Exploring the Catholic Intellectual Tradition SeSquicentennial iSSue edited by robert p. imbelli spring 2013 Living Faith for the Journey THE CHURCH IN THE 21 CENTURY CENTER FALL 2017 A Catalyst and Resource for the Renewal of the Catholic Church FALL 2016 at Work ConsCienCe A Catalyst and Resource for the Renewal of the Catholic Church SPRING 2017 FORMING CONSCIENCE the vocations of religious and the ordained th in the e t e ter grace and commitment: the vocations of laity, religious, and ordained THE CHURCH IN THE 21ST CENTURY CENTER SPRING/SUMMER 2022 FAITH IN ACTION Around the World THE CHURCH IN THE 21ST CENTURY CENTER SUMMER 2019 OUR CHURCH REVITALIZING A Hope to Share Young Adults and Our Church FALL 2018 c21 resources spring 2020 THE CHURCH IN THE 21ST CENTURY CENTER SPRING/SUMMER 2020 CATHOLIC PARISHES GRACE AT WORK Handing on the Faith SeSquicentennial iSSue a catalyst and resource for the renewal of the catholic church fall 2012 c21 resources spring/summer 2021 THE CHURCH IN THE 21ST CENTURY CENTER SPRING/SUMMER 2021 we are one body Race and Catholicism A Catalyst and Resource for the Renewal of the Catholic Church SPRING 2016 The Treasure of Hispanic Catholicism h church in the 21 cent ury center the eucharist: at the center of catholic life A Catalyst and Resource for the Renewal of the Catholic Church Our Faith Our Stories FALL 2015 Catholi C Families Carrying Faith Forward THE CHURCH IN THE 21 CENTURY CENTER SPRING 2018 OF FRIENDS THE GIFT living catholicism Roles and Relationships for a Contemporary World edited by michael himes a catalyst and resource for the renewal of the catholic church fall 2013 SESQUICENTENNIAL ISSUE THE CHURCH IN THE 21ST CENTURY CENTER WINTER 2022/2023 A Catalyst and a Resource for Renewal of the Catholic Church

The Church in the 21st Century Center is a catalyst and a resource for the renewal of the Catholic Church.

C21 Resources, a compilation of the best analyses and essays on key challenges facing the Church today, is published by the Church in the 21st Century Center at Boston College, in partnership with publications from which the featured articles have been selected.

c 21 resources editorial board

Patricia Delaney

Karen Kiefer

Peter G. Martin

Jacqueline Regan

O. Ernesto Valiente

managing editor

Lynn M. Berardelli

the church in the 21 st century center Boston College

110 College Road, Heffernan House

Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts 02467

bc.edu/c21 • 617-552-0470 church21@bc.edu

©2023 Trustees of Boston College

on the cover

A collage of past C21 Resources magazine covers. All issues are available digitally at: bc.edu/c21resources

THE CHURCH IN THE 21ST CENTURY CENTER 20 YEARS

dear friends :

DI remember it like it was yesterday, picking up the morning newspaper and reading about the formation of The Church in the 21st Century (C21) Initiative, announced by University President William P. Leahy, S.J. It was 2002, the sexual abuse crisis was unfolding in the Catholic Church, and Boston College was the first Catholic academic institution in the country to come forward to offer resources for examination and renewal. As a Boston College alumna and mother, handing on our Catholic faith to four young daughters, I was so grateful and proud.

Fr. Leahy outlined the important work of the Church to respond compassionately to victims and to change its internal structures to ensure that abuse and cover-ups would never happen again. It was Fr. Leahy’s hope that Boston College, through the C21 Initiative, could provide a forum and resources to help the Catholic community—lay men and women, priests, and bishops—transform the crisis into an opportunity for renewal.

During the months ahead, Fr. Leahy’s vision began to take root. The C21 Initiative offered symposia, lectures, conferences, and publications to help the Church navigate through the crisis. The initiative was a success and became a permanent center at the University in 2004, committing to be a catalyst and resource for renewal of the Catholic Church in the United States.

Decades later, many members of the Boston College community and beyond have remained committed to the promise of the C21 Center and our Church. These individuals have given their time and gifts to help create many resources: videos and podcasts with millions of views; an awardwinning book series and the bi-annual C21 Resources magazine; thousands of commissioned and reshared articles; and innovative programming models adopted by colleges, schools, and parishes across the country and around the world.

As we mark the twentieth anniversary of the C21 Center, we remain as committed as ever to the work of revitalizing the Church. Yes, there are challenges ahead; however, as Fr. Leahy reminded us when he founded the C21 Initiative, “During the past 2,000 years, the Catholic Church has adapted and changed to meet a variety of challenges. So as we strive to heal and to think and act anew, we must recall that God does not leave us orphans, and that the Spirit is working among us always.”

So, with God’s grace and the Spirit working among us, into the future we go!

Karen K. Kiefer Director, The Church in the 21st Century Center karen.kiefer@bc.edu

Explore the digital version of this magazine and additional resources on the issue’s theme page at: bc.edu/c21anniversary20

in this issue: The magazine is divided into four sections highlighting the C21 Center’s focal issues: Handing on the Faith, Roles and Relationships in the Church, Sexuality in the Catholic Tradition, and the Catholic Intellectual Tradition. It contains a collection of commissioned, reprinted, and updated C21 Resources articles, and is filled with information on companion resources developed by the C21 Center over the past 20 years. Our hope is that readers will share these resources far and wide.

14 4 10 26 20 2 The Church in the 21st Century Center Highlights 4 Measuring Parish Vitality Daniel Cellucci 6 Dear Future Church Dennis J. Wieboldt III 8 Share Your Faith Stories Thomas Groome 10 Young People: Temples of the Holy Spirit Casey Beaumier, S.J. 12 Catholic Schools: A Way Forward Melodie Wyttenbach 14 The Treasure of Hispanic Catholicism Hosffman Ospino 16 The Church and Contemporary Challenges Richard Lennan 18 Living Catholicism: A Church in Need of Its People Fr. Michael J. Himes 20 Lighting the Way Joan D. Chittister, OSB 22 Priestly Ministry and the People of God Thomas Groome 24 The Synod: A Transformative Process Sr. Nathalie Becquart, XMJC 25 Women in Ministry: Voices 26 The Joy of Love Gerard O’Connell 28 Thou Shalt: Sex Beyond the List of Don’ts Lisa Fullam 30 Witness to Love Mary-Rose Verret 32 A Wondrous Adventure: The Catholic Intellectual Tradition Fr. Robert P. Imbelli 34 Critical Challenges for Catholic Higher Education Gregory A. Kalscheur, S.J. 36 Finding God in the Catholic Imagination Paul Mariani 38 The Gift of Education and the Intellect Fr. Michael J. Himes 39 Best Practices in Digital Ministry John T. Grosso 32

2002

ϐ Boston College President William P. Leahy, S.J., announced The Church in the 21st Century (C21) Initiative as a two-year effort to examine issues raised as a result of the sexual abuse scandal in the Catholic Church and to provide intellectual and religious resources to serve as a catalyst for renewal. BC was the first Catholic academic institution in the country to begin such a project in response to the crisis.

ϐ A Steering Committee was appointed to chart the direction of the C21 Initiative; a larger Advisory Committee—composed of faculty, staff, alumni, and students—was also appointed to be broadly representative of all segments of the University. The committees were led by Fr. Leahy and its co-directors—the late Robert R. Newton, special assistant to the president, and Mary Ann Hinsdale, associate professor of theology.

ϐ The C21 Initiative launched its first event, a forum at Robsham Theater titled "From Crisis to Renewal: The Task Ahead" (September 18). Twenty years later, over 1,000 events have been sponsored by the C21 Center, both on-campus and online, drawing on the wisdom of BC faculty, students, and renowned experts nationally in the fields of theology, philosophy, history, science, English, business, and the arts.

2003

ϐ Three main foci were identified to guide C21 programs, events, workshops, and publications: Handing on the Faith, Roles and Relationships in the Church and Sexuality in the Catholic Tradition. A fourth, the Catholic Intellectual Tradition, was added in 2005.

ϐ The C21 Center first published C21 Resources, a compilation of the best analyses and essays on the Church's key challenges. To date, 35 issues of the magazine—containing over 600 articles—have been published,

the church in the 21 st century

mailed twice a year to a circulation of 180,000 households. This hallmark publication is a resource employed by individuals, schools, parishes, religious educators, and faith formation programs. An inclusive archive of past issues is available on the C21 Center website. Additional print copies of the publication are distributed by request and free of charge.

ϐ The Boston College Alumni Association hosted Road to Renewal, a series of events hosted nationwide at which Fr. Leahy met with alumni and discussed the Catholic Church and the C21 Initiative.

ϐ The C21 Center established the Episcopal Visitors Program, which engages members of the Catholic hierarchy in conversation about important issues in the Church. Each year, bishops and cardinals are invited to campus to experience life at a Jesuit, Catholic university and to meet with students, faculty, and administrators.

2004

ϐ After hosting over 100 public events, the University announced the C21 Initiative would become The Church in the 21st Century Center, a permanent resource in service to the Catholic Church.

ϐ C21 Online was established to provide adult Catholics with opportunities to grow in faith through online courses and programs. This grant-funded partnership with the Institute for Religious Education and Pastoral Ministry at BC eventually became part of the School of Theology and Ministry in 2008. It is now called STM Online: Crossroads, serving over 1,100 learners annually.

ϐ The C21 Series on Women highlighted the concerns and ideas of women in the Catholic Church. The C21 Center hosted two conferences—“Envisioning the Church Women Want” (spring 2004) and “Creating the Church Women Want” (summer 2006)—which inspired future publications.

2005

ϐ The C21 Center launched the C21 Book Series, compiling content from its conferences, symposia, and publications into a series of books. Fifteen books define the collection, the first of which being Church Ethics and Its Organizational Context

2006

ϐ The first rendition of Agape Latte, BC’s popular faith storytelling series for students, took place. Since its inception, BC has hosted over 130 Agape Latte events on campus.

2008

ϐ The C21 Center expanded its Student Advisory Board, empowering BC students to be stakeholders in the work of the Center in service to the Church. Student Board members help plan on-campus events—including Agape Latte—and meet with members of the faculty, administration, and Church hierarchy. By 2018, the Board grew to over 85 students.

ϐ The C21 Center launched its YouTube Channel. The extensive video and audio archive of events and lectures has attracted over 1.1 million views, with visitors from more than 98 countries.

2009

ϐ The grant-funded initiative “Touchstone for Preaching” was created to help priests and deacons hone their preaching skills. As part of its “Encountering the Gospel: Renewing the Preacher” series, the C21 Center hosted two dozen workshops over a two-year period.

2012

ϐ The Center published two books— Encountering Jesus in the Scriptures and Catholic Spiritual Practices—combining articles and reflections from past issues of C21 Resources magazine with new, expanded content.

ϐ In partnership with the Office of Campus Ministry, the C21 Center

2 c21 resources | winter 2022/2023

century center highlights

established Espresso Your Faith Week, an annual week of over 30 oncampus student events that celebrate Ignatian spirituality and the gift of God working in our lives.

2015

ϐ The C21 Center received an anonymous grant to franchise the Agape Latte program at other colleges and universities nationwide— not just at Catholic, Jesuit institutions, but also at public and secular, private institutions. Eventually, high schools and parishes also adopted the program. Over 120 franchises have launched to date, influencing the faith lives of tens of thousands of students.

2016

ϐ The C21 Center produced the first episode of GodPods, a podcast conversation series discussing key challenges and opportunities facing the Church. Listen to GodPods for free on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, Stitcher, or wherever you get your podcasts.

ϐ In partnership with the Institute for Advanced Jesuit Studies, the C21 Center developed Ever to Excel, a week-long, on-campus summer program for high school students to experience Boston College through the lens of Ignatian spirituality. Undergraduate BC students serve as mentors to the participants throughout the week. To date, 750 high school students from across the country and around the world have participated in the program.

ϐ A two-year faculty seminar, “A Theology of Priesthood for Our Time,” was established to provide the Church with a contemporary theology of priesthood that can guide its recruitment and preparation of candidates and help to address pressing pastoral issues surrounding priesthood in our time. The fruits of this seminar were later published in a compendium, To Serve the People of God: Renewing the Conversation on Priesthood and Ministry

2018

ϐ In the wake of the Pennsylvania grand jury report on clergy sexual abuse, hundreds attended the C21 Center’s forum “Why I Remain a Catholic: Belief in a Time of Turmoil” in Robsham Theater.

2019

ϐ Hundreds attended the C21 Center’s four-part Easter speaker series “Revitalizing Our Church.” Panelists from diverse areas of expertise offered their ideas on how the Church can be a more effective institution, restore its credibility with the faithful, and move forward with the hope of Easter.

ϐ Faith Feeds, a conversation-based faith sharing program for individuals, parishes, and Catholic schools, was launched by the C21 Center. To date, over 200,000 free Faith Feeds facilitation guides have been downloaded from the C21 Center website. A Zoom model of Faith Feeds was offered during the pandemic, providing an opportunity to gather weekly with people from around the world. The online program continues each Friday at 1 p.m. EST.

ϐ In partnership with Paraclete Press, the C21 Center launched the children’s book Drawing God, encouraging children to creatively express how they see God. Authored by the C21 Center’s director, Karen Kiefer, the book inspired the annual World Drawing God Day, an online Drawing God Museum, and curriculum-based projects for parents, parishes, and Catholic schools.

2020

ϐ During the pandemic, the C21 Center, in partnership with the Roche Center for Catholic Education, launched Breakfast with God, an online Sunday morning children’s faith formation show. Hosted by a Jesuit priest and a Catholic preschool teacher, over 80 episodes were livestreamed on Zoom to a community of over 1,000 families. Breakfast

with God downloadable guides are available on the C21 website for parents, religious educators, and Catholic school teachers interested in replicating the program.

ϐ Between 2020 and 2022, as part of the first phase of the Student Voices Project, the C21 Center surveyed 1,500 high school and college students from across the country, asking what their hopes are for the Catholic Church. The Center compiled this data and submitted a report to the Vatican as part of the Synod on Synodality. Now, as part of the second phase of the Project, the Center is actively sharing the free diagnostic tool used in the study with Catholic educators nationwide to help them gauge their students’ faith development.

2021

ϐ More than 200 virtual events were hosted by the C21 Center, nourishing Catholics of all ages during the pandemic.

2022

ϐ The C21 Center, in partnership with the BC Alumni Association, launched Pray It Forward, an opportunity to pray together weekly as a BC community for 15 minutes on Zoom, Wednesdays at 4 p.m. There are currently 700 members in the online community from across the country.

ϐ Lunchtime virtual retreats were offered for the first time by the C21 Center; one during Lent and one during Ordinary Time. Hundreds of people participated, many new to the C21 community.

ϐ The Center developed Mass and Mingle, a new social opportunity for 20- and 30-something Catholics that will be piloted in the Greater Boston area. Once a month, young adults are invited to attend a 5 p.m. Sunday Mass, followed by a one-hour social infused with Ignatian spirituality.

photo credits: Visit this issue's theme page: bc.edu/c21anniversary20

Celebrating 20 Years | ANNIVERSARY ISSUE 3

Parish Vitality

Daniel Cellucci

W

what makes a great parish ? For many Catholics, the answer lies in a series of anecdotal, nostalgic, or sometimes consumeristic statements that speak to what a parishioner might receive or experience. Oftentimes these descriptions are incomplete and can include defensive rationalizations that seek to explain the current state versus what could or should be. Given the breadth of the Church’s reach and history, the “official” definition of a parish, and the standards of what constitute a fruitful one, are likewise broad and abstract. In a relatively stable landscape where resources are abundant, a broad and vague understanding of parish vitality does not present an issue. Unfortunately, the landscape of the last three decades has been anything but stable, which has significant implications on how we understand and support parishes both now and in the future.

Beginning in earnest in the early 1990s, U.S. dioceses, mostly in the Northeast and Midwest, have faced the increasing challenge of adapting a parish footprint that was built for a different time. Along the southern half of the country, immigration and migration has created a different set of challenges and opportunities related to the parish experience. How does a diocese determine where to allocate increasingly scarce financial and human resources? Is a parish’s standing determined by demographics alone? Which parishes “deserve” the best leaders, whether they be clergy or lay professionals? And even in the contexts where financial resources should be available and the larger population is growing, what determines why one parish may thrive and one may barely survive? These are not simply rhetorical questions. They increasingly represent a heartbreaking reality for every level of Church leadership, especially for the people in the pews who often feel surprised and robbed when their parish experiences any forced change, from the need to share a pastor to a potential merger or even closure.

In the last decade, a plethora of apostolates, programs, and resources have emerged to try to equip

parish leaders to achieve increased vibrancy. While these efforts provide helpful strategies and encouragement to attend to various aspects of parish life, often one of the most difficult challenges in parish transformation is convincing parish leaders and parishioners that there are objective standards against which parishes should be evaluated. A lack of understanding of the global mission of the Church, as well as a lack of objective understanding of one’s own parish situation, not to mention the parishes nearby, further exacerbates this barrier to evaluation and the inability to identify what opportunities exist within a given community.

In 2014, Catholic Leadership Institute (CLI) introduced the Disciple Maker Index, a parish survey tool t hat invites parishioners to reflect on where they are in their individual discipleship and their relationship with their parish. As of 2022, the survey has reached over 500,000 Catholics from more than 2,100 parishes in over 50 dioceses, responding in 22 different languages. Because of the nature of survey collection methodology, the respondents skew heavily toward Mass-going Catholics. Since its inception, the survey findings point to one statistically significant determinant when it comes to parishioners’ perceptions of vibrancy: leadership. Across all ministry contexts, parishioners are eleven times more likely to indicate their willingness to recommend their parish to a friend and four times more likely to indicate the parish is helping them grow spiritually if they are likely to recommend their pastor. Other key drivers, such as hospitality, the Sunday worship experience (inclusive of preaching), and the parish’s ability to communicate effectively, are important but are dwarfed in comparison to the perceived effectiveness of leadership.

4 c21 resources | winter 2022/2023

HANDING ON THE FAITH MEASURING

These findings, while clear, create an additional challenge for Church leaders. If the secret to parish vibrancy is having a great leader, where does that leave a U.S. Church that faces an aging and increasingly scarce presbyterate? What implications does that have for lay leadership in parishes? In what areas of parish life does co-responsibility become most important? How, and in what areas, should future priests, deacons, religious, and lay leadership be formed and trained? Without a shared vision for what constitutes parish vitality, this continues to feel like throwing darts in the dark.

Establishing a framework of clear and objective metrics can validate or challenge deeply held beliefs about some of the entrenched narratives that are part of our lived experience. Metrics can help to show what we believe does and does not work. Clarifying and prioritizing the most relevant metrics of parish vitality is not at odds with our call to be relational or with the human experience, nor do metrics limit or seek to replace the work of the Holy Spirit in our parishes. They do, however, create a heightened sense of accountability, which i s essential to any missional organization. If we can come to a shared understanding of what can and should be measured in terms of parish vitality, then we can do a better job of discerning how the Spirit is animating us in our proclamation of the Gospel.

CLI gathered existing frameworks from dioceses that have been used to guide conversation, self-study, and planning for parishes. While many frameworks shared similar categories for the primary functions of a parish, they often also shared a lack of concrete metrics or standards within those categories that would provide a helpful benchmark on vitality. Often, the frameworks relied on the subjective assessment of a body like the pastoral council to assess an area like welcome or outreach.

However, it was encouraging to see the degree of overlap and agreement that existed across dioceses and among parish leaders about what was considered foundational. This led us to ask the question, “If there is

general agreement about what a parish needs to do, what is missing?” As we looked to the examples of parishes displaying vitality in a multitude of contexts, it was not primarily the presence or absence of a foundational ministry that determined vitality but rather the presence or absence of certain behaviors or attributes that defined how these parishes fulfilled those ministries. For example, there was little disagreement that one of a parish’s primary functions is the celebration of the Eucharist. However, a greater determinant of vitality is not simply whether or not the parish celebrates the Eucharist but how the community engages in that worship. Is the worship intentional? Do the lay faithful fully and actively contribute to their responsibility? How well does the parish equip and form those called to lead worship? The old adage that “culture eats strategy for breakfast” seems to apply in the framework regarding which metrics are most relevant for looking at parish vitality.

Synodality creates a great opportunity to continue dialogue on this important question: The question about what makes a parish great is not one that a single bishop or pastor can answer. It requires a deep and consistent listening to the Holy Spirit speaking through the People of God. If parish is not just what we do but who we are, we must continue to dialogue about who we are to each other, who we are together, and who we are together in Christ to the rest of the world. Our continued communal discernment about how we journey together will in and of itself be an expression of our vitality. ■

Daniel Cellucci is CEO of Catholic Leadership Institute, an apostolate providing leadership training and consulting to more than 290 bishops, 2,700 priests, and over 33,000 deacons, religious, and lay leaders in more than 100 dioceses.

This article is adapted from a whitepaper produced by CLI. For more information, contact CLI at: info@ catholicleaders.org.

Read C21 Resources

Catholic Parishes: Grace at Work (Spring/Summer 2020).

Guest Editors: Michael R. Simone, S.J., and Joseph E. Weiss, S.J.

Celebrating 20 Years | ANNIVERSARY ISSUE 5

this issue's theme page: bc.edu/c21anniversary20

photo credits: Visit

SPRING/SUMMER 2020 CATHOLIC PARISHES

AT WORK

If parish is not just what we do but who we are, we must continue to dialogue about who we are to each other… and who we are together in Christ to the rest of the world.

GRACE

Dear FUTURE Church…

Dennis J. Wieboldt III

A

as a candidate for Confirmation at St. Matthias School in Somerset, NJ, I distinctly remember participating in a program known as “Service WorX.” All Confirmation candidates were required to participate in this program, presumably in the hopes of demonstrating the program’s motto: “Faith without works is dead.” Written in bold letters on the back of our program T-shirts, this motto embodied a central tenet of the Catholic faith—to do good works in the world is to be faithful to the Catholic tradition.

Since Pope Leo XIII’s publication of Rerum Novarum in 1891, Catholics have become increasingly cognizant of the Church’s social teaching. Today, most Catholics are likely to recognize the importance of the preferential option for the poor, the protection of human dignity, the respect for the gift of life, and other dimensions of the Church’s social witness. In the United States, attention to Catholic social teaching has become particularly widespread in recent years, especially among students at Catholic colleges and universities. At Boston College, for instance, students can often find innovative courses that apply Catholic social teaching to pertinent issues of economic injustice, racial discrimination, environmental degradation, and more.

Catholics must witness to a faith that does justice in the world. My hope for the future Church, however, is that we also not forget other dimensions of the faith that are equally important. As the American Church in particular continues to minister to the poor, immigrants, women in crisis pregnancies, and others on the margin, I hope that we will also embrace the sacraments, the

richness of the Catholic intellectual tradition, and the Church’s focus on community.

Fortunately, the Church need not choose one path over the other. We need not choose an exclusive emphasis on social issues over an appreciation of the sacraments, nor an exclusive emphasis on the sacraments over the pursuit of social justice. Rather, we must remember what makes the Church the Church, in all of its depth and complexity.

Focusing the Church’s pastoral attention somewhere between these two extremes is not just a personal preference but based on real experience and concrete evidence.

I n 2020, the C21 Center launched the Student Voices Project to better understand how Boston College students understand their faith. Between November 2020 and October 2021, the Project engaged with nearly 550 students through small focus groups and online surveys. In this initial phase of the Project, Boston College students expressed hope that the Church would help them develop a greater understanding of how the Catholic spiritual and intellectual traditions can make sense of their lived experiences.

For example, a majority of respondents expressed their appreciation for Boston College’s distinctive academic programs because they integrate the Church’s spiritual and intellectual traditions with contemporary issues. In many cases, students noted particularly positive experiences with Boston College’s Complex Problems and Enduring Questions courses—multidisciplinary courses taught by faculty in two academic d isciplines that integrate, for instance, faith and reason,

6 c21 resources | winter 2022/2023 HANDING ON THE FAITH

evolutionary biology and biblical narratives, or Catholic theology and neuroscience.

Beyond the Church’s intellectual tradition, the Student Voices Project demonstrated that students desire a sense of community on campus around their faith. Whether involving community-based events after Mass or intentional service programs, respondents repeatedly emphasized the importance of the Church’s understanding of community. Importantly, this emphasis on community was held alongside equally emphatic support for promoting a faith that does justice.

When Pope Francis announced the Synod on Synodality—a major part of his broader plan to create a “listening Church”—the C21 Center placed the Student Voices Project in service of the Synod. With the goal of listening to the experiences of high school and college-aged students from around the United States, the national phase of the Project engaged an additional 1,000 students through online surveys. Hailing from 26 schools in 14 states, over 95% of the respondents to the Project’s national phase were of high school age. This offered the C21 Center a unique opportunity to identify common themes in the hopes of high school and college-aged students.

Not unlike their college-aged peers, high school students expressed a desire for greater understanding of their faith and a sense of meaning in practicing it. Similarly, high school respondents to the Project’s national survey articulated their hope for greater community around their faith, in addition to more direct engagement from Church leaders around pressing social issues.

In both iterations of the Project, students expressed hope that the Church would accompany them in a pastorally responsive way, one that helps them understand what the Church teaches, why the Church believes it, and why (and how) it should matter in their lives. Put more simply, students wanted to talk about difficult issues, not merely be talked to about them.

Placed amidst the backdrop of their emphasis on inclusion and belonging, students who participated in both phases of the Project demonstrated interest in an intellectually and spiritually robust faith that does justice in the world.

As the Synod on Synodality continues, it is critical that we think more intently about the experiences of young people in the Church, not least so that the Church can understand how to accompany the next generation on its faith journey. Though many headlines about young people in the Church are focused on social issues alone, conversations with students at Catholic high schools, colleges, and universities through programs like

the Student Voices Project reveal that the Church must balance the distinctive social, intellectual, and spiritual features of the Catholic faith.

Doing so means witnessing to a faith that does justice, but it also means embracing the sacraments, prayer, the Church’s rich intellectual tradition, and the Church’s unique emphasis on community.

I have great hope for the Church’s future, but our success in witnessing to the full message of the Gospel will be tethered to whether Catholic institutions and “we” the Church remember not to overemphasize some aspects of the Catholic tradition at the expense of others.

Embracing Christ’s exhortation to “make disciples of all nations,” then, requires us to witness to what makes the Church the Church. ■

Dennis J. Wieboldt III is an M.A. candidate in history at Boston College and the co-director of the Student Voices Project. A 2022 graduate of Boston College, he has been a member of the Church in the 21st Century Center’s Advisory Committee for three years.

The Church in the 21st Century Center recently concluded its two-year-long study, the Student Voices Project, of how Catholic high school and college students understand their Catholic faith. Now, as Catholic educators explore new ways to reinforce their mission and Catholic identity, the Center is ready to share its free diagnostic tool, used in the study, to help them learn more about how their students understand their faith.

Are you interested?

Please contact the C21 Center to begin the conversation: church21@bc.edu

To learn more about the Student Voices Project, and read the executive summary and full report that were submitted to the Synod on Synodality, visit: bc.edu/futurechurch.

Celebrating 20 Years | ANNIVERSARY ISSUE 7

“Students expressed hope that the Church would accompany them in a pastorally responsive way, one that helps them understand what the Church teaches, why the Church believes it, and why (and how) it should matter in their lives.”

photo credit : Courtesy of Yiting Chen, Boston College

Share Your Faith Stories

“ so are you excited about your First Holy Communion next Sunday?” asked Nana Peg of her granddaughter Cara. And little Cara went on excitedly about the rehearsal she and her second-grade friends had been through, her cool new outfit, and the great party afterwards in her backyard, adding, “You’re coming, Nana, right?” Peg assured Cara that she wouldn’t miss it for the world and said, “Oh, you’ll have lovely memories, Cara, of your First Communion day; you’ll remember it all your life, as I do.”

Then Nana Peg, beginning with “I remember so well…,” told a great story of her own grand day, and Cara was rapt with attention. Peg reminisced with obvious joy and wound down with, “When I finally received Holy Communion, the first thing I said was ‘Welcome Jesus and thanks for coming to me today.’” “Ah,” said Cara, “that’s what I’ll say to him, too, Nana.”

As I reflect now on my eavesdropping to that lovely round of stories, I’m reminded again of what gifts we all have to share from our personal stories of faith. Indeed, there is probably no more effective way for us to share “the greatest Story ever told”—Christian faith—than through the filter of our personal stories. This is heightened all the more when parents and grandparents share such stories with their children and grandchildren (and surely aunts and uncles, too). Nothing is more effective in evangelizing than the storied witness of Christian faith.

Of course, we will always need effective formal catechesis in our parishes and schools. This is necessary to ensure that we “hand on” (the literal meaning of the Greek katekesis) the whole Christian Story and likewise the great Vision it proposes for living Christian faith— faith that is alive, lived, and life-giving for ourselves and for “the life of the world” (John 6:51). For sure, there is nothing more persuasive than to access that great Story through the personal faith stories we can all share with the rising generations.

If a key strategy for passing on the faith is through our own faith stories, this begs the question of how best to craft such conversation. As Aquinas wisely advised, sharing our faith should ever be done “according to the mode of the receiver.” The heart-engaging power of stories suggests that we can craft our own faith narratives to intentionally lend access to the great Story and Vision of Christian faith.

To return to my eavesdropping, I note well how Nana Peg drew out Cara’s story first before she shared her own. And I propose that there is no better example of such story-to-Story pedagogy than that of Jesus himself. There are innumerable examples of him drawing out people’s stories in the midst of sharing his own great Story—the Gospel of God’s reign. Recall how he crafted his conversation with Nicodemus (John 3), or with the Samaritan Woman (John 4), or with the disciples on the Road to Caesarea Philippi (Matthew 16).

Indeed, it seems as if Jesus almost always began his teaching with some familiar narrative from his listeners’ daily lives. So, the reign of God is like fishermen sorting fish; I bet he was talking to people sorting fish or at least with those familiar with this morning work. Or the reign of God is like a woman baking bread; I imagine him talking to the women at the well. Or note when he was talking to farmers about sowing seeds, and the examples go on. Then, in the midst of such familiar stories from his listeners’ lives, Jesus taught them “with authority” (Mk 1:22) the Story of faith and invited their lived response for God’s reign (Mk 1:15)—God’s Vision for us all. Pedagogically, Jesus was engaging his listeners’ own stories as an entreé into the great Story he had to share.

Though this “story-to-Story” pedagogy is present throughout Jesus’ public ministry, nowhere is it more evident than with the two disciples on the Road to Emmaus (check Luke 24:13-35). Recall how they are leaving

8 c21 resources | winter 2022/2023 HANDING ON THE FAITH

S

photo credit : Courtesy of Lee Pellegrini, Boston College

Thomas Groome

Jerusalem (running away?) for Emmaus—a seven-mile journey. Jesus, now the Risen Christ, approaches, joins their company, and “walks along with them.” For some reason (blinded by their broken hearts at the death of their beloved Jesus?) they don’t recognize him.

Even more amazing, however, is that Jesus doesn’t begin by telling them what to see. Instead, as he walks with them (Pope Francis cites this text as a model of catechetical “accompaniment”), Jesus first draws out their own tragic story of how he was taken and crucified, and now their shattered hopes for a Messiah “to set Israel free” (from Roman rule?).

Only when he has drawn out their own painful story and lost hope does he catechize his version of the great Story of the faith community. So, “beginning with Moses and all the prophets he interpreted for them every passage of Scripture that referred to himself,” and explained how the Messiah had to suffer “so as to enter into his glory.”

Now their own stories and the faith Story are on the table, yet the Stranger still doesn’t tell them what to see but waits for them to put the two together and come to see for themselves. Which they do, after they have offered him hospitality, and he sits with them at the table for “the breaking of the bread.” In that eucharistic moment, they recognize the Risen Christ, whereupon he vanishes from their sight. In many ways, his work was done—they had come to “see” for themselves and thus renewed their own faith. He likely was off to another Emmaus road—as to the dinner table in your family.

Now the two disciples recall how their “hearts were burning as he opened the Scriptures for us.” Would that we can do likewise—to craft the great Story to burn into people’s hearts. Surely the clue to setting hearts afire is that we connect and integrate people’s own stories with the great Story of Christian faith.

I warrant that at least once a day every child asks a question or raises an issue or makes a protest or takes a stand that demands the attention of their caregivers. When this happens, take the time to draw out their “story”—the narrative of what is going on with them or happening to them. Not always but often, we can find an entrée in such moments to share a faith perspective, to sow a seed from our own faith story to reflect the great Story of Christian faith.

In our daily lives there are constant opportunities to share an explicit faith story, as with Nana Peg and Cara; be sure to take them—they are golden for handing on the faith. And there will be implicit faith moments as well, when you are simply encouraging their faith in themselves, in others, in life. Take those opportunities, too.

So, like Nana Peg and that Stranger on the Road to Emmaus, ever try to draw out your child’s own stories first. That will likely lend a clue for how best to craft your personal faith stories as an entrée into the great Story and Vision of Christian faith. We have no greater gift to share! ■

Thomas Groome is a longserving professor of theology and religious education at Boston College’s School of Theology and Ministry, and director of BC’s Ph.D. in Theology and Education. He is a former director of the Church in the 21st Century Center.

This revised edition of “Share Your Faith Stories” was originally published in C21 Resources—Our Faith Our Stories (Fall 2015). Guest Editor: Brian Braman.

Learn more about the C21 Center's popular Agape Latte program, a monthly faith storytelling series for teens and young adults. It was founded at Boston College in 2006 and has spread to over a hundred high schools, colleges, and parishes nationwide.

Interested in bringing Agape Latte to your school or parish?

Contact the C21 Center at church21@bc.edu

Celebrating 20 Years | ANNIVERSARY ISSUE 9

A Catalyst and Resource for the Renewal of the Catholic Church Our Faith Our Stories

“There is probably no more effective way for us to share “the greatest Story ever told”—Christian faith— than through the filter of our personal stories.”

Young People: Temples of the Holy Spirit

Casey Beaumier, S.J.

Casey Beaumier, S.J.

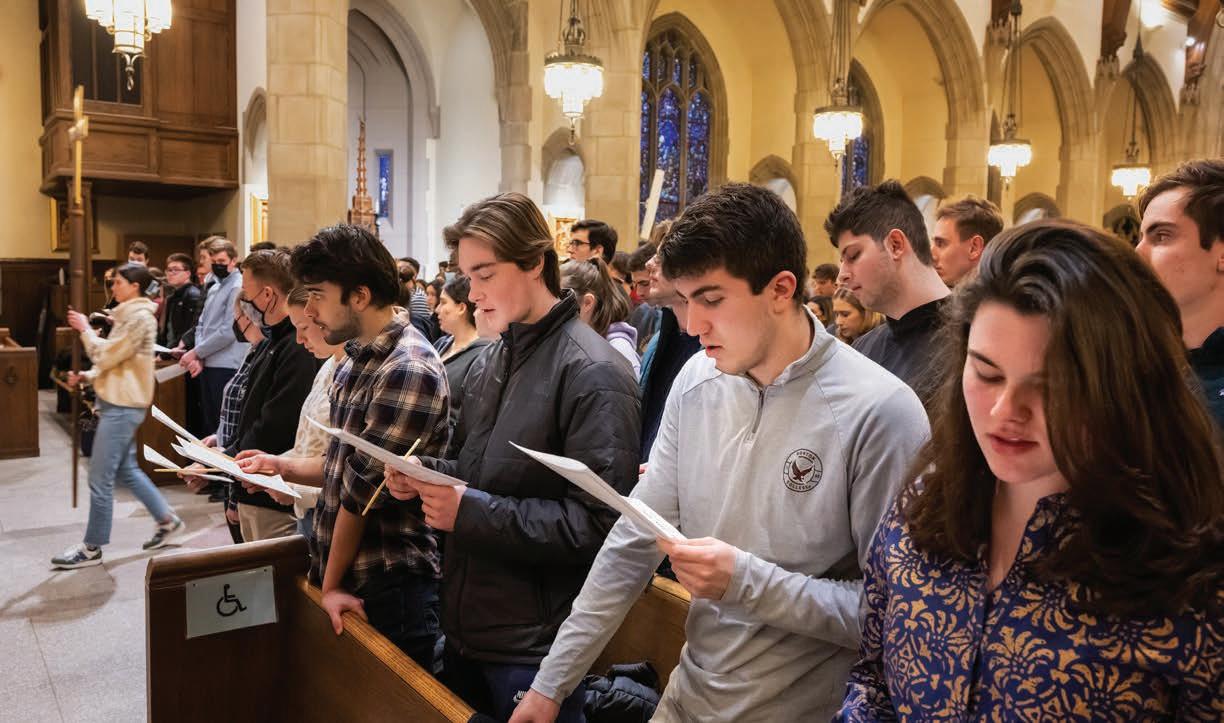

Yyoung people crave spiritual conversation and, if given the opportunity, experiences to explore and to express the inner movements of their hearts within the community of their peers. Beginning in 2016, Boston College has been home to a program that introduces high school students to such an opportunity. These students are engaging the Spiritual Exercises of Saint Ignatius of Loyola through Ever to Excel, a program that has now hosted nearly 800 students from all over the world. These students arrive on Sunday in time for an opening dinner and remain on campus until Friday after lunch. During the course of the week and under the guidance of Boston College undergraduates who serve as mentors, the students experience important movements of the Exercises through video presentations, k eynote speakers, faith-sharing groups, and nightly candlelight Masses. The goal is to make accessible those stirrings of the interior life that are worthy of attention and strengthening. Young people understand the value of physical exercise and the role it plays in contributing to living a good and balanced life. It is through this association that Ever to Excel presents spiritual exercise as a means for living out a faith life, which like physical exercise, contributes to living a good life.

Each day brings to the participants different exercises that afford them with opportunities to stretch t hemselves interiorly with the hopeful outcome of stronger character and faith. While not all of the students are Catholic or even Christian, the program is explicit in its Catholic spirituality in a way that makes the content appealing and engaging for everyone. For example, on the first day of the program,

students explore the First Principle and Foundation of the Exercises, and they spend time pondering and discussing their identity before God as beloved sons and daughters, companions of Christ, and temples of the Holy Spirit. In other words, each person’s identity before God reveals worthiness of unconditional love, friendship, and respect. This identity is the great equalizer within the human family and this starting point e nables participants to begin to engage one another with eagerness and anticipation. The remaining days build upon this foundational beginning and include themes such as formation, discernment, pilgrimage, mission, and magis.

The undergraduate mentors are prepared with faith-sharing questions for each day. These key questions become the focus of the small-group activities that t he mentors facilitate. The outcome of these exchanges is increased capacity to listen with interior ears and to speak with greater vulnerability and sincerity. This style of spiritual conversation is foreign to most young people today and can even seem to be off-putting at the beginning. By Friday, however, it has not been unusual for students to say that Ever to Excel was the most important week of their lives. They have experienced a level of engagement that they have been craving and that the Lord has wanted them to experience in order to grow closer to Him. ■

10 c21 resources | winter 2022/2023

HANDING ON THE FAITH

Casey Beaumier, S.J., is the University Secretary at Boston College and the director of the Institute for Advanced Jesuit Studies.

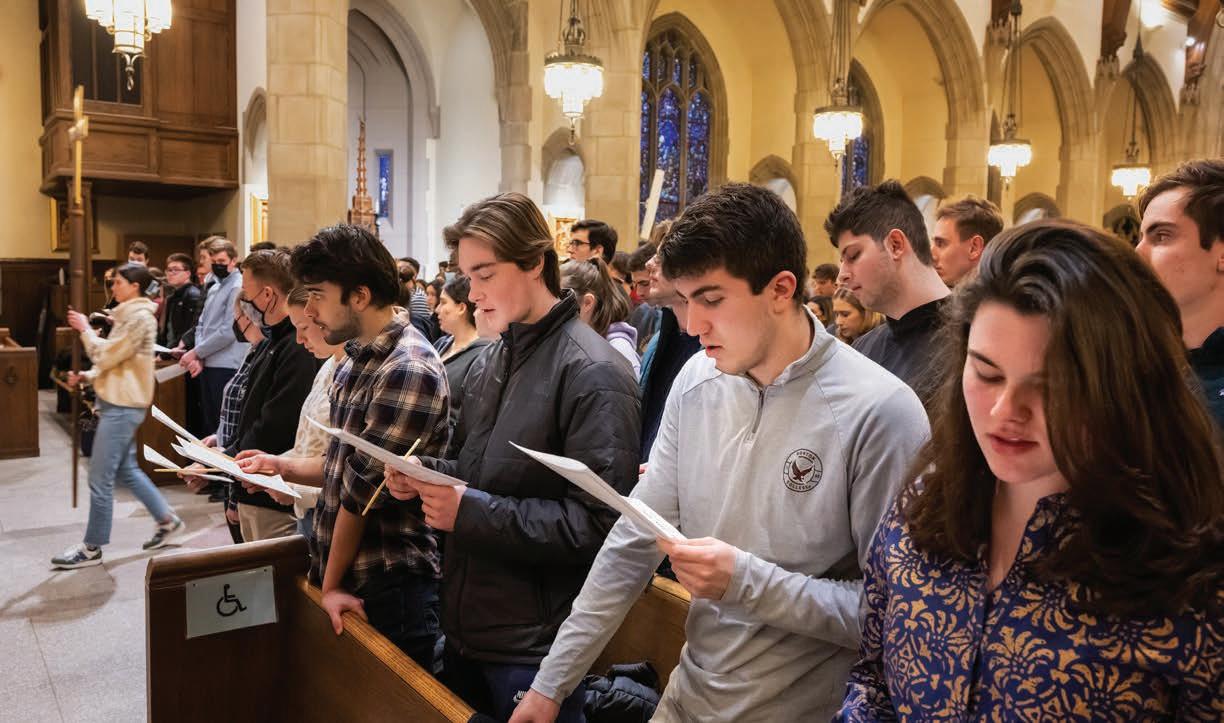

photo credits: Institute for Advanced Jesuit Studies—A. Taiga Guterres

Each summer, Boston College students serve as mentors to the high school participants in the Ever to Excel program.

High school students from around the world are invited to Boston College this summer for the Ever to Excel program. Drawing from the wisdom of the Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius of Loyola, the program provides rising sophomores, juniors, and seniors the resources and supportive community environment to contemplate how to create a more meaningful life through the lens of Jesuit spirituality.

Session I:

Sunday, July 23, to Friday, July 28, 2023

Session II:

Sunday, July 30, to Friday, August 4, 2023

For more information about Ever to Excel and the application process, please visit bc.edu/ evertoexcel or email evertoexcel@bc.edu

Learn more:

Celebrating 20 Years | ANNIVERSARY ISSUE 11

“Each person’s identity before God reveals worthiness of unconditional love, friendship, and respect.”

Melodie Wyttenbach

C Catholic Schools A Way FORWARD

catholic schools are true treasures in the life of the Church. Across the globe, nearly 35 million children attend Catholic primary schools, 20 million attend Catholic secondary schools, and more than 7 million attend Catholic preschools and nurseries. Serving 1.6 million students in the United States alone, Catholic schools have a history of being centers of evangelization, and of social and intellectual empowerment, for millions of Catholics and others.

With the conviction that human beings have a transcendent destiny, U.S. Catholic schools have been a beacon of light in times of uncertainty. In the late 1800s, with faith as an anchor, thousands of European immigrants turned to Catholic schools to educate their children as they transitioned their families to a new country. Immigrant families found comfort in community, and a space where their language, culture, and traditions would be honored. More recently, between 2020 and 2022, a time marred by an uncertain COVID19 pandemic, Catholic schools with a resilient spirit and agile leaders found a way to re-open safely despite the unknowns of a microscopic virus. “In fall 2020, while just 43% of public schools and 34% of charter schools offered in-person learning in September, 92% of Catholic schools offered in-person learning.” As the doors opened, and Catholic schools prioritized in-person learning, a boost in enrollment resulted, the first in decades.

“The light shines in the darkness and the darkness has not overcome it.” (John 1:5)

In both situations, the light of Catholic schools became evident as Catholic education “involves not just the head but the heart, not just the soul but the body. Physical exercises are as important as spiritual exercises. Learning is as important as a good diet. Students pray,

learn, and eat healthily as ways to glorify God and care for their entire selves. All are gifts from God.” This holistic approach to education is what sets Catholic education apart and it occurs because Catholic educators center cura personalis and accompaniment.

Cura personalis is Latin for “care of the whole person” or “care for the individual person.” Cura personalis envisions and cares for the person as God envisions and cares for her or him. Cura personalis reminds all educators that education does not end with academic excellence, but helps the person grow in his or her relationship with God.

Pope Francis sees accompaniment from numerous practical and theological angles, where essentially we a re not alone, and we experience the divine through community. Catholic schools embrace accompaniment as a central tenet as to how we educate: “… we need a Church capable of walking at people’s side, of doing more than simply listening to them; a Church which accompanies them on their journey; a Church able to make sense of the ‘night.’”

We live in a rapidly changing and increasingly global society. At times it feels as if the “night” is all around us—in the darkness of living in the midst of a pandemic, during an age of polarized politics, climate change, mass shootings, and escalating mental health issues. Now more so than ever do we need schools that

12 c21 resources | winter 2022/2023

HANDING ON THE FAITH

Catholic schools will continue to inspire children to change society and the world for the better.

embrace cura personalis and are willing to accompany their students and families in a holistic manner. It is because of this need that Catholic schools meet that they will continue to inspire children to change society and the world for the better.

Catholic schools are and will continue to be a central mission of the Church in this century and the next. As readers of this 20th anniversary issue look to breathe new life into the Church, we must begin with our youth, as they hold the greatest hope for our future. As people of faith, we must continue to support our Catholic schools—giving one’s time, treasure, and talents—in ways that let the light of these schools shine even brighter. This may mean when there is a need for substitute teachers, consider the time you may be able to give. When there is a capital campaign for facility upgrades, consider the resources you may be able to give. When you see students preparing for their First Communion, consider the prayers you may be able to offer. We all can play a part in amplifying the light of Catholic schools. And the future of our Church starts with our youth. Now is the time to let their light shine. ■

Melodie Wyttenbach is executive director of the Roche Center for Catholic Education and a faculty member for the Lynch School of Education and Human Development at Boston College.

BREAKFAST WITH GOD

Breakfast with God is a flexible children's faith formation program that creatively wraps prayer, song, a children's story, and a craft in a Gospel message.

T he Breakfast with God guides offer easy, step-by-step instructions for planning a Breakfast with God lesson in your home, classroom, parish, or virtually on Zoom. Each downloadable guide focuses on a specific Gospel and theme.

For more information, please visit bc.edu/breakfastwithGod or scan this code.

FAITH FEEDS FOR CATHOLIC EDUCATORS

In partnership with the Roche Center for Catholic Education, the C21 Center developed FAITH FEEDS guides around gifts or virtues that challenge Catholic educators to reflect on how they are living out their vocation by being adaptable, joyful, attentive, visionary, and humble in their everyday lives.

Perfect for professional development!

For more information, please visit bc.edu/faithfeedscatholiceducators or scan this code.

Celebrating 20 Years | ANNIVERSARY ISSUE 13

Sources for this article can be found at: bc.edu/c21anniversary20 BREAKFAST WITH GOD GUIDE THEME: SHARING

photo credit : Jesus Ramirez

The Treasure of Hispanic Catholicism

Hosffman Ospino

Hosffman Ospino

Aa breath of fresh air and renewed energy are profoundly transforming the entire U.S. Catholic experience from the ground up in many ways, thanks to the fast-growing Hispanic presence. Hispanics account for 71 percent of the growth of the Catholic population in the country since 1960. In large parts of the South and the West, as well as in a growing number of major urban centers throughout our geography, to speak of U.S. Catholicism is to speak largely of the Hispanic Catholic experience—and vice versa.

At the heart of the freshness and new energy that Hispanics add to the life of the Church in the United States are the people. Young people! The median age of U.S. Hispanics is 30. About 35 percent of all Hispanics in the country are under the age of 21. Ninety-four percent of Hispanics younger than 18 are U.S.-born. These are numbers that inspire hope. The potential of any society, or an institution like the Catholic Church, is intimately linked to its human capital, particularly the young. How U.S. Catholics respond to and engage Hispanic youth will likely be the most telling indicator to determine vitality and growth—or decline—of the American Catholic experience in the upcoming decades.

A GIFT FOR ALL

Much of the good news for the Church in the United States is that most Hispanics remain Catholic despite the increasing influence of secularism and pluralistic trends in our society. At a time when about a quarter of the U.S. population self-identifies as nonreligiously affiliated (or “nones”), Hispanic Catholics offer a rather countercultural alternative to such a dynamic by witnessing a faith that is rich in traditions, stories, rituals, expressions, and symbolism. Contemporary secularism, as philosopher Charles Taylor suggests, seems to be the consequence of a process of “disenchantment” of reality, a condition that prevents many people in our Western world to perceive and even encounter the sacred in the everyday. For millions of Hispanics, the worldview is much different, actually one that is more akin to the sacramental imagination that has given life to the Church for two millennia.

In many corners of our geography, it is not unusual to encounter Hispanic Catholicism displayed at its best through street processions during major holy days. The beauty of the murals and other artistic expressions that creatively

14 c21 resources | winter 2022/2023 HANDING ON THE FAITH

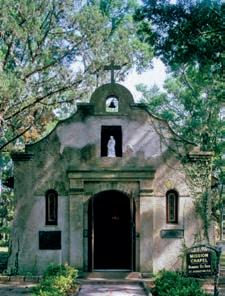

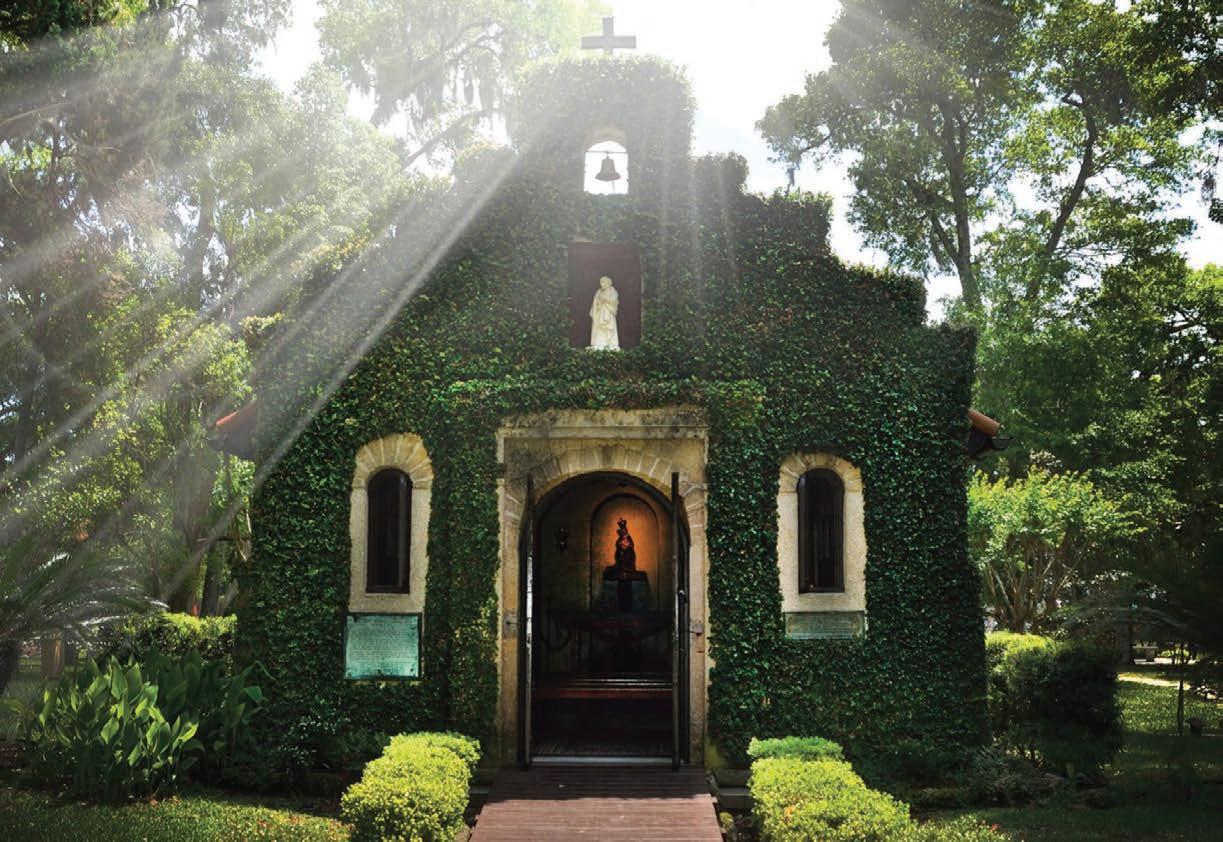

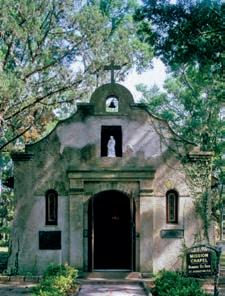

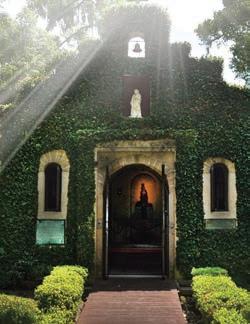

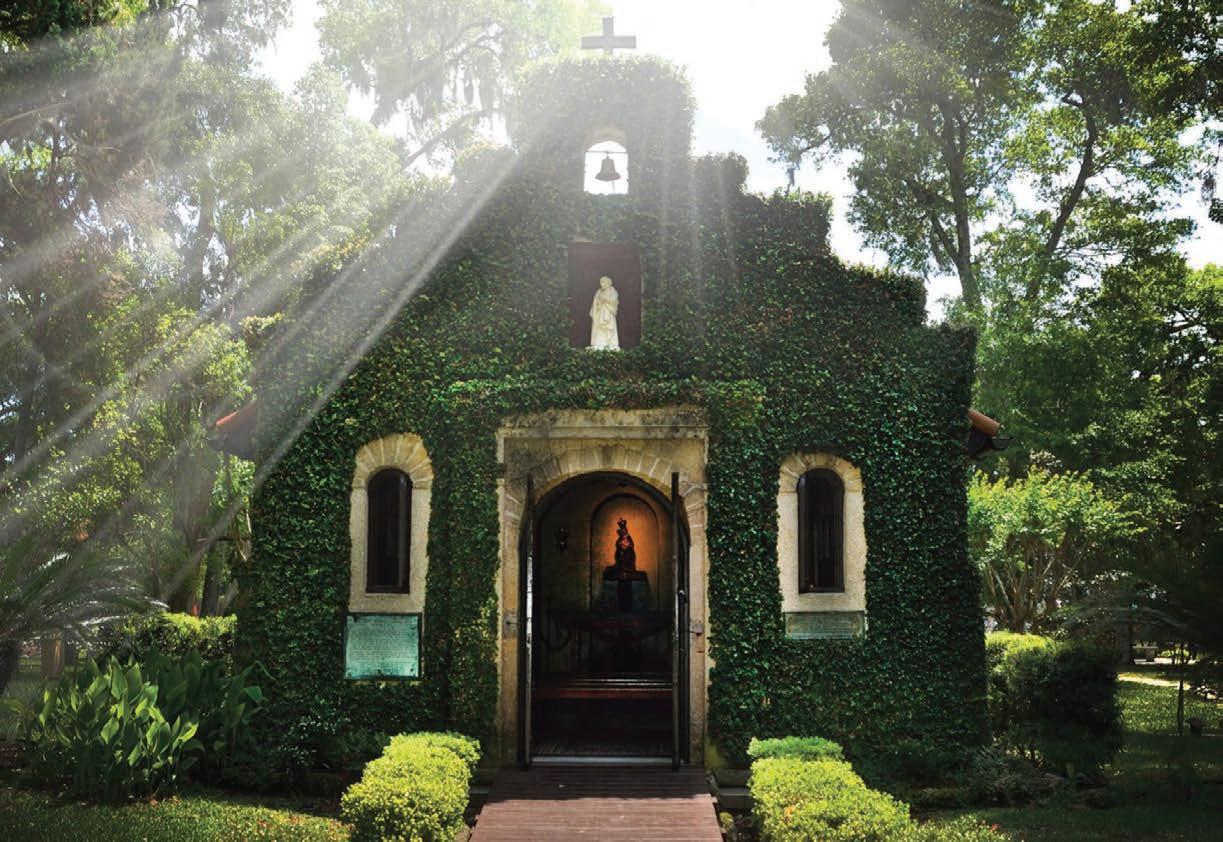

photo credit : National Shrine of Our Lady of La Leche —July 2020. Google.com

encapsulate the dialogue between Catholicism and Hispanic cultures is mesmerizing. Public displays of faith in neighborhoods and churches where Hispanics are present announce out loud that there is something novel in U.S. Catholicism: a unique opportunity to experience the richness of our faith tradition in new ways.

QUESTIONS AND TRANSITIONS

Mindful of the transformation that our faith communities are experiencing everywhere thanks to this Hispanic presence, Catholics of all racial and cultural backgrounds, including the millions of Hispanic Catholics who have been part of the United States of America for several generations, must contemplate two important questions. First, how do we allow ourselves and our communities to be sincerely transformed by the richness of the Hispanic religious and cultural traditions? Second, how do we best share with the present generation of U.S. Catholics, largely Hispanic, the many resources that helped the previous generations thrive? There is no doubt that we as a Church—and as a society—are becoming something new. And this is good news because renewal is always a sign of God’s Holy Spirit working in our midst.

Both questions point to the fact that this is a time of transitions that require a great deal of conversion: personal, communal, and pastoral. Transition for some Catholic communities and institutions means embracing Christian practices of hospitality and solidarity. For others it is about being creative to serve the pastoral and spiritual needs of Hispanics in ways beyond the usual. And still for others, transition requires a good measure of letting go, so the new voices can take as much initiative as necessary in the forging of the new American Catholic experience in the 21st century, fostering collaborative partnerships while drawing from the best of their own wells.

A GREAT OPPORTUNITY

It is often asked why there aren’t more Hispanic Catholics in positions of leadership in the Church and in the larger society, or why there aren’t more Hispanic Catholic families supporting our parishes and programs. Both are fair questions since Hispanic Catholics have lived in the U.S. longer than any other Catholic group. But the questions also demand that all Catholics in the United States look back at our history to examine attitudes toward Hispanics in our own communities and institutions. We also need carefully to assess how much we understand the complex realities that shape the lives of most Hispanics in the United States. This is the crux of the reflection that will likely define major choices and commitments within U.S. Catholicism during the first half of the 21st century.

It is interesting to observe, for instance, that more than two-thirds of Hispanics are U.S.-born, yet most outreach efforts on the part of the institutional Church focus on the immigrant portion. This is most evident in the context of parish life. Though a full quarter of Catholic parishes in the country have explicitly developed some form of Hispanic ministry, almost all define such ministry as pastoral outreach in Spanish and most

serve primarily Hispanic immigrants. One might read this as a major discrepancy that reveals the fast-evolving Hispanic Catholic experience and how slow we as a Church—including Hispanics of all generations—have adjusted to respond adequately to the reality of being American and Catholic in an increasingly Hispanic Church. There is an element of truth to this. But I prefer to read this reality more as an opportunity.

Since the middle of the 20th century, we have been writing a major chapter of the “Immigrant Church” experience, one that has been gradually reshaping U.S. Catholicism. Many Catholics have paid attention to this experience and done their best to engage it. Some have resisted the changes that come with this new chapter. Many others, too many I would say, have ignored it. Yet, numerous signs point to concerted efforts at this historical juncture to finally face the changing demographic and cultural trends directly impacting our faith communities and institutional structures. Paradoxically, we may be one generation, perhaps two, behind in our response. Yet, this is undoubtedly a great opportunity.

Catholics of all backgrounds are increasingly discerning how to seize the day engaging Hispanics who are U.S.-born. They are not immigrants nor fully assimilated into any of the most dominant embodiments of the larger U.S. Catholic experience. We seem to be at the dawn of something new, definitely a unique opportunity much anticipated by visionaries and thinkers who wrote about these matters half a century ago. Yes, it is an opportunity to imagine fresher approaches to youth ministry and catechesis in our faith communities, integrating the many rich expressions of Hispanic faith and cultures and responding to the questions of Hispanic youth in their own context. This is an opportunity to revisit how our Catholic educational institutions at all levels are living out their mission in service to the Church today, a largely Hispanic Church. This is the opportunity to actualize the Church’s prophetic commitments to life, justice, and truth, addressing the many challenges that prevent millions of young Hispanics—our Catholic children—from living fuller lives and from seeing the Church as a home on their spiritual journey.

What a great moment to be Catholic in the United States! ■

Hosffman Ospino is an associate professor of Hispanic ministry and religious education and chair of the Department of Religious Education and Pastoral Ministry at the Boston College School of Theology and Ministry.

An expanded version of this article was originally published in C21 Resources— The Treasure of Hispanic Catholicism (Spring 2016).

Guest Editor: Hosffman Ospino

Celebrating 20 Years | ANNIVERSARY ISSUE 15

Catalyst and Resource for the Renewal the Catholic Church SPRING 2016

The National Shrine of Our Lady of La Leche is located at the Nombre de Dios Mission in St. Augustine, Florida. Originally built in 1609, it is the oldest shrine in the United States.

The Treasure of Hispanic Catholicism

The Church and contemporary Challenges

Richard Lennan the church in the 21st Century Center at Boston College had its birth in the throes of the clerical sexual abuse scandal. The reverberations of that scandal continue even twenty years later, but today’s Church also confronts a raft of new challenges. This article surveys some of these and identifies possibilities for the Christian community to address them. The possibilities all have roots in the tradition of faith and provide ways for members of the Church to witness to the life-giving presence of the trinitarian God.

As the Church, our responsibility includes being alert and open to the movement of the Spirit. Doing so requires us to recognize and utilize the single largest resource we have to address issues in our world: our shared faith. It requires too that we never cease to ask whether all we do as Church reflects the Gospel.

1. Global anxiety resulting from COVID-19 and its attendant social and economic impact

Faith in Christ offers hope for the present, not simply for “the next world.” For the Church to embody this hope, all disciples of Christ must expand their vision beyond self-interest to an everdeepening openness to “the common good.” Membership of the Church, then, does not legitimate isolation from the needs of the world but summons us to compassion and generosity.

2. Burgeoning technology and the world of social media

Members of the Church can turn to Christ as “the way, the truth, and the life” (John 14:6). This anchoring offers a foundation that empowers resistance to “disinformation” and “misinformation.” Similarly, our grounding in the presence of God in humanity reminds us that “virtual” relationships cannot substitute for sharing each other's joys and sufferings.

3. A culture that combines— uneasily—a hunger for authenticity, suspicion of institutions, and escape into “celebrity”

Faith in the God who meets us in the humanity of Jesus affirms human life as the site of grace. Members of the Church can recognize unambiguously the limits of all human projects, but affirm—also unambiguously—that darkness cannot overcome grace. Nurtured through word and sacrament, members of the Church can live as people of hope, even in this complex moment.

4. A nti-racism, religious pluralism, and “decolonialization” Witness to the unconditional love of God for all people is an irreducible consequence of seeing human history as the venue for encountering the grace of God’s Holy Spirit. Members of the Church are called to resist anything that obscures the dignity of any person or group in society. The Church itself must remain open to conversion to God’s limitless vision for human thriving.

creation is also the God who creates and treasures all people. The Church’s care for the earth and option for the poor are never less than imperatives of Christian faith.

7. P revalence of “nones,” “disaffiliation” from the Church, decline in the social influence of the Churches, and the association between the Church and multiple forms of scandal

Today, “the Church,” especially our structures and ways of proceeding, is often an obstacle to the good news that the Church exists to proclaim. Rather than rail against “the times,” we, as Church, must be self-critical, while also discerning together possibilities for creatively faithful changes in our structures and forms of decision-making. Synodality, at the heart of which is truly listening to each other and to the Spirit, enhances these possibilities. ■

5. T he pluralism

of human experience in matters of gender and sexuality

In listening to, learning from, caring for, being in dialogue with, supporting, serving, and nurturing hope in all people, individual members of the Church, and the ecclesial communities to which they belong, can make Christ present. The Gospel summons us to presume goodwill in all people and to be attentive to the movement of the Spirit in every setting.

6. A nxiety for the future in light of “the cry of the earth and the cry of the poor”

Faith in Christ is inseparable from reverence for the physical world as not simply God’s creation but the venue for God’s incarnation in Jesus Christ. The God who gives life abundantly in

Richard Lennan is a priest of the diocese of Maitland-Newcastle, Australia, and is professor of systematic theology and chair of the ecclesiastical faculty at the School of Theology and Ministry at Boston College.

Read C21 Resources— The Vocations of Religious and the Ordained (Spring 2011).

G uest Editor: Richard Lennan

16 c21 resources | winter 2022/2023 HANDING ON THE FAITH

T

the vocations of religious and the ordained church in the 21 cent ury cen er

RESOURCES FOR HANDING ON THE FAITH

C21 Resources Magazine

Launched in the spring of 2003, C21 Resources magazine serves as the hallmark publication of the C21 Center. Each themed issue is a compilation of the best analyses and articles on key challenges facing the Church today. As with all C21 Center initiatives, it aims to serve as a catalyst and a resource for renewal, sparking conversation and reflection. Subscriptions and additional copies are complimentary to individuals, schools, and parishes.

Discover and download all 35 issues— or subscribe at: bc.edu/c21resources

The FAITH FEEDS program is designed for parishioners, teachers, and individuals who are hungry to share faith conversations over coffee or a potluck lunch/dinner with old and new friends. Pick a theme, download the guide, and gather in person or online.

Visit bc.edu/faithfeeds for more information on hosting your own FAITH FEEDS session or register to join the C21 Center’s weekly session Fridays at 1 p.m. (EST) by Zoom.

The C21 Center hosts Pray It Forward, a virtual, weekly prayer program on Wednesdays from 4:004:15 p.m. EST. Participants join by Zoom for a brief time-out to pray as a community. All are welcome!

(In partnership with the Boston College Alumni Association)

For more information and registration: bc.edu/prayitforward

Celebrating 20 Years | ANNIVERSARY ISSUE 17

Having a faith conversation with old and new friends is as easy as setting the table. FAITH FEEDS GUIDE OUR FAITH, OUR STORIES

THE CHURCH IN THE 21ST CENTURY CENTER SPRING/SUMMER 2022 FAITH IN ACTION Around the World C21 Resources Spring 22 FINAL_PRESS FINAL June8.indd 1

A Church in Need of Its People

Fr. Michael J. Himes

Ccatholicism is alive . Understanding this simple statement is crucial to understanding the nature of the Catholic Church. It is often easy to reduce Catholicism to a philosophy we subscribe to, or a list of truths we believe in. While philosophies and statements of truth are an integral part of being human, Catholicism is so much more. Catholicism is the ongoing history of the People of God. In other words, Catholicism is the life of what we have come to call “the Church.”

Catholicism is alive because we are alive as a community of believers. The way we live our lives is the life of Catholicism. St. Teresa of Avila put this sentiment into provocative and poetic words when she wrote:

“Christ has no body but yours. No hands, no feet on earth but yours. Yours are the eyes with which he looks. Compassion to the world.

Yours are the feet with which he walks to do good. Yours are the hands with which he blesses all the world.”

Take a moment to reflect on that fact. If we are honest with ourselves, this is a daunting realization. The relationships we have with others and the roles we fulfill in our communities are the life of Catholicism.

Articles like this are meant to be prompts for further reflection on the life of Catholicism as it is being lived out by the Catholic Church today. However, before discussing the different roles and relationships in the Catholic Church, such as the role of authority, or the relationship between our diocesan priests and their bishop, or how parishes might function, or any of the countless other issues that deserve discussion among Catholics today, the first question that we must answer is why we care about being a Church at all. Why do we need a Church with all its attendant problems and questions? Two reasons: because the Word has become flesh, and because God is love.

The too often unasked—and so, not surprisingly, unanswered—question about the Church is “Why have one?” This is not a question about the Church’s mission, important as such a question is. Rather, it is a much more personally pressing question: “Why do I need a church?”

In order to answer this seldom asked question, we may profitably recall two points. I say “recall” because both are so deeply embedded with the Catholic understanding of Christianity that neither can come to us as a new discovery. More often than not, good theology,

like good pastoral practice, is a matter not of saying something never heard before but of remembering something forgotten. The first point is that the Word became f lesh. Christianity is not about timeless truths. First and foremost, it is news—Good News, in fact—about particular events in the lives of particular people living at a particular time and in a particular place.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, the term often used to describe this aspect of Christianity was “the scandal of particularity.” Certainly there is something shocking, something scandalous, about the claim that the whole of human history, the whole history of the cosmos, reaches its climax, its fulfillment, in the life, death, and destiny of one Jewish man in Palestine in the latter years of Augustus’s reign and the first years of Tiberius’s. How that one person and his story are of ultimate significance for every human being before him and every human being after him is a very big question, indeed. But it may be important to reconfront that “scandalous” claim today from a slightly different angle.

If Christianity is not about eternal verities that could, at least in principle, be discovered anytime anywhere, if it is, in fact, the proclamation of news about u nique events at one point in time and space, then there is only one way in which you and I can learn that news: someone has to tell us. News requires a reporter. We have, of course, heard the Good News from reporters; in my case, I first learned the Gospel from my parents, my family, my teachers, and my pastors. And they learned it from their parents, families, teachers, and pastors. And so on and on, back to the first reporters who proclaimed the great Good News. That is why my relationship to God in Christ necessarily requires my relationship to others: I would have no awareness of God in Christ apart from that relationship. One reason why I need the Church is that, apart from the Church, I would have no knowledge of God in Christ.

The second point that highlights our need for the Church is that God is love. Faith in the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ is impossible without love for one another. There is certainly nothing new in that statement; the Gospel and Epistles of John certainly said it insistently and powerfully 19 centuries ago, and it has been repeated again and again through the intervening years by women and men who have lived Christianity wisely and well. One cannot understand what it means to say that “God is love” (1 Jn. 4:8 and 16) if one has

18 c21 resources | winter 2022/2023

ROLES & RELATIONSHIPS living catholicism

no concrete experience of love. An agapic community is the precondition for true belief in God. All talk about God runs the risk of blasphemy, and all talking to God in prayer the risk of idolatry. For it is perilously easy to chatter about or to our own best image of God rather than God. What guards against that danger is the “controlling metaphor” for God in the Christian tradition: agapic love. If you have no experience of agapic love, then quite literally you will not know what you are talking about if you say “I believe in God.” The Church, on all its many levels from the domestic church of the family to the Church universal, is to be an agapic community. Needless to say, on all its many levels it fails again and again. But it confesses its failure and lovingly struggles to love.

Ultimately, the reason we need the Church is because we cannot believe apart from community. To speak of spirituality without roots in a community is to flirt with idolatry. Trying to enter into relationship with God in some private, individualistic fashion is a guarantee that one will be talking to oneself. Apart from the day-today, sometimes achingly hard, occasionally grindingly dull, always deeply humbling attempt to love those around us in practical ways, one simply cannot claim that one is in relationship with God. Never was this said more clearly or decisively than by the author of the First Epistle of John: Anyone who claims that he loves God but does not love his brothers and sisters is lying (4:20).

In closing, I encourage you to reflect on what it means to successfully live out the achingly hard, occasionally grindingly dull, always deeply humbling attempts to love those around us in practical ways. I say “practical ways”

because love is an action before it is a feeling. Roles and relationships must be actively lived and formed by the agapic love that allows us to experience God, and it is my hope that these words will instill within you a conviction that Catholicism is alive through your life. You are charged with bearing the Good News in your life, and you are charged with loving others so that they might know God as love. The Church needs each of us to participate in its life or it has no life. Living our Catholicism is the assurance that there is and will be a living Catholicism. ■

Fr. Michael J. Himes (1947–2022) was a diocesan priest from Brooklyn, New York, a distinguished theologian, and a faculty member at Boston College for almost three decades.

This article was originally published in C21 Resources— Living Catholicism: Roles and Relationships for a Contemporary World (Fall 2013). Guest Editor: Fr. Michael J. Himes

Explore several C21 videos featuring Fr. Michael Himes: bc.edu/c21anniversary20

Celebrating 20 Years | ANNIVERSARY ISSUE 19

living catholicism Roles and Relationships for a Contemporary World edited by michael himes SESQUICENTENNIAL ISSUE

“You are charged with bearing the Good News in your life, and you are charged with loving others so that they might know God as love.”

photo credit : Courtesy of Justin Knight, Boston College

Lighting the Way

Joan D. Chittister, OSB

In a March 2022 NCR article, Joan Chittister spotlighted the current state of and concern for the religious sister community in the United States. According to the Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate (CARA), this community of nearly 180,000 sisters in 1965 is now approximately 40,000 (2021). Chittister credits the tremendous and often unheralded work of these women who give "their hearts and minds and lifetimes to the world," describing her fellow sisters as "the living memory of Jesus who walked the dusty roads of Israel among us simply 'doing good.'" In this follow-up article, she ponders and asks us all to reflect on the reasons for the decline, God's work in this shift, and the road ahead for religious life.

Tthe question this article purports to answer is a clear one: Will religious life rise again? Yes? But is it sensible in this day and age to even think of such a thing? The answer is actually a simple one, but a potentially life-changing one at the same time. Several ancient stories long ago illuminated both the purpose and the spirituality of what it means to be a religious. Even now, even here.

The first of those stories is from the tales of the desert monastics. One day, Abbot Arsenius was asking an old Egyptian man for advice on something. Someone who saw this said to him: “Abba Arsenius, why is a person like you, who has such great knowledge of Greek and Latin, asking a peasant like this for advice?” And Arsenius replied, “Indeed, I have learned the knowledge of Latin and Greek, yet I have not learned even the alphabet of this peasant.”

The Zen masters, too, tell a story about the nature of real religious commitment. The monk Tetsugen made the goal of his life the printing of the Buddha’s sutras onto Japanese woodblocks. It was an enormous and expensive undertaking, and just as he collected the last of the funds he needed, the Uji River overflowed

and left thousands homeless. So Tetsugen spent all the money he’d collected on the homeless and began his fundraising again. But the very year he managed to raise the money for a second time, an epidemic spread over the country. This time, Tetsugen gave the money away to care for the suffering. It took 20 more years to raise enough money to print the scriptures in Japanese. Those printing blocks are still on display in Kyoto. But to this day, we’re told, the Japanese tell their children that Tetsugen actually produced three editions of the sutras and that the first two editions—the care of the homeless and the comfort of the suffering—are invisible but far superior to the third.

Clearly, the Zen masters know what we know: witness, not theory, is the measure of the spirituality we profess. What we do because of what we say we believe is the real mark of genuine spirituality.

Finally, St. Paul is very clear about our common obligation to be part of the Christian enterprise. “To each one,” he teaches in 1 Corinthians, “the manifestation of the Spirit is given for the common good.” It is, in other words, given to each of us for the sake of the Christian community. These personal gifts of ours are not for our

20 c21 resources | winter 2022/2023

ROLES & RELATIONSHIPS