BEST BOOKS 2014

THE RADICALS’ WAR P. 42 REBEL RAIDER OVERSEAS P. 24 VOL. 4, NO. 4

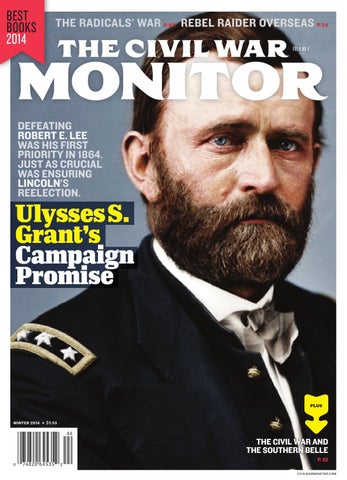

DEFEATING ROBERT E. LEE WAS HIS FIRST PRIORITY IN 1864. JUST AS CRUCIAL WAS ENSURING LINCOLN’S REELECTION.

Ulysses S. Grant’s Campaign Promise

PLUS

WINTER 2014

H

$5.99

THE CIVIL WAR AND THE SOUTHERN BELLE P. 22 CIVILWARMONITOR.COM

CWM14-FOB-Cover-FINAL.indd 1

11/11/14 9:45 PM