C H I C AG O H I S T O RY Editor-in-Chief Rosemary K. Adams Associate Editors Gwen Ihnat Emily H. Nordstrom Designer Bill Van Nimwegen Photography John Alderson Jay Crawford

Copyright 2006 by the Chicago Historical Society Clark Street at North Avenue Chicago IL 60614-6038 312-642-4600 www.chicagohistory.org ISSN 0272-8540 Articles appearing in this journal are abstracted and indexed in Historical Abstracts and America: History and Life.

Publications Intern Jacqueline Bransky

Footnoted manuscripts of the articles appearing in this issue are available from the Chicago History Museum’s Publications Office.

Jesse H. Ruiz April T. Schink Gordon I. Segal Larry Selander Paul L. Snyder Robert Swegle Jr. Samuel Tinaglia

Mrs. John J. Lewis Jr. R. Eden Martin Mrs. Frank D. Mayer John T. McCutcheon Mrs. Newton N. Minow Potter Palmer Bryan S. Reid Jr. Dempsey J. Travis

On the cover: The Woodlawn neighborhood became the site of legal battles over racially restrictive covenants. ICHi-23193

C H I C AG O H I S T O R I C A L S O C I E T Y OFFICERS

TRUSTEES

John W. Rowe Chair

Philip D. Block III Stanley J. Calderon Walter C. Carlson Warren K. Chapman Patrick F. Daly Jonathan F. Fanton T. Bondurant French Sallie L. Gaines Timothy J. Gilfoyle David A. Gupta Jean Haider Barbara A. Hamel Mrs. Harlow N. Higinbotham David D. Hiller Henry W. Howell Jr. Randye A. Kogan Fred Krehbiel Robert Meers Timothy P. Moen James Reynolds Jr.

Barbara Levy Kipper Vice Chair Sharon Gist Gilliam Vice Chair David P. Bolger Treasurer Paul H. Dykstra Secretary M. Hill Hammock Immediate Past Chair Gary T. Johnson President Russell L. Lewis Executive Vice President and Chief Historian

LIFE TRUSTEES

Lerone Bennett Jr. Bowen Blair Laurence O. Booth John W. Croghan Stewart S. Dixon Michael H. Ebner Philip W. Hummer Richard M. Jaffee Edgar D. Jannotta W. Paul Krauss Joseph H. Levy Jr.

HONORARY TRUSTEE

Richard M. Daley Mayor, City of Chicago

The Chicago History Museum is easily accessible via public transportation. CTA buses nos. 11, 22, 36, 72, 73, 151, and 156 stop nearby. For travel information, visit www.transitchicago.com. The Chicago History Museum gratefully acknowledges the Chicago Park District’s generous support of all of the Museum’s activities.

THE MAGAZINE OF THE CHICAGO HISTORY MUSEUM

Fall 2006 VOLUME XXXIV, NUMBER 3

Contents

4 26 44 64

The Klan Moves North David Craine

“We Belong in Washington Park” Truman K. Gibson Jr.

Yesterday’s City Henry Field’s Legendary Expeditions S. J. Redman

Index to Volume 34

The Klan Moves North In the 1920s, the Ku Klux Klan emerged in Chicago to fight the perceived dangers of urban life. DAV I D C R A I N E

F

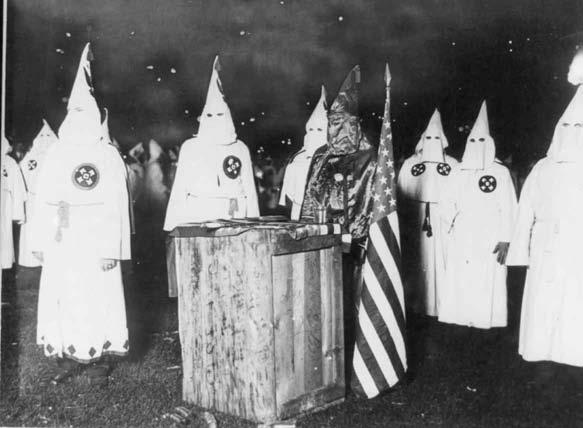

Leaders preside over a meeting of thousands of Klansmen from Chicago and northern Illinois, c. 1920.

4 | Chicago History | Fall 2006

rom 1921 to 1925, Chicago became embroiled in a controversy that many associated with the South. As part of a nationwide movement, the Invisible Empire of the Ku Klux Klan established itself in the city and within a year attracted thousands of adherents. Preaching “100 percent Americanism” and white Protestant supremacy, the Chicago Klan found fertile ground for its ideals of bigotry. Unlike its Reconstruction-era predecessor, the Klan of the 1920s tailored its message of hate to each territory it invaded. In Chicago, the message preyed predominantly on the insecurities and fears of Protestants against Catholics. For four years, the Klan flourished, publishing a weekly newspaper and holding meetings, social events, and recruitment drives. In response, a small group founded the American Unity League (AUL), devoted to the eradication of the Klan in the city and across the country. Publishing its own newspaper, the AUL made significant inroads in their mission against the Klan. But, after an intense four-year battle, the Chicago Klan and its detractors disappeared, all but forgotten to memory and history. Led by Colonel William Joseph Simmons, the revival of the Ku Klux Klan occurred atop Stone Mountain in Georgia in November 1915, two weeks before the Atlanta opening of D. W. Griffith’s cinematic homage to the Klan of the Reconstruction era, Birth of a Nation. The original Klan was founded as a Southern, rural, antiblack movement after the Civil War. The group’s reemergence in the early twentieth century was a reaction to societal changes of a different nature.

Dawn, the Klan-endorsed newspaper, published this depiction of “100 percent Americans� in February 1923. The sketch groups Klansmen among pilgrims, pioneers, and soldiers. Klan Moves North | 5

The census of 1920 showed that for the first time more Americans lived in cities than in rural areas, bringing significant changes to the country’s cultural landscape. Urban popular culture—with its jazz rhythms, mass media, bright lights and literary experimentation—lured millions of young, rural Americans. For many with traditional conservative values, however, urban culture remained bewildering and frightening. The forces of modernity and diversity inherent in twentiethcentury urban culture triggered in many a desire to return to times of so-called normalcy. The flappers and rogues of the Jazz Age, whose lifestyles touted fast cars, suggestive music, and loose sexuality, epitomized the dangers of urban life.

To advance their cause and solicit memberships, the Chicago Klan placed advertisements in local newspapers. Such ads ran among promotions for women’s clothing, furniture, and Florida vacations.

In the early twentieth century, the ideals of the new Klan appealed to many Americans, as evidenced by the popularity of Birth of a Nation, D. W. Griffith’s cinematic portrayal of the Reconstructionera Klan, which opened in 1915. 6 | Chicago History | Fall 2006

In response, the Ku Klux Klan offered an illusory hope of imposing rural values on this environment by returning to an idealized version of the status quo of the 1890s: fundamental Protestantism, white supremacy, marital fidelity, and respect for paternal authority. All laws were to be obeyed—particularly Prohibition. The Klan also targeted criminals, dishonest politicians, prostitutes, bootleggers, gamblers, and grafters. In their struggle to resist the modern world, the Klan believed that “liberals were a worse menace than foreigners.” The growth of American cities, particularly in the industrial North, was due in large measure to the huge

The Chicago Klan portrayed itself as a national force against undesirable urban influences such as booze, anarchists, dope fiends, and disreputable women. Klan Moves North | 7

influx of eastern and southern European immigrants, whose languages, customs, appearance, and, perhaps most significantly, religions were distinctly different from those of earlier immigrants from northern and western Europe. These new immigrants—Poles, Italians, and Russians, in particular—were largely Catholics and Jews. While the new Klan did not discard the old Klan’s attitudes toward African Americans, it focused primarily on Catholics. Ridiculed as “popery” and “Romanism,” antiCatholicism proved to be an effective recruiting tool. The Klan portrayed Catholics as being disloyal to the United States, their true allegiance reserved exclusively to the Pope, whose alleged secret mission was world domination. Fantastic stories circulated about Catholic plans for revolution. One rumor claimed Catholic families celebrated the births of their babies by burying a gun and fifty rounds of ammunition for each child beneath the local

church. When the children reached shooting age, the guns would supposedly be excavated and used to seize power and give the United States to the Pope. In Kokomo, Indiana, when a rumor spread that the Pope was “pulling into town on a southbound train from Chicago to take over,” a mob formed and stoned the train. Other events help explain the climate that made the revival of large-scale Klan support possible. Widespread disillusionment over World War I left many desiring a return to isolationist policies. Government-sanctioned discrimination against Germans and the Espionage and Sedition Acts conditioned many Americans to accept intolerance of differences. The anticommunist crusade of Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer and the trial of anarchists Sacco and Vanzetti illustrated an America where dissent, especially when brandished by immigrants, was not to be tolerated.

Klan leader William Joseph Simmons, known among members as the Imperial Wizard, sits at a table during the U.S. Congress’s investigation of his organization. 8 | Chicago History | Fall 2006

While the Ku Klux Klan had roots in the rural South, the new Klan spread rapidly through the urban North, and by 1922, Chicago had the largest membership of any metropolitan region in the United States. This exponential growth was unforeseen by Simmons in 1915; in the first five years of its existence, Simmons’s Klan had procured a meager membership of less than three thousand Southern men. National expansion and the Klan’s growth in the urban North was the result of two events: Simmons’s agreement to turn over recruitment to two enterprising promoters in 1920 and an exposé of the renewed Klan in the New York World in 1921. Edward Clarke and Elizabeth Tyler formed the Southern Publicity Association in 1917 and used their talents to market organizations, including the AntiSaloon League, the Salvation Army, and the Red Cross. After Tyler’s son-in-law joined the Klan, Clarke and Tyler contracted with Simmons to create a propagation department in exchange for 25 percent of each new recruit’s ten-dollar initiation fee. To expand recruitment nationwide, Clarke and Tyler devised a strategy where paid organizers studied their local territories to identify groups that might be considered “enemies” to nativeborn Protestant whites: Mormons in Utah, union radicals in the Northwest, and Asian Americans on the Pacific Coast. Using contemporary marketing and advertising techniques, the organizers began by soliciting their friends and acquaintances and followed all contacts with Klan membership applications, propaganda, and requests for dues. The national office sent lecturers—often ministers—to speak about the need for the Klan’s crusade of militant Protestantism. Their strategy worked. During the first six months of their efforts, Clarke and Tyler claimed the recruitment of

Above: Klan certificate of membership issued to William W. Newman of Chicago. Below: Dawn printed this “test” for potential Klansmen above a tear-off, mail-in membership coupon.

Klan Moves North | 9

After founder Grady Rutledge left the American Unity League, he joined the Klan and became a regular contributor to Dawn. Many of his articles exposed the inner workings of the AUL’s newspaper, Tolerance. 10 | Chicago History | Fall 2006

eighty-five thousand new members. Ironically, the marketing strategies they employed to sell the Klan mirrored many of the same techniques being used by the advertising industry to market the urban culture of the Jazz Age—movies, radio, magazines, automobiles, and clothing— that the Klan was challenging. Alarmed by the Klan’s growth nationwide, the New York World began a threeweek exposé of the group on September 6, 1921. Based on months of research by reporter Rowland Thomas, the articles placed particular emphasis on the more violent aspects of the Klan and were carried by eighteen newspapers across the country. Partly as a result of the World’s coverage, the U.S. Congress began an investigation of the Klan. Simmons was called to testify and used the occasion to promote the Klan’s virtues. He stated that the organization neither promoted nor tolerated violence of any kind and that the Klan’s oath and ritual were a matter of public record rather than cloaked in secrecy. He further testified that the violent actions attributed to the Klan were perpetrated by troublemakers hiding behind the robes of a Klansman. According to historian Kenneth T. Jackson, Simmons dramatically swore: “If the Ku Klux Klan were guilty of a hundredth part of the charges made against it, ‘I would from this room send a telegram calling together the grand kloncilium [executive council] for the purpose of forever disbanding the Klan in every section of the United States.’” In the end Congress did nothing, partly because Representative W. D. Upshaw of Atlanta introduced a bill calling for similar investigations of other “secret” societies, including the Catholic-based Knights of Columbus. Through the newspaper reports and investigations, the Klan received free, nationwide publicity. Newspapers across the country carried the New York World’s exposé, and the Klan became a popular topic of conversation. Within a year, membership applications—many of them facsimile blanks printed in the newspapers—poured into Klan headquarters, increasing the rolls from one hundred thousand to almost one million nationally. At first glance, Chicago seemed to be an unlikely place for Klan recruitment. The city’s staggering growth—from just five hundred thousand in 1880 to almost three million in 1920—was largely a result of immigrants from southern and eastern Europe and growing migration from the South. The census of 1920 showed that Chicago was home to more than one million Catholics; 800,000 foreign-born immigrants; 125,000 Jews; and 110,000 African Americans. The city also seemed to

This map illustrates the distribution of the Chicago Klan in 1923. Each asterisk represents two hundred Klansmen. Although the organization charted chapters throughout the city, many were based in neighborhoods on the North and South Sides.

Klan Moves North | 11

The Chicago Tribune covered the Klan’s event.

embrace and embody all that was modern and exciting in the Roaring Twenties. Breweries, speakeasies, and underworld crime gave the city a national reputation for vice, corruption, and lawlessness. Yet by 1922, Chicago had the largest Klan membership of any city in the nation. Fully 13 percent of those eligible—adult, white, Protestant men—in Chicago had joined the Klan. What accounted for the unprecedented popularity of such a rural-based movement in a giant, cosmopolitan metropolis like Chicago? The answer almost certainly lies in the origins of the Protestant population of Chicago. The Klan was small-town in spirit, and in some ways, so was Chicago. The Klan of the 1920s flourished in newer cities and those that had grown dramatically within a generation or two: Detroit, Milwaukee, Pittsburgh, Dayton, Indianapolis, Denver, and Chicago. While immigrants made up a significant portion of Chicago’s population growth, hundreds of thousands of newcomers had arrived from the farms and small towns of the Midwest. In addition to those lured by the excitement of the big city, many rural white Protestants were driven off their land by low crop prices, new machinery, and competition from corporate farms They came to Chicago to work in the city’s growing industries and 12 | Chicago History | Fall 2006

brought with them the educational limits and social insecurities of the decline of rural America. According to historian Geoffrey Perrett, the Klan offered comfort to people who lamented the loss of a way of life that they felt defined America: And what a sensation they caused on a Friday night in some drab little town when they paraded holding blazing torches. A Klan parade passed by in utter silence, a silence so complete, some claimed, that you could almost hear the breathing of the crowd. What a release this was from the inferiority complex of these grade-school graduates, struggling for a crust in a severe economic recession, forced by an industrialized, urbanized world into daily awareness of their position at the bottom of society. They fastened like the shipwrecked to the one positive attribute they possessed— their old-stock Americanism. In their daft way, they believed that this single virtue qualified them to be guardians of society. Don the flowing robes, converse in the cryptic speech of the Klansman, parade past a crowd awed into silence, and for a while the burning sense of inferiority was gone. A nobody in the world became a somebody in the Klan.

True to the marketing techniques of Clarke and Tyler, the Chicago Klan adapted its message to its constituency. With African Americans comprising only four percent of the city’s population in 1920, the Chicago Klan focused its efforts on capitalizing on Protestants’ fears about the one-million-plus Catholics scattered across the city. The Chicago Ku Klux Klan began its recruitment drive in earnest in June 1921 with the arrival of Regional Commander C. W. Love from Indianapolis. Setting up shop on Clark Street, Love and his staff of forty-one recruiters worked through the summer to line up prospective Klansmen. Their initial efforts culminated on the evening of August 16, when 2,376 candidates were initiated in a meadow six miles south of suburban Lake Zurich. Headlines in the Chicago Tribune the next day proclaimed, “Ku Klux Rites Draw 12,000.” As a result, Colonel John V. Clinnin of the United States district attorney’s office in Chicago initiated an investigation into the Klan. The Chicago Tribune reported that after months of research, “Clinnin declared that although the organization would foster disorder and anarchy, he could find nothing on which to base legal action.” The Chicago City Council moved as well, unanimously passing the following resolution on September 19:

In an attempt to improve its image, the Chicago Klan began ostentatiously interrupting Sunday morning services to give donations to select Protestant churches. Above and below: Newspaper coverage of one such event promoted speculation about the church’s complicity.

Whereas the traditions and odium attached to the Ku Klux Klan and the acts which have been attributable to it make it a menace to a city like Chicago, having a heterogeneous population and different religious creeds; now therefore be it: Resolved, that the city council of Chicago officially condemns the presence of the Ku Klux Klan in Chicago and pledges its services to the proper authorities to rid the community of this organization. But investigations and resolutions did not have the desired effect, and membership rolls increased dramatically in the following months. Typically, the Klan would only charter one chapter per city or town, but Chicago was eventually able to support more than twenty neighborhood Klan units. Groups were chartered in South Side neighborhoods with rapidly increasing numbers of African American residents, including Englewood, Woodlawn, and Kenwood. Charters were also granted in ethnically diverse areas on the North and West Sides: Irving Park, Logan Square, and Austin. By the summer of 1922, large-scale Klan demonstrations were held both near Joliet and at Ninety-first Street and Harlem Avenue in Chicago. Image enhancement became a priority for the Chicago Klan and church visits a regular activity. Groups of robed Klansman interrupted Protestant church services by walking up the aisle to leave a monetary donation, then departing as quickly as they had arrived. Such visits took place at Douglas Park Christian Church, Pacific Klan Moves North | 13

Dawn’s common topics included attacks on the rival publication Tolerance and the AUL and promoting the Klan’s anti-Catholic agenda by rallying against the Pope and “his spies.” 14 | Chicago History | Fall 2006

Although the editors of Tolerance criticized Dawn, their main agenda was to discredit and break apart the Chicago Klan. Their most effective, if imperfect, tactic was to publish lists of names reportedly from Klan membership rolls. Klan Moves North | 15

Congregational Church, Third Congregational Church, the Southfield Community Church, and the Nazareth Evangelical Church. At Immanuel Baptist Church at Twenty-third Street and Michigan Avenue, about five hundred Klansmen filed past the minister, dropping contributions in a large basket. The presence of a Chicago Tribune photographer, who snapped pictures for the following day’s edition, added to the speculation about the church’s prior complicity. Klan recruitment even reached the Chicago public schools. Superintendent Peter A. Mortenson ordered an investigation into the practice of Klan members paying Chicago schoolchildren to collect the names and addresses of Protestant classmates’ families. The mothers of the families were then sent circulars, addressed “To Protestant Women of American Birth,” extolling the virtues of the Klan and asking for their help recruiting “gentlemen” members. Mortenson declared that the Klan’s activities were a clear violation of school rules and would not be tolerated. Interestingly, he only took issue with the methods the Klan employed, backing off from a denunciation of the Klan itself. The Chicago Tribune quoted him as saying, “No one is permitted to obtain names and addresses of schoolchildren, except as the roster of graduates appear in the annuals.” Mortenson continued, “I would take the same action against any society or organization. This is not a crusade on my part against the Ku Klux Klan particularly.” By October of 1922, the Chicago Klan’s imageenhancement plan included the first edition of a weekly publication. Originally published in the Hyde Park neighborhood on the South Side, Dawn extolled the virtues of “100 percent Americanism” and in its first issue made this claim to brotherhood: Not to advocate the oppression of any people, white or black. Not to malign anyone. Not to foster hatred in any way, but for the purpose of bringing together in whose union all one hundred percent Americans, The Dawn enters the field. Brazenly, as we will be quoted, we announce “our creed” and what could be more glorious than the creed of the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan. From October 21, 1922, until its final edition of February 9, 1924, Dawn was published weekly, coming out every Saturday at a price of ten cents. With the exception of its somewhat crudely drawn cover, Dawn was a small but professional publication that kept readers informed of Klan-related activities nationally and locally.

In the winter of 1922–23, the Chicago City Council began to investigate Chicago firemen suspected to be members of the Klan. Ultimately, the firemen were relocated or asked to resign. 16 | Chicago History | Fall 2006

The AUL sponsored a six-day event at the Chicago Coliseum in the spring of 1923. The advertisement in Tolerance (above) stated, “Proceeds to be devoted to [the fight against the Ku Klux Klan] and we expect everyone to do their duty.”

Letters to the editor, editorials, advertisements for local businesses, and classifieds gave the paper a mainstream look. Generally eschewing the overt racism one might expect from a Klan publication, Dawn tended to focus on its anti-Catholic, anti-immigrant theme. In its drive for public acceptance, the Klan of the 1920s portrayed the threat of Catholicism not in religious terms, but political. According to Evans, “The real objection to Romanism in America is not that it is a religion—which is no objection at all—but that it is a church in politics; an organized, disciplined, powerful rival to every political government.” The Chicago Klan attempted to flex its political muscle in response to two legal moves by the city of Chicago and the state of Illinois. The first was the City Council’s investigation of Chicago firemen suspected of being Klansmen. As a result of the investigation, Fire Commissioner John F. Cullerton asked Fire Marshall Arthur F. Seyferlich to force a reputed Klan recruiter to retire and scatter four other firemen to widely separated stations. The reputed recruiter, Fireman George Green, was asked to retire but allowed to keep his pension. The other four were all members of engine company no. 117, stationed at Chicago and Laramie Avenues. Cullerton defended the decision by stating, “Consider the public danger of a situation should firemen refuse to extinguish a blaze because the owner or occupant of a building belongs to a race or creed opposed by a secret order to which they might belong.” The Chicago Tribune reported that two of the transferred firemen were “hit hard” by orders that placed one of them in “the heart of the Ghetto,” engine company no. 6, at 559 South Maxwell

Street, and the other “into the center of a Polish district,” hook and ladder company no. 19, at Chicago Avenue and May Street. Largely as a result of the city council’s actions, Republican State Representative Adelbert H. Roberts of Chicago’s Third District introduced an anti-mask bill in the Illinois Legislature on January 16, 1923. Designed to outlaw public displays by secret societies, the measure became law in the summer of 1923. Faced with its first serious legal challenges, the Chicago Klan reacted by running or supporting local politicians in the upcoming elections. In the Republican mayoral primary, Arthur M. Millard, a political unknown, finished a surprising third ahead of Municipal Court Judge Bernard P. Barassa. Millard, rumored to be a Klan candidate, garnered 51,054 votes in an almostsecret campaign, offering some indication of the Klan’s strength in Chicago in 1923. The victor in the Republican primary, Arthur C. Lueder, a Lutheran, faced Democrat William E. Dever, a Catholic. Rumors of Klan support for Lueder were fanned by the distribution of anti-Catholic pamphlets throughout the campaign. The Chicago Defender’s endorsement of Dever offset the antiCatholic vote, and Dever’s election by 105,000 votes was interpreted as a decisive defeat for the Chicago Klan. The aldermanic elections saw similar results. Klan-backed candidates in the Eighth, Thirty-seventh, Thirty-ninth, and Fortieth Wards were all soundly defeated. The American Unity League arose as the greatest opposition to the Chicago Klan. Founded on June 21, 1922, by Robert H. Shepherd, Grady K. Rutledge, and

Dawn printed many advertisements for Klan-friendly businesses and products, including the “Klan-Lite,” which was described as a “work of art” and offered for homes with or without electricity. Klan Moves North | 17

Joseph G. Keller, the AUL’s sole purpose was the eradication of the Ku Klux Klan. Its main weapon was the weekly newspaper, Tolerance, which was sold at newsstands, bus stops, and Catholic churches for a dime. The two publications, Dawn and Tolerance, became the focus of the ongoing battle over the Klan in Chicago. By 1923, the majority of the editorial space in Dawn was devoted to discrediting its opponent. The intensity of this rivalry resulted in a high-stakes struggle, complete with intrigue, traitors, payoffs, double-crosses, and lawsuits. The two publications had several similarities. Both were weeklies of similar size and length. Both began publication in the fall of 1922, and neither lasted beyond the middle of the decade: Dawn stopped publication in February 1924, Tolerance lasted until January 1925. Dawn claimed a Chicago circulation of 35,000 and was published more consistently. Tolerance managed to sell 150,000 copies in its heyday, but due to legal problems, was forced to shut down operations for several weeks twice during its short run. Dawn was also able to procure more advertising from local merchants, lawyers, contractors, undertakers, and restaurants. At least initially, scores of local businessmen—especially on the South Side and in the Loop—were eager to advertise in the publication. A local coffee company stressed their “Kuality, Koffee, and Kourtesy” in their ad. In assessing how best to attack the Klan, the AUL learned well the lessons of the past. Exposing the Klan’s beliefs and tactics was ineffective and counterproductive; their ideals appealed to many Americans, as evidenced by the success of Birth of a Nation and the Klan’s growth after the New York World’s exposé. Instead, the AUL reasoned that the way to bring down the Klan was to expose the members themselves. As Louisiana Governor John Parker told an AUL audience in Chicago, “Tell their neighbors just who these people are who seek to lie hidden while they plot against the community and the nation, and their neighbors will take care of them.” On September 17, 1922, in its first issue, Tolerance listed the names, addresses, and occupations of 150 Chicago Klansmen. AUL chairman Patrick H. O’Donnell introduced the “visibility campaign” and stated the policy of the newspaper:

investigators, but the bulk of the names came from former Klansmen. Some had been banished from the Klan, some had left over power struggles, and some were double agents. Dr. Mortimer E. Emrick, who provided the AUL with its first list, was a leader in the Woodlawn Klan who resigned after unsuccessfully attempting to reorganize the South Side chapters. Dixie Shea, W. A. Hill, and Louis D. Wisbrod were all AUL informants who managed to secure positions inside the Klan. The most prolific name supplier, however, was a professional musician named Marvin V. Hinshaw, a former recruiter for the Great Lakes chapter who was banished for “conduct unbecoming a Klansman.” Hinshaw approached the AUL claiming to have a “friend in Chattanooga, Tennessee,” who had a list of six thousand names of Chicago Klansmen for sale at the rate of three dollars per name or $18,000. Hinshaw rejected the AUL’s initial counteroffer of $600. When the offer was raised to $2,500, Hinshaw showed up at AUL headquarters at 127 North Dearborn with the names. Lulled into a false sense of security by an impressive stack of cash on the table, Hinshaw gave the names to Grady Rutledge, editor of Tolerance and secretary of the AUL. Rutledge excused himself to another room to supposedly compare the list with others acquired by the AUL. Sprinting out a back door, Rutledge dashed through the Loop to the law offices of Patrick O’Donnell at Clark and Randolph Streets, where the list was locked in a secret vault. Hinshaw’s payout turned out to be less than $350.

We feel that the publication of the names of those who belong to the Klan will be a blow that the masked organization cannot survive. Many Klansmen are in business or the professions and are dependent largely upon patronage of those groups they classify as alien. We feel that it is only just that their attitude be made public. The trick, of course, was gaining access to the names, as Klan membership rolls were a closely guarded secret. The American Unity League employed as many as seven 18 | Chicago History | Fall 2006

Attorney Patrick H. O’Donnell, pictured here in 1908, became the chairman of the AUL.

Grady Rutledge’s articles in Dawn included a first-hand account of the “real” story behind the selling of Klansman’s names to Tolerance.

Klan Moves North | 19

By January 1923, Tolerance had printed the names of four thousand Chicago Klansmen and was prepared to print six thousand more. It is impossible to determine exactly how many Klansmen renounced their memberships as a result of the listings, but evidence suggests the number was substantial. Several small businessmen testified in court that their businesses suffered as a result of being exposed by Tolerance. The president of the Washington Park National Bank was listed in the fifth issue of Tolerance, and by the time the bank’s board of directors convinced him to step down, the bank had lost thousands of dollars in withdrawals. “I signed a petition for membership in the Klan several months ago,” the bank president lamented. “But I did not know it was anything else than an ordinary fraternal order.” The most telling evidence of the effectiveness of Tolerance’s visibility campaign was the Klan’s reaction to it. Blasting the group’s methods as a “miserable weapon of cowards,” the Klan sued the AUL for revealing its secrets and temporarily succeeded in stopping the publication of Tolerance. Printing Klan membership rosters proved to be a mixed blessing for the AUL. Undeniably effective as a tool for reducing the ranks of the Chicago Klan, the visibility campaign inevitably included inaccurate listings. Some names were originally forged by Klan recruiters to artificially bolster their recruiting numbers and others were listed by the informants out of spite. The careers of several apparently innocent people were harmed, and the American Unity League itself was irreparably damaged by dissension and lawsuits as a result of printing erroneous names. A plumber and a physician each sued the AUL for $25,000, and J. William Brooks, an attorney with an undertaking business, filed a $100,000-slander suit. Brooks claimed that as a result of his name being published “practically all his clients had deserted him, members of his parish church avoided him, and the undertaking business was ruined.” William Wrigley Jr., millionaire gum manufacturer and owner of the Chicago Cubs, filed the most damaging of the suits against the AUL. Tolerance had gained possession of a Klan application in Wrigley’s name with his signature apparently on it. After the editors published his name, Wrigley filed a $50,000 lawsuit against the American Unity League and offered another $50,000 to charity in the name of anyone who could prove he had signed a membership application for the Klan. The signature, which resembled the fictional signature printed on the wrapper of Wrigley chewing gum but bore no likeness to his actual signature, was described by the gum manufacturer as “a rank forgery and about as much like mine as the north pole [is] like Vesuvius.” Eventually, the Klansman who claimed to have taken Wrigley’s application admitted it was a forgery. 20 | Chicago History | Fall 2006

The demise of the AUL began when the editors incorrectly published William Wrigley Jr.’s name as part of their visibility campaign. The action initiated a serious lawsuit and caused dissent among AUL founders, which ultimately led to Rutledge leaving the organization.

Dr. Hiram Evans came to Illinois in 1923 in an attempt to reunite and restructure the Chicago Klan. His visit was advertised in Dawn. Klan Moves North | 21

As local Klan membership declined, the intensity of the content published in Dawn increased. Printed in October 1923, this cartoon ran below the headline, “The ‘Man on the Fence’ Becomes Uncomfortable,” and urged the indecisive to join the powerful members of the Klan.

22 | Chicago History | Fall 2006

Grady Rutledge later charged that AUL chairman Patrick O’Donnell was behind the Wrigley scheme from the start. Rutledge claimed that soon after Tolerance began publishing names, O’Donnell instructed him and treasurer Robert Shepherd to “get the goods” on Wrigley, stating that he was sure Wrigley was a member of the Klan. Rutledge contacted his usual informants but could not find evidence linking Wrigley to the Klan. Several weeks later, after returning from out of town, Rutledge discovered that Shepherd had secured an application to the Klan in Wrigley’s name. Rutledge found this unusual for several reasons. “Of all the names published in Tolerance while I was editor, that of William Wrigley, Jr. was the only one that came through a separate source,” he said. “It was the only name I ever knew of coming to us singly. And it was the only name that we ever had that was backed up by an original questionnaire—forged or otherwise.” When O’Donnell and Shepherd published Wrigley’s name over Rutledge’s objections, he secured an injunction restraining O’Donnell and Shepherd from interfering with the publication. When O’Donnell and Shepherd won the ensuing legal battle, Rutledge left the AUL and defected to the Klan. Rutledge’s surprising about-face was comprehensive. He not only joined the Klan; he became the featured writer for Dawn for the remainder of the newspaper’s run. Rutledge’s articles exposing the inner workings of the AUL and Tolerance became the centerpieces of the newspaper. In the articles, Rutledge lambasted his former colleagues. He maintained that the organization’s membership was grossly exaggerated and alleged, “Tolerance editors have no evidence of Klan membership against nine out of ten men whose names they publish.” The disgruntled founder of the AUL went as far as to suggest, “Anyone wishing to contribute his hard earned money to finance O’Donnell, Shepherd, et al. in their effort to unite Catholics, Jews, Negroes and foreigners in a fight with White, Gentile, Native, Protestant Americans for the control of our country should send his contribution to the Pope’s branch office, AUL headquarters, 127 N. Dearborn Street, Chicago.” By late 1923, internal dissension and the AUL’s visibility campaign began to take their toll on the Chicago Klan. On the national level, founder William Simmons had been duped into accepting a ceremonial position. Meeting in Atlanta, Klan leaders turned control over to Dallas dentist Hiram W. Evans. By the time Simmons discovered the ruse, it was too late. The group adopted changes that stripped him of any real power and sold land he had set aside for building a university. Incensed, Simmons decided to form a women’s Klan. He took control of the White Disagreement among the AUL eventually made headlines as the editors went to court to determine the future of the organization. Klan Moves North | 23

In an effort to strengthen the organization and encourage new members, the Klan held an afternoon festival in the fall of 1923. Advertisements announced that all “eligible� friends and families were welcome. 24 | Chicago History | Fall 2006

American Protestant Study Club of Oklahoma, changed its name to Kamelia, and called it the official ladies’ auxiliary of the Ku Klux Klan. Simmons’s failed attempt to regain control resulted in a tangle of lawsuits, which eventually sent him into quiet retirement and solidified Evans’s hold over the Klan. In Chicago, the national power struggle created local dissension. Simmons visited in July 1923 and was able to corral the loyalty of four of the city’s largest and most influential chapters. Evans immediately suspended the charters of the four groups and came to Chicago in August to try to quell the schism by urging all members to adhere to the duly constituted authorities in Atlanta. Despite the loyal support of Illinois leader Charles Palmer, the Chicago chapters remained deeply divided. In November 1923, Palmer dismissed the presidents of ten Chicago chapters; the following year, he banished fourteen thousand Illinois members for disloyalty. The upheaval caused the national office to replace Palmer by the end of 1924. By then the Chicago Klan was in disarray and the end was near. Dawn had ceased publication in February 1924, and in May, all twenty-six Chicago chapters had merged into one unit, none of them retaining enough members to operate on their own. The Ku Klux Klan’s emergence in Chicago in the 1920s involved a significant number of people for a short period of time. As part of a nationwide resurgence of the Klan, the Chicago movement drew headlines more for the threat it posed than for any particularly newsworthy events. The most significant aspect of the rise of the Ku Klux Klan in Chicago in the 1920s is the relative insignificance with which it was perceived at the time. Racism and bigotry were so much a part of many people’s lives that the resurgence of the Klan did not inspire the kind of revulsion and indignation that would be expected in modern society. In many ways, and to many people, the Ku Klux Klan was just another fraternal organization. Chicagoans joined the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s by the thousands because they believed in its message of white, Protestant supremacy. Thousands left the Klan when their identities were revealed to their Catholic, Jewish, and African American neighbors, who then refused to do business with them. The remainder left when it became apparent that the organization was unable to prevent the changes occurring in society. Evidence of Klan activity was sporadically reported in Chicago in 1925 and 1926, but for all practical purposes, the Chicago Klan was dead. David Craine teaches American history at St. Patrick High School in Chicago. He is a graduate history student at Northeastern Illinois University.

Throughout the early 1920s, the Chicago Klan continued to target Catholics and immigrants as well as corrupt politicians and criminals.

I L LU S T R AT I O N S | 4, courtesy of the Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-64768; 5, reprinted from Dawn, 10 Feb. 1923; 6 left, reprinted from the Chicago Tribune, 19 Sept. 1915; 6 right, reprinted from the Chicago Tribune, 1 Oct. 1922; 7, reprinted from Dawn, 5 Jan. 1924; 8, courtesy of the Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-104018; 9 top, Chicago History Museum Daily News collection, DN-0074501; 9 bottom, reprinted from Dawn, 8 Dec. 1923; 10, reprinted from Dawn; 11, map from Kenneth T. Jackson’s The Ku Klux Klan in the City, 1915–1930, 1st ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1967); 12, reprinted from the Chicago Tribune, 17 Aug. 1921; 13, reprinted from the Chicago Tribune, 21 Aug. 1922; 14, cover of Dawn, 21 April 1923; 15, cover of Tolerance, 28 Jan. 1923; 16, reprinted from the Chicago Tribune, 31 Jan. 1922; 17 top, reprinted from Tolerance, 28 Jan. 1923; 17 bottom, reprinted from Dawn; 18, Chicago History Museum Daily News collection, DN-0005776; 19, reprinted from Dawn; 20, reprinted from the Chicago Tribune, 4 Feb. 1923; 21, reprinted from Dawn; 22, reprinted from Dawn, 13 Oct. 1923; 23, reprinted from the Chicago Tribune, 3 Feb. 1923; 24, reprinted from Dawn; 25, reprinted from Dawn, 11 Nov. 1922. F O R F U RT H E R R E A D I N G | Kenneth T. Jackson’s The Ku Klux Klan in the City, 1915–1930, 2nd ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1967; Chicago: I.R. Dee, 1992) is a comprehensive look at the nationwide Klan movement in the early twentieth century. Additional texts of interest include David Mark Chalmers’s Hooded Americanism: The History of the Ku Klux Klan, 3rd ed. (1981; repr., Durham: Duke University Press, 1987) and Kathleen M. Blee’s Women of the Klan: Racism and Gender in the 1920s (Berkeley: University of California Press, Klan Moves North | 25

“We Belong in Washington Park” African American lawyers and businessmen led the long struggle against racially restrictive covenants. TRUMAN K. GIBSON JR.

I

t’s a moment pregnant with possibilities. For the black family in Lorraine Hansberry’s play A Raisin in the Sun, a yearning for a better life inspires a hope of a warm welcome, a gesture of acceptance, and an expression of neighborly feeling from their soon-to-be neighbors who are white. For us in the audience, foreboding makes us almost want to avert our eyes as we know that something quite different from the family’s aspirations is about to befall them. Still, thanks to the power of Hansberry’s words and the depth of the performances by the actors (Sidney Poitier, Ruby Dee, Claudia McNeil, and the others in the movie adapted from the 1959 play), we too are stunned when the bland young man from the Clybourne Park Improvement Association reveals that the white neighborhood wants to buy back from the black family the house on which they’ve just made a down payment. “You people” is the phrase he uses over and over, working himself up to his point: “I want you to believe me when I tell you that race prejudice simply doesn’t enter into it. It’s a matter of the people of Clybourne Park believing, rightly or wrongly, as I say, that for the happiness of all concerned that our Negro families are happier when they live in their own communities.” The family is crushed. We in the audience are repulsed by the soulless ugliness of the moment. Yet, the reality that served as the inspiration for this play was much harsher. Whereas the black family in the play confronted a 1950s white neighborhood that wanted to buy them out, that was in effect trying to talk them out of coming into the area by offering a quick profit on the home, Carl Hansberry,

26 | Chicago History | Fall 2006

This article is excerpted from Knocking Down Barriers: My Fight for Black America by Truman K. Gibson Jr., recently published by Northwestern University Press. Gibson was the civilian aide to the secretary of war during World War II, a member of two presidential advisory committees, and the first African American to be awarded the Presidential Medal of Merit. Above: Gibson as a young attorney in Chicago.

Lorraine Hansberry (left) received worldwide acclaim (right) for her play A Raisin in the Sun, inspired by her father’s fight against racially restrictive covenants. Below: The original Raisin cast featured Louis Gossett, Ruby Dee, and Sidney Poitier.

We Belong | 27

As African Americans moved into formerly all-white neighborhoods, many became victims of bombings. This map from a 1922 study by the Chicago Commission on Race Relations shows homes bombed during race conflicts over housing between 1917 and 1921.

28 | Chicago History | Fall 2006

Lorraine’s father, faced the full weight of a legal system out to deny him by force of law the right to move his family into a white neighborhood during the Depression. Chicago in the first third of the twentieth century was of two minds about its burgeoning black population. While its industries, straining to meet the production demands of World War I, had thrown open their arms to the African Americans migrating from the South, white Chicagoans did not turn out the welcome mat for blacks seeking to put down roots in their neighborhoods. The city’s political power structure struggled to contain African Americans within the already established black belt on the South Side. A bomb, not a welcome wagon, all too often announced the arrival of a black family to a previously all-white block. Still, racial violence was not an attribute by which any city wanted to be known. Chicago’s city fathers and business community had recoiled in horror from the bloody 1919 race riot, and law-abiding Chicagoans were not happy with the brand of lawlessness burned on the city’s good name by Al Capone and other gangsters during Prohibition.

So a nonviolent way had to be found to keep blacks out of white neighborhoods. Indeed, the bombings abated as the city adopted a more effective and legalistic approach—the restrictive real estate covenant. Now, restrictive covenants were not, and are not, unusual in real estate contracts to protect property values. They lay down parameters on, for instance, right of way, utilities, or the number of people who can occupy a structure. Applying the covenants to race—in effect declaring that blacks had to be kept out of communities to preserve home values—became widespread in the 1920s. A typical example was the racial covenant for the Washington Park subdivision on Chicago’s South Side, written in 1927. This was the covenant that Hansberry challenged in the mid-1930s. This document prohibited the sale, rental, and leasing to Negroes of residential property in a defined area. The crude language of the covenant defined a Negro as “every person having oneeighth part or more of negro blood, or having any appreciable mixture of negro blood, and every person who is what is commonly known as a ‘Colored person.’” The

Chicago’s devastating 1919 Race Riot created a rift between African American and white communities that lasted for decades. We Belong | 29

Earl Dickerson, legal counsel for the NAACP, took on Carl Hansberry’s case as he challenged the racial covenant of the Washington Park subdivision on Chicago’s South Side. 30 | Chicago History | Fall 2006

Businessman Harry Pace (below) tried to develop property in Washington Park (above), and became part of the Hansberry case.

only exceptions to the ban on black occupation of living quarters in a covenantrestricted neighborhood were African Americans employed as janitors, chauffeurs, or house servants, who could live “in the basement or in a barn or garage in the rear, or . . . servants’ quarters.” Hansberry was an astute businessman who had found prosperity in buying three-flat apartment buildings and converting them to ten-flat kitchenette structures. The sturdy homes and apartment buildings in the Washington Park subdivision appealed to his business instincts. He set his sights on a three-flat brick building at 6140 South Rhodes Avenue, put down earnest money, got a mortgage, and proceeded to move his wife, Nannie, and their four children into the first-floor unit. Knowing that he was in for a hard legal fight, Hansberry and his attorney, C. Francis Stradford, approached the NAACP. The star legal counsel for the NAACP was Earl Dickerson, also general counsel for my father’s firm,

Supreme Liberty Life Insurance. Dickerson already had made a name for himself as an activist in the NAACP and the liberal Chicago Lawyers Guild, put his stamp on the black business community through his work as vice president and general counsel for the Supreme Life firm, earned a reputation as an effective litigator, and, from his service as an assistant Illinois attorney general, gained a keen insight into the workings of the courts and the power structure of Chicago. He was a natural selection for anyone wishing to challenge the restrictive racial covenant. Dickerson presented Hansberry’s case to the insurance company, and it readily agreed to put up the money for the forty-four-hundred dollar note on the property and to fund the legal challenge to these bigoted contracts. Supreme made that mortgage with eyes wide open to the risks and expense of a long legal fight. My father chaired the executive committee that approved the mortgage for Hansberry to buy the property. Although the decision was We Belong | 31

made with little discussion, my father, Dickerson, and the others knew that they faced an uphill fight. Only a few years earlier, the U.S. Supreme Court had ruled in favor of racial covenants. Still, the overwhelming sentiment was in favor of another challenge. Irvin C. Mollison and I were recruited for the struggle as pro bono attorneys. Hansberry’s property wasn’t the only stab at black ownership within the Washington Park subdivision. My father’s business associate, Harry Pace, also bought a building nearby, and that became part of the Hansberry case. Independent of our action, a black physician named James Lowell Hall bought a dwelling west of the building at Sixtieth Street and Vernon Avenue in which my parents rented an apartment. Such was the arbitrary and capricious nature of the covenant that while our building was not covered by it, the one Hall bought was. Hansberry and Hall both moved their families into the buildings and were promptly evicted on the basis of the covenant. As evidenced by Raisin, that made a powerful

impression on Lorraine, who couldn’t have been more than seven or eight years of age at that time. The upheaval must have been traumatic. Hansberry lived well. He already owned a very pleasant home on Forestville Avenue, a short street of houses for the affluent between Forty-fifth and Forty-seventh Streets. Almost overnight, she was uprooted from that familiar home, moved into the ground-floor apartment of the three-flat building on Rhodes, and then hustled back to Forestville Avenue after eviction. No man puts his family through that lightly. The compelling factor for Hansberry that made that bruising turmoil necessary was the goal of busting the covenant. After forcibly getting Hansberry’s family out of the building, the Woodlawn Property Owners Association, as the covenant’s governing body was known, filed papers in circuit court to force the real estate broker to relinquish ownership of the building. The legal battle had been joined. At the center of it, plotting strategy and articulating the case against the covenant, was Dickerson.

The Woodlawn neighborhood (above) became the site of legal battles over racially restrictive covenants. 32 | Chicago History | Fall 2006

The Woodlawn Property Owners Association was the racial covenant’s governing body. As this 1929 letter indicates, the association promoted the “work of restricting Woodlawn to white people.” We Belong | 33

Restricted to certain neighborhoods, Chicago’s African American community created a “Black Belt” on the South Side that stretched from Thirty-first Street past Sixty-third Street. 34 | Chicago History | Fall 2006

The Chicago Defender condemned the city’s segregated Black Belt and the restrictive covenants among property owners in areas adjacent to the University of Chicago.

The chance for Hansberry, Hall, and Pace to buy property arose unexpectedly out of bickering and betrayal inside the Woodlawn Property Owners Association. Its executive secretary and prime conspirator in buttressing the covenant had been an individual named James Joseph Burke. He quit the association on March 1, 1937, in a dispute over—what else?—money. It was a bitter parting. According to the complaint the association filed against the Hansberry purchase, Burke resigned after, on various occasions, hurling threats at his erstwhile comrades. “I’m going to put niggers into twenty or thirty buildings in the Washington Park subdivision,” he was quoted as saying within four to six weeks before he left. “I will get even with the Woodlawn Property Owners Association by putting niggers in every block,” he declared on another occasion. “You property owners in the subdivision will soon have headaches.” And, he added, “I will get even with the Association and with certain directors of said Association if that is the last thing I do.” He then “conspired,” according to the complaint, to sell the Rhodes Avenue property to Hansberry and the nearby building on Sixtieth Street to Pace. Indeed, a conspiracy existed, but it was a necessary conspiracy, intrigue aimed at righting a wrong.

As the youngest attorney, I was the junior partner on the legal team and got the most tedious job. For the covenant to be in force, it had to be signed by 95 percent of the home owners in the covered area. I spent much of the next year and a half working in the law library at City Hall in the Loop and at the nearby office of the Cook County Recorder of Deeds. Poring over legal descriptions of the property in the stacks at the law library, I transcribed, in my bad handwriting, the characteristics and boundaries of the plots in the subdivision. Then at the recorder’s office, I hunted up the deeds to the properties and compared the signatures on them to those on the covenant. It was a laborious, tiresome, boring task. Squinting to make out the signatures was hard on my eyes; days hunched over property records left my back aching, and copying reams of legal papers cramped my hand. But I wasn’t married at the time, so my time was my own, and although I wasn’t paid, expenses back then weren’t what they are today. More important, the payoff was big. My long hours revealed that only 54 percent of the property owners actually had signed the covenant. We thought we had the stake to drive through the heart of this racial covenant. During the trial in circuit court, I spent almost ten days on the witness stand explaining my research, going over individual pieces of property to show that I had the goods on them. But the white home owners’ association anted up what turned out to be an ace in the hole. Back in 1928, Burke had cooked up a fraudulent suit, a friendly legal action which maneuvered a circuit court judge into accepting the covenant as valid and binding. This was precedent, the judge in our case declared—despite the evidence I had presented, despite the fact that barely more than half of the required 95 percent of home owners had signed the covenant, and despite testimony from Burke that the 1928 action was the work of collusion. The legal term employed by the court was res judicata, meaning the issue had been decided, had been settled. We, of course, appealed. Litigation is expensive. My best estimate is that Supreme Life pumped more than a hundred thousand dollars—a huge sum during the Depression—into fighting this case. But where did the money come from to pay the phalanx of attorneys representing the white home owners of this middle-class neighborhood? The University of Chicago! Dickerson, Mollison, and I—all graduates of the University of Chicago Law School—sought and got a meeting with university president Robert Maynard Hutchins, considered then and remembered today as a great liberal. We urged him to cut off university financing of the defense of the racist real estate contracts. He steadfastly refused. We Belong | 35

“It’s a matter of economics,” he lectured us. “The university has a huge investment in the South Side, and I’ve got to protect it.” As we pressed our case, he became increasingly irritated and finally blurted out, “Why don’t you people stay where you belong!” “You people.” Hutchins would never say the word “nigger,” but the phrase “you people” carried the same message. That was the end of the hope that the University of Chicago would step up to do the right thing. Yet, those words from this icon of progressive politics grated on me long after. In fact, some years later after I had gone to work for the War Department, I ran into my old Chicago Law School friend Ed Levi in Washington, where he was employed by the attorney general. I hadn’t seen him for several years, and as we exchanged pleasantries, the resentment over that insult bubbled up and I said, “Ed, why don’t you let Hutchins know we belong everywhere?” I think the vehemence of my feelings left him nonplussed. He muttered something about that’s how things are and isn’t that awful, and went on his way. Ed was a good man, but he didn’t know how to answer my anger. As our case worked its way to the Illinois Supreme Court and then finally to the U.S. Supreme Court, I would occasionally see Hansberry, and I even had him as a client in a business matter—a deal that inspired another plotline in A Raisin in the Sun. In the play, the family matriarch comes into ten thousand dollars from an insurance policy paid on the death of her husband. There are competing interests within the family for the money. Her daughter wants part of it to attend medical school. The Sidney Poitier character is consumed with ambition to invest it in a liquor store with a couple of other men so he can become his own boss instead of serving out his life as a chauffeur to a white man. The mother says no, invests part of the money in a down payment on the house in the white neighborhood, and entrusts the rest to her son to deposit in the bank. He promptly takes the money to the acquaintance who is putting together the liquor store deal, and, of course, that man disappears with the money. Hansberry, as I’ve noted, made a good living because he was an astute businessman. But like too many people, then and now, and like the Sidney Poitier character, he yearned for the surefire chance to make a killing. He socialized with the policy guys, which served only to feed his appetite for the fast buck. At the time oil exploration was recognized as a lucrative business, thanks to the ever growing popularity of the automobile and the ever increasing incorporation of the internal combustion Hansberry and Pace took their fight against restrictive covenants to the Illinois State Supreme Court in 1939. Earl B. Dickerson and Truman K. Gibson Jr. led their legal team. 36 | Chicago History | Fall 2006

Gibson recalls that University of Chicago president Robert Maynard Hutchins (above) refused to stop university financial support of the racist real estate contracts. We Belong | 37

Gibson’s law office was in the Supreme Liberty Life Building on Thirty-fifth Street.

38 | Chicago History | Fall 2006

engine into American industry. Speculation in petroleum wells was rampant. Today, we think of oil as an asset of the American Southwest and the Middle East. However, oil drilling first made fortunes in Pennsylvania, and oil had been struck in downstate Illinois. Now, a couple of businessmen named Horne and Faulkner (I’ve forgotten their first names) persuaded Hansberry and several other men to invest in the mineral rights to land in Centralia, Illinois, that they touted as oil

fields likely to produce a bonanza for those bold enough to cough up the money for exploratory drilling. Hansberry and the others bought it hook, line, and sinker. One weekend we drove down to Centralia, and they spent hours gazing at the property, walking around it, and imagining oil derricks pumping black gold out of the ground, their heads filled with visions of oil dollars gushing out of the rich agricultural dirt of central Illinois. Naturally, the upshot was that Hansberry’s property pro-

duced about two teaspoons of oil, and Horne and Faulkner skipped town with his money and that of the other investors. Like the Poitier character, they had been cheated by a couple of sharp guys preying on others’ hunger for quick riches. Fortunately, no one had invested his life savings in this scheme. It’s an ill wind that blows no good; my law partner Mollison also put some money in this scheme. His property turned out to be a drainage ditch running by the socalled oil field, so it looked like he had got the worst deal of all. However, his drilling operation actually struck oil, and, while its production didn’t make him an oil baron, the well produced enough petroleum for him to earn a good return on his investment. His success prolonged the hope of the other investors but to no avail. Horne and Faulkner had had offices next to mine in the Supreme Life building at Thirty-fifth Street. They had fooled me, too, but fortunately, I had not invested in their oil scheme. Not too long after the oil scheme fizzled, on October 15, 1939, the Illinois Supreme Court rendered its decision on our appeal. The ruling began with a lot of flowery praise for the briefs presented by both sides. They were “very studiously prepared,” were read by the justices “with the greatest interest and enjoyment,” were appreciated for the quality of the “language employed,” and some of their arguments were regarded as “almost classical.” For us, the justices no doubt intended that fulsome and condescending praise to soften the blow to come. They rejected our appeal, declaring that res judicata indeed applied. Incredibly, the court found that the stipulation resulting from the contrived lawsuit was untrue but ruled that the sweetheart deal was not fraudulent or collusive. We took our case to the United States Supreme Court. The high court heard arguments October 25, 1940. We traveled to Washington several days ahead of that to prepare. As I said, I wasn’t being paid, so I stayed with Robert Ming, a law professor at Howard University and a close friend who had managed to graduate at the top of his class from the University of Chicago Law School even though he spent his last year presiding over a blackjack game rather than in class. Two nights before the arguments to the high court, we laid out our case to sixty students and faculty members at Howard in an auditorium on campus. Listening and questioning us were some of the best minds in America’s black intelligentsia. William Hastie, a man who was to play such an important role in my life and who had become the first black federal judge, was dean of Howard’s Law School. Others from the faculty included Jim Nabrit Sr., a top graduate of the Northwestern University Law School and later president of Howard; Bernard Jefferson, a recent graduate of Harvard who would become a distinguished judge in California, and We Belong | 39

In 1940, three years after Dickerson filed the initial suit, the United States Supreme Court finally overturned the Illinois Supreme Court’s decision. The Court ruled that “the property owners agreements barring Negroes from residing in an area . . . are non-existent.”

40 | Chicago History | Fall 2006

In 1943, Carl Hansberry published this guide to help other African Americans enter the business world.

my old friend Bob Ming. Bill Hastie was an intense questioner. His time in Chicago enabled Nabrit to pose especially detailed and relevant questions. The rehearsal went on for three or four hours. Dickerson recited his oral argument. Back in Chicago, we had gone over it countless times, looking for weak logic, revising and refining our legal reasoning, and polishing the phrasing and structure of our argument. The audience was clearly impressed. I took the stage to explain the research on the covenant’s signers that I had done and fielded all manner of probing questions. Before we could present our case to the U.S. Supreme Court, we had to be admitted to its bar. The morning before our case was to be heard, Mollison, Moore, Dickerson, and I showed up for the swearing-in ceremony. Of course, I had never visited the court before. We were among a troop of attorneys who marched into the courtroom in late morning to be formally sworn in. Our hearts were fluttering. I was awed by the majesty of the courtroom, the bench, and the justices themselves. We were in quite a daze and didn’t say anything but yes when called upon by the presiding justice.

Finally, with the next day came the main event. Mollison, Moore, and I took our seats while Dickerson assumed the lectern. He was the supreme egotist who didn’t suffer fools gladly. But that day he proved beyond a shadow of a doubt that his own high opinion of himself was richly deserved. To say that Dickerson did extremely well is an understatement. He made his presentation with aplomb, forcefully advancing our arguments and agilely responding to the challenging questions from several of the justices. Ours was a three-pronged attack: the concept of the covenant denied equal protection of the law guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment, the Washington Park subdivision covenant was invalid because of the inadequacy of the signatures, and res judicata did not apply because the suit on which it was based was a trumped-up affair. The pattern of questioning, led by Justice James McReynolds from Tennessee, avoided the conceptual argument and focused on the technical questions of res judicata, signatures, and the sanctity of contracts. The high-priced Loop attorneys representing the Woodlawn Association and funded by the University of Chicago, led by McKenzie Shannon, also came under sharp questioning. We Belong | 41

The defeat of the Woodlawn real estate contract inspired other actions against racially restrictive covenants, including this downtown conference in 1946. 42 | Chicago History | Fall 2006

The questions were precise, addressing specific legal issues of contract, but the experience was not intense. The justices listened attentively. After our hour-long presentation, we walked away convinced that Dickerson had done a fine job in articulating our case, though of course we had no way of knowing how it had played with the court. We retired to Ming’s apartment to replay over and over the day’s events and to unwind by playing a little poker. As it turned out, we had to wait only three weeks for a decision. A quick ruling from the U.S. Supreme Court was very unusual. Normally the justices considered an issue for months, typically hearing a case in the fall and rendering opinion in late May. A decision after only three weeks was surprising. The results, however, showed that the court wasn’t ready to tackle the constitutional issues we presented regarding Fourteenth Amendment protections and wanted only to concentrate on the technical issues. Still, the result was a vindication of my research, the big payoff for those hours, days, weeks, and months spent stooped over deeds and property descriptions. Knocking down the case for res judicata, the justices declared that no one was bound by the contrived lawsuit and that because my research showed that only 54 percent—not 95 percent—of the home owners had signed the covenant, no restriction was in force. The ruling—while short of a landmark decision outlawing all such contractual language, which had to wait for cases from Michigan and Missouri in 1948—was a resounding victory. It meant that each challenge to the covenant, that each contested sale of a home, had to be litigated individually—a stipulation that made it economically impossible to defend the Washington Park subdivision contracts. Hansberry and his family at long last could move into their new home. The decision had an immediate and profound impact, igniting one of the first waves of the white flight phenomenon that was to plague Chicago and other urban centers for decades to come. White families panicked and pushed their homes onto a crowded market and sold them cheaply. Black real estate speculators made a killing. I represented Claude Barnett, director of the Associated Negro Press. He bought three buildings and confided to me that they were the best investments he had ever made because they came at so little cost. Ironically, Hansberry didn’t live very long at the house he had waged such a long legal battle to acquire. After his wife died, he moved to Mexico in the 1940s. But even before that I had lost touch with him. Word of the Supreme Court’s decision reached me while I was fighting a lawsuit in Cook County Circuit Court. If there was a celebration dinner or party for Hansberry, Dickerson, and the others, I am unaware of it. I did write to the University of Chicago president Hutchins declaring, “We belong in the Washington Park subdivision. The Supreme Court says so.” He didn’t respond.

After racially restrictive covenants were lifted, some African American businessmen, including Associated Negro Press director Claude Barnett (above), made successful investments in real estate. I L L U S T R AT I O N S | 26, ICHi-39786; 27 top left, ICHi39781; 27 bottom left, from The Chicago Defender, February 2, 1959; 27 right, “Young Woman from Chicago Does Hit Play” by Roi Ottley, copyrighted February 14, 1959, Chicago Tribune Company. All rights reserved; 28, from The Negro in Chicago, Chicago Commission on Race Relations (University of Chicago Press, 1922); 29, ICHi-25571; 30, ICHi-39785; 31 top, from The Chicago Defender, August 1, 1936; 31 bottom, ICHi-39784; 32, ICHi-23193; 33, from Woodlawn Property Owners Association records, 1922–34, CHS; 34, adapted from map in The Negro in Chicago, Chicago Commission on Race Relations (University of Chicago Press, 1922); 35, from The Chicago Defender, July 24, 1937; 36, from The Chicago Defender, February 25, 1939; 37, ICHi-39782; 38–39, ICHi-39783; 40, from The Chicago Defender, November 23, 1940; 41, from Moving Forward! A Plan for the Negro’s Advancement in Business and Industry by Carl A. Hansberry, 1943, CHS; 42, Conference for the Elimination of Restrictive Covenants by the Chicago Council against Racial and Religious Discrimination, 1946, CHS; 43, ICHi-18378. F O R F U R T H E R R E A D I N G | The Chicago History Museum Research Center contains several volumes on racially restrictive convenants, including Racial Restrictive Covenants by Bernard J. Sheil and Loren Miller (Chicago Council Against Racial and Religious Discrimination, 1946); Proceedings from the 1946 Conference for the Elimination of Restrictive Covenants (Chicago Council Against Racial and Religious Discrimination); Restrictive Covenants by the Federation of Neighborhood Associations (Chicago: The Federation, 1944); and People vs. Property: Race Restrictive Covenants in Housing by Herman H. Long and Charles S. Johnson (Nashville: Fisk University Press, 1947).

We Belong | 43

44 | Chicago History | Fall 2006

Y E S T E R D AY ’ S C I T Y

Henry Field’s Legendary Expeditions S. J. REDMAN

M

Henry Field (left) and Dimna, an excavation specialist, examine a four-wheeled chariot, two wheels of which are exposed, during the 1927–28 expedition. The oldest-known wheels for transport were discovered at Kish; two are in the Field Museum’s collection.

useums build their collections through a variety of ways. Some receive artifacts following the death of a private collector. Many purchase or collect objects in exchange with other institutions. None of these traditional methods of collecting, however, bring to mind the glamour and adventure of the classic museum expedition. Henry Field, who began his career at the Field Museum as assistant curator in 1926 and became curator of physical anthropology there from 1934 to 1941, lived for this sort of odyssey. The remnants of some of Field’s legendary expeditions now rest in the Chicago museum that bears his family name, on the shelves of a department of anthropology storeroom. This collection consists of nearly four thousand catalogued artifacts obtained during his North Arabian Desert Expeditions in 1927 and 1928. Henry Field, the grand-nephew of department store giant Marshall Field, wanted to work in a museum from a very young age: “My first desire, after graduating from Oxford, was to work in a museum, and it had been my dream since childhood to return someday to Chicago. Both desire and dream were to be realized, for I received a position as assistant curator of physical anthropology at Field Museum of Natural History.” Marshall Field’s fortune and vast connections had helped found the Field Yesterday’s City | 45

Above: The groundbreaking ceremony for the new Field Museum building in 1917 included members of the administration, curators, and other museum staff. The museum moved from its building in Jackson Park (now the site of the Museum of Science and Industry) to its current location in the Museum Campus on Lake Michigan (opposite). Fredric Ward Putnam, chief anthropologist of the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893, (right) helped transform artifacts from the fair into exhibits for the new Field Columbian Museum. He worked at the museum until 1919.

46 | Chicago History | Fall 2006

Columbian Museum—now the Field Museum of Natural History—in 1894. When the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893 drew to a close, Marshall Field’s first museum donation allowed a team of anthropologists, including Franz Boas and Fredric Ward Putnam, to secure objects exhibited at the world’s fair for the new museum. Boas and Putnam, with the help of one hundred assistants, had orchestrated a massive campaign to organize fair’s enormously successful Anthropology Building. After Marshall Field died in 1906, his will bequeathed millions of dollars to help fund the new Field Museum building that opened in 1921. Marshall’s nephew (and Henry’s cousin) Stanley Field ran the museum as its president and, later, board chairman for fifty-six years until his death in 1964.

While Henry Field possessed obvious connections to the Field Museum, he also had a genuine passion and dedication for the museum’s disciplines. While studying at Oxford and Heidelberg under L. H. Dudley Buxton, one of the world’s top anthropologists, archaeologists, and historians, he became interested not only in the study of physical anthropology, but also prehistoric and ancient history. In late 1925, before Field had

completed his work at Oxford, his grand-uncle, Barbour Lathrop, gave him one thousand dollars to travel to the archaeological site of Kish in Iraq. The Field Museum had been participating in collaborative excavations with the Ashmolean Museum at Oxford and the Baghdad Museum since 1923. Field’s funds allowed him to invite Buxton to travel with him on the brief journey. Yesterday’s City | 47

During the first excavations at Kish, Field routinely arranged side trips and day journeys, searching for evidence of prehistoric man in the region. Field and Buxton were escorted by the British Royal Air Force (RAF), who maintained several landing grounds in the region of the survey. The team, which included several RAF officers, often recorded the location of their finds based on the names of these landing grounds, such as “Landing Ground K” or “Landing Ground H.” Stopping their armored vehicles periodically, the RAF would allow Field and Buxton to survey the desert ground for short periods of time, looking for pieces of flint worked by early man. Field noted that the process was rather unusual: “It still seemed strange to have been searching for prehistoric man in two Rolls-Royce armored cars mounted with machine guns.” Field dramatically described the first major discovery of the expedition: Suddenly Buxton shouted, “Come here, I’ve found one.” I ran over to him, and sure enough he had picked up the first flint flake chipped by ancient man Above: Stanley Field, Henry Field’s cousin, was president of the Field Museum, then chairman of the board, until 1964. Below: Field Museum employees inspect specimens, including crates filled with stuffed and mounted animals, acquired during a field expedition to Abyssinia (now Ethiopia).

48 | Chicago History | Fall 2006

L. H. Dudley Buxton, Henry Field’s primary mentor, greatly influenced his future field exhibition work. Here Buxton clears a skeleton during the Field Museum-Oxford University Kish expedition in 1925–26. Yesterday’s City | 49