpt from his book to accompany images of returning Black soldiers after serving in combat during World War II. The profound stor y of a veteran returning to a countr y seemingly committed to denying him equal status simmers with relevance today

The last time we saw each other was in late 2019 He was giving a talk to a packed house at the Wilmette Public Librar y about Sacred Ground. He shared the stor y of his centur y-long life, answered questions from a curious and appreciative audience, and sat for an hour signing books afterward, reminding ever yone that all people’s stories are valuable Such is Tim’s greatest gift to us. His books, the relationships he built, and the memories he shared are not just meaningful in our time, but they will grow in significance as the Museum continues with the challenging work of writing a better and more inclusive stor y of our city and our countr y

16 | CHICAGO HISTORY | Spring 2022

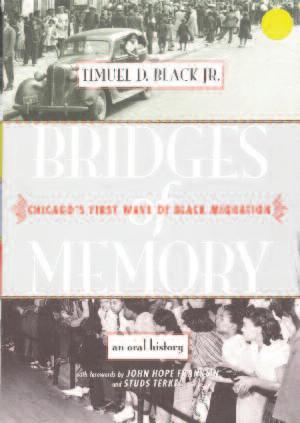

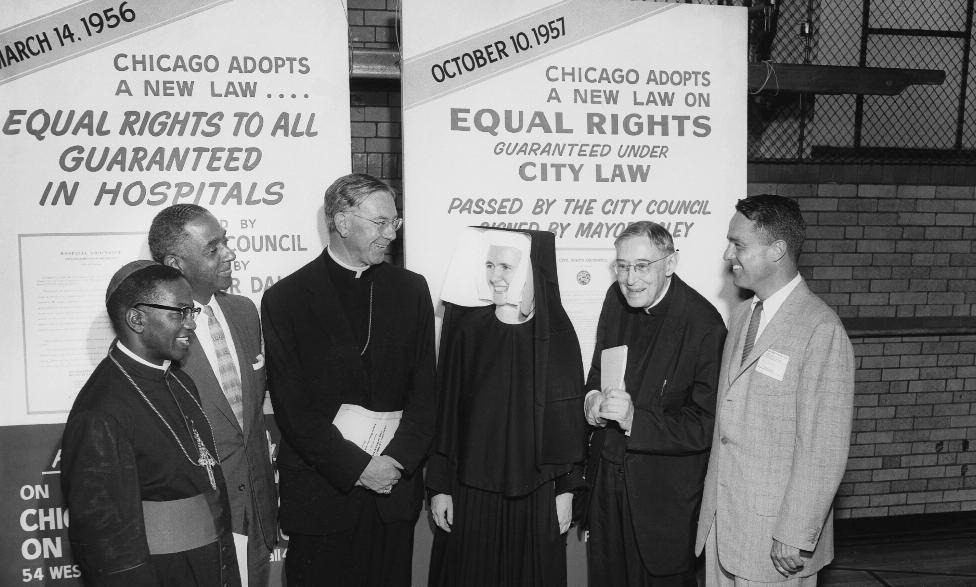

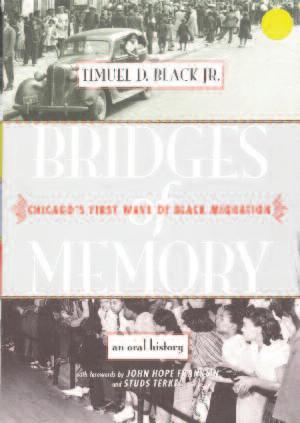

Timuel Black gave a portion of his papers to the Chicago Histor y Museum, including this program for the Illinois R ally for Civil Rights held at Soldier Field on June 21, 1964

Olivia Mahoney Senior Curator (retd) Chicago Histor y Museum

The legendar y Timuel D. Black touched many lives, including mine. I had the honor of working with Tim on the exhibition Douglas/Grand Boulevard: The Past and the Promise in 1995 It was the first in a series of landmark community-based exhibitions developed by the Chicago Histor y Museum that dealt with the rich histor y of Chicago neighborhoods. As the exhibition curator, I was actively involved in the process of working with community residents to tell the rich histor y of the city ’ s South Side I met many fine people who shared their histor y, perspectives, and artifacts with us They became invaluable partners, but none proved more essential than Tim. Community residents revered him as their elder statesman, and I quickly came to understand why His firsthand knowledge of the Great Migration, the Civil Rights Movement, and the South Side proved critical to the success of the project But Tim was not just a witness to histor y, he was also a great humanitarian who deeply understood the common threads of life that should unite, not divide us I recall one day asking him why his family came north from Alabama to Chicago. He paused, smiled gently, and said just one word: “Freedom ” I’ll never forget it

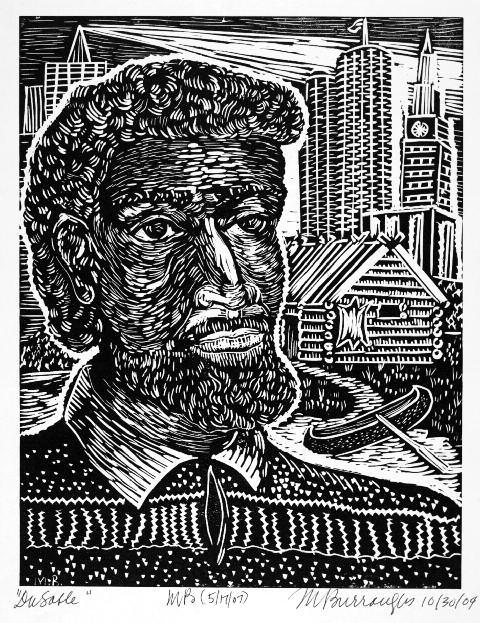

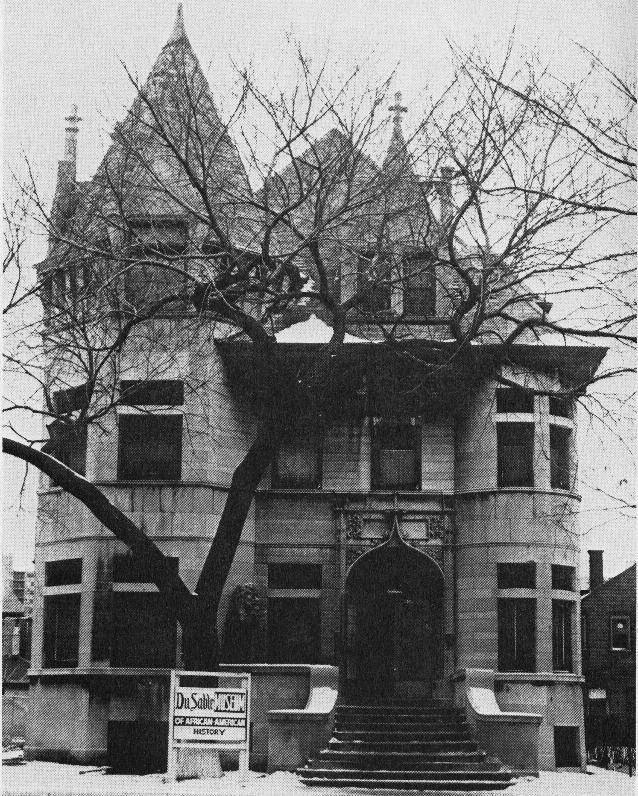

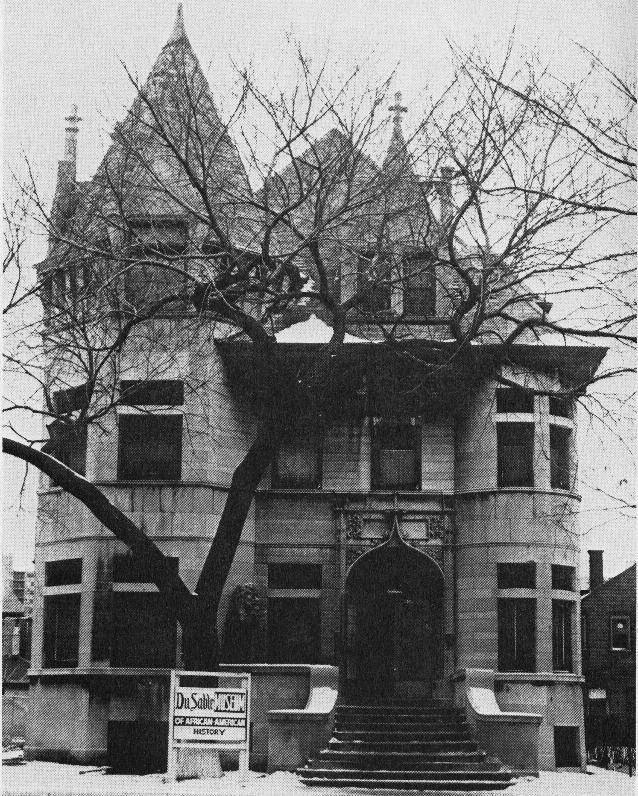

Perri L. Irmer President & CEO

The DuSable Museum of African American Histor y

Although I have known Timuel Black for many years, it never ceases to amaze me how during some of the most iconic moments in histor y, he was there as an eyewitness and was always able to provide little known facts about those once-in-a-lifetime moments, be they heartfelt or humorous.

On several occasions, he would visit the DuSable Museum unannounced, walking through the g a l l e r i e s a n d i n s p i r i n g v i s i t o r s with his knowledge of histor y and historical events

For example, one day he was in the Museum speaking with a group of tourists about the 1963 March on Washington He spoke of being at the Lincoln Memorial for Dr King’s “I Have A Dream” speech, and he recounted that “the highlight was the almost systematic rise in Dr. King’s voice as he enunciated the grievances The crowd was pushing him on and then, of course, when he got to the ‘I Have A Dream’ portion the crowd was just cr ying ”

On another occasion, he spoke about the time in 1966 when Dr King led a Civil Rights March in Chicago’s Marquette Park, and he was marching close behind Dr King when King was struck in the head by a large rock or brick He closed this stor y by saying, “ That’s when I said to myself, ‘if one of them knocks me with a brick this nonviolent movement is over. ’”

Timuel D. Black Jr. | 17

Rev Dr Martin Luther King Jr speaks to the crowd during the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in Washington, DC, on August 28, 1963

18 | CHICAGO HISTORY | Spring 2022

Timuel Black and Zenobia Johnson-Black at the 2018 Spark Awards, held at the Chicago Histor y Museum on September 20, 2018, where Black presented the Timuel Black Teacher of Excellence Award

Tim Black enjoyed friendships with some of the nation’s top leaders, from Dr King to President Obama Black was fond of telling people that he attended Chicago’s DuSable High School with Johnson Publishing Company founder, John H Johnson, singer Nat King Cole, and Archibald Carey Jr., who was the first African American delegate to the United Nations

Professor Black once told me that he was present in the audience when B l a c k b oxe r J o e L o u i s b e a t J i m Braddock to become the heavyweight champion of the world; and that while serving in the militar y during World War II, he participated in two of the war ’ s decisive battles the Normandy Invasion and the Battle of the Bulge as well as the liberation of Paris.

Tim also spoke about what he saw when his unit went all the way from Normandy to the front lines of the N a z i ex t e r m i n a t i o n c a m p s , “ a t Buchenwald concentration camp I saw how human beings were systematically being cremated, the horror was indescribable. I kept thinking, this is [like] what happened to my people during slaver y ”

Timuel Black’s life was shaped by these and many more moments in histor y, and we were privileged to have been blessed to listen and learn from his retelling About a week before his death, I visited Tim at his home. Even during those last days, his heart and mind were still on the struggle for civil rights and equal justice He said to me, “I’ve been able to overcome so many difficulties, racism and prejudice and I know we shall overcome we have to tell the young people to keep on keeping on . . . and I believe that this is going to be a better world.”

I believe so, too, Tim, and I know this is already a better world because for almost 103 years you were part of it

I L L U S T R A T I O N S | Unless otherwise noted, all illustrations are from the Chicago Histor y Museum collection Page 4, ST-70000678, Chicago Sun-Times collection 5, courtesy of Eve L Ewing 6, courtesy of Bart Schultz 7, John H White/Chicago Sun-Times © 2009 Sun-Times Media, LLC 8, ST-17600456, Chicago Sun-Times collection 9, courtesy of Bart Schultz 10, ICHi-025314 11, CHM staff 12, ICHi-019126 13, ICHi-078988 14, Scott Stewart/Chicago Sun-Times © 2001 Sun-Times Media, LLC 15, CHM staff 16, ICHi-068214B 17, ICHi-051643 18, CHM staff 19, courtesy of Bart Schultz

Timuel D. Black Jr. | 19

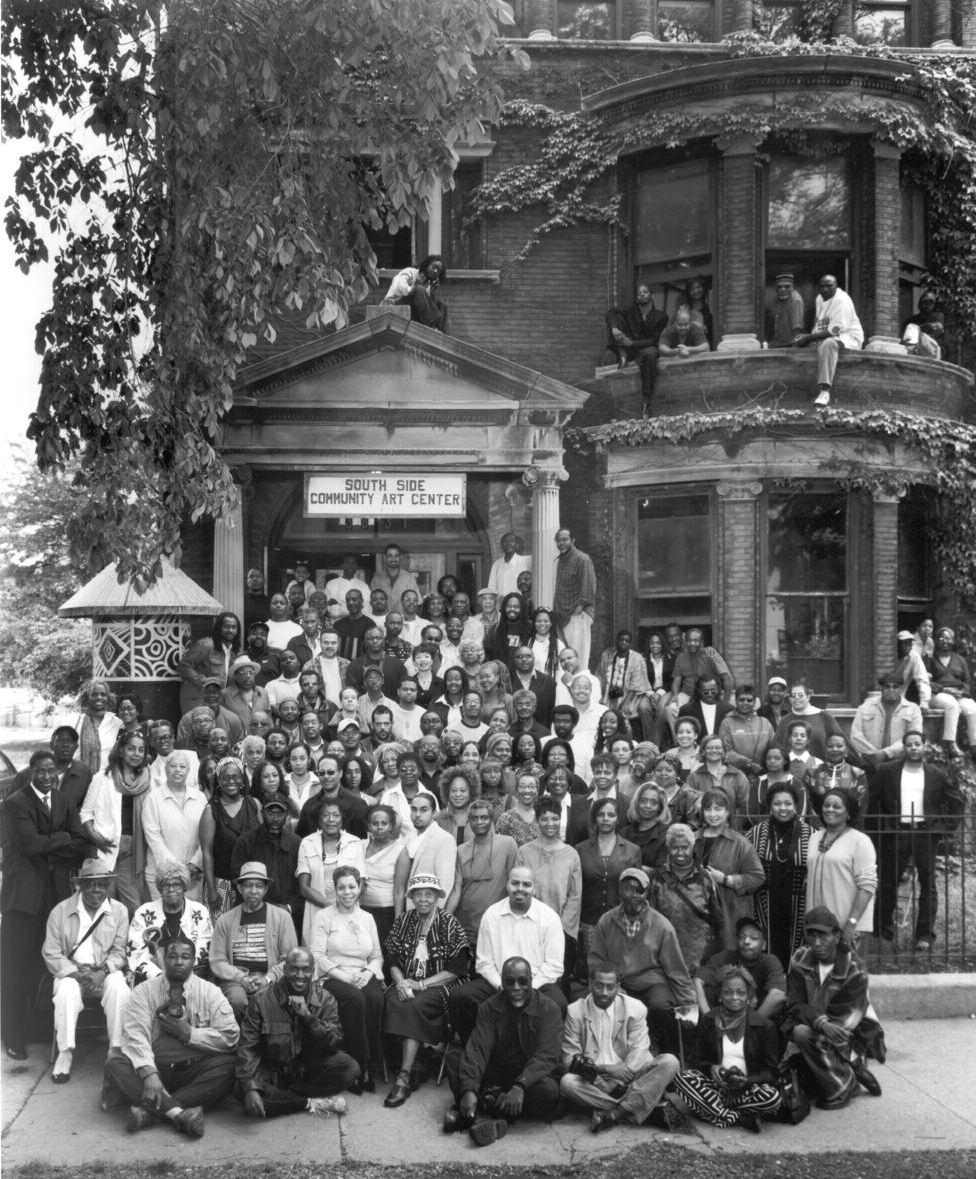

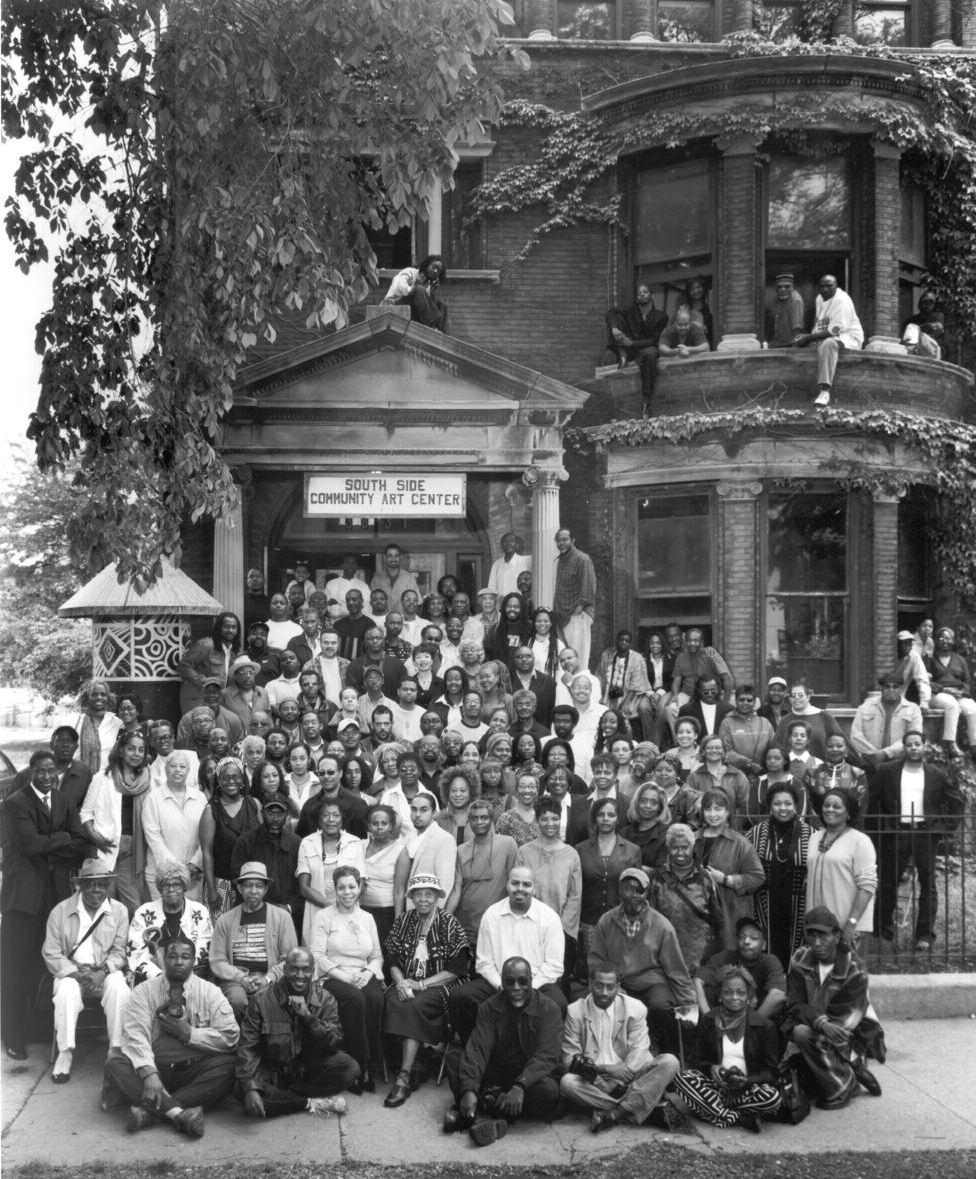

The Presentation—St. Joseph Twinning and Sharing Relationship in the 1970s

On J u n e 2 8 , 1 9 7 0 , r o u g h l y 3 0 0 C a t h o l i c s f r o m t h e p r e d o m i n a n t l y Af r i c a n A m e r i c a n parish of Presentation and the white parish of St Joseph met for a picnic in the Chicago suburb of Libertyville.1 The event proved to be both a festive and educational affair There were a variety of games to participate in, including softball and volleyball 2 Black and white Catholics were also provided with an opportun i t y t o d i s c u s s t h e s o c i o - e c o n o m i c i s s u e s p l a g u i n g t h e C h i c a g o a r e a w i t h s o m e o n e o f a n o t h e r r a c e W h e n d e s c r i b i n g t h e p i c n i c , t h e A r c h d i o c e s e o f C h i c a g o ’ s newspaper, the New World, reported that:

I t s s p e c i a l m a r k s e e m e d t o b e t h a t p e o p l e t a l ke d (and listened) more than they usually do at a church picnic And, eavesdropping, one noticed a spirit of g r e a t o p e n n e s s . T h i s c a n d o r, t h i s w i l l i n g n e s s t o s p e a k o p e n l y o n p r o b l e m s o f r a c e a n d o f c i t y a n d

s u b u r b a n p r o b l e m s , m a y b e t h e m o s t i m p o r t a n t result of the first six months of this “twinning ” There have been other benefits but none seem more s i g n i f i c a n t t h a n t h e p l a i n f a c t t h a t p e o p l e a r e l i stening to one another.3

The article further indicated that “ Walter and Bob, Juanita and Peg, Roberta and Theresa, Sam and Jon, people from city and suburbs talked and listened.” Presumably it was these exchanges, along with the many in attendance, which led St Joseph’s pastor, Msgr Harr y Koenig, to proclaim the picnic “ was a huge success ”4

This picnic was the product of the Archdiocese of Chicago’s “ Twinning” program As defined by historian Dominic Faraone, the Twinning program “paired fiscally healthy parishes with poorer and often minority congre-

20 | CHICAGO HISTORY | Spring 2022

“People from the city and suburbs talked and listened.”

K E V I N R Y A N

Libertyville, Illinois, photographed by Charles R Childs, c 1940

gations for the purpose of sharing financial resources on a continuing basis and forming bonds of affection through social and liturgical events.”5 The program initially began in 1969 with two churches, with more parishes forming Twinning relationships in the first half of the 1970s 6 From 1976 to 1977, the program grew even more to include almost all of the archdiocese’s 453 parishes Amidst this expansion, the name of the program was changed to “Sharing ” According to the Chancer y office, this was done “to highlight [the program ’s] goal of reciprocal relationships between groups of parishes ”7

The primar y purpose of the Twinning and Sharing programs was to funnel aid to financially struggling churches, most of which were located within the city of Chicago By the later 1960s and 1970s, a growing number of urban Catholic parishes and schools struggled to cover their expenses As I have previously mentioned, this fiscal crisis was brought on by “dwindling parishioner and student populations, the declining physical condition of many urban Catholic buildings, a growing reliance on more expensive lay teachers, and rising inflation.” In response to these developments, the Chancer y Office, headed by Archbishop Cardinal John Cody, “lobb[ied] for government aid and provid[ed] millions of dollars to keep struggling parishes and schools open.”8

The Twinning and Sharing programs were seen as another form of monetar y assistance, particularly for financially strapped inner city Catholic schools 9 Throughout t h e 1 9 7 0 s , Tw i n n i n g a n d Sharing relationships generate d m i l l i o n s o f d o l l a r s f o r struggling parishes In several instances, these relationships also led to additional acts of charity for poorer congregations like food and clothing donations, tutoring services, and even employment aid.10

While pairings were primarily meant to help struggling inner city parish schools, arguably the more intriguing aspect of the Twinning and Sharing programs were the potential social interactions between Catholics of different races R acial segregation and inequality were the norm in Cook County neighborhoods and schools in the 1960s and 1970s 11 Twinning, and later Sharing, was envisioned as one way to improve race relations in Chicago In his study, Faraone indicated that one goal of the Twinning program was “to foster mutual aid and dialogue and surmount racial misunderstandings among

Twinning and Sharing | 21

Portrait of Cardinal John Cody

C

e R o m a n C a t h o l i c C h u r c h , a n d s o c i e t y m o r e b r o a d l y, w h i c h i n c l u d e d e v e n t s l i ke t h e

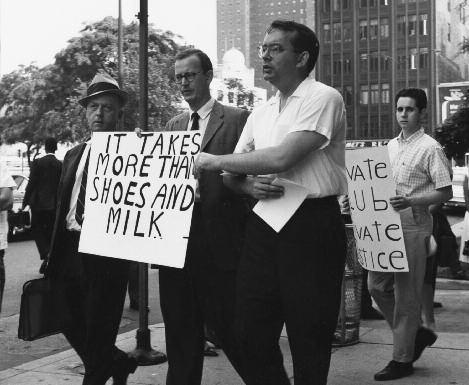

Before the Twinning-Sharing Program in the 1970s, the Catholic Interracial Council of Chicago, established in 1948, sought to promote r a c i a l j u s t i c e w i t h i n t h e

A r c h d i o c e s e o f

h i c a g o , t h

Catholic

Conference for Interracial Justice

Catholics in the city and suburbs ”12 Auxiliar y Bishop Michael Dempsey, the creator of the program, claimed in an August 1972 New World article that Twinning “calls not so much for an exchange of money although that is important but for an exchange of friendship and concern on the part of the two parishes.”13

The relationship that best highlights the social benefits of the Twinning and Sharing programs in the 1970s was the first, Presentation and St Joseph 14 Presentation a n d S t . J o s e p h C a t h o l i c s h o s t e d m a n y g a t h e r i n g s throughout the decade Interactions produced by these social events contributed to greater levels of understanding about racial differences among all participants Some members of both parishes even claimed that outings like the June 1970 picnic provided benefits that were just as, or even more important, than the financial aid provided by St Joseph Studying these interactions, and the understanding they produced, reveals a small, but notable step in race relations in 1970s Chicago and further highlights the benefits interracial contact can produce

The Presentation–St. Joseph Relationship

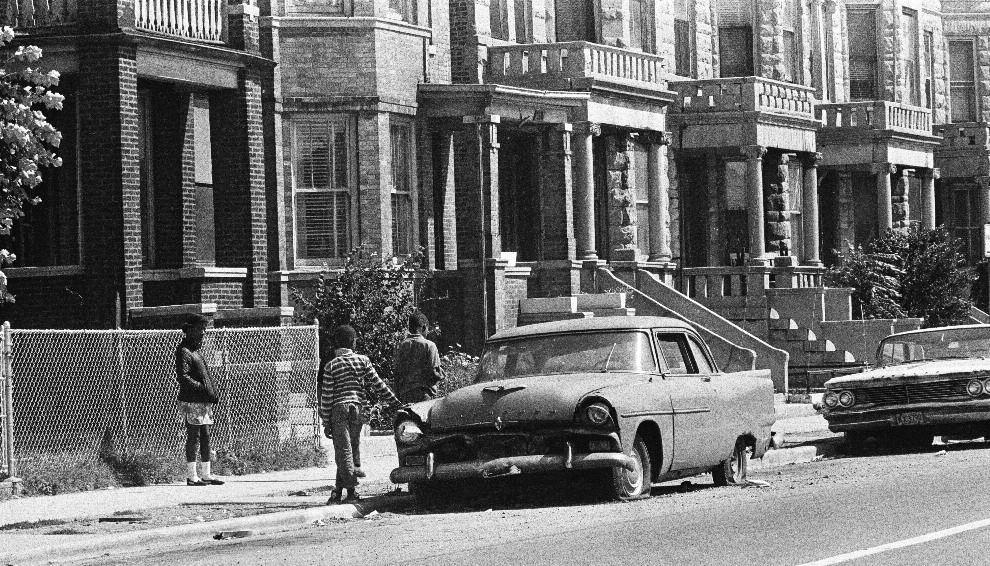

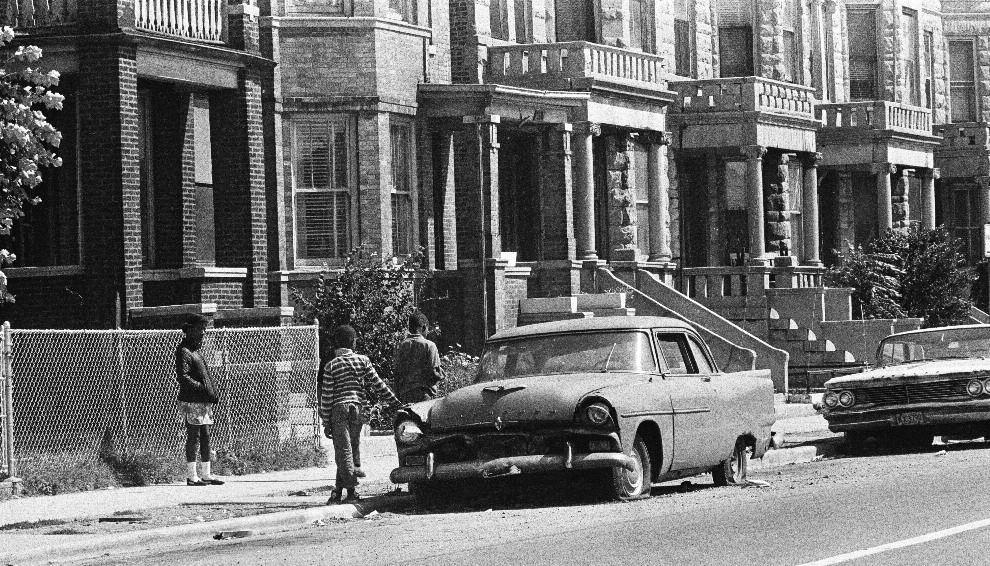

In many ways, the Presentation–St Joseph relationship was the ideal Twinning and Sharing arrangement This pairing involved two churches from ver y different areas Presentation was located in the North L awndale neighborhood on Chicago’s West Side By the late 1960s, North L awndale had undergone racial demographic change and economic decline. Once a predominantly white and heav-

ily Jewish neighborhood, North L awndale’s population was 91% Black by 1960 Amidst this racial turnover, the neighborhood was increasingly plagued by declining city services, overcrowding, physical decay, and poverty 15 Presentation parish mirrored the changes in the surrounding neighborhood. Originally created to serve Irish Catholics in 1898, and home to 1,574 families in 1950, P

African American and ten Hispanic families by the late 1960s. The parish’s small congregation found it difficult to cover all of the costs associated with the operation of the church, the parish school, and the community center During the 1967–68 fiscal year alone, Presentation lost $28,258.36.16 Clergy and parishioners fought to improve the conditions in their church and the surrounding neighborhood, particularly under the pastorship of Msgr John Egan Arguably the most significant of these efforts was the 1968 formation of the Contract Buyers of L awndale, later renamed the Contract Buyers League (CBL) The CBL fought against contract selling17 in North L awndale and other Chicago neighborhoods 18 While Presentation members operated within a struggling inner city community, St Joseph parish existed within a completely different set of circumstances The church was located in the northwestern suburb of Libertyville In the years after World War II, the populations of both the suburb and the church expanded Parish rolls increased to the point where both the church and school buildings were forced to undergo a physical expansion.19

r e s e n t a t i o n w a s c o m p o s e d o f a p p r ox i m a t e l y 3 6 5

22 | CHICAGO HISTORY | Spring 2022

St Joseph's Catholic Church (left) was founded in 1905 in Libertyville, Illinois, while Presentation Church (right) was established in 1898 The Spanish Romanesque-style building was designed by architect William F. Gubbins and built in 1909 near 740 S. Springfield Ave.

Beginning in November 1969, Egan, Msgr Harr y Koenig, and several lay Catholics came together to create t h e P r e s e n t a t i o n – S t . J o s e p h Tw i n n i n g r e l a t i o n s h i p .

According to Faraone, both pastors “ were enthusiastic about twinning their parishes ” These men helped arrange for a meeting of twenty to twenty-four “equally supportive” parishioners “to become acquainted ” Out of this gathering, Koenig claimed “ a splendid relationship between these Black and white people developed ” Additional meetings were held to further progress this a s s o c i a t i o n E g a n , a c c o m p a n i e d b y a n u m b e r o f Presentation parishioners, spoke at all St Joseph masses on Februar y 22, 1970 A brunch was held afterward to allow members of each parish to become better acquainted According to the March 1, 1970, Newsletter to the Friends of Presentation, visiting Presentation parishioners “ were warmly received” by St Joseph Catholics Koenig also spoke at Presentation masses, and some St. Joseph parishioners visited the North L awndale church These initial meetings helped many members of Presentation and St Joseph become more comfortable with one another and the concept of Twinning. This sentiment was perhaps best expressed by Sam Flowers, a member of Presentation Church and a participant in these early meetings He claimed the welcoming spirit of St Joseph parishioners helped many Presentation Catholics overcome their hesitation regarding this new relationship 20

The relationship with St Joseph produced a significant amount of financial aid as well as acts of charity for

Presentation St Joseph Catholics provided $17,000 for Presentation in 1975 alone Presentation also offered some financial assistance to the Libertyville church, as parishioners from the North L awndale parish attended St Joseph fundraisers 21 St Joseph donations had a significant impact on the North L awndale parish. Fr. R aymond Cusack, who was appointed pastor of Presentation in 1970, remarked that Twinning “has kept us alive financially ”22 According to Flowers, money from St Joseph helped keep students in Presentation school by allowing the parish to lower the book fees and tuition rate 23

Twinning and Sharing | 23

Three children stand on the sidewalk in front of a row of houses, near 4214 West Cermak Road in the North L awndale community area on Chicago’s West Side, August 3, 1965.

The exterior of St Joseph’s Catholic Church, still located at 121 E Maple Ave in Libertyville

Several parishioners from Presentation and St. Joseph hoped their Twinning relationship would also lead to interracial contact, friendships, and understanding This hope was evident in the first meetings between the parishes. In July 1970, the New World reported that one meeting between Presentation and St Joseph parishioners in December 1969 included “brave words about ‘building a bridge between city and suburbs,’” though it was also reported that “nobody seemed quite sure what form the program should follow ”24 This uncertainty did not deter participating Catholics from Presentation or St Joseph

For instance, the March 1, 1970, Newsletter to the Friends of Presentation reported that the newly formed Twinning relationship “should establish friendships, mutual educational programs, including a sharing of music, art, and even culinar y practices of the two groups.”25

Throughout the 1970s, many Presentation and St Joseph Catholics attempted to “build a bridge ” They

24 | CHICAGO HISTORY | Spring 2022

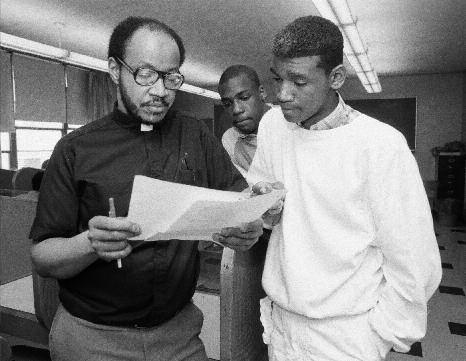

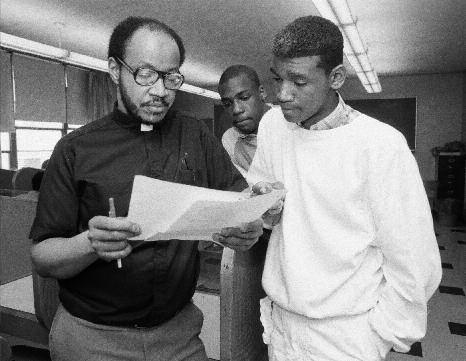

One of many parish schools in the city, Hales Franciscan High School, located in the South Side neighborhood of Bronzeville was established in 1962 as a Catholic high school for African American men

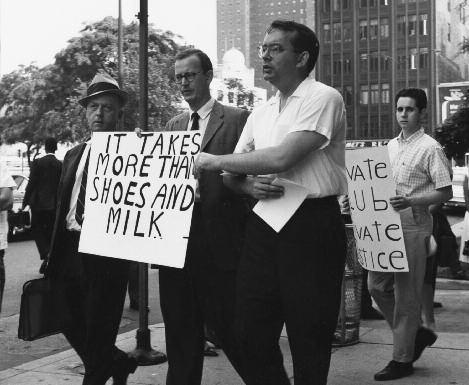

Groups such as the Catholic Interracial Council of Chicago joined other Civil Rights activists and organizations at Grand Central Station on 201 W Harrison Street on August 27, 1963, to board a train for the Freedom March in Washington, DC

attended Mass, parish “organization meetings,” and retreats together 26 They also sponsored several social gatherings 27 While many Presentation and St Joseph Catholics were not present for these events, several were well-attended. A 1971 dance drew a crowd of more than 300 An end of winter picnic at Libertyville High School in 1972 attracted more than 200 participants 28 Other social events included “the spring luncheon of the St Joseph Guild of the Blessed Virgin” in the spring of 1970. The New World reported that “nearly a dozen ladies from Presentation” were present for this event 29 Not all social engagements took place in Libertyville. According to the Presbyteral Senate in 1978, an annual dinner was held at Presentation for “all sharing families ”30 Some also met outside the confines of church-sponsored activities An April 1972 New World article on the Presentation–St. Joseph relationship indicated that “indeed friendships between people of the city and of the suburbs are increasing A number of families in each parish visit regularly and get together socially on an informal basis.”31

These exchanges and relationships contributed to greater levels of racial understanding among participants

During the Catholic Television Network of Chicago’s Januar y 1977 program “Sharing: Our Home Mission,” Joe McDonnaugh indicated that Flowers and other Presentation parishioners helped many members of St Joseph, including himself, better understand the concerns and issues of Black Americans. He stated that his experiences through Twinning helped him realize that “neighbor” includes his “Black brother in the inner city ”32

Patricia Smuck, a housewife from Libertyville, also credited her relationships with Presentation Catholics for improving her own family’s view of African Americans

According to James Bowman of the Chicago Daily News, Smuck, who took part in the meetings that helped form

the Presentation–St. Joseph relationship, spent her childhood “in a home where black people were held in low esteem ” However, because of the relationships she was able to build through Twinning, Smuck was able to introduce her father to some of her “L awndale friends.” After meeting them, Smuck’s father described her “L awndale friends” as “ really great,” to which Smuck responded, “ Yes, Dad. Most black people are. It’s just a few you ran into that gave you a bad impression ”33

Some white Catholics from Libertyville even indicated personal relationships and racial understanding were the most valuable part of Twinning. In a November 1970 New World article, Koenig claimed “the chief value of the ‘twinning’ project [is] the fact that it brings people from both parishes together to get to know one another, to form friendships, to work out problems together.”34 Kevin and Terr y O’Brien, both members of the St Joseph Sharing Committee, also indicated that the knowledge and relationships gained from interracial exchanges were more important than any financial contributions. As indicated in the notes from the December 5, 1978, Presbyteral Senate meeting, the O’Briens’ claimed:

it sounds like all the “giving” is from St. Joe’s, and maybe it is, in the material sense But the warmth, welcome, friendship, etc we receive from Presentation is much more important We have developed lasting, beautiful friendships on an equal footing, and there is much mutual respect between the people at Presentation and the people at St Joe’s ”35

St. Joseph parishioners were not the only Catholics to benefit socially from Twinning and Sharing Flowers indicated religious and social engagements with St Joseph Catholics contributed to greater levels of racial understanding among all participants. In a May 1976 Chicago Daily News article, he claimed, “ Whites wondered why our streets aren’t cleaner and why blacks are on aid and don’t work The blacks figured these wealthy people from Libertyville didn’t know anything. When people talk and see the real human side of life, they learn to respect and understand each other ”36 Like the O’Briens, Flowers also indicated that personal exchanges were more valuable than financial donations. He claimed that “the money exchange has been of small importance compared with people getting to know each other and appreciating the plight of mankind ”37

The Shortcomings of the Twinning and Sharing Programs

Successful interracial exchanges in the Twinning and Sharing programs were not solely limited to just the Presentation–St Joseph pairing 38 However, most parish relationships included few, if any, social engagements In his study, Faraone indicated “the intercommunication

Twinning and Sharing | 25

The Catholic Interracial Council of Chicago participated in demonstrations like this one to promote racial justice, c 1960

between parishes should not be exaggerated.”39 Even the interracial contact between Presentation and St Joseph Catholics was, at times, quite limited Msgr John P O’Donnell, appointed pastor of St Joseph in June 1975, indicated that while money “ideally . . . should not be the only contribution,” financial aid was the primar y expression of his parish’s Twinning relationship 40

There are several reasons why Twinning and Sharing did not produce more interracial contact and relationships in the 1970s Some white Catholics were reluctant to help or even engage with other races While admitting that his parish had not fully participated in the Twinning program, Rev Msgr Donald Masterson, pastor of St Paul of the Cross in suburban Park Ridge, claimed in a June 1976 letter that his parishioners had provided some financial and charitable contributions to St. Bernard’s, a church located in the South Side neighborhood of Englewood However, Masterson also indicated that many of his parishioners did not wish to offer aid to a minority-dominated church He claimed this stemmed from the resentment many felt toward African Americans who “invaded” formerly white ethnic neighborhoods, writing “there are so many people who have been forced to move because their parishes turned black that they are angr y when they are asked to support the people who took their parishes, and I find this is true in this parish also ”41

The Presentation–St Joseph pairing did not appear to suffer from these issues, and yet, as indicated above, at times the social side of this relationship was neglected One problem was distance between the two parishes As early as November 1970, John Justin Smith of St. Joseph indicated the primar y roadblock for greater participation

was the 42 miles between the churches.42 Catholics from Presentation and St Joseph also had difficulty maintaining enthusiasm for their relationship A November 1970 New World article indicated that only one year into this relationship, “the program ’ s momentum has slowed ”43

26 | CHICAGO HISTORY | Spring 2022

Interior view of a mass service at St Ber nard's Catholic Church in the Englewood neighborhood on the city ’ s South Side on May 3, 1953

r e c r u i t i n g B l a c k f a m i l i e s i n 1 9 4 6 a n d h i r e d i t s f i r s t A f r i c a n American

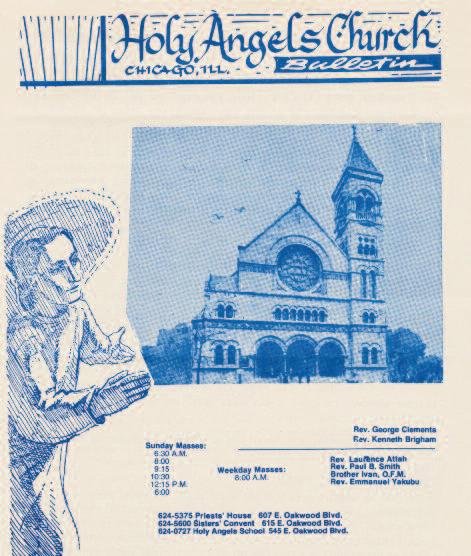

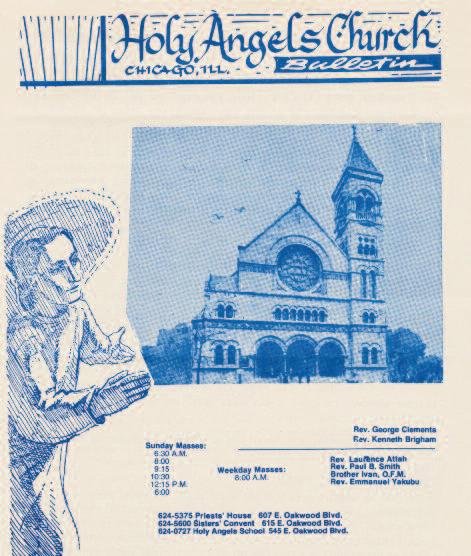

Holy Angels Church, in Chicago’s Bronzeville neighborhood, began

pastor in 1969

L astly, the depopulation of many inner city neighborhoods that helped spark the original Twinning program also, over time, hurt the Presentation–St Joseph relationship 44 North L awndale’s population declined significantly in the 1960s, a process that further reduced the number of Presentation parishioners 45 In a 1988 Chicago Catholic article, Nancy Shroeder, a parishioner at St Joseph, claimed, “In the early days there was a lot of personal contact with families twinned Now there are few families left at Presentation so our contact is mainly limited to two sharing Masses followed by potluck dinners ”46

Over time, distance and demographic changes made it difficult for Presentation and St Joseph to maintain an active social relationship Nevertheless, the Catholics from North L awndale and Libertyville arguably came closer than any other parishes to achieving both the financial and social goals of the Twinning and Sharing programs From 1969 through the 1970s, the Presentation–St Joseph relationship generated thousands of dollars for Presentation, sponsored interracial gatherings, and facilitated interracial relationships and understanding

u s e s o n t h e r e l a t i o n s h i p b e t w e e n t h e Catholic Church, race, and the city in the Archdioscese of Chicago in the 1960s and 1970s

E N D N O T E S

1 “Bridge of Love Links L awndale to Libertyville,” New World, July 24, 1970, 9; Rev Msgr Harr y C Koenig, ed , A Histor y of the Parishes of the Archdiocese of Chicago: Published in Observance of Centenar y of the Archdiocese vol I (Chicago: Catholic Bishop of Chicago, 1980), 805, 808, 809; Rev Msgr Harr y C Koenig, ed , A Histor y of the Parishes of the Archdiocese of Chicago: Published in Observance of Centenar y of the Archdiocese vol II (Chicago: Catholic Bishop of Chicago, 1980), 1303, 1306–7

2 “Bridge of Love Links L awndale to Libertyville,” 9

3 Ibid

4 Ibid

5 Dominic Faraone, “Urban Rifts and Religious Reciprocity: Chicago and the Catholic Church, 1965–1996,” PhD diss , Marquette University, Milwaukee, May 2013, 115 Faraone provides an excellent overview of the Twinning and Sharing programs in his dissertation,

b o t t o m : I C H i - 1 7 3 7 3 4 . 2 2 , l e f t : L i b e r t y v i l l e - M u n d e l e i n

H i s t o r i c a l S o c i e t y ; r i g h t : Pe r c y H S l o a n p h o t o g r a p h s , Newberr y Librar y 23, top: ST-15001688-0003, Chicago

S u n -Ti m e s c o l l e c t i o n ; b o t t o m : S t J o s e p h ’ s C a t h o l i c Church. 24, top: ST-10001899-0038, Chicago Sun-Times

c o l l e c t i o n ; b o t t o m : S T- 5 0 0 0 4 8 5 0 - 0 0 0 5 , C h i c a g o S u nTi m e s c o l l e c t i o n 2 5 , I C H i - 0 6 1 5 6 6 2 6 , t o p : I C H i173739; bottom ICHi-086335

F O R F U R T H E R R E A D I N G | Fo r m o r e o n s o c i a l i s s u e s t a ke n u p b y t h e A r c h d i o c e s e o f C h i c a g o a f t e r World War II, see Ann Dempsey Burke, The Bishop Who

D a r e d : A B i o g r a p h y o f M i c h a e l R y a n D e m p s e y ( Va l ky r i e P r e s s , 1 9 7 8 ) ; S t e v e n Av e l l a , T h i s C o n f i d e n t C h u r c h :

C a t h o l i c L e a d e r s h i p a n d L i f e i n C h i c a g o , 1 9 4 0 – 1 9 6 5 (University of Notre Dame Press, 1992). For more on the histor y of racial discrimination and segregated housing in Chicago, see D Bradford Hunt, Blueprint for Disaster:

T h e U n r a v e l i n g o f C h i c a g o P u b l i c H o u s i n g ( U n i v e r s i t y o f C h i c a g o P r e s s , 2 0 0 9 ) ; B e r y l S a t t e r, Fa m i l y P r o p e r t i e s :

R a c e , R e a l E s t a t e , a n d t h e E x p l o i t a t i o n o f B l a c k U r b a n America (Henr y Holt and Company, 2009)

“Urban Rifts and Religious Reciprocity,” on pages 114–30

6 For more on Twinning’s expansion in the first half of the 1970s, see Floyd Anderson, “Inner City Apostolate,” New World, August 18, 1972, 9; Ann Dempsey Burke, The Bishop Who Dared: A Biography of Michael R yan Dempsey (St Petersburg, FL: Valkyrie Press, Inc , 1978), 128–29, 148; Bishop Michael Dempsey to Archbishop John Cody, September 16, 1970, 1, “Inner City Apostolate Meeting, 10/24/1967” file, Archdiocese of Chicago Joseph Cardinal Bernardin Archives and Record Center (hereafter ACA); Bishop Michael Dempsey to Edward Marciniak, July 19, 1971, 2, “M R D Corresp 1971” file, Administrative Records –Correspondence Files, Dates: 1/1/1958 to 12/31/1958, ADMN/C5920/299, ACA ; Faraone, “Urban Rifts and Religious Reciprocity,” 117; Bishop William McManus to Rev Msgr Francis Brackin, June 15, 1976, 4, Association of Chicago Priests, CACP 16/41, “Sharing Program (Twinning)” file,

Hesburgh Librar y, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, IN (hereafter UND); Presbyteral Senate Meeting, “Sharing,” December 5, 1978, 1, Administrative Records – Proposals Files – Presbyteral Senate; Record Number ADMIN/P734/19L Dates 1/1/1972 to 12/31/1996, ACA

7 For more on Twinning’s transformation into Sharing, see James Bowman, “Cody Asks Help for 58 Parishes,” Chicago Daily News, September 10, 1976, Most Rev Francis Brackin EXEC/E2610/235, Room 4, Bay 462, Shelf 6, Position 1, ACA ; James B Burke, “Sharing is Now a Way of Life,” Chicago Catholic, September 22, 1978, 1; Faraone, “Urban Rifts and Religious Reciprocity,” 120–24; Mar y Claire Gart, “’Sharing’ Plan Unites Catholics in Suburban and City Parishes,” New World, May 6, 1977, 1, 12; Kevin Ryan, “Catholic Liberal Interracialism in the Archdiocese of Chicago in the 1960s and 1970s,” PhD diss , State University of New York at Buffalo, 2016, 273–84; “Sharing by the Archdiocese of Chicago,” Catholic

K e v i n R y a n i s a n a s s i s t a n t p r o f e s s o r o f h i s t o r y a t D’ Yo u v i l l e U n i v e r s i t y. H i s r e s e a r c h f o c

Twinning and Sharing | 27

I L L U

t r a t

e f r o m t

e c

c

M u s e u m

u n l e s s o t h e r w i s e

C H i -

0 2 1 , t o p : I C H i

0 6 1 5 6

S T R A T I O N S | I l l u s

i o n s a r

h

o l l e

t i o n o f t h e C h i c a g o H i s t o r y

,

n o t e d Pa g e 2 0 , I

1 6 4 1 9

-

4 ;

Television Network of Chicago, John J Egan Papers, AJEG 10766 CT: Sharing by the Archdiocese of Chicago, Hesburgh Librar y, UND

8 Kevin Ryan, “To ‘Prepare White Youngsters’: The Catholic School Busing Program in the Archdiocese of Chicago,” American Catholic Studies 128, no 3 (Fall 2017): 75 It should be noted that Faraone also argued that Twinning was a Catholic response to the “post-industrial transition ” Faraone, “Urban Rifts and Religious Reciprocity,” 10, 43–45, 69–70, 73–75, 108–30, 146–47 For additional information on the Catholic urban fiscal crisis that materialized by the later 1960s and 1970s, see Faraone, “Urban Rifts and Religious Reciprocity,” 64, 82–86, 89–90, 97–100, 102–5, 113, 124; Ryan, “Catholic Liberal Interracialism in the Archdiocese of Chicago in the 1960s and 1970s,” 226–36, 276–77

9 Burke, The Bishop Who Dared, 128–29; Archbishop John Cardinal Cody to Brother Priests, Holy Thursday, 1979, 1, Most Rev Francis Brackin, EXEC/E2610/235, Room 4, Bay 462, Shelf 6, Position 1, ACA ; Dempsey to Cody, September 16, 1970, 1; Faraone, “Urban Rifts and Religious Reciprocity,” 124; Ryan, “Catholic Liberal Interracialism in the Archdiocese of Chicago in the 1960s and 1970s,” 231–36, 276–77

10 For information on financial contributions produced by Twinning and Sharing, see Bowman, “Cody Asks Help for 58 Parishes”; Burke, “Sharing is now a way of life,” 1; Faraone, “Urban Rifts and Religious Reciprocity,” 122 Examples of charitable acts between Twinning partners are discussed in letters from various priests to Rev Msgr Francis Brackin, which can be found in the Francis Brackin Papers at the Archdiocese of Chicago Joseph Cardinal Bernardin Archives and Record Center Other instances of charity between Twinning and Sharing partners can be found in the Association of Chicago Priests Records’ “Sharing Program (Twinning)” and “Sharing P E P ” files at the Hesburgh Librar y at the University of Notre Dame Additional examples can be found in Faraone, “Urban Rifts and Religious Reciprocity,” 118–19, 122–23

11 For more information on racial segrega-

tion and inequality in the Chicago area in the 1960s and 1970s, see Alan B Anderson and George W Pickering, Confronting the Color Line: The Broken Promise of the Civil Rights Movement in Chicago (Athens and London: The University of Georgia Press, 1986); Steven Avella, This Confident Church: Catholic Leadership and Life in Chicago, 1940–1965 (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 1992); Faraone, “Urban Rifts and Religious Reciprocity,” 200–2; Arnold Hirsch, Making the Second Ghetto: R ace and Housing in Chicago, 1940–1960 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983); D Bradford Hunt, Blueprint for Disaster: The Unraveling of Chicago Public Housing (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009); K aren Joy Johnson, “ The Universal Church in the Segregated City: Doing Catholic Interracialism in Chicago, 1915–1963,” PhD diss , University of Illinois at Chicago, 2013; Ann Durkin Keating, ed , Chicago Neighborhoods and Suburbs: A Historical Guide (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008); James R alph, Jr , Norther n Protest: Martin Luther King, Jr , Chicago, and the Civil Rights Movement (Cambridge, MA : Harvard University Press, 1993); Ber yl Satter, Family Properties: R ace, Real Estate, and the Exploitation of Black Urban America (New York: Henr y Holt and Company, 2009); Amanda Seligman, Block by Block: Neighborhoods and Public Policy on Chicago’s West Side (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 2005) Much of this information appears in a footnote in one of my previous articles, Kevin Ryan, “‘My Children Feel Rejected by their Church’: ‘Managed Integration’ at St Philip Neri Parish, Chicago,” U S Catholic Historian 35, no 1 (Winter 2017): 84

12 Faraone, “Urban Rifts and Religious Reciprocity,” 115

13 Anderson, “Inner City Apostolate,” 9; Burke, The Bishop Who Dared, vii, 128; Newsletter to the Friends of Presentation, March 1, 1970, 2, John J Egan Papers, CJEG 99/16: “FRIENDS OF PRESENTATION” file, Hesburgh Librar y, UND

14 Faraone, “Urban Rifts and Religious Reciprocity,” 115–16; Presbyteral Senate Meeting, “Sharing,” 1

15 James Bowman, “Parishes ‘ Twin’ for Double Reward of Aid, Understanding,” Chicago Daily News, May 22–23, 1976, Most Rev. Francis Brackin, EXEC/E2610/235, Room 4, Bay 462, Shelf 6, Position 1, ACA ; Robert Cross, “ The City, The Church,” Chicago Tribune Sunday Magazine, November 17, 1968, 42; Faraone, “Urban Rifts and Religious Reciprocity,” 116; Marger y Frisbie, An Alley in Chicago: The Ministr y of a City Priest (New York: Sheed & Ward, 1991), 188, 206–7, 224; Koenig, A Histor y of the Parishes of the Archdiocese of Chicago vol I, 805, 808, 809; Koenig, A Histor y of the Parishes of the Archdiocese of Chicago vol II, 1307; R alph, Norther n Protest, 46–48, 109–13, 143, 230; Satter, Family Properties, 17–19, 28–30, 94–95, 169, 329–30; Seligman, Block By Block, 21–22, 34, 50, 79–87, 93–98; Amanda Seligman, “North L awndale,” Chicago Neighborhoods and Suburbs: A Historical Guide (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008), 237–38

16 Information about the struggles of Presentation parish in the 1960s can be found in the John J Egan Papers’ “Presentation Parish Newsletter ” file at Notre Dame’s Hesburgh Librar y, especially the Friends of Presentation

Newsletters from 1966 to 1969

Additional information about Presentation can be found in Cross, “ The City, The Church,” 42, 58; Frisbie, An Alley in Chicago, 181–87, 190–91; Koenig, A Histor y of the Parishes of the Archdiocese of Chicago vol I, 805, 808

17 Contract selling refers to the purchase of overpriced homes “ on an installment plan ” Missing one payment could result in eviction as contract buyers did not gain ownership of the property until their contract “ was paid in full ” In 1950s Chicago, the majority of African Americans who purchased homes outside of Black neighborhoods did so “ on contract ” The product of discriminator y housing policies, contract selling burdened many African Americans with evictions and debt Satter, Family Properties, 3–5, 11, 38, 294, 305, 331

18 For more on the programs at Presentation and the work of the CBL, see Frisbie, An Alley in Chicago, 176–77, 181–87, 190–91, 197–206, 208, 224–25, 228–29; Koenig, A Histor y of

28 | CHICAGO HISTORY | Spring 2022

the Parishes of the Archdiocese of Chicago vol I, 808; Satter, Family Properties

19 Faraone, “Urban Rifts and Religious Reciprocity,” 116; Koenig, A Histor y of the Parishes of the Archdiocese of Chicago vol II, 1303, 1306–7; Craig Pfannkuche, “Libertyville, IL,” Chicago Neighborhoods and Suburbs: A Historical Guide (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008), 192–93

20 Bowman, “Parishes ‘ Twin’ for Double Reward of Aid, Understanding”; “Bridge of Love Links L awndale to Libertyville,” 9; Faraone, “Urban Rifts and Religious Reciprocity,” 116–17; Koenig, A Histor y of the Parishes of the Archdiocese of Chicago vol I, 808; Koenig, A Histor y of the Parishes of the Archdiocese of Chicago vol II, 1306–7; Msgr Harr y Koenig to Rev Msgr Francis Brackin, June 18, 1976, 1–2, Association of Chicago Priests Records, CACP 16/41, “Sharing Program (Twinning)” file, Hesburgh Librar y, UND; Kenneth Kozak, “‘ Twinning Brings Suburb, City Parishes

Together,” New World, November 11, 1970, 11; Newsletter to the Friends of Presentation, March 1, 1970, 2; Msgr John P O’Donnell to Rev Msgr Francis Brackin, July 3, 1976, 1, Association of Chicago Priests Records, CACP 16/41, “Sharing Program (Twinning)” file, Hesburgh Librar y, UND; Frederick Perella, Jr , “Roman Catholic Approaches to Urban Ministr y, 1945–85,” Churches, Cities, and Human Community: Urban Ministr y in the United States, 1945–1985 (Grand R apids, MI: Wm B Eerdmans Publishing Co , 1996), 187; “Sharing by the Archdiocese of Chicago,” Catholic Television Network of Chicago

21 Bowman, “Parishes ‘ Twin’ for Double Reward of Aid, Understanding”; Frisbie, An Alley in Chicago, 182; Presbyteral Senate Meeting, “Sharing,” 3

22 Koenig, A Histor y of the Parishes of the Archdiocese of Chicago vol I, 808; Perspective of the Presbyteral Senate of the Archdiocese of Chicago, March 1977, 2, Association of Chicago Priests Records, CACP 16/21, “Sharing P E P ” file, Hesburgh Librar y, UND

23 “Sharing by the Archdiocese of Chicago,” Catholic Television Network of Chicago

24 “Bridge of Love Links L awndale to Libertyville,” 9

25 Newsletter to the Friends of Presentation, March 1, 1970, 2

26 “Bridge of Love Links L awndale to Libertyville,” 9; Faraone, “Urban Rifts and Religious Reciprocity,” 117; Kozak, “’Twinning’ Brings Suburb, City Parishes Together,” 11; Perspective of the Presbyteral Senate of the Archdiocese of Chicago, 2; Presbyteral Senate Meeting, “Sharing,” 2–3; Untitled notes from People Encountering People Committee Meeting, May 24, 1976, Association of Chicago Priests Records, CACP 16/21, “Sharing P E P ” file, Hesburgh Librar y, UND

27 Faraone, “Urban Rifts and Religious Reciprocity,” 117; Kozak, “‘ Twinning’ Brings Suburb, City Parishes Together,” 11; Presbyteral Senate Meeting, “Sharing,” 3; “Sharing by the Archdiocese of Chicago,” Catholic Television Network of Chicago

28 “Picnic Links ‘ Twinning’ Parishes,” New World, April 7, 1972, 13

29 Kozak, “‘ Twinning’ Brings Suburb, City Parishes Together,” 11

30 Presbyteral Senate Meeting, “Sharing,” 3

31 “Picnic Links ‘ Twinning’ Parishes,” 13

32 “Sharing by the Archdiocese of Chicago,” Catholic Television Network of Chicago

33 Bowman, “Parishes ‘ Twin’ for Double Reward of Aid, Understanding ”

34 Koenig was quoted in Faraone, “Urban Rifts and Religious Reciprocity,” 118–19 The original quote appears in Kozak, “‘ Twinning’ Brings Suburb, City Parishes Together,” 11

35 Presbyteral Senate Meeting, “Sharing,” 3

36 Bowman, “Parishes ‘ Twin’ for Double Reward of Aid, Understanding ”

37 Ibid

38 The relationship between the South Side Black church of St Clara and St Cyril and St Anne of suburban Barrington included several interracial interactions For more information about this relationship, see Bowman, “Parishes ‘ Twin’ for Double Reward of Aid, Understanding”; Presbyteral Senate Meeting, “Sharing,” 4–5 It is also worth noting that Faraone argued that “ Twinning/Sharing was modestly

successful, in part because it was interparochial and fostered an awareness of interdependency without breaching the traditional autonomy of parishes ” Faraone, “Urban Rifts and Religious Reciprocity,” 116