KNOT IN MOTION

Jisu Yang

Rhode Island School of Design B.Arch 2021

Jisu Yang

Rhode Island School of Design B.Arch 2021

2

“To compose a finished well constructed poem, the mind is obliged to make projects that prefigure the arrival of the poetic image. But for a simple poetic image, there is no project. The flicker of the soul is all it needed.”

Gaston Bachelard

3

4

TABLE OF CONTENT

1. Acknowledgements

2. Beginnings

3. Thesis Rambling Research

Drawing

Making

4. Final Thesis Rambling

5

1. ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

6

The thesis acknowledges all the contributions from family, colleagues, critics and professors.

I thank Jess Myers for giving me both freedom and discipline for allowing me to dance during thesis.

I thank Jack Li, my motivator, supporter, critic, and a best friend for always being there when I need support and giving me safe space to ramble my thesis.

I thank my parents for trusting me and supporting me for completing the arduous degree in RISD.

I thank my BEB cohort: Kunyue Qi, Jen Zhang, Pablo Herraiz Garcia de Guadiana, Shivani Agarwal, Piper Matthew, Namrata Dhore, Alex Kern, Sam Capozza who resisted pandemic together in studio and has been a constant support for each other just by being physically present and spark conversation with beer and fried chicken.

I thank all my zoom critics, Laura Briggs, Peter Tagiuri, Sabriyah Rashied, Shoujie Eng, Jessica Luscher, Kyu Sung Woo, and Danielle Oh who opened my thesis in new perspective.

Lastly, I give special thanks to my endearing advisors Silvia Acosta and Kyna Leski who flickered the soul of my project in igniting the poetic image.

7

1.0 Acknowledgement Jisu Yang

2. BEGINNINGS

8

The thesis imagines how architecture becomes a language for creating empathy for others’trauma. The thesis employs the language of Korean shaman’s ritual and reimagine how architecture creates space for the ritualistic performance that alleviates pain of individuals who have experienced traumatic events in Korea. The cultural significance of the work refers to the concept of “恨” (Han) or form of resentment. As the form of pain is prolongly suppressed in the nation over time due to poverty, colonization and national separation, the ability to elucidate pain is more and more lost. As a way to re-define the language of trauma, the thesis intends to release the pain of others by securing the space for ritual that creates performance for the victims and the dead.

The etymology of ritual comes from 1560s French: ritualis, rite, implying an action of ceremonial practice for the body. In the ancient Korean language, the ritual is translated as “意識” (Eui - Sik), which translates to know and to remember. Ritual combines two words from two different cultural contexts,

fundamentally implying the act of remembering through motion. This thesis intends to translate the dancing language of the Manshin’s ritual into a memorial space that allows the victims and the visitors to remember and honor past one’s grief.

Manshin, a Korean shaman, is a figure of the spiritual healer who conducts rituals, which are referred to as kut. Kut is where the Manshin listens and relieves one’s trauma through creating performances. As both a heritage of national identity and memory of suppression, a Manshin’s ritual practice connects to the concept of Korean trauma or Han (恨). Manshin’s ritual is designed as a celebration of the past life of a dead spirit. Singing, dancing, and walking, the practice uses gestures of “miming” to bring both God and the ghost into space. The practice is customized based on the story of an individual’s trauma. Despite existing since the origin of the country, Manshin’s ritual, or kut, has changed over time due to foreign intervention that negatively altered the public’s perception of this national ritual. Mansin were first stigmatized by British and American travel writers

when Christian missionaries first landed in Korea during the 1890s . They referred to Mansins as female shamans who practiced “devilworship” and spread superstitions. During Japanese colonization which began in 1910, the Mansin’s practice continued to suffer from strong political suppression, shrinking their practice even more. As shown in the film “Manshin,” directed by Chankyung Park, the Mansin Suffered from constant exploitation, violence from soldiers, and strict surveillance.

9

Beginnings

2.0

Jisu Yang

10

3. THESIS RAMBLING

11 3.0 Thesis Rambling Jisu Yang

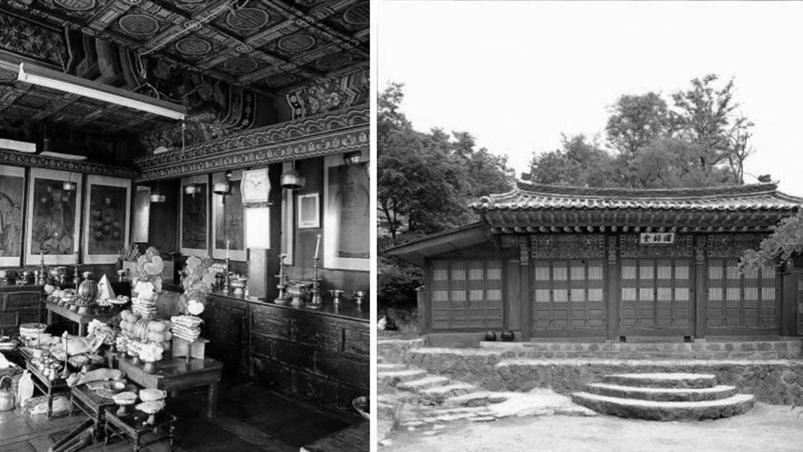

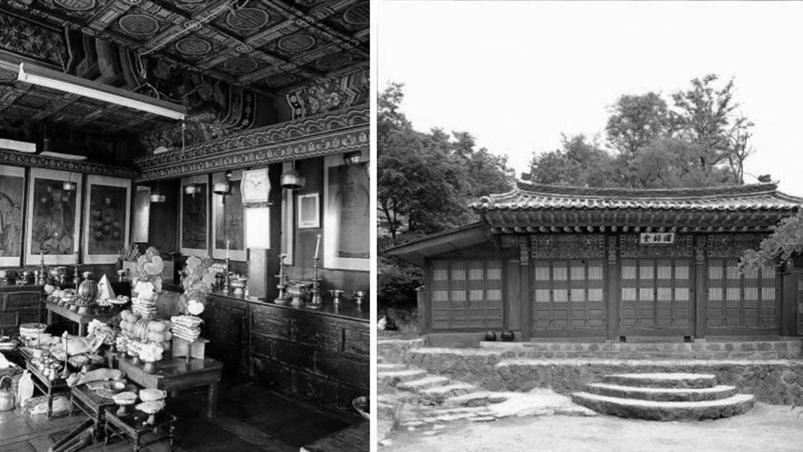

Before Korea was brought to modernity, Manshin’s practice was considered as both spiritual healer and a public performer who would practice in open squares or sacred shrines that were open to different people depending on the type of ritual. Yet, after 35 years of colonization, their rituals slowly shrunk their size to avoid the eyes of surveillance, and eventually, Mansins practiced in their own sub-basement homes and only accepted a couple of people at a time when practicing. Even though Japanese colonization ended after 1945, cultural stigma over Manshin continues to exist today, they are seen as one spreading superstitions or false beliefs.

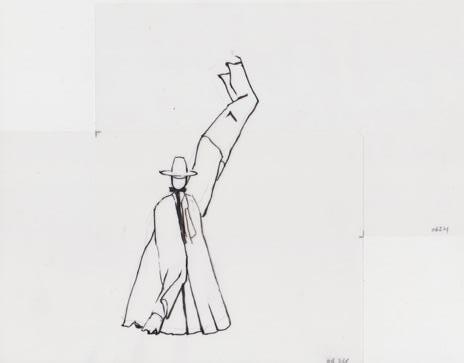

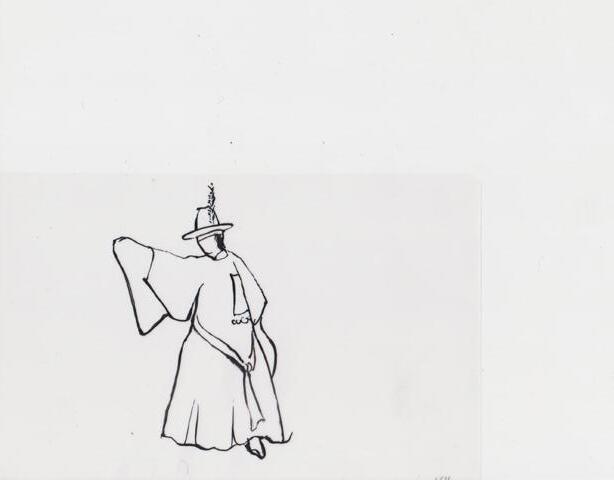

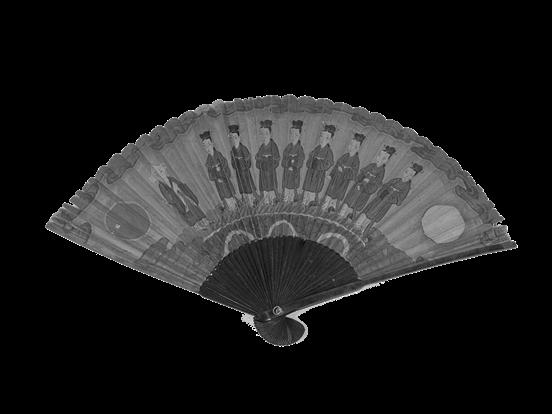

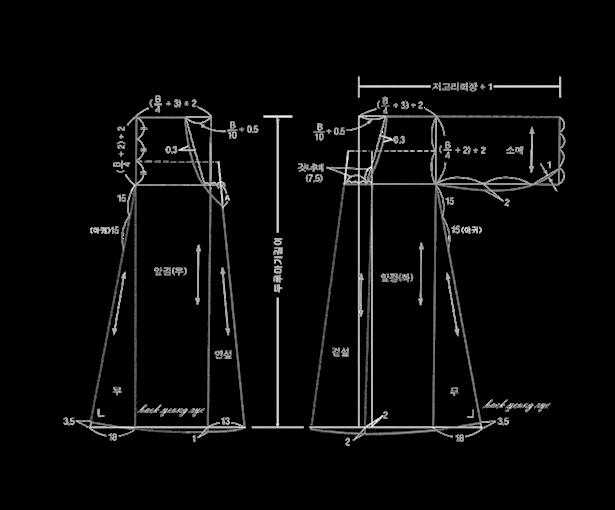

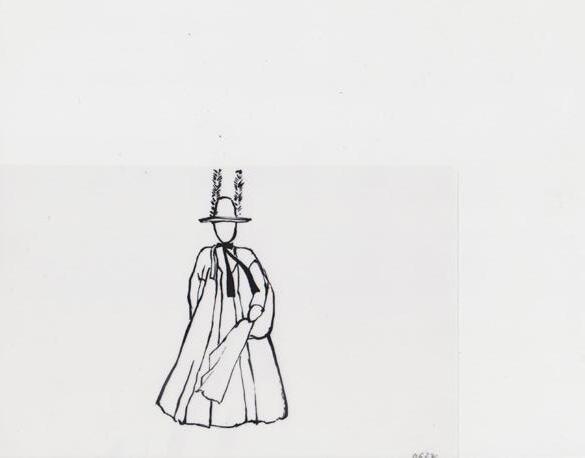

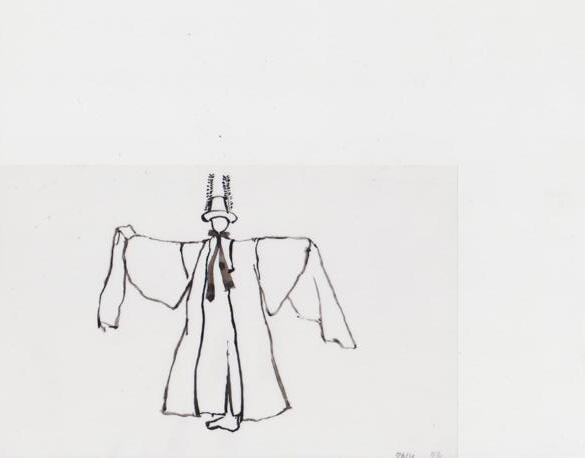

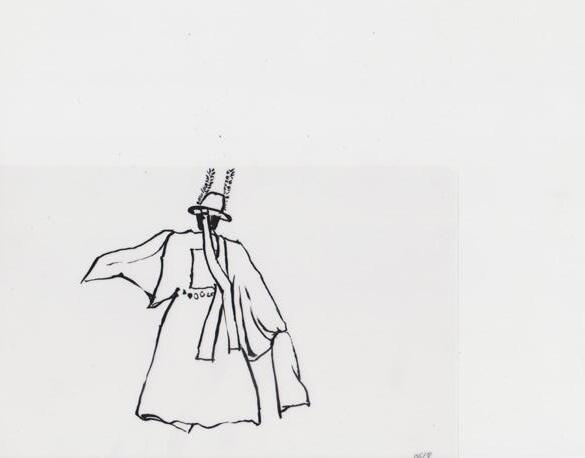

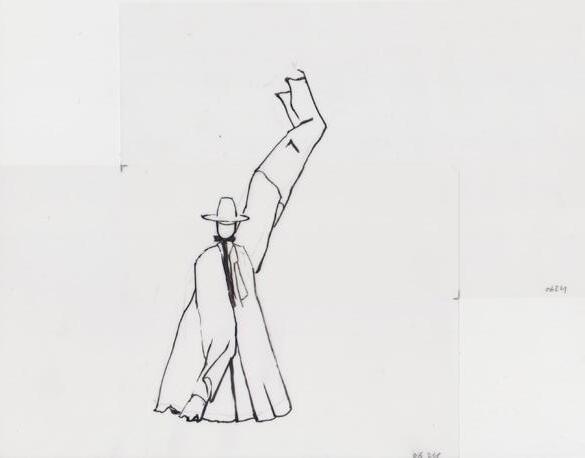

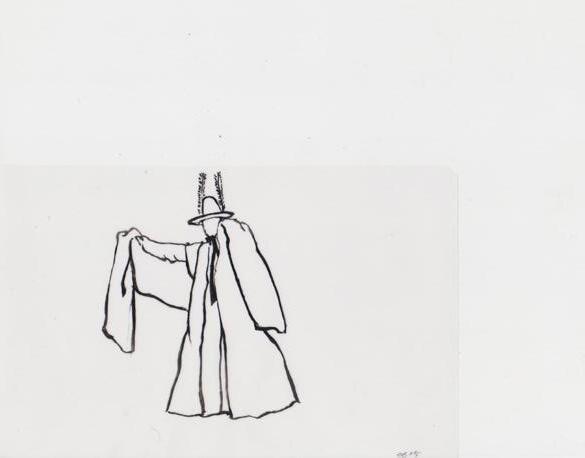

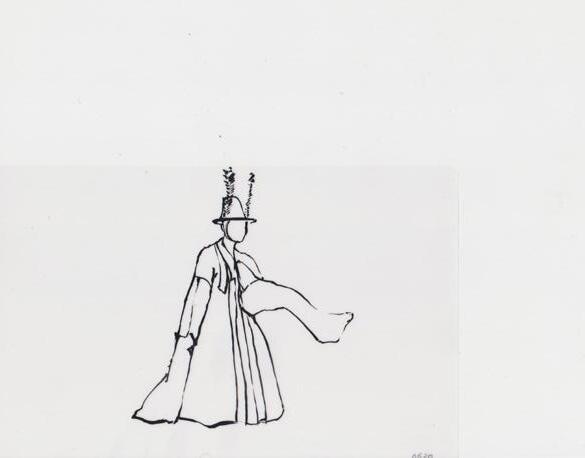

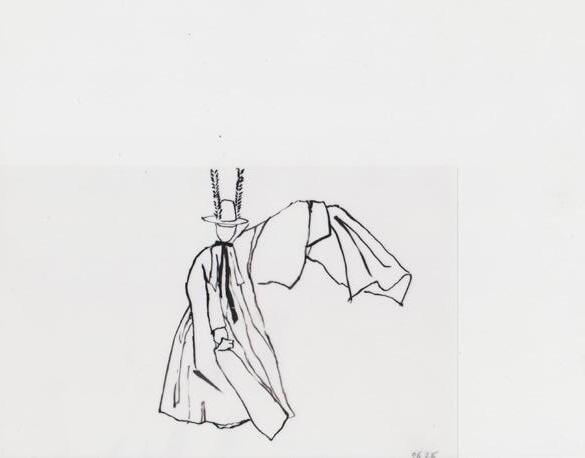

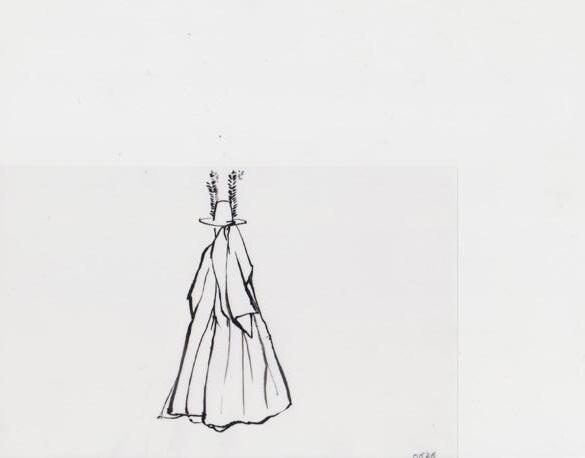

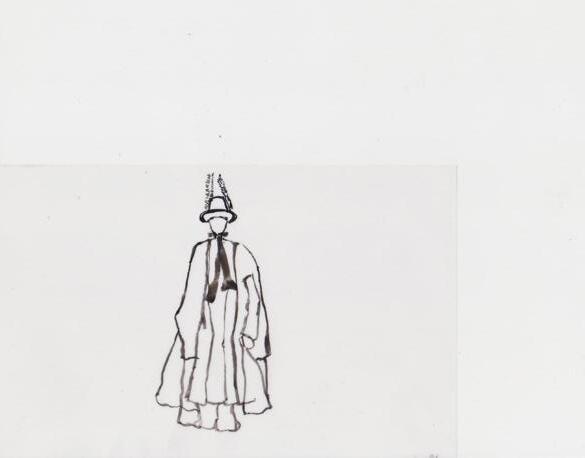

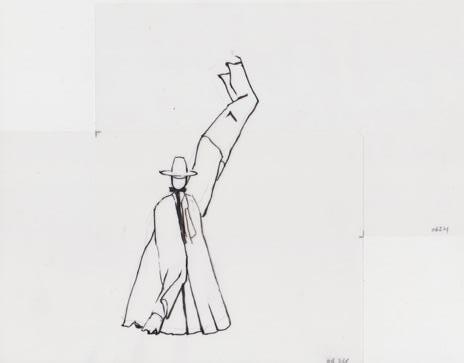

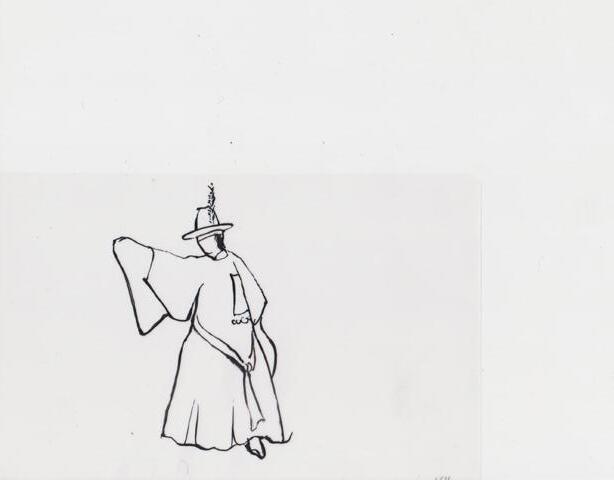

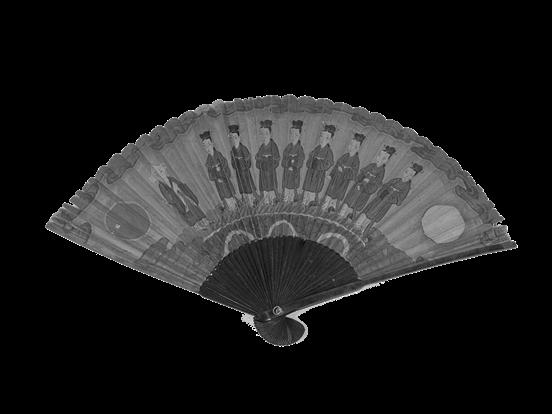

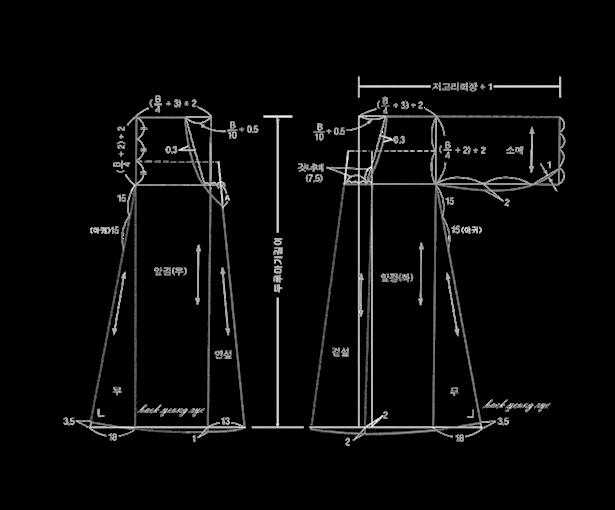

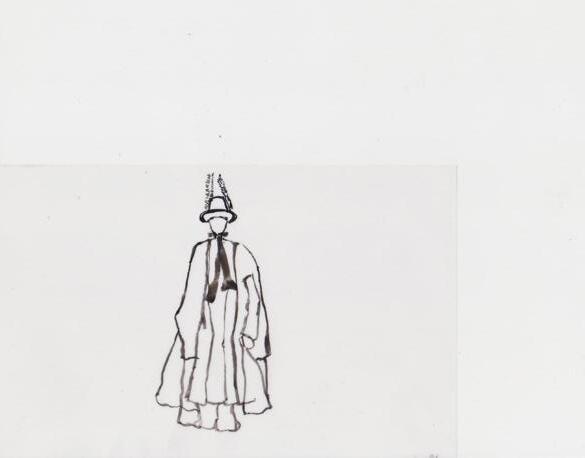

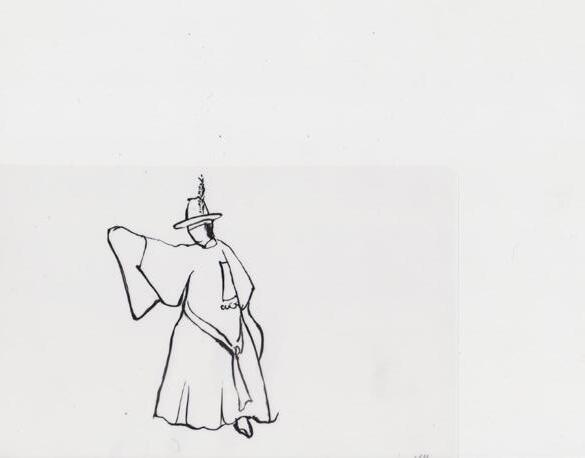

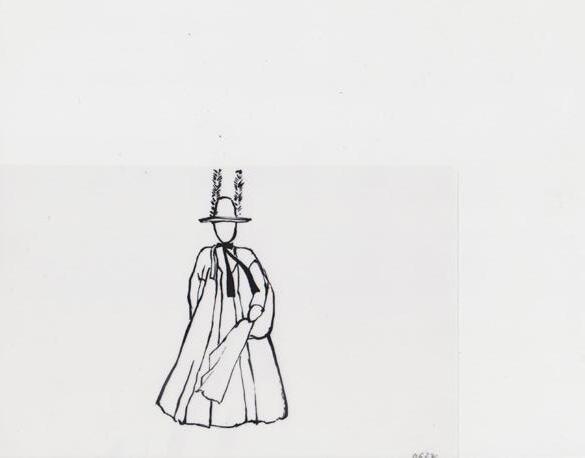

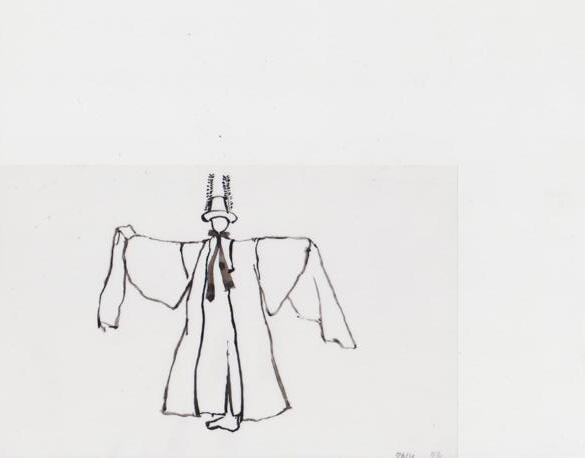

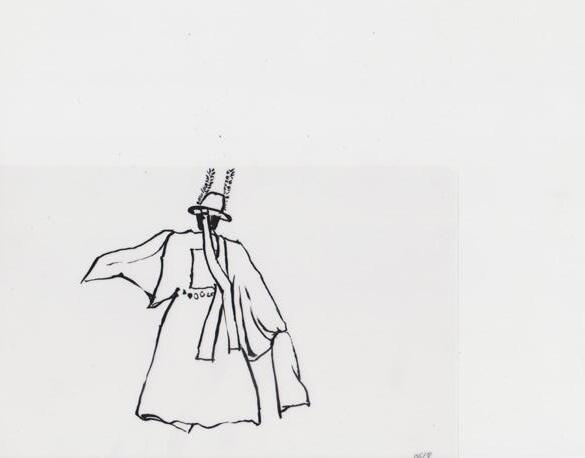

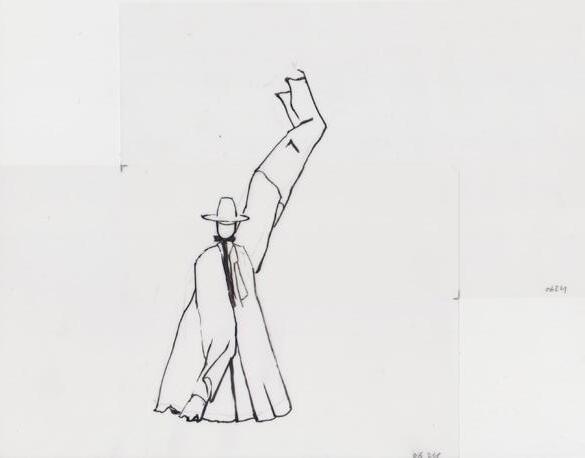

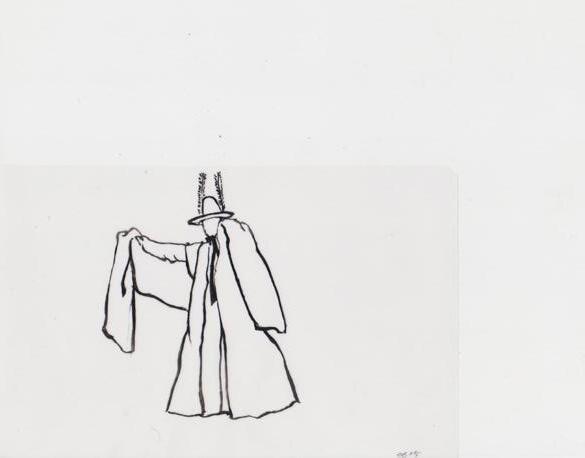

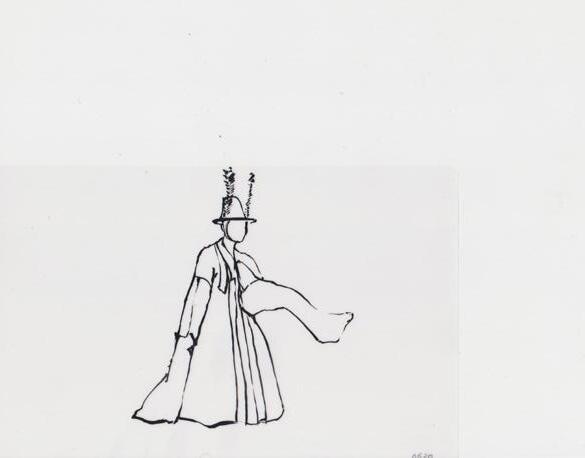

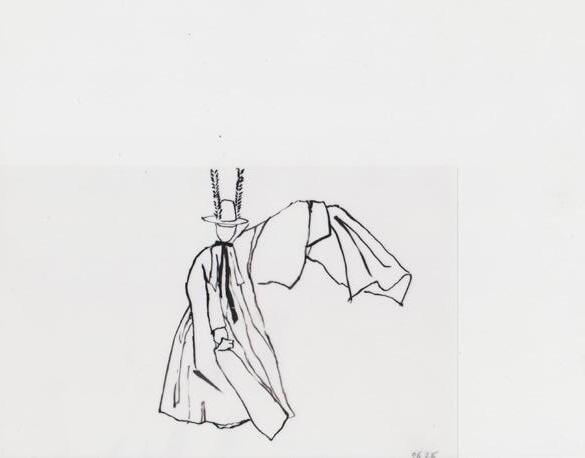

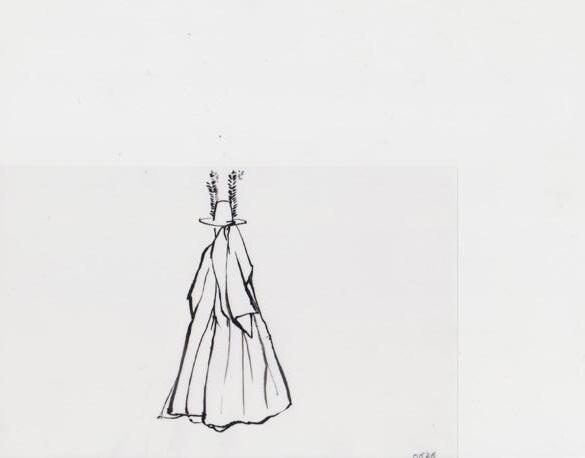

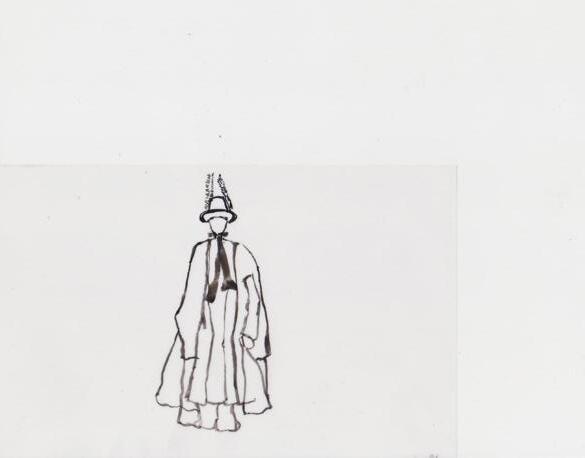

The Manshin’s dance also referred to as “Sal-pul-ii” contains a symbolic gesture of embodying and relieving other’s trauma. With a white hat and dress, a Mansin wears

12

3.1 Research Understanding Ritual

Choseon Dynasty 1392 - 1897

Japanese Colonization 1910 - 1945

Contemporary - Present

Kendall, Laurel. Shamans, Nostalgias, and the IMF: South Korean Popular Religion in Motion.

a traditional costume for performing their ritual ceremony. The costumes have elongated sleeves which enable Mansins to make a particular motion of tying and untying with their sleeves as part of the dance. Through constant tying and untying the knot in accordance with the slow and steady music, Manshin makes gestures of relieving one’s trauma. In other words, the design of the costume is the smallest scale of architecture that creates a motion of empathizing grief. Essentially, Manshin’s ritual is a mode of both honoring and remembering the trauma.

13

Jisu Yang

Rambling

3.0 Thesis

14

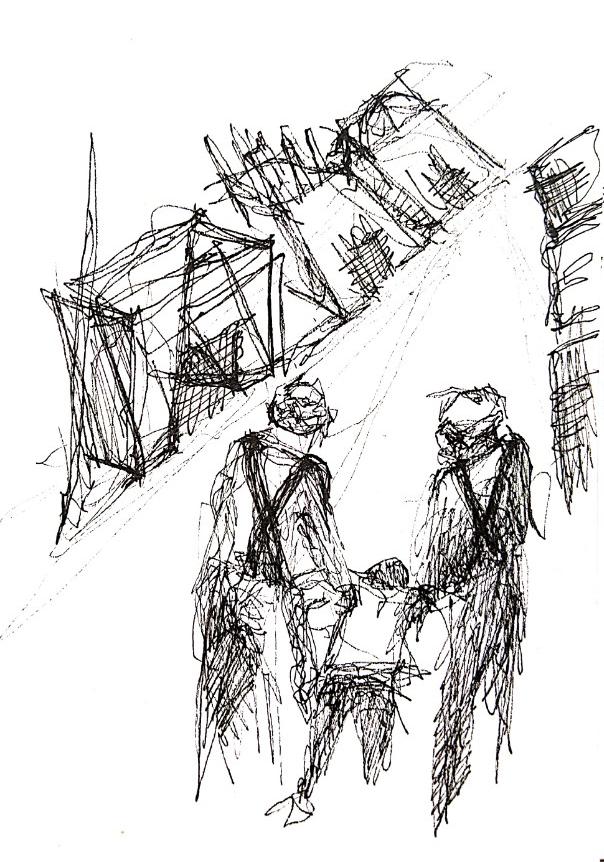

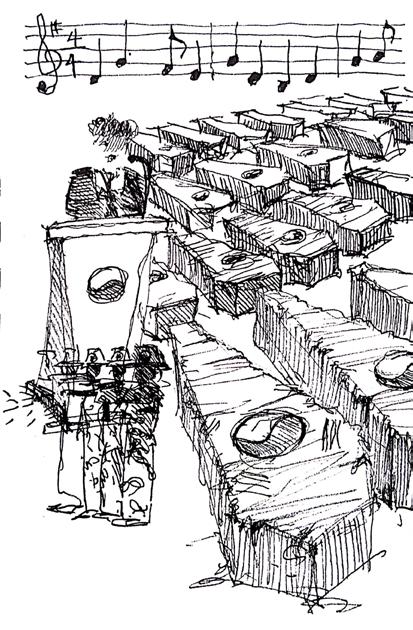

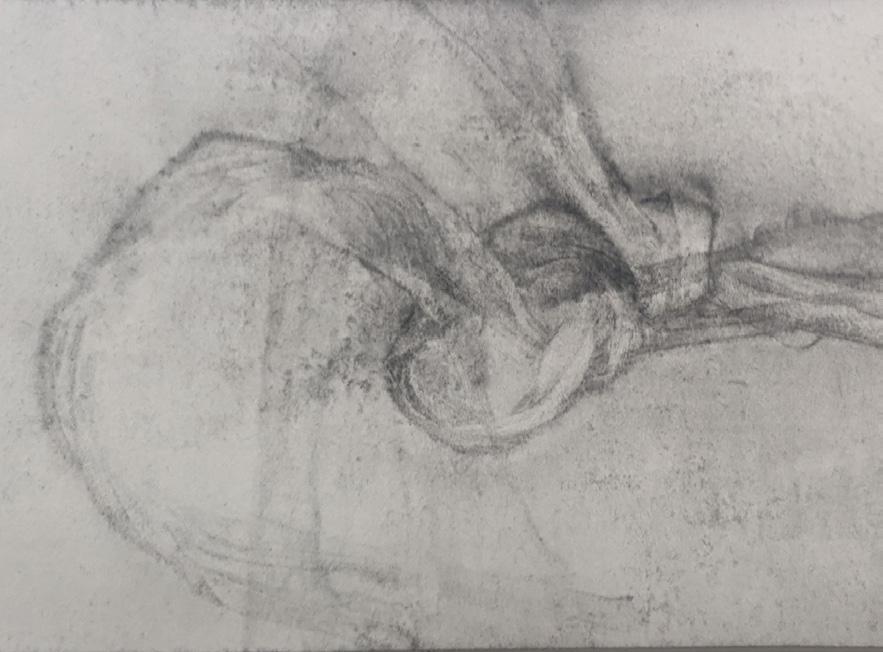

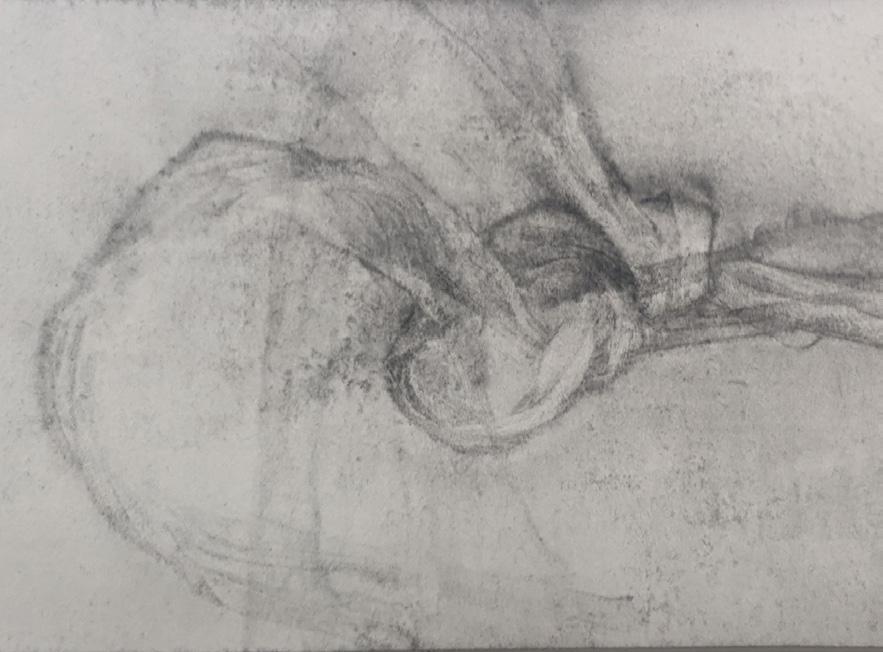

3.2 Drawing Understanding Ritual

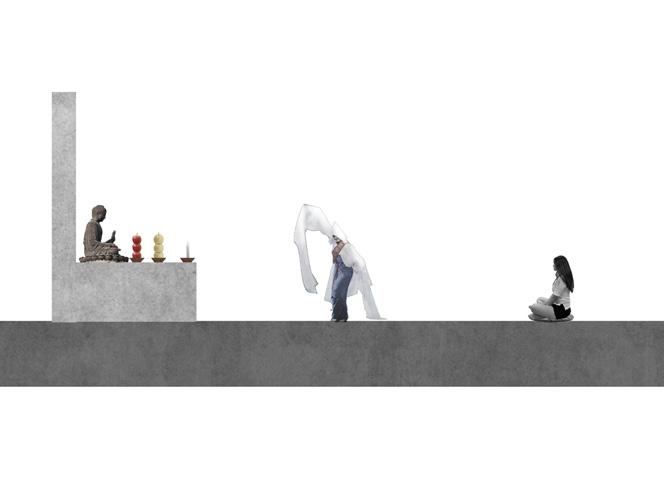

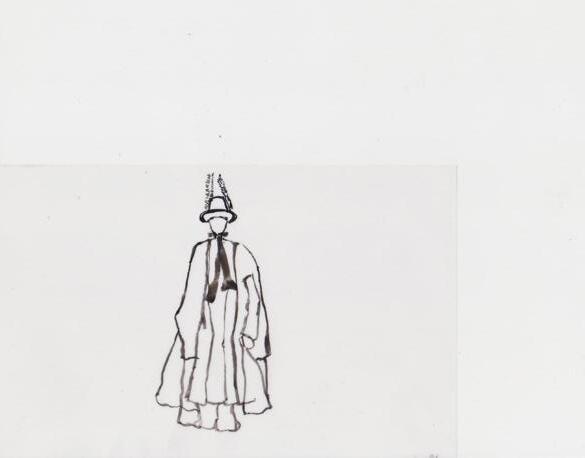

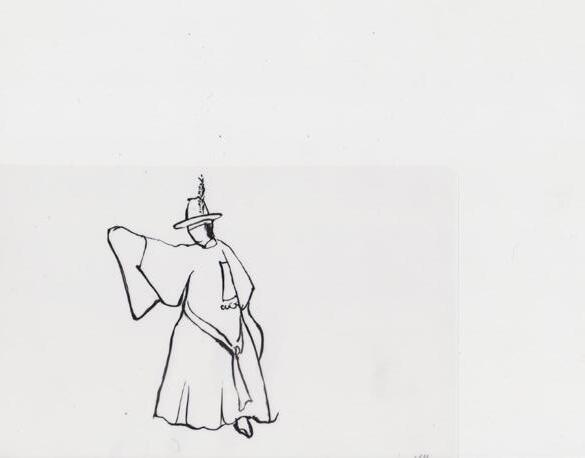

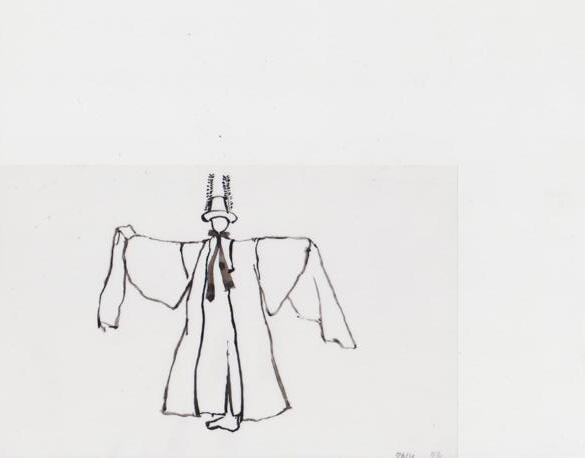

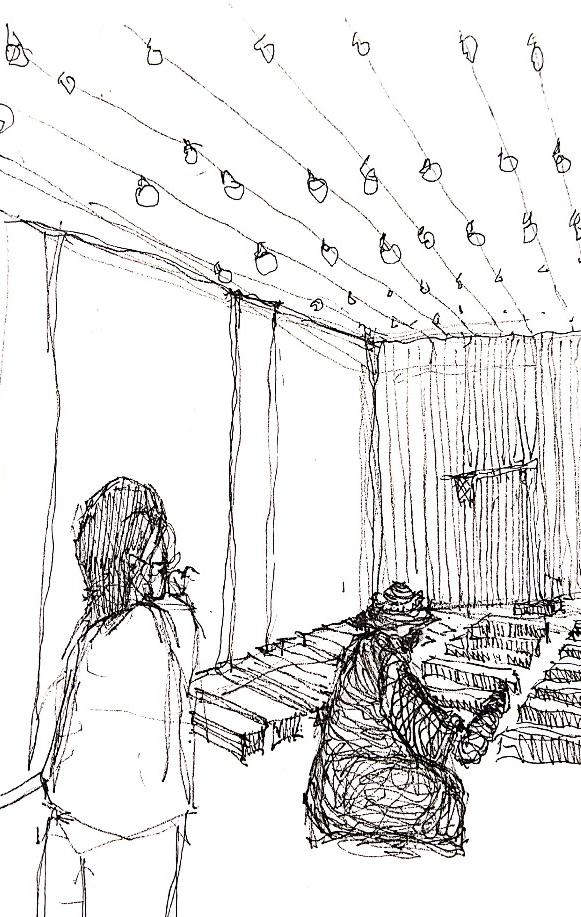

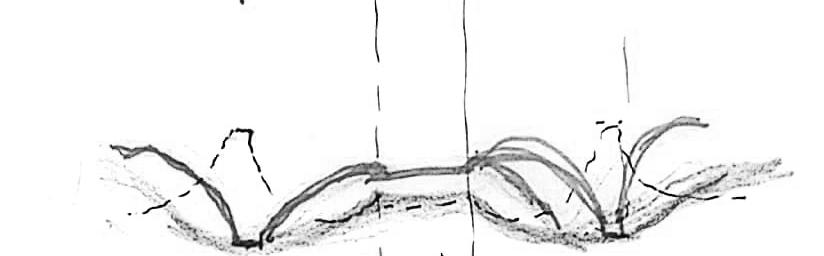

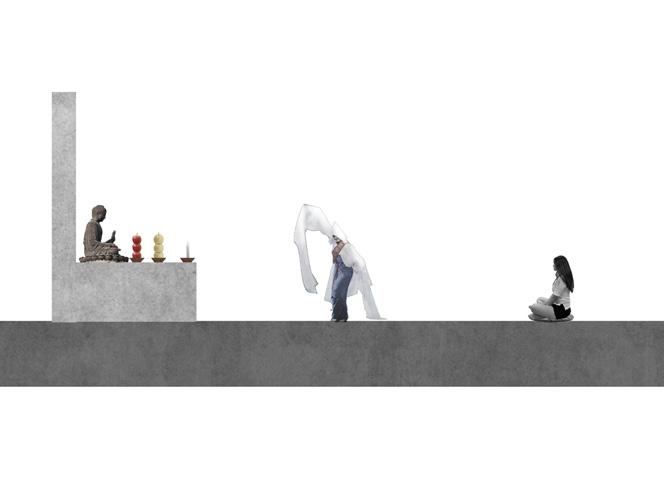

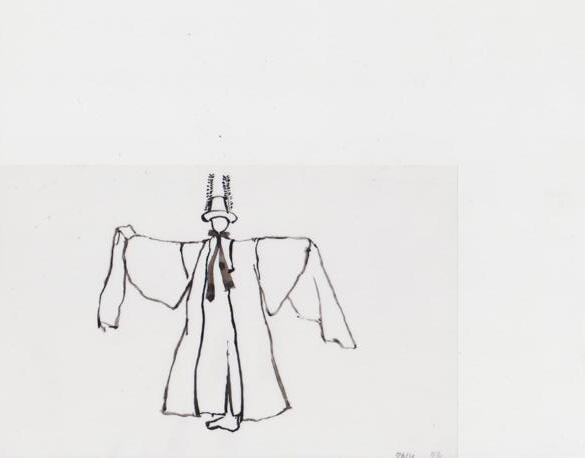

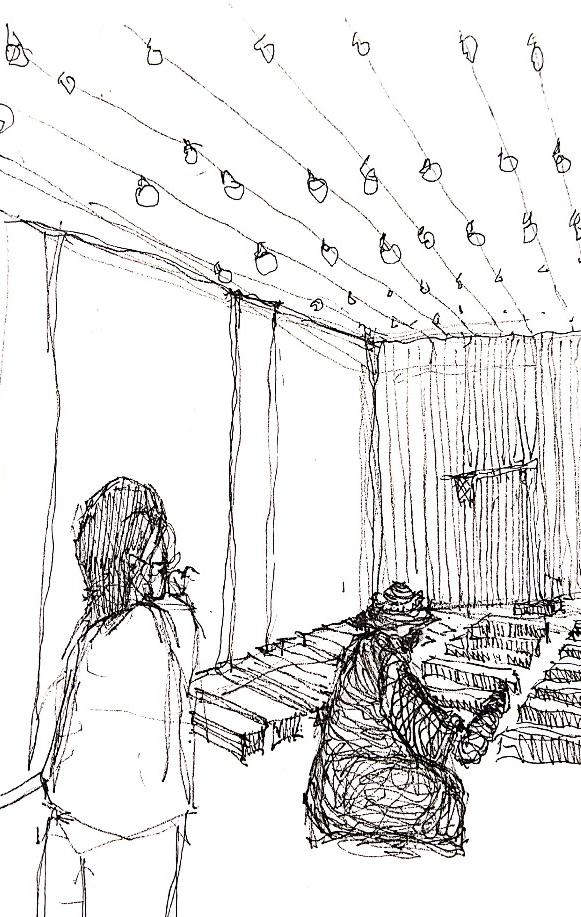

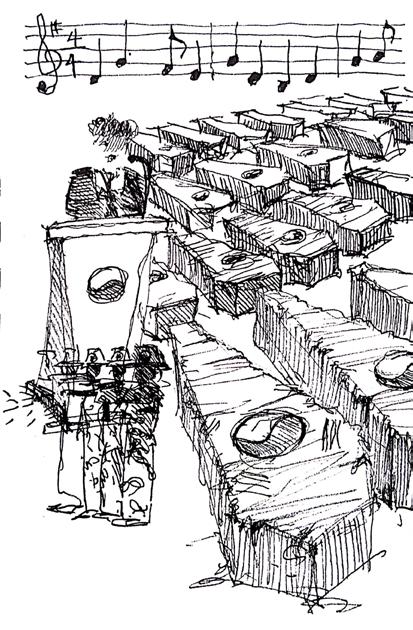

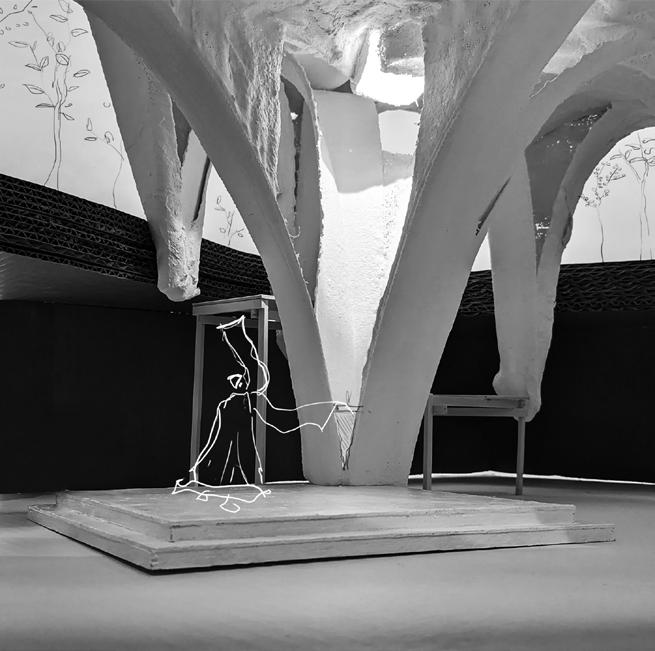

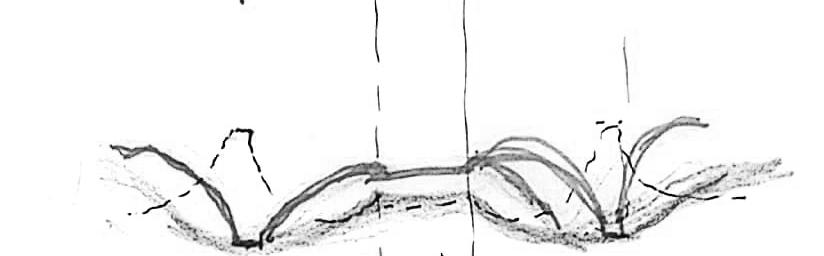

Mansin is a Korean traditional shaman who performs rituals to assist clients who experienced extreme loss of loved beings. The structure of her ritual includes altar, performance stage, and the seating for the client. The language of her dance is fundamentally about making and unmaking the knot in motion by twisting elongated arm and cross into the center and reverse the loop. Through capturing each frames of motion in drawing animation, the thesis takes knot as a protagonist for developing formal gesture for the proposed pavilion.

15

Altar / offering

Mansin Client

Jisu Yang

3.0 Thesis Rambling

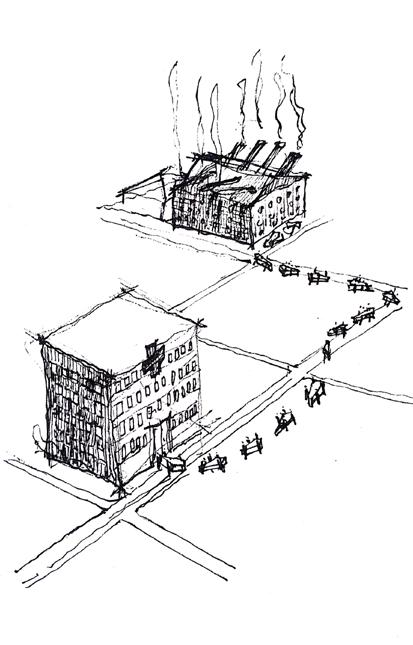

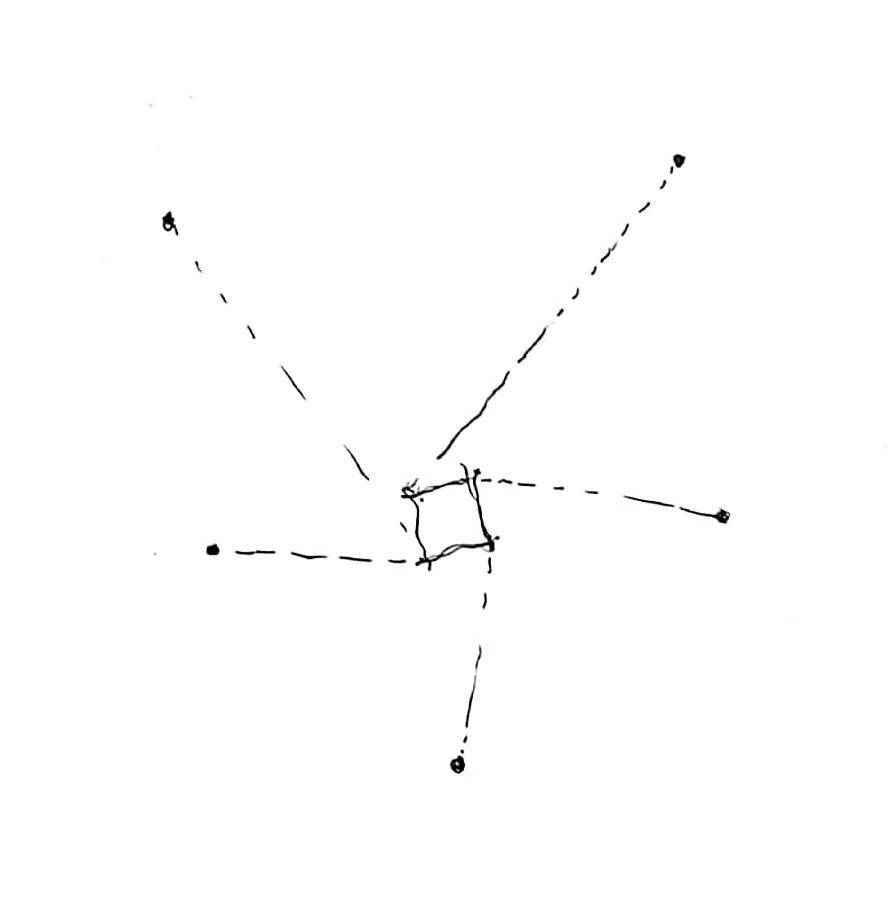

3.2 Drawing Understanding Site

16

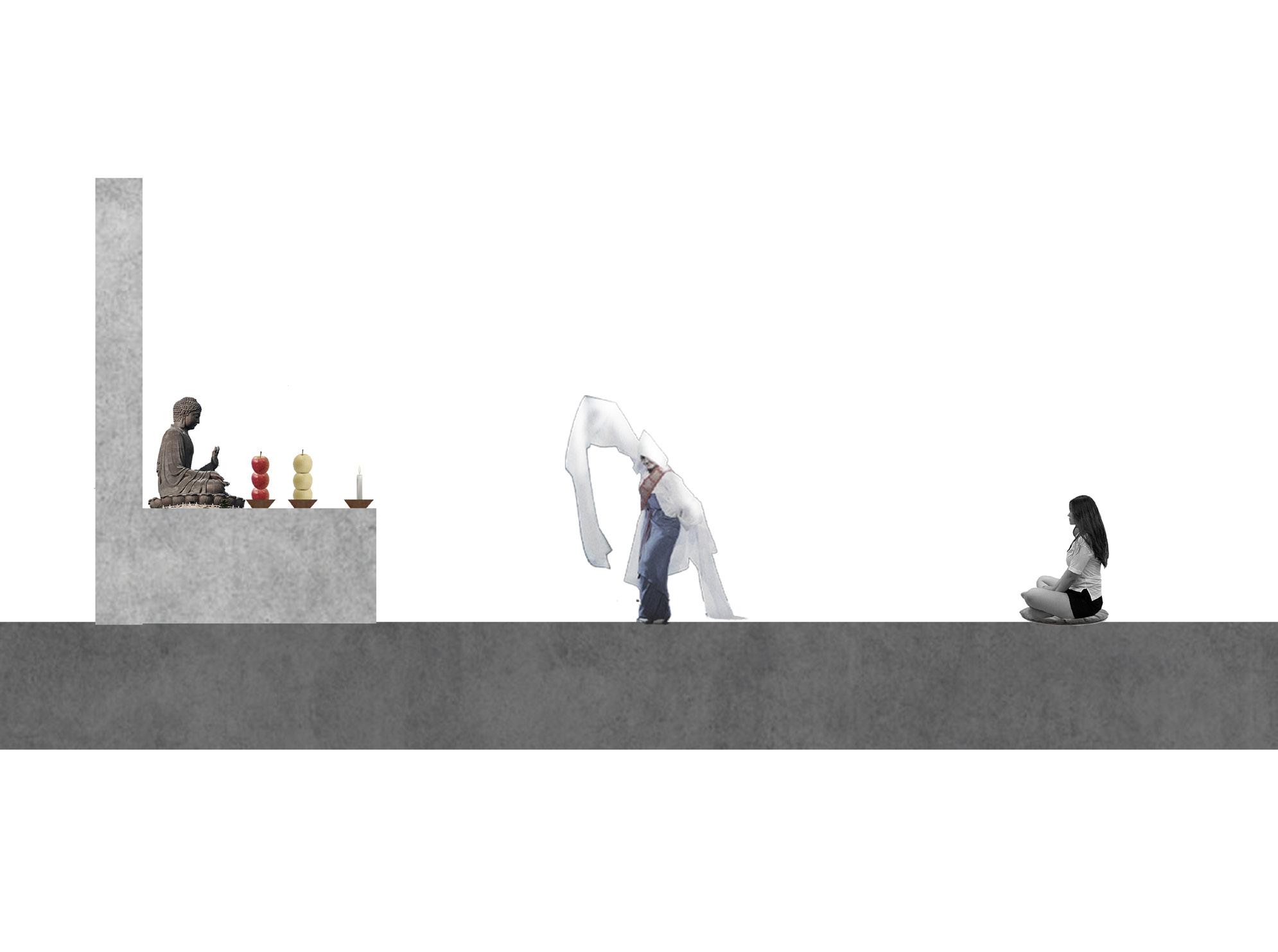

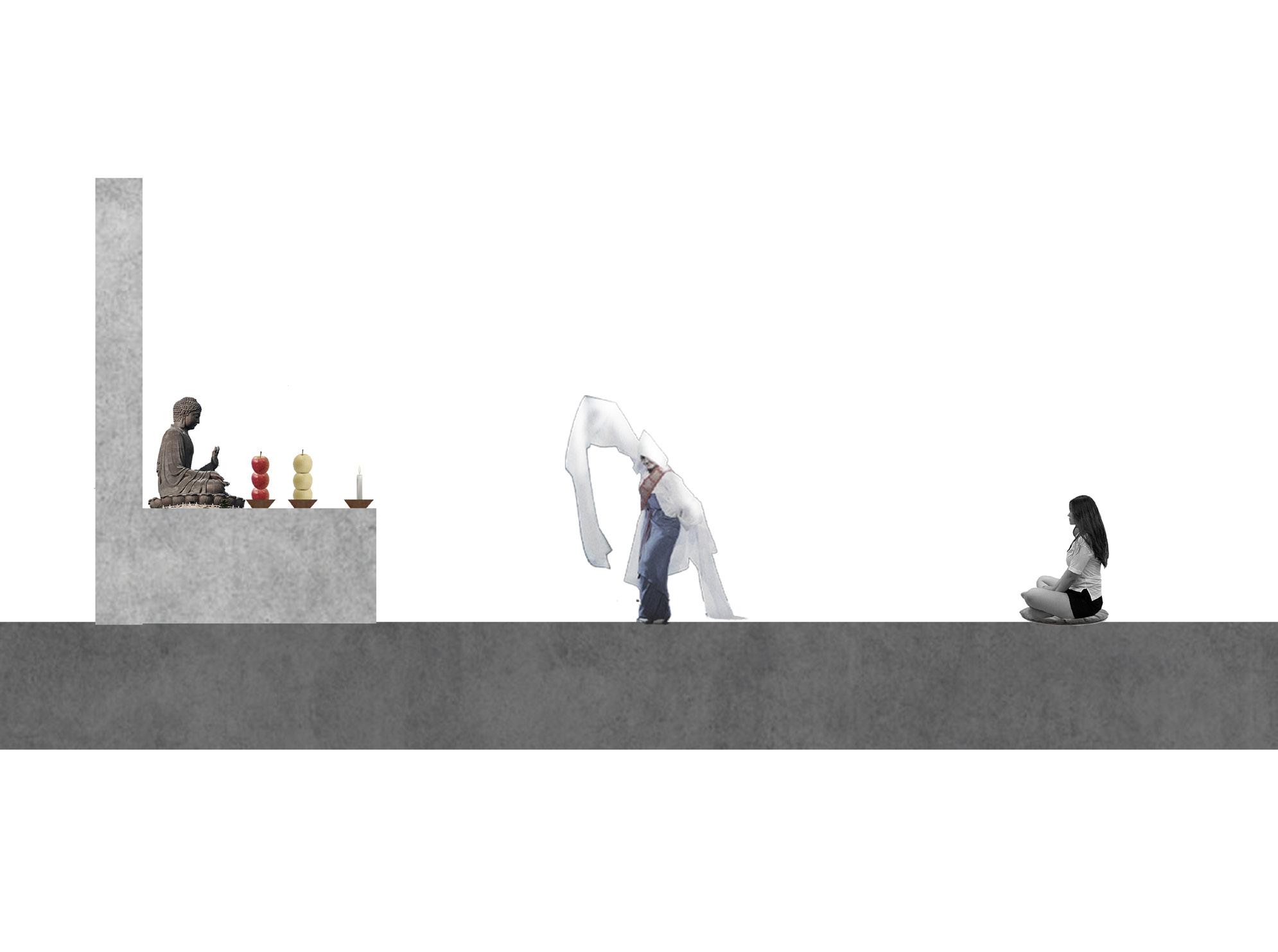

Gwangju, South Korea

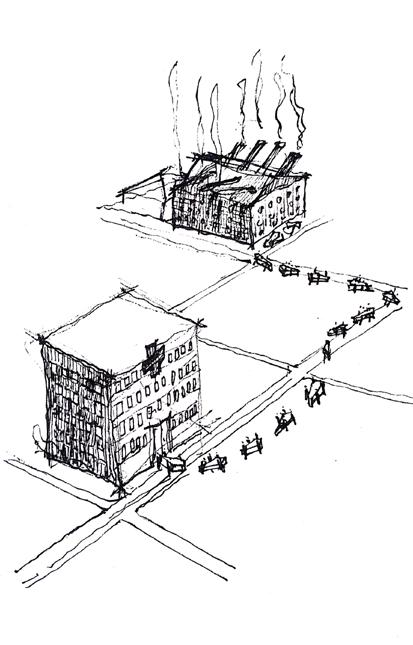

In pairing with Mansin’s ritual, my site is a trauma city of Gwangju where more than 5000 students, professors, and people on the street were killed for participating in a protest to fight for democracy and liberty. This tragedy occurred in 1980 May 18th in the South of Korea, Gwangju near state provincial office.

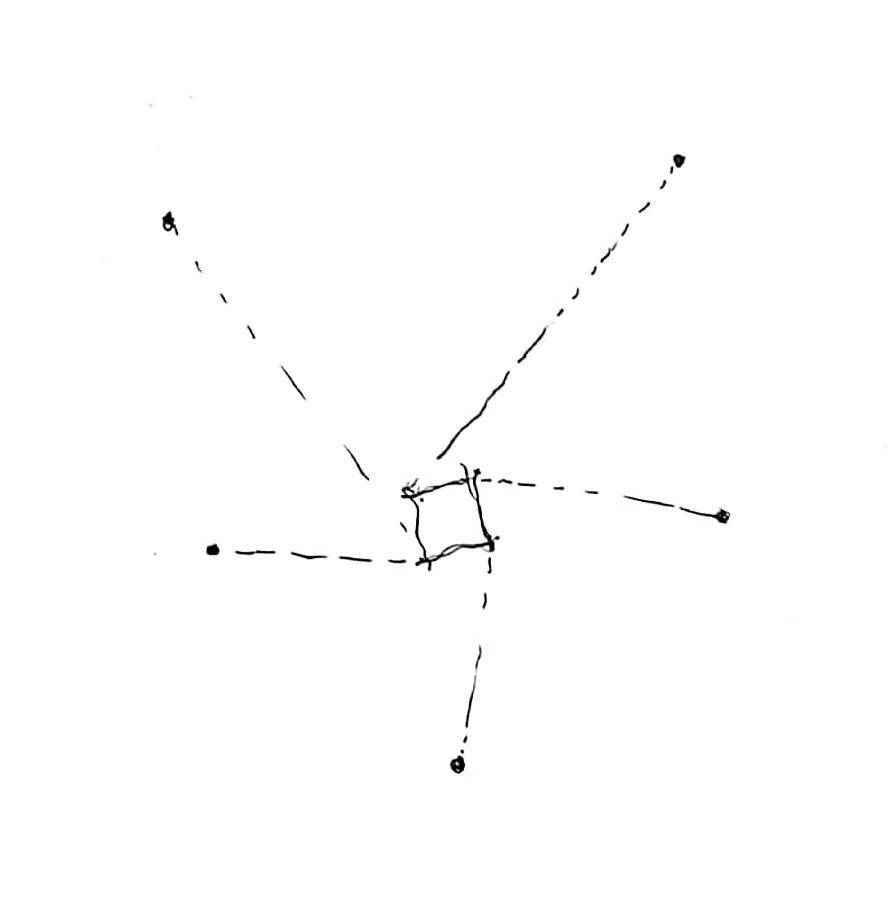

This chosen site is may 18th memorial park in Gwangju that has two axis of entry. The traditional buddhist temple from the South ahd existing memorial square from the North.

17

Jisu Yang

Gwangju 5.18 Memorial Square

3.0 Thesis

Rambling

18 3.2 Drawing

Understanding Pain

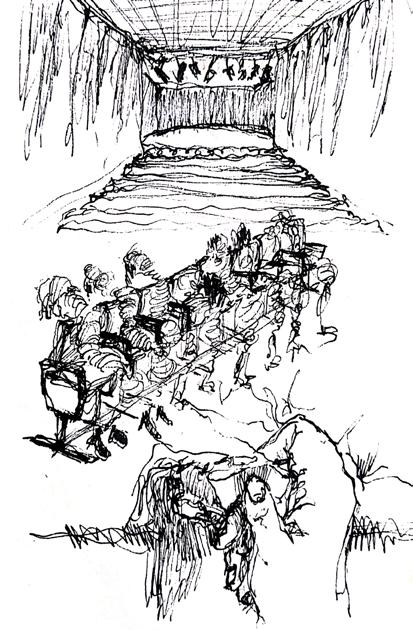

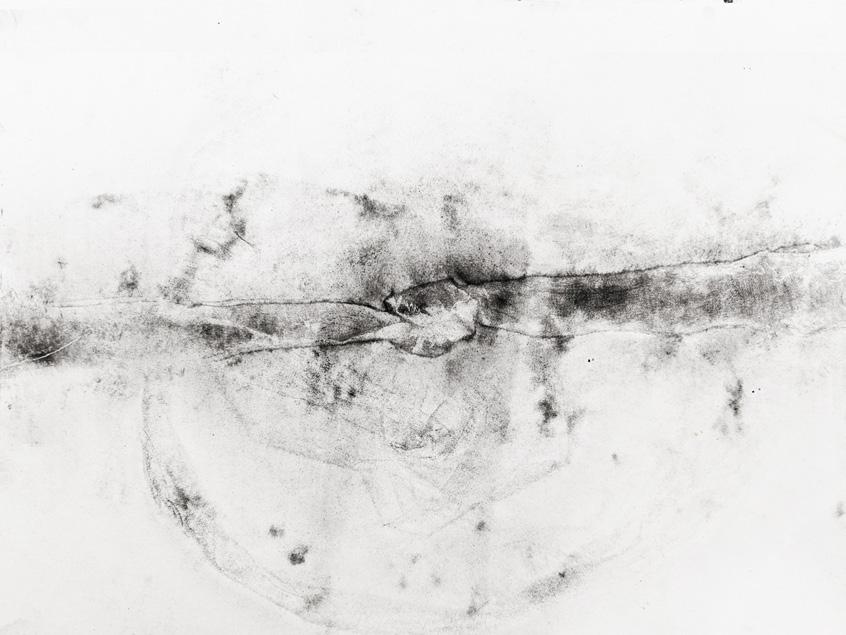

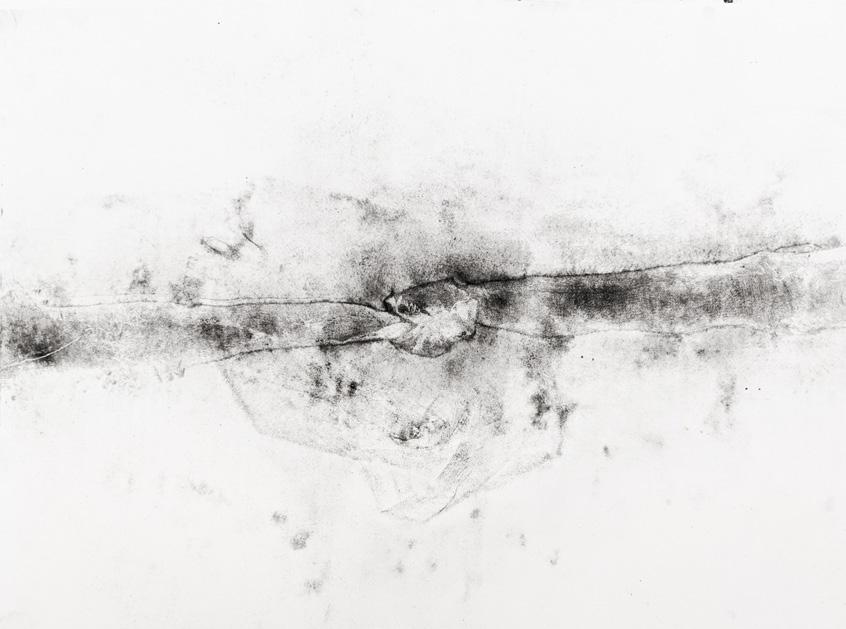

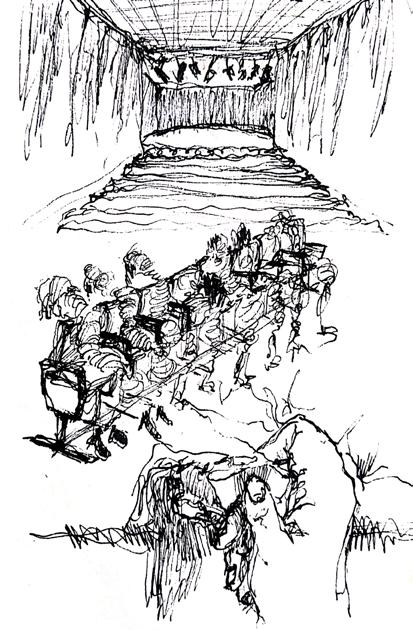

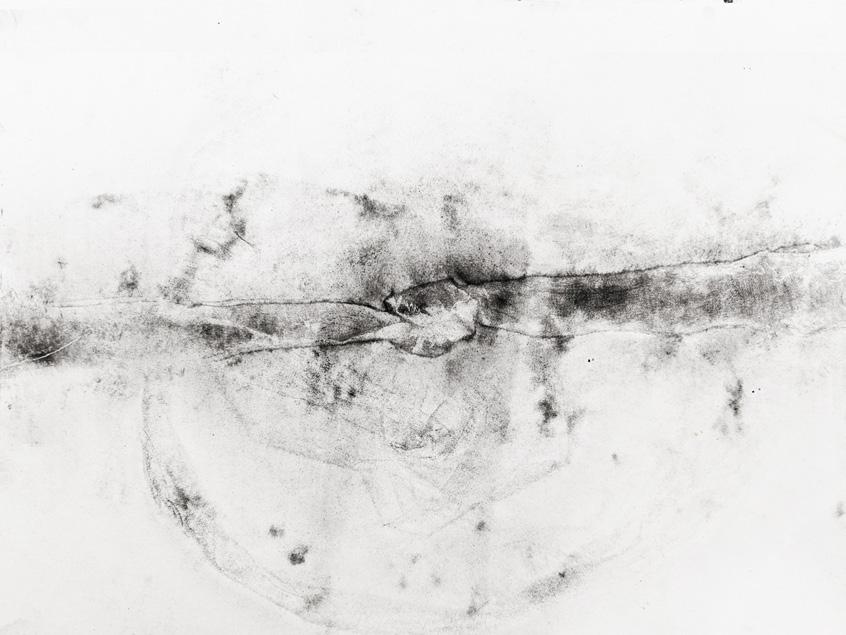

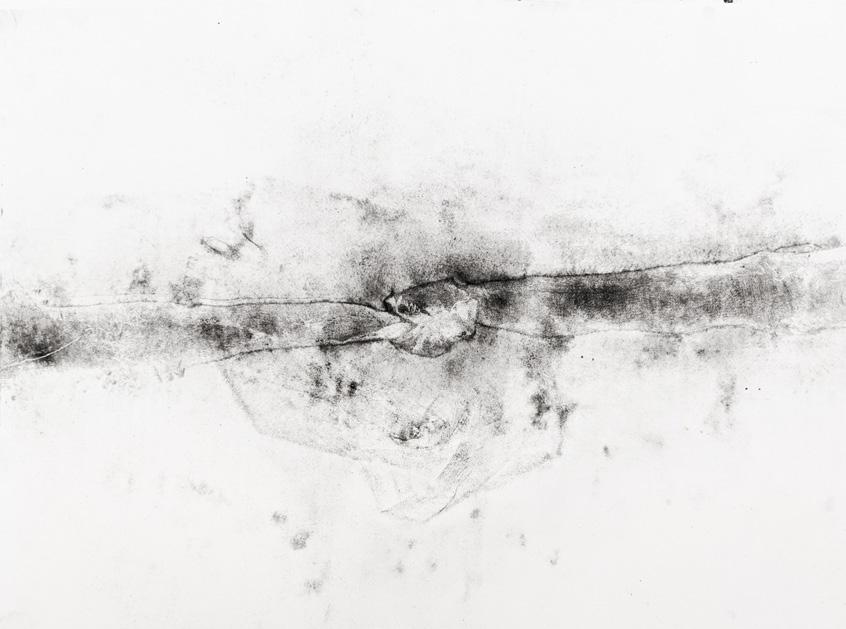

The ritual of drawing took place by reading historical fiction “Human Acts” by Hang Kang, depicting brutality of violence experienced by different charcters during 5.18 Gwangju Massacre.

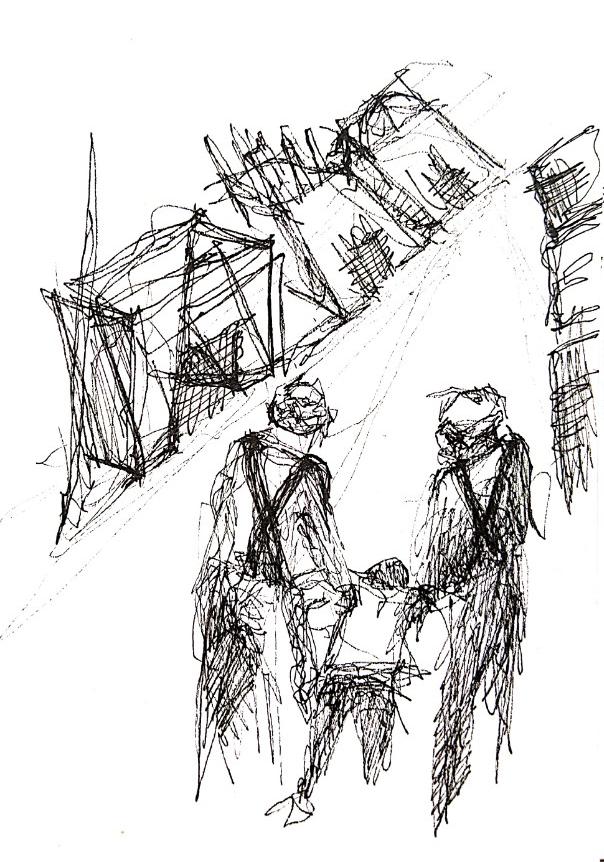

The form of massacre takes place on the street. Sound of shotting, stack of body, empty street, and public funeral. Through reading historical fiction that depicts the massacre in 1980 Korea, I conducted a ritual of drawing, imagining the pain of each characters.

19

Jisu Yang

3.0 Thesis Rambling

Han, Kang, and Deborah Smith. Human Acts: a Novel. Granta Books, 2020.

20

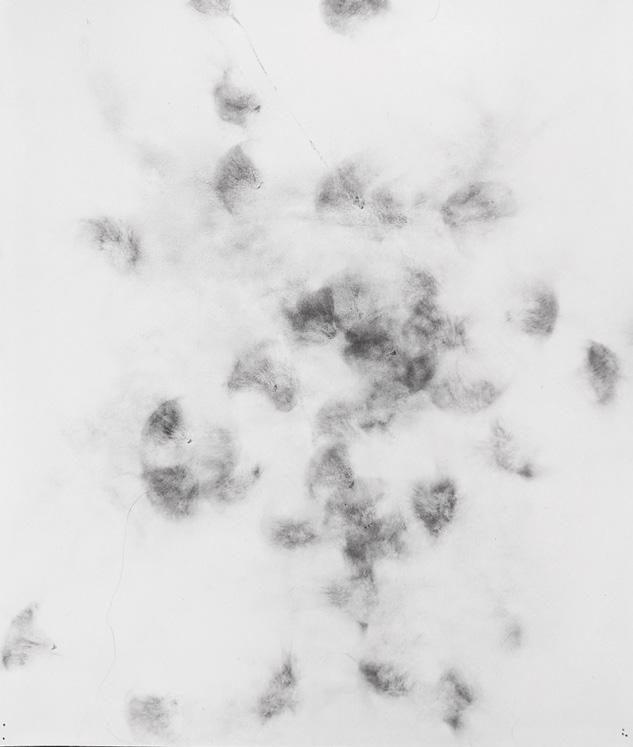

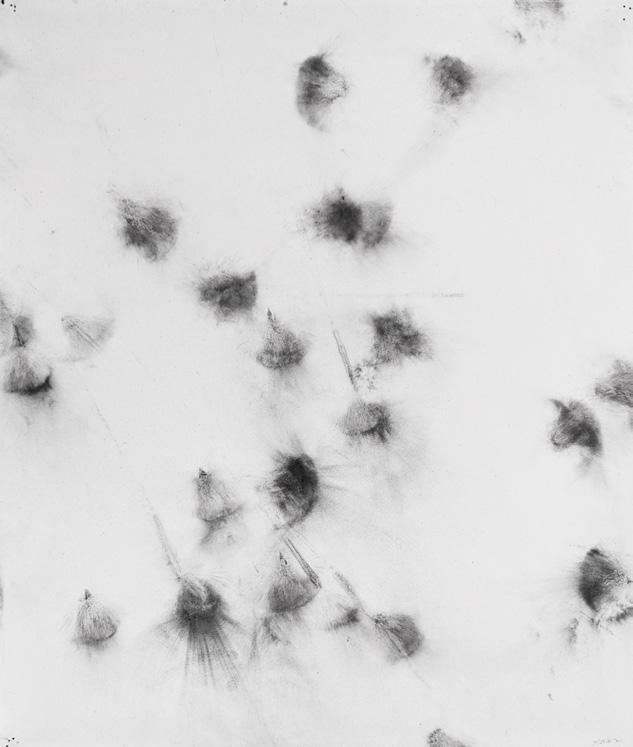

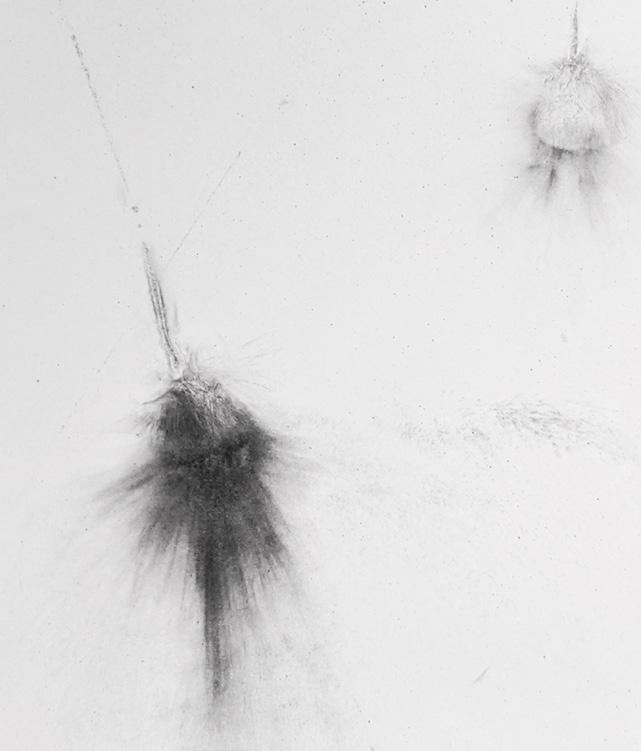

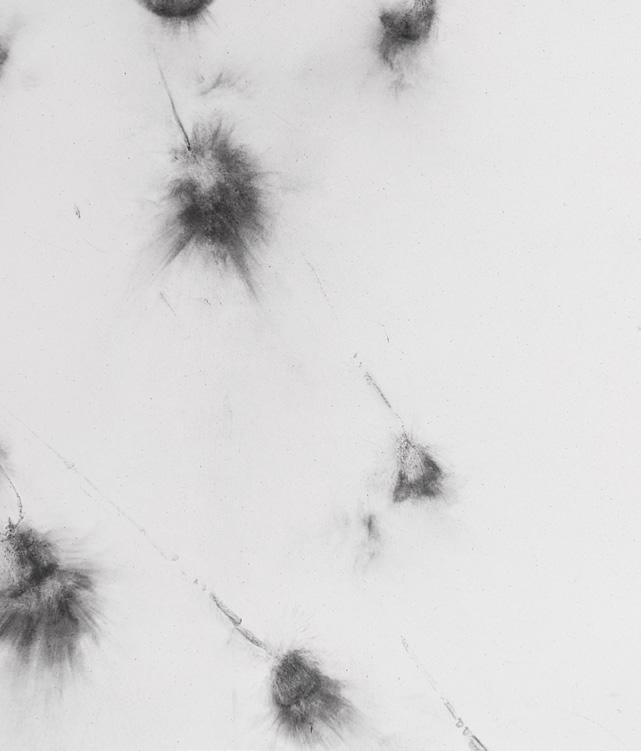

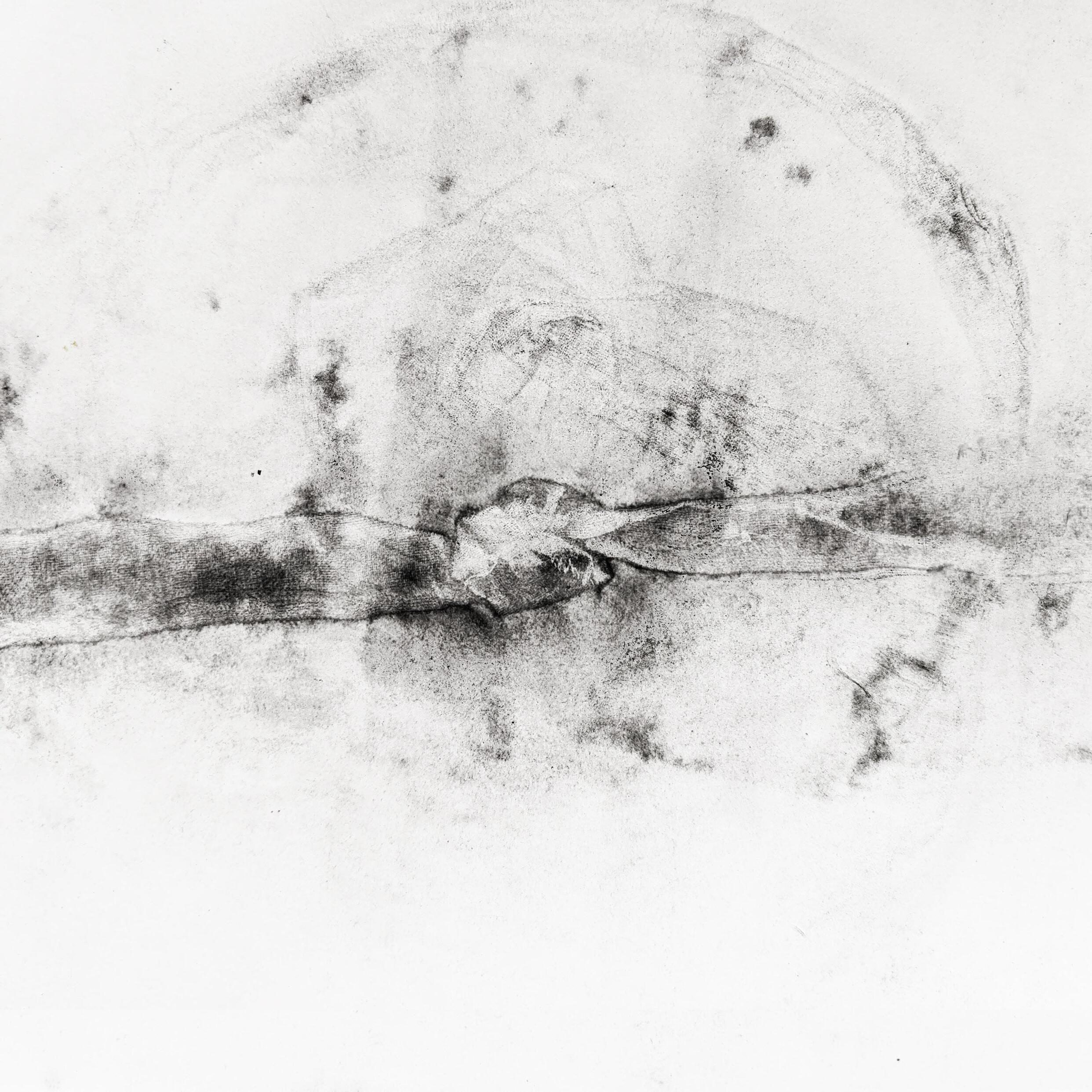

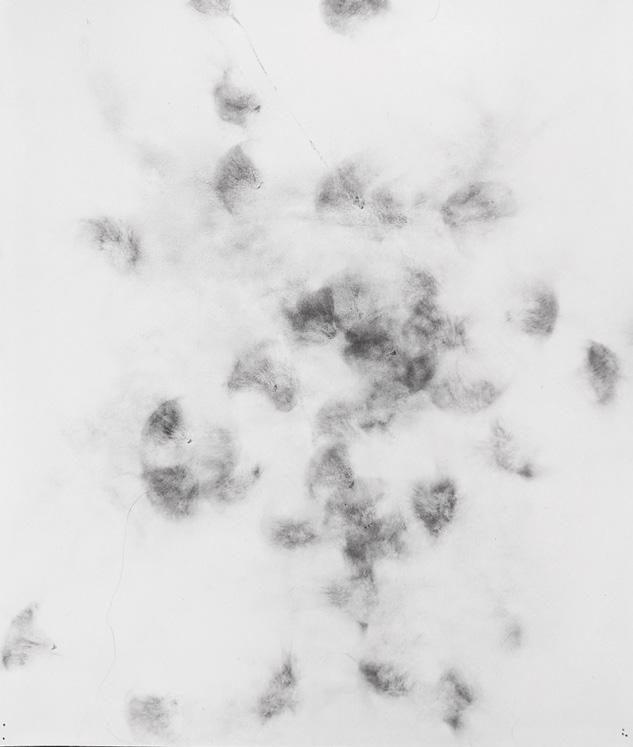

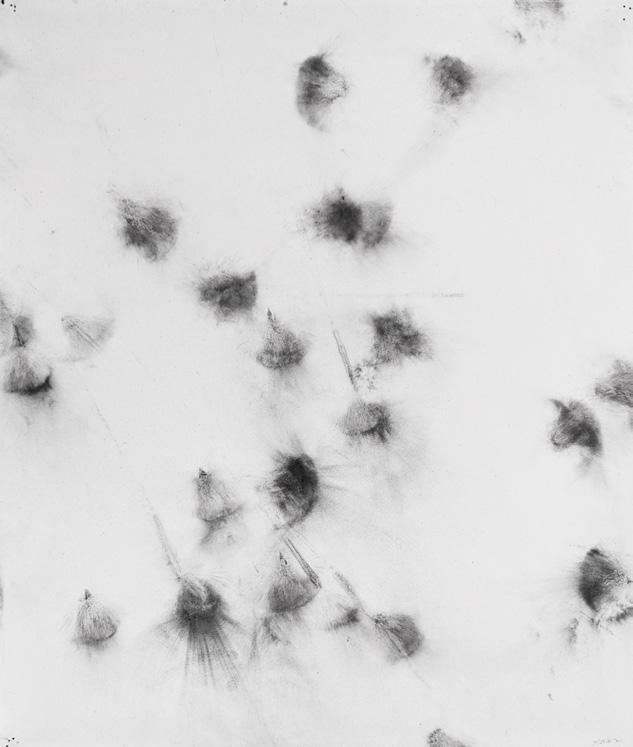

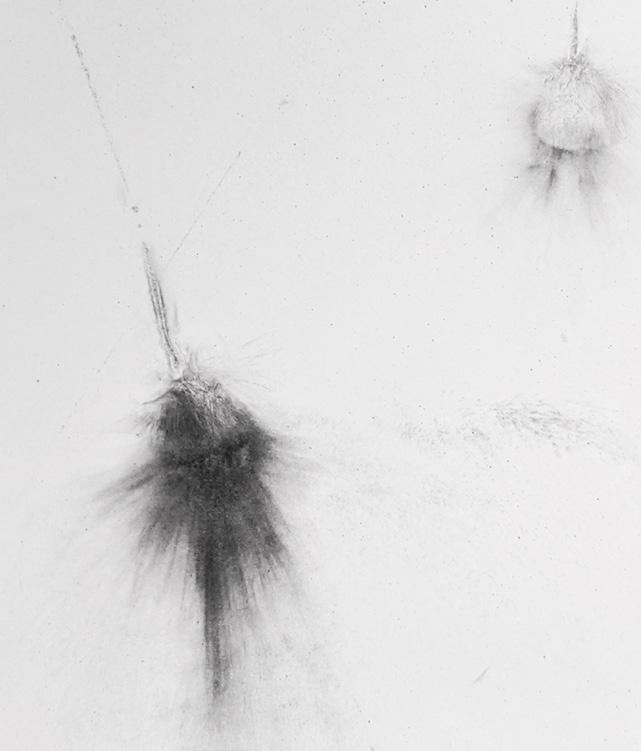

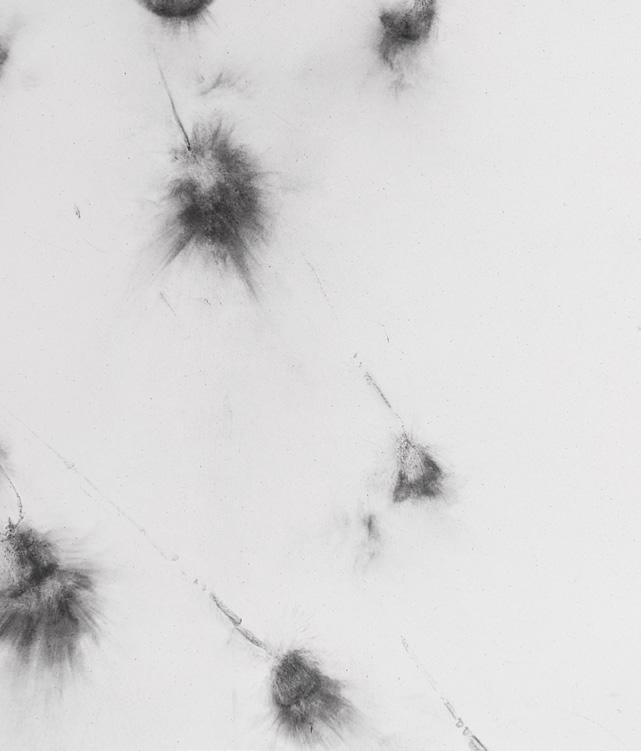

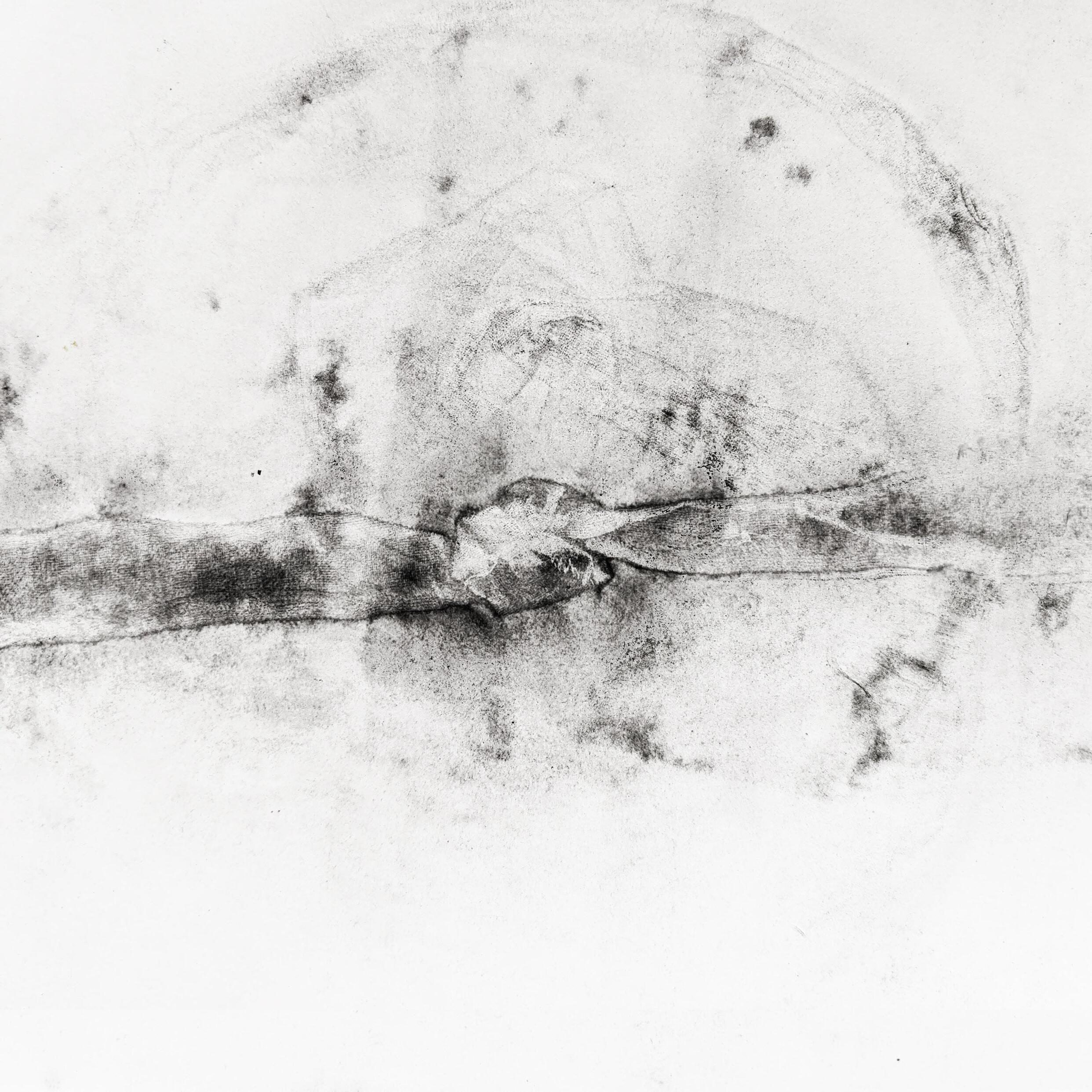

3.2 Drawing Representing Pain

In Korean tradition, the knot represents pain and the act of releasing the knot is the main laguage of the dance in relieving the pain of other.

21 Printing Knot on Paper, 11”

x 8.5”, charcoal powder on paper

Jisu Yang

Rambling

3.0 Thesis

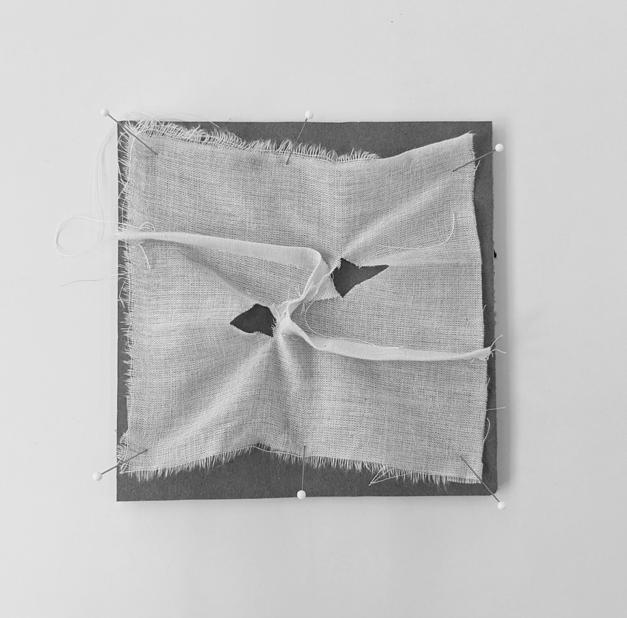

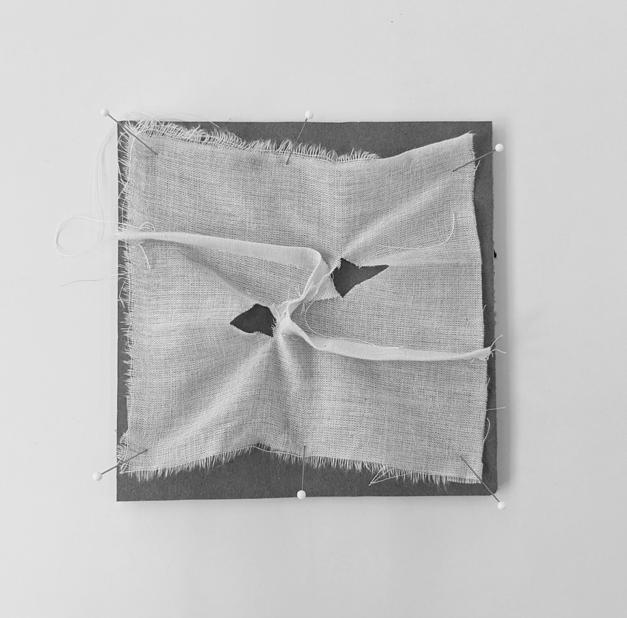

3.3 Making Physicalizing Pain

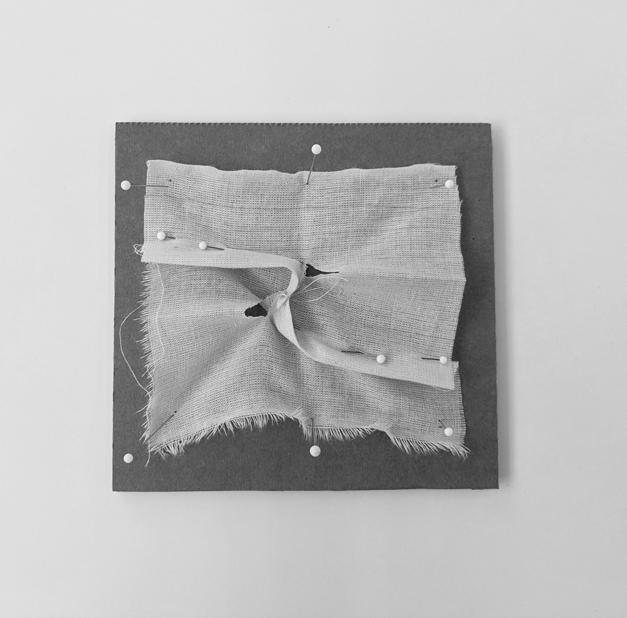

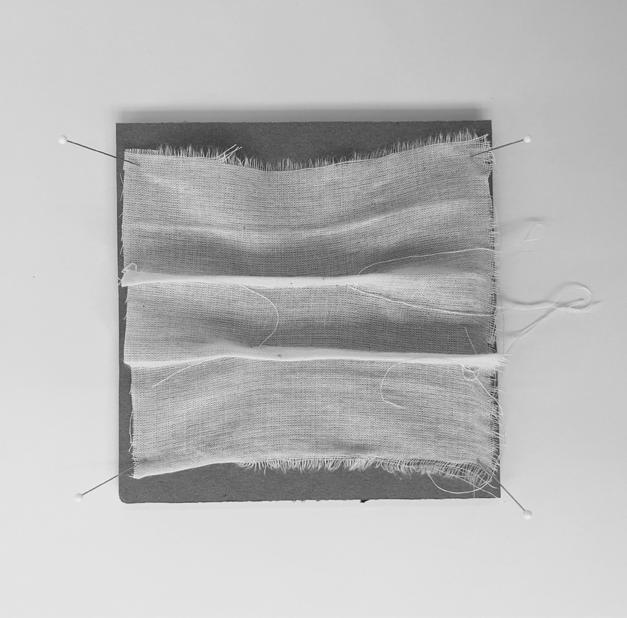

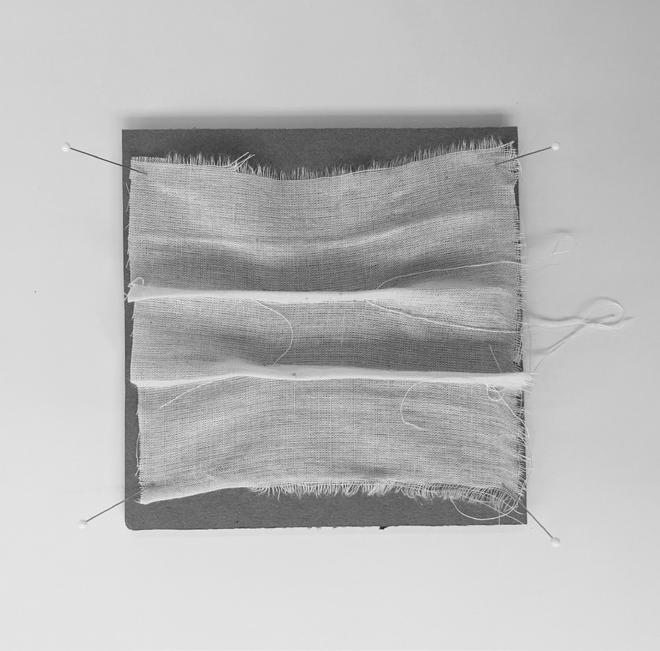

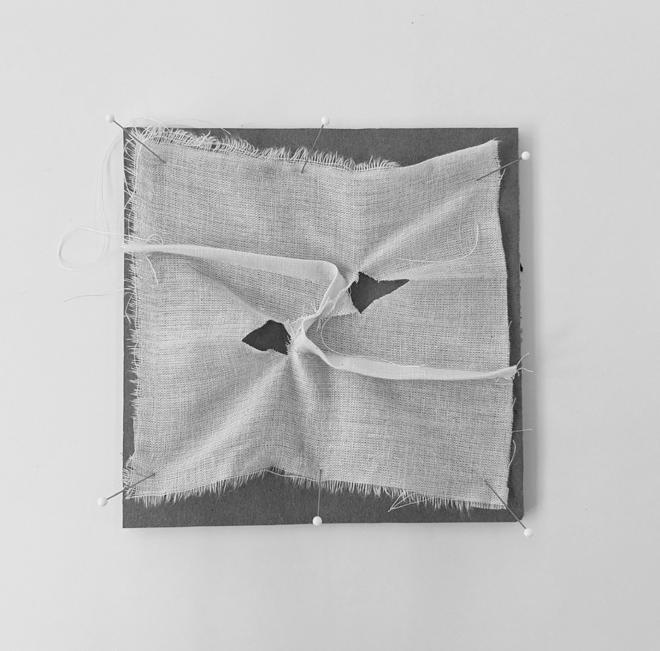

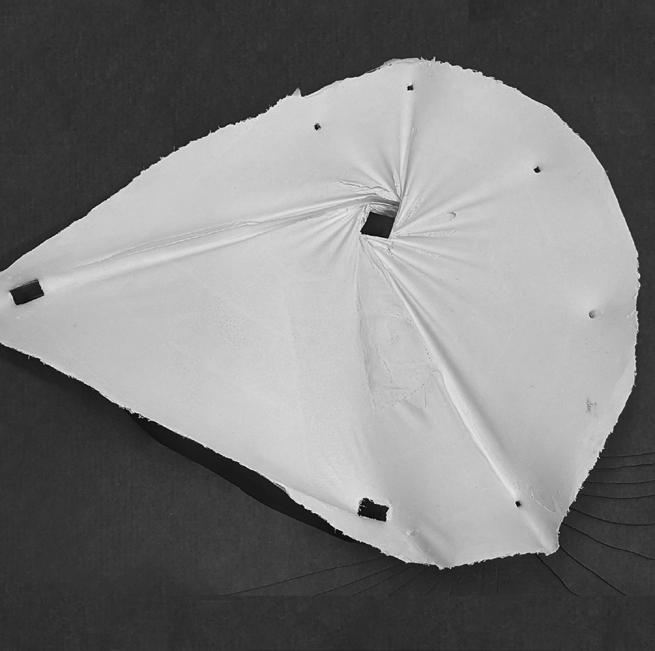

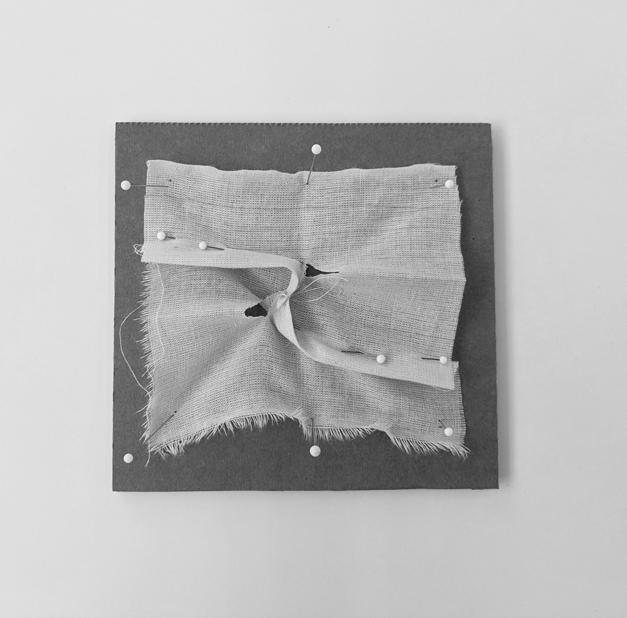

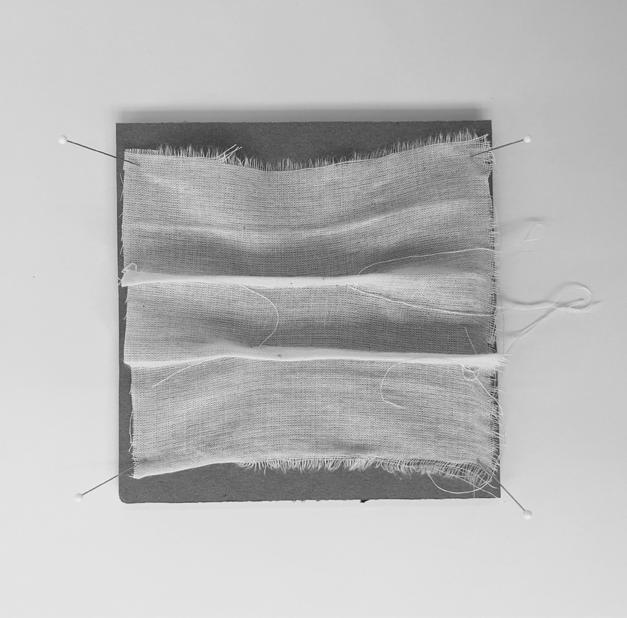

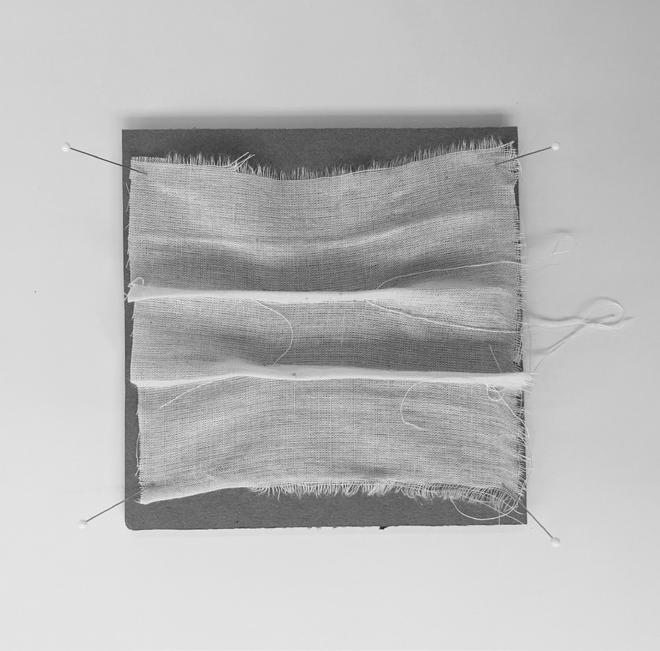

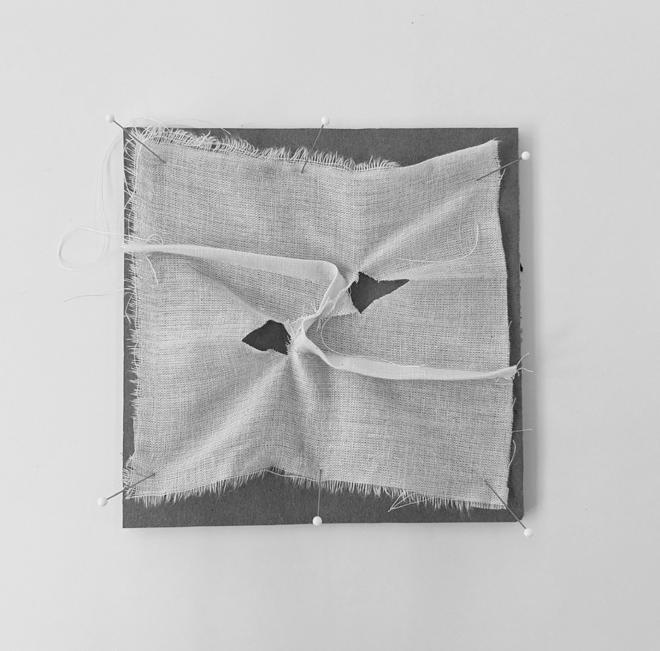

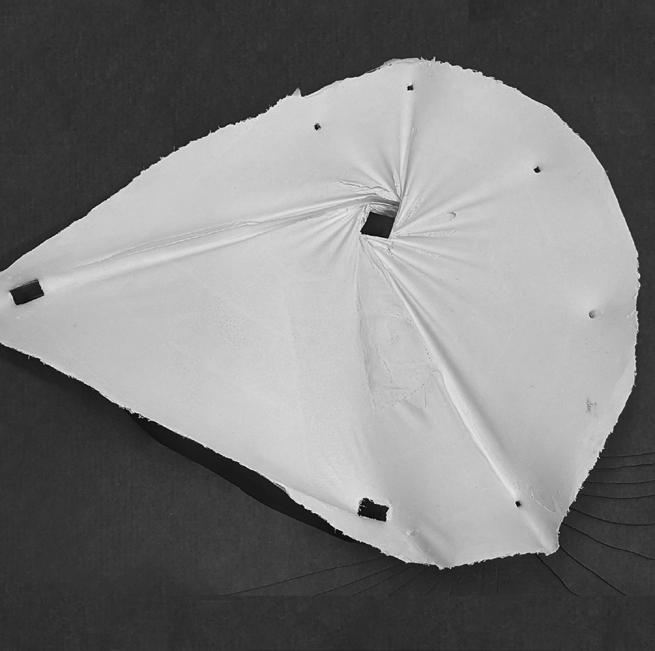

Iteration 1: Fabric

The dancer gathers fabric, twists the fabric, reverses the action, releases the fabric. This process of operation was inspired to use fabric that twists and creates folds around the center, as a way of imagining the type of landscape in the project.

22

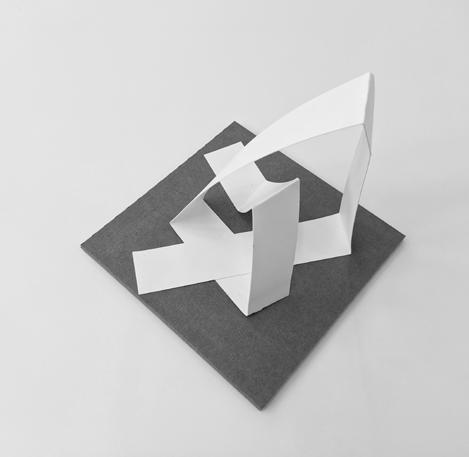

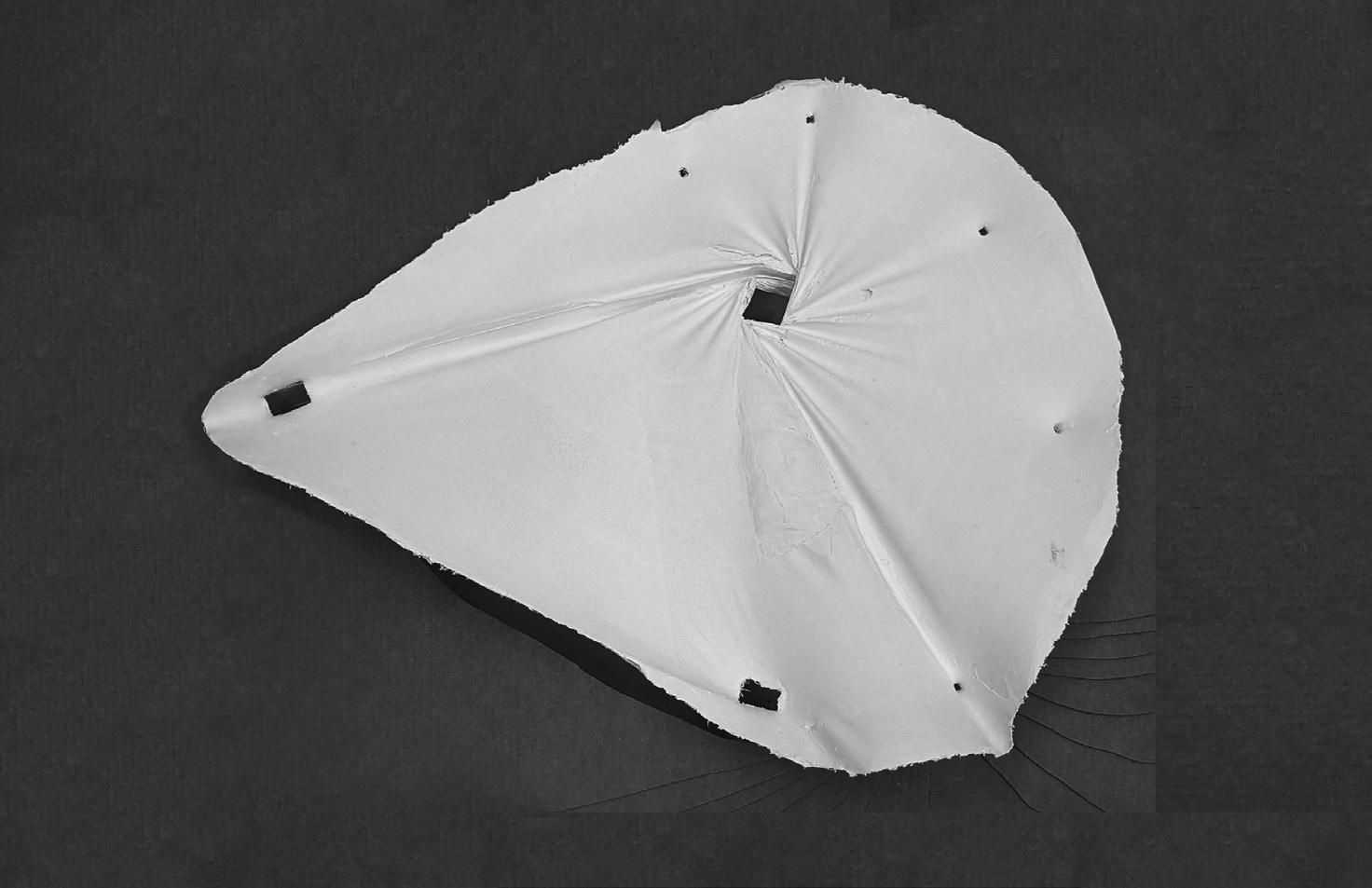

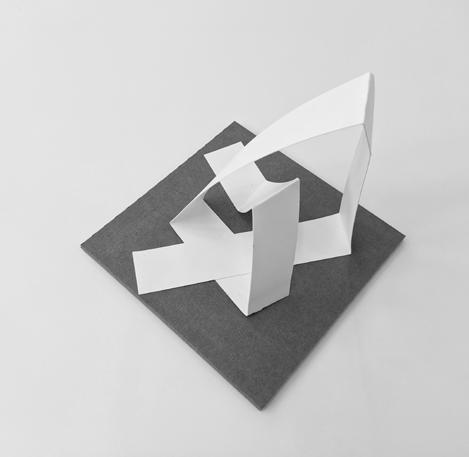

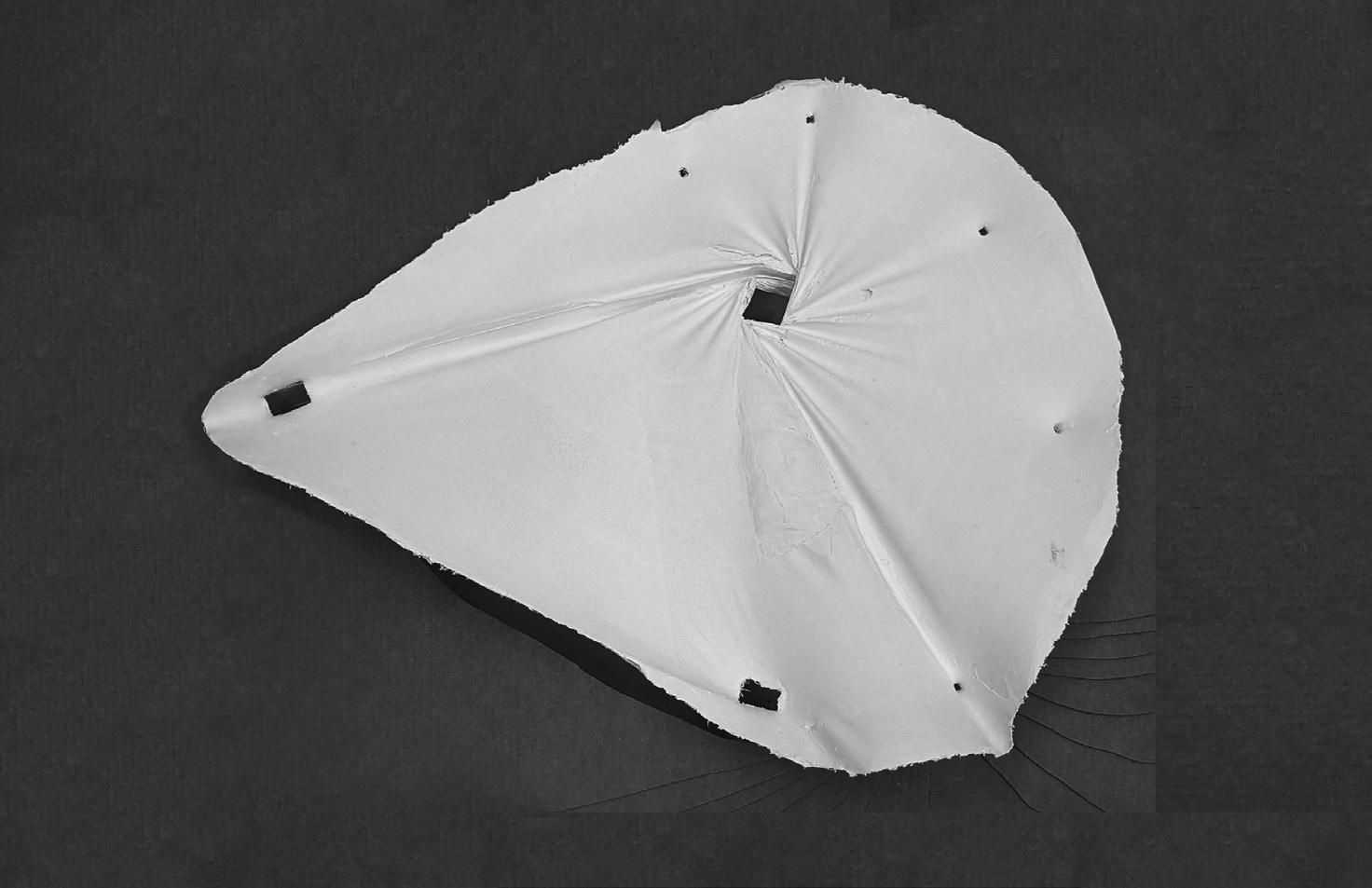

Iteration 2: Paper

The first step is to interlock paper as a knot. Another step includes making cuts on the membrane and pulling towards the center to create space for a knot.

23

Jisu Yang

3.0 Thesis Rambling

3.3 Making Physicalizing Pain

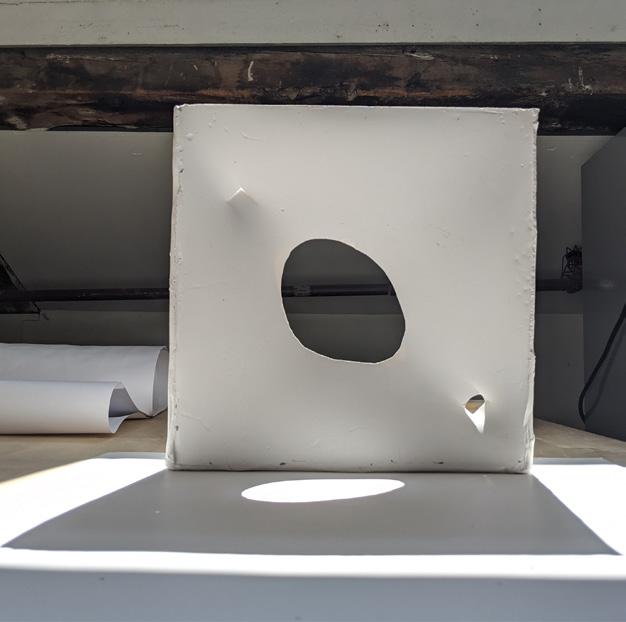

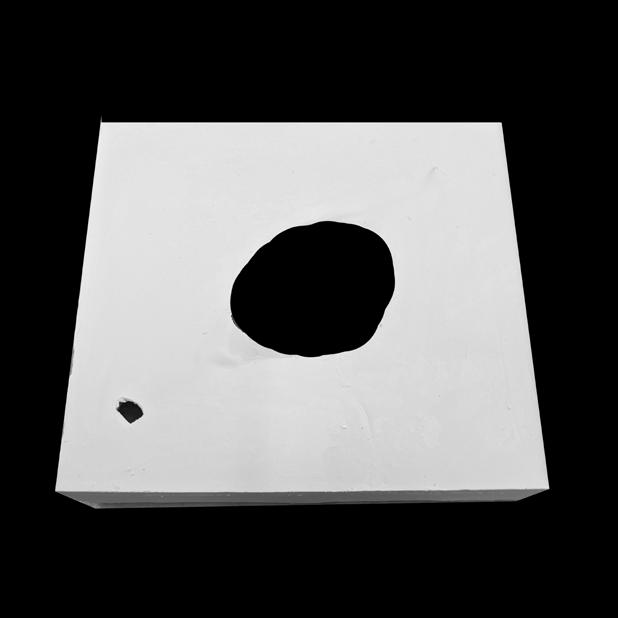

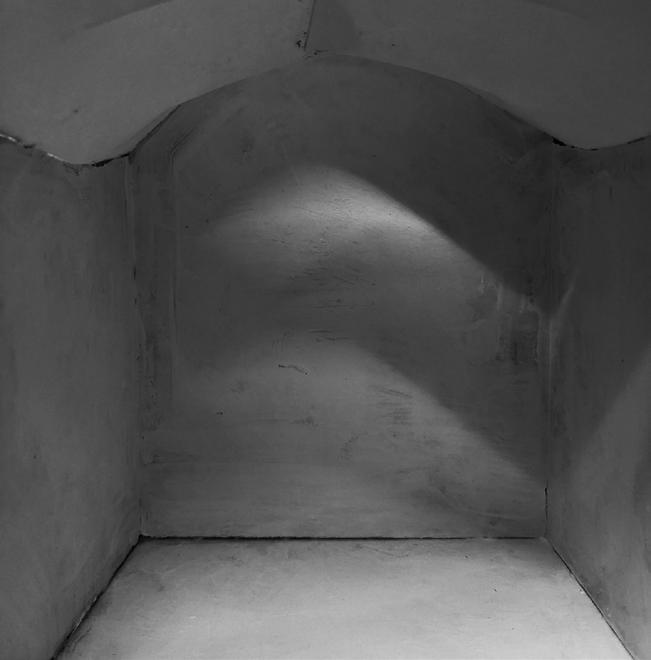

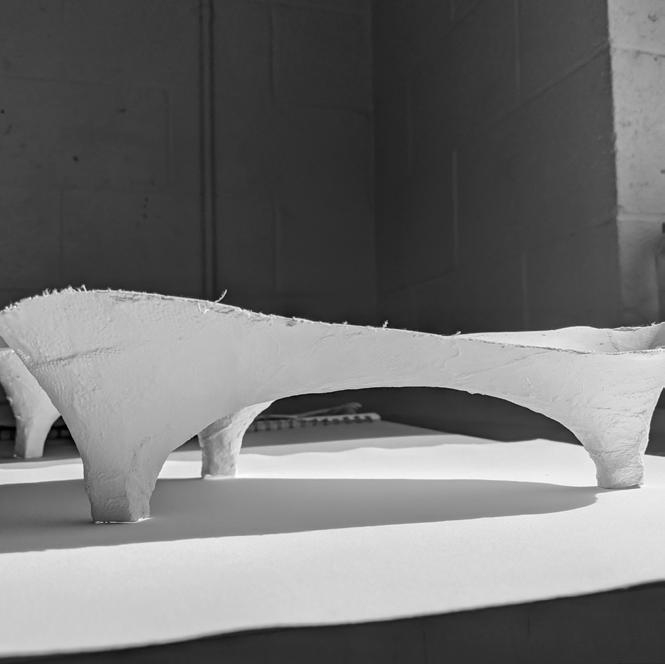

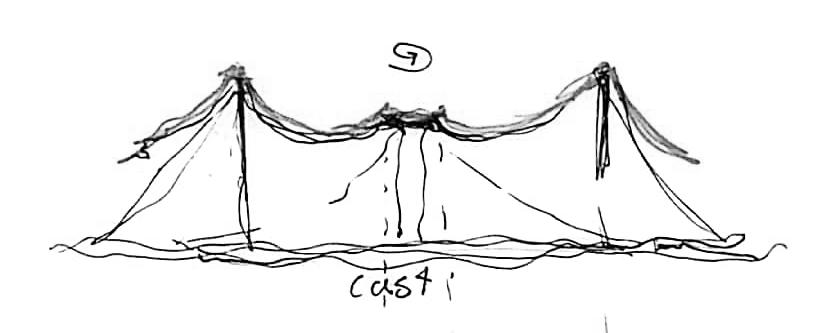

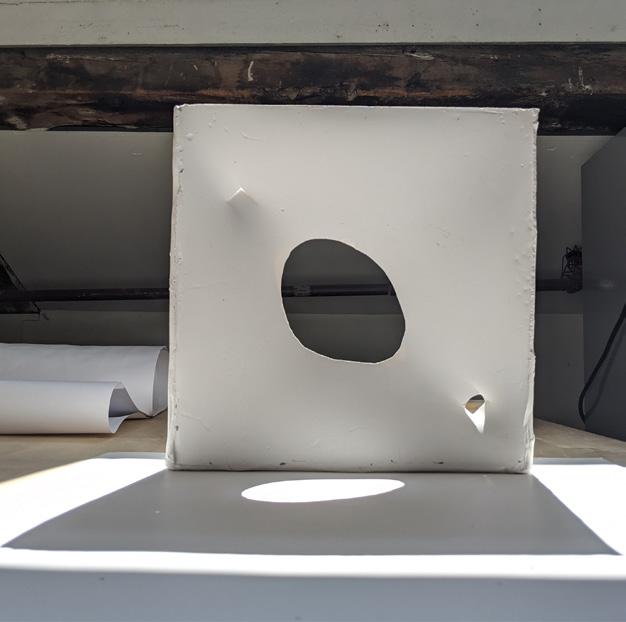

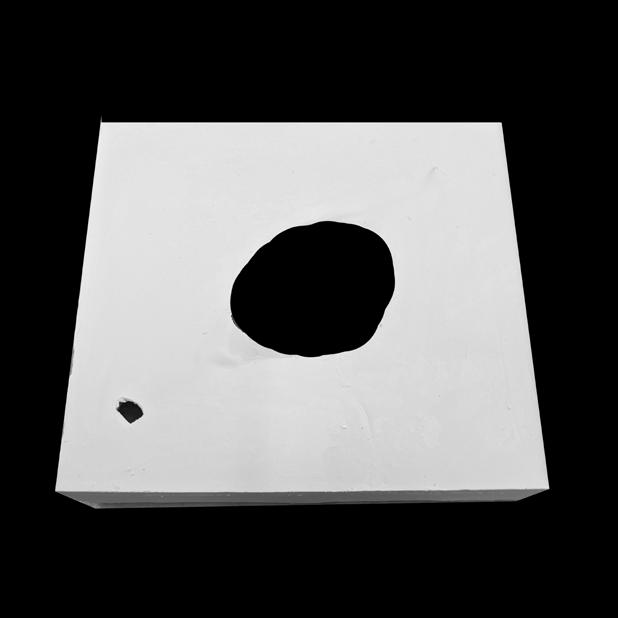

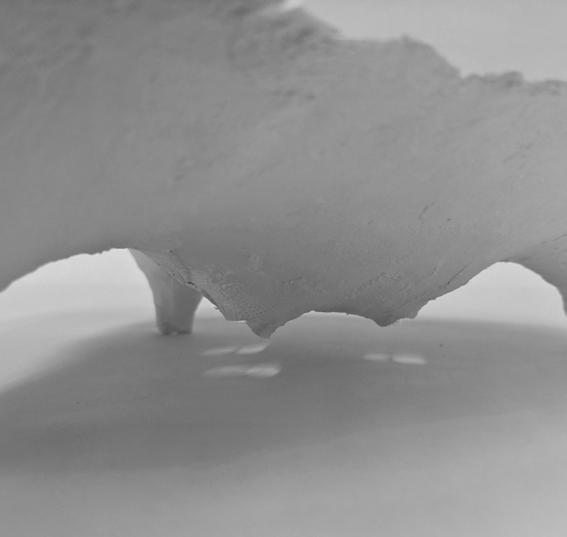

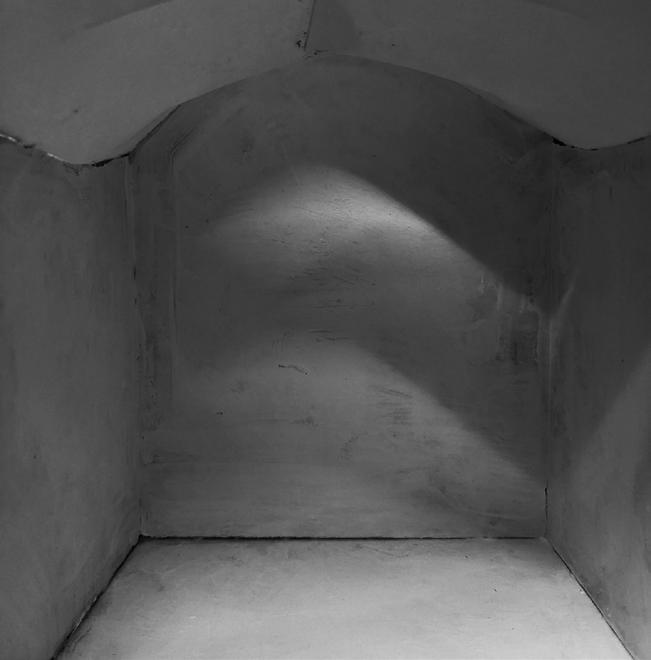

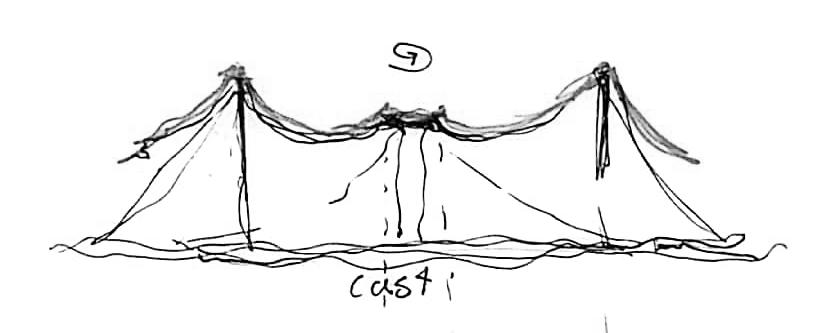

Iteration 3: Casting

The next step is to use latex, or a rubber fabric, that gets stretched by wood dowels. Catalogues of membranes are created as the length of wood dowels vary. This led to the understanding of how casting the negative space of stretched latex could create different types of openings and formal qualities of space as the wall thickens and thins.

24

Iteration 3.2: Casting

This iteration took place by making smaller scale of puncture in array to develop a sense of corridor of space.

25

Jisu Yang

3.0 Thesis Rambling

3.3 Making Physicalizing Pain

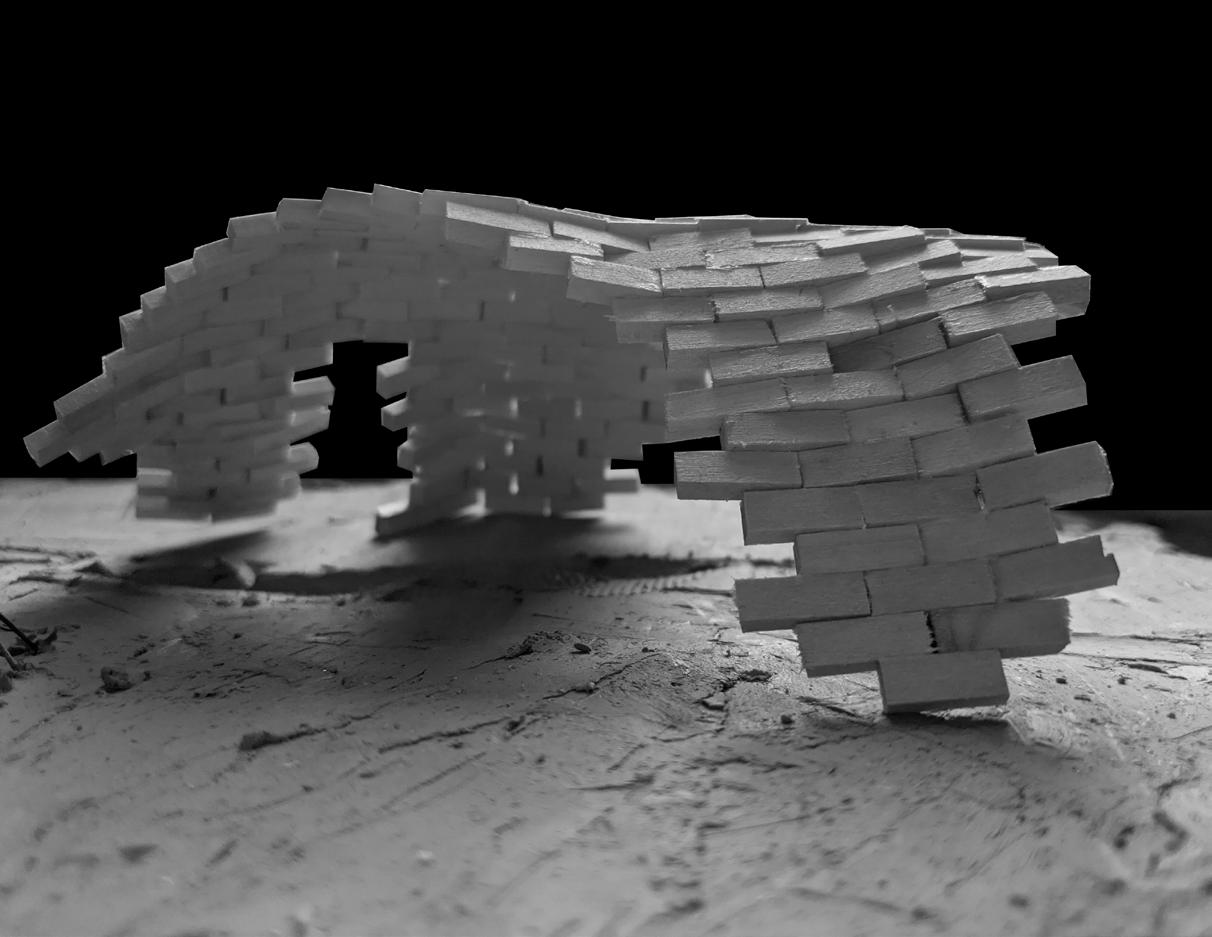

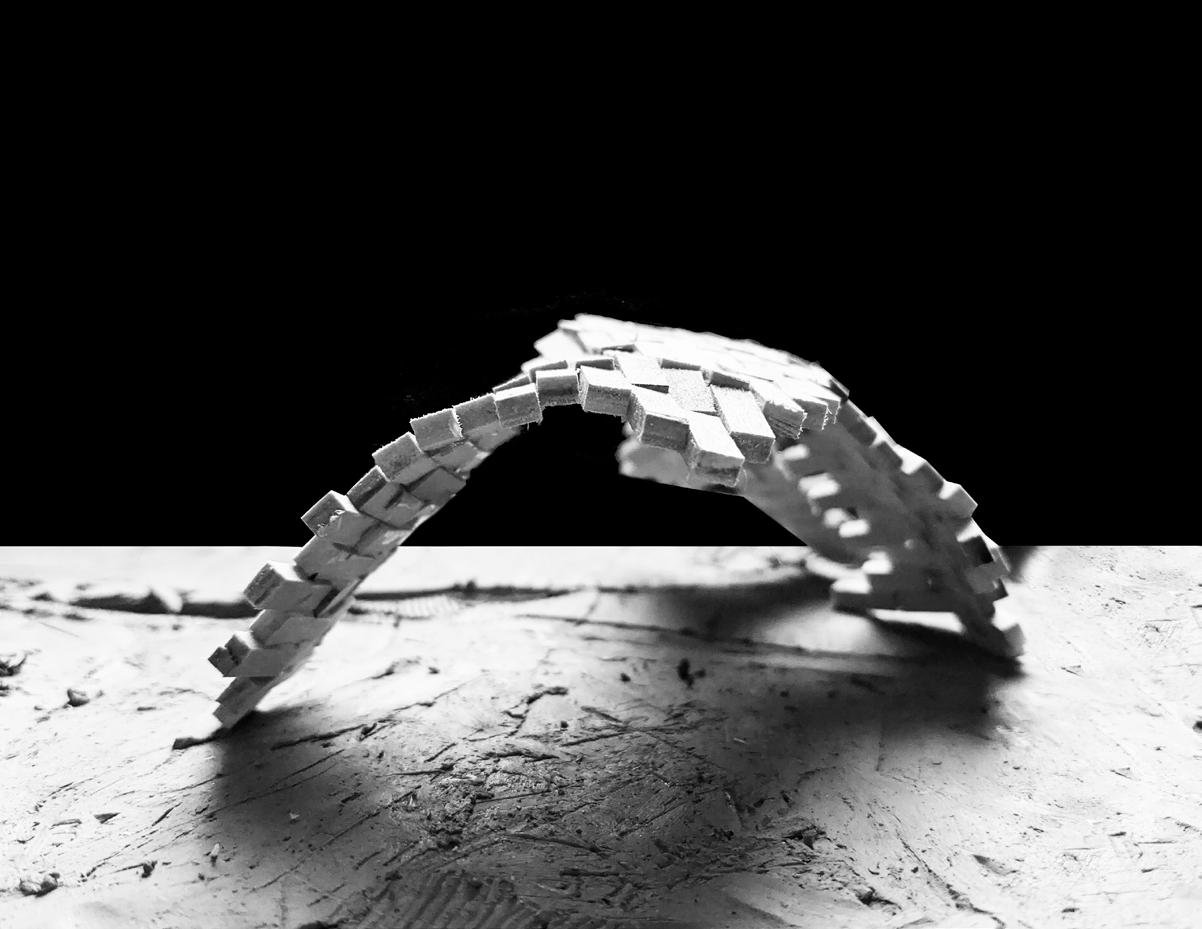

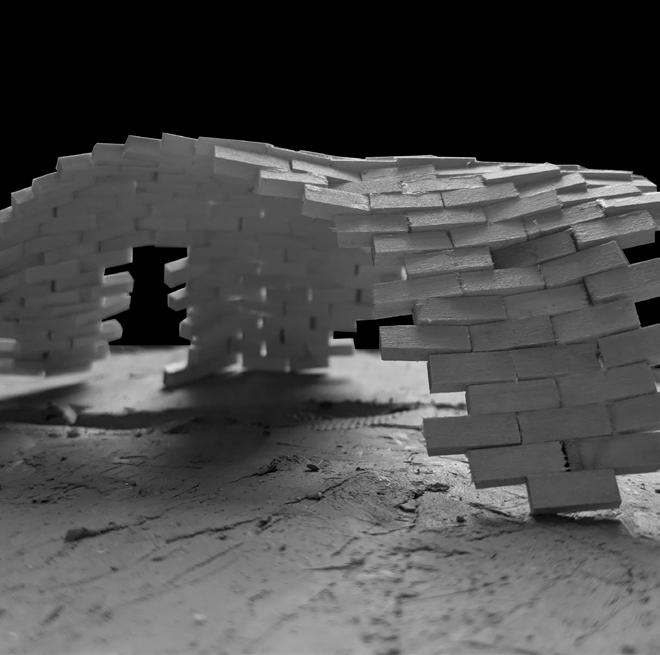

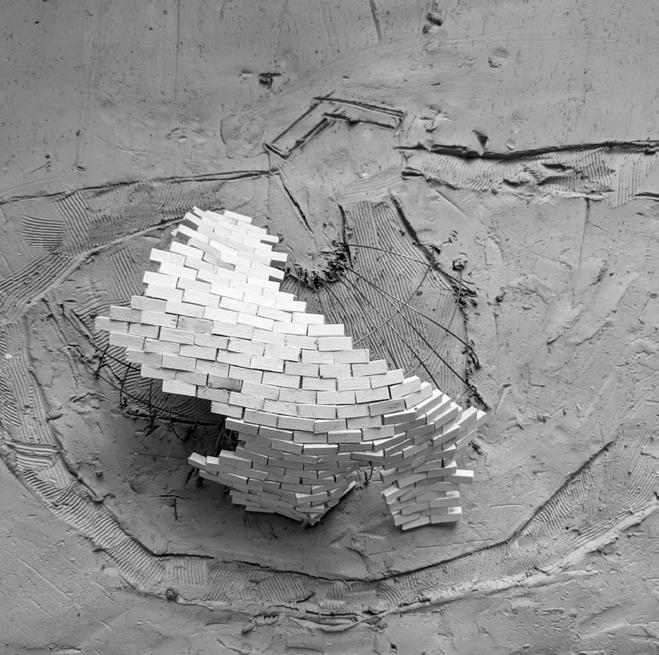

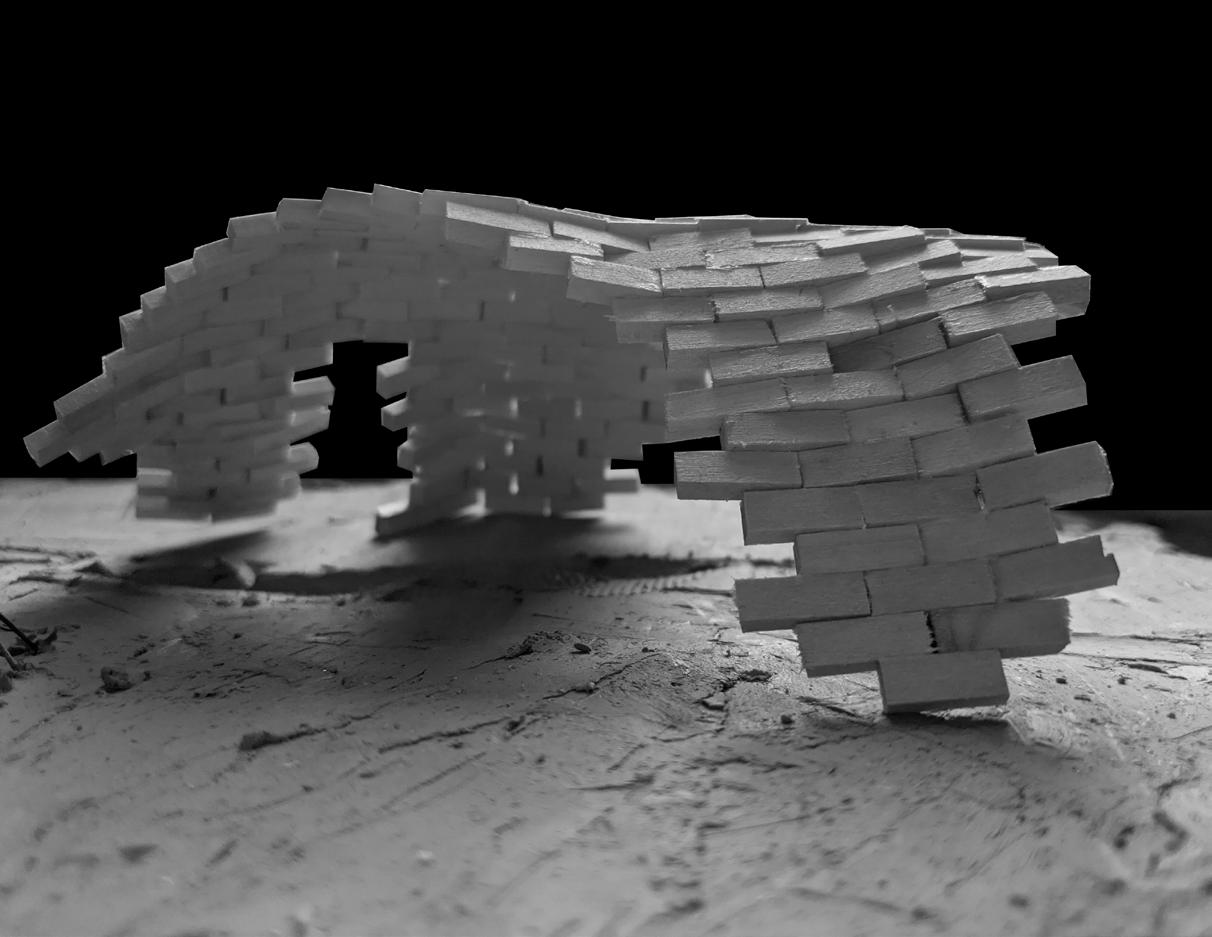

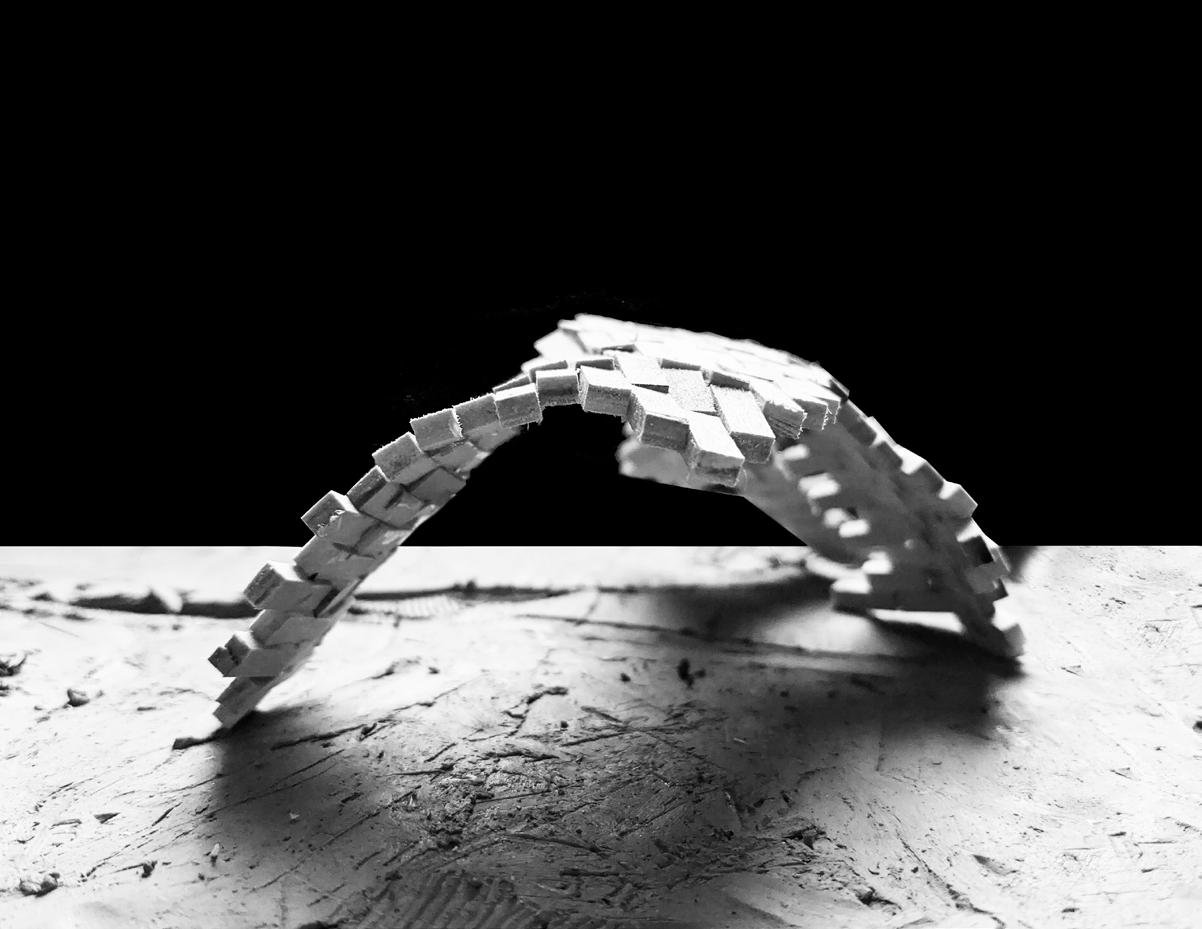

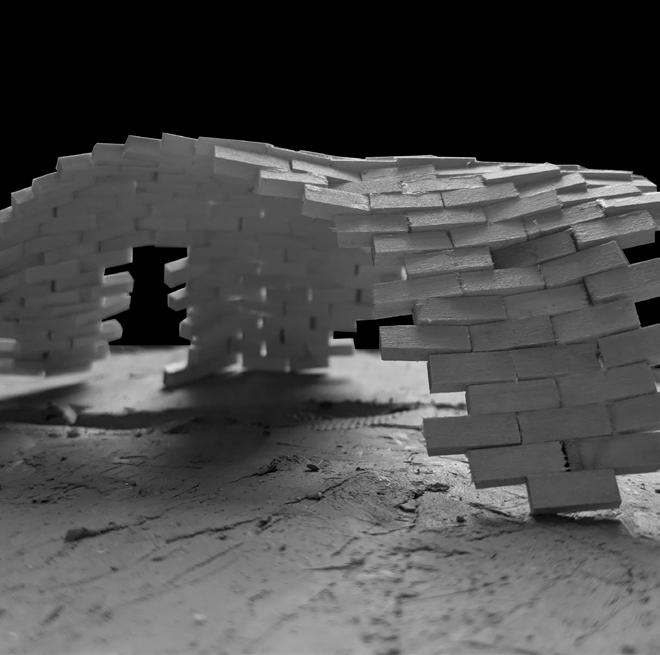

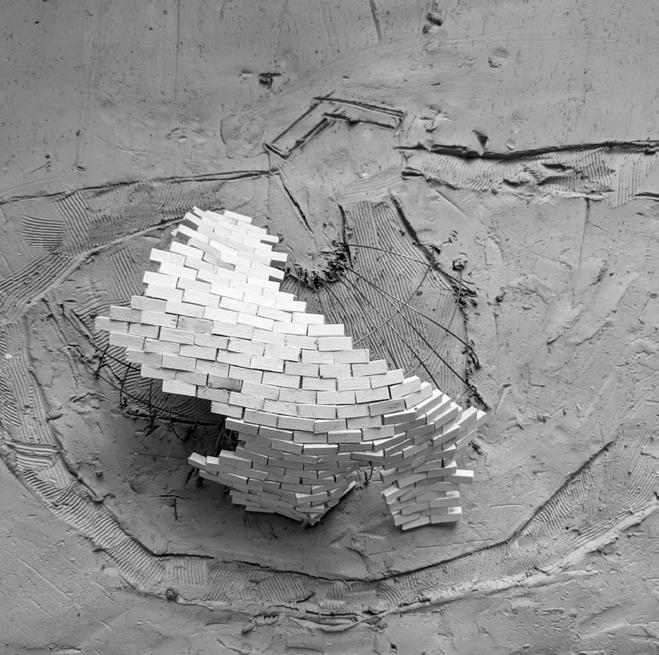

Iteration 4: Bricks

The print of the knot is projected on clay. The piano wire constructs a form work in a shell. Brick gathers, climbing up the form-work. After taking out, the brick stands on its own. There is a moment where the brick fails, and this speaks about the failure of culture or the failure of individuals.

26

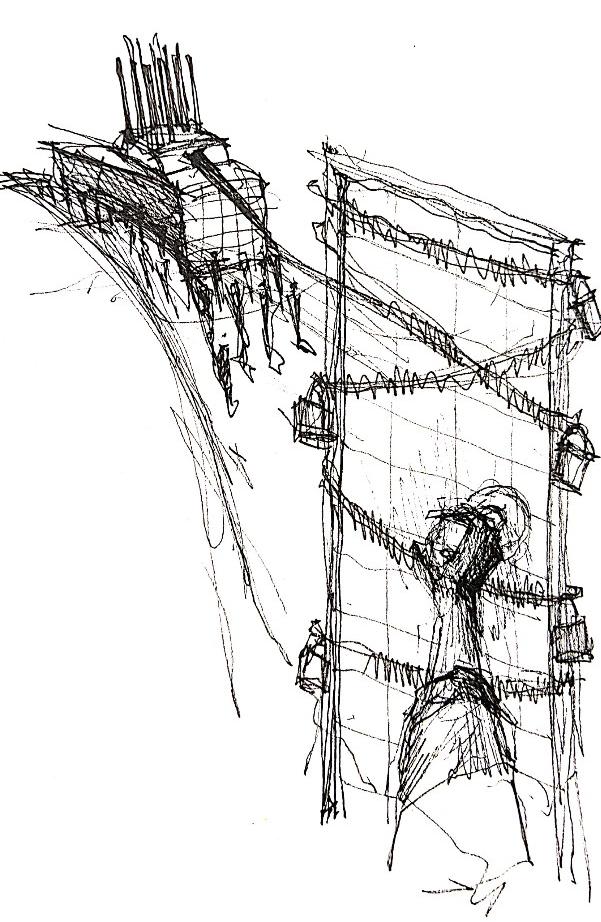

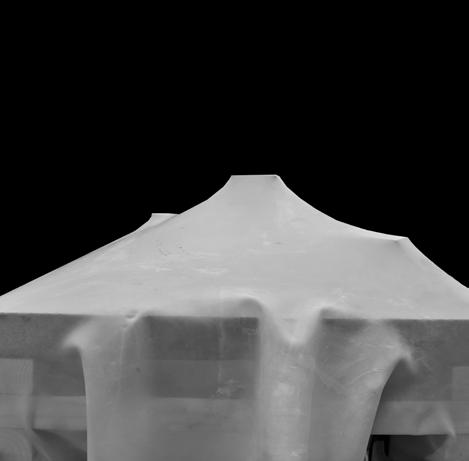

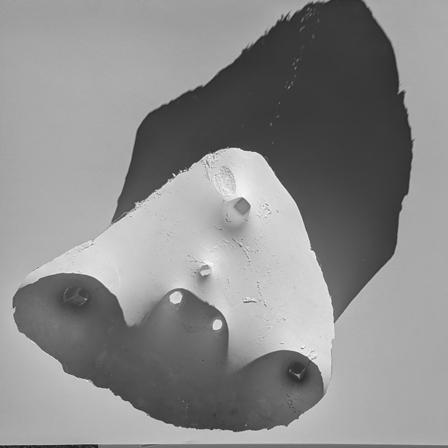

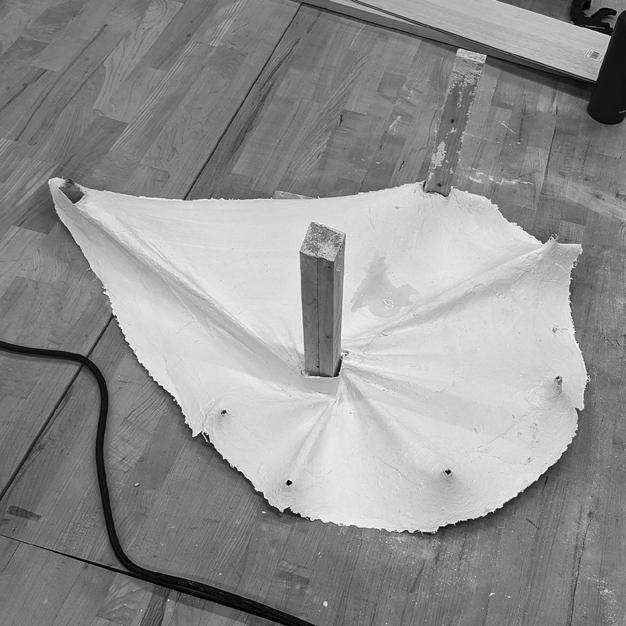

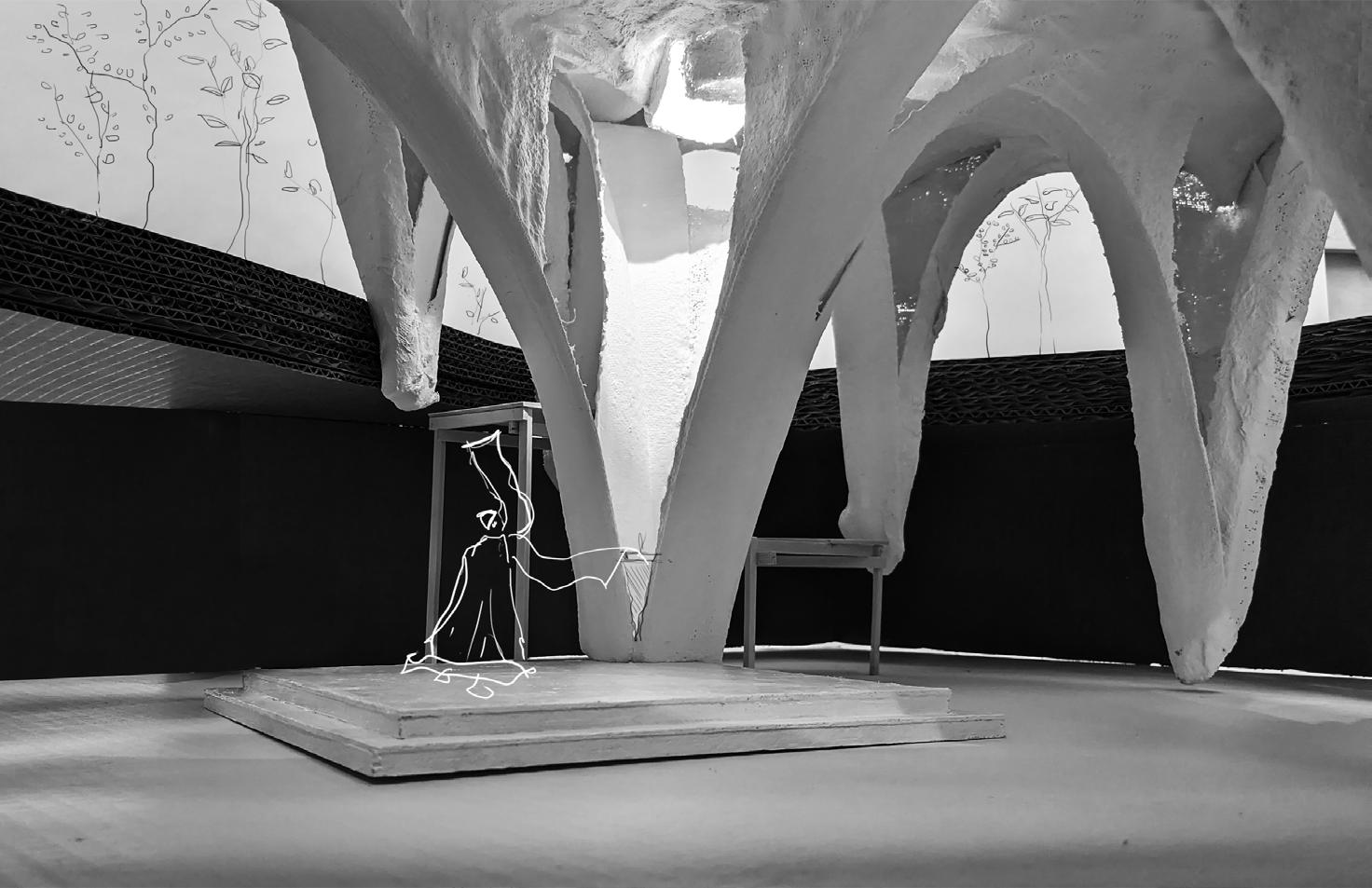

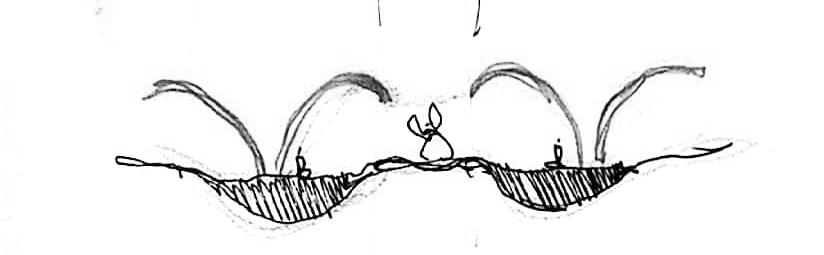

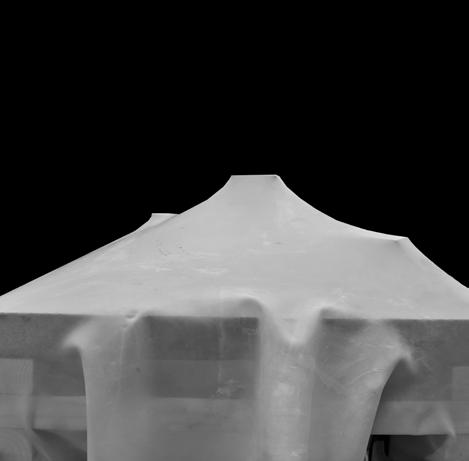

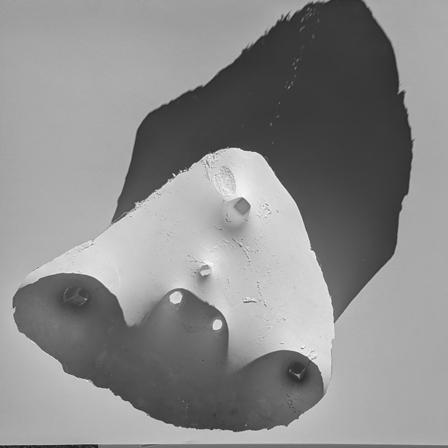

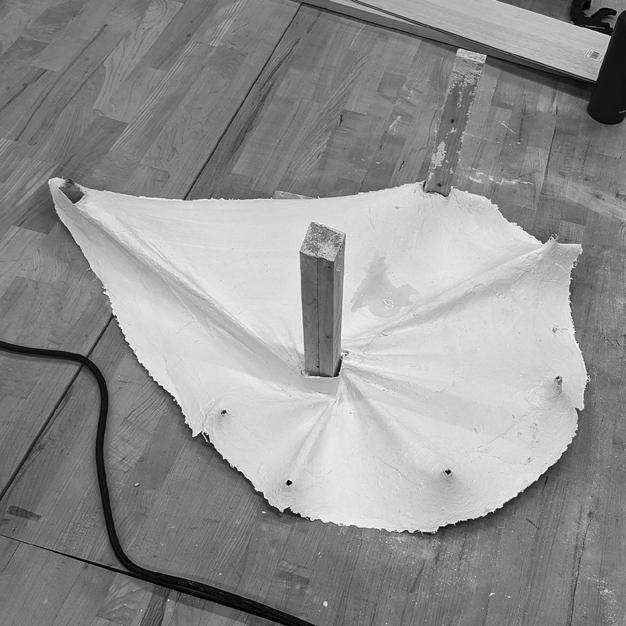

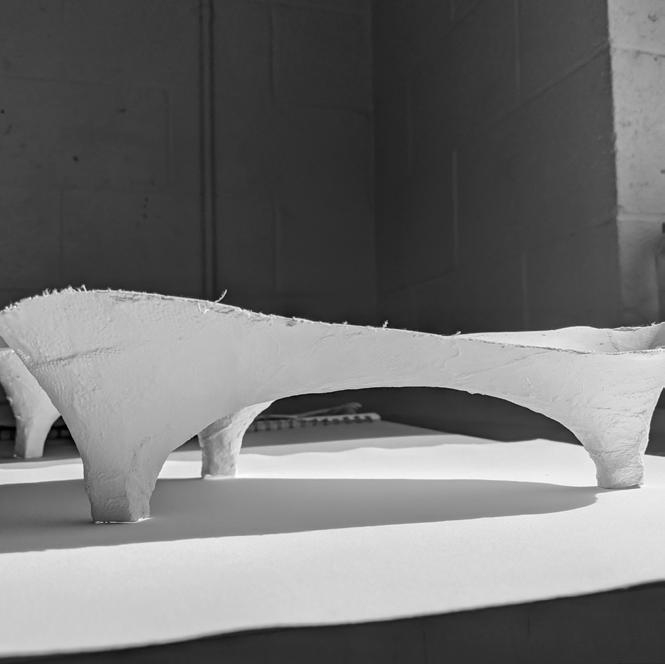

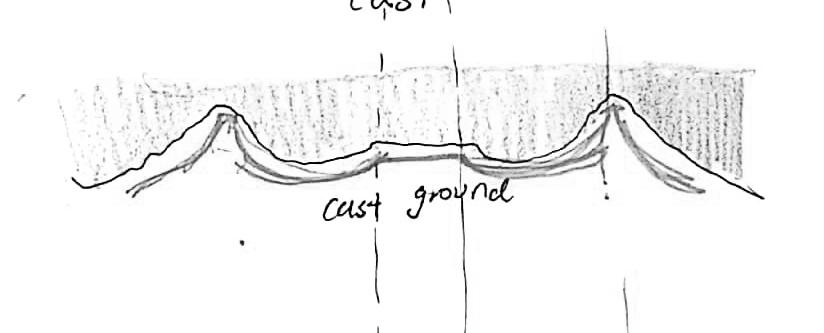

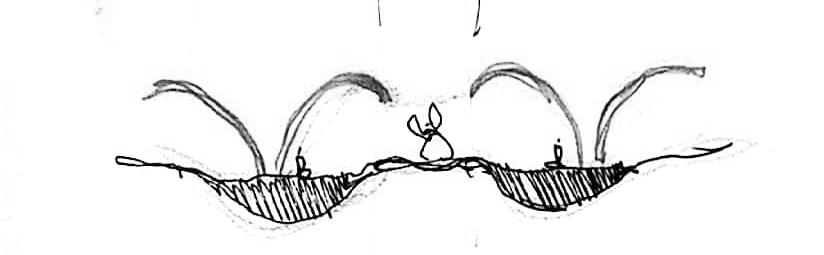

Iteration 5: Catenoidal shell

This iteration takes place as the thesis begins to commit more on how architecture gets constructed in the form of a shell structure. The stretching of the fabric gets inverted, forming catenoidal vaults that are self-supported.

27

Jisu Yang

Rambling

3.0 Thesis

3.3 Making Physicalizing Pain

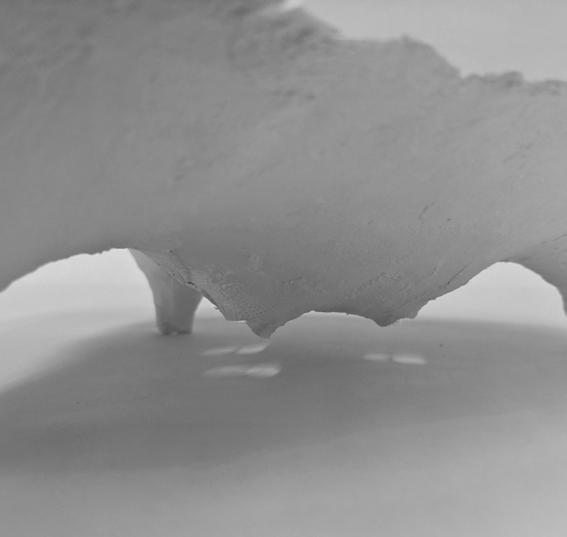

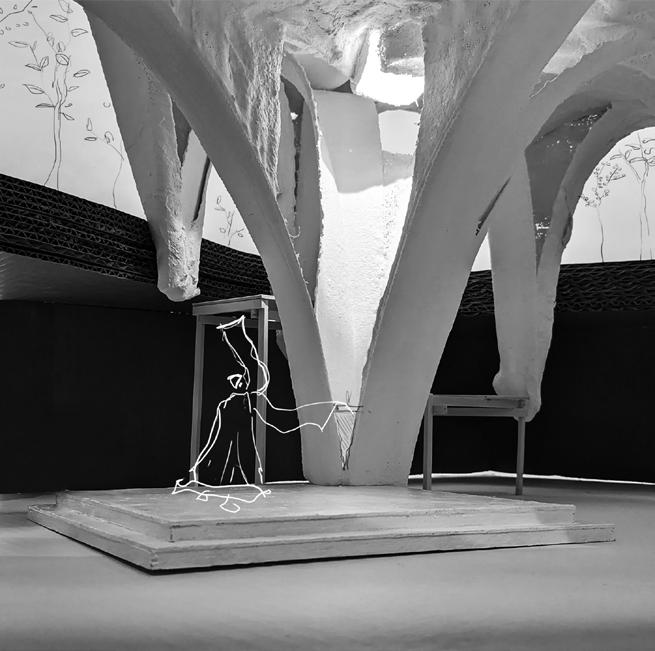

Iteration 6: Knot and shell

The knot emerges by twisting the center column that gathers folds of the fabric. This knot is held by catenary vaults that inhabit the periphery.

28

29

Yang 3.0 Thesis Rambling

Jisu

3.3 Making Physicalizing Pain

30

Iteration 1: fabric

Iteration 2: paper

Iteration 3: plaster cast

31

Iteration 5: shell

Iteration 6: shell with knot

Iteration 4: bricks

Jisu Yang

Thesis Rambling

3.0

3.3 Making Physicalizing Pain

32

33 Jisu Yang 3.0 Thesis Rambling

34

4. FINAL THESIS RAMBLING

35 4.0 Final Thesis Rambling Jisu Yang

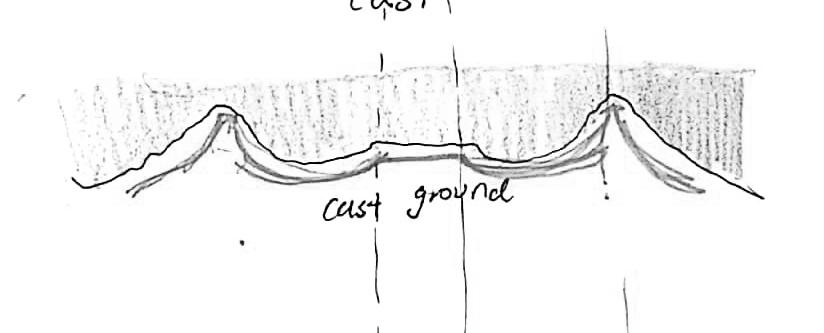

36 Invert Press Cast Accumulate

Stages of operation in creating the final iteration for the pavilion includes

1. casting fabric that gathers into the center creating landscape of folds

2. Pressing another fabric ontop of the original cast and recast the fabric

3. Overlay two layers of landscape

4. Accummulate plaster with particles of charcoal that inhabit crevices

37

Jisu Yang

4.0 Final Thesis Rambling

38

39

Yang 4.0 Final Thesis Rambling

Jisu

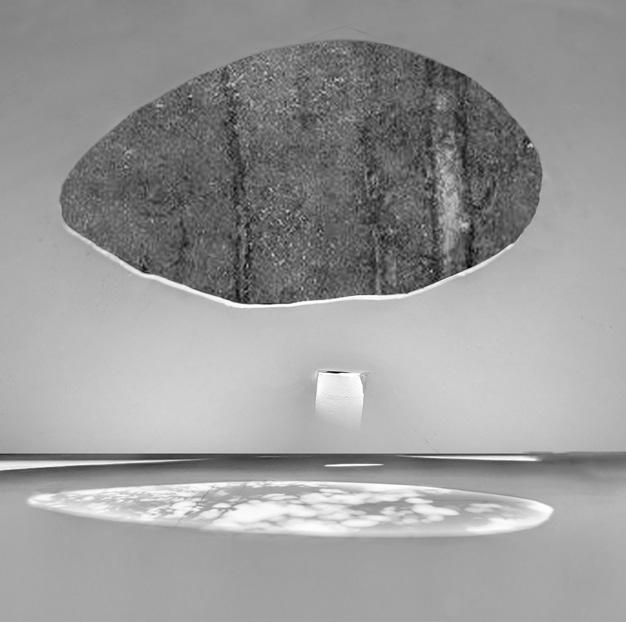

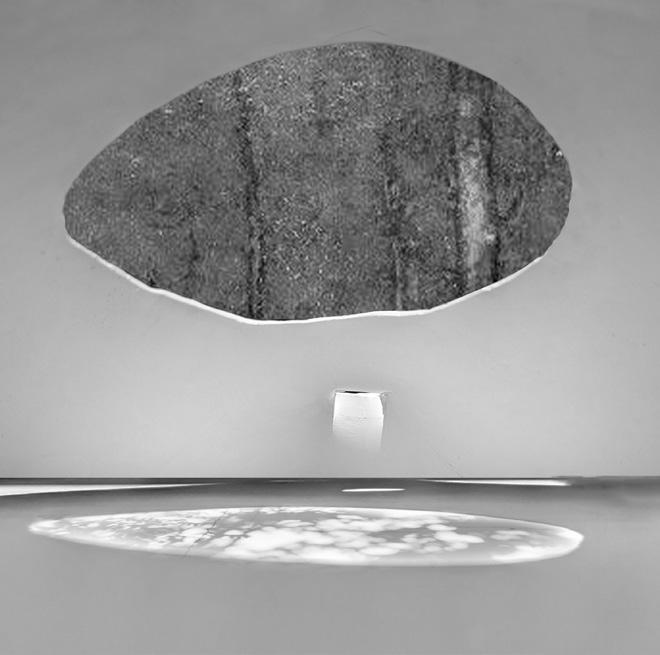

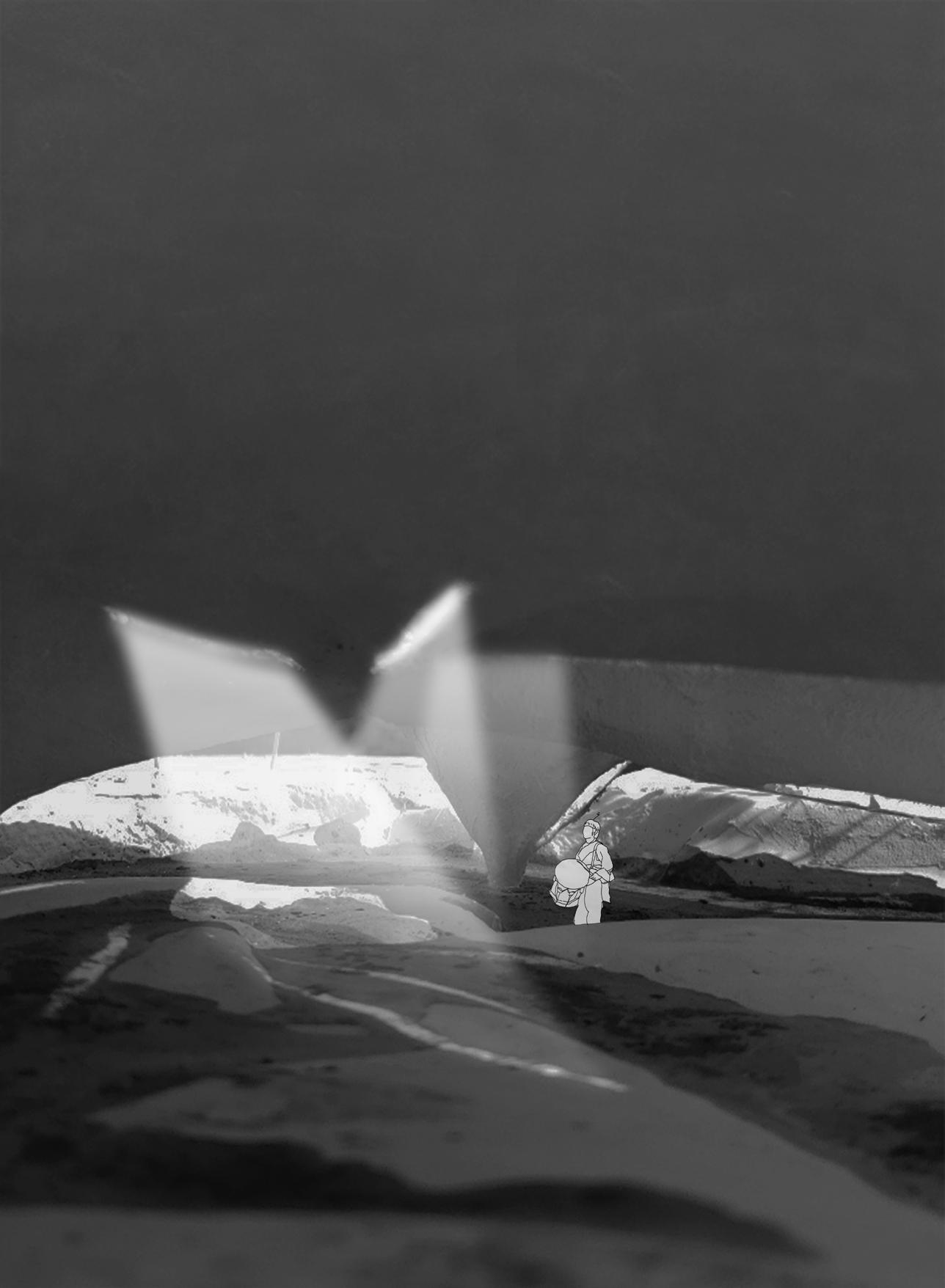

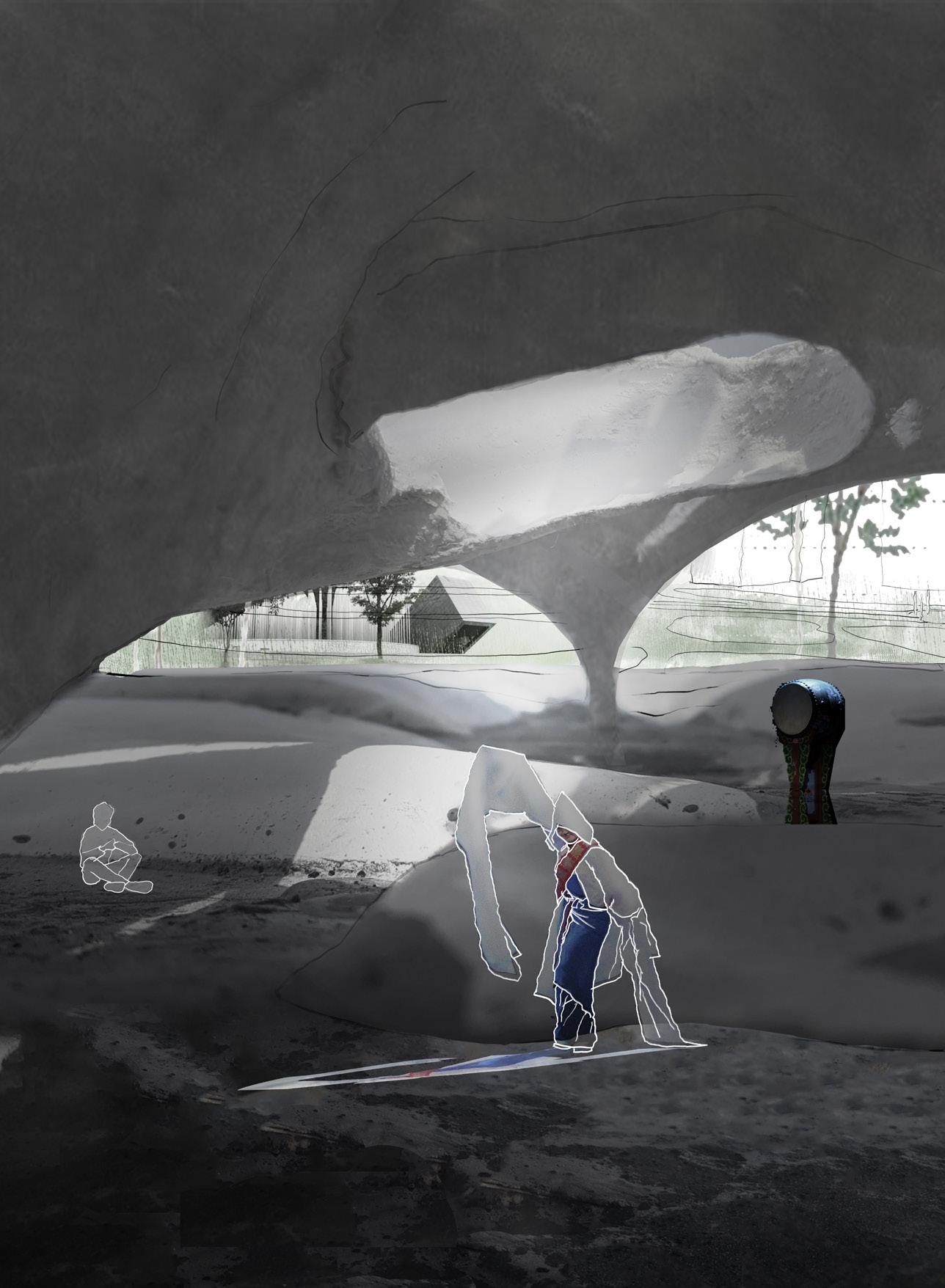

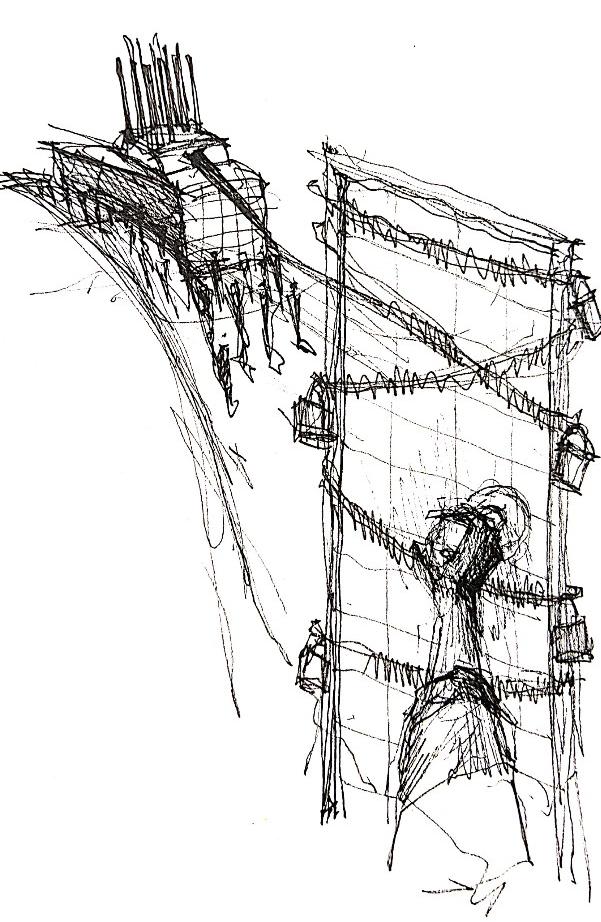

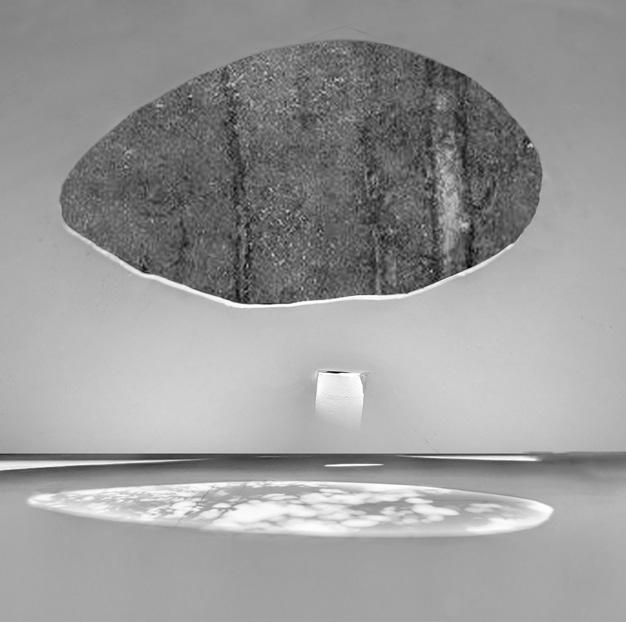

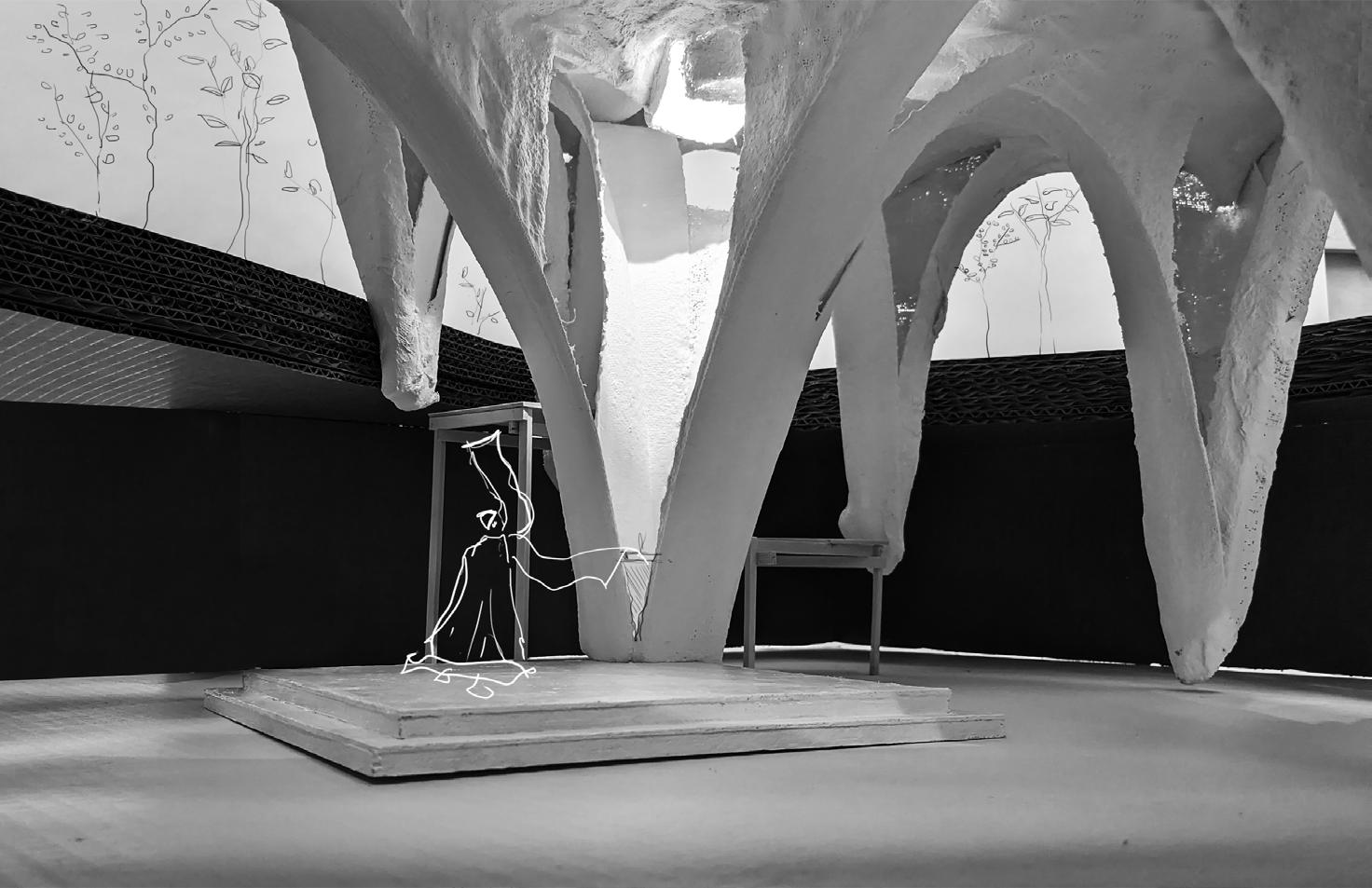

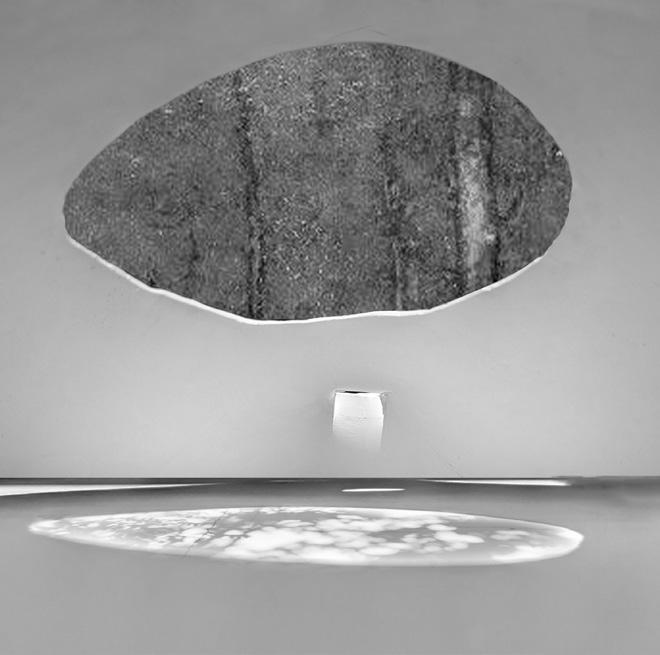

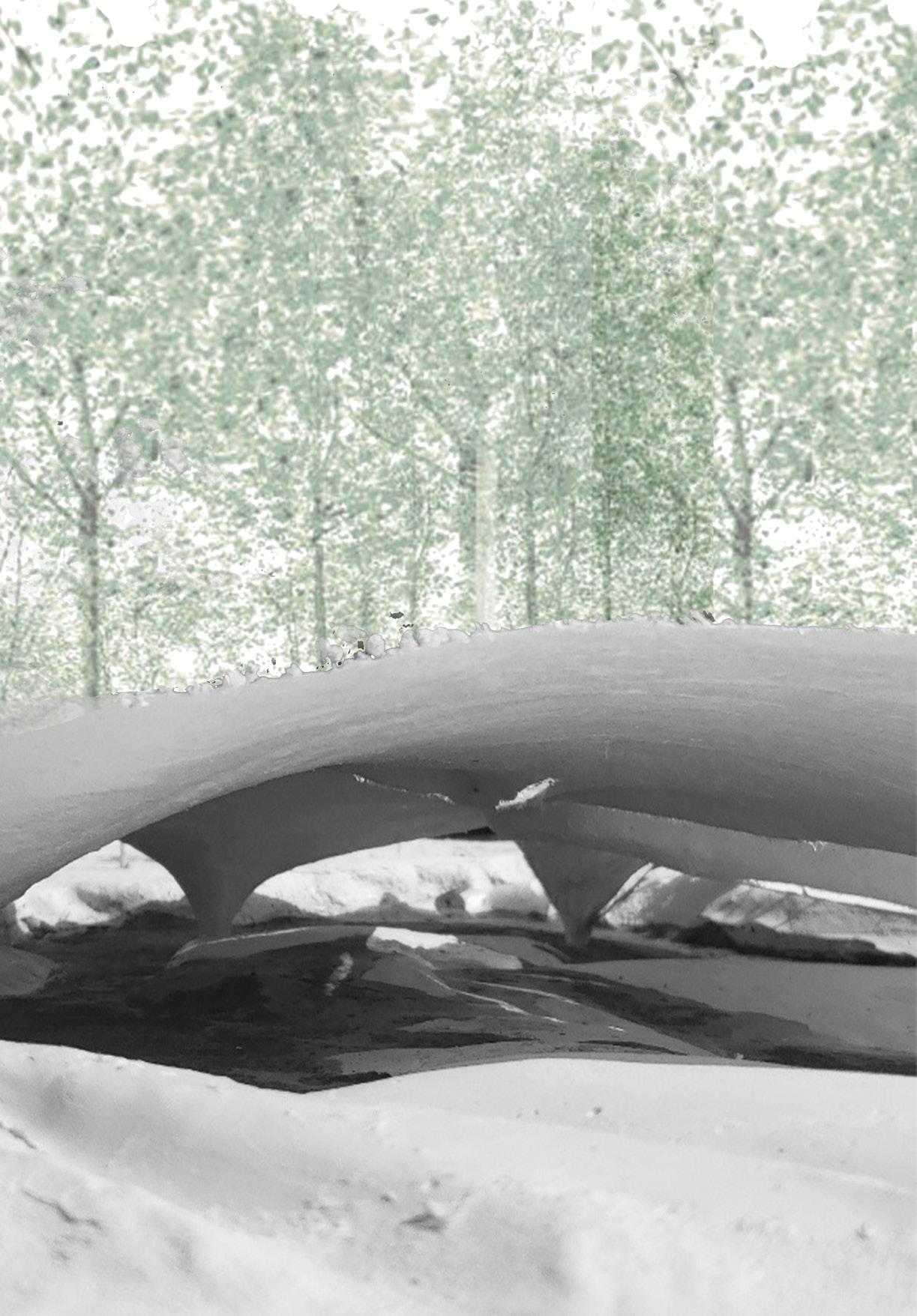

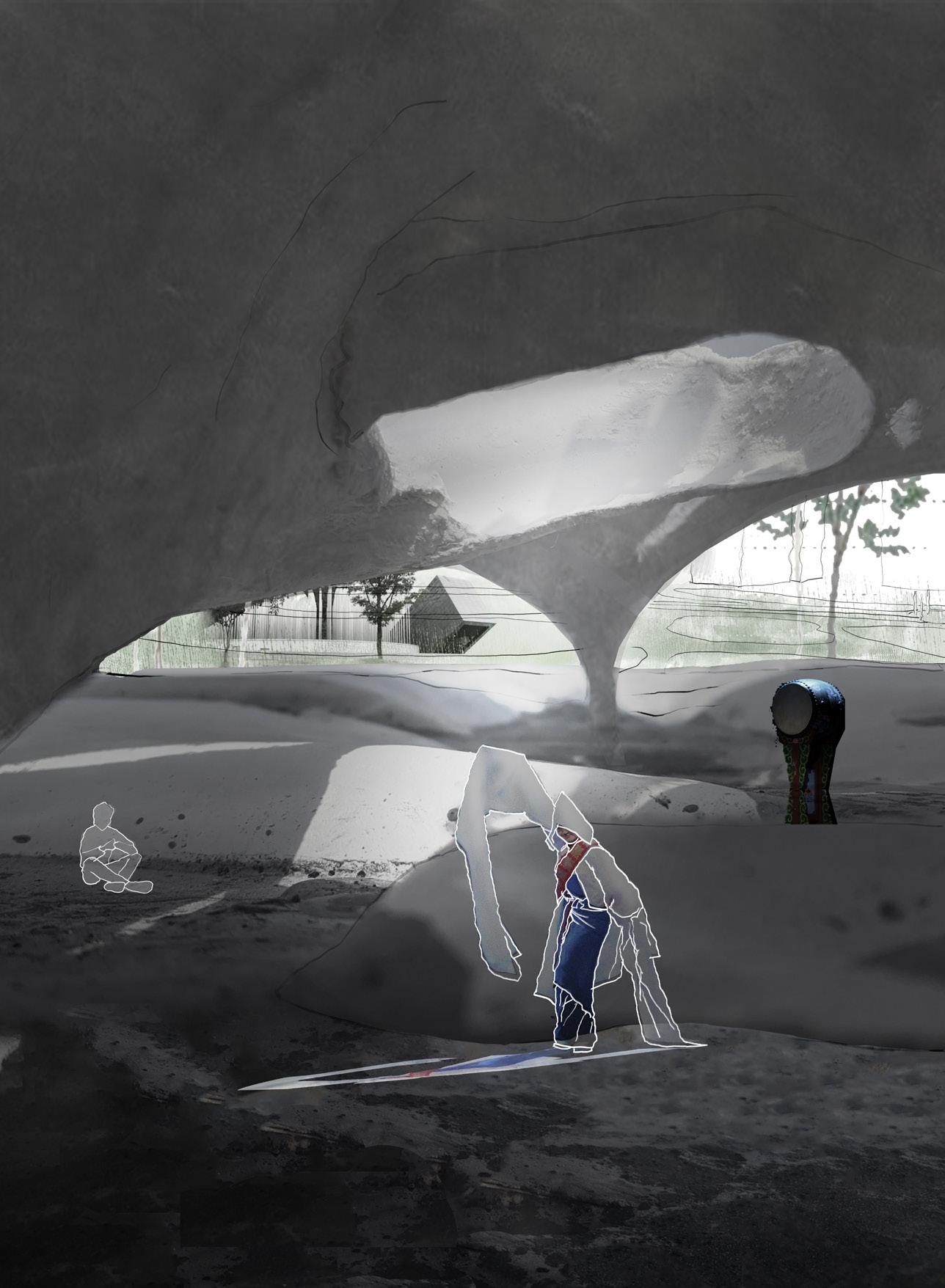

Cutting through the model revealed sectional quality of the project and how the top is where spirit and light gathers into the knot while the ground knot is where the dead inhabits. As one enters the space, the materiality of the landscape evokes the presence of the victims who passed away from shooting.

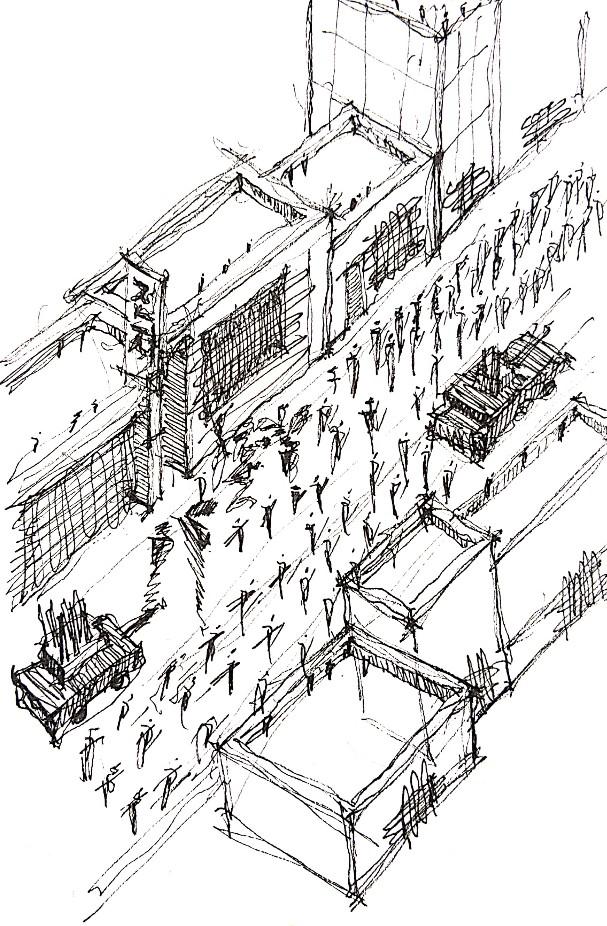

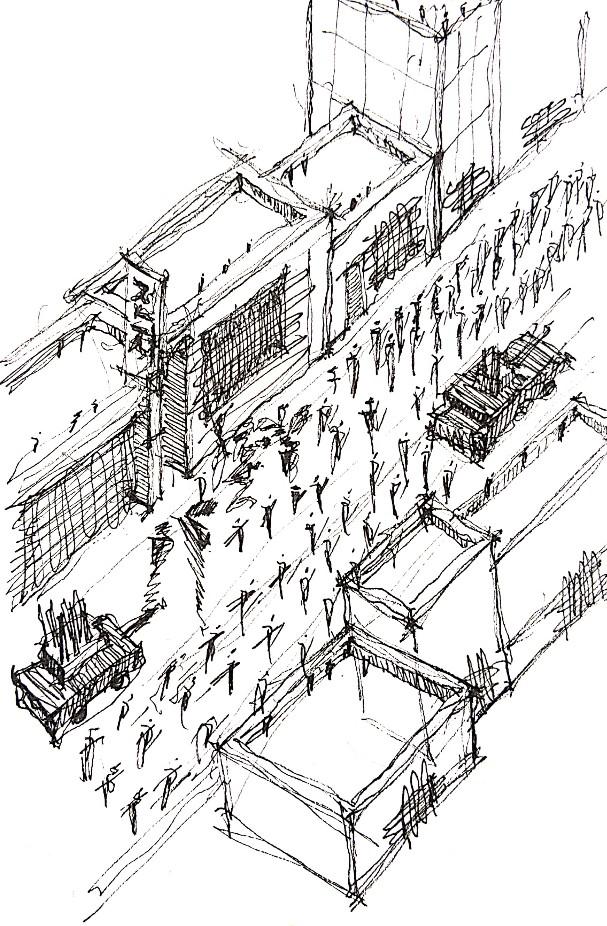

Fragments of sections are traced to construct long section that establishes relationships between dancer and viewers, sky and the ground, and the pavilion and memorial. There are two types of viewers, one closer to Mansin and the other further away who has less relationship to trauma. As one experiences the performance, the memorial sits as a backdrop constantly reminding about the tragedy.

40

41 Jisu Yang 4.0 Final Thesis Rambling

PROPOSED PAVILION

EXISTING MEMORIAL MOMUMENT

42 Plan 1 3

1. Entry / seat for public

2. Exit / seat for public

3. Dancer’s stage

2 4

4. Victim’s seat

43

Jisu Yang 4.0 Final Thesis Rambling

Roof plan

The site, currently existing as a memoral park, is charged with history and pain. Entering from the North East corner, the path leads to two radial memorial square that brings space of silence in an urban city to commemmorate the tragedy of the past.

44

45

1. Entry to the site

2. Existing Memorial Square

3 2 2

Rambling

3. Proposed Pavilion

1

Jisu Yang 4.0 Final Thesis

46

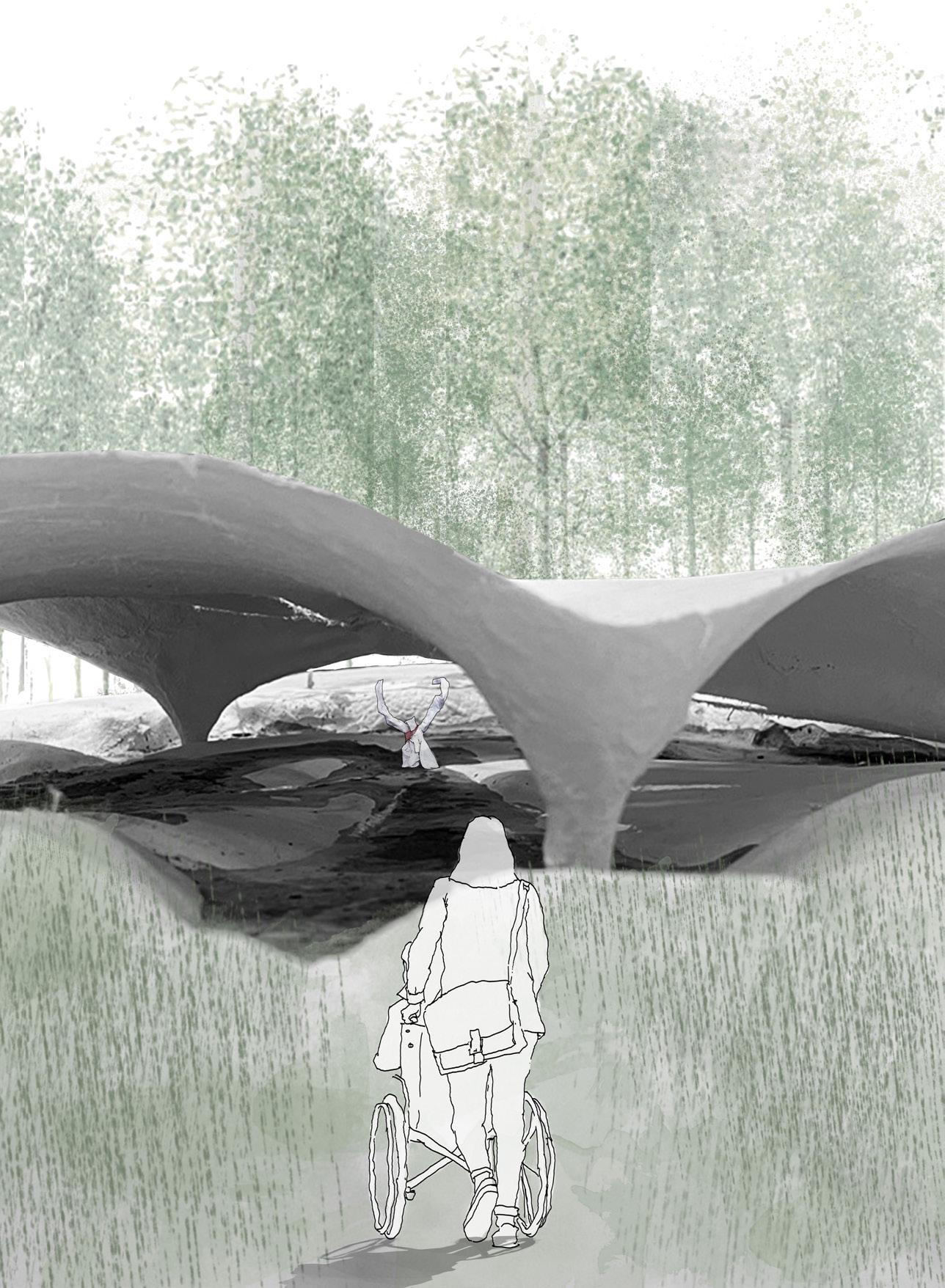

Every year on May 18, people in Gwangju host public performances at the May.18 Memorial Park to commemorate the tragedy of the massacre in 1980. More than 5000 university students, professors, and people in the street were killed by participating in the protest, fighting for democracy and freedom. This tragic event, silenced for more than three years, remained as a huge scar for the families of victims and survivors. A pavilion was built for performance relieving the pain of that trauma. People began to host public rituals and performances with Mansins from the area to collectively worship and remember the dead.

47

Jisu Yang

Thesis Rambling

4.0

Final

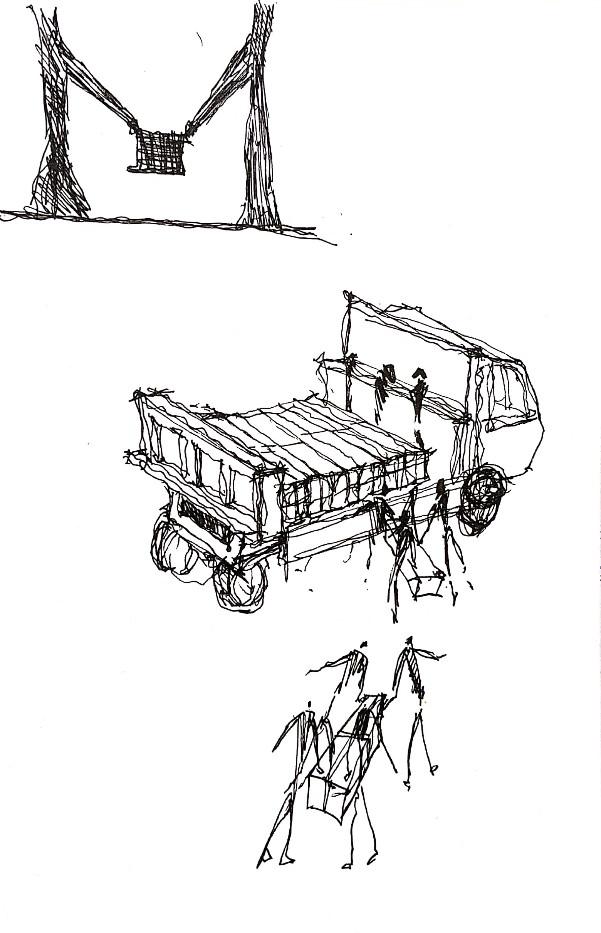

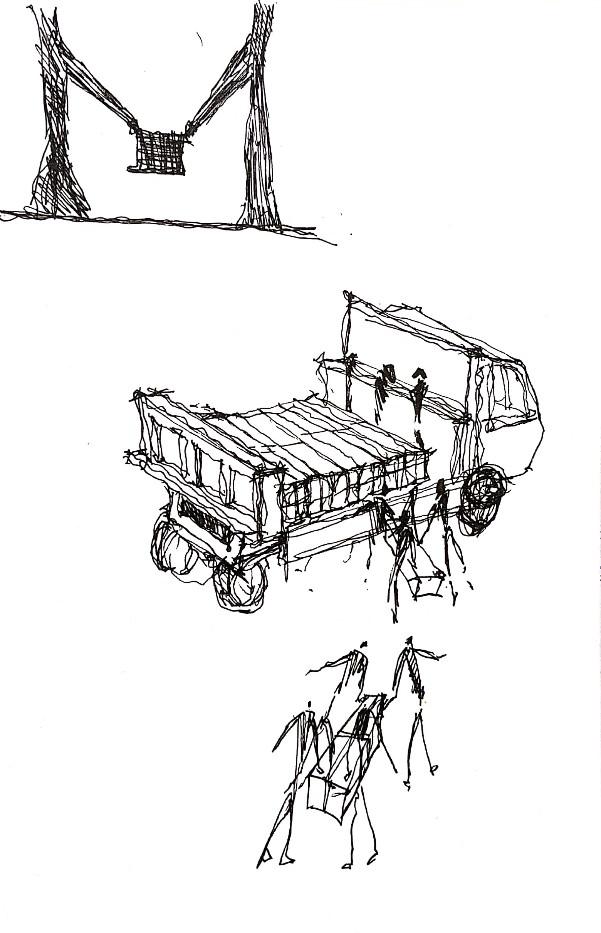

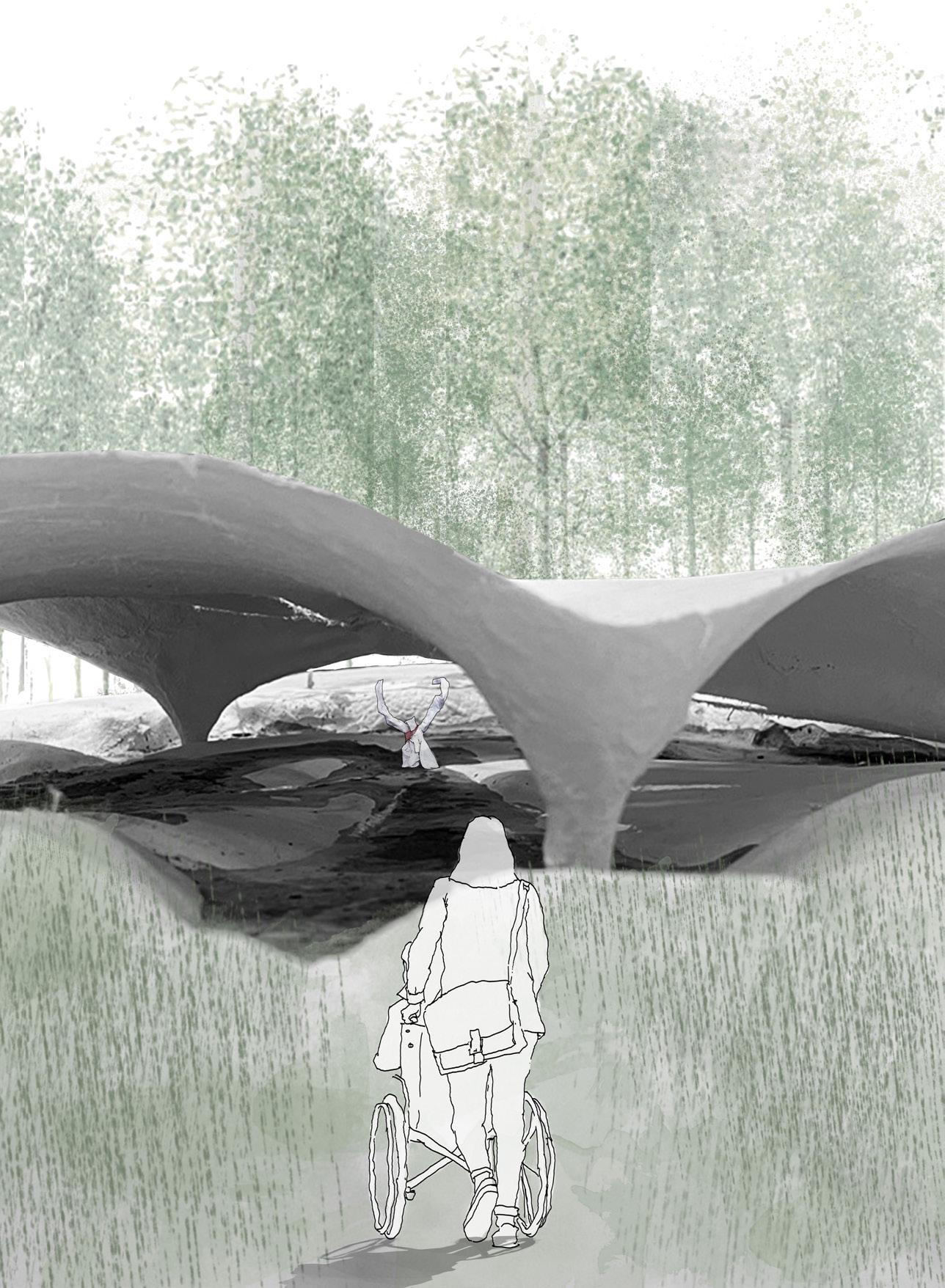

8:38am, Mansin starts stacking food from the old restaurant across the street: warm rice, beef bone soup, spring onion pancakes, carved apples- and peeled oranges. Mansin hears the voice of the door ringing. The 80 year old mother arrives.

She is on a wheelchair carried by her son. Her grandchildren get out of the car and start running around the field looking for dragonflies. Their mother forces them to stay silent.

48

8:45am, a group of people from the orchestra arrive. They carried large traditional drums in various sizes into the pavilion. They came to the center and install the instruments for the performance.

49

Jisu Yang

4.0 Final Thesis

Rambling

9am the pavilion opens. Approximately 20 people are invited to enter the space. The mother, the friend, the father, the son. Those who have direct losses from the massacre are encouraged to sit facing the Mansin in close proximity. Public members who are not directly related to the massacre inhabit the ground further away from the stage.

50

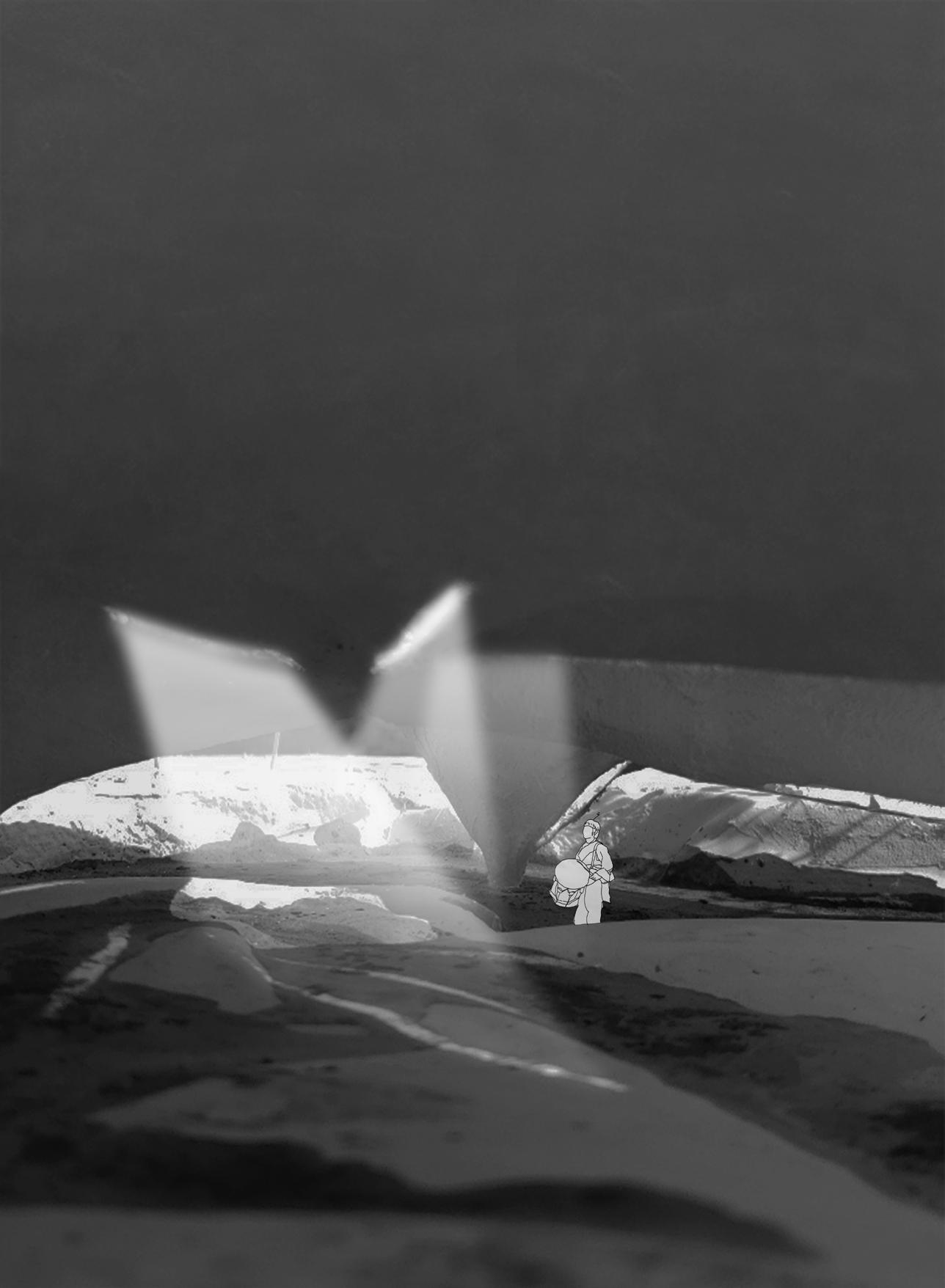

9:30am, the time they died. Mansin walks into the stage and lifts her arm up, with the white elongated fabric. Incidentally, the sun gathers into the center, illuminating her sleeves, bleeding through to her arms and to her hat. The dancer performs on the ground where the dead inhabit, and the memorial for the massacre stands in the background, constantly reminding one about the trauma that existed. A man wearing white hanbok starts drumming with his wooden stick.

The dance begins.

51

Jisu Yang

4.0 Final Thesis

Rambling

The film becomes ultimate representation of thesis in both showing process of construction and body in space. The film begins by capturing how plaster mixed with charcoal powder accummulate on the landscape, thousands of particles appearing on the surfaec. The last frames include the author’s body in the pavilion. The distance between dancer and the viewer from different shots is analogous with one’s relationship with the trauma of Gwangju Massacre.

52

53 Jisu Yang 4.0 Final Thesis Rambling

54

55

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wMrGlmg2DOE

Thesis Rambling

Jisu Yang

4.0 Final

56

Annotated Bibliography

Bae, Hye Soo. Mystic Pop-up Bar. Dir. Chang Geun Jeon. Perf. Jung Eum Hwang, Sung Jae Yook, Won Young Choi. Mystic Pop-up Bar. JTBC, 25 June 2020. Web.

Han, Kang, and Deborah Smith. Human Acts: a Novel. Granta Books, 2020.

Jung, Se Rang. The School Nurse Files. Dir. Kyoung Mi Lee. Perf. Yumi Jung and Joo Hyuk Nam. The School Nurse Files. 25 Sept. 2020. Web.

Kang, Han. The White Book. London: Portobello, 2018. Print.

Kendall, Laurel. Shamans, Nostalgias, and the IMF: South Korean Popular Religion in Motion. University of Hawai'i Press, 2009. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt6wr1sh. Accessed 23 Oct. 2020.

Park, Chan Kyoung. Manshin. Dir. Chan Kyong Park. Perf. Moon So-Ri, Ryoo Hyoung-Kyoung, and Kim Sae-Ron. At9 Film, 2014. Online.

Song, Ki Tae. “The Function and Theoretical Formalization of Shamanic Materials of Sitgimgut,” August 2007. https://doi.org/https://www.dbpia.co.kr/Journal/articleDetail?nodeId=NODE00905380.

Scarry, E. (1988). The Body in Pain. Place of publication not identified: Oxf. U.P.(N.Y.

57

58

59

60

Jisu Yang

Rhode Island School of Design B.Arch 2021

Jisu Yang

Rhode Island School of Design B.Arch 2021