5 minute read

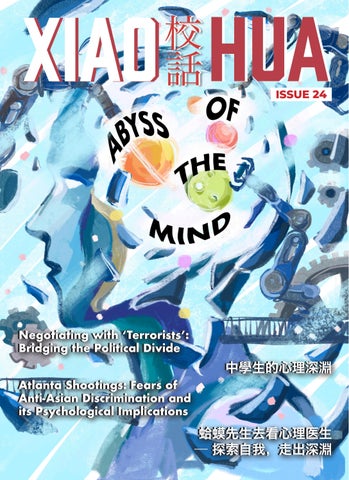

Atlanta Shootings: Fears of Anti-Asian Discrimination and its Psychological Implications

from Xiao Hua Issue 24

by Xiao Hua

Atlanta Shootings: Fears of Anti-Asian Discrimination and its Psychological Implications By Michelle Liu | Illustration by Isabella Zee | Layout by Zoe Zheng 摘要:新冠病毒蔓延至今令全球變得愈加分化,暴力似乎無處不見。2021年3月16日的美國亞特蘭 大槍擊案引起了社會對亞裔人遭受暴力與歧視對待的關注。本篇文章深入分析了暴力歧視對亞裔人 身心健康的深刻影響以及舒緩此問題的一些方法。

On March 16th, 2021, six Asian women were killed in a series of mass shootings in Atlanta, Georgia. The incident sparked outrage both locally and internationally, and gave rise to a series of protests against anti-Asian violence across the States. While the pandemic is far from the first time Asian-Americans and Pacific Islanders (AAPI) have been the target of hate crimes and discrimination in the U.S., it has amplified the problem as Asians are associated with the spread of the virus, as well as subjected to stereotypes and prejudice. Not only do these acts of discrimination threaten individuals physically, they can also have unparalleled mental health effeects which are much harder, but just as important to address in the long-term.

Advertisement

The start of anti-Asian sentiments in the U.S. can partly be attributed to the ‘Chinese Exclusion Act’, a federal law signed in 1882 to restrict the number of Chinese immigrants in America. In the late 19th century, Chinese immigrants in the West Coast were often stereotyped as “degraded” and “uncivilised”, leading to the development of a collective anti-Chinese mindset within the country. Eventually, the term “yellow peril” was coined as the Chinese were considered a threat to Western values and public health. While the Exclusion Act ended in 1965, these stereotypes still persist in society. One-third of AAPIs reported experiencing discrimination before the pandemic even began. Additionally, the “model minority” myth – the belief that all AsianAmericans are successful, welleducated, and tolerant of racism –is extremely detrimental as the hardships and discrimination that Asians face are overlooked by the media and general public. In fact, despite the assumptions surrounding upward mobility, Asian Americans are actually the poorest group in New York city with 25% of the population living in poverty. They are also the most affected by unemployment during the pandemic – demonstrating that the model minority stereotype is indeed just a myth.

These issues have been magnified during the pandemic as those of Chinese descent all around the world are accused of spreading the virus. The use of the terms “China virus” and “Kung flu” by President Trump and the media, echoing the decadeold “yellow peril” rhetoric, gave rise once again to blatant xenophobia and unfounded hate plaguing the Asian community. According to Stop AAPI Hate, an anti-discrimination organisation, roughly 3,800 antiAsian hate incidents were reported just a year into the pandemic, with women and elders being the most affected. The persistence of negative stereotypes and surge in hate crimes could partly be explained by the need for an outlet in the face of unparalleled uncertainties and adversities – people are ready and willing to blame anything that can provide an explanation for their own misfortunes.

With the steady rise of discriminatory acts, it is no surprise that the mental wellbeing of Asians and AsianAmericans are also in steep decline. While fear, anxiety and depression are common emotions in the midst of a global health crisis, studies have found that Asian communities are disproportionately affected in terms of mental health. A study published in Ethnic and Racial Studies found that Asian immigrants and Asian Americans experienced significantly higher levels of mental disorders during the pandemic, and that this phenomenon can partially be attributed to discrimination. Additionally, other studies have shown that racial trauma caused by discrimination can lead to the development of chronic mental health issues, including anxiety, depression, and somatic disorders related to eating and sleeping. Asians have been at high risk of mental illnesses even before the pandemic began; while they had some of the highest rates of depression and suicide, they were also the least likely to seek mental health services. Now, Asians (international students in particular) must deal with both concern for themselves and their families in the midst of Covid-19, and isolation and stigmatization, substantially increasing the risk factors of mental disorders. Thus, contrary to what the model minority myth suggests, Asians are, and have long been, one of the most vulnerable social groups in our society.

In addition to low utilisation of mental health services, Asians were also found to be reluctant to report hate crimes. Most reflect that they found doing so too troubling or intimidating, which is another concern as it can prevent them from accessing the appropriate resources and receiving the help and attention that they need. The model minority myth perpetuates this problem as the image of Asians as being free of any social problems restrains Asians themselves from actively demonstrating their need for help, resulting in the internalisation of To counter this issue, there are a number of actions to be taken at both the community and institutional level. A paper published on ‘Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy’ suggested actively challenging stereotypes of Asian communities present in the media by presenting them as “unrepresentative” or “atypical”. Additionally, public figures can use their social influence to spread a positive message to a wider audience, such as the First Lady of New York who shared a video on Twitter voicing solidarity with Asian Americans. Government leaders can also play a crucial role in terms of policies and support services that they offer to the affected communities. For instance, due to the low number of Asians seeking mental support, “culturally-appropriate mental health services” and “community-based outreach” could be useful measures in order to encourage more to seek help. Previously, the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) implemented a anti-discrimination initiative during the SARS pandemic to monitor stigmatisation and work with Asian American communities to develop culture-specific interventions, a proven example of a potentially effective response.

On a micro level, there are many resources online which provide opportunities to learn more, donate and keep up with new developments surrounding the AAPI community, one of them being the ‘Anti-Asian Violence Resources’ Carrd page. Additionally, reporting any incidents to organisations like Stop AAPI Hate or Stand Against Hatred so that the data can be used for spreading awareness and developing further preventative Ultimately, if nothing else can be done, simply checking in on a friend or family member overseas or at risk can also have just as big of an impact.

Anti-asian discrimination has long been present in the u.S., As well as other parts of the world, and it is likely to continue beyond the pandemic. The chasm that such discrimination can create between people is striking, and bridging it will undoubtedly take much time and effort. However, it can be done – every individual should work towards promoting inclusivity, diversity and racial acceptance, so that this yawning abyss that we see at the moment might someday be reduced to the smallest crevice.