Sonata in C-sharp Minor, Op. Posth.

COMPOSED 1865

Ilya Petrovich

Tchaikovsky, a mining engineer by trade, was supervisor of the iron works at Votkinsk, an industrial town in Russia’s Ural Mountains, when his second son, Pyotr Ilyich, was born on May 7, 1840. The family had grown to include a total of six children by the time Ilya quit his job in Votkinsk to take a new position in Moscow in 1848. The promised work did not materialize there, however, and the Tchaikovskys moved on to St. Petersburg, where enough money was found to send Pyotr to a preparatory school. When Ilya secured work in a distant town north of Sverdlovsk, the boy was left alone at the school in St. Petersburg, miserable and greatly depressed. His spirits were not lifted a bit in 1850 when the family transferred him to the Imperial School of Jurisprudence to begin his training for a legal career. Two years later, the Tchaikovskys finally settled permanently in St. Petersburg, much to Pyotr’s delight, but his happiness was cut short by the death of his mother in 1854 from cholera, a traumatic event that spawned the residual melancholy that shadowed

him for the rest of his life. He graduated from the Jurisprudence School in 1859, when he was nineteen, and immediately found a clerical position with the Ministry of Justice, but his thoughts turned increasingly to music.

Though Pyotr’s musical activities to that time had been limited to singing in a choir as a youngster, taking some piano lessons, and seeing a few operas and ballets, they proved a sufficient stimulus for him to be drawn to composition, and he had produced a piano waltz and two songs by the time he left school. His father, who had by then been appointed to the estimable post of director of the Institute of Technology, encouraged him to follow his interest and study theory formally with Nikolai Zaremba, a member of the Russian Musical Society, the organization sponsored by Grand Duchess Elena to promote the musical culture of St. Petersburg. When the Society founded a conservatory in 1862 and appointed Zaremba to its faculty, Tchaikovsky continued his lessons there with him; the next year, the young musician quit his government job and enrolled full-time at the school. He showed sufficient talent to be taken under the tutelage of the conservatory’s director, the noted pianist and composer Anton Rubinstein,

who required of him the usual student exercises in counterpoint and composition firmly anchored to the precedents of Beethoven, Mendelssohn, and Schumann.

During his two-and-a-half years at the conservatory, Tchaikovsky studied piano, flute, organ, conducting, and composition and wrote a surprising amount of music in addition to the obligatory theoretical and contrapuntal exercises, most of it ordered by Rubinstein to fulfill the school’s curriculum: orchestrations of piano works by Beethoven, Weber, and Schumann; several small orchestral pieces as well as the tone poem The Storm and an overture in F; a number of piano works, including a set of variations and a sonata (published after his death as op. 80); numerous chamber compositions, most notably a movement of a string quartet that he reworked for piano in 1867 as the Scherzo à la russe, op. 1, no. 1; and a sketch (now lost) for a scene from Pushkin’s Boris Godunov from 1864, four years before Mussorgsky began his operatic version of the tale. He also wrote the orchestral Characteristic Dances that Johann Strauss, Jr., somehow obtained and performed in September 1865 at his popular concerts at the nearby summer resort of Pavlovsk; it was the first time Tchaikovsky’s music was heard outside the confines of the conservatory.

The Piano Sonata in C-sharp minor that Tchaikovsky composed during his final months at the St. Petersburg Conservatory in 1865 is the most ambitious work he undertook as a student—four movements, arranged according to the classical precedent and totaling nearly a half hour, that imposed some virtuosic technical demands. The circumstance of its composition is unknown, as is any attempt at performance or publication he might have made of it. In 1900, seven years after his death, the manuscript was found among his papers at the country house he maintained in his later years at Klin, fifty miles northwest of Moscow on the main train line to St. Petersburg (his preserved estate is now the principal Tchaikovsky museum and archive). Tchaikovsky’s brother Modeste brought the sonata to the attention of composer Sergei Taneyev, a student of Tchaikovsky and his successor as professor of composition at the Moscow Conservatory, and pianist and conductor Alexandr Ziloti (another pupil of Tchaikovsky), and they convinced Pyotr Jurgenson, Tchaikovsky’s regular publisher, to issue the score. Taneyev edited the complete work for Jurgenson, but Ziloti thought that only the first and third movements were worthy of publication and performed them on two recitals in Moscow in October 1900; Jurgenson published Taneyev’s edition (as oeuvre posthume) in 1900 (numbered as op. 80 in Tchaikovsky’s

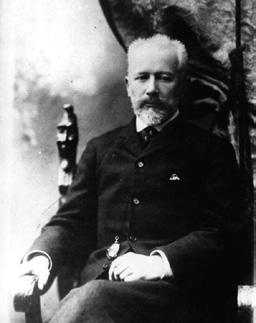

previous page: Pyotr Tchaikovsky, as photographed by Zakharin, 1865. Saint Petersburg, Russia | opposite page: Chopin, watercolor and ink drawing by fiancée Maria Wodzińska (1819–1896), 1836. National Museum, Warsaw, Poland

catalog) and Ziloti’s two-movement version the following year.

The early C-sharp minor sonata does not yet possess the technical polish or formal assurance that came to be consistent elements of Tchaikovsky’s later music, but it does show the melodic fluency, harmonic color, and expressive cogency that were already inherent in the twenty-year-old student composer’s writing. The opening movement is a textbook sonata form with a darkly colored main theme comprising a repeated-note cell and a lyrical complementary phrase with an arching second subject in a brighter key. The development section is largely concerned with the repeated-note cell before an almost literal recapitulation rounds out the movement. The style and spirit of the Andante echo Robert Schumann’s character pieces, with a slow, gentle melody whose two varied returns are separated

FRÉDÉRIC CHOPIN

by rhythmic episodes in the nature of a Polish mazurka. Tchaikovsky thought highly enough of the scherzo, the sonata’s most prophetic movement, which he borrowed for his Symphony no. 1, composed just a year later than the sonata but after he had graduated and assumed a faculty position at the Moscow Conservatory. For the symphony, Tchaikovsky replaced the sonata’s rather innocuous central trio with the first of his great waltzes for orchestra. The sonata-form finale is built from musical incongruities—a dramatically aggressive main theme countered, without a single gesture of transition, by a stream of fundamental block-chord harmonies. Both reappear in the development, with the block chords showing off some pedantic contrapuntal techniques that Tchaikovsky had acquired during his studies. Following a full recapitulation, the sonata comes to an abrupt close.

Born February 22, 1810; Żelazowa Wola, Poland

Died October 17, 1849; Paris, France

Selected Waltzes

COMPOSED 1829–47

The waltz was descended from the Austrian peasant ländler, an elegant, striding dance in moderate triple meter that gained great

popularity during Mozart’s last years in Vienna. (He wrote music for such German dances when they were first allowed to join the staid, traditional minuet in the imperial balls in 1788. Maria and Captain von Trapp fall in love dancing a ländler in The Sound of Music.) The Viennese went mad over the new dance and spent many nights

literally dancing until dawn. Franz Schubert (the only one of the leading Viennese classical masters actually born in that city) wrote some delightful parlor room specimens of the dance. It was during the 1830s and 1840s that the waltz established its form and style and became a European mania when Johann Strauss, Sr., led a crack orchestra in his own compositions, faster tempo, and more lilting modernizations of the ländler. So great was the popularity of the waltz during Strauss’s lifetime that, during at least one carnival season, the ballrooms of Vienna were made to accommodate 50,000 people in an evening—in a city with a population of 200,000!

Frédéric Chopin knew and admired the waltzes of Strauss, and he set about creating his own version of the genre especially suited to his soirées in the sophisticated salons of Warsaw and Paris. Chopin’s twenty waltzes (a dozen others may have been lost), composed throughout his life, were not intended for dancing (Robert Schumann allowed that they were so elegant that “well over half of the ladies would have to be at least countesses”), but were meant to capture the sweep and joie de vivre of the popular dance in concert versions. They were among the most popular of his works during his lifetime.

The waltzes in E major and E minor, composed respectively in 1829 (published posthumously in 1861) and 1830 (published posthumously in 1861 and 1868), bracket the time when Chopin was planning his departure from

Warsaw to seek his fortune as a piano virtuoso. The earlier E major waltz is a salon piece, pleasing in melody, uncomplicated in harmony, straightforward in its repeating-strain form, and modest in its technical requirements. It is with some justification that it was discovered after his death in a folder of scores he had not intended to publish. The E minor waltz, on the other hand, is a bravura work, announcing that Chopin was staking a place in European music for himself well beyond his hometown. The waltz’s harmony is original and expressive, its motifs carefully worked out, its command of textures and keyboard sonority skillful, and its technical requirements imposing.

The three waltzes of op. 70 were composed over a period of a dozen years and only gathered together by the Berlin firm of Schlesinger and issued six years after Chopin’s death. Waltz op. 70, no. 2 in F minor (1842) takes a wistful melody for its opening section and a widely arching theme for its second.

The three op. 64 waltzes were written in 1846–47 to fulfill a publishing contract that Chopin had recently entered into with the Leipzig firm of Breitkopf and Härtel; these waltzes, the op. 63 mazurkas and the op. 65 cello sonata were the last works that the composer published during his lifetime. The A-flat major waltz, op. 64, no. 3, inscribed to the Polish Countess Katarina Bronitska, achieves a near-perfect balance of playfulness and sophistication. The first of the three op. 64 waltzes (popularly known as the Minute Waltz, though for its small scale rather than for its

duration) was dedicated to Countess Delphine Potocka, one of the grandes dames of the Parisian salons and a lady of wealth and taste who also possessed a fine singing voice. She was one of Chopin’s earliest supporters after he arrived in the French capital, and the two may have been lovers for a brief time. Chopin inscribed his Concerto no. 2 in F minor of 1836 to the countess, and they remained close for the rest of the composer’s life. When she learned that Chopin was on his deathbed in 1849, she rushed back from Italy to comfort him with her songs during his last hours.

SAMUEL BARBER

Each of the three waltzes of Chopin’s op. 34, published simultaneously in December 1838 by Breitkopf and Härtel in Leipzig and Schlesinger in Paris as Trois valses brillantes, was dedicated to a different wealthy society lady. The melancholy waltz in A minor, op. 34, no. 2, which Chopin claimed to be his own favorite among his waltzes, dates from 1831, the year he settled in Paris. The piece was dedicated to Baroness d’Ivry, one of his earliest aristocratic students in the city. The F major waltz, dedicated to Mlle d’Eichthal, another of his Parisian pupils, ruffles its elegant surface with some surprisingly adventurous harmonic piquancies.

Born March 9, 1910; West Chester, Pennsylvania Died January 23, 1981; New York City

Sonata in E-flat Minor, Op. 26

COMPOSED 1947–49

By the time Samuel Barber was mustered out of the armed forces in 1945, his reputation as one of America’s most gifted composers had been established with such works as the Overture to The School for Scandal, Adagio for Strings, Violin Concerto, essays nos. 1 and 2 for orchestra, and

Capricorn Concerto. It was, therefore, appropriate that in 1947, he received a commission, funded by Richard Rodgers and Irving Berlin, to write a piano sonata in celebration of the twentyfifth anniversary of the League of Composers. Vladimir Horowitz, then at the height of his career, was engaged for the premiere, and Barber began composing the piece in the fall of 1947. The first movement was completed quickly, by early December, but further progress was slowed by Barber’s whirlwind

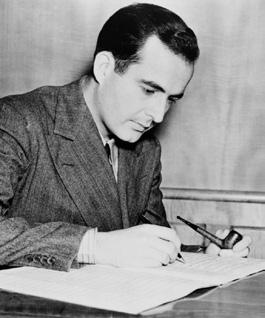

above: Samuel Barber, portrait. Getty Images, Bettmann/Contributor

schedule of attendance at performances of his increasingly popular works and by the composition of Knoxville: Summer of 1915 for the American soprano Eleanor Steber. Barber planned to work on the gestating sonata during his residency at the American Academy in Rome between February and July 1948 but found that the sunny climate and easy lifestyle of Italy unfocused his creative ambitions. “Perhaps it is well at times only to drift,” he wrote to his uncle, song composer Sidney Homer (whose wife was the internationally celebrated contralto Louise Homer), “and silence one’s New England conscience, which sees empty manuscript paper as a sign of eternal damnation!” He returned home from Italy ahead of schedule to carry on with the sonata and finished the second and third movements by August 1948. It was not until June 1949, however, that the titanic closing fugue was finally completed.

Horowitz gave the premiere of the sonata not in New York City, the headquarters of the League of Composers, but at a recital in Havana, Cuba, on December 9, 1949. A private hearing in the New York offices of G. Schirmer— Barber’s publisher, who was eager to issue the score—followed on January 4, 1950, and a public one took place in Constitution Hall in Washington (D.C.) on January 11 before Horowitz gave the long-anticipated League performance in New York on January 23. The sonata won immediate acclaim. Olin Downes wrote in the New York Times, “We consider it the first sonata really come of age by an American composer of this

period. It has intense feeling as well as constructive power and intellectual maturity.” Horowitz sent his own praise to Barber: “The sonata was a great experience for me. It was a national event, a landmark, an artistic outpouring of deep emotion.” Horowitz played the work twenty-one times within a year of its premiere and recorded it for RCA Victor in a performance that the composer pronounced “stunning.” The sonata has remained among Barber’s most highly respected and frequently heard compositions.

Barbara B. Heyman wrote in her study of the composer:

Barber’s Piano Sonata, though not revolutionary in its formal structure—it adheres to traditional designs for each movement—is a monumental masterpiece of its time. Its strength lies in the remarkable alliance between long sweeping melodic ideas that are distinctive to Barber’s musical imprint and the modern harmonic language and structural techniques that are idiomatic to the eclectic musical style of the twentieth century.

The bold first movement is intricately woven from a few pregnant motifs: an opening theme of dotted rhythms and half-step melodic motion, a broad strain given above an arching accompaniment, a nervous repeated-note figure, and a tender rising phrase grown from the dotted rhythms of the beginning. The second movement is an evanescent, dance-like essay

that serves as a scherzo. The Adagio, into which Barber introduced serial procedures, is not only among his most stylistically daring creations but also one of his most profoundly moving. The closing fugue, a modern revival of the old Bachian genre, stirred the composer Francis Poulenc to write,

PYOTR TCHAIKOVSKY

The sonata pleases me without reserve. It is a remarkable work from both the musical and instrumental points of view. In turn, tragical, joyous, and songful, it ends up with a fantastically difficult-to-play fugue. This is a long way from a sad and scholastic fugue. Bursting with energy, this fugue knocks you out.

Concert Suite from The Sleeping Beauty (Arranged by Mikhail Pletnev)

COMPOSED 1888–89

By 1888, Tchaikovsky had become the most famous composer in Russian history. At the beginning of the year, he undertook his first international conducting tour, performing in Berlin, Hamburg, Prague, Paris, and London and meeting Brahms, Grieg, Dvořák, and Gounod during his stops. In May, after he returned home, he was asked by Ivan Vsevolozhsky, director of the imperial theaters in St. Petersburg and long an admirer of his music, to compose a ballet on the fairy tale of “The Sleeping Beauty.” (Tchaikovsky had refused a similar request from Vsevolozhsky

two years earlier. The proposed topic then was the mythical water nymph Undine, the same one on which the composer had unsuccessfully tried to build an opera in 1869.) Vsevolozhsky had assembled the scenario for the new ballet himself from the old French story La belle au bois dormant by Charles Perrault (1628–1703), whose 1697

from top: Pyotr Tchaikovsky, photographed by Franciszek de Mezer (1830–1922), Kyiv, 1890 | Photograph of the original cast of The Sleeping Beauty. Mariinsky Theatre, St. Petersburg, Russia, 1890. Carlotta Brianza (1867–1935), standing, third from left, starred as Aurora.

collection, Contes de ma Mère l’Oye (The Tales of Mother Goose) gave classic form to “Cinderella,” “Puss in Boots,” “Bluebeard,” “Little Red Riding Hood,” and many other traditional narratives. Tchaikovsky was occupied with the composition of the Fifth Symphony during that summer, but in August, he replied to Vsevolozhsky, “I have managed to look through the scenario and want to let you know immediately that I am enchanted by it, delighted beyond all description. It suits me perfectly, and I ask for nothing more than to be able to write music for this scenario.”

Vsevolozhsky mounted a sumptuous production for the premiere of The Sleeping Beauty, choreographed by Marius Petipa, and Czar Alexander III and his court attended a special “dress rehearsal” on January 14, 1890. The czar received the composer after the performance “with distant hauteur,” Tchaikovsky recorded in his diary.

“ ‘Very nice,’ the czar said.” The ballet’s early performances were greeted by audiences with a coolness no doubt influenced by Alexander’s critique, but The Sleeping Beauty soon won over its listeners and became a fixture of the Russian and international dance repertoire. A year later, Tchaikovsky, Vsevolozhsky, and Petipa collaborated on another fantasy ballet, The Nutcracker

The piano arrangement of excerpts from The Sleeping Beauty is by Mikhail Pletnev (b. 1957), who began his career by winning the gold medal at the 1978 International Tchaikovsky Piano Competition at the age of twenty-one.

Richard E. Rodda, a former faculty member at Case Western Reserve University and the Cleveland Institute of Music, provides program notes for many American orchestras, concert series, and festivals.

SYMPHONY

CENTER PRESENTS

Jeff Alexander Chicago Symphony Orchestra Association President

Cristina Rocca Vice President for Artistic Administration

The Richard and Mary L. Gray Chair

James M. Fahey Senior Director, Programming, Symphony Center Presents

Lena Breitkreuz Artist Manager, Symphony Center Presents

Michael Lavin Assistant Director, Operations, Symphony Center Presents & Rental Events

Joseph Sherman Production Manager, Symphony Center Presents & Rental Events

The Chicago Symphony Orchestra Artist-inResidence position, held by Daniil Trifonov, is made possible through a generous gift from James and Brenda Grusecki.