29 minute read

Sylvia Pankhurst the East London Suffragettes and the Chicago Strikers

Chicago in January 1911 gave Sylvia Pankhurst an extraordinary insight into the condition of workers in America and informed new ways of organizing.

Advertisement

—Sheila Rowbotham, Hidden from History (1973) Katherine Connelly

In March 1916, the Australian writer Miles Franklin, most famous for her novel My Brilliant Career, sent a letter from war-weary London to her friend Alice Henry. In her letter, she recalled “traipsing around Chicago with you ” : the two women were deeply involved in the Chicago labor and feminist movements and had together edited the Chicago-based Women ’ s Trade Union League publication, Life and Labour. 1 Franklin, now on an extended stay in Britain, told Henry that she had recently sought out and written an article about the work of antiwar, socialist suffragette Sylvia Pankhurst in East London. 2 Franklin ’ s letter testifies to “half forgotten ” socialist feminist transatlantic friendships that helped inspire Pankhurst to radically change the nature of the British militant suffragette movement, with far-reaching political and personal consequences.

Franklin ’ s article on Sylvia Pankhurst detailed her visit to what she described as “the dark pit of London ’ s East End” ; the poverty in that part of the city had only been exacerbated by the war. 3 Pankhurst showed Franklin around the various projects initiated by the East London Federation of Suffragettes, now rechristened the Workers ’ Suffrage Federation. Franklin described Pankhurst’ s home, and headquarters of the organization, on East London ’ s Old Ford Road, as a “tumbledown house ” with an “impoverished meeting hall” at the back where a costprice restaurant, selling food on a not-for-profit or “ at cost” basis, allowed people to access cheap meals (which were surreptitiously made free to the very poorest). She saw what had been the Gunmakers ’ Arms pub, opposite a gun making factory, which Pankhurst transformed into the “Mothers ’ Arms, ” providing a nursery run according to Montessori principles, a home visiting center, free medical care and advice, and free milk and baby food.

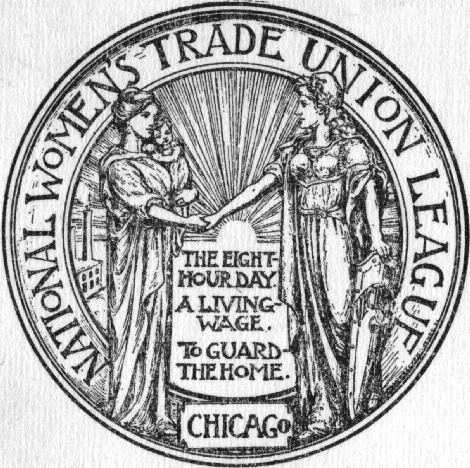

Estelle Sylvia Pankhurst was born May 5, 1882, photographed here c. 1911. Opposite: Seal of the National Women ’ s Trade Union League from a July 18, 1911, letter from the Chicago Women ' s Trade Union League to Agnes Nestor.

A group of children in London ’ s East End play with Jim, Sylvia Pankhurst’ s dog.

From the Mothers ’ Arms they walked to the toy factory that Pankhurst set up to provide decent employment to women who had been thrown out of work by the wartime restructure of industry. Pankhurst persuaded old friends she had met at art school to train the women. Franklin observed that the toys were “in great demand” and sold to such fashionable department stores as Marshall and Snelgrove, Liberty ’ s, and Gamages. 4

On top of all this, Franklin noted that Pankhurst also edited a weekly newspaper, The Woman ’ s Dreadnought.

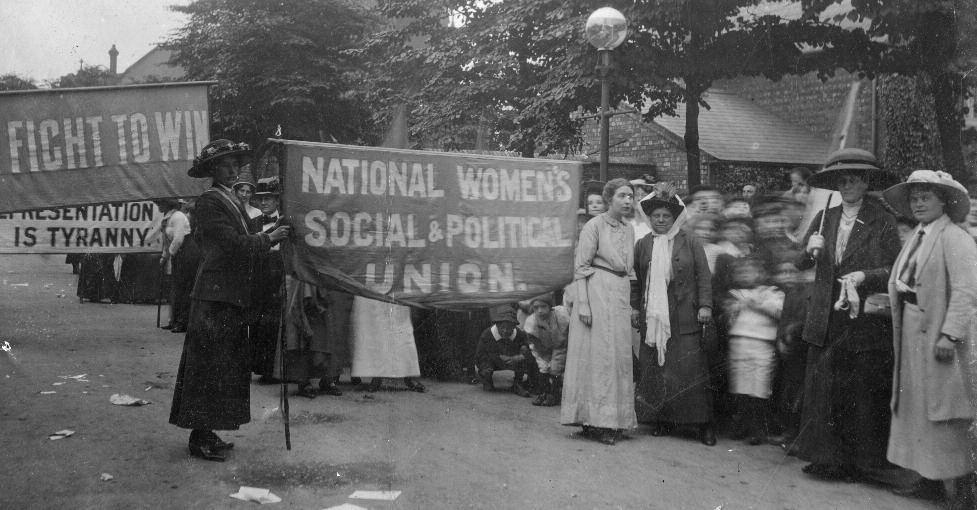

What Franklin observed in East London in 1916 was the result of a project started in 1912. In the autumn of that year, Sylvia Pankhurst tried to change the character of the Women ’ s Social and Political Union (WSPU), the foremost militant suffragette organization in Britain founded by her mother and sister, Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst, in 1903. Concerned with the increasing elitism of the leadership, which explicitly marginalized workingclass women and placed emphasis on individual acts of militancy, Sylvia Pankhurst went to East London to establish branches which would put working-class women at the center of a campaign for their political rights:

I wanted to rouse these women of the submerged mass to be, not merely the argument of more fortunate people, but to be fighters on their own account, despising mere platitudes and catch-cries, revolting against the hideous conditions about them, and demanding for themselves and their families a full share of the benefits of civilization and progress. 5 This decision inevitably created tension between Sylvia Pankhurst and her mother and sister. In January 1914, Sylvia Pankhurst and the East London branches were expelled from the WSPU by Christabel Pankhurst, who, Sylvia later recalled, informed her that “ a working women ’ s movement was of no value: working women were the weakest portion of the sex. ”6 Henceforward, the East London Federation of the Suffragettes (ELFS) operated as a separate organization. The difference between the two groups would be starkly revealed when the British government entered into the First World War in August 1914. The WSPU suspended the struggle for women ’ s political rights; it became vociferously jingoistic, proclaiming the preservation of the British state and its empire of primary importance. Although the ELFS continued to campaign for votes for women, the destitution in East London occasioned by the war ensured that the organization ’ s priority became the establishment of welfare schemes of the kind Franklin witnessed. The ELFS (later the Workers ’ Suffrage Federation, then the Workers ’ Socialist Federation) soon adopted an explicitly antiwar stance and was a precursor of the British Communist Party.

The developments of 1912, then, had far-reaching consequences for the women ’ s and socialist movements in Britain. Very little, however, has been written about why Pankhurst chose to act at that particular moment, what her organizational models might have been, or the fact that Pankhurst began the venture collaboratively.

Two separate suffrage organizations emerged in London due to their ideological differences, the National Women ’ s Social and Political Union (above), undated, and the East London Federation of Suffragettes (below), 1915.

Pankhurst would later recall that in the autumn of 1912, while trying to find a headquarters in East London, she “ set out with Zelie Emerson down the dingy Bow Road. ”7 Zelie Emerson became a leading figure in the East London campaign, and in early 1913 she and Pankhurst were imprisoned together, went on hunger strike, and endured the torture of forced feeding for weeks on end. Research into Zelie Emerson ’ s story, and Pankhurst’ s relationship with her, takes us on a journey back to the labor movement in Chicago, to Miles Franklin and a group of women who learned from and supported each other. That story was lost to historical accounts of the suffrage movement, and uncovering it provides fascinating insights into Pankhurst’ s actions from the autumn of 1912.

For three months at the beginning of 1911, Sylvia Pankhurst embarked on the first of two lecture tours of North America—the second followed a year later at the beginning of 1912. She had written The Suffragette: The History of the Women ’ s Militant Suffrage Movement, 1905–1910, a book which provided its author with the opportunity of telling the dramatic story of the campaign during the course of which she herself had twice been imprisoned. The book betrayed none of Pankhurst’ s disagreements with the WSPU leadership, which, prior to 1912, she had only expressed privately; she later reflected, “I would rather have died at the stake than say one word against the actions of those who were in the throes of the fight. ”8

Sylvia Pankhurst’ s tours of North America were extensive. In total, she spoke in nineteen different American states as well as Washington, DC, and toured parts of Canada. She spoke to state governments, university students, audiences of thousands in the largest venues in town, and small gatherings in private homes. 9 Her aim was to win support for the suffragettes, which meant justifying their use of militant tactics—something that was not yet a feature of campaigns in the United States. Pankhurst made her argument by rotating three lecture topics: the history of the women ’ s suffrage campaign; conditions for women in prison, of which she had personal experience; and conditions for women at work, which Pankhurst had extensively researched and intended to publish a book on. Surveying the history of the campaign allowed her to show that decades of peaceful campaigning had proved inadequate.

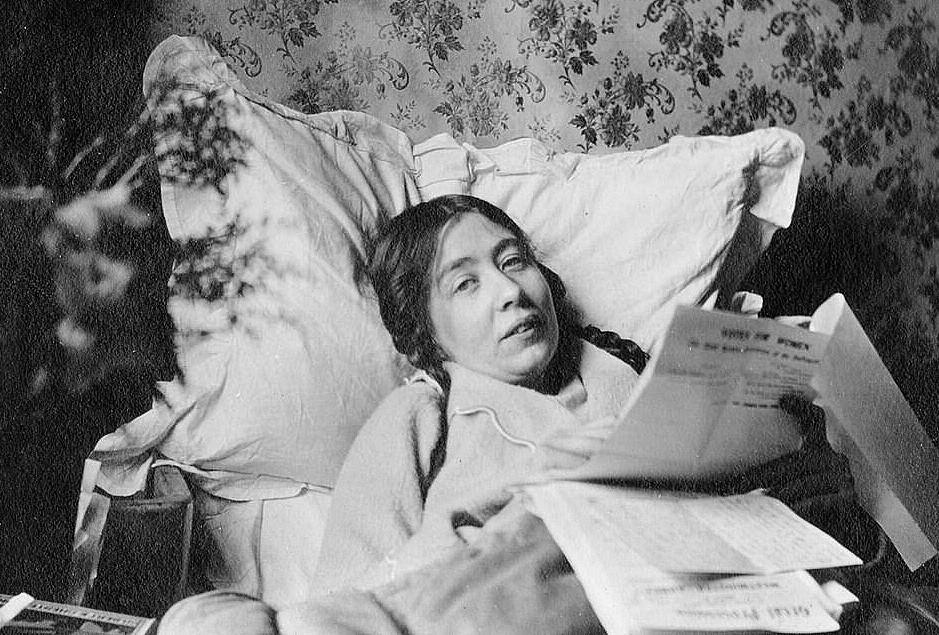

Some suffrage activists used tactics like attacking property, which led to prison sentences. While in prison, they used hunger strikes as another form of protest. Here, Pankhurst recovers from a hunger strike she went on while imprisoned in 1913.

While in Chicago in 1911, Pankhurst toured a jail where strikers had been incarcerated. From left to right: D. Curran, Tom Conroy, James Moriarty, Zelie Emerson, Olive Sullivan, Elizabeth Belmont, and Sylvia Pankhurst.

Discussing prisons enabled her to show the extent of government repression of the campaign. Finally, the experience of women workers proved that women ’ s inferior political status contributed to wider social problems, particularly in the form of poverty wages for women workers who were paid far less than their male counterparts. All this, Pankhurst charged, justified taking militant action to achieve political change. 10

However, to her great frustration, Pankhurst discovered that her audiences, frequently comprising suffragists from privileged backgrounds, while quite prepared to accept that terrible conditions might prevail for women in the “ old country, ” believed that these ills were not present in modern America. 11 Although Pankhurst had cautiously tried not to be seen as meddling in American politics, she was necessarily drawn into confronting an assumption that modern capitalism would cure social problems by itself and render women ’ s representation unnecessary. Pankhurst directly challenged this view, telling an audience “ composed of well-gowned women and intelligent men of standing ” in Oakland, California:

Here in America you always say the conditions are not so bad with you—but I want you to know that they are probably worse than you think. Your laws are not what they ought to be for the protection of women workers. 12

In support of her argument, Pankhurst sought to find out what life was like for the vast majority of Americans. Thus, on the third week of her 1911 tour, when she was in Chicago, the local press reported that “ on Miss E. Sylvia Pankhurst’ s tour through the American states, she will devote considerable time to the inspection of the condition of the American working classes as compared to those of Great Britain. ”13

Chicago in late January 1911 afforded Pankhurst an extraordinary insight into the condition of workers in America. A strike wave, which began in 1909 with “the uprising of the 20,000” mostly immigrant, Jewish women workers in the sweatshops of New York, spread to the clothing workers of Chicago in September 1910. When the Hart Schaffner & Marx clothing factory imposed a wage cut, workers there walked out on strike and inspired thousands of other garment workers to do the same. During one of their demonstrations, a striker held up a placard proclaiming “We are Striking for Human Treatments, ” which summed up their grievances. Paid poverty wages, which were now being further reduced, the largely female workforce complained that the foremen got bonuses if the workers produced over a certain amount, leading to greater exploitation and exhaustion. Those in a position of authority exercised a “ petty tyranny ” over their workers, supplemented with “ abusive and insulting language, ” and

a system of docking wages for such apparent misdemeanors as “liberal use of soap in washing hands. ”14

The Chicago strikers faced severe repression. Police beat and arrested picketing workers and shot two strikers dead. 15 Once arrested, the strikers were held in the notorious police court cells at Harrison Street. In addition, the Women ’ s Trade Union League (WTUL) explained that the employers themselves played a role in increasing the physical violence and intimidation:

The brutality of the police is not merely the brutality of some of the men on the force, but it is the brutality of the thugs, of the private detectives and the special agents hired by the employer. 16

On January 14, 1911, after nearly four months of industrial action that had been sustained through the bitterly cold winter, the United Garment Workers Union negotiated, without consulting the strikers themselves, for the employees at Hart Schaffner & Marx to return to work as arbitration had begun. When Pankhurst arrived into Chicago by train late at night on January 18, 1911, there were still around 30,000 workers from other firms on strike whose positions were now fatally undermined (and two weeks later the Union would call off the strike, leaving these workers without the safeguard of an agreement). 17

It was at this juncture that Pankhurst encountered the garment workers ’ struggle. On January 21, she went to Harrison Street to see the cells in which the strikers had been incarcerated. The visit had a profound effect upon her. A reporter from the Chicago Daily News recorded her immediate response:

“Wherever I have gone in America I have been assured that suffragettes would never receive the treatment here that they receive in England, ” said Miss Pankhurst, “but” —then a sigh— “I think there would be little difference if they incarcerate girls in these cells. ” 18

Later that day, Pankhurst fired off an article to the Chicago Tribune describing the “ exceedingly foul” air in the cells, the “fearful stench everywhere, ” the overcrowding, and the scant bedding that was never changed. In her conclusion she reiterated what she had told the reporter from the Chicago Daily News:

Whilst I have been in America I have constantly been told that had the suffragets [sic] been fighting for “ votes for women ” in this country, they never would have been subjected to the treatment which they have received in England, but some of the facts

I learned this morning have led me to feel that reformers all over the world have an almost equally hard fight before them. 19

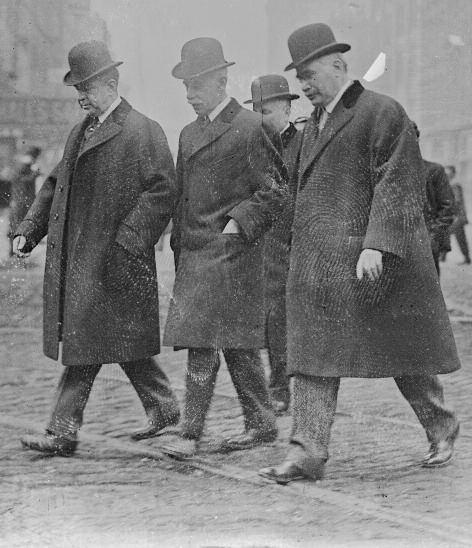

Above: Exterior view of Baskin store, at the Hart Schaffner & Marx building, 336 North Michigan Avenue, Chicago, c. 1929; Raymond W. Trowbridge, photographer. Below: Attorney Levy Mayer, Joseph Schaffner, and Harry Hart walk across a street in Chicago, 1910.

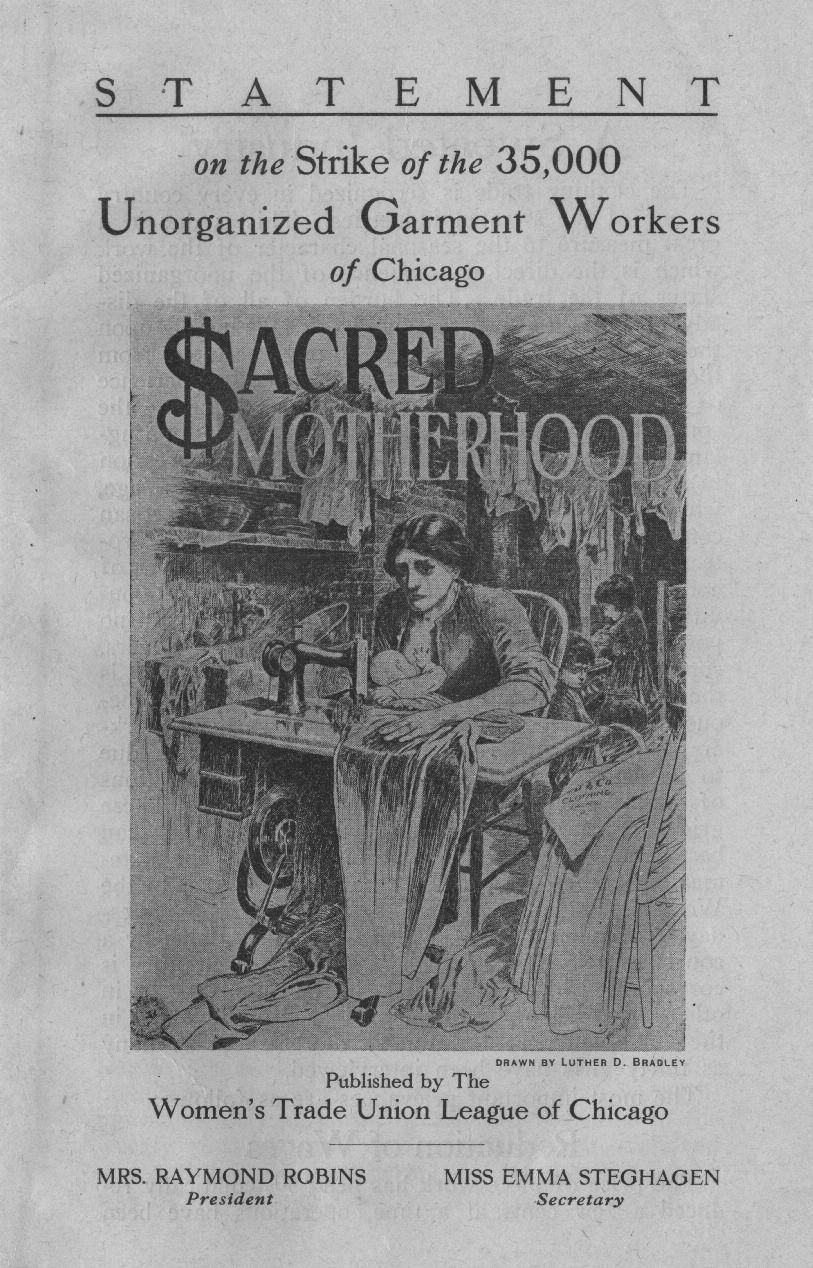

This pamphlet, titled “Statement on the Strike of the 35,000 Unorganized Garment Workers of Chicago, ” was published by the Women ' s Trade Union League of Chicago, c. 1910.

Women garment workers on strike in Chicago, c. 1911. One striker holds a sign that reads “We are striking for human treatments. ”

She recalled that this was where “ some of the women and girls who had been picketing in the garment worker ’ s [sic] strike ” had been locked up and that had it not been for union organizations paying bail money “they would have been obliged to continue suffering this terrible form of confinement. ”20 The way the striking garment workers were treated in Chicago proved that conditions in British prisons and factories were not exceptional, nor were they the quirks of an older, more conservative nation; rather, they were typical of modern capitalism.

Throughout the rest of her tour, Pankhurst drew on what she had seen at Harrison Street in Chicago to refute the idea that women in America received better treatment than in Britain. In Ottawa, she described Harrison Street as “the worst jail I have visited on this continent, ” while she frankly told a reporter in Detroit:

Another thing that annoys me terribly is to hear about the wonderfully good conditions existing in this country for women. Why, I never saw anything worse in London than the way the garment workers in Chicago suffered. 21

Speaking in Boston in February 1911, Pankhurst “ mentioned various unsatisfactory conditions which she had observed (in Chicago prisons, for instance), which called for women to take their share in the State

House-keeping. ”22 The poor conditions suffered by women workers in the garment factories and the repression they faced when they challenged them demonstrated to Pankhurst that women needed a voice in America just as much as women in Britain.

Harrison Street not only provided Pankhurst with a powerful argument for women ’ s suffrage in America, it was also the site of her first meeting with her future friend and collaborator Zelie Emerson. It was Emerson and a fellow member of the Chicago WTUL who took Pankhurst to Harrison Street and told her about the strike. 23

Zelie Passavant Emerson was born in 1883 into an extremely wealthy family in Jackson, Michigan. Her mother, Zelie Passavant, from a prestigious philanthropic family, was a friend of Andrew Carnegie—it was widely rumored that they had wanted to get married. Emerson ’ s father, Rufus Emerson, who had made a fortune from wood pulp, died when his daughter was just thirteen years old. Young Zelie Emerson, with an income reportedly of $10,000 a year, seemed destined to live a privileged life in “ society ” revolving around appearances in expensive clothes at lavish balls and social functions. 24 It was a life that Emerson judged “ aimless and rather silly. ”25

Instead, Emerson was concerned with social justice. Wanting to help working-class women, she felt she could not do so without herself experiencing their hardships. In July 1910, Emerson moved to Chicago where she lived in the Northwestern University Settlement House and took a series of working-class jobs: she worked behind a toy counter in a big Chicago department store during the Christmas shopping season, she became a “ scrubwoman ” cleaning floors in a restaurant, and she washed dishes in a hotel kitchen. 26 And then, two months after she moved to Chicago, the garment workers ’ strike broke out.

Emerson threw herself wholeheartedly into supporting the strike. It was a colossal task: there were around 45,000 workers on strike, many of them with families to support, including young children—there were 1,250 babies born to striking families. The WTUL judged that they supported more than 100,000 people in the strike. That support became even more crucial as the months wore on and strikers had to contend with the freezing winter. 27

If we examine what Emerson did in Chicago in 1910–11 and what Emerson and Pankhurst would do in East London from 1912, striking parallels emerge. During the strike, Emerson was the “Chairman ” of the Rent Committee, which supported strikers who could not afford to pay their rent. In effect, a rent strike was declared for the duration with the Rent Committee putting pressure on the landlords not to evict. In this they were remarkably successful—three months into the strike the Inter Ocean reported, “Miss Emerson said that only one case of eviction for non-payment of rent has come under her notice so far. ”28

Above: Undated photographic portrait of Zelie P . Emerson. Below: Pankhurst (left) and Emerson (right) during her visit to London in 1914.

A group of Chicago suffragists pose with signs that read “Votes for Women, ” c. 1910; John Becker, photographer.

After Pankhurst established the East London branches of the WSPU in 1912, these suffragette groups tried to organize a rent strike as a way of protesting for their political rights. A leaflet they issued, titled “No Vote! No Rent!, ” which sought to reassure women that they would not be penalized for taking action, drew directly on Emerson ’ s experience in Chicago:

A couple of years ago the garment workers of

Chicago, in America, were obliged to strike against rent, as well as against sweated employment, because they could not pay. . . . There was only one eviction in Chicago; there will be no evictions in

London when women begin the “No Rent” strike for the vote . . . 29

The Chicago experience allowed for the East London suffragettes to try to use the tactics of collective workingclass struggle to win political emancipation. The WSPU leadership was well aware that this tactic would alter the character of the movement, and it was used as a reason for separating the organizations. The minutes from the East London groups ’ first meeting after their expulsion from the WSPU recorded that although the WSPU had no objection to the “No Vote No Rent” strike, they “ said it was impossible to work it through their organisation because their people are widely scattered & because it is only in working class homes that the woman pays the rent. ”30 Although plans for the rent strike had to be abandoned at the outbreak of war as the ELFS’ s priorities changed, the relief schemes they now adopted—and which Miles Franklin observed in 1916—were likely also indebted to Emerson ’ s experience in the Chicago strike. In addition to her role on the Rent Committee, Emerson also worked on the huge relief efforts during the garment workers ’ strike. Shortly after the strike ended, Emerson coauthored a study with the radical economist Katharine Coman explaining that the creation of commissary stores, which bought wholesale to keep prices down, ensured “ nearly 32,000 people were at least kept from starving. ”31 A system was developed whereby strikers with families were provided with tickets that could be exchanged at the stores for a regular supply of food proportionate to their family size. Emerson herself was responsible for the WTUL restaurant run along

similar lines for single strikers at 1014 Noble Street, Emerson recalled that

the thoughtfulness of the strikers for one another was exhibited to a marked degree. When asked to take a second sandwich many would say, “I had breakfast this morning; give it someone who needs it more than I. ”33

For babies, who were unable to eat the food, a milk fund was established that ensured the daily distribution of 2,000 quarts of milk. 34

It should perhaps come as little surprise that when Pankhurst began to establish cost-price restaurants in East London operating like those in Chicago, based on food tickets, we find that Zelie Emerson was involved. In her war memoirs, Pankhurst recalled that though Emerson had left London in spring 1914 on account of her health, by autumn,

Zelie Emerson had scurried back to us from the

United States, eager to be in the thick of it. She was stirring me up to do something for our old Bow

Road district. Presently she was ladling out soup in

Tryphena Place, Bow Common Lane, an unsavoury neighbourhood, her black eyes frowning intent, and her red lips pursed—her little plump figure hurrying, scurrying. 35

Likewise, when Pankhurst established a milk center and clinic for babies, which had also been a feature of the Chicago relief scheme, “Zelie Emerson persuaded us to let her organise another in [East London ’ s] Bethnal Green. ”36

Zelie Emerson and her experience of labor organizing in Chicago had a huge impact on working-class women ’ s activism in East London. But what of Pankhurst’ s impact in Chicago and Emerson ’ s decision to make the journey to East London in the first place?

Pankhurst’ s public condemnation of the treatment of the striking garment workers at Harrison Street had been warmly received by the WTUL, which included her among the “English friends ” who deserved a “ special vote of thanks ” for her “ challenge to the social conscience, as well as an indictment of the industrial conditions of Chicago. ”37 Although Pankhurst was feted by the Chicago suffrage movement in 1911—she was the guest of honor at a luncheon provided by the Illinois Equal Suffrage Association and delivered a three-hour lecture in the Music Hall in the Fine Arts Building—it would be among the women labor organizers that Pankhurst found support in her more challenging tour a year later.

Militancy remained controversial in America. In January 1912, Catharine Waugh McCulloch, vice president of the Illinois Equal Suffrage Association, wrote furiously to a Wisconsin suffragist that association with Pankhurst could only discredit their struggle: I am not convinced that the English women who throw stones [and] go to jail help our cause. They did not reach the goal as fast as did the women in Cal[ifornia] and Wash[ington] and those women did not act like tomboys. 38

Tensions were further heightened when, on March 1, 1912, the WSPU coordinated a mass window smashing campaign in London ’ s fashionable West End, in response to the government’ s sabotage of a women ’ s suffrage bill. Emmeline Pankhurst was arrested and charged with conspiracy while, to escape capture, Christabel Pankhurst fled in disguise to Paris. Sylvia Pankhurst, still touring in America and desperately worried about her mother, found speaking engagements canceled and sympathy in short supply.

And yet it was at this moment that members of the WTUL in Chicago began to organize in Pankhurst’ s defense. Miles Franklin recalled:

When Sylvia Pankhurst had to abandon her lecturing tour when the news of a violent eruption of window smashing was cabled over, a few of us with the office of “Life and Labor ” and The Women ’ s Trade Union League as a starting point, tried to get up a “fair play ” meeting for her, but as with Sodom and Gomorrah, there were not enough of us to save the situation. 39

Chicago police put a woman into the back of a police wagon during the garment workers strike, 1910.

Chicago ’ s La Salle Hotel at the northwest corner of Madison Street and LaSalle Street, 1910; Charles R. Clark, photographer.

Although unable to arrange Pankhurst a meeting, Franklin and a WTUL colleague, Mary Anderson, joined the WSPU and thus sided with Pankhurst in the midst of the controversy, or, in Franklin ’ s words: “ recognizing a great hero before she gets into the monument form and becomes encrusted with the dust of ages. ”40 It was also around this time that Zelie Emerson began campaigning for women ’ s suffrage. In late March 1912, Emerson was listed as a speaker at a suffrage meeting in Chicago ’ s La Salle Hotel. 41 A few days later, Emerson was photographed by the press participating in quite a personal dispute over women ’ s suffrage. A Mr. William Murray, a store owner on Milwaukee Avenue, was in the process of tearing down a second large “ votes for women ” banner (he had previously taken down a smaller one), which had been erected by his wife while he was sleeping, when he was confronted by his wife, “ reinforced by Miss Zelie Emerson, the ‘ scrubwoman heiress. ’”42 The women won the argument and the banner stayed up.

In autumn 1912, Emerson was campaigning in Michigan ’ s ultimately unsuccessful referendum on women ’ s suffrage. She clearly had not forgotten Sylvia Pankhurst and the English suffragettes; at a meeting on September 21, 1912, she told a Michigan audience “ of conditions in England and why women were moved to act as they did in the cause of the vote. ”43 A few weeks after this, she was organizing a new kind of suffragette campaign with Sylvia Pankhurst in East London.

Pankhurst had kept her criticisms of the WSPU’ s elitism quiet for years, unsure how to turn criticism to positive effect. Through Zelie Emerson, Pankhurst found in the Chicago garment workers ’ strike new ways of organizing, which placed working-class women at the heart of the struggle for their own emancipation. This socialist feminist network from Chicago to East London, although now a “half forgotten memory, ” changed the course of history.

Dr. Katherine Connelly edited and introduced E. Sylvia Pankhurst, A Suffragette in America: Reflections on Prisoners, Pickets and Political Change (London: Pluto Press, 2019) and is the author of Sylvia Pankhurst: Suffragette, Socialist and Scourge of Empire (London: Pluto Press, 2013). She is a lecturer at the London centers of The College of Global Studies, Arcadia University, and Lawrence University and is the author of the blog “A Suffragette in America ” (asuffragetteinamerica.com).

ILLUSTRATIONS | Illustrations are from the collection of the Chicago History Museum unless otherwise noted. Page 4, ICHi-067680A. 5, Library of Congress, Miller NAWSA Suffrage Scrapbooks, 1897‒1911. 6, International Institute of Social History, IISG BG A32/665. 7, top: International Institute of Social History, IISG BG A32/450; bottom: International Institute of Social History, IISG BG A32/525-6. 8, International Institute of Social History, IISG BG A10/719. 9, DN-0056469, Chicago Daily News collection. 10, top: ICHi-082464; bottom: DN-0056060, Chicago Daily News collection. 11, ICHi066955. 12, ICHi-067059. 13, top: Library of Congress, George Grantham Bain Collection, item 2014687785; bottom, International Institute of Social History, IISG BG A10/732. 14, ICHi-177285. 15, DN-0056132, Chicago Daily News collection. 16, ICHi-071816.

FURTHER READING | For more on Sylvia Pankhurst, see Rachel Holmes, Sylvia Pankhurst: Natural Born Rebel (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2020) and Shirley Harrison and Richard Pankhurst, Sylvia Pankhurst: The Rebellious Suffragette (Sapere Books, 2018). On the suffrage movement in the UK, see E. Sylvia Pankhurst, The Suffragette: The History of the Women ' s Militant Suffrage Movement, 1905-1910 (Good Press, 2019). On labor strikes in the US, see Erik Loomis, A History of America in Ten Strikes (The New Press, 2020).

1.

2. “Letter from London: Miles Franklin to Alice Henry, ” in Miles Franklin, A Gregarious Culture: Topical Writings of Miles Franklin, collected and introduced by Jill Roe and Margaret Bettison (St Lucia, Qld.: University of Queensland Press, 2001), 63.

Although it remained a derogatory term in the US, the British militants proudly adopted the term “ suffragette, ” coined in 1906 by the Daily Mail newspaper.

3.

4.

5.

6. Miles Franklin, “The Babies ’ Kits: Miss Sylvia Pankhurst’ s Work, ” in Franklin, A Gregarious Culture, 70; for Pankhurst’ s firsthand account of the effect of the First World War on East London, see E. Sylvia Pankhurst, The Home Front: A Mirror to Life in England During the First World War (London: The Cresset Library, 1987).

Franklin, “The Babies ’ Kits, ” 73.

E. Sylvia Pankhurst, The Suffragette Movement: An Intimate Account of Persons and Ideals (London: Virago Limited, 1977), 417; on the WSPU leadership ’ s increasing elitism, see Katherine Connelly, Sylvia Pankhurst: Suffragette, Socialist and Scourge of Empire (London: Pluto Press, 2013), 27–30.

Pankhurst, Suffragette Movement, 517.

7. Ibid., 417. Some American newspaper reports (for example, Detroit Free Press, Feb. 15, 1913, 2) suggest that Emerson was in America over the autumn, not traveling to London until November. However, whether or not Emerson was present in the search for an East London headquarters that autumn, what is certain is that by the winter of 1912–13 she was deeply involved in the East London suffragette campaign.

8. Ibid., 316.

9. For the only detailed study of Sylvia Pankhurst’ s tours see Katherine Connelly, “Introduction ” to E. Sylvia Pankhurst, A Suffragette in America: Reflections on Prisoners, Pickets and Political Change (London: Pluto Press, 2019), 1–62.

10. Ibid., 29–33.

11. Ibid., 40.

12. Oakland Tribune, March 12, 1911, 33. 14. Women ’ s Trade Union League of

Chicago, Official Report of the Strike

Committee: Chicago Garment Workers ’

Strike, Oct 19–February 18, 1911 (Chicago: The League, 1911), 8.

15. Philip S. Foner, Women and the American

Labor Movement: From Colonial Times to the Eve of World War I (New York: Free

Press, 1979), 353.

16. WTUL, Official Report, 9.

17. Foner, Women, 353–54.

18. Chicago Daily News, January 21, 1911, 1.

19. Chicago Tribune, January 22, 1911, 7.

20. Ibid.

21. Ottawa Citizen, February 11, 1911, 1;

Detroit Free Press quoted in Woman ’ s

Journal, April 8, 1911, 107.

22. Votes for Women, April 21, 1911, 472.

23. Inter Ocean, January 22, 1911, 7; Chicago

Daily News, January 21, 1911, 1.

24. For one of many reports of Emerson ’ s family and wealth see Evening Sun,

February 3, 1912, 4. $10,000 in 1912 is roughly equivalent to $268,000 today (according to the CPI Inflation

Calculator at https://www.in2013dollars.com/).

25. Daily Arkansas Gazette, January 31, 1912, 11.

26. Ibid.

27. WTUL, Official Report, 3, 35. See

“Chicago at the Front: A Condensed

History of the Garment Workers ’ Strike, ”

Life and Labour, January 1911, 9; for an assessment of the importance of the

WTUL’ s role, see Colette A. Hyman,

“Labor Organizing and Female

Institution-Building: The Chicago

Women ’ s Trade Union League, 1904–24, ”

Women, Work and Protest: A Century of US

Women ’ s Labor History, ed. Ruth Milkman (Boston, MA, and London: Routledge &

Kegan Paul, 1985), 26–27.

28. Inter Ocean, December 12, 1910, 3; by the end of the strike, this figure was revised to four evictions, though Emerson judged that “two of these could have been prevented if the advice of the committee had been taken, ” Zelie P . Emerson and Katharine Coman, “Co-operative

Philanthropy: Administration of Relief During the Strike of the Chicago Garment Workers, ” The Survey, vol. 25, 1910–1911, March 4, 1911, 946.

29. “No Vote! No Rent!” leaflet [1913],

Estelle Sylvia Pankhurst Papers, 231,

International Institute of Social History,

Amsterdam (henceforward ESP Papers).

30. Minute book of the Council of the East

London Federation, January 27, 1914, 206, ESP Papers.

31. Emerson and Coman, “Co-operative

Philanthropy, ” 944.

32. Described by Emerson as “ a little Polish

Bakery ” (Emerson and Coman, “Cooperative Philanthropy, ” 945), it is now part of the Northwestern University

Settlement—the organization that

Emerson joined on arrival in Chicago!

33. Emerson and Coman, “Co-operative

Philanthropy, ” 945.

34. Ibid., 946.

35. Pankhurst, The Home Front: A Mirror to Life in England During the First World

War, 44.

36. Ibid.

37. WTUL, Official Report, 30.

38. Catharine W. McCulloch to Ada Lois

James, January 29, 1912, Ada Lois

James Papers, Wisconsin Historical

Society Library and Archives.

39. S.M.F. [Stella Miles Franklin],

“Mrs. Pankhurst in the United States, ”

Life and Labour, December 1913, 365.

40. Ibid.

41. The Inter Ocean, March 25, 1912, 3.

42. Chicago Tribune, April 4, 1912, 3.

43. News-Palladium, September 21, 1912, 7.