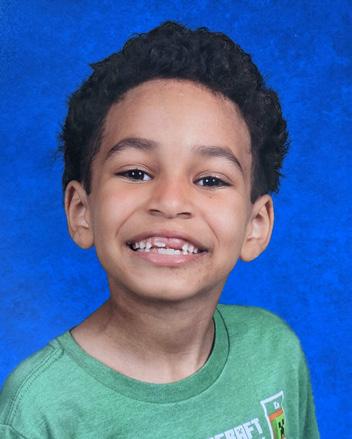

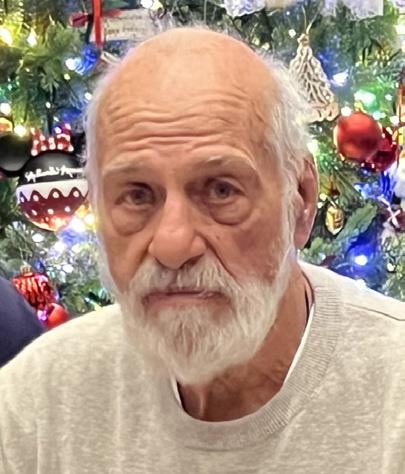

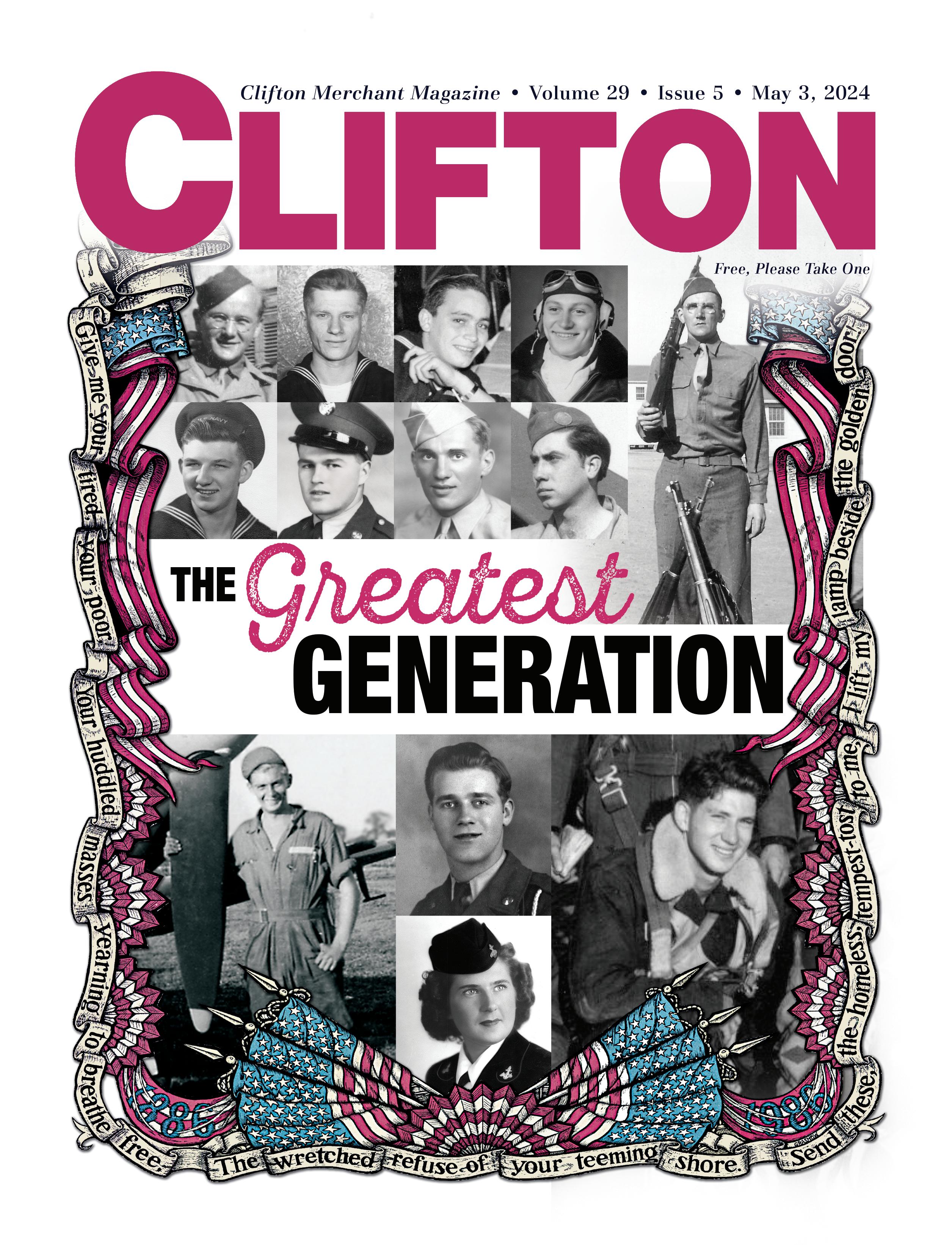

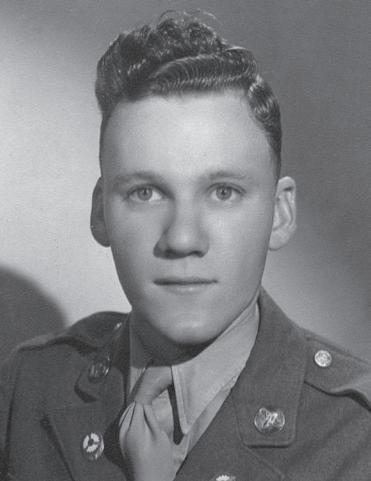

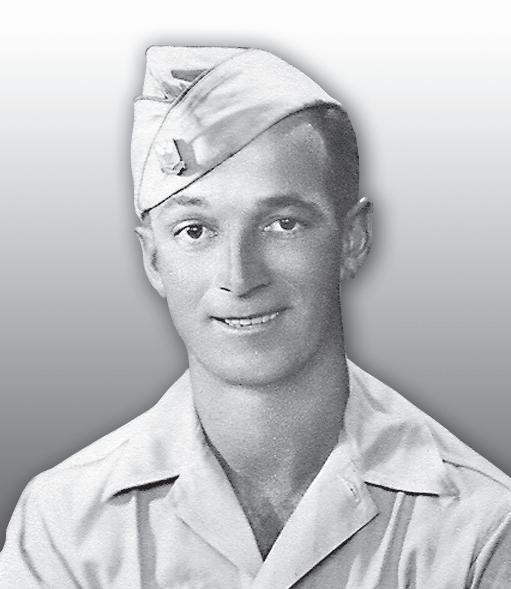

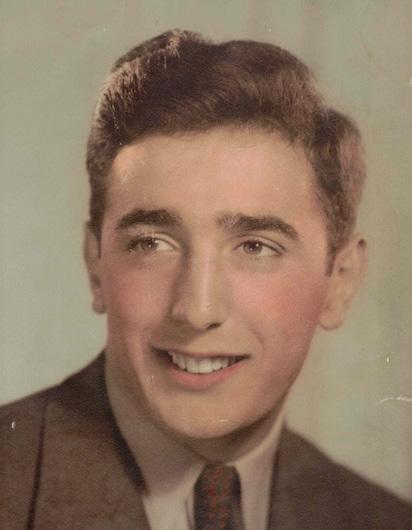

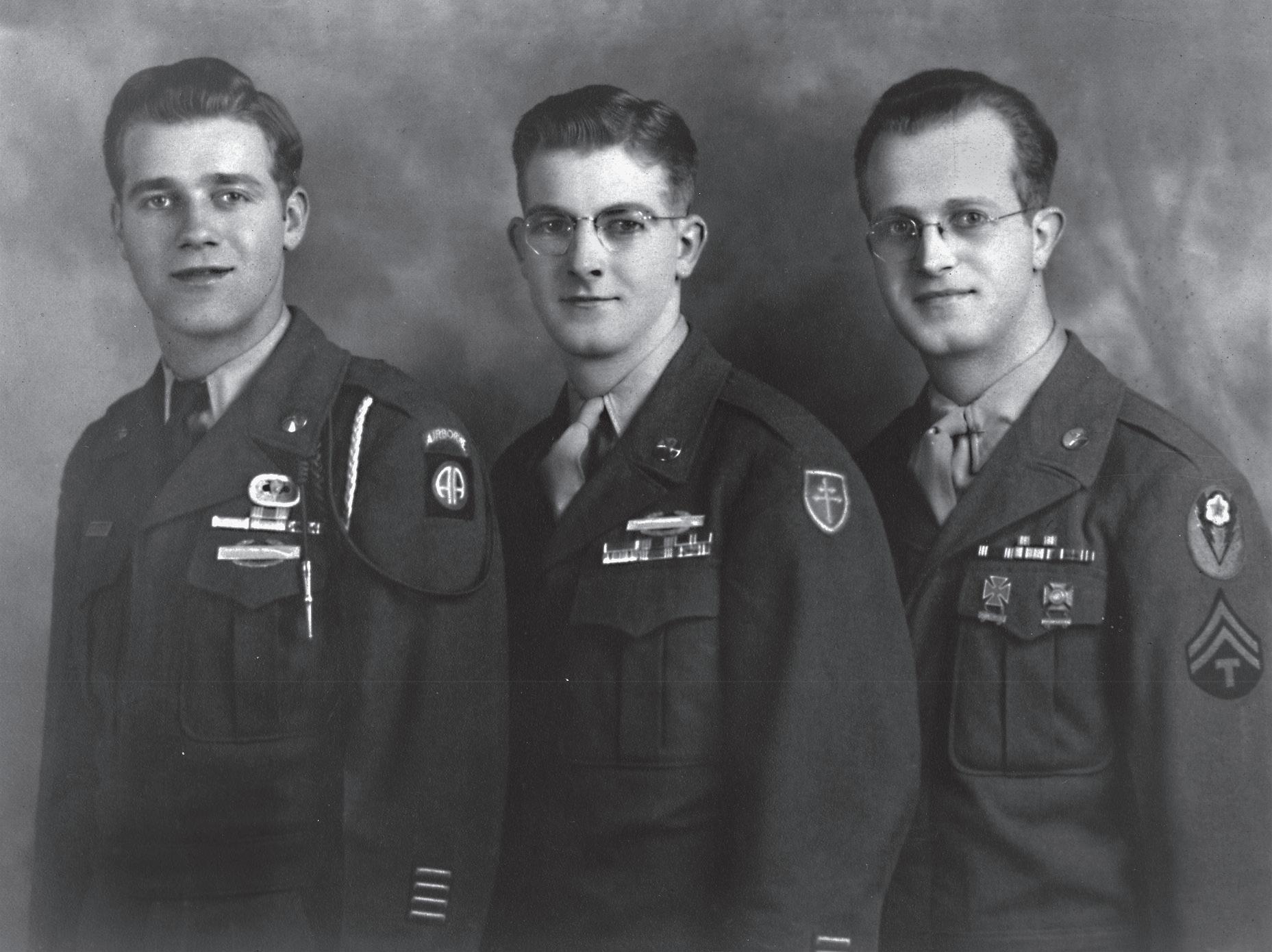

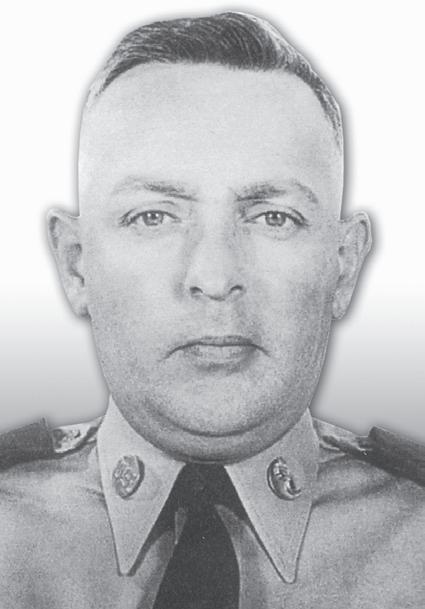

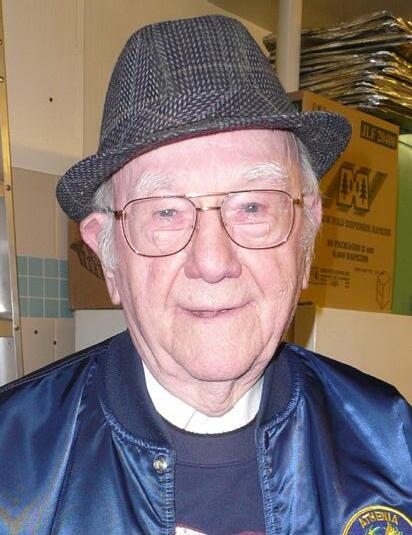

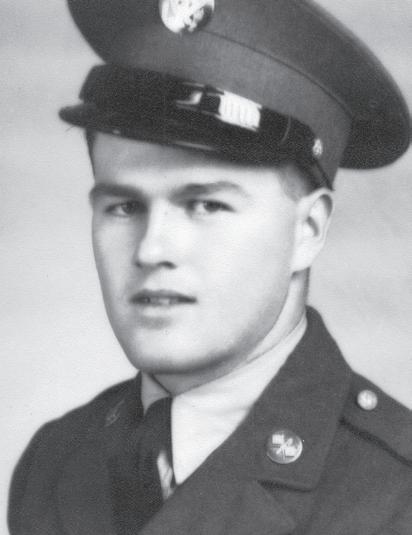

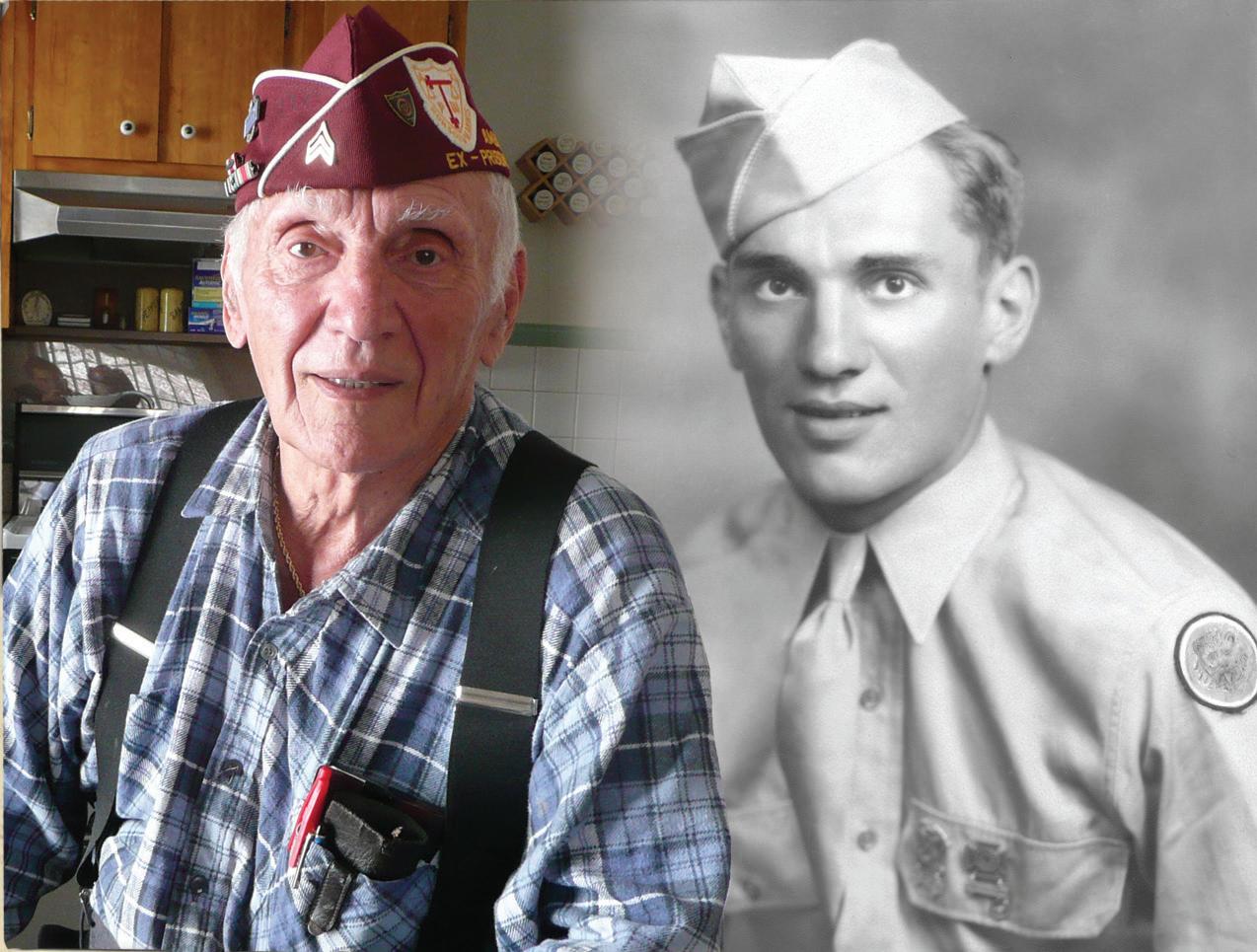

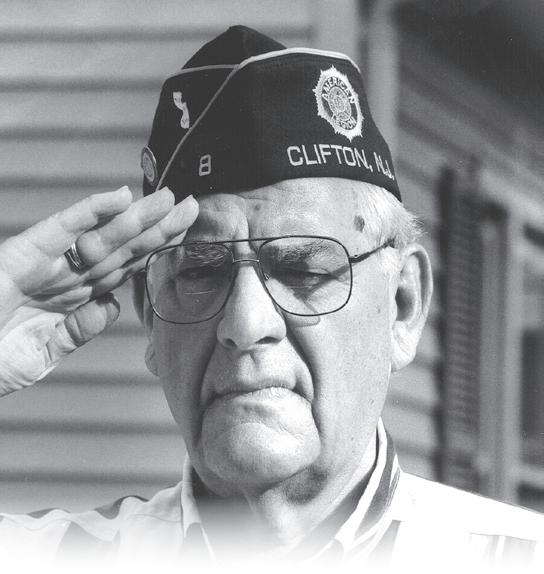

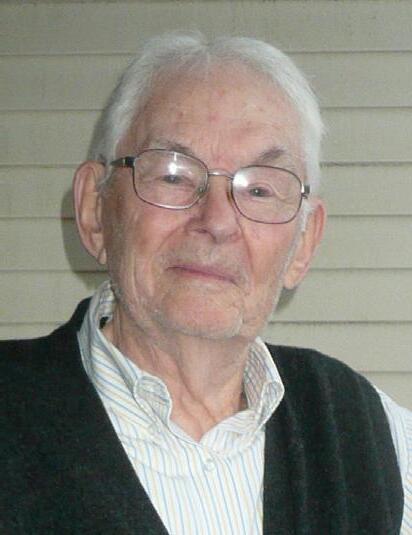

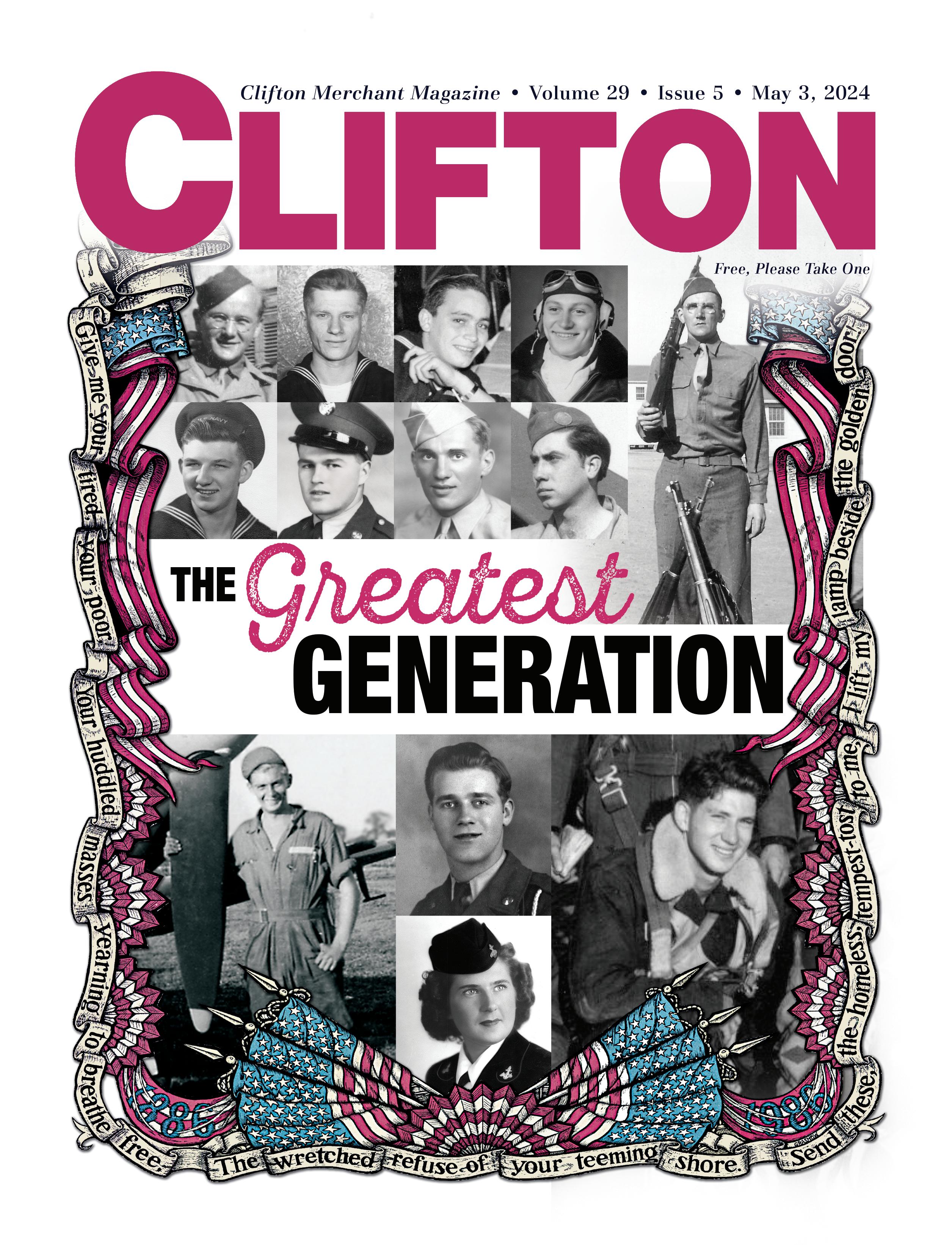

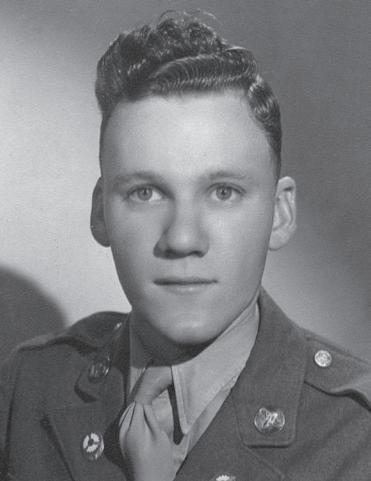

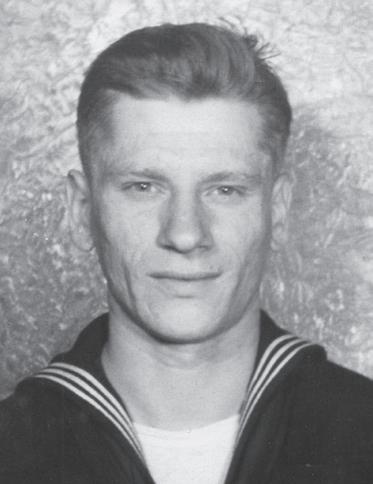

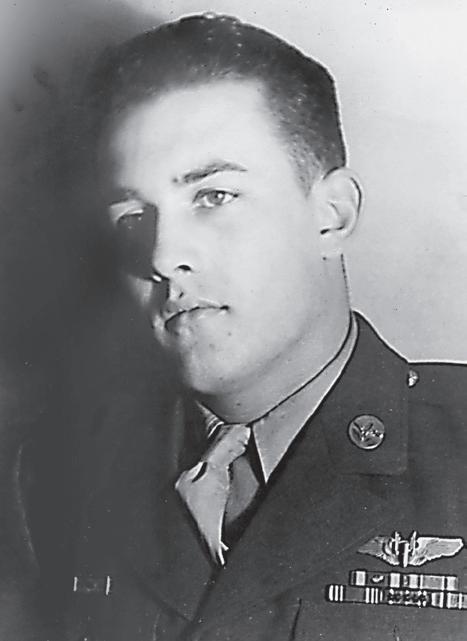

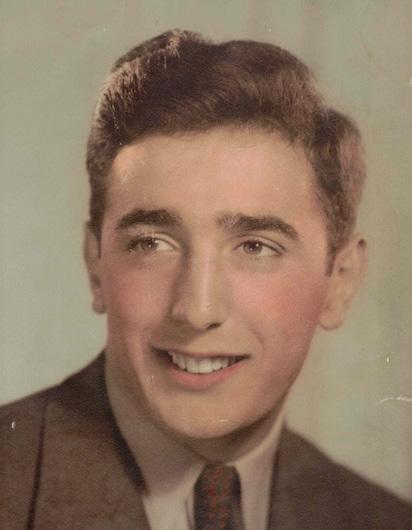

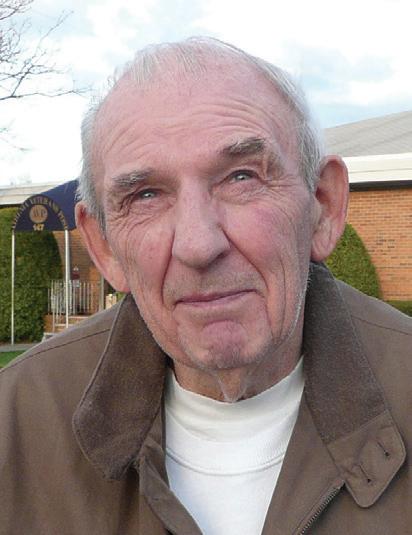

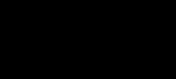

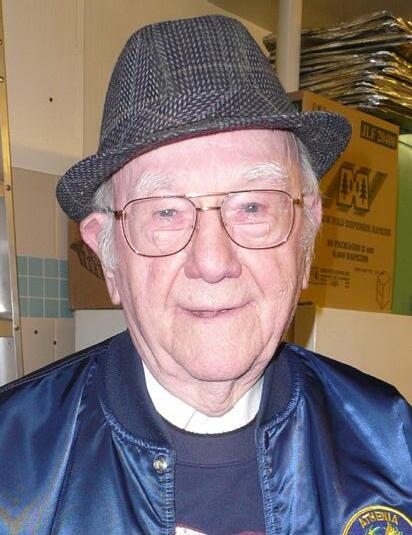

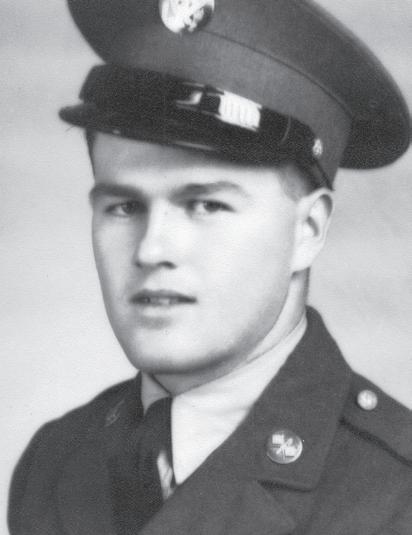

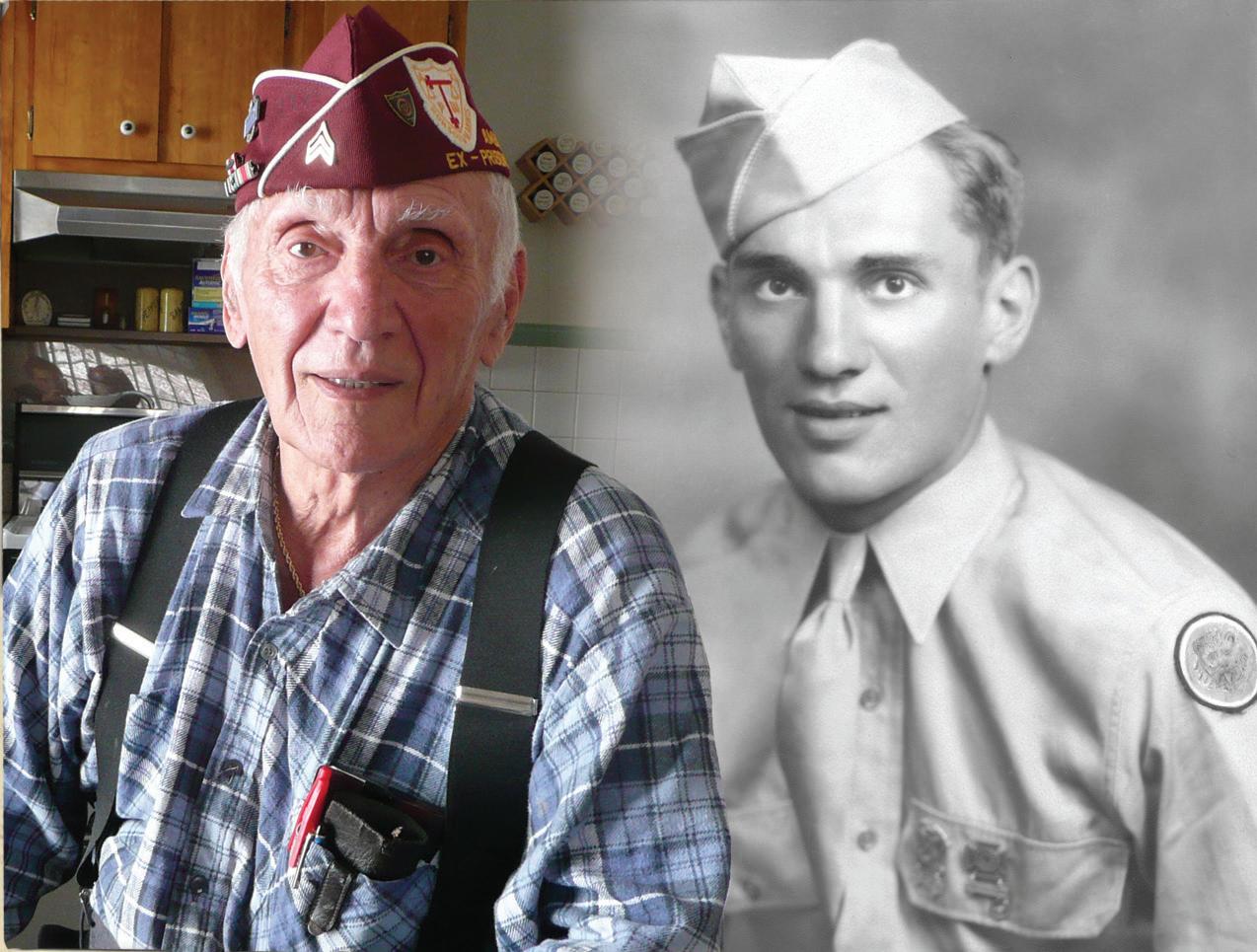

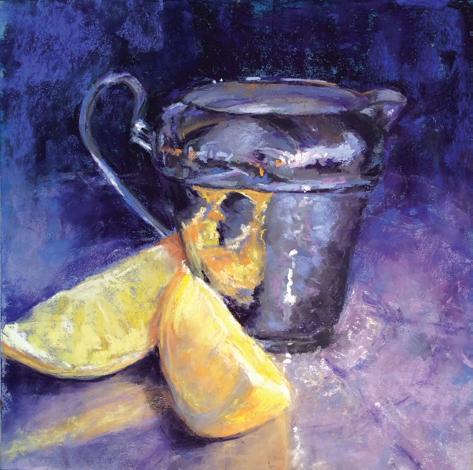

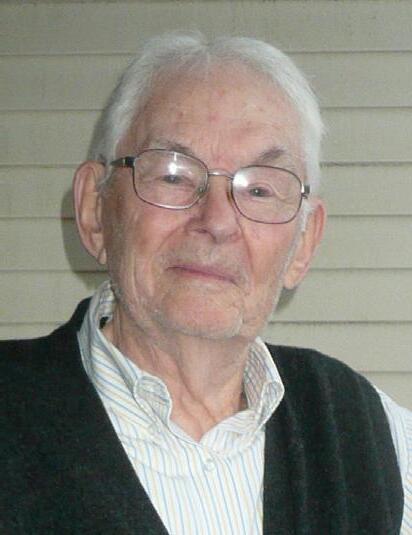

During my three decades as editor of this magazine, I’ve been privileged to publish and share the stories of the Greatest Generation – men and women from hometowns like Clifton who saved the world. Most were kids still in high school when Japan bombed Pearl Harbor. Days after, they enlisted. Others became officers. More joined the fight on the home front, laboring in factories, collecting scrap metal or selling war bonds. The story from WWII that I wish I’d been able to hear firsthand was how my dad, Joe Hawrylko, at right, enlisted in the Army at age 30.

From the Editor, Tom Hawrylko

My dad began his journey into Alzheimer’s disease in 1969, taking his stories of World War II with him. I often tried to find out more about him. In 1999, when I did a commemorative journal for our American Ukrainian Veterans Post in Perth Amboy, a man from our church shared a happy tale of how he ran into my dad on a troop transport at the war’s end. But that was about it.

Years back, my first son and his namesake Joe uncovered some of my dad’s story. Using Google, he found history on his grandfather. According to the book, Omaha Beach and Beyond: The Long March of Sergeant Bob Slaughter, we learned my father was stationed in Devonshire, England, with the 1st Battalion, D Company, in December 1943.

1288 Main Avenue, Downtown Clifton, NJ 07011 973-253-4400 • tomhawrylkosr@gmail.com turn our pages at cliftonmagazine.com

“Captain Schilling went on a recruiting expedition into the regimental rifle companies looking for large, tough men to carry the heavy machine guns and mortars – and he found them,” wrote author John Slaughter. One of those named was my dad, Joe Hawrylko, “… just a few of Captain Schilling’s hand-picked men, and they proved to be some of the best combat soldiers in D Company.”

While both my brother and I are tall, my dad was short, maybe 5’8” and sinewy. No other details on Joe are offered, but the book explains how their intensive infantry assault training prepared them for D-Day.

On June 6, 1944, 160,000 Allied troops – including Joseph John Hawrylko – landed along a 50-mile stretch of heavily-fortified coastline to fight Nazi Germany on the beaches of Normandy, France. My dad’s story is typical of Americans who served our nation honorably – too many of whom did not return.

With this edition, we pay tribute to our veterans and the Greatest Generation – shining a light on their service, keeping their memories eternal. In the following pages, you’ll learn about their resolve and unselfish commitment that Cliftonites demonstrated – ordinary people who would go on to do extraordinary things.

Editor & Publisher

Tom Hawrylko, Sr.

Art Director

Ken Peterson

Associate Editor & Social Media Mgr.

Contributing Writers

Ariana Puzzo, Joe Hawrylko, Irene Jarosewich, Tom Szieber, Jay Levin, Michael C. Gabriele, Jack DeVries, Patricia Alex

Ariana Puzzo

Business Mgr.

Irene Kulyk

distributed

$50 per year

14,000 Magazines are

to hundreds of Clifton Merchants on the first Friday of every month. Subscribe

or $80 for two Call 973-253-4400

© 2024 Tomahawk Promotions follow us on: @cliftonmagazine

Cliftonmagazine.com • May 2024 3

They would leave their homes, schools and places and employment – the same places we now reside in and enjoy today – to fight evil. While nearly all are gone now, we have their stories – ones we are all privileged to read.

On Sunday, Dec. 7, 1941, the world changed.

The Japanese sneak attack on the American naval base at Pearl Harbor took place just before 8 am in Honolulu, Hawaii. More than 300 Japanese fighter planes buzzed out of the sky, destroying or damaging nearly 20 American naval vessels, including eight battleships and more than 300 airplanes. Over 2,400 Americans died, including civilians.

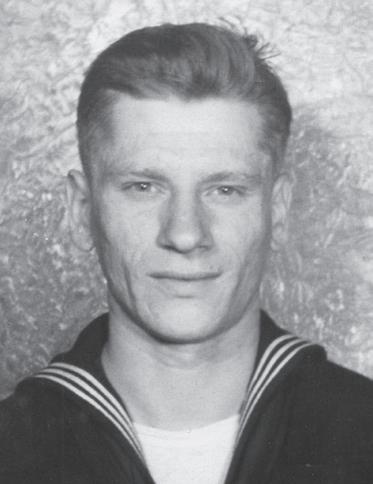

On the deck of the USS Curtis, Clifton’s Joseph Sperling – who once lived at 30 Richardson Ave. in the Athenia section and attended School No. 6 – watched as a wounded Japanese fighter plane tumbled out of the sky toward him. It was the last thing he saw. The plane crashed into the Curtis.

Sperling, a 17-year Navy veteran, became the first Cliftonite killed in action in WWII, leaving behind six sisters and three brothers, along with his mother. Sperling Park, located on Speer Ave., was later named in his honor.

The attack was a resounding success for Japan and its Axis partners, Germany and Italy. On Dec. 8, America entered the war. A quote attributed to Japanese Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto described what was to happen: “I fear all we have done is to awaken a sleeping giant and fill him with a terrible resolve.”

When the attack on Pearl Harbor happened, high school senior Jack Anderson was in the old Herald-News building on Prospect St. in Passaic, mixing darkroom chemicals. Anderson, who would later document Clifton’s history with his photos after WWII, remembered what happened: “Bells and whistles started going off in the wire room. I asked someone what it was, and they told me that happened whenever a special story was coming over. Soon, there was a constant stream of information coming over the wire. It made quite an impression on me. By that winter, most of the young men I knew were in the service.”

Anderson soon joined them in the Navy.

As the first wave of Japanese attackers swarmed over Hawaii, the Clifton Theater was packed with moviegoers. Fans were also watching the Paterson Panthers play in

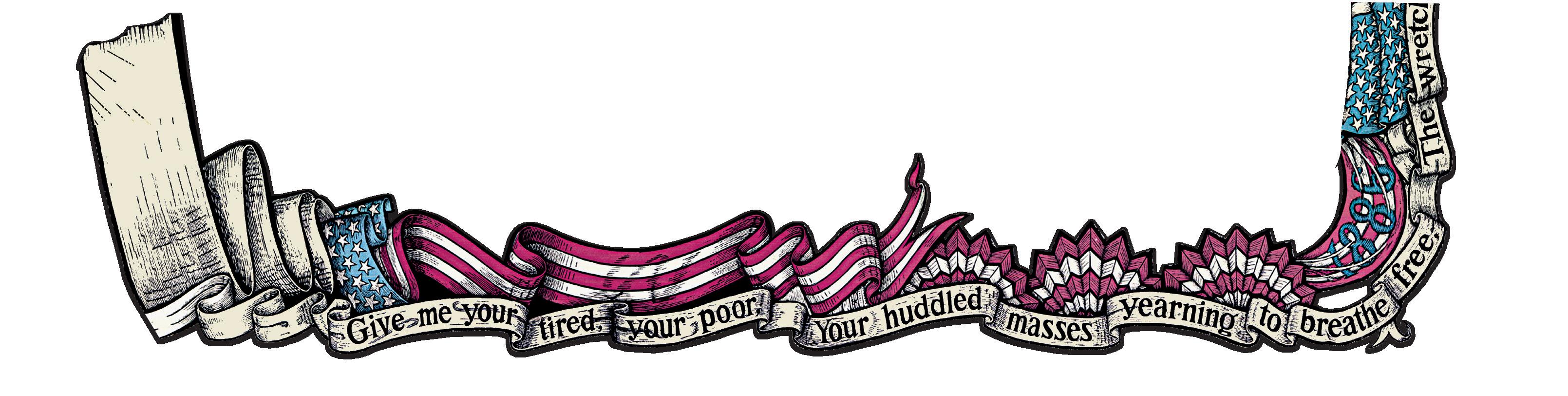

The attack on Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service on Dec. 7, 1941, which led to our nation’s formal entry into World War II the next day. Facing page, on Aug. 29, 1944, GIs with the 28th Infantry Division march down the Champs Elysees in Paris during France’s victory parade to mark the end of German occupation,

Hinchliffe Stadium where a Paterson Eastside student and future baseball Hall of Famer Larry Doby was working as an usher. Couples filled the dance floor of the Meadowbrook in Cedar Grove as Mario Giunta, a future Clifton police detective, listened to the band. The music stopped, the news was announced, and the band played on.

“What happened didn’t really sink in until we were riding home and talking about it,” Giunta said.

Clifton and surrounding towns mobilized for war.

The Herald-News reported reservists being summoned in Nutley, a defense group meeting in Passaic, and armed guards “increasing 300 percent” at the Curtiss-Wright Propeller Division Plant in Clifton. On Garrett Mountain, the “five-cents-a-look” binoculars were removed because it “enabled anyone to survey the entire vital Paterson defense area scene.”

4 May 2024 • Cliftonmagazine.com

On orders from an unnamed government representative, the Clifton Police were dispatched to seize control of the Takamine Plant at 193 Arlington Ave., which produced vitamins and chemicals. Eben Takamine, son of the late Japanese scientist Dr. Jokichi Takamine and his American mother, operated the plant. W.A. McIntyre, the plant’s vice president, told the Herald-News the company was “entirely American controlled” and was confident he could convince the soon-to-arrive federal agents that “their position was incorrect.”

The elder Takamine was once known as one of Clifton’s leading citizens; now, his family had become suspected combatants.

Fear of an air attack gripped New Jersey. Air raid sirens were made ready. Clifton Fire Chief James Sweeney told his men to prepare their equipment and know where emergency water sources were. Sweeney said their jobs would become more difficult if bombs tore up the streets or they were handicapped by blackouts.

Clifton students got a living history lesson.

“I was a voracious reader of newspapers,” said Homcy, then too young to serve. “I read anything about war. I even kept a map on my room’s wall and plotted the war – the battles, the Allied victories.”

“I was part of the first class to graduate from Clifton High after the bombing,” Harry Murtha said. “One of my classmates, Ray Zangrando, who also played football for the Clifton Arlingtons, was one of the first from my class to join the fight. There was no way to describe the unity in this country. We needed to be united. In the first months of the war, we took a terrible beating.”

Cliftonites said goodbye to their sons, as well as some of their daughters.

In the months that followed, the nation transformed itself to support the war effort. Factories operated on a threeshift, 24-hour day schedule. Bowling alleys opened all night to accommodate late-shift workers, and movies opened at noon and ran long past dark.

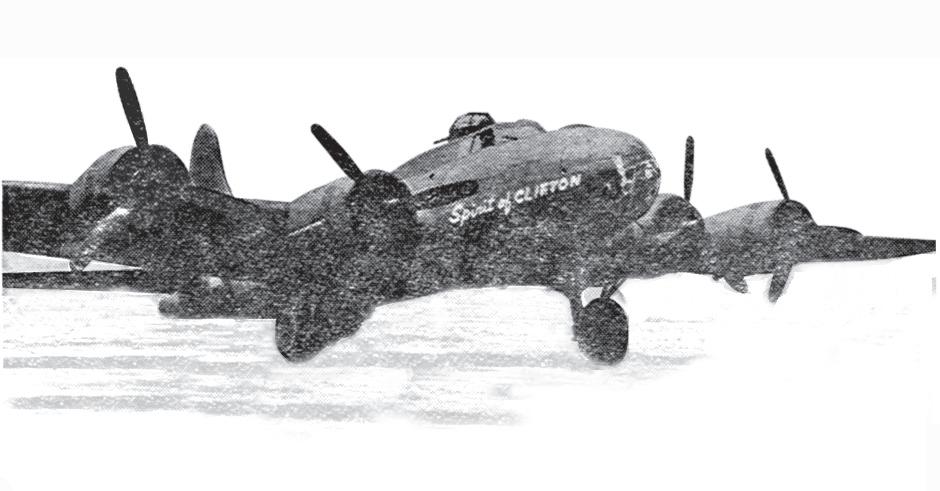

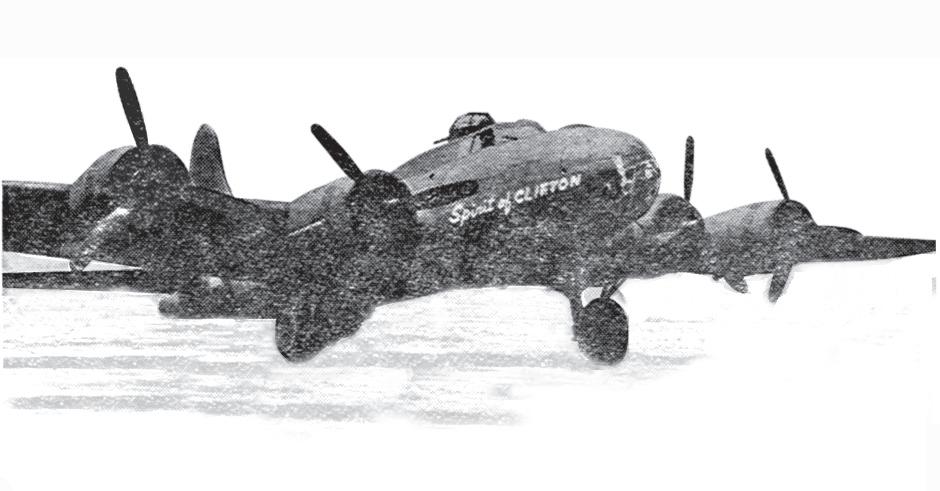

In April 1943, Clifton began a “Buy a Bomber” campaign, led by builder Frank Alberta. The city sold enough war bonds, a reported $760,000, to buy that bomber, a B-17 Flying Fortress christened, “Spirit of Clifton.” The U.S. War Dept. was so impressed, it named a P-T boat after the city, too. By July 1943, Clifton had sent 70,000 pounds of tin to support the war effort, encouraged by salvage chairman Augustine LaCorte.

Across from Main Memorial Park in a house on Main Ave., George Homcy, a future Herald-News reporter who would tell the city’s post-war history with his words, followed the conflict.

Because of WWII, the NFL held its practices at night, allowing football players to satisfy their wartime obligations by working by day in a defense factory or shipyard. This allowed dental student and future Clifton dentist, Angelo “Doc” Paternoster, to sign with the 1943 Washington Redskins. However, after finishing dental school, Doc quit the NFL and joined the Navy.

The war’s impact was devastating for many.

Pauline Chaplin of Alyea Terrace, received news that her son, Lt. Emil Chaplin, was killed on March 24, 1945. A CHS grad, winner of the Rensselaer Institute of Technology award in math, and a graduate of the School of Journalism at the University of Georgia, Chaplin was teaching school and preparing for a master’s degree when he enlisted.

For some parents, news from abroad brought relief. Julia DeNike of Fenner Ave. received word her son Pvt. Joseph Bush was liberated from a Nazi prison camp by the 83rd Infantry Division at Altengrabow, Germany in 1945. After Bush was captured, he was moved from camp to camp – his family not hearing from him since Dec. 1943.

WWII finally ended on Sept. 2, 1945. With the surrender of Japan, victorious and heroic men and women came home. Their return would transform Clifton from a land of farms to a thriving, prosperous city. But the stories of the people who lived through WWII and later built this city –the one we enjoy today – remain.

Read on to learn about the way it was…

Cliftonmagazine.com • May 2024 5

6 May 2024 • Cliftonmagazine.com

Cliftonmagazine.com • May 2024 7

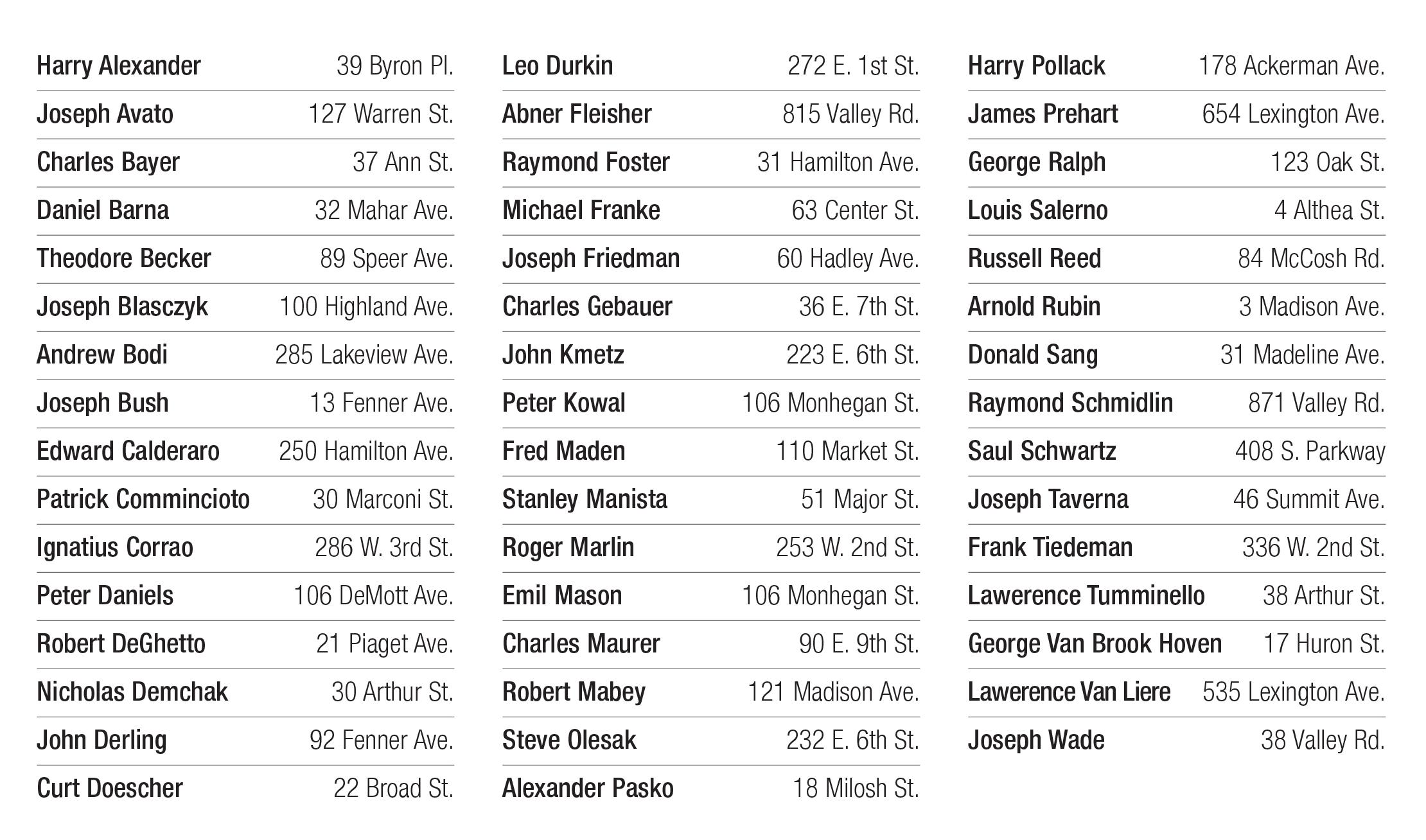

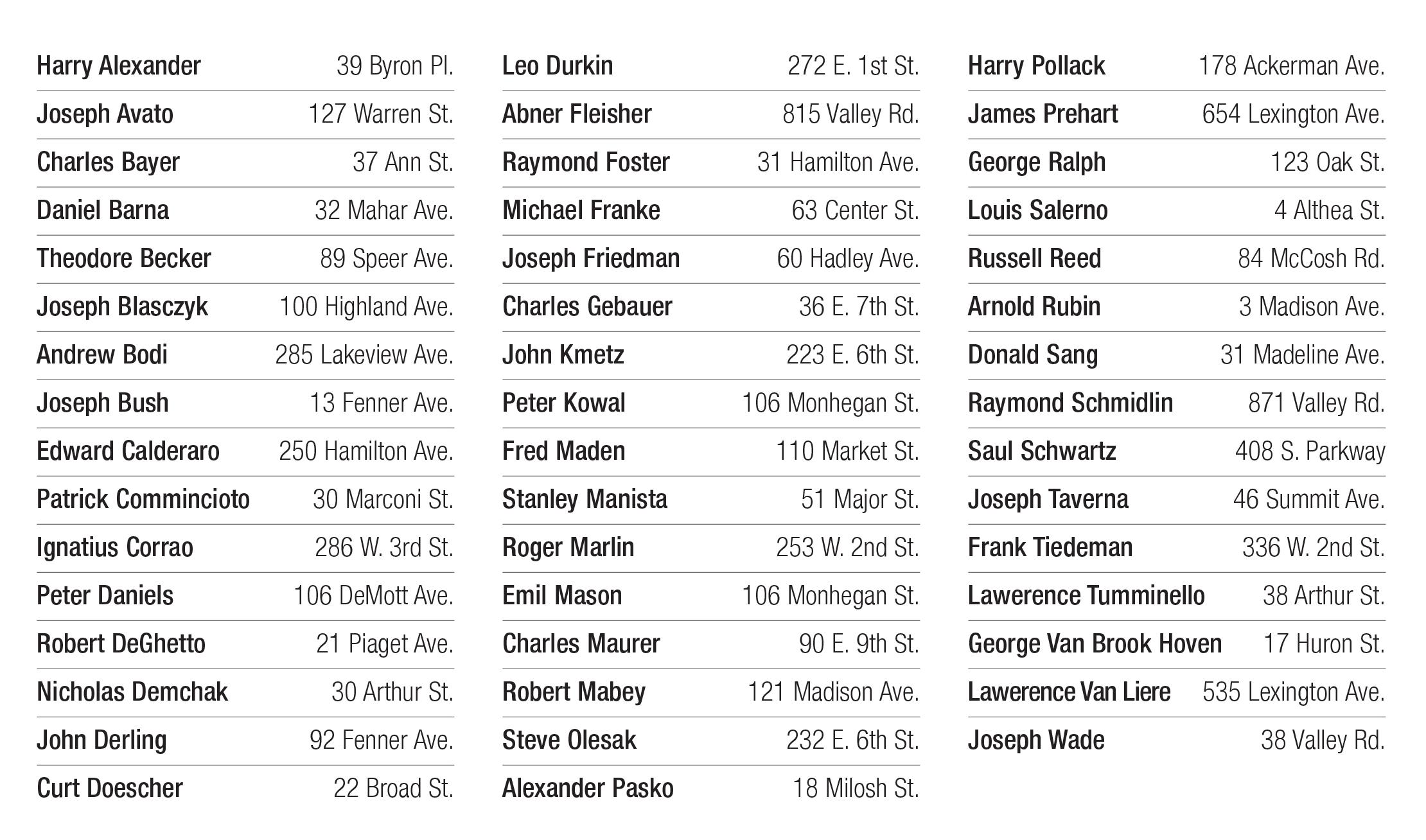

The Fallen. Organized by the war in which they served, we have again published the name of every Cliftonite who died while in service to our nation.

World War I

Louis Ablezer

Andrew Blahut

Timothy Condon

John Crozier

Orrie De Groot

Olivo De Luca

Italo De Mattia

August De Rose

Jurgen Dykstra

Seraphin Fiori

Ralph Gallasso

Otto Geipel

Mayo Giustina

Peter Horoschak

Emilio Lazzerin

Joseph Liechty

Jacob Morf, Jr.

William Morf

Edwin C. Peterson

Robert H. Roat

Alfred Sifferlen

James R. Stone

Carmelo Uricchio

Angelo Varetoni

Michael Vernarec

Cornelius Visbeck

Ignatius Wusching

Bertie Zanetti

Otto B. Zanetti

Memorial Weekend

Sunday, May 26

6 am: Volunteers needed to help set up 2,285 flags at Avenue of Flags, in and around City Hall, weather permitting Monday, May 27

8:15 am: Fire Dept. Service, Brighton Rd. followed by 9 am Parade from Clifton & Allwood Rd. to Chelsea Park

9:30 am: Service at Chelsea Park

11 am: Main Memorial Park Service

2 pm: Athenia Veterans, Huron Ave.

6 pm: Avenue of Flags Take Down

Questions? Visit Avenue of Flags barn near City Hall or call Joe Tuzzolino at 973-632-9225 to volunteer, or for info.

8 May 2024 • Cliftonmagazine.com

Cliftonmagazine.com • May 2024 9

World War II

Joseph Sperling

Charles Peterson

Thomas Donnellan

Jerry Toth

Frank Lennon

Joseph Carboy

Julius Weisfeld

Edward Ladwik

Israel Rabkin

Peter Pagnillo

Harold Weeks

William Weeks

Salvatore Favata

Herman Adams

Edward Kostecki

Charles Hooyman, Jr.

Salvatore Michelli

Richard Novak

James Potter

Adam Liptak

John Van Kirk

Carlyle Malmstrom

Francis Gormley

Charles Stanchak

Joseph Ladwik

Karl Germelmann

Robert Stevens

Albert Tau

William Scott

Benjamin Puzio

James Van Ness

Gregory Jahn

Nicholas Stanchak

Frank Smith, Jr

Carl Bredahl

Donald Yahn

Joseph Belli

Edwin Kalinka

Stanley Swift

Charles Lotz

Joseph Prebol

Walter Nazar

Benedict Vital

Thaddeus Bukowski

Leo Grossman

Michael Kashey

Stephen Messineo

John Janek

John Yanick

Herbert Gibb

William Nalesnik

Joseph Sowma

Bronislaus Pitak

Harry Tamboer

John Olear

John Koropchak

Joseph Nugent

Steven Gombocs

Thomas Gula

Raymond Curley

Harry Earnshaw

James Henry

John Layton

Charles Messineo

Joseph Petruska

Bogert Terpstra

John Kotulick

Peter Vroeginday

Michael Sobol

Donald Sang

Andew Sanko

George Zeim, Jr.

Robert Van Liere

Vernon Broseman

Harold O’Keefe

Edward Palffy

Dennis Szabaday

Lewis Cosmano

Stanley Scott, Jr.

Charles Hulyo, Jr.

Arnold Hutton

Frank Barth

John Kanyo

Bryce Leighty

Joseph Bertneskie

Samuel Bychek

Louis Netto

David Ward

Edward Rembisz

Lawrence Zanetti

Alfred Jones

Stephen Blondek

John Bulyn

Gerhard Kaden

William Lawrence

Robert Doherty

Samuel Guglielmo

Robert Parker

Joseph Molson

Stephen Kucha

James De Biase

Dominick Gianni

Manuel Marcos

Nicholas Palko

William Slyboom

Herman Teubner

Thomas Commiciotto

Stephen Surgent

Albert Bertneskie

Charles Gash

Peter Jacklin

Peter Shraga,Jr.

John Aspesi

Micheal Ladyczka

Edward Marchese

Robert Stephan

Roelof Holster, Jr.

Alex Hossack

Siber Speer

Frank Klimock

Salvatore Procopio

Harry Breen

Gordon Tomea, Jr.

Douglas Gleeson

Fred Hazekamp

Harold Roy

Andrew Servas, Jr.

Francis Alesso

Walter Bobzin

Vincent Lazzaro

John Op’t Hof

10 May 2024 • Cliftonmagazine.com

Cliftonmagazine.com • May 2024 11

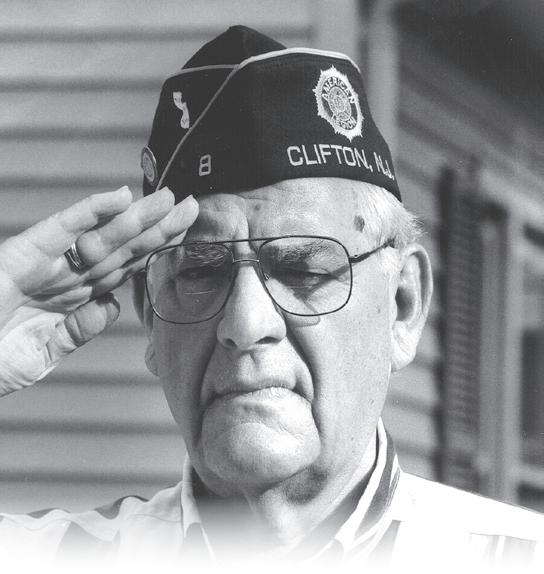

Looking back at Memorial Day 2004, Clifton’s WWII vets in front of the monument in Main Memorial Park.

World War II

Joseph Sondey

John Zier

Peter Hellrigel

Steve Luka

Arthur Vanden Bree

Harold Baker

Hans Fester

Patrick Conklin

John Thompson

Thomas Dutton, Jr.

Harold Ferris, Jr.

Donald Freda

Joseph Guerra

Edward Hornbeck

William Hromniak

Stephen Petrilak

Wayne Wells

Vincent Montalbano

James Miles

Louis Kloss

Andrew Kacmarcik

John Hallam

Anthony Leanza

William Sieper

Sylvester Cancellieri

George Worschak

Frank Urrichio

Andrew Marchincak

Carl Anderson

George Holmes

Edward Stadtmauer

Kermit Goss

George Huemmer

Alexander Yewko

Emil Chaplin

John Hushler

Edgar Coury

Robert Hubinger

Wilbur Lee

Vito Venezia

Joseph Russin

Ernest Yedlick

Charles Cannizzo

Michael Barbero

Joseph Palagano

William Hadrys

Joseph Hoffer, Jr.

Joseph Piccolo

John Robinson

Frank Torkos

Arthur Mayer

Edward Jaskot

George Russell

Frank Groseibl

Richard Van Vliet

Benjamin Boyko

Harry Carline

Paul Domino

John Fusiak

Louis Ritz

William Niader

Alfred Aiple

Mario Taverna

Sebastian De Lotto

Matthew Bartnowski

John Bogert

Joseph Collura

Matthew Daniels

James Doland, Jr.

Walter Dolginko

Peter Konapaka

Alfred Masseroni

Charles Merlo

Stephen Miskevich

John Ptasienski

Leo Schmidt

Robert Teichman

Louis Vuoncino

Richard Vecellio

Robert Hegmann

Ernest Triemer

John Peterson

Richard Vander Laan, Jr.

Stephan Kucha

‘Gigito’ Netto

Michael Columbus

12 May 2024 • Cliftonmagazine.com

Cliftonmagazine.com • May 2024 13

Korean War

Donald Frost

Ernest Haussler

William Kuller

Joseph Amato

Herbert Demarest

George Fornelius

Edward Luisser

Reynold Campbell

Louis Le Ster

Dennis Dyt

Raymond Halendwany

John Crawbuck

Ernest Hagbery

William Gould

Edward Flanagan

William Snyder

Allen Hiller

Arthur Grundman

Donald Brannon

Memorial Day, 1944, at the dedication of the honor roll at the Italo-American Circle of Albion Place, Valley Rd., one of 12 posted in Clifton neighborhoods to show support for the 5,500 men who shipped off to war. Note the names highlighted. They are the young men who were killed in action, just six of the 269 Cliftonites who would die during WW II.

Dedication of honor roll at Clifton Ave. and Clifton Blvd., June 6, 1943. From left, VFW Post 8 Commander Frank Lozier, John H. Olson and George Binns.

Vietnam War

Alfred Pino

Thomas Dando

William Sipos

Bohdan Kowal

Robert Kruger, Jr.

Bruce McFadyen

Carrol Wilke

Keith Perrelli

William Zalewski

Louis Grove

Clifford Jones, Jr.

George McClelland

Richard Corcoran

John Bilenski

Donald Campbell

James Strangeway, Jr.

Donald Scott

Howard Van Vliet

Frank Moorman

Robert Prete

Guyler Tulp

Nicholas Cerrato

Edward Deitman

Richard Cyran

Leszek Kulaczkowski

William Malcolm

Leonard Bird

John France

Stephen Stefaniak Jr.

Nov. 8, 1961

Plane Crash

Robert De Vogel

Vernon Griggs

Robert Marositz

Robert Rinaldi

Raymond Shamberger

Harold Skoglund

Willis Van Ess, Jr.

Gulf War

Michael Tarlavsky

14 May 2024 • Cliftonmagazine.com

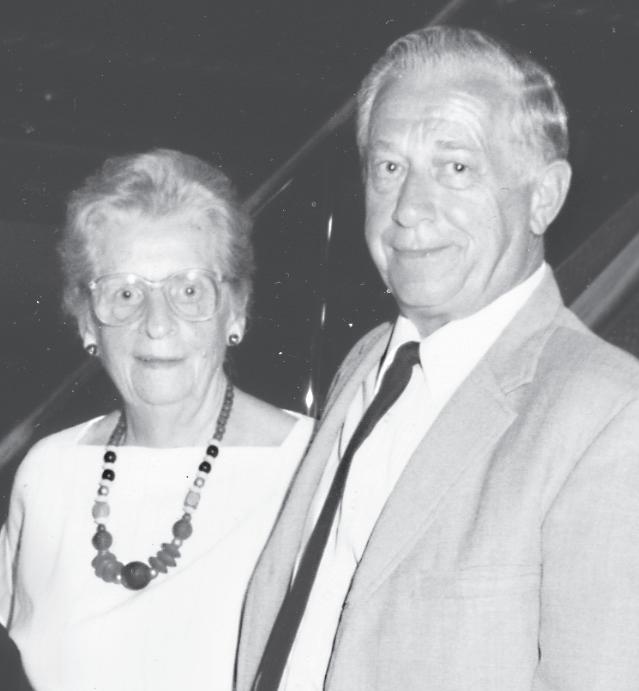

It’s a story you would expect to find in a war movie made during Hollywood’s golden age of the 40’s. Two brothers, one an infantry man and the other a tank crew member, are fighting their way across Western Europe on the road to Berlin, many miles apart from one another.

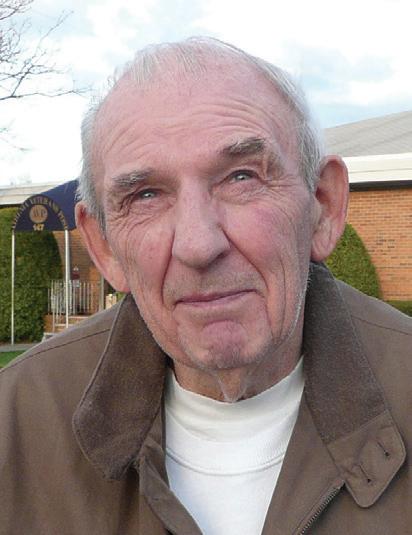

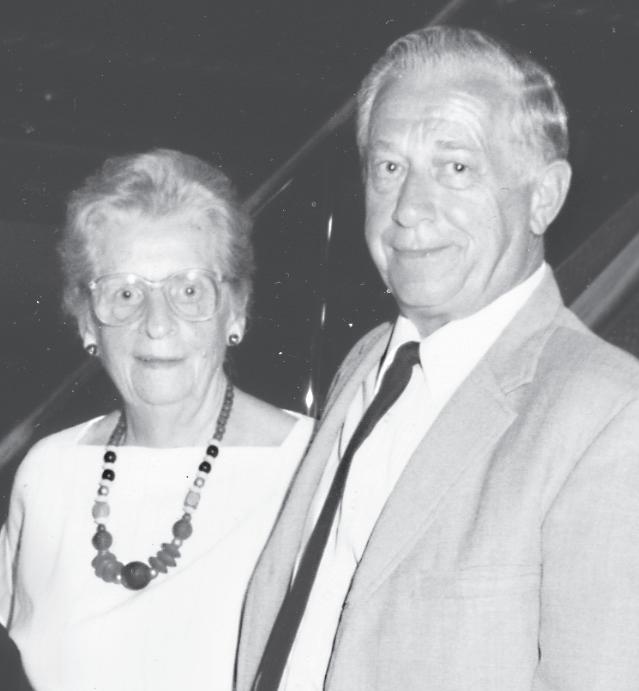

They help thwart the German thrust during the Battle of the Bulge, but shortly afterward, both are wounded in separate battles. They are evacuated to the same hospital in Versailles, France, where a chaplain helps bring them together for a joyful reunion. Only in Hollywood, you say? No, this is a true story, and the stars were the longtime Councilman Les Herrschaft and his brother, William, both now deceased.

“My brother was involved in the D-Day operation and I landed in France about three months later,” Les Herrschaft recalled in 1998. William, 12 years older, had been overseas for about a year before his younger brother arrived.

The Herrschaft brothers were kept informed of each other’s whereabouts through letters from their mother.

Then, around January 1945, First Sgt. Les Herrschaft of the Fifth Infantry took shrapnel in his leg during a battle in Nancy, France. Unknown to him, his brother’s’ tank had been destroyed during an encounter with a German force in Netz, France. William Herrschaft, who was also a sergeant, fought under the command of a fellow named Patton.

“When the chaplain visited me at the hospital, he told me there was a guy on another floor with the same last name,” Les Herrschaft said before his death in 2006. “My brother had been burned a little and wounded by shrapnel when his tank was blown apart, but when I saw him, he was doing much better.” Let your imagination take it from there.

Two wounded brothers, who hadn’t seen one another for more than a year, share hugs that are filled with joy, relief and love. Following his recovery, Les Herrschaft stayed in France and was assigned to guarding German POWs. William, who passed away in 1995, came back to the states.

You can see this story as an example of the irony of war or the plot for a great movie. Above all, however, you can see it as a story about two Purple Heart brothers who fought for freedom and won.

William Herrschaft and his brother Les, Clifton’s former councilman.

William Herrschaft and his brother Les, Clifton’s former councilman.

Cliftonmagazine.com • May 2024 15

Greatest Generation stories edited by Jack DeVries

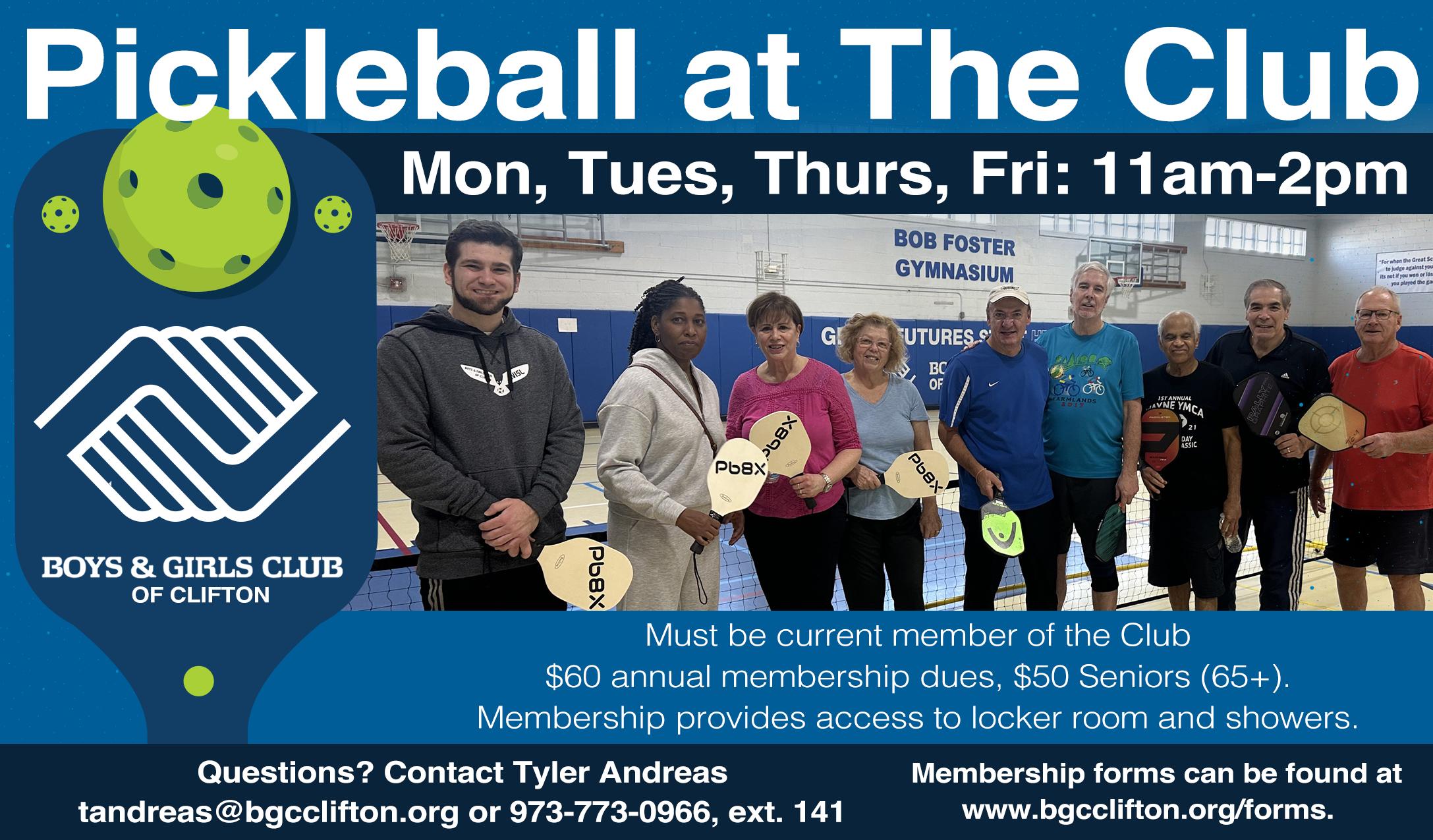

Support The Club

16 May 2024 • Cliftonmagazine.com

Join Clifton B&G Club Alumni to keep The Club strong. Join Us! Contact Maureen Cameron for more information: mcameron@bgcclifton.org or 973-773-0966, ext. 144 Contact Chris Street To Sponsor Our Events 973-773-0966 x155 • cstreet@bgcclifton.org Join Us! Alumni & friends Cliftonmagazine.com • May 2024 17

Clifton Gunner Staff Sgt. Charles Librizzi flew aboard a Flying Fortress B-17 bomber. One harrowing mission was a bombing raid of Leipzig, Germany, where the sky filled with antiaircraft shells. Librizzi, who lived on Ackerman Ave. and received an Air Medal with five oak leaf clusters, described: “They began by knocking out our No. 1 and 2 engines right after ‘bombs away.’ That cost us 4,000 feet of altitude. A burst in the nose about that time wounded the pilot and co-pilot; another in the rear hit the tail gunner.

“The distance between us and the ground continued slipping away too fast for comfort, and we were tossing out everything that wasn’t bolted down, and some stuff that was. Flak was still coming up fast and fancy. A close one ripped the No. 4 engine and it wouldn’t give full power, leaving us with just an engine and a half to fly on. And we did. It took some mighty sharp maneuvering, but the pilot pushed that wreck over the lines to an emergency landing field in Brussels.” After WWII Librizzi served on the Clifton Police Department for 30 years, retiring as a captain in 1977.

Robert Wilcox, an Army Air Force staff sergeant who served in Guam, came from a family of soldiers. Born in Pennsylvania, Wilcox moved to Paterson and then Clifton, and drove a truck for Hoffman-LaRoche. His great grandfather fought in the Civil War, his grandfather saw action in the Spanish American War, and his father would have fought in World War I if not a saw mill accident.

Along with a younger brother serving in Korea, two of Wilcox’s siblings fought in WWII and his brother, Walter, served with future president John F. Kennedy aboard PT boats, earning the Silver Star and Purple Heart.

After basic at Fort Dix, Wilcox shipped to the Mariana Islands in the West Pacific, two months before the Battle of Saipan. But he never touched foot on Saipan. Instead, on the night of their arrival in April 1944, Wilcox and his crew were ordered to sail another 125 miles southwest, under the cover of darkness, to Japanese-occupied Guam.

In 2008, Wilcox, then age 85, cried as he recounted that night. “Guys were scared to leave the ship,” he sobbed. “They were screaming, ‘Mommy! Mommy!’” When they got to the beaches, Wilcox and the other men shot at the enemy. He made it ashore safely, but soon developed malaria and had to be hospitalized for a week. “I was shak-

ing, wringing wet with the sun beating down on,” Wilcox recalled. “I couldn’t keep warm.”

Regaining his health, Wilcox returned to base where he loaded bombs on B-29 bombers in preparation for the Battle of Guam in 1944.

If the “Seabees” were the backbone of the military during WWII, Clifton’s Raymond Chitko of Jascott Lane was one of the vertebrae. The Seabees are the Construction Battalions (or CBs) of the U.S. Navy, constructing bases, paving roads and airstrips, and monitoring drinking water, like Chitko did. After 85 days at sea, he and his crew finally arrived in the waters around Palau in September 1944, just as the Battle of Peleliu began. But when the ship landed, Chitko developed a bad case of dysentery.

“They took me off the ship and drove me through the battle area to the hospital,” Chitko remembered. While there, he saw many who were in a lot worse shape than he was. “You couldn’t help but feel sorry for them,” he said. “They were so alone.”

Chitko was sick for two weeks before returning to work filling potholes on the airfield and building shelters for the soldiers. “We were like the servants on the island,” said Chitko, adding that at one point, the men weren’t getting enough food. “We were tired of eating mutton so we threw grenades into the water and waited for the fish to float to the surface.”

The Battle of Peleliu ended with an American victory on Nov. 25, 1944, six weeks after it began. When considering the number of men involved (less than 39,000), Peleliu had the highest death toll rate of any battle in the Pacific Theater.

18 May 2024 • Cliftonmagazine.com

Charles Librizzi and Robert Wilcox in 1944 and 2008.

Cliftonmagazine.com • May 2024 19

to the Seabees base in Rhode Island. It was there when he heard about the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Raymond Yannetti’s life took him from early days in Paterson to most of his life in Clifton. But that journey included a stop at a perilous time and place: Okinawa, Japan, April 1945.

As Marines and Navy personnel prepared to invade the island, Yannetti helped in their delivery, serving on a three-member team aboard a landing craft, vehicle, personnel (LCVP) or “Higgins boat,” bringing troops to the Okinawa beaches as part of the second main assault.

“Nobody slept that night before the invasion,” he said. The Higgins boat crews sympathized with the Marines being delivered into harm’s way.

“We left those poor soldiers, and many told us they were willing to swap places with us,” Yannetti recalled. “But we ourselves weren’t necessarily safer.”

Higgins boats were vulnerable to Japanese suicide air strikes (kamikaze raids) and suicide swimmers infiltrating the bay.

After the war was declared over, caution still was warranted. “Japanese submarines still lurked, and we didn’t know if they’d gotten the word,” Yannetti said. As September arrived, a typhoon wreaked havoc with U.S. naval operations. “Imagine if that had happened as the invasion of Japan was taking place.”

Yannetti also saw duty in ferrying British and American ex-Prisoners of War to other locales, including Manila in the Philippines. “The orders came that ex-POWs were to eat first; they had elite status,” he said. “I never saw guys

eat so much food in my life.” Some ate too much, and became ill.”

Returning home, Yannetti learned his two brothers, also in the military, had survived. But he couldn’t escape the sadness and pain brought by WWII.

As a high school student, Yannetti had worked at a German bakery in Paterson, and was friendly with the owner and his son. Checking on both upon his return, Yannetti found the man’s son had died in combat while in the baker’s childhood home town.

“Sad,” was all Yannetti could say. Yannetti lived on Union Ave. for 50 years before moving to the Allwood section.

Although Pauline Trella couldn’t serve on the front lines, getting involved with WWII came naturally to her. “I worked in the Curtis Wright defense plant in Caldwell,” recalled the 1940 CHS graduate. “I was a precision inspector.”

Clifton’s version of “Rosie the Riveter” was happy to help on the home front. However, after conversing with a friend, Trella felt there was more to do. “My friend, Ann Bajor, joined the WAVES (Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service),” she said. “She eventually encouraged me to join.”

Prior to the WAVES, founded in 1942, there was no way for females to enlist in the military. After joining in 1945 and completing her training, Trella was shipped out to Corpus Christi, Texas. “We relieved the men,” she recalled. “We opened the field for flying on teletype and also closed the field for flying. We also kept the officer’s logs.” Yeoman 2nd class Trella’s stay was short as Japan and Germany surrendered and the Navy was releasing a lot of extra personnel.

Raymond Chitko.

Raymond Yannetti.

20 May 2024 • Cliftonmagazine.com

Pauline Trella.

Cliftonmagazine.com • May 2024 21

“I was offered a lot of benefits (to stay in the Navy),” Trella said. Despite the incentives, the young woman’s best bet was to return to her hometown. “Why stay when your friends all go home?” Trella returned to Clifton and was among the early members of the Athenia Veterans Post, founded in 1946.

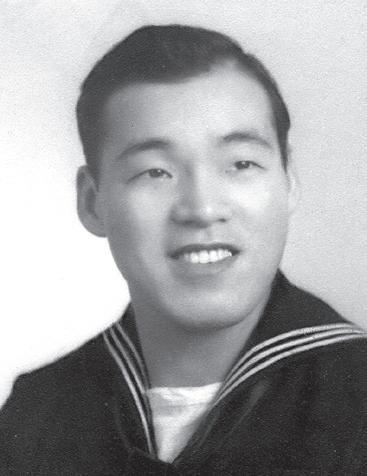

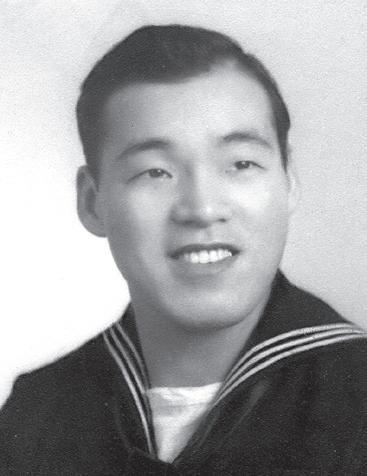

Clifton residents may be familiar with Lou Wong Drive, off of Brighton Road. The street is named for Wong, a first generation, Chinese-American who served his country proudly during World War II.

Like many of the Greatest Generation, Wong, pictured here, was moved to enlist in the U.S. Navy as the tyranny of World War II spread across the globe. While he was trained as a sheet metal specialist aboard the repair ship USS Tuitilla, which served in the Pacific theater, Wong’s ability to speak Chinese fluently was perhaps his greatest service to our country.

As his ship sailed the seas of the Pacific, he acted as a translator during several surrender ceremonies on Formosa Island and mainland China.

After Wong left the Navy in December, 1945, he received an engineering degree from City College, New York and went to work at ITT as an industrial engineer, where he worked for 29 years before taking a position with Mosler Airmatics for 10 years, before retiring.

Wong and his wife, Dora, moved to Clifton in 1951, where they raised their four children. He joined the VFW and American Legion. However, most of his energy was spent with the vets of VFW Post 6487.

He died on March 1, 1983, at 66 after a brief illness. Wong’s service to Clifton will always be remembered because of the street named in his honor. His wife and four children are grateful to know he is so appreciated and remembered.

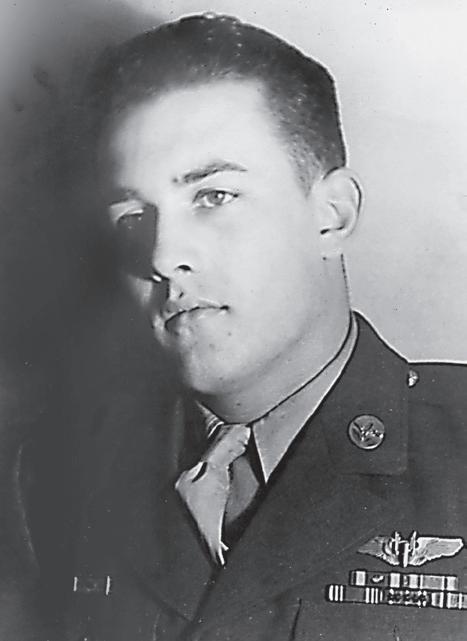

In the opening scenes of the 1998 movie, Saving Private Ryan, we see a veteran walking slowly through a military cemetery in Normandy, France. He is surrounded by row upon row of white marble crosses and Stars of David. He then looks out upon the English Channel, where the United States, Britain and Canada once carried out the largest military operation in history.

Lou Wong, Christopher Sotiro in 1944 and in 2000.

Clifton resident Christopher Sotiro made that same walk and took that same look five decades after he was part of the invasion in 1944.

“I went back for the 50th anniversary of the D-Day invasion in 1994. When I found out about it, I said to my wife, we have to go,” said Sotiro, who landed in France with his infantry division shortly after the invasion on June 6, 1944. He was later captured by German troops and spent eight months in a prisoner of war camp.

“I went back to the town where I was captured and spent a few days in Paris. The Normandy countryside is beautiful. But when I got to the cemetery, I got this awful feeling,” recalled Sotiro.

The perfectly manicured cemetery that Sotiro visited sits on a desolate, windswept bluff above Omaha Beach, the scene of some of the most intense fighting on that June day 80 years ago. It was the brutality of this battle that director Spielberg attempted to recreate in Saving Private Ryan.

“The wind comes in off the water and whistles through the tall trees that are up there at the cemetery. It’s a very eerie sound,” Sotiro said. “And all around, you see the graves. Thousands of them.” Sotiro then visited a nearby museum that commemorates the sacrifices that were made in the first stage of Europe’s liberation from the Nazis.

“I asked for tickets and the Frenchman there saw my hat, which had the insignia of my outfit, the 110th infantry regiment,” Sotiro recalled in our May 1999 magazine. “He pointed at my hat and said to me in the best English that he could muster, ‘No pay. You came.’ That got me choked up. He was thanking me for the first time I was here.”

22 May 2024 • Cliftonmagazine.com

FOCUS ON THINGS MOST IMPORTANT TO YOU Leave financial matters to us Since 1976, Polish & Slavic Federal Credit Union serves the Polish-American community offering a full scope of financial products and services for the entire family. Thanks to the loyalty and trust of our members, we also create the strength of the Polish community in the United States. Open an account online at www.psfcu.com or visit our branch in Clifton 990 Clifton Ave., Clifton, NJ 07013 tel. (973) 472-4404 OUR CREDIT UNION IS MORE THAN A BANK! Membership restrictions apply to open an account. Other restrictions may also apply 1.855.PSFCU.4U (1.855.773.2848) www.psfcu.com Cliftonmagazine.com • May 2024 23

Joe Menegus was the son carpenter and a child of the Depression. Born in 1925, he grew up in Lakeview and remembers eating string bean sandwiches and his father’s constant search for work. To help, young Menegus worked on Clifton farms (located where Richfield Village is today) for 10 cents an hour, laboring 10 hours a day.

He also loved sports, forging his parents’ signatures on a permission slip to play football. By his senior year, Menegus was named team captain, selected to the first-team New Jersey All-State squad, and led the Clifton Mustangs to a 5-2-1 record.

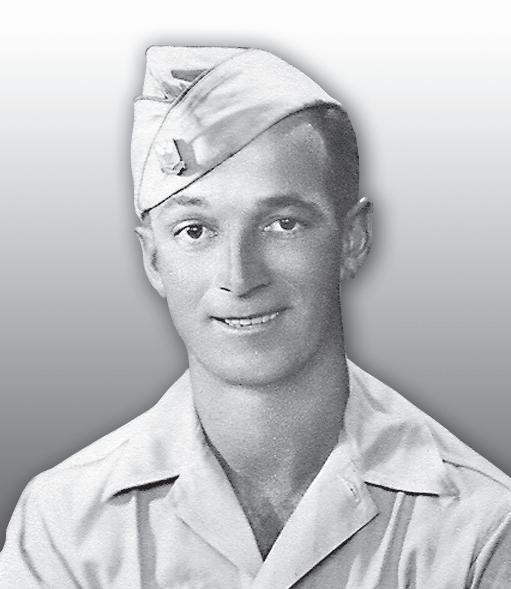

At left, Joe Menegus. That’s Willie Zawisha, who was bed-ridden most of his life, dictating a letter to his niece that would be sent to “Clifton boys,” serving across the globe, back during World War II.

The next year, Menegus heard the news of Pearl Harbor at Decker’s, a luncheonette on Lakeview Ave. where friend Tony “Yiggs” Romaglia worked. Joe soon became an Air Corp flying cadet and a tail gunner on a B-24 Liberator, part of the 450th Bomber Group, 720th Squadron.

“By the time I got over there in 1944,” Menegus said, “the Luftwaffe (Germany’s Air Force) was not what it once was. The ground fire or ‘flak’ was more of a danger.” The B-24’s that Menegus flew on were nicknamed “Cotton Tails” because of their distinctive white end markings. Flying on missions sometimes 10 hours long, his crew attacked industrial targets from their base in Mandoria, Italy, climbing over the Adriatic Sea and snow-covered Alps into Germany.

During missions, temperatures on the plane could reach 50 degrees below zero, and it was the co-pilot’s responsibility to constantly check on the tail gunners, making sure they didn’t pass out from the extreme cold.

“Our first mission was a baptism of fire,” Menegus said. “After our P-51 fighter escort left us, we got into a tight formation to begin our bombing run. The flak was like a thick black cloud, and we could hear shrapnel pinging as it cut into the plane’s fuselage. Our nose gunner fainted. We dropped our bombs, executed evasive action, and headed for home.

“Were we scared? You bet we were! Our squadron lost several planes that day.” On another mission, Menegus remembers that he almost didn’t return. “We were on an

easy mission, a ‘milk run’” Menegus said. “Our target was a railroad hub in southeastern Germany. The yard was heavily defended by German guns, the 88s. They knocked the hell out of us. We lost two planes out of the squadron of seven.”

Though able to fly, Menegus’ plane was in danger. “We got shot up very badly and lost two of our engines. When that happens, you’re on your own – the other planes leave you because you’re a cripple. To get home, we had to make it over the Alps. Our pilot, Lt. Skuby, wanted to head for Russia because he knew how to speak the language. But we had heard stories that the Russians treated Americans like prisoners of war, and knew that German fighters patrolled the Russian front.”

Instead, the crew voted to try and make it back. To lighten the plane, they threw all their ammo and guns off – anything that had any weight. “We all had our chutes on ready to bail out,” Menegus said. “But when you looked down, you could see nothing but mountains. Even if we jumped, where would we go? We would’ve frozen to death.” Thankfully, the plane made it over the Alps and landed safely in Yugoslavia, near a British base. A few days later, the crew was back in the air.

“The worse part of the Air Corps,” said Menegus, who flew 30 combat missions, “was knowing that you had to go back up again. You saw a lot of your friends go down in flames. We lost more men on those planes than the Marines and Navy lost during WWII combined.”

24 May 2024 • Cliftonmagazine.com

Cliftonmagazine.com • May 2024 25

STK# 24K85. Offer shown based on $3,499 down, plus $177 first monthly payment, $650 acquisition fee, plus tax, title, license and registration fees. No security deposit required. Offer shown total lease payments are $4,248. Purchase option at lease-end $14,881.80. Lessee is responsible for insurance, maintenance, repairs, $.20 per mile over 10,000 miles/year, excess wear, and a $400 termination fee*. To qualifying candidates with approved credit through Kia Finance America (KFA).

$448 first month payment = $5,917 due at signing plus tax and motor vehicle fees. Price includes $645 bank fee + $694 documentation fee. 0 Security Deposit. Lessee responsible for excess wear and mileage over 21,000 miles at $0.20 per mile. Lessee has option

JUNCTION RT 46 & RT 3 • CLIFTON, NJ A VEHICLE FOR EVERY LIFESTYLE FETTE AUTO GROUP HHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHH GOING ON ALL MONTH LONG! H H HHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHH

Lease For$177 FORTE LXS

Per Month for 39 Months • $5,469 Down Lease For $329 New 2023 FORD MUSTANG MACH-E GT CROSSOVER STK 23T410, VIN# 3FMTK4SE8PMA38389, M.S.R.P. $55,384. Residual $25,704, 10,500 miles per year, $5,469 down +

to purchase a vehicle at lease end at price negotiated with dealer at signing. Per Month for 36 Months • $4,988 Down Lease For $499 QX60 PURE AWD Stock#24QX81, VIN#RC340225. Well-qualified lessees lease a new 2024 QX60 PURE FWD for $499/Month for 36 Mos. To qualifying candidates with approved credit, residency restrictions apply. MSRP $51,770.00. Residual: $34,168.20. $4,988 cash down, plus tax, title, $694 doc fee and dealer fees.

per mile for mileage over 10,000

supplies last.

The

HHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHH 26 May 2024 • Cliftonmagazine.com

Per Month for 24 Months • $3,499 Down

$0.25

miles per yr. While

Offer subject to change without notice.

dealer is not responsible for typos. Price includes all Factory rebates and Factory incentives to qualifying candidates with approved credit. Doc fee of $694 not included on all offers. See dealer for complete details, Offer ends 06/30/2024.

JUNCTION RT 46 & RT 3 • CLIFTON, NJ FORD & KIA: 973.779.7000 • INFINITI: 973.743.3100 SALES: Mon-Thurs: 9am-7pm, Fri: 9am-6pm, Sat: 9am-6pm • SERVICE: Mon-Thurs: 7:30am-7pm, Fri: 7:30am-6pm, Sat: 7am-3pm FetteAuto.com HHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHH HHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHH LARGE SELECTION OF NEW & PRE-OWNED VEHICLES THANK YOU FOR ALLOWING US TO SERVE YOU! CONTACT OUR SERVICE DEPARTMENT AT: 973-685-4158 WE SERVICE ALL MAKES & MODELS! TEST DRIVE OUR WIDE VARIETY OF EV’S TODAY ELECTRIFY YOUR RIDE Cliftonmagazine.com • May 2024 27

If you weren’t in the service, you waged a campaign on the home front. From participating in scrap drives, buying war bonds, and doing everything possible to repay all the “boys” for what they were doing for us, America chipped in.

For instance, Stanley Zwier, who was Clifton Mayor from 1958-62, helped to launch the Athenia Canteen at 754 Van Houten Ave. in the early part of 1942.

After the war, the storefront became the first headquarters for the Athenia Veterans Post, Zwier noted in an interview prior to his his death in 1999.

“Most of us had family in service. We wanted to do something nice for the boys from Clifton who were home on furlough or getting ready to ship out,” he said.

“We gave each serviceman a carton of cigarettes. We would also give them theater tickets and take them out for a snack,” said Zwier, whose three brothers, Robert, Henry and Michael, were all in the Army.

The organization also published the Canteen News, which was mailed to Clifton residents who were serving in the military to keep them abreast of hometown happenings.

Zwier said Clifton’s version of a USO Club had support from the business community and private citizens, and it was manned by he and members on the Athenia Canteen Committee.

They included Rose Bucaro, Margaret Svec, Frances Mirabella, Mary Bieganowsky, Steve Kleaha, Marie Van Acker, Bob Colvin, Basil Zito, Jean Luszkow, and Irene Zwier, among others.

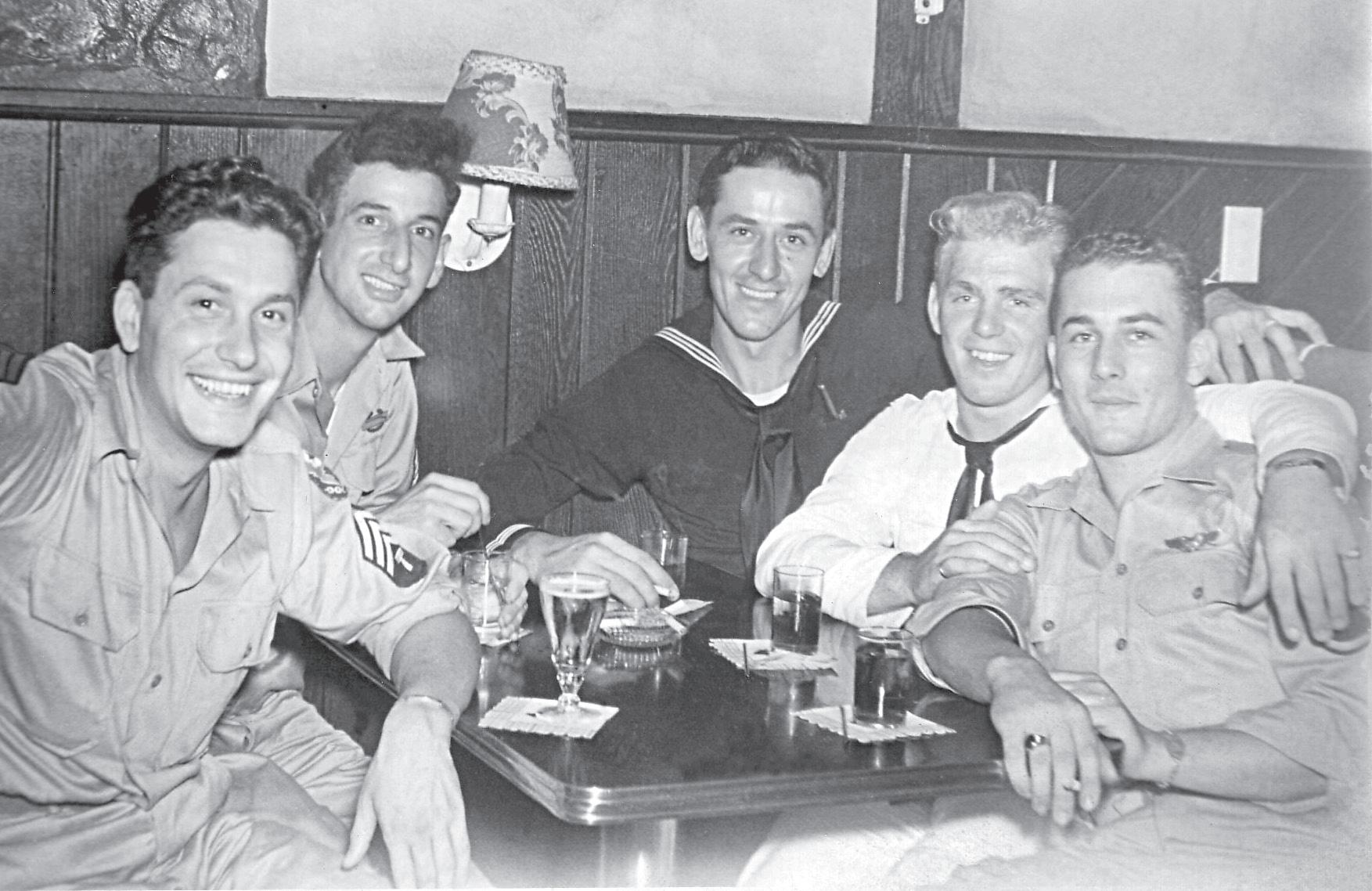

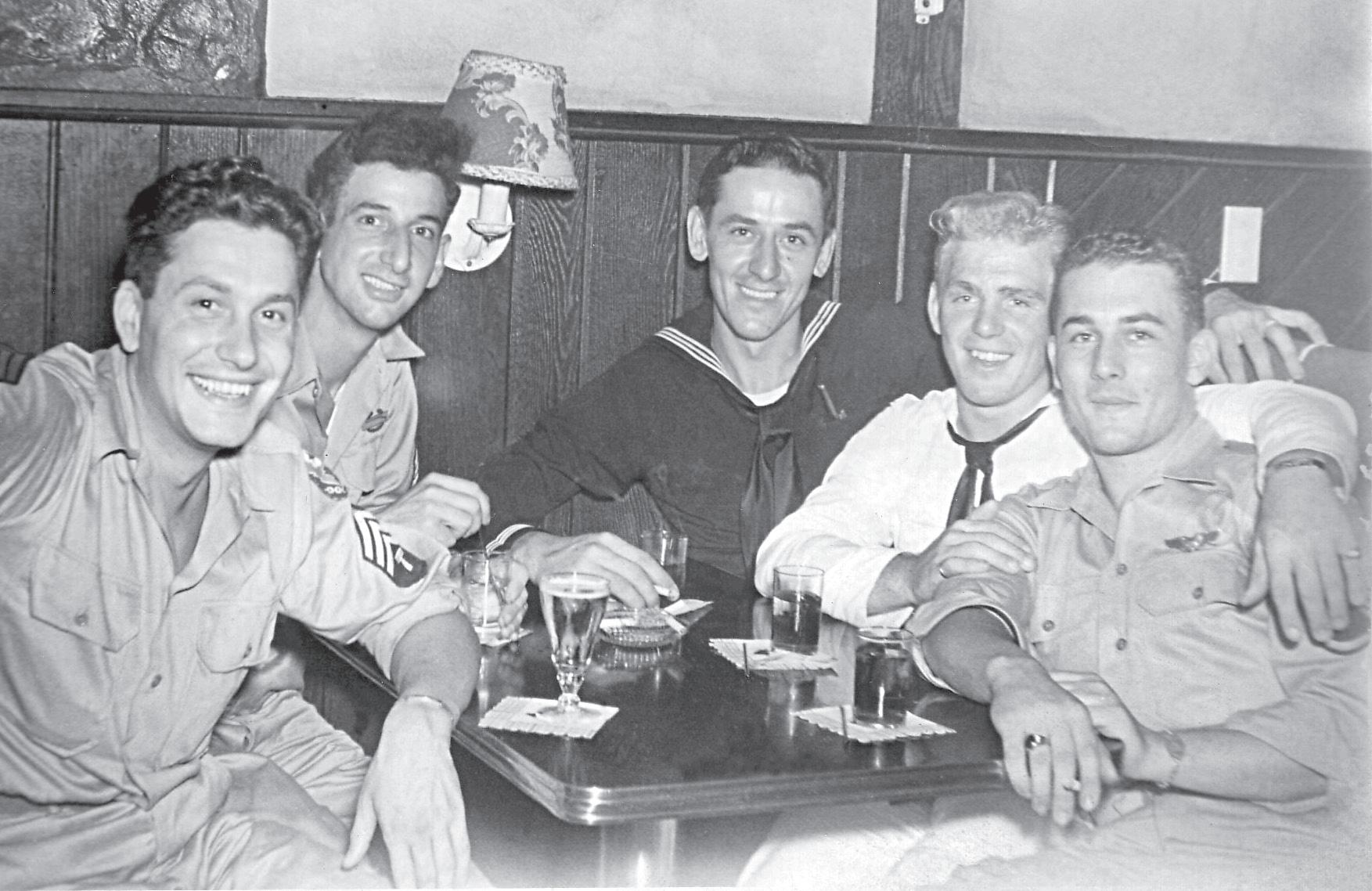

Above on furlough, relaxing in Clifton,

1944, from left Joe Menegus, Billy Bogert, Steve Kalata, Jerry Agnello, and Ed Riuli. At left, that is John Sfetz, Sgt. Walt Sudol, and Walter Hansen in the Athenia

At the Athenia Canteen, circa 1944, from left, Coast Guardsman Peter Capponi, Stanley Zwier, Navy Petty Officer Andrew Koribanics and US Army Cpl. Salvatore Griffo. Each visiting serviceman received a carton of cigarettes. Smoke ‘em if you got ‘em!

28 May 2024 • Cliftonmagazine.com

circa

Canteen.

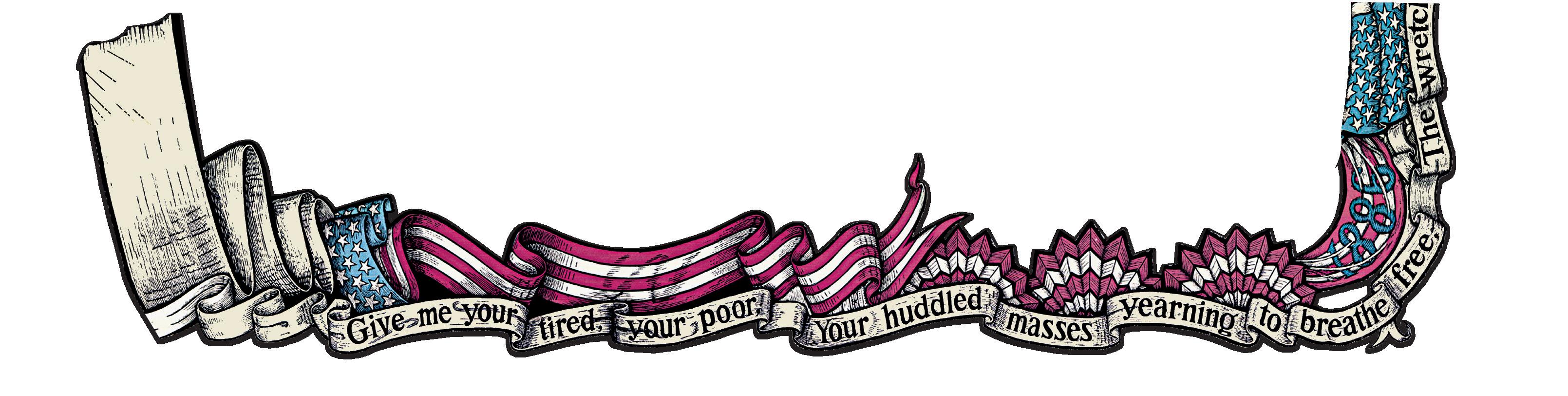

The sale of $760,000 in war bonds in Clifton through the Buy a Bomber campaign helped raise funds and essentially build the Spirit of Clifton, a B-17 Flying Fortress.

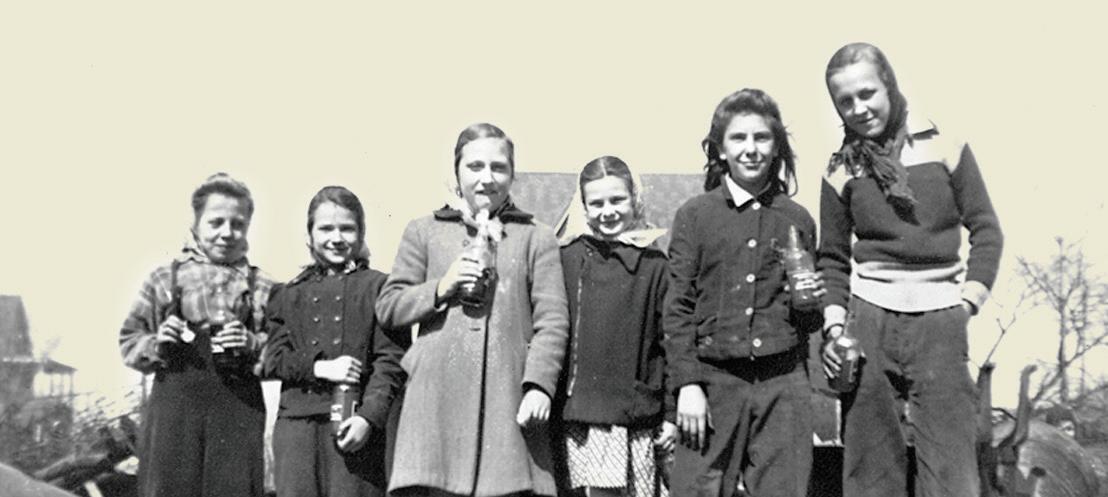

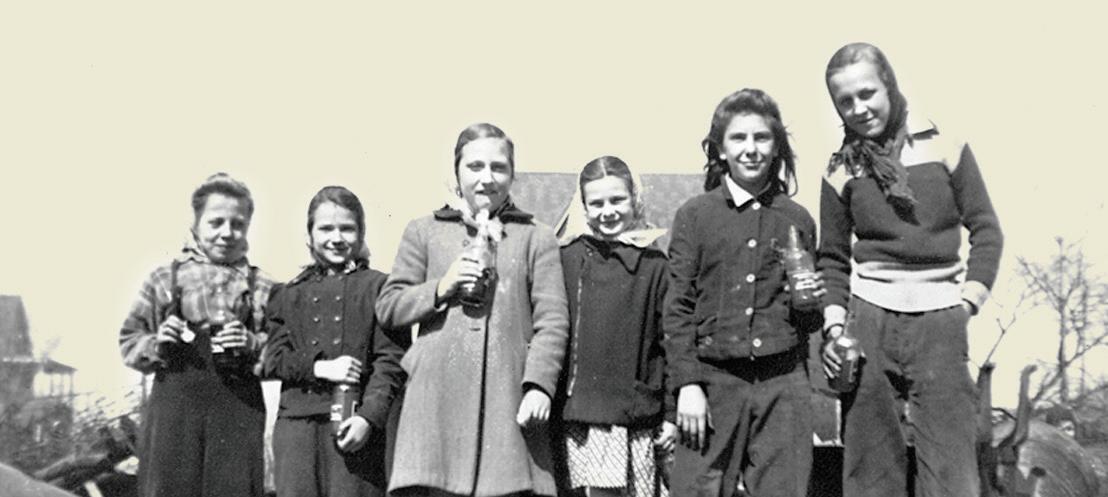

Residents recycled metals, glass and paper to help the war effort, as these kids from Athenia did.

Cliftonmagazine.com • May 2024 29

Cipriano “Chip” Zaczagnini and his father were at their Botany home when news of the sneak attack came over the radio. “As soon as I heard the Japenese hit Pearl Harbor,” Zaczagnini remembers, “I said to myself that I was going to join the Navy.”

In 1941, Zaczagnini was working in the Botany Mills. He remembers the mood in Clifton. “There was a lot of anger because they had bombed Pearl Harbor out of a clear blue sky,” he says. “A lot of men lost their lives that day.”

Including civilians, the Japanese killed 2,403 Americans at Pearl Harbor and wounded 1,178. Eighteen U.S. Navy ships were sunk or damaged. The Japanese lost 185 men in the attack, along with 29 planes, five midget submarines, and one large sub.

Three weeks later, Zaczagnini tried to enlist.

“I took the papers home to my father for him to sign, since I was only 17,” he says. “But my father wouldn’t. He served in the Italian Army in World War I and didn’t want his son going off to war like he did. My mother had passed away a few years before, and it was only the two of us. A few months later, I turned 18 and was drafted into the Army.”

After basic training, ‘we left New York and convoyed to England,” Zaczagnini says. “I was part of the 66th Infantry Division. On Christmas Eve 1944, we were boarding a troop transport, a Belgium ship called the Leopoldville to go to France to fight in the Battle of the Bulge.

“Just before we left, my Company commander, Captain Cain, told me to go with the LST (a ship used to transport ground equipment like tanks and trucks). I was a machine gunner, and there was a jeep on the LST with a machine gun on it.”

As Zaczagnini sped toward France aboard the LST, the Leopoldville was attacked in the English Channel. The ship was torpedoed by a German sub, struck in the spot where Zaczagnini’s company was riding. Cain and 800 other men died as the Leopoldville sunk, and Zaczagnini would have joined them had he not been sent to ride on the LST.

When the 66th reached France, a switch was made because of the heavy losses caused by the Leopoldville’s sinking. “Being our Division was so screwed up, they sent us to the ‘Forgotten Front’ and sent the 94th Infantry to the Bulge.” The Forgotten Front was a pocket area around the French towns of St. Nazaire and Lorient.

Trapped in the area were over 30,000 German troops – with the sea at their backs and Allied troops in front of them. Zaczagnini spent the rest of WW II fighting the Nazis and was awarded the Bronze Star for his actions.

“Everybody’s scared in combat,” Zaczagnini says. “What you see in battle is no joke. You know what they say, ‘war is hell.’ And that’s the right word, it is hell. I lost a good part of my friends there, either in battle or on patrol. The Germans had those big guns, the ‘88s.’ If you heard them, you were safe, when you didn’t hear them, that’s when you had to worry.”

30 May 2024 • Cliftonmagazine.com

Chip Zaczagnini and William Niader.

Cliftonmagazine.com • May 2024 31

William Niader’s story of WWII heroism is ingrained in his younger brother Frank’s memory.

On Dec. 7, 1941, the Niader family was living in a Hickory Hill, Pa., a rural coal-mining town. “My parents were Ukrainian,” said Frank Niader, then age 7, “and they understood what war was, what terror was. They were fearful. My brother, sister, and I didn’t understand. We felt isolated—a world away from Pearl Harbor.”

After Niader’s 42-year-old father contracted “miner’s lung,” the Niaders moved to Clifton in October 1942 to live closer to family.

Brother William became a welder for the Trowbridge Company near Mt. Prospect and Van Houten Avenues. He wanted to join the Marines, but his parents wouldn’t let him. At 18, he tried to enlist, but was rejected because the welding had affected his eyes. A few months later, his eyesight improved and William became a Marine.

on a hill overlooking the East China Sea. His research has assisted writer Stephen Ambrose, author of Band of Brothers and many other military books.

“I am incredibly proud of my brother,” Frank said.

Mario Giunta heard the news of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on the dance floor.

“I lived in Passaic then and was 18,” the former Clifton Police detective says. “A group of us would chip in a nickel for gas from the Merit station in Passaic and go to the Meadowbrook on Sundays – for $1.25, you got a lettuce, tomato, and cold cut sandwich, and dancing from noon to four.

“They stopped the music and announced the Japanese had just bombed Pearl Harbor. Then the music started again. What happened didn’t really sink in until we were riding home and talking about it.”

Frank Niader said that late in the war, his brother was fighting with the 7th Regiment of the First Marine Division, trying to capture a hill on the island of Okinawa called Kunishi Ridge. On June 12, 1945, while attempting to rescue a wounded Marine, a mortar shell struck William. He died without ever regaining consciousness.

“Two days before the war officially ended,” said Frank Niader, “we got the news. I was around the corner on Orono St., playing with my friends. My Aunt Annie came for me and said, “You better go home. Your brother’s been killed.

“What happened next was like a dream. I remember going home and seeing my parents crying, but I can’t recall much more than that – it’s like I blocked it out.”

Since then, Frank Niader has done everything he can to remember. He’s contacted 40 Marines who fought at Kunishi Ridge, learning about the days leading up to William’s death and the memorial service the Marines held for him

Three days later, Giunta and his friends went to New York to join the Marines as a group. Giunta was accepted, but his friends failed their physicals. Next, they tried the Navy. Again, Giunta passed, but his friends were rejected.

“Finally,” he said, “we got to the Coast Guard, and I said this was it for me. I passed, and they failed, so I joined. They later got drafted in the Army and got jobs like radiomen where things like bad eyesight wouldn’t affect them.”

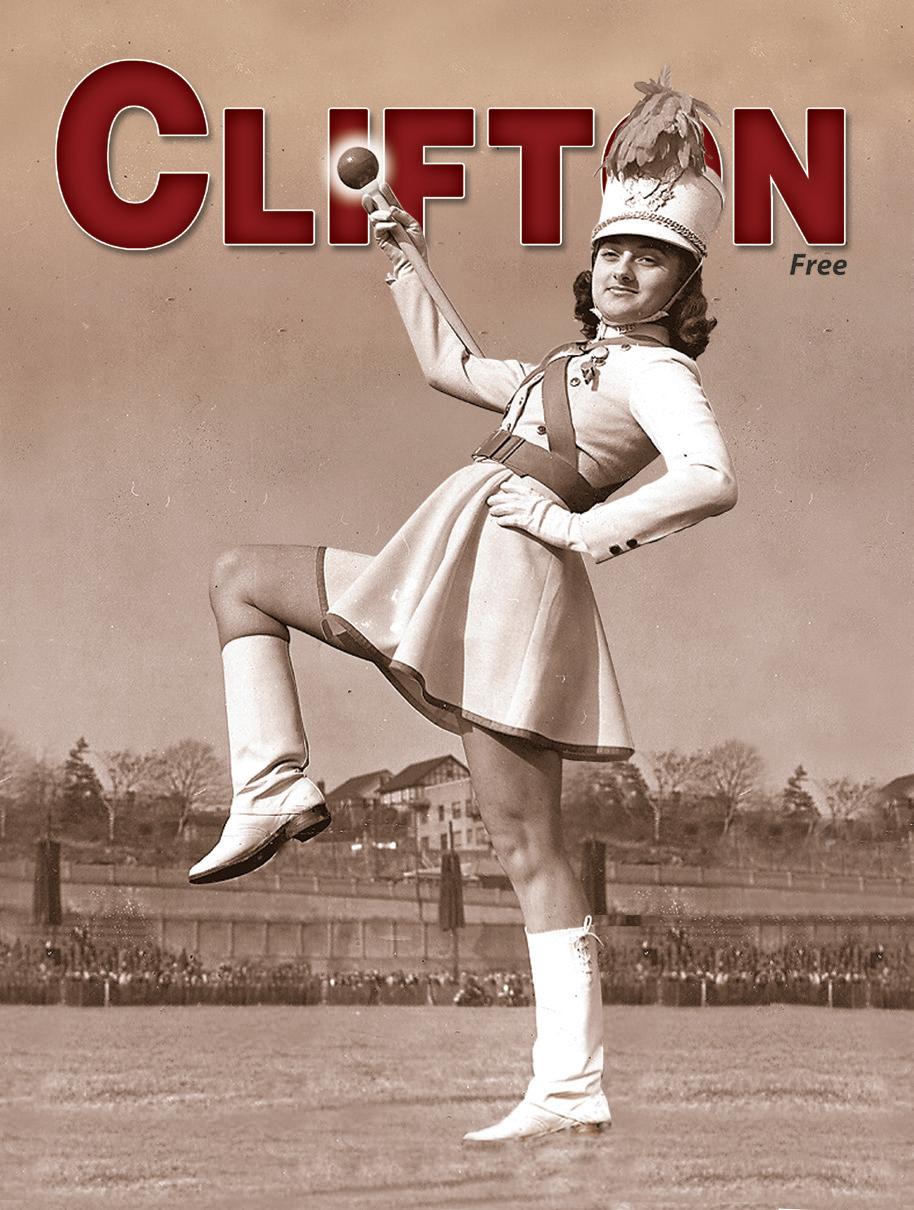

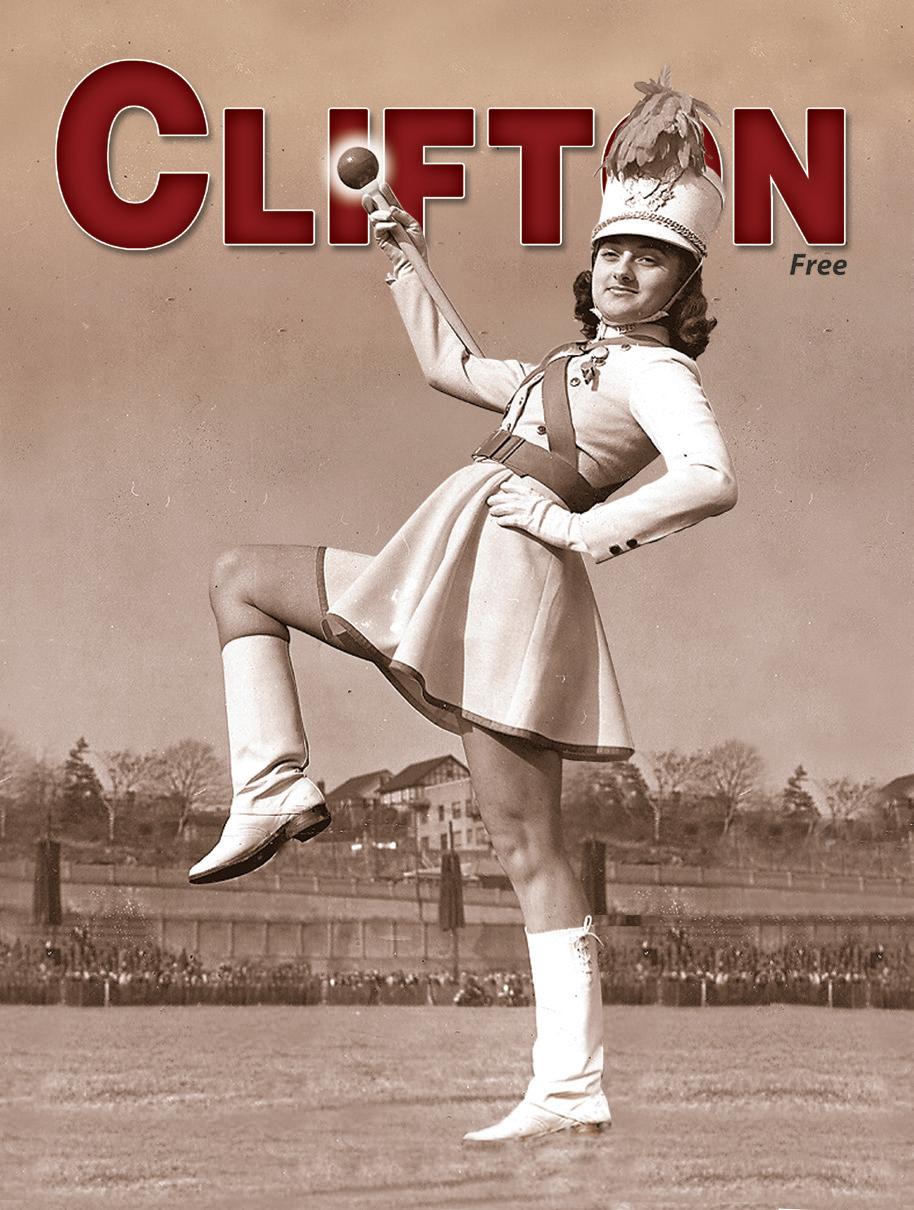

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor also changed the life of Clifton High’s former head drum majorette and Mario’s future wife, Marie (Vullo) Giunta.

“I was home when I heard the announcement,” said Giunta. “My mother, aunt, and father all had tears in their eyes. I said, ‘What’s all the crying about?’ My mother said, ‘You don’t understand about war. A lot of young boys will be killed.’”

Upon graduation from Clifton High in January 1942, Marie took a job in Wright Aeronautical in Pater-

Clifton Merchant Magazine • Volume 11 • Issue 8 • August 4, 2006

32 May 2024 • Cliftonmagazine.com

The Marching Mustang’s first Drum Majorette, Marie (Vullo) Giunta, pictured here in 1938, helps us kick off another edition focused on Clifton History.

Cliftonmagazine.com • May 2024 33

son, starting first in the mail room, them moving to secretarial work.

“I worked six, sometimes seven days a week,” Marie remembered. “They encouraged us to work as much as we could.”

Working in a room with rows of typewriters, it was her job to transcribe the notes of engineers testing airplane engines. “I wouldn’t type the swear words,” said Marie. “I was afraid they would get in trouble. An engineer named Doc Graninger told me, ‘Type what I tell you. Put in all the swear words. We need them to tell what’s happening.’ And he was right. They’d use a term like ‘goose’ the engine, which sounded funny to me, but meant something to them.”

was outside, even involved in a game of ball with friends, and he saw one of the neighborhood women carrying groceries, Frank would stop and carry the bags. His family knew he was always thinking about others. Often, when he found his mother down on her knees scrubbing the floor, he would help her up and say, “Mama, I’ll do that. You rest.”

His obituary in the Herald-News said he played football, baseball and basketball for CHS; another article said he was “a star pitcher on the baseball team.”

Marie also noted the spirit of the time. “Flags were always flying,” she described. “No matter what you did, you asked yourself if it was helping the boys.”

Her contribution to America’s war effort did not end with her day job. On Friday, Saturday, and Sunday nights, Marie helped lift spirits by singing with the Duke Collins Band as vocalist “Mary Miles,” performing at places like President’s Hall, the Polish Home, and the Passaic Armory.

“On stage,” she remembered, “I’d look out and all I could see was uniforms. Hundreds of soldiers would be there.”

The war impacted Marie’s personal life. Though she was in love with future husband Mario, whom she’d known since age 14, her family would not permit the couple to marry or become engaged. She waited while Mario patrolled the North Atlantic with the Coast Guard until the fighting ended.

“Some girls got married right away when they knew their boyfriends were going into the service,” Marie said. “My family wouldn’t allow that. They were afraid that I might become a widow, maybe with a young child.”

Clifton’s Frank Uricchio was a casualty of the battle of Iwo Jima, a young Marine whose remains were finally returned to his family 44 months after he died. Growing up, Frank was never too busy to help. If he

Uricchio would graduate from Clifton High in June 1943 and go to the University of Alabama where he played football for the Crimson Tide. While at Alabama, he took a course in aeronautical engineering. He liked it so much, Uricchio applied and was accepted to attend school at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) the following year.

Instead, he enlisted in the U.S. Navy in 1944 and went overseas that November. But naval service was not to be. His mother was petrified of submarines. Instead of the Navy, Frank switched and became a Marine.

Uricchio was 19 when he was killed on March 1, 1945, the result of wounds after being hit by shrapnel inside his foxhole. He was taken to a hospital ship, likely the USS Samaritan or Solace, where he passed away.

In Clifton, his parents James and Flora (Agnello) Uricchio of Starmond Ave. received the telegram that no military family wants to read. Beginning with the words, “The Secretary of the Navy regrets to inform you…” They learned Frank was dead.

His father, a tailor by trade who worked as a foreman in a nearby mill, knew the horror of war all too well after serving in the Italian Army during WWI. His grieving mother worried her son would never come home, fearing that he would be buried at sea since he died on the ship.

But Uricchio was indeed buried—the family believes in Guam or Hawaii. And they wanted him home.

The Uricchios filled out United States Government Form 345, a request by family members to choose a final

34 May 2024 • Cliftonmagazine.com

Frank Uricchio.

Cliftonmagazine.com • May 2024 35

burial location for military personnel killed in the war. Of 270,000 identifiable American dead, more than 120,000 families submitted the form.

In October 1948, the Navy Department notified the Uricchios their son’s grave had been disinterred, and his remains were on the way home. In late December, PFC Frank Uricchio’s casket arrived at the Marrocco funeral home in Botany Village.

He was home.

David

Eagler in 1994 and in 2019.

A memorial service and a mass was held at Sacred Heart Church on Jan. 8, 1949, after which Frank was buried at Calvary Cemetery in Paterson with full military honors.

At age 19, he was one of the youngest men from Clifton to die in the war and one of six from the city who lost their lives on Iwo Jima.

The others are Sgt. Wayne Wells of Valley Rd.; S/Sgt. Andrew Kacmarik of 907 Main Ave.; PFC Ed Hornbeck of 209 Harding Ave.; PFC Bill Hrominak of 387 Lexington Ave.; and PFC Don Freda of Mt. Prospect Ave.

While many waited for Uncle Sam to draft them, David Eagler did not. “I enlisted in November 1943,” he said. “I got my father to sign as soon as I turned 17.”

When Eagler’s training was completed in the summer of 1945, he was assigned to the USS Tyrrell, an AKA-80 cargo ship. The vessel was utilized for supporting amphibious operations by sending in Marines and supplies.

After departing on Jan. 5, 1945, from Virginia, the attack cargo ship went through the Panama Canal to Hawaii. “We made a couple runs to Pearl Harbor and then went to mop up everything in Leyte,” said Eagler.

After a few minor missions, the Tyrrell was attached to the Southern Attack Force for the Battle of Okinawa. It was the last major campaign in the Pacific Theater.

A total of about 1,300 ships – including battleships, destroyers, carriers and support vessels like the Tyrrell –

steamed toward the Japanese island. The Allies attacked with full force on April 1. “It was both Easter Sunday and April Fool’s Day,” recalled Eagler.

As the battleships and cruisers laid waste to fortified defenses with their artillery strikes, Eagler and the crew of the Tyrrell ferried over Marines and supplies. After the last of the Tyrrell’s ships hit the water, the ship remained to support the mission … nearly dooming it.

“We got hit by a Japanese suicide plane,” recalled Eagler. “We had to come back to San Francisco for repairs.”

On the second day of battle, an enemy bomber dove through the anti-air fire, heading straight for the Tyrrell’s bridge. The attack missed its main target, but hit the main radio and also damaged the starboard side of the ship.

Eagler and the rest of the ship’s crew was fortunate. Around 1,900 planes were used in Kamikaze attacks during the battle, resulting in the loss of 79 Allied ships and over 12,500 troops. The battle marked the Navy’s biggest single loss during the war.

Following repairs, the Tyrrell spent the last weeks of the war ferrying goods across the Pacific.

When word of the Japanese surrender had reached the ship on Aug. 13, the Tyrrell altered course for Saipan, and ultimately, Nagasaki.

“We were allowed on the beach and the whole town was burnt, as far as the eye can see, even the dirt. That’s how hot it was,” Eagler said. “There were kids scrounging for food, so I fed them.”

While the aftermath of the Fat Man bomb left a lasting impression on the young sailor, Eagler said that the condition of the American POWs was just as disturbing.

“Some American prisoners of war couldn’t even walk on board,” he recalled. “Some guys, who used to be 200 pounds, were now about 70. We had to pick them up on the side on a stretcher and lift them up.” Third Class Petty Officer David Eagler served until July 1946.

36 May 2024 • Cliftonmagazine.com

Cliftonmagazine.com • May 2024 37

Helene Lenkowec was born in Greenspring, W.Va., but moved to Clifton at age 4 when floods destroyed her family home. “My mother’s family lived in New Jersey,” she said, “so we moved up here. In fact, the home behind Mario’s Pizza was my grandmother’s home,” Lenkowec said.

She attended School 13 and two years at CHS before quitting to work and help her family. She was employed sewing collars onto men’s jackets at the Arrow clothing factory and then was an usherette at Passaic’s Central Theater. “All the big bands were there, “she recalled. “I met and had pictures signed by Frank Sinatra, Glenn Miller, Tommy Dorsey.”

After WWII started, Lenkowec left the Central Theater and worked briefly for Home Fuel Oil in Passaic. Now 19, she wanted to serve in the military. “So I went for the Coast Guard,” she said of joining the SPARs, the nickname for the United States Coast Guard (USCG) Women’s Reserve, taken from the USCG’s motto, “Semper Paratus – Always Ready.”

We met Helene Lenkowec in 1999 when she told of her service during WWII. Also pictured, from left: Joe Tuzzolino who served in Vietnam, John Biegel, who enlisted during the Korean War, WWII vet Walter Pruiksma and Randy Colandres, who served in the Persian Gulf.

Soon Lenkowec was on a train to SPARs boot camp at the Biltmore Hotel in West Palm Beach, Fla. “We were trained by Marines,” Helen said. “If anybody trained you well, they did.”

After four weeks, Lenkowec received her assignment: Washington. Lenkowec imagined she could go home to Clifton on weekends; instead, her assignment sent her to Seattle, Washington. “I kind of cried because I wanted to be close to home,” she said.

In Seattle, Lenkowec was assigned as a pharmacist’s mate, spending much of her time studying. She was sent to Columbia University in New York City during 1944 for further medical training. “I got my first class (stripe) after going to New York,” Lenkowec said.

Returning to Seattle, she was sent to the mountains. “Because I was a pharmacist’s mate, I had to go with the Coast Guard men who were in training and learn how to ski,” Lenkowec said. “I had to be there in case somebody got hurt.”

Near the end of her three year-tour, Lenkowec suffered a spinal injury and was classified as a disabled veteran upon her discharge in 1946 – a neck injury that remained her entire life.

Back home, Lenkowec decided that she wanted to graduate high school. Other Clifton vets had the same goal, so CHS offered night classes just for them. “I finished high school and got my diploma with 400 male veterans and another young lady,” Lenkowec said.

She went on to attend modeling school, completed her bachelor’s degree at the University of Miami (majoring in Russian, French and German), and earned a master’s degree in English from Montclair State Teacher’s

38 May 2024 • Cliftonmagazine.com

Cliftonmagazine.com • May 2024 39

College. She became a teacher, retiring from Memorial Junior High School in Fair Lawn after a 31-year career. Lenkowec also served as the Athenia Veterans Post adjutant (secretary) from 1954 until 2009. She died at age 98 in 2021.

The photo taken on Iwo Jima’s Mt. Suribachi showing six U.S. Marines raising the American flag remains WWII’s most iconic photo.

Getting to the mountain’s summit required strategy and sacrifice – something Clifton’s USMC 2nd Lt. George Linzenbold knew about.

After being wounded in 1944 during the Battle of Saipan – where he claimed a pair of binoculars, a katana sword, and a flag off of a Japanese soldier who nearly killed him – Linzenbold returned to action just after the U.S. captured the Marshall Islands.

Sensing the Americans’ next move would be to island hop to nearby Iwo Jima, Japan sent 22,000 troops to combat the Allies. At 9 a.m. on Feb. 19, 1945, the initial wave of over 30,000 U.S. troops hit the landing zone.

What happened next is how the legend was shaped.

Within the first five minutes, the Allies were being bombarded with mortar shells. Linzenbold would lead his men some 900 plus yards up a heavily fortified beach.

When two of his superior officers were downed by enemy fire, George took command of his company. When his tank support got lost on the beach, Linzenbold ran 700 yards back – all his runners were dead – to direct them. When he got to the first tank, he watched in horror as the lead man was shot in the head.

Linzenbold directed the vehicle himself before he was shot through the leg and neck.

While recovering, Linzenbold wrote a letter to the Clifton Canteen (today the Athenia Veterans Post), detailing his ordeal. However, others weren’t so lucky.

A staggering 8,226 U.S. troops gave their lives during the 35-day battle of Iwo Jima, while more than 20,000 Imperial troops died.

Linzenbold, who lived on Luddington Ave., with his wife Alma, where they raised their family, remains among Clifton’s most decorated veterans, earning a Purple Heart and a Silver Star. He went on to a 25-year career with the Clifton Police Department, retiring in 1977.

40 May 2024 • Cliftonmagazine.com

Above left, USMC 2nd Lt. George Linzenbold. On Aug. 30, 1945, S/Sgt. Michael Gulywasz (at right) preparing the first American flag to be raised over Japan, at Atsugi Airport, Tokyo. Also pictured: Lt. Edward Jacobs, Pvt. Franklin Tieg, Pvt. Herscel Stone.

Cliftonmagazine.com • May 2024 41

The raid began at precisely 7 am on a steamy Philippines’ morning in February 1945. A little more than two hours later, after a daring but perfectly coordinated attack, the soldiers, paratroopers, and amphibious units of the US Army’s 11th Airborne Division liberated more than 2,100 civilian prisoners of war from a Japanese POW camp in the jungle village of Los Banos.

Among the many heroes engaged in the fighting was Private Michael Gulywasz, a paratrooper from Clifton. Approaching the heavily fortified prison camp as part of the advanced scouting team, Gulywasz, no stranger to combat, was ready for what lay ahead.

A member of the 11th Airborne Division’s reconnaissance platoon since volunteering for the unit in 1943, he had fought in major clashes throughout the Philippines,

including the pivotal battle for Manila. Just three weeks prior to the Los Banos raid, Gulywasz volunteered to join a vitally important nighttime reconnaissance mission operating behind enemy lines.

Despite drawing heavy fire while on recon, he and his unit were able to come away with information that proved invaluable to defeating Japanese forces in a major battle at Luzon in the days following.

But even with their extensive experience as combat veterans, Gulywasz and the troops of the 11th Airborne Division approached this raid on Los Banos with extreme caution. They knew that execution would not be easy since the prison was located some 25 miles inside Japanese-held territory. In addition, there were thousands of Japanese forces within a short march of the camp, and the 11th Division’s

42 May 2024 • Cliftonmagazine.com

Wilma Jean and Mike Gulywasz.

commanders had limited knowledge of the conditions of the civilian prisoners they were being sent to liberate. Nevertheless, the invasion worked to perfection. In brief but fierce handto-hand skirmishes, the Japanese guards were either killed or sent fleeing, and the prison internees were rounded up and quickly evacuated before Japanese reinforcements could respond. All 2,122 internees were rescued and moved behind U.S. lines and not a single soldier in the raiding force was lost.

After the liberation, Gulywasz was awarded a Silver Star for his valor at Los Banos, and a second Silver Star for bravery while participating in the reconnaissance mission just before the Battle of Luzon. His unit also was honored, receiving two separate presidential citations for valor.

When the war ended, Gulywasz returned to Clifton and his young wife, Wilma Jean, whom he married while on a three-day pass just before he

shipped out overseas. The two raised a family of three children in Clifton, and Gulywasz supported them working at companies Dumont Television and Curtis-Wright. In 1994, Gulywasz was presented with Philippine Liberation Medal by the Philippine ambassador to the United Nations.

Clifton’s Van Dillen family served in the military, from Europe to the South Pacific, as well as on the home front, for three generations.

Sgt. David C. Van Dillen, who spent 16 months in France during WWI, was first. When America entered WWII, Van Dillen was part of Clifton’s Civil Defense Council, teaching citizens to conduct dimouts, air raid drills, bomb precautions and security. He also purchased war bonds, gave blood, made bandages, and recycled metal.

In his prayers were sons, David L. and Roger Van Dillen, among the more than 5,500 Cliftonites

Cliftonmagazine.com • May 2024 43

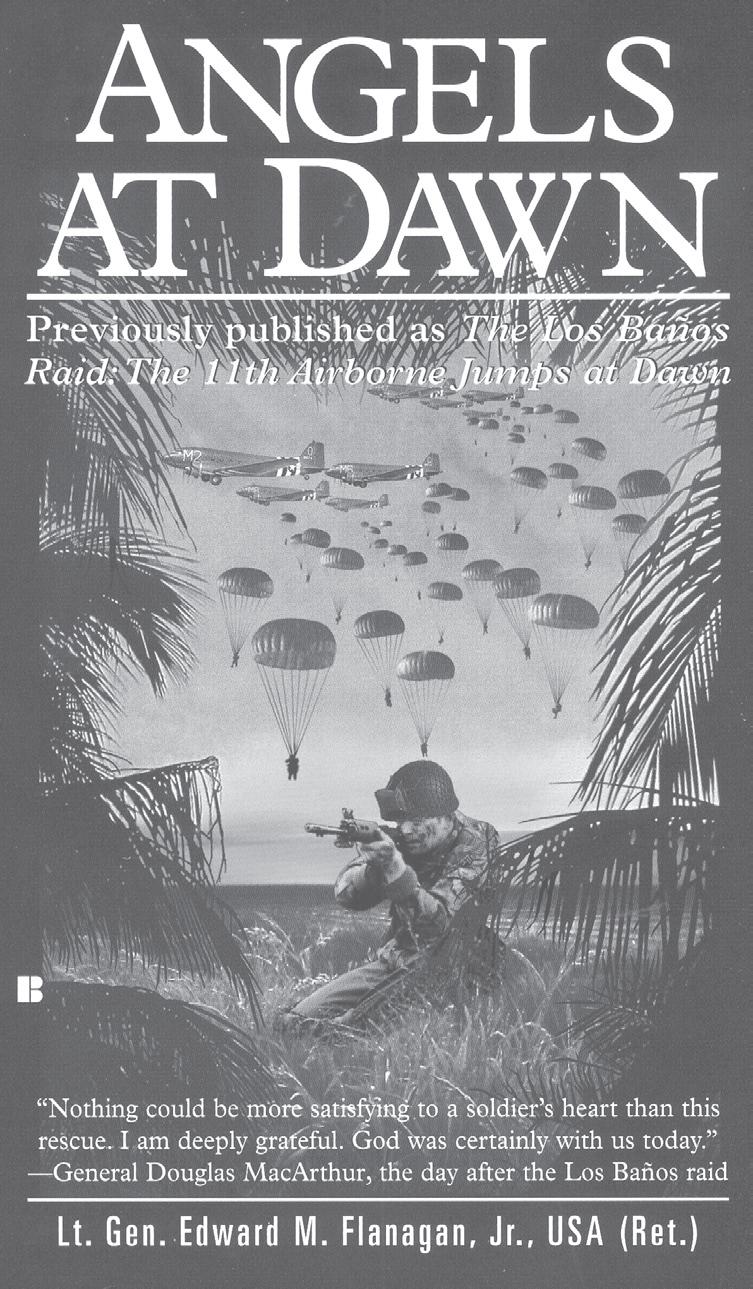

The story of the 11th Airborne Division’s liberation of the Los Banos POW camp is chronicled in the book, Angels At Dawn, by Lt. General Edward M. Flanagan, Jr.

serving in the armed forces during World War II.

Son David L., Clifton’s former historian who died in 1998, worked at Wright Aeronautical Corp before serving for four years in the Army Air Corps as a weather forecaster, using his meteorological training to locate hurricanes. His brother Roger served in the Navy and was stationed in the South Pacific.

David C. Van Dillen and Dorothy Den Herder. At right Dorothy and George in 2004.

Inspired by his grandfather and father and uncle’s service, Paul Van Dillen (son of David L.) served in Vietnam and later in the Peace Corps in the Dominican Republic.

Dorothy Den Herder’s life changed when she became an army nurse at WWII’s start. During the next three years, she treated thousands of soldiers and helped save hundreds of lives in Italy and North Africa. She also got to eat lunch with a movie star, shake hands with the Pope, and fall in love with the man she’d marry – George Den Herder, a driver for the commander of the 37th Hospital Group.

The two met in Camp Landing Fla. “I noticed immediately how handsome he was,” Dorothy said. Commented George: “As soon as I saw her, I sensed to myself that this was the girl I’m going to marry.”

Their unit shipped out to Tunisia and, during the sea voyage, George and Dorothy got to know each other. As a nurse, Dorothy dined in the officers’ mess where the food was better. She’d make sure to get extra food for the enlisted men, especially George.

They spent the next year-and-a-half serving in North Africa where Dorothy treated the wounded from General George Patton’s army during the invasion of Sicily. They moved on to Naples in late 1943.

In Italy, Dorothy escorted actress Marlene Dietrich who visited wounded allied soldiers and later met Pope Pius XII. “The Pope was very generous,” said Dorothy, a Lutheran. “As he clasped my hand, I asked him to bless several of my friends, and he graciously assured me that he would.”

George was shipped to a combat unit in northern Italy where he was seriously wounded in a building collapse, destroyed when an army officer pried open a boobytrapped safe.

George was dug from beneath the rubble by German prisoners captured by the Allied Forces.

When Dorothy learned of George’s injuries, she commandeered an army vehicle and immediately drove to see him. George recovered and returned the favor shortly after, going AWOL to see Dorothy during Christmas 1944. He recalled the reaction of the officer who caught him going AWOL. “After seeing Dorothy, he told me that if he had known how beautiful she was, he’d have given me a furlough to see her,” George laughed.

When the war ended, George and Dorothy reunited in Brooklyn and were married there in November 1945. They moved to Clifton, where George, whose family emigrated from Holland in 1929, had relatives. They built a house in Delawanna where they raised their son, George, and daughter, Doris.

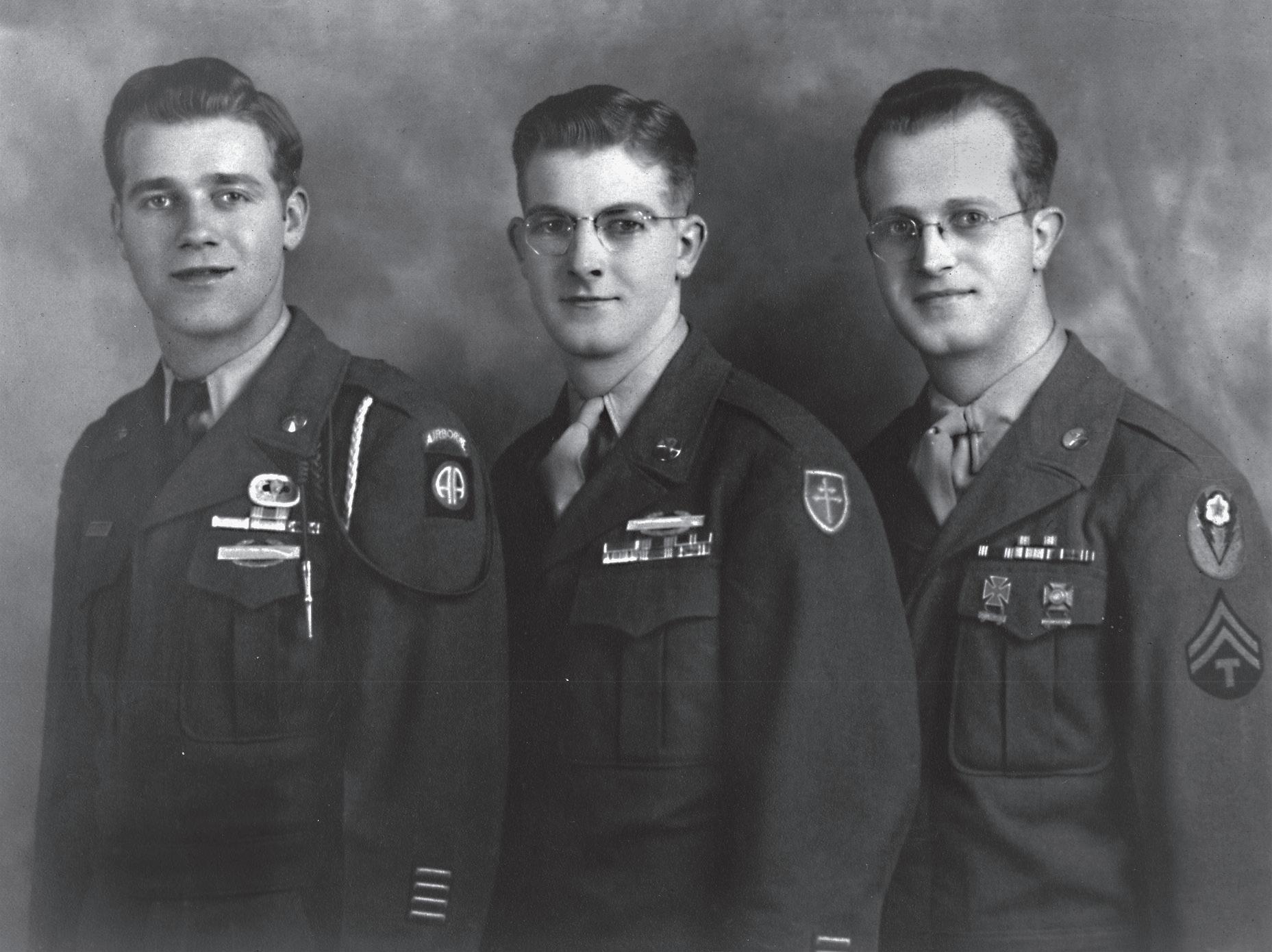

In 1942, Mr. and Mrs. Matthew Breure Sr. of Dutch Hill had three of their sons – Adrian, Cornelius and Matthew Jr. – drafted into the Army, drawing separate assignments in the European Theater.

The family (which included older brothers Teddy and Bill, and sister Minnie) came to the U.S. from Holland 14 years earlier, settling at 40 Helen Pl. A sixth brother, Leonard, was born six months later.

44 May 2024 • Cliftonmagazine.com

Adrian served 18 months as an administrative clerk with the 170th Hospital Train, evacuating wounded soldiers. While on detached service with the 106th Division, he participated in the Battle of the Bulge.

Cornelius, nicknamed “Casey,” served 18 months in the European Theater with the 79th Infantry Division in Northern France, the Rhineland and Central Germany.

Finally, Matthew was a paratrooper with the 82nd Airborne Division and served in the Mediterranean and European Theaters for two-and-ahalf years. With the First Airborne Task Force, he took part in campaigns in Sicily, Southern France, Belgium, Luxembourg and Germany.

The Breure brothers also returned to the land of their birth at different points during the war. “The dykes were busted by the Germans,” Casey recalled of his return to Holland. “My cousins were flooded out of their homes and farms.”

While on duty, there was no way for the brothers to keep tabs on each other. Back home, news about the Breure brothers was not much easier to come by, according to Casey’s wife Ann (Van Beveren). She recalled loved ones occasionally received “V-mail” – short, censored, printed letters from soldiers serving abroad.

Thankfully, the Breure brothers made it back home within weeks of each other in December 1945. The most serious injury suffered was Casey catching shrapnel in his neck, the result of mortar fire that struck a tree.

Casey earned the Bronze Star, Purple Heart, Combat Infantryman’s Badge, European Theater of Operations (ETO) Ribbon with three battle stars, the Victory Medal

Cliftonmagazine.com • May 2024 45

Three of the Breure brothers served simultaneously during World War II, from left, Matthew, Cornelius and Adrian.

46 May 2024 • Cliftonmagazine.com

Cliftonmagazine.com • May 2024 47

and the American Theater Ribbon. In 2000, he received a Distinguished Service Medal from the State of New Jersey. Matthew sustained a bad case of frostbite on his feet while serving overseas, but recovered. He earned the Presidential Citation and the Braid of the Dutch Willems decoration and the Belgian honors awarded to his division, as well as the Purple Heart and the European and American Theater ribbons.

Adrian won three battle stars, as well as the Victory Medal and the American Theater Ribbon.

During the war, the Breure parents moved in with Teddy, their oldest son, at his home on Trenton Ave. The Breure brothers return was featured in the Jan. 14, 1946 edition of the Herald News, showing the three veterans in uniform, admiring Leonard’s model airplanes.

After the war, Matthew opened the Breure Sheet Metal

Co. on Walman Ave.; Adrian worked as an accountant and was longtime president of VFW Post 142 on Piaget Ave.; and Casey became a carpenter. Leonard served his country during the Korean War.

During a 22-year career in the armed forces, Ed Noll served in the U.S. Navy during WWII and the US Army during the Korean War. But he got his indoctrination to military training as a member of “Roosevelt’s Tree Army” – more formally known as the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC).

Established by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in March 1933, the CCC put millions of unemployed men, ages 17-25, to work during the Great Depression. Members of the CCC worked fighting dust storms, restocking streams, preserving forests and wildlife and building

UKRAINIAN NATIONAL ASSOCIATION, INC. 2200 ROUTE 10, PARSIPPANY, NJ 07054 ● 800-253-9862 ● INFO@UNAINC ORG ● WWW UNAINC ORG STAND WITH UKRAINE 2ND YEAR * 2ND YEAR * * ! * FIRST YEAR RATE. MINIMUM GUARANTEED RATE 2%. RATES SUBJECT TO CHANGE. NOT AVAILABLE IN ALL STATES. EFFECTIVE 04/03/2023 48 May 2024 • Cliftonmagazine.com

roads, bridges and dams. They even contributed to the early WWII defense effort.

Camps were in every state, as well as in Hawaii, Alaska, Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands. There were more than 2,650 camps in operation.

As a 17-year-old boy living in Passaic Park, Noll read about the CCC in a newspaper and visited a recruiting office. His parents approved and he was soon on a bus to Fort Dix along with the other recruits. “I would now live a military lifestyle,” Noll recalled.

He was assigned to Company 257, just outside the town of Bovill, Idaho. “I was in a forestry company,” he said. “We snagged lumber; in the forest they had a lot of dead trees fall or falling, and we cleaned up the area. If there was a forest fire, we fought it, then cleaned up after that and planted white pine trees. They brought the trees in from Montana; they were seven years old. We’d form a skirmish line, seven across, and every seven feet would throw a ‘pickmatic’ (a trench-digging tool) into the ground and plant a tree.”

In 1941 after Noll completed a year in the CCC, he was honorably discharged and sent home. By that time, Hitler was moving through Europe, and Noll’s father suggested it would be better for his son to enlist than be drafted. Noll enlisted in the Navy, where he served in the Aleutian Islands, the Asiatic Pacific and Korea.

When his four-year hitch ended in 1945, he returned home to take a job in a foundry. But Noll missed military life. Thus began his 14-year stint in the Army, during which he met Soonie, who became his wife in 1958 while they were in Korea.

When the Nolls returned stateside, Soonie lived with Ed’s mother on Arthur St. in Lakeview. He subsequently was stationed in Germany, Iran and in the U.S. before he

retired as a sergeant in 1963.

Ed and Soonie bought a house on Gould St. where they raised five children: Victor, Robert, Peter, Maria and Okhui. Taking a job in security for Bendix Corporation in Teterboro, N.J., Ed worked another 20 years before retiring. Soonie owned and operated Eosin Panther on Main Ave., manufacturing martial arts uniforms.

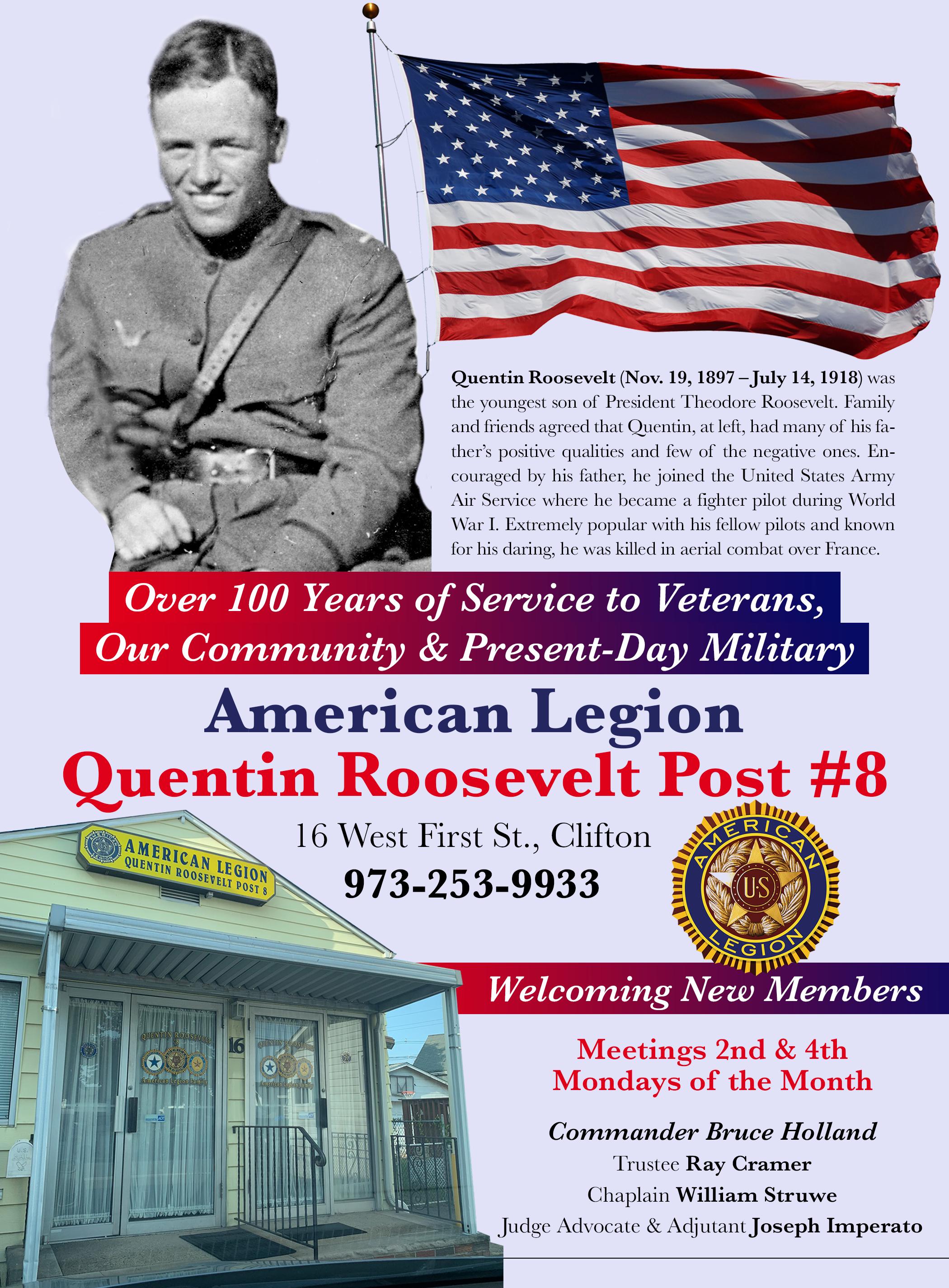

When Jack Kuepfer – a Clifton resident for more than five decades and member of the Allwood Veterans Post and the Quentin Roosevelt American Legion Post 8 –learned the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, he got angry and wanted revenge.

“The next day,” he said, “I went down to a recruiting station in Paterson and joined the Army Air Force. I wanted to be a pilot. I couldn’t wait to get in and start serving my country by killing the enemy.”

However, instead of pilot training, Kuepfer remained on the ground, moving to air mechanics school near Biloxi, Mississippi. That detour took Kuepfer to Europe instead of the Pacific.

On June 4, 1942, Kuepfer, then attached to the 307th Fighter Squadron of the 31st Fighter Group, was shipped to England aboard the Queen Elizabeth with

Cliftonmagazine.com • May 2024 49

Ed Noll served in the Civilian Conservation Corps, the US Navy and US Army.

15,000 troops – the first Americans to go into combat in the European theater.

“Our planes took part in the Dieppe raid in August 1942,” he said. “I was a ground crew mechanic. We were using the British Spitfires, the best fighter plane there was at that time.”

In October 1942, Kuepfer boarded a ship for North Africa for what turned out to be a miserable trip. He was seasick for 14 days.

“We landed in Oran, North Africa, and started to work our way eastward,” he remembered. “Sometimes we were only five miles from the Germans. The Spitfire didn’t have long range.”

Suddenly, the Germans went on the offensive – pushing the Americans back and were a lot closer than five miles away. On Valentine’s Day 1943, a Messerschmitt fighter plane dove out of the sun, strafing his airfield.

“The Messerschmitt had this peculiar roar,” Kuepfer said. “There was no mistaking it. My buddy and I ran across the field and jumped in a ditch. You’re so scared, you start crying.”

After the Allies won the North Africa campaign in 1943, Kuepfer found himself on an invasion force again, this time bound for Sicily.

“Sicily was beautiful. We had nice duty, right along the beach,” he said. “The Germans never came around there to bother us. After our planes went on their mission, we would go swimming. We ate beautiful ripe grapes, and this was the first time I ever ate a fig from a tree. This is what you remember.”

Kuepfer finished up his service in Italy, farther from the front since the Army was now using the Americanmade P-51 Mustangs, which had a much longer range then the Spitfires.

He remembered the day in March 1945 when he found out he was going home: “They had started the rotation back home that winter, using the point system. Those who had accumulated enough points would have their names put into a hat and then a name would be drawn. I asked the flight leader that day whose name had been pulled, and he said, ‘You.’

“I said, ‘We don’t have a Hugh in the outfit.’

“He shouted at me, ‘No, not Hugh. You! You fool! You’re going home!’”

Kuepfer was employed at Sheet Metal Products in Newark for 35 years. After retiring, he founded the Morris Canal Park in Clifton, devoting much of his labor and know-how over the past 30 years. The park was later renamed for him in his honor. He died in 2014 at the age of 94, still enjoying his work at the Morris Canal Park.

50 May 2024 • Cliftonmagazine.com

Jack Kuepfer during WWII and in 2007.