COMMENTS

by Richard E. Rodda

FRÉDÉRIC CHOPIN

Born February 22, 1810; Żelazowa-Wola, Poland

Died October 17, 1849; Paris, France

Ballade No. 1 in G Minor, Op. 23

COMPOSED 1831

A ballad, according to the Random House Dictionary, is “a simple, narrative poem of popular origin, composed in short stanzas, especially one of romantic character and adapted for singing.” The term was derived from an ancient musico-poetic form that accompanied dancing (ballare in medieval Latin, hence ball and ballet), which had evolved into an independent vocal genre by the fourteenth century in the exquisitely refined works of Guillaume de Machaut and other early composers of secular music. The ballad was well established in England as a medium for the recitation of romantic or fantastic stories by at least the year 1500. The form, having adopted a more refined demeanor, became popular in Germany during the late eighteenth century, when it attracted no less a literary luminary than Goethe, whose tragic narrative “Erlkönig” furnished the text for one of Schubert’s most beloved songs. Chopin seems to have been the first

composer to apply the title to a piece of abstract instrumental music, apparently indicating that his four ballades hint at a dramatic flow of emotions such as could not be appropriately contained by traditional classical forms.

According to Arthur Hedley, in the ballades,

Chopin reaches his full stature as the unapproachable genius of the pianoforte, a master of rich and subtle harmony, and above all, a poet— one of those whose vision transcends the confines of nation and epoch and whose mission is to share with the world some of the beauty that is revealed to them alone.

Though the ballades came to form a nicely cohesive set sharing their temporal scale, structural fluidity, and supranational idiom, Chopin composed them over a period of more than a decade. He once suggested to Robert Schumann that he was “incited to the creation of the ballades” by some poems of his Polish compatriot Adam Mickiewicz (1798–1855), whom he met and played for in Paris around 1835. However, the

this page: Chopin, watercolor and ink drawing by fiancée Maria Wodzińska (1819–1896), 1836. National Museum, Warsaw, Poland | opposite page: Frédéric Chopin, detail from an unfinished double portrait with George Sand by Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863), 1838

2

English composer and author Alan Rawsthorne noted,

To pin down these ballades to definite stories is gratuitous and misleading, for in suggesting extra-musical connotations, the attention is distracted from the purely musical scheme which is . . . compelling in itself and completely satisfying.

Rather than obscuring the essential nature of these pieces, the apparently opposing views of Schumann and Rawsthorne lead directly to the very heart of Chopin’s achievement: the near-perfect melding of romantic fantasy and feeling with an Apollonian control of form and figuration.

The first ideas for the Ballade no. 1 (G minor, op. 23) were sketched in May and June 1831, when Chopin was living anxiously in Vienna,

FRÉDÉRIC CHOPIN

almost unknown as a composer and only slightly appreciated as a pianist. By the time the work was completed four years later, however, he had achieved such fame and fortune in Paris that he could dedicate the piece to Baron de Stockhausen, the Hanoverian ambassador to France, whom he counted among his noble pupils. Breitkopf and Härtel published the work in Leipzig in June 1836. (Chalgrin’s Arc de Triomphe and Meyerbeer’s Les Huguenots were also completed that year.) Schumann called this ballade “the most spirited and daring work of Chopin” and reported that it was inspired by Mickiewicz’s Konrad Valenrod, a poetic epic concerning the battles between the pagan Lithuanians and the Christian Knights of the Teutonic Order. The work exhibits both the ingenious conflation of sectional, sonata, and rondo forms and voluptuous, wide-ranging harmonic palette that mark all of the ballades.

Sonata No. 2 in B-flat Minor, Op. 35

Early in 1837, Chopin fell victim to the influenza epidemic sweeping Paris. He spent several miserable weeks in bed with a high fever and a bloody cough, and his spirits

were further dampened by a letter from Countess Teresa Wodzińska, on whose daughter Maria he had long had marital designs. Chopin was further unsettled that spring by insistent pleas from George Sand, whom he had first met at a party given by Franz Liszt a few months before, to visit her at Nohant. He agreed, then reneged, and finally decided to accompany the pianist,

CSO.ORG 3 COMMENTS

COMPOSED 1837–39

publisher, and sometime composer Camille Pleyel on a business trip to London. Chopin enjoyed taking in the sites around southern England, and he created a sensation at a reception sponsored by the piano maker Broadwood but found England gloomy and a bit too well-ordered for his taste. By July, he was back in Paris, where he received a letter from Countess Wodzińska confirming that she and Maria would not be seeing him that year; his hopes of marrying the girl vanished. Emotionally emptied by this turn of events but not yet ready to let George Sand into his life, Chopin found solace in composing, and in November, he wrote a stark marche funèbre (funeral march) that may have embodied not just his shattered marriage hopes but also his continuing distress over the failed uprising against occupying imperial Russia that had erupted in Warsaw seven years before.

Two years later, the funeral march served as the catalyst, third movement, and expressive heart of the B-flat minor sonata that he composed at Nohant, George Sand’s villa near Châteauroux in the province of Berry. The sonata’s four movements circumscribe an enormous variety of moods and techniques—Chopin was accused by no less an authority than Robert Schumann of here “binding together four of his most unruly children.” Subsequent analysis, however, refuted Schumann’s view by showing that the same motific, harmonic, and coloristic balances and relations that characterize the best of

Chopin’s one-movement works also operate here. Polish musicologist Józef Chomiński concluded that Chopin’s intent in the sonata was less to create a tightly knit nineteenth-century realization of the classical form than to have it serve as a synthesis-in-four-movements of his earlier achievements as a keyboard composer: the opening movement, after a tiny introductory gesture, fills its sonata form with a main theme built from a leaping motif and a grand subsidiary melody that would not have been out of place in a ballade; the scherzo, related in its periodic structure to Chopin’s dance pieces and in its style and structure to his scherzos, uses as its central portion a dreamy song in the manner of a nocturne; the funeral march, indebted in mood and technique to the slow movement of Beethoven’s Eroica Symphony, also enfolds a delicate nocturne-like cantilena in its central section; and the finale, written entirely in octaves with not a single chordal harmony until the very last measure, resembles the etudes and preludes in its epigrammatic brevity and uncontrasted motific material.

The composer’s biographer Herbert Weinstock assessed that the B-flat minor sonata is “one of the perfect formal achievements of music. So, and because it is no easy trifle but a massive and enormously varied work, I believe that by itself, had Chopin written little else, it would entitle him to a position as peer of the greatest artistic creators.”

4 COMMENTS

BRETT DEAN

Born October 23, 1961; Brisbane, Australia

Faustian Pact (Hommage à Liszt)

COMPOSED 2023

Composer, violist, and conductor Brett Dean, one of Australia’s most acclaimed musicians, studied at the Queensland Conservatorium before moving to Germany in 1984 to become a violist in the Berlin Philharmonic. After serving in that distinguished ensemble for sixteen years and beginning to compose in 1988, Dean returned to Australia in 1990 to work as a freelance musician. He established his reputation as a composer when his clarinet concerto, Ariel’s Music, won the UNESCO International Rostrum of Composers Award in 1995. His awards include the Paul Lowin Orchestral Prize from the Australian Music Centre, Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center’s Elise L. Stoeger Prize, Grawemeyer Award from the University of Louisville for his violin concerto The Lost Art of Letter Writing, Australian National Music Award, and an honorary doctorate from Griffith University in Brisbane. Brett Dean has written extensively for orchestra with and without soloists (he has performed his 2005 viola concerto on four continents), chamber ensembles, chorus, solo

voice, film, and radio. His debut opera, Bliss, based on a novel by two-time Booker Prize–winner Peter Carey, was critically acclaimed at its premiere in Sydney in 2010 and has since been staged in Melbourne, Edinburgh, and Hamburg. His Hamlet, with a libretto by Matthew Jocelyn, was premiered at Glyndebourne Festival Opera in June 2017 and has since been produced at the Metropolitan Opera in May 2022 and at the Bavarian State Opera in Munich the following season.

Dean wrote of Faustian Pact (Hommage à Liszt), composed for Benjamin Grosvenor,

I began my series of Homage Etudes for solo piano in 2009 as a means of exploring aspects of keyboard writing through the ages, choosing piano works from an array of different composers as the starting point for each one. They are, therefore, homages to individual styles, eras, and approaches in writing for the piano. At the same time, they are etudes, not only for the pianist who takes them on but also for me as a composer, trying on different hats as I study varying stages of keyboard technique and

CSO.ORG 5 COMMENTS

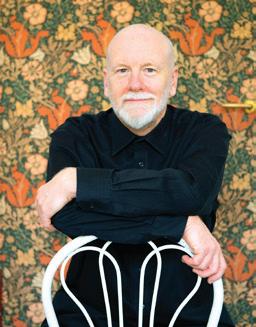

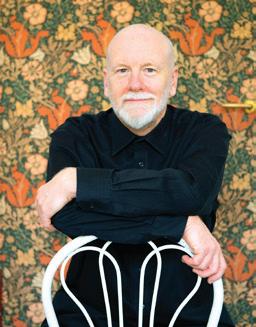

above: Brett Dean, photo by Bettina Stoess

its development from Bach through to Kurtág (so far!).

My most recent addition to this collection is Faustian Pact, an homage to that most mercurial of pianist-composers, Franz Liszt. Not possessing the pianistic “chops” myself to come to grips with his extraordinary piano pieces firsthand, he has remained for me something of a mystery for too much of my life. Through my years as an orchestral musician, encounters with his music were largely limited to warhorses such as his piano concertos and Les préludes. (The Faust Symphony certainly grabbed my attention, however!) Spending time more recently studying works such as the Transcendental Etudes

FRANZ LISZT

and hearing the wonderful dedicatee and instigator of this new work of mine, Benjamin Grosvenor, performing Liszt’s extraordinary B minor sonata, has been an eye-, ear- and mind-opening experience.

My Faustian Pact pays homage to this marvelously inventive mind in a brief musical argument that touches on Liszt’s harmonic quirkiness and originality, as well as his daringly phosphorescent pianism and surprising moments of mystical reflection.

Faustian Pact (Hommage à Liszt) is a co-commission between Symphony Center Presents, Wigmore Hall, and “Le Piano Symphonique” Lucerne Symphony Piano Festival 2024.

Born October 22, 1811; Doborján, Hungary (now Raiding, Austria)

Died July 31, 1886; Bayreuth, Germany

Sonata in B Minor

COMPOSED 1852–53

By 1848 Liszt had made his fortune, secured his fame, and decided that he had been touring long enough, so he gave up performing,

appearing in public during the last four decades of his life only for an occasional benefit concert. Amid the variegated patchwork of duchies, kingdoms, and city-states that constituted preBismarck Germany, he chose to settle in the small but sophisticated city of Weimar, where Sebastian Bach held a job early in his career. Once installed

6 COMMENTS

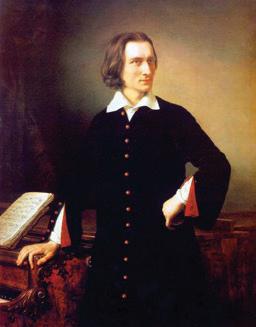

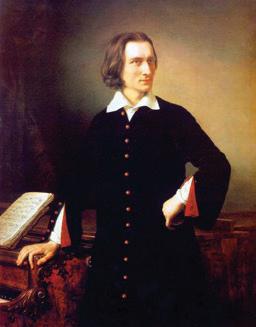

above: Franz Liszt, oil portrait by Miklós Barabás (1810–1898), 1847. Hungarian National Museum

at Weimar, Liszt took over the musical establishment there and elevated it into one of the most important centers of European artistic culture. He stirred up interest in such neglected composers as Schubert and encouraged such younger ones as Saint-Saëns, Wagner, and Grieg by performing their works. He also gave much of his energy to his own original compositions and created many of the pieces for which he is known today—the symphonies, piano concertos, symphonic poems, and choral works.

In 1852–53 Liszt composed his revolutionary B minor piano sonata. The procedure on which he built this sonata (as well as his Second Concerto and many of his orchestral tone poems) is called “thematic transformation,” or, to use the rather more jolly phrase of William Foster Apthorp, “The Life and Adventures of a Melody.” Never bothered that he was ignoring the classical models of form, Liszt concocted his own new structures around this transformation process. (“Music is never stationary,” he pronounced. “Successive forms and styles can only be like so many resting places—like tents pitched and taken down again on the road to the Ideal.”) Basically, the “thematic transformation” process consists of inventing a theme that can be used to create a wide variety of moods, tempos, harmonies, and rhythms to suggest whatever emotional states are required by the different sections of the piece—recognizably

the same at the core, but different on the surface for each “scene.”

There are at least four such scenes played continuously in Liszt’s Piano Sonata, which correspond roughly to “first movement,” “slow movement,” “finale,” and “coda.” The principal theme, presented after seven measures of slow introduction, comprises two motific components: a leaping exclamation followed by a dramatic triplet figure and an ominous quick-note gesture in the low register. It is from these two pregnant fragments that the magnificent and thoroughly integrated structure of this sonata is built. The only important melodic contrast is provided by a bold, striding theme introduced above repeated chords.

Of the B minor sonata, one of the grandest and most influential of all nineteenth-century keyboard compositions, Richard Wagner told Liszt, “It is beautiful beyond all expression—great, gracious, profound, noble, sublime like yourself. I have been moved to the depths of my being. Many thanks for this pleasure vouchsafed to me.” To which the American critic James Huneker added, “There is nothing more exciting in the literature of the piano.”

Richard E. Rodda, a former faculty member at Case Western Reserve University and the Cleveland Institute of Music, provides program notes for many American orchestras, concert series, and festivals.

CSO.ORG 7 COMMENTS

PROFILES

Benjamin Grosvenor Piano

British pianist

Benjamin Grosvenor is internationally recognized for his sonorous lyricism and understated brilliance at the keyboard. He is regarded as one of the most important pianists to emerge in several decades, with Gramophone recently acknowledging him as one of the top fifty pianists ever on record.

Concerto highlights in the 2023–24 season include his much-anticipated debuts with DSO Berlin and Iceland Symphony Orchestra. He also performs with the Gürzenich Orchestra Cologne, Scottish Chamber Orchestra, City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra and Hallé Orchestra (England), Washington National, Indianapolis, and Pittsburgh symphony orchestras.

A celebrated recitalist, this season Grosvenor makes his debut in the Lucerne Piano Festival, where his Liszt-inspired program features a world premiere of Brett Dean’s Faustian Pact (Hommage à Liszt). Later, he premiers the work in the United States and the United Kingdom. He also gives recitals at Konan Kumin Cultural Center Yokohama, Cologne Philharmonic, Théâtre des Champs-Elysées, Queen Elizabeth Hall, Klavier Festival Ruhr, Hong Kong City Hall, Darmstadt, Bridgewater Hall, and Sala Verdi, Milan.

Grosvenor tours Japan with violinist

Sayaka Shoji and Modigliani Quartet and makes his debut at Suntory Hall, Tokyo.

In 2011 he signed to Decca Classics, becoming the youngest British musician ever and the first British pianist in almost sixty years to sign to the label. His most recent release, Schumann and Brahms, was selected as Gramophone Editor’s Choice and Diapason d’Or. His 2020 album of Chopin’s piano concertos received both the Gramophone Concerto Award and a Diapason d’Or de L’Année, and his 2021 Liszt was awarded the Chocs de l’Année and Prix de Caecilia.

Grosvenor has received Gramophone’s Young Artist of the Year, a Classical Brit Critics’ Award, UK Critics’ Circle Award for Exceptional Young Talent, and a Diapason d’Or Jeune Talent Award. He has been featured in two BBC television documentaries, as well as in CNN’s Human to Hero series. In 2016 he became the inaugural recipient of the Ronnie and Lawrence Ackman Classical Piano Prize at the New York Philharmonic.

Following studies at the Royal Academy of Music, he graduated in 2012 with the Queen’s Commendation for Excellence and in 2016 was awarded a RAM Fellowship. Grosvenor is an ambassador for Music Masters, a charity dedicated to making music education accessible to all children regardless of their background, championing diversity and inclusion.

PHOTO BY ANDREJ GRILC