INCITE 2025

An anthology of student writing and visual art

An anthology of student writing and visual art

INCITE is an annual anthology showcasing student writing and visual art from CIS Ontario member schools.

The CIS Ontario Conference of Independent Teachers of English (CITE) network supports the teaching and learning of English, EAL, media studies, and drama at CIS Ontario member schools.

In addition, the network hosts an annual professional event—the CITE Conference—which also celebrates the publication of INCITE, an anthology of student writing and visual art.

This is the sixteenth iteration of the INCITE anthology, and we are extremely proud of the work students produced.

Mike Lesiuk, The Country Day School

Sarah Williams, The Country Day School CITE Co-Chairs

Photographer: Eden Boudreau

Andrew F. Sullivan is the author of The Marigold, a novel about a city eating itself, which was a finalist for the Aurora Awards, the Locus Awards, and the Hamilton Literary Awards, and named a “Best Book of the Year” by Esquire, The Verge, Book Riot and the Winnipeg Free Press. He co-wrote The Handyman Method with Nick Cutter, a novel about home improvement gone wrong. Sullivan is also the author of the novel WASTE, called a “brutal, mesmeric debut” and one of the Best Books of the Year by the Globe & Mail, and the short story collection All We Want is Everything, a Globe & Mail Best Book of the Year and finalist for the ReLit Award. He lives in Hamilton, Ontario.

When I work with younger writers, I often encounter a lot of fear. Fear about making the wrong choice or making art the wrong way. In fact, there is often a great fear of failure and judgment thrumming through us all, inhibiting our creativity and implicitly denying our own inspiration. With the diverse and original work collected here, I’m delighted to find young writers willing to experiment, to play, and to make bold creative choices.

Whether it’s prose or poetry, these pieces illuminate the complex relationships we have with the established boundaries in our lives. They deftly explore the possibilities and ramifications of moving beyond what we think we know into the unfenced unknown. These stories and poems acknowledge our debilitating fears and uncertainties but then push through them to express a greater truth, detail a new personal discovery, or offer a freshly tilted view of our unstable world.

In 2025, we find ourselves living in more than interesting times. As the world mutates and ruptures around us, our creative work is still where we are most free. Our forms of expression only become more valuable as fresh challenges attempt to smother their impact. Every time we decide to make something new, we embrace that possibility of change. By devising our own realities and telling our stories together, we can peek over the boundaries of the old world to find our new selves waiting on the other side with open arms and open hearts. In opening these pages, you may open your mind.

I hope you will find what you need inside.

Co-Chair: Sarah Williams, The Country Day School

Co-Chair: Mike Lesiuk, The Country Day School

Communications Director: Ashley Domina, Villanova College

CITE Writing Competitions Coordinator: David Finkelstein, Crescent School

Chairpersons Emeriti: Claire Pacaud, St. Clement's School and Ellen Palmer, Appleby College

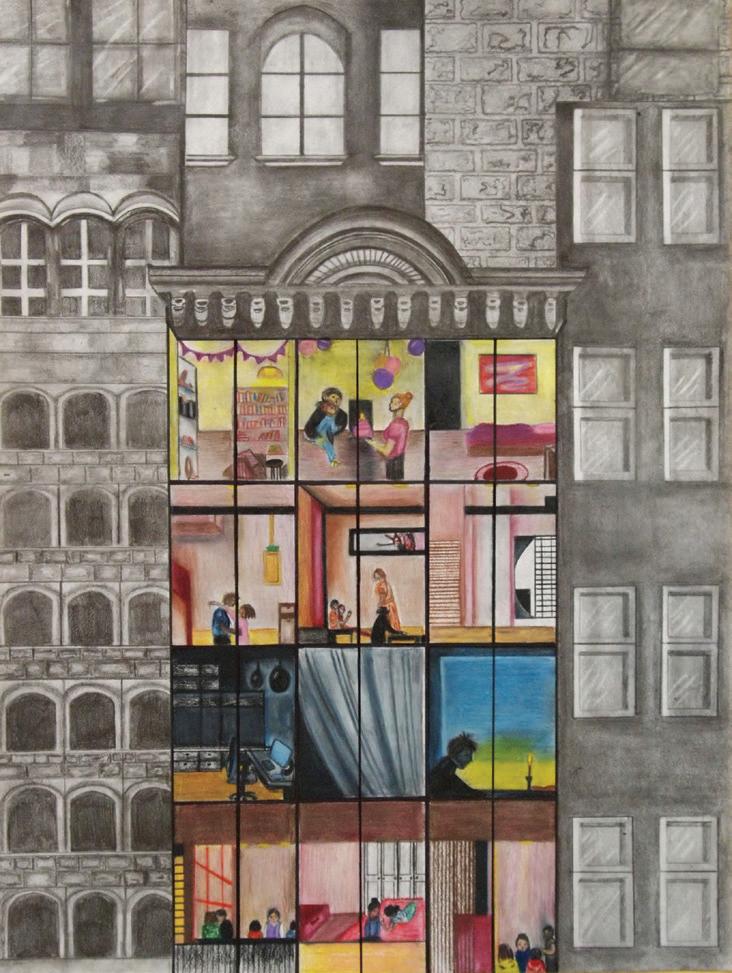

The INCITE 2025 cover features the artwork of Vanessa Bobechko, Grade 11, The Country Day School.

Prompt: Crossing Boundaries

Grades 7 & 8

1. “Red,” Emma Fan, Havergal College

2. “Woman in the Mirror,” Ella Adams, Hillfield Strathallan College

3. “San Francisco, 2098,” Brandon Yin, The Sterling Hall School

Grades 9 & 10

1. “Echoes of Her Song,” Ishaan Grotra, Appleby College

2. “Will You Hear Me,” Eloise Bramer, The York School

3. “Victoria Caldwell: The Truth Behind the Tech,” Adhya Chandradat, The Country Day School

Honourable Mention: “My Honest Poem,” Ashley Smith, St. Mildred’s-Lightbourn School

Grades 11 & 12

1. “White Sheep,” Bryony Chan, The Bishop Strachan School

2. “On the Glass,” Michael Soares, Hillfield Strathallan College

3. “His Name is Sisyphus,” Claire Dai, Appleby College

Honourable Mention: “call it what it is,” Ray Law, St. Clement's School

Prompt: Exploring the Impacts of Taking a Risk.

Grades 7 & 8

1. “The Darkness Within,” Jacqueline Poenaru, Bayview Glen

2. “The Bridge Between Us,” Liliana Au, Bayview Glen

3. “The Door,” Atlis Sandomierski, Montcrest School

Grades 9 & 10

1. “The Crying,” Lara Chamoun, TFS - Canada’s International School

2. “Like an Apple,” Audrey Zhang, St. Mildred’s-Lightbourn School

3. “INCITE Short Story,” Bingyin Geng, St. Mildred’s-Lightbourn School

Grades 11 & 12

1. “The Duet Between The Body & The Mind,” Amanda Zeng, Pickering College

2. “The Hidden Spark Beneath The Adversary: Bajan Bakes,” Joy McConney, St. Mildred’sLightbourn School

3. (Tied) “Full Moon,” Katelyn Wong, St. Clement’s School

3.(Tied) “How to Catch a Snowflake,” Kaitlyn Zhang, The Country Day School

Emma Fan, Havergal College, Grade 8

I haven’t had colour in a long time.

It’s obvious as I wander through an expanse of shelves devoid of vibrancy. The library of my mind resembles a long-abandoned church, once magnificent, now forsaken and crumbling.

One memory stands out against the monotony, drawing me in like water down a drain.

With the sunlight kissing her hair, each strand shimmered with life, catching the light in a mesmerizing dance of crimson and gold. How I loved her hair. Her smile reminded me of strawberries covered in chocolate - sweet and rich, like the way she insisted on dancing in the desert rain, or bought white roses and painted them red after the movie Alice in Wonderland How we laughed and laughed by the fountain in the park as we fed the ducks in the pond. The world was a canvas, and that day my paintbrush created a masterpiece.

I reminisce about that memory often and see a glimpse of my old life. But the past is the past, and my present and future remain as monochrome as ever. She was the colour in my life, and is life really worth living without colour?

Now, I stand in the middle of a crowd. Shades of colour swirl around the people who hurry home to hot meals and shrieks of their children’s laughter. Viridian stalks a woman who orders a flat white every morning; sunshine yellow jumps at the feet of a toddler discovering puddles; amethyst billows behind a fashion designer who sees the world as potential. The colour floats past, buoyed by the happy memories of people I used to be, but recoils from my outstretched hand like oil does water. People avoid my gaze, my fingers leaving grey prints on their joys. I stand alone, isolated by walls that surround me in grey and black, leaving me shivering, my breath distorting the view. I watch as colours collide against my walls, spraying vibrant drops that never quite reach me, unable to join in my solitude.

I sit in my room, darkness one of my only friends left. I press my body against my bed frame until it hurts, splinters pricking at my back, hoping that it would swallow me whole and end all of this. My phone glows, both alluring and devilish beside me. I scroll through the latest news. Another child raped. Scroll. Another town burned to ashes. Scroll. Another war crime gone unpunished. Scroll.

I blink.

Deep down, I feel a muted wisp of obliged sympathy, but no more. Happiness is like a faded memory, barely a feeling of warmth from behind a forbidden curtain. My emptiness scares me, so I paint. Winning Entry

In the bathroom, the cold tiles beneath me remind me I’m an artist. I paint at night when the world has gone to sleep, silently awaiting my next masterpiece. I want to see red. I pull out my brush, poising for my first stroke, feeling it bite into my hand. I can almost feel her again, like if I turn my head, she’ll be sitting there beside me, flashing that innocent grin. As a tribute to her, the only colour I use now is red, crisscrossing my innocent canvas with sharp, crimson lines.

What time is it now? What day? I’m in an office that smells too clean, shifting uncomfortably in front of a bright woman who looks concerned…Hi, I’m Dr. Stone… I fight the urge to leave, pulling at the sleeves of my hoodie…traumatized…need treatment…my walls are closing in on me, I need to go…never too late…her words float past me like garbage in the ocean…prescribe antidepressants… She hands me a small bottle, forces me to take a pill… therapy…family support?...Why am I even here?

I go home and sleep.

During the night, I wake up and walk around the apartment. It’s dark and empty and I truly see for the first time. The unopened boxes, dust gathering in corners and on surfaces. Cards strewn on the table all seem to taunt me: “I'm so sorry for your loss.” All signs of something I didn’t realize until now. I drift out the door, barely touching the ground. I don’t bother closing the door.

I look down on myself from above as if I’m someone else, watching a ghost float through the halls. She ends up in front of the elevator. Did she mean to? The doors slide open and I watch her step into the elevator and turn around, pressing the button for the highest floor. As elevator music plays over a tiny speaker, I try to recognize the person I was seeing. Signs of my suffering have manifested painfully on my body; my clothes hang off my figure, cheeks sunken, skin pale and ghostly. I pray silently, asking for forgiveness for what I’ve inflicted upon this girl.

Stepping out on the roof, the cool night air pulls me back into my body. I feel déjà vù, freedom. My ears stop buzzing, the weight lifts off my chest. Savouring this forgotten feeling, I walk to the edge of the rooftop and glance down. It’s high–so high it should terrify me. But I embrace it, leaning into the welcome relief.

I climb onto the edge - the view is like a revelation.

Colour. It’s come back. No-not a revelation. A revolution. A return to the start of the hopscotch ladder. A full circle complete.

The once impenetrable wall that isolated me melts away, leaving me stunned and blinking in my new world. Without it, I feel empty. Where once it had protected me from the harsh edges of the world, now I was vulnerable. To anyone else, this might seem incomprehensible, but the walls had been my constant companion. But they’re gone now.

Looking out, I admire the spectacle. The city sparkles like a star fallen off from heaven's staircase. The neon signs of downtown blaze defiantly, almost offensive to everything else. The pale moon hangs low in the sky, waiting. The sounds of traffic float up from below, muted by the height, or maybe the wind. A siren wails in the distance - perhaps for someone else standing on their own edge tonight.

A masterpiece. Just missing one final splash of red.

I shift my left foot out over the ledge. I stop. It occurs to me that she would hate seeing me like this. She always said she loved my strength. But this? This is cowardice. Isn’t it? For the first time since that day in the park, I feel omnipotent, euphoric. All else withers in comparison. This last action would create my final painting, the ultimate testimonial to her-but I waver. I close my eyes, and for a moment, I see a flash of red hair and a smile of chocolate strawberries.

It is with a smile I take the step. * * *

But I didn't fall that night. Sometimes angels have wings, but sometimes they have the view of the pavement from thirty stories up. It took a great height at rock bottom to bring me back down to earth. Back into the world. That night the colour returned-not a flood, but in quiet drips. The pale yellow dawn of early mornings, the lush greens and browns of mountain hikes, the harsh blues in my therapist's office softening to amity, and the vibrant red of healing fading to auburn scars all graced my life again with their presence. I was given a choice: step forward, and succumb, or step back, a chance to try again. Some barriers are simply not meant to be broken; instead, taking that first step away and out can make all the difference. My story is not of destroying barriers; it is of decisions, acceptance, and chocolate strawberries.

Ella Adams, Hillfield Strathallan College, Grade 8

Just the mirror, Mirror and me.

While I stare into the figure's eyes, I see the boy I was.

The uncomfortable, awkward boy.

Doomed to an uncomfortable, awkward future.

Never feeling like I belong, always on the outside.

I look at the dress.

I see the woman I want to be.

Stong, beautiful, me.

A glass barrier separates me from the future.

Thin as paper, hard as stone, made of the people who hold me back.

The bullies, the haters, and me.

Reinforced by the fear that no one will understand.

The terror that I will never succeed.

Can I change simply because I want to?

As I stare at the boy in the mirror. I see what might have been.

A horrible future.

Living in that He/Him skin like an itchy sweater.

Too small for me, uncomfortable.

I do not speak out because I am afraid.

Afraid of the haters, the rumours, the comments.

They say that I am wrong, Wrong about how I feel…

While others say, “The skin fits, and there is no reason to shed it.”

As I stare at the boy in the mirror, I am torn, split.

Looking at the glass, I make my decision. It is time to shed the skin and show my true colours.

Staring at the boy I was, I transform into the woman I am and will always be.

I do not change because I want to.

I am not changing. This was me all along.

I am simply removing a costume, a disguise.

No more masks, no more lies.

As I put on the dress, it becomes my armour.

The weight is lifting.

I feel like a bird after the sun has risen, fresh and renewed.

So let them come at me!

Let them yell insults, and bully me.

I will not back down.

I am a woman. Not a man, not a boy.

I am no longer the weak, insecure boy, I am now the woman in the mirror.

Strong, confident and free.

I am the woman in the mirror.

No one can stop me. No one can hurt me.

I am the woman in the mirror.

My dress is my armour and I am invincible.

The woman in the mirror is capable, smart, proud of who she is, and perfect the way she is.

That woman is proud, perfect, and me.

Brandon Yin, The Sterling Hall School, Grade 7

It is a dry and windy day in San Francisco. Despite the wind, smog still lingers in the city. The sky is a bleak pewter color and the sun hides behind the clouds and big puffs of factory emissions, struggling to be seen. The sweltering heat outside makes the weather very adverse today. Not just today, but every day.

I walk along the sidewalk covered with layers of dust and grime. My mouth is parched and sweat dribbles down my face. The densely polluted air is suffocating.

I walk down the path I’d taken every day as a toddler with my grandfather. I’d grown up with my grandfather, mainly, as my parents often made business trips. Grandpa has always been a major part of my life, being the person who comforted me every time my parents were away, the person who had taught me how to draw and paint.

Grandpa often speaks about the ocean, and how he went sailing and kayaking with his friends when he was my age. He even sometimes sketches out the ocean of old San Francisco, tracing its crest and waves. The ocean was my favorite part of his stories and I loved the way he makes it sound so utterly wonderful. It really made me wish that I had lived back then. It made me wish for a brighter future. A more enjoyable future.

I can’t possibly imagine how the once-sparkling ocean full of aquatic life transformed into the murky ocean covered with garbage in front of me. How it all changed in just a few decades. And how that same ocean had also swallowed the lower parts of our coastal city, forcing my family and me to evacuate to the center of San Francisco which is full of high rise buildings. We had to stay in San Francisco due to severely inflated prices in the upper parts of the city, hoping the waves would eventually recede, but they never did. And every day, the water level would only rise higher.

I sit on a dirty bench and stare at the nearly-submerged skyscrapers and trees in the distance, reduced to gaunt skeletons after years of erosion. I sit there for hours, just staring at the waves violently thrashing, sending rotting logs and filthy components of buildings flying. The malice of the waves in the distance is nothing like the waves in Grandpa’s drawings.

The sky darkens as afternoon approaches, and I start walking back. Soon, I see a silhouette running towards me. I see him intently looking at something behind me and quickly run away, so I spin around, just in time to see a massive wave heading towards the city in the distance. My throat tightens and my hands shake hard. Some of the restaurants by the shore had already been sodden with water, the windows and doors broken.

I start sprinting as fast as I can, my heart thundering. Adrenaline shoots through my veins, and my legs burn like fire. I look back to see the wave slowly dying down, only to realize another wave was coming.

I’m going to die. I’m going to die.

That is the only thought that blares through my mind. I even envision what my last words might be, and the grief that would be inflicted upon my family. I hear the loud thrashing waves behind me and dread engulfs me. My legs feel like jelly and my lungs are desperately gasping for air, but I know I can’t stop.

I soon come upon an abandoned shop, spot a bicycle, and hop on it, pedaling away furiously. My muscles scream in agony and the worst part is that I don’t even know where I am going. But I just keep pedaling, hoping to escape somewhere up the hills that separated the lower and upper part of the remaining San Francisco. I silently pray that my family and I will survive. The wheels of the bicycle squelch on the muddy sidewalk as I hear the intense rushing of water in hot pursuit. I look behind me, and my heart skips a beat at the sheer immensity of the colossal wave looming over shops along the shoreside street.

Suddenly, the bike lurches forward, throwing me to the ground. My head hits the hard cement sidewalk and a sharp pain instantly strikes me. I feel wet, sticky blood on my tongue. I feel like my entire head has shattered. All I can think about, though, is the surging water in the distance. It is speeding towards me and tears of helplessness fill my eyes.

Goodbye.

I think as my paralyzed limbs refuse to move.

My entire body throbs with pain and my vision blurs. Suddenly, I see faint silhouettes running towards me.

My whole body shakes with angst. Just as my vision dissolves, I hear the rushing water coming closer and closer. Grandpa’s sketchbook suddenly falls out of my loosening grip. I reach for it blindly, but the wind blows it away, towards the gushing water. A lump forms in my throat and my chest tightens. All of his memories were gone just like that, instantly. Then, rough hands grip my arms and drag me out of rushing water. I black out.

I feel like I’m floating.

Am I dead?

I wake up groggy, sitting on a soft platform, and prop myself up. I hear the voice of my grandfather and another unfamiliar voice.

I open my eyes. At first, my vision is blurry with slashes of black. Slowly, it clears and I see my Grandpa and a doctor in front of me. The doctor looks calm, while my Grandpa looks very concerned.

“Luckily, your grandson was rescued by a crew facilitating evacuation. Your grandson is getting better. There is no need to worry, and you may visit him whenever you like.”

“Thank goodness you're alive!” Grandpa says, and rushes forward to embrace me. He smells of the putrid water flooding the city as well. Soon, I pull apart and collapse on the bed, my joints weak, my muscles sore. I look outside of the door, a narrow corridor surrounded by slick white walls. At the end of the hallway, there is a large window which shows buildings and skyscrapers hovering above the roads crowded with traffic, untouched by the flood.

I must have ended up on the other side of San Francisco.

I prop myself up, and I see Grandpa gazing at a beautiful painting of nature, shaking his head sadly. The picture takes my breath away. In the painting, there is a long red bridge, standing on top of the crystal water. The sky was a brilliant azure blue, with the sun shining brightly. In the painting, the appearance of the ocean is priceless, clearer than crystal.

After a few moments, I’m about to ask what it is, and suddenly, I spot the title of the painting. It reads: “San Francisco, 2022.” Every time I see a picture of past San Francisco, the sublimity of the image is always shocking for me.

How is it possible that the San Francisco that was once so beautiful had turned into such an atrocity in less than a century?

The vibrant streets filled with culture that Grandpa had told me about have been annihilated by the flood. Buildings that once stood tall have been demolished. The little remains of the past have vanished. Despair fills me, and I think: Oh, what have we done?

I’m on the verge of collapsing, and I lie back in bed, exhausted and battered. My eyelids flutter, and they soon close. Abruptly, dizziness overtakes me, and I’m struck by incoherence. I decide to let go of all the overwhelming thoughts and anxiety I have accumulated throughout the day.

That night, I dream of a vast, cloudless blue sky and a brightly shining sun above a pristine ocean, its waves gently lapping at the shore. I dream of the ocean, alive, mesmerizing, and boundless. I dream of what the ocean is always meant to be. My head spirals with dizziness and the vision is over. I reach for my dream of what everything should be like, but it is just out of reach. Then, I wake up. I look out the window and find filthy waves crashing down on a shore scattered with garbage, my heart heavy with grief and longing.

Luke Sibbald, Appleby College, Grades 7 & 8

Fifteen years old and chasing an impossible dream. That’s what everyone thought. Everyone except Elliot Rivers, a young boy who knew he was destined to become an artist. But there was just one problem. He was achromatic, so badly colour-blind he could only make out grey.

On a stony beach at the Bottom of Jellybean Row, in St. John’s, Newfoundland, sat Elliot, painting what he could see in the horizon.

Every detail is accounted for, and I’ve even tried to add in colour, whatever that actually means, thought Elliot, sparing a quick glance at the tubes of paint below, which to him shone in shades of sharp iron and silvers. He gazed back at the painting, and then at the island, which he was painting.

“Yes, it’s perfect,” said Elliot out loud, and he was content.

His father ran an art exhibition in the summer, which people from all over would come to see. The due date for submissions would be closing soon and Elliot wanted one of his paintings included. But every year he tried, he could hear the voices.

“Too much rainbow.”

“Childish!”

“Did you mean for it to be like that?”

He planned to leave the painting in his father’s art station for the night, so that it could dry. He hurried up the slanted street with his painting under his arm. He stopped to open the door, when he noticed a figure inside. It was his tutor, the one who always criticized his work.

I must stay out here, or else he will see my painting and criticize it, thought Elliot. I never did tell him about my condition with colours. He doesn’t understand.

But I need to get this painting inside. Elliot began to pace.

“But—ARRGH!” he yelped, and to his surprise, out loud, and before he could realize what he had done, the door handle was starting to turn.

“Elliot!” his mentor cheerfully remarked. Elliot’s response was simply, “Oh… hi, Professor Williams.”

“Speaking of that lovely painting you’ve got there, I’ve got a question to ask you,” remarked Professor Williams. “How do you… get your inspiration for the colour in your works?”

This was the dreaded question Elliot indeed knew was coming, but he was surprised to hear it from his professor, and he was unprepared to answer.

“They... they all look the same,” stammered Elliot, fearing he was going to break into tears. His professor just smiled, then spoke words that Elliot never expected to hear, least of all from his mentor.

The next day was the judging. Each painter would separately present their artwork to the judges, and then after all the pieces had been judged, the judges would collectively pick five artworks to display.

Walking into the room, Elliot was surprised to encounter a crowd of people all shuffling to try to move up in the line. Allowing himself to gaze at their artwork, he could only begin to imagine the deep scarlets, magentas and greens that were encrusted harmoniously on to their canvases. He shamefully hid his painting, facing it towards his body and hoped that no one would come to question what he had made or why.

At last, it was his turn to progress. He entered the room to find four judges, along with both his father and his mentor.

He propped his painting against the large wooden easel in the middle of the room.

The judges looked at the painting for a long time—then at him, then at the painting, then back to him, then at the painting, before they finally asked with a confused voice, “Tell us about what you made.”

“I painted the island off of the shore, the sun shone beautifully in the sky that day, and I thought it would make a very pleasant picture,” mumbled Elliot, very aware of how the judges were staring him in the eye.

“Alright. Well, good job.”

Then Elliot heard one of the judges whisper, “I’ve never seen such brilliant colours made into a mess.”

Then he heard another say, “I told you Stanley, he’s not good enough.”

For Elliot, that was heartbreaking. He went straight home instead of waiting to hear the results. For the first time in his life, Elliot was lost, in a deep pit that he convinced himself that he hadn’t needed to fall in if he hadn’t been so foolish.

Later that night, with his head tucked under his pillow, he heard his father arguing with someone. It must’ve been his mentor, and he was only more confused when he listened in.

“Stanley, Elliot’s art is so unique and full of life. Why don’t you see potential in him?”

“It is, but he won’t tell anyone he’s colorblind. It makes it seem childish.”

“Goodnight, Stanley. I hope you think on this.”

“Goodnight, Williams. I think I must.”

That evening, Elliot got little sleep and found himself turning and tossing throughout the night, and when he woke up in the morning, he was pale in the face.

Downstairs, he found a note: “Meet me in my office – Father.”

Once in his father’s office, he was told to sit.

“Yesterday one of our donors’ paintings got lost on the voyage, and we needed a new painting. Elliot, although your painting is the shade of crippled fungus, it shows a path of resilience, a strong determination to get up and try again. Elliot, I’ve thought about it. Your painting shares a story that no other can begin to rival. Elliot Rivers, I’d like to ask for your painting in my gallery,” his father explained.

Then he understood. His art may not be like everyone else’s, but he has experienced life in a way that most artists never will. His art is unique.

Beautiful… in its own way.

Harper Reid, Kempenfelt Bay School, Grades 7 & 8

I check my phone. 11:59 AM. The class list should be posted any minute. I jog through the halls until I find myself in front of the drama room. I check my phone. 12:01 PM. There is a group of girls crowded around the bulletin board, and when they look up and see me, they burst into fits of giggles. I push my way through the crowd, and finally my eyes land on the sheet of paper. I scan the entire list for my name, yet I see nothing. Confused, I look again, and this time, I see it.

Zach – to play the role of Rachel

I genuinely hear myself laugh — that’s the female lead in the play! That can’t be right. I look again.

Zach – to play the role of Rachel

Oh my God. This can’t be happening. This is why the girls were laughing, isn’t it? No wonder! I’m a guy, I can’t play the role of a girl! Well, I don’t see why I can’t, but the rest of the school and TikTok will definitely ruin my life if I do this, even though it’s the biggest role I’ve ever gotten and I literally sing along to her solo in the shower—no. That’s not something I can think about right now.

I snap out of my head, and realize that the crowd of laughing kids has doubled in size, and all I can do is glare at the sheet of paper, the words staring fiercely back. I try to take deep breaths, but I can’t slow my heart. I bust through the crowd and run through the halls.

I don’t know where I’m going but I know I couldn’t stay there. Not where I felt like the giggles of freshmen through senior students would swallow me whole. My legs are taking me somewhere — a lot faster than they’ve ever moved before. Maybe I could just drop out of theatre and become a track star.

I burst through the doors of the school, dash down the steps and collapse onto a patch of grass by the crosswalk. I’m too tired to go home, but I certainly am skipping the rest of the day at school. I pull a sandwich out of my lunchbox and watch the passing cars. As I sit and eat, I wonder, “Why would it be bad for a boy to play a girl role? It’s acting, and isn’t that the point? And why should people laugh at me if I get to wear a pink shirt instead of a blue one? Pink is definitely the superior colour.”

After I’m finished eating I scroll on my phone for a while. Before I know it, it’s the end of the day… and it’s time for after-school clubs. I gulp. If I show up to theatre, they will laugh at me to my face, and if I don’t go, they’ll mock me behind my back. I may as well hear what they have to say about me. I get up, and head inside our school.

Hoodie yanked over my head, and drawstrings pulled tight, I stumble through the halls. I have to keep a low profile so as not to be seen, but I also need to get to the safety of the theatre. Miraculously, I push through the door to the theatre without once being made fun of by a kid passing by. Weird. I’m a few minutes early, so there’s only one girl here, reading a book with her Airpods in. Macy, I think her name is. I try to slink quietly into a corner, but before I can fully disappear behind a stack of chairs, she looks up, and our eyes meet. Uh oh.

“Hi,” probably Macy calls across the room. Or was her name Jenna? Anyway, it doesn’t matter. She's talking to me… or maybe there’s someone behind me. I gesture my pointer finger to my chest, questioning if it was, in fact, me that she was talking to. “Yes, you. There’s no one else here!” she replies.

Great. Now she thinks I’m dumb. “Hi. What do you want?” Oops. That was harsher than I meant to be. I prepare myself for her to criticize me.

She gives me a confused look. “I was just saying hi. I also just wanted to say that I’m the male lead, so… I guess I’m saying that you’re not alone.” Then, she adds, “Like, with bullying stuff.” Her face flushes. And then a thought pops into my head—our names were next to each other on the list! Maybe I’m the male lead and she’s the female! I have to go talk to Ms. Garcia! I can’t help but grin as I leap to my feet and run towards her office.

I fling open the door while shouting, “Ms. Garcia, Ms. Garcia!”

She spins around in her office chair. Sighing, she replies, “Who died?”

“The cast list is messed up! I’m supposed to be Mike! And the girl…” I trail off. Was her name Jenna or Macy? Think! “Jenmacyna” I slur, and Ms. Garcia raises an eyebrow. “Yeah! She’s supposed to be Rachel! And… and… yeah.”

My heart sinks when I see Ms. Garcia shaking her head. “No, I didn’t make a mistake with the list. You both are incredible actors and singers, so you had to be leads. But Grace sings alto, which is why she is cast in lower parts.” GRACE? Wow, I was so far off. And she doesn’t even look like a Grace! “You have a higher voice. And that wasn’t the only factor. I have my ways.” She says this last part with a mischievous grin on her face.

I sigh and nod, heading for the door. Before I pull open the door, she stops me. “Wait. Can you please just trust me that I’m not trying to ruin your life? I know that you’ll do amazing.” I nod again and head back to the theatre.

The rehearsal goes by better than expected. Sure, there were some rude jokes and name-calling here and there, but whenever it got to be too much, Ms. Garcia shut it down. Maybe this won’t be so bad.

For three months we rehearse twice a week for two hours after school. It’s surprisingly fun? I say it as a question because seventy percent of the time other kids are being a pain in the

butt, and not letting me live down the fact that I play a girl. But the other thirty percent, I’m on the stage, pretending to be a girl… and I like it?

I’ve always been into pink and “girly” things like Taylor Swift, but there’s always been a part of me wanting more. Everyday, it’s like I have to just stare into a glass box filled with all the things I wish I was allowed to like… like nail polish and makeup and having slumber parties with girl best friends. I don’t have many friends to paint my nails and the only sleepovers I’ve been to feel like The Hunger Games. And this glass box… It’s just there for me to look at. Every time I try to get inside, I just get pushed out and end up hurting more. That’s why I have to crush it as the female lead. Maybe I won’t be weird then?

Finally, FINALLY, opening night rolls around and I am bursting with excitement and nerves at the same time. If I do horribly, the bullying will get worse. But if I do amazing? A guy can dream.

And then… I do amazing. Not like, “Oh wow, there’s this little skinny guy up on a stage singing a merry little tune kind of good.” I CRUSHED it. As I finish the last note in the final song, and take a bow, the crowd goes wild. I smile so wide that my mouth begins to hurt.

I practically skip off the stage and wrap Mac—no. Jen—no. Grace in a hug.

“We did it!” she half-scream half-whispers into my ear, and I begin to laugh because her fake beard has almost completely rubbed off.

As I walk backstage towards my changeroom, I am engulfed in many, many “great jobs!” from my castmates. And then something happens that makes my whole face light up.

I hear one extremely popular girl whisper to her boyfriend, “Honestly, I kind of feel bad for pestering him. He did really great.”

“Yeah,” he replies, “I might try out for a girl next year. I know this sounds cheesy, but when Zach was up there, he just embraced himself and didn’t care about what others think. I think I might try out for a female role next year.”

I grin, bigger than the one onstage. I inhale, and then breathe out a satisfying breath. Mission accomplished. Glass box shattered.

Valarie Yip, Lauremont School, Grades 7 & 8

Dogs aren’t allowed to be out of the zoo. How on earth did he escape? I need to take him back before the policía finds him or the poor thing will be treated as a stray and get executed. But he’s running so fast and I can barely keep up with him. Where is he going anyways? It’s been almost 30 minutes and I’m literally at the edge of the City.

I have never been this close to the City boundary. The High Council forbids us from travelling outside the City for our own safety. There are many homeless people lurking within the shadows beyond the City. I have never met any homeless people before but they are said to be ruthlessly dangerous savages.

“WOOF! WOOF!” he turns around and begs me to keep up. I pick up my pace as he sprints off again. I am now officially outside of the City. What have I done? This perilous journey into the unknown has to be the worst mistake I’ve ever made. I must have broken at least a dozen rules by now. I am only two months away from getting my own pod. Every summer, all 13-year-olds are presented with their own pods. I can hardly wait to move away from my parents and live by myself.

Where am I? Everywhere I look, there is vegetation. I look up and see the blinding sun. I turn around and all I see is a sea of trees, stretching for miles. The dog is nowhere to be found now. I am all alone, lost and scared in a strange and unfamiliar place.

“RUFF! RUFF!” I follow the sound into a small clearing. That’s when I see him.

Kneeling next to the dog is a boy. The dog is now running circles around him, wagging his tail and licking the boy’s face. When the boy sees me, he stands up. The first thing I noticed is that he is about my height and that he is not wearing his uniform. He has a strange and peculiar look about him. He has long braids down his back and feathers sticking out of his hair. He is wearing some sort of animal hide “jumpsuit” with matching embroidered boots. I have never seen anybody like him before. Could he be a homeless person? But he looks far too friendly to be one.

“Hey you! Who are you and what are you doing here?” I am freaking out on the inside but I speak loudly, trying my best to sound brave. I also speak slowly in order to enunciate every syllable, in case he doesn’t understand English.

“I should be asking you the same! This is our land and you don’t belong here. Your kind lives in the City of Pods. I heard all about your kind. Who are you and why are you here?”

“I’m Valarie and I... wait, how did you know I’m from the City of Pods?”

“First of all, your kind always wears the same boring uniform. Second of all, everyone here knows me. I’m Kevin, the great-grandson of Grand Chief Tecumseh. Are you here to hunt us again?”

I don’t understand. I’m not a hunter. Who’s hunting them? “Hey, what do you mean?! I’m not a hunter. I was just trying to rescue that dog and somehow got lost.”

“Well, Mufasa doesn’t need rescuing. He’s my dog and he lives with me.”

“What?! The High Council has straight rules against pets. Animals are only allowed in the zoo!”

“Well then, it’s a good thing that I don’t live in the City.”

“So where do you live? Aren’t you one of those homeless people that the High Council warned us about?”

“Just because I don’t live in a pod like all of you City people, it doesn’t make me a homeless person. In fact, I live together with my family and friends in a very nice community. You can come visit and see for yourself. My HOME is not far from here.”

My brain tells me not to go. The High Council warned us repeatedly to stay away from homeless people. These savages are dangerous. I could lose my pod for breaking the rules. But my heart is curious and something about him tells me Kevin is sincere. Still I’m not sure if this is a risk I should take.

“You know, I don’t bite if that’s what you’re thinking. Anyhow, I’m going home now because I’m starving. Have a nice life in your little pod!” With that Kevin turns around and starts to walk off. “Come Mufasa! Good boy! Let’s go home!”

“Wait! Kevin, I’m coming!”

I was lost and desperate so I followed Kevin deeper into the heart of the forest. After a while, we emerged into a sunny clearing.

I am at a loss for words, which is unusual for me. But I don’t know how to describe where I’m at or what I’m seeing. I think I’m in the middle of an encampment. There are tents everywhere with people hustling about. It’s unorderly but not chaotic. People laugh and engage in conversations with each other while they work and small children run around giggling. It’s noisy but it feels strangely welcoming. Suddenly, a pungent aroma whiffed into my nose.

“It looks like we’re having chili for dinner. You’re in luck! Auntie Patty makes the best chili around here.” Kevin nodded over at an old lady nearby who was standing over an open fire and stirring a gargantuan pot.

“Are you a good cook?”

“Cook? No, it’s dangerous Kevin! The High Council forbids it. We have our breakfast and lunch at the school cafeteria and have our dinners delivered to our pods every night. The High Council makes sure our meals are purified and meet our daily nutritional intake requirements.”

“The City of Pods has so many rules. We all know how to cook and we’re free to choose what we eat.” Kevin said, as he led me inside one of the bigger tents. “Great-grandpa, this is Valarie, a podster. She followed Mufasa to our reserve.”

Grand Chief Tecumseh has a scrawny physique but like Kevin, he also has a friendly face. He hugged me and welcomed me to the community. “A long, long time ago, I used to live in the City too. Back then, it was called Toronto and people needed to work to earn their money to buy their house. But then, some people could not afford to buy a house and they became homeless. As time passed, more people became homeless and lived on the streets. At the same time, there has been more extreme weather due to climate change. Every year, we have more and more homeless people dying from the scorching summers, frigid winters or drowning in the frequent flash floods.”

“How come I never learned about this?” I might not have done well in history class but I swear this is the first time I’ve heard about this.

Grand Chief patiently explained, “It was a very painful memory. Everyone tries to forget so no one wants to talk about it. To solve the homelessness problem, the High Council became responsible for providing housing to all citizens. Given land is limited, the High Council took back all the land and built pods to ensure that every citizen has a place to live. It was a great idea at first but then other problems arose, forcing the High Council to keep adding more rules. For example, citizens are not allowed to cook in their pods for fear of fire hazards. Citizens are not allowed to have pets in their pods for fear of spreading diseases and pests. A few of us felt that this was not how we should live. Our pod felt more like a prison than a home. We started protesting for our rights and our freedom but the High Council argued that their way kept everyone safe and sheltered. In the end, a group of us left the city and moved here to start our own community where everyone has the freedom to live the way we choose to. While you might think of us as homeless, the homes we build mean so much more to us than your city pods. Our home is where we live, with the people we love, doing the things we love. I know this is a lot for you to process but I sincerely hope that you would consider staying with us. For the first time in your life, you have a right to choose and I hope you choose us. Get some rest and let us know your decision in the morning.”

I was stunned and dazed. As I lay there under the clear night sky, I gazed up into the scintillating stars and pondered where I should live. The cool night breeze gently caressed my cheeks. The nightingales’ lullaby serenaded the night as I floated away into darkness.

Aiden Matthews, St. Mildred’s-Lightbourn School, Grades 7 & 8

As I walk down the spiraling stairs of the library I see the delightful librarian, I complimented him on his formal attire I then saw his little dog, but for some weird reason there was a lot of fog But I didnt perfectly see the dog, and all I could see was my shoe I saw that the dog was a tiny teeny little bit blue. Sky blue, dark blue, baby blue, electric blue I'm not sure which blue the dog was

But the dog was blue, and the dog was big I slowly walked out of the building and the warmth disappeared from inside my body

My limbs soon became very numb I couldn't move and I couldn't linger I saw the dog again and it was blue. It was cobalt blue. I laughed and laughed until I couldn't breathe but the bulldog then again disappeared I waited for two days, and I went to the library again The man was there as calm as ever his eyes showed that he cherished these books and that he was clever I noticed that he must have worked a great endeavor. The shelves were stacked with books and statues

But the statues were of dogs, blue dogs I asked the man why blue? but he left the building without a clue I wondered day and night where the dog was Until I heard a small sound, I looked out of my window And all I saw was a tiny little red crow I followed it but to my surprise He led me to the blue bulldog

And beside the blue bulldog was a black leash with the librarian He looked up at me, I got startled and spilled coffee on my electrical bill I went to the doctor the next day because I felt very ill He then made me lick this purple popsicle stick I said I love the color purple and he said that it was blue I said no it's purple, and then he put me in front of an eye exam I put my foot down and said no, I then found out I was just red/green color blind I went back to the library with my new glasses and saw that The dog was not blue no, He was a very light purple.

Once I noticed he was a beautiful color I found I should do something new I like the color purple too!

New me

My hair might get duller

But I will try and dye my hair a new color

A different color, orange.

Ishaan Grotra, Appleby College, Grade 10

I slip off my shoes and carefully push open the front door. It's unlocked, just as grandmother always left it every Sunday. The warm smell of cardamom, saffron, and sandalwood wraps around me like an unspoken welcome. The scent belongs to this house, to Sundays, to her. As I walk towards the kitchen, I can hear the sharp whistle of the kettle releasing the rich scent of masala chai and the gentle crackle of pakoras frying in hot oil. Here, time moved at its own pace, measured not in minutes but in the rhythmic creak of the old ceiling fan and the steady hum of my grandmother’s voice as she sang.

She sang every Sunday, her steady and unshaken voice floating through the house. I never knew her words, and she never knew mine. I was born in Canada. My parents spoke Hindi to each other but English to me, slipping between languages as if expecting me to follow. But I never did. I could catch familiar words in a sea of unfamiliar sounds, but they never felt like mine when I tried to speak.

Grandmother only spoke Hindi. I only spoke English. Our conversations were a series of gestures and smiles stitched together by my parents’ translations: words passed back and forth like an echo, fading a little more each time. But when she sang, we didn’t need translation. Her voice carried across the room, removing the language barrier between us. Some days, the melodies were bright and full, weaving between the sound of rolling dough and the clatter of steel cups. Other days, they’re softer, laced with something heavy I couldn’t name. I would sit at the table, watching her hands move with the rhythm, wondering what the songs meant and what memories they held.

I never asked. Maybe I was afraid of the answer, afraid that even if she told me, I still wouldn’t understand. So, instead, I just listened and sometimes sang along. It wasn’t perfect; I didn’t know the words, only their shape. But in those moments, it didn’t matter. In song, the space between us didn’t feel so vast. One Sunday, the house was louder than usual. The kitchen was packed, voices overlapping as my relatives from India filled the space with stories and laughter.

I sat at the table, listening but not quite following. The conversation moved too fast, words blending before I could separate them. I nodded along anyway, smiling when everyone else did.

“You don’t understand, do you?” my aunt Maasi teased, nudging me playfully.

A few chuckled, and their laughter weighed in my chest.

“I understand some,” I mumbled, shifting in my seat.

“Ohh, acha!” My uncle leaned in with a grin. “Then tell us, beta, how’s your Hindi these days?” Winning Entry

I hesitated, the words forming in my head before slipping out clumsily. “Uh… Hindi, um… bohot… accha?”

It was wrong. I could hear it as soon as I spoke. The pronunciation felt stiff and unnatural, as if I was trying on a shirt that didn’t fit.

That was enough to send them into laughter.

“Ay, wah! So cute,” my cousin smirked. “His accent is like a firangi.”

“He’s forgetting his roots,” someone joked, shaking their head.

I forced out a small chuckle, pretending it didn’t bother me, but heat rose to my face. I stared down at my plate, suddenly hyper-aware of how out of place I felt.

At school, it was the opposite.

There, I was too Indian.

“Does your house smell like curry?” someone asked in third grade, scrunching their nose. I didn’t answer.

“Bro, wait. You don’t have an Indian accent?” a classmate in middle school said it was like some achievement. “You actually sound normal.”

I was always too Canadian to belong.

Too Indian to fit in.

I felt like I was living between two places, never fully stepping into either. Like I was standing on a border I couldn’t cross. And yet, every Sunday, grandmother sang to me. In those moments, the lines didn’t seem so sharp.

One Sunday, something was off. The warm smell of turmeric and cardamom still greeted me, but grandmother seemed different, quieter, and heavier. Later that night, my parents sat me down. “Your grandmother, she’s getting weaker,” my mother said softly. “The doctors say it’s her heart.”

I nodded, but my stomach twisted. I’d spent my life feeling like there was always time: time to learn Hindi, understand her songs, and finally cross the invisible space between us. But now, it was slipping through my fingers.

The next Sunday, I went to see grandmother again, but this time, I felt like a stranger walking into a familiar world.

I sat beside grandmother, watching her lips move around the lyrics of the song she

always sang, wishing I could hold onto them, trap them in my hands before they slipped away. But they floated past me, just as they always had, lost in a language I didn’t know.

That night, in the silence of my room, I did something I had never done before. I opened my phone and typed: How to learn Hindi

The first lesson started with simple phrases. I whispered them under my breath, my pronunciation uneven, my tongue tripping over syllables that should’ve felt like home.

I kept going. At dinner, I asked my parents about grandmother’s songs.

“That one?” my mother said, taking a sip of chai. “It’s about resilience.”

My father added, “It’s about pushing forward, even when the path is unclear.”

I let the words settle in me, like something I’d always known but never truly heard.

Over the next few weeks, I listened more carefully. I memorized the melodies, even if I didn’t fully understand the meaning. I found myself humming them when I was alone, letting the notes guide me like a bridge between us.

One day, I found something I wasn’t expecting. Buried deep in the back of my parents’ closet, beneath old photo albums and rusted bangles, was a cassette tape with grandmother’s name written on the front in faded ink. I stared at it, my fingers tracing the letters as if touching them would bring me closer to the version of her that had existed before I was born. I dusted off an old cassette player in the basement and pressed play. Her voice that filled the room, young, strong, and unmistakable. Not just singing — performing

Grandmother had been a singer.

For the first time, I saw her beyond Sundays beyond the kitchen. I pressed play again. And again.

Until I could finally sing it back to her.

Monday after school, my father came unexpectedly to pick me up. As I sat in the car, my father’s tired eyes stared at me, his face heavy.

“She’s in the hospital,” he said quietly. “We’ll go see her now.”

The car ride was silent.

When we arrived, the room smelled of antiseptic, not chai. The steady beeping of a heart monitor replaced the hum of the ceiling fan. Grandmother looked small in the hospital bed, her hands resting on top of the blanket, still. I sat beside her, my throat tight. I wanted to tell her that I had been learning. That I had been listening. That I finally understood. But words had

always failed us. So instead, I sang. My voice shook, the words slipping between English and Hindi, my pronunciation still rough, my breath uneven. But I sang anyway. Her eyes fluttered open, just slightly. For a moment, just a moment, she smiled.

And then she was gone.

In the following weeks, I found myself humming when I was alone, the songs curling around me like an echo of something I had almost lost. I listened to her tapes again, not out of sadness, but because they felt like a part of her, I could still hold onto. I learned the lyrics, slowly, carefully, not perfectly, but with pride. At school, the comments didn’t stop. Someone still said, “You don’t even have an accent? You’re basically white.”

Another still joked, “I bet your house smells like curry.”

But I didn’t laugh along this time.

Because I wasn’t standing on the edge anymore, afraid of what people thought.

I had crossed the boundary.

Because identity wasn’t just about language. It wasn’t about fluency or pronunciation or being enough of something. It was about carrying her voice forward and finding my own. The words, the history, the songs I had once felt so distant from, they weren’t foreign anymore.

They were home.

Eloise Bramer, The York School, Grade 10

Can you hear me when it feels like I’m shouting at the sky

Your face unmoving unchanged

Can you hear me

Through my sentences that Dance and flourish on a page

Bringing life to the tales of Greek heroes

Or is all you see the way I look as I age And the places where my maturity shows

Though I can easily recite endless facts

Of the world that surrounds us and of poets past

You still consider me less and try to put my words last

Can you hear

My rasping, broken voice

Lost, screaming the too common stories like that of Atalanta, surrendered to the wild by her father who desired a son, Hatshepsut, first female pharaoh erased from history by the jealousy of men, Hina, harassed by a man over and over, until her husband decided he had gone too far

We repeat and recite Their struggles and stories

Hoping we won't have to fight

To be a statistic in your movies

Pretend we don't know

You're impatiently

Pacing

Waiting

Praying

For the day when we Throw our books into the flames

That feed your fragile ego

Let me go

Forget thriving in your fishbowl, In your claustrophobic display, We’re outgrown, Prying at the seams

And at the seeds of hope that one day Winning Entry

Our lives won't be diminished to A political decision

By those trying To fan the flame

For a popularity gain

You’ll paint the roses red And me a villain

But you won't lose your head

You’ll watch the world burn And throw us in it

If you set me aflame

At least there will be light

Then maybe other women

Will feel safe walking alone at night

You may stake me out

But at least, I’ll know I can guide those who’ll come after me

And

We won't have to Survive another day In a man's world

Can you hear us

When the only acceptable sound Is the shrieking cries

Of our burning mouths

And what's funny is Though I’m fighting To be heard

This poem Doesn't pass The Bechdel test.

Adhya Chandradat, The Country Day School, Grade 10

My name is Victoria Caldwell. I am thirty-two years old, and I was born on the seventh of January, 1962. By picking this up, you have consented to listen to my story. I will not beg you to believe the words that I say; however, if you do, I thank you. A woman’s truth is often dismissed.

My story began in a small room, with a maze of desks, half-finished lines of code, and deserted coffee cups. Wires jutted out from the walls like the roots of a tree pushing through cracked pavement. The wires and the papers seemed to have more presence than I did. I’d walk in every day, and the only other women I’d see were the secretaries. They’d be off chatting, fetching coffee, and doing everything they were told. I, on the other hand, would move to my lonesome desk, isolated from the men’s collaboration in the tiny space. Although no one would ever explicitly say it, the silences when I’d enter the room and the sideways glances spoke louder than words ever could. I could’ve become a teacher or a nurse, but I ended up working with computers to perform research and expand our understanding of how they worked.

I was nineteen when I began working at the company. Young, but I was already doing more than most. The process was simple: Refine, test, debug, and do it again. I always had an aptitude for mathematics in school, so it only made sense to put that to good use. I remember learning about what a computer could do. It seemed beyond what anyone would ever dream of, and there I was, designing and programming.

We had books full of hastily scribbled notes, and my lungs were filled with chalk dust from the times I’d stand up and handwrite my code on the scrawny chalkboard on the wall.

Most girls my age had gotten married to their high-school sweethearts, but I never cared for that. I talked myself out of that idea when I was fourteen. All I wanted was to put my brain to work, and that was enough.

I could perform iterations faster than anyone, my hands moving nimbly and swiftly across the papers. My mind was the sharpest, and I felt that I was inching closer and closer to a discovery. I was right. Sorting through vast amounts of data efficiently was a daunting task, but I had found a connection. Patterns have always come easily to me, and this one emerged on the chalkboard. It seemed like an overnight success, but it took me two years to work it out, on top of my actual workload.

I was twenty-four when I crafted the sorting algorithm, using quicker methods that would save time and money. I found it while repeatedly checking a large data set for a condition, but I could not get through it fast enough. Then it hit me: break up the set into subsets, and sort through those to find anomalies, before merging them back into one set. It worked well. So well that the company wanted to sell the plans to businesses and generate a massive profit.

The only way anyone would take it seriously would be if the algorithm were created by a man. I wrote a paper to explain the function, entitled “Optimizing Data Flows for the Microprocessor Era.” This was credited to Warren Whitaker. In the midst of the cluttered desks, there he was, bringing me coffee on the days when I would stay at work so late, that I wouldn’t end up going home. The other men never so much as glanced at me, but Warren would always strike up a conversation. Always so intrigued to know what I thought. He was altruistic, and we had bonded over the fact that we were the youngest in the room, him being two years my senior.

I noticed his glances at my work, but I’d always counter my cynicism with, “You’re just being silly, Victoria.”

He listened intently when I spoke to my boss about my work, but I brushed it off by remembering my mother’s words: “People take notice of good work.”

I was suspicious, but in a world like this, I was taught to ignore and accept. If anything happened, it must be my fault. I now realize that the signs were always there, but I was “too naive.”

I wasn’t naive, I was conditioned by the system I was raised in.

It was too late when I realized his kindness was simply a ploy. He was the second-best in the room and the first one the company decided to pawn off my work to. Warren’s ambition had proved to be stronger than his loyalty.

I vividly remember the words, “This is bigger than you, Victoria.”

The company said I would be compensated accordingly. A payout of ten thousand dollars and a modest salary increase for me—if I signed away my intellectual property rights. I didn’t know then that the “standard contract” would erase my involvement and discovery, leaving everything transferred to Warren. They told me that I would be credited “internally” and that the agreement was “just a formality.”

I recall my mother telling me in her no-nonsense tone, “I need you to be mature. We do not have any time for these antics, so go along with it. Take the money, Victoria.”

It was never about the money.

It has been five years since I made the decision, and it has been destroying every single part of me. I began working at the bank, and tedious can’t begin to describe my new job.

One day, Warren stopped by the bank to make a massive deposit. He refused to make eye contact. He saw how upset I looked, how maddening this whole ordeal was.

I had to forget my past, forget my involvement, forget it all. This contract would effectively silence me for life, as I was forbidden to speak of its creation and details.

This brings me to why I have written this. I lost something great, and it should have been mine to hold. The company pried my work from my delicate fingers, leaving me to clutch on to the lingering weight of what I once had. It was never intended for me to receive credit, no matter what I did. The world wouldn’t accept me, or my work.

So now I ask you, was it just? I know it is radical for me to be asking this, but if you had the gall to pick this up, then on some level, you must believe me.

The absolute truth is that I was never meant to be behind the scenes in my own story. The company wanted me subjugated because they could never fathom a woman leading us into the future. I refuse to be silent. What I have done, what I have created, is not just a series of calculations, it is proof of my potential, and the brilliance that every woman is capable of. The company was right when they said that this was bigger than me. This is about every voice that has been drowned out. This is about every woman who was told to stay in her place because she didn’t fit what they wanted. This is about every single mind that has been erased from what they chose to include in history.

I am writing this because I will not let them take any more from me than what they’ve already taken. My silence was theirs, but my words are mine. You can choose to ignore me, to dismiss me as a bitter reminder of the past, but if you truly believe me, then I command you to ask questions of history.

Question the systems that erase people like me. Who has power? Who controls the narrative? Who benefits from secrecy? Make demands. Destroy the social structures that enable those in power to thrive in an environment that diminishes the accomplishments of others.

They took my name off of my work, but they cannot take my name off of this.

My name is Victoria Caldwell.

I am thirty-two years old, and I will not let them define me and my legacy.

Ashley Smith, St Mildred's-Lightbourn School, Grade 10

An adaptation of Rudy Francisco’s poem “My Honest Poem.”

Hi my name is Ashley Adele Smith, I was born on November 8, 2009.

I hear that makes me a Scorpio.

I’m 5’9, with blue eyes and blonde hair. I weigh 130 pounds and I don’t know how to whistle.

I’m still learning how to stop apologizing for things that were never my fault, to let go of burdens I didn’t pack myself, to understand the things given to me but not deserved.

I’m often stuck— walking the same path as yesterday, and today.

I like iced coffee— maybe too much.

I’ve been told I’m kind, considerate, sweet, and responsible.

I don’t find it hard to be.

People say I have ocean eyes, golden hair, and a heart that gets scared easily.

Secretly,

I have Post Traumatic Stress Disorder.

I never knew I would be writing a victim impact statement at 13.

Honourable Mention Entry

I never thought innocence would be taken from me so quietly.

Sometimes, I feel like I'm her again with a loud voice of disappointment.

There wasn’t always a trusted guardian in my life— a father meant to be a guide, but a daughter taken for granted.

The hands that were supposed to protect and comfort me.

And to be honest, sometimes I wonder what people would think or say if they read my old chapters— the ones with damaged pages and scribbled-out lines, the ones I hate to flip back to.

Sometimes I wonder if they’d still look at me the same.

I’m afraid

I'm afraid that without my second face— the one I’ve learned to wear so well—

I’d be raw, too plain, I'm missing my mask.

Hi, my name is Ashley Adele Khan.

I enjoy spending time with my sisters, eating pints of brownie batter ice cream,

Playing the notes of my feelings on the piano, and finding any chance I can to spend time with friends.

I don’t allow myself to put down the weight of blame, to rest from carrying things that were never mine to begin with.

I have friends with time limits, tears that come to my eyes too often

My hobbies include postponing tomorrow’s promises, balancing oars, coating my lashes with 3 coats of mascara and playing my social roles as best as I can.

I know.

I know. I know there’s still a little girl I’m looking down to, asking why her last name changed.

I know she’s come so far.

So many things she’s learned

And I know

She still loves her friends and family. She still hugs Mousey at night. She still loves pomegranates. And she got away from him— something she thought would never happen.

Aliya Makada , Hillfield Strathallan College, Grades 9 & 10

I’ve never felt good at anything.

Math, painting, sports, driving, sewing–even being in my own body was hard for me. I had always been envious of people who can talk to anyone, bring a smile to people's faces, speak out against the things they hated. But my hands wouldn't move, my mouth wouldn't talk, my feet would stand still, and I was left watching as moments of my life passed without me. I simply laid in bed, staring at the ceiling, my body still unable to rise.

But in September, everything changed. I remember it clearly, the window shining brightly on my face as I looked at the textbook in front of me. It was getting to that point in the day where the words had started to jumble together. I heard laughter next to me and I tried to block it out, it always hurt my ears, like a monster's screech. “Stop it!” I heard. It was a highpitched voice paired with angelic laughter. I turned my head towards the back of the classroom, and there she was. Casually sitting with her friends, her bewitching smile was glowing. She stood out with her dark, shiny hair and tanned skin, like a ruby in a sea of pebbles. She noticed me staring and gave me a weird look as I quickly averted my attention away from her and her friends. I wiped the back of my hand over my face, feeling my cracked tan skin rough against my hollow cheeks.

I had put my headphones on, trying to block out the sound of my thoughts and the screeching laughter. I had tried to forget about what had just happened as I replayed every moment. Her smile had slightly dropped when she saw me. I remember thinking, Does that mean she doesn’t like me? I felt a tap on my shoulder and I moved to slide my headphones off my ear. “Hi!” I heard in a warm, cheerful voice. My body had stilled before I turned in my chair.

“Hey,” I replied, patting down my slightly flushed cheeks.

“I’m Alexandra, I’ve never seen you around before, are you new?” she said, trying to contain her smile.

“Uh, yeah sure” I said, scrambling for words. I still don’t know why I lied, as I’d been going to that school for five years.

“Oh um, nice! What's your name?” she replied, looking curiously into my green eyes.

“Grayson,” I replied. My hands started to clam up.

“Nice! Well I hope to see you around,” she said, turning around to go back to her seat.

I’d been at that school for five years and nobody had even tried to talk to me. I turned back and saw her laughing with her friends, all clapping their hands over their mouths to

muffle the sound of their laughter. I distinctly remembered her winking at me and her friends starting to laugh harder. I swiftly turned in my seat, completely dazed by the interaction. My cheeks were burning, and I could hear the ringing in my ears start to grow louder.

As I arrived home from school and reached my bedroom I dumped my backpack on the floor and flopped onto my bed. Completely frozen once again, my eyes burned into the ceiling. My phone dinged and I checked it to see a message from someone who had once made my stomach drop to the floor: “Hi Grayson, this is Alexandra I got your number from a friend.”

My hands were shaking as I texted back, “Hey, how are you?” My eyebrows creased as I stared at my screen.

Was it possible for one’s world to revolve around someone? I memorized her perfume, her mannerisms, her likes and dislikes. She was the only person I felt safe with, the only person at school who liked me. With that, her friends started talking to me and even some guys in our grade spoke to me for the first time in years. For a while, it felt like I was someone. Someone special, someone who was liked, someone who was good at sports and math and drawing. But it wasn’t until it was too late that I realized what was happening.

The issues started in October. “Grayson, do you have a charger?” “Grayson, can I borrow your airpods?” “Grayson, just say it! It doesn’t mean anything anyway.” “Grayson, can I copy your homework?” “Grayson, can you lie to the teacher for me?” Everything she said to me was suddenly a request, a favour that anyone would do for their friends. Except, she stopped treating me like a friend and more like a servant, one who would lie and cheat just to appease her. And suddenly her lips and smile didn’t matter anymore because all I could hear was every sentence coming from her mouth being a demand.

Suddenly, those things I had loved about her turned into feelings of hatred and all I could see was pure rage when I looked at her. Her once glossy hair looked dead and dry, her bubbly personality seemed as if a demon had stolen it from an angel. Her bright smile turned into a devilish smirk willing to get what she wanted no matter the cause. It didn’t happen in the blink of an eye, it got gradually worse. A friendship that was once flourishing started to wilt.

It was one day at school when I suddenly broke. “Grayson, give me your airpods,” I heard behind me in class, as Alexandra’s footsteps approached my seat. The rage in my fists started to build. She didn’t even ask; she just acted like the item was hers. But I calmly straightened my fingers out. I slowly blinked my eyes, starting to feel like I was in my bedroom again, frozen, letting everything go by. Until one, very unknown word came out of my mouth, “No.”

“Grayson, you're joking right? Just give them to me, I promise I’ll give them back,” she said, a small smile playing on her lips.

“No, I want to use them,” I said, determined to not stutter as I spoke. She gave me an annoyed look and went back to her seat. I watched as she told the friend sitting beside her what

I said and they both gave me annoyed looks. It took everything in me not to get my Airpods from my bag and pass it to them. I turned back in my seat, took a deep breath, and resisted thinking about it. They didn’t care about me, so why should I care about them?

But it wasn’t that one moment that changed everything. It was saying “No” over and over again that finally got her to break.

“Grayson, can I copy your work?”

“Grayson, can I have food?”

“No.”

“Grayson, can I borrow your water bottle?”

“No.”

It wasn’t just one thing that made me feel like this. It was constantly asking and asking but never giving. I had given her a gift for her birthday in November and she hugged me tightly. I felt like the luckiest guy in the world. But when it came to my birthday in March, she said, “I’m so sorry I forgot a gift, I’ll get it for you next week!” Until next week turned into next month and next month turned into summer and somehow she still hadn’t given me a gift. Even when I spent $70 dollars on her gift. That's the thing with Alexandra–she puts in just enough effort to ever stop me from wondering why she never put in more.

It never felt good leaving. It felt like icing my heart again, transporting me back to when I didn’t feel anything but uselessness. When I felt like nothing. It took me so long to realize that what I had before was more authentic and true then anything with her would have been. She treated me like a project she took under her wing, but after the project failed she simply discarded me.

She still looks at me sometimes, says hi, but knowing what I know now, I would never go back. I see her new project now, a new girl from Washington, very quiet. I see it now in other people. Laughing at the things that aren’t funny, seeming interested in things they aren’t just to appease the person they are with. I see it now, because it’s what I used to do. When Alexandra would tell a story I would laugh and laugh because I wanted to see that smile on her face. But doing that only dug a deeper hole for me to lay in as she shoveled the dirt on top of me.

I know all friendships end, but I truly thought that Alexandra and I would always be friends. It doesn’t matter if she's changed or if I want to go back to being friends. I will never cross that boundary again, or else, I might very well return to that bedroom, slowly sinking into my bed, never returning to the surface.

Allegra Ricci, The Bishop Strachan School, Grades 9 & 10

It was the day of our provincial championship on a chilly February morning. Everyone was snuggled up in their team onesies, desperately trying to stay warm, with their sparkly uniforms just underneath. As I looked around, I saw the younger kids running around like animals in the wild, clutching their stuffed animals and little toys. I saw parents grabbing their children by the hand, saying, “Say cheese!” as they posed for photos, which were definitely not the first ones they had taken that day. The smell of hairspray gave me butterflies in my stomach, a mix of excitement and nerves.

As I walked to the warm-up area, I felt an unfamiliar sensation. As I walked to the warm-up area, I felt an unfamiliar sensation. My stomach was no longer filled with butterflies, but birds. I looked around, realizing how many people were there, even though an audience had never really bothered me. I brushed it off, hoping it would go away on its own. I started to do my stretches, holding each for a few extra seconds to make sure I was properly stretched. I could hear the loud music coming from the stage that was just on the other side of the wall, knowing it would be my turn soon.

Coach gathered us in a tight circle, his voice scratchy from screaming all day.

“Remember, you guys have got this. We’ve done this routine hundreds of times in the gym, and performing it here is no different. This is practice for nationals, so do your best. Trust yourselves and remember to breathe.”

His words made me feel something like they were hitting close to home. My teammates and I often joked about how he sounded like he was giving us a TED Talk or a lecture, but this time I didn’t participate in the jokes. Why did he think we needed reassurance?

“I’m so excited,” my best friend, Abby, said, “I heard the medals are really big!”

The birds became hawks, why wasI the only nervous person? As we walked toward the stage, I felt sick—not like I had the flu, but as if everything I had ever eaten was about to come back up. I felt dizzy, and the noise of the excited crowd was overwhelming; it sounded both loud and quiet as if it were coming from another universe. My heart felt like it was about to explode from my chest, pounding so hard that I almost couldn’t hear Abby ask, “Are you okay? Do you want some of my water?” A moment went by, I still couldn’t hear her. “Legs! Do you want me to get coach?”

“No. I’m fine.”

Truth is, I wasn’t. I was feeling a feeling I had never felt before. When I heard the announcer call out that our team was on deck, I felt even worse. I was overwhelmed with adrenaline, my heart racing, and my hands sweating and shaking.

Once it was our turn, I was supposed to go on stage. However, the usual excitement of running out onto the stage had gone. I stepped back deeper into the backstage area, feeling overwhelmed and out of control. I felt the tears dripping down my face and onto my uniform. I watched as the music started, my team frantically looking around trying to find me. I stumbled around, trying to find a wall to lean on. Suddenly, I felt someone grab my shoulders. At first, I was startled; it couldn’t be a teammate, since they were on stage, and it definitely wasn’t coach, because he was watching my team perform. The person pulled me closer, wrapping one arm around me in a tight, comforting hug while the other hand gently wiped away my tears.

We hugged in silence until I was able to catch my breath. I looked up and realized it was Skylar, one of the main tumblers on the international team. I immediately attempt to wipe away my tears. She couldn’t see me like this. She was Skylar, one of the best athletes in all of Canada, if not the whole world. Stop crying, Allegra. Stop! This was so embarrassing. She was going to think I was a crybaby.

She noticed that I was trying to wipe away my tears, “Hey, it’s okay. You’re alright. I’m right here.” She hugged me tighter and continued, “I’ve been exactly where you are right now. I know it feels like everything is going wrong. Like you can’t breathe and everything is out of control, but I promise you, it’s going to be okay.” She leaned in, our eyes meeting, “Don’t worry about the routine, or the people, or doing all your tumbling. Just focus on taking one breath at a time, slowly. You're not here to be perfect, you're here to have fun because this is the sport you love!”