COMMENTS by Phillip Huscher

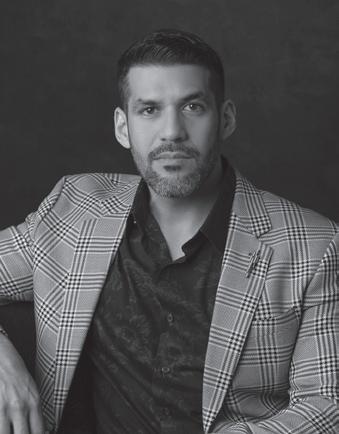

JESSIE MONTGOMERY

Born December 8, 1981, New York City

Starburst

Last February, when Jessie Montgomery won the Grammy Award for Best Contemporary Composition, Classical, for Rounds, she admitted backstage that it was something of a childhood dream. “You don’t necessarily say it out loud all the time,” she said. But Montgomery, who stepped down as the Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s Mead Composer-in-Residence in 2024, has plenty to talk about.

Since Montgomery moved to Chicago from her longtime home on New York’s Lower East Side in 2022, she has become a central figure in the city’s music community, and several of her frequent collaborators are now based here. She never loses sight of the fact that this is the city where Florence Price, the pioneering Black composer, lived and worked in relative isolation, and she participated in events surrounding the Chicago Symphony’s first performances of Price’s Third Symphony in May 2022. She has offered composition lessons to six local high school students on a full scholarship through the Negaunee Music Institute’s Young Composers Initiative. In 2023 the Chicago Tribune named her Chicagoan

of the Year for Classical Music. She was already Musical America’s 2023 Composer of the Year.

As the Chicago Symphony’s resident composer, Montgomery was commissioned to write three works during her tenure. The first, Hymn for Everyone, which Montgomery began during the pandemic, was premiered under Riccardo Muti in April 2022. It is based on a hymn that she wrote after facing several personal and professional challenges, including the death of her mother and an intense period of writer’s block. (The Orchestra’s performance is included on the CSO Resound recording, Contemporary American Composers.) The second work, Transfigure to Grace, which Muti and the Orchestra introduced in May 2023, is Montgomery’s response to The 1619 Project, which acknowledged the arrival of the first enslaved Africans brought to the United States. The third was Procession, a percussion concerto—her first extended work for percussion—composed for Cynthia Yeh, principal of the Orchestra’s percussion section, and premiered in May 2024, led by Manfred Honeck.

Montgomery’s Starburst was composed in 2012 for string orchestra and later arranged for full orchestra. It is the original version that is performed at this concert.

COMMENTS

Jessie Montgomery on Starburst

This brief, one-movement work for string orchestra is a play on imagery of rapidly changing musical colors. Exploding gestures are juxtaposed with gentle fleeting melodies in an attempt to create a multidimensional soundscape. A common

WILLIAM GRANT STILL

definition of a starburst—“the rapid formation of large numbers of new stars in a galaxy at a rate high enough to alter the structure of the galaxy significantly”—lends itself almost literally to the nature of the performing ensemble that premiered the work, the Sphinx Virtuosi, and I wrote the piece with their dynamic in mind.

Born May 11, 1895; Woodville, Mississippi Died December 3, 1978; Los Angeles, California

Mother and Child

COMPOSED

1943, for violin and piano; later arranged for string orchestra

FIRST PERFORMANCE date unknown

INSTRUMENTATION

strings

APPROXIMATE PERFORMANCE TIME 7 minutes

William Grant Still and Florence Smith, who would later make her name as Florence Price, grew up only a few city blocks apart in the heart of Little Rock, Arkansas. Theirs was a neighborhood of Black professionals. Ninth Street, which ran between the Stills’ house on West

Fourteenth, and the Smith house, near the corner of Broadway and Seventh, was the center of Black life in Little Rock. The Still and Smith families were close. They moved in the same circles and were interested in the same intellectual matters. The Smiths and the Stills both attended the Allison Presbyterian Church, a favorite of Little Rock’s prominent Black citizens.

Florence and William, eight years younger, were both students at Mifflin W. Gibbs High School, where William’s mother, Carrie Still, taught English and wrote and directed plays. Florence and William became lifelong friends. And in the early 1930s, after they had left Little Rock to study music and begin their careers as composers, they each wrote symphonies that are now considered the bedrock of Black orchestral music: William Grant Still’s

Afro-American Symphony in 1930, Florence Price’s First Symphony, in E minor, in 1932. Still’s, which was premiered by the Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra in 1931, would take its place in the history books as the first symphony by a Black American composer to be performed by a major orchestra. And Price’s, first performed by Frederick Stock and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra on a historic night in the Auditorium Theatre just two years later, was heralded as the first music composed by a Black woman played by one of the big American orchestras. (Chicago got its first taste of Still’s music the following evening, when Katherine Dunham and Ruth Page’s company introduced his ballet La guiablesse.)

patch things up, as their history and their relationship clearly mattered to both of them. Years later, after Price’s death, Still kept in touch with Price’s daughter and continued to champion her music.

The fact that Still became known as the “Dean of African American Composers,” while Price looked for many years as if she would become one of the accomplished women whose names fade from history, is part of a larger and complex story. For many years, the disparity in their success did not seem to disturb their friendship, although when they eventually came to blows, ostensibly over an unanswered letter, that friction may well have been the root cause. They were careful to

Still moved to Los Angeles in 1934, the year the Chicago Symphony first played his music—the AfroAmerican Symphony—in order to work in the film industry. But in 1943 he walked away from the most lucrative assignment of his career, working on the soundtrack for Stormy Weather, starring Lena Horne and Cab Calloway, because he could not stand the way Black people were being portrayed in the musical. That same year, he received a commission for a violin and piano piece from Louis Kaufman, who had played on many of Hollywood’s most beloved soundtracks, including Gone with the Wind and Rebecca, and would make the first recording of Vivaldi’s nearly forgotten The Four Seasons four years later.

The suite that Still composed has three movements, each of them inspired by the work by one of the Harlem Renaissance artists. The second movement is indebted to a series of pieces on the theme of the mother and child by Sargent Claude Johnson, who had moved to the Bay Area and became

opposite page: William Grant Still, portrait by Carl Van Vechten (1880–1964), 1949. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division | this page: Portrait of the composer’s mother, Carrie Lena Fambro Still (1869–1927), ca. 1890s. Miriam Matthews Photograph Collection, OpenUCLA Collections

COMMENTS the first Black artist on the West Coast to gain a national reputation. Still eventually took its soaring violin melody and rich, shifting piano chords and arranged the music for string orchestra. Although Still did not say so, this simple yet emotionally complex music is also

JOHANNES BRAHMS

Born May 7, 1833; Hamburg, Germany

Died April 3, 1897; Vienna, Austria

a kind of family portrait, reflecting the story of the young Carrie Lena Fambro Still, recently a mother and a widow, who left her Mississippi home with her infant son late in 1895 to make a life for them in Little Rock.

Symphony No. 2 in D Major, Op. 73

COMPOSED 1877, summer

FIRST PERFORMANCE

December 30, 1877; Vienna, Austria

INSTRUMENTATION

2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, strings

APPROXIMATE PERFORMANCE TIME

48 minutes

Within months after the long-awaited premiere of his First Symphony, Brahms produced another one. The two were as different as night and day—logically enough, since the first had taken two decades of struggle and soul-searching and the second was written over a summer holiday. If it truly was

Beethoven’s symphonic achievement that stood in Brahms’s way for all those years, nothing seems to have stopped the flow of this new symphony in D major. Brahms had put his fears and worries behind him.

This music was composed at the picture-postcard village of Pörtschach, on the Wörthersee, where Brahms had rented two tiny rooms for his summer holiday. The rooms apparently were ideal for composition, even though the hallway was so narrow that Brahms’s piano couldn’t be moved up the stairs. “It is delightful here,” Brahms wrote to Fritz Simrock, his publisher, soon after arriving, and the new symphony bears witness to his apparent delight. Later that summer, when Brahms’s friend Theodor Billroth, an amateur musician, played through the score for the first time, he wrote to the composer at once: “It is all rippling streams, blue sky, sunshine, and cool green shadows. How

beautiful it must be at Pörtschach.” Eventually listeners began to call this Brahms’s Pastoral Symphony, again raising the comparison with Beethoven. But if Brahms’s Second Symphony has a true companion, it is the violin concerto he would write the following summer in Pörtschach—cut from the same D major cloth and reflecting the mood and even some of the thematic material of the symphony.

When Brahms sent off the first movement of his new symphony to Clara Schumann, she predicted that this music would fare better with the public than the tough and stormy First, and she was right. The first performance, on December 30, 1877, in Vienna under Hans Richter, was a triumph, and the third movement had to be repeated. When Brahms conducted the second performance, in Leipzig just after the beginning of the new year, the audience was again enthusiastic. But Brahms’s real moment of glory came late in the summer of 1878, when his new symphony was a great success in his native Hamburg, where he had twice failed to win a coveted music post. Still, it would be another decade before the Honorary

Freedom of Hamburg—the city’s highest honor—was given to him, and Brahms remained ambivalent about his birthplace for the rest of his life. In the meantime, the D major symphony found receptive listeners nearly everywhere it was played.

From the opening bars of the Allegro non troppo—with their bucolic horn calls and woodwind chords— we prepare for the radiant sunlight and pure skies that Billroth promised. And, with one soaring phrase from the first violins, Brahms’s great pastoral scene unfolds before us. Although another of Billroth’s letters to the composer suggests that “a happy, cheerful mood permeates the whole work,” Brahms knows that even a sunny day contains moments of darkness and doubt—moments when

opposite page: Johannes Brahms, ca. 1872 | this page: Pörtschach on the Wörthersee in Carinthia, Austro-Hungary, where Brahms summered while writing his Second Symphony. Engraving and print by the Oester Lloyd Art Institute in Trieste after a drawing by Markus Pernhart (1824–1871)

pastoral serenity threatens to turn tragic. It’s that underlying tension— even drama—that gives this music its remarkable character. A few details stand out: two particularly bracing passages for the three trombones in the development section, and much later, just before the coda, a wavering horn call that emerges, serene and magical. This is followed, as if it were the most logical thing in the world, by a jolly bit of dance-hall waltzing before the music flickers and dies.

Eduard Hanslick, one of Brahms’s champions, thought the Adagio “more conspicuous for the development of the themes than for the worth of the themes themselves.” Hanslick wasn’t the first critic to be wrong—this movement has very little to do with development as we know it—although it’s unlike him to be so far off the mark when dealing with music by Brahms. Hanslick did notice that the third movement has the relaxed character of a serenade. It is, for all its initial grace and charm, a serenade of some complexity, with two frolicsome presto passages (smartly

disguising the main theme) and a wealth of shifting accents.

The finale is jubilant and electrifying; the clouds seem to disappear after the hushed opening bars, and the music blazes forward, almost unchecked, to the very end. For all Brahms’s concern about measuring up to Beethoven, he seldom mentioned his admiration for Haydn and his ineffable high spirits, but that’s who Brahms most resembles here. There is, of course, the great orchestral roar of triumph that always suggests Beethoven. But many moments are pure Brahms, like the ecstatic clarinet solo that rises above the bustle only minutes into the movement, or the warm and striding theme in the strings that immediately follows. The extraordinary brilliance of the final bars—as unbridled an outburst as any in Brahms—was not lost on his great admirer, Antonín Dvořák, when he wrote his Carnival Overture.

Phillip Huscher has been the program annotator for the Chicago Symphony Orchestra since 1987.

Una traducción al español de las notas del programa está disponible en cso.org/program.

CHICAGO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA

The Chicago Symphony Orchestra— consistently hailed as one of the world’s best—marks its 134th season in 2024–25. The ensemble’s history began in 1889, when Theodore Thomas, the leading conductor in America and a recognized music pioneer, was invited by Chicago businessman Charles Norman Fay to establish a symphony orchestra. Thomas’s aim to build a permanent orchestra of the highest quality was realized at the first concerts in October 1891 in the Auditorium Theatre. Thomas served as music director until his death in January 1905, just three weeks after the dedication of Orchestra Hall, the Orchestra’s permanent home designed by Daniel Burnham.

Frederick Stock, recruited by Thomas to the viola section in 1895, became assistant conductor in 1899 and succeeded the Orchestra’s founder. His tenure lasted thirty-seven years, from 1905 to 1942—the longest of the Orchestra’s music directors. Stock founded the Civic Orchestra of Chicago— the first training orchestra in the U.S. affiliated with a major orchestra—in 1919, established youth auditions, organized the first subscription concerts especially for children, and began a series of popular concerts.

Three conductors headed the Orchestra during the following decade: Désiré Defauw was music director from 1943 to 1947, Artur Rodzinski in 1947–48, and Rafael Kubelík from 1950 to 1953. The next ten years belonged to Fritz Reiner, whose recordings with the CSO are still considered hallmarks. Reiner invited Margaret Hillis to form the Chicago Symphony Chorus in 1957. For five seasons from 1963 to 1968, Jean Martinon held the position of music director.

Sir Georg Solti, the Orchestra’s eighth music director, served from 1969 until 1991. His arrival launched one of the most successful musical partnerships of our time. The CSO made its first overseas tour to Europe in 1971 under his direction and released numerous award-winning recordings. Beginning in 1991, Solti held the title of music director laureate and returned to conduct the Orchestra each season until his death in September 1997.

Daniel Barenboim became ninth music director in 1991, a position he held until 2006. His tenure was distinguished by the opening of Symphony Center in 1997, appearances with the Orchestra in the dual role of pianist and conductor, and twenty-one international tours. Appointed by Barenboim in 1994 as the Chorus’s second director, Duain Wolfe served until his retirement in 2022.

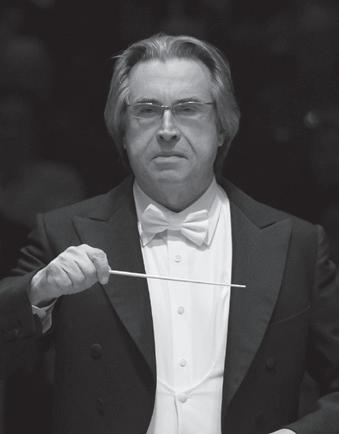

In 2010, Riccardo Muti became the Orchestra’s tenth music director. During his tenure, the Orchestra deepened its engagement with the Chicago community, nurtured its legacy while supporting a new generation of musicians and composers, and collaborated with visionary artists. In September 2023, Muti became music director emeritus for life.

In April 2024, Finnish conductor Klaus Mäkelä was announced as the Orchestra’s eleventh music director and will begin an initial five-year tenure as Zell Music Director in September 2027.

Carlo Maria Giulini was named the Orchestra’s first principal guest conductor in 1969, serving until 1972; Claudio Abbado held the position from 1982 to 1985. Pierre Boulez was appointed as principal guest conductor in 1995 and was named Helen Regenstein Conductor Emeritus in 2006, a position he held until his death in January 2016. From 2006 to 2010, Bernard Haitink was the Orchestra’s first principal conductor.

Pianist Daniil Trifonov is the CSO’s Artistin-Residence for the 2024–25 season.

The Orchestra first performed at Ravinia Park in 1905 and appeared frequently through August 1931, after which the park was closed for most of the Great Depression. In August 1936, the Orchestra helped to inaugurate the first season of the Ravinia Festival, and it has been in residence nearly every summer since.

Since 1916, recording has been a significant part of the Orchestra’s activities. Recordings by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and Chorus— including recent releases on CSO Resound, the Orchestra’s recording label launched in 2007—have earned sixty-five Grammy awards from the Recording Academy.

Chicago Symphony Orchestra

Klaus Mäkelä Zell Music Director Designate

Daniil Trifonov Artist-in-Residence

VIOLINS

Robert Chen Concertmaster

The Louis C. Sudler Chair, endowed by an anonymous benefactor

Stephanie Jeong

Associate Concertmaster

The Cathy and Bill Osborn Chair

David Taylor* Assistant Concertmaster

The Ling Z. and Michael C. Markovitz Chair

Yuan-Qing Yu* Assistant Concertmaster

So Young Bae

Cornelius Chiu

Gina DiBello

Kozue Funakoshi

Russell Hershow

Qing Hou

Matous Michal

Simon Michal

Sando Shia

Susan Synnestvedt

Rong-Yan Tang

Baird Dodge Principal

Danny Yehun Jin Assistant Principal

Lei Hou

Ni Mei

Hermine Gagné

Rachel Goldstein ‡

Mihaela Ionescu

Melanie Kupchynsky

Wendy Koons Meir

Joyce Noh §

Ronald Satkiewicz

Florence Schwartz

VIOLAS

Teng Li Principal

The Paul Hindemith Principal Viola Chair

Catherine Brubaker

Youming Chen

Sunghee Choi

Wei-Ting Kuo

Danny Lai

Weijing Michal

Diane Mues ‡

Lawrence Neuman

Max Raimi

CELLOS

John Sharp Principal

The Eloise W. Martin Chair

Kenneth Olsen Assistant Principal

The Adele Gidwitz Chair

Karen Basrak

The Joseph A. and Cecile Renaud

Gorno Chair

Richard Hirschl

Daniel Katz

Katinka Kleijn

Brant Taylor

The Blickensderfer Family Chair

Riccardo Muti Music Director Emeritus for Life

BASSES

Alexander Hanna Principal

The David and Mary Winton Green Principal Bass Chair

Alexander Horton Assistant Principal

Daniel Carson

Ian Hallas

Robert Kassinger

Mark Kraemer

Stephen Lester ‡

Bradley Opland

Andrew Sommer

HARP

Lynne Turner

FLUTES

Stefán Ragnar Höskuldsson Principal

The Erika and Dietrich M. Gross Principal Flute Chair

Emma Gerstein

Jennifer Gunn

PICCOLO

Jennifer Gunn

The Dora and John Aalbregtse Piccolo Chair

OBOES

William Welter Principal

Lora Schaefer Assistant Principal

Scott Hostetler

ENGLISH HORN

Scott Hostetler

CLARINETS

Stephen Williamson Principal

John Bruce Yeh Assistant Principal

The Governing Members Chair

Gregory Smith

E-FLAT CLARINET

John Bruce Yeh

BASSOONS

Keith Buncke Principal

William Buchman Assistant Principal

Miles Maner

HORNS

Mark Almond Principal

James Smelser

David Griffin

Oto Carrillo

Susanna Gaunt

Daniel Gingrich

TRUMPETS

Esteban Batallán § Principal

The Adolph Herseth Principal Trumpet Chair, endowed by an anonymous benefactor

Mark Ridenour Assistant Principal

John Hagstrom

The Bleck Family Chair

Tage Larsen

TROMBONES

Jay Friedman Principal

The Lisa and Paul Wiggin Principal Trombone Chair

Michael Mulcahy Acting Associate Principal

Charles Vernon

BASS TROMBONE

Charles Vernon

TUBA

Gene Pokorny Principal

The Arnold Jacobs Principal Tuba Chair, endowed by Christine Querfeld

TIMPANI

David Herbert Principal

The Clinton Family Fund Chair

Vadim Karpinos Assistant Principal

PERCUSSION

Cynthia Yeh Principal

Patricia Dash

Vadim Karpinos

LIBRARIANS

Justin Vibbard Principal

Carole Keller

Mark Swanson

CSO FELLOWS

Jesús Linárez Violin

The Michael and Kathleen Elliott Fellow

Olivia Reyes Bass

ORCHESTRA PERSONNEL

John Deverman Director

Anne MacQuarrie Manager, CSO Auditions and Orchestra Personnel

STAGE TECHNICIANS

Christopher Lewis Stage Manager

Blair Carlson

Paul Christopher

Chris Grannen

Ryan Hartge

Peter Landry

Joshua Mondie

* Assistant concertmasters are listed by seniority.

‡ On sabbatical

§ On leave

The CSO’s music director position is endowed in perpetuity by a generous gift from the Zell Family Foundation.

The Nancy and Larry Fuller, Gilchrist Foundation, and Louise H. Benton Wagner chairs currently are unoccupied.

The Chicago Symphony Orchestra string sections utilize revolving seating. Players behind the first desk (first two desks in the violins) change seats systematically every two weeks and are listed alphabetically. Section percussionists also are listed alphabetically.

Celebrating Latino composers, conductors and artists

The CSO Latino Alliance is a liaison and partner organization that connects the CSO with Chicago’s diverse communities by creating awareness, sharing insights and building relationships for generations to come. The group encourages individuals and their families to discover and experience timeless music with other enthusiasts in concerts, receptions and educational events.

Be a part of the season with concerts across musical genres highlighting world-class performances and compositions from Esteban Batallán, Lila Downs, Jimmy López Bellido, Elaine Elias and more!