25 minute read

Practitioners of Progress

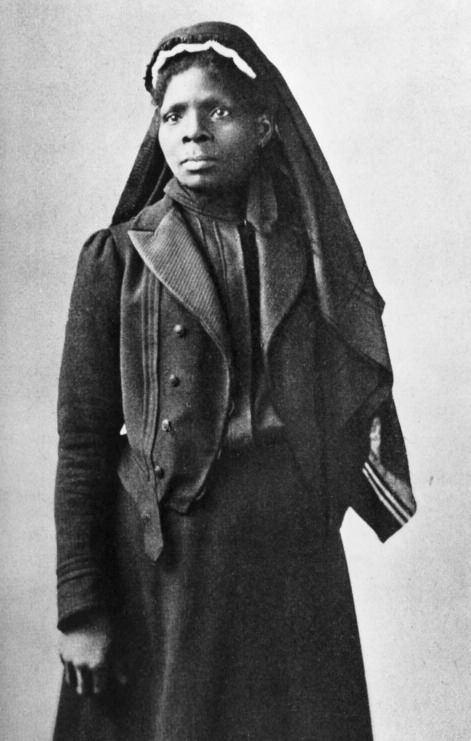

The only known photograph of Mary Seacole, likely taken for a carte de visite by Maull & Company, London, c. 1873.

The accomplishments of Black nurses, in defiance of the abject racism and sexism they faced, changed the course of the medical industry in Chicago.

Advertisement

Brittany Hutchinson

Introduction

In her 1857 autobiography, Wonderful Adventures of Mrs. Seacole in Many Lands, Mary Seacole recounts her experiences while applying to serve as a nurse with the British War Office during the Crimean War in 1854. Seacole, a Jamaican-Scottish woman, hoped to join the staff of nurses accompanying Florence Nightingale to Turkey but was met with rejection in each attempt. Having met the qualifications—training in both Western and West African medicine, a letter of support, and an eagerness to serve—Seacole wondered of the rejections: “Was it possible that American prejudices against color have some root here?”1 In stark contrast to Nightingale, who received support from the secretary of war and was assigned a fleet of nurses, Seacole funded her own travel to Crimea and began treating soldiers.

Seacole ’ s observation illustrates the prevalence of racism that also exists in the United States and particularly in medicine. 2 Within the context of who was allowed to formally function as a nurse, outside of the domestic sphere, white women alone were granted access. As early as 1775, nurses were included as part of pseudo-formal medical treatment teams when, at George Washington ’ s request, the Continental Army enlisted women to assist physicians in the care of twenty thousand soldiers. 3 The Red Cross “desegregated” their hiring policies in 1917 but resisted hiring and actually utilizing the services of Black nurses until December 1918, when eighteen Black nurses were elected to integrate Army bases at Camp Grant and Camp Sherman in Rockford, Illinois, and Chillicothe, Ohio, respectively. 4 The decision to integrate did not reflect an evolution of beliefs regarding race; rather, it was an act of forced attrition after the influenza pandemic created a drastic shortage of white nurses available for service with the Red Cross and Army Corps of Nurses.

The ways in which Black nurses, specifically in Chicago, navigated barriers set before them must be considered through the context of radical Black feminism and application of critical race theory. The specific purpose of using these two frameworks when discussing the role and history of Black nurses is to examine their nuanced experiences as they relate to race and gender in the United States. In navigating the obstacles generated by white supremacy and patriarchy, Black women were and still are required to consider their position as women and as Black people as an aggregated identity, as opposed to two separate focal points. In applying these frameworks to history, Black feminist thought centers the realities and experiences of race and gender, while critical race theory identifies and calls out the inherent racism in the external circumstances found in larger social environments. The significance, both cultural and historical, of the labor performed by Black nurses in Chicago is contextualized by examining the material and social conditions they had to negotiate.

This article seeks to establish the path created for and by Black women leading up to the pivotal role that Black nurses played in Chicago in 1918–19. This year is one of the most significant in American history, and centering the interpretation of this period through the work of Black nurses provides an important perspective that broadens our understanding.

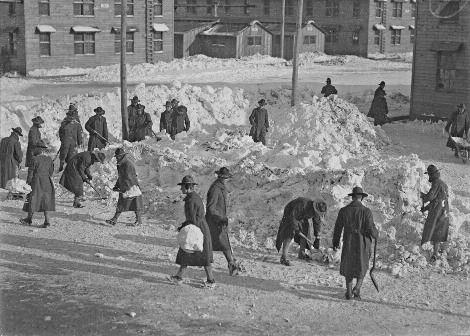

Soldiers at Camp Grant in Rockford, Illinois, shovel snow in 1918, the first year of the influenza pandemic that infected millions worldwide.

Black Women and the Medical Industry in the United States

The relationship between Black women and Western medicine is complex and nuanced in the ways in which violence infiltrates their interactions, both as patients and as practitioners. In regard to Black women as patients, specifically in the United States, this history is especially brutal. In addition to the nonconsensual collection of Henrietta Lacks ’ s cervical cancer cells, which were later used to establish the HeLa cell line, 5 one of the most infamous examples of the medical exploitation of Black women lies with the so-called “Father of Modern Gynecology, ” nineteenth-century physician J. Marion Sims.

Sims is credited with discovering a surgical treatment for vesico-vaginal fistulas, a complication which sometimes develops following traumatic birthing experiences. Sims ’ s innovation was long heralded without acknowledging or accounting for the fact that this feat was accomplished by conducting experimental surgeries on enslaved women, without their consent or the use of anesthesia. One “ subject, ” an enslaved woman named Anarcha, endured more than thirty of these surgeries. 6 Only three of the women who were subjected to years of torture in the name of medical science were ever identified by name in his writings. Sims became a wellrespected figure in the field of gynecology and was memorialized due to his discoveries. His cruel and dehumanizing experiments were documented and widely known within the medical industry, but the prevailing notion was that Black bodies and the pain inflicted upon them was of collateral value to Sims ’ s reputation and work. The result of those notions was the women ’ s stories being occluded from the historical record and public memory. It was not until 2018 that Sims ’ s actions were met with any consequence, albeit posthumously. A monument in New York honoring Sims was finally removed after years of protesting. 7 However, other monuments remain in states such as Alabama and South Carolina, and the legacy of Sims ’ s and others ’ dehumanizing treatment of Black bodies continues to live on in present-day medical practice.

In a 2015 study, it was discovered that nearly 50 percent of white medical students and residents believed that Black people had thicker skin and were therefore unable to feel as much pain as their white counterparts. 8 The same study concluded that this belief could be the cause of disparities in patterns of prescribing pain medicine to patients who sustained bone fractures. White patients were likely to receive higher and more frequent doses of pain medication than Black patients. Additionally, Black patients were less likely to be prescribed opioids to treat severe pain. 9 In care rendered specifically to women, recent studies have revealed that Black and Indigenous women are four times more likely to die due to complications associated with childbirth than white women. 10 This disparity is often attributed to racial bias in medical practitioners. Black patients report being treated coldly by medical staff or having their concerns ignored, like in the case of tennis champion Serena Williams, who experienced shortness of breath following the birth of her daughter and had to repeatedly insist to her doctor to check her lungs for blood clots. When they finally obliged, it was discovered that Williams did, in fact, have several blood clots in her lungs. 11

This uniform was worn by a student at Michael Reese Hospital’ s School of Nursing located on Chicago ’ s Near South Side, c. 1905.

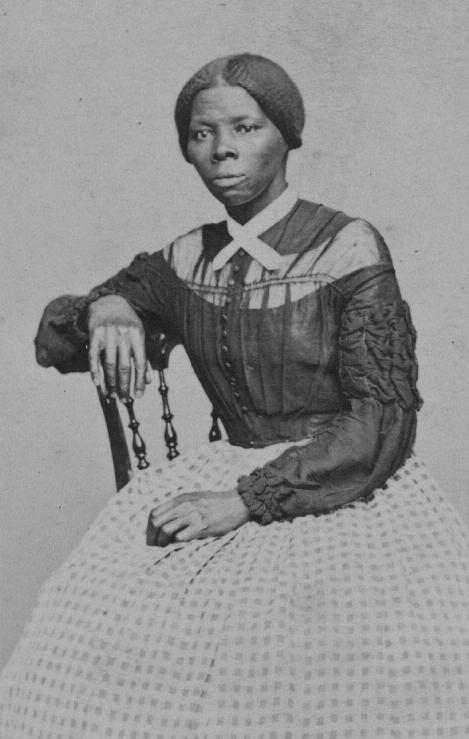

Harriet Tubman (left, c. 1868) and Susie Taylor (right, date unknown) contributed to Civil War efforts by serving as nurses to Black soldiers in the Union Army.

Black Women as Practitioners

The history of Black women as medical practitioners is as extensive and complicated as their experiences as patients. The history of inhumane medical practices carried out against African Americans may have been the impetus for Black Americans to enter the healthcare field, many of whom were Black women. A well-founded, and frequently reinforced, sense of distrust of white doctors spread throughout Black communities across the country. Black medical practitioners, of course, would not only serve as trusted professionals, but often would act as agents of societal shifts with regard to race relations.

African American women ’ s largest point of access to practicing medicine begins within the institution of slavery. The work associated with nursing was initially viewed as another form of labor that befell African American women. During the Civil War, women like Susie Taylor and Harriet Tubman famously worked as the first African American nurses to be employed by a government entity. Both women treated Black soldiers only and were severely underpaid compared to white nurses; Taylor received no compensation at all, and Tubman was denied military pension for her service. 12

By the end of the Civil War, Black women who felt compelled to enter the nursing industry found that any of their knowledge of medical practices and experience in performing the work associated with nursing was not enough, and formal apprenticeship opportunities were rarely made available to them. It was during this time that the responsibilities associated with nursing were starting to undergo the process of professionalization, which ultimately instilled and formalized in the medical profession racial and cultural biases, generating yet another bastion of white supremacy. 13 Formal training became the preferred access point for starting a nursing career, especially after 1873, when the Bellevue Hospital School of Nursing in New York became the first nursing program to be founded in the United States. These earlier years saw some, albeit limited, access to nursing programs for Black Americans.

Access to Nursing Programs

For many African Americans, access to higher education was difficult enough, but for women who were able and intended to receive formal training, the opportunity to enroll in a nursing program proved to be especially elusive. Among predominantly white institutions, nursing programs routinely denied admission to Black applicants solely based on their race or the covertly racist suspicions of their intellectual capacity or professional standards. 14 White hospitals in the South directly and explicitly banned Black women from entering their programs, while northern hospitals adhered to strict racial quotas to manage the number of Black students who were able to enroll. In 1879, Mary Eliza Mahoney of Boston became the first African American woman to complete formal training at the New England Hospital for Women and Children. Mahoney, born to formerly enslaved parents, worked at the hospital for more than a decade, as a cook, a janitor, and finally as an unofficial nurse ’ s assistant before being admitted to the program. At the time of her enrollment in 1878, she was one of forty-two students accepted for admission. The majority of the trainees dropped out of the notoriously challenging program, leaving only Mahoney and three other women to graduate. Despite meeting these high standards, Mahoney found it difficult to find work as a nurse in hospitals due to the racial discrimination she experienced and was resigned to work as a private nurse, mostly for wealthy white families. 15 With access to higher education being rigidly gatekept, the necessity for institutions dedicated to the educational advancement of Black Americans led to the establishment of nursing schools in areas like Chicago that had larger populations of Black residents. Most training programs for Black nurses were affiliated with Historically Black Colleges

A group of nurses in front of Provident Hospital and Training School, c. 1918. Originally located at Twenty-Ninth and Dearborn, this was the hospital’ s second location at Thirty-Sixth Street. Mary Mahoney, born in 1845, was the first African American woman to complete nursing training at the New England Hospital for Women and Children in Boston.

and Universities (HBCUs), beginning in 1886 Spelman College (formerly Spelman Seminary). 16 at

The majority of the nearly 2,800 nurses who graduated from these 36 schools prior to 1928 came largely from the 10 largest: Lincoln School for Nursing, New York City, (1898); Freedmen ’ s Hospital Training School, Washington, DC, (1894); Dixie Hampton Training School, Hampton, Virginia, (1891); Provident Hospital Training School, Chicago, Illinois, (1891); Hubbard Hospital Training School, Nashville, Tennessee, (1900); The Hospital and Training School of Charleston, South Carolina, (1897); Mercy Hospital, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, (1895); St. Agnes Hospital, Raleigh, North Carolina, (1896); Flint-Goodridge Hospital, New Orleans, (1896); and Tuskegee Institute, Tuskegee, Alabama, (1892). 17

Black owned and operated hospitals like Provident Hospital in Chicago and Mercy-Douglass Hospital in Philadelphia and HBCUs were revolutionary entities in the education of Black healthcare professionals and in the treatment of Black patients. Creating new pathways into the industry would prove invaluable for African Americans ’ survival in the United States.

The first convention of the National Association of Colored Graduate Nurses was held in Boston in 1909, one year after the association was founded.

Access to Professional Organizations

Professionalization of nationwide nursing standards and practices began at the 1893 World’ s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. It was during the world’ s fair that a consortium of nursing superintendents met to hold the first meeting of the American Society of Superintendents of Training Schools for Nurses (ASSTSN), which would later become the National League of Nurses (NLN). This governing body, in observing the constant fluctuation of standards among nursing programs, set its aims to increase admission requirements, advocating for better living and working conditions for students and increased access to professional development opportunities. The Nurses Associated Alumni of the United States, which would change its name to the American Nursing Association (ANA), was formed under the ASSTSN as a society dedicated to advancing the practice of nursing. 18 While neither the ANA nor the NLN held strict policies that directly barred Black nurses from joining, membership was extended only to those who had been accepted already into a state-level organization. In effect, the state organizations in the North that covertly practiced discrimination, and state organizations in the South that explicitly upheld “ whites only ” policies, were able to prevent many Black nurses from joining either the ANA or NLN. This system of racial exclusion continued until the NLN offered individual memberships in 1942, allowing Black nurses to circumvent discrimination against membership. 19 In a similar fashion to that of the Black women ’ s club movement in the fight for suffrage, Black nurses sought to develop leadership opportunities among themselves and established professional organizations dedicated to serving the needs of Black nurses caught in the crosshairs of white supremacy and patriarchy. In 1908, Martha Franklin, called the first meeting of the National Association of Colored Graduate Nurses with the intention to “ achieve higher professional standards, to break down discriminatory practices, and to develop leadership among Black nurses. ”20

Provident and the Rise of Black Nursing Programs

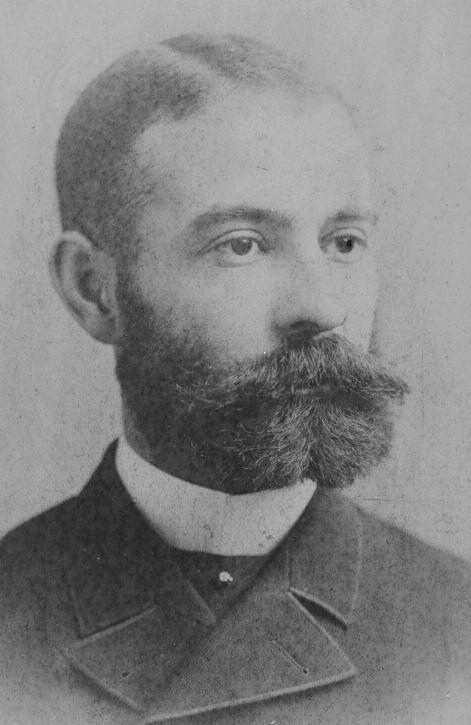

While seeking to transition from her career as a teacher in Chicago, Emma Reynolds expressed her frustration with the area hospitals refusing to admit her to their nursing programs due to her race. Her brother, Reverend Louis Reynolds, enlisted the help of his friend Dr. Daniel Hale Williams to use his connections to find a suitable program for her. 21 In 1889, Dr. Williams first met with other Black doctors to identify and convince a program in the city to admit Miss Reynolds. Dr. Williams and his colleagues came to fully conceptualize not only the barriers that Black women faced in seeking entry into the medical field, but also the limitations that plagued their own careers as Black medical practitioners within white hospitals. Despite being on staff at many of the area hospitals that they approached, Black doctors had very little influence within these organizations. Reynolds and Williams then determined that establishing a new nursing program for African Americans was the best course of action, as it would both create educational opportunities for Black women, but also attempt to shield them from hostile white supremacist learning environments. Provident Hospital and Training School for Nurses was founded in 1891 by Dr. Williams as the first Black owned and operated hospital in the United States. Two years later, Emma Reynolds and three other women became the program ’ s first graduating class.

Twenty-one years after Mahoney ’ s historic graduation in Boston, Jessie Sleet Scales became the first Black woman to break into public nursing. After graduating from Provident Hospital in 1895, Scales ’ s contemporaries urged her to abandon her aspirations of securing a public nursing position, citing the immovable nature of the very same unrepentant racial discrimination that derailed Mary Mahoney and every Black nurse ’ s career. Her persistence proved worthwhile as she was offered a job effectively integrating the New York agency of the Charity Organization Society (COS) in 1900. The first COS facilities opened in the United States in the late 1800s and provided social services, including medical intervention, to urban centers with high poverty rates. The COS, still operating as an agent of white supremacy and anti-Blackness, hired Scales

Emma Reynolds (left) graduated from Provident Hospital’ s Nursing School in 1893, two years after the hospital opened its doors with the help of Dr. Daniel Hale Williams (right).

Provident Hospital’ s graduating class of 1904, pictured in the 14th Annual Report of Provident Hospital and Training School, 1905.

on a conditional basis for two months. Within those two months, Scales was required to complete the unique prerequisite task of persuading African American New Yorkers to seek treatment for tuberculosis. The aforementioned distrust of the medical industry compounded with myriad other factors, many a result of various forms of racism, had resulted in high rates of untreated tuberculosis infections within African American communities in New York. Scales ’ s success resulted in the COS granting her full employment, which she maintained for nine years; perhaps more importantly, it proved that Black nurses were paramount in increasing access to dignified and trustworthy healthcare to Black Americans.

Nurses in 1918–19

The years 1918–19 brought about significant historical events in Chicago that created intersections of experiences in which the role of the Black nurse was integral. The spread of an especially aggressive strain of influenza first arrived in Chicago in spring 1918 but caused the most damage that fall. For African American communities in the city, the devastation of the virus combined with the material conditions of racism prompted a cultural and professional response from Black healthcare workers.

The African American population in Chicago experienced exponential growth in 1918 due to the first wave of the Great Migration. Black people from southern states moved north to escape the dangerous realities of racism, only to find that northern cities like Chicago participated in southern-born structural racism, but they also generated new systems of racial oppression that were uniquely northern. The city ’ s new residents found that segregationist notions regarding residential, professional, recreational, and educational spaces were aggressively enforced. The designated Black neighborhood, pejoratively referred to as the “Black Belt” and situated between Twelfth and Seventy-Ninth Streets and South Wentworth Avenue and South Cottage Grove Avenue,

Map of Chicago showing 1499 influenza deaths and 789 pneumonia deaths for the week ending October 26, 1918, from a report written by John Dill Robertson, Chicago ’ s Commissioner of Health.

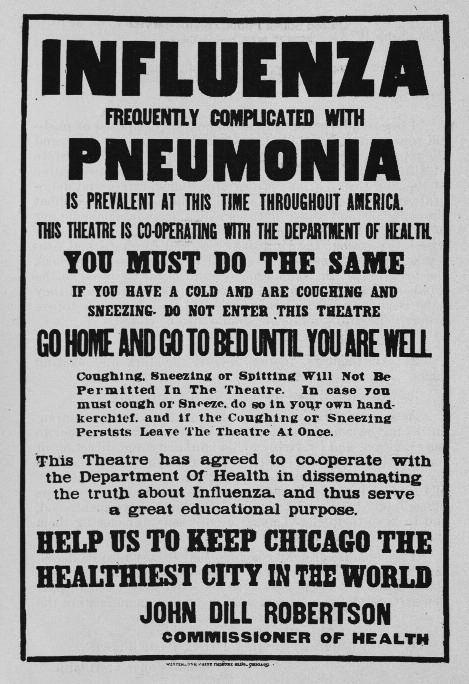

This announcement warning against symptoms of influenza was published as part of an educational series from the Department of Health in Chicago, fall 1918.

was home to the majority of the more than fifty thousand people who relocated between 1915 and 1920. 22 Residential spaces were often larger apartments that were divided into tiny “kitchenette ” units. Many of the buildings only had one bathroom per floor that all residents had to share. In addition to the conditions within the housing structures, the neighborhoods themselves did not receive adequate city services. The city ’ s reaction to the onset of the fall resurgence of the 1918 influenza was focused on white neighborhoods, and so city officials not only abandoned African Americans but blamed them for the consequences of racism that they were left to face.

The conditions present in African American communities were considered optimal for the spread of communicable diseases such as influenza, but it was discovered that African Americans did not become infected with the virus as frequently as other populations. However, in the instances of infection, Black Americans on average were less likely to receive adequate medical care. In an effort to address the inequity, the Chicago Defender hired A. Wilberforce Williams as the resident health expert. Williams, a prominent Chicago physician, began publishing his column “Talks on Preventative Measures, First Aid Remedies, Hygienics, and Sanitation ” in 1911, covering topics that at the time would have been considered taboo. Dr. Williams ’ s column cycled through a variety of topics until the fall of 1918 when his focus shifted to discussions about influenza. The first of his influenza columns provided general information regarding standard symptoms and methods to prevent illness. As the pandemic progressed, his writings about the shortage of doctors and nurses reflected the chaos within the community, as he warned readers of the damage and consequences of calling multiple doctors in a state of panic, thus further overwhelming healthcare workers. 23 Black nurses worked alongside physicians like Dr. Williams and community leaders to educate Black Chicagoans on how to best prevent becoming infected with influenza. Their efforts were not limited to medical advice, Black medical professionals lobbied city officials to increase sanitation efforts and infrastructure in Black neighborhoods, which often did not receive adequate access to city services.

At the time, social and medical beliefs had been shaped by doctrines which asserted that not only were African Americans at fault for the conditions in American ghettos, but their poor health and intemperance were “ race traits. ” Statistician Frederick L. Hoffman purported in his 1896 article, “Race Traits and Tendencies of the American Negro, ” that African Americans as a race were destined for “ extinction ” due to their worsening overall health, which he held was a biological fact rather than an effect of living conditions, and were prone to moral and behavioral inferiority. Hoffman ’ s writings also suggested that Black people were not fit for emancipation and were better suited to enslavement. 24 Hoffman ’ s article, which was written with the intent to argue for the uninsurability of Black people, impacted generations of medical and societal beliefs about Black Americans.

The summer of 1919, commonly referred to as the Red Summer, marked a wave of violence against Black people in several cities across the United States. The “Race Riot” in Chicago, which would more accurately be described as widespread acts of violence against Black Chicagoans at the hands of white Chicagoans and the police, spread across the city ’ s “Black Belt, ” leaving nearly forty people dead, several hundred injured, and more than one thousand without shelter—the most heavily affected being African Americans. The violence began with the murder of Eugene Williams after he unknowingly drifted across an invisible “ color line ” into the unofficially designated white-only side of the Twenty-Ninth Street beach. The week-long stretch of brutality against African Americans was more than a period of civil unrest. A staff of ten physicians, three interns, and fifteen nurses worked

Police escort African Americans with their belongings from Forty-Eighth Street and Wentworth Avenue, where race riots occurred, 1919.

tirelessly at Provident Hospital, located in the city ’ s “Black Belt. ” Only one other hospital, Fort Dearborn, reported treating a Black victim, while the vast majority of victims, more than one hundred patients and all of them Black, were treated at Provident. 25

Black medical professionals found themselves disproportionately overwhelmed and with little or no intervention from their white counterparts.

The first Black owned and operated hospital in the United States came to fruition in part because of Emma Reynolds ’ s determination to become a nurse, Jessie Sleet Scales ’ s tenacity to make her a pioneer in culturally competent healthcare, and Mary Eliza Mahoney ’ s diligence to break the barrier. The triumphs of Black nurses, in direct defiance of the abject racism and sexism that they faced, changed the course of history. The years 1918 to 1919 proved to be a pivotal point in American history as the suffrage movement, World War I, the 1918 influenza pandemic, and the Red Summer of 1919 converged and shook the country to its core. While the effects of the aforementioned events were felt across the United States, the direct experiences of Black nurses in Chicago are uniquely situated in the absolute center of this intersection in American history.

Brittany Hutchinson is an assistant curator specializing in cultural history at the Chicago History Museum.

ILLUSTRATIONS | Illustrations are from the collection of the Chicago History Museum unless otherwise noted. Page 18, Wikimedia Commons. 19, DN-0069735, Chicago Daily News collection. 20, ICHi-067588. 21, left: Collection of the National Museum of African American History and Culture shared with the Library of Congress; right: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USZ61-1863. 22, top right: Wikimedia Commons; bottom left, ICHi-040212. 23, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library. 24, left: The Provident Foundation; right, ICHi-021719. 25, ICHi030235. 26, ICHi-176187. 27, ICHi-176190. 28, ICHi-177143.

FURTHER READING | For more on the history of racism in medicine, see Deirdre Cooper Owens, Medical Bondage: Race, Gender, and the Origins of American Gynecology (University of Georgia Press, 2018); Harriet A. Washington, Medical Apartheid: The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans from Colonial Times to the Present (Anchor, 2008). For more on Henrietta Lacks, see Rebecca Skloot, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks (Crown, 2011). For work by Mary Seacole, see Wonderful Adventures of Mrs. Seacole in Many Lands, ed. Sara Salih (Penguin Classics, 2005).

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7. Mary Seacole, Wonderful Adventures of Mrs. Seacole in Many Lands, ed. W. J. S. (London: James Blackwood, Paternoster Row, 1857), 73. https://digital.library.upenn.edu/women/ seacole/adventures/adventures.html#VIII

Indigenous and enslaved Black women also performed these duties often within the scope of their own cultural medical knowledge and practice. Regardless of the source and application of their medical knowledge, Indigenous and Black cultural medical practitioners were explicitly discredited, and traditional practices were demonized through white supremacy often via Christianity. See Dennis W. Zotigh, “Native Perspectives on the 40th Anniversary of the American Indian Religious Freedom Act, ” Smithsonian Magazine, November 30, 2018. Accessed October 20, 2020. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/blogs/ national-museum-americanindian/2018/11/30/native-perspectivesamerican-indian-religious-freedom-act/; Albert J. Raboteau, Slave Religion: “The Invisible Institution ” in the Antebellum South (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004), 330–34.

“The History of Nursing in the United States, ” National Women ’ s History Museum. Accessed September 20, 2020. https://www.womenshistory.org/resources/ general/history-nursing-united-states

Marian Moser Jones and Matilda Saines, “The Eighteen of 1918–1919: Black Nurses and the Great Flu Pandemic in the United States, ” American Journal of Public Health 109, no. 6 (June 1, 2019): 877–84.

Rebecca Skloot, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks (New York: Crown Publishers, 2010).

Meagan Flynn, “Statue of ‘Father of Gynecology, ’ Who Experimented on Enslaved Women, Removed from Central Park, ” Washington Post, April 18, 2018. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/ morning-mix/wp/2018/04/18/statue-offather-of-gynecology-who-experimentedon-enslaved-women-removed-fromcentral-park/

Flynn, “Statue of ‘Father of Gynecology. ’” Kelly M. Hoffman, Sophie Trawalter, Jordan R. Axt, and M. Norman Oliver, “Racial Bias in Pain Assessment and Treatment Recommendations, and False Beliefs About Biological Differences Between Blacks and Whites, ” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (April 2016): 4296–301. https://www.pnas.org/ content/early/2016/03/30/1516047113.full

9. Joshua H. Tamayo-Sarver, Susan W. Hinze, Rita K. Cydulka, and David W. Baker, “Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Emergency Department Analgesic Prescription, ” American Journal of Public Health 93, no. 12 (December 2003): 2067–73. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ pmc/articles/PMC1448154/

10. Centers for Disease Control, “Racial and

Ethnic Disparities Continue in

Pregnancy-Related Deaths, ” September 6, 2019. Accessed September 15, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/ 2019/p0905-racial-ethnic-disparitiespregnancy-deaths.html

11. Maya Salam, “For Serena Williams,

Childbirth Was a Harrowing Ordeal.

She ’ s Not Alone, ” New York Times,

January 11, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/ 2018/01/11/sports/tennis/serenawilliams-baby-vogue.html

12. “Susie King Taylor, ” National Park

Service. https://www.nps.gov/people/ susie-king-taylor.htm; Sarah H. Bradford,

Harriet: The Moses of Her People (New York:

Geo. R. Lockwood & Son, 1886), 95. https://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/harriet/ harriet.html

13. Mark D. Davis, “We Were Treated Like

Machines: Professionalism and Anti-

Blackness in Social Work Agency

Culture, ” master ’ s thesis, Smith College,

Northampton MA, 27–37. https:// scholarworks.smith.edu/theses/1708

14. Darlene Clark Hine, “The Ethel Johns

Report: Black Women in the Nursing

Profession, 1925, ” Journal of Negro

History 67, no. 3 (1982): 212–28.

15. “Mary Eliza Mahoney Biography:

The First Black Nurse. ” https://www. jacksonvilleu.com/blog/nursing/ mary-eliza-mahoney/; Kelly Spring,

“Mary Mahoney, ” National Women ’ s

History Museum, 2017. https://www. womenshistory.org/educationresources/biographies/mary-mahoney 16. Nancy Hayward, “The History of

Nursing in the United States, ”

National Women ’ s History Museum. https://www.womenshistory.org/resource s/general/history-nursing-united-states

17. Anna B. Coles, “The Howard School of Nursing in Historical Perspective, ”

Journal of the National Medical Association 61, no. 2 (March 1969), 105. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/ articles/PMC2611690/pdf/jnma005160005.pdf

18. “History of the National League for

Nursing, 1893 2018, ” National League for Nursing. http://www.nln.org/docs/ default-source/default-documentlibrary/nln-timeline-june-2020.pdf?sfvrsn=2

19. “National League for Nursing Hosts

Inaugural Conference Celebrating

Leadership Role of Historically Black

Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) in

Nursing Education, ” National League for

Nursing, April 2, 2018. http://www.nln.org/ newsroom/news-releases/newsrelease/2018/04/03/action-coalitionto-increase-diversity-in-nursing-bystrengthening-hbcus

20. “Hall of Fame, ” American Nurses

Association. https://www.nursingworld.org/ ana/about-ana/history/hall-offame/inductees-listed-alphabetically/

21. “History - Provident Hospital, ”

The Provident Foundation. https:// provfound.org/index.php/history/ history-provident-hospital

22. Christopher Manning, “African

Americans, ” Encyclopedia of Chicago. http://www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory. org/pages/27.html

23. A. Wilberforce Williams, “Talks on

Preventative Measures, First Aid

Remedies, Hygienics, and Sanitation:

Spanish Influenza- Things We Must Do, ”

Chicago Defender, October 19, 1918, 16.

24. Frederick L. Hoffman, “Race Traits and Tendencies of the American Negro, ” Publications of the American Economic Association 11, no. 1–3 (1896): 1–329.

25. “Hospitals Have Busy Night with Victims of Riot: Provident Treats 100; Colored

Nurses Save White Chief, ” Chicago Daily

Tribune, July 29, 1919, 3.