SIMON RAY

INDIAN & ISLAMIC WORKS OF ART

1 NOVEMBER 2023 TO 30 NOVEMBER 2023

BY APPOINTMENT

BY APPOINTMENT

It is with great pleasure that I present this twenty-third catalogue of Simon Ray Indian & Islamic Works of Art.

I would like to thank the scholars and experts who have so kindly and generously helped us prepare this catalogue: Andrew Topsfield, Jennifer Scarce and Will Kwiatkowski.

Leng Tan has written the catalogue descriptions for the paintings and works of art. Leng’s poetic writing expresses the essence of each work of art.

William Edwards has written the catalogue descriptions for a fascinating group of tiles with meticulous research and great enthusiasm. William’s passion for ceramics of the Islamic world are beautifully conveyed in his writing.

I would like to thank the following for their expertise in the installation and display of the works of art: Colin Bowles, Kevin Leathem, Louise Macann, Helen Loveday and Tim Blake.

Finally, I would like to thank Richard Valencia for his excellent photography; Richard Harris for his outstanding repro and colour preparation and his scanning of the paintings; and Peter Keenan for his fresh and inspired catalogue design that presents so exquisitely these works of art.

Simon Ray

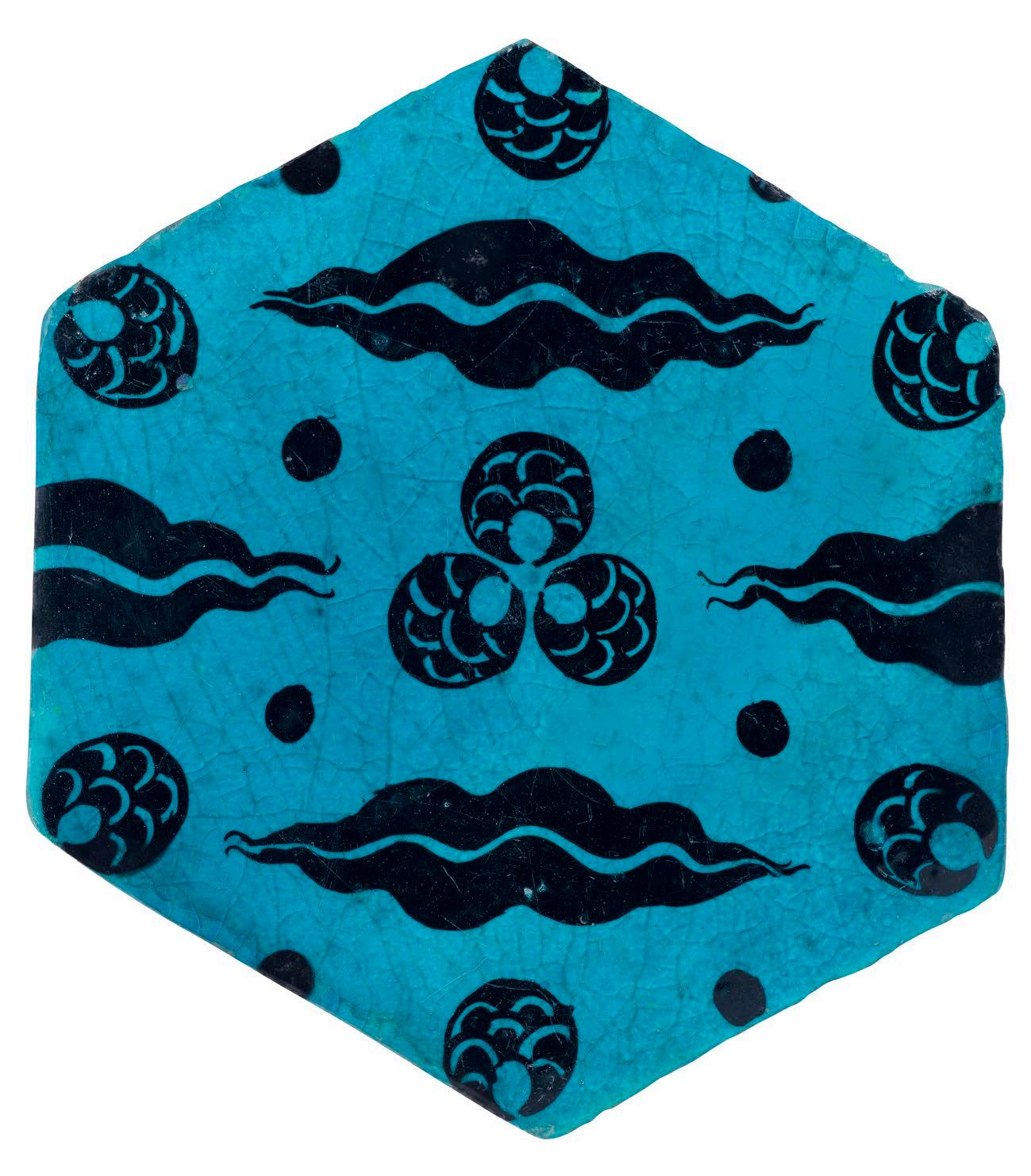

OttOman Syria, late 16th century

height: 29 cm

Width: 29 cm

A magnificent large hexagonal tile, underglaze-painted in a vibrant turquoise hue and jet black under a crackled glaze with an asymmetrical design of cintamani balls and tiger stripes.

The focal point is arguably the three large cintamani spheres grouped together to the centre of the tile. Painted in black, they each contain within hemispherical turquoise patterns which surround a further turquoise sphere to the inner edge. Framing the central cintamani above and below are two complete pairs of horizontal tiger stripes, again painted in a strong black hue. Each cusped stripe is bifurcated by a single wavy turquoise line, centrally placed and echoing the same contours of the edges. Placed to either side of the cintamani group are a pair of solid black spots with further examples

above and below to the tile’s edges, where we can find additional tiger stripes and cintamani

The popular Ottoman motif of cintamani (the Sanskrit word for a precious jewel) and “tiger stripes” or “Buddha lips” possibly originates from China in Buddhist times, where the three balls and wavy lines represented pearls borne on the waves of the sea, auspicious symbols associated with good luck and power. The three dots subsequently acquired royal connotations and were used by Timur on his coins. Another suggestion is that the stripes and spots represented the pelts of tigers and leopards, adapted by the Ottomans. The legendary Iranian hero, Rustam was often portrayed wearing a tiger skin coat and by about 1500 the design became increasingly popular in decorative arts, particularly prolific on ceramics and textiles.

According to the Victoria and Albert Museum, tiles of this Central Asian design were used in the decoration of various private apartments in the Topkapi Saray in Istanbul, including

those known as the Hirka-i Saadet and the library of Ahmed I.

Other examples of this rare design can be seen in the Brooklyn Museum, New York (86.227.194); the Louvre Museum, Paris (MAO 311c); the Museum of Islamic Art, Doha (TI.59.1998); the David Collection, Copenhagen (28/1962); the Victoria and Albert Museum, London (908 to F-1894 and 894-1897); the Sadberk Hanim Museum, Istanbul; and the British Museum, London (Museum number: OA+.10676). An example of a similar tile in a different palette is published in Yanni Petsopoulos, Tulips, Arabesques and Turbans, 1982, no. 107.

Provenance:

Anthony Powell (1935-2021) the Oscar winning costume designer

References:

Kjeld von Folsach, Art from the World of Islam in The David Collection, 2001, p. 193, no. 280.

Yanni Petsopoulos, Tulips, Arabesques and Turbans, 1982, no. 107.

Venetia Porter, Islamic Tiles, 1995, p. 118, no. 109.

turkey (iznik), circa 1580

height: 21 cm

Width: 24.8 cm

An underglaze-painted calligraphic tile with two stylised flowers appearing in the background, inscribed in elegant white thuluth script reserved against a vibrant cobalt blue ground, with emerald green and sealing wax red details.

The dark cobalt blue has been thickly applied and the artist’s brushstrokes can be clearly seen as the crisp white calligraphy punctuates the ground. Part of a stylised rosette flower with white petals surrounding smaller emerald inner petals and a central bud with raised sealing wax red detail can be seen to the bottom edge. To the top of the tile, a further stylised spray emerges from a horizontal section of script, the flower painted with five white petals containing a central red bud and further smaller red splashes. A single emerald green leaf appears from above the flowers whilst below, the white stem and a further leaf rises from the text.

The tile originally would have formed part of a calligraphic frieze. The inscription is a fragment of a verse in Ottoman Turkish; a suggested reading is:

“…under its roof, this sphere(?)…”

The references to the roof and sphere are entirely suitable for an architectural inscription.

A complete panel of similar calligraphic tiles including the border can be seen in situ in the Atik Valide Mosque in Istanbul and a further example is published in Hülya Bilgi, Dance of Fire: Iznik Tiles and Ceramics in the Sadberk Hanim Museum and Ömer M. Koç Collections, 2009, pp. 192-193, cat. no. 97. For a calligraphic panel with similar stylised floral motifs,see Ahmet Ertuğ and Walter Denny, Gardens of Paradise: 16th Century Turkish Ceramic Tile Decoration, 1998, p. 94.

Provenance:

Mrs Zeïneb Lévy-Despas

Collection Zeïneb et Jean-Pierre Marcie-Rivière

Acknowledgement: We would like to thank Will Kwiatkowski for his expert advice and kind reading of the inscription.

turkey (iznik), circa 1575

height: 25 cm

Width: 25 cm

A polychrome tile painted in dark cobalt, turquoise and sealing wax red in low relief against a fresh, vibrant white ground. To the upper centre of the elegant design is a cusped medallion outlined with borders of sealing wax red and white filled with bold arabesques of interlacing trefoil medallion palmettes and split-leaf palmettes in white, outlined in black against a turquoise ground. Stylised flower petals and buds recalling little cintamani balls in blue and red that float against the arabesques embellish the palmettes. A delicate cluster of three flower buds composed in the manner of cintamani balls or “flaming triple pearls”, decorates the lower tip of

the cusped medallion while a single bud decorates the cusped medallion to either side. To the lower right and left edges of the tile are half cusped medallions of similar design.

The three cusped medallions float against scrolling vines in dark cobalt blue from which grow stylised lotus flowers, each with blue petals and red centres embellished with a delicate turquoise flower to the base of the flower. From the vines also sprout serrated saz leaves and four composite rosettes to the upper and lower edges. Both the arabesques within the cusped medallions and the scrolling vines have a wonderful rhythm and sense of movement that

enliven the graceful formality of the design. This tile is very unusual in that not only the sealing wax red is in relief, but the black outlines of the palmettes and split-leaf palmettes, and the cobalt blue of the scrolling vines and lotus petals, are also in relief.

The strong vibrant colours, including the lovely turquoise and the rich red also known as Armenian bole, and the crisp white ground under an impeccable glaze, are characteristic of the best period of Iznik production.

Provenance:

Spink and Son, London, 2001

Literature:

John Carswell, Iznik Pottery, 1998.

Gonul Öney and Banri Namikawa, Turkish

Ceramic Tile Art, 1975.

Venetia Porter, Islamic Tiles, 1995.

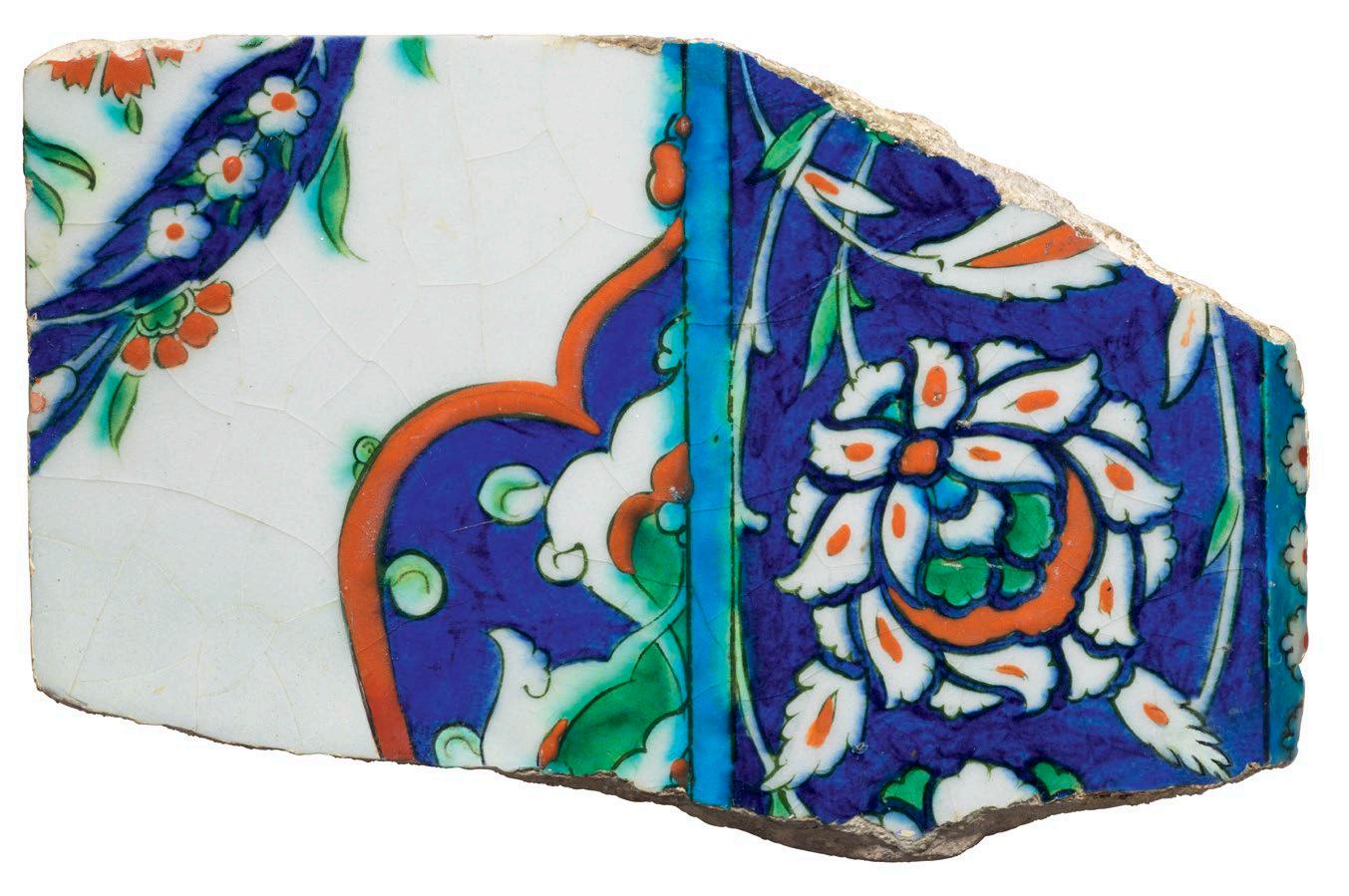

turkey (iznik), circa 1575

height: 15 cm

Width: 23.5 cm

An unusual polychrome underglazepainted border tile fragment in colours of cobalt blue, sealing wax red, turquoise and emerald green against a white slip ground, with a design of a composite rosette separated from a cusped palmette and saz leaf by a thin turquoise border.

To the left side of the tile, painted against a white ground, is part of a large cobalt saz leaf with inner stylised rosette sprays. Emerald

leaves and further flowers appear from the serrated edges. A cusped cartouche with a raised sealing wax red border contains a cobalt ground with white split-leaf palmettes and emerald details. A vertical turquoise border separates this design from the right side, where a cobalt ground frames a white composite lotus spray with further scrolling vines and leaves surrounding it. To the right edge is a chamfered turquoise border with white cusped lappets.

Provenance:

Heinrich Jacoby (1889-1964), president of the Persische Teppich Aktien Gesellschaft (PETAG), thence by descent until purchased by the current owner.

turkey (iznik), circa 1575

height: 24.5 cm

Width: 15 cm

depth: 4 cm

A polychrome underglaze-painted moulded tile fragment decorated in colours of cobalt blue, turquoise, emerald green and sealing wax red against a white slip ground.

The main field painted on a vibrant cobalt blue ground presents part of a composite rosette spray with cusped petals in colours of green, sealing wax red and white. Surrounding it are parts of split-leaf arabesque designs on a white ground edged in sealing wax red. A thick turquoise vertical border separates the main field from the moulded edge to the left. Here, a thick white vertical central stripe is framed by thin

sealing wax red borders to the left and right and then repeated cusped white lappets with raised red spots to the inner and outer edge.

This architectural fragment would have originally formed part of a border surrounding a doorway or a decorative niche, as the unusual moulded section provides clues as to its position and is highlighted by thin cobalt lines which echo its shape. For a similar tile with an identical pattern to the moulded edge, see Hülya Bilgi, Dance of Fire: Iznik Tiles and Ceramics in the Sadberk Hanim Museum and Ömer M. Koç Collections, 2009, p. 184, no. 90 and John Carswell et al., Iznik Ceramics at the Benaki Museum, 2023, p. 209, T47.

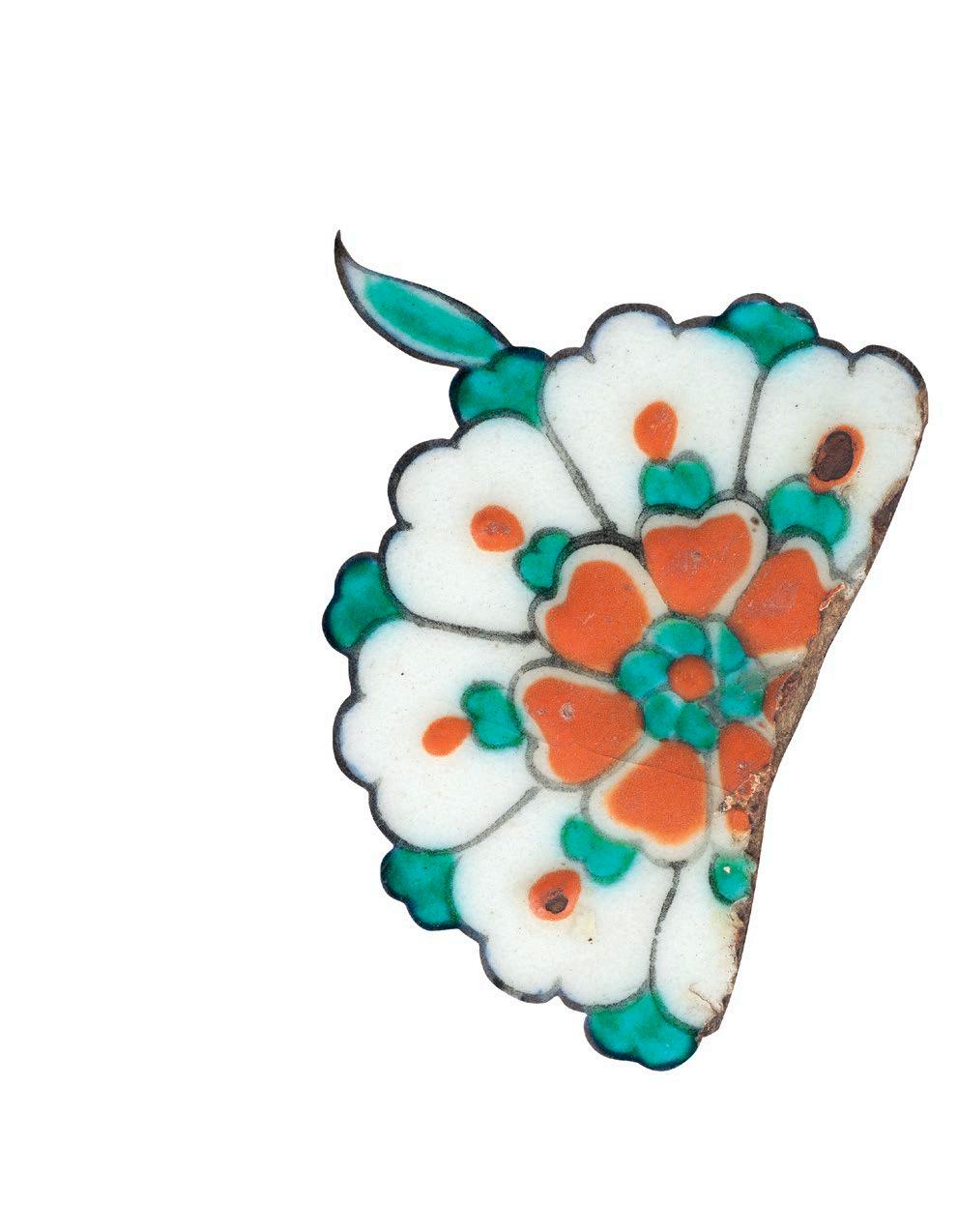

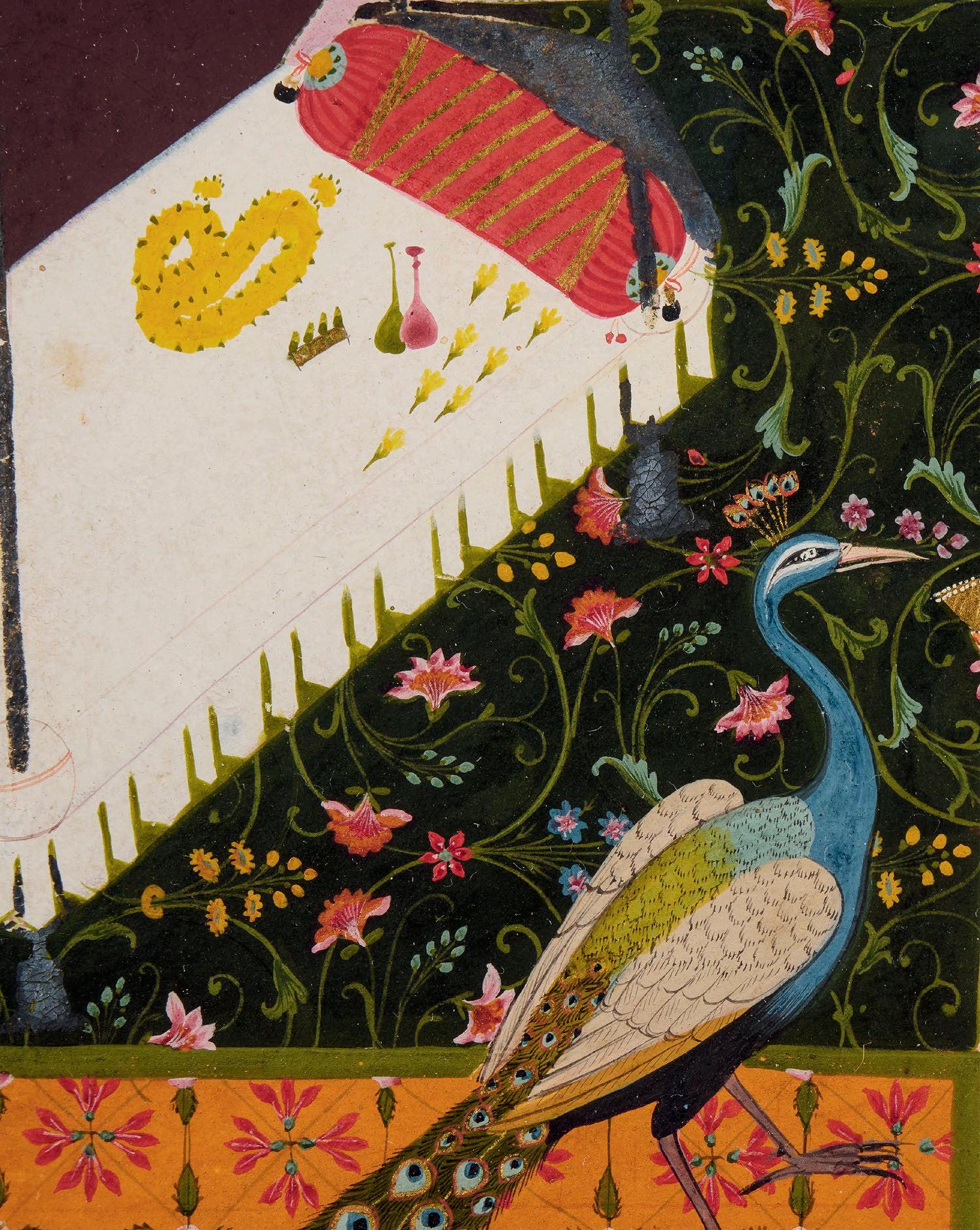

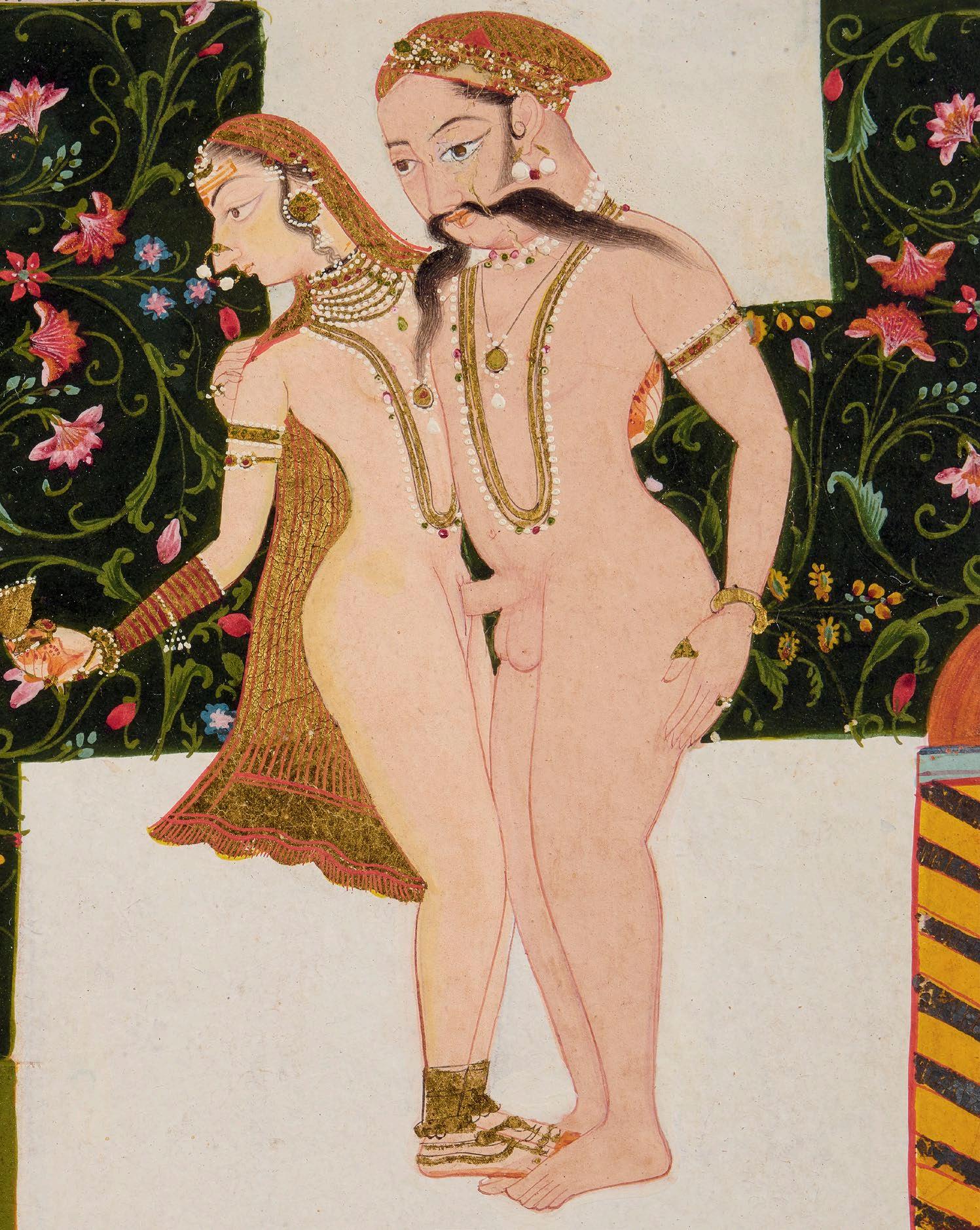

nOrthern india (mughal, prObably lahOre Or kaShmir), 17th century

height: 18 cm

Width: 16 cm

A tile in the cuerda seca technique with a design of composite flowers on multiple stems accompanied by long blade-like and short serrated leaves, rising from the widening trumpet mouth of a vase decorated with an arabesque of split-leaf palmettes. The central flower resembles a hyacinth superimposed with a small soft-petalled flower to the centre while the two lobe-petalled flowers to the upper right and left corners have small serrated flowers like daisies in the centre. Further flowers can be glimpsed to the top centre and on the sides. The flower petals have a distinctive white margin which is the white slip with which the earthenware body is covered before the application of other colours outlined by the manganese brown of the cuerda seca technique.

This tile relates closely in design, colours, technique and stylistic treatment of the flowers and leaves, including the distinctive white outline of the petals against the green ground, to a group of tiles in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London said to come from the tomb of the saint Shah

Madani at But Kadal, Zabidal, near Srinagar in Kashmir.

The group in the Victoria and Albert Museum was acquired from Mr Frederick H. Andrews in 1923. He had been living in Srinagar, where he was the Director of the Technical Institute of Kashmir, and wrote to the museum in 1922 offering to sell his collection before he left that year to return to the United Kingdom. He said that the tiles were part of the decoration of the Madani mosque and tomb but the Victoria and Albert Museum believe that though the tiles were installed in a Kashmiri monument, they were probably made in Lahore.

The tiles at the tomb of Shah Madani show similarities of design and colour to the present example. The tomb dates from the mid fifteenth century, but it was refurbished by a Mughal nobleman during the reign of Shah Jahan, when tiles in the cuerda seca technique were installed.1 A group of thirteen Mughal tiles from the tomb of Shah Madani, from the donation of

Jean et Krishnâ Riboud in the Musée Guimet, Paris, is published in Amina Okada, L’Inde des Princes: La donation Jean et Krishnâ Riboud, 2000, pp. 128-133.

A group of thirteen tiles from the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, also said to come from the tomb of Shah Madani, was exhibited and published in Robert Skelton et al., The Indian Heritage: Court Life and Arts under Mughal Rule, 1982, pp. 26-27, no. 5. Some of the tiles have designs closely related to the Riboud donation at the Guimet.

The use of the cuerda seca technique would also have been learnt from Safavid tile-makers. In this technique, the design is outlined on the fired tile with a manganese purple pigment mixed with a greasy substance, which separates the areas to be coloured. These are then painted with a brush and the tile is fired a second time. The greasy lines disappear, leaving a dark brownish outline separating the different colours. Cuerda seca, literally

meaning “dry cord” in Spanish, was developed during the latter part of the fourteenth century in Central Asia.

The cuerda seca technique (kashi) was brought to northern India from Iran. Robert Skelton has made the observation that “even in recent times, the makers of glazed tiles (kashigars) have been Muslims, whereas Hindu builders (sutradhars) have restricted themselves to working with unglazed terracotta.2 The use of a resist application between the colours gives distinct separation between them and a clarity of line which is particularly effective in architectural decoration. The tiles combine glaze techniques learnt from Persian craftsmen with a palette that is distinctly Indian in its warmth. It is likely that Lahore was one of the principal centres of the Mughal cuerda seca tile manufacture, but tiles in the cuerda seca technique may also have been made in Kashmir for the monuments constructed there.

Provenance: The Howard Hodgkin Collection

References:

1. See Robert Skelton et al., The Indian Heritage: Court Life and Arts under Mughal Rule, 1982, pp. 26-27, nos. 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10, for a discussion of Mughal tiles in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum.

2. Ibid.

nOrthern india (mughal, prObably lahOre Or kaShmir), 17th century

height: 19.5 cm

Width: 16.8 cm

A tile in the cuerda seca technique with a design of variegated leaves and composite flowers sprouting from interlacing vines and split-leaf palmettes against a green ground. From the lower left corner rises a large ochre split-leaf palmette edged with blue flanges, buds and fronds. To the bottom edge is a trefoil composite flower from the tip of which sprouts an ochre vine that boldly dissects the split-leaf palmette and divides the tile into four quarters. Curling in from the right edge to dangle its bifurcated petals above the trefoil flower is a stylised lily, the trajectory of its blue stem mirrored by the upward flourish of the stem above bearing a yellow leaf with a single vein. To the upper right corner is a composite lotus with serrated petals from which unfurls a bi-coloured stem that bifurcates as it grows to the left sprouting a yellow saz leaf on an ochre calyx and a flower with an ochre centre and yellow petals on a blue vine.

The design and colours on this tile are closely related to a group of thirteen Mughal tiles from the tomb of the saint Shah Madani at But Kadal, Zabidal, near Srinagar in Kashmir, now in the Musée Guimet, Paris.

These tiles form part of the donation of Jean et Krishnâ Riboud to the Musée Guimet; they are published in Amina Okada, L’Inde des Princes: La donation Jean et Krishnâ Riboud, 2000, pp. 128-133.

The present tile and those in the Riboud donation also relate closely in design, colours, technique and stylistic treatment of the flowers and leaves to a group of tiles in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, also said to come from the tomb of Shah Madani.

The tiles at the tomb of Shah Madani show similarities of design and colour to the present example. The tomb dates from the mid fifteenth century, but it was refurbished by a Mughal nobleman during the reign of Shah Jahan, when tiles in the cuerda seca technique were installed.1

Thirteen tiles from the Shah Madani at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London were exhibited and published in Robert Skelton et al., The Indian Heritage: Court Life and Arts under Mughal Rule, 1982, pp. 26-27, no. 5.

Provenance: The Howard Hodgkin Collection

Reference:

1. See Robert Skelton et al., The Indian Heritage: Court Life and Arts under Mughal Rule, 1982, pp. 26-27, nos. 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10, for a discussion of Mughal tiles in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum.

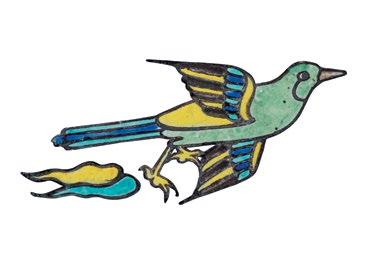

height: 118 cm

Width: 95.3 cm

depth: 2.2 cm

A rectangular panel of twenty tiles in the cuerda seca technique in shades of yellow, cobalt blue, sage green, ochre, turquoise and black against a lavender ground in the central field and white and lavender grounds in the framing border tiles. The panel depicts a charming scene of three figures picking apples in an orchard.

From the bottom of the panel, where a small group of coloured rocks lie, a magnificent turquoise apple tree grows upwards, filling the lavender ground around it. Its trunk is cusped to the base to suggest the gnarly lumps which tend to form in real life, and above it sprout branches of variegated size to either side. Rounded swirls indicate knots or burrs in the bark which create a suggestion of naturalism in what is otherwise a fantastical scene. Next to the rocks, on the left of the panel, apples are being collected by a kneeling male figure dressed in a vibrant yellow tunic, striped turban and turquoise belt. With his hand outstretched, he catches them joyously from above; his head tilted upwards, expectantly waiting for the next windfall. Framing him to the left are stylised floral sprays emanating from chinoiserie style scrolling rocks, all painted in vibrant hues.

To the right side of the tree, a standing courtier, resplendent in his sage green tunic, points with his right hand towards a lower branch as if advising the tree climber of where to find the next fruit to pick. The climber, perched precariously towards the top of the tree looks down intently at his friend below. He wears a dappled brown coat and sage green leggings and sports a multi-coloured turban. His right hand grabs a thick branch to help steady himself whilst he picks a large green apple with his left. The tree is

filled with bifurcated leaves painted in yellow and cobalt blue which compete for our attention with the large green fruit they surround.

To the top of the main field are floating chinoiserie style cloud bands and three stylised birds in the sky. To each side of the tree are further floral sprays. A thin turquoise band separates this scene from a wide meandering floral border with cobalt blue five-petalled rosette sprays and split-leaf palmettes on an offwhite ground.

Some colours on various parts of the panel appear mottled, as can be seen on the brown tunic of the climber, as well as areas of sage green applied as clothing, rocks and apples. This is the result of an unusual technique that causes the glaze to pull apart when fired to create a sense of texture. The deliberate fracturing of the glaze may perhaps be due to a reaction between the oxides and the glaze. The lavender colour of the ground is also very unsual and rarely seen on Safavid tiles.

For tiles and panels using similar colours and techniques from the same period and artist, see the panel of two tiles in the Simon Ray Indian & Islamic Works of Art catalogue, 2004, pp. 34-35, cat. no. 13 depicting a “Courtier Seated Under a Tree”. These tiles are now in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. For a pair of tiles depicting a “Resting Sword and Quiver” and a single tile with an “Ibex and Fruit Tree”, see the Simon Ray Indian & Islamic Works of Art catalogue, 2005, pp. 52-55, cat. nos. 23 and 24.

Isfahan, the Safavid capital, and Na’in were the two main centres in which buildings were lavishly decorated with tilework panels such as ours.

The old tile-making tradition of composing repetitive geometrical or vegetal patterns was kept alive on mosques and madrasas, but an important innovation on secular buildings was a composition of square tiles individually painted as single elements of an outdoor scene with characters set in a garden landscape. These were placed in royal garden pavilions from the time of Shah CAbbas to that of Shah Sulayman.1

Depictions of orchards and gardens were important, with the portrayal of trees such as cypresses and willows as well as shrubs and birds possibly inspired by the poetry of Nizami and Saadi. These designs have been used on tiles but also Safavid fabrics and textiles. The use of trees is also inspired by the “promises of beautiful heavenly gardens” in the Qur’an and are a “symbol of God’s mercy and forgiveness”. In Persian literature, mysticism, and arts, gardens are a conduit to the innermost layers of thought and imagination and a sage interpretation of the Persian worldview. According to this worldview, nature is just one link in the great chain of being and traversing it is one stage in the journey toward knowledge. The implicit message in these designs is that trees, flowers, animals, and all creatures are but manifestations of the divine grace.

Provenance: Private French Collection

Reference:

1. http://www.metmuseum.org/art/ collection/search/444949?sortBy=Relevance &ft=safavid+tiles&offset=0& rpp=20&pos=4

iran (Safavid), 17th century

height: 23.3 cm

Width: 23 cm

A tile in the cuerda seca technique in colours of yellow, turquoise, black, green, cobalt blue, ochre and white, depicting a hunting scene within a floral landscape.

A large ibex, with vibrant turquoise coat, rich cobalt underbelly, curved black horns and black hooves has been pounced upon by an ochre-

coloured lion who has emerged unseen from the right side of the tile. He seemingly stands upon his hind legs to balance himself, as his powerful front paws dig into the haunch of the strickened ibex before him. Simultaneously, his wide open mouth clamps down into the fleshy back of his prey, forcing the ibex onto its knees as it struggles to free itself. A splash of turquoise decorates the belly of the lion, the long tail falling behind his stretched legs as he mounts the attack. This captured moment of a predator hunting its prey is presented within a

simple scene of stylised floral sprays scattered upon a strong yellow ground. There is a greater sense of movement and suspense present here than is commonly seen on Safavid tiles of the period, and as such is highly unusual.

For a similar Safavid panel featuring a lion attacking an ibex, please see the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, The Nasli M. Heeramaneck Collection, gift of Joan Palevsky (M.73.5.4). A tile of two seated ibexes can be seen in the Victoria and Albert Museum, accession number IS.1-1898.

iran (Safavid), 17th century

height: 21.8 cm

Width: 21.8 cm

A tile in the cuerda seca technique with a design of a duck or waterfowl in a glade of luxuriant leaves and flowers, painted in hues of turquoise, cobalt blue, yellow, brown, grey, manganese and two shades of green against a white ground.

The duck glances upward and to the right from the bottom of the tile, surveying the scene with an inquisitive air. It has a brown head, yellow cheeks and a flat turquoise bill. Offering shade above the duck is a magnificent spray of stylised flowers and green serrated leaves sprouting from dark manganese purple vines. The bold flowers have cobalt and yellow petals and turquoise calyxes.

To the lower left corner is an ornate coil of serrated turquoise vines enclosing bi-coloured green and yellow leaves against a cobalt blue ground. Elements of the natural landscape have been ordered into a decorative arabesque. Turquoise vines, green leaves and composite polychrome flowers tower above to continue the arabesque. The vibrant colours of the tile are further enhanced by the more unusual white ground. To the top and right are green and dark manganese borders indicating that this tile formed the corner of a pictorial composition.

iran (Safavid), 17th century

height: 22.5 cm

Width: 22.3 cm

A charming tile in the cuerda seca technique depicting the head and bust of a white horse in profile, entering the scene from the right and moving towards the left against a rich cobalt blue ground. The horse has a wispy mane, a large eye drawn with arched brow and glistening pupil, open wide and alert for the hunt, ears pricked up in anticipation of having to break into a gallop for the chase, dark flaring nostrils and an open mouth revealing a protuberant tongue. These elements combine to present to us a living breathing beast, snorting from the exertions of the chase.

The horse is adorned with a green ceremonial plume held by a cusped yellow clasp hanging from a turquoise collar. The bridle is indicated by a yellow noseband and white cheekpiece, and taut black reins encircle the plume, suggesting the guiding hand of a rider whom we cannot see. The lower half of the white horse is painted a plum colour. Laterally bi-coloured horses are often seen in Persian and Indian miniatures; the painted colours indicate that these are splendid horses from royal stables.

The rich caparisons of the horse suggest that it is part of a princely hunting expedition. To the left corner of the tile is a slate coloured quiver full of arrows and the green elbow of a hunter taking aim. The rock and shrub landscape traversed by the hunting party is indicated by the spray of polychrome leaves rising from a black and white rock formation to the bottom of the picture and the chinoiserie cloud bands to the upper left corner, which may also be read as mounds of lichen or moss such as those found on mountain slopes.

A related tile with a similarly bold design of a horse and plume was formerly in the Hagop Kevorkian Collection, New York. This also shows a white horse with a ceremonial plume entering from the right. The Kevorkian horse is not accompanied by a quiver full of arrows or the elbow of a hunter but it is even more richly caparisoned, the bridle festooned with rich ornaments, the browband, headstall and noseband all in piquant turquoise, connected by an ochre brown cheekpiece decorated with turquoise and yellow beads. The horse is fitted with a saddle and saddlecloth fit for a prince, leaving

no doubt that like our tile the Kevorkian tile was from a panel depicting a princely hunting scene.

What the prince might have looked like can be seen in a tile in the British Museum, London, where the prince wears a Safavid turban and a tunic fastened with floral buttons like the bridle fittings of the Kevorkian horse. His quiver is turquoise outlined with a trim of ochre. As he draws the string of his bow, his elbow projects in the manner of the elbow in the present horse tile. Thus the British Museum tile may have also come from a large hunting panel; or alternatively, he may be an archer from a battlescene, though this is less likely as princely pleasure pursuits were by far the preferred subject of these elegant tiles over the strife of war when used to decorate royal residences and garden pavilions. The British Museum tile is published in Venetia Porter, Islamic Tiles, 1995, pp. 78-79, no. 73. According to Porter, the tile came from a panel of picture tiles probably from a palace, and she notes how the archer’s pose and costume are comparable to contemporary Persian miniatures.

Provenance: Spink and Son, London

The Diana Newman Collection, London

Published and Exhibited: The Many Faces of Spink, November 1997, cat. no. 9.

iran (Safavid), 17th century

height: 22.4 cm

Width: 22.6 cm

A tile in the cuerda seca technique with a design of elegant iris sprays. To the top left corner is an iris flower with soft turquoise and yellow petals sprouting from a white stem and turquoise calyx. Growing from the same stem is a just-opening iris bud with three yellow petals and a green and turquoise calyx. To the right is a shorter stem with a closed bud.

There is a wonderful sense of growth as the eye is led upwards from the closed bud to the unfurling bud and finally to the glorious open iris.

To the upper right of the tile trails a small branch of white and yellow willow leaves. A single white leaf floats against the blue sky, suggesting a gentle breeze. Also seen billowing in the wind to the lower left corner, are the yellow petals of another iris flower.

Provenance: Sir

Harrison Birtwistle

iran (Safavid), late 17th/early 18th century

height: 15.5 cm

Width: 19.5 cm

depth: 3.6 cm

A tile in the cuerda seca technique painted in cobalt blue and yellow with part of an inscription in large, white thuluth against the blue ground. The elegant, cursive letters are deftly outlined by the thin borders of manganese, the dark outlines of the cuerda seca technique left behind after firing now skilfully incorporated as part of the design. The inscription dominates the tile, filling the space and highlighted by the vibrant cobalt blue of the main field. A bold horizontal yellow border underpins the composition.

The inscription reads:

al-falak al-atlas

“In the outermost sphere”

The term al-falak al-atlas refers to the outermost sphere of the cosmos in medieval Islamic cosmography and is encountered in philosophical and mystical works by writers such as Ibn CArabi and Ahmad Ghazali (see for example Mohamed Haj Yousef, Ibn CArabi, Time and Cosmology, 2008, p. 11; and Door Frank Griffel, Al-Ghazali’s Philosophical Theology, 2009, p. 137).

Provenance: Madame Krishnâ Riboud, Paris

Acknowledgement: We would like to thank Will Kwiatkowski for his reading of the calligraphy.

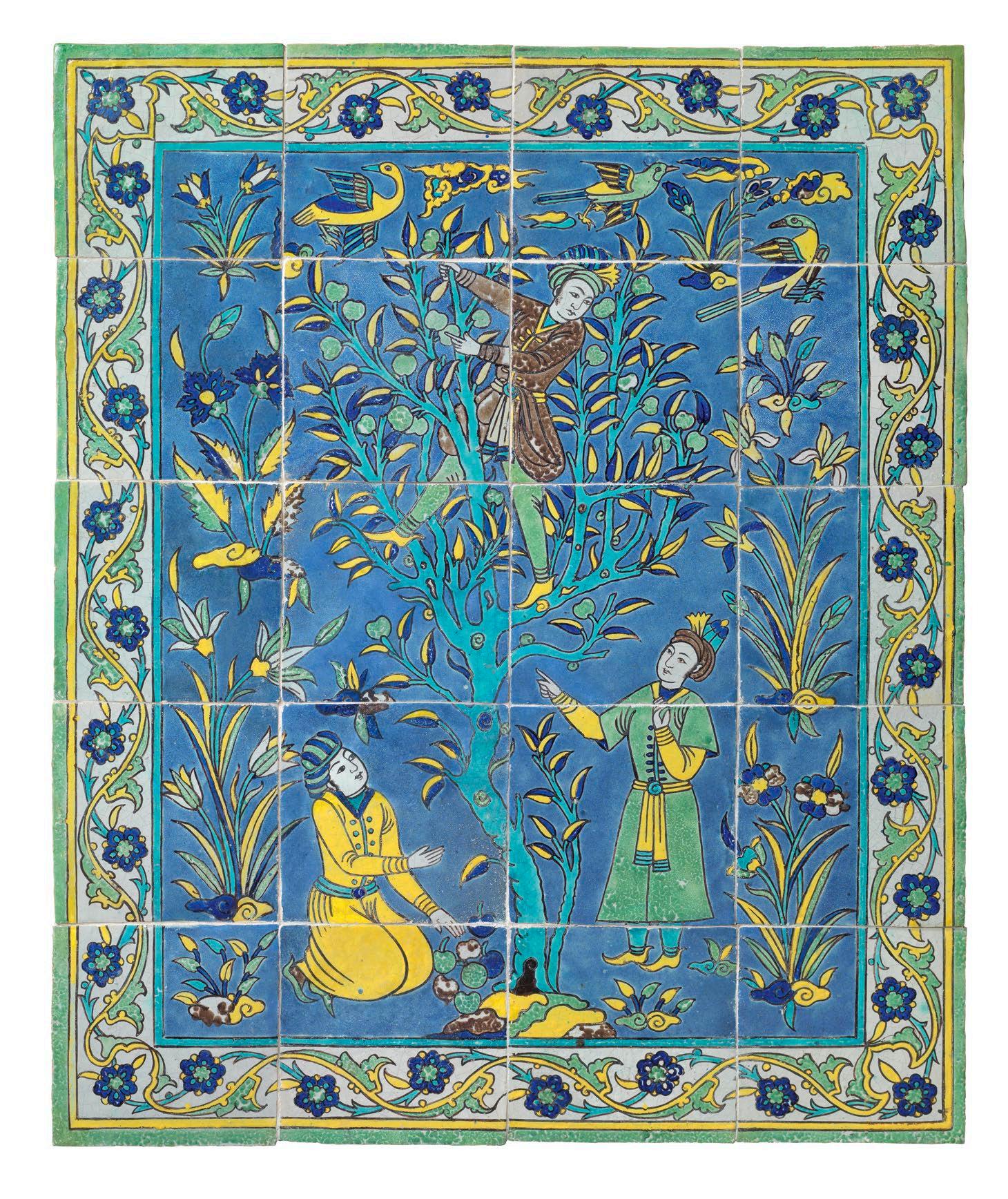

iran (Qajar, tehran), circa 1880

WOrkShOp Of Cali muhammad iSfahani

height: 90 cm

Width: 62 cm

A large and magnificent moulded polychrome tile, underglaze-painted in hues of cobalt blue, turquoise, yellow and manganese against a white slip ground and depicting an asymmetrical interior scene of a Safavid ruler and his guest, courtiers and musicians within floral borders.

The main field shows Shah CAbbas I (reigned 1587-1629) entertaining a deposed Uzbek prince, Vali Khan. The Shah is wearing a light manganese coloured tunic with stylised floral patterns, large round buttons to the front and tied at the waist with a striped sash. His wide eyes look straight out at the viewer, engaging us and drawing us into the scene. He sports a patterned turban on his head, and his left hand rests gently upon the hilt of his sword as he kneels upon a vibrant turquoise carpet full of boteh sprays. His back rests against a striped cobalt pillow and he holds a small wine cup in his right hand, as if proposing a toast to Vali Khan.

To the left of the Shah kneels the demure Uzbek prince, seated against a turquoise cushion. Dressed in a dark yellow tunic with large buttons to his front and tied at the waist with a large sash, he looks at Shah CAbbas with resignation but also sadness in his eyes. He has a wide thin moustache and wispy beard to his chin, his narrow face below a light manganese coloured qizilbash turban. His figure is slightly smaller than that of the Safavid ruler, again helping to convey the imbalance of power we see between the two men. His left hand mirrors the gesture of the Shah’s,

holding out a wine cup to celebrate perhaps an agreement of sorts. An interesting visual device is shown in the depiction of Vali Khan’s right arm. The long sleeve hides his right hand, the material dropping limply towards the floor. This directly copies the portrayal of Khan in the Chehel Sotun Palace painting as discussed below. A possible explanation is that the sleeve hides his deformed or non-existent hand, perhaps injured or removed in battle. The Safavids had two “permanent” enemies; the Ottomans to the West and the Uzbeks to the East so it was probably diplomatic of Shah CAbbas to receive Vali Muhammad Khan who could either be a useful ally or if all else failed could be traded as a hostage.

Framing the protagonists behind is a grand Safavid pavilion, with twisted columns and arched entrances. High brick walls frame it to either

side. We see three courtiers: one waving flags, one pouring wine into cups and one clasping his arms together. Further courtiers flank the group, all dressed in decorative tunics and facing inwards, waiting for a signal to approach. Just below the turquoise carpet, upon which the Shah and Uzbek prince sit, is a centrally placed curvaceous dancer, her hand in the air and balancing a cup on her head. She is surrounded by kneeling courtiers, one of whom looks to be smoking a long thin pipe. The rich cobalt ground framing the figures is scattered with fruit, wine cups, bottles, rosewater sprinklers and other items indicative of the party atmosphere presented before us. To the bottom of the tile we find a kamancheh player as well as a piper. Others serve or drink the wine being liberally consumed. Two women share a cup, gossiping quietly and a prostrate gentleman in a striped tunic is fed fruits directly into his mouth. Whilst not exactly debauched, the scene conveys an air of informality and intoxicated celebration. The continuous border containing the scene features meandering vines highlighted with stylised floral sprays and birds in flight.

The scene depicted is an interpretation of The Reception of Vali Muhammad Khan by Shah CAbbas I, painted on the northeast wall of the reception hall of the Chehel Sotun Palace in Isfahan in the 1660s. The Palace was completed in 1647 during the reign of CAbbas’s descendant the third Safavid Shah, CAbbas II (reigned 1642-1666). This event happened in the period of 1611-1612 where Vali went to Isfahan to take refuge and to seek help from Shah CAbbas against his enemies. As the chronicler Fazli Beg Khuzani relates, Shah CAbbas arranged a spectacular reception for his Uzbek guest. The main entrance to the palace was adorned

with velvet carpets and brocades, and good-looking youths were ordered to line up on both sides.

“No bearded person,” Fazli wrote, “was to remain in shops.” Moreover, the shah decreed that the rooms above the shops be allocated to the “city’s courtesans”. 1 Isfahan’s famed women of pleasure had close ties with the court as well, and this link was especially conspicuous during royal ceremonies such as depicted here, when the city’s courtesans were employed as part of the imperial panoply. This incident reflects the performative role courtesans played in Safavid Isfahan. A select number of the city’s courtesans also attended private courtly assemblies. As Fazli reports, Vali Muhammad Khan was invited, following his urban ceremony, to a nocturnal banquet

at the shah’s “private assembly hall” (khalvat-khāna-yi khās, literally “house of seclusion”), where courtesans who were referred to by their professional names - Lala, Gulpari, Kavuli, and Zarif - were also present.2 Later that day, Shah CAbbas, noticing Vali Muhammad Khan’s interest in Gulpari, decreed that the courtesan be in his company at all times.3 Another Safavid manuscript depicting a similar outdoor scene of officials from the court of Shah CAbbas entertaining a Uzbek envoy is now in the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, USA, accession number W.691.

A further example of a Qajar ceramic tile interpretating an earlier Safavid scene can be found in the house of the American artist Frederic E. Church (1826-1900) in Olana, New York State

on one of the fireplaces. Here there is a copy of a Safavid tile panel in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (03.9c). The Qajar painter-ceramist CAli Muhammad Isfahani, responsible for the Olana tile and another in the Victoria and Albert Museum (5121889), seems to have specialised in copying Safavid scenes. Our tile can therefore be linked to his workshop by its great finesse of execution and its particular iconography. Our tile, a copy of a known Safavid painting, along with its size and quality makes it incredibly unusual and therefore far rarer than the generic scenes more commonly found in other Qajar tiles.

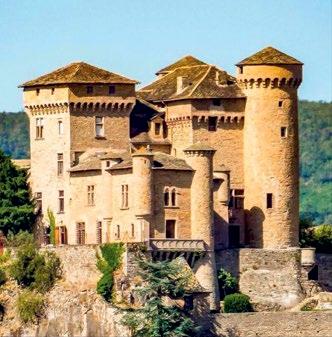

Provenance:

Emma Calvé (1858-1942), a French soprano who was the most famous female opera singer of the Belle Epoque. Our tile was hung in her home, the Château de Cabrières (Aguessac Aveyron).

Private French Collection, acquired in 1920 together with the Château and its contents. Private French Collection, acquired before 1962 by the current owners of the Château.

References:

1. Fazli Khuzani Isfahani, A Chronicle of the Reign of Shah CAbbas, 2015, p. 584.

2. Ibid., p. 586.

3. Ibid., p. 588.

Literature:

Sussan Babaie, “Shah CAbbas II, The Conquest of Qandahar, the Chihil Sotun, and Its Wall Paintings”, Muqarnas 11, 1991, pp. 125-142.

Robert D. McChesney, “Four Sources on Shah

CAbbas’s Building of Isfahan”, Muqarnas 5, 1988, pp. 103-134.

Mary Roberts, “Worlding on the Hudson: Frederic Church and Global Histories of Art”, Art History 45, 2022, pp. 518-544.

Jennifer M. Scarce, “Ali Mohammed Isfahani, Tilemaker of Tehran”, Oriental Art 22, Autumn 1976, pp. 278-288.

Acknowledgement:

We would like to thank Jennifer Scarce for her invaluable help with this description.

iran (Qajar), 1887-1888

attributed tO Cali muhammad iSfahani

height: 36 cm

Width: 35.5 cm

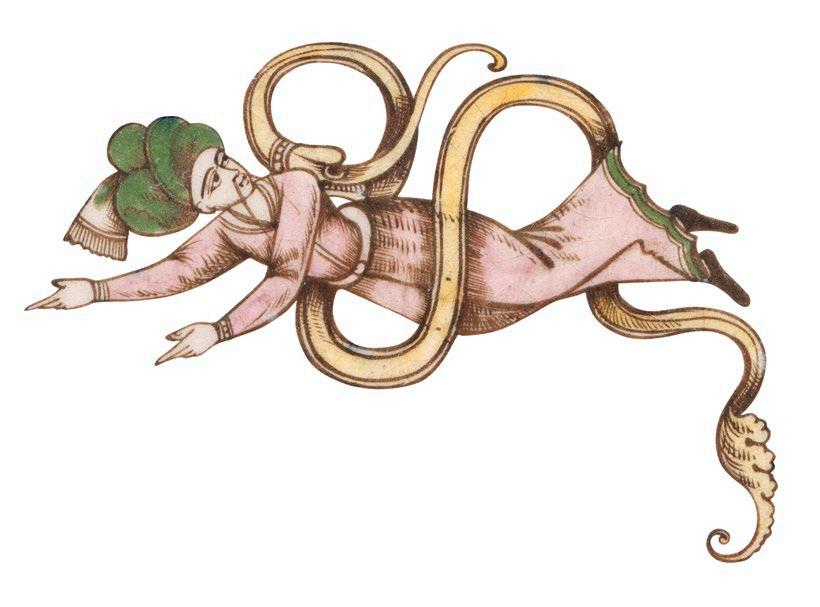

An octagonal polychrome underglaze-painted tile in colours of cobalt blue, yellow, green, pink and brown against a white ground depicting an unusual scene of caricatured mullahs within stylised floral borders.

The focal point of this tile is of course the three figures to the central field. To the top is a horizontal well-dressed gentleman wearing a pink tunic and sage green turban which suggests he could well be a mullah, a Muslim leader or cleric. His arms are stretched out and his head turned backwards as if he has seen something out of view. His face however maintains an air of calm. He almost floats against

the ground and above the figures below. A golden yellow mythical makara animal with a long snout, evil grin and cusped tail wraps itself around him, perhaps in protection or conversely entrapment.

Below are two kneeling zoomorphic figures clothed in cobalt blue tunics over white shirts. These fantastical creatures with the bodies of humans but with animal faces could suggest that the artist is mocking particular religious leaders. The larger figure to the left has the head of a makara, painted in a shade of brown and with a snout which extends and morphs into scrolling and cusped foliage. His arms have been almost comically extended, morphing into snake-like beasts with yellow makara heads looking to the right. His companion has bird-like features below a blue turban including a long and pointed beak which reveals prominent teeth. The remainder of the character is more human in composition, and he grasps in both hands a long yellow

tapering club. Both figures look to the left as if focussing on something out of view. The scene is painted against an off-white ground which is further decorated by small stylised floral sprays. The central field is framed by a large classic border of continuous scrolling pink trefoil florets alternating with foliage on a cobalt blue ground, contained between two narrow bands of foliate scrolls on a brown ground.

The tile relates stylistically and technically to the work of the celebrated Qajar potter CAli Muhammad Isfahani, who wrote a treatise on ceramic production and whose work has been published by Jennifer Scarce. About twenty known pieces of tile-work are attributed to him.1 Amongst his patrons was Major-General Sir Robert Murdoch Smith, who was in Iran between 1865 and 1888 as Director of the Persian Telegraphic Department. Murdoch Smith also collected works of art on behalf of institutions, in particular the South Kensington Museum, later to become the Victoria and Albert Museum.2 A panel of 57 tiles made by CAli Muhammad Isfahani in 18871888 and purchased by Murdoch Smith for £9 1s 9p is now at the museum (561:1-57.1888). The panel contains ten octagonal tiles similar to the present, with identical raised borders on a blue ground; a central narrative scene illustrating a verse from Persian literature; and the use of a distinctive pale buttery yellow.

References:

1. Venetia Porter, Islamic Tiles, 1995, p. 82.

2. Ibid.

Acknowledgement:

We would like to thank Jennifer Scarce for her invaluable help with this description.

nOrthern india (multan), circa 1800

height: 30.5 cm

Width: 32.5 cm

depth: 4.5 cm

An unusual red clay underglaze-painted and moulded square tile in hues of turquoise, yellow, green, red and cobalt blue on a white slip ground, under a transparent glaze and depicting a pair of raised threedimensional architectural columns against a crackled off-white ground.

The pair of identical columns are both segmented, with each section depicting a differing design of stylised floral sprays. The rectangular bases have diamond cartouches in cobalt and white, each containing a floral rosette with a yellow bud. The cartouches are set against a green ground and surrounded by further rosette sprays. Above, a large cusped field of scrolling split-leaf palmettes in white and yellow is reserved against a cobalt blue ground and framed above and below by thin turquoise borders. A narrowing field of white lappets against a rust red ground above gives way to a highly raised collar of cusped chevrons in white, turquoise and cobalt. To the top, a large field of vertical columns in turquoise and cobalt blue contain patterns of linked stylised white sprays with different coloured buds. Yellow and red lappet patterns frame the columns to top and bottom.

The unusual palette of this tile combined with its moulded form creates a rare spectacle. It would have been part of a larger panel of similar tiles decorating the wall of a palace or grand private residence. Comparable moulded tiles can be seen along the parapet of the mausoleum of the Sufi poet Shah Abdul Latif in Bhit Shah, Sindh, Pakistan, built by Ghulam Shah Kalhoro in the late eighteenth century and published in Abdul Hamid Akhund and Nasreen Askari, Tale of the Tile: The Ceramic Traditions of Pakistan, 2011, p. 110, fig. 177. According to Akhund and Askari, the architecture of this shrine is an amalgamation of both Sindh and Multan decorative styles (Abdul Hamid Akhund and Nasreen Askari, p. 111). The blue, turquoise, yellow, and apple green glazes used on the tiles on the dome and parapet of this mausoleum resemble those on this tile.

india (mughal), mid 17th century

height: 8 cm

Width: 26.5 cm

depth: 23.5 cm

The three components of this giltcopper (tombak) openwork betel box or container (pandan) with its fitted cover and matching tray form a harmonious ensemble where shape, technique and decoration work seamlessly together to create a courtly object that is so much more than the sum of its parts. The three metalwork pieces fit together with a satisfying click - the cover clips neatly over the ridge on the lip of the box, which in turn sits snugly in a shaped recess at the centre of the tray.

The elongated octagon is the mathematical principle for organising each of the three pieces and for integrating them into a whole. The tray has eight compartments, four long cartouches alternating with four short cartouches, each widening from the undecorated octagonal recess and curving up the shallow cavetto towards the raised

and protruding rim. The pierced arabesque decoration within the frame of each cartouche consists of a central six-petalled iris flower from which flow scrolling vines bearing serrated leaves and four-petalled flowers seen in profile. The intricately cast surfaces are engraved to further enrich the flowers and leaves with details of veins, buds and twisting tendrils. The edge of the tray is incised with lobed petal forms.

The pandan box is similarly of octagonal cross-section, with each of the sides pierced with stylised flowers and scrolling vines. The box tapers slightly as it rises to the close-fitting cover of gently raised, flattened dome form. At the centre of the lid is a four-petalled flowerhead within an eight-sided star created by the encircling vines from which the arabesques sprout in profusion. The sense of organic growth is controlled by the symmetry of the decoration and the geometric frames of the cartouches, as in a formal garden.

This exquisite pandan and tray is illustrated by Mark Zebrowski in Gold, Silver & Bronze from Mughal India,

1997, p. 277, pl. 476 and discussed on p. 278. Zebrowski describes the pandan as having Mughal rather than Deccani decoration:

“Returning to classical Mughal proportions, a gilt-copper openwork pandan with its matching tray has, instead of the quick and furious arabesque of the Deccan, the stately ornate flowers of Mughal India. In fact, the inspiration for each floral panel is architectural, recalling the pierced stone window screens (jalis) of Mughal palaces. The plants themselves have that slow and heavy grace of the period of Shah Jahan (1628-1658), when Hindu plasticity blended happily with Islamic and Italianate taste. The result is a delightful airiness like a jali window, permitting contact between the fresh pan leaves inside and the cooling breezes outside.”

Provenance:

Spink and Son, London, 3rd October 1996

Acquired by Ann and Gordon Getty from Spink and Son

Published:

Mark Zebrowski, Gold, Silver & Bronze from Mughal India, 1997, pp. 277 and 278, pl. 476.

nOrthern india (mughal Or deccan), early 18th century

height: 5.8 cm diameter: 11.2 cm

An enamelled silver-gilt pandan of circular form with a flat dome cover, decorated with floral motifs in cloisonné enamel in two shades of green and yellow with traces of white, the medallion at the top inset with a small gemstone at the centre.

The frieze of floral motifs on the body of the pandan consists of five-petalled flowers with yellow centres linked by a trellis of curling and twisting leaves in bifurcated pairs on a delicate vine. The pale green leaves contrast with the dark emerald-green ground.

A slight flare at the base is marked by a row of petals.

The motifs continue in stately fashion on the lid. The five-petalled flowers encircle a central composite flowerhead composed of layers of radiating petals surrounding the small pale cabochon emerald at the centre.

This silver-gilt pandan with a flat dome and circular plan is published in Mark Zebrowski, Gold, Silver & Bronze from Mughal India, 1987, p. 89 and p. 92, pl. 85. Zebrowski describes the decoration as having the tall flowers of the early eighteenth century. The soft colours of two shades of green, yellow and white resemble those of the round hookah formerly in the Krishnâ Riboud Collection in Paris, and now at the Musée Guimet. This is illustrated on p. 93, pl. 8, of Zebrowski’s book and by Amina Okada in L’Inde des Princes: La donation Jean et Krishnâ Riboud, 2000, pp. 116-117.

Zebrowski suggests that the Riboud hookah base and the present pandan were probably made in the same centre. If the Deccani attribution is more likely than that of a northerly centre of enamelling such as Jaipur or Lucknow owing to the colour palette, then the place of manufacture of both these splendid objects is likely to be Hyderabad.

Provenance:

Spink and Son, London, 11th April 1996

Acquired by Ann and Gordon Getty from Spink and Son

Published:

Mark Zebrowski, Gold, Silver and Bronze from Mughal India, 1987, p. 89 and p. 92, pl. 85.

Spink and Son, Indian & Islamic Works of Art, 1992, p. 31, cat. no. 21.

This pandan has been acquired by the David Collection, Copenhagen.

india (lucknOW), 19th century

height: 5.8 cm

Width: 17 cm

depth: 7.4 cm

Weight: 620 gramS

An oblong silver and silver-gilt hinged box with an arched lid. The exterior of the box and cover has a silver ground that is pierced, enamelled and set with gem stones in the elegant blue and green on silver palette characteristic of Lucknow metalwork. The lid is hinged to the box along its length at the back and fastened with an S-shaped clasp on the front. Upon release of the clasp, the lid lifts open to reveal a silver-gilt interior that contrasts with the exterior in both its plain, undecorated surfaces and the sudden burst of warmth imparted by the gilding.

The lower part of the box is decorated on all four sides with pierced and chased floral arabesques, consisting of six-petalled flower-heads alternating with five-petalled flowers in profile, sprouting on a scrolling vine with bifurcated leaves and delicate buds. The vines are framed by thin double margins at the top

and bottom and underlined by a band of curved petals arranged in a chevron just above the broad and plain solid silver base of the box.

The pierced decoration continues on the lid, with stacked flowers on horizontal interconnected stems beneath the curve of the arched shape, underpinned once again by a band of chevrons. The top of the lid is solid, not pierced, and is gem-set with three bold central flowers in foiled white sapphires and cabochon rubies in gold florets, on a background of green enamel. Bordering the green enamel cartouche are bands of scrolling gold vines bearing five-petalled cabochon ruby flowers and white sapphire leaves against a blue ground. The vivid colours of the enamels and the sparkling gemstones make an effective contrast with the lace-like silver filigree below.

Provenance:

Spink and Son, London, 11th April 1996

Ann and Gordon Getty, acquired from Spink and Son

Published:

Spink and Son, Visions of the Orient: Indian & Islamic Works of Art, 1995, pp. 20-21, cat. no. 11.

india (deccan, bidar), circa 1775

height: 16 cm

diameter: 14.5 cm

A bell-shaped bidri hookah base with vertically fluted sides, a dentated ridged shoulder and a rounded base, decorated in silver inlays of floral motifs and foliate vines.

The flaring mouth has a serrated rim and a protruding flange at the base, below which the narrow neck is ornamented by a chevron collar. The shoulder has an elaborate treatment of five concentric ever-widening circles of designs. Just below the chevron collar is a ring of buds, then a frieze of petals framed by a thin border of squares, followed by a wide band of scrolling flowers and leaves related to the blossoming vines in the flutes. The shoulder is finished with an edge of dentated petals in relief that overlap with the flutes that emerge below, from between the tips of the petals.

The body of the hookah base is decorated to spectacular effect with thirty flutes. The top part of each flute sits recessed below the petals of the shoulder but at the bottom the flutes float, seeming to lift in relief above the surface of the hookah base. The flutes are decorated with two alternating floral designs, a rising stack of flowers and a scrolling vine of nodding flowers. The rounded base is decorated with closely related floral motifs.

A bell-shaped hookah base of similar fluted form is illustrated in Jagdish Mittal, Bidri Ware and Damascene work in Jagdish & Kamla Mittal Museum of Indian Art, 2011, pp. 110-111, no. 30. This has a slightly earlier type of decoration to the flutes and has been dated by Mittal to circa 1750.

Provenance:

Spink and Son, London, 1998

Private American Collection

Exhibited:

Art of the Islamic World, The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 2015.

SOuthern india ( tamil nadu), 18th century

height: 10.6 cm

Width: 7.4 cm

diameter: 2.9 cm

A cast and chased bronze finial in the form of the head of a mythological lion (yali or sinha mukha). This ferocious beast, most probably the finial to a cane or staff, is depicted with horned bulging eyes separated by a crest to the forehead, an open gaping mouth with protruding, curling tongue and powerful dragonlike fangs. The nape of the yali’s neck is dressed with elegant, stylised braids of hair, the lower neck decorated with six overlapping layers of knotted and beaded hair and jewellery.

A yali is a leogrpyh, a fantastic composite rearing lion or tiger with

aspects of the dragon or gryphon. It is also called a yalaka, meaning a horned, hybrid lion. The term sinha mukha means literally lion’s head or face.

The yali falls into the class of creature generally termed vyala (the adjective meaning wicked or vicious) or shardula, which can be interpreted as both lion and lioness, or tiger. In Indian architectural temple sculpture, these fabulous beasts are often depicted dwarfing the figures of men who oppose them in combat, or shown riding the yali as an expression of man’s struggle over the elemental forces of nature which the beast represents. The yali also represents the uncontrolled passions and appetites rampant in every man that must be mastered, and is associated with Vishnu and the goddess Kali.

india (mughal Style at lucknOW), SecOnd half 19th century

hilt:

height: 17.6 cm

Width: 10.4 cm

depth: 3 cm

lOcket:

height: 13.3 cm

Width: 5.4 cm

depth: 3.2 cm

Scabbard mOuntS:

height: 4.4 cm

Width: 7.3 cm

depth: 3.3 cm

chape:

height: 17.8 cm

Width: 3.9 cm

depth: 2 cm

Weight: 1308 gramS

A set of five silver, parcel-gilt, blue enamelled and gem-set sword fittings comprising a hilt with a tiger head pommel and quillons, a locket, a chape and scabbard mounts with suspension loops for suspending the sword by leather straps or fabric ties. These fittings were made for a talwar, the typical sabre of Mughal India with its distinctive long, curved blade narrowing to a sharp point, and an elaborate and richly decorated hilt, frequently with a disc pommel or as here, with an animal head pommel.

The richly embellished style of decoration seen on these sword fittings corresponds to the tastes of northern Indian courts in the second half of the nineteenth century. The rich blue enamel combined with silver and silver-gilt suggest Lucknow as a likely place of manufacture. A variety of gemstones with table-cut diamonds the dominant jewel, are set into silver collets using the kundan technique.

The most elaborate of the fittings is without doubt the magnificent tiger head hilt, cast with profuse whiskers, open mouth revealing sharp fangs and alert ears. The ferocious and characterful tiger has piercing agate eyes, three rubies forming the ruff on its chin and a ruby collar leading down the back of the jowl from the ears to the neckline. A large tear-shaped diamond ornaments the top of its head. The fur on the tiger’s face and nape is depicted by cascading leaf shapes that morph into the ornate floral decoration of the baluster grip. Scattered amongst the larger table-cut diamond leaves and petals on scrolling silver stems are small, faceted diamonds that add to the glittering surface. The quillons are cast with small tiger heads that relate to the pommel. Though small, the quillons yield nothing in character to the pommel as the tiger heads are similarly set with agate eyes and ruby ruffs. Their mouths bristle aggressively with pronounced fangs.

The basic pattern of six-petalled flower-heads set with diamonds linked by scrolling silver stems with serrated leaves continues in the locket and chape. The scabbard mounts have related but variant decoration of four-petalled flower-heads flanked by continuously bifurcating silver leaf scrolls. The suspension loops are shaped like stirrups, adding to the military quality of the whole ensemble.

The tiger-headed pommel and quillons find comparison with the form of a parcel-gilt, gem-set and cobalt-blue enamelled nineteenth century sabre hilt in the Nasser D. Khalili Collection of Islamic Art. This is illustrated in David Alexander, The Arts of War: Arms and Armour of the 7th to 19th centuries, 1992, p. 200, cat. no. 134.

Bashir Mohamed writes that the tradition of using the heads of rams, deer, lions or horses on swords and daggers arose from the Mughal interest in the art and customs of their Central Asian nomadic ancestors.1 The use of the tiger was also ubiquitous in southern India in the late eighteenth century for Tipu Sultan, the ruler of Mysore, adopted the tiger as his personal symbol and used it on all the banners and weapons in his armoury.

Reference:

1. Bashir Mohamed, The Arts of the Muslim Knight: The Furusiyya Art Foundation Collection, 2007, p. 142.

nOrthern india, 19th century

height: 18.5 cm

Width: 10.5 cm

depth: 4.4 cm

This exquisite calligrapher’s tool case is full of marvellously intricate details, from the gold repoussé decoration with ragamala themes on the outside of the case, to the precision with which the tools within are engineered, decorated then fitted into the compact space organised with deep slots for each tool. The case opens to reveal the tools when the hinged cover set with a convex ogival glass panel to the top is lifted to one side. The complete set of tools includes scissors, knives, razor blades, a pen, a propelling pencil, a compass,

tweezers, pouncing instruments and tiny spoons for ink and pigments. In order to fit much longer implements when used into the box, several of the tools screw into the same gold handle, like a modern adjustable screwdriver with interchangeable heads.

The box is decorated on both sides with musical modes as seen in ragamala paintings from both northern India and the Deccan. On one side is Todi ragini depicted as a sad and tender nayika (heroine) who misses her absent lover. She stands in a verdant glade holding a vina with which she enchants the deer. Other animals have come to listen to her music including birds and snakes.

The snakes seem to have wandered from the other side of the box, which

depicts the snake enchantress

Asavari ragini Asavari is frequently depicted wearing a skirt of leaves, but here she is dressed like Krishna in a costume of peacock feathers, a treatment which we also see in some ragamala paintings. She dances like Krishna too, but her identifying symbol of the pungi, a double reed instrument made from a dried gourd, confirms that she is Asavari of the Saravas tribe of snake charmers as the pungi is famously their instrument of choice. Krishna plays the flute. We see her fingers play on two bamboo reeds while she blows into a single bamboo reed with puffed cheeks. Several snakes have gathered to listen to Asavari’s music, but she has also enchanted a lion, a tiger, and a family of foxes. On both sides of the box, dense hatching

and pelleting texturise the background of the scenes. Related gold repoussé floral sprays decorate the hinged cover.

The floral decoration on the sides and rim of the case follow the decorative idiom of the workshops of Kutch in Gujarat. A milk jug dated to circa 1890 by the workshop of the famous silversmith Oomersee Mawjee is adorned with similar palmettes. This is illustrated in Vidya Dehejia with Dipti Khera, Yuthika Sharma and Wynyard Wilkinson, Delight in Design: Indian Silver for the Raj, 2008, p. 144, no. 51. However, the choice of ragamala painting themes for the decoration of the case suggest an attribution to northern India, in particular Delhi, as do the Persian style instruments of calligraphy contained within.

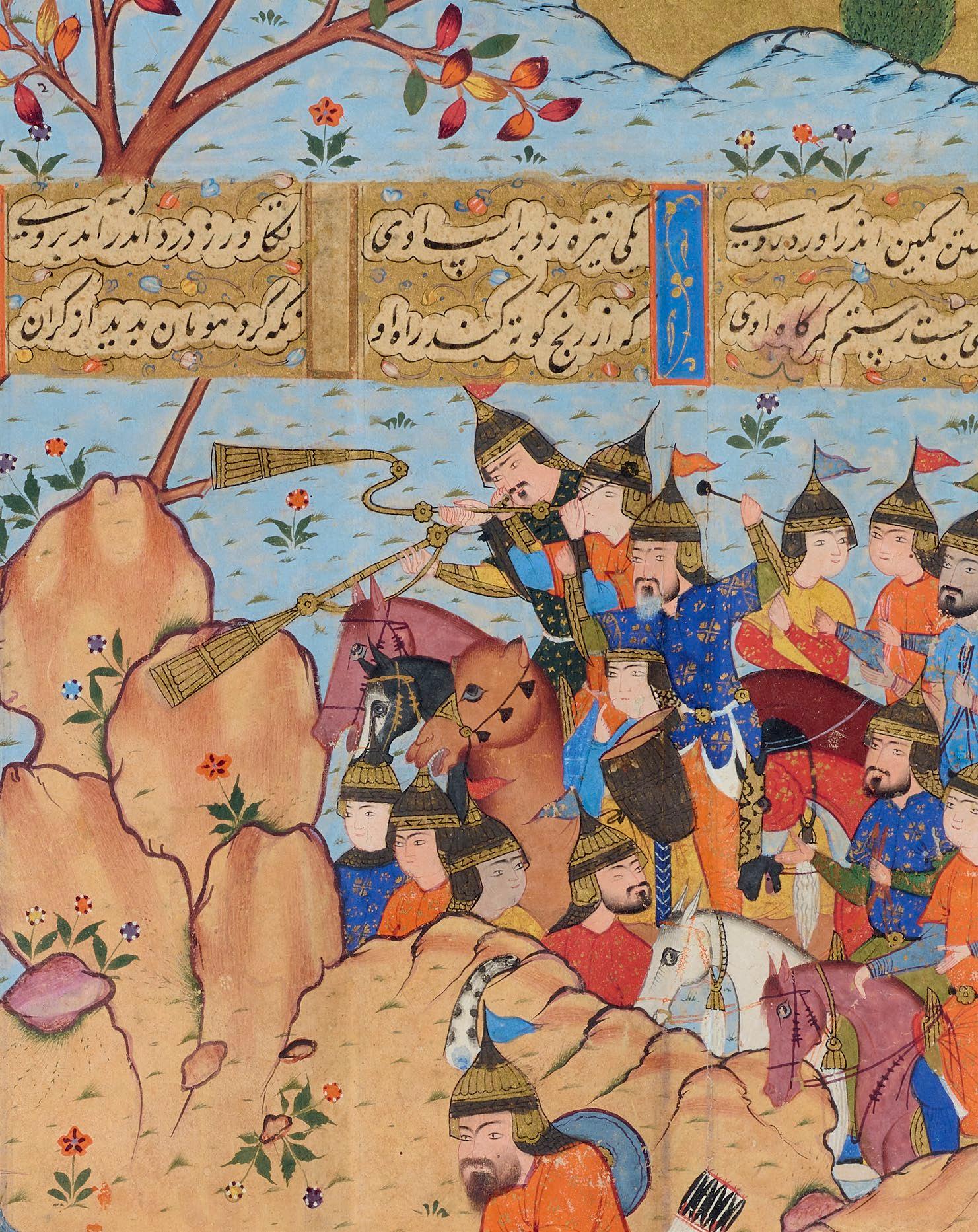

iran (Shiraz), circa 1560

fOliO:

height: 42.5 cm

Width: 28 cm

miniature:

height: 30.5 cm

Width: 22 cm

text area On the reverSe:

height: 25 cm

Width: 15 cm

Opaque watercolour heightened with gold and silver on paper.

The text of the Shahnama is written in black ink on cream paper, in four columns of fine nastaCliq with interlinear and intercolumnar illumination framed by narrow gold bands, dark blue, red, orange and fine black rules. On the illustrated page, the text is written in uncoloured clouds reserved against a gold ground decorated with fine polychrome flower-heads and scrolls, the columns separated by vertical blue bands with trefoil flowers on sinuous tendrils. On the verso are 25 lines of text in four columns, with intercolumnar bands in blue and gold decorated with floral scrolls. The margins of the illustrated page are illuminated in gold with wild and mythical animals, trees, flowers and leaves.

“[Raising] his massive mace upon his [Rustam’s] shoulder, [Human] smote The shoulder-blade of elephantine Rustam”

This episode comes after Afrasiyab’s favourite son Surkha is killed by

Iranians in revenge for the death of Siyavush, the son of Kai Kavus. Upon hearing of this catastrophe, Afrasiyab collects the entire Turanian army and hastens to resist the advancing Iranian forces led by Rustam.

In the combat between Rustam and Afrasiyab, Rustam hits Afrasiyab’s horse on the chest and causes Afrasiyab to fall and tumble from his horse. Rustam is about to catch Afrasiyab when Human, a Turanian hero, son of Visa and brother of Piran, strikes Rustam on his shoulder with his mace. Rustam turns round to see who has hit him while Afrasiyab runs away:

“…Fiercely they Hurled their sharp javelins - Rustam’s struck the head

Of his opponent’s horse, which floundering fell, And overturned his rider. Anxious then

The champion springs to seize the royal prize, But Human rushed between, and saved his master, Who vaulted on another horse and fled.”

Having thus rescued Afrasiyab, Human exercises all his cunning and adroitness to escape himself and at last succeeds. Rustam pursues

Human and the Turanian troops who follow Afrasiyab in the wake of his escape. Thousands of troops are killed in the ensuing chase but no further advantage is gained by either army on the day.

This folio comes from a copy of Firdausi’s Shahnama that is one of the grandest and most accomplished of Shiraz illustrated manuscripts in the later sixteenth century. Ten illustrated leaves from this

important Shahnama, including half the frontispiece, are in the Norma Jean Calderwood Collection at the Arthur M. Sackler Museum, Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge, Massachusetts. The Calderwood Shahnama pages are discussed by Marianna Shreve Simpson in Mary McWilliams (ed.), In Harmony: The Norma Jean Calderwood Collection of Islamic Art, 2013, pp. 77-113, 236-241, cat. nos. 94-101.

Six pages are in the Los Angeles County Museum. Other leaves are in the Museum Rietberg in Zurich, the British Museum in London, the Asian Civilisations Museum in Singapore, the David Collection in Copenhagen, the National Museum of Korea in Seoul and the Yale University Art Gallery.

Provenance:

Private California Collection, USA, 1970s Spink and Son, London, 1990/1991

Mr Noriyoshi Horiuchi, Japanese Collection, 14th May 1992

Private Paris Collection

Literature:

Abolqasem Ferdowsi, Shahnameh: The Persian Book of Kings, (trans.) Dick Davis, 2007.

B. W. Robinson, Persian Paintings in the India Office Library, 1976.

B. W. Robinson, A Descriptive Catalogue of the Persian Paintings in the Bodleian Library, 1958.

B. W. Robinson, The Persian Book of Kings: An Epitome of The Shahnama of Firdawsi, 2002.

J. V. S. Wilkinson, The Shah-Nama of Firdausi, with 24 Illustrations from a fifteenth century manuscript formerly in the Imperial Library, Delhi and now in the possession of the Royal Asiatic Society, 1931.

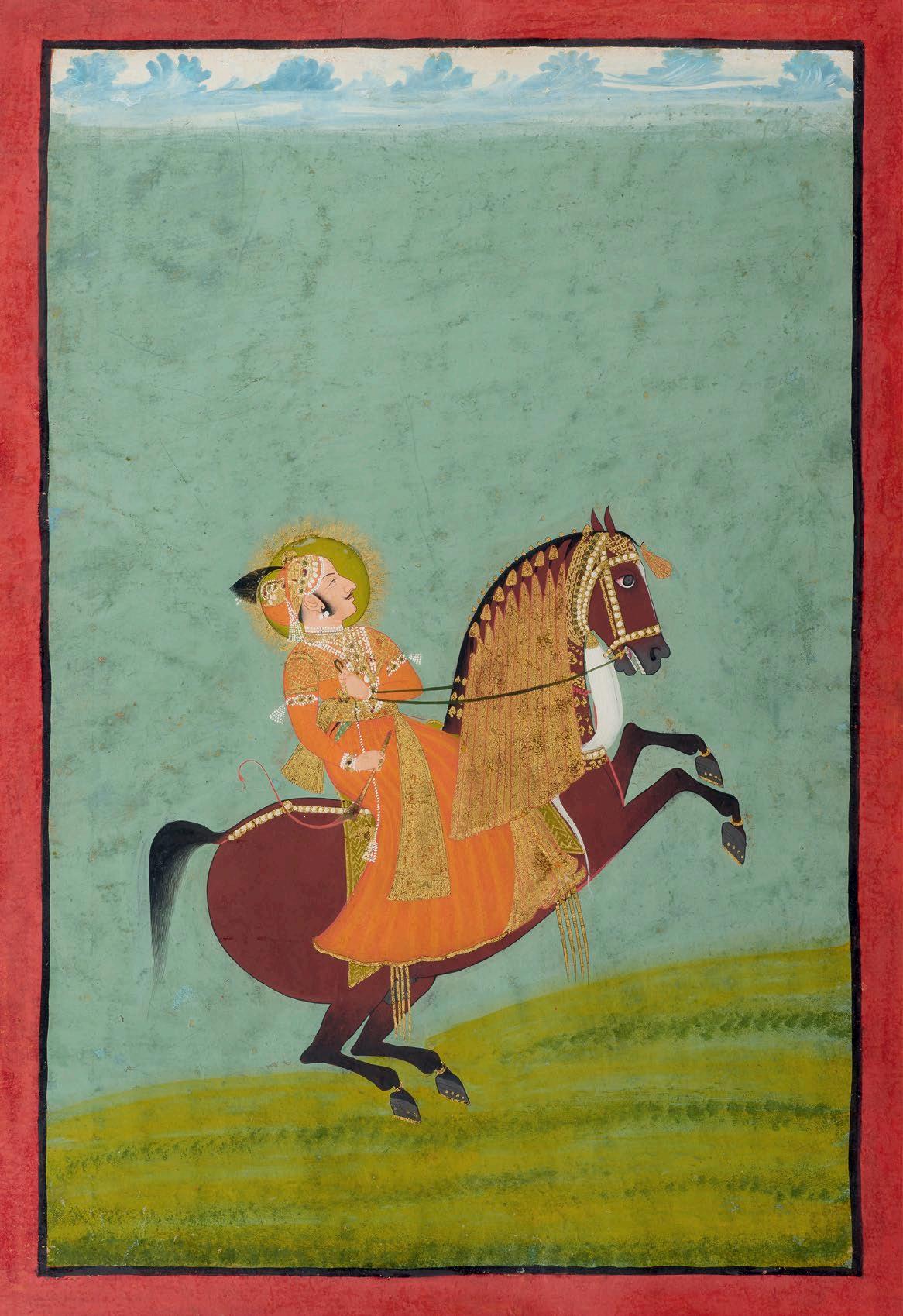

NAWAB KHALIL KHAN

india (mughal), 1680-1690

height: 20.3 cm

Width: 13 cm

Opaque watercolour heightened with gold on paper.

The subject is identified by a devanagari inscription on the reverse.

Also on the back are Persian notations and a partially trimmed inscription in Deccani Hindi that contains a (purchase?) date of V.S. 1792/1735 AD.

An elegantly dressed nobleman stands facing left against a plain background. Of special interest is the horse-headed jade dagger handle (khanjar) that protrudes from his gold brocade coat. The hilt of the khanjar is carved from light grey jade with grooves for the hand on the grip. He holds a gold, ruby and pearl turban ornament (sarpech) in his right hand.

His left hand rests on the gold and enamelled talwar hilt of his sword, the long blade of which is sheathed

in red velvet wrapped with gold brocade to the upper half, the chape resting on the ground next to his leather sandals. His left hand is painted with exquisite detail and elegant poise: a square jewelled ring on his third finger, an oval inscription ring on his little finger, and veins showing through the skin on the back of his hand. Completing his ensemble is a fur scarf around his neck that together with his warm layers of clothing suggest that this portrait was painted in the winter time.

The landscape is lightly tinted with green in the gently rising ground on which he stands with wispy clouds in the sky above. The portrait is mounted on an album page with a floral border trimmed at the outer edges and surrounded with green and gold borders.

Provenance:

Spink and Son, London

Published and Exhibited: Spink and Son, Indian Miniature Painting, Wednesday 25th November to Friday 18th December 1987, pp. 28 and 29, cat. no. 10.

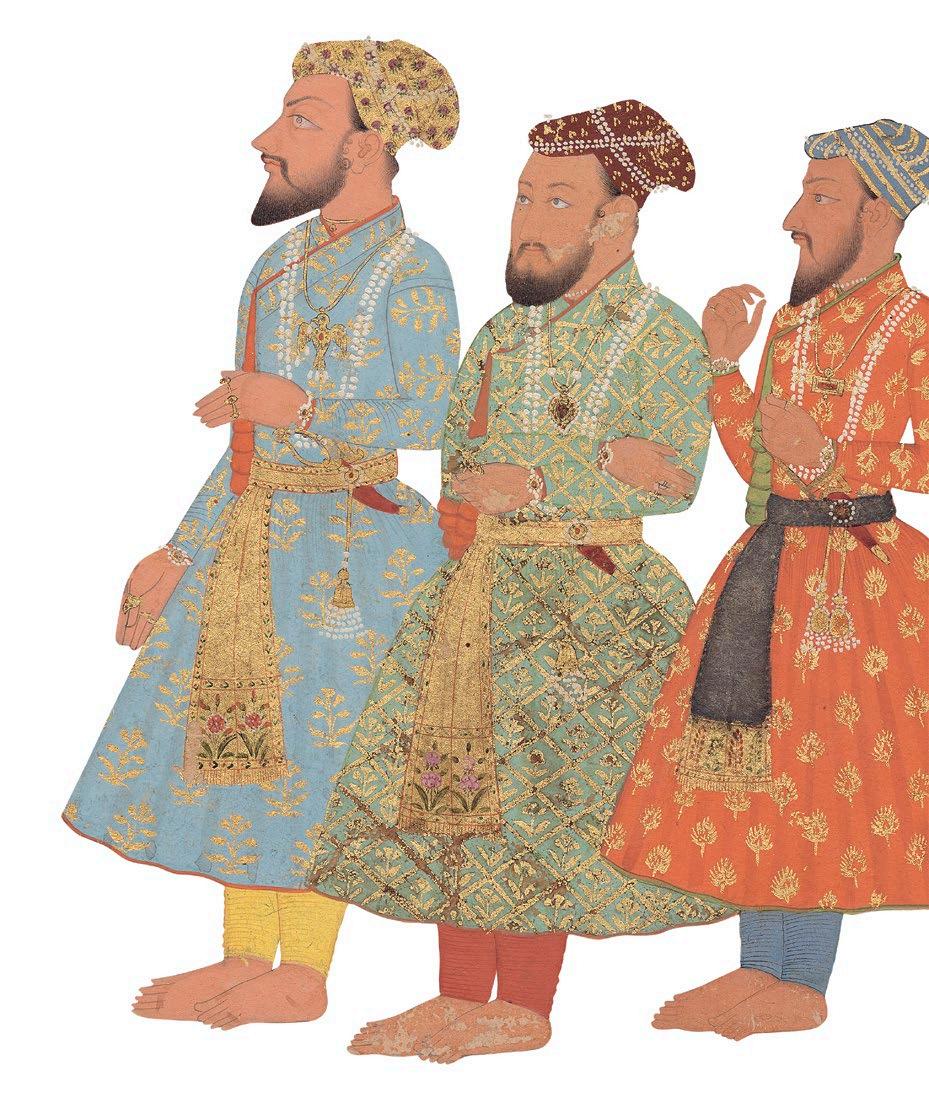

india (udaipur), late 17th century

height: 39 cm

Width: 56.2 cm

Opaque watercolour heightened with gold on paper.

Inscribed with a poem in Rajasthani Hindi to the top border:

duha: sore se seli [ta] ji: turi agare ?lakh: sai tere karane: chhora se lab lakh// 2?// patasya sri surtan memadi sabi//

A finely painted and unusual miniature depicting the Mughal emperors Akbar, Jahangir, Shah Jahan and Aurangzeb visiting two holy men at a shrine. They are accompanied by other Mughal emperors and princes, courtiers, dignitaries of the Mughal court and Rajput chiefs and princes.

The emperor Akbar leads the entourage, who approach the holy men at a natural shrine formed by a group of overhanging rocks, painted to symbolise the opening of a cave in a cliff dotted with trees.

Within the cave sits a Hindu ascetic or yogi while outside, dressed in white and wearing a cap, sits cross-legged a Sufi mystic. The Hindi ascetic sits with eyes closed in a gesture of deepest meditation. The Sufi mystic holds a string of meditation beads in his right hand, and although not depicted speaking, is obviously giving a learned religious discourse to the attentive group of noblemen.

Not all the figures in this interesting painting can be identified, but immediately behind Akbar in the top row are Jahangir followed by Shah Jahan as a young man. The figure below Akbar and Jahangir may be identified as Shah Jahan in his old age, followed by his four sons. The

young prince near the Sufi mystic has yet to be identified.

Standing respectfully behind the Mughal rulers are the Rajput chiefs and princes with their distinctive turbans and their jamas (coats) tied on the left side.

The impressive and dignified man in yellow towards the right of the front row is Man Singh of Amber, leaning on his staff with his hands clasped as usually seen in many of his portraits. Behind him is probably Chhatar Sal of Bundi. The man in blue at the end of the entourage to the right margin of the painting may be Gaj Singh of Marwar and the man dressed in pink Bhagwan Das of Amber.

Not surprisingly, though this is a painting from Mewar, one cannot find depicted amongst this splendid group a Maharana of Mewar. The Mewar rulers were always very proud of the fact that they did not fall in with the Mughals.

The contrast between the simplicity of the robes of the holy men and the sumptuousness of the courtiers could not be greater. Akbar, seen closest to the meditating ascetic, is dressed in a jama heavily brocaded in gold and tied with a patka (sash) with leafy sprigs. A dagger is tucked into his patka. He wears striped trousers but in accordance with the holiness of the visit does not, like all the other noblemen, wear shoes.

The other rulers and nobles are dressed with equal sumptuousness and their colourful costumes, fine jewellery and elaborate patkas and turbans create a great sense of occasion.

Of particular note are the wonderful array of dagger hilts, which include a blue carved jade ewe’s head hilt, a white jade horse head hilt (khanjar), a dagger with a floral scrolled hilt (chilanum) and a katar or thrust-dagger.

The incident depicted is an imaginary one. Towards the end of the seventeenth century and during the early eighteenth century, the Mewar rulers commissioned paintings and portraits that reveal their interest and fascination with their Mughal adversaries and their lineage. This painting demonstrates Akbar’s widely admired religious tolerance. Akbar was known to have consulted religious leaders and holy men of diverse creeds.

However, Aurangzeb, here tellingly depicted as a prince and son of Shah Jahan rather than as an emperor in his own right in the top row, was famously intolerant, would not have visited such a shrine.

This important painting therefore explores the tension between the Mughals and the Rajputs, and perhaps paints an idyllic and idealistic picture of religious and political co-existence. It is a fascinating document providing much insight into the Rajput mind, allowing the modern viewer to study Mewar attitudes, while the Mewar rulers in turn, by commissioning such a painting, reveal their own study of the

Mughals, their fellow Rajputs, and ultimately themselves.

The painting has a bold red border outlined in yellow towards the inner margin.

Provenance:

Mewar Royal Collection, inventory number 20/6

Spink and Son, London, 1987

Pierre Jourdan-Barry, (1926-2016), Paris, purchased from Spink and Son on 17th March 1999

Spink and Son, London, 2000

H.H. Sheikh Saud Mohamed Ali Al-Thani

(1966-2014), purchased from Spink and Son on 14th March 2000 until 8th April 2014

Bonhams, Bond Street, London, Indian and Islamic Art, 8th April 2014, lot 257

Simon Ray, London, 2014-2015

Private European Collection, 2015-2023

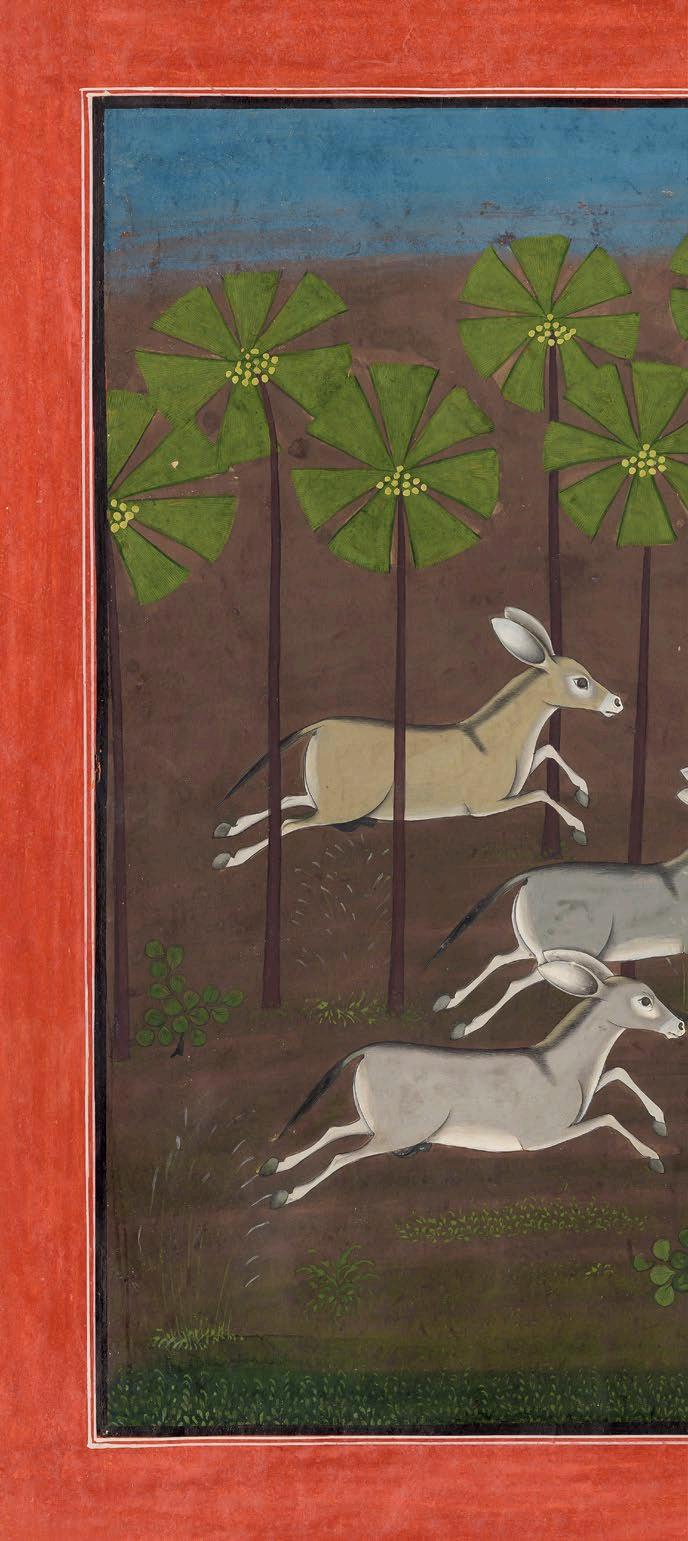

india (deccan, gOlcOnda), circa 1680

height: 20.3 cm

Width: 13 cm

Opaque watercolour heightened with gold on paper.

An elegant half-length portrait of a bearded Muslim prince or nobleman with a falcon perched on a pink leather gauntlet on his right hand. His jama, tied to the right, is made of white cotton printed with trefoil leaf sprigs outlined and veined in gold. His exquisite turban in shades of aubergine, gold and orange, is held in place by a white and gold cotton band printed with upright green sprigs that match those of his jama

The prince’s handsome side profile is enhanced by the careful contouring of his eyelids and brow, with a delicate curl of eyelashes matching the three stylish curls of his sideburn. His tear duct lends further expressiveness to his gaze. Contrapposto is introduced by the three-quarter turn of his torso towards the viewer. Kinetic energy floods through his right arm to the falcon who turns back to look up diagonally at its master, its talons agitated as if waiting to launch into flight at the prince’s signal. The tension expressed by the bird of prey

and its eagerness to hunt is thus contrasted with the noble serenity of the prince who is in charge and in control. The gesture of the prince’s cupped, ungloved left hand conveys the certainty that in a few moments, he will raise both arms and release the falcon into soaring light.

On the reverse is an eighteenth century painting of a tall balustershaped blue-and-white vase of flowers between two small cups, all standing on a similarly decorated tray. The background was repainted sometime before 1967.

Provenance:

Kevorkian Collection

Sotheby’s, London, 6th December 1967, lot 169 and 7th July 1975, lot 6 Francesca Galloway, 2003

Published and Exhibited:

Ivan Stchoukine, La Peinture Indienne à l’Epoque des Grands Moghols, 1929, p. LXV.

Marie-Christine David and Jean Soustiel, Miniatures Orientales de l’Inde, 1985, no. 88.

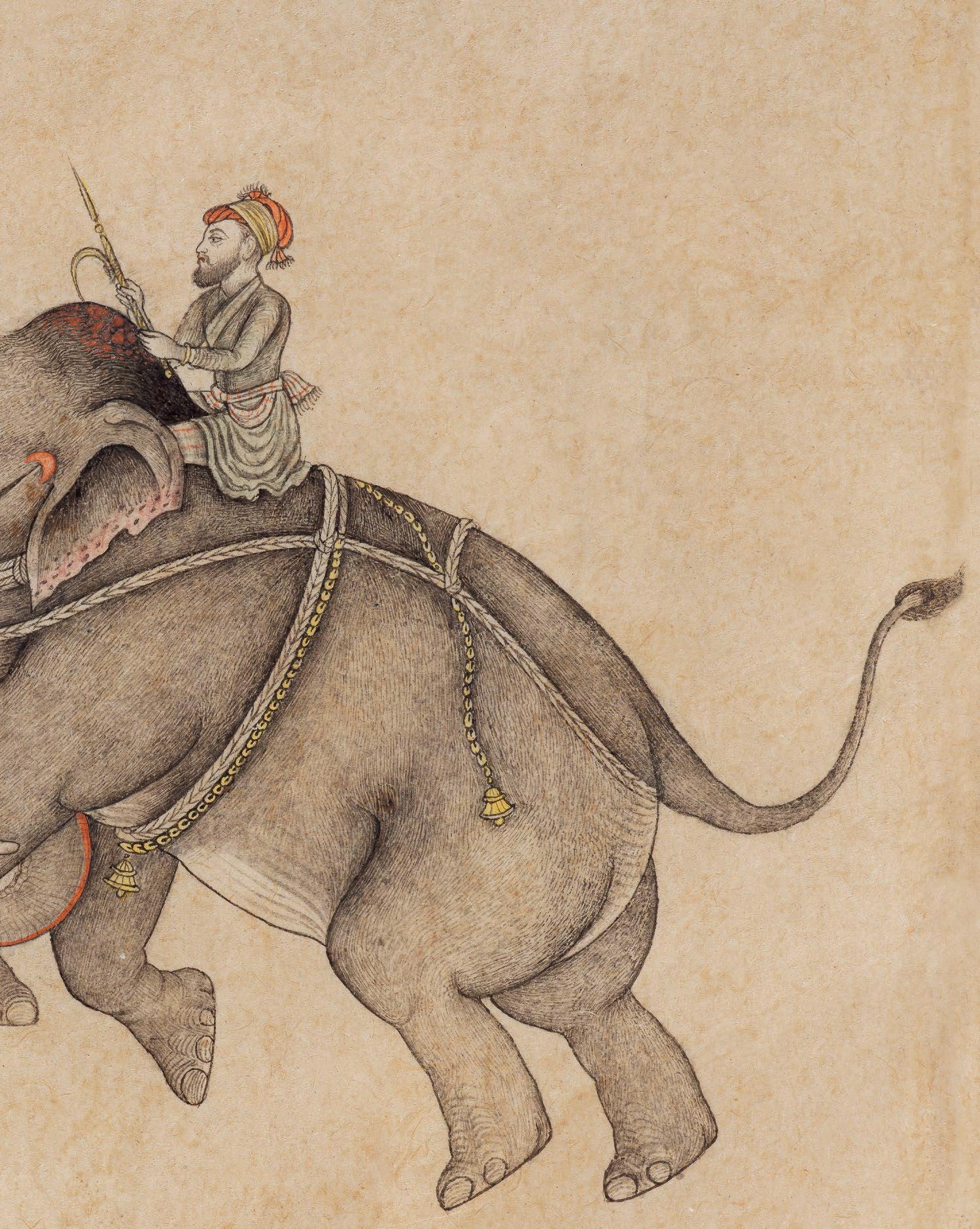

india (rajaSthan, ajmer regiOn), circa 1750

height: 21 cm

Width: 12.7 cm

Ink and wash on paper.

Having charged at each other at top speed and now forcefully collided with trunks, tusks and legs intertwined, two huge and powerful elephants are engaged in ferocious, thrilling combat, urged on by their mahouts (riders) each carrying an ankus (elephant goad). This lightly coloured (nim qalam) drawing skilfully captures the massive weight and volume of the elephants’ bodies, the pink dotted edges of their flapping ears, their wrinkled hides covered with fine hair, the sense of lumbering movement permeating their combat. The elephants are at once ponderous yet agile, their customary gait now replaced by the velocity of weight overcome and channelled into propulsive force and high impact. Yet the viewer may detect merriment in the animals’ eyes, as if they are enjoying their sport rather than gone berserk on a mad rampage.

The elephants are caparisoned with ropes and chains with bells but no

saddlecloths as befitting animals in combat. The turbaned mahout on the elephant charging from the right, apparently the more senior of the two riders, is seated on the neck and shoulders of his beast, his legs tucked behind the elephant’s ears. His bare-chested and skull-capped opponent on the elephant on the left has slipped almost to the rear of the beast, hanging on only by gripping the rope on the elephant’s back with his left arm. Despite his precarious position, he is as calm and concentrated as his companion, both showing consummate riding skills and mastery over their beasts. We may presume on the pictorial evidence that these elephants and their mahouts would be dignified on parade and ferocious as part of a battalion in warfare.

Elephant fighting was a popular subject in the Mughal ateliers and also at Bundi and Kotah in Rajasthan, where court artists created a new genre that produced masterful works. This work would appear to be from one of the neighbouring courts in that sphere of influence. Though the most celebrated examples of elephants fighting come from Bundi and Kotah, the subject was initially developed at Ajmer, the court to which we attribute this drawing.

For other eighteenth century drawings of elephants in combat, from Bundi and Kotah, see McInerney, 1983, nos. 20 and 27.

Provenance:

Kenneth Jay Lane (1932-2017), New York Sotheby’s, New York, 21st-22nd October 1977, lot 311 Private Collection, New York, 1977-2023

Reference:

Terence McInerney, Indian drawing: an exhibition chosen by Howard Hodgkin, 1983.

The flamboyant jewellery designer and socialite Kenneth Jay Lane was famous for building a global business empire selling shamelessly fake but remorselessly chic costume jewellery to everyone that mattered in high society, as well as his devoted audience of middle-class ladies who watched him on QVC and wanted to emulate his elite clientele of movie stars and royalty.

His clients included Jackie Kennedy Onassis, Princess Diana, Elizabeth

Taylor, Audrey Hepburn, Greta Garbo, Babe Paley and Nan Kempner and many, many others in a dizzying roster of international glamour. He came from humble origins; born in 1932 in Detroit, the son of an automotive parts supplier, his taste was his ticket into Manhattan high society. Lane died in 2017 in his opulent apartment filled with art on Park Avenue. He always maintained that he was himself his very greatest creation.

Besides being a creative genius of “junque” and “faque” jewellery from which he made his fortune, Lane was also a supremely knowledgeable and distinguished art collector with an impeccable eye. He collected in every area but specialised in Orientalist paintings. At the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York is the Kenneth Jay Lane Gallery dedicated to his bequest of Orientalist masterpieces to the museum. It is easy to imagine a man of such refined tastes enjoying this delightful drawing of elephants in combat, so compatible with Lane’s eye for the exotic, the oriental and the dramatic.

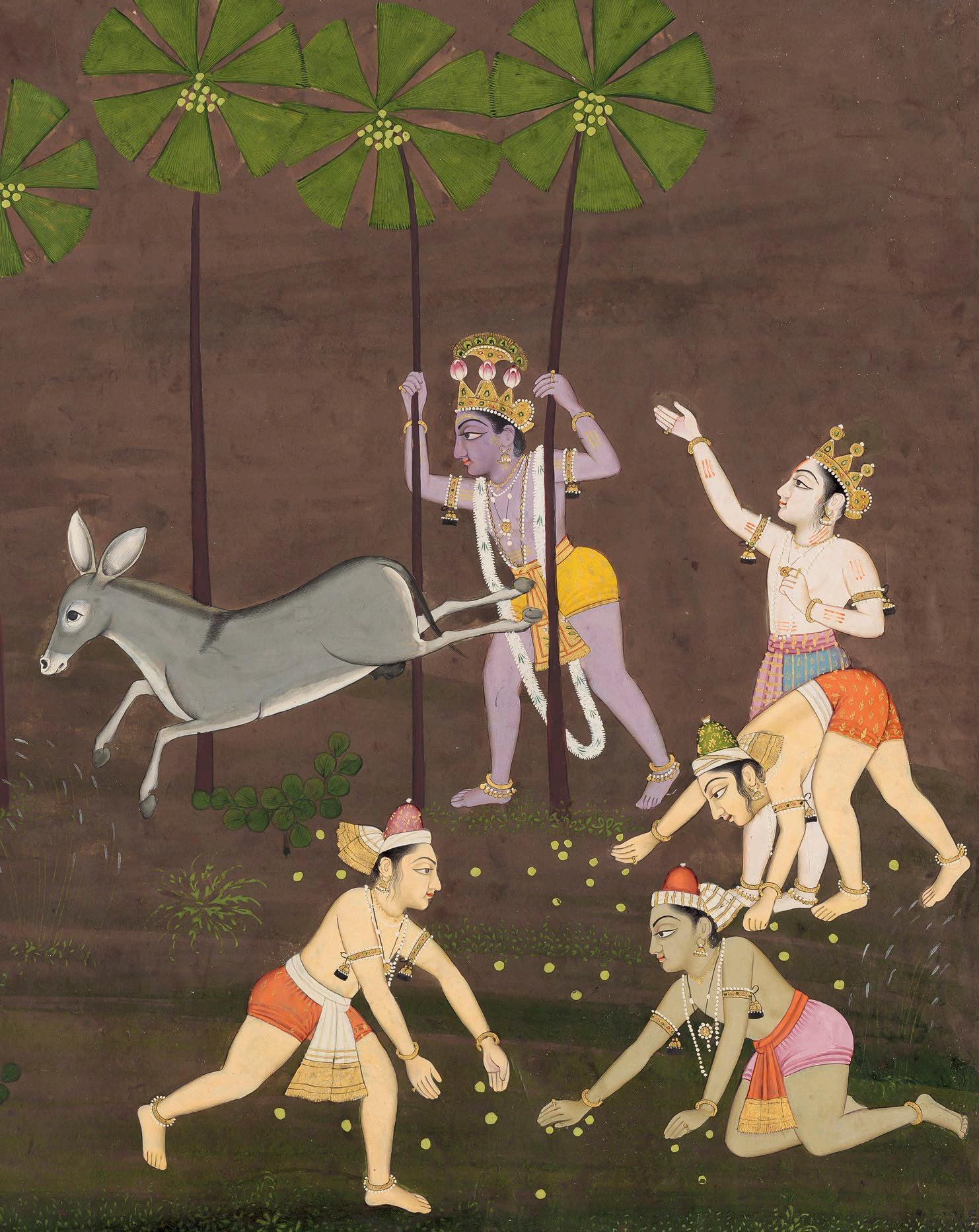

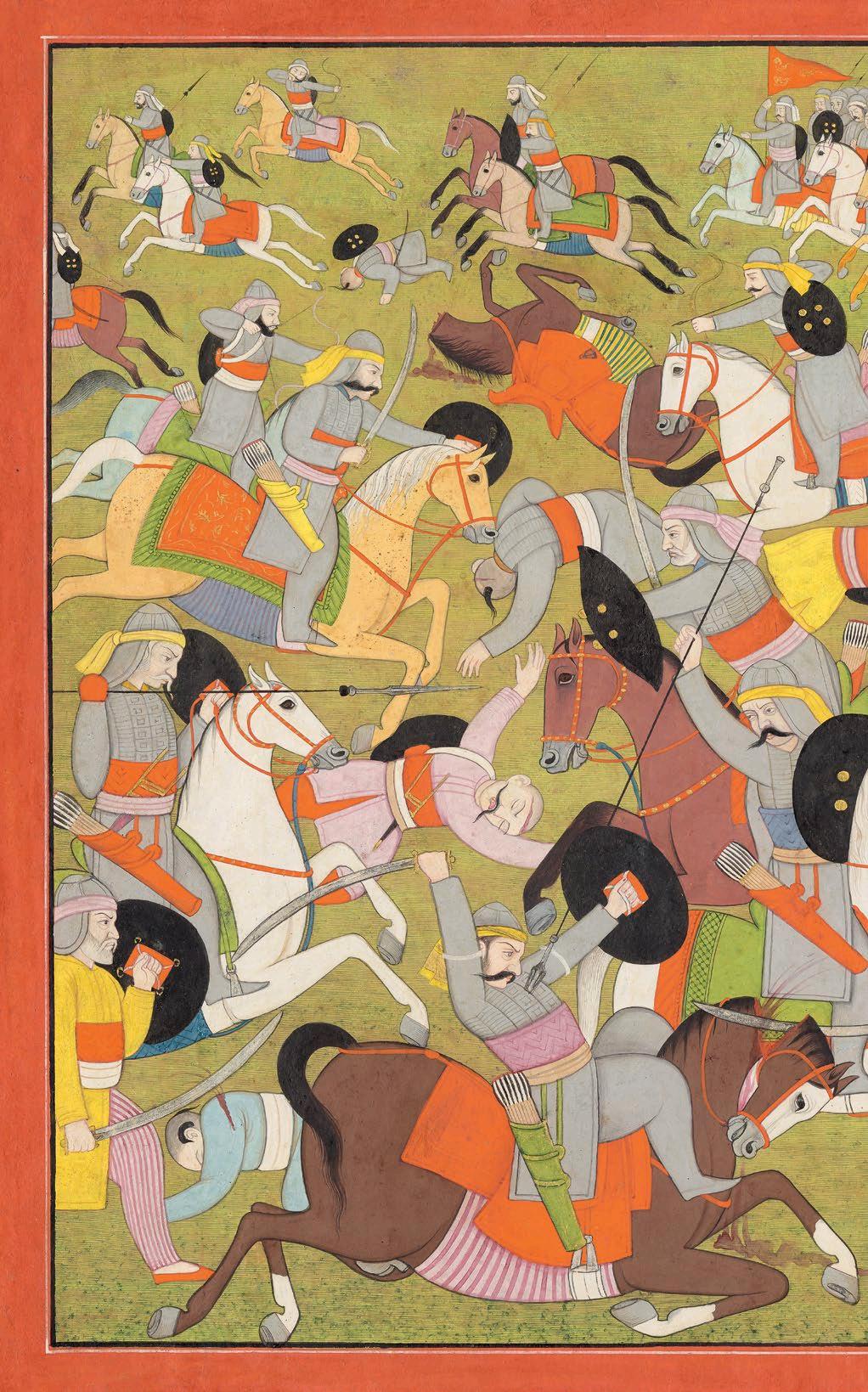

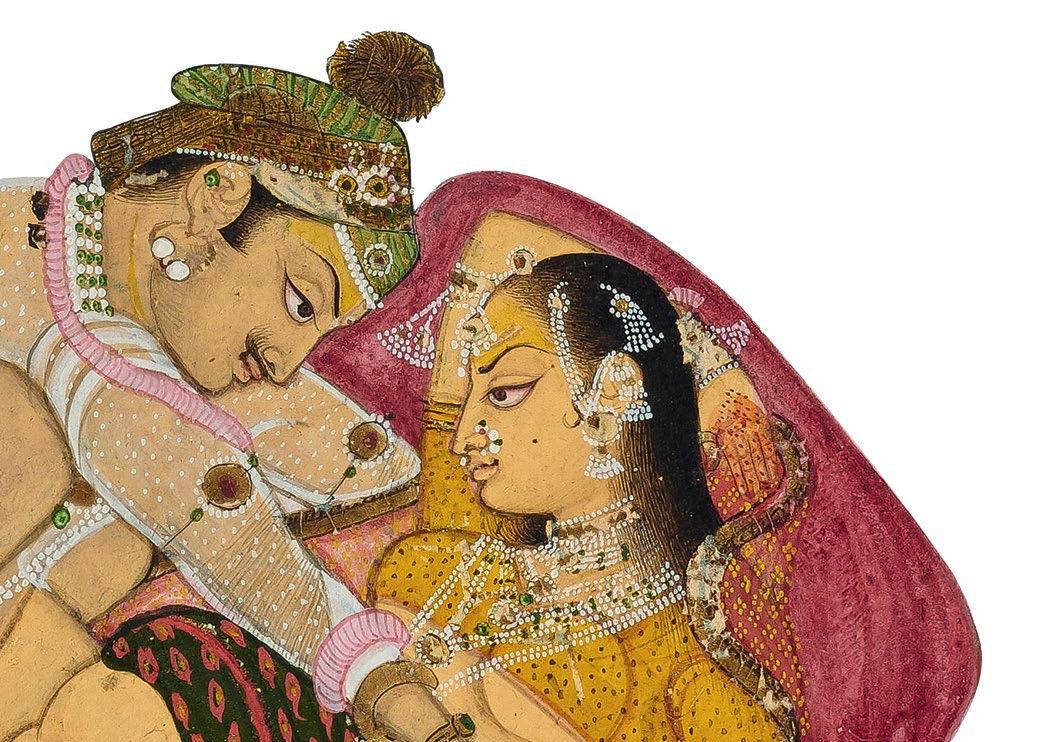

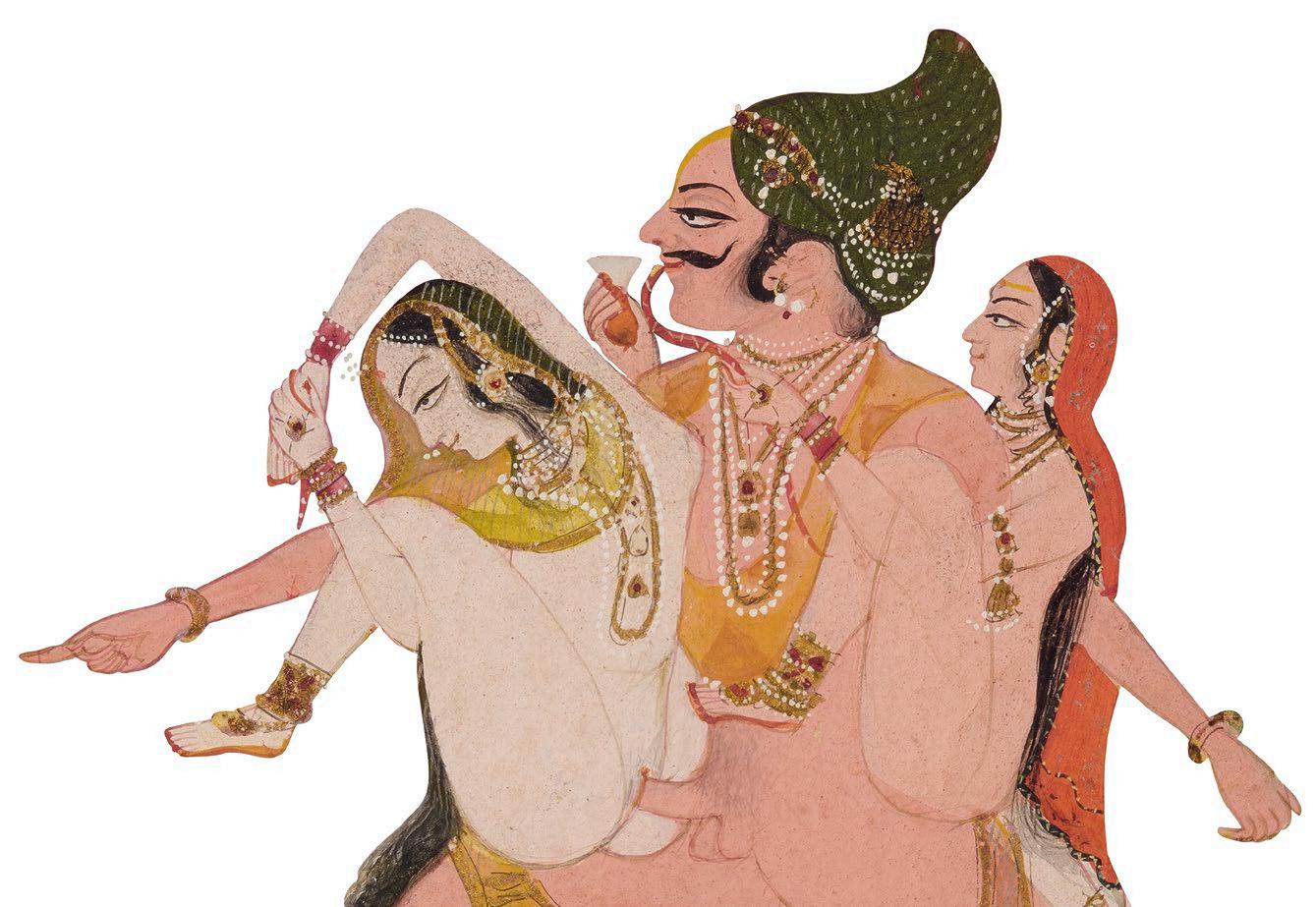

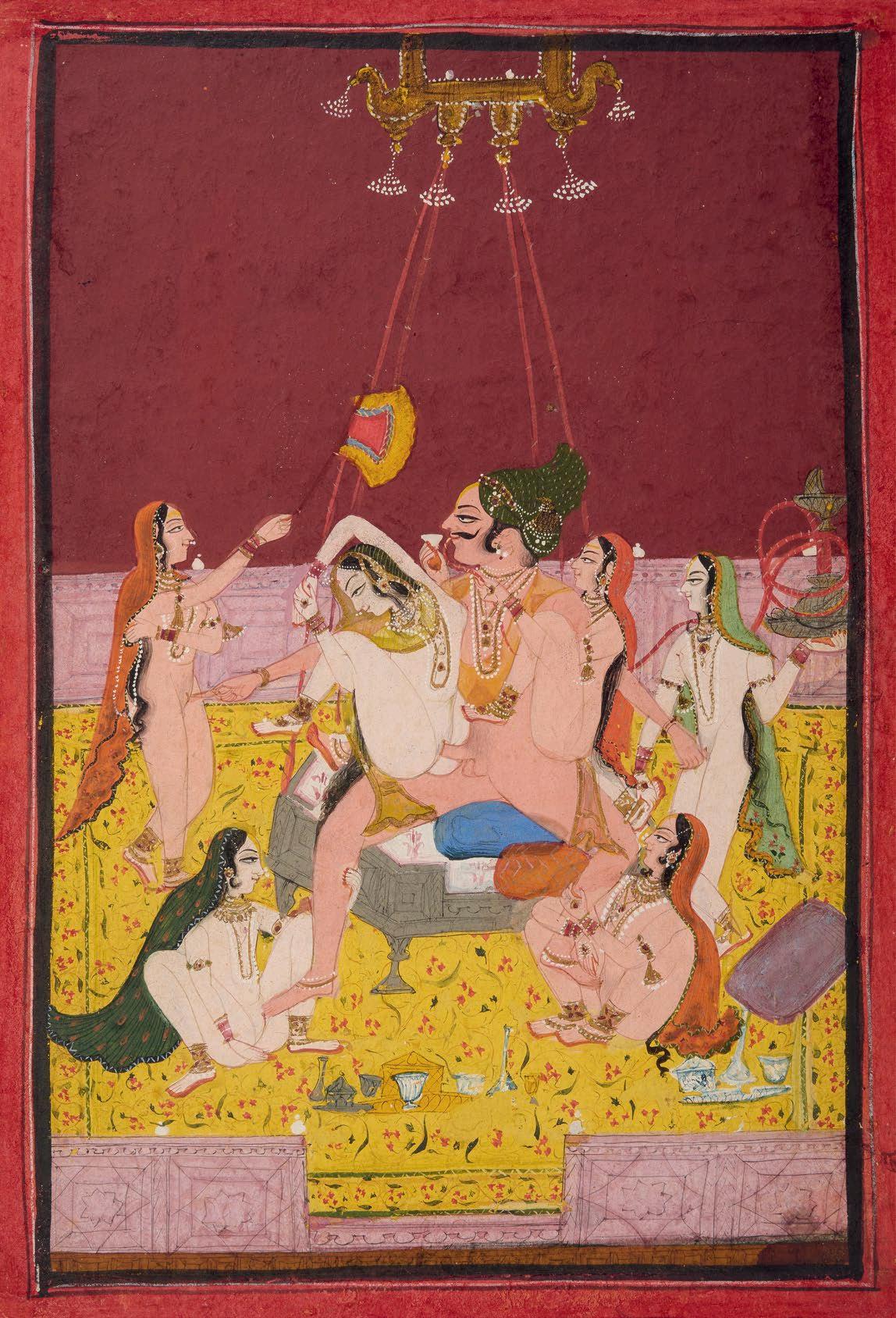

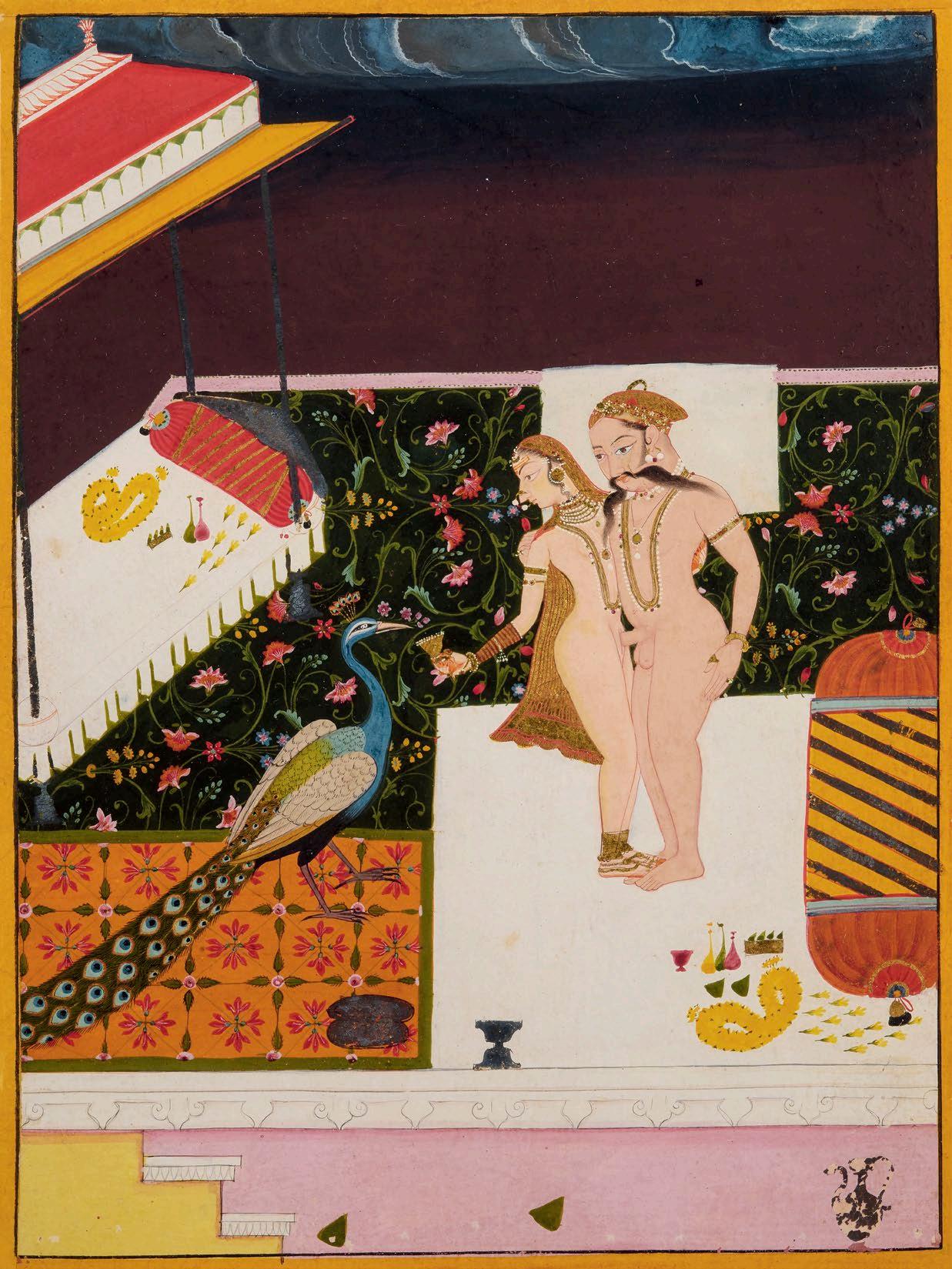

india (kangra), 1800-1810

height: 24.8 cm

Width: 33.7 cm

Opaque watercolour heightened with gold on paper.

An

A titanic battle is taking place between Krishna’s armies and the massed armies of Shishupala and his allied forces. The vast army of the Yadava clan is led by Balarama holding his ploughshare and seated in a howdah on a charging elephant. The action is propelled from right to left by Balarama, preceded by the front line of Balarama’s cavalry, which has caught up with the enemy forces advancing from the left to right.

The fallen and the injured from both sides lie trampled on the blood-stained ground beneath the opposing forces. A horse lies decapitated in the background and a beheaded soldier sprawls before the bejewelled and truncated tusks of the elephant. In the far distance, more massed troops in support of Balarama arrive at the scene and give chase to Shishupala’s forces. Bringing up the rear behind the

elephant is the bulk of Balarama’s cavalry and infantry regiments, so vast as to trail off the page on the right. As depicted, the balance of the battle has just tilted in Balarama’s favour, with his forces dominant and outnumbering the enemy by ten to one.

The Rukmini Haran is the story of Krishna’s abduction and subsequent marriage to Rukmini, who is betrothed to Shishupala, the powerful king of the Chedis. At a magnificent durbar Rukmini’s father, Bhishmaka, king of Kundinapura (Vidarbha) with his five sons and courtiers, discuss Rukmini’s prospective marriage with a family priest (purohit), who is the gobetween for the proposed union between Rukmini and Shishupala.