CHICAGO HISTORY

Laura Herrera

Editors

Heidi A. Samuelson

Esther D. Wang

Designer

Bill Van Nimwegen Photography Timothy Paton Jr.

Copyright©2021bythe

ChicagoHistoricalSociety

Clark Street at North Avenue Chicago,IL60614-6038 312.642.4600 chicagohistory.org ISSN 0272-8540

Articles appearing in this journalareabstractedand indexed in Historical Abstracts andAmerica:HistoryandLife.

CHICAGOHISTORICALSOCIETY

Daniel S. Jaffee Chair

Mary Lou Gorno

First Vice Chair

Warren K. Chapman Second Vice Chair

Mark D. Trembacki Treasurer

Denise R. Cade Secretary

Donald E. Lassere

Edgar D. and Deborah R. Jannotta President

HONORARYTRUSTEE

The Honorable Lori Lightfoot Mayor, City of Chicago

James L. Alexander

Denise R. Cade

Paul Carlisle

Walter C. Carlson

Warren K. Chapman

Rita S. Cook

Patrick F. Daly

James P. Duff A. Gabriel Esteban

Lafayette J. Ford T. Bondurant French

Alejandra Garza

Timothy J. Gilfoyle

Gregory L. Goldner

Mary Lou Gorno

David A. Gupta

Brad J. Henderson

David D. Hiller

Tobin E. Hopkins

Daniel S. Jaffee

Ronald G. Kaminski

Randye A. Kogan

Judith H. Konen

Michael J. Kupetis

Donald E. Lassere

Robert C. Lee

Ralph G. Moore

Maggie M. Morgan

Stephen Ray

Joseph Seliga

Steve Solomon

Samuel J. Tinaglia

Mark D. Trembacki

Cover: Women participate in a liberation march and rally at the Civic Center, May 15, 1971. ST-20003470-0001, Chicago Sun-Times collection, Chicago History Museum

Ali Velshi

Gail D. Ward Lawrie B. Weed Monica M. Weed Jeffrey W. Yingling Robert R. Yohanan

HONORARY LIFE TRUSTEE

The Honorable Richard M. Daley

The Honorable Rahm Emanuel

LIFE TRUSTEES

David P. Bolger

Laurence O. Booth Stanley J. Calderon John W. Croghan Patrick W. Dolan Paul H. Dykstra Michael H. Ebner Sallie L. Gaines Barbara A. Hamel M. Hill Hammock

Susan S. Higinbotham Dennis H. Holtschneider C.M. Henry W. Howell, Jr. Edgar D. Jannotta Falona Joy Barbara L. Kipper W. Paul Krauss

Josephine Louis R. Eden Martin

Josephine Baskin Minow Timothy P. Moen Potter Palmer

John W. Rowe

Jesse H. Ruiz

Gordon I. Segal

Larry Selander Paul L. Snyder

TRUSTEES EMERITUS

Catherine L. Arias

Bradford L. Ballast

Gregory J. Besio

Michelle W. Bibergal

Matthew Blakely

Paul J. Carbone, Jr.

Jonathan F. Fanton

Cynthia Greenleaf

Courtney W. Hopkins

Cheryl L. Hyman

Nena Ivon

Douglas M. Levy

Erica C. Meyer

Michael A. Nemeroff

Ebrahim S. Patel

M. Bridget Reidy

James R. Reynolds, Jr. Elizabeth D. Richter

Nancy K. Robinson

April T. Schink

Jeff Semenchuk

Kristin Noelle Smith

Margaret Snorf

Sarah D. Sprowl

Noren W. Ungaretti

Joan Werhane

*As of June 30, 2021

The Chicago History Museum acknowledges support from the Chicago Park District and the Illinois Arts Council Agency on behalf of the people of Chicago.

AsthemagazineoftheChicagoHistoryMuseum,wewantedtodedicateanissuetotheplace whereitallhappens—theMuseum.

Inthisissue,youwillgetabehind-the-sceneslookatwhathappenswhenweloananitemfromour vastcostumecollectiontoanotherinstitutionfordisplayinanexhibition.Itinvolvesmuchmorethan packingitintoaboxforshipping.CHMconservatorHollyLundbergdocumentedtheprocessof assessingthecondition,repairing,andreadyingforloanacotilliongown(1956)designedbyAnnLowe. ThedresswasondisplayatthePeabodyEssexMuseuminSalem,Massachusetts,foranexhibitionon womenwhorevolutionizedfashion.

Foundedin2005,theMuseum’sStudsTerkelCenterforOralHistorycollaborateswithcommunity partnerstopromoteoralhistoryasatoolofsocialjustice.Followingthelegacyofwell-knownauthor,historian,andbroadcasterStudsTerkel,theCenterdocumentsdiverseChicagovoices.Inrecentyears,projectshaveincludedayouthengagementcomponent,trainingmiddleandhighschoolstudentsasoral historians.Overthepastthreeyears,theCenterhascollaboratedanddevelopedprojectsrelatedtothe WestSidecommunitiesofEastGarfieldParkandNorthLawndaleaswellastheChicagoarea’sPolish andMuslimcommunities.ThoseoralhistoriesfromMuslimChicagoansbecamethefoundationforthe in-personexhibition AmericanMedina:StoriesofMuslimChicago curatedbyPeterT.Alter,theMuseum’s chiefhistoriananddirectoroftheStudsTerkelCenterforOralHistory.Thoughtheexhibitionhasclosed, Alter’sarticleinthisissuediscussesthethemesofidentity,journey,andfaiththatemergedfromtheoral historyprojectandfeaturesexcerptsfromconversationswithMuslimChicagoansthatwerenotincluded intheexhibition.

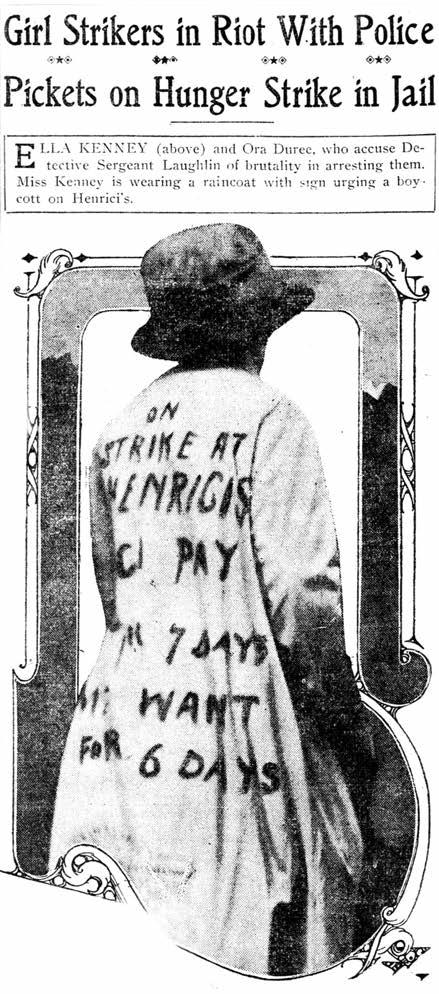

Thepastyear,withtheMuseumclosedformonthsduetotheCOVID-19pandemic,weturnedtodigitalspacestocontinuetoshareChicagostorieswithouronlineaudience,members,andfriends,aswe alladaptedtoscreensasourprimarytoolofcommunication.Ourplannedexhibition DemocracyLimited: ChicagoWomenandtheVote wassettoopeninAugust2020tomark100yearssincetheratificationof theNineteenthAmendment.AsCOVIDcasesrose,theMuseummadethedecisiontoadapttheexhibitiontoanonlineexperience(www.democracylimited.com).Ourcurator,ElizabethFraterrigo,associate professorofhistoryatLoyolaUniversityChicago,reworkedtheexhibition,andreliedonphotographs andother2-DmaterialsintheMuseum’scollectionstotellthestorynotjustofthevote,butofrecent anddistantmomentswhenChicago-areawomenmobilizedforchange,partofalonghistoryofactivism andprotest.

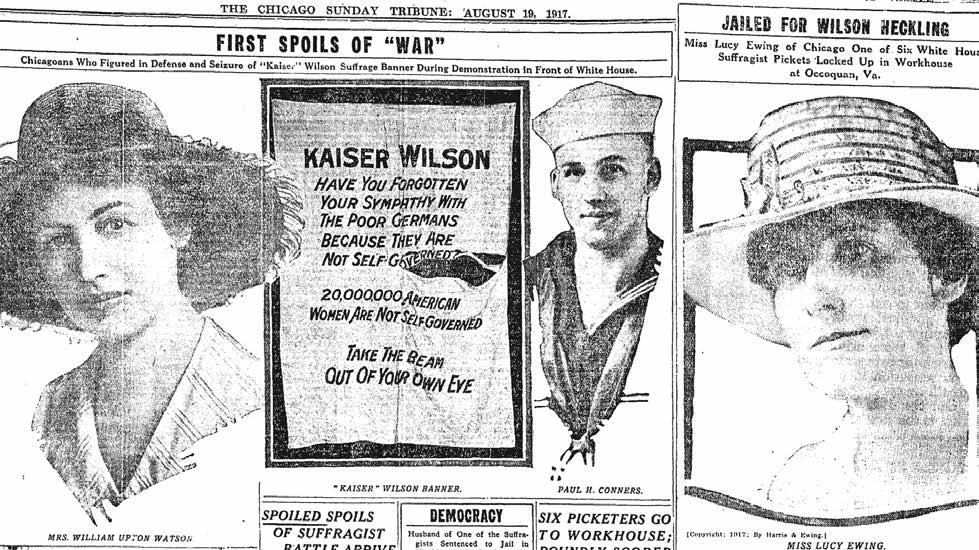

Inthenarrativefoundinthisissue,sheunpacksthecomplexstoryofhowthesuffragemovementin theChicagoareawasforgedbywomenofdifferentbackgroundsandwithdifferentmotivations.Thetitle “DemocracyLimited”wasthenicknameofatrain,boardedbyagroupofwomeninFebruary1919,to embarkonatourwheretheysharedthestoryoftheirarrestsforprotestinginsupportofafederal women’ssuffrageamendment.Althoughthesewhitewomenomittedwomenofcolorfromtheirclaims totherightsofcitizenship,theirnicknameforthetrainisareminderthattheprojectofdemocracyis diminishedwithoutfullandequalparticipationofallmembersofsociety.AlthoughtheNineteenth Amendmentdidnotgrantallwomentherighttovote,itwasstillahard-wonachievementmetwith seriousoppositionandincrementalvictoriesalongtheway.

WehopeyouenjoythisissueandthatyoulearnsomethingnotjustaboutChicagohistory,butabout theworkwedoattheMuseumtobringhistorytoyou.

The

SeewhatgoesintopreparingadressfromtheMuseum’sworld-renowned costumecollectionforloananddisplay.

HOLLYLUNDBERGItisacommonpracticeformuseumstoloanartifacts tootherinstitutions.InSpring2020,theChicago HistoryMuseumconservationteampreparedacotilliongown(1956)designedbyAnnColeLowe (1898–1981)togoonloantothePeabodyEssexMuseum inSalem,Massachusetts,fortheexhibition MadeIt:The WomenwhoRevolutionizedFashion.Inwhatfollows,learn moreaboutthegarmentandconservationprocessthat wentintopreparingthepieceforloananddisplay.

AnnLowewasoneofthefirstAfricanAmerican designerstoachievewideacclaim,andherone-of-a-kind gownsandfinehandiworkwerehighlysoughtafterby theeliteofhighsocietyfromthe1920sthroughthe 1960s.Sheisperhapsbestknownfordesigningthe iconicivorysilkweddingdresswornbyJacqueline Bouvieruponherweddingin1953tothenJunior SenatorJohnF.Kennedy,thoughLowedidnotreceive creditfortheworkatthetime.

OneofLowe’strademarksistheuseofflowermotifs inherdesigns,suchastheelegantself-fabriclong stemmedroseappliquésthatembellishthebodiceand skirtofthecotilliongown,whichwaswornbyCarole DukeDenhamonDecember22,1956,atthePassavant Cotillion(GiftofMrs.CharlesChaplin,1976.241.170). Thestraplesssilkgownhasabonedbodice,center-back zipper,andafullskirtwithanattachedunderskirtof taffeta,linedwithastiffnonwoveninterfacing-likematerialandedgedwithhorsehairatthehem.Alongwiththe floralappliqués,thegownisembellishedwithfaux pearls,sequins,glassseedbeads,andrhinestones.

Afterbeingrequestedforloan,thegownwasbrought totheconservationlabtobeassessedforcondition, treatmentneeds,recommendationsfordisplay, mounting,andhandling,aswellasforanyneededconservationtreatment.

Thegownwasfoundtobeinfairlygoodcondition. Immediatelyapparentwasdamageassociatedwithuse thatincludedsomespots,stains,andsoilingdownthe

AnnLowelabel(above)anddetailofthe flower motif on this cotillion gown skirt (left).

frontandatthehem.Inaddition,thegarmentwasheavily wrinkledandcreased,andthebloomsofLowe’strademarkfloralappliquéswereflattenedandcrushed.Acloser examinationrevealedasignificantnumberofloose sequins,beads,pearls,andrhinestones,aswellassome lossesofthesameinspotsthroughoutduetoembrittlementandbreakageoftheembroiderythreads.Someofthe leavesandafewofthestemsandflowerblossomswere alsocominglooseasaresultofbrokenstitchesandthread, especiallyaroundthehipandthighareasontheskirt.The silver-platedrhinestonesettingsandthesilveredbacking onthesew-onstoneswereblackenedbytarnish.

Thestiffunderskirt,whichhelpedtosupportand providesomeshapingfortheskirt,wasmisshapenand hadnumeroushardverticalrunningfoldsdownit.Both theouterlayeroftaffetaandtheinterfacingwerecreased, andthebandofhorsehairstitchedatthehemwasbent, foldeduponitselfinspots,andmisshapen.Ofparticular concernwasthepresenceofa9-inchlong,raggedtearin theinterfacinglayeratthebackoftheunderskirt.

Examplesoflooseandmissingbeadwork,sequins,andstonesonthegown’s bodice and loose, detaching self-fabric appliqués on the skirt.

Treatment of the cotillion gown was undertaken over the course of several months. At that time, any dust and loosely adherent dirt and particulates were removed using a lowsuction vacuum, and conservation sponges were used to reduce some of the dirt and soiling at the hem of the dress and underskirt. Loose and/or detaching floral appliqués, beads, sequins, pearls, and rhinestones were secured by stitching, using a thin cotton thread for fine embroidery

(size 60/2, i.e., 60 weight thread with 2 plies). Long, broken lengths of embroidery thread found throughout the areas of beadwork and around the appliqués were pulled through to the interior side of the dress with the aid of a sewing needle. Sew-on rhinestone rose montee beads similar to those originallyusedonthegownweresourcedandpurchasedonline to fill a 1.5"–2" long section of loss along the top edge of the bodice at the front.

Thetearintheinterfacinglayeroftheunderskirtbeforetreatment.

Aseriesoftestswereundertakentofindthemostappropriatepatchmaterialandadhesivetorepairthe9-inchtear inthethicknonwoveninterliningoftheunderskirt.Both long-fiberedJapanesetissuepapersandacoupleofdifferent nonwovenspun-bondedpolyesterfabricsofdifferent weightsweretestedfortheirsuitabilityaspatchmaterial, andseveralheat-reactivatableadhesiveswerealsotestedfor use,includingsomedilutemixturesofconservationgrade acrylicadhesives,andanadhesivefilmoriginallydeveloped forthereliningofpaintedcanvasses.Thepreparedtest

patcheswereappliedtopiecesofheavyweightPellon® sewininterfacingtotestsuitabilityonamaterialsomewhatsimilarinnaturetotheinterfacingoftheunderskirt.Ultimately, agradeofHollytex,awhitenonwovenspun-bondedpolyesterfabric,waschosenforthepatchmaterialduetoits smoothfinish,nonravelingedges,dimensionalstability,and hightensileandtearstrength,alongwithanadhesivefilm createdspecificallyforconservationapplications,asitwas foundtohavebetteradhesionandmoreappropriatepeel strengththantheotheradhesivestested.

Becausethetearintheinterfacinglayeroftheunderskirtwasragged,apatchwasappliedonbothsides.The patchontheinteriorfacewasslippedinthroughthe tear,aligned,andsecuredinplacebyreactivatingthe adhesivewithaheatspatula.Asthepatchonthe exposedexteriorsurfaceoftheinterfacingwouldbevisibletoanyoneexaminingtheinteriorofthegarment,the outerfaceoftheouterpatchwastonedwithwashesof GoldenFluidAcrylicartists’paintsandair-driedpriorto beingsecuredinplace,soastoblendmoreseamlessly withthecoloroftheinterfacing.

Left:Theset-uptorepairthetearinthe underskirtinterfacing.

Below:Here,aheatspatulaisusedto securethepatchinplace.

Close-upofthepatch-repairedtearaftertreatment.

Wrinkles,creases,andfoldsthroughoutthegown and underskirt, and the distortions and folds in the horsehair band at the hem of the underskirt were removed or reduced using a variety of localized humidification techniques, including the use of cool mist generated by an ultrasonic humidifier and isolated strips of

blotter paper misted with deionized water that were placed over areas of wrinkles and/or creases (with the misted side away from the garment) and weighted or secured in place to humidify the fibers, then allowed to reacclimatize to ambient conditions.

Blossomsonthebodicebefore(left)andaftertreatment(right).

Blossomsonskirtbefore(left)andaftertreatment(right).

Finally,theflattenedandcrushedflowerbudswere reshapedusingsmallpiecesofblottingpaperdampened withdeionizedwater,whichwerecarefullywrappedor tuckedaroundeachflowerand/orpetalforlessthana

minutetorelaxthefibers.Oncehumidified,thepetals weregentlymanipulatedbyhandtoreshape,thenleftto reacclimatizetoambientconditions.

Frontviewofthegownbefore (inset)andaftertreatment (below).

Backviewofthegownbefore (inset)andaftertreatment (below).

Whilethegownwasinthelab,itwasmeasuredand test fitted on several different forms and mannequins to find the most appropriate size for support and display purposes, and a determination was made as to what type of padding and underpinnings, such as petticoats, would be sent with the garment. After treatment was complete, a detailed condition report along with photographs, instructions for handling, dressing, and packing, and the requirements for display were written and printed up t o be packed within the travel crate along with the gown, which was carefully packed in a custom-made archival box padded out with acid-free tissue paper for the trip.

The Lowe gown was on loan from November 21, 2020, through March 14, 2021.

WithspecialthankstoNancyBuenger(conservatorinprivate practice), Sue Reif-Gill, and Julia Eckelkamp (CHM conservation volunteers) for all their help and efforts on this project.

HollyLundbergreceivedherdegreeinConservationandMaterials Science from University College London. She completed her postgraduate work in the conservation analytical labs of the Smithsonian Institution, and worked in conservation at the Field Museum of Natural History for seven years before joining the Chicago History Museum in 2005, where she specializes in the preservation, care, and conservation of materials in the Costume and Textile, Decorative and Industrial Arts, and Painting and Sculpture collections, as well as for artifacts on exhibition.

ILLUSTRATIONS |All images courtesy of Chicago History Museum staff unless otherwise noted. Page 5, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, www.loc.gov/item/96519318/.

TheChicagoMuslimOralHistoryProjectinterviewedmorethan150Muslim Chicagoansfromavarietyofbackgrounds—readtheirstoriesintheirownwords.

Theentrancetotheexhibition AmericanMedina:StoriesofMuslimChicago (October21,2019–May16,2021)attheChicago History Museum.

TohighlighttheimportanceofChicago’sreligiouscommunities,theChicagoHistory Museum,intheearly2000s,developedplans forareligioussuiteofexhibitionsfocusingon theAbrahamicfaiths—Christianity,Judaism,andIslam. CatholicChicago openedin2008.In2012,theexhibition ShalomChicago,focusingonthecity’sJewishcommunities,debuted.Sevenyearslater AmericanMedina:Stories ofMuslimChicago openedtocompletethesuite.

Unlikeitstwopredecessorexhibitions, American Medina’sfoundationwasanoralhistoryproject.Under theauspicesoftheMuseum’sStudsTerkelCenterfor OralHistory,theChicagoMuslimOralHistoryProject beganinthesummerof2016andcontinuedinto2021, gatheringmorethan150interviews.Theoralhistories, includingaudiofilesandtranscripts,willeventuallybe availablethroughtheMuseum’swebsite,asapermanent onlinearchive.Projectstaff,interns,andvolunteers

workedtointerviewabroadarrayofAmericanMuslims frommanysuburbsandthroughoutthecity.Oralhistory narratorscamefrommultiplehistoricallysignificant Muslimcommunities,aswellasnewerlesser-known ones.Peoplebornintothefaithaswellconvertssatfor interviews.Manyarenative-bornAmericanswhileothers wereimmigrantsandrefugees.Theyoungestnarrators werecollegestudentswhiletheoldestwereintheir eighties.Somevolunteeredtobeinterviewedafter hearingabouttheprojectthroughwordofmouthand othersbygoingtotheprojectwebsite.Staff,volunteers, andinternshowever,recruitedmostnarratorsthrough communityorganizations,mosques,publicmeetings, andindividualcontacts.

Foundedin2005,theMuseum’sStudsTerkelCenter forOralHistorycollaborateswithcommunitypartnersto promoteoralhistoryasatoolofsocialjustice.Through documentingeverydaypeople’svoices,thecentercarries

forward the legacy of well-known actor, disc jockey, oral historian, journalist, and writer Studs Terkel. In their approach to this project, oral history center staff applied frameworks of shared authority, reflective practice, antiracism, being trauma informed, and understanding thepitfallsofChristiannormativity.

Typically, the center’s oral history initiatives, including this project, have a youth engagement component. In spring 2019, center staff recruited, hired, and trained eight urban and suburban American Muslim high school students to conduct oral histories and work on the resulting exhibition. From April to October of that year, they led seventeen interviews, recruited oral history narrators, promoted the exhibition, and did research. The exhibition’s five-minute introductory film also featured them.

While listening to the interviews, center staff discovered that three main topics, among many others, consistently rose out of the Chicago Muslim Oral History Project: narrators discussed themes of identity, personal journeys, and faith. These three ideas became the organizationalrubricforthe AmericanMedina exhibitionand the following edited excerpted oral histories. Although each thematic section here is grounded by an interview featured in the exhibition, most of these oral histories did not appear in American Medina

Combing through more than 150 interviews to create this article was a major undertaking. Interns working with the oral history center, Michala Marcella Fitzpatrick, Miriam Montano, Sophie Ospital, Rachel Rudolph, and Andrea Serna, did a wonderful job analyzing oral history audio and transcripts to help produce this piece.

Likeanyfollowersofthesamereligion, Muslim Chicagoans share a faith but also maintain their individuality. Their varied characteristics help us better understand the city’s and country’s histories and Muslim communities.

MirzetDzubur isBosniak fromPrijedor,Bosnia. BosniaksareSouthSlavic Muslimsfromsoutheastern Europe.Dzuburfledhis country’sgenocideof Muslimsin1995with histwosonsandwife. Soonaftertheirarrivalin Chicago,hefoundedKUD “Bosna”Chicago,aBosniak youthdancetroupe.

PhotographbySadafSyedPhotography

Whenwecame,itwasMay23,1995.They[arefugee resettlementagency]foundforusanapartment.It wasonebedroomandthebasicsofwhatwe needed,abed...food.Wewerehappy.Andwevisited WorldRelief,andwefollowedtheirprogram.Afterone month,Iestablishedthat[adancetroupe]withafew teenagers.Thiswasgoodformeatthattimebecause— insidewehavealotoftrauma....Thatisagoodtimeforme togotothat[dancetroupepracticesandperformances]....

Doingsomethingwiththekids,teenagers,andme,it wasmytherapyandforthekids,andforeverybodyinthe [Bosniak]community,andthat’smypoint....From1995 totoday,ithasbeenover500kids,members,through generationtogeneration.Tostartitwasnoteasy.Itwas noteasybecausewedidnothavecostumesorinstruments.Wehadnothing.Ijustclappedlikethistostartin therefugeecenter—Bosniakrefugeecenter—near SheridanandBroadway[ontheNorthSide].

Aisha Ibrahim-Hanson is from Chicago and grew up on the South Side. She currently lives in northern California where she works astheconvertcarecoordinator for Ta’leef Collective. Ta’leef also has a Chicago presence and creates “the space, content, and companionship necessary for a healthy understanding and realization of Islam.”

Ithinkmyexperiencewasincrediblyuniqueina coupleofways.One,growingupI’dneverreally thoughtaboutraceattachedtoreligion,meaning therewasnoimmigrantexperiencethatIhadtokindof navigatebeinginthiscountryasalotofmypeersdid. Theyhadtodealwithnavigatinganenvironmentthat theygrewupin,whichwouldbetheWestandAmerica, butthenhavetodealwithimmigration,thingsathome... justdifferentculturalthings.

IwouldsaythatmyculturewasIslam,whichisreally interestingbecauseIslamisareligion.It’snotaculture, right?Butbeingthatmyparentsconverted,allweknew wasIslam.Therewasnothingelse.Therewasno,“Our Italiansidedoesthis,orourBlacksidedoesthis.”My parentsmadeaveryintentionalefforttoraiseallofusin theIslamiclifestyle.So,whenIsayculture,Imeansynonymouswithlifestyle.AndIlearnedthatthatwaskind ofdifferentformypeersathighschool.

BorninLahore,Pakistan, TayyabaSyed cametothe UnitedStatesinthe1980s withherfamily.Whenher familygottotheChicago area,theyfirstlivedinthe cityandthenmovedtosouthwestsuburbanWestmont. Today,Syedisanaward-winningauthor,journalist, keynotespeaker,andperformer.Sheisalsoamember oftheGlenEllyn,Illinois District41schoolboard,as “thefirstMuslimtoever serve”inthiscapacity.

Itcomesdowntoacceptingouridentityofwhowe are.Ididnotgrowupwearingtheheadscarf.I startedpracticinghijabasasophomoreincollegeat theUniversityofIllinoisatChicago.Iactuallygrewup

very detached from my faith. We grew up in the culture. There are principles that overlap between the culture and the religion. Sometimes, things are confused. It wasn’t like the religion was forced upon us. I grew up confused as to what is culture and what is religion.

Itwasn’tuntilItookabunchofworldreligion courses, philosophy courses, humanities courses, and sociology courses, where I studied everybody else, that I learned to appreciate who I was. I think that is what it comes down to. When I put the scarf on my head, I am declaring that I am a Muslim. When I was growing up, I never fit in anyway. It didn’t matter if I was covered or not covered. I still didn’t look like everybody else. That was one of the defining factors for me to start wearing the scarf. Well, I am already different. Who cares? Now, it is a testimony of my faith.

YvonneMaffei,anativeof Lorain,Ohio,andalongtimeChicagoresident,runs thepopularfoodblogMy HalalKitchen.Shedescribes herselfas“halfSicilianand halfPuertoRican,butall MidwestAmerican.”After convertingtoIslaminher 20s,Maffeiexploredhowto cookfamiliarfoodsfollowing Halaldietaryguidelines.

Ihadbiglessonstolearnthereaboutthemeaningof Halal.Icouldembracethenewreligion—andIslam doesn’ttellyoutodropyourculture—butIneeded tocommunicatemyselfalotbettertothepeopleI caredaboutandwhowereabittakenabackaboutmy decision.Foodwasthatcommunicationvehicleand somethingthatbroughtustogetherandcloser.Over theyears,Ihadtogetbetteratthat,soIstartedto thinkaboutmakingmoreItalianfoodwithHalalingredients,aswellasPuertoRicandishesandall-American foodtoo.

ThesearethethreeculturesIamingrainedinand meanalottome,soIwantedtobesuretorespectand preservemypersonalculinaryheritage.Whenmyfamily comestovisitme,theydon’twantsomethinginnovative orfancy.Theyjustwantcomfortfood.BecauseIspent yearstestingandtasting,Icannowmakeourtraditional foodswithHalalmeat,and,luckily,theyarehappyto enjoyitwithmetoo.Theflavorsarefamiliartothem, andeverybodyishappy.ThatiswhereIfoundmyhappy medium,andIsawagapinthemarket....

HalalisanArabicwordthatmeanspermissibleinthe contextofIslam.Itmeansmorethanwhatispermissible toeat.Itisalsowhatispermissibleinactions,societal

norms, financial transactions, for example. The opposite is Haram, but I just like to focus on what is permissible, because there is a huge abundance of Halal in terms of food. It is really so delicious!

OriginallyfromIstanbul, Turkey, SerpilCaputlu cametoChicagoin2004. Currently,sheisamathematicsinstructoratTriton Collegeinthewesternsuburbs.Caputludiscussedthe challengessheovercameto besuccessful.

Rightafterourmarriage,IcameheretotheU.S.A. [withmyhusband].Everythingwasnewforme,of course.Iwastwenty-twoyearsold,justfinished college.Itwasabigtransitionforme...Istillstarted goingtocollegehere,andIwashelpingmyfriendwith newspaperdeliveries.

Istartedgoingtochurchesinmyneighborhood. Thereweresomevolunteerteachersthere.Theywere verynicetome,teachingmeEnglish.Tobehonest,I didn’thaveahardtimepracticingmyreligionasa Muslimhere.Ifeltlikeeverybodywassorespectful.I wasabletodonewspaperdeliveryuntilIhadmy[first] baby.Assoonashewasborn,myhusbandgotajob offerinChicago.

WhenImovedtoChicago,Iwasabletostartcommunitycollegepart-time.Then,Igotafullloadofclasses andbecameaninternationalstudent.Istartedajobasa nanny.Itookmysonwithmeandtookcareofother kidswithhim—thathelpedmepaymytuition—Ifinishedmymaster’sdegree[inmathematics].Ialreadyhad abachelor’sdegreeinphysicsbeforeIcamehere.Iwas workingabouttenhourseveryday.Intheevening,Iwas leavingmysontomyhusbandwhenhecamehome fromwork.Iwouldthenleaveformynightclasses.

Iwasverybusy,butIwashappybecauseIwasable toearnmoney,paymytuition,andcompletemyeducation.Igotmygreencardandworkpermission.Right afterIfinishedmymaster’sdegree,Istartedtoworkat differentcommunitycolleges—TrumanCollege,Triton College—havingthreepart-timejobswaslikehavinga full-timejob.

IappliedtoTritonCollegeasfull-timefaculty.After ...threeyears,Iwasabletogetmytenure[atTriton].I alsoworkatDePaulUniversitybecauseIliketobebusy. [Now,]Ihavetwokids—itwasespeciallyhardforme duringmy[second]pregnancybecauseIwasworkingat thesametime.Icontinuedteachinguntilthenight beforeIhadthebaby,andthenIwentbacktoworktwo weeksaftergivingbirth.

Diana Cruz was raised in Chicago’s Little Village community on the city’s Near Southwest Side. She commented that her “upbringing wasintheMexicanculture, but my mom did not want me to lose my Puerto Rican culture.” The Teen Historians, who interviewed Cruz, asked her: “When you first converted in 1999 as a Latino Muslim, what resources did you have?”

IwasintroducedbyafriendofminetoaLatino Muslim.Tomeitwaslike,“HowcanyoubeLatino andMuslim?Youneedtotellmemore.”Hewasmy connectiontolearningmoreaboutIslam.Hewasthe onewhosaid,“YoucanconverttoIslam.Islamisuniversal.”

IdidnotwanttolosemyidentityasaLatina.Tome, itshapedmetobelike,“IamMuslim,butIamalso Latina.”IstartedmakingitapointtodoLatinoEid eventswithotherpeople.Westartedgettingtogetherand starteddoingLatinoEid[twoyearlyfeastdaysfor Muslims]events,LatinoEidparties....Now,thereisa hugeconversionofLatinos.Thereareconversionclasses fornewconverts.Whenyouconvert,thereareamajority ofLatinoswhospeakSpanishandareabletoassistthose whospeakSpanish.Backintheday,whenIstarted, therewasnoneofthat.

Journeys,bothphysicalandspiritual, are an important part of religious faith. For well over a century, thousands of Muslims have started, ended, or undertaken their journeys in Chicago as residents, migrants, immigrants, refugees, and converts.

AsaRohingyainBurma, NorjahanBintiFozarahman facedviolentpersecution. TheBurmesegovernment doesnotrecognizethe Rohingyaasadistinctethnic group,willnotacknowledge themasMuslims,orgrant themcitizenship.Theyare stateless.Asarefugee,she enduredalong,tortuous passagethroughThailand andMalaysiabeforearrivinginChicago.Shespokeinher nativeRohingyawhilehersontranslated PhotographbySadafSyedPhotography

Thestyleofthishand-embroideredgirl'sdress(c.2005)comesfrom Medculii, a village in Afghanistan, while the mirrors on the garment are a common feature of Pashtun clothing.

ShewassayingthereasonsheleftMalaysiaisshe thoughtaboutherchildren’sfuture.Becausein Malaysiawhenyourchildrendon’thaveaneducation,peopleusedtosaythatthey’regoingtobewild.So shedidn’twantherchildrentobelikethat.Shewanted

her children to have a good future. She wanted her children to be good people in the future. And she thinks about that, and it’s hard in Malaysia.

She said we don’t have a country. We need a country. We are still refugees. But we need a country that we can goanywherewewant,wherewehavefreedomofmovement, freedom of speech. She thought about that. And then she went and applied to the UNHCR [United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees in Malaysia], and the UNHCR eventually brought her over here [to the city’s North Side].

Originally from Houston, Texas, TrentonCarl came toChicagoin2009to attendDePaulUniversity andmajorinIslamicstudies. Hegrewupwithafather“of Anglo-Americandescent” andamotherwho“is[of] Mexican[descent].”Carl convertedtoIslamin2006 andfoundcommunityat DePaulUniversity.

WhenImovedtoChicago,Ididn’tcomewitha car,andsomyworldwasbasicallyfrom Ravenswood[aNorthSideneighborhoodnear DePaul’smaincampus]todowntown.Thatwasmy world.AndsomycommunitywastheMSA[Muslim StudentsAssociation]community.SoIreachedoutto DePaul’sUMMA,UnitedMuslimsMovingAhead— that’stheirMSAprogram—beforeImovedandsaid, “Look,I’mmovingtoChicago.I’dliketogetinvolvedin yourcommunityspace.”

SothepresidentofUMMAatthetimeandIbegan emailing,andwekindofclickedreallywell.Hecreateda positionforme,makingmethehistorian.IwasimmediatelyputontheboardwhenImoved,andwithinsix monthsorsohehadaskedmetostartleadingsomeprogramsattheMSA.TheMSAspacewasofsuperimportanceformeinthosetwoyearsatDePaul.That’swhere mycommunitywas.That’swheremyfriendswere. That’swheremyintellectualactivitywas,myspiritual activitywas.

A native of Rafah, Palestine, MohamedElnatour discusseshisjourneyto ChicagofromSaudiArabia in1991.Heiscurrently the principal of the Islamic Community Center of Illinois Academy in Chicago.

PhotographbySadafSyedPhotography

PhotographbySadafSyedPhotography

IcametoChicagowith mywifeandmytwo children.NowIhaveeightchildren.TheonlypeopleI haveintheUnitedStatesaremyownchildrenand grandchildren.Someofmykidsaremarried,andthey havechildren.SonowIamagrandfather.Ihaveno brother,nocousins,nosistersintheUnitedStates.Itis veryraretofindPalestiniansfromGazaoutside[of Palestine],becausethepeopleinGazadonothavethe privilegeofhavingavisa.

Thereisnocounselor,norepresentativeforanystate togivevisasforanypeopletogooutsideofGaza.Thatis whyIcameherefromSaudiArabia.Iwasateacherover there.IappliedtotheAmericanEmbassytogetaF-1 Visaasastudenttobecomeagraduatestudent.Thatis howIgethere.IfI’minGaza,Iwouldnothavethiskind ofprivilegetocometotheUS,asthemajorityofthe peopleofGazacan’tgetherenow.

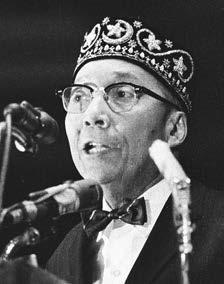

BashirAsad isaChicago nativewhosefamilyhails fromMobile,Alabama. In1968,heandhiswife, Na’Imah,joinedthe Chicago-basedNation ofIslam(NOI).With teachingsbasedonthe Quran,theBible,andBlack nationalism,long-timeNOI leadertheHonorableElijah Muhammadbuiltitintoa majorreligious,cultural, business,andpoliticalforce, challengingwhitesupremacy andpromotingIslamasan alternativereligionfor AfricanAmericans.

LeaderoftheNationofIslam, Elijah Muhammad, speaks at the Saviours’ Day annual meeting, February 26, 1966.

UponthedeathoftheHonorableElijahMuhammadin 1975, Asadandhisfamily,likemanyothermembersofthe NOI,transitionedtotheleadershipofImamW.D. Mohammed,ElijahMuhammad’sson.ImamMohammed leadthemembershipinanotherdirection,includingadherencetothedictatesoftheQuranandthelifeexampleofthe ProphetMuhammad.Thispathhadalreadybeenindicated

in the Honorable Elijah Muhammad’s teachings that it would be the direction of the future of the NOI. Imam Mohammed’s goal was to move members closer to the universal principles of “Al Islam.”

Itell people today one of the things that impressed me the most, when I attended my first [Nation of Islam] Saviours’ Day event, was the well-organized conduct of the people, neatly dressed—even the children. I can remember looking at the children and how organized and mannerable and courteous they were. I said, “This is where I want to be.” These are the kind of people I want to be a part of.

They were progressive. They had an economic program. They put importance on education. One of the things that the Honorable Elijah Muhammad and his message stressed was “that you will not be equal to the white man until you have equal education.” It was practical things like that. Although other African Americans were saying similar things, it was the emphasis on self-reliance, Do For Self, that attracted me to the Nation of Islam at that time. The Honorable Elijah Muhammad asked the African American community “Why ask another people to do for you what you can do for yourself?”

AbdulMallickAjani, whocurrentlyworksata majorinsurancecompany insuburbanNorthbrook, discussedhisjourneys fromEastPakistanto WestPakistanandthento Chicago.Sincehisarrival inChicago,hehasbeen associatedwithhisreligious communitycenter,volunteeringtheresince1972. Overtheyears,hehashad manyrolesandcurrently servesasamediator.

Afterthe1971civilwar,myfamilyandImigratedto WestPakistan[moderndayPakistan]andstarted workingthere[aftermovingfromEastPakistan, moderndayBangladesh].Thatperiodwasabitdifficult. Iwouldgotoschoolintheeveningandworkduringthe daytime.Itwasabigadjustmentfromthelifethatwe hadinEastPakistan.InWestPakistan,also,whileIwas there,theschooling,attimes,wasirregular.Ihadtalked withsomeofmyfriendswhohadcometotheUnited StatesandtoChicago...

Then,myfamilydecidedthatitmaynotbeabadidea formetocomeovertotheUnitedStates,particularlyto Chicago[in1972].Theonlyreasonofmycomingto

ChicagowasIhadthreeorfourfriendsherewhohad comeoveraboutsixmonthsbeforeIdid.AndIdidnot knowanyoneelseanywherebesidesChicago.Thetalkin myfamily,then,wasthatifIknewsomebodyinthe UnitedStates,andtheyareinChicago,itwillhelpme settleabiteasierthanifIwenttoaplacewhereIdidnot knowanyone.Myparentsandmyothersiblingsstayed in[West]Pakistanforawhilebeforetheyalsomovedto theUnitedStates.

KhalilRasheed has livedthroughoutthecity, includingintheNorthSide Uptownneighborhoodwhere heinteractedwithdiverse Muslimcommunities. He’scurrentlyagraduate studentatNortheastern IllinoisUniversitystudying politicalscienceandinternationalrelations.

IalwaysquestionedthingswhenIwasyoung.And thosequestionsreallydrovemetoresearchand inquiremoreaboutGodandspirituality.Iaccepted Islamofficially,wesaytake shahada [theIslamicprofessionoffaith],inthesummerof’95.Istartedresearching andstudyingthereligionprobablyataboutage11[in 1992],soIgotintroducedtoit,ifyouwill,through MalcolmXandhisautobiography.IrememberIwasat McCorkle[ElementarySchoolontheSouthSide],and thereweren’tenoughbookstogoaround.

Andsomymom,becauseIwasslackingonsome homework,foughtformetohaveaccesstothebooksin mysocialstudiesclass,andMalcolmXwasoneofthem. SoIhadtodoabookreport.Atthesametime,the [MalcolmX]moviecameout[in1992].AndIdidn’tget achancetoseethemovieuntillater.ButIwasintroducedtoanotherfaithoutsideofthereligionof Christianity.Istartedopeningupmyeyesandjusttrying tograbbooks—andanything.Iresearchedsome Buddhism,Islam,Christianity,youknow,different aspectsofdifferentspiritualties.Iwasalreadykindof callingmyselfMuslim—bytheageof11or12.Ihad stoppedeatingporkandgottenaccustomedtosomeof thetraditionsandpractices.

Theword“Islam”meanstosubmitor surrender to Allah (God) in Arabic, which is the language of the Muslim holy book, the Quran. For Muslims, this takes many forms, from worship and prayer to living their faith in their daily lives. Understanding how Muslim Chicagoans live their faith is key to seeing their places in Chicago’s history.

JumanaAl-Qawasmi foundedWataninsouthwest suburbanOrlandPark. WatanisaPalestine-inspired artsshopthatprovidesa spaceforPalestiniansto exploretheirculturaland intellectualheritage.Inthis excerpt,shementions Ramadan,whichisthe ninthmonthoftheHijri (Islamiclunar)calendar.Duringthismonth,theQuranwas firstrevealedtoMuhammad,Allah’s[God’s]prophet.Itis

the holiest month of the year in which Muslims observe a daily fast from sunrise to sunset

Photograph by Sadaf Syed Photography

Insteadofcontinuingwhatmasscultureencouragesin us, materialism, consumerism, capitalism, every other -ism, how I think of Islam [is] there are these vices out there. They exist. What is in your will that is trained by Ramadan, trained by your religion that you can hold yourself back and go, “No I don’t need that.”

To be that same thing where I see that Muslim identity portrayed through that, where I see that I can make money so easily doing whatever I want to do and creating whatever art I want to. Is that ethical, like is that Halal? Haram? I think more about Halal and Haram in terms of capitalism, racism, whatever it is. That’s what I’m more interested in.

YusefTrice ownsandoperatesDawahOilPalaceon thecity’sWestSide.Whennaminghisbusiness,Trice tookinspirationfromMasjid[Mosque]Dawah,alongstandingWestSidemosque.Herehedescribesthesense ofcommunityatMasjidDawahandanswersthequestion: Whatdoesyourfaithmeantoyou?Everyoralhistory interviewconcludedwiththisquestion.

WhenIgotthere[MasjidDawah],itwasafeeling ofgenuinewarmthandbrotherhood.Youcould gettheassistance,thehelp,thatyouneeded. MasjidDawahhasalwaysbeenpivotal,Ibelieve,in helpingpeopletoreconstructtheirlivesandprovidingthe helpthatisneeded....Whatdoesthefaithmeantome? Itisthevery—Ithinkwithoutit—wow—Iwouldn’teven behere.MyfaithisthereasonwhyI’msittingheretoday.

Based in Chicago, HodaKatebi isanIranianAmericanwriter,abolitionist organizer,and“creative educator.”Hereshe responded to the Teen Historians’ question: What does your faith mean to you?

likethisquestion.My faithiscentraltomy senseofselfaswellas myrelationshiptotheworldandthepeoplewithinit. Andofcoursethathaschangedovertime,asIcontinue tolearnandgrow.Today,Islam—andparticularlywithina ShiaMuslimlens—isthecornerstoneofwhatguidesme throughouttheremainderofmyshorttimehereonEarth.

Forme,Islamisablueprintthatprovidesanoutline ofvalues—suchasadeepcommitmenttofightingfor justiceandpracticingdivinemercyandcompassion,as wellasthephysicalpracticesanddisciplines,suchas prayingfivetimesadayorfastingduringRamadanthat helpscultivateandnourishourlives,holistically.

NativeChicagoan ConstanceShabazz discussedthetransformative powerofreading The Autobiographyof MalcolmX inthe1960s. In2020,Shabazzfounded theSalaamCommunity WellnessCenterinthe Woodlawncommunity ontheSouthSide.

Oneday,mydadcameuptome,andhehandsme thisbook.Hesaid,“Ithinkyoumightwantto readthis”orsomethingalongthatline.I’m thinking,“Whatisthis?”Thebookwas TheAutobiography ofMalcolmX.Ijustsaid,“Okay.”

Bythen,IhadstartedreadingbooksaboutAfrican history,AfricanAmericanhistory.Buttogetthatone fromhimIwasthinking,“Okay,”neveranydiscussion, during,after,noquestionaboutit.Ijustfeellikeitwasa signfromGod,“Readthisbook.”

WhenIreadit,thethingthatgotmewasnotthetheologyoftheNationofIslam.Ikindofknewthatalready. ButwhatgotmewasMalcolm’stransformation— humantransformationstory.Andthat’swhereIwas, becauseIwaslookingtogotothatnextstep,measa humanbeing.

IHalilDemir wasbornintoaKurdishfamilyinsoutheasternTurkey.HefoundedtheZakatFoundationof America,locatedinsouthwestsuburbanBridgeview,in 2001.

Isawmyselfhavingalotofquestions.Islamwas,for me,answeringthesequestions.Religionwasaquestionforme.Iwaslookingforequality,soIslamsays thereisnodifferencesbetweenwhiteorBlack,you know,betweenwealthyorpoor,betweenTurkandKurd, orArabsandPersians,soforthandsoon...

IfindoutthatIslamaddressestheraceissue,social justiceissue—IfindoutthatIslamaddressesthese issues.Youcannotoppresspeople,andyoudon’twant tobeoppressed,sodenyorrejectanythingtotalitarianor oppressinganyindividualinanyaspectoftheirlives.So Islamdeniedallthese.Islamgivesfreedom.Thereligion gavethefullfreedomforhumanbeings.BefreeasGod hascreatedyou.

OlaseniQuadriShehu isa QuranicandArabicteacher livinginthesouthsuburbs. HehasanextensiveeducationinIslamic,Arabic, andreligiousstudiesinhis homelandNigeria,where hewasborninthecityof Ibadan.HecametoChicago inthe2000s.Amongmany othertopics,hediscussedhis Quranicteachingphilosophy.

ThewayIbreakdowntheQuranpeoplesay,“Ah,it’s verysimple.”Don’tchasepeople.Don’tmakeittoo hard.“Ah,it’ssohard.”No,nothinglikethat.The bookofGodmustbesomethingthatchildrencan understand.It’snotsomethingthatisdifficult.Don’t touchit,don’ttouchit,no,no,no.Don’tmakeitsupervisedlikethat.

You have to respect the book of God—respect it. But don’t make people be afraid or scare them. Even if they are scared, talk to them. It’s not scary. Teach a Christian the Quran. Teach them Quran. You are not converting them.

CraigTurner (Brother Hasan)fromMasjid [Mosque]Al-Ihsanin Bronzevilleonthecity’s SouthSidedescribesthe diversityofthemosque’s FridayJumu’ahservices.

ehaveabeautiful community[Masjid Al-Ihsan],verydiverse.WhenIsaycommunity,Idon’tmeaninaconventionalsense—localitydefinedbydemographicsorarea.I lookatitinabroadersense.Theword,“community,” comeinunity.Thosewhocometothemasjidareunited inthisworshipofoneGod.Wehaveoneofthemost diversecommunitiesthatyouwillfind,notjustinthe cityofChicagobutthroughouttheUnitedStatesof America.

At our Friday Jumu’ah services, you have South Asians. You have the Arabs. You have the African immigrants. You have the African American converts. You have the Hispanic converts. It is just beautiful. Our community, our Jumu’ah, defines how Allah(God) loves wonderousvariety.

PeterT.AlteristheMuseum’schiefhistoriananddirectorofthe StudsTerkelCenterforOralHistory.HeledtheChicagoMuslim OralHistoryProjectandcuratedtheexhibition, American Medina:StoriesofMuslimChicago.

WADDITIONALRESOURCES | Watchthefive-minute introductoryvideototheexhibition AmericanMedina:Storiesof MuslimChicago atbit.ly/medinavideo.ReadthecurrentlyavailabletranscriptsfromtheChicagoMuslimOralHistoryProject atbit.ly /medinatranscripts.VisittheChicagoHistory Museum’sSoundCloudpagetohearinterviewsandclipsfrom a selection of the narrators at https://soundcloud.com/chicago museum/sets/american-medina.

ILLUSTRATIONS | Allimagesofcourtesyofnarratorsor Chicago History Museum staff unless otherwise noted. Page 17 (bottom right), ST-19031786-0025, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM.

Explorewomen’sactivisminChicagotosecuretherighttovote—andbeyond.

OnFebruary12,1869,NaomiTalberttookthe platformbeforeapackedassemblyat Chicago’sLibraryHall,locatedatthecorner ofLaSalleandRandolphStreets,andmadea stirringappealfortherighttovote.Claimingtospeakon behalfoffellowBlackwomenofChicagoandIllinois,she expressedhopethatopponentsof“universalsuffrage” withoutbarriersofraceorsexwouldsoon“fleeaschaff beforethewind.”“OurGodiswithusandforus,and willhearthecallofwoman,”Talbertproclaimed,“andher rightswillbegranted,andshewillbepermittedtovote.”1

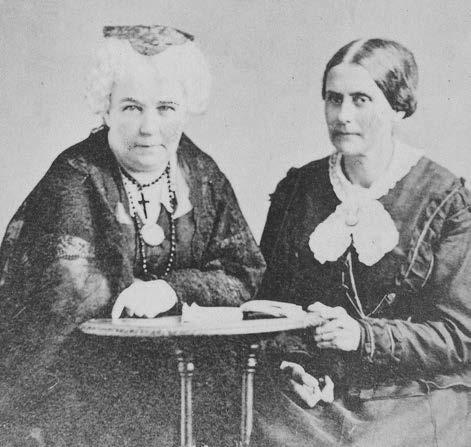

Talbert’sremarksatthetwo-daywomen’srightsconventioncameatapivotalmomentinthenation’shistory whencitizenshipandvotingrightswerebeingdebated anddefinedduringthetumultuousperiodaftertheCivil War.ChicagoansgatheredatLibraryHallasCongressconsideredpassageoftheFifteenthAmendmenttobarstates fromdenyingvotingrightsbasedonrace.Alreadythe FourteenthAmendmenthadextendedcitizenshipto AfricanAmericansandpromisedequalprotectionunder thelaw.ForAfricanAmericans,forgingfreedominthisera requirednotonlytheendofenslavement,butalsoaccess toeducationandeconomicopportunity,civilrights,politicalparticipation,andprotectionfromracialviolence. Some,suchaswhiteEasternsuffragistsSusanB.Anthony andElizabethCadyStanton,whohadtraveledtoChicago toattendtheLibraryHallandothermidwesternconventions,criticizedthependingamendmentforfailingto expandthevotetowomen.Butmanyotherssawan immediateneedtosecurethevoteforAfricanAmerican meninordertosafeguardfreedomforformerlyenslaved peopleintheSouth.AlthoughtheFifteenthAmendment heldnopromiseofenfranchisingwomen,aprimarygoal ofthosegatheredatLibraryHallwastocraftastrategyfor ensuringthatwomen’srights,includingsuffrage,wouldbe includedinanewstateconstitution,plansforwhichhad beenannouncedonlymonthsearlier.

IftheLibraryHallmeetingprovidesaglimpseofa momentthatgaveparticipantshopeforchange,italso

AsRosalynTerborg-Penn pointedoutinherseminal work, AfricanAmerican Women in the Struggle for the Vote, 1850-1920 , which recovered the voices of Black suffragists, the perspectives and experiences of Black activist women were left out of many early accounts by white authors. Reporting on the Library Hall proceedings in their newspaper, The Revolution, Anthony and Stanton acknowledged Naomi Talbert Anderson’s vocal support for universal suffrage, but they did not identify her by name. Instead, her remarks appeared under the headline: “A Colored Woman’s Voice.”

providesinsightintothemesthatcharacterizedthelong strugglebyChicagoareawomentosecuretherightto vote.Likesupportersofwomen’ssuffrageelsewhere, manyattheChicagogatheringtookpartinmovements forabolitionandtemperance.Likewise,suffragewasnota singlegoal,butratheranissueboundupinbroaderaspirationsandactivismshapedbythelivedexperiencesand circumstancesofwomenwhosoughtthevote.Aswas alsothecaseinthelargerstruggle,thosewhocame togetheratLibraryHalladvancedavarietyofarguments forwomen’ssuffrage.Whitewomenwhoorganizedthe conventionsuchasMaryLivermoreandMyraBradwell wereintentonchallengingthelawsandcustomsthat keptthemsubordinatedtomen.Talbert’ssuffrageactivism emergedfromherunderstanding,groundedinlivedexperience,thatracialoppression,gender,andeconomic statuswereintertwined.Followingtheconvention,Talbert reiteratedherviewsinalettertothe ChicagoTribune There,shecounteredgenderedantisuffragearguments

that voting imperiled femininity by alluding to far graver threats and abuses historically endured by Black women. She acknowledged the economic conditions of Black women’s lives and the necessity of Black women’s work. She tied women’s suffrage to racial advancement and calleduponBlackmenforsupport,concluding,“ifyou want to overcome prejudice, you must undertake the broad platform of universal suffrage.”2

Asinthebroadermovement,issuesofracepermeated discussionsduringtheLibraryHallconvention.After decadesfightingforwomen’srights,StantongrewfrustratedthattheFifteenthAmendmentwouldenfranchise Blackmenaheadofwhitewomen.Inhereffortsto garnersupportforherviews,sheadvancedracistargumentsthatquestionedthefitnessofAfricanAmerican andimmigrantmentovote.Sheimploredthegathering to“thinkofPatrickandSambo,andHansandYung Tung...whocannotreadtheDeclarationof Independence...makinglawsfor...SusanB. Anthony.”StantonandAnthonyalsoproposedaresolutionthatintheprocessofdenouncing“manhoodsuffrage”alsoinvokedthespecterofBlackmen’ssexual

predation of white women, should the former be empowered while women were left without the ballot. 3

ThemenandwomengatheredinChicagorefusedto endorsethisresolution.ButStantonwouldcontinueto repeatthesestatementsonceCongresspassedthe Fifteenth Amendment later that month and the campaign for ratification got underway.

These post-Civil War discussions of suffrage also occurred as immigration, US expansion, and ideas of racial hierarchy fueled debates over fitness for citizenship and participation in democracy. Only a week before the Library Hall convention, the Chicago-based labor weekly The Workingman’s Advocate warned of legions of Chinese workers on the west coast and called upon government to “forbid another [Chinese worker] to set foot upon our shores.” 4 Inthe1870s,racisttropesaboutChinese laborersundercuttingwhiteworkingmen’swagesfueled violentattacksagainstChinesecommunitiesandpassage oftheChineseExclusionActin1882.Thelaw,which barredimmigrationandnaturalizedcitizenship,was eventuallyextendedtoincludeallAsianimmigrants. Duringthesesameyears,settlerscontinuedtostream

Evenasthewomen’srightsconventiontookplaceatLibraryHall,asplintergroupledbyDeliaWatermanandCynthiaLeonardofthe

InChicago,SusanB.Anthony(left)andElizabethCadyStanton criticized the Fifteenth Amendment pending passage by Congress for failing to include women. In May, they severed from longtime abolitionist allies. That split resulted in the formation of two separate women’s suffrage organizations, which remained apart until 1890. Stanton and Anthony formed the National Woman Suffrage Association in 1869 and continued working for a federal women’s suffrage amendment.

intotheTrans-Mississippiwest,spurredbyfederalpoliciestopromotelandownership,railroads,andcommercialdevelopment.CommissionerofIndianAffairs FrancesWalkerdescribedtheimpactofthismovement onNativepeoplesinhis1872report:“Thewestward courseofpopulationisneithertobedeniednordelayed forthesakeofalltheIndiansthatevercalledthis countrytheirhome.Theymusteitheryieldorperish.”5 Overthenexttwodecades,asIndigenouspeoples resistedthisencroachment,theUSwagedwaragainst themwhileundertakingpoliciesaimedatdispossessing Nativepeoplesoftheirlandsanderadicatingtheirways oflife,includingconferringUScitizenshipuponthose whogaveuptribalpractices.

Thelongstruggleforwomen’ssuffragewouldplayout amidcontestationoverboundariesofinclusionand exclusionintothenextcentury.InChicago,women’s struggleforvotingrightswasshapedbylocalindividuals andcircumstanceswhilealsoconnectedtobroader forcesanddevelopmentsnationwide.Thecityandits inhabitantsplayedactiverolesbothintheachievement oflocalvictoriesandininfluencingthecourseofalarger movementthatresultedintheadditionofthe NineteenthAmendmenttotheUSConstitutionin1920, whichprohibitedstatesfromdenyingthevote“on accountofsex.”

OnSunday,October19,1879, NativeAmericanactivistSusette LaFlescheorInshata-Theumba (Omaha),informedtheaudiencegatheredatChicago’s SecondPresbyterianChurch (Twenty-SecondandMichigan) abouttheUSgovernment’s mistreatmentofthePonca people.Forciblyrelocatedto “IndianTerritory,”agroupled byStandingBear,aPonca chief,waslaterimprisonedfortryingtoreturntotheirancestral homelandinNebraska.StandingBearsuccessfullychallengedthis imprisonmentincourt,withLaFlescheinterpretingonhisbehalf. Afterward,shetraveledthecountryadvocatingforNativeAmerican rights,includinglandrights,citizenship,andequalrights.

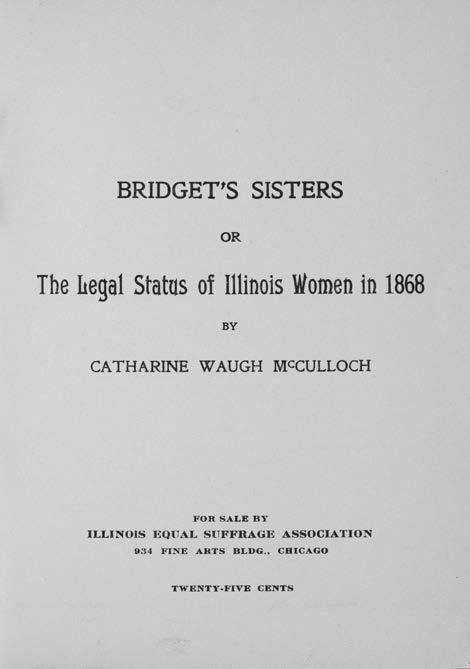

InChicago,participantsoftheLibraryHallconvention passedresolutionsinfavorofequaleducationand employmentopportunitiesforwomenandremovalof legalbarrierstowomen’sfullparticipationin“socialcivil, andpoliticallife.”Theyalsocommitted“tomakeaunited efforttohavethenewconstitutionforthestateofIllinois soframedthatnodistinctionshallbemadeamongcitizensintheexerciseofsuffrageonaccountofrace,color, sex,nativity,property,education,orcreed.”6 Taskedwith lobbyingforthesegoalsweremembersoftheneworganizationthatemergedfromtheLibraryHallmeeting,the IllinoisWomanSuffrageAssociation(IWSA),laterknown astheIllinoisEqualSuffrageAssociation(IESA).Chicago womenplayedmajorrolesinthisgroup,whichbattled forwomen’ssuffrageuntil1920.

Althoughtheprospectofanewstateconstitution inspiredoptimism,theoutcomeproveddisappointing. Electeddelegates—eighty-fivemenfromaroundthe state—convenedtodraftthenewdocumenton December13,1869.ByApril,theywerereadytodecide onthematterofvotingrights.Bythen,theFifteenth AmendmenthadbeenaddedtotheUSConstitution,but somedelegatesneverthelessusedtheoccasiontoexpress oppositiontoitsenfranchisementofBlackmenandits potentialtoextendvotingrightstoChineseimmigrants. Women’ssuffragereceivedlittlebacking,andindeed muchderision,fromdelegates.Inanerawhenahusband’svotewaswidelybelievedtoadequatelyrepresent theinterestsofhiswifeandchildren,onedelegateinterrupteddebatesbyjestingthatnationallyprominentsuffragistAnnaDickinsonlackedpoliticalrepresentation simplybecausenomanwouldmarryher.Laughterfollowed.Somedelegatesconsideredlimitedsuffrage—permittingproperty-holdingwomentovote.Onesupporter reasonedthatfewcouldarguewiththisprinciple. Furthermore,ratherthanemboldeningsuffragists,as

some feared, such a measure would disarm them, taking away “a great deal of the thunder of the women who are traveling about the country and crying out for woman suffrage.” Opponents of women’s suffrage claimed to have women’s best interests in mind. One such delegate voicedthewidelyexpressedviewthattheballotwould “degrade” women and drag them “down to the lower level of the politician.” The delegates decided to put the question of women’s suffrage to a popular vote, a move that would have let Illinois’s male voters decide. Then, after hearing from a woman who lobbied against suffrage, they reversed themselves, closing the door to this possibility for women’s enfranchisement.7

Althoughitsparticipantswereunabletoachievethe immediategoalofastateconstitutionalguaranteeof equalsuffrage,the1869LibertyHallconventionspurred furtherorganizingandactivism.Womencontinuedto lobbylawmakers,gotocourt,organizetoaidtheircommunities,andraisetheirvoicestodemandjustice.A lookatseveralwomeninvolvedinChicago’spost-Civil Warsuffrageactivitiesrevealshowtheirsupportfor women’svotingrightswaspartofalifelongtrajectoryof agitationandactivism.

Talbert continued to write, speak, and advocate for equal rights and racial justice. Later that year, she lectured throughout Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio, eventually moving to Dayton, where in April 1870, she addressed another mass meeting of suffragists. During the 1870s, theTalbertfamilylivedinseveralOhiocities,Talbert working as a hairdresser and public schoolteacher to support her children and ailing spouse, who died in 1877. In 1881, she married Lewis Anderson. They moved to Wichita, Kansas, in 1884, where the now-Mrs. Naomi Anderson organized an orphanage for Black children excluded from the city’s whites-only children’s home. She continued to advocate for temperance as a member of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) as well as women’s rights, which she deemed essential for protecting Black women experiencing racial prejudice and violence not only in the South but throughout the United States. In the 1890s, she moved to Sacramento, where she again joined the suffrage fight. In California, she lectured widely in support of a state constitutional amendment to enfranchise women, linking Black women’s possession of the ballot to the prospect of eliminating discriminatory state laws and uplifting Black women. Anderson drew “immense crowds” in churches and meeting halls as she toured the state. Throughout her campaigns as a paid lecturer, she called for “justice and . . . a voice in making the law.”8

LikeNaomiTalbertAnderson,MaryLivermore,who organizedandpresidedovertheLibraryHallconvention, remainedinChicagoonlyashortwhilelonger,butcontinuedtoadvocateforwomen’srights.Withwomen excludedfromthepoliticalworld,shebelieved,“alarge portionofthenation’sworkwasbadlydone,ornotdone atall.” 9 Livermorehadcometothisrealizationwhile workingfortheUSSanitaryCommission,whichhandled reliefeffortsduringtheCivilWar.LivermoretouredhospitalsandencampmentstoassessandpublicizeconditionsandorganizedthesuccessfulGreatNorthwestern SanitaryFair,whichraisedmoneyfortheUnioncause. Herwartimeworkmadecleartohertheextenttowhich women’stalentsandenergywerewastedduetowomen’s exclusionfromfullparticipationinpubliclife.Afterthe war,shebecameastaunchadvocateforwomen’srights, includingsuffrage.

LivermorehadmovedtoChicagoin1857withher husband,UniversalistministerDanielLivermore,with whomsheeditedthe NewCovenant,anewspaperthrough whichtheypromotedreligious,antislavery,andtemperanceviews.Electedpresidentofthenew,predominantly whiteIllinoisWoman'sSuffrageAssociation,Livermore alsostartedanothernewspaper, TheAgitator.Itsmotto: “HealthyAgitationprecedesalltruereform....”Male friendssuggestedcallingthisnewspaper“TheLily”or someother“mild”namefitforawoman’spublication.

Livermore insisted on the “The Agitator,” which conveyed fierce determination to stir people up and create change. In 1870, Livermore moved to Boston and merged her paper with The Woman’s Journal , published by the American Woman Suffrage Association. She maintained tiestoareformnetworkforgedduringherwartimework and years in Chicago, supporting movements for women’s rights and temperance. Livermore believed education should prepare girls for independence. That way, a woman would not have to marry out of financial need. She shared these views on the lecture circuit in a talk titled “What Shall We Do With Our Daughters?” Although reportedly informing those gathered at Library Hall that she was “not very good at talking,” Livermore became an admired and frequent public speaker, an agitator who kept issues of women’s rights and other reforms before public audiences for the rest of her life.10

MaryJaneRichardsonJones’spost-CivilWarsuffrage activitywasprecededbytwodecadesofinvolvementin antislaveryandcivilrightsorganizingandactivismin Chicago.WhensheandherhusbandJohnJonesmoved toChicagowiththeirdaughterin1845,theycarriedwith themcertificatesoffreedomissuedmonthsearlierbythe MadisonCountycircuitcourt.AllfreeAfricanAmericans residinginIllinoiswererequiredtopostbondandcarry thesedocumentsunderthestate’sracistBlackLaws, whichalsoprohibitedAfricanAmericansfromvoting,testifyingincourt,orservinginthemilitia.InChicago,the Jonesesprosperedandbecameprominentmembersof thecity’sBlackcommunity.

TheJoneshomeservedasanabolitionistmeeting placeaswellasanUndergroundRailroadsafehouse. There,MaryJonestookgreatrisksbyhousingand feedingthoseseekingfreedomfromenslavement. PassageoftheFugitiveSlaveActin1850,whichrequired aclaimantonlytoassertinanaffidavitthatsomeonewas a“fugitive,”posedathreattofreedomseekersandfree Blackpeoplealike.WithaboutthreehundredBlack Chicagoans,MaryJonesandherhusbandtookpartina massmeetingatQuinnChapelAMEChurchtocoordinatearesponse.Formallydenouncingthelaw,they pledgedtoresist,organizingpatrolstokeepwatchfor bountyhunterslookingtoenslaveAfricanAmericans. Jonesalsoassistedherhusband’sdecades-longcampaign toendIllinois’sraciallyrestrictiveBlackCodes,finally repealedin1865.DuringtheCivilWar,Jonesandother womeninChicago’stightlyknitBlackcommunityorganizedreliefeffortsonbehalfofBlacksoldiers’familiesas wellasformerlyenslavedpeopleintheSouth.11 Afterthe war,shejoinedChicagowomeninorganizingforsuffrage andlaterparticipatedinthecity’sBlackwomen’sclub movement.Jones’ssupportforwomen’ssuffragewas onlyonefacetofalifelongcommitmenttoBlack freedomandequalrights.

Myra Bradwell announced the women’s rights convention in her weekly newspaper, Chicago Legal News , and later reported on its proceedings. As a married woman, Bradwell needed special permission from Illinois lawmakers in 1868 to publish the successful journal,whichkeptreadersinformedonlegalandbusiness matters. As corresponding secretary of the newly formed IWSA, Bradwell’s agitation for suffrage was entwined with her efforts to change laws under which a woman’s legal identity was absorbed into her husband’s upon marriage. She challenged gender stereotypes as well as legal barriers to women’s economic opportunity and independence.

Within weeks of the convention, Bradwell traveled to Springfield as part of a group appointed to lobby for laws granting married women rights to their earnings, property, and equal custody of their children. Bradwell drafted a bill granting married women control of their earnings, which became law in April 1869. Laws establishing further property and custody rights followed within a few years. 12 Insummer1869,havingstudied lawunderherhusband’smentorshiptoassistwithhis legalpractice,sheappliedtotheIllinoisSupremeCourt foradmissiontothebar.Afewmonthslater,she receivedanoticeofdenial.Thereason:asamarried woman,shewasnotpermittedtoenterintocontracts withorforherclients,aconditionthatleftherunableto practicelaw.Bradwellcraftedawell-reasonedchallenge tothisdecision,notingthatstatestatutesdidnotexplicitlyprohibitwomenfromthelegalprofession.In response,thecourtinformedherthatthemanyhistoricalrestrictionsonwomen’srightsmadeclearthat Illinoislawmakersneverintendedforanywoman,marriedornot,topracticelaw.

Dismayedbutdetermined,Bradwelllaunchedthefirst sexdiscriminationcaseheardbytheUSSupremeCourt. Forthenextthreeyears,sheupdatedreadersonhercase, Bradwellv.Illinois,whichessentiallyposedthisquestion: Didawomanhavearighttopursueherchosenoccupation?ThecourtgaveitsunfavorablerulinginApril1873. Onejustice,JosephP.Bradley,drewonidealizedviewsof whitewomanhoodtoclaim,“Thenaturalandproper timidityanddelicacywhichbelongstothefemalesexevidentlyunfitsitformanyoftheoccupationsofcivillife.” Inthemeantime,womenhadgainedtherighttopractice lawinIllinois,throughan1872statelawBradwellhelped draftgrantingequalrightstoemploymentinmanyoccupations.HavinglostherSupremeCourtcase,however, Bradwellfocusedherenergiesonpublishingher acclaimednewspaperuntilherdeathin1894.When,in March1890,theIllinoisSupremeCourtdecidedtogrant heralicensetopracticelawbasedonherinitialapplication,Bradwellnotedtheoccasioninhernewspaperbut declinedtoaccepttheoffer.13

CatharineVanValkenburgWaiteservedassecond presidentofIWSAafterMaryLivermore’sdepartureand oversawthegroup’slegislativeworkuntil1890.On October3,1871,Waiteandexecutivecommitteemembersmetatthegroup’sheadquartersat145Madison StreettodiscusstheupcomingNovemberelection.With women’svotingrightsleftoutofthestate’snewconstitution,theypreparedtoembarkonanewpathtosuffrage.Fivedayslater,theChicagofiredestroyedthe officesoftheassociation,whichwouldnotmeetagain formonths.Undeterred,Waite,alongwithoneofher daughters,appearedbeforetheBoardofRegistryinHyde ParkonOctober31andaskedtobeaddedtothelistof registeredvoters.Whentheywererefused,Waitetook themattertocourt—asplanned.14

LikeBradwellandotherwhitesuffragists,Catharine Waite’ssuffrageactivismwasoneaspectofherbroader engagementwithpubliclifeandcommitmenttowomen’s rights.Inthe1850s,shewroteandlecturedonequal rightsthroughoutIllinoiswithhusbandCharles BurlingameWaite.RefusedadmissiontoRushMedical Collegein1866,sheranagirl’sschoolinHydeParkand laterworkedasaneditorandpublisher.In1886,Waite graduatedfromUnionCollegeofLawandafterwardprovidedprobonolegalservicesforwomenunabletopay

MarcaBristo,aninternationallyrecognizedforceinthedisabilitycommunity,workedtirelesslytopromotedisabilityrightsandtodrive sweeping social reforms that changed Chicago and the nation. As the founding CEO of Chicago-based Access Living, a disability service and advocacy center for people with disabilities, run and led by people with disabilities, Bristo was committed to building a more inclusive society for disabled people to live fully-engaged, self-directed lives. Access Living continues this work today. In the 1980s, Access Living, Chicago ADAPT, and other demonstrators launched a campaign for accessible transportation, petitioning the Chicago Transit Authority (CTA) for lifts on public buses. Their activism and resulting lawsuit led to the improved accessibility of Chicago’s public transit, and created a blueprint for accessible transit systems across the country. Bristo also helped author the landmark 1990 Americans with Disabilities Act, and fought for its passage.

foralawyer.Shealsoeditedandpublished ChicagoLaw Times ,aquarterlyjournalthatincludedmanyarticles advocatinglegalreformstosecurewomen’srights.15

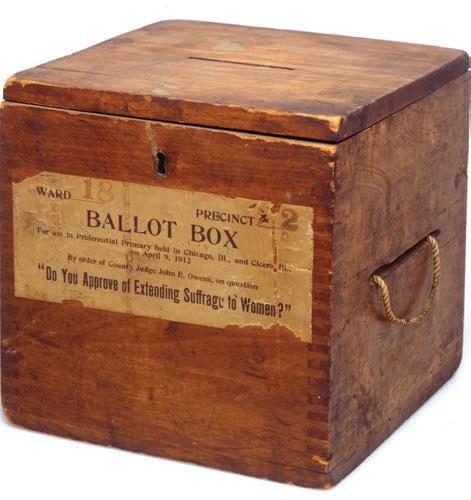

Between1868and1872,hundredsofwomen, includingWaiteandherdaughter,triedtoregisterand vote.AlthoughtheFourteenthAmendmentdefined votersas“male,”italsopromisedprotectionfromlaws thattookawaythe“privilegesandimmunities”ofcitizenship.Unsurewhetherthisnewamendmentmade womenvoters,somelocalpollingofficialspermitted themtocastballots.InotherplacessuchasHydePark (notyetpartofChicago),womenwerenotallowedto register.Elsewhere,registeredwomenwereturnedaway atthepolls.Would-bewomenvotersanticipatedthese outcomesaspartofthe“newdeparture”strategy.Ifpreventedfromvoting,theirnextstepwastochallengethe decisionincourt.16

InChicago,aJanuary13,1872, Tribune headline informedsuffragistsofthedisappointingoutcomeof Waite’scase:“Ladies,YouCan’tVote.”CookCounty SuperiorCourtJudgeJamesonruledthatvotingwasnot a“natural”rightprotectedbytheConstitution.TheUS SupremeCourtwouldalsoreachthisconclusion, puttinganendtothisstrategy.AfterVirginiaMinorwas barredfromvotinginMissouri,thecourtruledin Minor

vs. Happersett (1875) that voting was not a right of citizenship protected by the federal government. That decision allowed states to keep women from voting . It also set precedent for later decisions that permitted discriminatory laws that restricted voting for poor people, immigrants,andpeopleofcolor. 17

Withanotherpossibleavenuetosuffrageblocked, Chicago’sactivistwomencontinuedtoagitateandorganize.Inthedecadesthatfollowed,theypressedforlocal lawstoenfranchisewomen,maintainedtieswithsuffragistsoutsidethestate,hostedmeetingsofregionaland nationalsuffragegroups,andjoinedeffortstowinsupportforafederalamendment.Theirinvolvementinthe decadesaroundtheturnofthecenturyinarangeof organizationsaddressingamultitudeofissueswould bringthemtogethertogainsubstantialvotingrights.

AbolitionistandactivistfortherightsofBlackpeopleandwomen, Sojourner Truth was among the hundreds of women who voted between 1868 and 1872.

Duringsixdecadesoflegalpractice,PearlM.Hartcombatted injustice, defended civil liberties, and fought for the rights of marginalized people. After graduating from law school in 1914, Hart served as a public defender in the 1920s and 1930s for children and women in Cook County’s juvenile and women’s courts. During the mid-century anti-Communist Red Scare, Hart appeared on behalf of many individuals called before the House Un-American Activities Committee. Hart also defended LGBTQ people victimized by police entrapment and harassment and was a founder in 1965 of the Mattachine Society of Chicago, an early LGBTQ-rights group. Hart served as the group’s legal counsel until her death in 1975 and was remembered as the “Guardian Angel of Chicago’s gay community.”

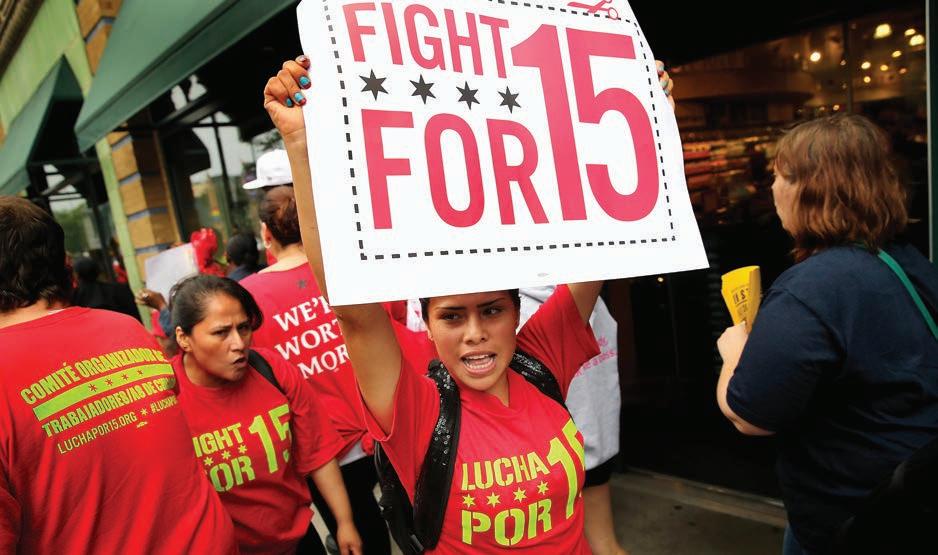

OnJuly1,1913,spectatorslinedChicago’s sidewalkstowatchmorethanahundred automobiles,yellowandwhitebannersand streamersfluttering,maketheirwayupand down Michigan Boulevard (now Avenue) in a late afternoon victory procession. The jubilant motorists were celebrating the Presidential and Municipal Voting Act, signed into law earlier that week by Governor Edward F. Dunne. The law granted nearly full suffrage, empowering Illinois women to vote for local offices and in presidential elections. Chicago area women led the way to this substantial victory. The hundreds of women riding in the auto parade represented the many organizations that campaigned for the law, including suffrage groups such as the IESA, the Chicago Political Equality League, and the Alpha Suffrage Club, the state’s first Black women’s suffrage association; working women’s organizations, including the Chicago Women’s Trade Union League (WTUL) and Chicago Teacher’s Federation; club women and reformers from the Chicago Woman’s Club and Women’s City Club; and Progressive Party and Socialist Party supporters.

During the decades before Congress passed the Nineteenth Amendment, Chicago women of different backgrounds pursued varied and sometimes overlapping goals—working for urban and social reforms, economic and political empowerment, and racial equality. Those issues and efforts also propelled many to press for suffrage, forming tenuous alliances and building momentum toward full enfranchisement. Viewing the ballot as an expression of political will and a tool to achieve larger goals, Chicago women followed many paths to suffrage, becoming voters one campaign and one law at a time.

As the experiences of Naomi Talbert Anderson and Mary Jones attest, Black women navigating a world built on both racial and gender oppression did not have the luxury of battling only for women’s rights. Their longtime activism reached new heights in the early 1890s with the creation of a network of women’s clubs devoted to social action. Many of the women involved in these clubs also fought for women’s right to vote. Their activism and support for suffrage was rooted in the struggle for Black freedom and connected to such issues as widespread racial discrimination, a racist criminal justice system, exclusion from white institutions, and violent attacks on Black men and women intended to maintain white supremacy. Chicago women played leadership roles in this national movement. As the city’s Black community continued to grow, spurred by migration from the South, they organized to meet its needs while addressing racial inequities both within the city and the nation.

Askilledpublicspeaker,journalist,andsuffragist, Chicago’sFannieBarrierWilliamsworkedtoassistBlack Chicagoansexcludedfromthecity’swhiteinstitutions whileconnectinglocaleffortstoanationalmovementof Blackactivistwomen.Forexample,racialdiscrimination inthecity’shospitalspreventedBlackpatientsfrom accessingadequatehealthcare.BarrierWilliamsstrongly advocatedforandraisedfundstocreateProvident Hospital,aninterracialfacilitycontrolledbyAfrican Americans,whichalsoprovidedtrainingandemploymentforBlacknursesexcludedfromwhitenursing schools.BarrierWilliamsalsoservedasvicepresidentof theIllinoisWomen’sAlliance,aninterracialcoalitionof women’sgroupsformedin1888thatfocusedonthe wellbeingoftheindustrializingcity’sworkingwomen andchildren.

Throughherworkwiththealliance,BarrierWilliams forgedcooperativebondswitheliteBlackandwhite reformerstowardsharedgoals.ButBarrierWilliamsalso experiencedracialexclusion.Whenwhitesupporters nominatedherformembershipintheChicagoWoman’s Club(CWC)inNovember1894,themovestirredcontroversyamongtheall-whitegroup,whichinitially rejectedBarrierWilliams’sbidformembership.The matterembroiledtheclubformorethanayearuntilit passedaresolutionaffirmingthatnoracialqualifications formembershipexisted.BarrierWilliamswasadmitted.

The scenario played out again in 1912 when, amid fervent organizing for citywide suffrage measures, Barrier Williams, together with Black clubwomen Elizabeth Lindsay Davis and Mrs. George C. Hall, applied for membership in the Chicago Political Equality League (CPEL),anoutgrowthoftheCWCorganizedin1894to educate women on politics and advance women’s rights. By the 1910s, the CPEL stood at the forefront of local suffrage activism. Only after a public campaign waged by

many people in the Pilsen, Little Village, and Back of the Yards communities from accessing healthcare. In the 1980s, she became the driving force behind Project Alivio. The community campaign raised funds and support to create a medical center at 2355 S. Western Ave, which opened in 1989. The bilingual/bicultural Alivio Medical Center opened in 1989 with Velásquez as the first executive director. It continues to operate an urgent care center and six community health centers, providing care for the un- and underinsured.

To Fannie Barrier Williams, the club movement was a “national uprising” of Black women “pledged to the serious work” of racial advancement.She and Davis led Chicago clubwomen in hosting the 1899 meeting of the National Association of Colored Women, the umbrella organizationofBlackwomen’sclubsfoundedthreeyears earlier. Organizing this convention strengthened ties among Chicago’s clubwomen and connected them to women’s efforts in other regions. During the three-day gathering, participants addressed topics traditionally linked to women’s roles as caretakers or moral guardians of the home. They also focused on urgent, life-and-death matters: lynching, segregation, and the convict-lease system—forced prison labor that targeted African American men. During this meeting, members also elected the group’s next slate of officers.19 Althoughnot yetabletoparticipatefullyininthewiderworldofelectoralpolitics,NACWmembers,likemembersofcountlesswomen'sgroupsinthisera,enacteddemocracyas votersandofficeholderswithintheirclubwork.

ElizabethLindsayDaviswasanearlyadvocateforcreationoftheNACW;throughhersubsequentworkasthe group’snationalorganizerandhistorian,shegreatly expandedmembershipanddocumenteddecadesof Blackactivistwomen’svitalwork.InChicago,among otheractivities,in1896sheorganizedthePhyllis WheatleyClub,namedforaneighteenthcentury enslavedAfricanAmerican.Theclubinitiallyofferededucationalprograms,undertookcharitablework,andoperatedasewingschool.Later,afterprovidingtemporary

BoardofDirectorsofthePhyllisWheatleyHomeAssociation, c. 1915. Club women tapped extensive networks and organized fundraisers to support operations and maintain the residence, which moved to 3256 Rhodes Avenue in 1915, and again in January 1926 to 5128 S. Michigan Blvd.

Emergingfromthecooperativeefforttoorganizethe1899ChicagomeetingoftheNationalAssociationofColoredWomen,theIllinois Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs was created by the joining of the “Magic Seven”—Chicago’s first Black women’s clubs. The federation’s motto: “Loyalty to Women and Justice to Children.” Elizabeth Lindsay Davis (top row center) served as president and historian of the state federation. These portraits were published in her book, The Story of the Illinois Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs, 1900–1922.

shelter for several girls in members’ homes,the club established the Phyllis Wheatley Home for Girls, which opened its doors in 1908at3530ForestAvenue. There, excluded from the white YWCA and other settlement houses, young Black women migrating to Chicago found a safe residence, help finding employment, and other services. Davis served as president of the Phyllis Wheatley Club for more than twenty years, work that informed her views on suffrage. She called women “a potent factor in the body politic,” whose influence as voters would advance the goals of their philanthropic and reform activities.20

Davis’slongtimeinvolvementinclubworkincluded servingassecretaryofChicago’sfirstBlackwomen’s club,organizedbyantilynchingactivistIdaB.Wellsin 1893.WellsreachedouttoMaryRichardsonJonesto serveashonorarychairofthenewclub,amovethat bridgeditsworkandtheactivismofanearliergeneration ofBlackChicagoans.WhenWellstraveledtoEnglandto

Members of Mujeres Latinas en Accion (MLEA) Young Professionals Advisory Committee (YPAC) attend the January 21, 2017, women’s march in Chicago. Started in Pilsen in 1973, MLEA centered issues affecting girls and women, encouraging Latinas to become active agents of their lives and communities. Founders battled hostility and suspicion—from men critical of their focus on women to religious leaders conce rned the group’s work would weaken families. Today the longest-standing Latina organization in the US, MLEA fights for immigrant justice, women’s health and reproductive rights, economic justice, and an end to gender-based violence.

Publicizedinthis1892pamphletandelsewhere,IdaB.Wells’s investigations revealed how lynching was used as an instrument of terror to uphold white supremacy. She later cofounded the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, which pressed for federal antilynching legislation.

rallysupportforanantilynchingmovement,members honoredherbynamingthenewclubforher.21

WellsrelocatedtoChicagoafterreceivingdeath threatsforspeakingoutagainstlynchingafterthreeof herfriendsweremurderedbyawhitemobinMemphis in1892.ThehorrificeventpromptedWells,ajournalist, toinvestigatesystematicviolenceagainstBlackmenand women.Defendersoflynchingjustifiedthesemurdersby claimingthatBlackmenthreatenedandrapedwhite women.Wells’sinvestigationsrevealedthatviolentmobs targetedBlackpeoplewhocompetedeconomicallywith whites. 22 Aswhitesouthernersregainedpowerafter Reconstruction,theycreatedasystemoflegalsegregationandinequalityand,despitetheFifteenth Amendment,deniedBlackmen’svotingrightsthrough threats,violence,andlawssuchaspolltaxesandliteracy tests.Supportiveofthissystemofracialoppression, lynchingwasusedtoterrorizethewiderBlackcommunityandkeepitsmembers“intheirplace.”

FromChicago,Wellscontinuedherantilynching activismandbecameaninternationalfigureduringher

lifelong campaign for racial justice. In 1895, she married Ferdinand Barnett, a Chicago attorney. Locally, WellsBarnett’s efforts on behalf of Chicago’s growing Black community took many forms, from helping to establish the city’s first Black kindergarten, to challenging Chicago Tribune editorialsfavoringsegregatedpublicschools,to her work with the Negro Fellowship League. WellsBarnett formed this group to foster dialogue and action after widespread racial violence against Black residents of Springfield in 1908. By 1910, the League also provided a rooming house and recreation space in the Douglas area on the South Side, as well as employment services to Black men excluded from the white YMCA. Through Wells-Barnett, the group extended its work to “all matters affecting the interest of our race,” including its efforts on behalf of Joseph Campbell. Upon learning of his plight, Wells-Barnett took action to help Campbell, accused of murdering a white woman, defend himself

against the questionable charges. Concerned he would not get a fair trial in a racist criminal justice system, Wells-Barnett raised awareness and money to pay for Campbell’s legal defense. Despite these efforts, Campbell was found guilty and received a death sentence. The publicattentionandlegalsupportbroughtbyWellsBarnett and her husband helped in getting his sentence changed to life imprisonment.23

Althoughwomencouldnotyetvoteincityelections, sheformedtheWomen’sSecondWardRepublicanClub in1910to“assistmen”indeployingtheirvotesforthe bettermentofthecity’sBlackcommunity.Amemberof IESAandCPEL,WellsalsoorganizedtheAlphaSuffrage ClubinJanuary1913. 24 ForWells-Barnett,asforother Blacksuffragists,thevotewasnotamatterofgaining individualrightsforwomen.Rather,itwastiedtoa largerstruggleforpoliticalempowermentandracial equitythroughouttheUS.

Wells-BarnettfoundedtheNegroFellowship League in 1908 and raised awareness and funds to assist with Joseph Campbell’s legal defense in 1915.

AttheMarch3,1913,Woman’sSuffrageProcessioninWashington, DC,IdaB.Wells-Barnettprotestedorganizers’insistencethatshe marchseparatelywithBlacksuffragistsinsteadofwithwhitemembersoftheIllinoisdelegation.AlicePaul,processionorganizerand headofNAWSA’sCongressionalCommittee,believedastunning spectacle would attract media attention and widen support for women’s voting rights. Knowing national support was required for a constitutional amendment and concerned that allowing Black and white women to march together would anger and alienate white southerners, she and other planners tried to limit Black women’s participation. That morning, IESA president Grace Wilbur Trout had advised the Illinois women to go along with efforts to exclude Wells-Barnett. But Wells-Barnett refused to give in. Instead, as white suffragists from Illinois passed by, she marched alongside Belle Squire and Virginia Brooks, who had opposed the plan to segregate Illinois suffragists.

Duringthelatenineteenthcentury,Chicago andnearbyEvanston servedasheadquartersfora growingtemperancemovement,whichalsoled manywomentosupport suffrage.Nineteenth-centurywomenweredrawn totemperanceasamoral reformandapractical necessity.Withoutcustodyrightstotheirchildrenandunableto divorceorownpropertyformuchofthecentury,marriedwomenhadnomeanstoescapeabusive,alcoholdependenthusbands.Moreover,suchmencould scarcelybesaidtorepresentthebestinterestsoftheir wivesandchildrenattheballotbox.DuringtheLibrary Hallconvention,prominentwomen’srightsoratorAnna Dickinsoncounteredanantisuffragist’sremarksby describingmenwhomthelawmade“absolutemasters ofwivesandchildren;menwhoreeltotheirhomes nightafternighttobeatsomehelplesschild,tobeat

some helpless woman.” 25 Armed with the ballot, she argued, women could protect themselves and their families by voting for prohibition and other needed reforms. Such a view gathered widespread support in the last decades of the nineteenth century through the work of FrancesWillardandtheWCTU.