PAGE 4

JANUARY 15, 2025

SECOND WEEK

VOL. 137, ISSUE 7

PAGE 4

JANUARY 15, 2025

SECOND WEEK

VOL. 137, ISSUE 7

cers from the Chicago Police Department (CPD) informed the University that they intended to arrest a student at the Renee Granville-Grossman Residential Commons, following an investigation conducted by CPD. Officers from the University of Chicago Police Department (UCPD) were present at the residence hall when CPD officers made the arrest. The individual was charged with aggravated battery of a peace officer and resisting/obstructing a peace officer. The charges stem from the individual’s alleged actions during a protest on October 11 near 57th Street and Ellis Avenue.”

By ISAIAH GLICK | Senior News Reporter

Mamayan Jabateh, a fourth-year in the College, was arrested in December by the Chicago Police Department (CPD) in connection with the October 11 UChicago United for Palestine (UCUP) protest. According to a University spokesperson and CPD documents obtained by the Maroon, Jabateh, formerly identified by UCUP as “student B.,” has been charged with two felonies, including “aggravated battery of a peace officer.”

the University of Chicago Police Department (UCPD) reported that a “UCPD officer assisted CPD officers in the arrest of a wanted person” at Renee Granville-Grossman Residential Commons.

Jabateh, who uses they/them pronouns, allegedly struck a CPD officer’s face and body while they were attempting to prevent the detainment of a University undergraduate at the October 11 UCUP protest. The student was arrested and charged with felony battery, according to CPD documents obtained by the Maroon through a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request.

In an incident log dated December 11,

A University spokesperson confirmed Jabateh’s arrest, stating: “At approximately 5:00 pm on Tuesday, December 11, offi-

This information is corroborated by photographs captured by the Maroon

CONTINUED ON PG. 2

By DEREK HSU | Deputy News Editor

The Council on University Programming (COUP), which organizes Kuviasungnerk/Kangeiko (Kuvia), announced it will not host the annual winter tradition in 2025 following the arrest of a UChicago student in relation to the October 11 pro-Palestine protest.

NEWS: Heidi Heitkamp to Step Down as IOP Director

PAGE 2

In a January 8 statement posted on Instagram, COUP stated that “this decision was made in response to the arrest of a vital COUP member on our leadership team.” The student was

NEWS: UChicago Medicine Partners with Formula 1 Team

PAGE 5

“personally in charge of Kuvia 2025, serving as its primary planner, and their removal has created immediate and severe logistical challenges.”

The student, identified as Mamayan Jabateh in a UCUP press briefing, was arrested on December 11 on two felony charges, including “aggravated battery

GREY CITY: The Doctor Behind the Devastation: Philip Eil on UChicago Alum’s Path to Fatal Opioid Empire

PAGE 8

of a peace officer.” Jabateh served on the executive board of COUP prior to their removal from campus housing by the University. Jabateh is the second UChicago undergraduate who has been removed from on-campus housing and placed on indefinite academic suspen -

CONTINUED ON PG. 4

VIEWPOINTS: University Leaders and Their Plans: A Pathology

PAGE 10

with “aggravated battery of a

officer” and “causing an injury while resisting or obstructing a peace officer.”

CONTINUED FROM PG. 1

during the protest, which show Jabateh grabbing an officer’s hand and pushing an officer in the face.

CPD was unable to arrest Jabateh at the time because a protester intervened and pulled them away. They were released from the CPD detention facility at 7:24 a.m. on December 12, 14 hours after their arrest, according to CPD records.

At a January 8 press briefing, Jabateh appeared alongside members of UCUP, Southside Together, and the Fight Back UChicago Campaign to discuss the arrest and removal from University housing of themself and the still-unidentified “Student A.”

Jabateh said that four CPD officers approached and handcuffed them at Renee Granville-Grossman Residential Commons. According to Jabateh, no resident heads or resident deans were present at the arrest.

Jabateh also said they were in custody for 30 hours, from approximately 5 p.m. on Wednesday, December 11 until 11 p.m. on Thursday, December 12.

News outlets were not given an opportunity to pose questions to UCUP, Jabateh, or the other speakers at the briefing.

Prosecutors have charged Jabateh with “aggravated battery of a peace officer” and “causing an injury while resisting or obstructing a peace officer” under Illinois statutes 720 ILCS 5.0/12-3.05-D-4 and 720 ILCS 5.0/31-1-A-7, respectively. The student arrested during the October protest was only charged with “aggravated battery of a peace officer.”

The first charge is a Class 2 felony, punishable by three to seven years in prison, up to four years of probation, and/or

fines up to $25,000. The second charge is a Class 4 felony punishable by between one and three years in prison or up to thirty months of probation.

Per police documents, CPD identified Jabateh with assistance from a UCPD investigator, who observed the student on University cameras entering their residence hall. After the Cook County Circuit Court approved a subpoena request from CPD to UCPD, UCPD provided CPD with Jabateh’s photo identification, date of birth, current address, and name. The CPD officer Jabateh allegedly battered independently identified them based on their outfit in videos taken before and after the incident.

While in custody, Jabateh confirmed to investigators that they were the individual seen entering Renee Granville-Grossman Residential Commons in photographs taken after the October protest. They declined to speak further without their lawyer present, according to CPD documents.

The Maroon independently verified Jabateh’s identity and affiliation with the University by cross-referencing their CPD arrest log, photos captured by the Maroon at the protest, and documents obtained through FOIA requests, as well as details and photographs from Jabateh’s public social media profiles.

A December 16 post on UCUP’s Instagram announced Jabateh’s arrest on December 11 in relation to the October 11 protest, identifying them as “student B.”

“On Dec. 11, CPD and UChicago police (UCPD) showed up at student B.’s dorm. The cops arrested, interrogated, and detained them for 30 hours. They are pursuing serious charges,” the post reads.

“This arrest, months after the protest, is a deliberate, premeditated targeting of a Black student in a university building.”

A January 7 post from Fight Back UChicago, Writers Against War in Gaza, #CareNotCops, Students for Justice in Palestine at the University of Chicago, and UCUP shared additional information on Jabateh’s situation. “Over break, admin evicted them from their dorm and placed them on involuntary leave. They are the second student of color targeted in this exact way,” the post reads.

During the briefing, Jabateh also spoke about the arrest and removal from University housing of an unidentified Arab student, “A.” According to UCUP, “Student A.” was placed on an involuntary leave of absence and removed from on-campus housing, with no plans for reinstatement.

“That is what the University of Chicago does. When a student is arrested, as they claim, by the Chicago Police Department, without being proven guilty, their response is to strip them of their communities, their source of income, and their education, while simultaneously investigating to further prosecute that student,” Jabateh said.

According to a lawyer for “Student A.” who spoke to the Maroon in October, CPD arrested them during the October 11 protest. The Maroon was unable to confirm whether “Student A.” and the student arrested by CPD on October 11 and charged with felony battery are the same person.

While UCUP has posted publicly about the removal from University housing of “Student A.” on multiple occasions and held a rally on October 29 demanding that the University administration reverse the

student’s removal from University housing, the January 7 post was the first time that UCUP has stated that “Student A.” was arrested.

“Months ago, an Arab student going by Student A was also arrested and evicted for attending a pro-Palestine protest,” the January 7 post’s caption reads. “Months later, he is still waiting for his disciplinary proceedings.”

The University declined to comment on any ongoing student disciplinary matters, citing federal privacy laws.

During the October 11 protest, demonstrators locked Cobb Gate and vandalized University property before UCPD detained an unknown protester, sparking physical confrontations between police and protesters. Officers used pepper spray and batons on the crowd, while protesters physically engaged with police to prevent them from making arrests.

Since October, UCUP has not responded to repeated requests for comment made by the Maroon through email, social media, and by phone. The organization indicated that it would no longer provide press releases or comment to the Maroon unless an article covering the arrest of a student at the October 11 protest was taken down.

This is a developing story. Versions of this article appear on chicagomaroon.com under the headlines “CPD Arrests Second UChicago Undergraduate in Connection With October 11 Protest” and “UCUP Holds Briefing on Arrested and Evicted Students.”

Zachary Leiter, Sabrina Chang, and Nathaniel Rodwell-Simon contributed reporting.

By PETER MAHERAS | News Editor

The Institute of Politics (IOP) announced that Heidi Heitkamp will step down from her role as institute director later this year after more than two years in the role.

In an email sent on Thursday, January 9, founding Director David Axelrod said Heitkamp planned for her time as director to be limited when she accepted the role.

“During her tenure as director, Senator Heitkamp has been everything we had hoped for, and more,” Axelrod wrote in the email. “As passionate and personable as she is brilliant and experienced, Heidi has poured herself into her role and led the IOP to new heights.”

Heitkamp joined the IOP as director in January 2023. She served as a U.S. senator representing North Dakota from 2013 to 2019.

Heitkamp will leave the position following a “global search” to find her

“During her tenure as director, Senator Heitkamp has been everything we had hoped for, and more.”

CONTINUED FROM PG. 2

replacement, according to Axelrod’s email. After her departure, she will serve as a member of the IOP’s board of advisors, a role she held prior to her tenure as director.

Axelrod’s email highlighted Heitkamp’s work organizing a two-day conference on the rural-urban divide in the United States, which featured events

with elected officials, journalists, and nonprofit executives.

Heitkamp was also in charge of the IOP when pro-Palestine protesters briefly occupied the IOP building last May. Heitkamp, who was in the building at the time, had a 20-minute conversation with protesters before University of Chicago police officers escorted her out of the building.

Axelrod founded the IOP in 2013 after serving as a senior advisor and campaign strategist for then President Barack Obama. Axelrod announced in February 2022 that he would step down as director after nearly 10 years. In October 2022, the IOP announced that Heitkamp would serve as his replacement. Axelrod now serves as chair of the IOP’s board of advisors.

By EVGENIA ANASTASAKOS | Senior News Reporter

Demolition of the Accelerator (ACC) and High Energy Physics (HEP) buildings on East 56th Street and South Ellis Avenue began on September 9. The University is clearing the site to build a new engineering and science building, expected to be completed in 2028.

According to facilities services, the campus community can expect construction vehicle traffic and temporary lane closures on nearby roads in coming months. Main construction and foundation work is scheduled to begin this year.

Originally constructed for Enrico Fermi’s particle accelerator in 1949, the four-story ACC building has been home to large-scale physics and astrophysics research projects, a fossil lab and, for a brief time, an alligator on loan from the Herpetological Society of Chicago. For decades, the HEP building was a space for researchers to design and construct scientific equipment, before being repurposed as a location for the Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering’s undergraduate design courses, collaborative workshops, and seminars.

The new engineering and science building will house both the Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering and the Chicago Quantum Exchange (CQE), a research partnership with Argonne National Laboratory, Fermi National

Accelerator Laboratory, the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, and other institutions, aimed at fostering the development of quantum information science and technology in the Midwest. The facility will also include dedicated research space for the Biological Sciences Division. Renderings and diagrams of the facility published by the University show a total of 10 floors, containing offices, research labs, instructional labs, and seminar space.

The CQE project is receiving a total of $175 million in state grants for the construction of the CQE facility, according to a press release from the University.

“The new, world-class engineering and science building will serve as UChicago’s main center for engineering research and teaching,” a University spokesperson said to the Maroon. “It will extend UChicago’s capabilities to serve as a training ground for next-generation engineers and scientists.”

The building will be designed by HDR Architecture and Allison Grace Williams. Construction will be led by Mortenson Construction Company, which built Fermilab’s Integrated Engineering Research Center in 2023 and has previously partnered with the University to build both Campus North Residential Commons and the Harris

School of Public Policy’s Keller Center.

The University has not released information about the cost of the building. Programs in the ACC and HEP

buildings have been moved to the High Bay Research Building, on the corner of East 56th Street and Maryland Avenue.

Eva McCord & Kayla Rubenstein, Co-Editors-in-Chief

Anushree Vashist, Managing Editor

Zachary Leiter, Deputy Managing Editor

Allison Ho, Chief Production Officer

Kaelyn Hindshaw, Co-Chief Financial Officer

Arjun Mazumdar, Interim Co-Chief Financial Officer

The Maroon Editorial Board consists of the editors-in-chief and select staff of the Maroon

NEWS

Sabrina Chang, head editor

Peter Maheras, editor

Tiffany Li, editor

GREY CITY

Rachel Liu, editor

Elena Eisenstadt, editor

Evgenia Anastasakos, editor

Celeste Alcalay, editor

VIEWPOINTS

Sofia Cavallone, co-head editor

Cherie Fernandes, co-head editor

ARTS

Toby Chan, co-head editor

Lainey Gregory, co-head editor

Miki Mukawa, co-head editor

SPORTS

Josh Grossman, editor

Shrivas Raghavan, editor

DATA AND TECHNOLOGY

Nikhil Patel, lead developer

Austin Steinhart, lead developer

PODCASTS

Jake Zucker, head editor

CROSSWORDS

Henry Josephson, co-head editor

Pravan Chakravarthy, co-head editor

PHOTO AND VIDEO

Emma-Victoria Banos, co-head editor

Nathaniel Rodwell-Simon, co-head editor

DESIGN

Elena Jochum, design editor

Haebin Jung, design editor

Kaiden Wu, senior designer

Clementine Zei, associate designer

COPY

Coco Liu, copy chief

Maelyn McKay, copy chief

Natalie Earl, copy chief

Abigial Poag, copy chief

Ananya Sahai, copy chief

Mazie Witter, copy chief

SOCIAL MEDIA

Max Fang, manager

Jayda Hobson, manager

NEWSLETTER

Amy Ma, editor

BUSINESS

Jack Flintoft, co-director of operations

Crystal Li, co-director of operations

Ananya Sahai, director of marketing

Executive Slate: editor@chicagomaroon.com

For advertising inquiries, please contact ads@chicagomaroon.com

Circulation: 2,500 ©

CONTINUED FROM PG. 1

sion in connection with the October 11 pro-Palestine protest.

Kuvia is a long-standing UChicago tradition, typically taking place during the second week of winter quarter, in which streams of students walk to Henry Crown Field House in the early morning to perform sun salutation yoga poses and participate in various RSO-led activities. The weeklong festivities culminate in a walk to Promontory Point to perform salutations, and students who attend all five days are rewarded with a Kuvia-themed shirt.

Monday would have marked the 42nd celebration of Kuvia.

COUP’s decision reflects increasingly strained relations between campus activist groups and the University in recent years, as marked by multiple building occupations, a weeklong encampment on the quad, and continued protests.

The funds allocated toward Kuvia will remain in COUP’s RSO account to be saved for next year’s Kuvia, according to COUP co-president Pietro Juvara.

Juvara stated that COUP has no

plans for a future Kuvia event this year and does not anticipate asking for additional funding from the Program Coordinating Council (PCC), which is responsible for establishing budgets and providing support for performance groups on campus like COUP. However, COUP still plans to organize other events.

“COUP has no plans to cancel any other future events this year, and we can also confirm no money from the University, PCC, and/or student government has been spent or will be spent on behalf of COUP for anything other

than our events,” Juvara said. “If Snowball and Summer Breeze are executed as planned, we will request funding for those events from PCC at the end of the year in accordance with policy.”

In a statement to the Maroon , a University spokesperson wrote: “Kuvia has been a valued, student-run tradition since its inception in 1983. Campus and Student Life and the College offered support for Kuvia this year as they do for all student activities, and are prepared to do so this year if the student group chooses to proceed.”

By TIFFANY LI | News Editor

Daniel Kremer, a second-year student in the College and graduate of the University of Chicago Laboratory Schools, passed away on December 21, 2024. He was 21. The cause of Kremer’s death was not immediately available.

Daniel Kremer’s family held a memorial service for him on January 8 at Rockefeller Memorial Chapel, followed by a reception at the Newberger Hillel Center.

Dean of the College Melina Hale and Dean of Students in the College Philip Venticinque shared news of Kremer’s passing in an email on December 27.

In their email, Hale and Venticinque wrote that Kremer worked in UChicago chemistry professor Chuan He’s lab. According to a memorial website commemorating Kremer, he was “passionate about science” and planned to major in biochemistry.

He also was “an Effective Altruist and cared deeply about making the world a better place.” The website asks those who wish to honor Kremer’s memory to contribute to GiveWell, a charity evaluation organization, or one of GiveWell’s recommended charities. GiveWell describes its mission as searching for and directing funds towards charities that “save or improve lives the most per dollar.”

Kremer’s memorial website describes him as having “loved hiking

with friends and family, fencing, soccer, playing strategy games and traveling the world.”

Kremer was born on November 15, 2003 to Michael Kremer and Rachel Glennerster, who are both professors of economics at UChicago. Michael Kremer, jointly with Esther Duflo and Abhijit Banerjee, won the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2019 for their experimental approach to alleviating global poverty. Daniel Kremer was also the younger brother of Ben Kremer.

By DEREK HSU | Deputy News Editor

In a December 5 post on Truth Social, President-elect Donald Trump announced that UChicago alum David Sacks (J.D. ’98) will guide policy in artificial intelligence and cryptocurrency during his forthcoming administration. The newly created position of “White House A.I. & Crypto Czar” welcomes Sacks, who will bring a background as a former PayPal executive, general partner of an early-stage venture fund, and

Silicon Valley leader in conservative views. He also co hosts the podcast AllIn, which discusses current events and market conditions.

He will lead the President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology, which has provided science-based recommendations to U.S. presidents since it was established in 1933 during Franklin D. Roosevelt’s administration.

Sacks, who graduated from the UChi-

cago Law School, is a current member of the Polsky Council, which “provide[s] ongoing guidance and support to the Polsky Center [for Entrepreneurship and Innovation].” The Law School separately hosted Sacks for a fireside chat in 2014.

Acknowledging this newly created role, Sacks shared via X (formerly Twitter) that he “look[s] forward to advancing American competitiveness in [artificial intelligence and cryptocurrency].” As a “czar,” Sacks will bypass

Senate confirmation and immediately begin providing policy recommendations following Trump’s inauguration next January. While Sacks will not have direct authority over government agencies, he will be able to directly advise Trump on future decisions regarding cryptocurrency and AI. Along with Elon Musk, whom he previously collaborated with at PayPal, Sacks’s appointment may signal a burgeoning relationship between the White House and these industries.

By SABRINA CHANG | Head News Editor

At the Formula 1 Las Vegas Grand Prix in November, an unexpected sight zipped across the racetrack: the UChicago Medicine (UCM) logo, prominently displayed on the Haas Formula 1 (F1) car. This marked the beginning of UCM’s groundbreaking partnership with the MoneyGram Haas F1 Team, making it the first known sponsorship by a healthcare provider in Formula 1. The partnership, announced on November 21, seeks to expand UCM’s global reach and strengthen ties with international patients.

According to UCM’s press release, they will serve as an “Official Supporter of the MoneyGram Haas F1 Team” through the 2025 season before becoming an “Official Healthcare Partner” through 2027.

The partnership with Haas debuted at the Las Vegas Grand Prix, which took place from November 21 to November 23, in the 22nd round of the 2024 FIA Formula One World Championship. UCM’s branding appeared on the car’s livery and will be featured on the team’s gear starting in the 2025 season.

In an interview with the Maroon, UCM’s Vice President and Chief Marketing Officer Andrew Chang expressed a desire to capitalize on UChicago’s prominent brand. “A lot of our patients actually do come from all over the world, and so by helping our brand get out there in a more national and international presence, it really will help us get more patients and get more doctors around the world to get to know who we are and be able to collaborate with us more, whether it’s research or patient care,” he said. “We’re also trying to tap a more diverse, younger audience in the U.S.”

This marks UCM’s second sponsorship of a major sports team, building on their partnership with the WNBA’s Chicago Sky basketball team. While the collaboration with the Chicago Sky reaffirms UCM’s commitment to the Chicago area, Chang says that the F1 partnership aligns with their broader international strategy.

“There aren’t too many sports properties or sponsorship opportunities that are actually just global and not necessarily

centered around a physical location all the time. Formula 1 has that global presence with over a billion and a half fans and regular viewers,” Chang said.

F1’s 2024 and 2025 calendars feature 24 races each across five continents, including three races in the U.S. and four in the Middle East, which, according to Chang, is UCM’s largest market for international patients.

UCM’s entrance into a Formula 1 sponsorship also aligns with their emphasis on cutting-edge technology and innovation.

“The University of Chicago itself has been known for innovation through its research and breakthroughs. There aren’t too many sports that are also known for that,” Chang said. “Every sport, of course, is innovative in its own way, but from a truly science [and] data analytics sort of way, it’s motorsport.”

The Haas F1 Team is currently the only U.S.-based team, although that will change in 2026 with General Motors set to compete under the Cadillac brand. “[Haas] is not top three—they’re not necessarily a Mercedes or a Ferrari or a Red Bull, but they are the only team based in the U.S.…

and they also outpunch their media exposure,” he said. “So through a partner that’s truly global, we really found the perfect fit… to take our brand to the next level.”

The Haas F1 Team made its F1 debut in 2016, becoming the first all-American-led team in the sport in three decades. Haas placed seventh out of 10 teams in the 2024 constructor standings, improving from its last-place finish in 2023. Next season, they are welcoming a new driver lineup featuring seven-season veteran Esteban Ocon and rookie Oliver Bearman, the latter having gained recognition within the F1 community after stepping in as a reserve driver for two races in 2024. “We’re catching them on the up-and-up,” Chang said.

UCM is already working on plans for live activations at the Grand Prix races in Miami, Austin, and Las Vegas next season. They also aim to connect their faculty and researchers with Haas to explore further opportunities for collaboration and innovation.

“[Haas] has their own trainers and medical staff, of course, but we have literally the most innovative research and science that’s all behind it,” Chang said. “And so how do we give them that slight edge that makes the driver or the crew just that much better, and shave that 0.1 seconds off their time.… There’s so many possibilities of how we can collaborate.”

Chang also hopes to bring more attention to the partnership within the community around UChicago, potentially through events on campus featuring Haas team members or a car display, or by organizing an activation in the larger Chicago area.

For Chang, the ultimate success of the partnership will be measured by its influence on national and international patient volumes and global awareness of UCM.

“We’re trying to do things outside the box in a way that still makes sense from a business and community standpoint and that really catches the attention of our intended audiences,” Chang said. “Our country really needs change in healthcare, and [UCM] is trying to accomplish that, from the South Side to the country to the world.”

The century-old institution was long known as the heartbeat of Hyde Park. Today, it is its soul.

By VEDIKA BARADWAJ | Grey City Reporter

It’s 9 a.m. on a Sunday morning, and Valois stands tall on 53rd Street while Hyde Park sleeps in. The air is light and silent with the unhurried weightlessness of the weekend, and soft sunlight spills over the restaurant’s signboard—a didactic call to “See Your Food.”

There is something nostalgic, something quite “vintage Americana” about Valois’s diner-style interior: the thin, worn black sheaf chairs, the railings, the retro sugar shakers poised on each granite table. In many ways, Valois clings fervently to its past, from remnants of old menu

boards on the wall to the most significant (and mildly infuriating) relic of all: cash.

If the “cash-only” signs weren’t clear enough, the owners made the anticipatory decision to house an ATM in the corner of the restaurant. The restaurant goes out of its way to make sure that the transaction is as traditional as possible, even if the cost is dozens of negative restaurant reviews.

One angry diner on TripAdvisor wrote, “The 9% Inconvenient fees charged by the ATM I thought was exorbitant!”

As polarizing as the cash-only decision may be, Valois will never risk losing its steady stream of regulars, who pour in line with me this Sunday morning. A woman in front of me pushes her toddler in a stroller.

CONTINUED ON PG. 7

There’s a recently coined word for the feeling of nostalgia for a time you’ve never experienced—“anemoia.”

Behind me, an elderly man wearing a nasal cannula stoops forward with a cane.

“Can I speak to someone?” I ask the woman at the packing station. She looks behind, smiles, and says I came on the wrong day. I say I’ll wait anyway. I sit with a coffee in my hand—a dark roast. The child in the stroller smiles at me from across the room.

“Come back Wednesday morning,” the woman says, 40 minutes later. “I will make sure someone speaks to you.”

Valois. Valois never stops showing up for its diners.

Gianni Colamussi, manager-in-charge and partial owner, explains that Valois is where people living in the vicinity come for breakfast, lunch, and dinner.

“A lot of people live in places that don’t even have kitchens, and they depend on places like us where you can get a good, fresh meal at a reasonable cost. You can count on that every time you come here,” Colamussi said.

COVID changed that. We still have about 90 percent of the same menu.”

spent four years at Valois writing portraits of the Black men who convened at “Slim’s Table,” the designated meeting place of a group of Black men in Hyde Park, hosted by Slim, a local garage mechanic. Duneier describes how Valois has historically been the “stable hangout” for single men—often migrant workers from the South—living in empty homes without kitchens. He quotes Claude, a police officer, who confides: “Alone I can cook a good meal for myself, but I favor to be with people when I eat. These men are like my family now. Because we eat together every day.” CONTINUED FROM

Diners never stop showing up to

Valois is open 6 a.m. to 3 p.m. every single day, with the exception of Christmas: “We used to be open till 10 p.m., but

When the pandemic struck, the cafeteria kept its doors open to provide free meals to people in Hyde Park who depended on the cafeteria, even though the restaurant wasn’t open for business.

“The business definitely took a hit to the point that we were basically working for free—not the employees, but us, owners,” Colamussi explained.

Valois was one of the subjects of sociological study in Mitchell Duneier’s famous book Slim’s Table. Duneier, then pursuing his sociology Ph.D. at UChicago,

CONTINUED

...I realize that Valois being “stuck in time” is not an act of passivity or ignorance, but a result of active preservation.

CONTINUED FROM PG. 7

“See Your Food”

To “See Your Food” through the glass at the counter is to stare into a window to another time, to retrieve a core memory buried within you. Perhaps a time when you watched your mother cook something from scratch. You see the old utensils. You see the overstuffed oven. You see the worn hands that feed you. To quote Earl from Slim’s Table, “Comments such as ‘Mamma cooked from basics’ and ‘Mamma never used packaged stuff’ are typical of a generation of black men who feel very much at home in a cafeteria that offers its patrons a kind of food that is symbolic of the integrity of their older way of life.”

All the ingredients at Valois are locally sourced and delivered fresh every day, Colamussi says. You watch it being unpacked in front of you.

“You’re eating a real meal as if you were in a relative’s house for breakfast,” he adds.

A woman pats Colamussi on the back. He turns around, beaming. “Hello! I’m in the middle of an interview at the moment, do you have a few minutes?”

Her face shudders, thinking he is interviewing for a new job. “You’re going away?”

He reassures her. “No, no, no, not that kind of interview. An interview for a newspaper.”

The spirit of family, it seems, radiates

not just from the tables or the food, but from those who own the restaurant as well.

Valois was initially established in 1921 by French-Canadian William Valois. After switching between different locations and owners, the Hyde Park cafeteria has been under the current Greek family’s ownership for the past 50 years. The impressionist murals on the restaurant’s walls, painted by Sotirios Gardiakos (known professionally as Garsot), tell the story of the owners’ intertwined history with Chicago. The left wall is covered in motifs of the city, from the Chicago Field Museum to Grant Park. The right wall depicts Hyde Park symbols: the “Nuclear Energy” statue, Washington Park, Hyde Park Bank.

Colamussi points up to the ceiling. “The ceiling up here tells us the story of how [the owners] began. Right here is the village which they come from in Greece. And then they show you on this side, they came over the mountains, through the city of Chicago, and where they reside in Hyde Park. So it’s kind of the flow of their travel. Mountains. Settle in Chicago. Then into Hyde Park.”

Where times, geographies, and personal histories converge in Hyde Park

There’s a recently coined word for the feeling of nostalgia for a time you’ve nev-

er experienced—“anemoia.” You smell it when you open your grandmother’s musty wardrobe; you feel it when you visit a museum. I felt it in Valois, suddenly seized by a distinct longing for an “Old Chicago” from the ’60s or ’70s. One that I’ve never experienced, but one that I see trapped in all the newspaper cutouts framed on the restaurant’s walls.

Barack Obama. Anthony Bourdain. Quinton Aaron. American Idol contestants. The Chicago Bulls, among other name-dropped diners, have been here at Valois over the years. Colamussi recalls that when Obama took his final interview as president at Valois with Lester Holt of NBC, the restaurant was swarmed with White House staff, the FBI, and Secret Service personnel.

Colamussi adds, “You have students coming in from Florida or California or anywhere to a transient on the streets to construction worker[s] to politician[s]. It didn’t matter. The place was small. The place was packed. You could be a student from India sitting with the mayor because that’s the only spot available.” By the mid20th century—an era when South Side Chicago was known for its urban segregation—Hyde Park stood as an integrated microcosm, with these social contrasts central to its identity.

People came from every corner, every walk. The notable scholar. The worker with greasy hands. The woman who said

“amen” before each meal. The woman who didn’t. All of them sitting at one table—a neutral point, an equilibrium. Valois wasn’t world peace, but it was a place where, for a moment, the world could sit down and just talk.

I take the last bite of my omelet—the No. 5 Mediterranean—which has somehow stayed hot until the very end. I notice how the initial cacophony—sliding trays, of tinkling glasses, of babbling conversations—slowly transforms into a singular, synchronized heartbeat. The long queue spooled at the counter neatly unravels. All of a sudden, there is organization in the chaos; there is poetry in the hashbrowns turning, harmony in the cook screaming “pancakes,” artistry in the cashier handing you exact change without a moment of thought. The magic of a perfectly oiled machine.

I order a strawberry French toast to-go for my roommate. Feeling the weathered, foreign cash in my pocket, I realize that Valois being “stuck in time” is not an act of passivity or ignorance, but a result of active preservation. The woman at the packing station, placing strawberry jam into the bag, says, “I didn’t forget you this time.”

She doesn’t know she will see me again in a few weeks. And a few weeks after that. And again, until I earn the badge of “regular at Valois.” And then she won’t forget me, ever.

Author Philip Eil’s gripping true crime investigation traces the shocking transformation of a once-promising doctor into a figure whose opioid prescriptions led to deadly ends, earning him four consecutive life terms.

By LEAH TABAKH and NICOLE OCHOA | Grey City Reporters

Paul Volkman, a 1974 Pritzker School of Medicine graduate, once said

that his purpose as a doctor was to “relieve pain.” How then, did Volkman’s

attempt at “pain relief” for his patients lead to a life in prison, serving four consecutive life terms for four convictions of unlawful distribution of a controlled substance? How did this bespectacled,

socially awkward medical school student pulling all-nighters in Harper transform into the “Pill Mill Killer,” a man whose actions devastated lives and

CONTINUED FROM PG. 8

communities?

Author Philip Eil explores these questions in a thrilling, fast-paced true crime novel, Prescriptions for Pain: How a Once-Promising Doctor Became the ‘Pill Mill Killer.’ Eil’s motivation for investigating Volkman’s case stemmed from a personal connection: his father had been Volkman’s classmate at the Pritzker School of Medicine, both graduating in 1974.

“These crimes were so serious, and it was so at odds with who I knew my dad to be and who I knew the people in his circle [to be],” Eil explained in an interview with the Maroon. “I wanted to know what happened. How does a guy with this background, with this pedigree, wind up in such a disturbing situation?”

Eil also cited the difference between Volkman’s future career and those of his classmates as one of the reasons why he was interested in Volkman’s case. “These were people who were in a very prestigious program, a very selective program, and who, by and large, went on to do pretty remarkable things. They went on to teaching positions at renowned universities. They produced research. Some of them won awards. And so I really wanted readers to get a sense of just how far off of that path Volkman had veered,” he said.

Eil’s approach to writing Prescription for Pain underscores his commitment to honoring Volkman’s victims. Eil felt it was necessary to reach out to the many Volkman had harmed to get their side of the story. Volkman destroyed lives and communities, and those affected still feel the devastating consequences of his greed. He overprescribed opioids to bring in consistent cash flow. This led to many deaths due to overdose and the destruction of communities from opioid addiction. The pain embedded in this harm conjured up some difficulty in Eil’s research, pushing him to act cautiously and with empathy. “I knew that I was a stranger, appearing out of the blue, usually via social media, asking people about some

of the most sensitive, painful moments of their lives,” he said. “I was as transparent as possible, explaining who I was and what I was up to and why I was interested in this story.”

The book also highlights the broader corruption in the medical field. “I do think this is a story about corruption. You know, we often think of corruption in terms of politicians or maybe law enforcement, but corruption can happen in the medical sphere as well, and there’s money to be made there,” Eil noted. “There’s a lot of power to be wielded there, and the stakes are really high when that kind of corruption appears.” Volkman’s crimes raise concerns about the medical system. Even after many malpractice cases, Volkman was still allowed to practice. He was also given full permission to prescribe opioids as he chose. Through discussing the corruption within the medical field, Eil shines a light on the systematic problems that created the conditions for Volkman’s crimes.

Responses to Eil’s requests for interviews were mixed. Some people declined to speak, unwilling to reopen old wounds. Others, however, found solace in sharing their loved ones’ stories. “It was nice to encounter someone who cared about their life and wanted to learn about them,” Eil shared.

One of the book’s most compelling aspects is its deep dive into Volkman’s psyche, a voice riddled with contradictions. While Volkman has consistently painted himself as a compassionate, law-abiding doctor, Eil’s meticulous fact-checking reveals a starkly different reality. “Volkman was incredibly unreliable, sometimes even dishonest,” Eil explained. “I often describe the book as one long exercise in fact-checking him.” Volkman’s narrative often clashed with the accounts of victims, colleagues, and legal authorities, forcing Eil to parse truth from fabrication. Eil ultimately ended communication with Volkman after refusing to assist him with legal research for an appeal.

Eil’s work stands out in the true crime genre for its empathetic treat-

ment of victims. The book concludes with a poignant “In Memoriam” section honoring those who lost their lives due to Volkman’s actions. “I didn’t want to sensationalize this story or reduce the victims to mere statistics,” Eil said. “I wanted to portray them as full human beings and position the events in their broader historical context.”

Prescription for Pain masterfully examines the systemic failures that enabled Volkman’s crimes. If a successful Pritzker School of Medicine graduate can become the “Pill Mill Killer,” couldn’t anyone?

Abigail Poag contributed reporting.

The University has a history of wildly optimistic budget projections. Who is the audience, who is served, and what are the harms of this practice?

By CLIFFORD ANDO

Over the last year, in response to national press reports on the University’s debt load and structural deficit, the University of Chicago’s leaders have held a sequence of “budget town halls.” In these, it has described the deficit in gross terms—it was $239 million in FY23, $288 million in FY24, and they project it to run back down to $221 million in FY25. They have never discussed the causes of the deficit beyond a very general admis -

sion that expenses grew faster than revenue. There has been no itemization of the capital investments that were funded by borrowing, no account of the distribution across units of endowment payouts from unrestricted funds, no study of the tradeoffs the University has made in order to direct billions in capital expenditures and vast additional operating expenses to the small number of areas selected for new and renewed investment, and no public discussion of the effects of spending choices on disfavored

units. In consequence, there has been no study of our success along the different axes of endeavor that comprise the mission of a modern research university. Finally, there has been no consideration of the model of leadership under which the University has undertaken this project of transformation that I would characterize as entailing significant self-harm.

Given the extraordinary complexity of the modern university, I should spell out exactly what I mean in this context by

“project of transformation.” In its 2009 strategic plan, the University of Chicago committed to investing substantial new funds in two areas of scientific inquiry (molecular engineering and astrophysics); to deepen the interpenetration between the University’s endeavors and those of Argonne National Laboratory, which the University manages for the Department of Energy; and to continue a program of expansion in the size of the undergraduate College. (The 2009 plan had many parts; these are

the most salient in this context.)

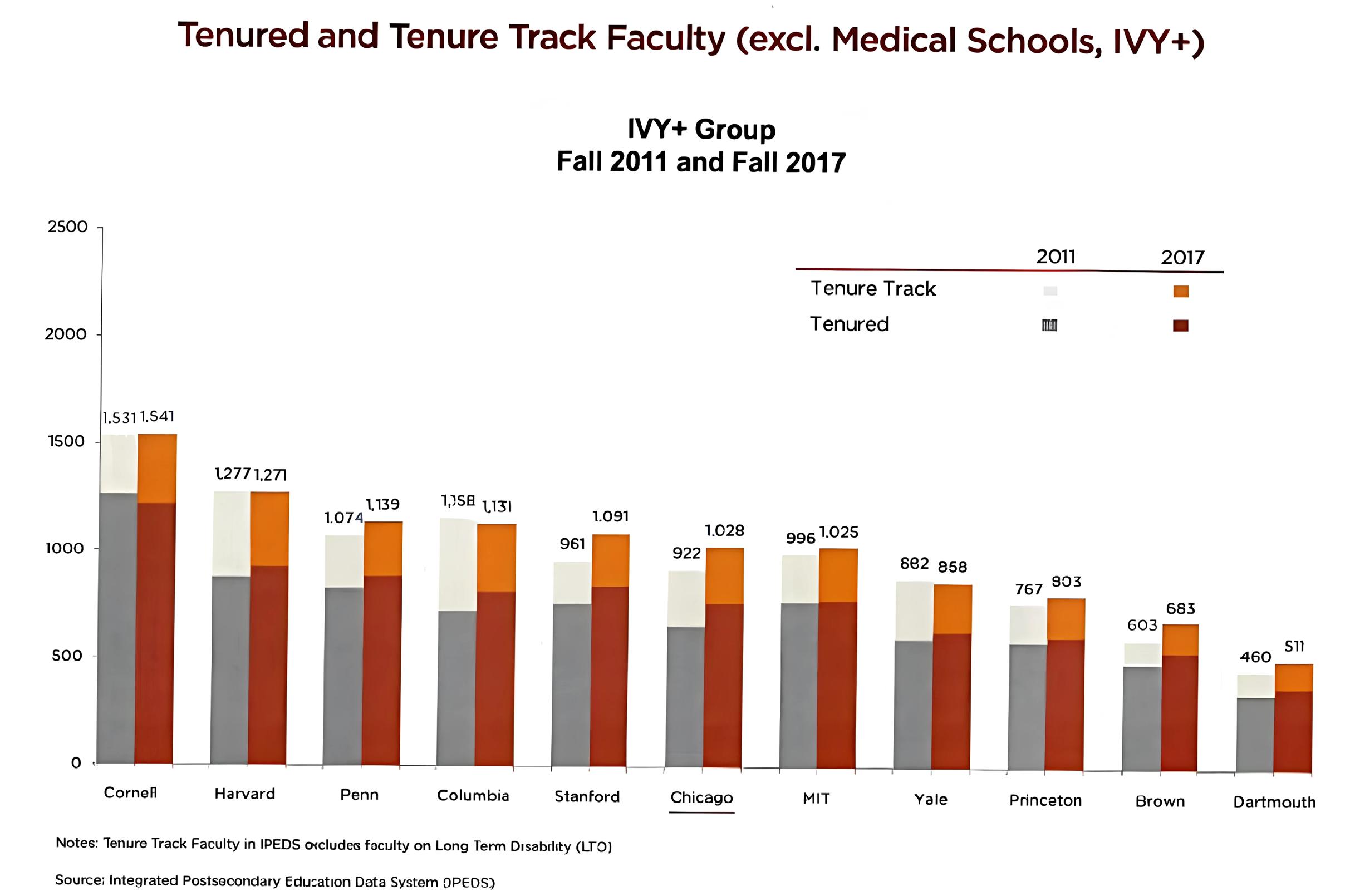

These programmatic changes in scientific endeavor had entailments that later urged further investment in related areas, especially computer science. Since then, new areas of inquiry have risen to importance that also call for major new spending, quantum computing and climate science foremost among these. These changes were bold and intellectually unassailable as such. (One could, of course, contest on policy grounds, but that’s not an issue for this essay.) Unfortunately, they were not pursued with discipline. Spending spiraled out of control; the University’s debt grew and grew; and the University effectively abandoned an earlier ideal of itself as a graduate university in which undergraduates were taught by researchers in favor of a less aspirational, less expensive practice. In short, in an effort to drive down the amount it spends on classroom instruction, the University has cut and cut and cut the size of its doctoral programs; has allowed the faculty-to-student ratio over and over to deteriorate; and has met the increased demand for instruction of the contemporary College by hiring instructional rather than research faculty. In short, we exist today in a fundamentally different university than 20 years ago not simply because we do more things, but also because we are abandoning ideals of research and models of pedagogy that we long held dear. The University’s 2009 strategic

CONTINUED FROM PG. 10

plan regarded a then-recent decrease in its faculty-student ratio as a problem along two fronts, one related to the character of the institution and one related to faculty recruitment. On the one hand, the change “threatened our core ethos as a University that places a premium on rigorous inquiry.” On the other, “the shift in student to faculty ratio has reached a point where an important comparative advantage for us in recruiting faculty has been diminished.” Values and self-interest converged to urge an increase in the size of the faculty. And yet, since 2011, the University’s leadership has constrained the hiring of research faculty in such a way that the University’s faculty-student ratio has become worse and worse. It was 5.83 in 2011, 6.13 in 2017, and 6.71 in 2023. (I draw the student numbers from the censuses of the University Registrar, historical faculty numbers from The University of Chicago. Data Trends —a booklet prepared for the meeting of the Board of Trustees in 2019 (figure 4)—, and current faculty numbers from data.uchicago.edu.) How are we to explain the University’s stunning divergence since 2011 from the official statement of its core ethos in 2009? Was there a process of academic deliberation through which we abandoned that ethos, or modified it, or redefined how we would actualize it? Or was this change a largely unreflective move in response to a self-created financial crisis?

On the surface, it thus appears that vast areas of university policy are being driven by financial exigency. It is of course also possible that these changes accord with the priorities of current leadership, which may dissent from the ideals of earli-

er years. Certainly, the University’s revenues has expanded enormously in recent years, so much so that the citation of financial constraint in any given context can appear pretextual. But either way, it is essential that members of the community come to grips with the University’s financial situation and the possibilities for improving it, for that is the context in which we will debate and act on our values.

In the budget town halls of December 7, 2023 and February 5, 2024, the University’s leaders laid out a plan to balance the budget through reducing expenses and raising revenue. They suggested that while a portion of the deficit would be addressed by targeted cuts, 50 percent of the deficit could be ameliorated

through the combined revenue streams of technology transfer and increased enrollments in postgraduate degree and professional certification programs. The provost and chief financial officer have also issued the very sensible caveat that the temporalities of these processes differ: one can cut expenses faster than one can expand existing programs or develop new ones. Nevertheless, the existence of a plan, and disciplined adherence to it, are important. The provost averred in the latest budget town hall, on November 11, 2024, that an important reason that rating agencies had not downgraded the University’s bond rating is because of their faith in our “plan.”

In what follows, I present an

assessment of the University’s plan along two fronts. First, I offer some cautions predicated on comparative data about the likelihood that the University can quickly generate revenue from either technology transfer or professional certification programs. Second, I review and critique prior budgetary projections offered by the University’s leadership to the Board of Trustees. Over more than a decade, these projections erred uniformly in their optimism. This, I suggest, was not an error of science but a feature of the system. Flattering their own prescience and boasting of their control does more than enhance our leaders’ own luster; by promising balanced budgets in the future, they free themselves to

spend more in the present. In the world of contemporary academic leadership in which candidates jump from institution to institution, the inventors of shiny baubles move on, leaving financial wreckage and damaged institutions to the next generation. The final section describes and discusses the model of leadership that got us into this mess and the specific damages being wreaked at the University of Chicago.

“Technology transfer” refers to the monetization of discoveries through university research by licensing them for development by private entities. This entire category of revenue is

CONTINUED ON PG. 12

CONTINUED FROM PG. 11

largely a modern creation. Before the Bayh-Dole Act of 1980, patents given for discoveries made through publicly funded research were held by the People of the United States. As a consequence, in 1979, on the eve of Bayh-Dole, 97 American universities received a total of only 264 patents. The Bayh-Dole Act sought to direct the flow of research by encouraging the monetization of its results: it granted ownership of discoveries made in the course of federally funded research to nonprofits (including universities) and certain categories of small businesses where that research was conducted. Nearly a quarter century later, in 2003, applications for patents by universities had increased to more than 7,500. In the same year, American universities struck some 4,500 licenses to private corporations to develop commercial applications for their discoveries (reviews of this history are available here, here, and here).

Can one count on making money by this means? The database of the Association of University Technology Managers suggests that in the early decades of Bayh-Dole, two thirds of the revenue tracked in its study went to a mere 13 institutions. Since then, the data have become harder to track because universities are so often investors in the firms to which their discoveries are licensed. Income no longer derives simply from licensing, and likewise, costs are harder to aggregate. As for the University of Chicago, I was told by an officer of the University in February 2024 that the University of Chicago has never received, in any year of its history, significant net revenue from its patents. And yet, the “plan” is to cover, in the

near future, 25 percent of the structural deficit—perhaps $60 million per year—via technology transfer?

What about postgraduate degrees and professional certification programs? In the budget town halls, the provost and chief financial officer showed slides documenting the volume of enrollment at similar programs at peer institutions and the magnitude of tuition revenue that those institutions regularly earn. Comparative evidence from the world of on-line learning urges caution. In that “space” (to use the metaphor employed by the provost), the institutions

that dominated enrollment and earnings in its early days— Southern New Hampshire University, Georgia Tech, and Arizona State prominent among these—have maintained their dominance, despite the efforts of more highly-ranked institutions to break in. Do we imagine that the market for professional certification is suddenly going to expand and that a significant percentage of those customers will flock to the new kid on the block, rather than the established players? Certainly, the history of online learning suggests that Harvard, which currently dominates the “space” of

professional certification, is not going simply to yield market share to us, whether from inattention or generosity. Gold does not lie at the end of this rainbow. There is also a very good reason, specific to the University of Chicago, to be skeptical of the “plan’s” reliance on professional certification programs. In an earlier period of handwringing about the budget, which stretched from 2016 into 2017 and included a liquidity crisis that led to a fire sale of University properties, the University’s leadership also announced a plan to increase revenue, based on—wait for it—increased en-

rollment in postgraduate degree and professional certification programs. This history deserves some scrutiny.

The briefings provided by the president to the trustees, and by the provost to the trustees’ “Financial Planning Committee,” routinely present projections of revenue and expenditures, as regards both specific endeavors and the University as a whole. Here, I set aside projections about specific projects, lest I seem to cast aspersion on the academic worth of any given endeavor. But even with regard to the budget as a whole, in the

When I say that the budget projections of the university’s leadership have consistently been “optimistic,” I refer not to an affective relation to the future, but to leadership’s claims about its own prescience and skill.

documentation available to me, the projections offered by the University’s leadership have consistently been wildly optimistic.

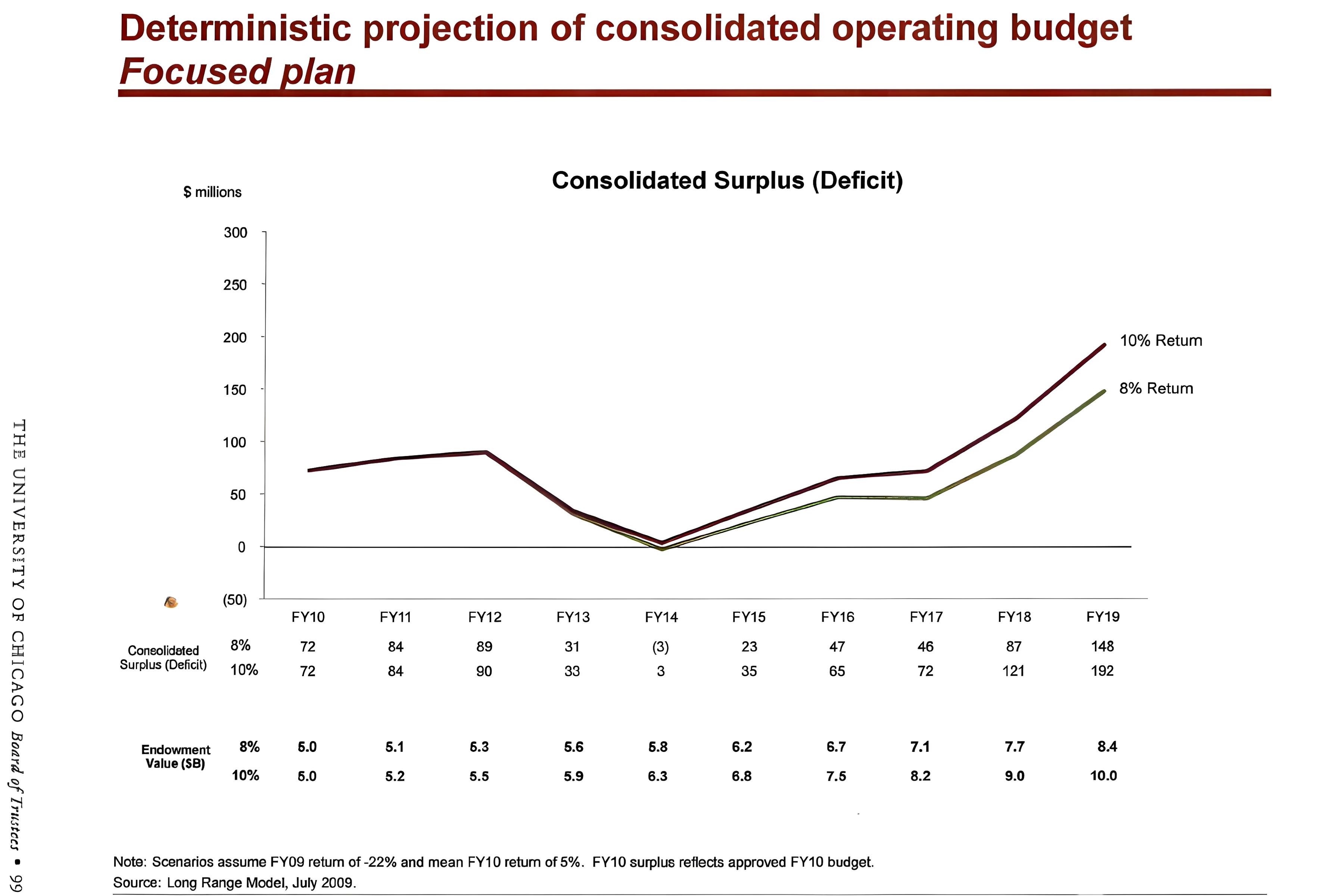

In 2009, for example, in a 302-page strategic plan entitled Moving Forward. The University’s Strategic Approach to Risks and Opportunities, presented to the trustees in September in Washington, D.C., the University of Chicago’s leadership presented both a deterministic projection and a Monte Car -

lo simulation of the operating budget. It used each method for two scenarios: one holding commitments steady, and the other if the trustees approved leadership’s plan for investment in new areas. Its deterministic projection had the University running an operating surplus from 2010 through 2019, with only one year at balance (figure 1); its Monte Carlo simulation allowed for the possibility of deficits under certain variables, but its median projection under conditions of lower endowment returns nev-

ertheless displayed surpluses nearly every year (figure 2).

In the same document, the University’s leadership evaluated the impact of borrowing between $600 million and $1 billion between 2009 and 2014, “to continue to fund strategic capital plans.” It allowed that, at the higher level of borrowing, “it appears more likely that we will have a rating downgrade.” Therefore, “to move forward with new borrowing, we need to show balanced operations and sustained net operating cash

surplus positions.” In 2009, the University’s “notes and bonds payable” amounted to $2.415 billion. In 2014, that number was $3.7 billion. Why did we borrow so much more than the worstcase scenario? A partial explanation, at least, can be gleaned from the University’s public financial statements. Over the five-year period from 2009–2014, the University never showed “balanced operations” and never achieved a “net operating surplus cash position.” “Net cash used in operating activities” was negative

every single year. In total over that period, operating activities “used” $390 million more in cash than they “provided.” (The terms are those of the financial statements.)

Having borrowed $300 million more than its own highest (worst?) projection from 2009, the University’s leadership presented the trustees with a series of “Financial Frameworks,” outlining efforts at “Cost Containment,” “Administrative Transformation,” “Strategic Sourcing,” and the like. In 2016, the provost told the trustees’ Financial Planning Committee that these efforts would result in $419 million dollars in savings over five years, which would free up funds “to support strategic investments and create a path to balanced budgets.” (The combination of capital letters and precise numbers was presumably intended to convey seriousness and rigor.) By 2017—one year later!— “Financial Framework II” already required updating. As the chart outlining the revision makes clear (figure 3), the University had never achieved the balanced budgets, to say nothing of the surpluses, envisioned in 2009. Nor would we achieve the budget surplus of $21 million envisioned in “Financial Framework II.” Instead, “FF2 update,” as it was called, promised a balanced budget by FY20.

In FY20, the University of Chicago ran a deficit of $185 million.

When I say that the budget projections of the University’s leadership have consistently been “optimistic,” I refer not to an affective relation to the future, but to leadership’s claims

CONTINUED ON PG. 14

As children of Bayh-Dole, they think of the university fundamentally as a tax-free technology incubator—an engine, as it were, for private wealth creation.

CONTINUED FROM PG. 13

about its own prescience and skill. The principal effect of this self-aggrandizing behavior has been to persuade persons and institutions in different relations of oversight to the University— both the trustees and ratings agencies—that the leadership

should be free to spend more because it has things under control. It has a plan.

This brief assessment of the University’s current plan, and review of its earlier plans, raises questions of two kinds, concern-

ing the model of leadership that over 20 years created this mess and concerning the specific situation of the University of Chicago today. I take these in turn.

In recent years, when the need was felt to justify the extraordinary pay packages given to University leaders, it was

common to compare the size and complexity of universities to those of for-profit corporations. The University of Chicago is unquestionably a multi-billion-dollar corporation. But the relationship of its leaders to the health of the enterprise is fundamentally different from that of

officers of for-profit companies to their enterprises. Persons paid partially in shares that they are required to hold are, at least in theory, incentivized to pursue the long-term health of the entity as measured by the price of its stock. No similar incentive,

CONTINUED FROM PG. 14

nor any similar constraint, exists for leaders of universities.

On the contrary, leaders of universities—particularly young persons in leadership roles—are strongly incentivized to pursue legible forms of “growth” and “innovation,” the better to burnish their resumé for the next job. For this, money is required. At the University of Chicago, for a long time this money was found on the bond market; of late, we are bleeding nearly all parts of the University to pay for others.

Perversely, despite the absence of contractual guardrails on the conduct of leadership, leaders of universities differ from their corporate brethren in another significant way. They do their business in secret. When Ford Motor Company decides to shift production toward electric vehicles or, indeed, back to internal combustion engines, it announces this decision to shareholders; the ramifications of this for the operation or viability of particular plants and

subsidiaries is openly discussed; and so on. Large-scale decisions about priorities at private universities and, indeed, at many public ones, are often made out of sight and never announced. It is a matter of the deepest irony that contemporary universities so uniformly subscribe to a model of leadership in which power is concentrated and information withheld.

The briefing books of the University of Chicago’s Board of Trustees reveal that the trustees are occasionally informed when leadership believes cuts to the budget in one or another area will harm institutional operations and diminish excellence. But far more regularly they have been told that, on this occasion, a rabbit will actually be pulled from a hat or, rather, the very rabbit that one has always been promised will finally be pulled from the very same hat from which we have failed to pull one in the past: efficiencies will be wrung from the further concentration of “services”; despite

a decade of failure, this time we really will enroll more fee-paying students in certification education. The ongoing credulity of the trustees is hard to explain except as an astonishing failure of judgment.

But perhaps we are mistaken in assuming a set of shared values between faculty and leadership, and likewise, perhaps we err in attributing mere credulity to the trustees. If, instead of positing that the University’s leaders actually believe their plan, one were to examine what is in fact happening at the University, a very different plan comes into view. For a decade or more, but in an accelerating way under current leadership, the health of a huge number of departments and programs at the university is being starved. More and more instruction is being delivered by staff who are not assessed on the basis of their contributions to knowledge; the number of faculty is decreasing in proportion to the student body. We decline to be fully ADA compliant; we

renege occasionally on our commitment to need-blind admissions; we pay women worse than men; the library has become at best second-rate. We are slowly but deliberately abandoning a core ethos of the University: that teaching in a context of “rigorous inquiry”—teaching students to become critics and creators of knowledge—requires that instruction be delivered by persons engaged in research.

Mine is a partisan view, in the sense that it is informed by a deeply held but nevertheless personal view of the ideals of the research university. But there can be no doubt that a great institution, with a deep call upon our affections, is being transformed. At the same time, the wider foundation of the health of higher education as a whole, in the form of public opinion and legislative support, is clearly in flux. I exhort all those who care about future of the University of Chicago to study the situation, form an opinion, and speak up.

Clifford Ando is the Robert O. Anderson Distinguished Service Professor in the Departments of Classics and History and in the College, as well as Extraordinary Professor in the Department of Ancient Studies at Stellenbosch University.

As I have pointed out elsewhere, all this is occurring while the University makes more and more money, in part because it continues to increase tuition for the very students it shortchanges. So far as I can tell, this is because the current leadership of the University—including the trustees—have a very different conception of the purpose of the University. As children of Bayh-Dole, they think of the University fundamentally as a tax-free technology incubator— an engine, as it were, for private wealth creation. Of course, it can only maintain its tax-free status by teaching students, but nothing requires that we do this as well as possible or that monies raised from tuition be spent on education.

The flaws of RideSmart and its new policy changes are leaving students behind.

By KACI SZIRAKI

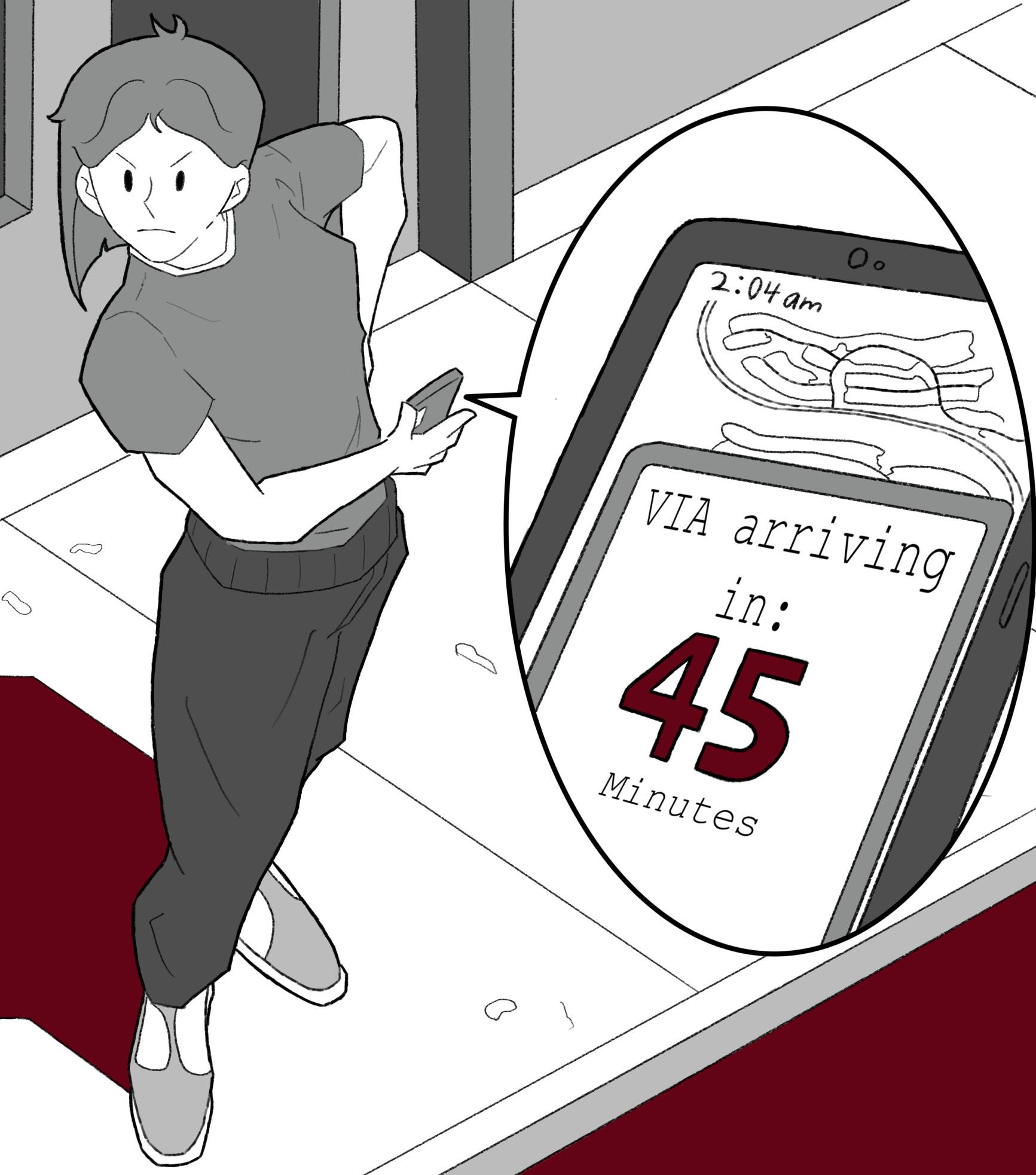

It’s 2 a.m. on a Friday evening, and I stand outside Campus North Residential Commons with two friends. We need to get back to Woodlawn. It’s a 20-minute walk, it’s cold, it’s dark. It’s a trek none of us want to make.

As I pull up the RideSmart by Via app, UChicago’s new free rideshare system, I type in our destination and wait for a car, only to see that the closest Via

is more than 15 minutes away. Refreshing the app only shows Vias with longer wait times, and tonight I’m not lucky enough to get a Lyft. We end up walking back to Woodlawn, tired, cold, and frustrated—a recurring experience that comes with using RideSmart.

Launched on September 1, 2024, RideSmart by Via recently replaced UChicago’s previous Lyft program. Originally implemented in 2021, the Lyft

program offered students up to 10 free rides per month between 5 p.m. and 4 a.m., though that number was reduced to seven rides per month in 2023. As of this academic year, UChicago has completely moved away from that system with the release of RideSmart. Now, from 5 p.m. to 4 a.m., students have access to unlimited free rides—Vias— within a service area including the campus and wider Hyde Park area, including access to the Red

and Green train lines. The program aims to provide fast, free, and user-friendly transportation for all UChicago students. After downloading the app, students are able to easily navigate the platform to add passengers and choose pickup and drop-off locations around campus, offering intuitive solutions to safety concerns.

This system soon proved flawed. Getting a Via is often incredibly slow, with wait times

of up to 20 minutes, especially later in the evenings when safety concerns are at their peak. As Vias stop to pick up others on the way, wait times stretch to even greater lengths; walking ultimately becomes a faster option. Yet traveling by foot, especially at night, brings up safety concerns. Students have to choose between wanting to get somewhere quickly and wanting to get there securely, but slowly.

Additionally, waiting for an expected Via to arrive while standing outside poses its own safety risk, making the long wait times dangerous for students who find themselves unable to seek shelter indoors as well.

The University’s Department of Safety and Security advertises RideSmart as a way to keep students safe when traveling around campus at night, though this positive benefit dwindles if

vehicles can’t arrive in a timely manner. If walking from location to location is faster than waiting, and if waiting itself poses a safety issue, then booking a Via becomes more of a hindrance than a help, and the program loses its value.

RideShare does, however, have one practical merit: Lyfts. Occasionally, if there are no Vias available or the wait time for a Via exceeds 15 minutes, the app offers a free Lyft ride. The main

distinction between Vias and Lyfts is that the former operates on a carpooling system. Vias may stop to pick up and drop off other passengers before getting to a student’s destination. Vans can hold up to six people, and cars can hold up to four. A Lyft, however, will take the student directly to their destination without making stops along the way, providing smoother and more efficient transportation. Lyfts also tend to arrive faster and

provide the same level of safety and quality as expected of a Via. As a result, I only use RideSmart if I manage to secure a Lyft.

After RideSmart’s initial launch, students began using an easy loophole to try and increase the chances of getting a Lyft. One option on RideSmart allowed people to add up to three additional riders. Since Vias pick up students until they reach capacity, adding extra passengers raises the chances for the cars to exceed the max amount. If a Via is unable to transport an entire group in a timely manner, RideSmart will offer a Lyft instead. Knowing this, some people chose to increase the number of extra passengers to three regardless of whether or not they needed the additional space. For students who prefer quicker wait times, no additional stops, and avoiding carpooling with others, this exploit made it far easier to secure a Lyft that can provide those benefits.

Now, the University has placed limitations on the Lyft feature. On Thursday, November 14, Eric Heath, associate vice president for safety & security, and Mike Hayes, interim dean of students in the University, sent an email to students announcing a new policy update to the program that intends to reduce the number of Lyfts students can book through RideSmart. The email states, “Unfortunately, we have learned that a significant number of riders are requesting rides and adding multiple guests in order to get Lyft rides, or cancelling booking requests in quick succession until they get the Lyft option.” The email additionally states, “Effective beginning today, November 14, the Via program’s guest policy will be revised to allow students to request a ride for themselves

plus one guest.”

Evidently, the misuse of the RideSmart system in order to get Lyfts had reached a point where the University decided to prevent these tactics. Their solution, however, does not solve the root problem that people are having with the Vias, nor does it address the reasoning behind why students are attempting to get Lyfts in the first place. The only change this new policy brings is making it harder for students to travel in groups.

The “overwhelmingly positive feedback” that students have given to the RideSmart system, as mentioned in their statement, does not differentiate whether that same feedback is for the Vias themselves, or if the majority of RideSmart users enjoy it for the easy access to Lyfts. One anonymous Sidechat user even posted a meme stating, “Eric Heath when he realizes the ‘overwhelmingly positive feedback’ for RideSmart was because we were all getting Lyfts and not Vias.” The post garnered 1,000 upvotes. Perhaps the “overwhelmingly positive feedback” the user received suggests how strongly students feel toward the new policy.

Evidently, limiting the number of extra riders that students are allowed to add makes the already inconvenient Via system even less user-friendly. If everyone books a Via separately, can RideSmart guarantee that a whole party will be able to ride together in the same vehicle? If the app is flooded with multiple students trying to get to the same location, who gets priority? What if more than two people don’t have RideSmart? If phones are dead?

The restrictive measures on booking Lyfts do nothing to improve safety and transportation

CONTINUED ON PG. 17

short,

CONTINUED FROM PG. 16

features. Rather, they directly punish the student body for attempting to book a ride from place to place. They forces people to accept the Vias despite their drawbacks or risk their safety by traveling around campus on foot.

and Mike Hayes’s “solution” benefits no one but the University’s wallet.

In short, Eric Heath and Mike Hayes’s “solution” benefits no one but the University’s wallet. If RideSmart hopes to regain popularity, some major changes need to occur, and that doesn’t mean limiting the number of additional riders in a car. It calls for

improvements to the wait times for Vias so students feel like they truly have a safe and comfortable method of transportation around campus.

I would like to believe that eventually the Via service will be faster, more efficient, and better

equipped to meet the demands of the student body. Reflecting on the night my friends and I had to walk back to Woodlawn, I hope similar experiences with RideSmart will start to fade over time. If anyone finds themselves in desperate need of a ride, I hope

By ADAM ZAIDI

that one day RideSmart won’t leave them out in the cold.

For now, we’d better get used to walking.

Kaci Sziraki is a first-year in the College.

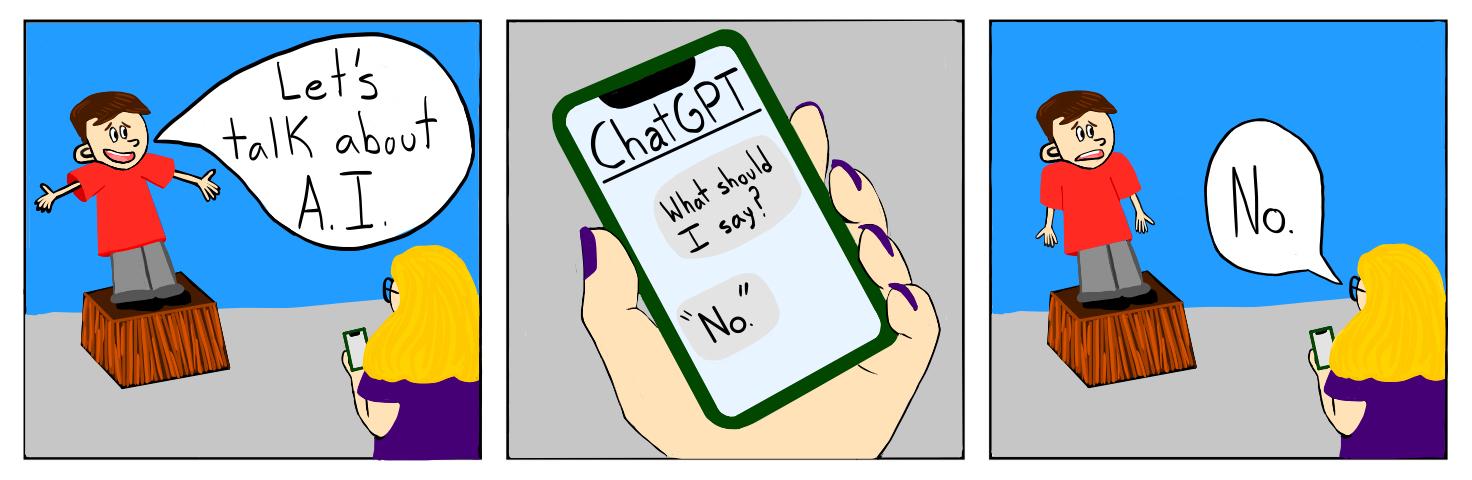

Students confront the role of large language models in the classroom.

When I left high school this past June, it was in shambles. Amid teachers being put on administrative leave for voicing their opinions and a head of school unwilling to address the Israel-Hamas war, one issue that seemed to fly under the radar was students’ use of artificial intelligence (AI) technology in the classroom. Teachers had widely differing policies when it came to the use of large language models (LLMs) in written work. Some strongly advocated for using ChatGPT for research and idea generation, while others scorned the very concept of AI. At points, it felt like I could walk into the cafeteria and see dozens of people prompting ChatGPT for help

with their homework. While the school added a small paragraph in the student handbook about integrity and AI, limits on its use remained unclear and were ineffective at stopping students willing to bend the rules. More than just policy, it seemed that there was no place to critically interrogate the future of LLMs and their implications for higher education. By my senior year, I had written multiple articles about the future of machine learning and writing, but it felt like I was shouting into a void that garnered no conversation in return. Besides a few lame attempts by the school to engage students on AI, the topics seemed to have gotten overshadowed by the more pressing issues facing the school.

When I arrived at UChicago,

I expected a similar indifference to the topic that I was so interested in. This assumption was almost immediately proven wrong when my Language and the Human professor, Tomasz Zyglewicz, emailed our class and attached Ted Chiang’s New Yorker article on ChatGPT. Looking back, it seems absurd that I didn’t expect LLMs to come up in a class about linguistics, but my high school experience made it seem like that was the status quo. Then, when it came to walking into that first class, I was not exactly sure what to expect from my professor visà-vis AI, specifically ChatGPT. Would he immediately condemn its usage, citing its rampant hallucinations, bland writing style, and over-repetition of certain words like “delve” and “more -

over?” Would he embrace it as the future of all things written, advocating for us to prompt it every time we needed? While the first option seemed far more probable than the second, neither made me happy.

What I experienced instead I can only describe as chiefly, “UChicago-y.” After going over the course material and syllabus, Tomasz wrote the words “AGAINST,” “NEUTRAL,” and “FOR” on the chalkboard. He explained that instead of dictating the AI policy himself, he wanted to hear students’ opinions on using AI in our writing. I was pleasantly surprised, as none of my previous teachers had ever consulted us in this way, so I raised my hand almost immediately to respond to his prompt. I’ve always had strong opinions when it comes to AI, and I wasn’t afraid to share them. I hold the belief that there is no point in fully banning the use of AI, as students will always find a way to use it if they are truly motivated to cheat, as I had seen in high school. While ChatGPT doesn’t live up to my standard of academic writing, it is enough for some people to get by on their work. In true UChicago fashion, there was a great

diversity of thought on the topic, with some in favor of banning it on principle and others wanting it to be fully allowed. But one main thread that seemed to be echoed by pretty much everyone was the importance of original, and human thought. One person spoke up, saying, “You can use ChatGPT to write your paper, but then you know that you are writing a C-level paper.” Unlike high school, where writing was usually treated with a level of apathy, I felt that my classmates cared about the quality of their arguments. No one directly advocated for using ChatGPT to replace writing altogether.

As I write this piece, OpenAI has just released their new ‘ChatGPT Pro’ subscription, which costs avid AI users $200 a month to have unlimited access to their newest model, ‘o1 Pro.’ While OpenAI spent plenty of time in its launch video touting o1 Pro’s incredible reasoning and writing capabilities, I am left wondering if it has the ability to write essays with the same level of precision as a motivated student. I would be lying if I said that I never put essay prompts into ChatGPT to see what theses or groundbreaking arguments it

Are there people who will buy ChatGPT o1 Pro and use it on their assignments? Undoubtedly there will be, but I hope not at UChicago.

CONTINUED FROM PG. 17

could come up with. And every time, I would end up wasting time prompting ChatGPT more and more to try and get at the ideas that I felt were the most important—time I could have spent writing the thing myself. In the end, I always feel a bit dissatisfied with ChatGPT. As Chiang wrote, it seems that having access to every corner of

the internet makes your writing a bit bland, like you don’t care. In my classmate’s words, it writes a “C-level paper.” That’s not to say ChatGPT doesn’t have a place in academia as a tool. Its new “search the web” feature has proven invaluable to me for finding sources, or finding that one sentence in a book that I lost. But its value in writing high-level pieces is overhyped.

Until LLMs like ChatGPT, Claude, and Gemini can achieve genuine intellectual nuance and develop a more discerning voice, I will remain skeptical that it can truly exceed the capabilities of a thoughtful, motivated student.

In the end, we settled on permitting AI with citations, and I left feeling excited about the level of enthusiasm surrounding

the conversation about AI and pedagogy. While it seems obvious that UChicago would attract students who enjoy learning and the process of fleshing out their thoughts in words, I still felt a sense of pride in the fact that, at the very least, my Hum class believed in our own reasoning skills over a computer’s. Are there people who will buy ChatGPT o1 Pro and use it on

their assignments? Undoubtedly there will be, but I hope not at UChicago. And, while I still have over 11 quarters of UChicago to go, this first one give me hope that I will continue to have enlightening conversations about the future of AI, teaching, and learning.

Adam Zaidi is a first-year in the College.

“Seconds after ringing in Y2K, a fan is lodged in somebody’s head, a toy car burns off a face, and a Tamagotchi murders another.” Head Arts Editor Miki Mukawa reviews A24’s Y2K and interviews director Kyle Mooney.

By MIKI MUKAWA | Head Arts Editor

I notoriously hate horror movies. I am the buzzkill who will tell her friends to never, ever, put one on.

I blindly walked into Doc Films’s early screening of Y2K knowing one thing: Kyle Mooney was its director, and therefore it was going to be funny.

And it was funny. The film introduces us to best friends Eli (Jaeden Martell) and Danny (Julian Dennison), two high schoolers in 1999. This year, they decide, they’re going to do something wild. They sneak alcohol, crash a party, and (attempt to) flirt with girls. Their teenage awkwardness and relatability initially introduce this film as a funny and relatable coming-of-age film.