Was Joe Johnston honest with History? Cassville The Herb Peck Photography Collection The Enfield at Manassas Battles—and Their Impact on Families Vision and Valor: The War Through Women’s Eyes Fresh Views of the War’s Most Famous Fort Civil War NEWS $7.99 The Truth At VOL. 50, NO. 5 | MAY-JUNE 2024

Exchange Park Fairgrounds 9850 Highway 78 Ladson, SC 29456

June 1 & 2, 2024 Charleston Gun & Knife Show

July 27 & 28, 2024 Asheville Gun & Knife Show

WNC Ag Center 1301 Fanning Bridge Road

NC 28732

Charleston Gun & Knife Show

Exchange Park Fairgrounds 9850 Highway 78 Ladson, SC 29456

Sept. 7 & 8, 2024

Ag Center

5 & 6, 2024

& 13, 2024

Promoters of Quality Shows for Shooters, Collectors, Civil War and Militaria Enthusiasts Military Collectible & Gun & Knife Shows Presents The Finest Rev War Civil War World War I & II Modern Gun & Knife Shows Mike Kent and Associates, LLC • PO Box 685 • Monroe, GA 30655 (770) 630-7296 • Mike@MKShows.com • www.MKShows.com Williamson County Ag Expo Park 4215 Long Lane Franklin, TN 37064 Dec. 7

8, 2024 Middle TN (Franklin) Civil War Show

&

l l l l Myrtle Beach Convention Center 2101 North Oak Street Myrtle Beach, SC Oct. 12

Myrtle

Gun & Knife Show

Beach

WNC

1301 Fanning Bridge

Fletcher, NC Oct.

Asheville

Knife Show

Road

Gun &

Fletcher,

This is Hallowed Ground.

When you visit battlefields of the Revolutionary War, the War of 1812 and the Civil War, you are standing where history happened.

With the help of our supporters and partners, the American Battlefield Trust has saved more than 58,000 acres at 155 sites in 25 states, creating outdoor classrooms where the past can come alive.

history

1 Civil War News Magazine | May-June 2024 Join us and help protect America’s past by saving endangered battlefields. www.battlefields.org Gettysburg National Mililtary Park, Gettysburg, Pa. PATRICIA RICH

Get preservation news,

and more right to your email!

Keep in touch!

www.battlefields.org/email-signup

Published by Historical Publications LLC

2800 Scenic Drive, Suite 4-304, Blue Ridge, GA 30513 800-777-1862 • Facebook.com/CivilWarNews

mail@civilwarnews.com • civilwarnews.com

Advertising: 800-777-1862 • ads@civilwarnews.com

Publisher

Jack W. Melton Jr.

Editor

Lawrence E. Babits, Ph.D.

Columnists

Advertising, Marketing and Assistant Editor

Peggy Melton

Graphic Designer

Macey R. Hurst

Craig Barry, Salvatore Cilella, Stephen Davis, Ph.D., Stephanie Hagiwara, Gould Hagler, Chris Mackowski, Ph.D.–Emerging Civil War, Colleen Cheslak-Poulton–American Battlefield Trust, Tim Talbott–Central Virginia Battlefield Trust

Contributors and Photography Staff

Curt Fields, Ph.D., Jeff T. Giambrone, Robert Jenkins Sr., Michael Kent, Jonathan Noyalas, Shannon Pritchard, Richard H. Holloway, Harold Holzer, Leon Reed, Douglas D. Scott, Ph.D.,Jonathan White, Bob Zeller–Civil War Center for Photography

Consultants

Lawrence Babits, Ph.D., Craig L. Barry, Craig D. Bell, J.D., LLM in Tax, Jack Bell, Greg Biggs, Salvatore Cilella, Stephen Davis Ph.D., Gould Hagler, Richard H. Holloway, Harold Holzer, Robert Jenkins Sr., Juanita Leisch Jensen, Gordon L. Jones, Ph.D., Mike Kent, Lewis Leigh Jr., Tom Liljenquist, Chris Mackowski, Ph.D., Jonathan Noyalas, Tim Prince, Tom Rowe, Ted Savas, Philip Schreier, Greg Ton, Jonathan White, Charles Williams, Melissa Winn, Bob Zeller

Terms and Conditions: The following terms and conditions shall be incorporated by reference into all placement and order for placement of any advertisements in Civil War News by Advertiser and any Agency acting on Advertiser’s behalf. By submitting an order for placement of an advertisement and/or by placing an advertisement, Advertiser and Agency, and each of them, agree to be bound by all of the following terms and conditions: All advertisements and articles are subject to acceptance by Publisher who has the right to refuse any ad submitted for any reason. Mailed articles and photos will not be returned. The advertiser and/or their agency warrant that they have permission and rights to anything contained within the advertisement as to copyrights, trademarks or registrations. Any infringement will be the responsibility of the advertiser or their agency and the advertiser will hold harmless the Publisher for any claims or damages from publishing their advertisement. This includes all attorney fees and

judgments. The Publisher will not be held responsible for incorrect placement of the advertisement and will not be responsible for any loss of income or potential profit lost. All orders to place advertisements in the publication are subject to the rate card charges, space units and specifications then in effect, all of which are subject to change and shall be made a part of these terms and conditions. Photographs or images sent for publication must be high resolution, unedited and full size. Phone photographs are discouraged. Do not send paper print photos for articles. At the discretion of Civil War News any and all articles will be edited for accuracy, clarity, grammar, and punctuation per our style guide. Articles can be emailed as a Word Doc attachment or emailed in the body of the message. Microsoft Word format is preferred. Email articles and photographs: mail@civilwarnews.com. Please Note: Articles and photographs mailed to Civil War News will not be returned unless a return envelope with postage is included.

CivilWarNews.com

VOL. 50, NO. 5 | MAY-JUNE 2024

Civil War News (ISSN: 1053-1181) Copyright © 2024 by Historical Publications LLC is published 6 times per year by Historical Publications LLC, 2800 Scenic Drive, Suite 4-304, Blue Ridge, GA 30513. Bi-monthly. Business and Editorial Offices: 2800 Scenic Drive, Suite 4-304, Blue Ridge, GA 30513, Accounting and Circulation Offices: Historical Publications LLC, 2800 Scenic Drive, Suite 4-304, Blue Ridge, GA 30513. Call 800-777-1862 to subscribe. Periodicals postage paid at U.S.P.S. 131 W. High St., Jefferson City, MO 65101.

POSTMASTER: Send address changes to:

Historical Publications LLC 2800 Scenic Drive Suite 4-304 Blue Ridge, GA 30513

Advertising

Advertising rates and media kit email ads@civilwarnews.com.

The Civil War News is for your reading enjoyment. The views and opinions expressed herein are those of its authors, readers and advertisers and they do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Historical Publications, LLC, its owners, contributors, and/ or contractors/employees.

Publishers

Please send your book(s) for review to: Civil War News

2800 Scenic Drive Suite 4-304 Blue Ridge, GA 30513

Books for Review

Letters to the Editor

Email mail@civilwarnews.com

Email book cover image to bookreviews@civilwarnews.com. Civil War News cannot assure that unsolicited books will be assigned for review. Email bookreviews@ civilwarnews.com for eligibility before mailing.

By Jonathan A. Noyalas

Zeller, President,

Holloway

By Jonathan A. Noyalas

Zeller, President,

Holloway

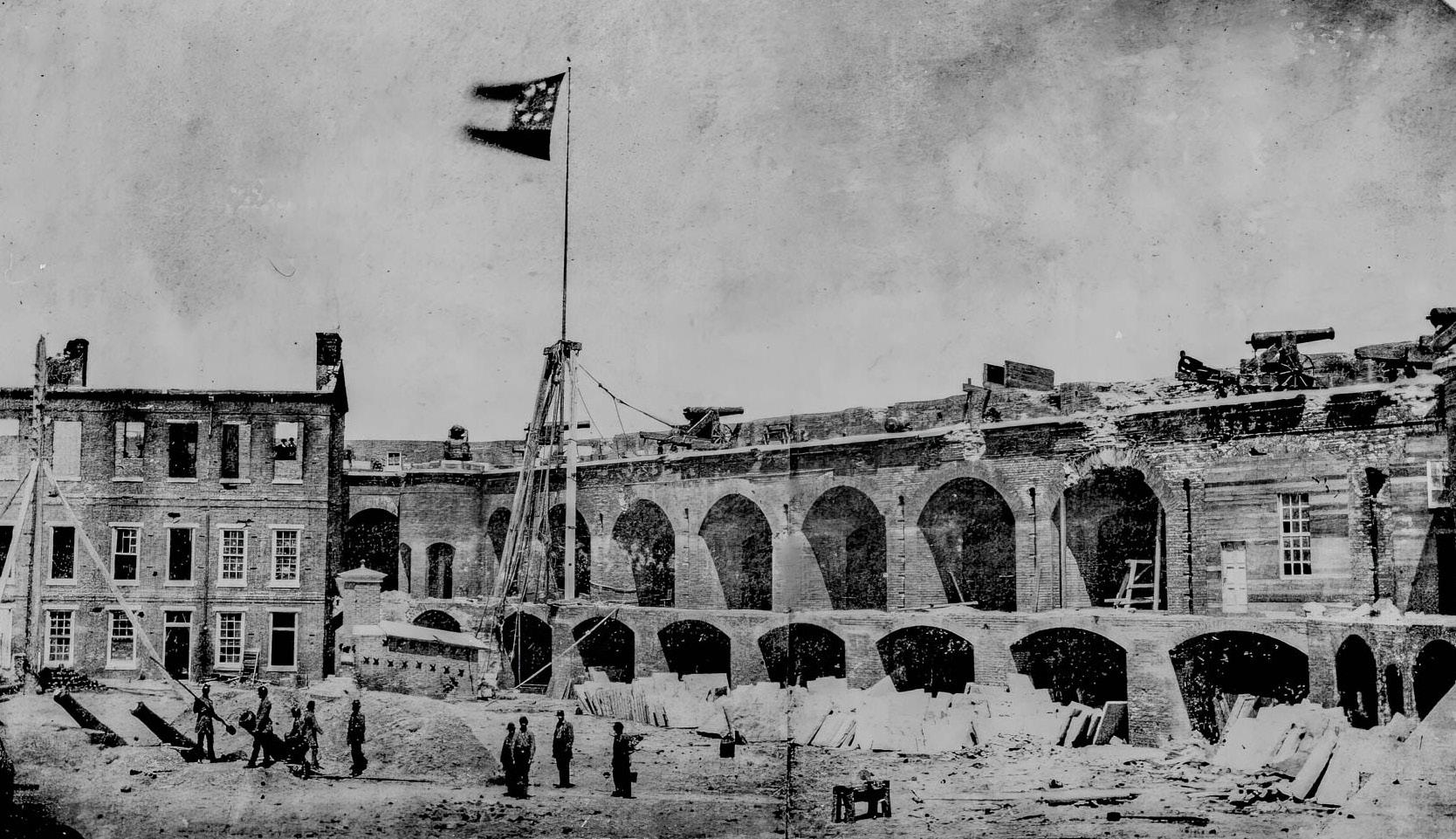

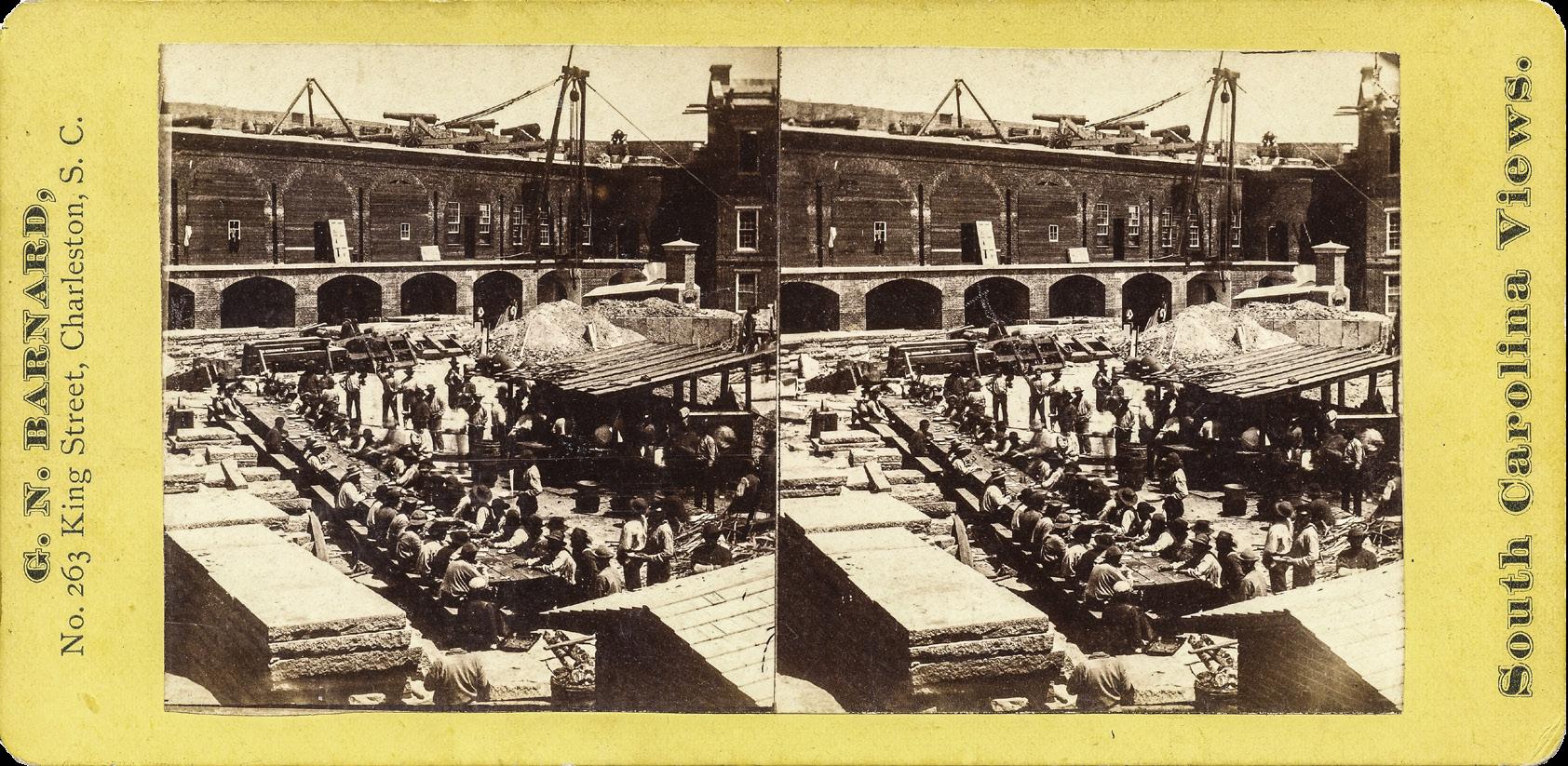

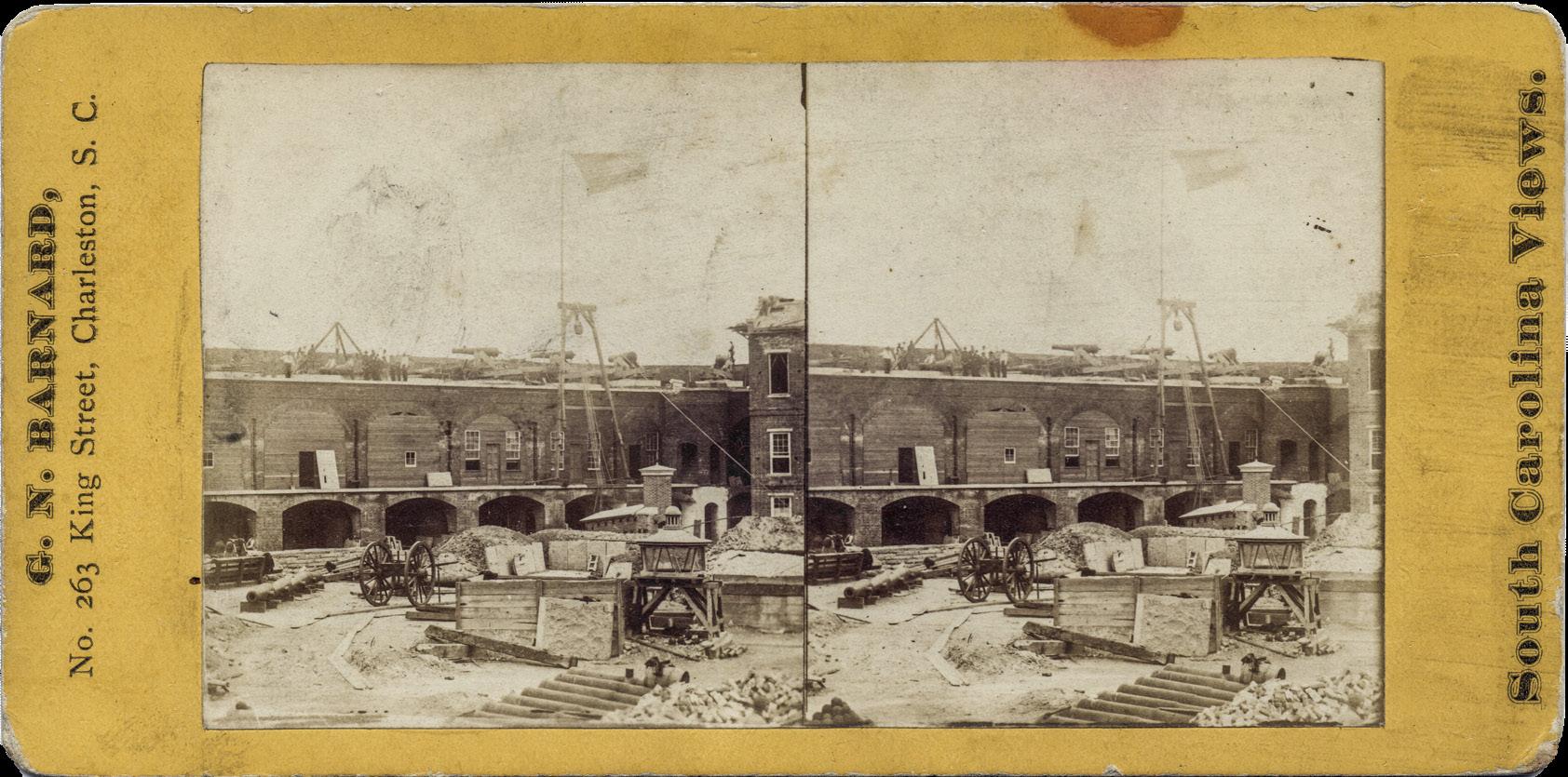

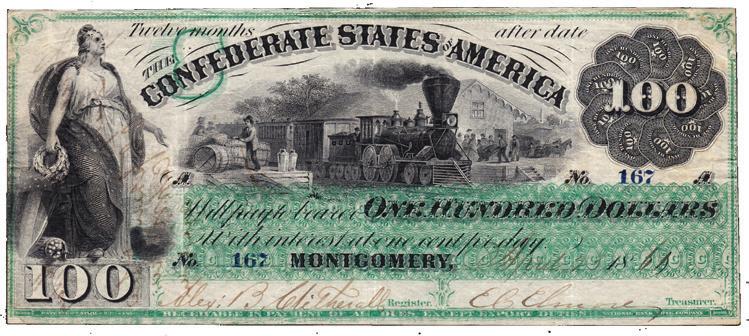

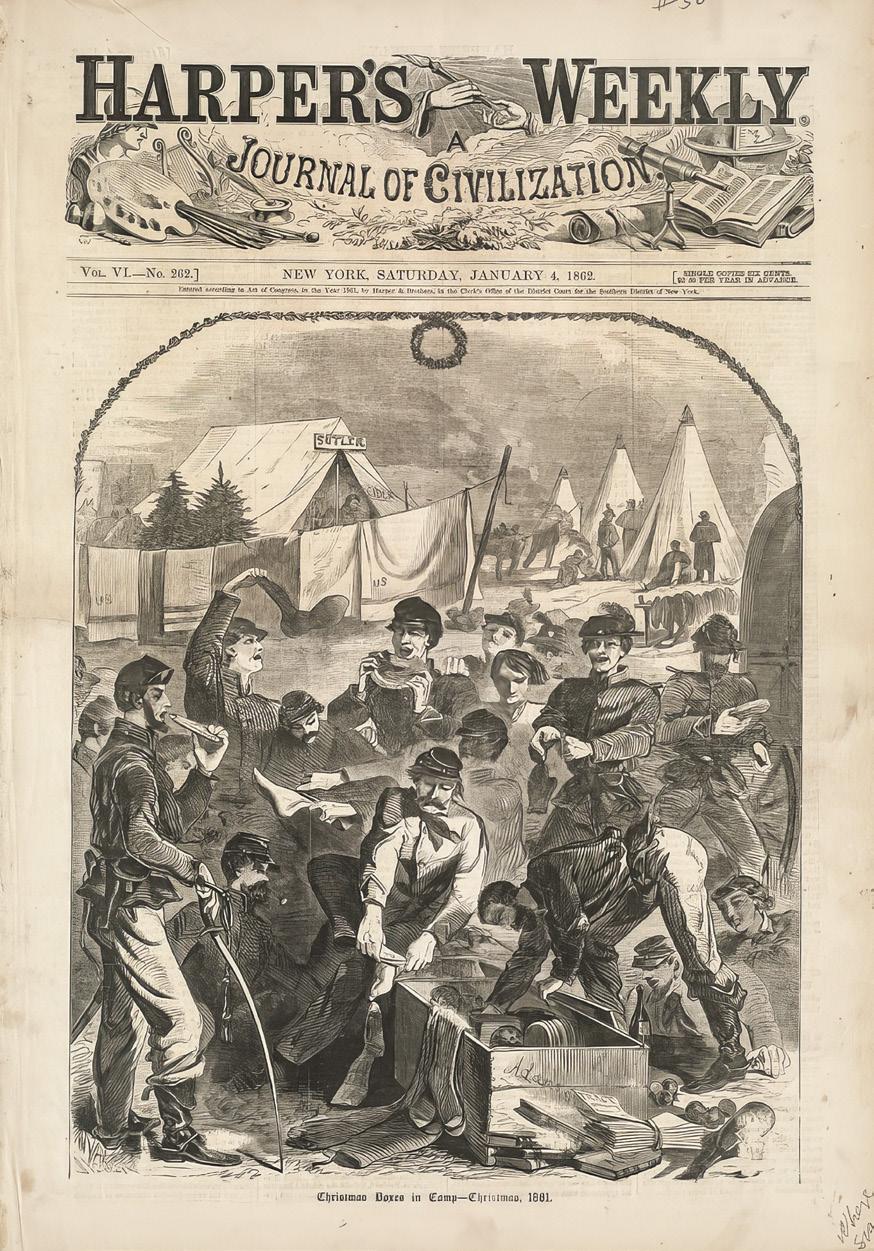

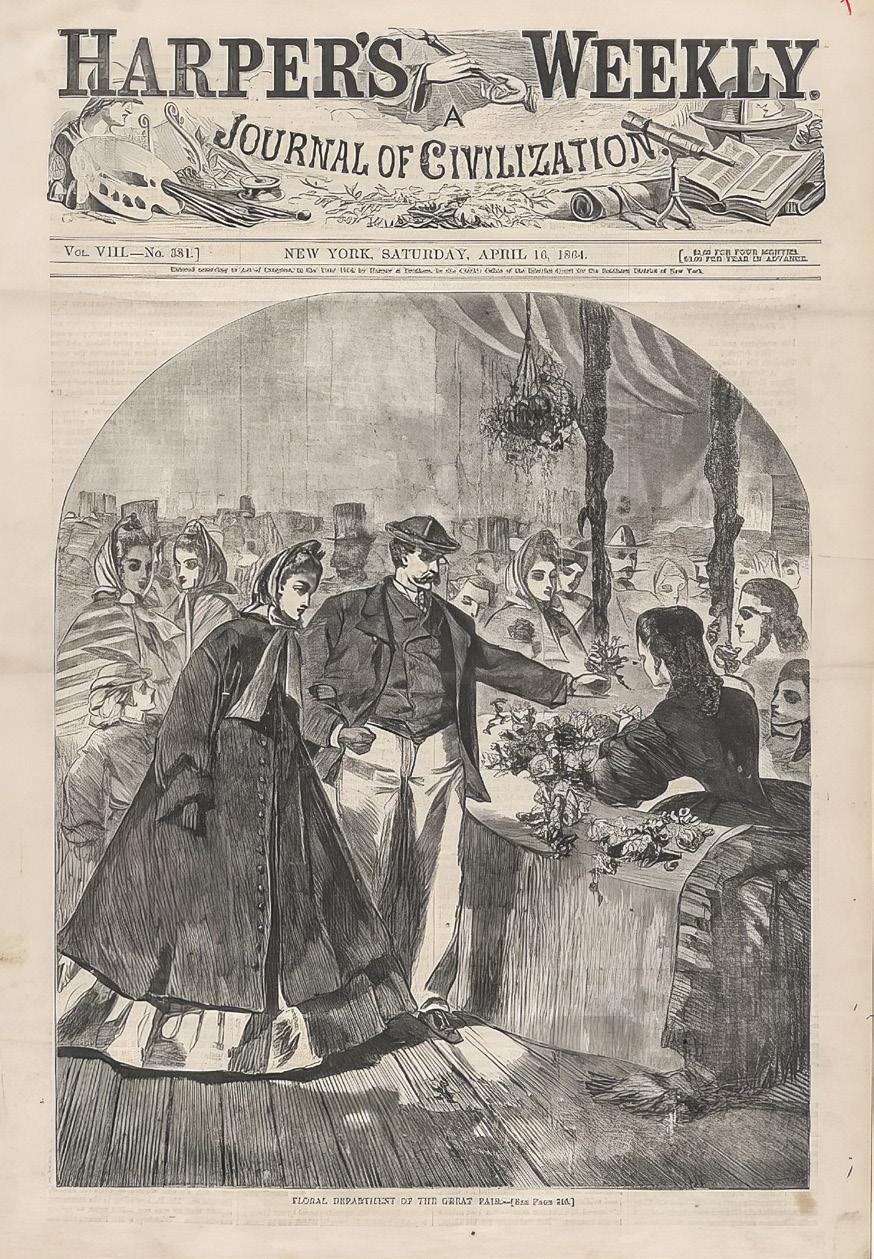

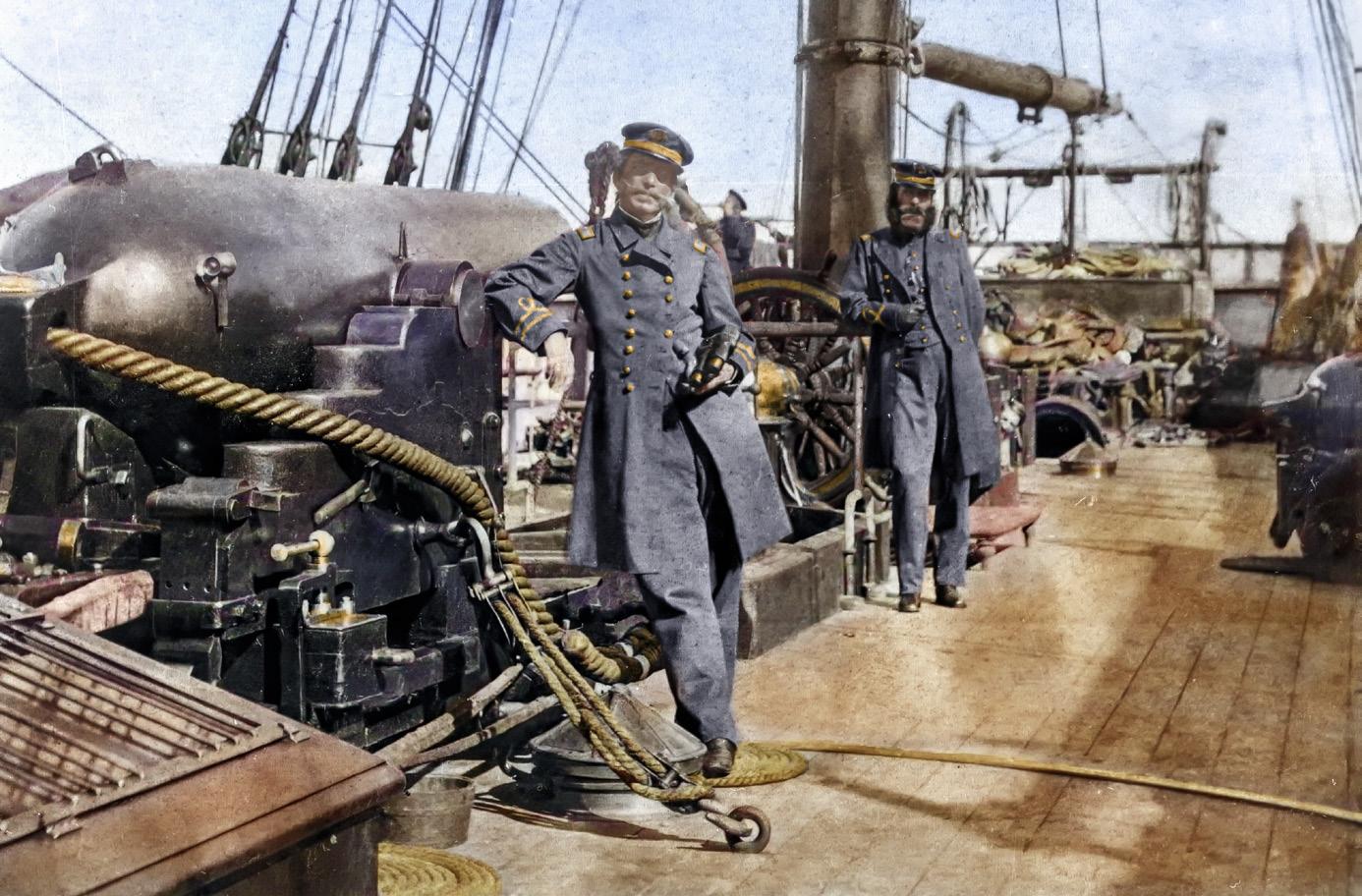

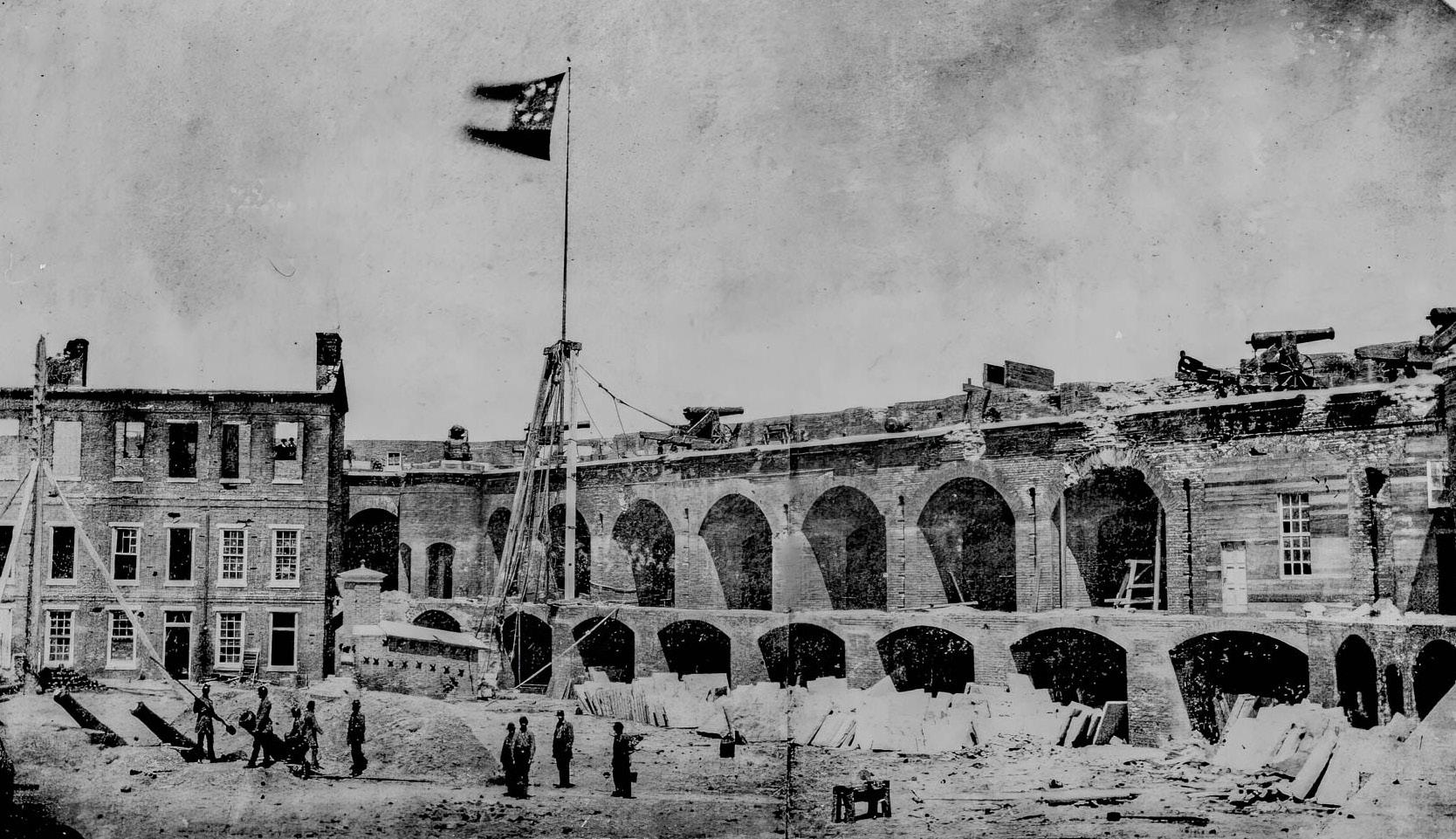

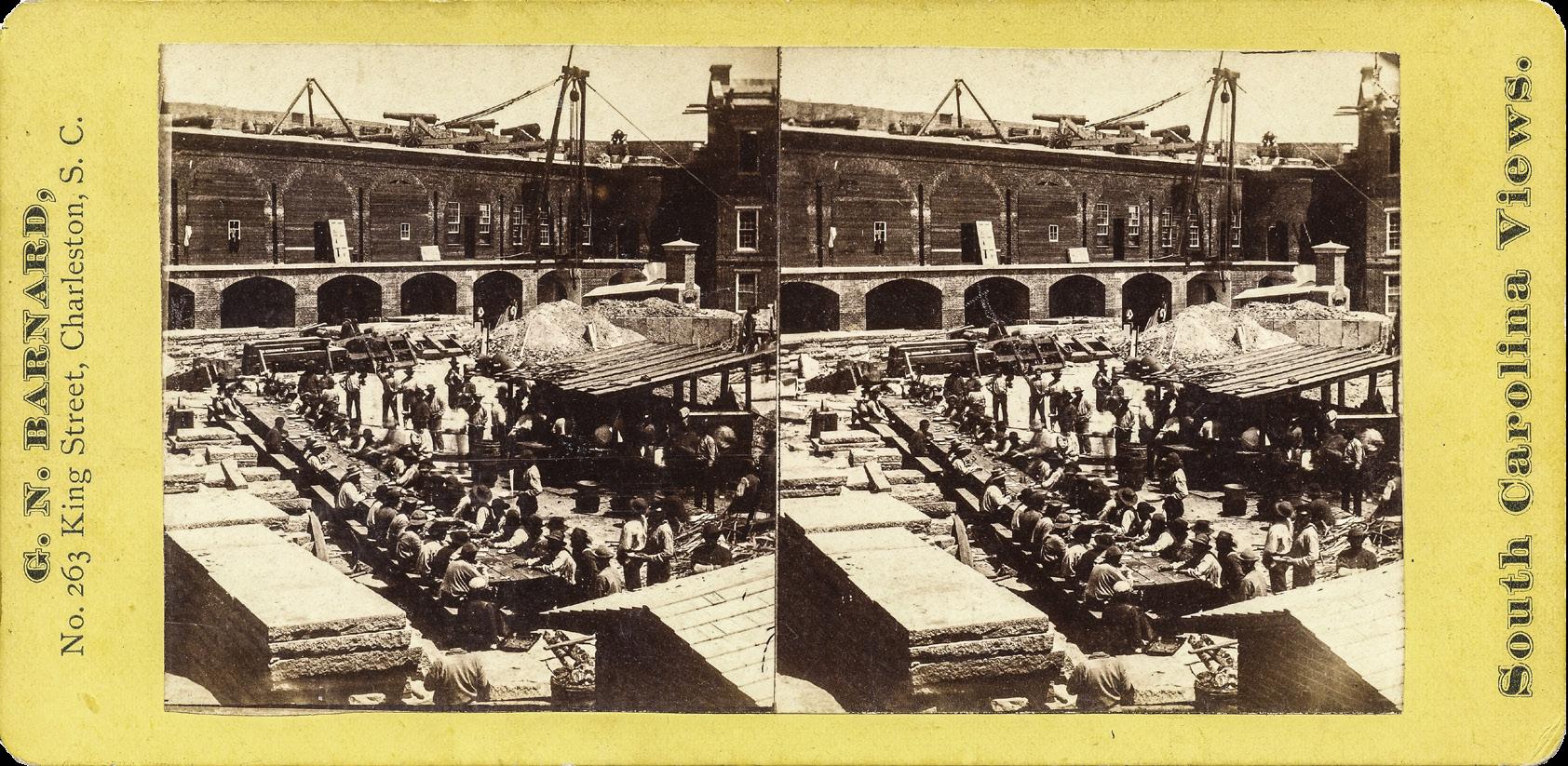

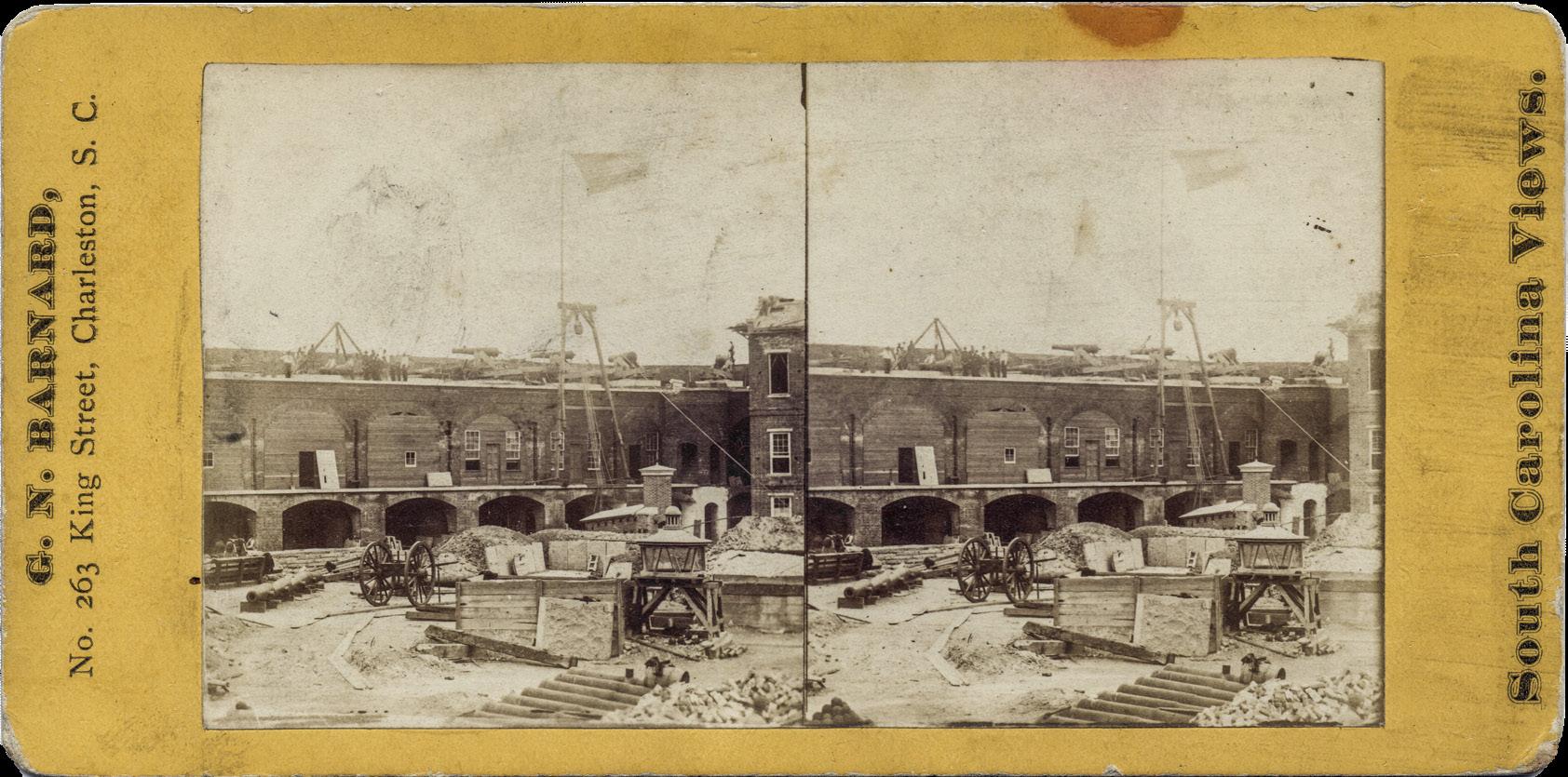

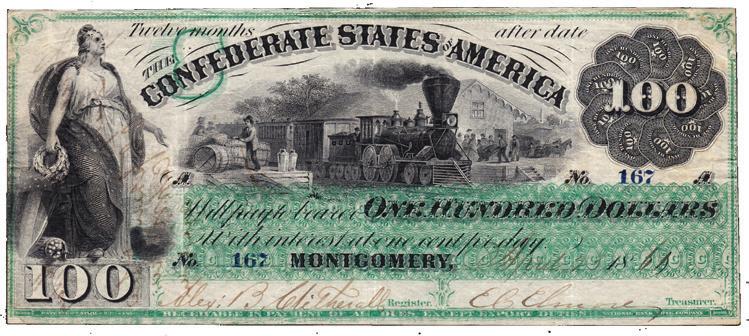

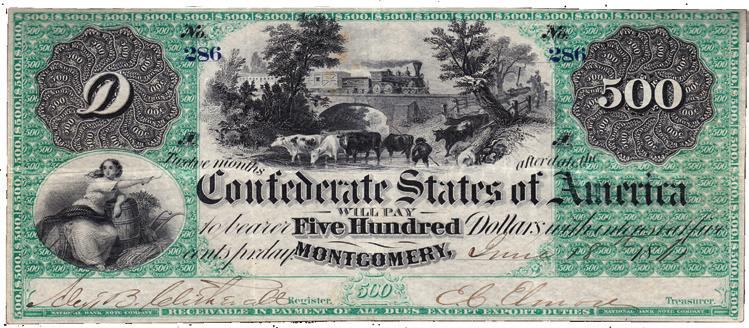

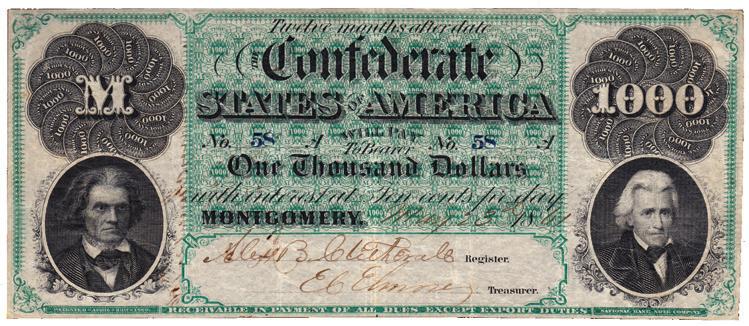

Fresh Views of the War’s Most Famous Fort Rare Views of Fort Sumter. By Bob

The Center for Civil War Photography 48 Maryland Arms Collectors Show The 68th Annual Show News from Timonium, MD. 52 Herb Peck Jr. Civil War Photography Collection The Story of a Civil War Photography Collector and the Sale of His Recovered Images. By Richard H.

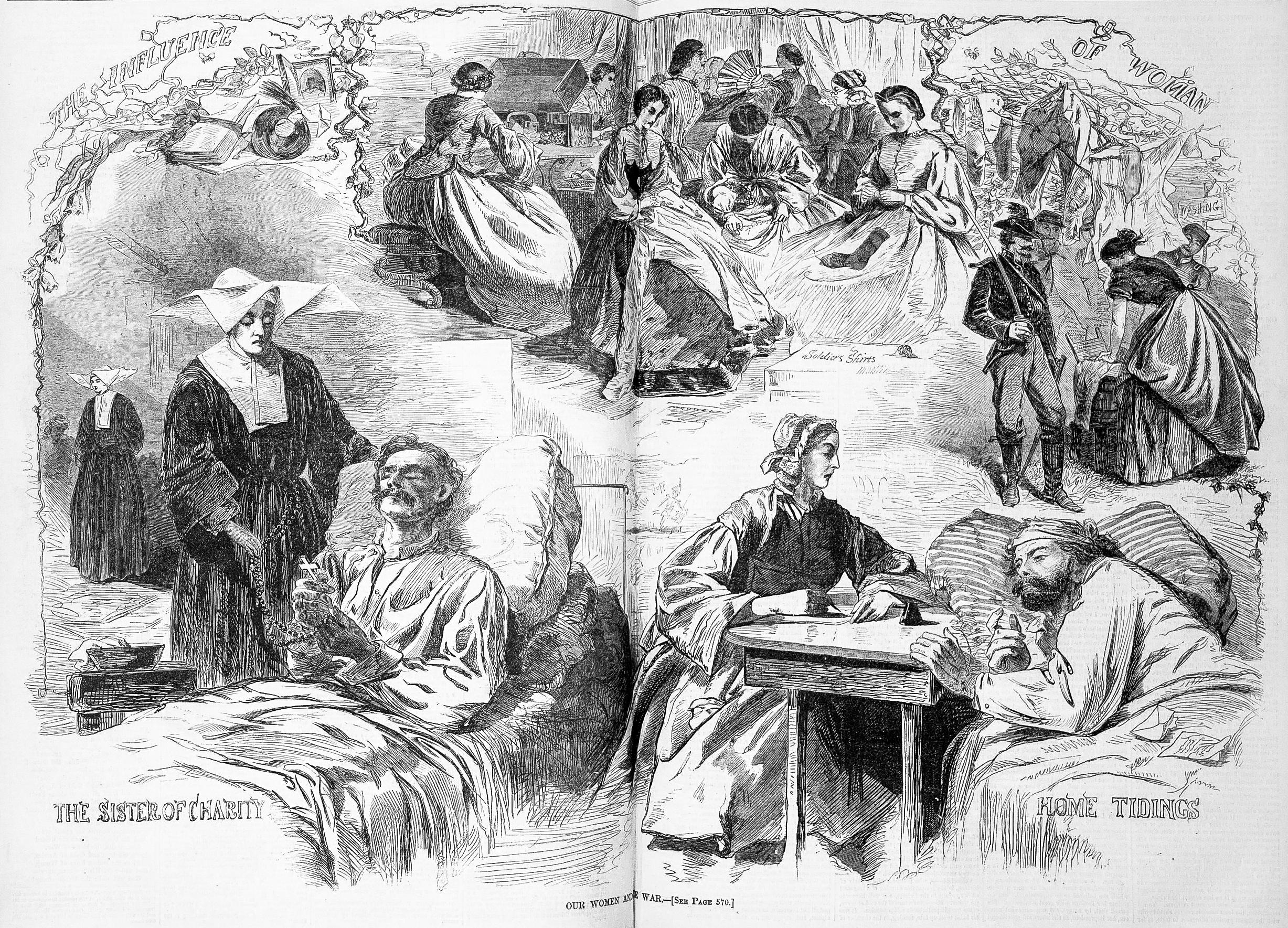

70 How Shall All These Would be Healed? 18 56 Was Joe Johnston honest with History? the truth at cassvile IN THIS ISSUE This article promises to change the perception and understanding of Cassville, its mysteries, and its principal leaders. Exploring Battle’s Impact on Families.

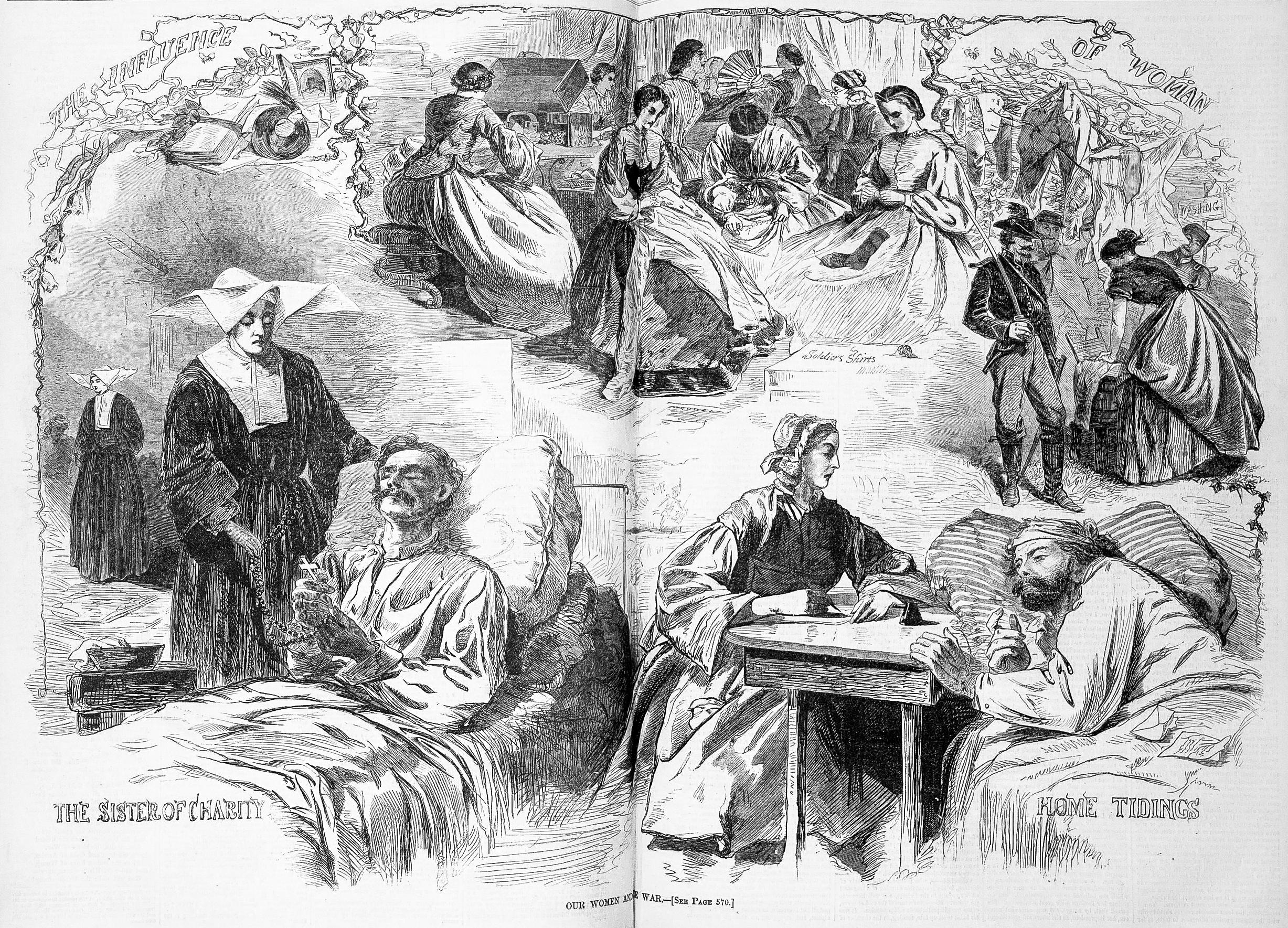

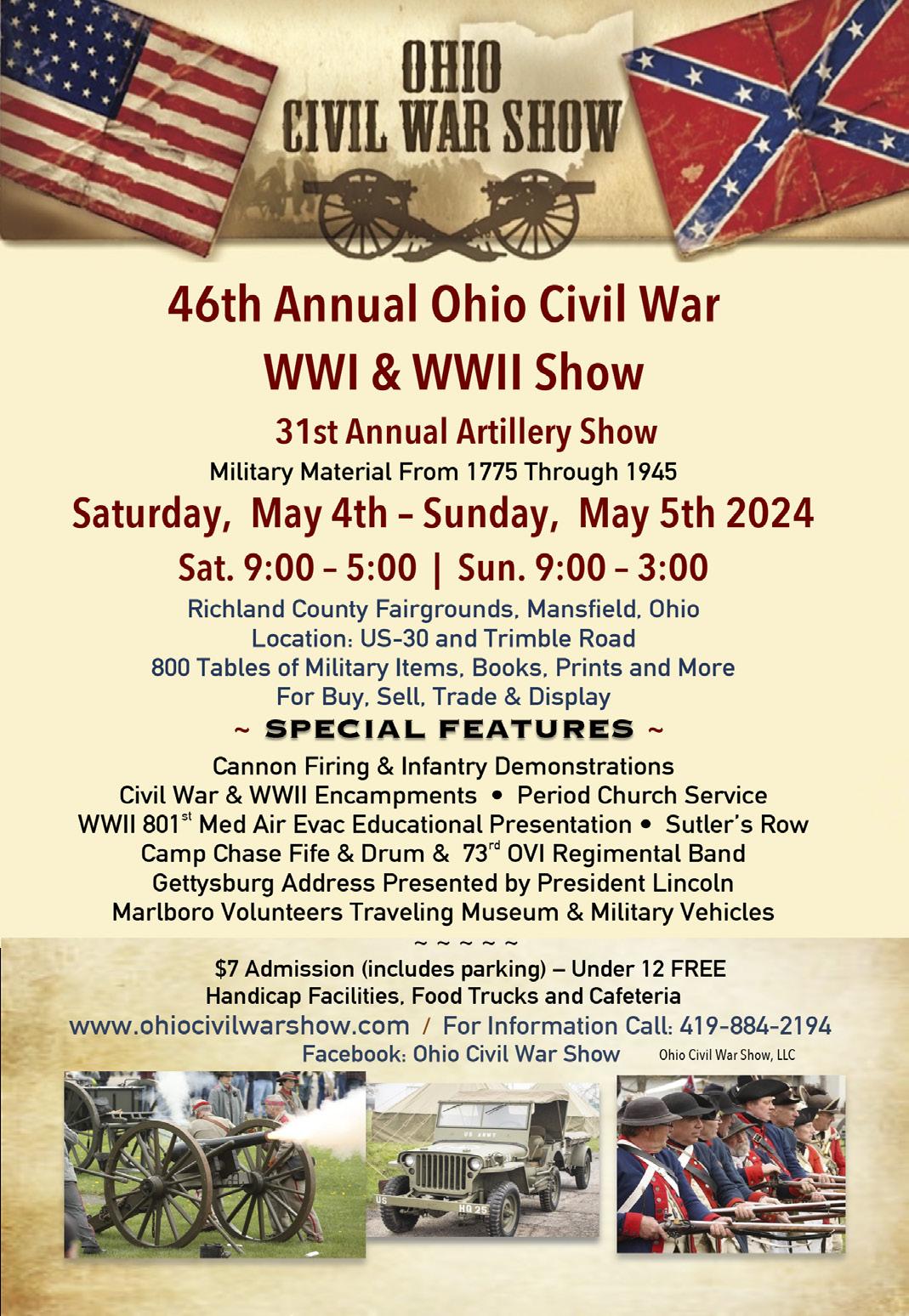

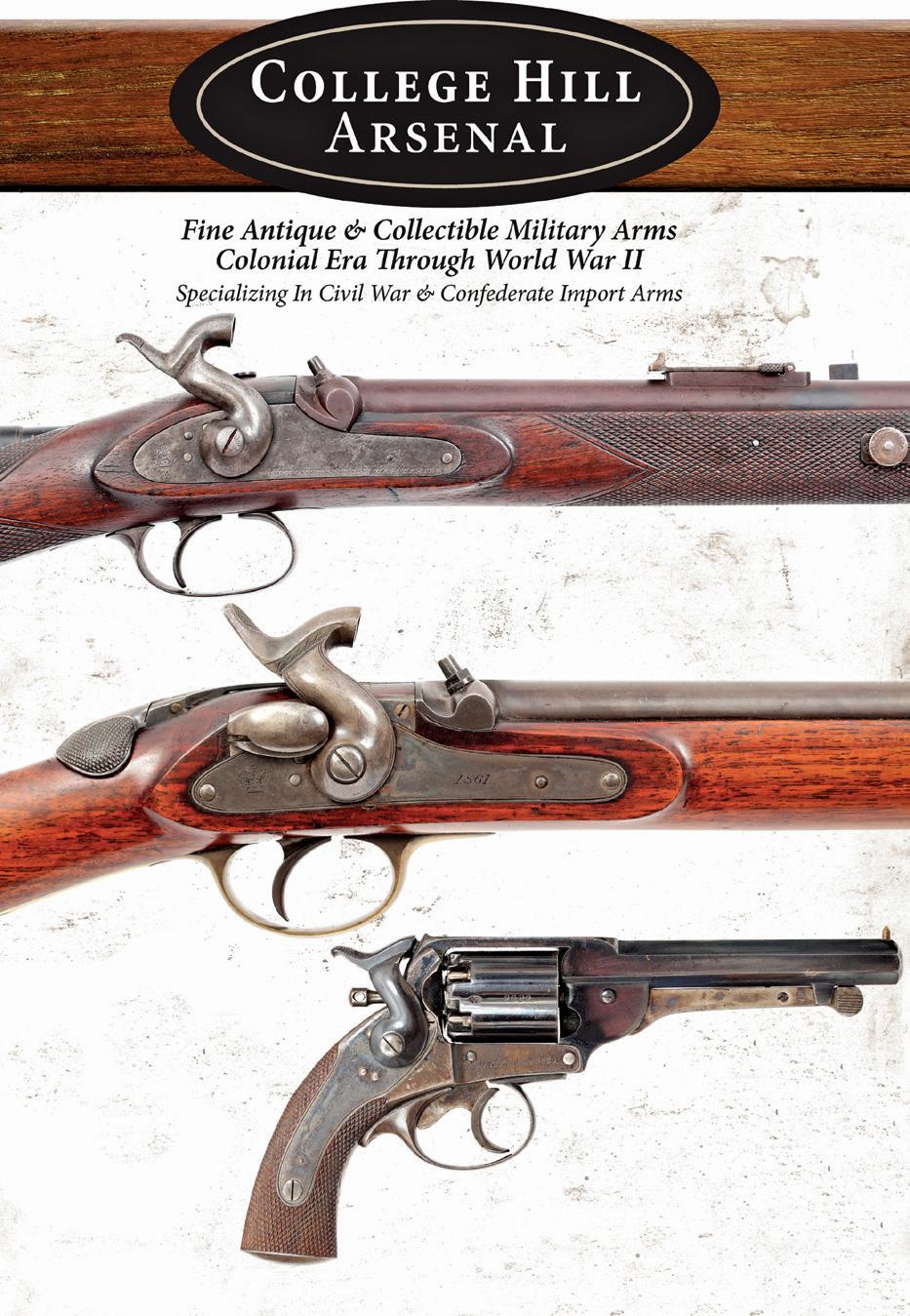

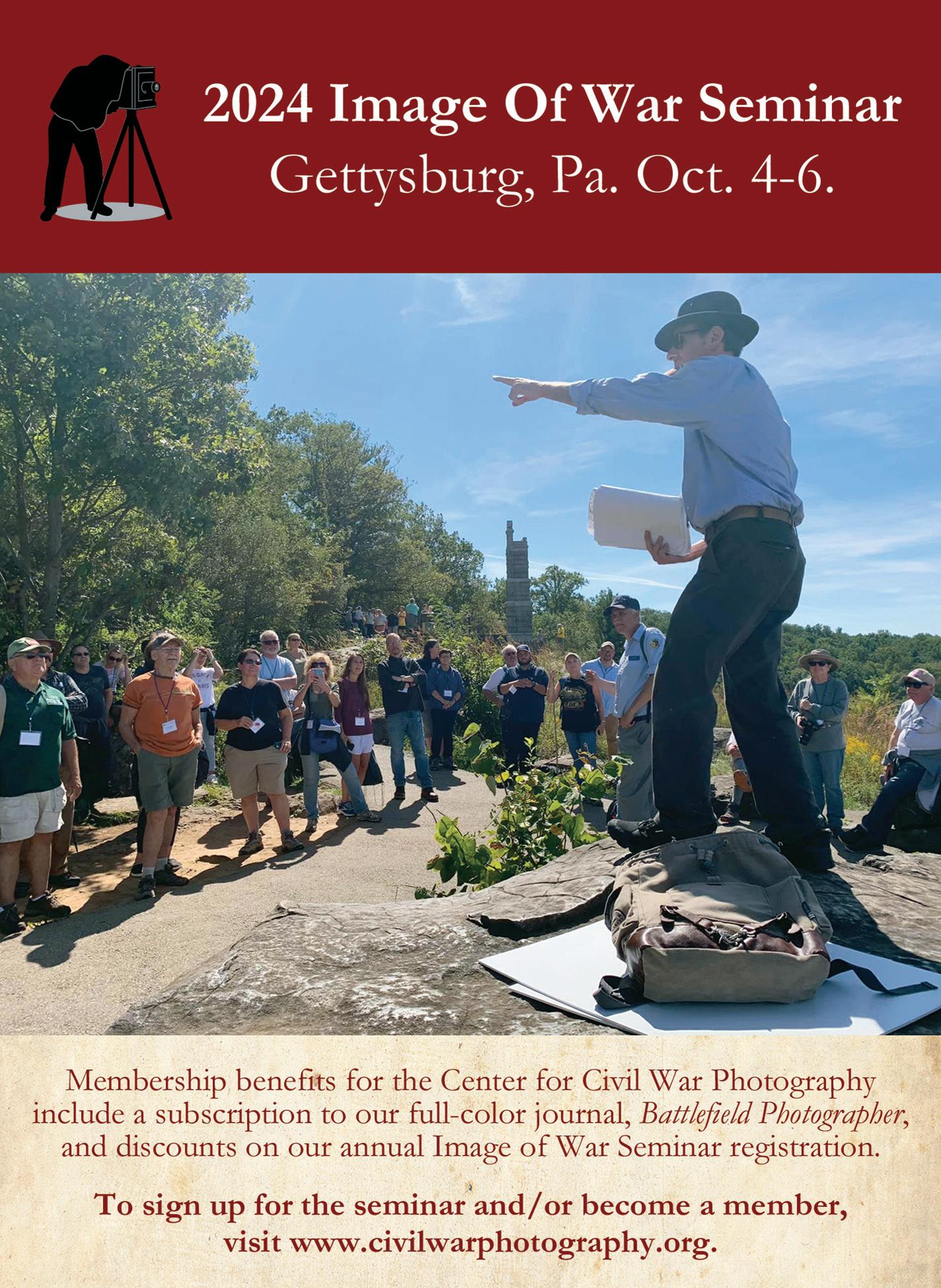

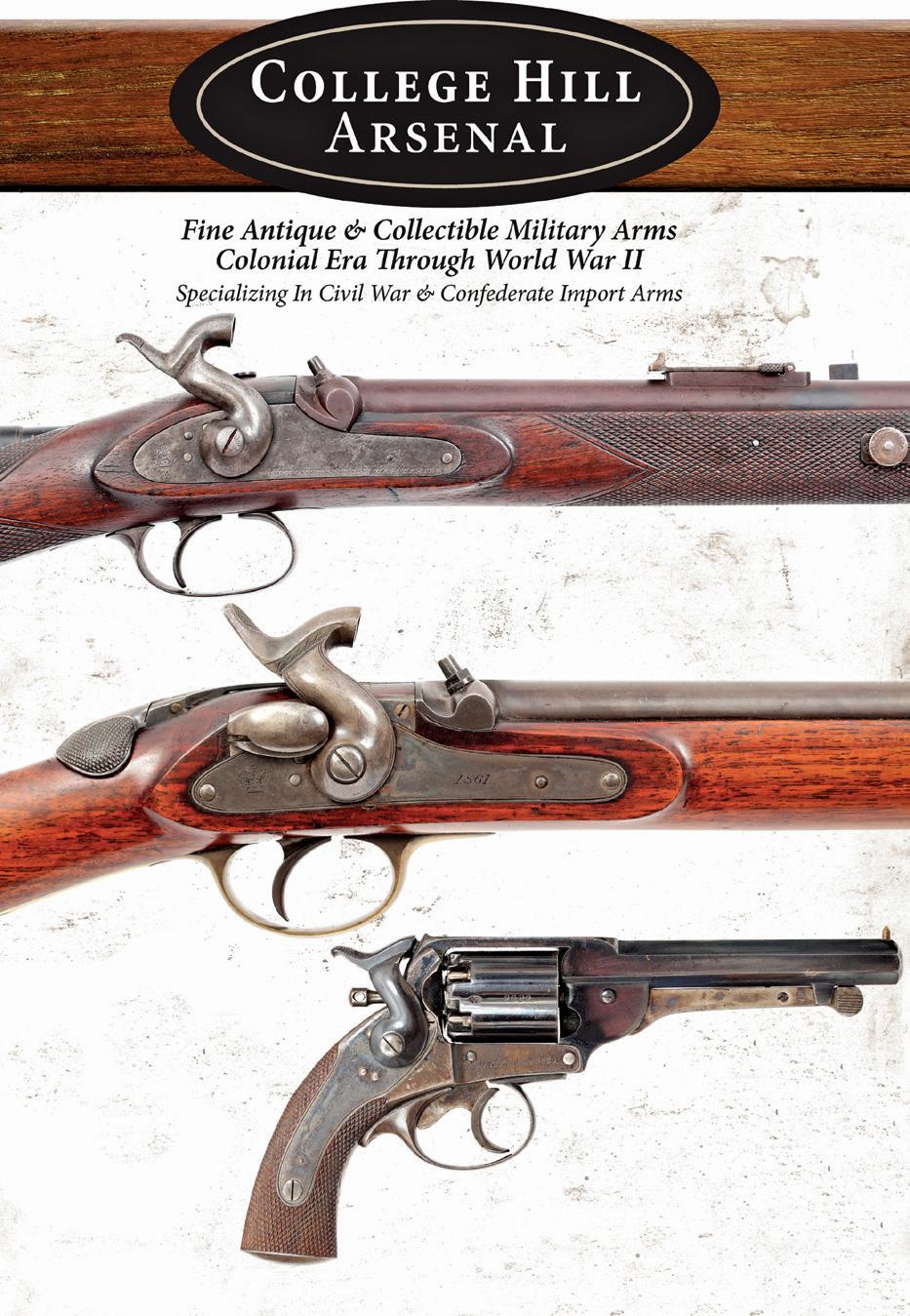

advertisers critic’s corner William Andrew Fletcher, Rebel Private Front and Rear (1908). By Stephen Davis Ace Pyro LLC 46 American Battlefield Trust 1 American Digger Magazine 43 The Cassville Affairs – Mercer Univ. Press 17 Civil War Recreations – CWMedals.com ............. 24 Civil War Navy – The Magazine 7 College Hill Arsenal – Tim Prince ........................ 24 Colorado Gun Collectors Association Gun Show . 42 Dell’s Leather Works ............................................ 24 Dixie Gun Works Inc. 16 Gettysburg Foundation IBC Greg Ton Currency 34, 55 Gunsight Antiques 34 Harpers Ferry Civil War Guns 28 The Horse Soldier 7 Images of War Seminar ......................................... 43 “I thank the Lord I’m not a Yankee” – Book 47 James Country Mercantile 7 MKShows IFC, 16 Mike McCarley – Wanted Fort Fisher Artifacts 28 Military Images Magazine ...................................... 8 The National Heritage Collection ......................... 28 National Museum of Civil War Medicine ............. 24 N-SSA ................................................................... 43 Ohio Civil War, WWI, and WWII Show ................ 8 Poulin Firearms & Militaria Auctioneers BC Richard LaPosta Civil War Books 34 Rock Island Auction Company 9 Shiloh Chennault Bed and Breakfast 8 Suppliers to the Confederacy – Book 8 Ulysses S. Grant impersonator – Curt Fields 34 central Virginia battlefield trust Civil War Soldiers and Weather on Central Virginia’s Battlefields. By Tim Talbott 29 38 The Unfinished Fight The Enfield at Manassas Reconsidered. By Craig L Barry 10 American battlefield trust Preserve. Educate. Inspire. 53 Emerging civil war ECW Newsletter. By Chris Mackowski 32 civil war book reviews Timely Analysis of the Latest Research. 44 The graphic war Kimmel & Foster Part One. By Salvatore Cilella 14 Vision and Valor: The War Through Women’s eyes Women’s Roles in the War. By Juanita Leisch Jensen 66 This & That Lt. Colonel Fremantle, Welcome to Texas. By Gould Hagler 25

From the publisher

We are delighted to share the news, about the transformation of Civil War News ! After five decades of delivering captivating and thorough Civil War narratives to our audience in the form of a newspaper, we are now shifting to a bi-monthly magazine format. This change signifies more than a phase in our publication’s rich history; it marks a significant step towards creating more engaging, enduring, and enriching content for our readers and valued advertisers. This vision has been in progress since 2016.

The magazine’s premium pages offer an engaging reading experience. The crafted and organized content, free from the constraints of newspaper layouts transforms the exploration of historical stories into sheer joy. As a subscriber you’ll appreciate how this magazine seamlessly blends style with readability.

By subscribing, you can explore the perspectives and discoveries shared by historians and writers specializing in the Civil War. It’s an opportunity to engage with content that’s not only informative but also thought-provoking, crafted by experts in the field. Subscribing ensures you’re among the first to delve into groundbreaking research and diverse viewpoints. You become part of a community that values depth, excellence, and storytelling connections. Subscribing to this reimagined publication is not about receiving a magazine; it’s about immersing yourself in a narrative of the Civil War. Every issue is like an edition filled with insights and captivating visuals that you’ll want to revisit time and time again. It’s an investment in knowledge, motivation, and being part of a community that treasures the lessons and stories from the Civil War. Your subscription isn’t about acquiring a magazine; it opens up avenues to explore the past in an engaging manner.

What makes this magazine stand out is its commitment to showcasing exclusive articles. As a

subscriber, you’ll have access to aspects of the Civil War that have been overlooked or hidden for years. This exclusivity isn’t a benefit; it’s an expedition into territories of history.

Each edition will be carefully packaged in a polybag to guarantee it arrives in a condition reflecting the magazine’s standards. Your privacy and the quality of your reading experience are always our priorities as a publisher.

For 50 years, Civil War News has been a beacon for history enthusiasts, scholars, and the general public who are captivated by the tales and rich history of the American Civil War. Its commitment to delivering thorough content on events has solidified its position as a respected source within the Civil War community.

This new magazine design is tailored to appeal to an audience catering to those with an interest in the American Civil War, academic historians, and everyone in between. By exploring topics such as events related to the Civil War, in-depth articles from writers across the country, glimpses into civilian life, analyses of battles and key figures, nuanced discussions on slavery issues, and detailed examinations of military campaigns ranging from East Coast skirmishes to operations in the Trans Mississippi region, the magazine seeks to offer a well-rounded view of the Civil War era.

The transition of Civil War News to a magazine format signifies a milestone in its evolution, demonstrating responsiveness to changing media trends and a commitment to meeting audience preferences. Through a range of content that includes insights and personal narratives, the magazine aims to be a resource for enthusiasts interested in Civil War events, details, and material culture. This transformation respects the publication’s legacy while embracing opportunities, ensuring that stories, lessons, and impacts of the Civil War are portrayed with precision, depth, and complexity.

All subscriptions purchased or renewed at the higher rate of $41 will be prorated appropriately.

Sincerely,

Jack W. Melton Jr.

Publisher

6 Civil War News Magazine | May-June 2024

Subscribe online at

Subscribe online at

https://www.historicalpublicationsllc.com/site/subscription_services.html

7 Civil War News Magazine | May-June 2024 19th CENTURY LIVING HISTORY! James Country MERCANTILE 111 N. Main Liberty, MO 64068 816-781-9473 • FAX 816-781-1470 www.jamescountry.com Ladies – Gentlemen Civilian – Military • Books • Buttons • Fabrics • Music • Patterns • Weapons Mens, Ladies and Children’s • Civilian Clothing • Military Clothing • Military Accessories • Accoutrements Everything needed by the Living Historian! Our Clothing is 100% American Made! The home of HOMESPUN PATTERNS© Join the Crew! civilwarnavy.com 1 Year—4 Issues: $37.95 Subscribe Now at civilwarnavy.com Or send a check to: CSA Media, 29 Edenham Court, Brunswick, GA 31523 International subscriptions subject to postage surcharge.

8 Civil War News Magazine | May-June 2024 Next year’s show is May 3-4, 2025

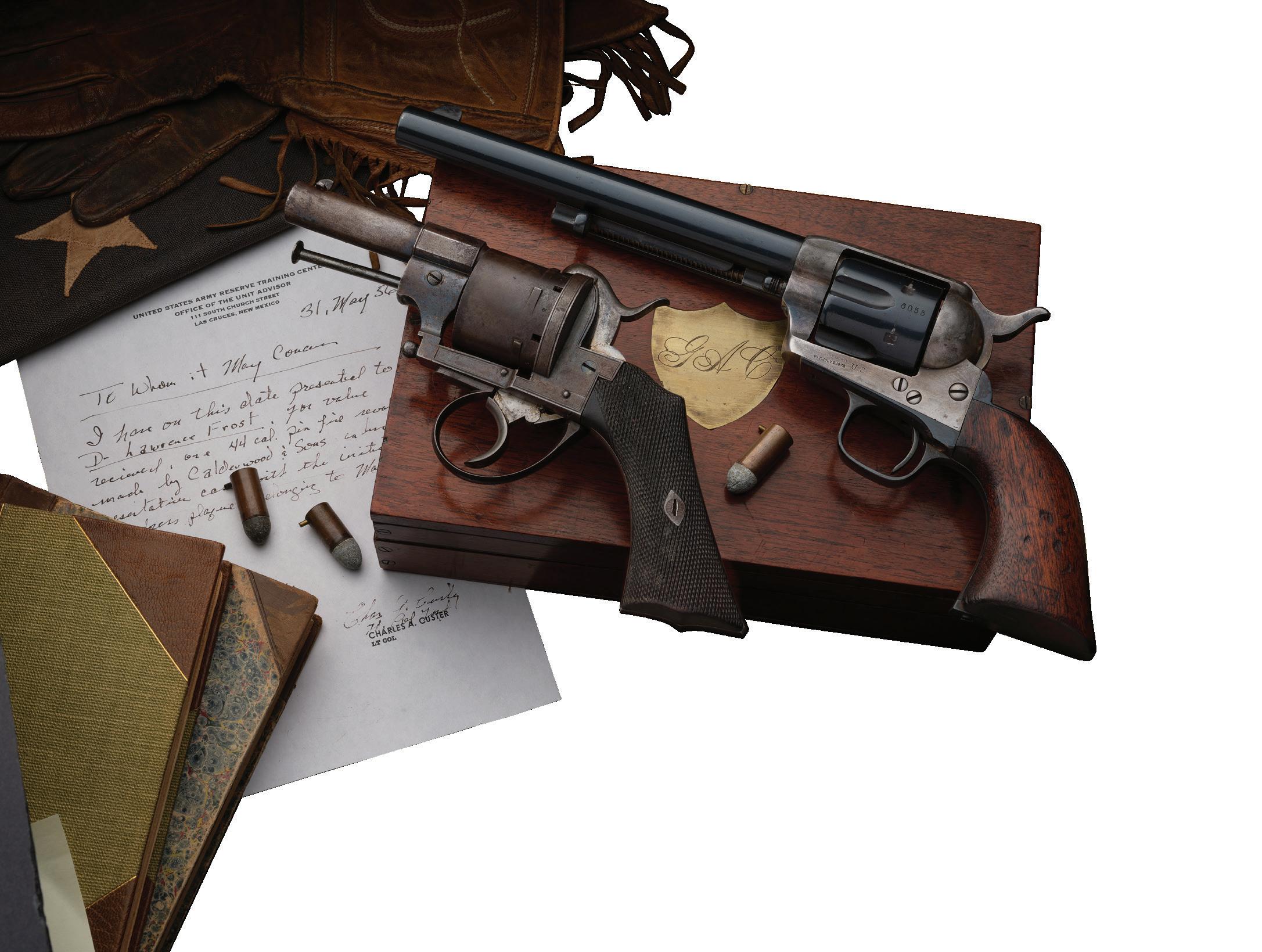

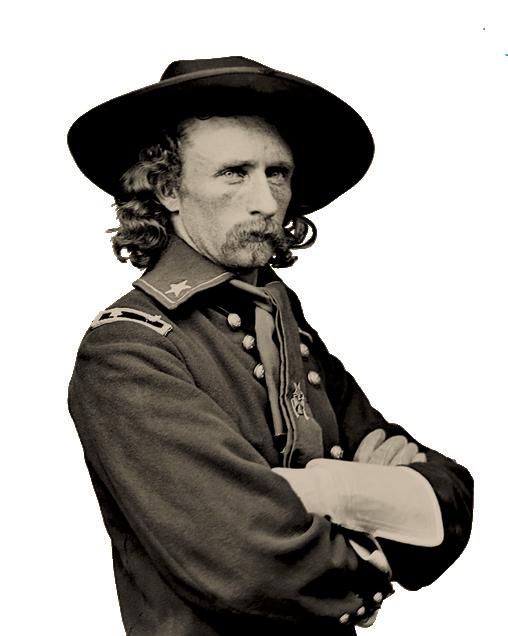

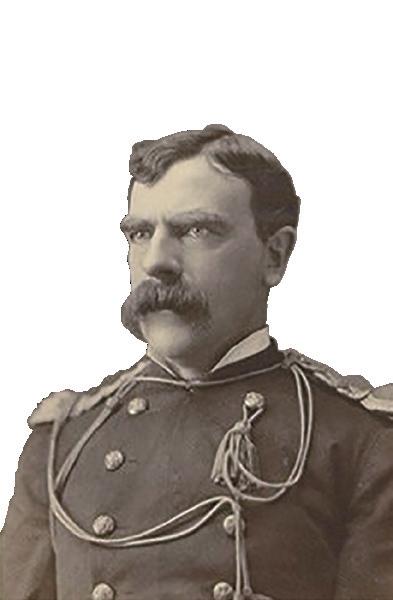

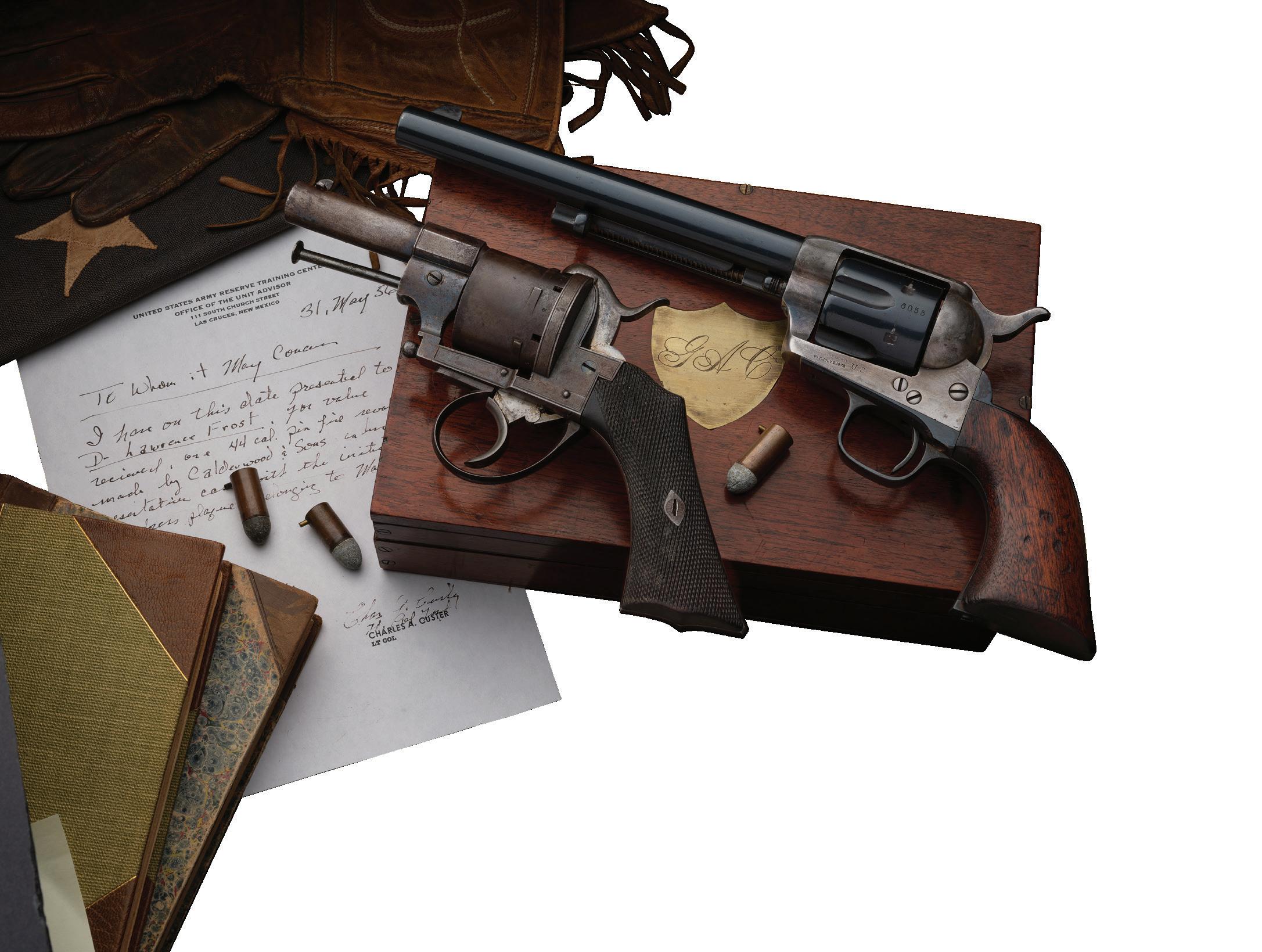

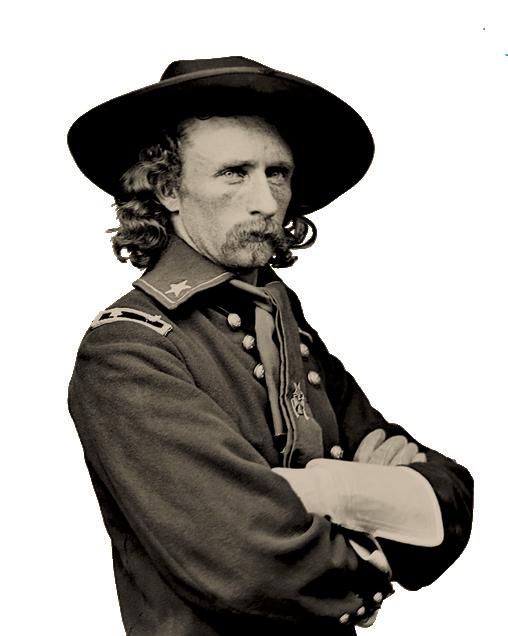

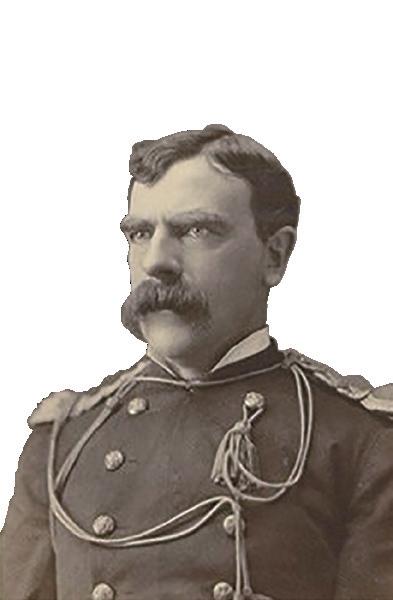

Rare, Well Documented and Historic B Company No. 102 U.S. Colt Model 1847 Walker Percussion Revolver Marked for Mexican General and Governor of Coahuila Andres Viesca with Herb Glass Authentication Letter Historic and Exceptional Engraved Civil War Martially Inspected New Haven Arms Co. Henry Lever Action Rifle Identified to a Member of the U.S. 3rd Veteran Volunteer Infantry Extremely Rare and Outstanding Documented Iron Frame New Haven Arms Co. Henry Lever Action Rifle Captain Myles Moylan History Lives Here Over 100 Civil War items in this auction Rock Island Auction Company Fine, Historic, & Investment Grade Firearms Bedford, Texas Premier Auction May 17 TH , 18TH & 19TH FOR YOUR COMPLIMENTARY CATALOG Call 800-238-8022 (Reference this ad) ® ® Historic Cased Factory “Vine Scroll” Engraved Colt Model 1860 Army Percussion Revolver with Ebony Grip Passed Down through the Family of Second Lieutenant Huntington F. Wolcott of the Second Massachusetts Cavalry WWW.ROCKISLANDAUCTION.COM RIAC IS ALWAYS ACCEPTING QUALITY CONSIGNMENTS, ONE GUN OR AN ENTIRE COLLECTION! Call: 800-238-8022 or Email: guns@rockislandauction.com 3600 Harwood Road, Bedford, TX 76021 ∙ P: 800-238-8022 ∙ F: 309-797-1655 ∙ info@rockislandauction.com ∙ Auctioneer: Patrick Hogan (#18366) ∙ Buyers Premium 17.5% Catalog Online Now Historic Documented Ainsworth Inspected Prime 7th Cavalry Range “Lot Six” U.S. Colt Cavalry Model Single Action Army Revolver Accompanied by Kopec Letters and Additional Information Attributing the Revolver to Captain Myles Moylan, Commander of Company A of the 7th Cavalry, Medal of Honor Recipient, and Veteran of Numerous Significant Battles, Including Gettysburg, Little Bighorn, and Wounded Knee Large Wragg & Sons Spear Point Bowie Knife with Desirable HalfHorse, Half-Alligator Pommel and Sheath Rare Civil War U.S. “O’Donnell’s Foundry” 6-Pounder Wiard Rifle with Carriage and Caisson Historic

Action

Revolver with “G.A.C.” Inscribed Case and Receipt from Family Descendant Lt. Col. Charles A. Custer Identifying the Cased Set as Owned by Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer

Calderwood & Son Double

Pinfire

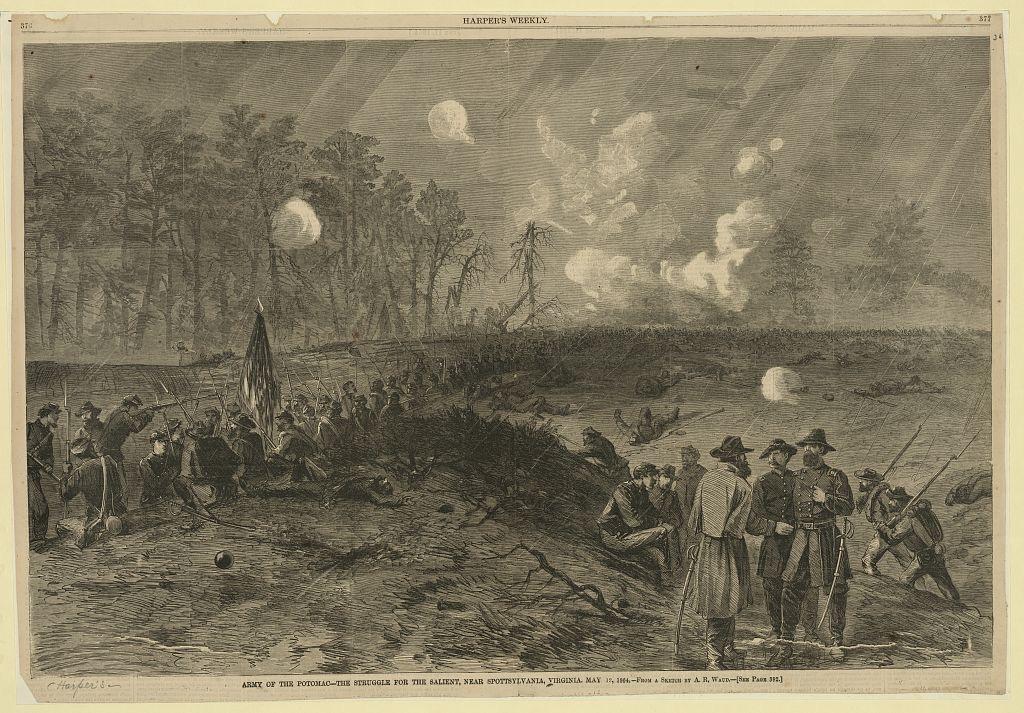

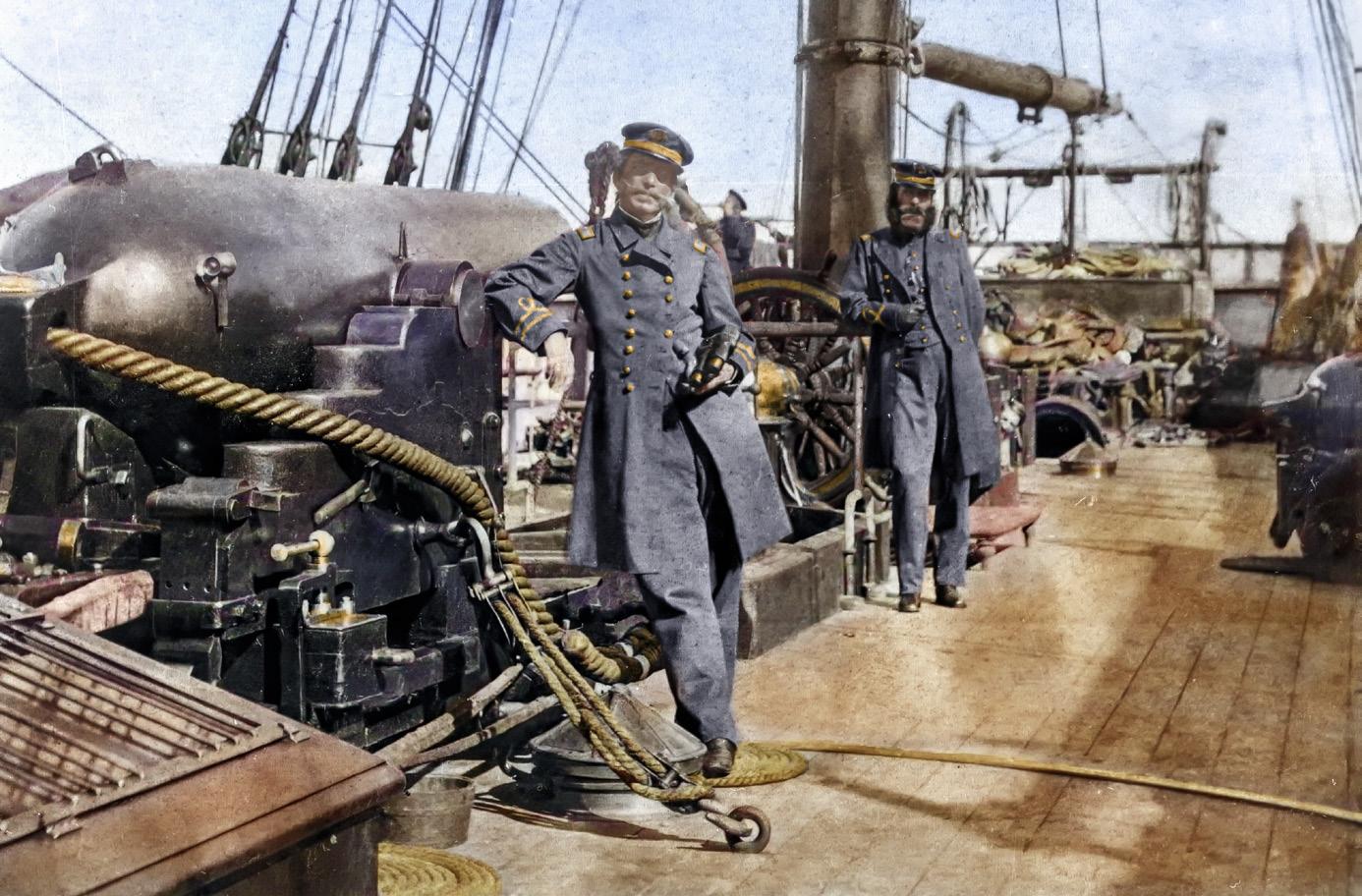

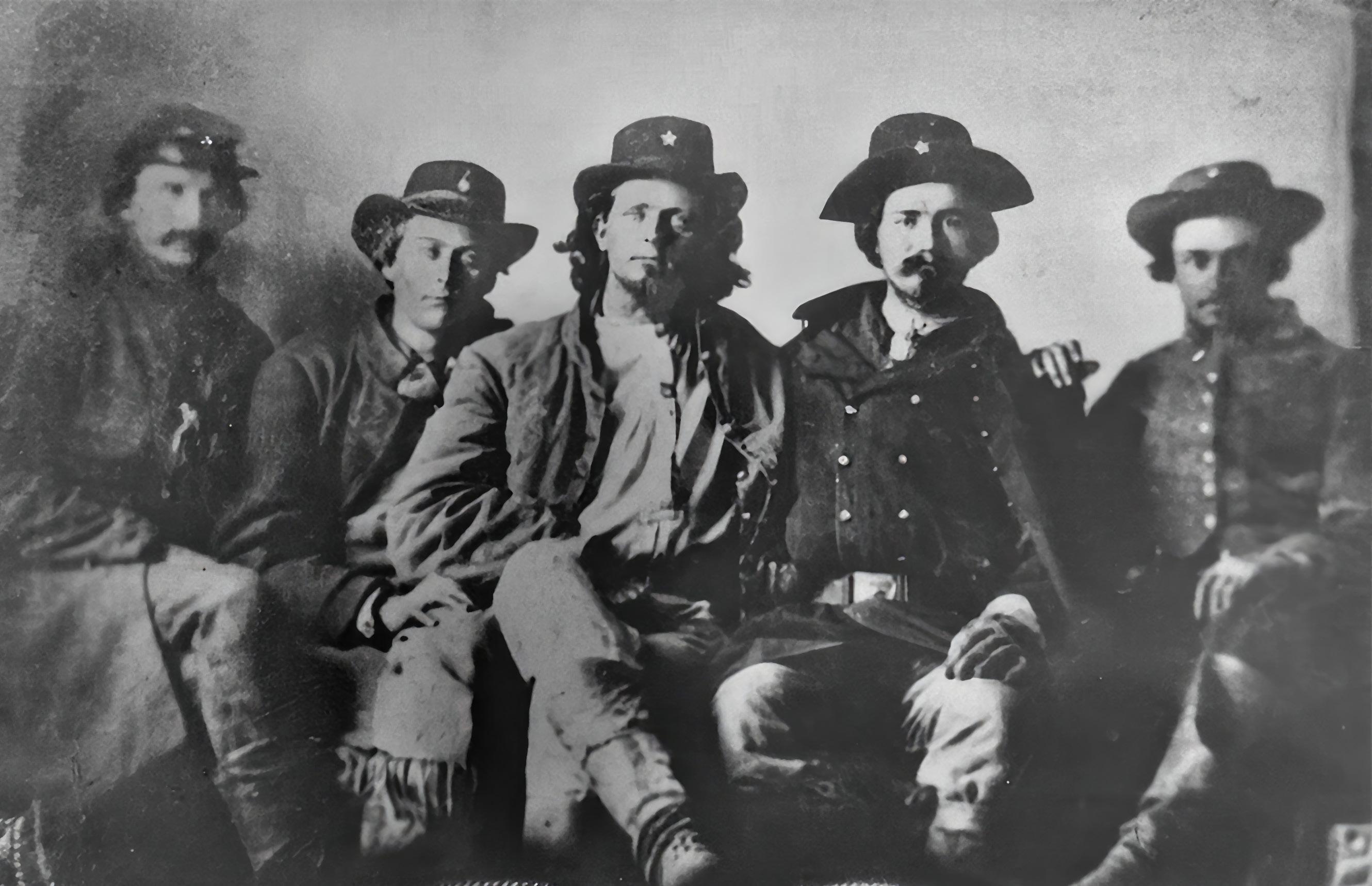

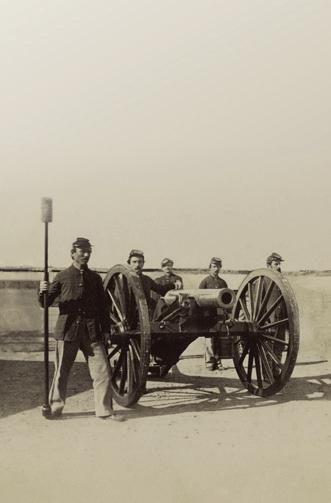

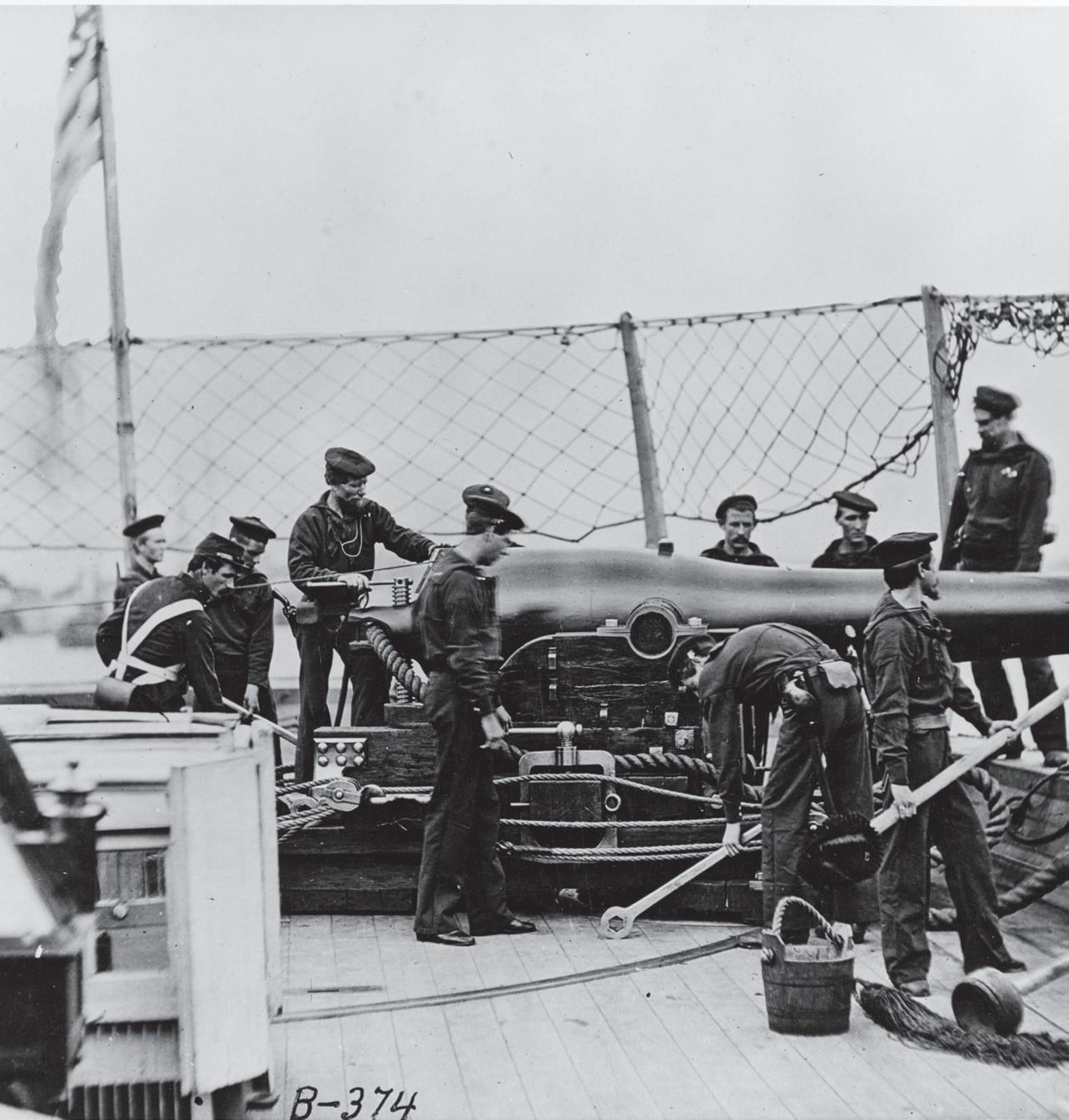

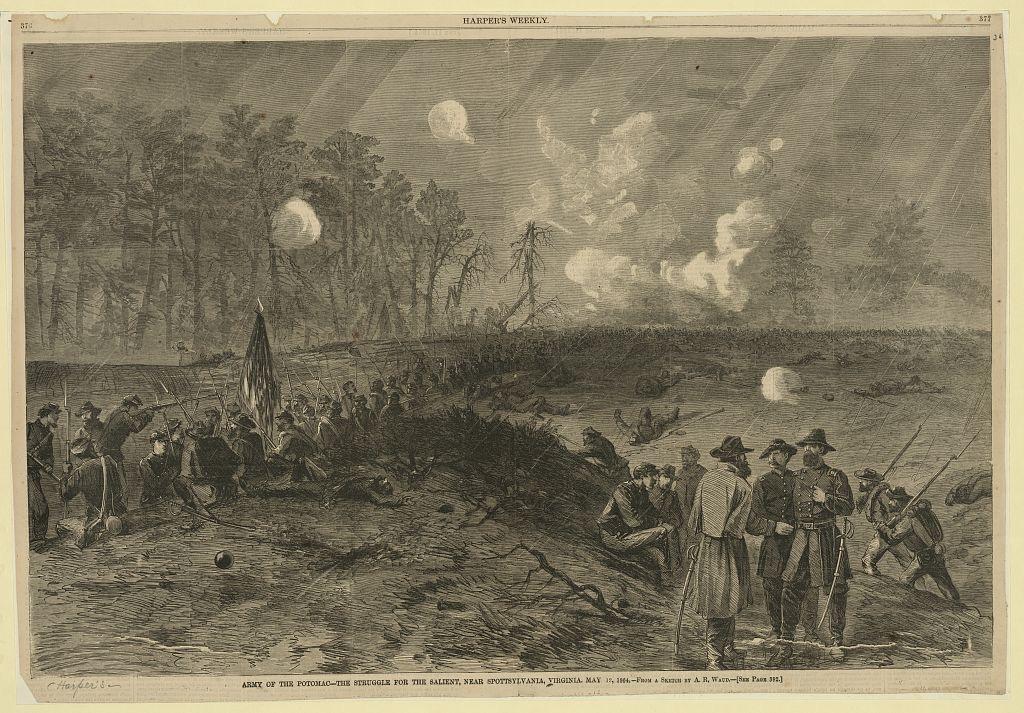

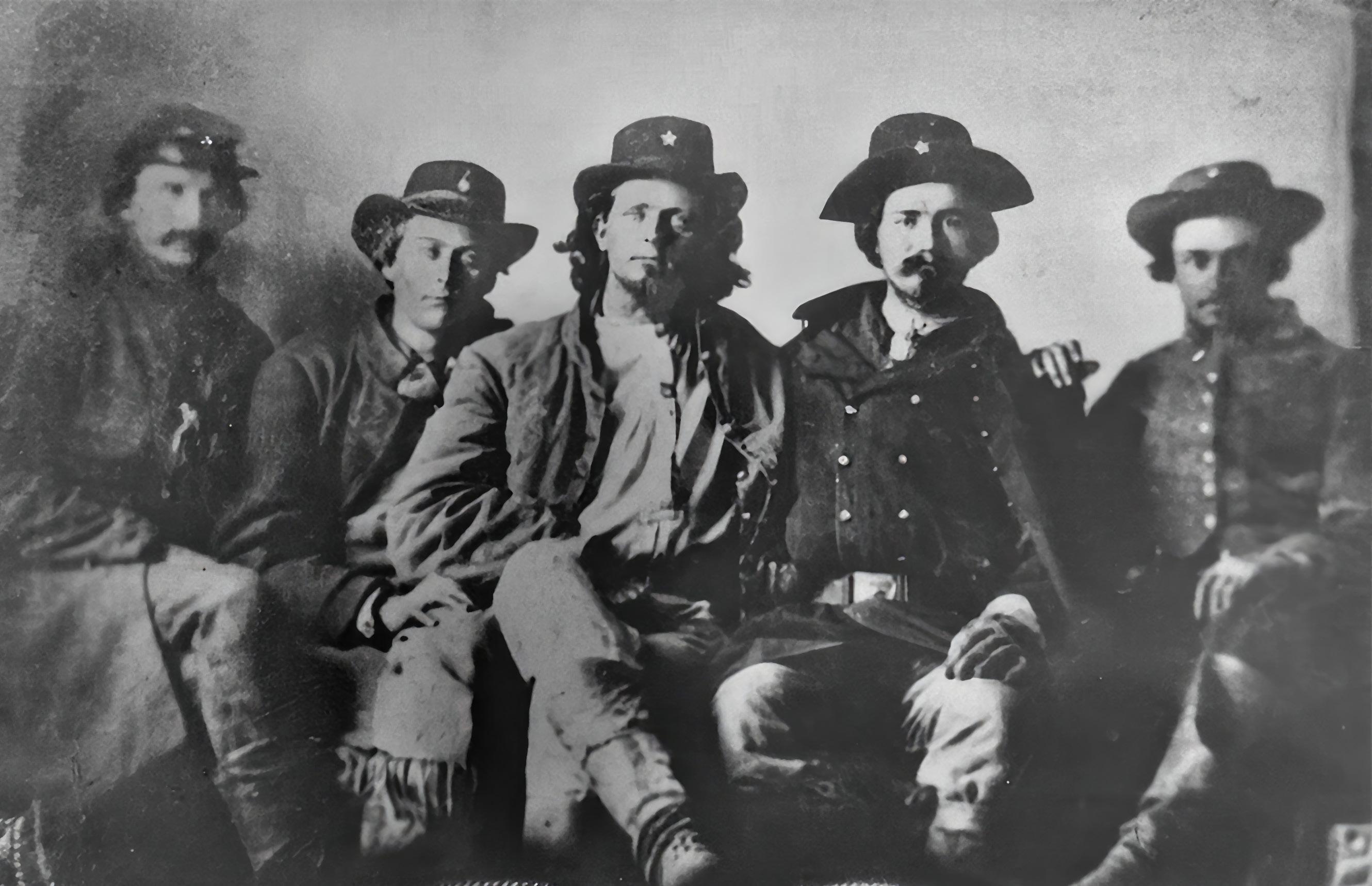

THE UNFINISHED FIGHT: THE ENFIELD AT MANASSAS RECONSIDERED

By Craig L. Barry

“at [First] Manassas, over thirty-five thousand Union troops went into battle, armed primarily with aging smoothbores. Their final assault up Henry Hill came within mere yards of carrying the day and breaking the back of Confederate resistance. That final gallant charge, however, was shredded by the concentrated volleys of Stonewall Jackson’s men, armed primarily with newly issued Enfield Rifles that could kill at four hundred yards and were murderous at a hundred yards or less, a range at which the smoothbores of the Union were still all but useless.”

– William Forstchen, Bill Fawcett, It Seemed like a Good Idea: A Compendium of Great Historical Fiascoes (1988)

The passages highlighted beg further discussion beginning with “…armed primarily with newly issued Enfield Rifles.” How could that possibly be correct? How many Enfields were in Confederate hands as early as July 1861? Lacking the ability to produce their own infantry arms in sufficient quantity to meet their needs, the Confederacy sent agents to Europe to procure the best infantry arms that could be found. Caleb Huse’s initial efforts resulted in the purchase of 3,500 rifles from London gun-making firms in April 1861.

According to Stephen C. Tucker in A Short History of the Civil War at Sea, these were loaded on the 700-ton steamer Bermuda. On April 22, 1861, the Bermuda steamed from Falmouth and ran the Union blockade via Nassau, arriving in Savannah, Ga., on September 18, 1861. The majority of these rifles were “London guns, Barnett marked.” The rest (1,200) were manufactured by the London Armoury Co. These were the first Enfield rifles to reach Confederate soil since the start of the war. Ruling out time travel, it is doubtful that very many of those Enfield rifles could have been in use by General Jackson’s brigade for the fighting at Henry Hill two months earlier in July 1861.

If not Enfield rifles, what were General Jackson’s troops issued early in the war? Well, it appears they received a variety of muskets, just like most other infantry units. In May

1861, the 4th Virginia Infantry, Co. H (Rockbridge Grays) left Lexington, Va., for Harper’s Ferry with borrowed muskets from the Virginia Military Institute. These weapons were M1851 Springfield Cadet smoothbore muskets, a scaleddown version of the U.S. Model 1842. By September 1861, the Grays still had them as the Commonwealth of Virginia asked for the return of VMI’s weapons, prompting General Jackson to respond to the Governor’s office stating, “I regret to say that Capt. Updike’s company (Rockbridge Grays) has not returned the cadet muskets and I fear that I will be unable to forward them to the VMI until in their place can be supplied other percussion muskets.”

In case that might be deemed an isolated incident, it has been noted that the Shenandoah Sharpshooters, Company K, 33rd Virginia, were initially issued outdated flintlock muskets. No doubt, the men in that company felt the Rockbridge Grays were lucky, since at least they had percussion muskets and not the less reliable flintlock smoothbore muskets. On May 26, 1862, one of the Liberty Hall Volunteers, 4th Virginia Co. I, wrote home that he was carrying a “Belgian musket,” most likely an imported smoothbore converted to percussion. Various accounts also documented that most of Jackson’s men were not fully armed with imported Enfield rifles before 1863.

The variety of muskets early in the war as noted above is, if not all inclusive, exactly what you would expect. Were there

anything but smoothbore muskets in use at First Manassas? It appears there were scattered rifles in use by flank companies and skirmishers, just not Enfield rifles imported from Britain. General Jackson’s 4th Virginia Co. F was initially issued U.S. Model 1855 two-band “Harpers Ferry” rifles with saber bayonets seized at the Federal Armory in Harpers Ferry, Va., in April 1861. There were also known to be a number of U.S. Model 1841 Percussion rifles (with and without bayonet lugs) in Southern Arsenals before the war. There were not enough Enfield rifles documented as received by either side to be found in any significant numbers during mid-1861.

Moving on to more foolishness from this remarkable passage “…murderous at a hundred yards or less, a range at which the smoothbores of the Union were still all but useless.”

The improved accuracy of the .58 caliber U.S. Model 1861 and .577 caliber Pattern 1853 Enfield rifle-muskets is not at issue. At longer ranges, beyond 100 yards, a single soldier armed with a smoothbore musket is not likely to hit a lone enemy target. At the same time, it is important to note that the troops were clustered in tight formation and not spread out like targets on a firing range.

It is true that aimed at a stationary silhouette; the rifle-musket can hit easily at a distance greater than 100 yards, assuming the man firing the weapon is properly trained in its use. To illustrate this, data and photographs from comparative firing of the “New Rifle Musket, Calibre .58’’ which most likely means the U.S. Model 1861, and the “Smoothbore Musket, calibre .69’’ which might have been a converted flintlock Model 1816/22 or the Model 1842, is available in the National Archives. Claud E. Fuller used this same data in The Rifled Musket.

“I REGRET TO SAY THAT CAPT. UPDIKE’S COMPANY HAS NOT RETURNED THE CADET MUSKETS AND I FEAR THAT I WILL BE UNABLE TO FORWARD THEM TO THE VMI UNTIL IN THEIR PLACE CAN BE SUPPLIED OTHER PERCUSSION MUSKETS.”

At 100 yards, the U.S. Model 1861 rifle-musket hit between 48 and 50 times out of 50 shots per target, getting less than 50 hits just once. Accuracy fell off, though; at 200 yards, the hit rate ranges from 41 down to 32. At 300 yards, accuracy is worse, between 23 and 29 hitting the target. At 500 yards, the hit rate was between 12 and 21. A moderate wind existed during all firings of the rifle-musket. The smoothbore musket was tested in two categories, with and without buckshot. At 100 yards, again with 50 shots of ball being fired, between 37 and 43 hit, a hit rate that was not as good as the rifled

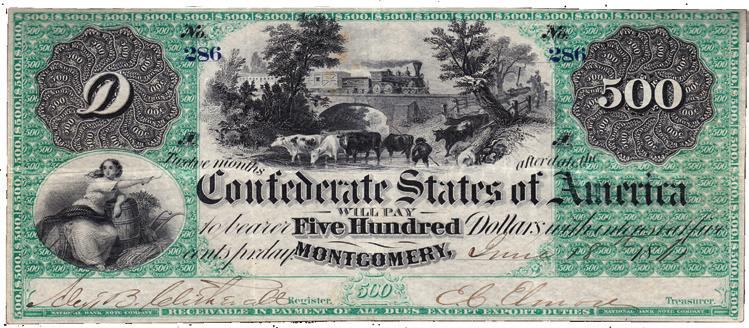

U.S. .58 caliber Minié ball (bullet). Enfield .577 caliber bullet.

U.S. Model 1861, but respectable. However, most smoothbores were not fired with a single ball alone, but rather with “buck and ball” which included three smaller .31 balls in addition to the single large .66 caliber lead ball. With buckshot added to the rounds, the hits jumped dramatically. Still firing 50 times, the accuracy with the buckshot at 100 yards ranged between 79 and 84 hitting, while the balls hit between 31 and 36 times. Note the increase in overall hits because of the number of projectiles. The point being, firing at massed troops inside 100 yards, the smoothbore musket was very effective. Far from “useless,” it could be argued purely on the basis of “hits,” the smoothbore was perhaps more effective inside 100 yards than the rifle-musket. That is one reason why the “obsolete” smoothbore muskets were still in service on both sides when Lee surrendered at Appomattox Courthouse in 1865. A good source on the extensive use of the smoothbore musket during the Civil War is Bloody Crucible of Courage by Brent Nosworthy.

The issue of what General Jackson’s forces had in hand during July 1861 is not widely in dispute if existing records are consulted, limited though they are. The question regarding whether any other Enfield rifles could have been in the ranks at all for First Manassas is a topic worth considering. Specifically, the possibility of Wade Hampton’s self-purchased Enfield rifles being used during the battle in question, or perhaps procured as a battlefield pick-up. After all, there is at least one-period account of a Confederate soldier at First Manassas claiming to pick up an Enfield rifle from a fallen Union soldier and continuing the fight so armed. If so, he would have also needed the supply of .577 caliber rounds in the cartridge box, too, and would have been out of the fight once it was empty.

Accounts from soldiers about exactly when and where they procured a battlefield pick-up can be unreliable. There is a display in the Civil War portion of the Tennessee State Museum where an 1861 Colt Special Model rifle-musket is shown. The caption accompanying the display states the soldier picked up the piece from the battlefield at Shiloh in April 1862. The U.S. government did not receive the first deliveries of Colt Special Models until August 1862. Once again, ruling out time travel this soldier’s recollection of his battlefield pick-up cannot be correct.

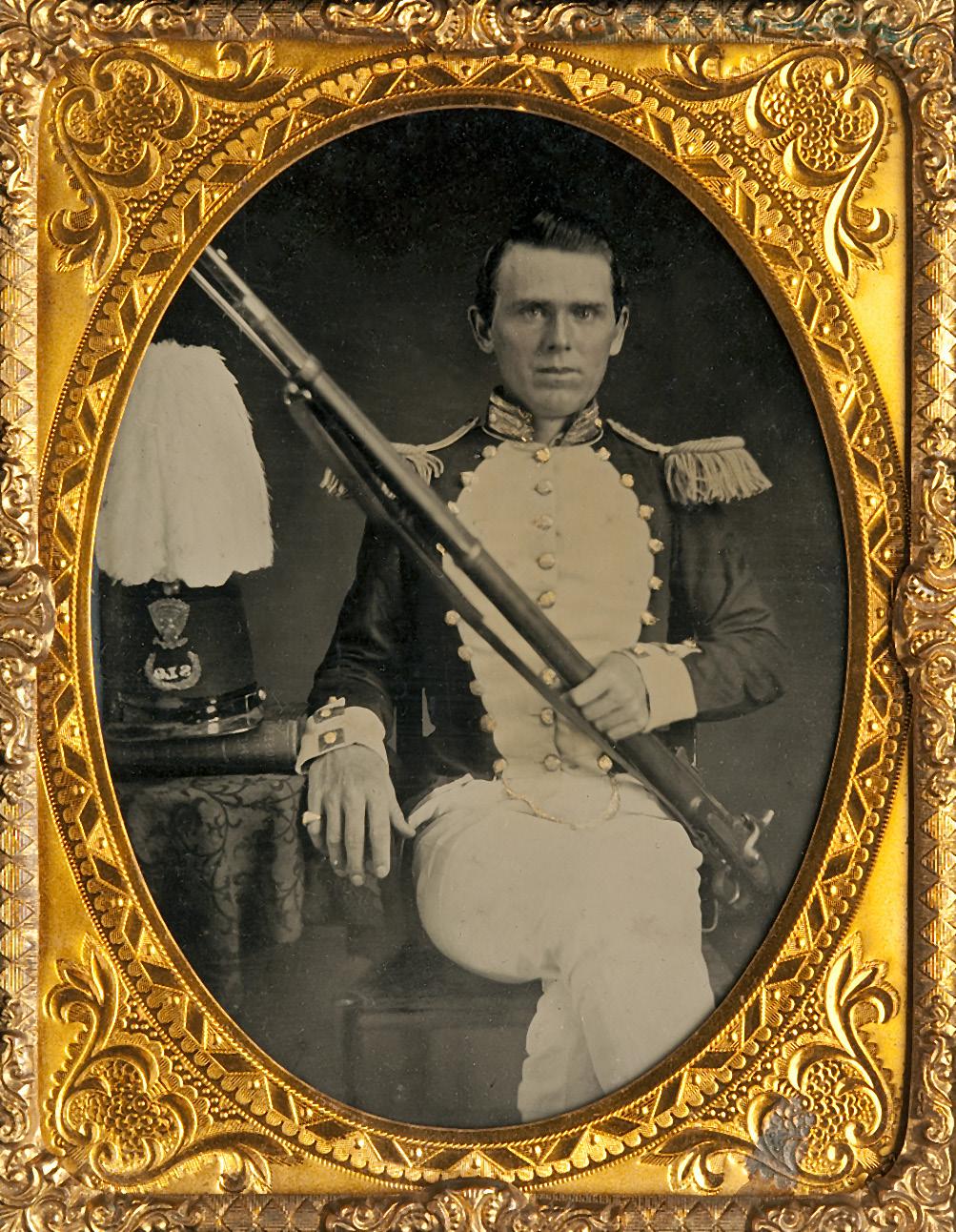

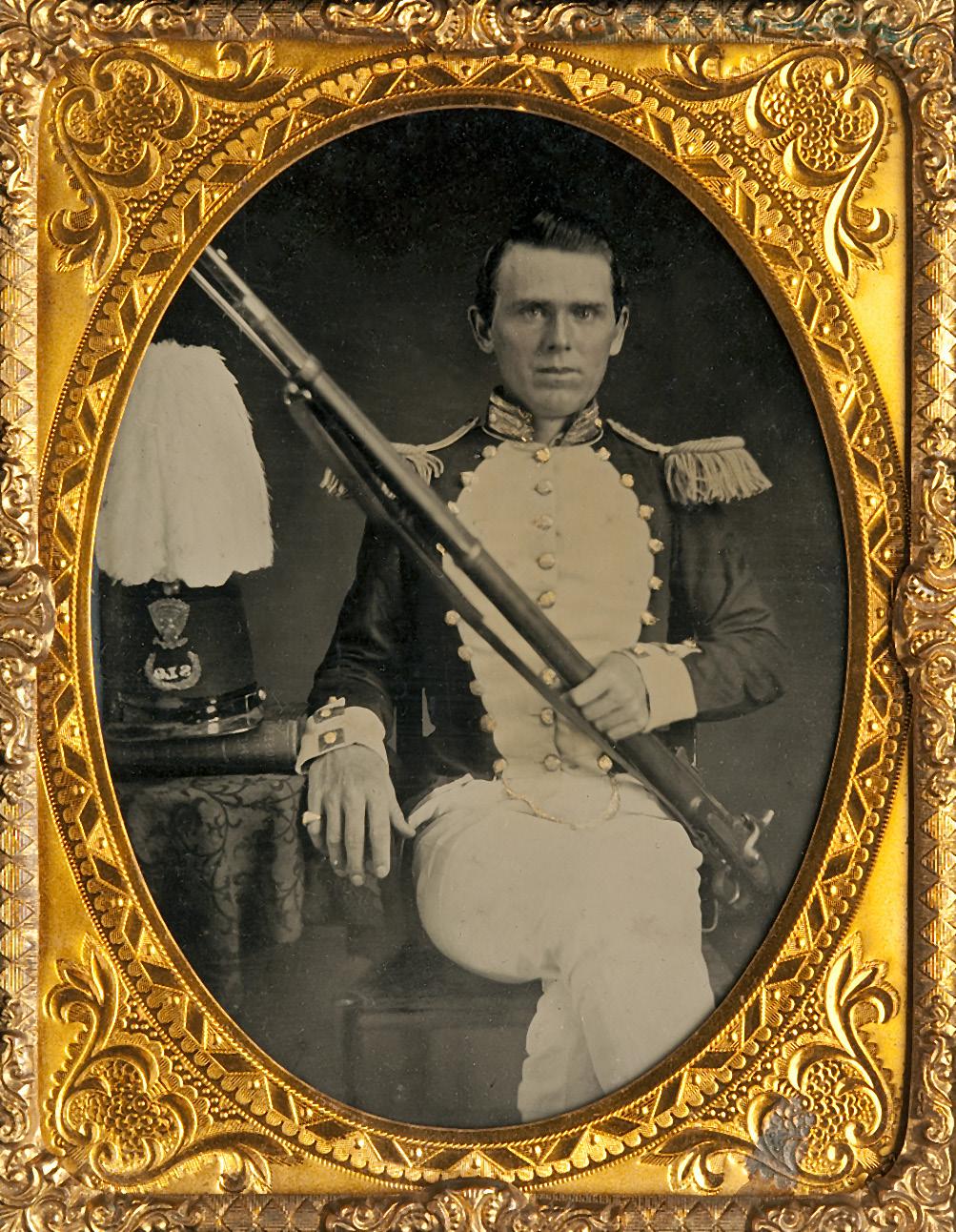

Above: Confederate infantryman wearing homespun shell jacket and trousers, plain non-military buttons, and kepi. Soldier holds a blockade run Pattern 1853 Enfield riflemusket and the accompanying English angular bayonet in its scabbard on his belt. (Liljenquist Family Collection of Civil War Photographs) (Library of Congress).

It is well known that besides receiving imported modern weapons from overseas, many Confederates procured rifled arms courtesy of the Union Army. Unfortunately, putting any sizeable number of Enfield rifles in Union hands during mid1861 is similarly problematic. Federal purchasing agents arrived in London a few weeks after the Confederates. Huse had already contracted with many London firms for their entire available output, so Federal purchasers largely fell back on Birmingham; the first dribs and drabs from those early contracts began to arrive in August 1861.

However, some purchasing agents for the states of New York and Massachusetts beat both the Federal and Confederate governments to England. Caleb Huse wrote that before the Confederate contract with London Armoury could be filled, the firm had to complete an earlier order for Massachusetts. The following passage suggests there were at least some Enfield rifles in the hands of other Massachusetts volunteers as early as July 10, 1861, if not with Union troops down in Virginia fighting the Confederates.

A letter to the Greenfield Gazette and Courier newspaper follows, which was in publication during this period. Still, I could not find the original archived newspaper article or the

letter of that date referenced here. Don C. Williams quotes the letter is his piece on The Enfield Rifle in the 28th Massachusetts, which tracks with what other soldiers noted about receiving them. The letter reads as follows:

Camp of the 10th Reg’t Mass Volunteers, Hampden Park, Springfield, Massachusetts July 10 [1861]

“…Friday morning the regiment marched to the U.S. Armory and returned the muskets loaned them for the purpose of drill, and in the afternoon we received our full supply of the Enfield rifled musket. For this the Regiment may well thank our efficient Colonel, whose influence has procured for us so fine an arm; whilst other Regiments are obliged to take the guns we returned, smooth bore muskets of the old model . . . The Enfield gun, purchased by the State (of Massachusetts) in England, though differing in many respects from the Springfield rifled musket, is a handsome and no doubt serviceable weapon, and I think fully equal to the Springfield arm…”

Along the same lines, the History of the First-Tenth-Twentyninth Maine Regiment, by Maj. John M. Gould (1871) notes the following a few months later:

“Oct. 21st [1861], new muskets were delivered to the men,

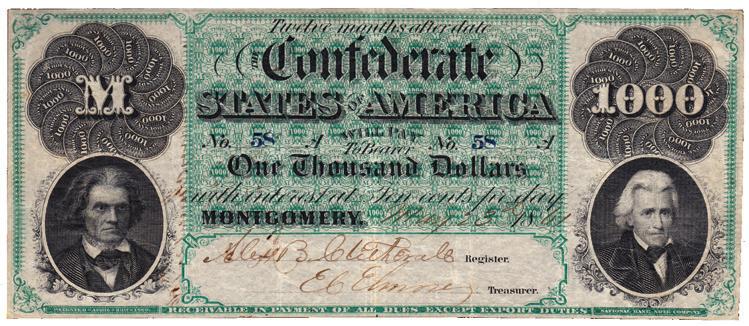

Below: Unidentified member of the Sumter Light Guard, later Co. K, 4th Georgia Infantry in his pre-war militia uniform holding a Pattern 1853, Type II, rifle musket. Note the wide front band.

British Military Pattern 1853 Type III Enfield rifle musket .577 caliber, 39-inch barrel. Although the Pattern 1853 Enfield rifle-musket was the second most used infantry long arm on both sides during the American Civil, those guns produced at the Royal Small Arms Factory (RSAF) at Enfield Lock, like the one pictured below were not acquired by either side. The “ENFIELD” marked guns were British military property that was not exported for use by either side during the war. While some obsolete British military arms were used during the war, current production guns from the British national armory were not, and the Pattern 1853 Enfield Rifle Muskets acquired by both sides were commercial guns, produced by various English contractors. The RSAF-produced Enfields were some of the highest quality P1853s produced during the era, as they were fully interchangeable parts guns, built primarily on Americanproduced machinery, set up by James Burton, former Harpers Ferry Master Armorer, who would later oversee the Confederate Richmond Armory and then all Confederate government armories. (Atlanta History Center, Beverly M. DuBose Jr. Collection)

1st Mainers. “Had we not been promised a new blue uniform and Springfield muskets?” To be sure we had the blue uniform and a good outfit in every way, “but look at these Enfield muskets,” said they, “with their blued barrels and wood that no man can name!” They were not a bad weapon, however, differing little from the Springfield, in actual efficiency, weight, length, and caliber, but far behind in point of workmanship

Regarding Wade Hampton and his legion’s weaponry, additional research revealed some information that may be of interest on the topic of their privately purchased Enfield rifles and who received them. Stephen Wise noted in Lifeline of the Confederacy: Blockade Running During the Civil War (1988) that the first blockade runner to deliver Enfields to the Confederacy was the steamship Bermuda . It was from the Enfield rifles aboard the Bermuda that “Wade Hampton supplied his Legion with 200 Enfield rifles, 20,000 Enfield cartridges and two six pound [3.67-inch] rifled field pieces.” We also know the Bermuda arrived in Savannah on September 18, 1861, too late for any of its cargo to be used at First Manassas.

Finally, which of Wade Hampton’s troops eventually got those very first Enfield rifles that ran the blockade and landed in Savannah? The unit known

as the Washington Light Artillery in Hampton’s Legion was issued the Enfield rifles, and actually “won” them as part of a battalion drill competition conducted by General Hampton. The contest was judged a tie, with the other winning unit (Company H, German Volunteers) receiving the two rifled artillery pieces. A review of the record indicates that the German Volunteers were not formed and mustered in at Charleston, S.C., until August 22, 1861.

They departed from Charleston for Virginia by rail in September 1861. Again, this suggests a later date than First Manassas in July 1861 for the potential use of the first shipment of Wade Hampton’s Enfield rifles, as well as any other weapons that came in on the Bermuda

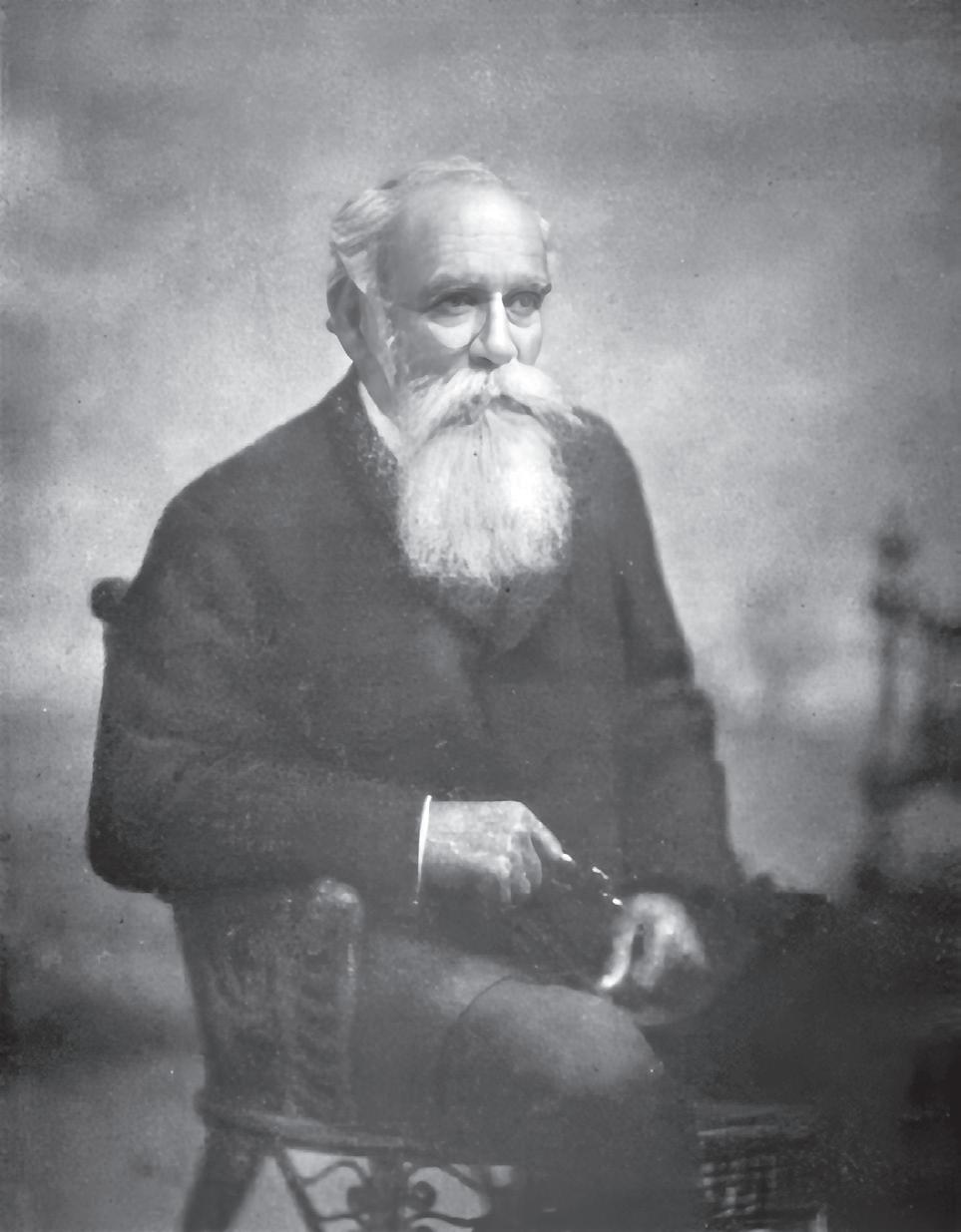

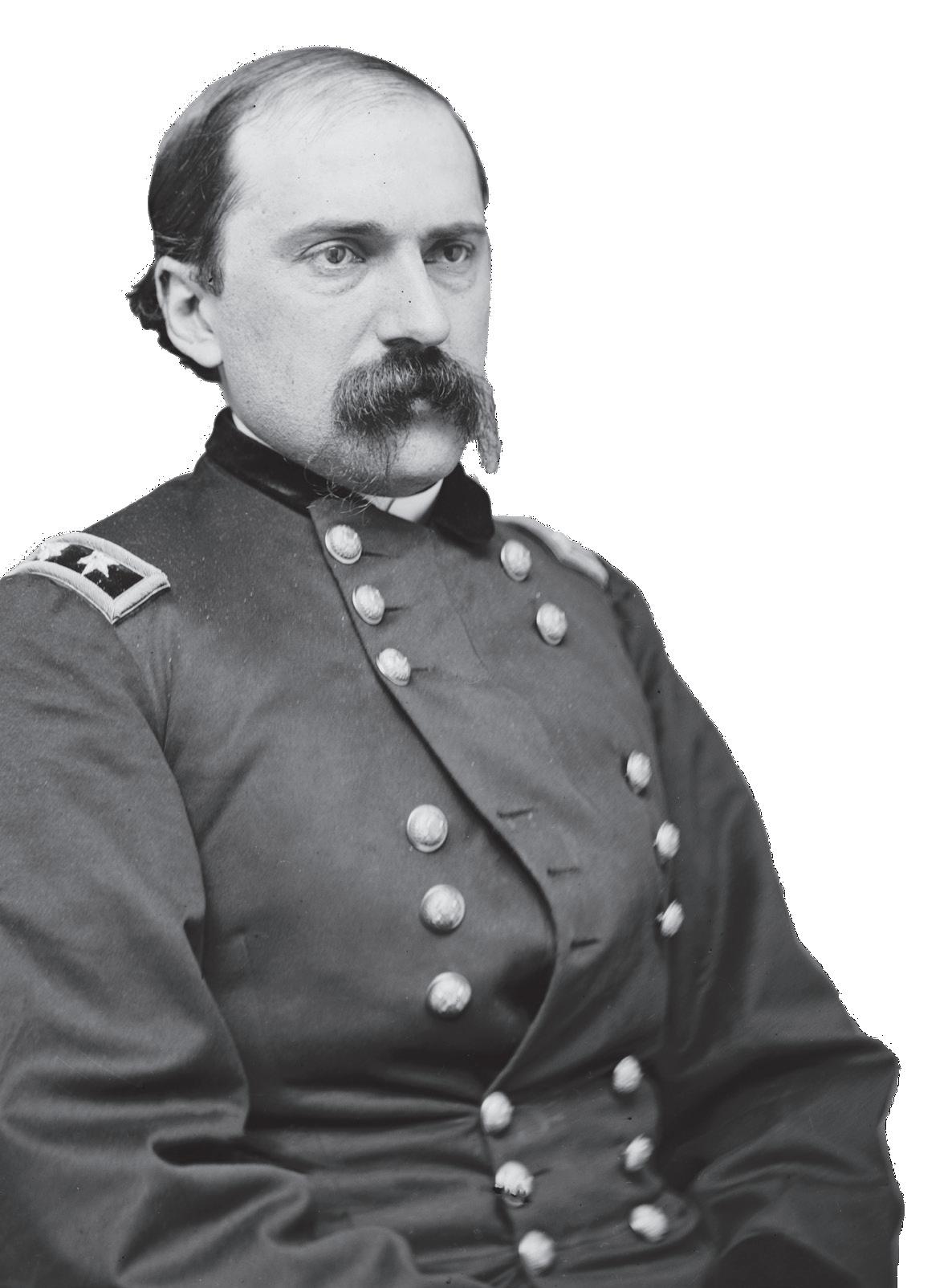

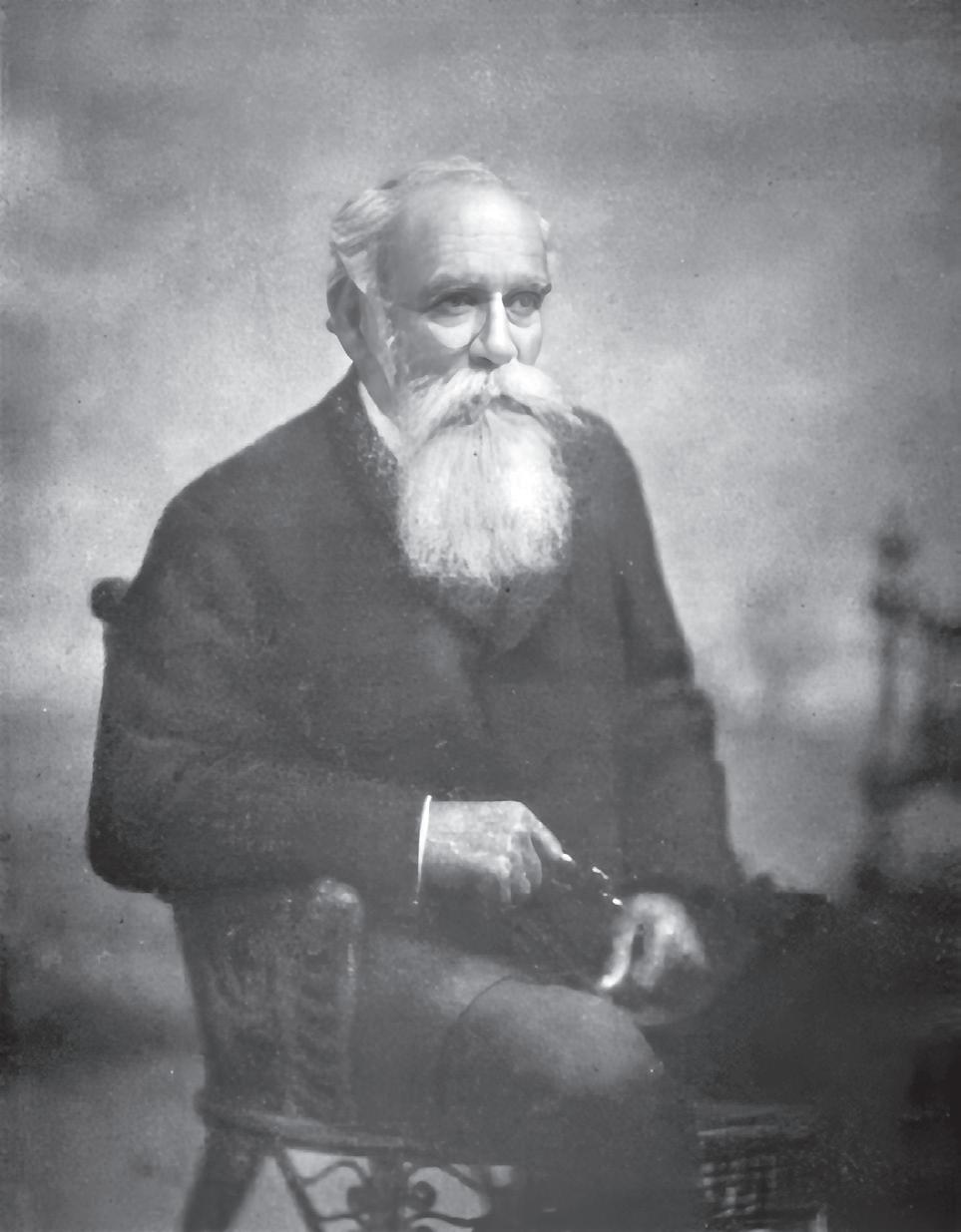

During the Civil War, Major Caleb Huse (Feb. 11, 1831–March 12, 1905) served as an arms procurement agent and purchasing specialist for the Confederacy. (Public Domain)

C raig L. B arry was B orn in C har L ottesvi LL e , v a h e hoL ds his B a and M asters degrees fro M U n C (CharLotte). Craig served T he W aT chdog c ivil W ar Q uar T erly as a sso C iate e ditor and e ditor fro M 2003–2017. T he W aT chdog p UBL ished B ooks and C o LUM ns on 19 th - C ent U ry MateriaL he is the aUthor of severa L B ooks in CLU ding T he civil War MuskeT: a handbook for h is Torical a ccuracy (2006, 2011), The unfinished fighT: essays on c onfederaT e M aT erial c ul T ure voL. i and ii (2012, 2013). he has aLso pUBLished foUr Books in the suppliers To The confederacy series on e ng L ish a r M s & a CC o U tre M ents , Q U arter M aster stores and other eUropean iMports.

. . .”

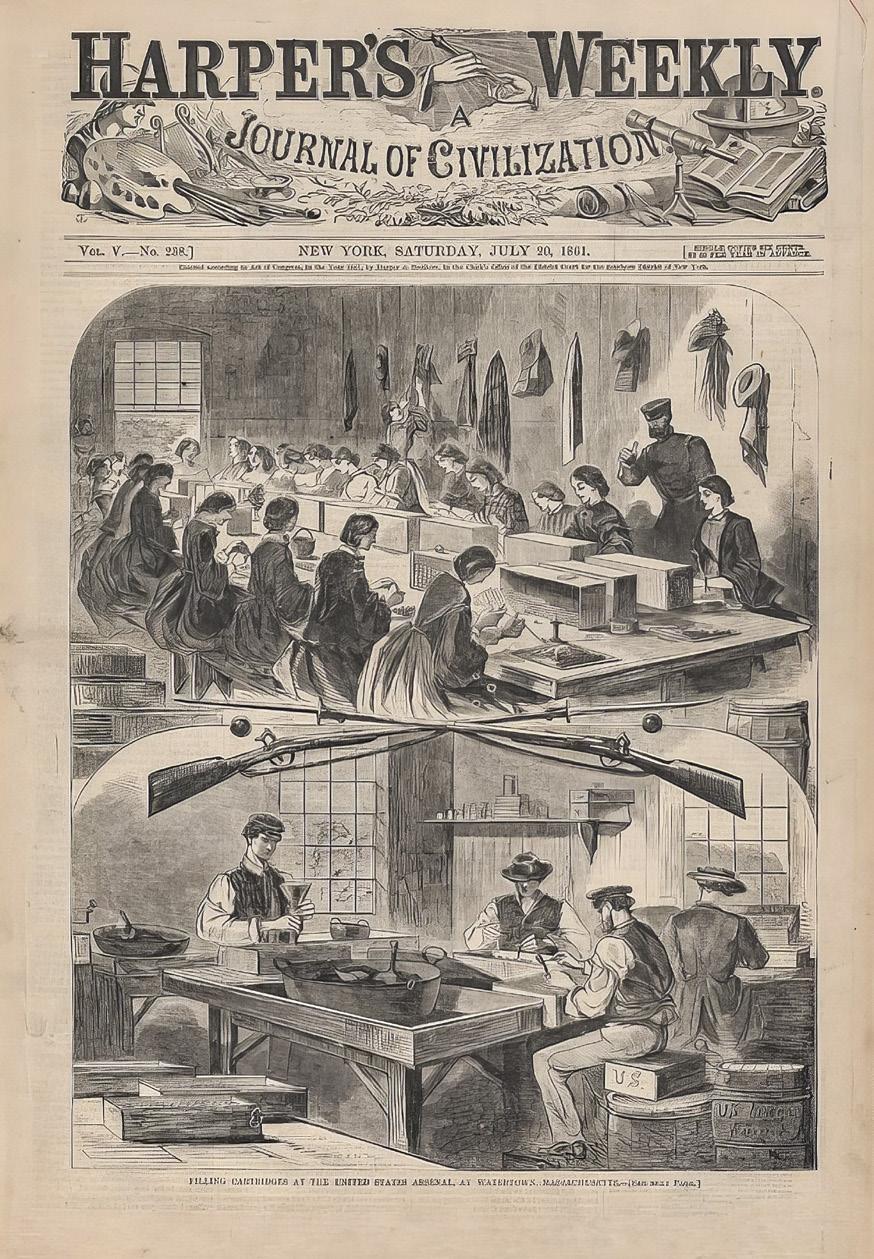

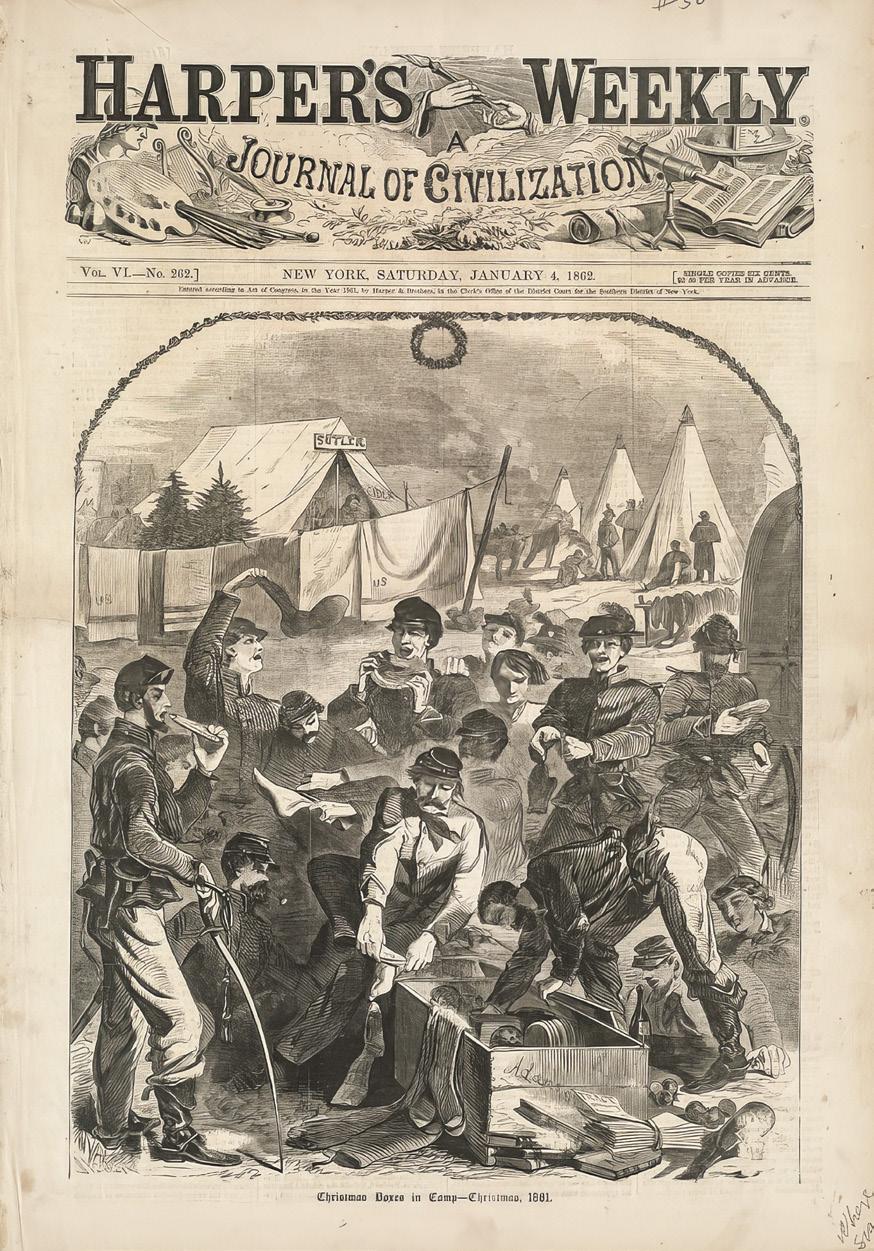

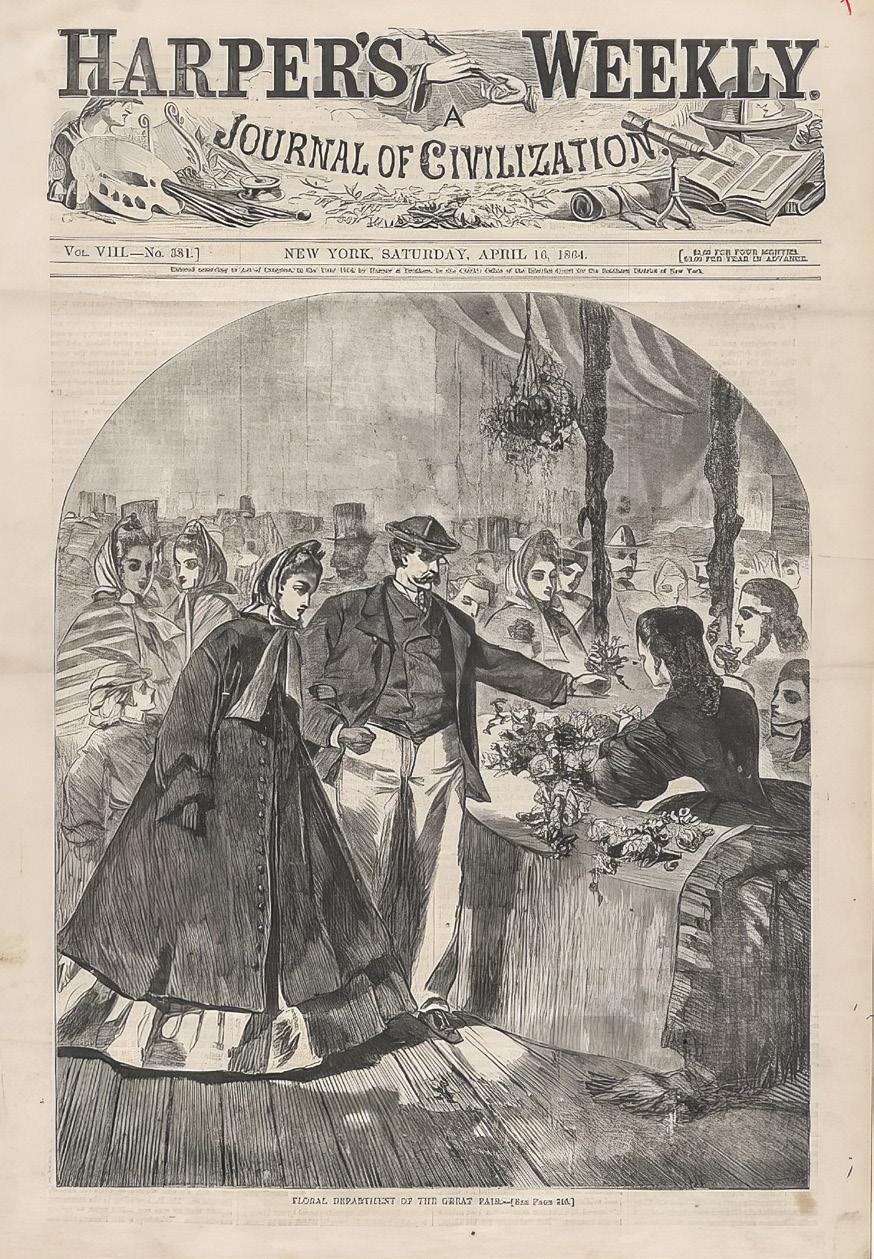

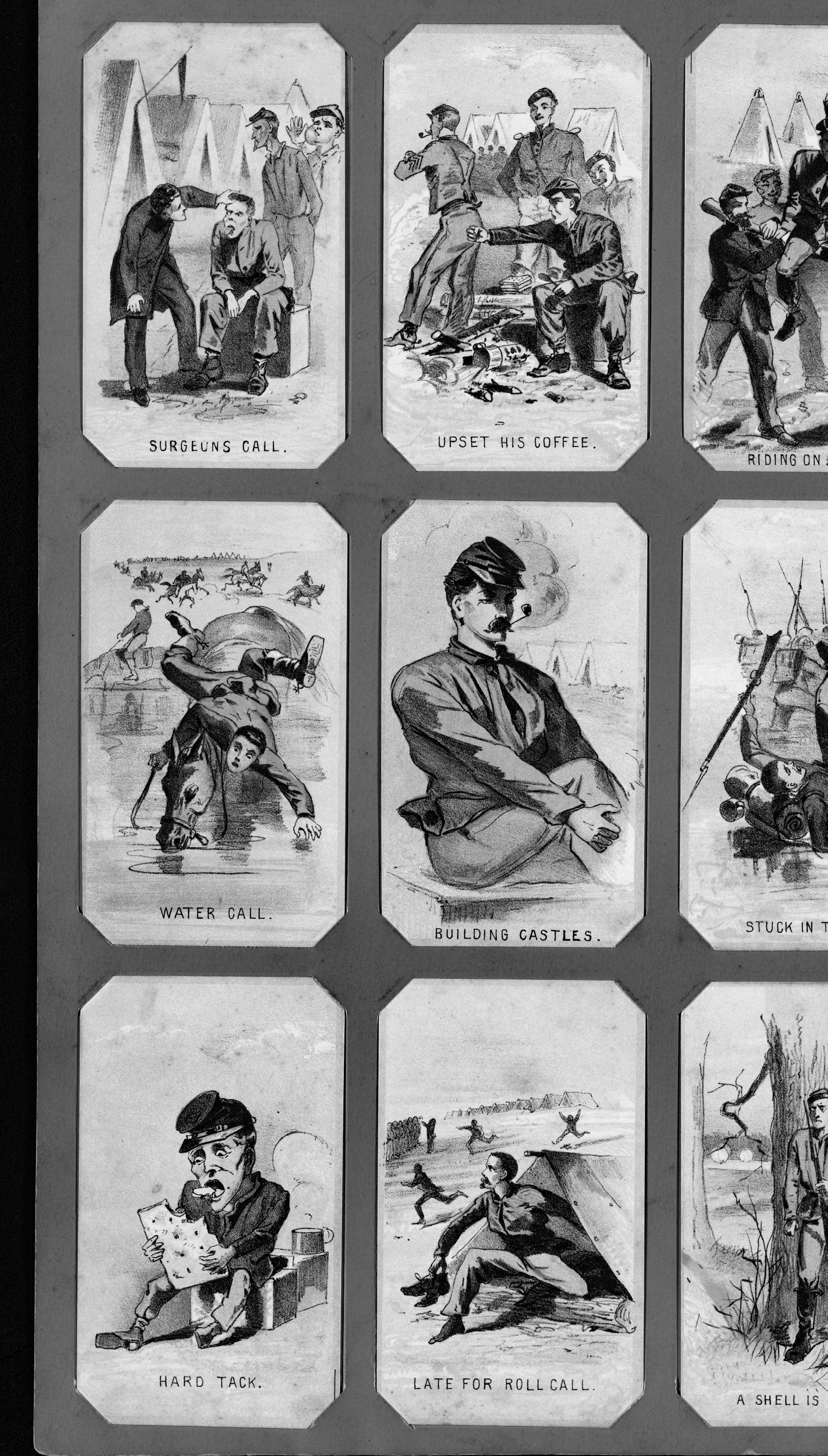

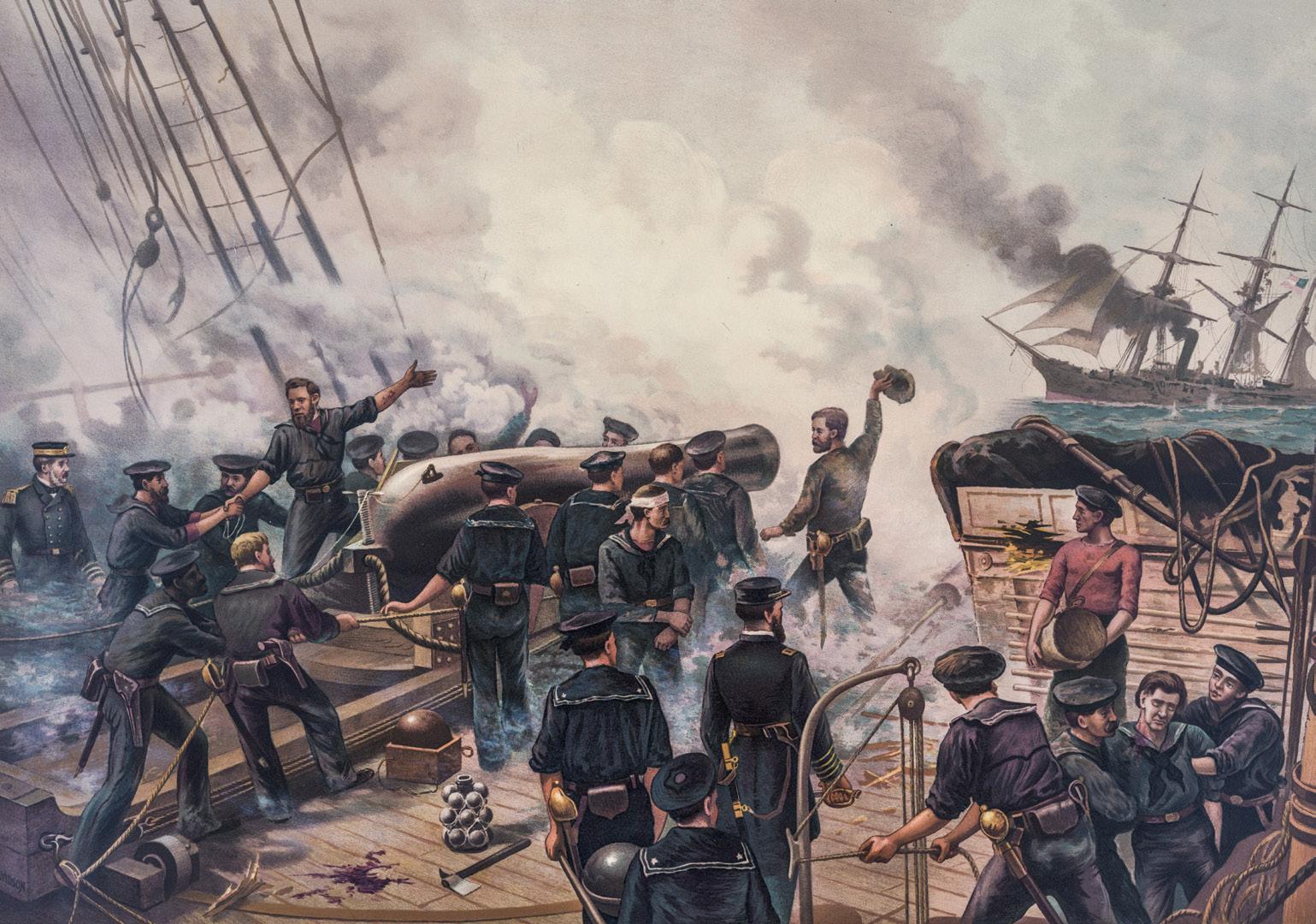

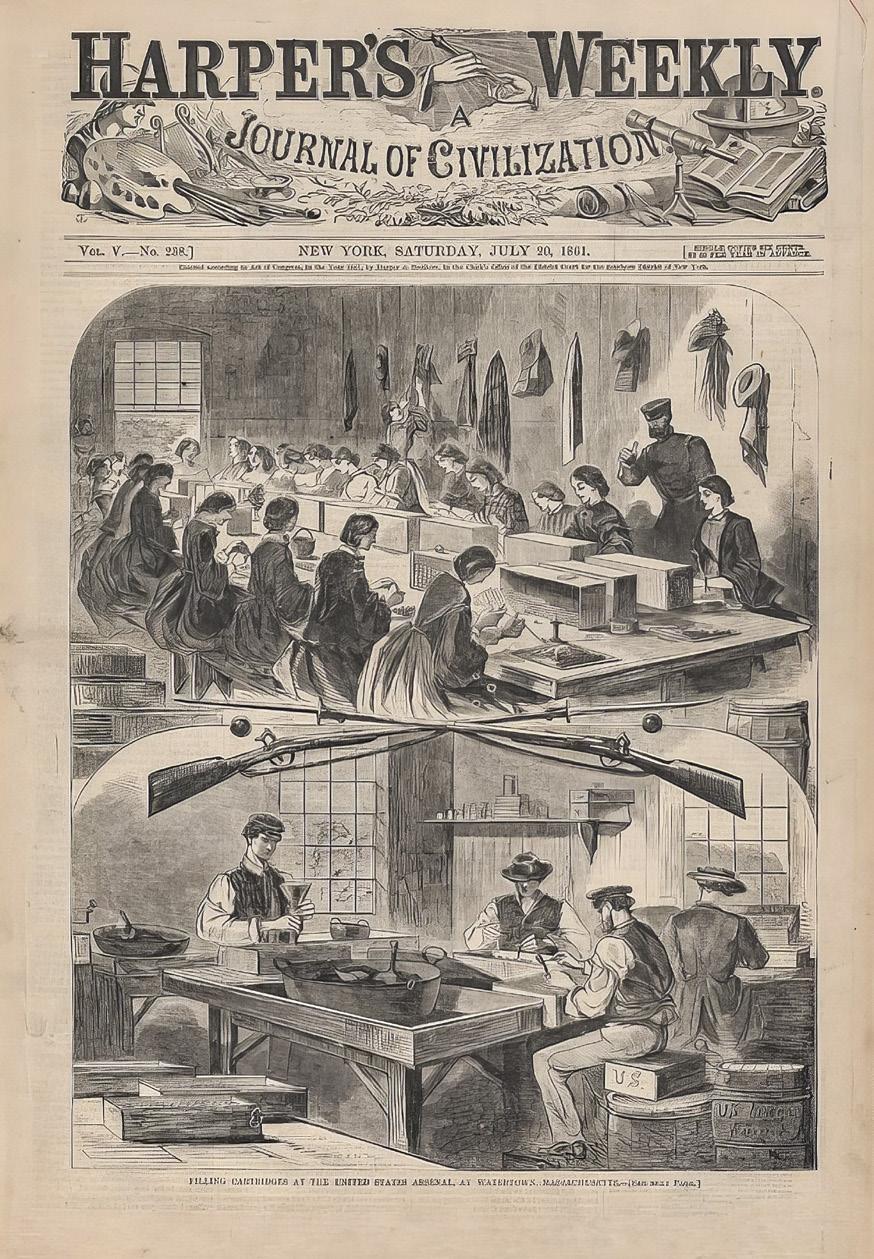

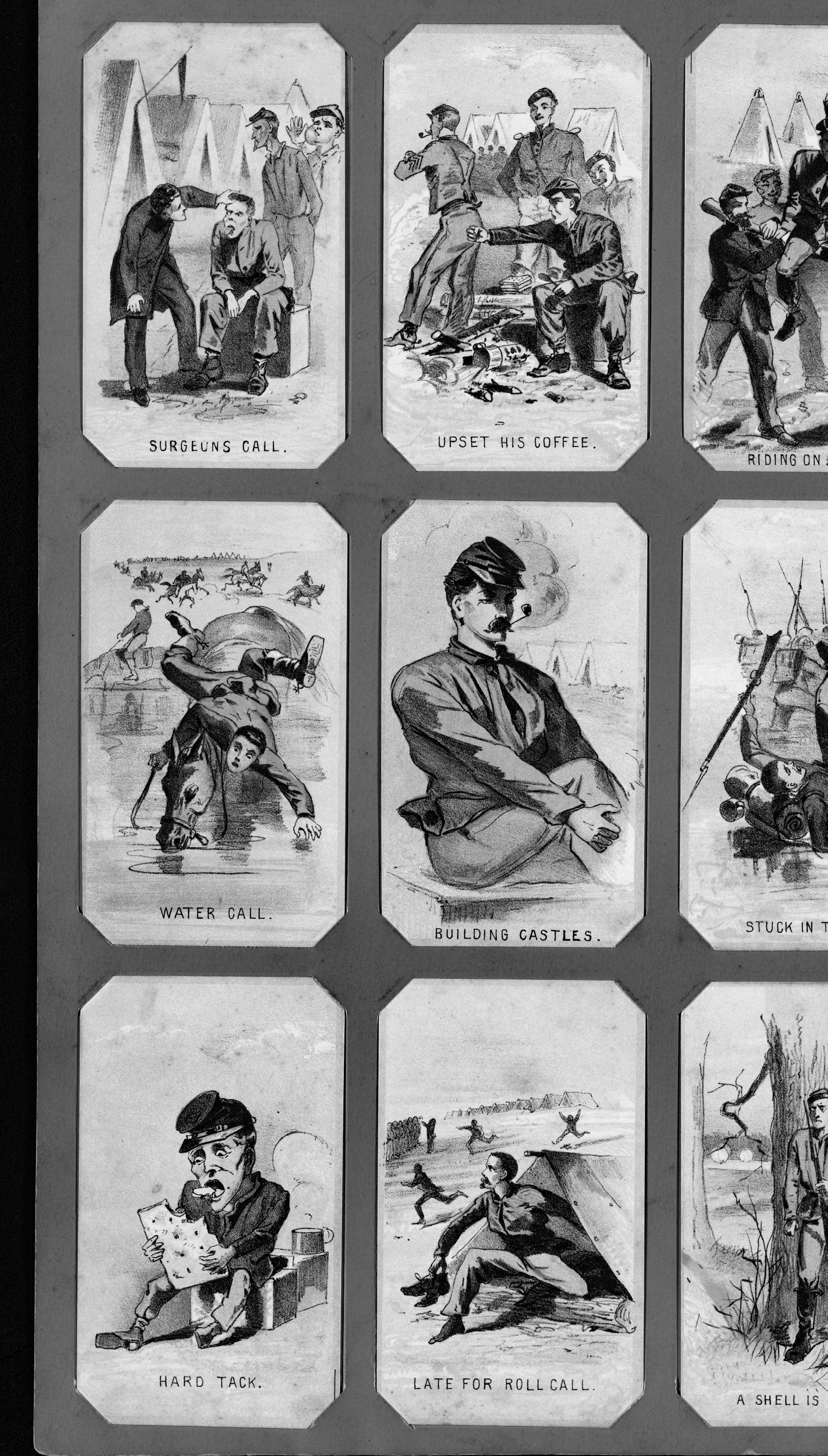

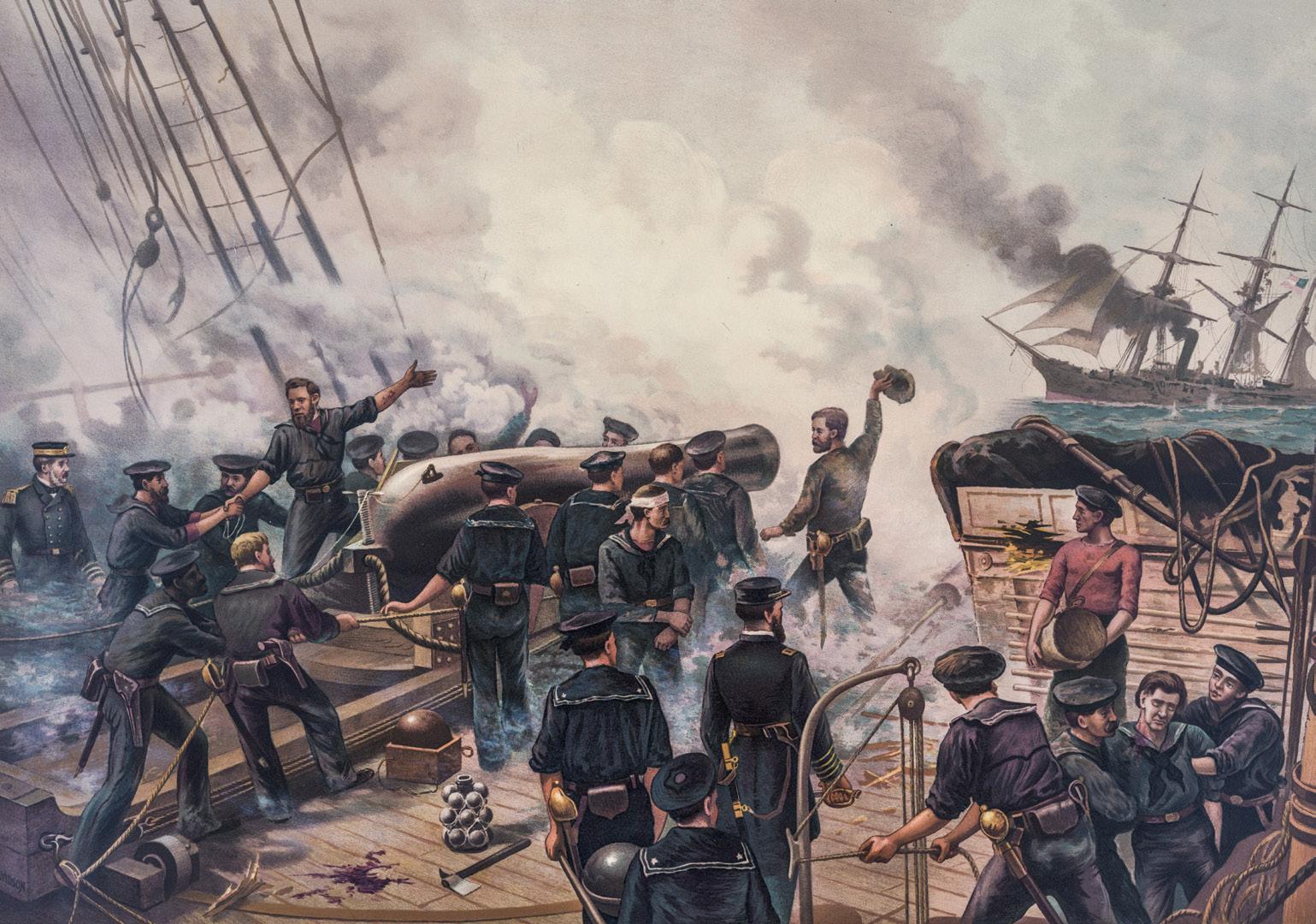

The Graphic War Kimmel & Fors T er p ar T one

By Salvatore Cilella

The Graphic War highlights prints and printmakers from the Civil War discussing their meaning and the printmaker or artist’s goals.

The lithographers Kimmel and Forster, unlike other German American artists of the Civil War era, left very few historical footprints on the national scene. According to their own lithographs, they occupied a business establishment at 254 and 256 Canal Street, New York City. We know Christopher Kimmel “worked as an engraver, lithographer, and printer in New York City with three different partners: Samuel Capewell (1852–1862), Thomas Forster (1865–1870), and Henry E.F. Voigt (1871–1877). By 1878, the partnership of “Kimmel & Voigt” was comprised of Henry Voigt and George Kimmel; the firm was active during the Etching Revival printing etchings for artists.1 During the war, Kimmel listed himself as an engraver in 1863 and in 1864, as a printer. When he partnered with Thomas Forster between 1876 and 1870, the two listed themselves as engravers, lithographers, printers, and colorers [sic].2 “They produced the well-known print The Old Flag Waves over Fort Sumter, as well as prints documenting the installation of the new Atlantic Cable.”3 During the war, Kimmel was associated with publisher Bromley and Company, a New York firm that published

several scandalous anti-Lincoln and anti-abolitionist prints. They appeared in the New York daily The World, which originally supported Lincoln, but then was sold to a consortium of New York Democrats who unabashedly attacked Lincoln.

Despite these attack prints, by 1865, Kimmel had embraced Lincoln and his Emancipation policies. With Forster he published a group of pro-Union, pro-abolitionist, pro-emancipation, allegorical prints laden with patriotic iconography. Two particularly significant prints bookended the war. They were both produced sometime in the years immediately after Lee’s surrender, ca. 1866-67.

Although early colonists popularized Uncle Sam and Yankee Doodle, the feminist depictions of liberty and freedom have been the “most appealing,” according to historian David Hackett Fischer. Fischer writes that they “descended from the ancient goddess of liberty, a timeless figure who represented an idea that derived its authority . . . from eternal truth. In the early American republic, they became something different—a symbol of modernity, endlessly redefined by the whirl of contemporary fashion—

14 Civil War News Magazine | May-June 2024

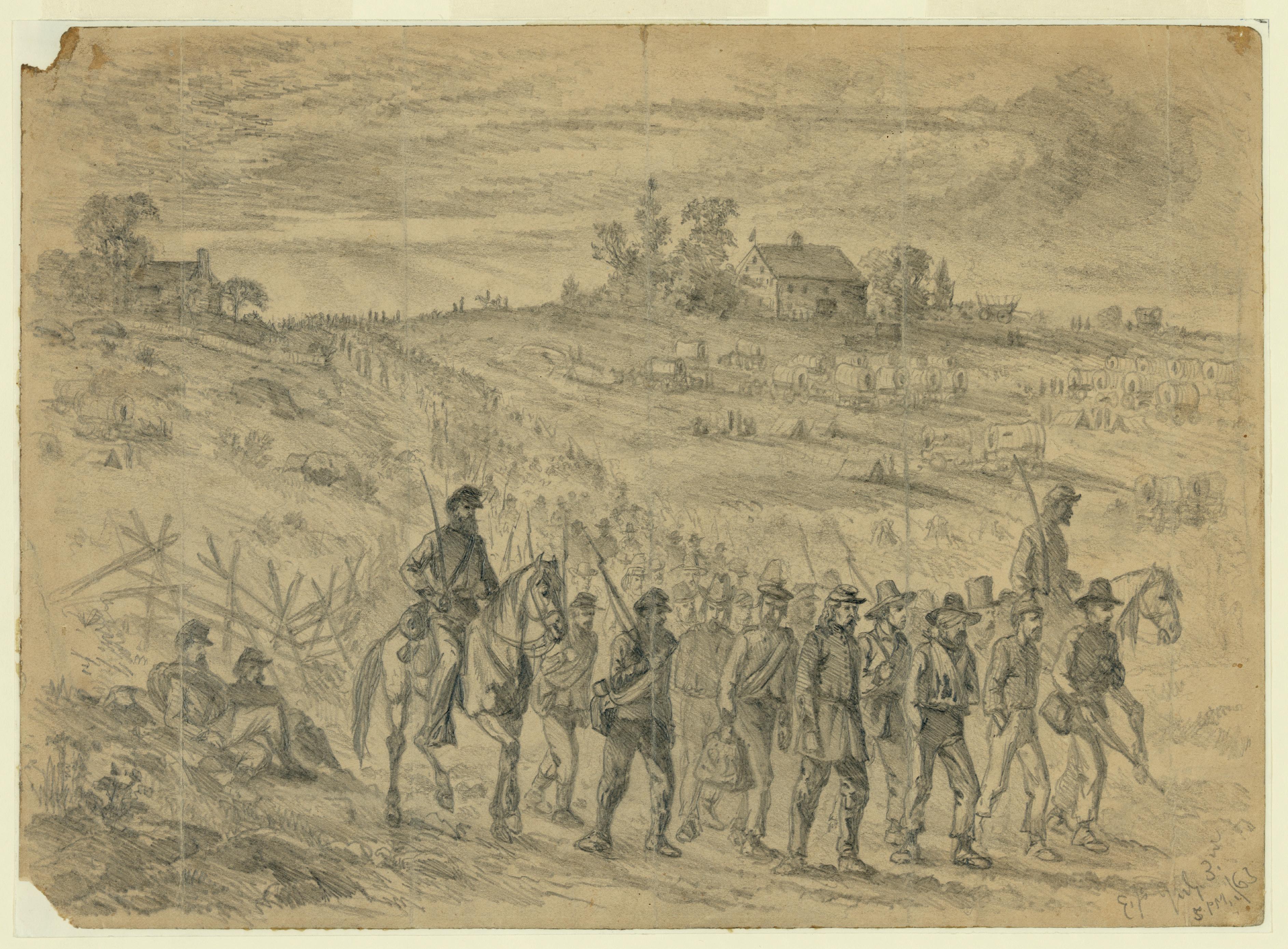

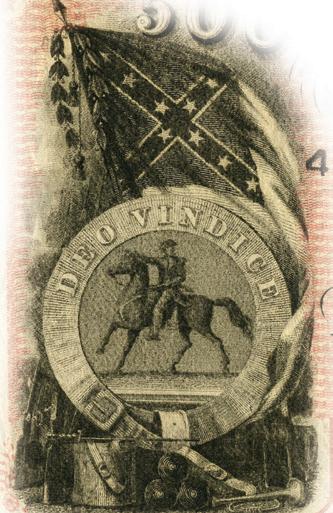

The Outbreak of the Rebellion in the United States, 1861. (Library of Congress)

and they gained new meaning from their relevance to the present.”4

Both prints were published as uncolored, black and white, large folio lithographs. The first was entitled The Outbreak of the Rebellion in the United States 1861 and dated 1865. The entire image is split evenly between the “good” of Union and the “evils” of secession. Centering the tableau is the Goddess Liberty, or Columbia, wearing the French revolutionary Phrygian cap with a laurel wreath. In her left hand is a pole holding the American flag. She is surmounted by the American eagle. On her left, (the viewer’s right), stands Lincoln addressing his audience. Behind his outreached left arm is General Winfield Scott in uniform. Below, “various figures exemplifying the generosity and suffering of the Northern citizenry” pour out their donations to keep the Northern war machine running smoothly. Below Lincoln’s feet is a widow (presumably) grieving with her two children. In the right background, over scenes of war, a bright sun rises above the mountains.

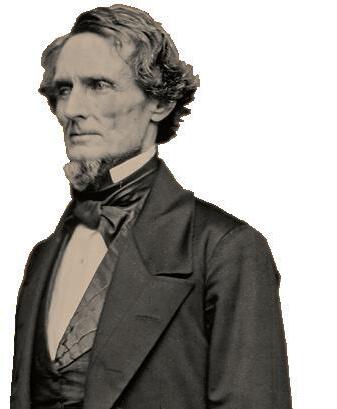

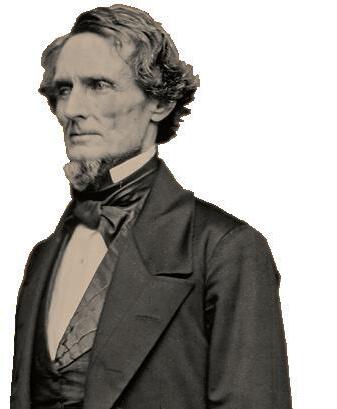

On the print’s left, the figure of Justice has dropped her blindfold and holds the scales of justice in her left hand and a sword in her right. Asleep at his post is President James Buchanan while his Secretary of War, John B. Floyd, “who was accused of misappropriation of government funds,” is shown raking coins into a bag. Confederate President Jefferson Davis is depicted below a palm tree, a symbol of South Carolina, where the rebellion began. Wrapped around the tree is the venomous snake of secession. In the left background, in contrast, is a depiction of Fort Sumter

and nothing but ominous clouds hovering over all.

The following year, 1866, Kimmel and Forster issued a sequel they entitled, The Outbreak of the Rebellion in the United States. This time the vanquished Rebel army is depicted on the right side of the print, below a bowing, bending, palmetto tree. Jefferson Davis holds a sack of money as Robert E. Lee offers his sword in surrender. John Wilkes Booth is center right.

Three women are central to this tableau. On a pedestal, Liberty is right center with her revolutionary Phrygian hat next to Columbia with stars in her crown. Below them is Justice with her sword and scales. Carved into the pedestal are likenesses of Lincoln and Washington. On the left is the new President, Andrew Johnson. Behind him, Ulysses S. Grant is seen on horseback leading the victorious Union troops. American flags are in abundance and the vanquished Confederate symbols are nowhere to be seen.

More striking and importantly, the artists have included two black figures; one armed and in the Union uniform, the other, in civilian clothes, a freed slave.

With this print, Kimmel and Forster had made it “clear that in war and iconography, African Americans had . . . raised themselves from shackled slaves to freedom fighters.” As Harold Holzer et. al., have written, this crowded assemblage has “cast . . . (its) . . . gaze squarely on the two African Americans” featured prominently in the foreground. As in the 1861 version, the American eagle flies majestically over the entire scene as Liberty holds the large American flag.5

The End of the Rebellion in the United States, 1865. (Library of Congress)

Endnotes

1 American Historical Print Collectors Society, https://ahpcs.org/publisher/kimmel-forster.

2 Print authority David McNeely Stauffer, in his basic reference work on American Engravers, “incorrectly identifies a P.K. Kimmel as a ‘New York engraver of vignettes and portraits, working about 1850, and was later a member of the engraving firm of Capewell & Kimmel, of the same city. There was also an engraving firm of Kimmel & Foster [sic].’ This appears to merge information about New York engraver Frederick K. Kimmel and Christopher Kimmel.’” As cited on American Historical Print Collectors website, Stauffer, American Engravers Upon Copper and Steel, I, 153. Peters, in his America on Stone, (251) repeats the same misinformation.

3 Jay T. Last, The Color Explosion: Nineteenth Century American Lithography Hillcrest Press, 2006, p. 174.

4 David Hackett Fischer, Liberty and Freedom: A Visual History of America’s Founding Ideas. Oxford; Oxford University Press, 2005, p. 233.

5 Holzer, et. al., The Union Image, University of North Carolina Press, pp. 200, 235.

a fter 43 years in the MU se UM fie L d , CiLeLLa devotes his tiMe to CoLLeCting aMeriCan prints and Maps and writing. he has written extensiveLy on e M ory u p Ton : u p Ton ’ s r egulars : a h is Tory of T he 121 s T n e W y ork v olun T eers in T he c ivil W ar (kansas, 2009); a twovo LUM e c orrespondence of M ajor g eneral e M ory u p T on , ( t ennessee , 2017), re C eived the 2017–2018 a M eri C an C ivi L w ar M U se UM ’ s f o U nders a ward for o U tstanding editing of pri M ary so U r C e M ateria L s . he edited Upton’s Love Letters 186870 to his wife–Till deaTh do us parT ( o k L aho M a , 2020), and T he M e M oirs of deWiTT clinTon beckWiTh of upTon’s regulars (MCfarLand, 2023).

Subscribe and join our thousands of readers at

https://tinyurl.com/277vpke9

https://historicalpublicationsllc.com/site/subscription_services.html

16 Civil War News Magazine | May-June 2024

Promoters of Quality Shows for Shooters, Collectors, Civil War and Militaria Enthusiasts Mike Kent and Associates, LLC • PO Box 685 • Monroe, GA 30655 (770) 630-7296 • Mike@MKShows.com • MKShows.com l l December 7 & 8, 2024 Middle TN (Franklin) Civil War Show Subscribe online at

2024 Richard Barksdale

Harwell Award

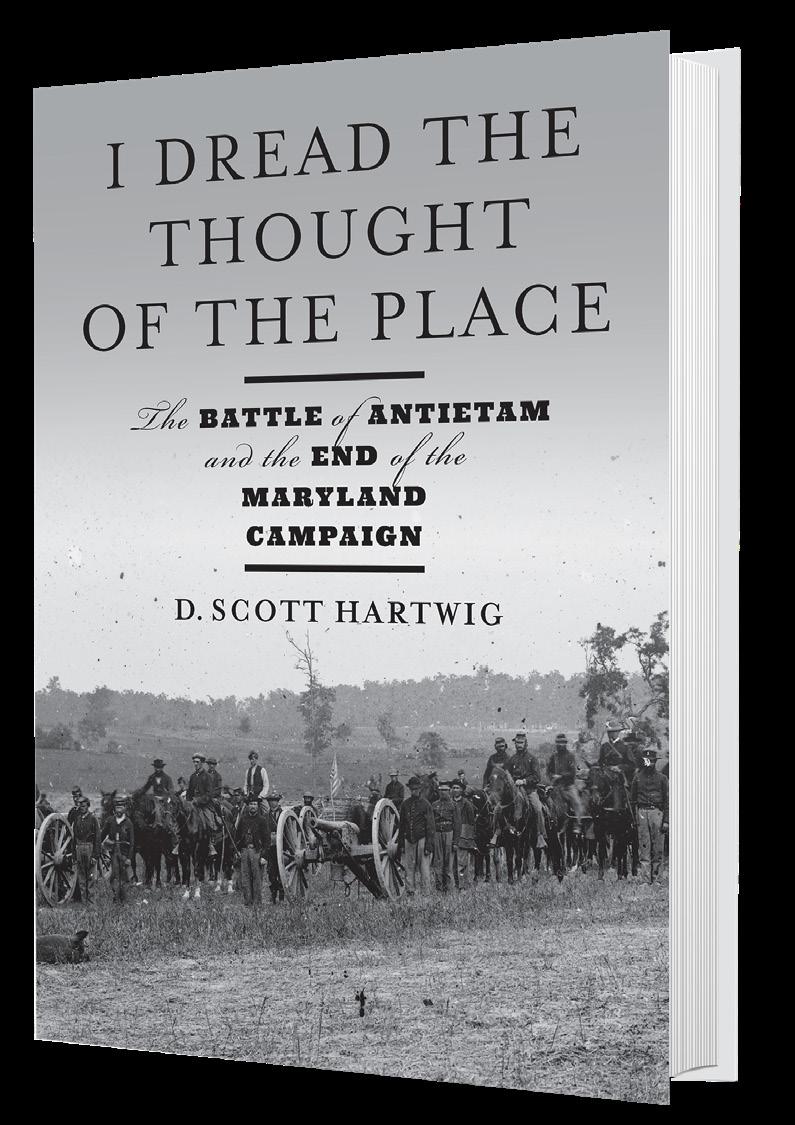

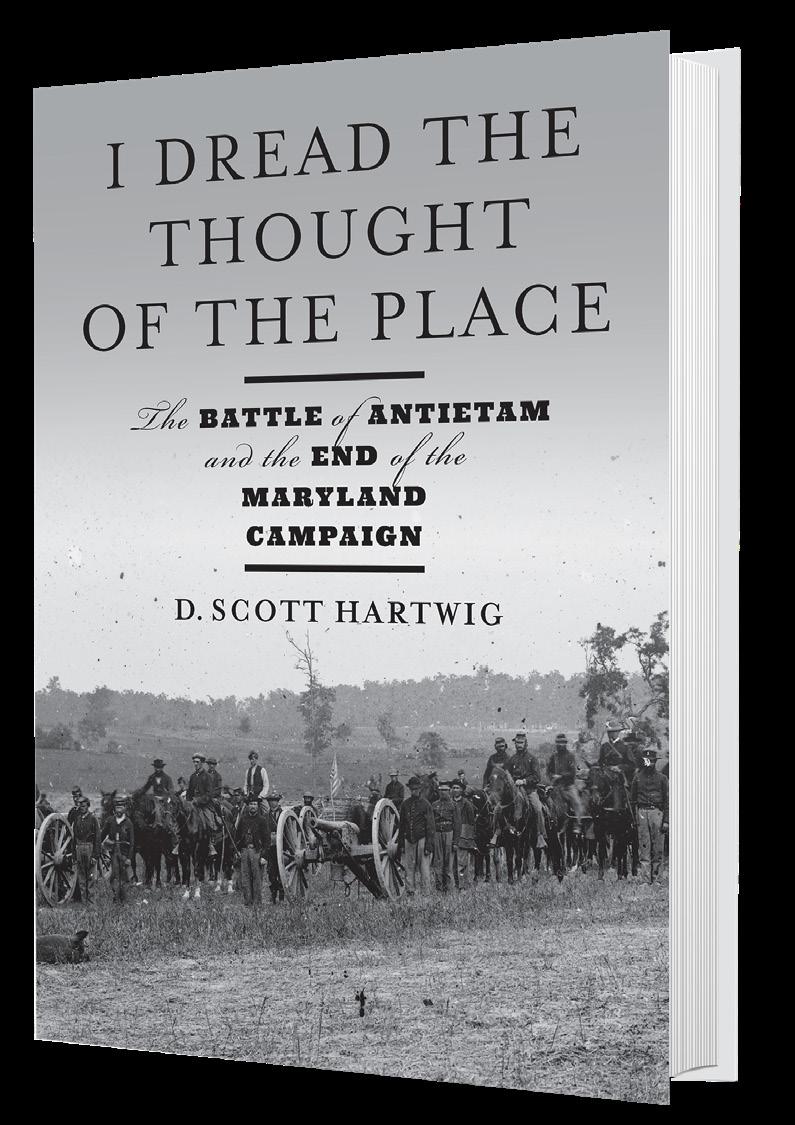

D. Scott Hartwig to Receive 37th Annual Award

The Atlanta Civil War Round Table is pleased to announce that it has chosen D. Scott Hartwig as the winner of the 2024 Richard Barksdale Harwell Award for his I Dread the Thought of the Place: The Battle of Antietam and the End of the Maryland Campaign. The Round Table annually presents the Harwell Award for the best book on a Civil War subject published in the previous year.

“Hartwig’s fine book is the first major study of the Battle of Antietam/Sharpsburg since 1983,” said Gary Barnes, Chairman of the Round Table’s Harwell Award Committee.” Barnes added that he and the other members of the committee are confident that the awardwinning book “will be considered the definitive study of this important battle.”

Hartwig was the supervisory park historian at the Gettysburg National Military Park for twenty years. He previously authored To Antietam Creek: The Maryland Campaign of September 1862

I Dread the Thought of the Place was published by the Johns Hopkins University Press.

The Round Table has presented this prize each year since 1989. Recent recipients include Jeffry Wert, Charles Knight, Caroline Janney, Stephen Davis, Hampton Newsome, and Wilson Greene.

The Round Table is now accepting nominations for the 38th award, which will be presented in 2025. Nominations must be received by December 31, 2024.

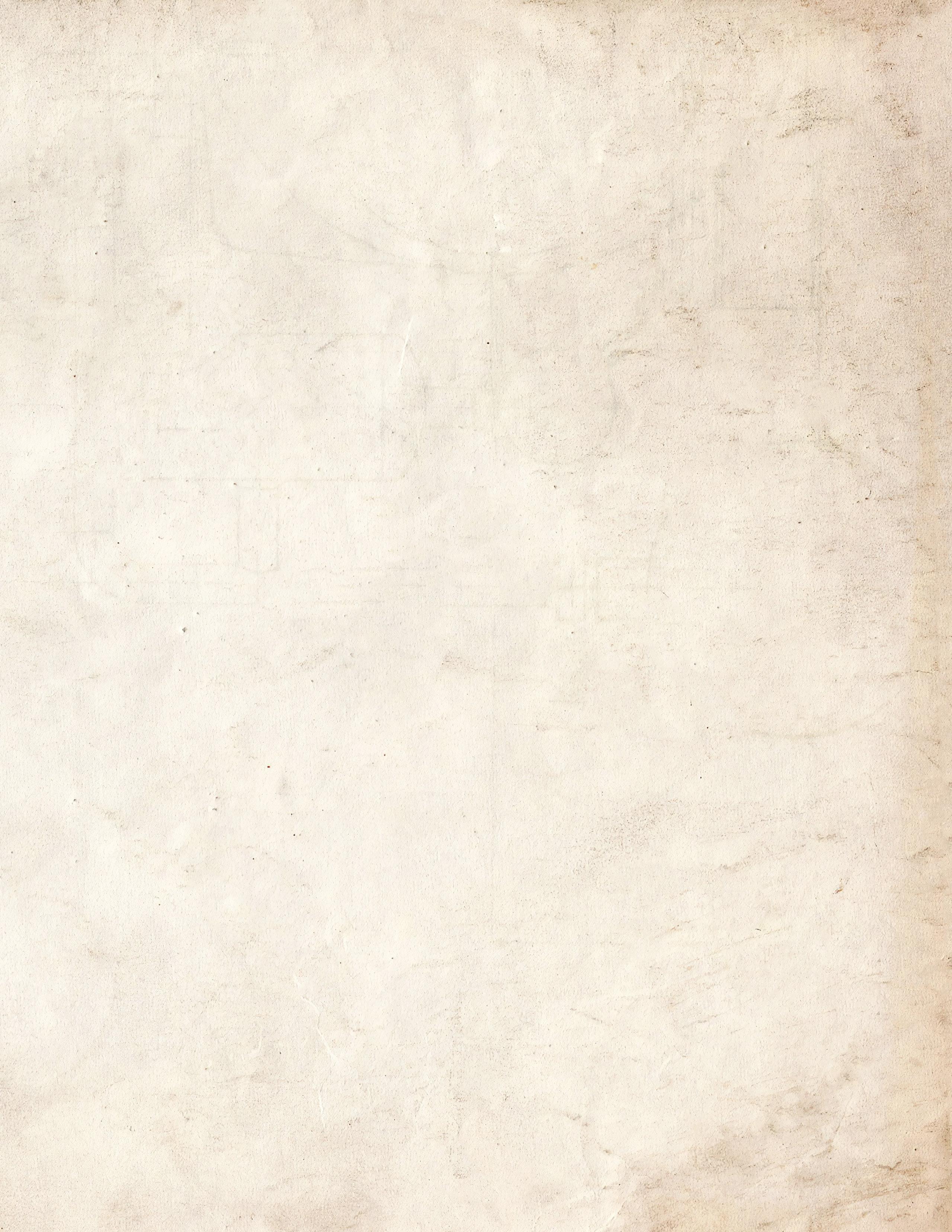

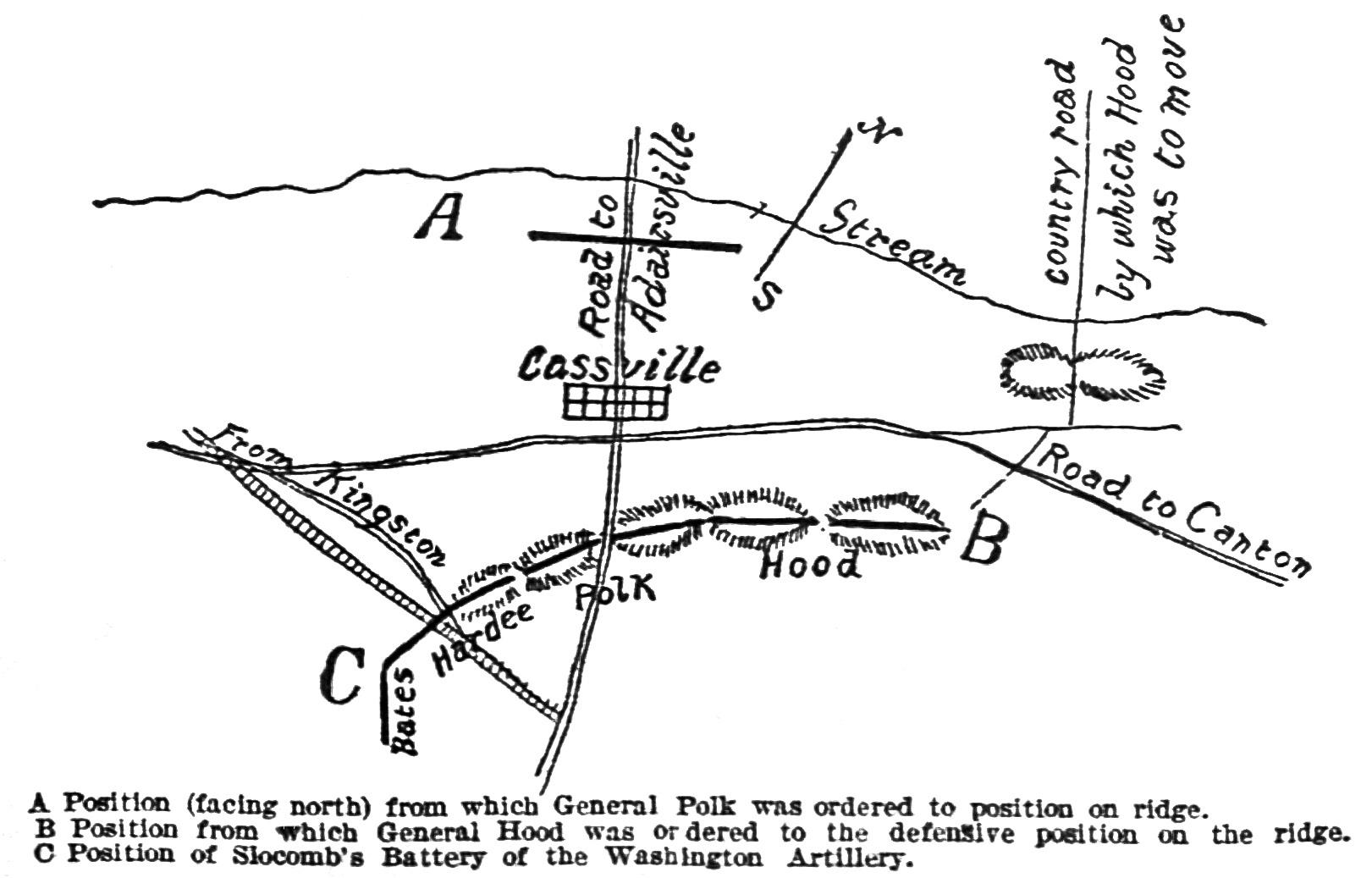

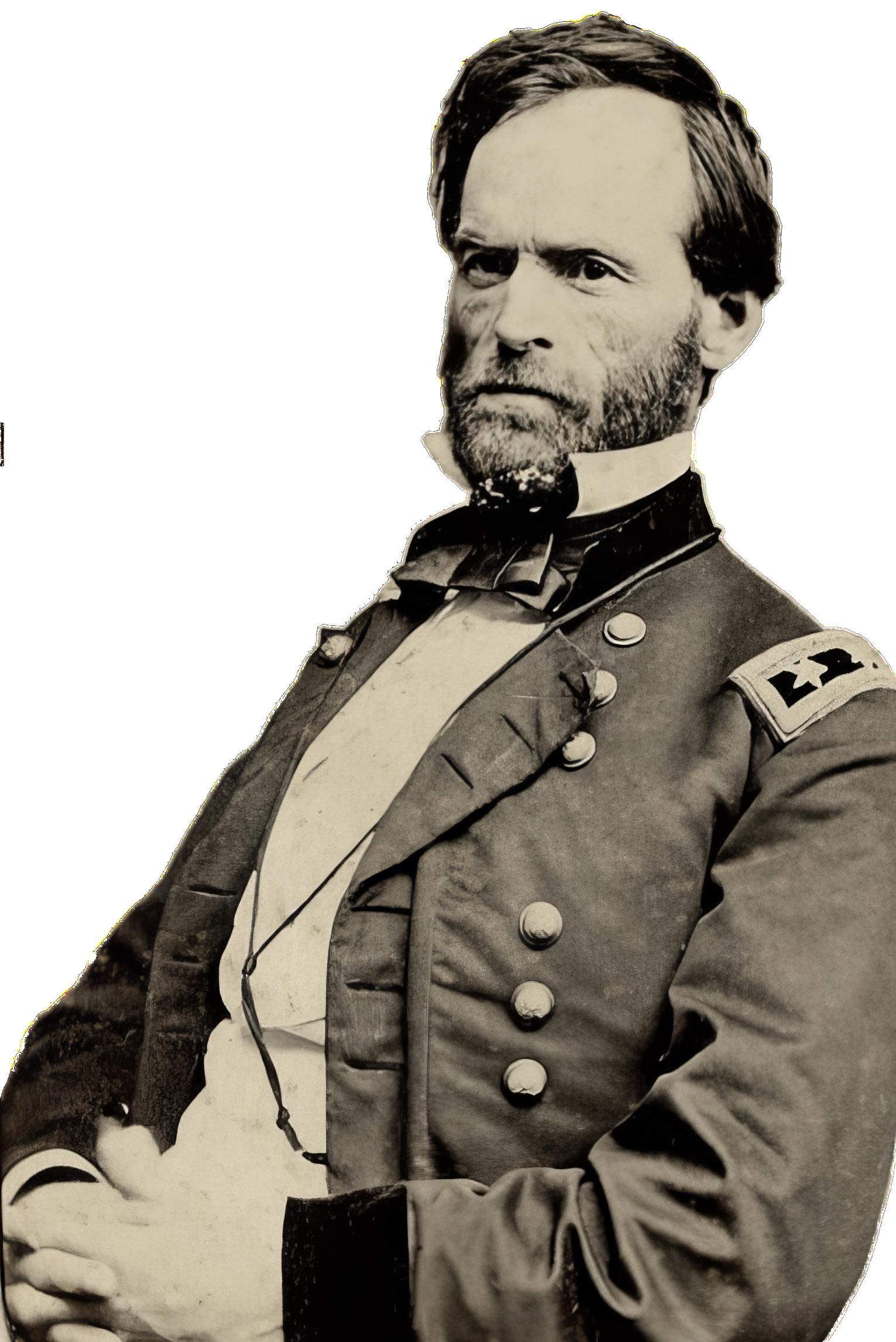

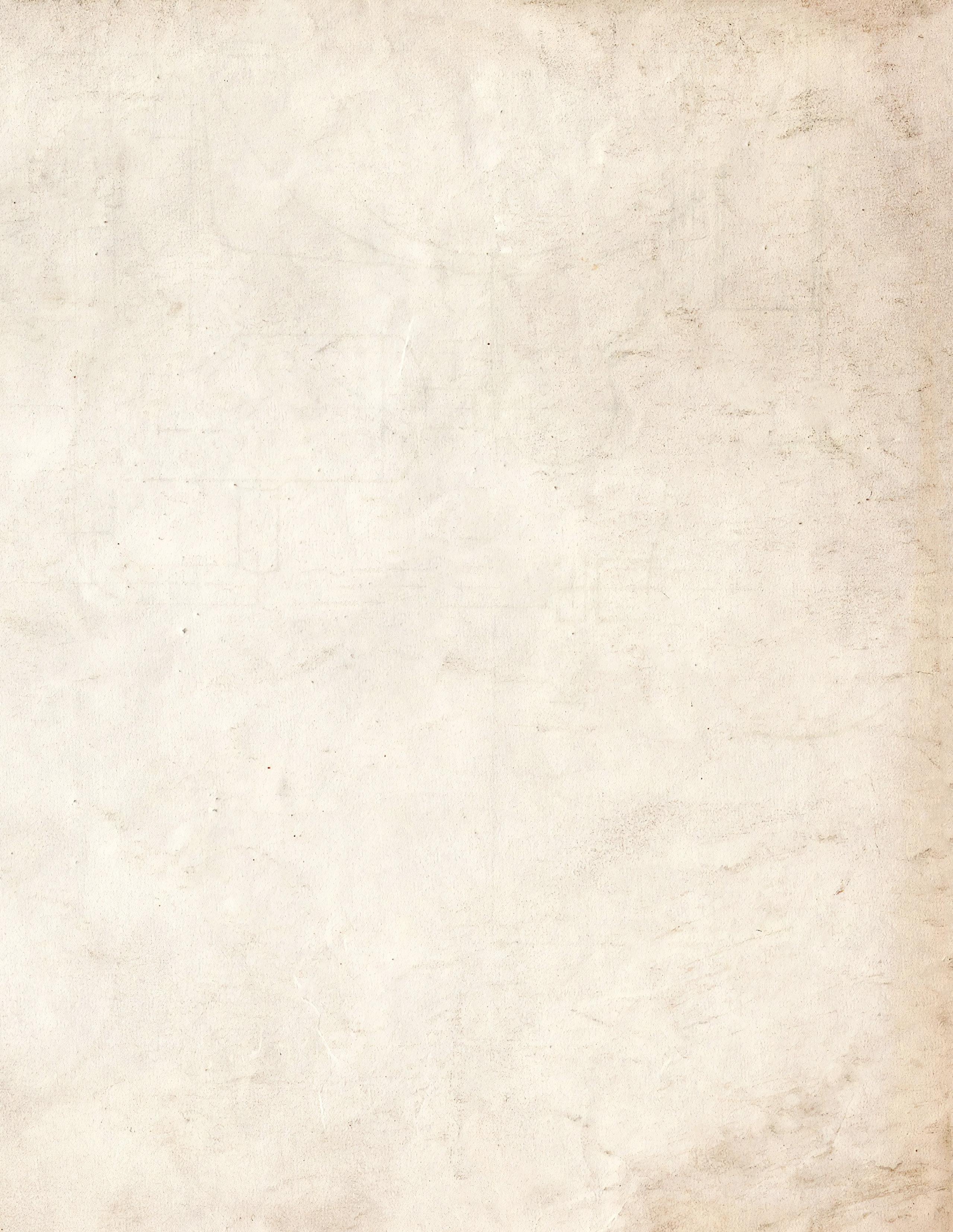

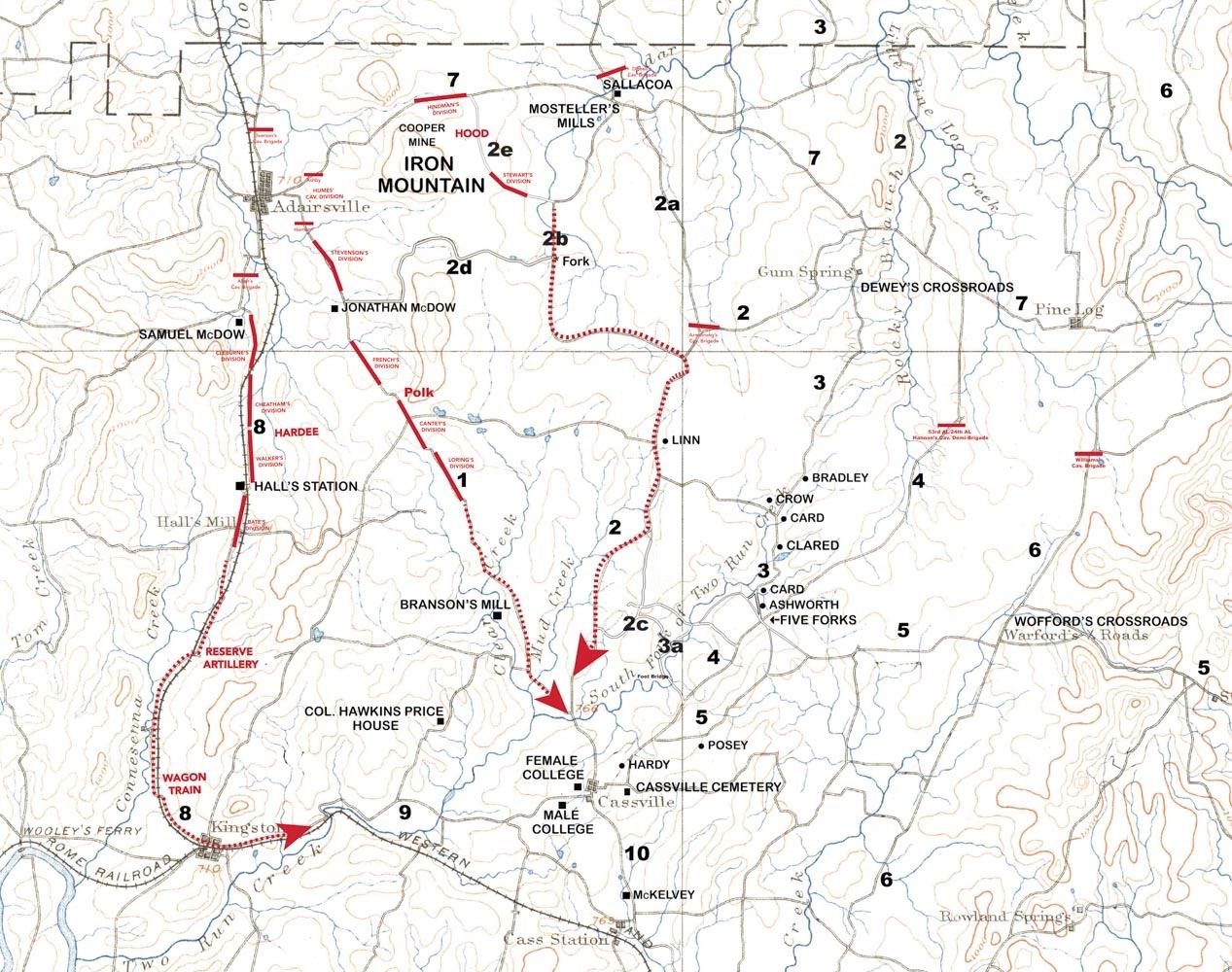

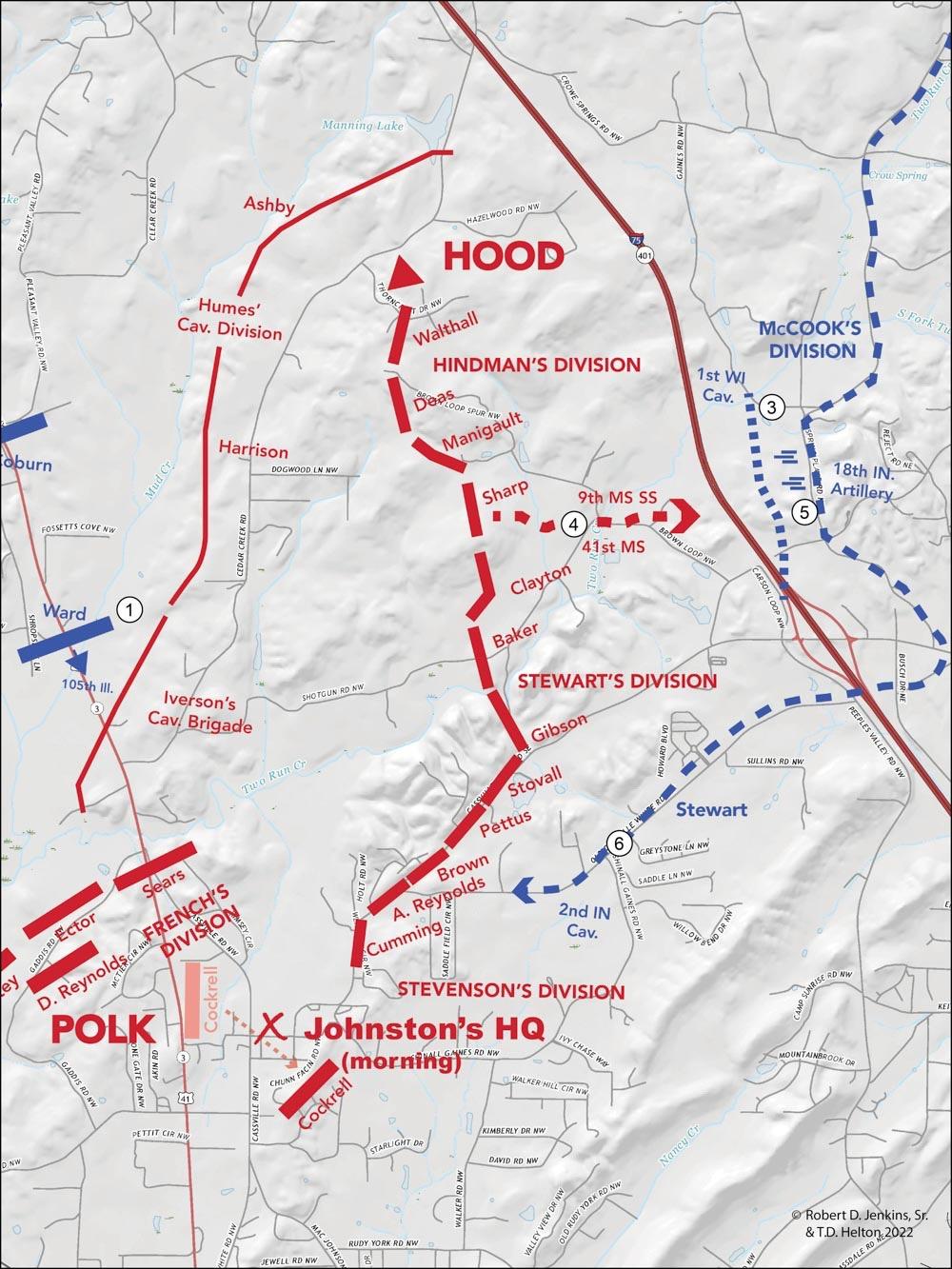

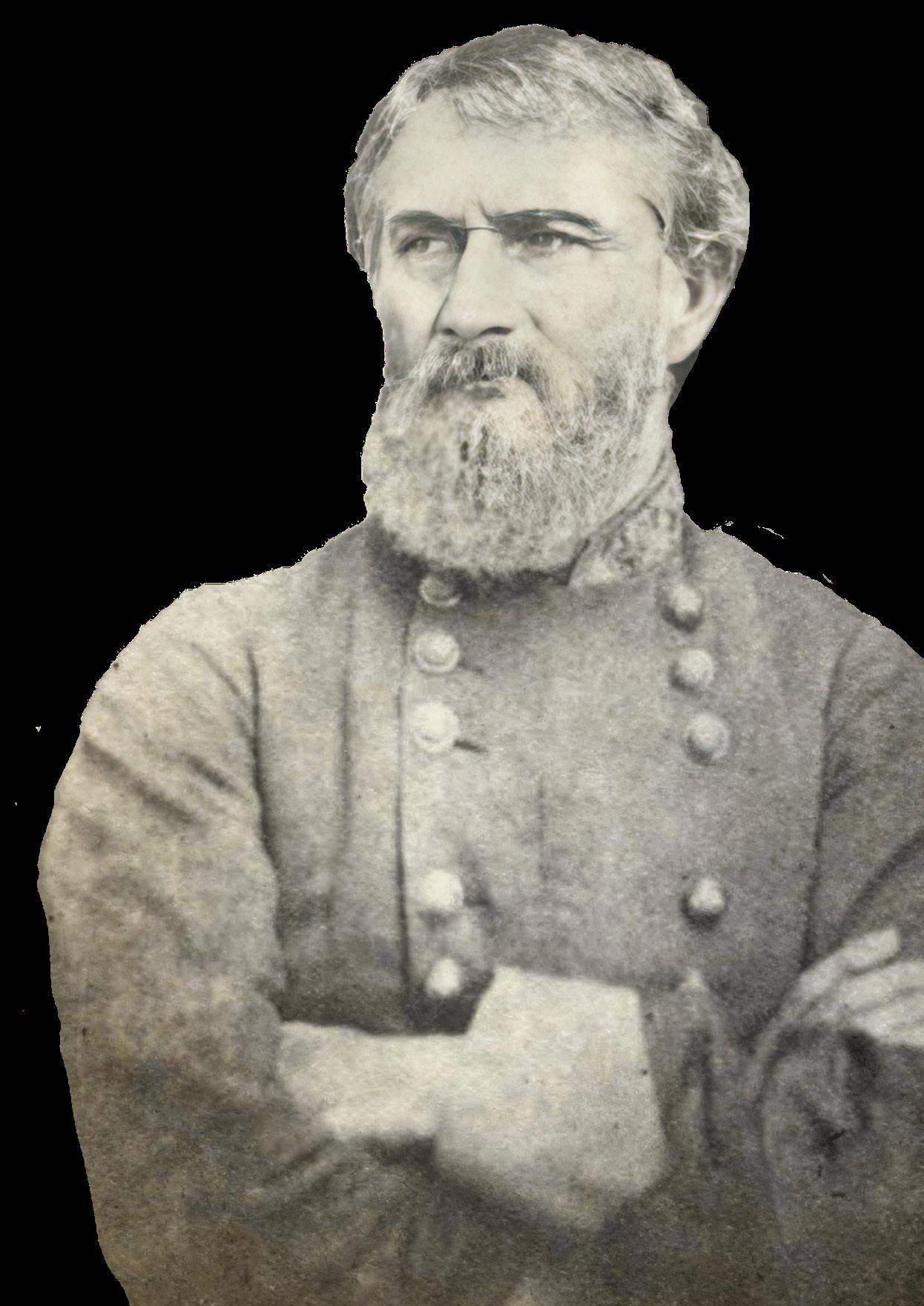

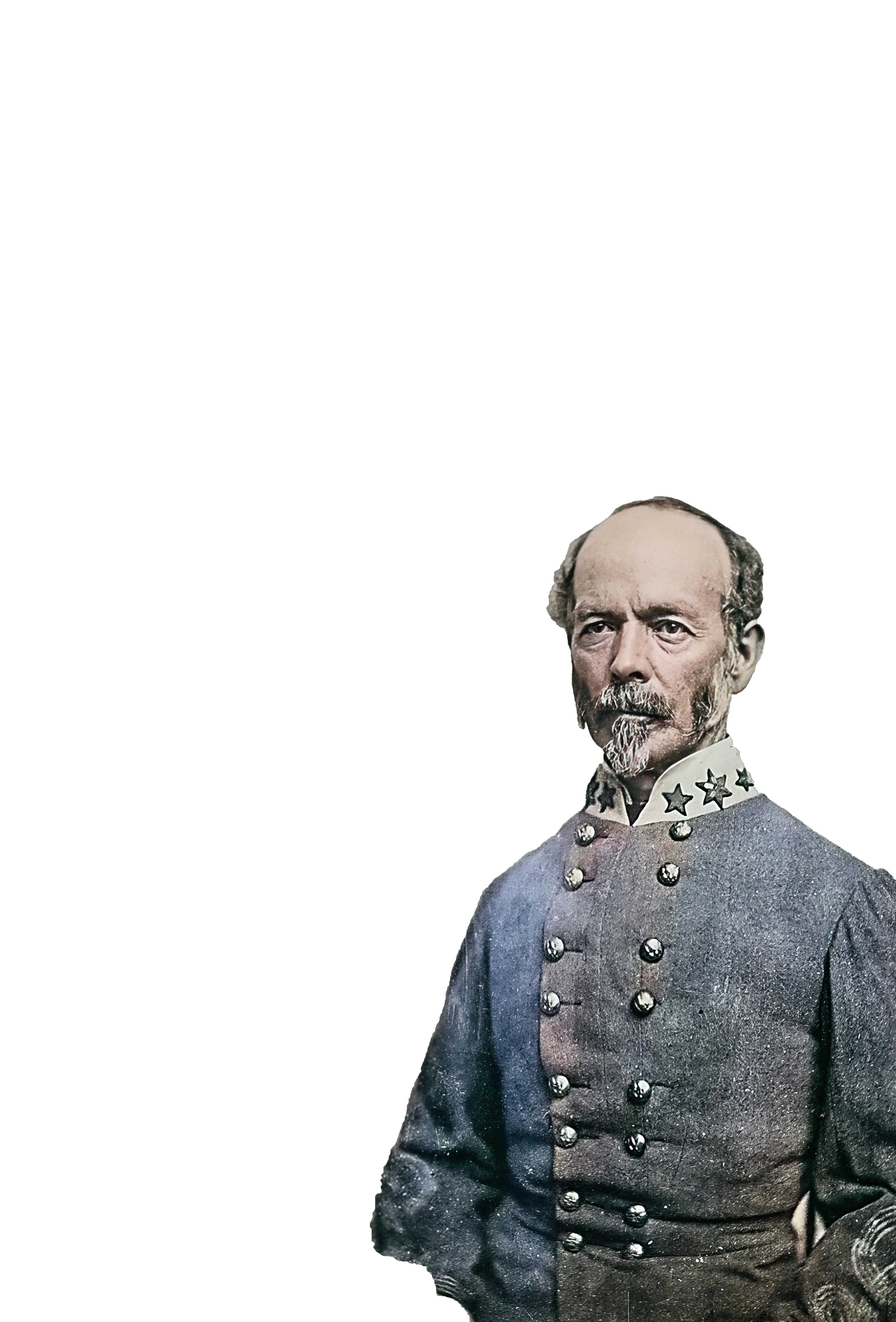

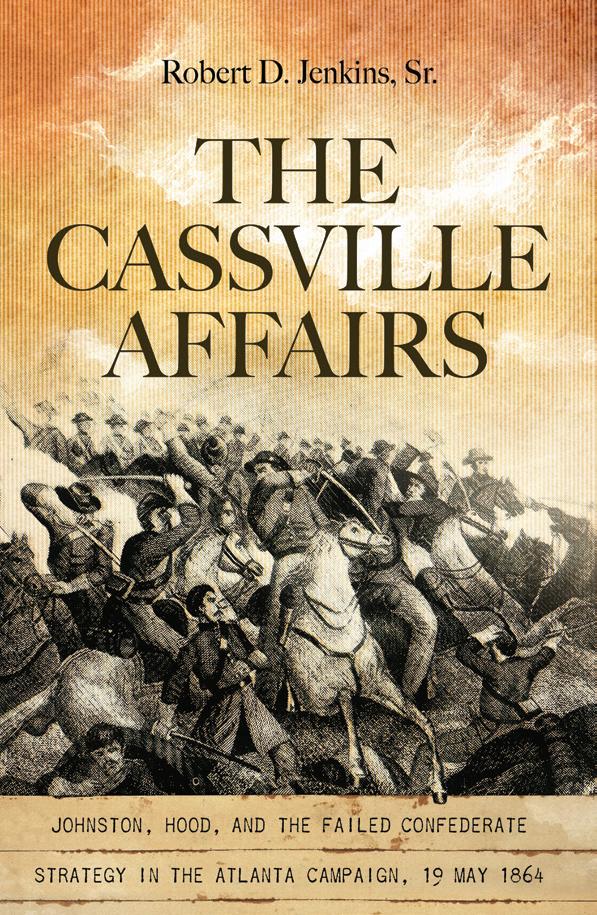

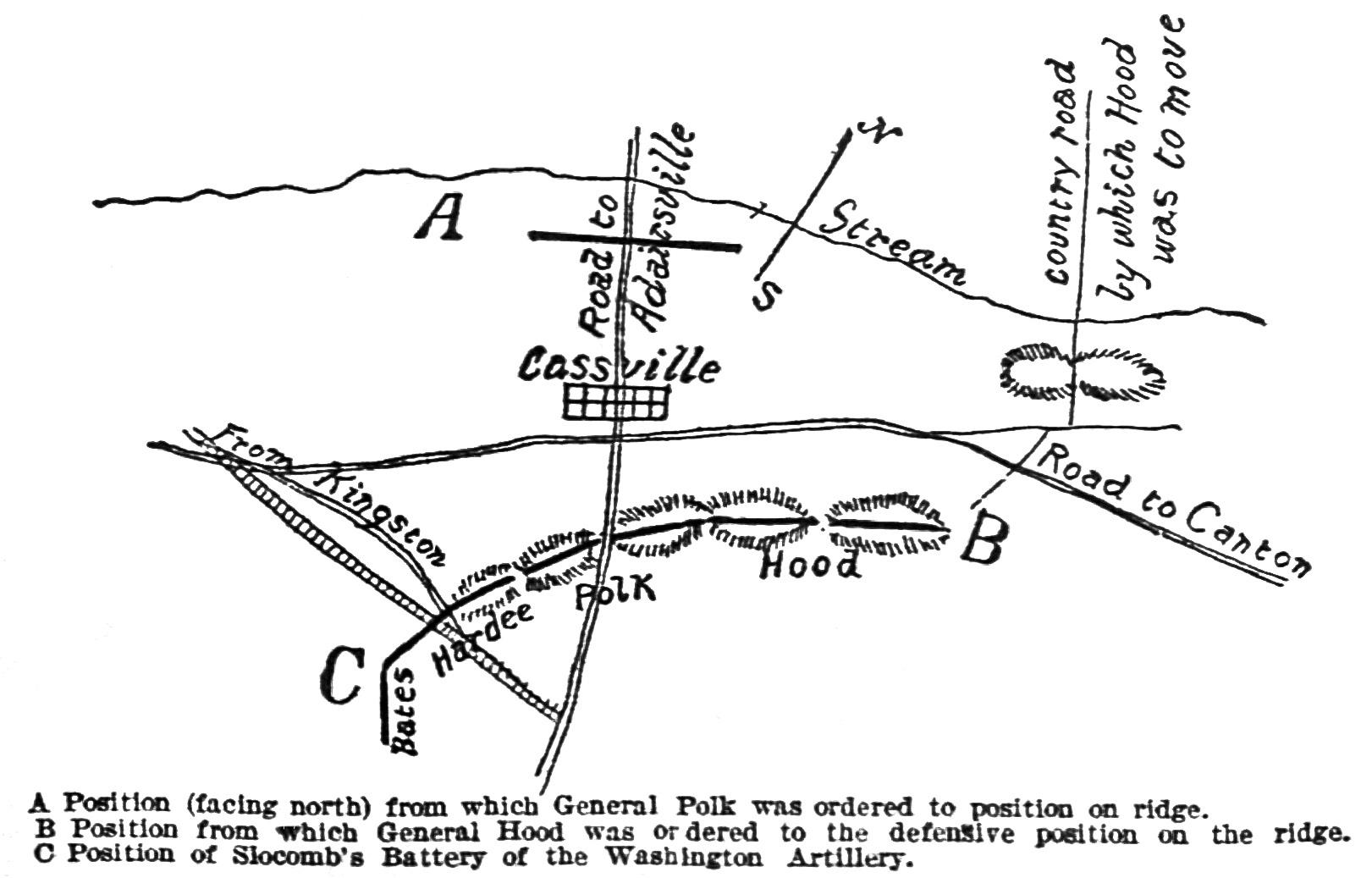

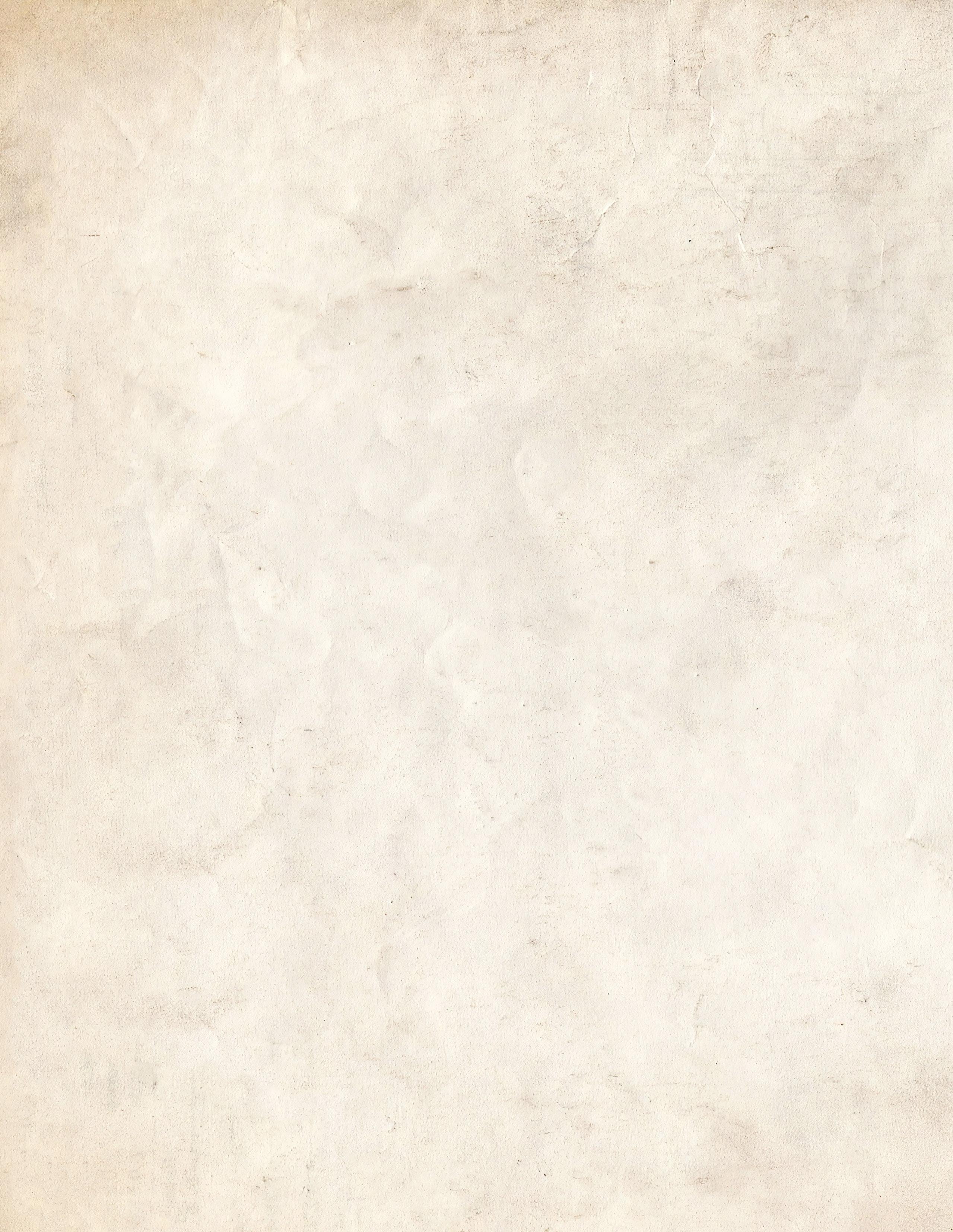

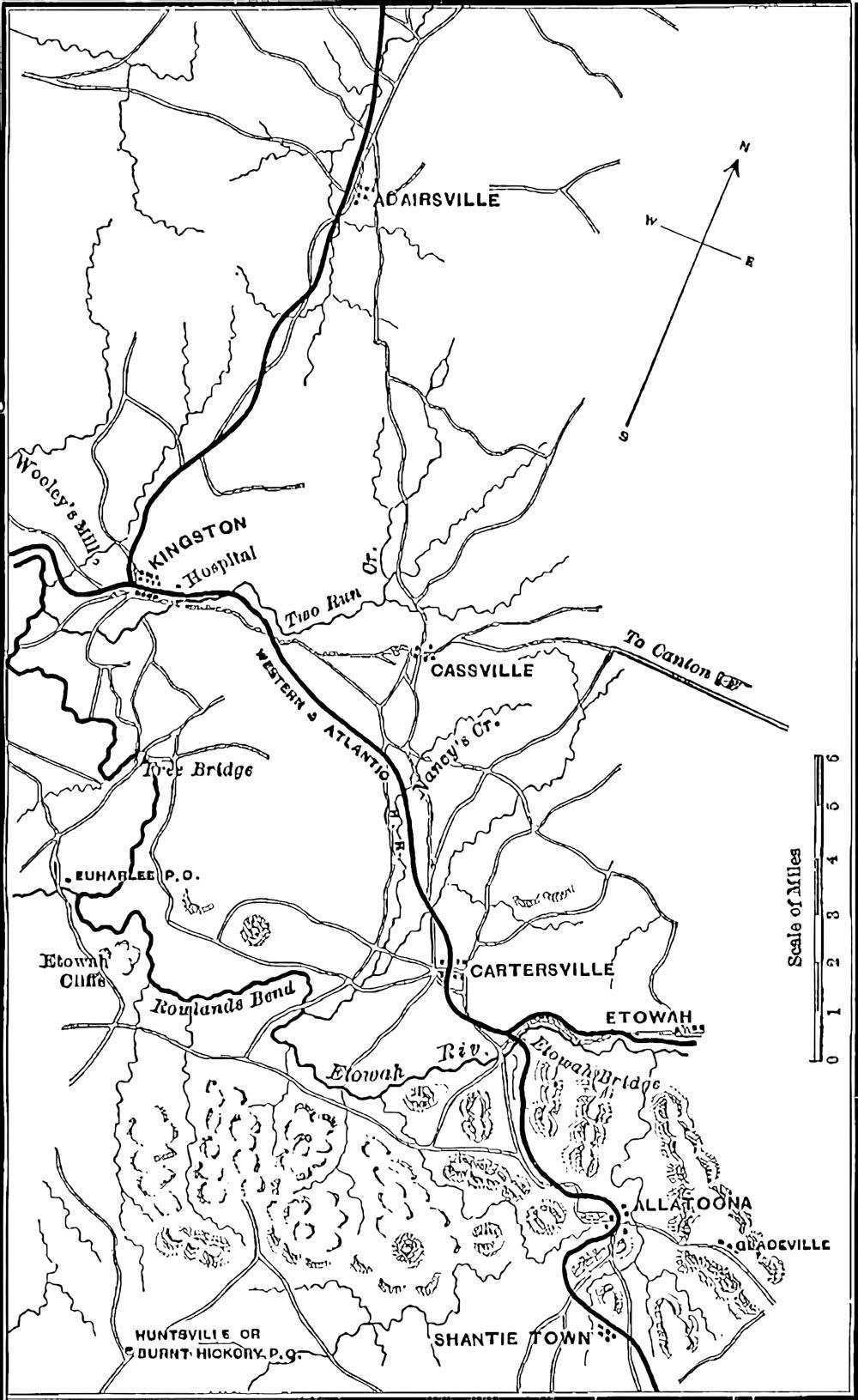

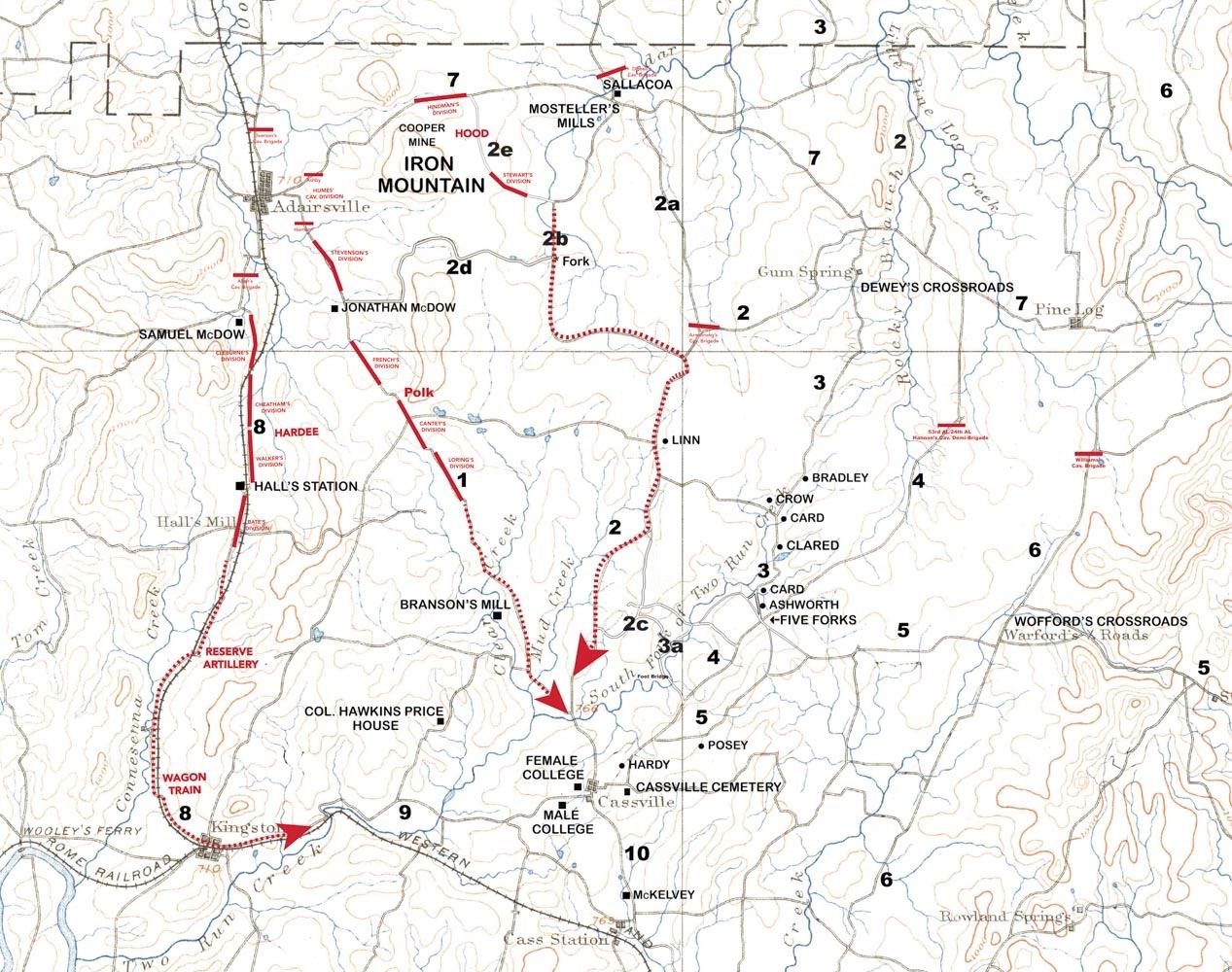

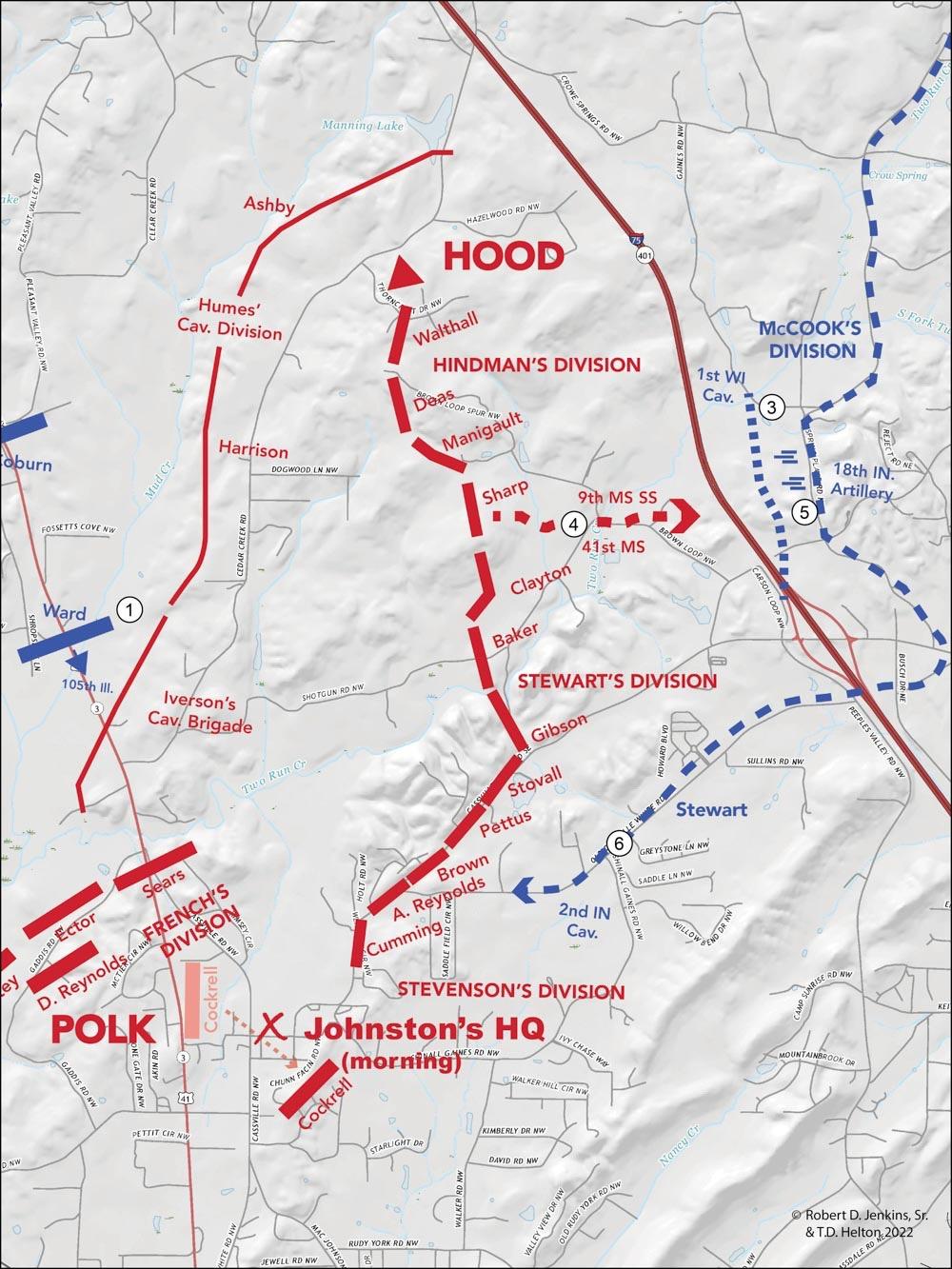

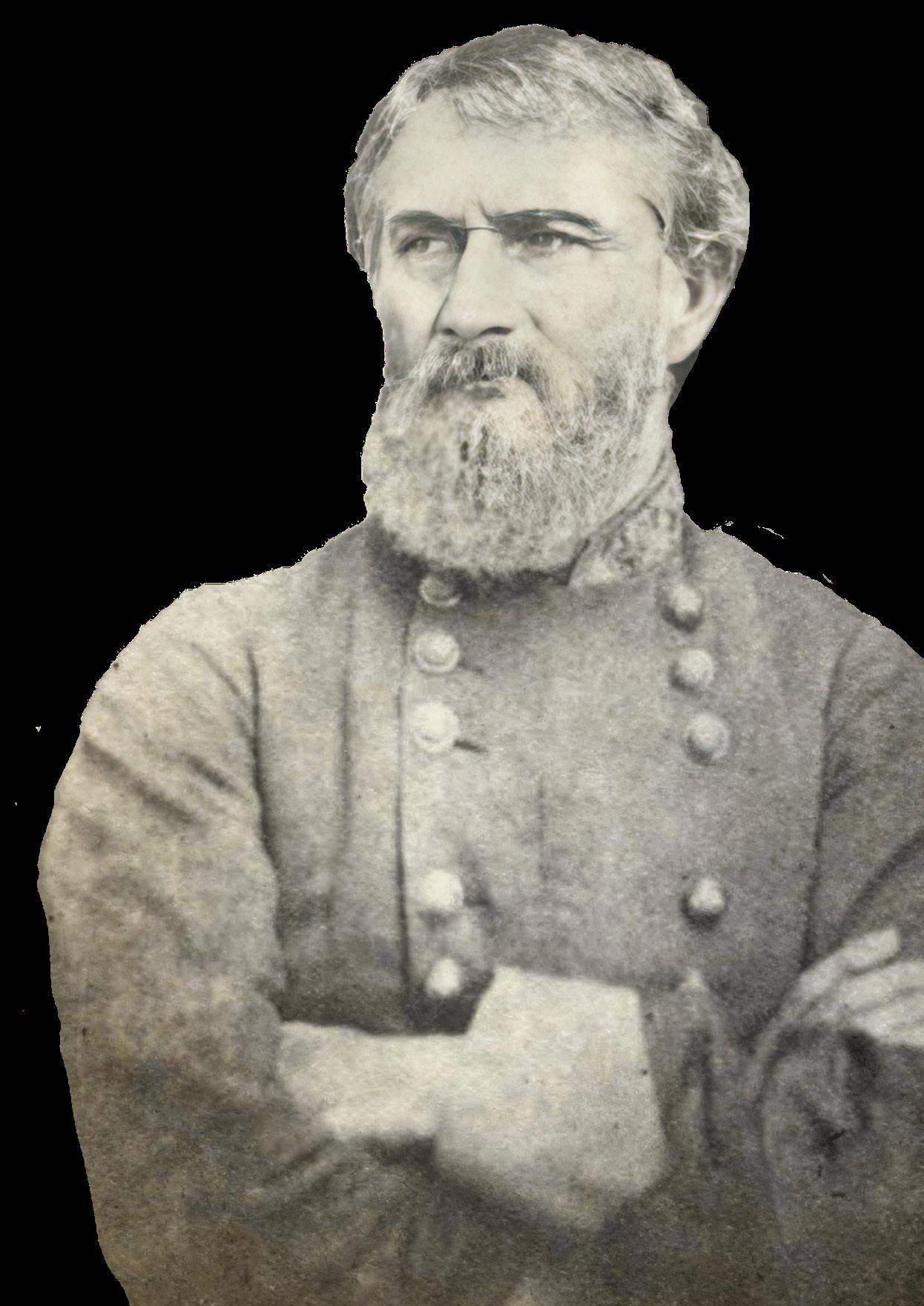

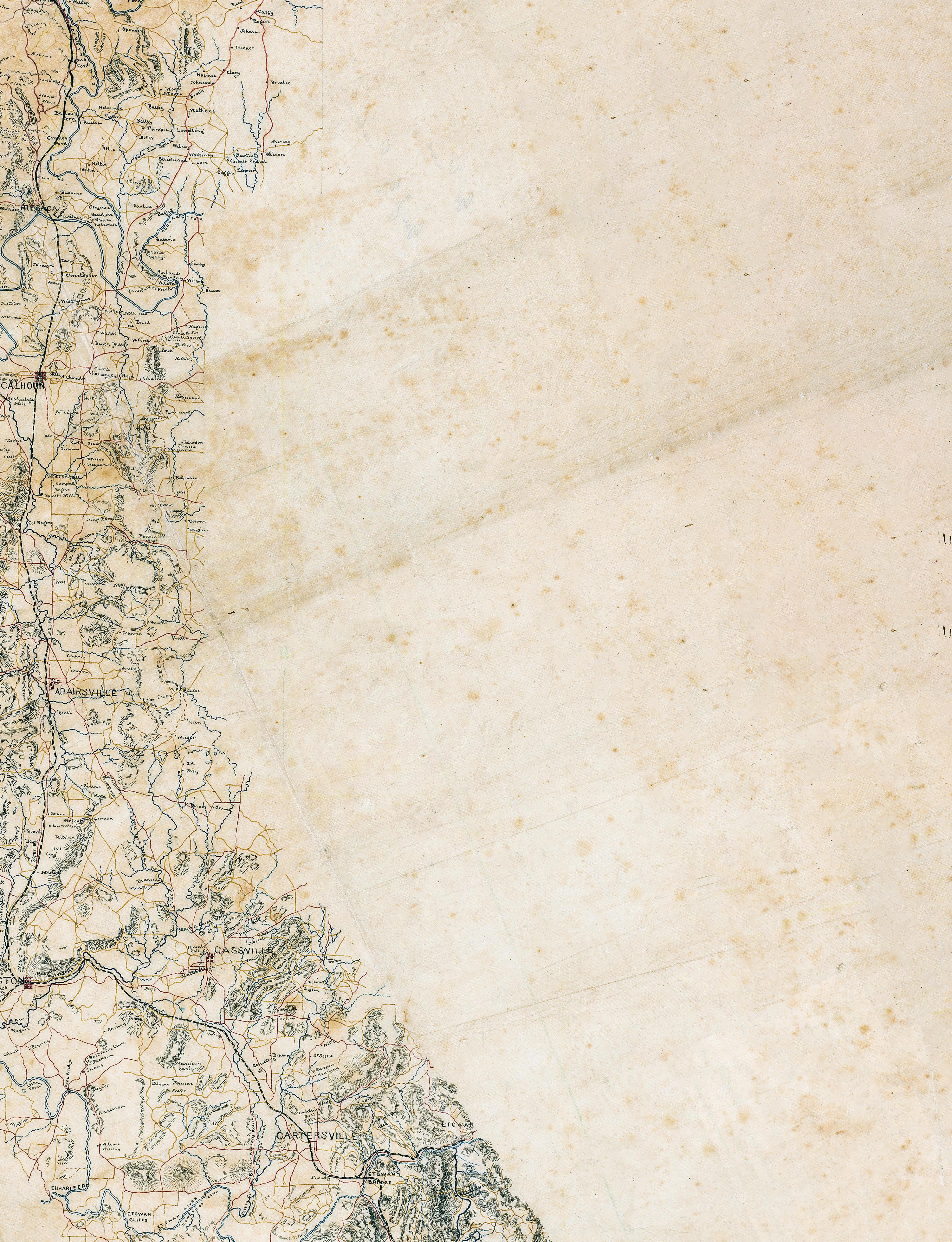

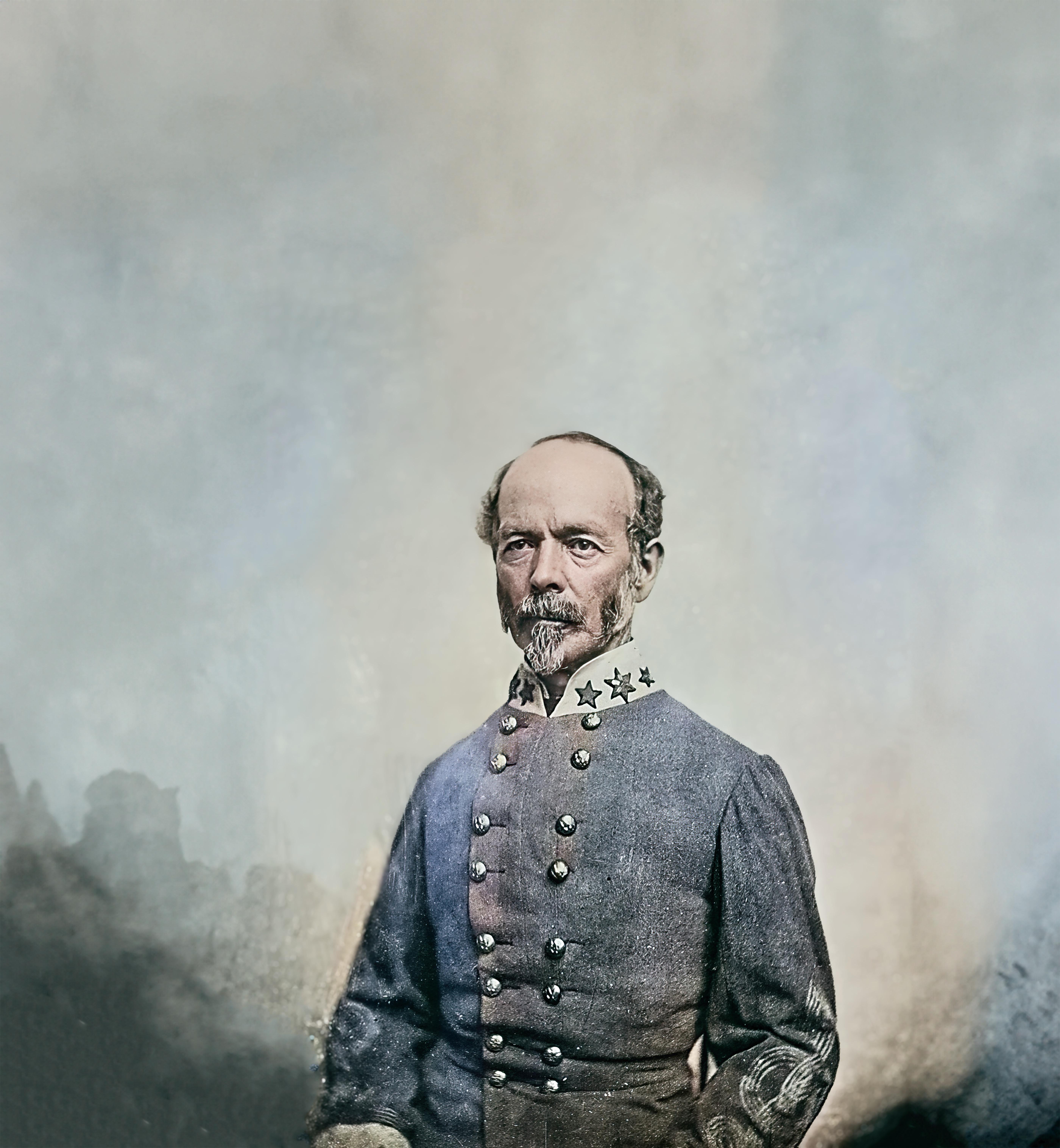

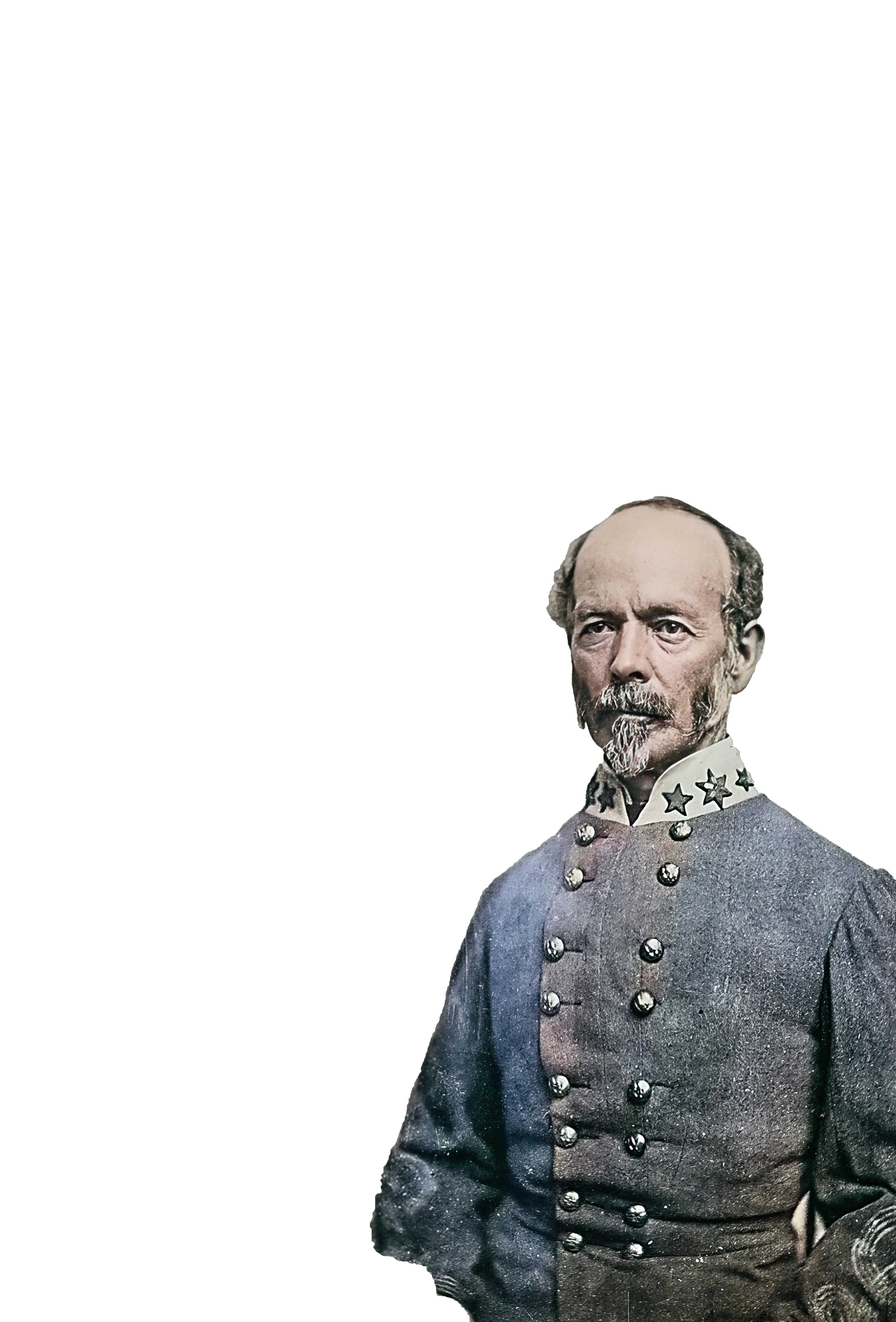

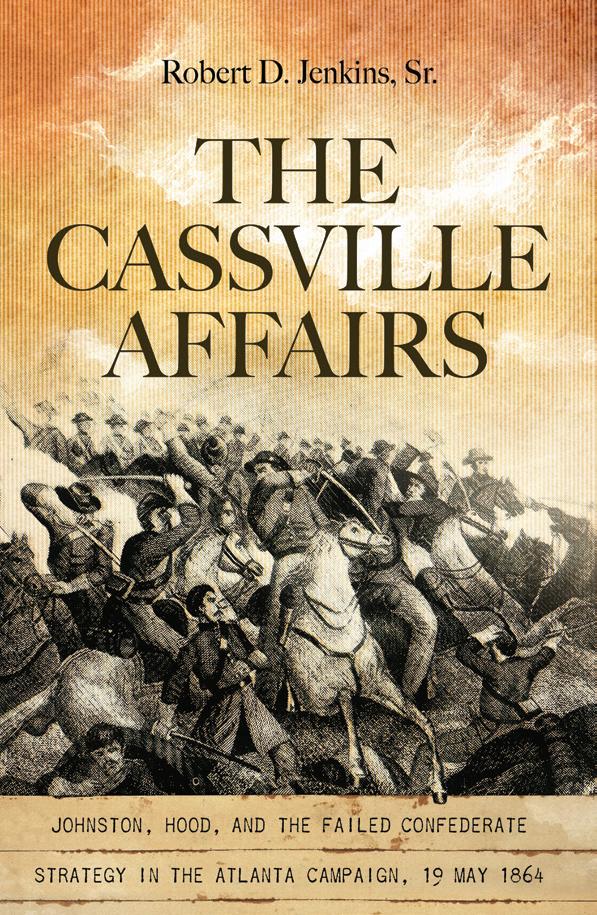

The Cassville Affairs

Johnston, Hood, and the Failed Confederate Strategy in the Atlanta Campaign, 19 May 1864

by Robert D. Jenkins, Sr.

Civil War historians have remained baffled over the Cassville controversies for the past 150 plus years. There are two versions of events: Confederate commanding General Joseph E. Johnston’s story and Lieutenant General John Bell Hood’s story. The Cassville Affairs promises to change our understanding of the events surrounding Cassville and close the gap in its history.

apply.

“Robert Jenkins has offered up a provocative new look at this pivotal moment in the decisive struggle for northern Georgia in the summer of 1864—and in the process, has overturned the conventional wisdom concerning Cassville by adding a deep new understanding of what happened here. This book should be considered essential reading for anyone studying the Atlanta Campaign.”

David A. Powell, award-winning author of The Chickamauga Campaign trilogy

17 Civil War News Magazine | May-June 2024

Scott Hartwig

www.mupress.org Use coupon code MUPNEWS at checkout to receive a 20% discount on your entire order. Or—call 866-895-1472 toll-free to place your order with a Visa/MC. Shipping charges

$39, hardback • 440 pages • Bibliography • Indexes • Illustrations • Period & Modern Maps

(Photo by Barbara J. Sanders)

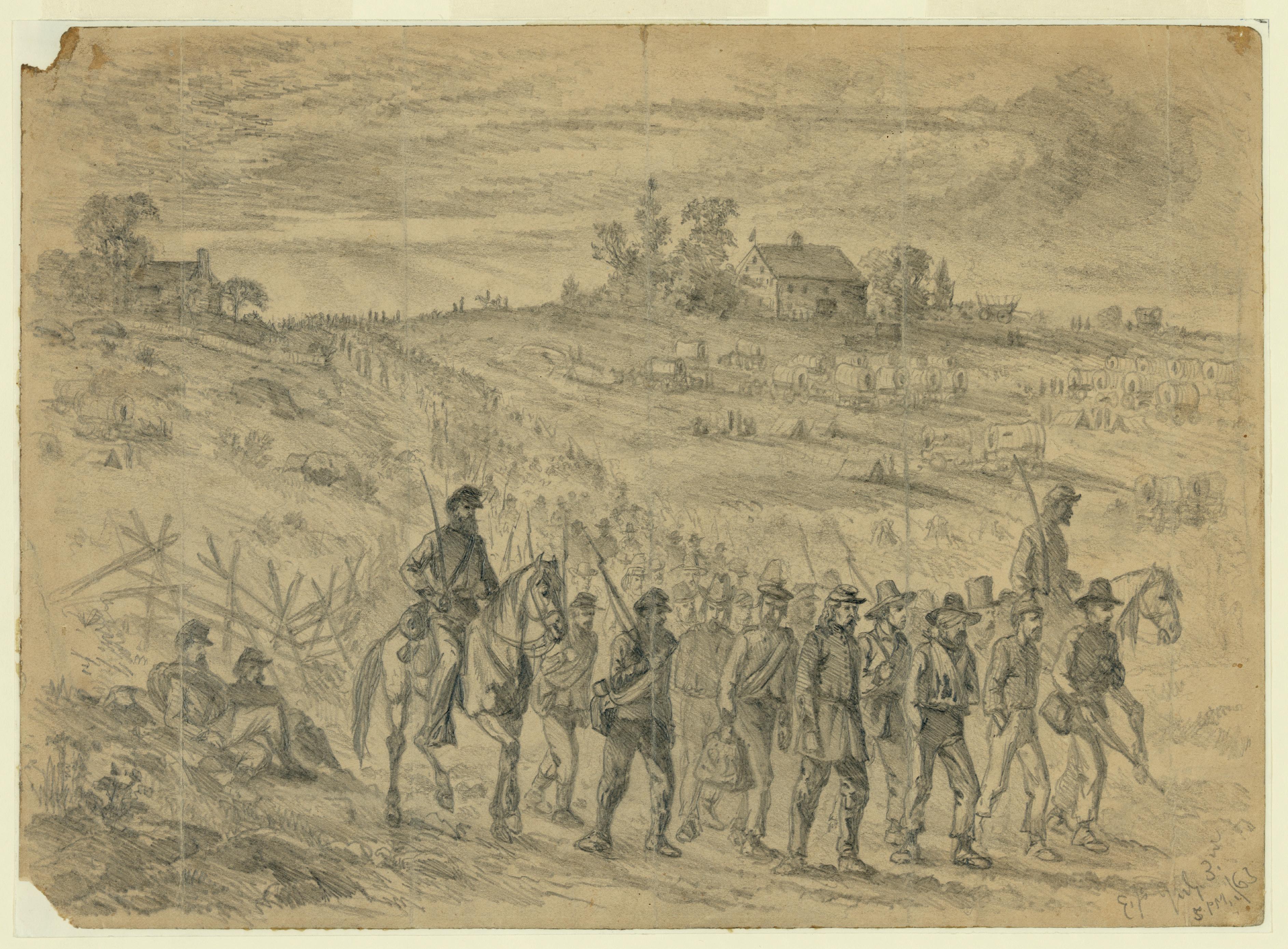

How Shall all These Wounds be Healed?

Exploring Battle’s Impact on Families

By Jonathan A. Noyalas

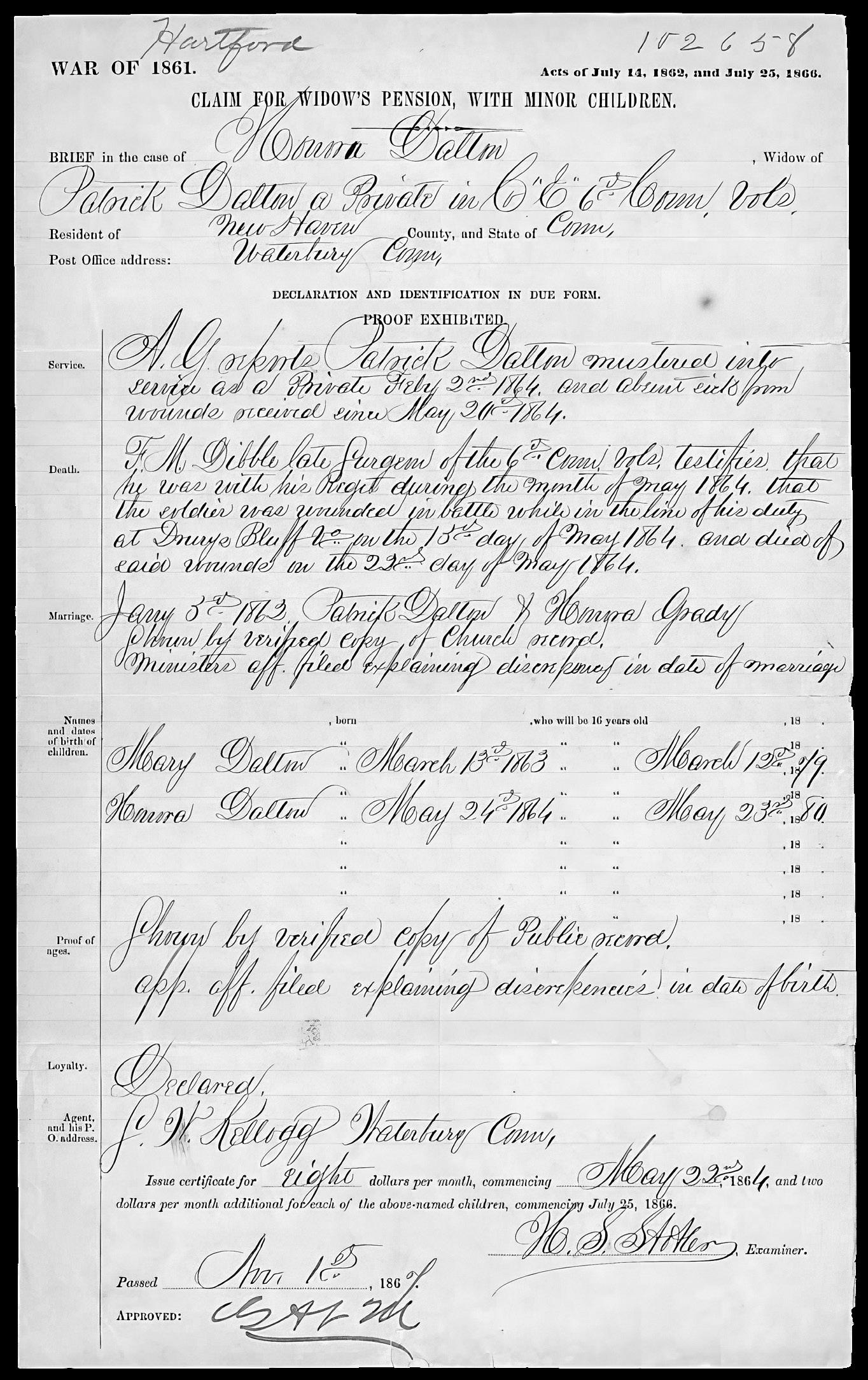

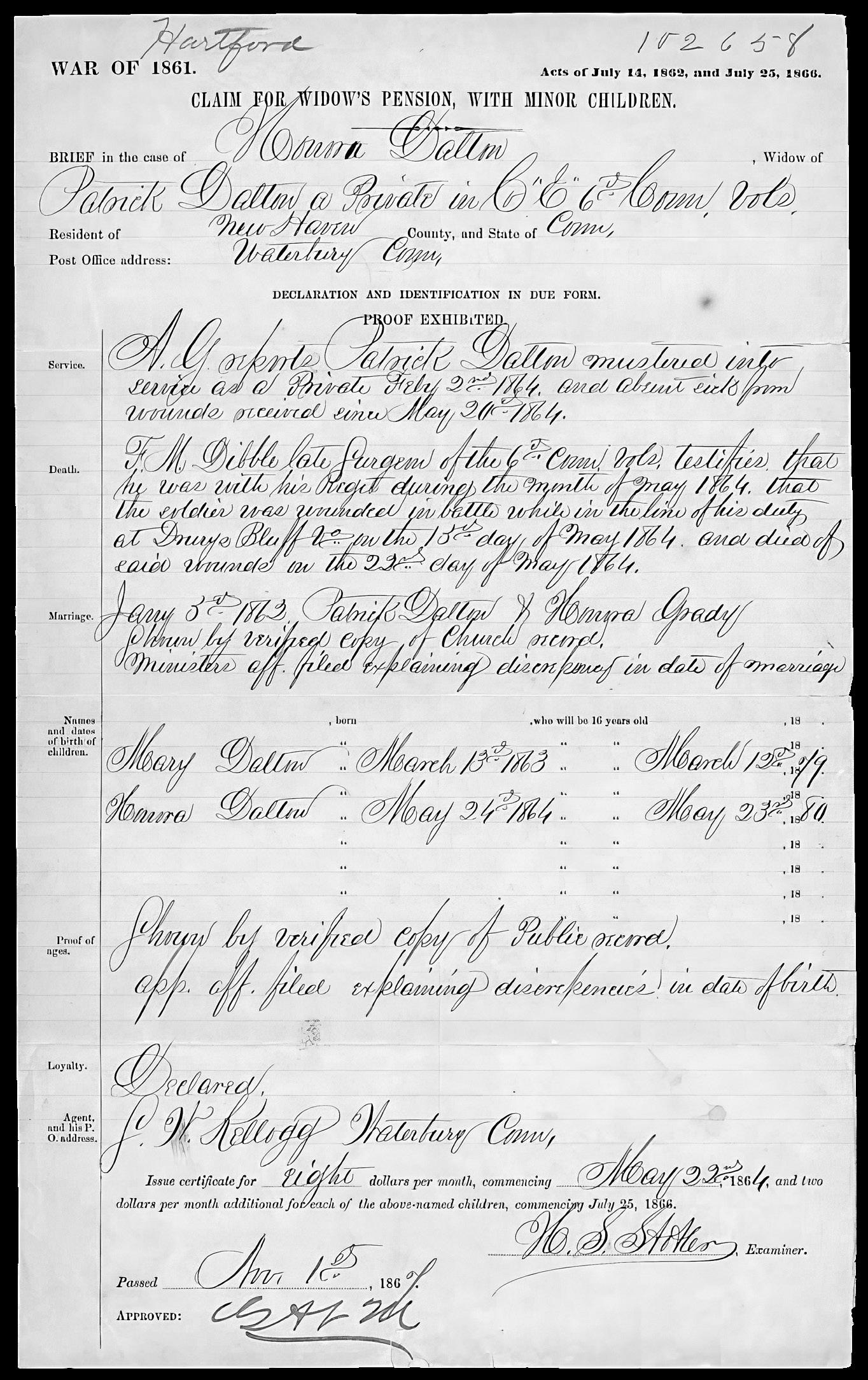

By spring 1864, Jane Boswell Moore, a nurse at a Union hospital near Bermuda Hundred, witnessed much suffering. During the previous two years, Moore, a native of Baltimore, Maryland, cared for wounded Union soldiers in Baltimore and at such notable battlefields as Antietam, Chancellorsville, and Gettysburg.1 As Moore went about her usual duties on May 21, 1864, she noticed a deceased Union soldier on a “bloodstained” stretcher “covered with a blanket.” Moore asked an “attendant” to remove the blanket and reveal the soldier’s face. It shocked Moore. “What a sight was that! I have seen death in almost every form, in the hospital and on the battlefield . . . I pray God I may never needlessly see such a sight again,” Moore wrote.2 She knelt beside the stretcher and searched the soldier’s pockets to “find some clue” as to his identity. From one of the pockets Moore pulled, as she explained, “a letter, perfectly saturated, dripping with the warm life-blood.” The letter was addressed to Private Patrick Dalton, 6th Connecticut Infantry, from the soldier’s wife, Honora.3 Moore took the letter, clipped a lock of Private Dalton’s hair, and wrote Honora that her husband succumbed to wounds received six days earlier near Drewry’s Bluff.4

After Honora received the crushing news of her husband’s death, she wrote Moore and expressed her gratitude “for the kindness” Moore “bestowed” toward her “beloved husband, and also in giving . . . the particulars of his death.” The “sad news” Honora received raised numerous questions in her mind, among them how she would care for her two children. “I am now a poor and lonely widow with two little children, one fourteen months and the youngest eight days old . . . so you see my circumstances,” Honora explained.5 Widow Dalton’s response struck a chord with Moore and forced her to contemplate the far-reaching impact of what happened on the battlefield. “This case is but one of thousands. Who shall make good the loss? How shall all these wounds be healed?”6 While nothing could ever replace her beloved husband or heal Honora Dalton’s broken heart, she could appeal to the United States government for financial assistance to aid her effort to care for herself and her two young children.

In the summer of 1861, the United States Congress, once it authorized President Abraham Lincoln to accept the service of 500,000 volunteers, passed an act which guaranteed a pension to any volunteer wounded or disabled during service “and the widow, if there be one, and if not, the legal heirs.”7 Although well-intentioned, some believed the law confusing and inadequate. Attorney General Edward Bates was among those who criticized it. After reviewing the law, coupled with other pension statutes, Bates informed Speaker of the House Galusha Grow on March 11, 1862, that the new pension law created too much “uncertainty and obscurity” for the “suitable

Left: While no known images of Honora Dalton exist this image of an unidentified woman in mourning, holding a photograph of her husband typifies the unquantifiable grief felt by wives transformed into widows. (Library of Congress)

Attorney General Edward Bates believed the pension law passed by Congress in the summer of 1861 was inadequate and confusing. Bates’s assessment of that law helped pave the way for a new pension law, one that President Lincoln signed on July 14, 1862. (Library of Congress)

provision . . . for the families” of soldiers who “may be killed or die in the service.”8 Four months after Bates’s appraisal of the law’s deficiencies President Lincoln signed a new pension bill that provided much needed clarity on who was entitled and compensation amounts. The law, one which Assistant Secretary of the Interior John Usher regarded as the “most munificent enactment of the kind ever adopted,” granted widows pension based on their husband’s rank.9 Widow’s compensation ranged from $30 per month, for widows of officers who held the rank of lieutenant colonel or higher, to $8 per month, for non-commissioned officers, musicians, and privates.10 The law also granted an additional $2 each month per child until that child reached the age of sixteen.11

In the estimation of Commissioner of Pensions Joseph Barrett the 1862 law streamlined the claim submission process. “Nothing is required of the claimant which is not necessary and, in most instances, conveniently obtainable,” Barrett wrote on November 15, 1862.12 Filing a claim proved anything

but easy for Honora Dalton. She submitted her application on October 10, 1864. On January 21, 1865, the Bureau of Pensions returned the application because of a discrepancy in the couple’s marriage date. On one form Honora stated that she married Patrick on January 5, 1852. Another document noted the two wed on January 5, 1862. While officials in Washington eventually resolved the discrepancy (the couple married on January 5, 1852) and awarded Honora Dalton a pension of $8 per month with an additional $4 for her two children the approval did not come until September 3, 1867. Although the Bureau of Pensions paid Dalton retroactively from the date of

Below:

her husband’s death, she endured a stretch of forty months where she had to figure out a way to support her and her family.13

Aside from the $15 Honora initially received from sympathetic neighbors and friends little is known about how she supported herself during the period she awaited approval.14 Sadly, Dalton’s story is not unique. Whether widows waited months or years (most widows claims were approved within two to three months) they needed an immediate income and sought work. Finding employment proved particularly daunting for mothers. For example, in early 1865 the Female American Guardian Society in New York City reported that an unidentified widow of a Union soldier killed in 1863 on picket duty while serving in the Army of the Potomac confronted unnamed bureaucratic obstacles. The widow had no other alternative than to find employment. She easily found work as a house servant in New York City for $6 per month. The employer, however, prohibited her from bringing her three children with her. Confronted with financial destitution the widow had no other alternative than to accept the job and temporarily place her children in an orphanage. The widow entrusted her children to the care of the House of Industry and Home for the Friendless located on East 29th Street in New York City. “The claims of the bereaved wife to a pension were as yet unmet, she had therefore craved permission to entrust her… children for a while to the institution,” explained an official at the House of Industry and Home for the Friendless.15 Regrettably, this was a decision too many mothers had to make. Sometimes this decision, one intended to alleviate a mother’s burden, compounded a war widow’s grief. For example, several days after an unidentified widow of Union soldier entrusted her son to the care of an orphanage in New York City, she was notified that the son ran away and joined a gang. Fortunately, with assistance from New York’s American Female Guardian Society, they found the boy and temporarily placed him with a farmer in a more rural part of the state.16

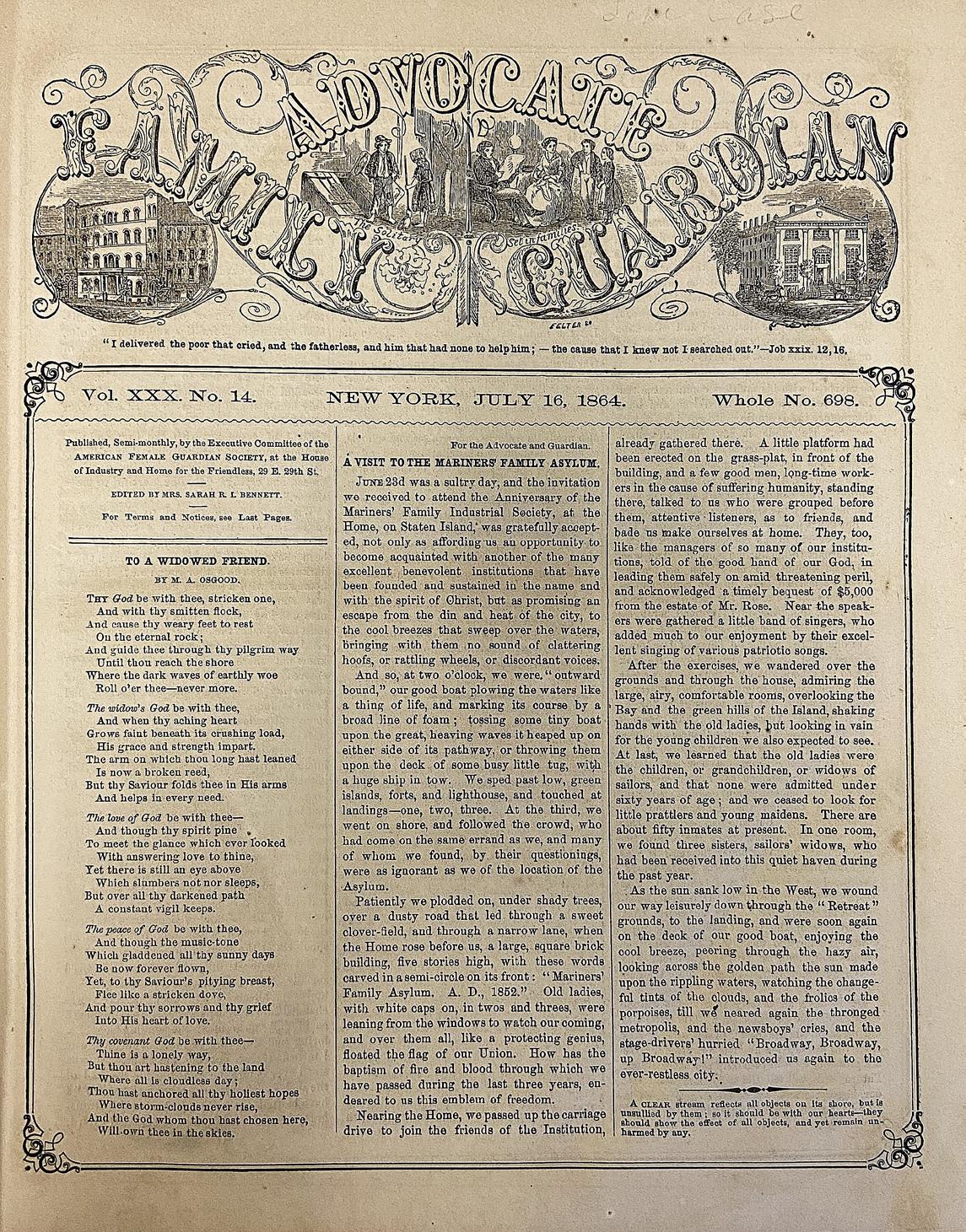

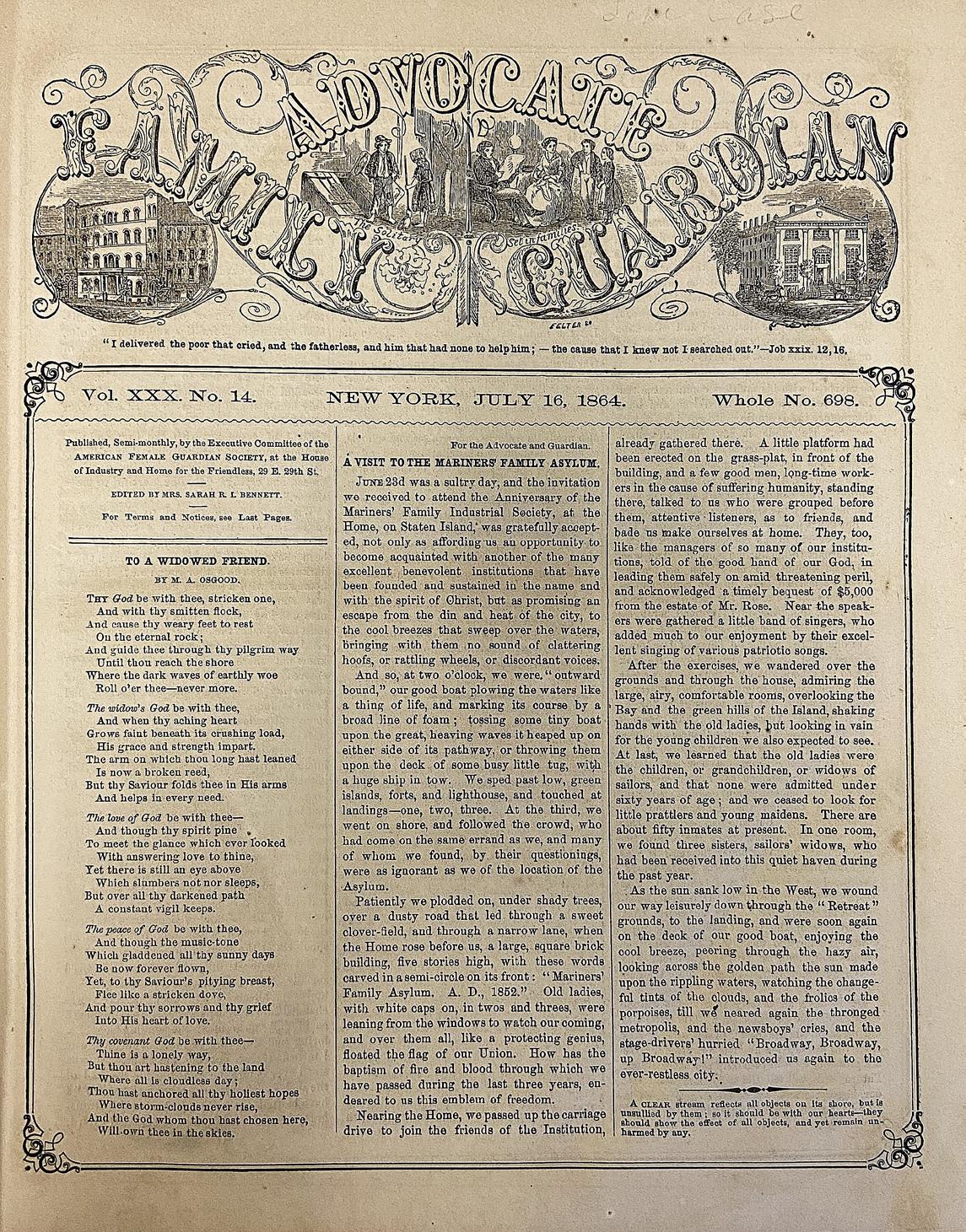

Right: The Advocate and Guardian, published bi-weekly by the American Female Guardian Society in New York City, championed the cause of aid for widows and children during the conflict. (Jonathan A. Noyalas Collection)

Page from Honora Dalton’s claim for a widow’s pension. (National Archives & Records Administration)

The precise number of children sent to institutions either because a mother sought employment or the child was a full orphan, meaning that the mother preceded the father in death, is unknown. Historians estimate that hundreds of thousands of children ended up in orphanages during the conflict. In Pennsylvania 1,226 children were enrolled in the Commonwealth’s Soldiers’ Orphan Schools by the war’s end.17 That number represents four percent of all Pennsylvanians who died in the Union’s service.18

Children who found themselves in institutions such as those established in Pennsylvania formed bonds with each other, a connection that lasted a lifetime. For example, in the decades after the conflict children sent to one of the nearly forty Soldiers’ Orphan Schools in the Keystone State formed the “Sixteeners.” The organization, which derived its name from the age when children left the school, oftentimes planned reunions with support from the Grand Army of the Republic. Reunions, such as the one that occurred for the Sixteeners who attended the Soldiers’ Orphan School in Mount Joy, Penn., in 1937, promised an opportunity for those “left bereft of one or both parents” during “those terrible years of the Civil War” to “come back with their memories” and view “relics of the old days.”19

As difficult as things were for widows and children of Union soldiers, the obstacles their Confederate counterparts faced seemed even more insurmountable. Despite entreaties, such as one issued by a newspaper in Harrisonburg, Virginia, in the late summer of 1863 for the Confederate government to pass legislation to “take care of the soldiers’ widows and orphans in these times of severe trial,” Confederate authorities never created a system to support war widows and their children.20 The only provision the Confederate government made came in the autumn of 1862 when the Confederate Congress passed legislation that entitled the survivor of a Confederate soldier to receive back pay. Claiming those funds involved submitting a claim in what historian Robert Kenzer characterized as a “very complicated and exhausting” process.21

widows to a monthly allotment of one bushel of grain and eight pounds of bacon. Children, up to age ten, received half a bushel of wheat and three pounds of bacon.22 In Georgia, as one newspaper correspondent noted, authorities offered salt “gratuitously to ‘all widows of soldiers” and “all other families dependent upon the labor of a soldier.”23

“THE MEMORY OF FOND PARENTS, AND DEVOTED HUSBANDS, SONS AND BROTHERS, WHO FELL IN THIS CRUEL WAR WILL HAUNT THE VISIONS OF MILLIONS, MARRING EVERY PLEASURE AND CASTING A GLOOM OVER THE PATHWAY OF LIFE… WIDOWS AND ORPHANS, WHOSE HUMBLE HOMES, THE ABODES IN MANY CASES OF PENURY AND SUFFERING WILL FOR MANY LONG YEARS BE LIVING WITNESSES OF THIS FEARFUL AND BLOODY CIVIL WAR.”

Some Confederate states, such as Virginia, attempted to alleviate the suffering of widows and children by establishing a system for local governments to provide foodstuffs. The provision entitled

Regardless of the support a widow might receive, some could not confront the incalculable pain of losing a loved one. No amount of money, food, or expressions of sympathy could remedy shattered hearts, whether Union or Confederate. Newspapers, North and South, contained sad and grisly details of how suicide seemed the only outlet for widows.24

When Henrietta Commerford, whose husband Patrick, a private in 9th New Jersey Infantry, died on January 3, 1863, from wounds

Ribbon worn at a reunion of Sixteeners who attended the White Hall Soldiers’ Orphan School in Camp Hill, Pennsylvania.

(Jonathan A. Noyalas Collection)

received near New Bern, N.C., five days earlier, she applied for a widow’s pension.

Although awarded a monthly pension of $8 per month Henrietta struggled to make ends meet and so ventured to New York City to find work as a servant.25

Although she found a job Henrietta, overburdened by financial difficulties and her husband’s death, decided to commit suicide. On July 24, 1865, she overdosed on laudanum. The following day The Brooklyn Daily Eagle carried the sad story of the “RASH ACT OF A WAR WIDOW—Henrietta Commerford” who “committed suicide . . . by taking two drachms of laudanum. She had been in low spirit for some time in consequence of the death of her husband . . . becoming dejected she came to the determination to end her existence and thus avoid further earthly trouble.”26

The stories of the soldiers and family members explored in this article, ones that emulate the experiences of tens of thousands of people North and South, underscore two significant points worthy of consideration when thinking about the broader impact of Civil War battles. First, a battle’s significance can be measured in multiple ways. Traditionally a battle’s importance is judged by its strategic consequences or political outcomes. While noteworthy those usual measures fail to account for how what happened on the battlefield affected families. Whether the war’s largest battle or its smallest skirmish, for the wife transformed into a widow or the child made fatherless the war’s most significant moment came when their soldier at the front gasped his final breath. Second, for those left behind the impact of

what occurred on the battlefield continued for years after the conflict. In some instances, the tribulations widows and children confronted after a loved one’s demise remained with them for the remainder of their lives.

As the Civil War entered its second summer a resident of Marysville, Calif., far removed from the war’s major theaters, pondered how history, when the Civil War finally ended would remember the conflict. This unidentified Californian thought that future generations, those not alive during the war or directly impacted by the conflict, would exert all their attention on tales of heroism, bravery, and courage displayed on the battlefield. Although important, this Californian lamented that those celebratory stories would orient attention away from the war’s tragic consequences for families.27 This

“TAKE CARE OF THE SOLDIERS’ WIDOWS AND ORPHANS IN THESE TIMES OF SEVERE TRIAL.”

unknown Californian wrote in early August 1862: “The memory of fond parents, and devoted husbands, sons and brothers, who fell in this cruel war will haunt the visions of millions, marring every pleasure and casting a gloom over the pathway of life… Widows and orphans, whose humble homes, the abodes in many cases of penury and suffering will for many long years be living witnesses of this fearful and bloody civil war.”28

Jonathan a noyaLas is a history professor at shenandoah University and direCtor of its MCCorMiCk CiviL war institUte. he is the aUthor or editor of sixteen Books inCLUding slavery and freedoM in The shenandoah valley during The civil War era (University press of fLorida) and the forthCoMing The bloodTinTed WaTers of The shenandoah (savas Beatie).

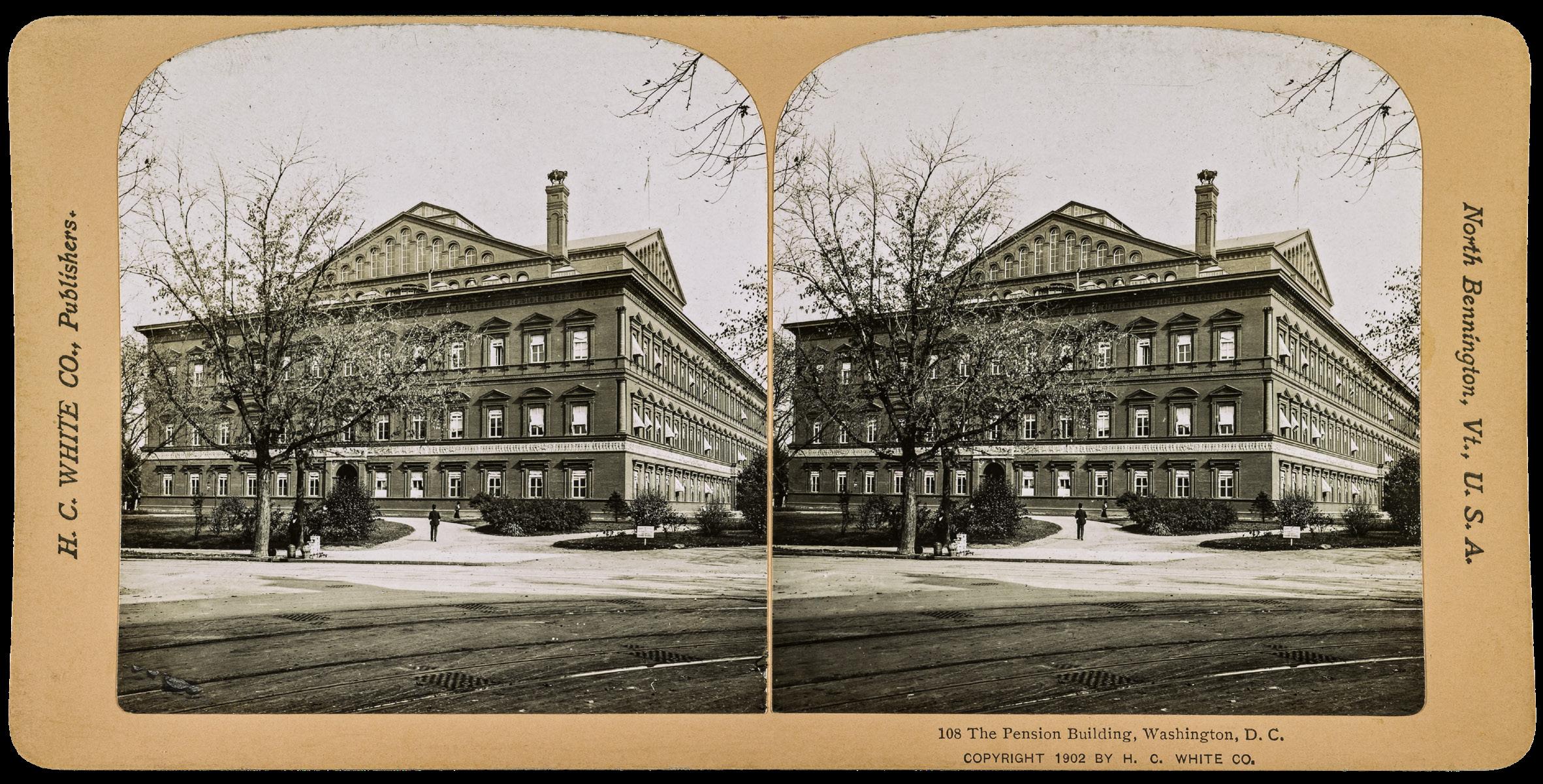

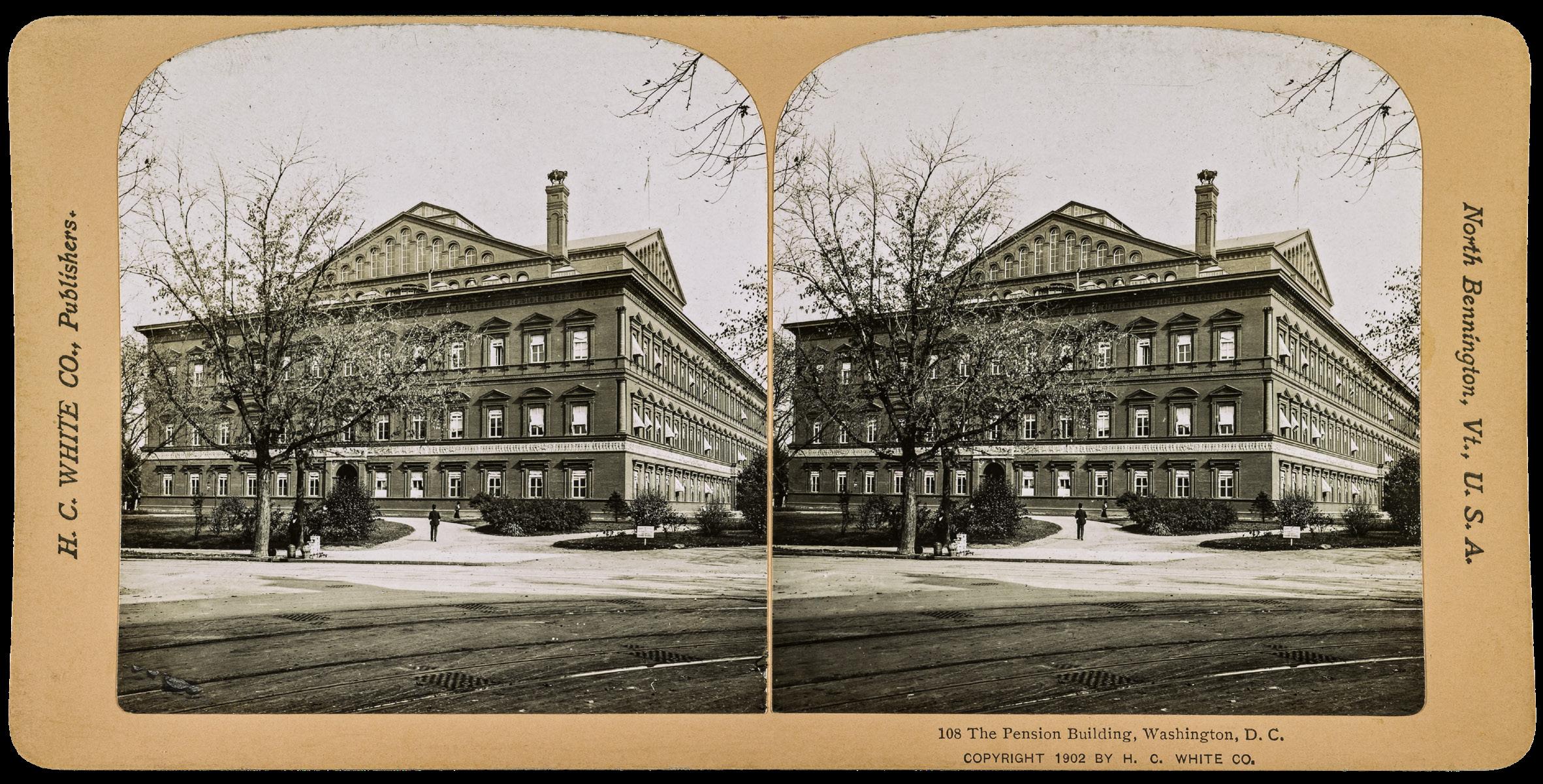

Above: Stereoview of Pension Building in Washington, D.C. By the end of 1865 the United States Bureau of Pensions approved claims for nearly 85,000 war widows. (Library of Congress)

Below: South and West Facades of the Pension Building, Washington, D.C. (Library of Congress)

1 The Reports of the Committees of the House of Representatives for the First Session of the Fifty-First Congress, 1889-’90 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1891), 1; Frank Moore, Women of the War: Their Heroism and Self-Sacrifice (Hartford, CT: S.S. Scranton & Co., 1866), pp. 554-570.

2 Jane Boswell Moore to friend, May 28, 1864, quoted in Advocate and Guardian (New York), July 16, 1864.

3 Ibid.

4 Patrick Dalton, 6th Connecticut Infantry, Compiled Service Record, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC. Items from this collection hereafter cited as CSR. Items from this repository hereafter cited as NARA.

5 Honora Dalton to Jane B. Moore, May 31, 1864, quoted in Advocate and Guardian (New York), July 16, 1864.

6 Advocate and Guardian, July 16, 1864.

7 Guide for Soldiers & Sailors’ Heirs (New York: Bragdon & Yerby, 1862), pp. 45-46.

8 Edward Bates to Galusha Grow, March 11, 1862, in Executive Documents Printed by Order of the House of Representatives during the Second Session of the Thirty-Seventh Congress, 1861-’62 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1862), 7: pp. 4-5.

(Washington: Government Printing Office, 1862), 2: p. 586.

13 Patrick Dalton, 6th Connecticut Infantry, Widow’s Pension, NARA.

14 Advocate and Guardian, July 16, 1864.

15 Ibid., January 2, 1865.

9 John P. Ushur quoted in John William Oliver, History of the Civil War Military Pensions, 1861–1865 (Madison: University of Wisconsin, 1917), p. 10.

10 Ibid.

11 Ibid.

12 Report of the Commissioner of Pensions, November 15, 1862, quoted in Messages of the President of the United States to the Two Houses of Congress at the Commencement of the Third Session of the Thirty-Seventh Congress

16 Ibid.

17 Sarah D. Bair, “Making Good on a Promise: The Education of Civil War Orphans in Pennsylvania, 1863-1893,” History of Education Quarterly 51 (Nov. 2011): p. 469.

18 Ibid., p. 460.

19 Sunday News (Lancaster, PA), June 13, 1937.

20 Rockingham Register (Harrisonburg, VA), September 4, 1863.

21 Robert Kenzer, “The Uncertainty of Life: A Profile of Virginia’s Civil War Widows,” The War Was You and Me: Civilians in the American Civil War, ed. Joan E. Cashin (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2002), p. 113.

22 Ibid., pp. 122-123.

23 Alexandria Gazette (Alexandria, VA), August 21, 1863.

24 For further discussion of suicide among wartime widows see Diane Miller Sommerville, Aberration of Mind: Suicide and Suffering in the Civil War-Era South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2018), pp. 67-75.

25 Patrick Commerford, 9th New Jersey Infantry, Widow’s Pension, NARA; Patrick Commerford, 9th New Jersey Infantry, CSR, NARA; The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, July 25, 1865.

26 The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, July 25, 1865.

27 Angela Esco Elder, Love & Duty: Confederate Widows and the Emotional Politics of Loss (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2022), p. 2.

28 Marysville Daily Appeal (Marysville, CA), August 2, 1862.

& HISTORIC MEDAL RECREATIONS GAR Medal Replacement Ribbons Union Officer’s Ceremonial Sword Belt, Buckle, Shoulder Straps Custom Medal Designs Available PO Box 61, Chester Heights, PA 19017 www.cwmedals.com Civil War Recreations (845) 339-4916 sales@dellsleatherworks.com DellsLeatherworks.com

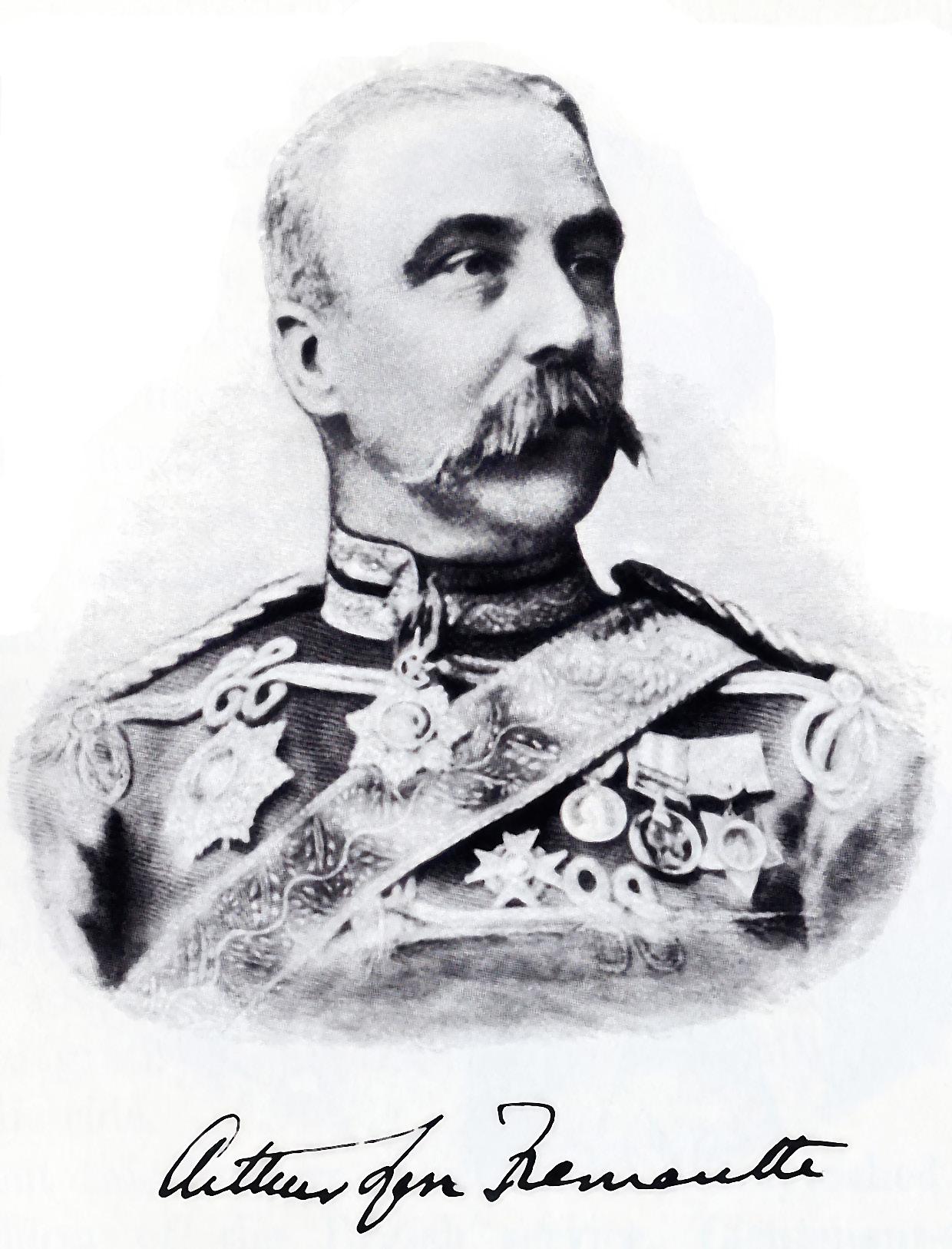

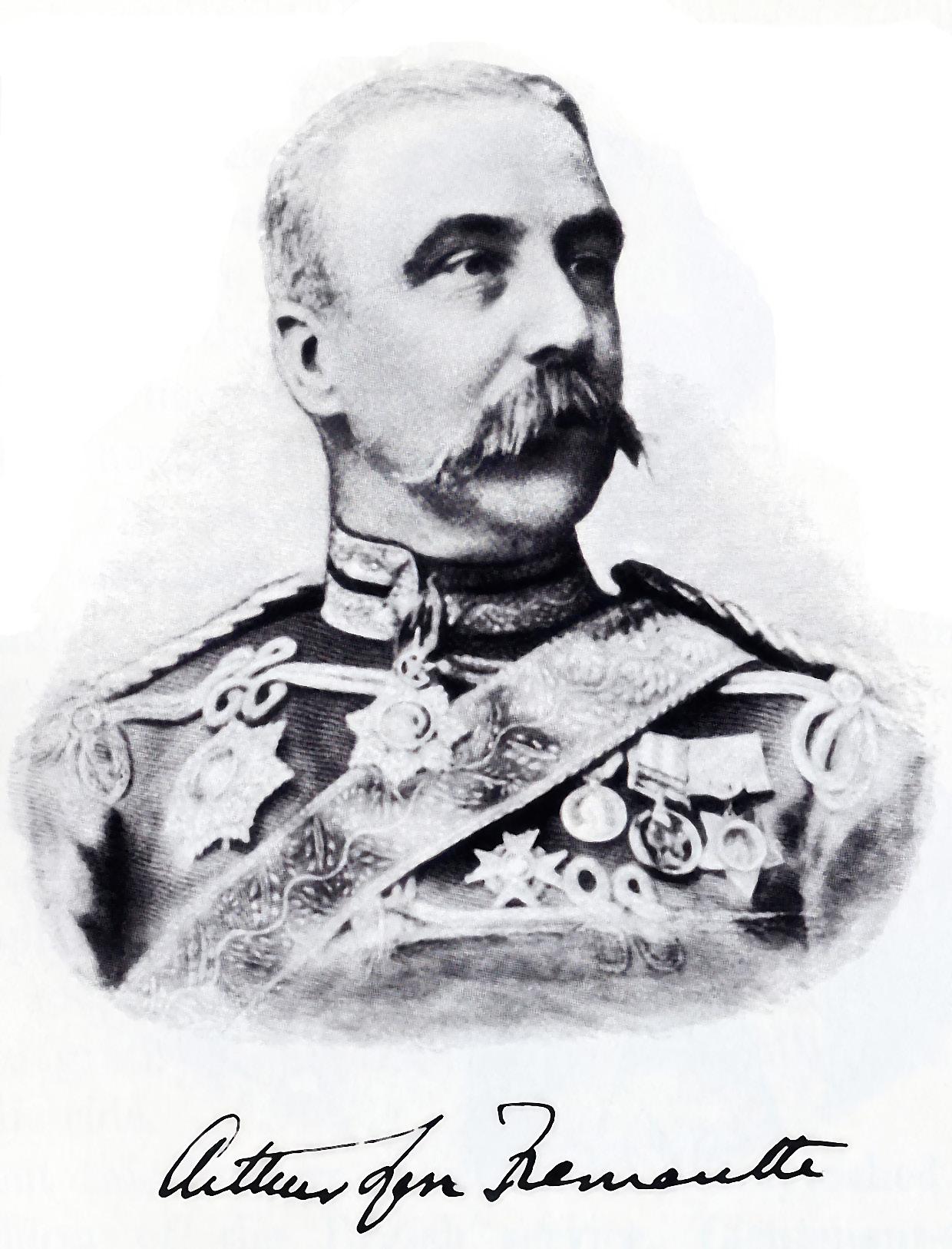

This & That: Colonel Fremantle, Welcome to Texas

By Gould Hagler

“In spite of their peculiar habits of hanging, shooting, &c., which seemed to be natural to people living in a wild and thinly-populated country, there was much to like in my fellow-travelers.”

– Lt. Col. Arthur J.L. Fremantle

Lt. Col. Arthur J.L. Fremantle’s Three Months in the Southern States is a well-known and highly regarded memoir. The British officer traveled to the Confederacy in 1863, via Cuba and Mexico, and spent three months traversing the new republic. His account, first published in 1864, tells of the land he crossed and the people he met. He offers commentary on the war being waged, on the issues related to that war and on the armies and people doing the fighting. I recently re-read the book’s first two chapters which take the reader across the Rio Grande from Matamoros and through the vast state of Texas. In this column, we will travel with the colonel to see what he saw and hear what he heard as he traveled through the Lone Star State. For much of the way his “pilot,” as Fremantle put it, was a helpful Irish-Texan merchant, Mr. M’Carthy.

On April 2, Fremantle and M’Carthy “landed at the miserable little village of Bagdad, on the Mexican bank of the Rio Grande.” They made their way to Matamoros, a few miles upstream. Fremantle carried a letter of introduction addressed to Maj. Gen. John Bankhead Magruder, commander of the District of Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona, whom he hoped to meet while in Brownsville. While waiting, Fremantle crossed the river between Matamoros and Brownsville several times. On both sides of the border, he met various Confederate officers, local merchants, and the British viceconsul in Matamoros.

Fremantle enjoyed the hospitality of his new acquaintances at dinners, dances, and the theater. There were “endless cocktails” to be imbibed, some “prepared in the most scientific manner.” On a less pleasant plane the British newcomer learned something of rough frontier justice. Some officers he met had recently hanged a man, a Unionist whom they had

captured in a cross-border, retaliatory raid. A higher-ranking officer told Fremantle that this had been done “without his sanction,” but no action had been taken against the officers in question.

Having waited 11 days for Magruder, and not knowing when or whether the general would appear in Brownsville, Fremantle and M’Carthy embarked on their journey. “Our vehicle,” Fremantle tells us, “was a roomy, but rather overloaded, four-wheel carriage with a canvas roof, and four mules.” The equine contingent was supposed to include two horses to help pull the vehicle through deep sand.

In charge of this expedition was Mr. Sargent, “our portly driver,” who motivated his mules with loud and frequent cussing. Assisting Mr. Sargent was another mule driver, “a rough-faced, dirty-looking man, who rode up on a sorry nag.” Fremantle was surprised to hear M’Carthy address the assistant “with the title of ‘Judge.’” The Judge, we learn, was a minor magistrate of some sort, and also a member of the Texas state senate. The nag that carried the Judge was the only horse to arrive. The other had broken down, the Judge explained, so one would have to do.

The trek would be an arduous one. There was much deep sand ahead, and only one nag to supplement the mules’ tractive power. Water and firewood were both scarce. The water at the first well reached “was very salt*, and made very indifferent coffee,” according to our informant, and the firewood at this stop could be reached only in the chaparral.” At a later point in the trip, the party resorted to using a ratranch for fuel. For the uninitiated, Fremantle helpfully added that rat-ranches “are big sort of mole-hills, composed of cowdung, sticks and earth, built by rats.”

At one stop wild hogs devoured most of the company’s

25 Civil War News Magazine | May-June 2024

&

fresh meat. The men slept in the open and were tormented by ticks and fleas. When they reached water (or struck water, as Fremantle adjusted his idiom to Texas mode), it was often salt. Not all the water, however: one time it came down from the heavens in a heavy two-hour thunderstorm. “No sooner had we escaped from the sand than we fell into the mud, which was still worse.”

Two days out from Brownsville, Fremantle “espied the cavalcade of General Magruder passing us by a parallel track, about half a mile distant.” He and M’Carthy rushed to catch up with the general’s command and were warmly greeted when they succeeded. They accepted a dinner invitation and spent a long, festive evening with the hospitable general and his staff. A captain played the fiddle; Magruder and other officers sang; and “brewed punch” brightened everyone’s mood. One officer, an “aged and slightly elevated militia general,” was especially brightened and made several “elegant” speeches. The general/host/ songster wore a red woolen cap, as he customarily did at such times.

Fremantle described Magruder as a “fine soldierlike man, of about fifty-five, with broad shoulders, a florid complexion, and bright eyes.” The general “spoke of the Puritans with intense disgust, and of the first importation of them as ‘ that pestiferous crew of the Mayflower.’”

Antonio, where M’Carthy’s store was located and where Fremantle slept in a hotel. San Antonio was the secondlargest city in Texas, with 10,000 people and “houses well built of stone.”

Fremantle learned of more frontier justice while in San Antonio. “A woman was murdered at a ranch close by some time ago, and five bad characters were put to death at San Antonio by the vigilance committee on suspicion.”

Fremantle remained in San Antonio for three days, meeting with Confederate officers and touring about. He saw two very pleasant springs and visited ruined missions. With letters of introduction to Gens. Braxton Bragg and Leonidas Polk, given to him by a colonel, Fremantle set out for Houston. On this leg he took a stage coach “into the interior of which nine people were crammed on three transverse seats.” Others—“many others,” Fremantle says—clung to the roof of the conveyance. As the stage rocked along, he admired the cultivated countryside and for the first time saw cotton fields. The other passengers were curious to learn “what was thought of their cause in Europe; and none of them seemed aware of the great sympathy which their gallantry and determination had gained for them in England in spite of slavery.”

On borrowed horses (and accompanied by men tasked with returning them), Fremantle and M’Carthy caught up with Mr. Sargent and the Judge. Thanks to his encounter with Magruder, Fremantle was armed with “heaps of letters of introduction.”

As he and his companions continued, they left the flat, sandy (or muddy, depending) territory and entered a more pleasant landscape, “undulating or ‘rolling country,’ full of live oaks of very respectable size.” Fremantle met some Texas rangers and noted they wore “the most enormous spurs I ever saw.” Also noteworthy was a practice of the women he met: “Texas females are in the habit of dipping snuff.”

Eleven days out of Brownsville, the travelers reached San

In Alleyton, 75 miles west of Houston, Fremantle left the stage and boarded a train. He noted that in the democratic west “there was only one class.” The comfortable seats “seemed luxurious after the stage.” The engine and its two passenger cars crossed the Brazos River “in a peculiar matter.” It gained speed on a steep decline as it approached the river, raced across the bridge and, powered by steam and momentum, managed to top the incline on the opposite side. The crossing was successful, “But even in Texas this method of crossing a river is considered rather unsafe.”

In Houston, Fremantle spent his first night in a crowded hotel room, then was invited to stay at the home of a General Scurry, for whom he had a letter of introduction from General Magruder. Scurry arranged a dinner for the visitor, inviting several officers and a judge, which gave his British guest another opportunity to meet people and learn about the

26 Civil War News Magazine | May-June 2024

Lt. Col. Arthur J.L. Fremantle.

Confederacy, its people, and its cause.

The following day Fremantle boarded a train for Galveston. On the train he by chance met the man for whom Houston was named. Fremantle found Sam Houston to be “a remarkable and clever man…, extremely egotistical and vain.” Houston was governor of the state in 1860 and “opposed the secession movement, and was deposed.” This Texas hero died less than three months after his encounter with Colonel Fremantle.

While en route Fremantle received a telegrammed invitation from the commander in Galveston. His host arranged for the colonel to view the port’s defensive works, some still under construction. The fortifications were designed by a Confederate officer who had formerly been in the Austrian army. The workers included 150 whites and 600 slaves “lent by the neighboring planters.” Fremantle paid a call on the British consul who, blockaded with the Confederates, was unable to communicate with the outside world.

Fremantle returned to Houston and from there took a train to Navasota, a town 70 miles to the north, where the rail line ended. His destination was Shreveport, La., 250 miles distant. He left Navasota by stagecoach, one just as cramped as the previous one and dangerously top-heavy from the weight of topside passengers. His fellow-travelers were “mostly elderly planters or legislators, and there was one judge from Louisiana.” As he conversed with these gentlemen, he heard some things that would not have been spoken had any military men been present. Fremantle writes that his “companions were united in speaking with horror of the depredations committed in this part of the country by their own troops on a line of march.”

On this leg of the journey the hotel accommodations were even worse than the ones Fremantle had endured earlier. He and the judge shared a bed so dirty that they slept in their clothes, even with their boots on. The judge commented that the boots “were a d____d sight cleaner than the bed.”

In Marshall, Fremantle got a respite from the ordeal of riding in a packed stagecoach. From this town, 40 miles from Shreveport, Fremantle rolled toward the Louisiana border on a comfortable railroad train. However, this track ran only 16 miles east of Marshall, at which point Fremantle and the other passengers detrained and were “crammed into another stage.” Soon the stage was in Louisiana, some 20 miles from Shreveport.

When Fremantle crossed the state line on May 8, he had been in Texas for one month and eight days. Twenty-five of those days were spent on the move, by carriage (with Mr. Sargent and the Judge), by stage and by rail. Google Maps tells me that, counting his side trip to Galveston and back, he covered nearly 800 miles. On the way, he met numerous Confederate officers, including several of high rank. He traveled with and conversed with civilians of various sorts and stations in life. He saw much, heard much, and learned much about Texans, more generally about Southerners, and about the war being fought by these people to win their independence. The journey so far had been in an area that had witnessed little fighting, but as he moved east that would change.

*This is not a typo. I was surprised to learn that “salt” is an adjective as well as a noun and a verb.

goULd hagLer is a retired LoBByist Living in dUnwoody, ga. he is a past president of the atLanta CiviL war roUnd taBLe and the aUthor of georgia’s confederaTe MonuMenTs: in honor of a fallen naTion, pUBLished By MerCer University press in 2014. he has Been a regULar ContriBUtor to cWn sinCe 2016. he Can Be reaChed at goULd.hagLer@gMaiL.CoM.

27 Civil War News Magazine | May-June 2024 &

Maj. Gen. John Bankhead Magruder.

28 Civil War News Magazine | May-June 2024 Contact Mike at: 910-617-0333 • mike@admci.com Provenance a Must! Fort Fisher items wanted Only $29.95 /year for 6 issues or $49.95 for two years Save 37%–48% off the newsstand price! Subscribe and join our thousands of readers at https://tinyurl.com/277vpke9

Civil War Soldiers and Weather on Central Virginia’s Battlefields

By Tim Talbott

Besides commenting on food, perhaps the single thing most mentioned in Civil War soldiers’ letters, diaries, and memoirs is the weather. That is probably not surprising when one considers how much time soldiers spent out in the elements and how much a particular day’s weather conditions might affect their lives and brighten or dampen their morale.

Other than Fredericksburg and Mine Run, the campaigns fought at Chancellorsville, the Wilderness, and Spotsylvania Court House occurred in what are typically mild weather months in central Virginia. However, the stresses of constant maneuvering, and enduring combat, often elevated the soldiers’ sense perceptions of climatological conditions like temperature. Similarly, in the hustle and bustle of campaigning, soldiers often jettisoned equipment that in normal times helped them endure the elements and keep comfortable. Additionally, as battlefield visitors to the Old Dominion probably know, the weather here can change drastically without warning. All these things helped leave strong impressions on the soldiers.

Fredericksburg

In the days leading up to the Battle of Fredericksburg a significant cold snap came over the area. Cyrus Forwood, serving in the 2nd Delaware Infantry, mentioned in his diary that December 6-7, 1862, was “the coldest I have experienced since I joined the Army. Three men froze to death on Picket.”

But soon, temperatures started to climb. J.P. Coburn, 141st Pennsylvania wrote on December 10, “the weather is warm and pleasant today & the snow which has lain for several days is fast disappearing.” Melting snow and thawing earth created seas of mud. Although some histories depict the December 13 battle as cold and snowy, contemporary and many recollected accounts disagree. “The weather . . . was much above freezing point . . . there was no snow on the ground except on the northern exposures and in the woods,” remembered Oregon Foster, 9th Virginia Cavalry. One recording had the high temperature that day as 56 degrees.

Exaggerated accounts of wounded soldiers literally freezing on the battlefield are legend, as the temperature that night did not drop below 40 degrees. However, if not properly equipped, conditions proved uncomfortable for soldiers. For example, Sgt. Charles T. Bowen, 12th U.S. Infantry, described December 13, 1862, as arriving “bright and beautiful,” but, he got cold after the sun went down. “When we were relieved we went back into the city nearly starved & frozen for our blankets were in our knapsack & we had no chance to eat while out,” Bowen wrote.

Chancellorsville

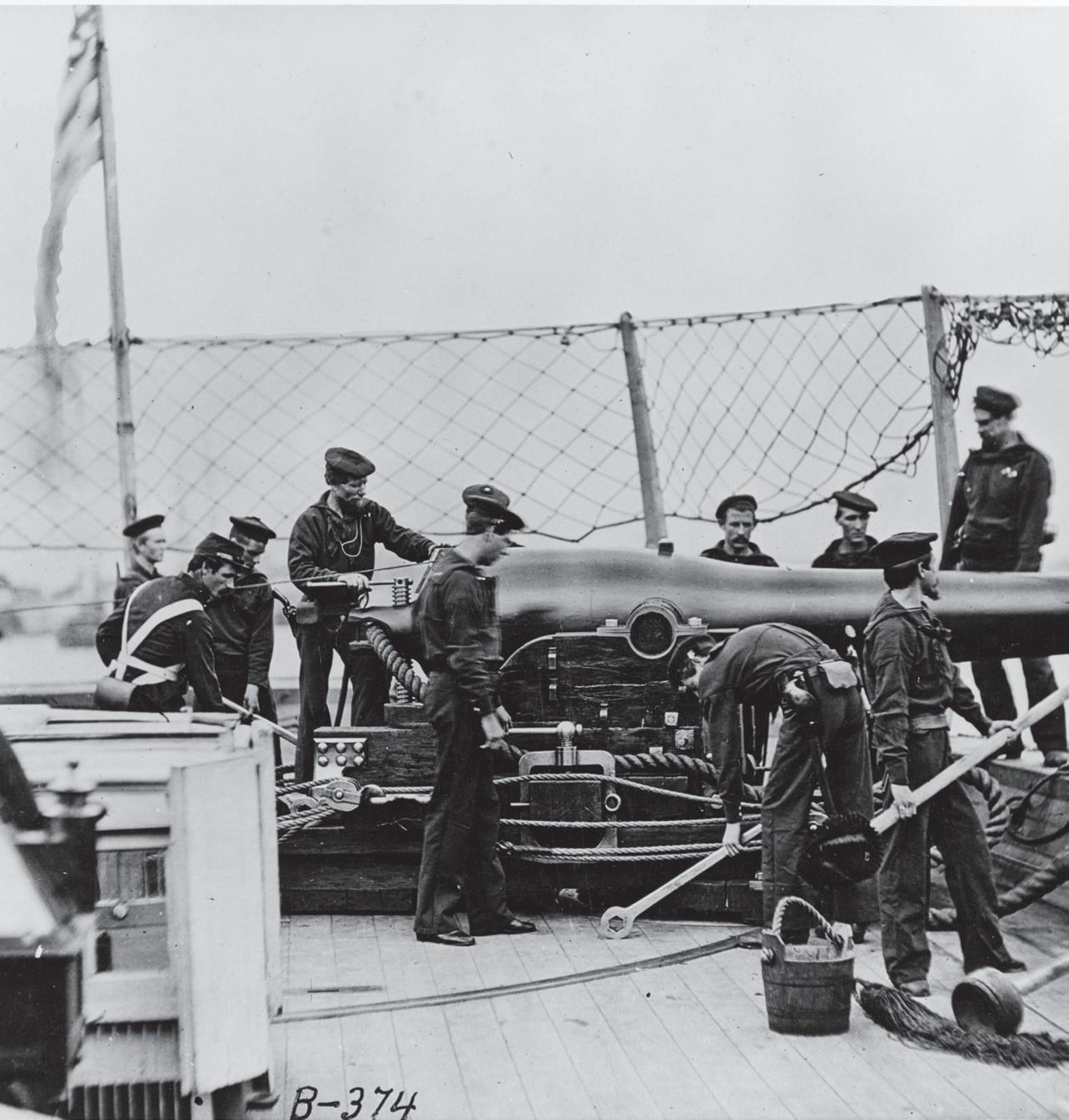

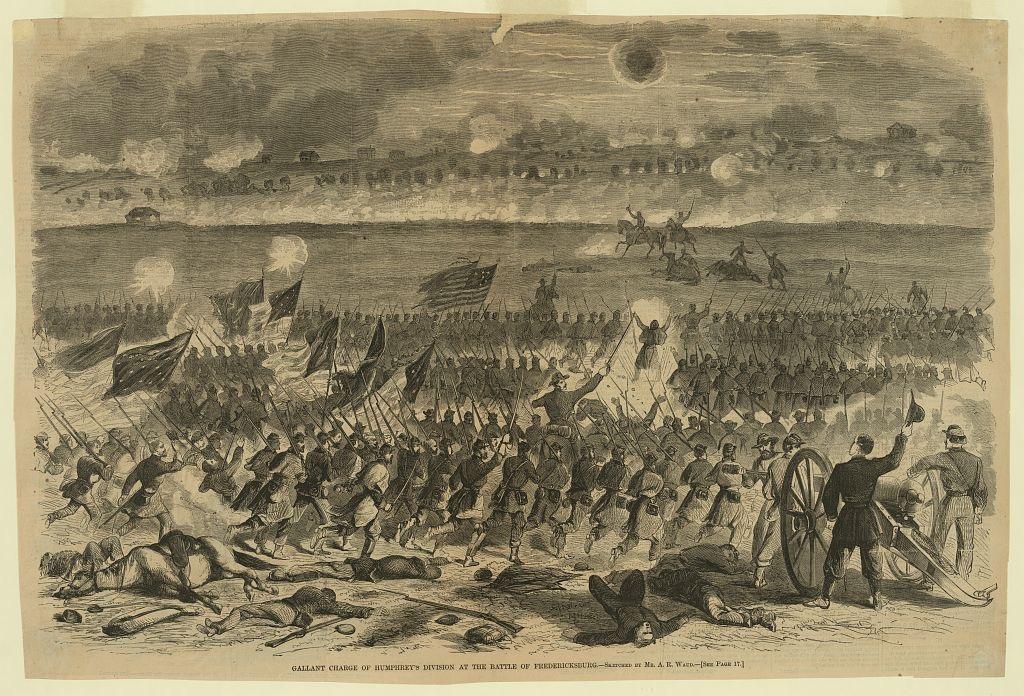

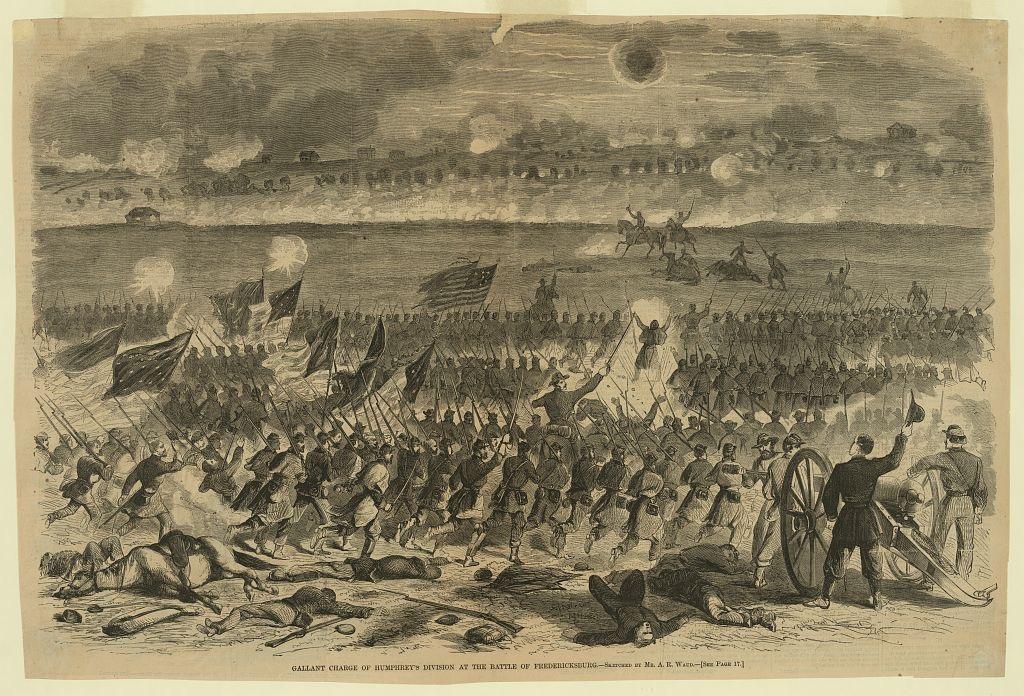

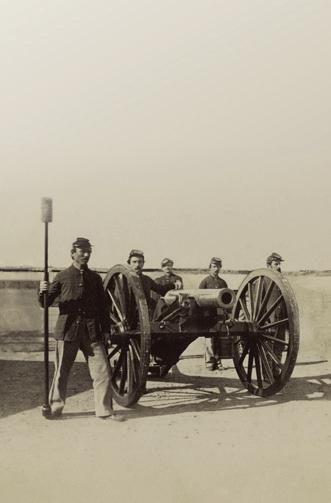

While soldiers commented on extremely cold temperatures in the days before and following the Battle of Fredericksburg, most period accounts note the rather mild weather conditions on December 13, 1862. (Library of Congress)

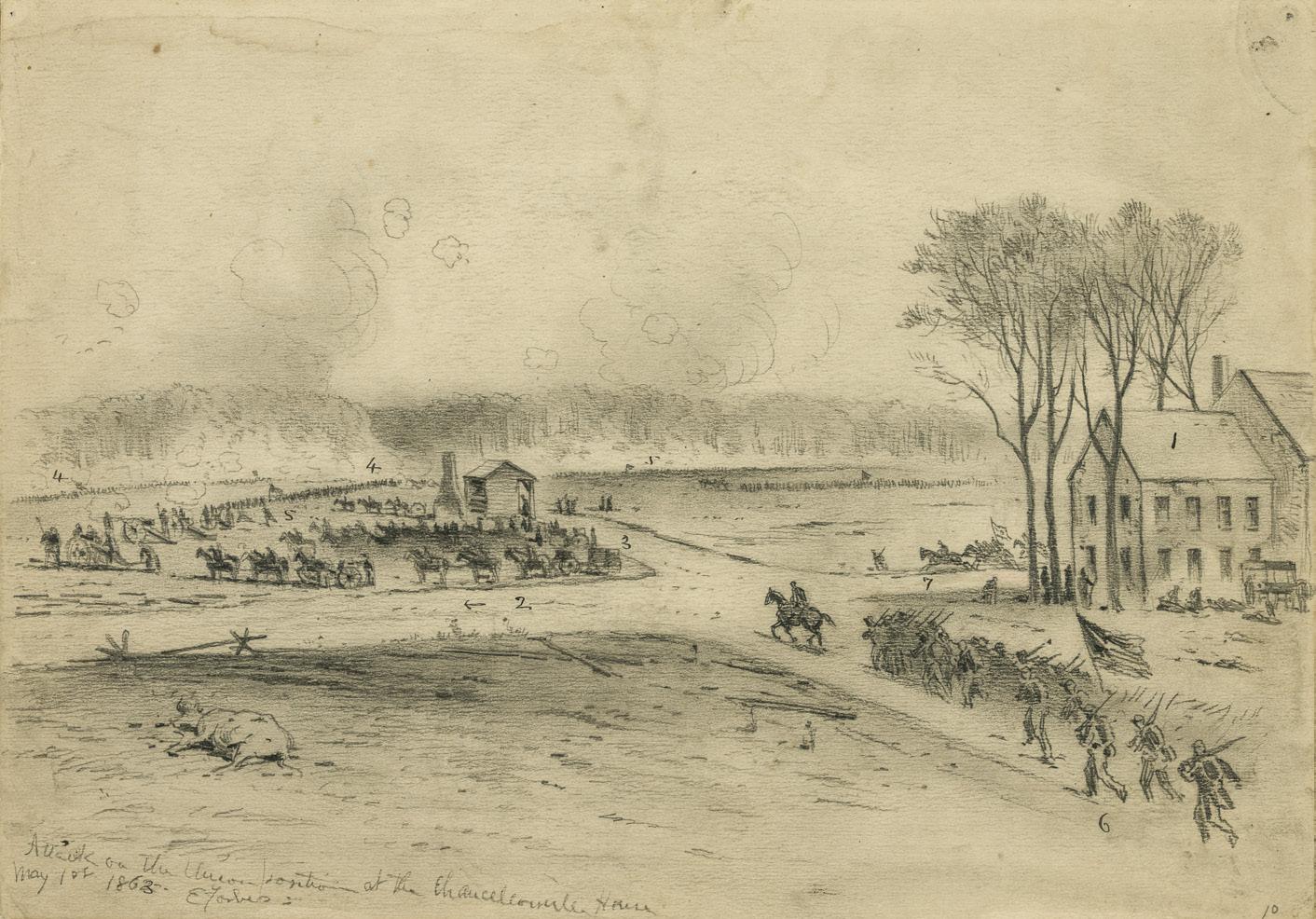

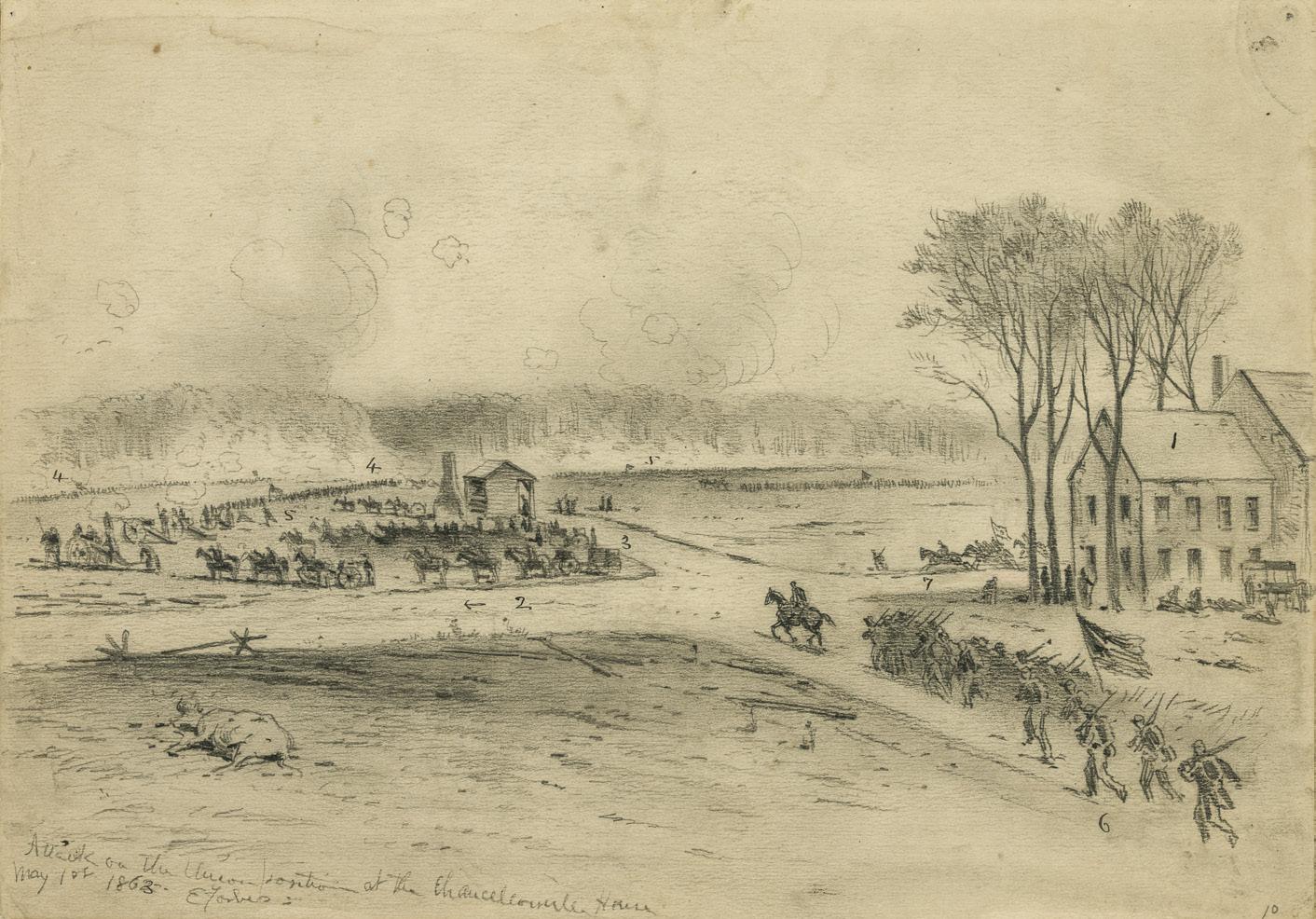

As Gen. Joseph Hooker maneuvered the Army of the Potomac to attack the Army of Northern Virginia, a thunderstorm hit on the night of April 28, 1863. It muddied the roads, which made marching and moving supplies much more difficult. A lightning strike knocked out part of the telegraph line severing communications. The arrival of May 1 though, brought sunny skies and mid70s temperatures. John J. Shoemaker of Stuart’s Horse Artillery referred to it as a “genuine May day.” Capt. Alfred Lee, 82nd Ohio, wrote that on May 2 “the sun dawned clear and beautiful.”

For those like Captain Lee in the XI Corps camps it was a comfortable day. However, for some of Gen. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson’s hard marching Confederates, attempting to get into attack position, “the weather was fine but we suffered for water,” recalled South Carolinian Lt. J.F.J. Caldwell. Detached from the II

29 Civil War News Magazine | May-June 2024

Corps and fighting with Sedgwick’s VI Corps, Maj. Henry Livermore Abbott, 20th Massachusetts Infantry, wrote about May 3rd, “All day there was skirmishing & the heat was terrible . . .” May 3 proved to be the hottest day of 1863 to that point, with the temperature rising to 80 degrees. A bright sun and cloudless day added to the miseries of the combatants.

Following the fight at Chancellorsville, Taliaferro N. Simpson, 3rd South Carolina, wrote to his father, “My shoes are out, and my feet are so sore that I can scarcely walk. We have no tents, and the weather is as cold and rainy as any in winter time.” William White of the Richmond Howitzers concurred in his diary entry for May 5, when he wrote, “This afternoon the rain fell in torrents and soon our trenches were filled with water. Having no tents we were entirely unprotected, and the cold rain perfectly benumbed us.”

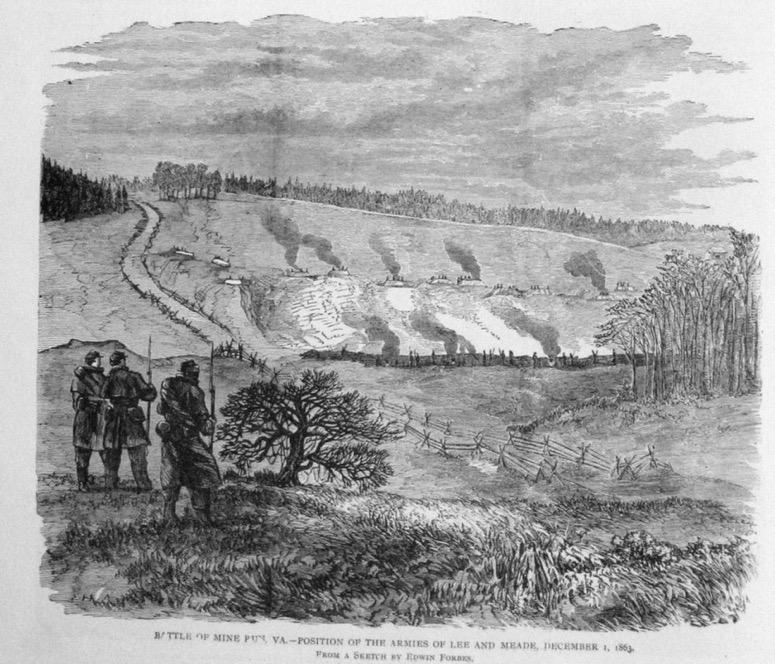

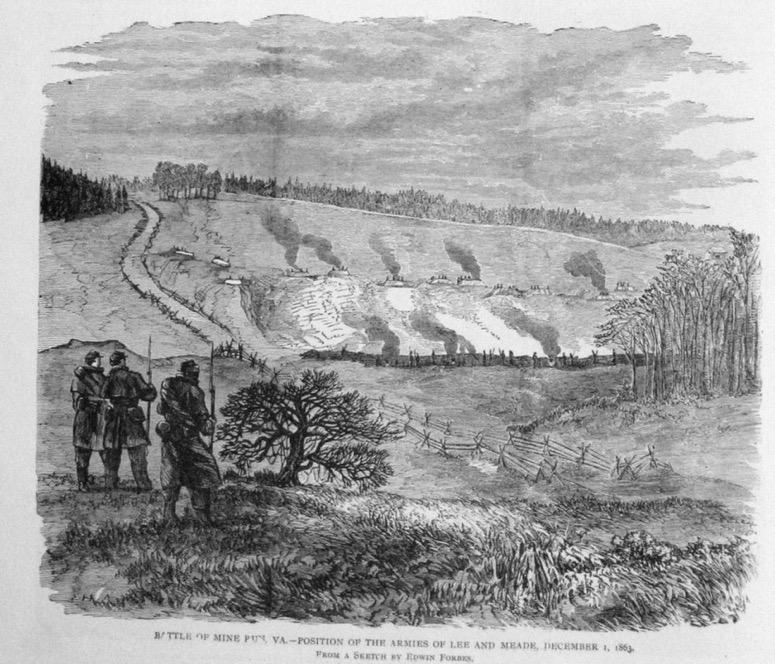

Mine Run