THE CLINICAL ADVISOR • NOVEMBER 2013

A F O RU M F O R N U R S E P R AC T I T I O N E R S

NEWSLINE

■■Hormones and CV risk ■■Sleep apnea guideline ■■BP screening in children

ADVISOR FORUM

■■Smoking and low libido ■■Hepatits C: When to refer ■■Classifying dysplastic nevi

| N OV E M B E R 2 013 | www.ClinicalAdvisor.com

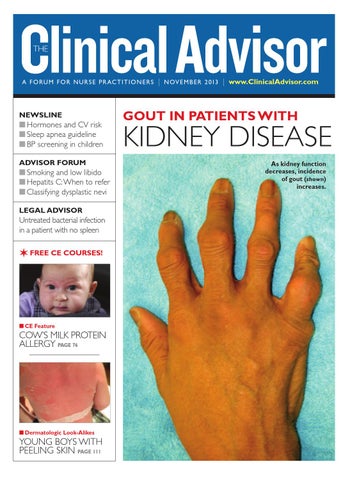

GOUT IN PATIENTS WITH

KIDNEY DISEASE As kidney function decreases, incidence of gout (shown) increases.

LEGAL ADVISOR

Untreated bacterial infection in a patient with no spleen

✶ FREE CE COURSES!

n CE Feature

COW’S MILK PROTEIN ALLERGY PAGE 76

VOLUME 16, NUMBER 11

n Dermatologic Look-Alikes

YOUNG BOYS WITH PEELING SKIN PAGE 111

CA1113_Cover.indd 1

10/30/13 1:58 PM