A PEER-REVIEWED FORUM FOR NURSE PRACTITIONERS

NEWSLINE

■■ Substituting MDs With APPs in Nursing Homes ■■ Hawaii Repeals Physician Chart Reviews for PAs LEGAL ADVISOR

Medical Errors and Negligence

|

SEPTEMBER 2019

| www.ClinicalAdvisor.com

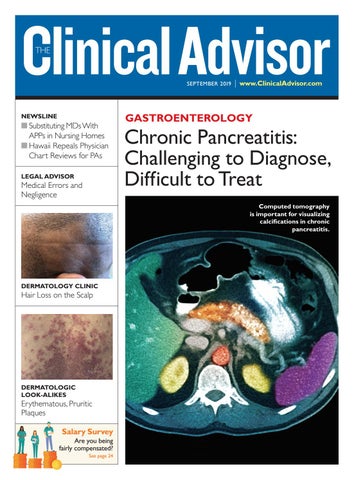

GASTROENTEROLOGY

Chronic Pancreatitis: Challenging to Diagnose, Difficult to Treat Computed tomography is important for visualizing calcifications in chronic pancreatitis.

DERMATOLOGY CLINIC

Hair Loss on the Scalp

DERMATOLOGIC LOOK-ALIKES

Erythematous, Pruritic Plaques Salary Survey Are you being fairly compensated? See page 24