IMAGINE HEALING ENVIRONMENTS WHERE CULTURE DOESN’T CONQUER OR COMMODIFY NATURE…

but merges with it

HEALING ENVIRONMENTS

HEALING ENVIRONMENTS:

Landscapes after Architectures and the Crises.

David Franco Co-Director of Architecture Graduate Programs

During the last few years, and in terms of its environmental, societal and health conditions, the world seems to be undergoing a dramatic turning point.

We are witnessing, in real-time, a series of traumatic transformations of what we previously saw as the natural state of things. The increasingly conspicuous effects of climate change with floods, fires, hurricanes, and, in general, extreme climate; the still lingering COVID health emergency with its haunting geopolitical implications, and the chilling precedent it sets for the future; or the crippling crisis of inequality that the neoliberal system has been brewing for more than three decades. These are just a few examples, certainly not all, of recent fractures within the usual narratives of progress and innovation that define contemporary culture and, of course, contemporary architecture. However, amid these uncertainties and fears, a distinctive notion emerges in the architectural discourse: the possibility of designing environments—architectures and landscapes—that, slowly, help us recover from these traumas and heal.

Trauma is not just related to harm, pain or sickness. It also indicates the violent intrusion of unexpected knowledge into our collective or individual psyche. A disturbance, a new event, a forceful transformation of what is normal, and an interruption of everyday life as we know it. Healing, from this perspective,

healing, from this perspective, is not just physical or psychological recovery. it also entails the reconstruction and reactivation of the narratives of normality.

is not just physical or psychological recovery. It also entails the reconstruction and reactivation of the narratives of normality.

Analogously to Felix Guattari’s Three Ecologies, healing occurs simultaneously on multiple levels. From the individual—physiologically and psychologically—, to the social, to the environmental.

Architecture and landscape architecture are uniquely equipped as design professions to react to that kind of complexity. They can activate the physiological and psychological sides of our bodies. They

can conceive spaces that evoke the memory of social trauma and conflict as a way of overcoming them. Finally, they can imagine healing environments where culture doesn’t conquer or commodify nature but merges with it. In this year’s lecture series at the Clemson SoA, we have opened conversations about architectural and landscape designs that heal our bodies and our minds, reactive our lost narratives as a society, and reconnect us with the non-human environment that surrounds us.

CONTENTS MESSAGE FROM THE DIRECTOR 6 DEVELOPING VISUAL REPRESENTATION STRATEGIES TO COMMUNICATE SCIENTIFIC PHENOMENA TO A BROADER AUDIENCE 8 NO PLACE TO PLAY : THE TRAUMA OF DISPOSSESSION + GENDERED IMPACTS TO ADOLESCENTS’ ACCESS TO PUBLIC SPACE 16 SOME QUESTIONS FOR CHARLESTON 26

SORRY, IT IS NOT FOR YOU… CELEBRATING THE IMPACT OF HARVEY GANTT 36 NARROW MARGINS: AN ESSAY ON A GENOVESE VILLA 48 AWARDS + HONORS 56

MESSAGE FROM THE DIRECTOR

Jim Stevens, AIA, Ph.D. Director + Professor

The School of Architecture (SoA) at Clemson University has a broad and diverse view of architecture.

Our faculty and students study, practice and publish on various topics, from the most technical to the most theoretical.

However, despite the spectrum of interest, the work is firmly rooted in bettering the built environment for communities and ecology.

This work includes maintaining a comprehensive graduate program in Architecture + Health that includes healthcare facilities and design and studying community health and well-being. Faculty in our Architecture program have led our students to consistent recognition in the American Institute of Architecture (AIA) Annual Committee On the Environment (COTE) design competition. In the summer of 2022, the School of Architecture hosted the National Environmental Design Research Association (EDRA) conference on Health in All Design.

The School of Architecture has experienced a year filled with reflection on the past and hopes for the future. We celebrated fifty years of the Villa, the Charles E. Daniel Center for Building Research and Urban Studies, and the 60th anniversary of Clemson University’s integration by hosting a “Legacy: Celebrating the Impact of Harvey Gantt,” a week-long series of speakers, panel discussions,

6 CLEMSON SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE

and an art exhibit that re-told the story of Harvey Gantt’s life and the events that changed South Carolina, Clemson, and the architecture community. This event discussed the healing that has taken place regarding integration and the work that remains. We celebrated the 50th anniversary of the Villa in Genoa, Italy, and at Clemson’s Lee Gallery, located in Lee Hall. Faculty and students hosted “La Villa-Le Storie: The First Five Decades,” an exhibition that celebrated the work of Genoa alumni with work submitted by individuals who have visited the Villa since its founding in 1973. Students, faculty, alumni, and friends of the Villa joined us in Genoa for a week-long celebration of open houses, student work exhibitions, a celebration, and dinner at the Villa and Castello Bruzzo. Both celebrations clarified the importance of the SoA community and our collective power to heal.

It is fitting that this year, our lecture series and publication focus on Healing Environments by interrogating how architecture and landscape architecture can heal communities’ bodies and minds. As we continue to experience the aftermath of COVID-19, accelerating impacts of global climate change and social and political instability, we find no better topic to place our collective efforts. The articles provided in this publication give insight into how architecture and landscape architecture can confront today’s challenges. The students’ thoughtfulness in the School of Architecture and the work contained here offers hope for a sustainable and prosperous future.

7 HEALING ENVIRONMENTS | SUMMER 2023

DEVELOPING

VISUAL REPRESENTATION

STRATEGIES

TO

COMMUNICATE

SCIENTIFIC PHENOMENA

TO BROADER AUDIENCE A

Matthew Nicolette, Andreea Vasile-Hoxha, Ergys Hoxha, and Annie Steele

Photography by Andreea Vasile-Hoxha and Matthew Nicolette

9

Communication is crucial for a project’s successful design, implementation, and performance. Landscape architects are hired as experts in the built environment to produce creative solutions to complex problems that directly affect the health of our communities. The potential experiential, ecological, social, and economic impacts are communicated to the client and stakeholders to foster the necessary consensus to fund and execute responsible design effectively. The stakeholders expect us to tell a story while defending and advocating for a specific point of view that aligns with our values within the project’s parameters. We train to communicate effectively and iteratively enhance these skills to reach a broader and more diverse audience.

Like landscape architects, scientists rigorously test ideas through an iterative process requiring creativity and experimentation. Variables are continuously adjusted to achieve confidence in the results of the experiments that ultimately prove (or disprove) the hypothesis. Scientists report their results through peer-reviewed publications, where the principal investigator communicates the facts without complicating the results with values, beliefs, or judgment (Diets, 2013). Scientists perceived as straying too far from the ‘hard facts and figures’ and advocating for a specific belief or value risk politicizing the message. Politicization potentially compromises the integrity of their past, current, and future research. The audience for these communications is usually a subset of scientists interested in the field of study and inherently trust

10 CLEMSON SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE

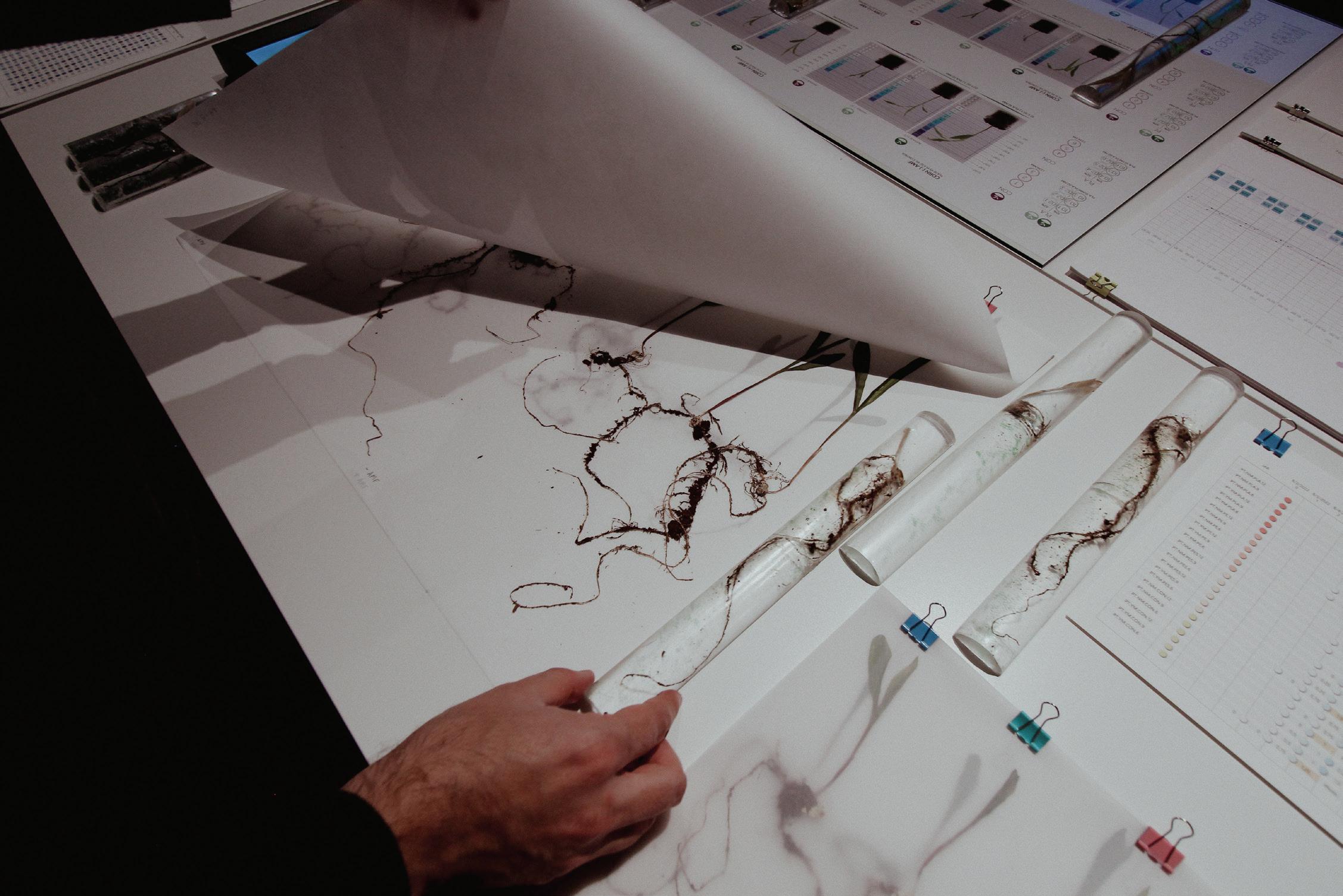

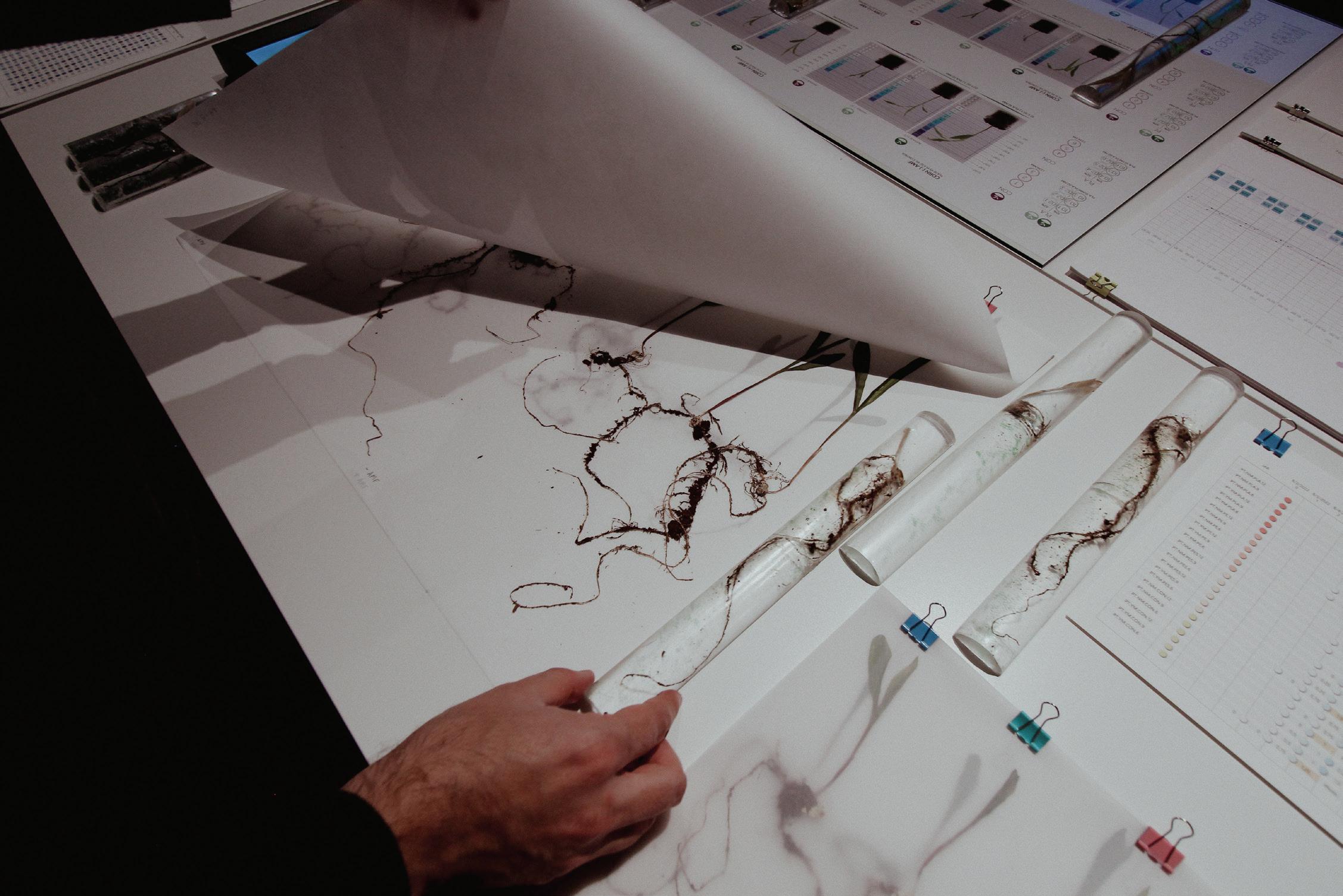

BELOW: Artifacts arranged for the After Plastics exhibit at the 2022 Lisbon Architecture Triennale.

the publication process. The outcome of this method is scientific knowledge that is too often opaque and inaccessible to the public. A broader audience must rely on journalists to communicate the results outside these forums, where the message is increasingly presented to support a belief or an ideological value system at the expense of scientific knowledge (Eveland, 2013). This misrepresentation clouds the results and can lead to mistrust in the scientific community and consequently have a deleterious effect on society.

Landscape architects train to

communicate and engage stakeholders. It is a profession that utilizes art and science, requiring a broad knowledge base and expertise (Watermen, 2015). We are less limited by the constraints of scientists allowing us to fill the role of communicator more effectively. This is an opportunity to engage with scientists on ecologically and socially relevant topics to increase scientific transparency, transfer scientific knowledge to a more diverse audience, and help repair or mitigate the damage done by misinformation.

As a case study, and in collaboration with KALA.studio for the

11 HEALING ENVIRONMENTS | SUMMER 2023

ABOVE: Corn plants are displayed to encourage public engagement and interaction with the scientific process.

2022 Lisbon Architecture Triennale - TERRA, we presented the creative inquiry, After Plastics. The exhibit is an extension of Andreea Vasile-Hoxha’s 2021 ASLA Student Honor Award-winning project that addresses microplastics’ potential impact on post-glacial landscape ecologies, and the role landscape architects can play in future development.

Microplastics are becoming ubiquitous through atmospheric dispersal, and evidence suggests that they interact with mycelium and plant roots affecting plant growth, nutrient and heavy metal uptake, and soil structure (de Souza Machado, 2019; Wang, 2020; Azeem, 2021). The project team designed a series of controlled experiments to visually communicate previously published scientific studies demonstrating the effects of microplastics on plant growth. We took an epistemological approach to experimental design, focusing on visualization strategies to make the topic approachable to a more diverse audience. Rather than focusing solely on presenting the content of the experimental results,

we introduced the process and representation of scientific study as a creative endeavor that clarifies scientific phenomena and promotes future lines of inquiry across disciplines.

To engage the audience and interpret the complexities of the scientific process, we focused on the visualization of the epistemological artifact (Evagorou, 2015). The experiments evaluate the effects of three types of microplastics (PES- polyethersulfone, PE-polyethylene, and PLA- polylactic acid) and a mycelium mix on the growth of corn plants. We use corn as a model organism for its availability, known mycelium interaction, and growth rate. We constructed a laboratory containing grow boxes for the plants, lab benches for experimentation, and areas for documentation, with every element designed for ease of representation and optimal visualization. Germination and growth rates were measured daily while we photographed plants at predetermined intervals. A second

12 CLEMSON SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE

AT RIGHT: Professor Matt Nicolette and graduate student Annie Steele discuss the exhibit with Triennale visitors.

round of experiments evolved from information gleaned from the original study. Plants were harvested for stereo microscopy, fixing the specimens in resin and pressing the plants to visualize root structures. Although a small sample size, our initial results were consistent with previously published studies showing a synergistic relationship between microplastics and mycelium on plant growth. We also produced a series of artifacts from the microscopic to macroscopic scale representing various phases of the experiments.

These displays ran for one month

at the 2022 Lisbon Architecture Triennale. The curation of the one-room exhibit accounted for the knowledge that working memory is limited and access to stimuli has increased with current technology creating more and more competition for this precious resource (Lupia, 2013). The exhibit consisted of a central table with artifacts, data sets and results, illustrative posters, slide shows, and a narrated video projected on the entry wall. We presented the research process and results through strategically placed artifacts without value judgment. The interactive display engaged the audience and

13 HEALING ENVIRONMENTS | SUMMER 2023

working memory is limited and access to stimuli has increased…

WITH CURRENT TECHNOLOGY CREATING MORE AND MORE COMPETITION FOR THIS PRECIOUS RESOURCE

14 CLEMSON SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE

allowed the curious to spread out and absorb areas of interest, leading to the self-discovery of presented data sets. The exhibit audience handled and manipulated the artifacts, often leading to discussions amongst themselves and questions for the presenters.

This case study demonstrates that visual representation strategies can teach various audiences complex scientific phenomena and topics. Focusing on the epistemology of the process instead of concentrating narrowly on representing the results can make these topics approachable to a broader audience, thus expanding the study’s reach and promoting future scientific and artistic exploration. Further investigation is ongoing to explore representation strategies and measure the responsible transfer of knowledge from the primary scientific source to the audience.

WORKS CITED

1. Azeem, et al. (2021, November 2). Uptake and Accumulation of Nano/Microplastics in Plants: A Critical Review. Nanomaterials(Basel). 11(11):2935.

2. de Souza Machado, et al. (2019, April 25). Microplastics Can Change Soil Properties and Affect Plant Performance. Environmental Science Technology. 53(10), 6044-6052.

3. Dietz T. (2013, August 20). Bringing values and deliberation to science communication. PNAS, 110(suppl. 3), 1408114087.

4. Evagorou, et al. (2015). The role of visual representations in scientific practices: from conceptual understanding and knowledge generation to ‘seeing’ how science works. International Journal of STEM Education, 2(11).

5. Eveland WP, & Cooper KE. (2013, August 20). An integrated model of communication influence on beliefs. PNAS, 110(suppl. 3), 14088-14095.

6. Lupia A. (2013, August 20). Communicating science in politicized environments. PNAS, 110(suppl. 3), 14048-14054.

7. Wang, et al., (2020, September). Interactions of microplastics and cadmium on plant growth and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal communities in an agricultural soil. Chemosphere. 244, 126791

8. Waterman, Tim (2015). The Fundamentals of Landscape Architecture. Bloomsbury Publishing

15 HEALING ENVIRONMENTS | SUMMER 2023

PLAY:

The trauma of dispossession + gendered impacts on adolescents’ access to public space

Lyndsey Deaton

17

NO PLACE TO

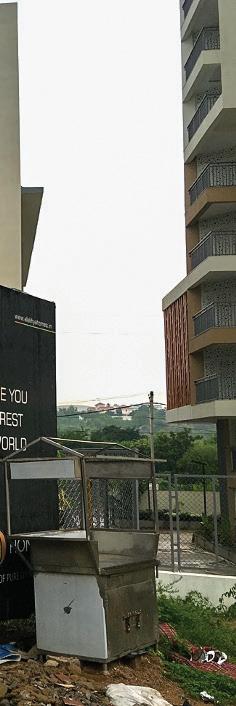

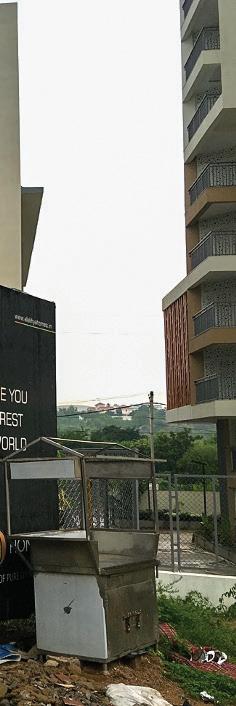

FIGURE 1: Elite housing communities advertise exclusive architectures that help residents “forget [the] rest of the world,” (Source: Author, 2019).

Assistant Professor in Architecture + Health

Sitting in a parked autorickshaw on the lane outside of his home in Ishaan Nagar, India, 14-year-old Manish clearly explained the situation to Research Assistant Prakash:

Prakash: After coming back home do you play?

Manish: No

Prakash: Why?

Manish: There is no place to play.

Over the course of three years of fieldwork in Hyderabad, India, and Manila, Philippines, I witnessed firsthand how neoliberal urban development marginalizes lower-income communities. One experience was especially illuminating. On my daily commute by scooter to the high-tech enclave of Cyberabad in Hyderabad, I often took a shortcut through a community of about fifty families tucked away behind two gated apartment complexes. Over the years, as I rode through this area, I watched as the government displaced the last remnants of what had once been a traditional village to make

room for new apartment construction and forced the villagers who did not leave to settle informally along the public street. Often as I passed, I could see women seated on the curb fanning the flames of their small charcoal fires in preparation for lunch, while their children, with no other place to play, chased each other in the street, dodging cars, rickshaws, and the occasional push-cart vendor. The tarpaulin tents these families called home spanned the width of a public planting strip and sidewalk (a space about nine feet wide), and without private courtyards, domestic activities such as cooking and laundry were forced to take place in the street. Meanwhile, the white concrete towers of the gated enclave, with their wide balconies, loomed over the remaining trees, providing a stark contrast to the constant bustle of people living beneath their canopy.

While acknowledging that these two communities have a complex and deeply dependent relationship, interdependence says nothing about equity and health. Indeed, viewing these

18 CLEMSON SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE

communities together as a system raises important questions about who gains from planned development, and at what cost. Unlike more longstanding and accepted uses of forcible acquisition — for example, when a government acquires land for a civic project such as a dam or a highway — the

government displaced these villagers to make room for a private apartment complex, which was justified based on its economic-development potential and theories of trickle-down economics (Cyberabad Development Authority 2003). And yet, these elite housing communities such as

19 HEALING ENVIRONMENTS | SUMMER 2023

FIGURE 2: An altered photograph shown in the exhibition taken by a teen participant in which she describes avoiding the basketball court because of the older men that cat-call from the bleachers (CI students and Adriana, 14 y/o, 2018).

Rajeev Nagar in which a teen participant described the highway adjacent to his house bisecting his spatial mobility and limiting his access to the park and temple (Source: CI students and Nivant 12y/o, 2019).

Nivant only went to school and the snack shops by himself because of fears. He was very scared of the road. The year prior, his teacher was hit by a lorry (semi-truck) in front of the school and was no longer able to teach.

He also never went in the valley behind the garage or explored that area because he feared snakes, bullies, and ghosts. He feared the neighbors too. He said that in Rajeev Nagar people often drank and older youths fought in the street. He walked to the shops alone but never at night.

Alekhya Homes that dispossessed villagers in Nanakramguda, one of the sites in my research, advertise exclusive architectures that help residents “forget [the] rest of the world.” In a similar manner, cities around the world (including South Carolina), are increasingly expanding the definition of “public good” to dispossess poor communities and implement economic-development policies that

benefit the rich (Robinson 2003).

As these exclusive architectures encroach and replace very low and often informal communities through dispossession processes, the power of land speculation devalues safe and accessible public spaces. Thus, after dispossession, these communities are typically crowded, incomplete, low-rise developments without formal public

20 CLEMSON SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE

5 Minute Walking Radius Map Legend Dangerous Walking Route Signi cant Location Home He revealed that he went with his family to the temple across the street. He said enjoyed it because there was a tree, and it was the only time that he felt close to nature outside of school. He mostly played alone in the parking area in front of the bank. He played cycling, carrom board, and on the phone. Sometimes he played games with his mother and his brother since he didn’t have many friends that lived nearby.

four lived in a single room in the parking garage of an o ce building with a Bank of India covering half of the ground level. His father was the parking garage attendant and night watchman.

wall.

parents

cross alone.

highway

became

border

his spatial range and limited him

playing with friends who lived on his side of the street.

Nivant and his family of

Their apartment was approximately 15 m2 and the only furniture was a TV on the oor and single bed against the

Since the road was so dangerous, his

did not allow him to

The Gachibowli-Miapur

then

a

of

to

FIGURE 3: An annotated map of

low-income adolescents are susceptible to developmental risks if they do not have access to safe, comfortable, and convenient public space

21 HEALING ENVIRONMENTS | SUMMER 2023

spaces and few open spaces.

The stakes inherent to neoliberal policies are extensive — especially as reflected in the experience of the built environment. This is particularly the case when it comes to the lives of women and children. It is known, for example, that a decline in the quality of their built environment more seriously affects women’s and children’s health more than other groups, and that low-income adolescents are susceptible to developmental risks if they do not have access to safe, comfortable, and convenient public space. While the criticality of public space for adolescents’ cognitive development, identity formation, and mental health is firmly established (Chawla 2002, Kyttä et al 2018, Spencer and Woolley 2000, Ward 1978) less is known about how they cope with the trauma of dispossession reducing access to the public spaces in which they would otherwise play. Manila and Hyderabad represent vivid cases where low-income communities experience the most violent and extreme forms of dispossession, often to crowded fringe resettlement communities far from where they originally

lived, worked, and socialized. The research highlights the perspectives of 50 adolescents from seven dispossessed communities in India and the Philippines.

(Source: Author, 2023).

22 CLEMSON SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE

FIGURE 4, FIGURE 5 (OPPOSITE): Parents, students, and community members at the Monaghan Mill Gallery exhibition premier in Greenville, SC in April 2023

To expand awareness past academic silos and bring these issues to parents, students, and our communities, my students and I presented the creative inquiry, No Place to Play at the Monaghan Mill Gallery in Greenville and the exhibition will continue with three additional shows at art galleries across South Carolina in Charleston, Columbia, and Clemson this year. With a cadre of Clemson undergraduate and

graduate students, we curated a selection of raw data from my large, multi-sited, trans-national study documenting how adolescents use public space in dispossessed communities. For the exhibition, students selected, altered, and captioned photographs taken by teen participants, constructed several 1”:20’ wooden models of significant community spaces, and annotated maps of each

23 HEALING ENVIRONMENTS | SUMMER 2023

community documenting teens’ spatial mobility and affordance.

Students found the gendered impacts of dispossession to be especially concerning and leveraged the exhibition to stress the stark disparities between girls’ and boys’ spatial mobilities. The research revealed that that teenage boys play in places three times farther away from their house than girls. Girls choose not to play in public places in dispossessed communities because they feel unsafe, uncomfortable, and the spaces are largely inaccessible to them. Their perspectives reveal a tangle of factors including cultural norms. In the final section of the exhibition, students reflect on the safety, comfort, and convenience of public places for teens in South Carolinian cities. Through their work, they hope to underscore the value of quality public space and bring awareness to the disproportionate impacts of dispossession on teenage girls by sharing their perspective of life with no place to play.

As neoliberal policies and

dispossession practices spread globally, especially in rapidly growing areas such as the Greenfield Corridor (a 274-mile route that connects Atlanta to Charlotte), architects, landscape architects, and planners are positioned to reduce continued trauma and ignite the healing process. The healing environments that design professionals imagine should incorporate a spectrum of formal to informal public places for adolescents to hangout or play. Designers have the skills and awareness to highlight the critical importance of safe, comfortable, and convenient public places for adolescents in low-income communities. Most residents in dispossessed communities rely on “everyday” public places, especially the street, which are often critically undervalued behavior settings under neoliberal urban planning schemes.

Learn about our next show through our website:

lyndseydeaton.com/no-place-to-play /

24 CLEMSON SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE

REFERENCES:

Chawla, L. (2002). Growing up in an Urbanizing World. London: Earthscan Publications.

Cyberabad Development Authority (2003). Master Plan for Cyberabad Development Area Authority. Government of Telangana.

Kytta¨ M, Oliver M, Ikeda E, et al. (2018) “Children as urbanites: Mapping the affordances and behavior settings of urban environments for Finnish and Japanese children,” in Children’s Geographies 16(3): pp. 319–332.

Robinson, W. C. (2003) Risks and Rights: The Causes, Consequences, and Challenges of Development-Induced Displacement. Washington DC: The Brookings Institution-SAIS Project on Internal Displacement.

Spencer, C., and H. Woolley. (2000). “Children and the City: A Summary of Recent Environmental Psychology Research,” in Child: Care, Health, and Development 26 (3): pp. 181–198.

Ward, C. (1978). The Child in the City. London: The Architectural Press.

25 HEALING ENVIRONMENTS | SUMMER 2023

FIGURE 5B: Parents, students, and community members at the Monaghan Mill Gallery exhibition premier in Greenville, SC in April 2023 (Source: Author, 2023).

SOME QUESTIONS

FOR CHARLESTON

—Rebecca Solnit, Wanderlust: A History of Walking Bradford Watson

Director of the Clemson Architecture Center Charleston

“Many people nowadays live in a series of interiors...disconnected from each other. On foot everything stays connected, for while walking one occupies the spaces between those interiors in the same way one occupies those interiors. One lives in the whole world rather than in interiors built up against it.”

Non-Indigenous occupation of the peninsula of Charleston began in the 1670s, nearly 200 years before the first streetcar and 230 years prior to the first automobile to drive in the city. The city grew to expand beyond the peninsula and now comprises over 800,000 people in the metro area, growing at a rate of 33 people per day. This growth and sprawl are possible because of the vast infrastructure of roads to support car-based commuting. And while the developed area of the peninsula has increased over this time with the filling in of marsh lands and the building of structures that can span over the soft soils, it is still approximately only 5 square miles in size. Downtown Charleston continues to add new housing to address the needs of people wanting to live in the vibrant city. The increasing needs of housing and the desire for individual motorized transportation have a significant impact on the scale of the city. As we think about the future of Charleston, can we learn from the scale and pace of the city prior to the car? What if city planning and growth started with health as the objective? And not just physical health, but holistic health, a real triple bottom line health? In a place that will be significantly impacted by global warming, how can planning and growth reduce our carbon footprint for long term health of the region? Can the future of Charleston be a model as a healing environment as we look to a zero-carbon future?

27 HEALING ENVIRONMENTS | SUMMER 2023

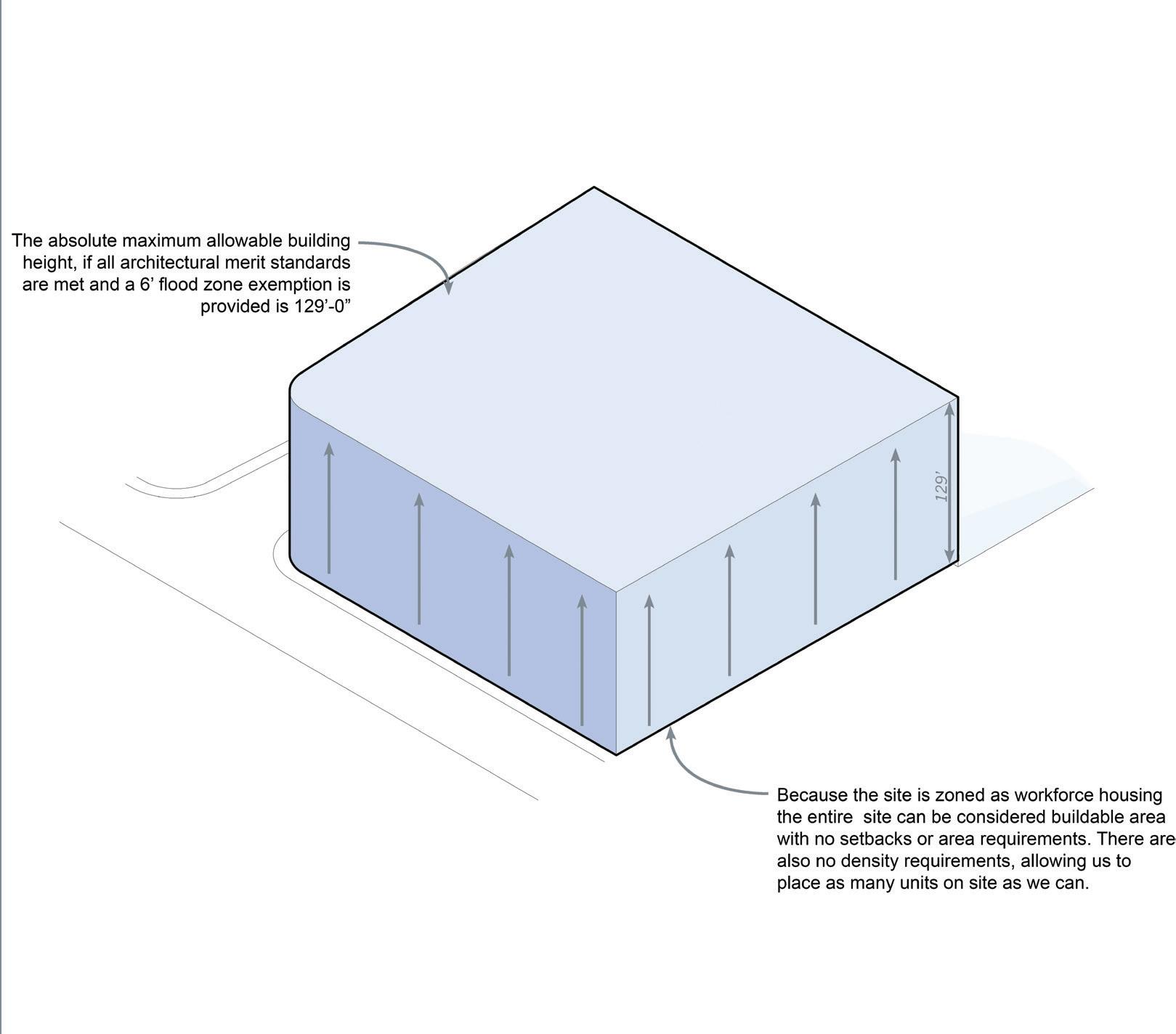

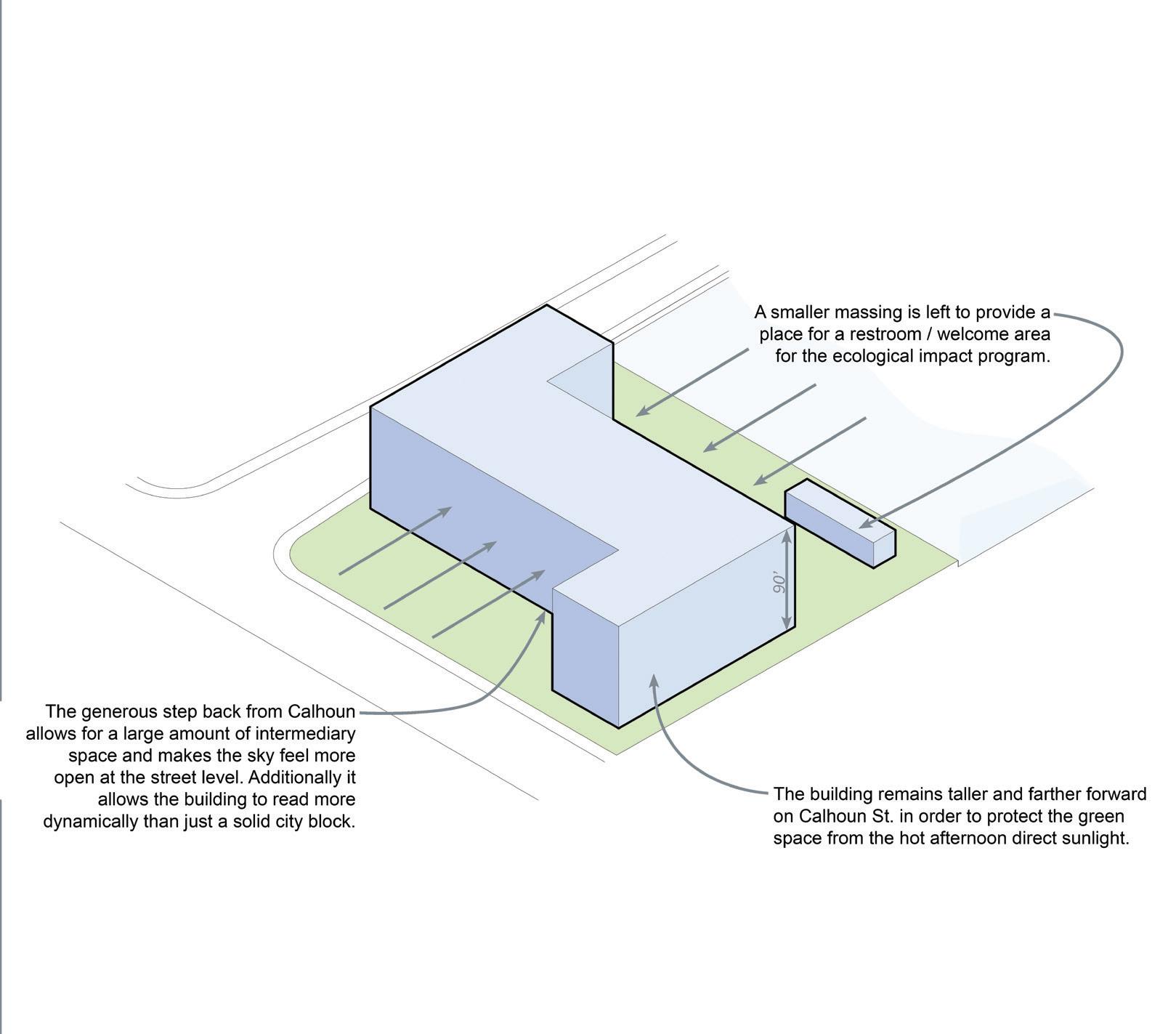

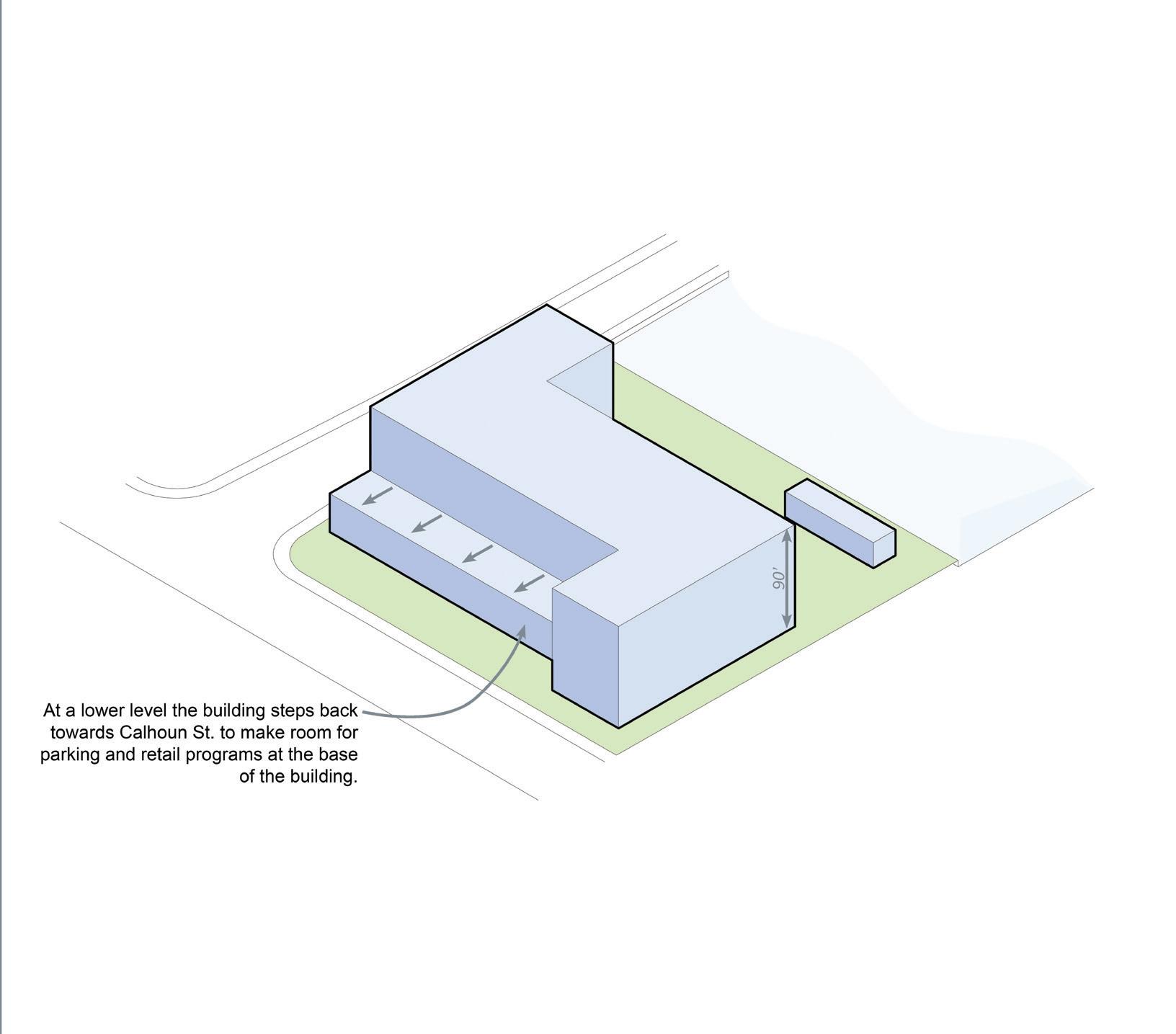

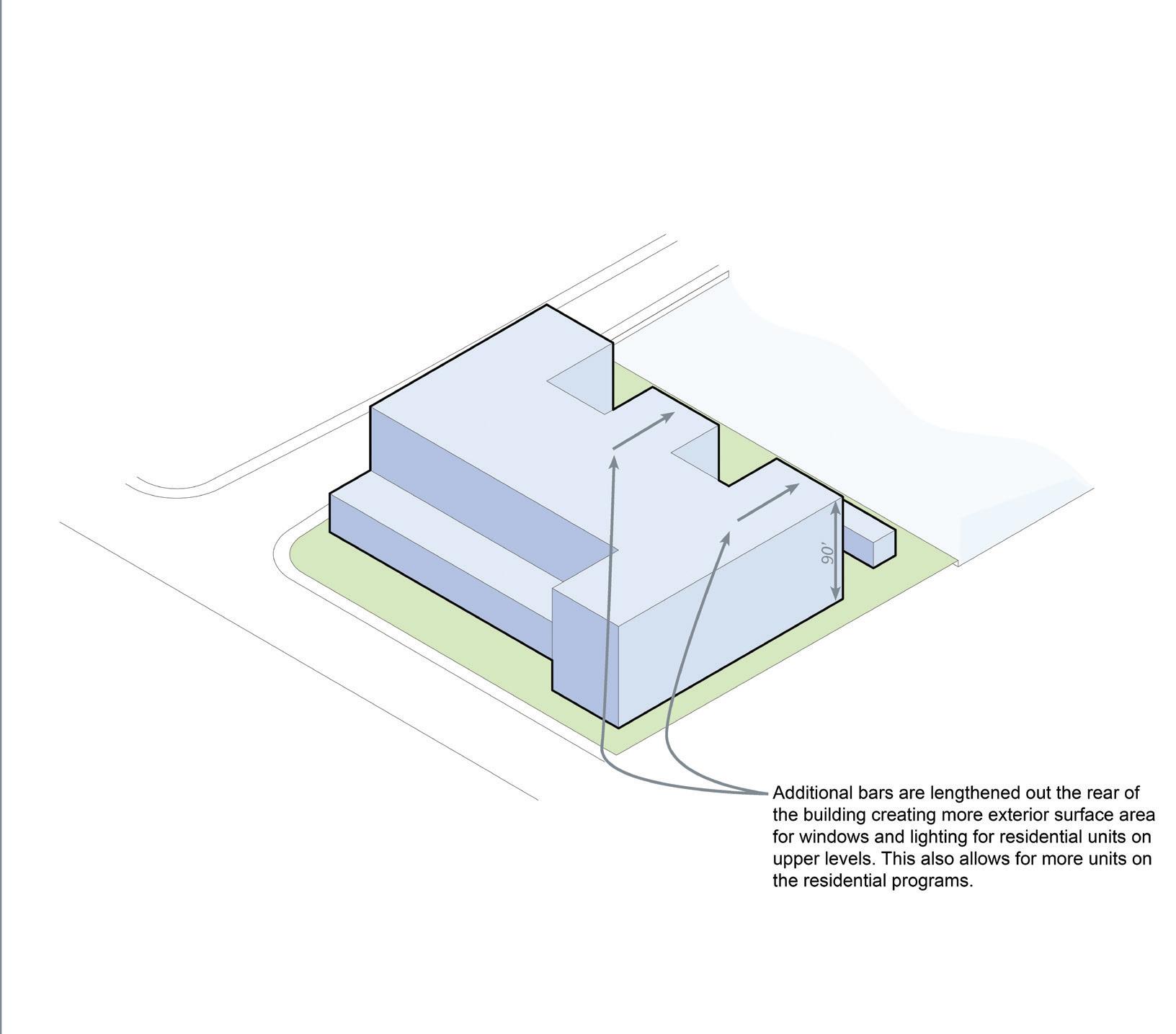

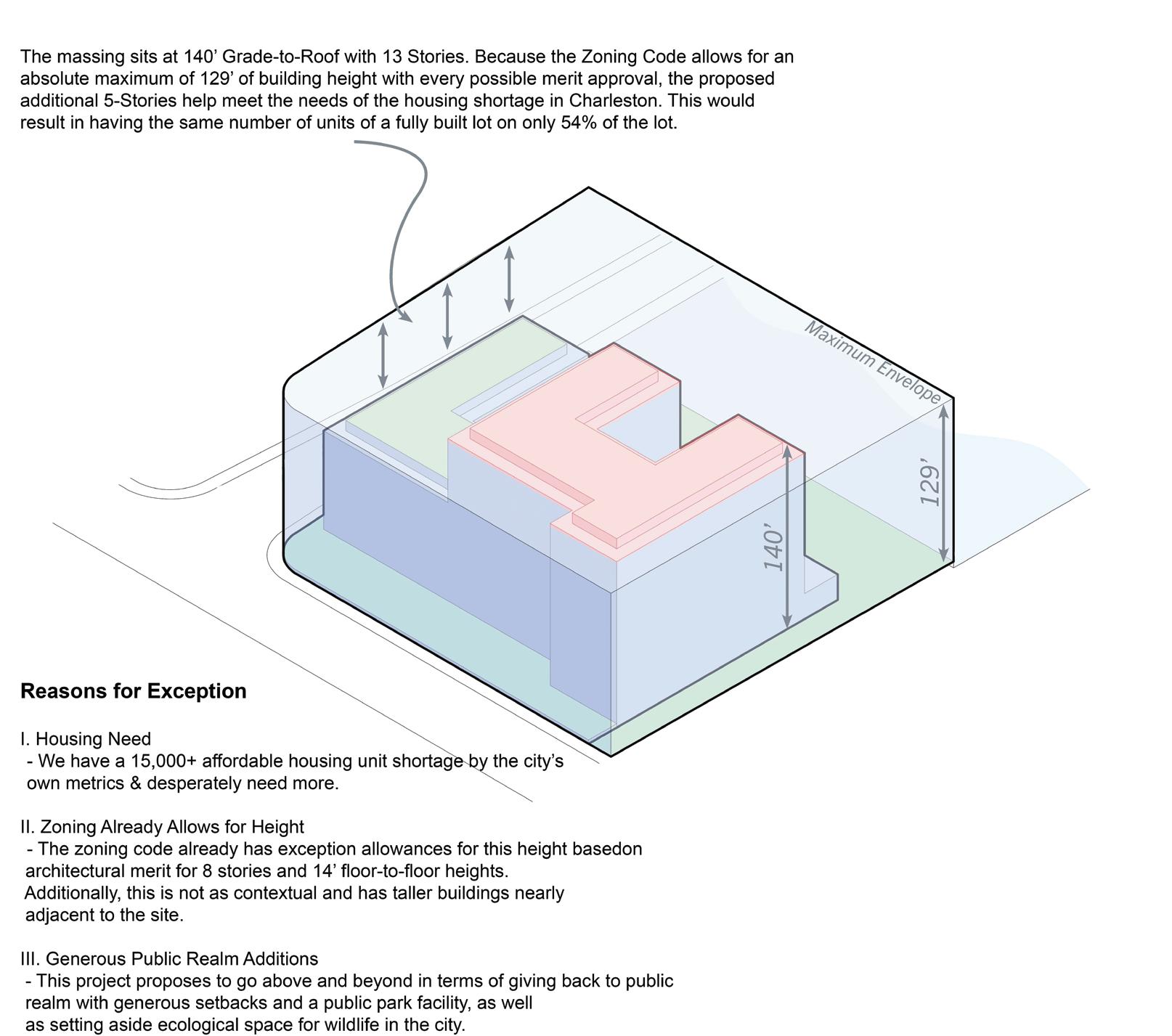

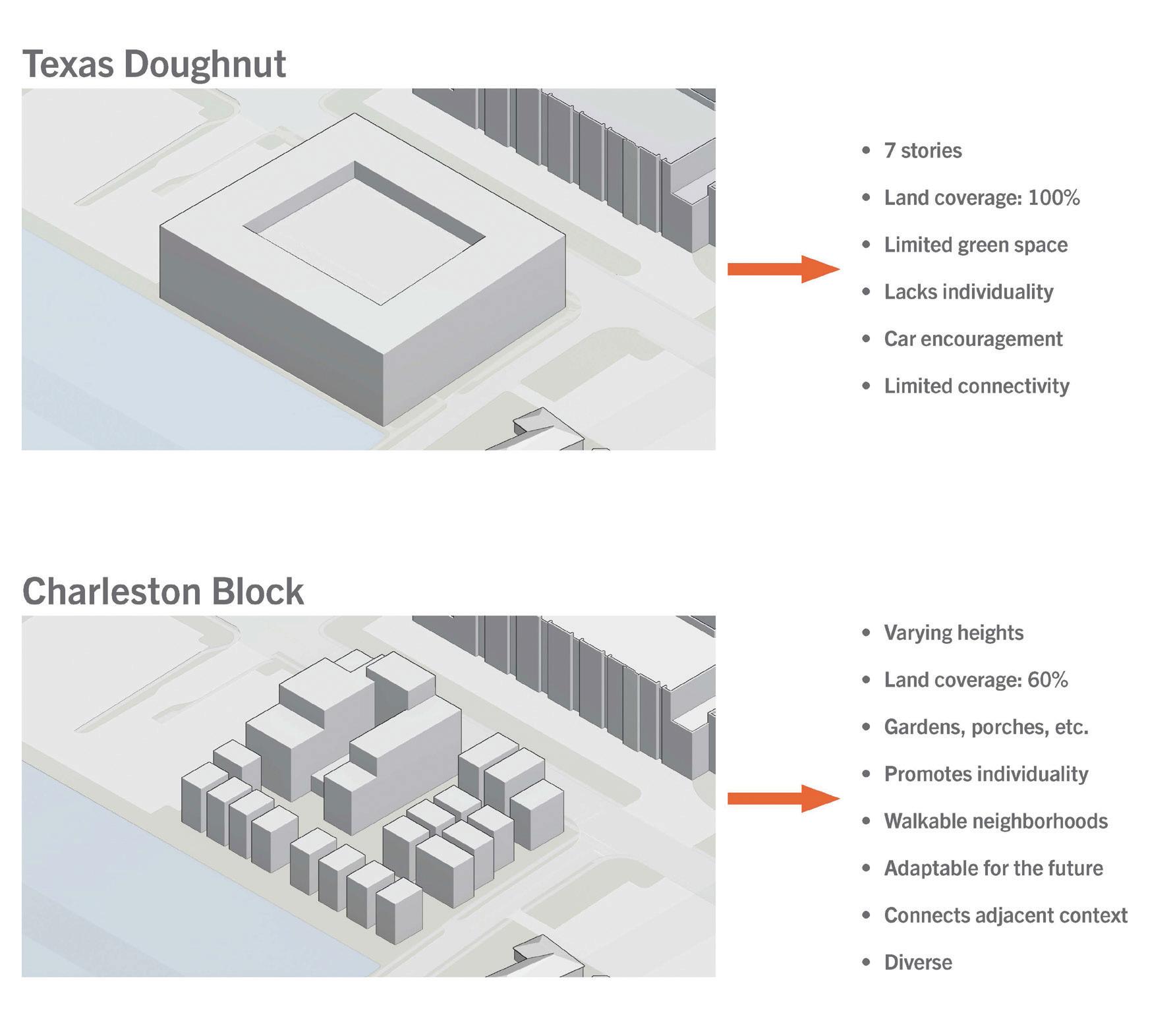

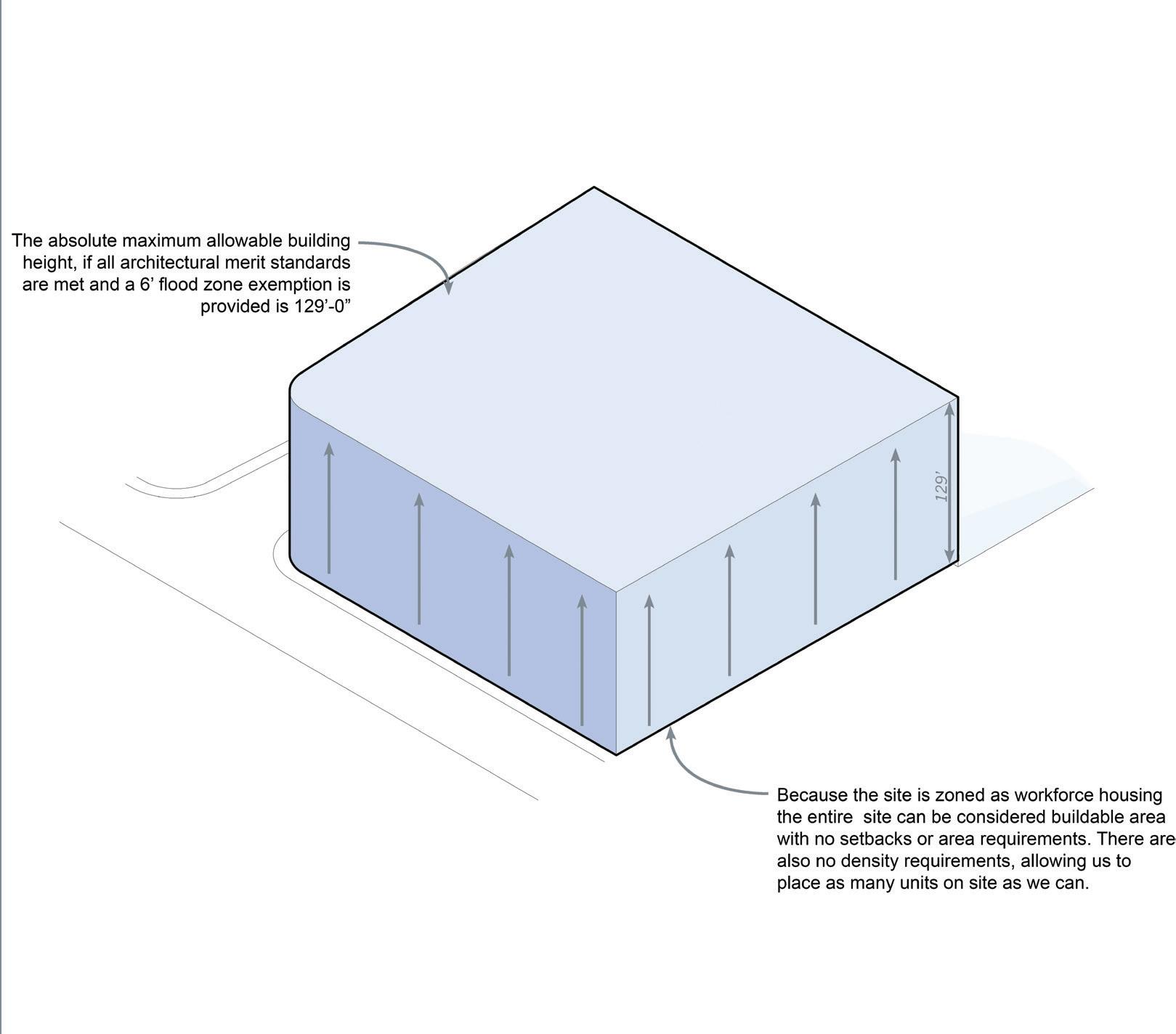

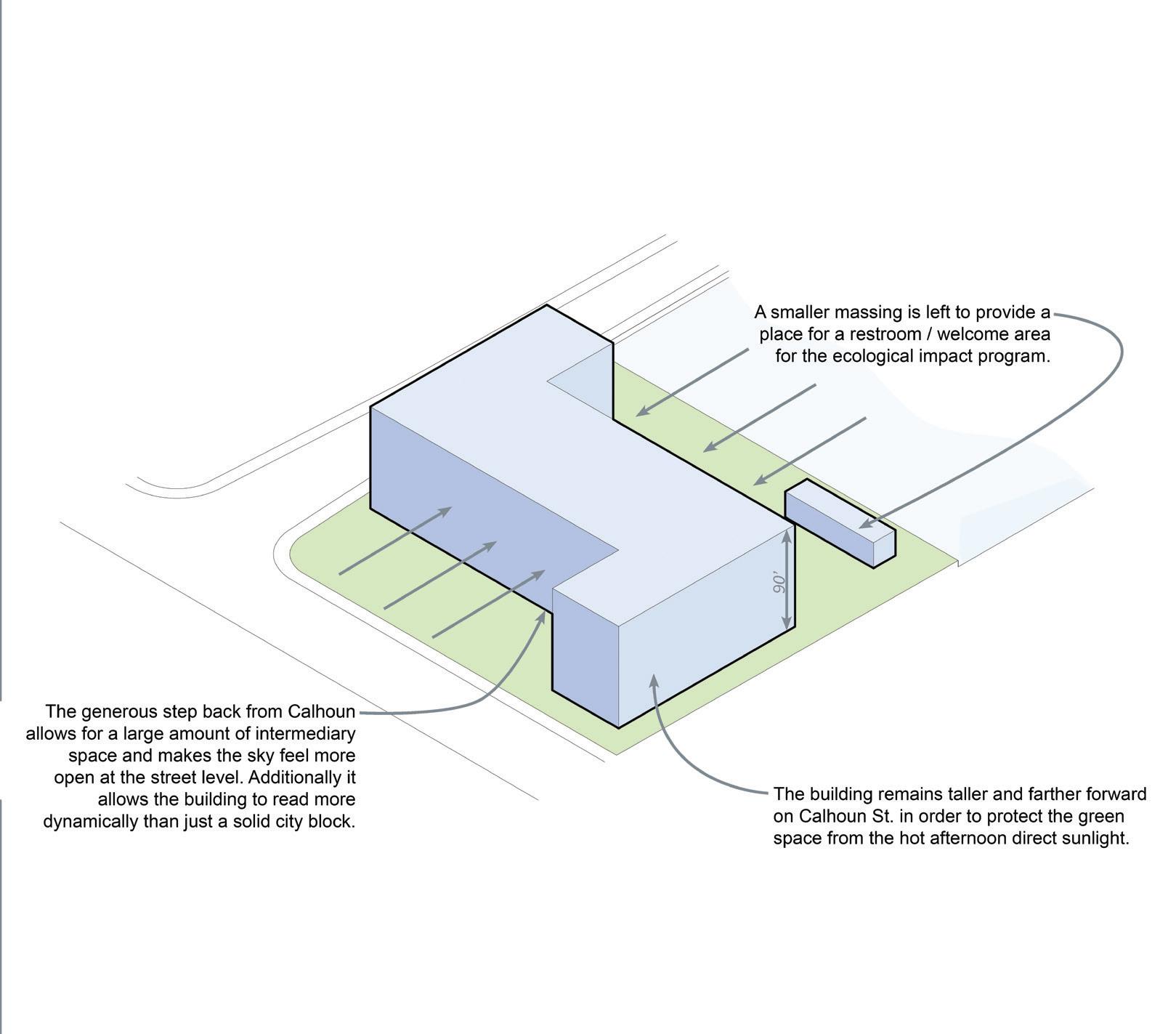

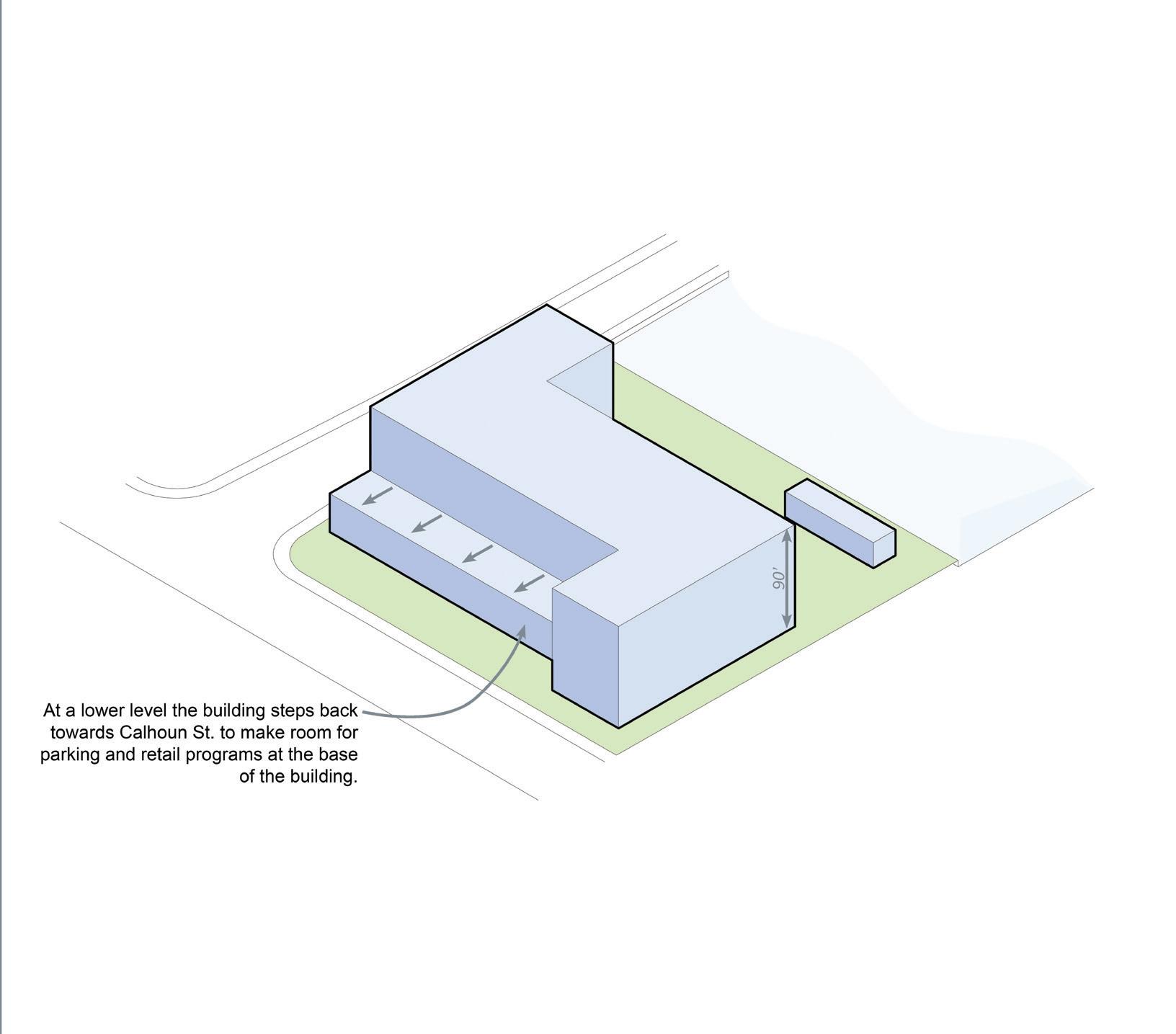

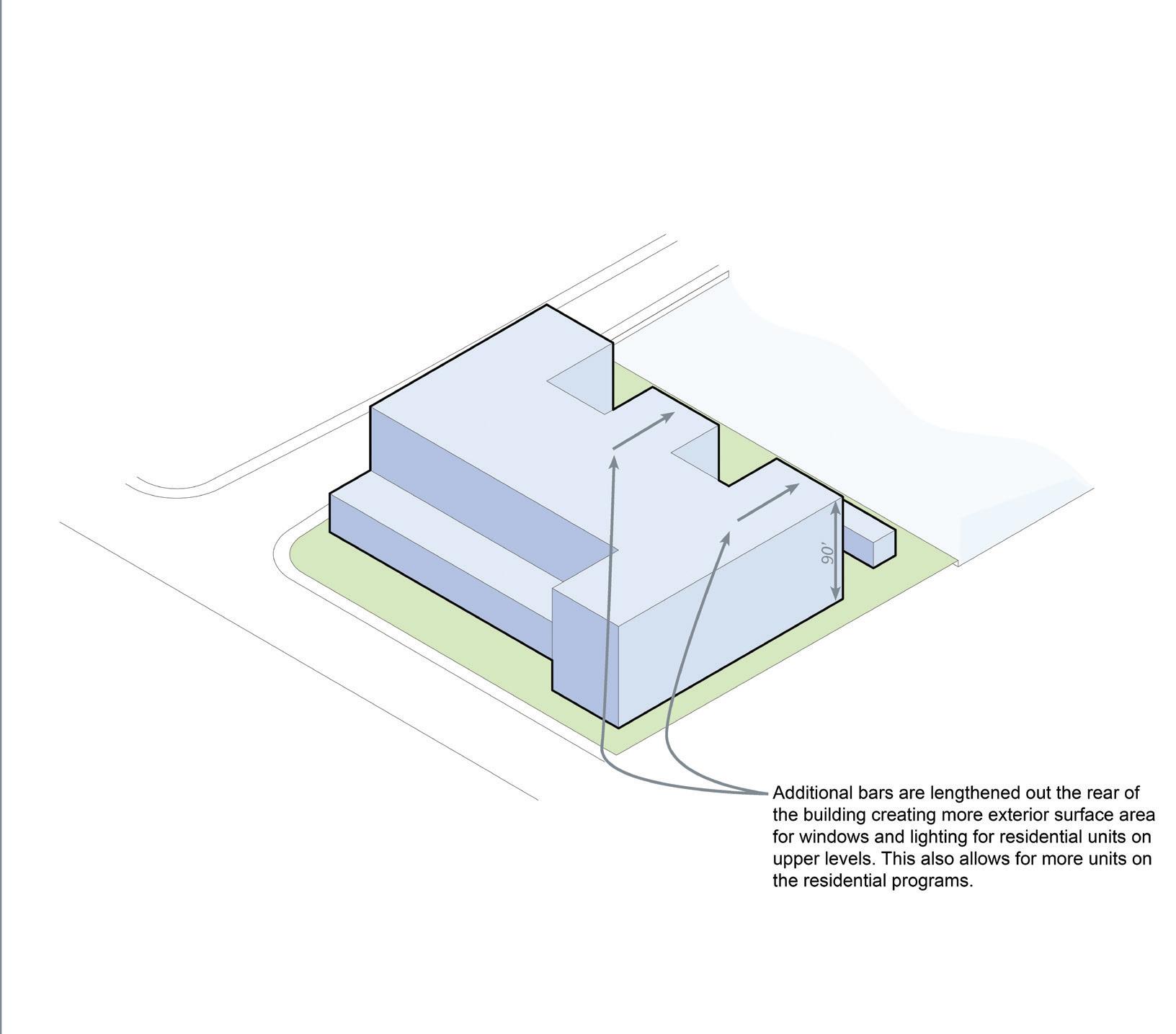

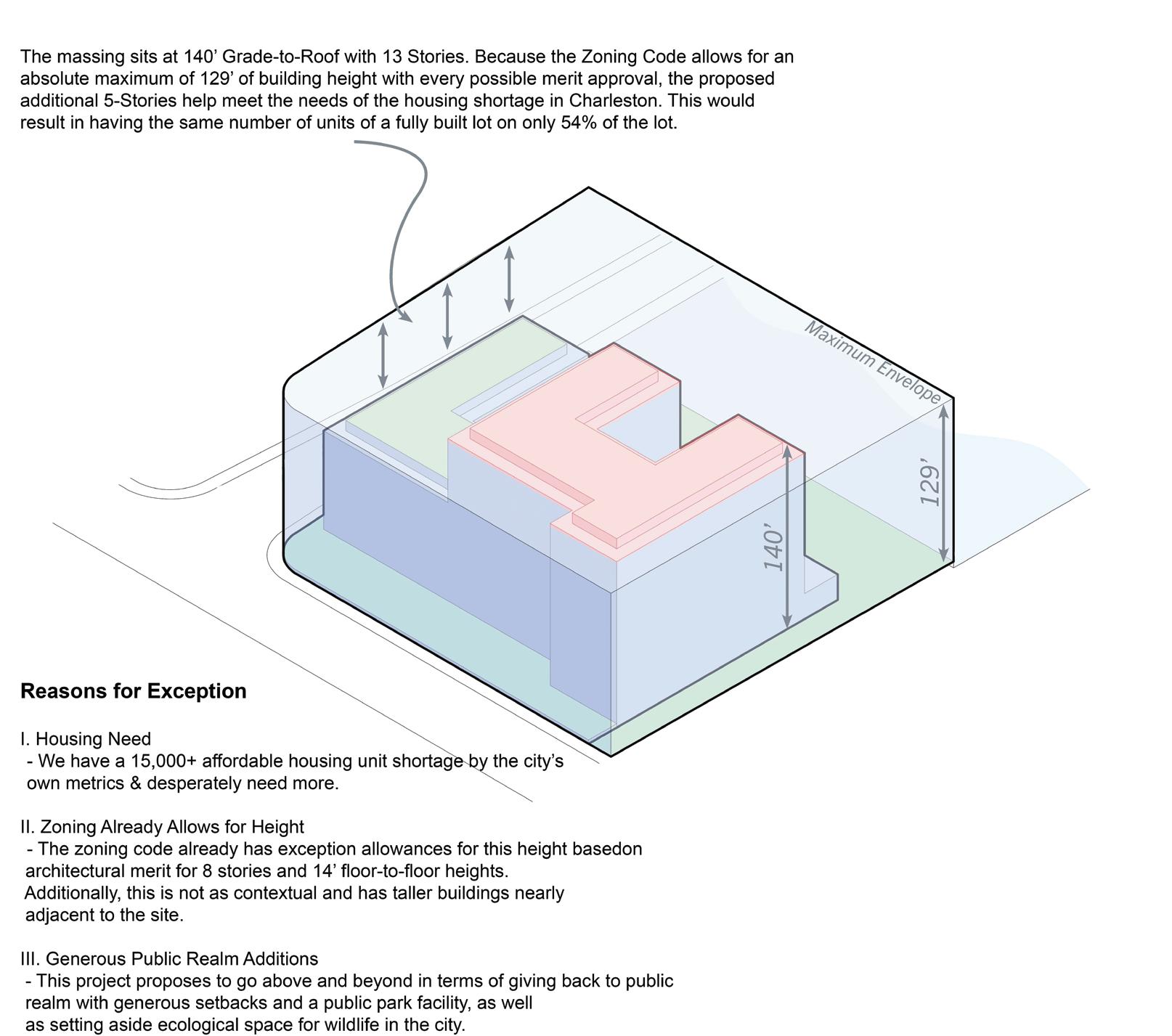

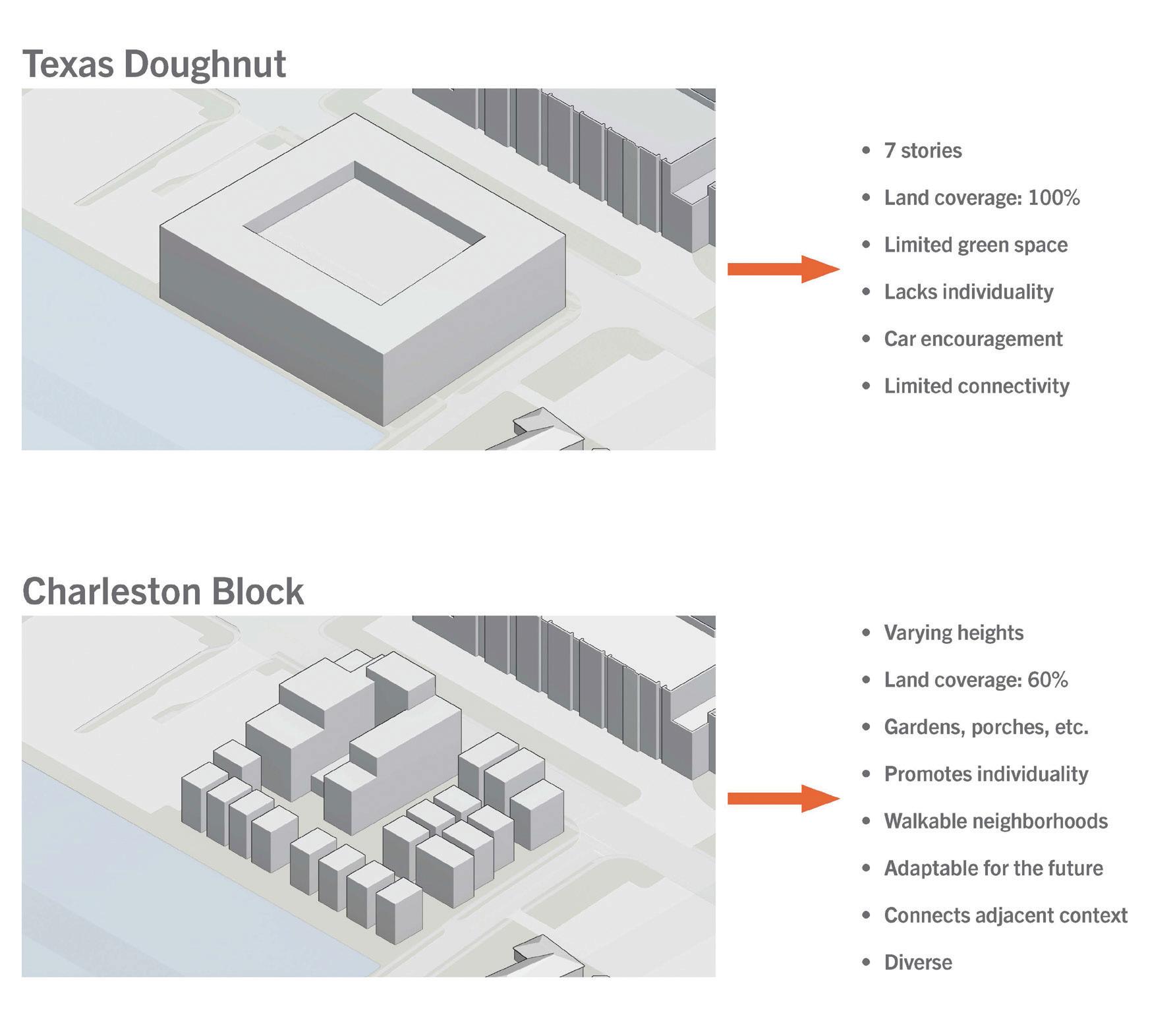

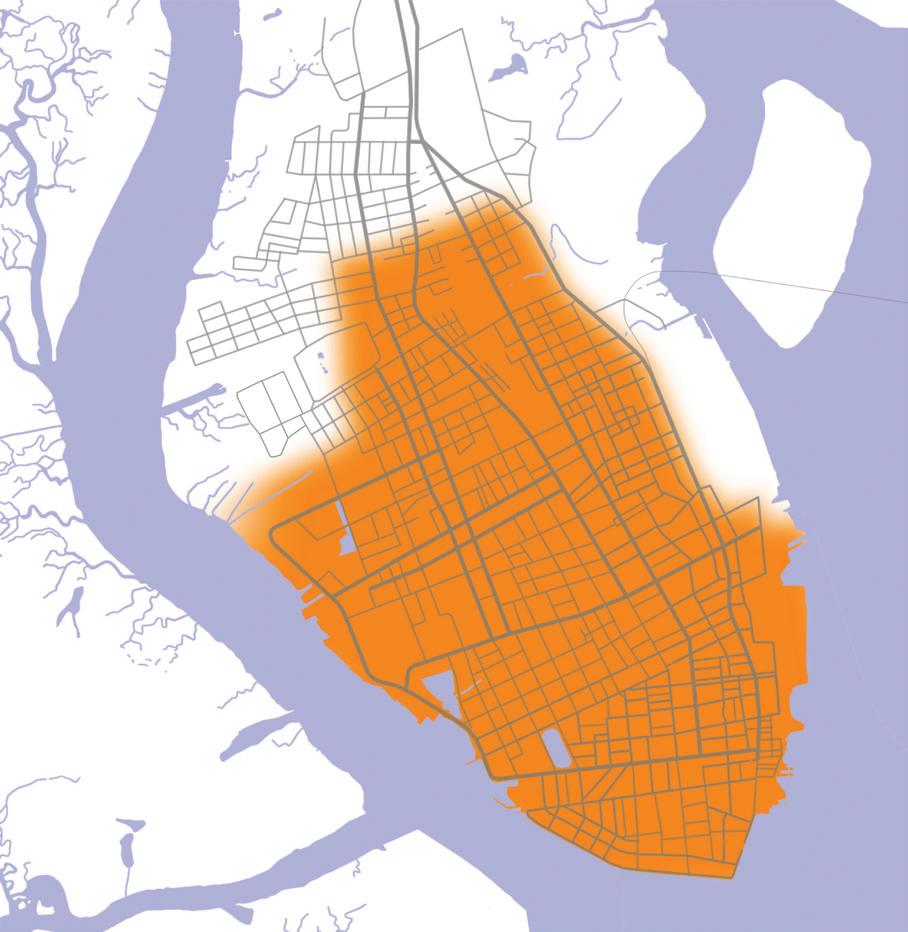

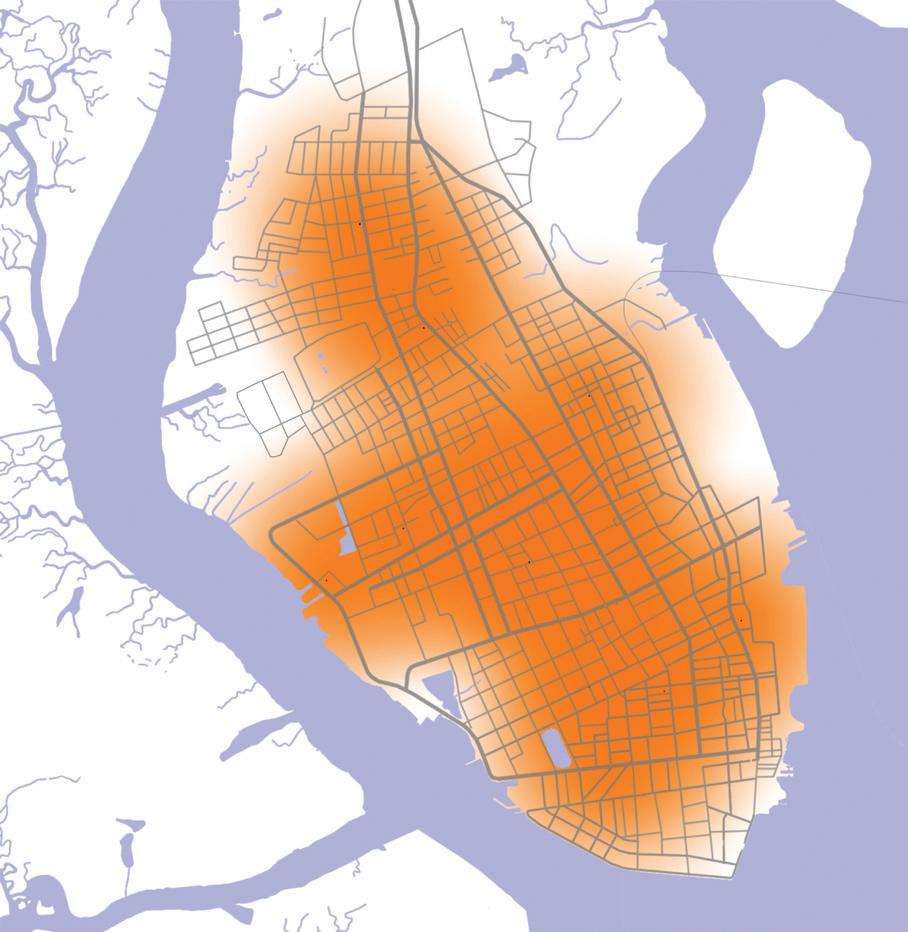

Consider that the current zoning for the City of Charleston requires a minimum of 274.5 square feet per car for the parking space and drive lane. This number does not include any additional vehicle or pedestrian circulation in the garage. The current downtown zoning requires 1 to 1.5 cars per residential unit in multifamily buildings. The required parking ratio changes to 1 space per 3 units for special needs housing, or 1 space per 4 units for affordable housing. Shifting from the current market rate housing requirements to those of special need or affordable housing would result in a minimum reduction of 183 to 343 square feet of parking per unit. This reduction in space for cars could be reallocated to create more open space, reduce the scale of the structure without reducing units, or provide additional housing units in buildings that are more in scale with the vertical rhythm of Charleston and not dictated by the dimensions of a garage (see figures 1 and 2).

There is also an environmental impact to building this space for a car. A parking space in a con-

crete structure, the typical means of construction for garages, is between 8 and 12 metric tons of embodied carbon in addition to the carbon footprint of the vehicle, 4.6 metric tons per year for the average passenger vehicle. During the COVID-19 shutdown in 2020, there was a 5.4% reduction in CO2 emissions in part because of the lack of vehicle-based commuting. There is also a significant financial implication to parking garages that directly impact the affordability of housing. A single parking space in a garage can cost between $35,000 and $75,000 to construct. The cost and environmental savings of reducing the prevalence of the vehicle is significant to our overall health.

While all the above impacts the overall environment, there are also things to consider related to our individual and collective health. Significant individual health benefits of physical activity are supported by the 15 Minute City model (see figures 3-5). The benefits of walking daily include reduced health risk, increased longevity, and improved mental health. Many residents of

28 CLEMSON SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE

FIGURE 1, PAGES 25–27: Housing massing study by Joel Rogers demonstrating how a site developed downtown could provide the same number of housing units on a site, occupying 54% of the site, if the parking is provided at 1 space per 4 units.

29

30

31

Charleston already do experience these benefits. Currently 12.2% of people on the peninsula walk to work, compared to 1.8% in Charleston County and 4.5 times better than the national average. 6.8% of people on the peninsula bike to work, compared to 0.8% in Charleston County and 13.5 times better than the national average. This type of commuting also connects people to their neighbors, allowing one to “live in the whole world” as Solnit describes. The city does not have to choose

walking and biking over driving. The model of the Dutch Woonerf, which translates to a living yard, creates an equity in the use of the street, allowing for a multiplicity of uses. Once a month, Charleston closes a section of King Street to come together for Second Sunday. This shift in the utilization of the street changes the way we see the urban fabric. It allows us to experience the historic scale and pace of the city that existed for more than two hundred years without the automobile.

32 CLEMSON SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE

FIGURE 2: Massing comparison by Autumn Hinson to maximize housing on a site that learns from the scale and fabric of the historic city utilizing 1 parking space per 4 units.

During the covid - 19 shutdown in 2020, there was a 5.4% reduction in CO2 emissions in part because of the lack of vehicle-based commuting.

33 HEALING ENVIRONMENTS | SUMMER 2023

Since the invention of the automobile, our cities have been built around its use and scale. The northern part of the peninsula has been significantly impacted by the car-based infrastructure of I-26 and the Crosstown cutting through neighborhoods and cutting off non-vehicle connectivity of the urban fabric. Charleston is now looking to develop Union Pier as an extension of the urban fabric and the plans for Laurel Island continue to develop. The current Union Pier Planned Unit Development proposal includes no minimum number of parking spaces beyond those required by federal regulation and articulates a focus on non-vehicle modalities. However, it does not have a cap and will rely on “automotive parking reasonably sufficient to accommodate market forces”.

Zoning standards, when developed in an inclusive way, represent the collective values of a community to inform the urban fabric. When the entire peninsula meets the criteria of the 15 Minute City of walking and biking, which promotes a healthier way of living, could we think about the future of Charleston in a way that learns from the value of the historic scale and proximity? If our urban fabric is walkable, can we become a more connected

and inclusive community? Can we think about a future that is not void of the car, but one where the pathways through the city promote a holistically sustainable community, connecting us to each other? Can we become a community that focuses on holistic health through our built environment?

REFERENCES:

“A Horseless Carriage” Charleston Evening Post, 9 July 1900, page 4

Carol Rasmussen. 2021. “Emission Reductions from Pandemic Had Unexpected Effects on Atmosphere.” NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL). November 9, 2021. https:// www.jpl.nasa.gov/news/emission-reductions-from-pandemic-had-unexpected-effects-on-atmosphere.

“Steuteville, Robert, and Andres Duany. 2021. “Defining the 15-Minute City.” CNU. February 8, 2021. https://www.cnu.org/ publicsquare/2021/02/08/defining-15-minute-city.

“Social Explorer.” n.d. Social Explorer. http:// socialexplorer.com.

Florida, Richard. 2019. “Bloomberg - Are You a Robot?” Www.bloomberg.com. January 22, 2019. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-01-22/how-americans-commuteto-work-in-maps.

34 CLEMSON SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE

35

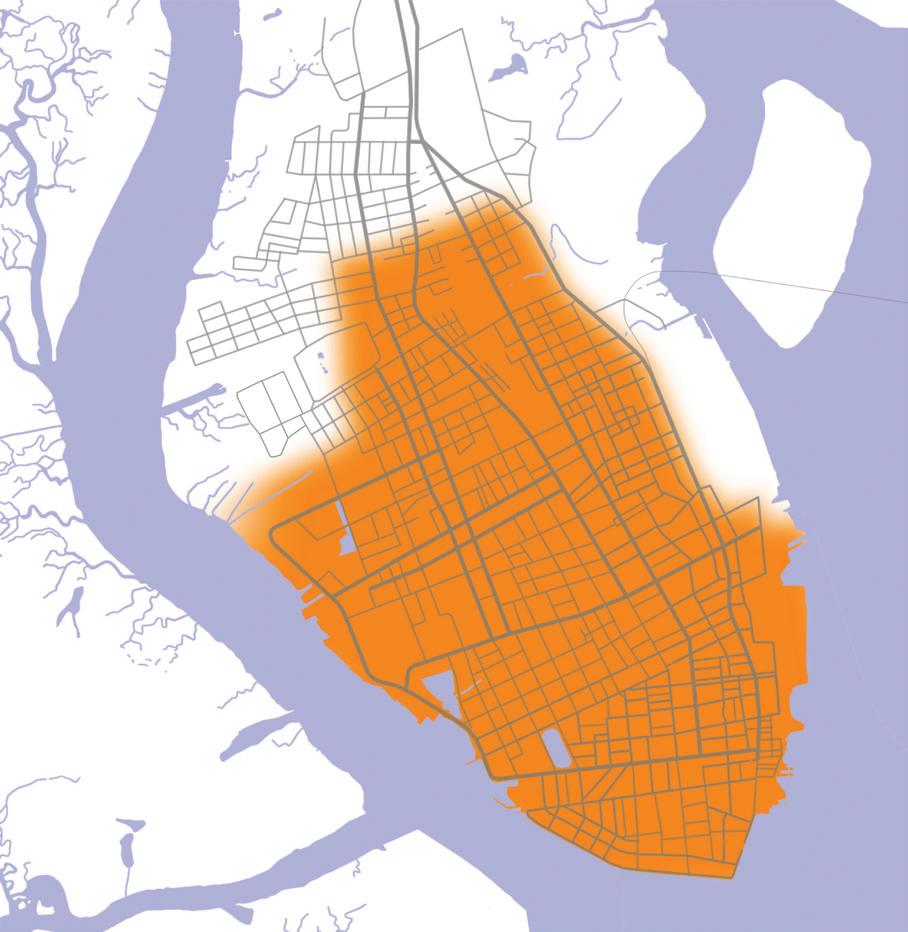

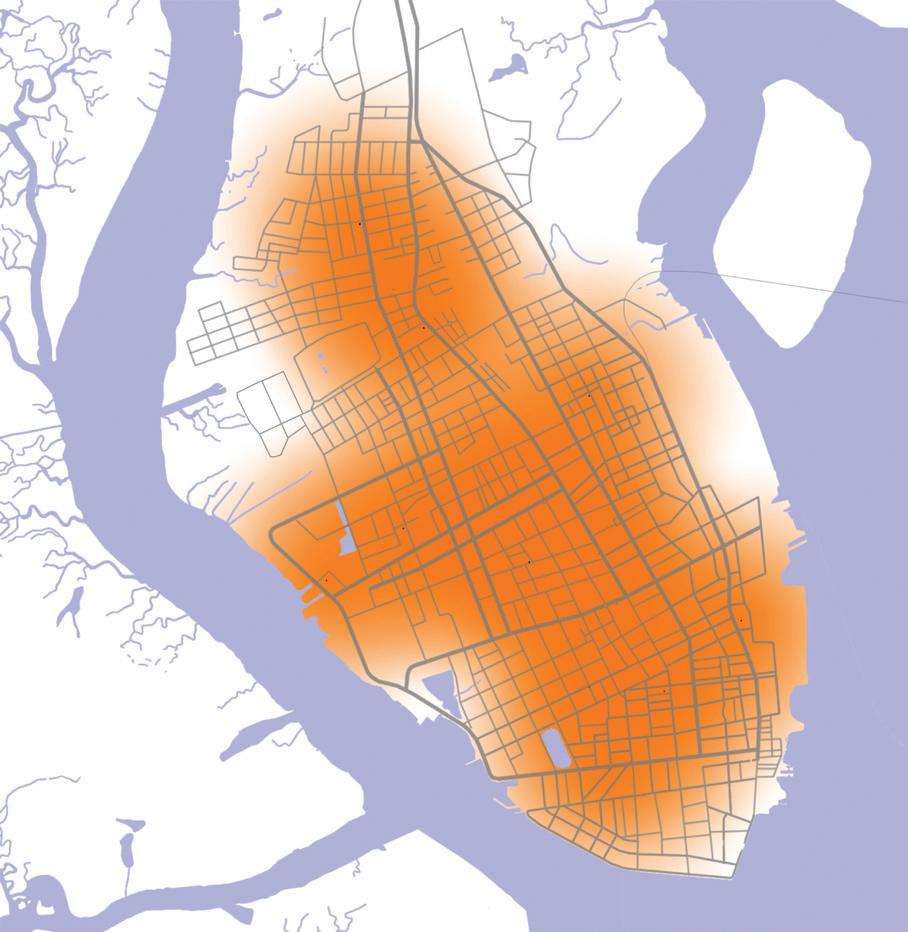

FIGURE 3 (LEFT): 15 minute bicycle shed for three grocery stores located at: (TOP) 10 Westedge Street, (MIDDLE) 290 East Bay Street and (BOTTOM) 1015 King Street in Charleston.

FIGURE 4 (RIGHT TOP): 15 minute walk shed for food comprising corner, small and large grocery stores.

FIGURE 5 (RIGHT BOTTOM : 15 minute walk shed for schools located in Charleston.

IT IS NOT FOR YOU…

CELEBRATING THE IMPACT OF HARVEY GANTT

A Collaborative Piece

36

SORRY,

37

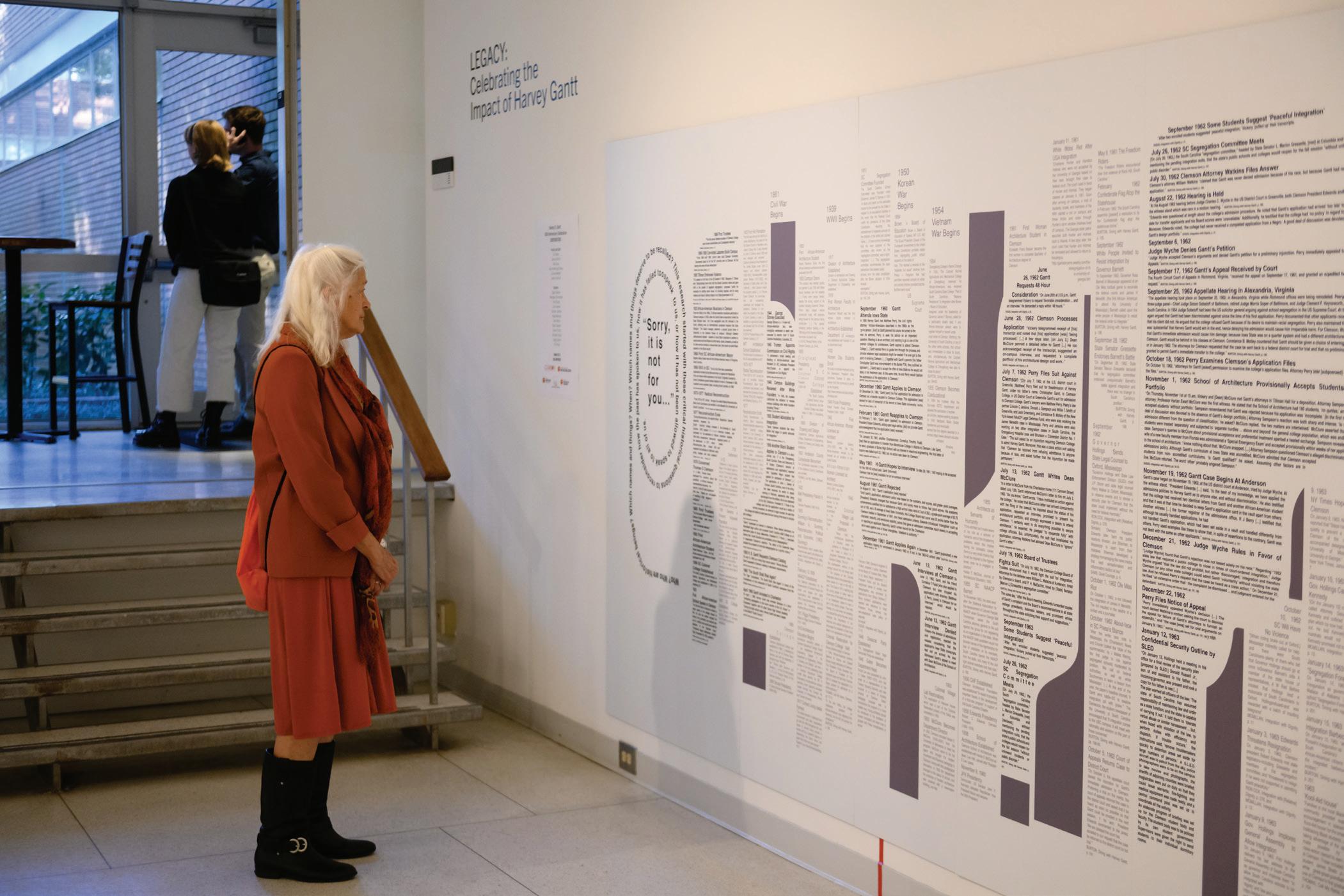

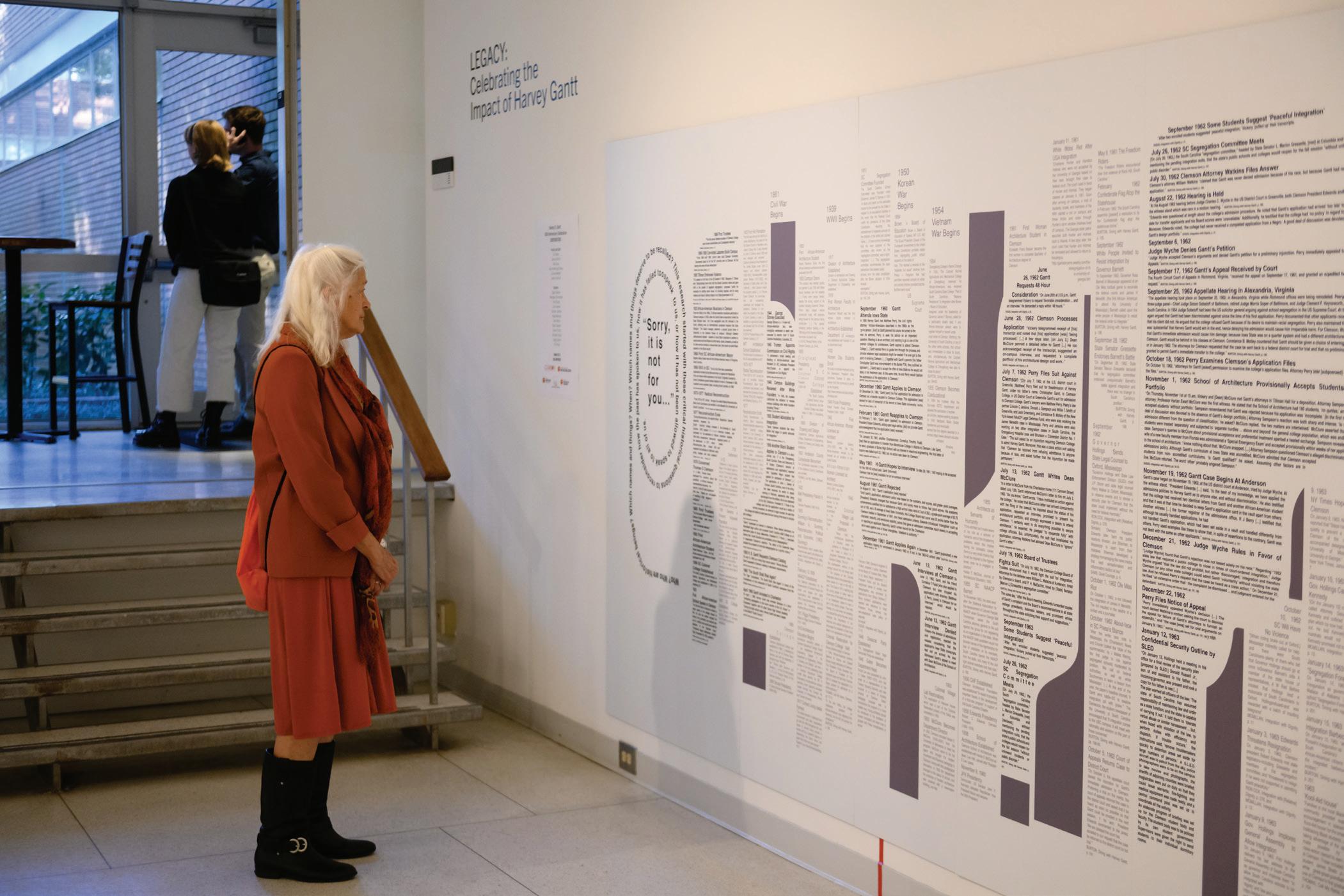

The show entitled, “Legacy: Celebrating the Impact of Harvey Gantt”, featured photographs by Cecil Williams, a juried art show, The Megaphone, a timeline created and designed by students and faculty, as well as many collages created by students in the School of Architecture.

Working on a timeless event

Revealing the timeline

Of many ripples hidden in the greater story,

We connected Ultimately, despite the obstacles

We were faced with when dealing with erasure. We connected

To every piece of dirt we had to sift through, uncovering years of our ancestors’ experiences

Along with their unresolved emotions and questions

For us all to feel together.

It felt like fueling the grand flame that is our soul

With numerous precious fires connected through space and time; Like truly tasting gratitude in water for the first time,

Remembering that this same water gave all of our ancestors life, Felt their prayers, connected to their cries, washed their dirt and their pains away,

Just as it does for us today, whenever that may be. Experiencing this event showed me that whoever we may be, Our stories are connected in profound ways so that once we find understanding in each other, we can find ways to build us up in spirit And as a society in this lovely land we share.

We dare to push for peace at Clemson, That is part of our art and our legacy.

Malik Sanders BA ARCHITECTURE, 2023

38 CLEMSON SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE

January 2023 marked the 60th anniversary of integration at Clemson University, and this date commemorated Harvey Gantt’s enrollment into the architecture program in 1963. To celebrate his legacy and the 60 years of integration at Clemson, the School of Architecture hosted a week-long event and collaborated with several organizations across campus to mark the date. The Lee Gallery hosted an exhibition designed to showcase creative work from students, faculty, staff, and alumni. The week-long event featured several speakers including Sekou Cooke, Julian Owens, Mario Gooden, Ray Huff, Danita Brown, Michael Allen, and Adrianna Spence.

The exhibit, Legacy: Celebrating the Impact of Harvey Gantt, sought to re-tell the story of the legacy surrounding Harvey Gantt’s life and the events that changed South Carolina, Clemson, and our community. The exhibit used

Mohammed Fakhry, M.ARCH 2021, explains why it is important to consider everyone when designing spaces and the importance of open communication to ensure designs are just and equitable.

39 HEALING ENVIRONMENTS | SUMMER 2023

Mohammed Fakhry, M.ARCH 2021, presents the piece entitled, “The Megaphone” at the gallery opening.

research conducted by Ufuk Ersoy, research and art created by current Clemson students and coordinated by Clarissa Mendez, and photographs taken by Cecil Williams as a backdrop.

The event was meaningful for many students and faculty. It attempted to create a Healing Environment where lost narratives could be retold, the seemingly natural state of things could be re-examined, and the school could become a space where the memories of social trauma and conflict could be overcome. Following, are a collection of reflections from students who organized and planned the event.

“Analyzing moments before, during, and after the integration of Clemson University became a process of growth through understanding. Critical topics in Clemson’s history were revisited to visualize the context and emphasize Harvey Gantt’s impact when he became the first African

40 CLEMSON SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE

As Clemson’s narrative of integration continues, so does inequality and racial discrimination.

Mr. Gantt’s legacy continues to show us the power of perseverance and determination.

41

American student to enroll at Clemson. Through research and analysis of available archives, the students and faculty learned about the impact the existing African American community at Clemson had on Mr. Gantt, making him feel welcome when others in and around Clemson’s campus did not. As Clemson’s narrative of integration continues, so does inequality and racial discrimination. Mr. Gantt’s legacy continues to show us the power of perseverance and determination. It continues to inspire the next generation of Clemson Architecture students to seek ways to use design to support a more equitable and just environment for everyone.”

Michael Urueta

BA ARCHITECTURE, 2021 MASTER OF ARCHITECTURE, 2023

“When we began on this project, there were many unknowns and uncertainties. We pondered over our goals

42 CLEMSON SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE

Ufuk Ersoy discusses the challenges in uncovering untold stories and narratives during the research for the exhibit.

and the messages we aimed to convey. Despite having many facts and supporters, we struggled to find the right approach to narrate the story. How could we effectively portray the journey of desegregation? How could we do justice to Harvey Gantt’s story and the history of Clemson University? Our objective was to tell a story and not exclude anyone. However, we grappled with the challenge of representing the voices that have come and gone. How could we ensure that the future voices are also heard? In the end, we found ourselves left with more questions than answers. It was for these very reasons that we decided to provide the audience a platform—a space where they could be heard and noticed. When you entered the gallery, you faced a wall with questions; Who are you? Why Clemson? What counts as injustice? How do you deal with diversity? Giving a voice to the unheard.”

Edgar Alatorre MASTER OF ARCHITECTURE, 2023

43 HEALING ENVIRONMENTS | SUMMER 2023

A visitor to the gallery reads the timeline, “Sorry, it is not for you...”, which presented research conducted by faculty and students.

Students, alumni, faculty, emeritus faculty, staff, and others visit the gallery for the opening of “Legacy: Celebrating the Impact of Harvey Gantt.”

Meeting Cecil Williams was a highlight of the gallery opening week for me. I greatly enjoyed hearing about how he came to photography as a child and how integral photography has been as an artistic medium in his life. Photographs transcend time and allow us to see events as they are taking place. Perhaps this is why Cecil’s photography is so moving — Cecil’s work strived to capture important moments in history that may not have been recorded if it were not for his camera. These moments include milestones in the fight for Civil Rights in the south, an important message at the time of their capture, and even more so now. Within his collection of photographs, I see reflected the goals of cNOMAS’ advocacy within the School of Architecture and a hope for a future Clemson that owns its true past in order to heal and move forward.”

Seth Moore BA ARCHITECTURE, 2023

Students also had the opportunity to work with other students and faculty creating meaningful experiences outside the classroom. Several students reflected on this aspect of the event.

“As I reflect on the exhibition and efforts from the summer of 2022 and onward, I am reminded of those who sat on the periphery of Clemson University’s desegregation and Harvey Gantt’s legacy. Much of our research before the event involved untold narratives in conjunction with the University’s history and inception. So many others, unnamed, were involved. I emphasize their presence because the event felt just like that. There was a sense of acknowledgment for those who unknowingly contributed in the past and those who are contributing today. What I most appreciated about this process was the diversity of those who put forth much effort into making the event such a success. There were unifying moments where race, age, gender, and classification did not matter, and everyone’s input was validated. Harvey Gantt’s legacy was not only for the advancement of non-white people but for

45 HEALING ENVIRONMENTS | SUMMER 2023

Cecil Williams and undergraduate architecture student, Seth Moore, discuss the work presented in the gallery.

everyone who was genuinely involved. There were moments of learning, sharing, and questioning. It was a true exchange.”

Gregg Ussery BA ARCHITECTURE, 2020 MASTER OF ARCHITECTURE 2023

“Having the opportunity to collaborate with various faculty members as well as classmates on this project proved to be an extremely fulfilling experience. We began the planning and research efforts for the celebration in the summer of 2022, where each of us were able to bring our own unique skills and interests to the table. This planning then continued through the fall semester with the development of the exhibit’s timeline and various collages and graphics. By dividing up specific topics and areas of

46 CLEMSON SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE

Visitors view the artwork in the Lee Gallery during the opening. Many alumni from the art and architecture programs were in attendance. In this photo, you can see one of the guests of honor, Cecil Williams.

research among the group, we were able to develop an extremely in-depth and telling timeline of Gantt’s life and legacy, both at Clemson and beyond. This entire project was truly a team effort, and I believe that is what made the entire celebration so successful.”

Allie Glavey BA ARCHITECTURE, 2020 MASTER OF ARCHITECTURE, 2023

While the 60th anniversary celebration has come to an end, the school’s engagement, support, and commitment to creating an equitable school for all students continues. We want the school and University to be a Healing Environment where we can recover and heal from the traumas of our past. The next chapter of this project is the planning and construction of a statue honoring Harvey Gantt on the Clemson campus. Our school will continue to advocate for spaces that heal our bodies and minds through the environment that surrounds us.

“Looking forward, our hope for the Harvey Gantt statue is that through its design, engagement with the community, and construction it speaks on behalf of what Harvey Gantt stood and fought for, which was diversity and inclusion. A major concept in the design showcases the idea of foundation, symbolizing that what Harvey Gantt achieved started generations before and will continue generations after him. Our hope for the statue is that it encourages us as future leaders to continue to push for

a more diverse and inclusive space, and it’s something that we must do together. Harvey Gantt inspired a place of inclusion and it’s our job to see it through.”

Sheldon Johnson

BA ARCHITECTURE, 2024

This project was a collaboration between many individuals. The primary participants and contributors were:

EDITED BY:

Sallie Hambright-Belue

FACULTY AND STAFF:

Bill Bates

Clarissa Mendez

Denise Detrich

Janelle Schmidt

Sallie Hambright-Belue

Ufuk Ersoy

STUDENTS:

Allie Glavey

Angie Mendoza

Connor Smith

Edgar Alatorre

Gregg Ussery

Jalyn Haynes

Mahogany Christopher

Malik Sanders

Michael Urueta

Nicole Rebolledo

RJ Wilson

Seth Moore

Sheldon Johnson

47 HEALING ENVIRONMENTS | SUMMER 2023

48 CLEMSON SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE

NARROW MARGINS AN ESSAY ON A GENOVESE VILLA

Julie Wilkerson, senior lecturer, pir, in conversation with George Schafer, senior lecturer, pir

To frame Clemson’s Daniel center for Building Research and Urban Studies – or “The Villa,” as a ‘Healing Environment’ one must include the Villa itself as a tangible building, a physical thing with surfaces and volumes, narrow margins of refuge, wide centers of work, edges, enfilade, and textures.

All of it, when taken together offers a foreign home as refuge to generations of Clemson students and faculty. The Villa is strong, struggling and surviving in a contemporary society, proudly

wearing the Clemson Architecture Foundation’s brass plaque on her 14 Via Piaggio façade. She gives over and over, as if her reservoir were bottomless. Just her age alone, reminds us of the necessities that we take for granted in the 21st century, like abundant energy, hot water, and filtered air. This 19th century building challenges our adaptability as human beings, which is to say we metabolize patience and a slower lifestyle as healing for the scarring created by an accelerated American work ethic.

Students and faculty who live and

49 HEALING ENVIRONMENTS | SUMMER 2023

50 CLEMSON SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE

learn in the Villa for a semester leave the 21st century behind and are swept into a 19th century building left quite bare on comfort and rooms of negotiable function; this is a bivouac, a protected compound, an American outpost. A welcomed transition from our American, hermetically sealed interiors where forced and filtered air is common, we learn to breathe the outdoor air while indoors, reconnecting us to a sustainable and healthy way of absorbing the air we breathe. Italian interiors, with the absence of filtered air, allows the dust to grow like skin, a reminder of time passing and the pre-modern conditions that we may have forgotten. Joseph Brodsky reflecting on dust in a Venetian Palazzo, said, “Every surface craves dust, for dust is the flesh of time…it will seep into the objects themselves, fuse with them, and in the end replace them.”

At the center of this marble container, work and home are collapsed into one thing, one place, a tangible lesson and model that the Villa has practiced for 50 years. At the Villa’s perimeter, in its margins are found its second place, the gardens, loggia, and terraces offering space for reflection, a modicum of solitude, and healing from the dynamic center of performance, criticism, co-living, and work. The marginal

spaces are the replacement for ‘going home’, a place of healing, rest, and reflection. The margins offer stasis, a kind of individual self-healing, apart from the dynamic center of work. On these second places Michael Benedikt writes, “Margins imply closeness to limits, outside edges, and boundaries along which what is ‘inside’ becomes ‘outside’…a space for commentary and reflection, whispers, and healing. Centers, in complement, imply the notions of depth and heart, the place of concentrated meaning, embeddedness, depth, and gravity.”

In this sense the Villa can be said to be a metaphor of this marginal-central opposition. While marginal and central spaces have connotations of “not important” and “important” spaces respectively, the Villa proves otherwise, offering a hierarchy reversal between centers and margins and balancing their mutually dependent use. Villa margins merge interaction with nature at a distance or close at hand, providing recovery and healing from the stress found at the Villa center. We are made stronger from the work done at the center of the Villa, but healing is found in the margins.

Thick exterior walls have a natural advantage in establishing marginal zones. Here, the Villa wall is an

51 HEALING ENVIRONMENTS | SUMMER 2023

we learn to breathe the outdoor air while indoors, reconnecting us to a sustainable and healthy way of absorbing the air we breathe.

invitation that invites passage, a threshold that creates preparation unlike the thin-walled buildings of today. One must engage with this 19th century wall in an almost theatrical way, beginning with the approach to a window that acts like a door fitted with vertical brass mechanical hardware that requires a forceful up and down motion. There is an intentional physical engagement between the wall and the body, the hand, and the mechanical equipment. The Villa’s mechanical extras invite interaction; window and door

hardware, the swinging shutters, accessory metal props for adjusting window shutters, clips and ready to barricade solid steel bars hanging at each shutter, deep sills for resting, and spatial accommodations proliferate for gurgling radiators. These past technologies found at the wall openings have their own way of presenting and revealing themselves as well as the world in which they operate. They identify with a technological past that today has a presence of endurance and reveals the world to us from which it came, a

52 CLEMSON SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE

mechanical world that becomes opaque in its use and engagement with the human body. Unlike new technology that enables its use to be almost transparent, effortless, and under erasure, the Villa preserves and protects these past technologies that will continue to connect us moderns to a world that is opaque and contemplative in its being and use.

These elements particular to the Villa wall are reminders that relate to our healing thematic and to quote David Franco, “…reactivate

our lost narratives as a society…” reconnecting student and faculty alike to a time, a 19th century time when the wall was thickened, valorized, functional, and put to use on a daily basis.

Passage through the window-door artifacts into the Villa loggia and garden where one would take air, sun, and extraordinary views, are luxury moments taken to release the center and to luxuriate in the extended margins where nature is fused with recovery. Here, there is a reciprocal relationship between

53 HEALING ENVIRONMENTS | SUMMER 2023

54 CLEMSON SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE

centers and margins, between work and recovery, between co-living, and isolation.

The loggia, like a camera lens, frames a distant horizon view where the Mediterranean meets the sky, across the Castelletto neighborhood through the medieval city, across the port and into the sea. One feels the weight of the sea and the lightness of the sky, a paradoxical view that prompts one to be still, seated, and healed within the small surround of the loggia while taking in the line between the sea and sky. The horizon offers a view to be seen from a distance, the imaginary geography of a line, one that changes based on the humidity in the air and has the power to settle all fears. A place of the imagination, a state of mind, the Ligurian horizon, a line seared into decades of longing and memories. This prospect reminds us that Leon Battista Alberti mused, “when viewed from afar, the sea has greater charm, because it inspires longing.”

The Villa garden is a rectangle cut from the sky of the Castelletto neighborhood, an enclosure of a cultivated landscape that provides a sense of well-being, rescue, and solace. The word garden comes from the Indo-European root gherd meaning enclosure. The word paradise comes from the old

Persian pairidieza meaning enclosure. An enclosed paradise with fruit trees bordered by a green hedge, a grotto that is home to a turtle and several fish, and a near view where the salone door meets the garden path, the Villa Garden is escape. It is a place to be lived in, to inhabit, not to be seen from a distance but to be seen from within. Barbara Solomon said, “In an ordered landscape bewilderment subsides.” To emerge from the Villa garden is to emerge refreshed, readied, and healed from the green margin into the masonry centers of work and production.

The Villa is a home away from home, a welcomed refuge after long travel, a safe place to be cared for, and a marble think tank where architectural narratives become buildings, sections, models, and drawings. While we rest, heal, and absorb travel memories, the Villa functions almost as an autonomous object. By supporting and delivering our basic domestic needs, the Villa cultivates the ‘Architect as Scholar’ like being in a seminary of higher learning. Coupled with an Italian discipline that balances work and leisure to the benefit of one’s health, balance is achieved in the interconnected marginal and central spaces of the Villa, mutually dependent and inherent in the legacy of Italian Villa Life.

55 HEALING ENVIRONMENTS | SUMMER 2023

AWARDS

CAAH AWARDS

FACULTY AWARDS

Dean’s Award for Excellence in Research

Anjali Joseph

Dean’s Outstanding Lecturer Award

Lara Browning

STAFF AWARDS

Dean’s Team Player Award

Miriam Rose

Dean’s Innovation Award

Regina Foster

STUDENT AWARDS

Dre Martin Service Award

Haley Carpenter

EXTERNAL AWARDS

SARA|NY DESIGN AWARD

Design Awards of Honor

Mia Walker And Lucas Schindlar

Andre Daniels, Cierra Davies

Design Awards of Merit

Olivia Wideman

CELA (COUNCIL FOR EDUCATORS IN LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE) AWARDS

Faculty Award for Excellence in Service Learning

Lara Browning

Faculty Award for Excellence in Teaching – Senior Level

Paul Russell

AIA Charleston Award for Service

Clemson Design Center Charleston

LAF (LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE FOUNDATION) AWARDS

LandDesign Equity, Diversity and Inclusion Scholarship

Melissa Morales

Landscape Forms Diversity, Equity and Inclusion Scholarship

Tairiq Mansfield

SoA Awards

J.E.D.I. Undergraduate Award

Malik Sanders

J.E.D.I. Graduate Award

Edgar Alatorre, Allie Glavey and Gregg Ussery

56 CLEMSON SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE

The Architectural Research Center

Consortium. The King Medal for Excellence in Architectural + Environmental Research

Stacy Scott

Clemson Architectural Foundation Student Prize

Angie Mendoza

Landscape Architecture

COLLEGE AWARDS

University Undergraduate

Olmsted Scholar

Emma Strong

UNDERGRADUATE PROGRAM AWARDS

Design Communication Award

Cara Henderson and Ginger White

The Don Collins Founders Award

Jack Faulconer and Shelbie Hyland

The Faculty Book Undergraduate Award

Haylee McManus and John Angeles

Spirit of the Studio Award

Jamari Evans and Evan Libensperger

Leadership and Service Award

Haley Carpenter

Design Coach and Mentor Award

Holden McCullough and Bryce Harris

GRADUATE PROGRAM AWARDS

Promising Scholar Award

Libby Pruden

Design Communication Award

Frances Sledge

Spirit of the Studio Award

Jordan Livingston

Leadership and Service Award

Derek Bussey

Outstanding Graduate Assistant Award

Molly Foote and Meredith Bendl

SCASLA Awards

American Society of Landscape Architects

Undergraduate Honor Award

Haylee McManus and Mason Malphrus

American Society of Landscape Architects

Graduate Honor Award

Meredith Bendl

American Society of Landscape Architects

Undergraduate Merit Award

Kinzer Hurt and Emma Strong

57 HEALING ENVIRONMENTS | SUMMER 2023

American Society of Landscape Architects

Graduate Merit Award

April Riehm

SCASLA Award

Melissa Morales

SIGMA LAMBDA ALPHA

The Honor Society of Sigma Lambda

Alpha, Inc. National Scholarship

Melissa Morales

The Honor Society of Sigma Lambda

Alpha, Inc.

Peyton Stokes

Evan James Libensperger

April Riehm

Emma Strong

Haylee McManus

Melissa Morales

Architecture

Second Year Faculty Award

Vivian Nguyen

Rudolph E. Lee Award

Katherine Harland

A.I.A. South Carolina Chapter Award

Abby Anderson

Peter R. Lee and Kenneth J. Russo Design Award

Andrew Fulmer

Undergraduate Prize in Design

First Place: Caius Bartlett

Runner-Up:

Madelyn Ault and Joel Rogers

Honorable Mention:

Jared Ruskin and Rustin Seyle

Honorable Mention:

Ellie Rhinehart, Griffin Naddy and Melissa Ricaurte Munoz

Honorable Mention:

Andrew Fulmer and Dave Patel

4th Year Faculty Design Award

Carter Bertram and AJ Jackson

Sam Garland and Kayla Pyles

Harlan McClure Award

Jerome Simiyon and Andrew Schick

Mickel Travel Award

Andrew Mark Schick

58 CLEMSON SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE

Martin David Award

Audrey O’Brien and Kelsey Piotrowski

The Edward Allen Student Award

Sean LaRochelle

AIA Medal of Academic Excellence

Michael Urueta

Alpha Rho Chi Medal

Seth Moore

Clemson Design Center Charleston

CACC

The Ray Huff Award for Excellence in Undergraduate Scholarship

Mahogany Christopher—Fall ’22

Spencer Dean—Spring ’23

Sheldon Johnson—Spring ’23

The Robert Miller Award for Excellence in Graduate Scholarship

Nick Oxendale—Fall ’22

Mia Walker—Spring ’23

MRUD

Excellence in Resilient Design and Leadership

Kim Morganello

COLOPHON

The design of the publication stems from the idea of healing as a process rather than an endpoint.

The overarching idea is that of a world trying to get to something "normal" after a disruption or interruption.

It's also driven by the question of "What if there’s a whole lot of amazing that stands to be lost if Normal returns?" (Sophia Rosenbaum, Dear Normal: Were you really that great in the first place?)

This text, these words, are trying to get in place, struggling to be in the role they should be in. They're trying to get back to normal. But do they?

Can they?

Should they?

TYPE

The typefaces used in this publication are:

Tiempos, by Kris Sowersby and Trade Gothic

Next, by Akira Kobayashi, a 2008 update of Jackson Burke's font from 1948.

DESIGN

Daniel Lievens teaches design, and he designs and develops digital and printed materials –websites, books, posters, icons, identities – for cultural, nonprofit, and political clients. rdaniel.net

PRINTING

Printed and bound at Midway Press, Dallas, Texas.