SIMON RAY

& ISLAMIC WORKS OF ART

It is with great pleasure that I present this twenty-second catalogue of Simon Ray Indian & Islamic Works of Art, which I hope you will enjoy.

I would like to thank the scholars and experts who have so kindly and generously helped us prepare this catalogue: Andrew Topsfield, B. N. Goswamy, John Seyller, Roselyne Hurel, Robert J. Del Bonta and Will Kwiatkowski.

Leng Tan has written the catalogue descriptions for the paintings and works of art. Leng writes in a communicative way that enables the viewer to enjoy and appreciate the story behind each object.

William Edwards has written the sculpture and ceramic entries. William’s passion and enthusiasm for both sculpture and the ceramics of the Islamic world are beautifully conveyed in his writing.

I would like to thank the following for their expertise in the installation and display of the works of art: Colin Bowles, Kevin Leathem, Louise Macann, Helen Loveday and Tim Blake.

Finally, I would like to thank Richard Valencia for his superb photography that makes the works of art jump vividly off the page. Richard Harris has scanned the paintings for the catalogue, as well as prepared the wonderful colour and repro work. Peter Keenan’s fresh, original and innovative catalogue design beautifully illustrates these works of art.

Simon Ray

North-West PakistaN (GaNdhara), 2Nd/3rd ceNtury

heiGht: 27.8 cm

Width: 23 cm

dePth: 11.5 cm

A carved and polished dark grey schist sculpture depicting the head and upper torso of the Buddha, facing forwards and with his hair tied in an usnisha or top knot of three distinct tiers of dense curls.

Originally part of a much larger sculpture, this Buddha has an oval and sharply defined classical face, looking slightly downwards, his prominent mouth with a plush bow-shaped upper lip suggesting an expression of meditation and solemnity. Above, his long slender nose with flaring nostrils sits below an urna or third eye to the centre of his forehead. Sharp and curving edges create the wide eyebrows which cover large deeply cut stylised almond-shaped eyes and lids. The eyes look slightly down and are half opened. To the top of the head the rich and luxurious rippled hair is gathered into a large bun-shaped

usnisha. Framing his head to either side are pierced elongated ears, stretched by the heavy jewellery worn in his earlier life as Prince Siddhartha. His robes or uttariya fall down in thick folds over the shoulders. The angle of his remaining arm suggests that this was originally a standing rather than seated Buddha.

For a more complete Buddha sculpture with similar hair and facial expression, see W. Zwalf, A Catalogue of the Gandharan Sculpture in the British Museum, Volume II, p.12, pl. 8.

Provenance: Colonel H. Gordon George McHardy

George McHardy acquired this sculpture at Sotheby’s African, Oceanic, American and Indian Art, 11th February 1963, lot 34a. Accompanying this sculpture is the original 1963 Sotheby’s sale catalogue, annotated by the previous owner, with inserted receipt of purchase and cutting from The Times, Tuesday 12 February 1963, which mentions the sale of the piece: “a third century A.D. head and shoulders of Buddha for £170 to an anonymous purchaser”. The current stand was made by the India Department at the Victoria and Albert Museum shortly after the sale.

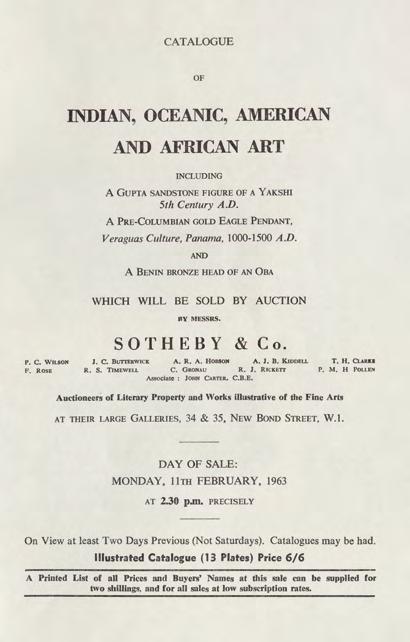

iraN (amul/mazaNdaraN reGioN), 10th/11th ceNtury

heiGht: 7.5 cm diameter: 19.5 cm

An earthenware bowl painted with an off-white slip and decorated in polychrome hues of ochre, dark brown and rust red under a transparent glaze.

A stylised plump bird focuses our attention, dominating the cream ground. It faces left and is painted with an ochre body, rust red collar, beak and thighs. Its large brown eye looks out at the viewer, its feet hanging down as if about to land. Large dark brown roundels with enclosed cintamani spots decorate the body, whilst further small spots form a border around the bird strengthening its outline. Surrounding the playful bird are further large roundels, the

two below with white spots and a single spotted elongated red cartouche above, all floating against the ground. Dark brown splashes border the rim.

This bowl is a fine example of the “Sari” type, named after the Iranian town near the Caspian Sea where these wares were once thought to have been made.

Provenance:

Dr Jeremy David Crosthwaite

Acquired in 1972/1973 at Portobello Road, Notting Hill, London.

Reference:

For a similar bowl with bird and flowers from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, see the link: https://www.metmuseum.org/ art/collection/search/451477

WesterN ceNtral asia ( timurid), 14th ceNtury

heiGht: 52.8 cm

Width: 33 cm

dePth: 7 cm

A magnificent carved and glazed terracotta panel of rectangular form enclosing a trefoil palmette standing on a short waisted foot, the surface densely filled with elegant scrolling floral and leafy arabesques in luminous glazes of rich turquoise, white, lilac and purplish cobalt blue. The terracotta is delicately carved in high relief to give the pierced effect of a veil of lace, the subtle glazes floating against the deeply recessed ground.

Though carved and glazed terracotta is a characteristic Timurid technique of the fourteenth century, this panel is unusual for its many levels of relief. The central trefoil palmette is recessed from the surface of the tile and framed by a stepped border comprising a bold white outline that loops elegantly to the top and bottom in contrasting angular and round knot forms, and a turquoise cavetto leading to a lower turquoise inner frame that surrounds the central arabesque of leaves, split-leaves and trefoil flowers and delicate buds on scrolling and interlacing vines. The angular topknot contains a single circular flower bud, while the loop to the bottom frames a six-petalled flower-head.

The cobalt arabesques to the spandrels on each side of the central

palmette are drawn in a contrasting, more naturalistic style, with the flowers and leaves growing organically upwards, and lush, densely packed stems that bend under the weight of the flowers and leaves. The flowers protrude in yet higher relief above the surface of the whole panel, continuing the play in the levels of relief that is a distinctive feature of this tile panel. The flowers include variegated lotuses and composite lotus palmettes, accompanied by equally variegated leaf forms. A white border frames the whole design.

Carved and glazed terracotta is a highly attractive technique that predates the Timurid conquest, one of the earliest examples being a fragment in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London dated AH 722/1322 AD. Unlike other techniques in the wide range employed by the Timurid tile-makers, such as cut-tile mosaic and cuerda seca, carved and glazed terracotta seems only to have been used in the fourteenth century.

Literature:

Frédérique Beaupertius-Bressand, L’or Bleu de Samarkand: The Blue Gold of Samarkand, 1997. Gérard Degeorge and Yves Porter, The Art of the Islamic Tile, 2002.

Thomas W. Lentz and Glenn D. Lowry, Timur and the Princely Vision: Persian Art and Culture in the Fifteenth Century, 1989. Roland and Sabrina Michaud and Michael Barry, Colour and Symbolism in Islamic Architecture: Eight Centuries of the Tile-Maker’s Art, 1995.

Venetia Porter, Islamic Tiles, 1997.

WesterN ceNtral asia ( timurid), 14th ceNtury

heiGht: 31 cm

Width: 23.5 cm

dePth: 12 cm

A carved and glazed terracotta muqarnas tile, decorated with a finely and deeply carved quadrilaterally symmetrical composition of vines and split-leaf palmettes that interlace to form a lattice of overlapping ogivals, with pairs of delicate confronted buds at the interstices.

The tile has a slightly curved triangular projection at the top of its rectangular body, which gives it a three-dimensional quality, complemented by the deep carving in relief to the surface. The tile is covered with a luminous turquoise glaze, thickly applied in an unctuous layer, covering the undulating surface with rich gleaming colour.

Muqarnas is an Arabic term referring to corbels covered in stalactites,

especially in the vaulted areas of archways or in cupolas. This device, which became widespread in the twelfth century almost throughout the whole Muslim world, is one of the most characteristic features of Islamic architecture.

This fine tile would have formed part of a muqarnas structure within and below the spandrels of an arch, in a mausoleum or mosque. This form can also be seen spread like the leaves of a palm tree as the capital of a round pillar.

Carved and glazed terracotta is a highly attractive technique that predates the Timurid conquest, one of the earliest examples being a fragment in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London dated AH 722/1322 AD. Unlike other techniques in the wide range employed by the Timurid tile-makers such as cut-tile mosaic and cuerda seca, carved and glazed terracotta seems only to have been used in the fourteenth century.

WesterN ceNtral asia ( timurid, samarkaNd), late 14th ceNtury

heiGht: 53.5 cm

Width: 15 cm dePth: 2.5 cm

A panel of intricately cut and finely inlaid cut-tile mosaic or mosaic faience (mo C arraq), composed of cobalt blue, green, turquoise, white, aubergine, black and golden amber glazed mosaics and unglazed warm terracotta pink mosaics. This long and thin panel would most probably have been part of a border framing a larger central panel.

The design is of interlacing twisting and flowering turquoise vines, with variegated stylised flowers and turquoise leaves. The vines sway from left to right as they sinuously scroll up the border. The flowers include lotuses with polychrome petals, a stylised star-shaped sixpetalled flower with alternating pink, blue and turquoise petals, and three golden amber flowers with black and blue centres to the petals. The warmth and lustre of this amber tone has never been equalled in tile-work since the fifteenth century and was once referred to by the

great poet Nizami as “sandalwood”. The golden amber mosaic pieces would have been intensified by applied gilding.

The subtle variations in the intensity of the blues in the various pieces of mosaic, ranging from cobalt and ultramarine to lapis lazuli, highlighted by the sparkle of piquant turquoise and intensified by the moody splendour of rich black and aubergine, impart a glowing radiance and shimmering movement to the panel, as if dappled by a shifting light. The tile panel has a black border to the right and a black and turquoise border to the left.

Provenance: Private Collection assembled in the 1950s Private Scottish Collection

Exhibited and Published: Mikhail Baskhanov, Maria Baskhanova, Pavel Petrov and Nikolaj Serikoff, Arts from the Land of Timur: An Exhibition from a Scottish Private Collection, 8th to 13th January 2013, p. 214, cat. no. 448.

Literature:

Frédérique Beaupertius-Bressand, L’or Bleu de Samarkand: The Blue Gold of Samarkand, 1997. Roland and Sabrina Michaud and Michael Barry, Colour and Symbolism in Islamic Architecture: Eight Centuries of the Tile-Maker’s Art, 1996.

syria (damascus), late 16th/early 17th ceNtury

heiGht: 20 cm

Width: 20 cm

A symmetrical polychrome underglazepainted square tile, in hues of cobalt blue, apple green and black against a crisp white ground and depicting an interlacing framework of composite floral sprays and split-leaf palmettes

surrounding a central stylised rosette, all under a thick glaze.

The centre features a single stylised blue rosette with a white bud framed by a cusped apple green roundel and surrounded by cobalt trefoil petals. Flanking the rosette are four black composite lotus sprays, one to each side, the sprays containing a green crescent cartouche. Large cobalt split-leaf palmettes fill the remaining spaces, each with white and green cloud-like cartouches within. The tips of each palmette join together with one another to form a cross-shaped cartouche within which the composite sprays and central rosette are

contained. Further tendrils emerge from each palmette connecting the inner sprays, creating a cohesive symmetrical design. To the edges are further cobalt tendrils and half composite sprays in apple green.

Identical tiles can be seen in situ in the mausoleum of Mohi al-Din Arabi in Salhiyya, Damascus, and are briefly discussed in Arthur Millner, Damascus Tiles, 2015, p. 171. For an almost identical tile in a similar palette, see Arthur Millner, Damascus Tiles, 2015, p. 275, fig. 6.7 and also at the Victoria and Albert Museum, museum nos. 660-1893 and 506 to B-1900.

iraN (safavid), 17th ceNtury

heiGht: 22.5 cm

Width: 46 cm

A pair of polychrome tiles in the cuerda seca technique depicting a landscape scene of animals amongst dense foliage in colours of green, cobalt blue, white, turquoise and manganese purple against a mustard yellow ground.

The scene presented to us is a snapshot of a tiger hunting, a captured moment when the tiger is seen launching itself at an unsuspecting pair of Ibex grazing and resting nearby. The tiger, its white body decorated with splashes of cobalt blue, green and manganese has its mouth wide open as it pounces towards the prey on the right. Its tail is almost horizontal, adding to the sense of dramatic movement that the scene portrays. Framing the tiger behind are a group of three oversized

floral sprays each with manganese stems supporting leaves to either side in colours of cobalt, green, yellow and ochre. Further smaller sprays frame the tile to three corners.

On the right tile we see something of a contrast as one ibex grazes, unaware of what is about to happen. It has a similar mottled polychrome body as the tiger, but with a large splash of green to its back. A pair of magnificent horns in manganese and cobalt adorn his head as he feasts on the grass below. His companion, whilst resting on the ground, seems to have noticed something is afoot. Her head has turned to look behind her, as if sensing that there is trouble. She is painted in a light green hue.

Provenance: Mahmoud Khayami, CBE, KSS, GCFO (7th January 1930 – 28th February 2020) was an Iranian industrialist and philanthropist of French nationality.

iraN (Qajar), circa 1880

heiGht: 21.6 cm Width: 22 cm

An asymmetrical polychrome underglaze-painted square moulded tile in shades of cobalt blue, pink, turquoise, manganese and ochre against a white slip ground and with a design of figures within a cartouche and landscape.

The focal point of the tile is the central figure, probably a Sufi dervish who is supported by his ceremonial mace with a sheep’s head. He sports

a fine moustache, his white face gazing out beyond the tile’s borders at a sight unseen as he kneels on the ground dressed in a pink tunic with a smart blue coat. Flanking him to either side are two standing courtiers, dressed in vibrant turquoise coats, their hands clasped together as they wait patiently to be called upon. Manganese sashes hang from their waists. All three figures are contained within a white ogival cartouche filled with alternating stylised floral rosettes in pink and cobalt blue. Further cusped arabesque vines in pink and ochre fill the ground, competing with smaller floral sprays for our attention.

iNdia (muGhal), 17th ceNtury

heiGht: 143 cm

Width: 132 cm

dePth: 6 cm

A carved and pierced double-sided red sandstone jali screen with a central geometric design of interlocking hexagons containing smaller hexagons and central six pointed stars. A single fluted channel further highlights the thickly carved hexagons, creating added depth and texture. Framing the central design is a rebated border of pierced quatrefoil cartouches with indented grooves, within a plain surround. Although very intricately carved, they still retain an overall simplicity, due to the fluted hexagons, which dominate throughout. The exquisite carving makes the small hexagons and stars seem to float hypnotically within the larger hexagons, capturing the imagination.

Exhibited: Dulwich Picture Gallery, Reframed: The Woman in the Window, 4th May - 4th September 2022.

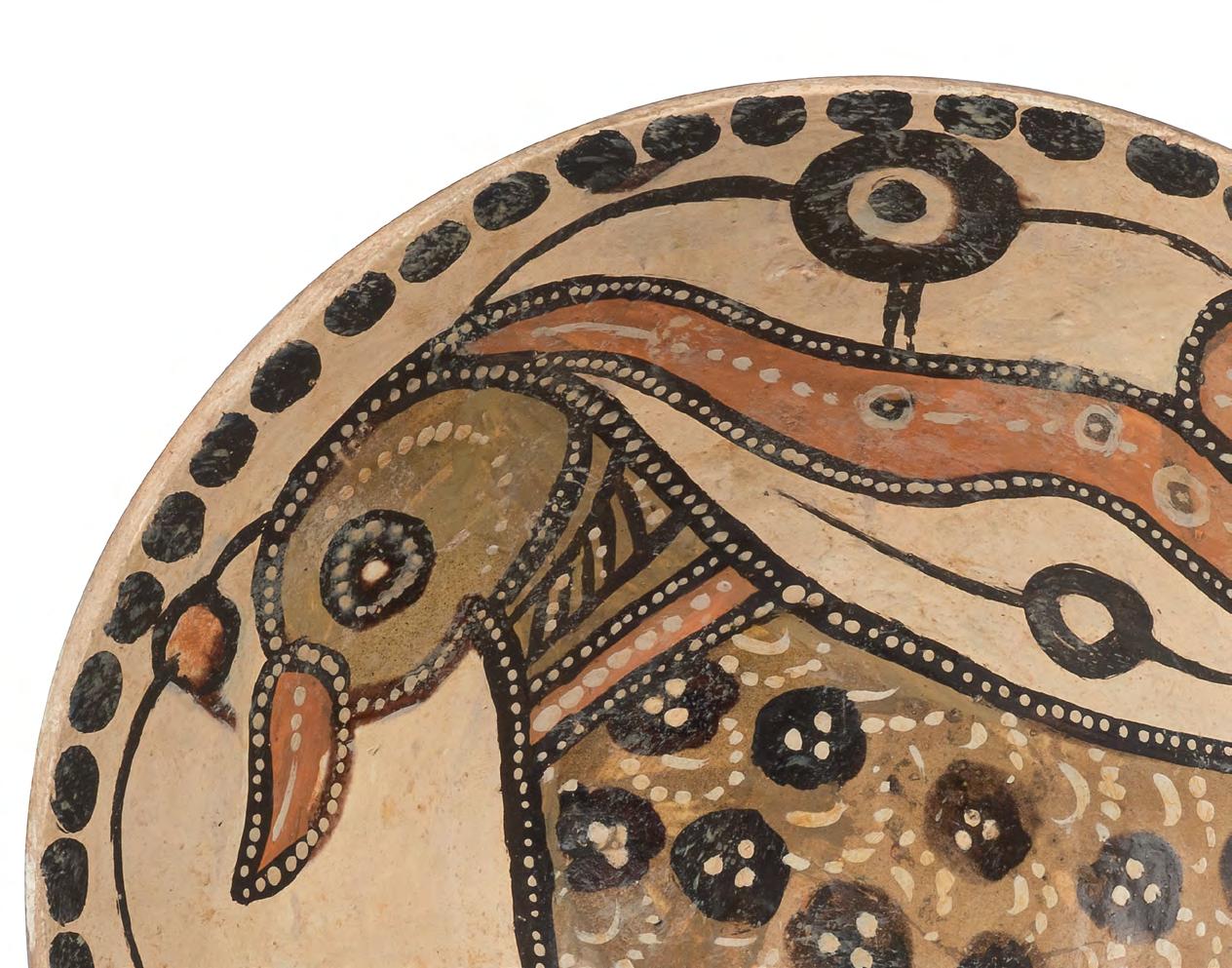

iNdia (muGhal), 17th ceNtury

heiGht: 97 cm

Width: 79.5 cm

dePth: 6.6 cm

A carved and pierced double-sided red sandstone jali screen in the form of a pointed arch, the unusual and elaborate lattice design consisting of interlinked stepped quatrefoil ogival cartouches, each containing a four-petalled flower.

Flutes embellish the inner and outer

edges of the cartouches, while the flowers have an incised central vein to each petal, adding to the richness of surface detail and texture. Each petal is finished with a slight curl to the tip, infusing the formal geometry of the design with a sense of life. Ornamenting the points where the cartouches connect at the top, bottom and sides of each cartouche, are pairs of addorsed three-petalled flowers linked by a central band. The detailed and graceful carving of the intricate and deeply cut lattice is contained and framed by the contrasting broad, plain border.

heiGht: 164 .5 cm

Width: 27.5 cm

dePth: 4 cm

A double-sided red sandstone jali screen, the mottled red sandstone carved with a bold interlocking design of diagonally aligned squares and rectangles. The squares are divided into rectangles by medial struts aligned alternately towards the right or left that increase the sense of movement for the whole design, creating zigzag patterns and symmetrical crosses that dance and spin in jazzy, syncopated rhythms. The tall and narrow proportions and unusually attenuated form that soars upwards with all the modernity of a skyscraper create a jali of consummate elegance. The squares that disappear into the plain borders, forming triangles on all sides of the jali, further increase the sense of movement and the pattern expanding beyond the borders of the jali

The unusual design of this jali, with its arrangement of diagonally aligned squares each divided into two equal rectangles, recalls similar geometric designs seen in the wooden lattice chuang screens from China, where the dazzling effect of squares and rectangles similarly belie their simplicity of form.

iNdia (rajasthaN), late 18th/early 19th ceNtury

heiGht: 27 cm Width: 115 cm dePth: 29.5 cm

A pinkish grey carved sandstone petalled planter, with elongated lotus petals on all four sides. The planter stands on four feet, each of which is cusped to the interior. The planter has a gentle waist to all four sides and a slight swell to the belly giving it a sense of organic growth.

iNdia (muGhal, aGra), 17th ceNtury

heiGht: 27.5 cm

Width: 91.5 cm dePth: 3.5 cm

A panel of white marble finely carved with cartouches and floral designs inlaid with semi-precious stones in the pietra dura technique, the dark brown, ochre and emerald green stones contrasting with the white marble. The design consists of alternating cusped oval and circular cartouches, each with an eightpetalled flower-head to the centre.

The flower-head to the centre of each oval cartouche is set within a circular roundel flanked by lotuses to the left and right. Half a stylised star-shaped flower ornaments the straight edge to the top and bottom of each oval cartouche, while the cusps terminate internally with scrolls and twisting leaves. The flower-heads within the cusped circular cartouches have serrated trefoil petals, while the cartouche itself is ornamented internally with trefoil palmettes.

Between the cartouches to the top and bottom are pairs of sinuously twisting leaves sprouting from stems

that scroll into the lotuses of the oval cartouches. A double border frames the cartouches to the top, bottom and right of the panel. This panel would have formed the corner to a decorative architectural scheme in pietra dura

Provenance: Spink and Son, London

Published: Christie’s South Kensington, Oriental, Tibetan, Himalayan and Islamic Art from Spink, Friday 19th and Saturday 20th June 1998, lot 356.

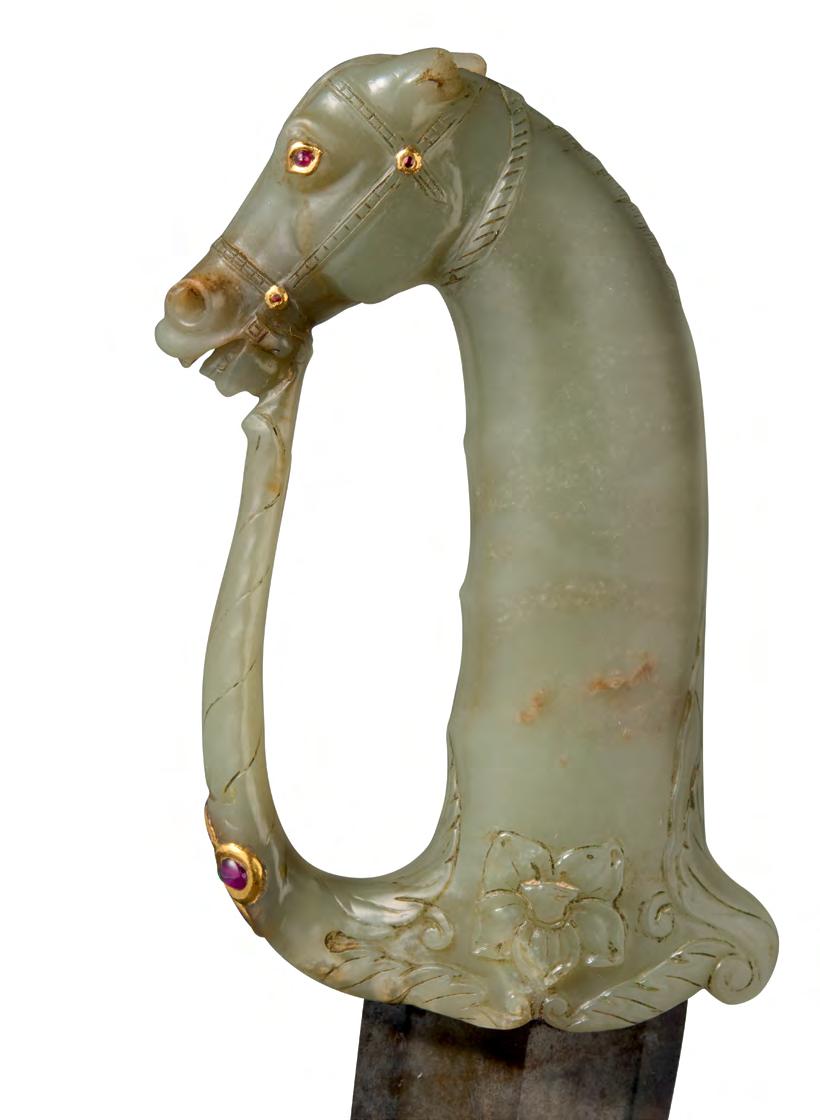

leNGth of daGGer: 37 cm leNGth of hilt: 13 cm Width of hilt: 8 cm

A carved jade dagger (khanjar) with a curved steel blade. The hilt of delicately streaked grey jade is finely carved in the form of a horse’s head, with flaring nostrils, pointed ears pressed slightly back on the head, rounded cheeks, open mouth revealing teeth and tongue, and the mane swept as if by the wind to the horse’s right. The guard and quillons are decorated with scrolling leaf designs, while the base of the hilt is embellished with a bold, radiating flower-head to either

side with a profusion of overlapping petals. The flower seems to be an imaginative hybrid with composite characteristics of both sunflower and marigold, and their shared upright stance on a straight stem.

On both sides of the base of the blade, just where it emerges from the leaf quillons of the hilt, is an inlaid gold cartouche with a blind crest and pendant stylised carnation.

The careful modelling of the face reveals the underlying structure of

bone and muscle beneath the skin, bringing the horse vividly to life before our very eyes. The sprung tension to the mouth is outlined by the taut skin on either side, while the strength of the jaw and the muscles near the throat are brilliantly conveyed. The expressive features and fine carving, together with the weight and proportions of the dagger, admirably convey the power and vitality of the aristocratic animal.

The jade has been carefully chosen and carved with skill. The darkening of the jade from the hilt to the mane and neck defines the face of the horse while the striations that range from dark grey to pale chalky white give rich textures to the smoothy polished gleaming jade.

leNGth of daGGer: 39 cm leNGth of hilt: 12.5cm Width of hilt: 7 cm

A carved jade dagger (khanjar) with a double-edged curved and slightly recurved steel blade. The hilt of fine greenish jade is superbly carved in the form of a horse’s head, with flaring nostrils, pointed ears, slightly open mouth and rounded cheeks, the mane swept as if by the wind to the horse’s right. The horse is carved with a chain around its neck and a bridle complete with nose-band, cheek-piece and head-piece, the interstices set with tiny rubies in the kundan technique. The blazing eyes are set with larger rubies in gold collets and beautifully framed by the carved socket and brows above that bring the beast to life. The expressive features and fine carving, together with the weight and proportions of the dagger, convey admirably the power and vitality of the aristocratic animal.

The mane is carved in separate undulating strands that are combed into nine flowing tresses. A most unusual feature is a large leaf carved in shallow relief beneath the tresses of hair. The leaf rises from the floral decoration of the leafy quillons below. The other side of the hilt is plain, in contrast to the right side with the mane and the leaf. The inner grip is carved with grooves for the fingers. From the floral quillons rises a knuckle-guard that connects the quillons with the chin of the horse. The base of the knuckle-guard is set with a large, jewelled quatrefoil flower with cabochon ruby petals and an emerald centre. The outer surface of the guard is carved with overlapping leaf-forms.

The impact of the dagger derives from an acutely judged combination of stylisation and realism in perfect balance, allied to its sculptural presence and great attention to detail. The jade has been carefully chosen and carved with astonishing skill.

According to Stuart Cary Welch, the grooves on the grip indicate a date in the second half of the seventeenth century, as grooves are rarely found in the horse head khanjars of the Shah Jahan period. Welch’s close study of the many figures in the Padshanama also reveals that the small number

of daggers with animal hilts were reserved for the use of princes such as Dara Shikoh and Shah Shuja.

While the number of daggers with animal hilts increased during the late seventeenth and early eightenth centuries, these continued to function as indicators of the highest rank and position at court.2

References:

1. Stuart Cary Welch, India: Art and Culture 1300-1900, 1986, pp. 257-258.

2. Other horse head daggers from the Mughal period are illustrated in Howard Ricketts and Philippe Missillier, Splendeur des Armes Orientales, 1988, pp. 95-101.

iNdia (deccaN, Bidar), late 18th ceNtury

heiGht: 18 cm diameter: 15.5 cm

A bell-shaped bidri hookah base, inlaid with brilliant silver against a lustrous black ground, with an exquisite design of eight large bold floral sprays, framed between floral meanders and with a low, wide rim and flared mouth to the top.

The central field has a formal composition of eight identical rose sprays, the flowers facing left and angled upwards, their profusely overlapping petals shading the serrated leaves below. A single closed bud can also be seen to each spray, almost hidden in the foliage. The flowers are enhanced by the stellate star-patterned ground surrounding them, the delicate motifs almost suggesting a snowy backdrop. The central frieze of roses is framed above and below by a thin pattern of meandering trefoil leaves within dotted borders. Further wider borders of repeated roses and leafy arabesques fill the remaining ground. A pinched collar of meandering motifs above a small chevron border separates the body from the trumpet mouth, where five smaller rose sprays in a star background fill the space. Radiating teardrop leaves decorate the rim.

This wonderful hookah base is distinguished by the fine brilliance of the silver and the intense, inky black ground. The drawing of the roses in this unusual design recalls Persian painting and lacquerwork of the Zand and Qajar periods during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

The technique of bidriware is thought to have originated in the city of Bidar in the Deccan, which gave its name to this type of inlaid metalwork.1 Bidri is cast from an alloy of which the predominant component is zinc together with small amounts of copper and tin, to which is added varying proportions of lead. The bidri vessels and other objects are then inlaid or overlaid with silver, brass and sometimes gold.2 A mud paste containing sal ammoniac is applied which turns the alloy permanently a rich matte black in contrast to the glittering silver and other metals which are unaffected by the paste.3

For a discussion of the hookah base as well as the application of the bidri technique, see Mark Zebrowski, Gold, Silver and Bronze from Mughal India, 1997, pp. 222-245.

References:

1. John Guy and Deborah Swallow, Arts of India: 1500-1900, 1990, pp.118 and 199; Stuart Cary Welch, India: Art and Culture 1300-1900, 1985, p. 322.

Ibid.

Ibid.

iNdia (muGhal), 1595-1600

attriButed to the artists dhaNu aNd khem karaN

folio: heiGht: 36.1 cm Width: 24 cm miNiature: heiGht: 34.3 cm Width: 20.7 cm

Opaque watercolour heightened with gold on paper.

A folio from the “Third” Akbarnama manuscript.

Mounted on an album page most probably dating to the eighteenth century.

Inscribed in nastaCliq on the right margin:

“The Imperial army in pursuit of CAli Quli Khan”.

Inscribed in black on the verso:

“New number 51”.

The Akbarnama of Abu’l Fazl is the biography of the Mughal emperor Akbar and an imperial chronicle of his reign (1556-1605) and that of his father Humayun (1530-1540; 1555-1556).

With the text on the reverse of this painting now removed, the subject of this lively battle scene from the so-called “third” Akbarnama can be identified only by a fragmentary caption in the right margin that tells us that this painting depicts the imperial army in pursuit of CAli Quli Khan and his forces.

CAli Quli Shaibani, leader of the Uzbek nobles, held fiefs in the east and the Governorship of Jaunpur. He had served as an officer under Humayun and was already one of eight Mughal commanders when Akbar became emperor at the age of thirteen. According to Linda York Leach, who publishes another painting from this Akbarnama depicting Akbar’s forces in pursuit of CAli Quli Khan over the River Ganges in her article, “Pages from an Akbarnama”, in Rosemary Crill, Susan Stronge and Andrew Topsfield (eds.), Arts of Mughal India: Studies in Honour of Robert Skelton, 2004, pp. 52-53, a personal

quarrel with the boy emperor created an implacable hatred in the wily CAli Quli, who at first thought that Akbar would be easy to overthrow. Akbar had difficulties because so many of his officers were one time comrades of the rebel.

CAli Quli initially fought effectively for Akbar and was granted the title of Khan Zaman in 1556, the year of Akbar’s ascension to the throne. However, he became increasingly seditious, and notwithstanding the emperor’s forgiveness of his many transgressions, became a thorn in Akbar’s side and proclaimed open rebellion in 1565. Akbar decided to take matters into his own hands but his struggle with CAli Quli Khan was extremely challenging and complex in terms of military strategy. A concerted campaign against the rebel, as illustrated by the present painting and by the painting published by Leach, continued for eight long years between 1559 and 1567. Akbar finally dealt with him and his equally rebellious brother Bahadur Khan at the Battle of Sakrawal opposite Kara in the Ganges in June 1567. Both brothers were killed.

Due to the length of the campaign against CAli Quli Khan and the paucity of inscriptions on the many paintings that illustrate various battles, it is often difficult to establish precisely which battle is taking place, or its location, or the date of the event.

For example, Leach suggests that the painting she illustrates on p. 52, fig. 8 of her article, “The supply train crosses the bridge of boats on the Ganges”, depicts an incident from late in the eight years of Akbar’s continuous pursuit of CAli Quli Khan and she dates the incident to 1567. Though no doubt as she argues, the Ganges was crossed and re-crossed many times during the lengthy pursuit, we cannot agree with her

dating of 1567 as her painting has an original red number of 158 that survives to show its place in the original manuscript. The paintings of the third Akbarnama were remounted in an album in the eighteenth century when a new sequence was numbered in black on the reverse. In the present painting, we have the “new number 51”.

We do not consider it possible to jump from a story about Humayun watching a game of polo in Tabriz numbered 156 in red, to an Akbar story numbered 158 in red if that takes place in the eleventh year of his reign as she suggests. We think the CAli Quli Khan pursuit over the Ganges more likely takes place much earlier in his reign, in 1559 or 1560 just a couple of years after the last illustrated story about his father.

The backdrop to the battle in the present painting is a fortified city with high impenetrable walls constructed of red sandstone and tall faceted towers crowned with white marble domes. Jerry Losty has proposed that this city may refer to a rebellion of 1565 when CAli Quli Khan was pursued by the imperial forces to Hajipur and Rohtas.

As another possibility, John Seyller has suggested an episode recounted in the Akbarnama, vol. II, pp. 394-395. On 1st February 1566, the emperor himself led an expedition against CAli Quli and his allies, driving them from Ghazpur fortress in eastern Uttar Pradesh and forcing them to make a hasty crossing of the Sarwar river, where their abandoned belongings were seized. The rebel soon repented, and the emperor forgave him once more, but the wretch resumed his ignominious ways and met his end within a year in 1567.

This painting has no ascription, which was probably lost when the lower border was trimmed. Nonetheless, a number of stylistic features have suggested to John Seyller that the painting may be a collaborative work by Dhanu and Khem Karan, two senior imperial artists. Dhanu was active between 1577 and

1599 and worked on most of the manuscripts produced during the 1590s. According to Seyller, Dhanu’s facial types are in this painting less conspicuously idiosyncratic than usual, but are evident in the warriors with such quirky features as puffed-out cheeks, knobby chins and pinched expressions. A similar range of faces is found in his solo paintings in the 1597-1599 Baburnama and the circa 1598 Layla u Majnun at the Bodleian Library, Oxford, illustrated in Andrew Topsfield, Paintings from Mughal India, 2008, pp. 24-25, no. 8, and the circa 1595 volumes of the first Akbarnama. The heavily modelled ibex and gazelles are reminiscent of the same creatures in another painting from the Layla u Majnun, and of the jackals in the aforementioned Baburnama painting.

Other minor details noted by Seyller - the form of the standards festooned with yak tails, the occasional painterly tree, and the tiger skin-patterned caparisonsfurther corroborate the attribution. One of the most distinctive details appears in the fortress, where the four flanking towers are rendered with pronounced shading on either side of the central face. This treatment of a common architectural feature is found only in Dhanu’s work. The zigzagging walls, the substantial boxy rooftop structures and the small, simple domes are also consistent with Dhanu’s style.

The faces of two prominent but unidentifiable nobles - the horseman in silver and gold armour gesturing toward the fortress, and another in a blue tunic trimmed in goldfall outside the scope of Dhanu’s work. They are portraits or special faces, and are attributed by Seyller to Khem Karan, who is named in this subordinate role in two other paintings in this manuscript that are ascribed to Dhanu. These faces compare most closely to Khem Karan’s portrait of Babur in two 1597-1599 Baburnama illustrations. Both artists are capable of these large rock formations, though this element was probably assigned to Dhanu. Recession into space is

suggested by the different colour of each layer of rocks.

The wide variety of costumes fashioned from a mixture of sumptuous fabrics and different animal skins including tiger, leopard and possibly shark leather, make for engaging and delectable viewing as the army charges across the page from left to right in a slight upward incline. Akbar’s forces meet little resistance from the few men of CAli Quli Khan who try to stem their advancing tide. The steady upward trajectory of the imperial forces, and their determined expressions and stances, suggest at once the intractable nature of their task while hinting at imminent victory.

This page is one of more than twenty miniatures that have recently come to light from an important royal manuscript thought to have belonged to Akbar’s mother, Hamida Banu Begam. Scholars who have studied these paintings, in particular Linda York Leach, have identified the manuscript as a third royal Akbarnama

The earliest Akbarnama manuscript is primarily in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum, which has 116 miniatures. This first Akbarnama was painted around 1590-1595 and presented to the emperor as Abu’l Fazl was still working on the text. The Victoria and Albert Museum paintings deal with the middle years of Akbar’s reign (1560-1577). Though dateable to 1590-1595, the paintings are still in the style of the 1580s, full of vigour and excitement.

The second illustrated copy of the Akbarnama, commissioned early in the next century with the text brought up to date, is divided between the British Library in London, which owns 39 illustrations, and the Chester Beatty Library in Dublin, which has 66 paintings. This second Akbarnama is quite different in style from the first manuscript, more

refined and less dynamic, with many of the pages lightly tinted rather than highly coloured like that of Akbar’s own copy. It was produced between 1602 and 1603, probably to commemorate the tragic assassination of Abu’l Fazl in 1602. Amongst the paintings is a dated miniature containing the Ilahi date of the 47th year of Akbar’s reign, corresponding to 1602-1603. The dating of the second Akbarnama is discussed in J. P. Losty and Malini Roy, Mughal India: Art, Culture and Empire, 2012, p. 58.

According to Leach in her study, “Pages from an Akbarnama”, in Rosemary Crill, Susan Stronge and Andrew Topsfield (eds.), Arts of Mughal India: Studies in Honour of Robert Skelton, 2004, pp. 42-55, the newly discovered third Akbarnama pages are related to the Victoria and Albert Museum’s highly coloured, dynamic illustrations and were probably painted after Akbar’s own series, between 1595 and 1600. Stylistically, this manuscript is closer to the first Akbarnama than the later one. Leach convincingly suggests several reasons for identifying the royal family member for whom this Akbarnama was commissioned as Hamida Banu Begam, Akbar’s mother.

From a private collection that has been in England since the 1940s.

We would like to thank John Seyller and Jerry Losty for their expert advice and kind preparation of the notes we have used for this catalogue entry. We also thank Seyller for his attributions to Dhanu and Khem Karan.

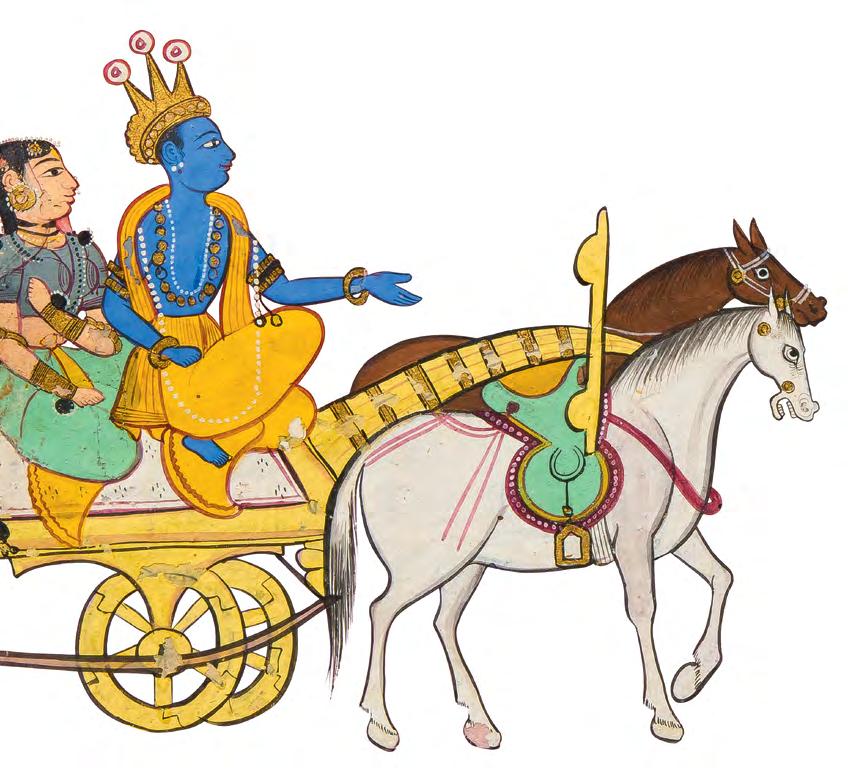

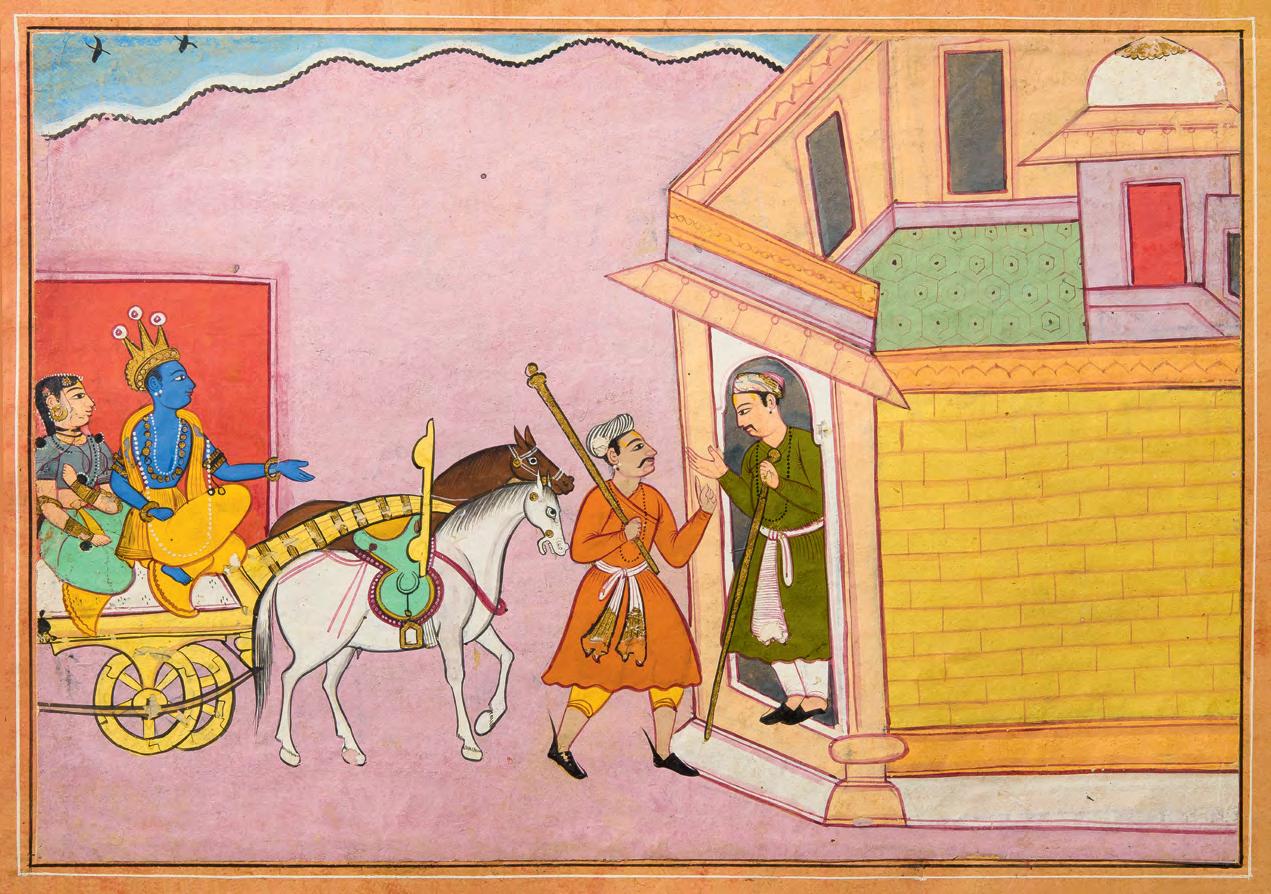

iNdia (BikaNer), 1590-1600

heiGht: 16.8 cm

Width: 24.7 cm

Opaque watercolour heightened with gold on paper, mounted within wide beige coloured borders.

An illustration from a Bhagavata Purana series.

Inscribed on the verso in Sanskrit and Hindi above an effaced Bikaner palace collection stamp. The inscription above the stamp reads:

21 duvarka ji(?) padhair(ya?)

meaning “arrival at Dvarka”.

The inscription to the left is more difficult to decipher. Beginning with “duvarika”, and continuing with “lane rukmini”, meaning “bringing Rukmini to Dvarka”, the sense is in keeping with the central inscription.

Since Krishna is shown arriving at Dvarka with Rukmini in his

chariot, this painting probably illustrates verse 53, chapter 54, from Book X of the Bhagavata Purana:

“Having vanquished all the monarchs in his way, the lord brought Rukmini, the daughter of Bhishmaka to his city, Dvarka, and married her according to Shastric injunction…”1

Krishna has just abducted Rukmini from the shrine of the goddess Ambika before her marriage to Shishupala, the powerful king of the Chedis. According to plan, Krishna has carried Rukmini away in his chariot while Balarama’s forces hold off the furious Shishupala and his allies. The frenzy of battle between vast armies is not depicted in this painting. The culmination of recent events, the arrival of Krishna at his capital with Rukmini, is depicted with linear simplicity, the narrative distilled to only the most essential elements of the story.

Reading from left to right, we see the couple in a golden chariot drawn by two horses. They are framed by the rectangular block of red featured consistently in many contemporary series to designate significant sections

of the narrative, here suggesting the interior of the chariot and highlighting the presence of the royal couple. A single attendant standing in for Krishna’s entourage announces his approach. Another man opens the door to the city, a few palace buildings sufficient to conjure up Dvarka. The long journey they have undergone is indicated by the distant, wavy horizon, the lack of recession conveying the vast expanses traversed. Two small birds flying in the sky reinforce the sense of distance but also function as metaphors of freedom and union. The style is the opposite of grandiose; a sense of intimacy, even secrecy, is admirably conveyed.

A painting from this Bhagavata Purana series in the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, depicts the next stage in the narrative, “The Marriage of Krishna and Rukmini”. The marriage is depicted as a humble affair, with little of the turmoil of preceding events or the regal pomp conveyed by the text.

A painting almost identical in construction to the Houston page is in the Alvin O. Bellak Collection at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Depicting

“The Marriage of Satyabhama and Krishna”, this is published in Darielle Mason et al, Intimate

Worlds: Indian Paintings from the Alvin O. Bellak Collection, 2001, pp. 66-67, no. 18. The Houston and Philadelphia paintings would originally have

followed the present work when the complete series was still intact.

According to John Seyller, this Bhagavata Purana series represents the process by which popular Mughal painting slowly germinated distinctive regional idioms. The paintings demonstrate the way in which artists employed at one of the regional courts of Rajasthan introduced a few features of Mughal painting into an existing indigenous traditional.2 Attempts at imparting a three-dimensional quality are seen alongside figures that float against blocks of colour. While some of the garments are Mughalised, most of the figures retain the squarish heads and schematic faces of the indigenous tradition.3

This series has long been associated with painting at Bikaner, primarily because some of its paintings bear a stamp indicating that they were part of the Bikaner royal collection. Although that now-dispersed collection once contained works from many different schools of Indian painting, the spare compositions, cool palette, and pronounced linear quality of this Bhagavata Purana series are akin to those of paintings produced at Bikaner in the last third of the seventeenth century.4

References:

1. The Bhagavata Purana, (trans.) G. V. Tagore, Vol. 10, 1978, p. 1602.

2. John Seyller in Darielle Mason et al, Intimate Worlds: Indian Paintings from the Alvin O. Bellak Collection, 2001, pp. 66-67, no. 18.

3. Ibid.

4. Ibid.

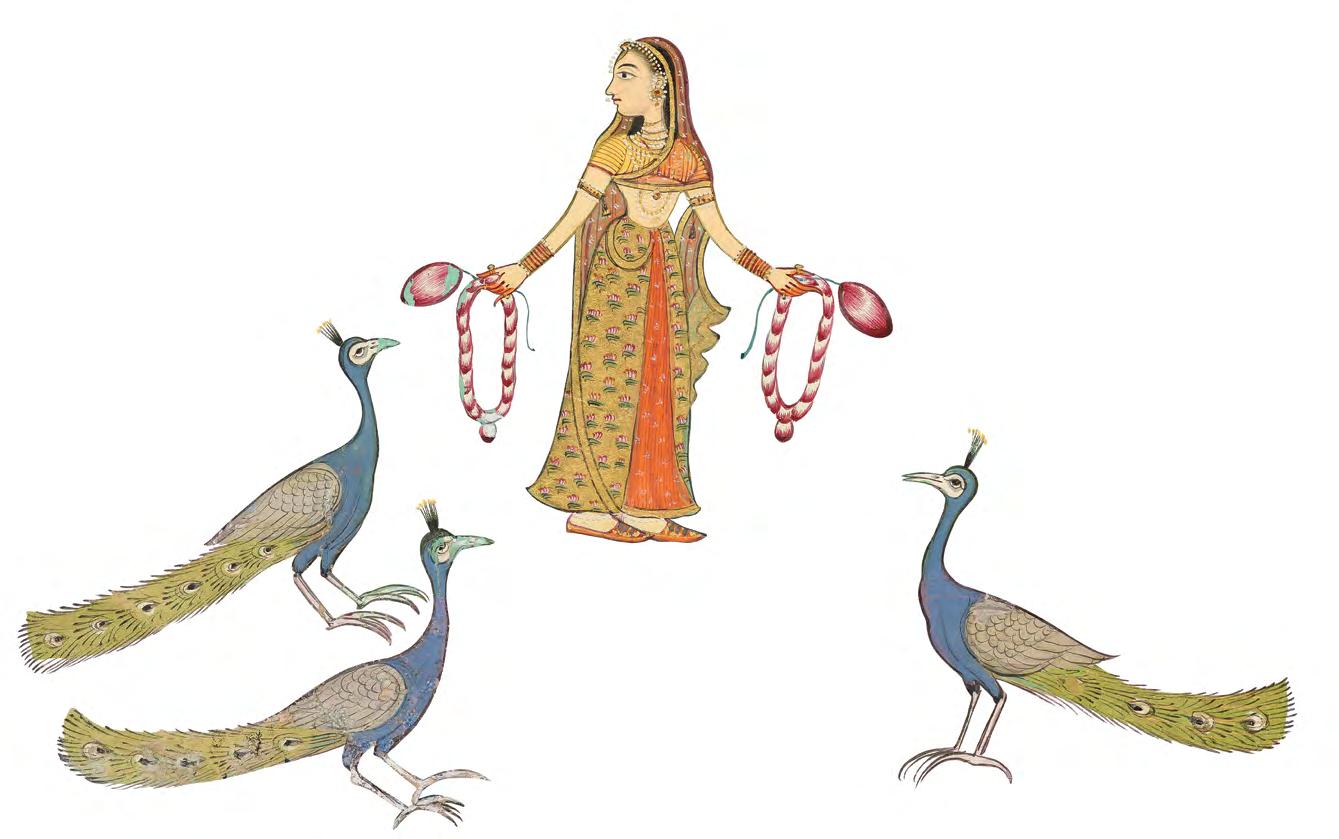

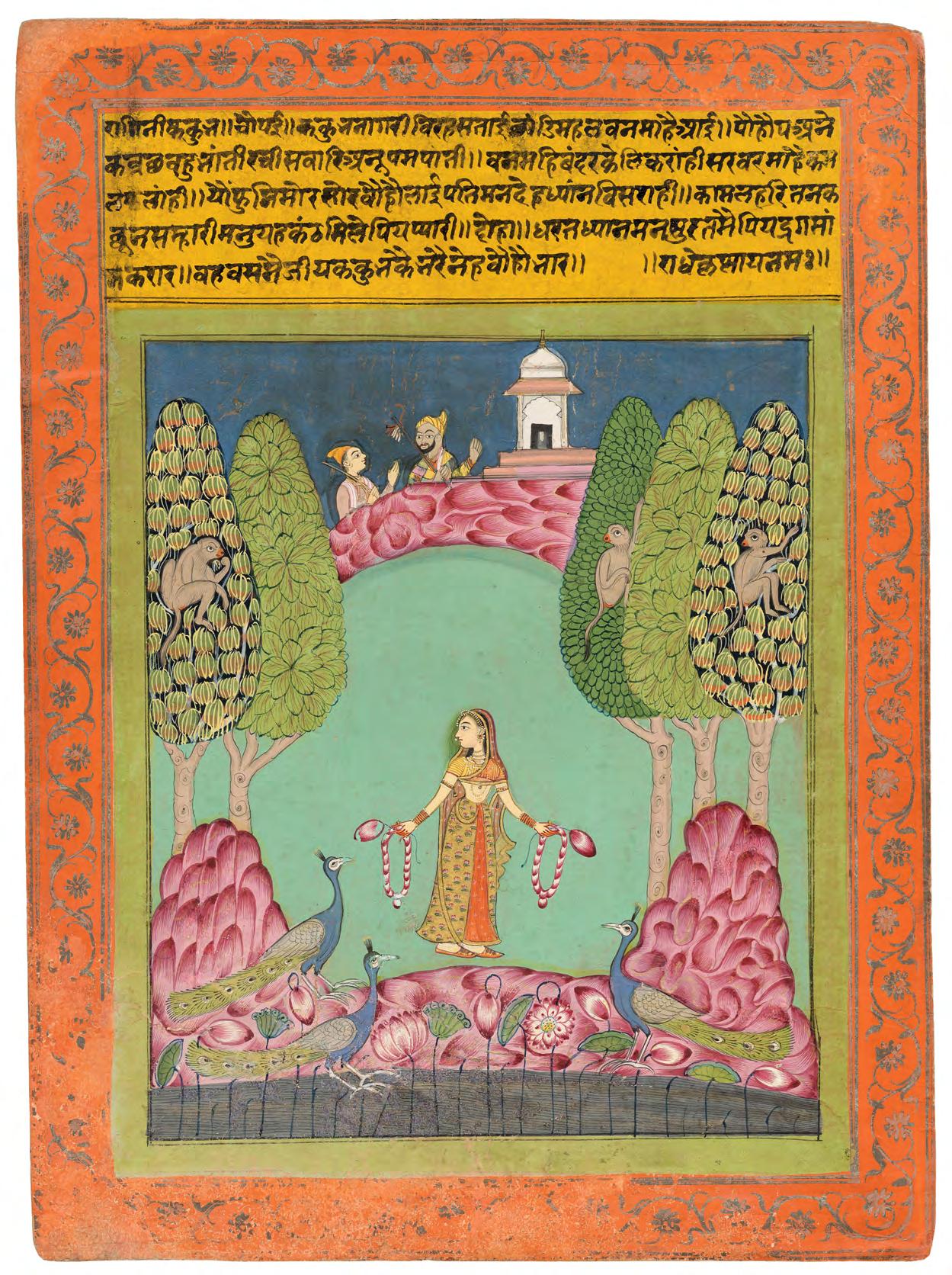

iNdia (rajasthaN, ProBaBly amBer), circa 1740

heiGht: 31.5 cm

Width: 23 cm

Opaque watercolour heightened with gold on paper.

An illustration from a Ragamala series.

Framed by a green inner border surmounted by a yellow text panel containing five lines of devanagari describing the scene, all surrounded by an orangey-red border decorated with scrolling floral vines.

Kakubha ragini is depicted as a maiden standing in a landscape by the edge of a lotus pond, holding lotus buds and floral garlands in each hand. She turns to face the left as if eager for a glimpse of her absent lover, her delicate features silhouetted against a patch of darker green ground and her head covered with a diaphanous veil. She wears a gold skirt brocaded with repeated floral motifs that echo the verdant setting. Her sandal-clad feet point to the right, creating a contrapposto with

her profile and her torso. She stands with a gentle swing to the hips, as if ready to begin a stately dance.

Kakubha is flanked by two peacocks perched on the craggy rocks on the water’s edge; a third peacock wades in the shallows like a heron amongst the lotus flowers. Three monkeys frolic in the dense stylised leaves of the spade-like trees. In the background on the brow of the hill beyond are two musicians playing next to a small marble pavilion that seems to contain a Shiva lingam

A translation of the text, given to the previous owner of this painting by an unnamed curator at the British Museum in the 1970s, is as follows:

“Elegant Kakubha pines for her absent lover. She has left her house and come to a grove

Where blossom many flowers and trees.

She has made a beautiful garland. Monkeys play around the grove. On a nearby pond lotuses bloom. The incessant crying of peacocks attracts her.

Her mind and body are nobly concerned with her lover.

A wave of emotion wells up within her, Making her thirst for a kiss from her prince.

She ponders on love-making. Her eyes thirst for a sight of him. Thus distressed Kakubha burns With the fire of separation.”

For a very similar composition depicting the same Ragamala subject, see Christie’s, Arts of India, 12th June 2018, lot 18 (and see also lots 19 and 20). See also W. G. Archer and E. Binney, Rajput Miniatures from the Collection of Edwin Binney, 3rd, Portland 1968, nos. 51 and 52; Sotheby’s, Indian and Persian Miniatures, 27th March 1973, lots 65-100, especially lot 92.

Private UK collection, acquired by the collector in the early 1970s

iNdia (udaiPur), circa 1730

heiGht: 37 cm

Width: 24.7 cm

Opaque watercolour heightened with gold and silver on paper.

Inscribed on the reverse in devanagari:

maharana sri sagram syaghji(?)

“Maharana Shri Sangram Singhji”

Maharana Sangram Singh (reigned 1710-1734) is seated below an ochre pleasure pavilion receiving three visitors within the luxuriant setting of a lush, secluded garden. Though erected on a white marble terrace in front of a rectangular water tank with eddying waves of silver fed by a copper pipe with a makara spout, the pavilion appears to be a portable structure, erected temporarily for the occasion. It is constructed of robust buff cotton and has three cusped arches on the front supported by wooden pillars painted green. Above the small pavilion is a much larger red canopy (qanat), suspended amongst the trees to provide further shade.

Sangram Singh is seated on a cushion facing three seated noblemen. The intimacy displayed by the first courtier, who massages the Rana’s foot, as well as the splendour of his chevron outfit, suggest that he is the son and heir apparent, Prince Jagat Singh. Sangram Singh holds a ring or flower blossom in his left hand, ready to bestow a gift on Prince Jagat.

Behind Sangram Singh is a seated nobleman. Standing behind are two attendants, one waving a flywhisk over the Rana, while his companion carries a fan.

The small and sketchy figure standing on the left just below the water tank is a quirky feature. It might perhaps represent a small piece of garden or poolside stone statuary. Jagat Singh II a few years later occasionally smokes from a hookah in the form of a woman; this does not look like a hookah though. Neither is it a pentimento or an unfinished section of the painting that has not yet been coloured; the scale of the figure is too tiny to be an incomplete attendant. The figure seems to form a unit with the long horizontal marble frieze of pendant floral lobes that runs from left to right across the length of the terrace, underpinned by a second frieze of white cartouches against a black ground.

In the foreground, guarding the entrance to this secret corner of the formal garden are two crested herons or storks. They amble in stately fashion in the shade of the trees lining this side of the water tank. A musician sits outside the compound, which is marked by an elaborate pierced jali balustrade. The jalis are carved with flowers amongst the openwork scrolls, or it may be flower beds that are being revealed through the cut marble, or indeed an intoxicating and evocative combination of both. The air of calm luxury and opulence that pervades this painting is enchanting indeed.

Provenance:

Mewar Royal Collection, inventory number 35/15

British Rail Pension Fund Anthony Powell 1935-2021, the English costume designer for film and stage, and the winner of three Academy Awards

Published: Sotheby’s, Persian and Indian Manuscripts and Miniatures: from the collection formed by the British Rail Pension Fund, London, Tuesday 23rd April 1996, lot 28.

Acknowledgement: We would like to thank Andrew Topsfield for his expert advice.

iNdia (udaiPur), 1740-1750

heiGht: 50.5 cm

Width: 34.5 cm

Opaque watercolour heightened with gold on paper.

Inscribed to the top of the red border in Hindi in devanagari:

On the verso are Mewar royal inventory inscriptions, written in three stages at the top of the page. The number 52 has been crossed out in red and another inventory number 21/49 added in red. Written in another hand to the right is nam. [for number] and ki. [for kimat or value] Rs 120, followed by the number 843 below. The abbreviation of nam seems divorced from all the usual Mewar numbering systems.

The portly and impressive figure of Jaijairam, dressed only with a wrap around his middle, is seated leaning against a cushion on a white mat placed on a floral floor spread, in front of a large tripoliya (triple gate) arch leading to the garden behind. White blossoms wafting on the breeze sparkle like stars above Jaijairam. Placed on the mat in front of him are adjuncts to meditation: a bowl of cut flowers; a pandan open to reveal fresh betel quids; a chowrie (flywhisk); a backscratcher; water vessels (lotas) and shorter strings of beads.

A standing attendant waves a morchal (peacock feather fan) over the acharya as he tells a long string of prayer beads (rudrakshamala). The figures seated around Jaijairam,

including the two priests in front of him, one of whom also holds a long string of beads, are similarly dressed in just wraps or loincloths. They are all intent on listening to the bhajans or devotional chants that the drummers (dholakwalos) and cymbal players (manjirawalos) are chanting in the foreground.

The name of the acharya Jaijairam and the tilak marks on all their foreheads, consisting of a vertical yellow U with a red stripe, suggest that the devotees are Ramanandis or worshippers of Rama, one of the largest and most egalitarian sects in India.1 It was founded in the fourteenth or fifteenth century by the saint Ramananda, who preached in simple Hindi and believed that all were equal before God.2 He opposed the caste system, admitting women and people of humble origin into his sect. Although not criticising the Hindu pantheon, he made Rama the centre of his devotional movement as he taught that Rama alone could liberate mankind from the cycle of rebirths.3 Ramanandi ascetics rely upon meditation and strict ascetic practices but also believe that the grace of God is required for them to achieve liberation.4 Distinguished members of the sect include the mystic poetess Mirabai and Tulsidas, the Awadhi

poet regarded as an incarnation of Valmiki, the author of the Ramayana, and celebrated for his Hindi dialect version of the Ramayana, the Ramcharitamanas 5

According to Jerry Losty, while artistic activity in the reign of Maharana Jagat Singh (1734–1751) is characterised by large scale paintings of hunts and festivities, there is also a strain of introspective works involving more intimate portrait studies in the last decade of his reign, for example the double portrait of Baba Bharath Singh clothed and half-clothed in the Alvin O. Bellak Collection in Philadelphia. This is published in Andrew Topsfield, Court Painting at Udaipur: Art under the patronage of the Maharanas of Mewar, 2002, p. 144, figs. 165-166. The intention may have been to mock this vastly overweight and rebellious thakur, but the artist manages to imbue him with a certain dignity. As in our portrait of Jaijairam, Baba Bharath Singh is painted with more careful attention to the modelling of flesh than was normally the case in Udaipur at this period.

Andrew Topsfield has charted the careers of various Mewar court musicians, through their representations on inscribed paintings, in his article

“The Kalavants on their Durrie: Portraits of Udaipur Court Musicians, 1680-1730”, in Rosemary Crill, Susan Stronge and Andrew Topsfield (eds.), Arts of Mughal India: Studies in Honour of Robert Skelton, 2004, pp. 248-263. While these famous named musicians sit decorously in the presence of the Rana, our anonymous priestly musicians vigorously sing and play with an unbridled energy that matches the intense meditation of the devotees.

Provenance:

Sotheby’s London, 8th April 1975, lot 116 Private English Collection

References:

1. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ramanandi_ Sampradaya.

2. Anna L. Dallapiccola, Dictionary of Hindu Lore and Legend, 2002, p. 162.

3. Ibid.

4. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ramanandi_ Sampradaya.

5. Dallapiccola, 2002, p. 162.

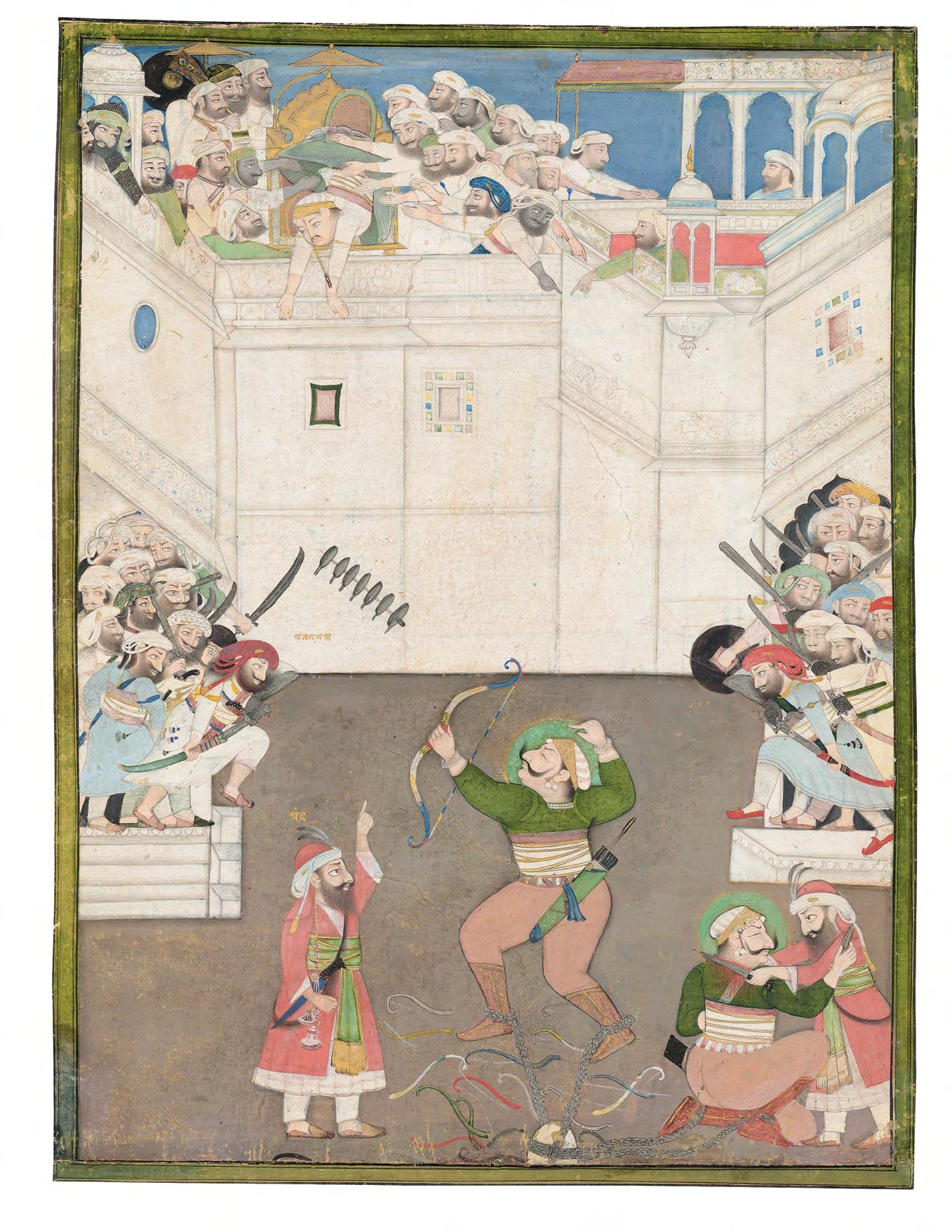

heiGht: 29 cm

Width: 22 cm

Ink on paper.

This is the preparatory drawing for the painting of the same subject published in the next catalogue description, cat. no. 23, which is inscribed on the reverse in devanagari, “By the hand of the painter Nathu Ram”. This drawing, which is identical in composition to the painting, is no doubt by the same hand, that of Nathu Ram, the son of Ala Bagas and a close follower of Chokha, the great artist who worked with his father Bagta at the court of Devgarh. The treatment of the eyes is a distinctive trait of Chokha that was originally developed by Bagta.

The discovery of a preparatory drawing for the exactly matching painting is indeed fortunate. A comparison of the two shows how closely the finished painting keeps to the original conception, but is fleshed out with further details, such as windows in the fortress walls and platforms for the hordes of aggressive soldier-spectators. In the painting, the scene is greatly enriched by the addition of colour, contouring and volume. However, the drawing allows us to appreciate the confident lines by the sure hand of a master artist and it is fascinating to study his steps from initial conception to a completed work of art.

Within the open courtyard strewn with broken bows and chained to a boulder, Prithviraj Chauhan fires the final arrow that kills Muhammad Ghori. This sets off a wild commotion with Ghori’s courtiers, and the ranks of soldiers burst out of their enclosures to exact revenge.

For a full discussion of the scene and the story of Prithviraj Chauhan, see the following catalogue entry, cat. no. 23.

iNdia (udaiPur), circa 1820

By Nathu ramheiGht: 29 cm

Width: 22 cm

Opaque watercolour heightened with gold on paper.

Inscribed on the reverse in devanagari:

chataro nathu ram ki hath kalam

“By the hand of the painter Nathu Ram”.

Within the open courtyard strewn with broken bows and chained to a boulder, Prithviraj Chauhan fires the final arrow that kills Muhammad Ghori. This sets off a wild commotion with Ghori’s courtiers, and the ranks of soldiers burst out of their enclosures to exact revenge. However a lone figure, that of Prithviraj Chauhan’s court poet Chand Bardai, subdues the already blinded hero and proceeds to cut his throat.

Prithvi Raj III, commonly known as Prithviraj Chauhan, was a king of the Hindu Chauhan dynasty, who ruled the twin kingdoms of Ajmer and Delhi in the latter part of the twelfth century.1 According to the Prithvirajaraso, an epic poem composed by Chand Bardai, the Chauhan clan was part of the Agnivanshi Rajputs who derived their origins from the sacrificial fire pit of Agni. Chauhan was the last independent Hindu king to sit upon the throne of Delhi before he was finally defeated by the

Muslims.2 He controlled much of present day Rajasthan and Haryana, and unified the Rajputs against Muslim invasions.

Prithviraj Chauhan defeated the Muslim ruler Shahabuddin Muhammad Ghori in the First Battle of Tarain in 1191 and set him free as a gesture of mercy. Ghori attacked again the next year and Prithviraj was captured at the Second Battle of Tarain in 1192. Ghori took Prithviraj to Ghazni, where Prithviraj was cruelly blinded by red hot pokers.3

Legend has it that in an archery contest, Chand Bardai gave Prithviraj the physical location of Ghori in the arena by reciting a poem with the phrase “Ten pole measures, twenty four arms’ length and eight fingers’ width away, is seated the Sultan, do not miss him now, Chauhan”. As Ghori ordered the show to start, Prithviraj located him by the sound of his voice and the poem’s precise measurements, and shot him dead.4 Prior to the denouement, Prithviraj had already displayed his prowess by shooting through iron plates struck by a sword, locating their position by sound alone, a feat which much impressed Ghori. In this multiepisodic painting, we see the iron plates skewered on an arrow, Chand Bardai revealing Ghori’s position through the poem, Ghori collapsing with an arrow through his forehead, and at the bottom right, the poet and Prithviraj killing each other, their final act to avoid being slaughtered by the Ghorids.

The heroic act of Prithviraj Chauhan is lauded throughout Rajasthan to this day. For Mewar paintings depicting Prithviraj with a bow and arrow, see Molly Emma Aitken, The Intelligence of Tradition in Rajput Court Painting, 2010, pp. 239-240, figs. 5.31, 5.33, 5.36. For a Devgarh depiction of Chauhan shooting Ghori, see Milo Cleveland Beach and Rawat Nahar Singh II, Rajasthani Painters

Bagta and Chokha: Master Artists at Devgarh, 2005, p. 13, fig. 4. A picture of Prithviraj attributed to Chokha is illustrated in Sven Ghalin, The Courts of India: Indian Miniatures from the Collection of the Foundation Custodia, 1991, p. 75, no. 74. The present painting is referenced by Andrew Topsfield in Court Paintings at Udaipur: Art under the patronage of the Maharanas of Mewar, 2001, pp. 233-234.

Nathu Ram was the son of Ala Bagas and a close follower of Chokha. The treatment of the eyes is a distinctive trait of Chokha that was originally developed by Bagta. The light fuzzy beards together with the large expressive eyes gives the composition a greater sense of emotion as seen in the distress of Ghori’s courtiers and soldiers.

References:

1. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ Prithviraj_Chauhan.

2. Ibid.

3. Ibid.

4. Ibid.

iNdia (udaiPur), circa 1930

heiGht: 30.2 cm

Width: 26 cm

Opaque watercolour heightened with gold on paper.

This unusual painting depicts the lineage of the Sisodia dynasty, the rulers of Mewar. The Maharanas of Mewar are the descendants of the epic hero, Rama, and the sun god, Surya. Twenty-two rulers surround a crest containing a representation of Surya on a flag held by two warriors, a Bhil tribesman on the left and a Rajput on the right. Above is a lingam in a yoni, surmounted by a sword flanked by acanthus leaves. The motto written in devanagari reads:

Jo drirha rakhe dharma koun tihin rakhe katar

“The almighty protects those who stand steadfast in upholding righteousness”.

To the top left corner, Rama and Sita sit nimbate and enthroned, flanked by Lakshmana, Bharata and Shatrughna, while Rama’s feet are massaged by a kneeling and devoted Hanuman. The golden throne has a cusped back surmounted by a jewelled parasol and lion front feet. All four brothers wear crowns and carry bows; Bharata and Shatrughna wave chowries (flywhisks); Hanuman’s golden mace is placed on the ground beside him and he also wears a crown.

To the top right corner is fourarmed Durga riding on her lion through the countryside past a lingam and yoni set amidst the grasses. She is followed by Nandi

bull, the mount of Shiva. In the sky above is Brahma riding on his hamsa. A devotee, who is probably a Mewar ancestor as his attendant holds an honorific parasol over him, supplicates the goddess in prayer as she approaches.

At the centre within an oval cartouche is Eklingji, the presiding deity of Mewar, a form of Shiva depicted in black marble as a four-faced lingam (caturmukhalinga) surmounted by an encircling gold snake and placed on a rectangular yoni. From the tier of gold parasols above trickle lustrations onto the jewelled and garlanded god. White blossoms float in the waters of the black marble yoni. The temple complex of Eklingji is located 22 kilometres north of Udaipur.

The Maharanas of Mewar may be identified in

a clockwise direction from the top centre as Udai Singh (who reigned from 1540), Pratap Singh (1572), Amar Singh I (1597), Karan Singh (1620), Jagat Singh (1628), Raj Singh I (1652), Jai Singh (1680), Amar Singh II (1698), Sangram Singh (1710), Jagat Singh II (1734), Pratap Singh II (1751), Raj Singh II (1754), Ari Singh (1761), Hamir Singh (1773), Bhim Singh (1778), Jawan Singh (1828), Sardar Singh (1838), Sarup Singh (1842), Shambhu Singh (1861), Sajjan Singh (1874), Fateh Singh (1884) and Bhupal Singh (reigned 1930 to 1955).

Judging by Bhupal Singh’s youthful appearance in comparison with the white-haired Fateh Singh standing next to him, this painting must have been prepared for him early in his reign.

We would like to thank Andrew Topsfield for his expert advice.

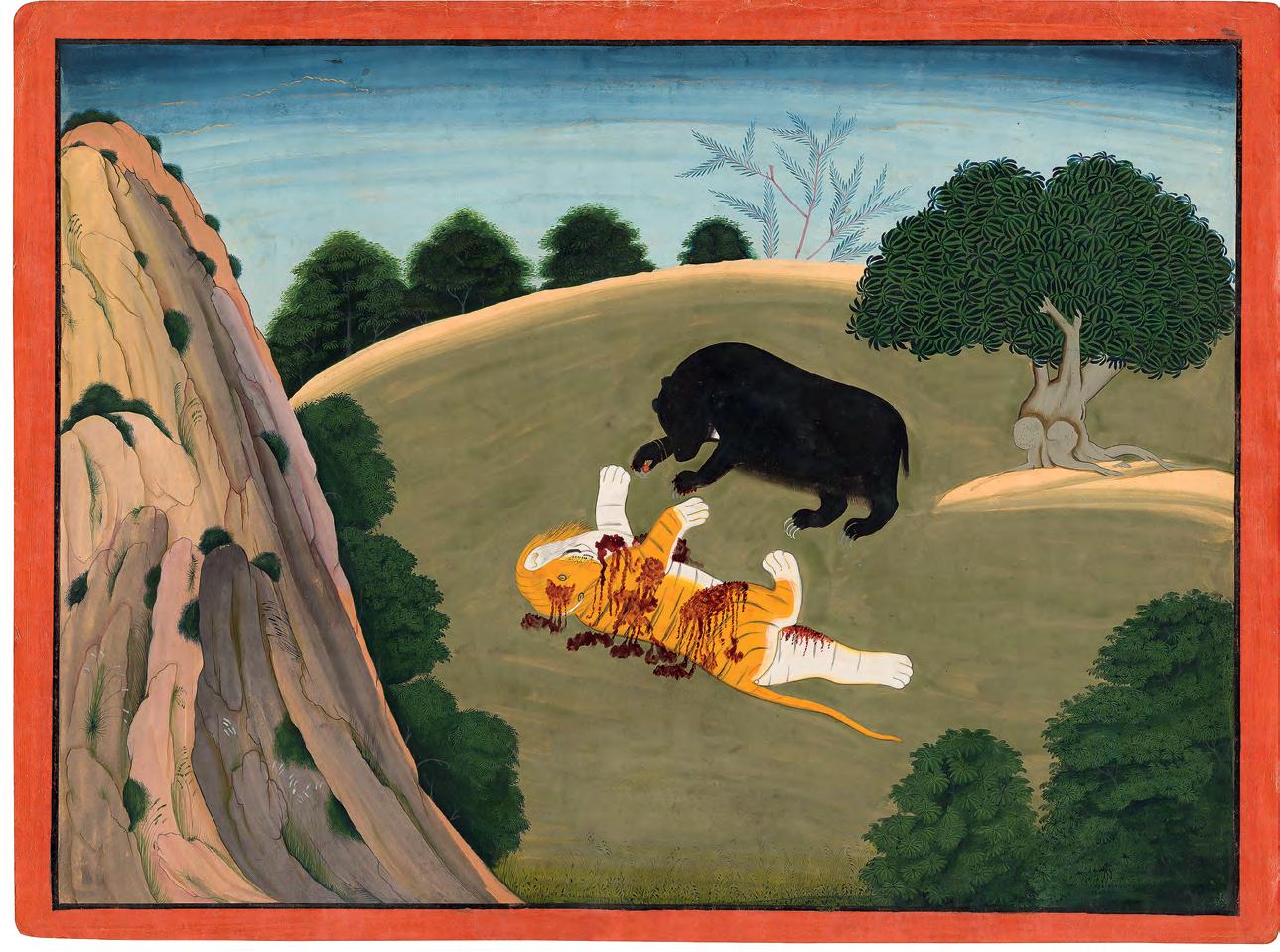

iNdia (Basohli), 1760-1765

attriButed to fattu, the eldest soN of maNaku

folio: heiGht: 30.8 cm Width: 41.2 cm

miNiature: heiGht: 28 cm Width: 38.3 cm

Opaque watercolour heightened with gold on paper.

An illustration from a Bhagavata Purana series.

The main inscription in devanagari on the verso is the second half of a verse followed by a chapter colophon in black and red. The verse is Bhagavata Purana, Book X, chapter 56, verse 14:

“[A lion killed Prasena and his horse and took the jewel. But when the lion] entered a mountain cave he was killed by Jambavan, who wanted the jewel.”

The scribe treats this as the final verse of a chapter in the Syamantaka Upakhyana (The Tale of the Syamantaka Jewel) and adds the number “107”, which is presumably the verse number in that tale. However, the inscription on the left confirms that the verse is indeed from chapter 56 of the Bhagavata Purana and tells us the painting is number 229? [the final number is unclear]. The inscription to the top is in takri and gives the same second half of verse 14 as the main Sanskrit inscription, but with a different number, “218”.

On the swell of a bleak plateau edged by forests, next to the tumbling rock formations of a steep mountain face sparsely dotted with moss and grass, Jambavan, the King of the Bears, has killed a lion and seized the Syamantaka jewel. The lion, depicted as often in Indian

miniatures with stripes like a tiger (sher being the interchangeable name of the two great beasts), lies on its back with twisted head and broken neck, bleeding profusely from multiple wounds. Jambavan triumphantly holds the glittering gem in his razor-sharp claws that have inflicted such damage on his powerful opponent, the gold chain of the precious stone now looped casually over his wrist.

The priceless Syamantaka jewel is a gift from the sun god Surya to his close friend Satrajit. Such is its lustre that when Satrajit walks down the street, the citizens of Dvaraka find it impossible to look at him and believe that Surya himself has arrived. At his opulent home, Satrajit installs the jewel in a brahman shrine where it produces eight bharas of gold a day. Krishna once asks Satrajit to present the jewel to Ugrasena, the Yadava king, but Satrajit, addicted to wealth, declines without reflecting on what his refusal might mean.1 As Linda Leach observes, the Syamantaka jewel is a source of great contention that changes hands several times by gift or seizure, and is variously a symbol of avarice, generosity or atonement.

One day, Satrajit’s brother, Prasena, borrows the jewel and wears it around his neck as he goes hunting in the forest. The lion kills both Prasena and his horse and tears off the jewel before he is killed in

turn by Jambavan who covets the great gemstone. Returning to his mountain cave, Jambavan gives it to his baby son to play with. Unable to locate Prasena, Satrajit spreads the rumour that his brother has been killed by Krishna in order to obtain the jewel. Krishna sets off with a team to clear his name of this libellous smear and retraces Prasena’s path to the forest where they find Prasena’s body and that of his horse. Then, on the side of the mountain they find the lion’s corpse. Leaving his entourage outside, Krishna enters the cave where he sees the child playing with the jewel and he is just about to take it when Jamabavan rushes at him in a fury and a titanic battle lasting twenty-eight days ensues.2

Despite his immense power and fighting skills, Jambavan is no match for Krishna. With ebbing strength and aching limbs, he realises that his opponent is none other than Vishnu. As a devotee of his previous incarnation, Rama, Jambavan bows down to be blessed by the touch of Krishna’s hand. When Krishna explains that he seeks the jewel in order to clear a false accusation, Jambavan happily offers not only the jewel but his daughter, Jambavati, in marriage. Upon his return to Dvaraka, Krishna summons Satrajit to an assembly, announces the retrieval of the jewel, describes the

circumstances of its loss and recovery, then presents it to the remorseful Satrajit. Deeply ashamed of imputing vile motives to Krishna and misreading the whole situation due to his own incessant craving for wealth, Satrajit decides to appease Krishna by offering him both the jewel and the hand of his daughter, Satyabhama, “a jewel among women”. Krishna marries Satyabhama but refuses the gem, saying that Satrajit should keep it as a devotee of Surya. Of all the protagonists in this convoluted tale, Krishna is the only one who has no desire for the jewel, but the adventure rewards him with two beautiful wives, Jambavati and Satyabhama.

Provenance:

Mrs F. K. Smith, sold at Sotheby’s, London, 1st February 1960, lot 53

The Anthony Hobson Collection

A prodigy in his field, appointed Head of Sotheby’s Book Department at 27, Anthony Hobson (1921-2014) was the world’s greatest authority on Renaissance bookbinding. Academic honours were showered on him but his pre-eminence in the book world was sealed by his presidency of the Internationale de Bibliophilie from 1985-1999, where his patrician elegance, charm, command of languages and profound scholarship made him a magisterial figure. Greatly informed by the taste of his wife, Tanya Vinogradoff, granddaughter of the painter Algernon Newton, R.A., his collection ranged with confidence across periods and cultures, testament to the exceptional life and mind of the man singled out by Cyril Connolly as one of the most impressive scholar aesthetes of the day.

1. The story is taken from Edwin F. Bryant (trans.), Krishna: The Beautiful Legend of God (Srimad Bhagavata Purana, Book X), 2003, chapter 56, pp. 240-244.

2. Four paintings from this series are in the Chester Beatty Library, Dublin, including the one where Krishna battles Jambavan in his cave (inv. 68.15). This is illustrated in Linda York Leach, Mughal and Other Indian Paintings from the Chester Beatty Library, 1995, vol. II, pp. 1052-1053, cat. no. 11.51.

ceNtral iNdia (datia), 1770-1775

heiGht: 22.4 cm

Width: 23.4 cm

Opaque watercolour heightened with gold on paper.

An illustration to the Sat Sai of Bihari.

Inscribed in red and white devanagari to the top of the very dark blue border with the verse describing the scene and numbered “501” in the left border.

The doha (couplet) identifies the nayika (heroine) as a proshita-patika, svakiya, meaning she who is singlemindedly devoted to her husband who has gone on his travels. Here, her friend, the sakhi, addresses another friend thus:

Piya kai dhyaan dharai dhare rahi vahi hai naar

Aapu aapu hin aarasi lakhi reejhati rijhwaar

“See, she is so completely absorbed in thoughts of her absent lover that she is beginning to imagine that it is he who is gazing at her from the mirror. Delighted with this thought she seems to be falling in love with herself.”

The Sat Sai or “Seven Hundred” couplets (1662) by Bihari Lal is a Hindi poem that presents a series of the states of lovers like the Rasikapriya of Keshav Das (1581). Bihari Lal was a late-seventeenth century poet at Amber and at the court of Shah Jahan. His masterpiece the Sat Sai is in the tradition of religious texts exploring the romance of Radha and Krishna, containing couplets on love, devotion, and moral lessons. Although some of the couplets of the poem are in praise of Krishna, other parts refer to unidentified lovers. The collection of miscellaneous

verses by Bihari has been grouped together by various commentators and translators under different heads.

The verse bears no. 583 in Jagannath Ratnakara’s classic commentary, the Bihari Ratnakara. In K. P. Bahadur’s 1990 translation for Penguin Classics, Bihari: The Satasai: Seven Hundred Love Poems it is given as verse 154 on p. 101 and is classified under the heading of “Love”. Bahadur’s translation may be read alongside ours, to enhance our appreciation of the nuanced interpretation offered by the painter, which is a vivid visual realisation of the verse:

“What one of her companions said to another: She dotes on him so much that when she looked into the mirror the poor fool imagined herself to be the lover, and remained fascinated with her own reflection!”

The scene unfolds within a hexagonal white marble pavilion, open on three sides to allow the viewer in through the arched portico. The three windows in the back walls are covered with bamboo chick blinds; rolled cloth blinds may be lowered for further privacy. The exquisite red velvet blinds embellished with gold cloud bands that would have covered the front arches are hoisted up for the viewer to see, and to overhear. The heroine is seated to the left, mesmerized by her reflection, while the commentators or gossips discuss the predicament of the heroine from the other side of the pavilion. The sakhi points to the nayika across the gulf created by the blank central arch signalling their distance from her isolation, while the blank space also indicates the absence of the hero

or nayaka. The setting is a walled garden with plantains in boxed flower beds. Dense trees behind the white pavilion wall offer even greater seclusion. As none of these visual details are described by Bihari, the painter has added a layer of meaning to the verse when translating text to image, while the viewer adds further layers as we simultaneously gaze, listen and interpret.

For other examples of this Sat Sai series, see Stella Kramrisch, Painted Delight: Indian Paintings from Philadelphia Collections, 1986, pp. 102 and 178, no. 95; Stan Czuma, Indian Art from the George P. Bickford Collection, 1975, no. 75; Stuart Cary Welch and Milo Cleveland Beach, Gods, Thrones and Peacocks, 1965, no. 43. According to Welch and Beach, Datia in Bundelkhand was granted as a fief to Bhagwan Rao, the son of Birsingh Deo of Orchha, in 1626. A Ragamala of the early eighteenth century may be from here, while inscribed works are known from the reign of Rao Indrajit, which combine Mughal with earlier Central Indian traditions. Portraits of Rao Shatrujit (1762-1802) during whose reign the present painting was most probably executed, are found in N. C. Mehta, Studies in Indian Painting, 1928.

The series is freshly evaluated in Konrad Seitz, Orchha, Datia, Panna: Miniaturen von den rajputischen Höfen Bundelkhands 1580-1820, Sammlung Eva und Konrad Seitz, vol. II, 2015, nos. 59.1-59.10 and p. 222.

Maggs Bros. Ltd, London, Bulletin No. 14, Vol. IV, part 2, December 1968, p. 90, no. 78. Collection of Asbjorn Lunde (1927-2017), New York

ceNtral iNdia (datia), 1770-1775

heiGht: 22.3 cm

Width: 23.4 cm

Opaque watercolour heightened with gold on paper.

An illustration to the Sat Sai of Bihari.

Inscribed in red devanagari to the top of the very dark blue border with the verse describing the scene and numbered “589” in white numerals in the left border.

The doha (couplet) identifies the nayika (heroine) as a svadhina-patika, meaning she who has her husband completely under her control. Here her friend, the sakhi, addresses her thus:

Tunhaayi sab tol mein rahi ju saut kahaayi Sutain ain chi piyu aapu-tyaun kari adokhil aayi

“Your rival (saut=co-wife) was always suspect in our circle, and was seen as a spell-caster (witch-like, using spells and charms etc.)

But ever since you have come, we see that your husband is totally devoted to you: the result? No suspicion

remains attached to your saut now; she is blame-less.”

The Sat Sai or “Seven Hundred” couplets (1662) by Bihari Lal is a Hindi poem that presents a series of the states of lovers like the Rasikapriya of Keshav Das (1581). Bihari Lal was a late-seventeenth century poet at Amber and at the court of Shah Jahan. His masterpiece the Sat Sai is in the tradition of religious texts exploring the romance of Radha and Krishna, containing couplets on love, devotion and moral lessons. Although some of the couplets of the poem are in praise of Krishna, other parts refer to unidentified lovers. The collection of miscellaneous verses by Bihari has been grouped together by various commentators and translators under different heads.

The verse bears no. 348 in Jagannath Ratnakara’s classic commentary, the Bihari Ratnakara. In K. P. Bahadur’s 1990 translation for Penguin Classics, Bihari: The Satasai: Seven Hundred Love Poems it is given as verse 263 on p. 143 and is classified under the heading of “The Other Woman” or “Another Woman”. Bahadur’s translation may be read alongside ours:

“What the newly-wed woman’s companion said to her:

When everyone saw him irresistibly drawn to that co-wife of his they dubbed her an enchantress; but ever since you’ve snatched him away for her She’s rid of that infamy!”

In the painting, the triumph of the heroine is clear. She is regally seated on a throne-like basket chair with a cushion, while her husband stands obediently behind her with a gormless expression on his face as he imitates her gesture exactly. The sakhi faces her to laud her with compliments, though laced with a healthy dose of sarcasm as now the title of infamous enchantress must be transferred to her. The husband, the heroine and the confidante form a tightly-knit group of three while behind them, isolated to the right, the defeated rival co-wife sits glumly in a European style chair that does not look particularly comfortable.

Two marble pavilions, each with three arches and three niches each containing a long-necked vase (surahi), form the backdrop and continue the symbolism. The surahi within the niches function as lingam and yoni references, while the open blinds above the niches and arches in the pavilion behind the defeated co-wife suggest that, at first, there

were three equal players in the game of love and the competition was open to all who had a chance. Even the husband had a chance to escape domination. By the time we come to the pavilion on the left behind the triumphant svadhina-patika, the blinds on each side are drawn and there is only one central niche proudly displaying the surahi within. The winner takes it all!

For other examples of this Sat Sai series, see Stella Kramrisch, Painted Delight: Indian Paintings from Philadelphia Collections, 1986, pp. 102 and 178, no. 95; Stan Czuma, Indian Art from the George P. Bickford Collection, 1975, no. 75; Stuart Cary Welch and Milo Cleveland Beach, Gods, Thrones and Peacocks, 1965, no. 43.

According to Welch and Beach, Datia in Bundelkhand was granted as a fief to Bhagwan Rao, the son of Birsingh Deo of Orchha, in 1626. A Ragamala of the early eighteenth century may be from here, while inscribed works are known from the reign of Rao Indrajit, which combine Mughal with earlier Central Indian traditions.

Portraits of Rao Shatrujit (1762-1802) during whose reign the present painting was most probably executed, are found in N. C. Mehta, Studies in Indian Painting, 1928.

The series is freshly evaluated in Konrad Seitz, Orchha, Datia, Panna: Miniaturen von den rajputischen Höfen Bundelkhands 1580-1820, Sammlung Eva und Konrad Seitz, vol. II, 2015, nos. 59.1-59.10 and p. 222.

Provenance:

Maggs Bros. Ltd, London, Bulletin No. 14, Vol. IV, part 2, December 1968, p. 91, no. 79.

Collection of Asbjorn Lunde (1927-2017), New York

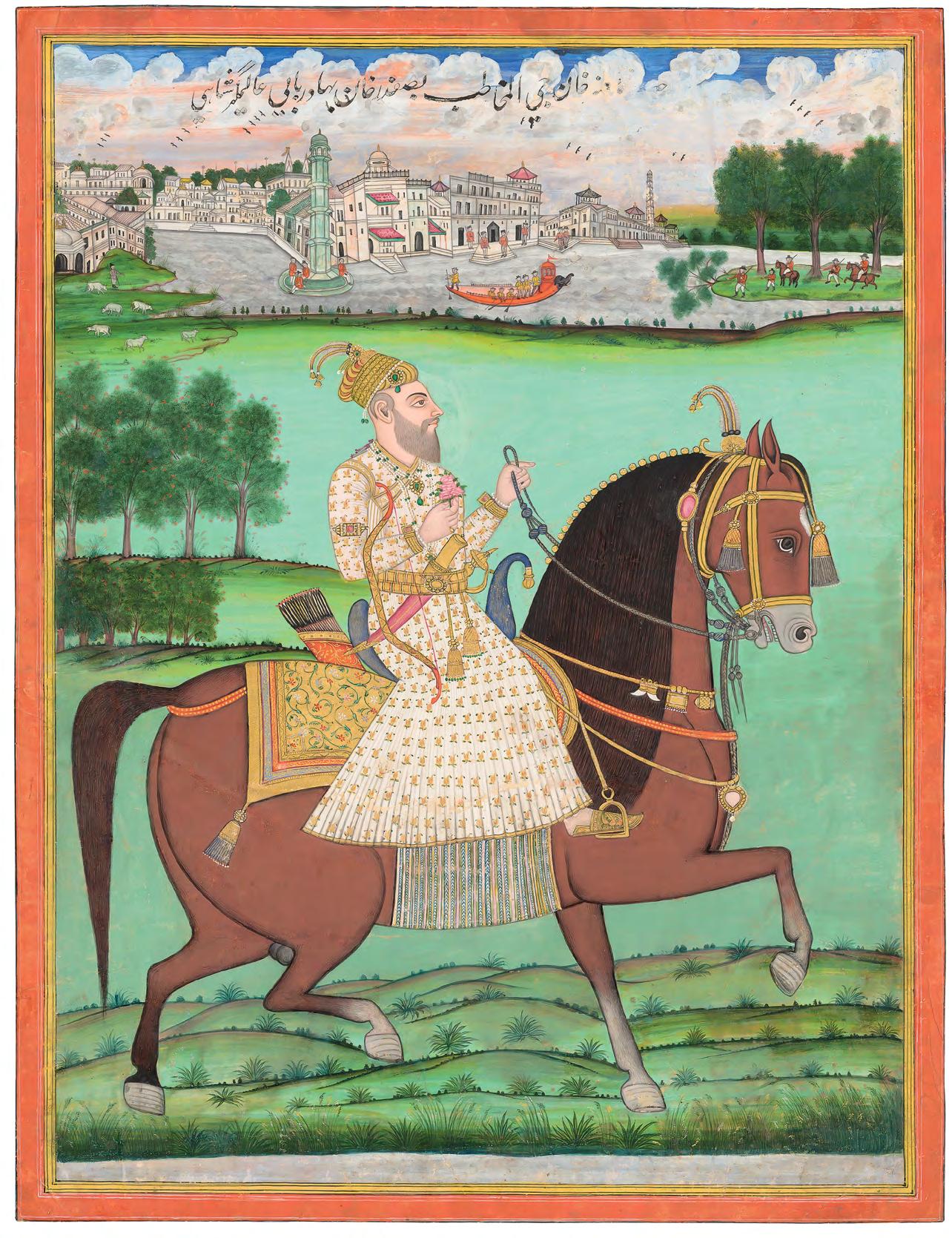

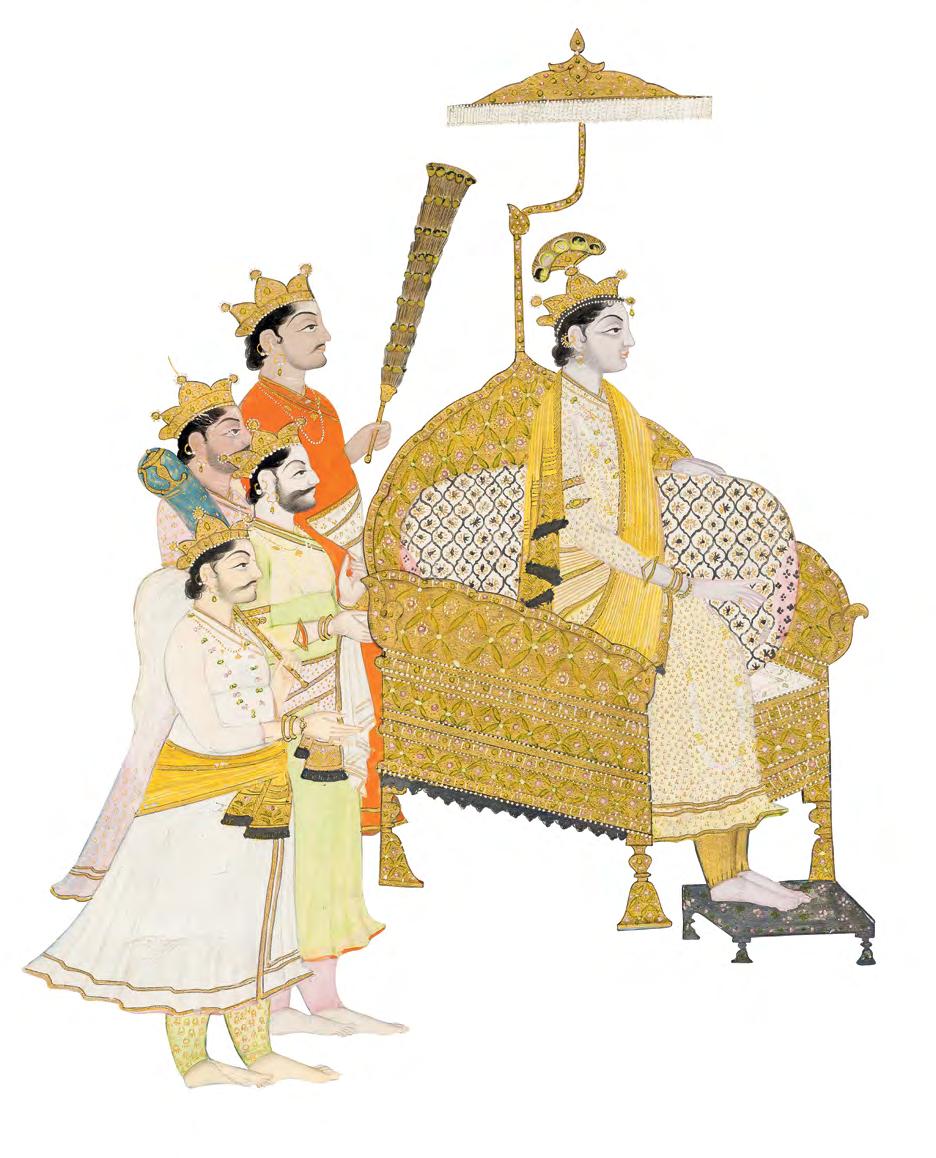

iNdia ( jaiPur), 1800-1820

folio: heiGht: 39.8 cm Width: 29.4 cm

miNiature: heiGht: 26.5 cm Width: 18.5 cm

Opaque watercolour heightened with gold on paper.

Possibly Madhumadhavi ragini from a Ragamala series.

Dark clouds gather as a thunderstorm approaches. Krishna and Radha embrace in front of a pavilion on the carpeted terrace of a palace. They look up at the sky and point to the lightning that ominously streaks the edges of the clouds with wavy lines of gold. The rain drops have not yet begun to fall but it is only a matter of time before the clouds roll swiftly towards them, so they have begun to retreat into the safety of the palace through the cusped arches on the left.

Two attendants standing in conversation beneath the rolled pavilion awnings hold morchals (peacock feather fans). A third attendant is about to offer Krishna some pan (betel) from a gold and gem-set pandan and dish, but her attention has evidently been seized by a sudden clap of thunder and a brilliant flash of lightning. She twists around excitedly, in a dancing contrapposto, to gesture towards the sky. A pair of peacocks perched calmly on the blue and gold balustrade decorated in the striking palette of Jaipur enamels, and two pairs of birds nestling in the trees beyond, echo Krishna and Radha’s warm embrace as symbols of love. Unlike the gopis, the birds remain unperturbed by the approaching storm. For them, there is still plenty of time to find shelter to sit out the coming rain.

Robert Del Bonta has suggested that this un-inscribed album leaf may represent Madhumadhavi ragini from a Ragamala series. The way the figures point to the lightning is essential to the usual depictions of this ragini. Peacocks are also a normal feature of Madhumadhavi, though they are often shown fluttering or crying in excitement as the storm gathers while flocks of other birds such as Sarus cranes take flight into the darkening sky.1 In the present picture, the peacocks simultaneously function as symbols of Krishna, reinforcing the iconography of his peacock feather crown and the morchals held by the gopis.

The painting is organised with an elaborate basement storey. The artist suggests real depth as we can see well inside the entrance at its centre and into the corner of the angled pavilion on the upper terrace. The edge of the terrace projects over the lower storey, cantilevered by means of a row of supporting brackets. The painting is mounted on an album page with two inner margins of floral cartouches surrounded by a wide yellow border of delicate floral sprays in the Mughal style.

In a Hindi verse by the poet Paida found on a Ragamala series dated 1709 from Amber, the earlier capital of the rulers of Jaipur, Madhumadhavi ragini is described thus: