9 minute read

Women’s Motor Corps of America Coat, 1917–1920, by Marc W. Sammis

Women’s Motor Corps of America Coat, 1917–1920

Marc W. Sammis

Advertisement

The Women’s Motor Corps of America was established between November 1917 and January 1918 as a volunteer organization of women drivers and mechanics. They first had to register with National League for Women’s Service (FIG 1), which was created in January 1917 just prior to the U.S. declaration of war against Germany in April. The organization prepared women for service and was divided into home economics, motor corps, social and welfare divisions, agriculture department, the canteen division, general services and publicity departments, and the overseas relief division.1 The women who joined these organizations were, for the most part, from the upper social classes and felt this as part of their “noblesse oblige” or noble obligation to the war effort. Most were centered in the larger metropolitan areas such as Boston, Chicago, Detroit, New York, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, St. Louis, and other cities. Journal of the Company of Military Historians

FIG 1. Staff of the National League for Women’s Service, Motor Corps. Brooklyn Division, circa 1918. Courtesy of the Brooklyn Public Library, Brooklyn, NY.

The Women’s Motor Corps of America was one of many offshoots of the National League for Women’s Service and was one of the most demanding in terms of applicants. It was also the most militaristic in terms of regimentation. Requirements were: hold a state chauffer’s (driver’s) license and a mechanician’s (mechanic’s) license from an accredited mechanic’s school; take the oath of allegiance; pass a medical examination conducted by an Army doctor; receive a typhoid inoculation; and most importantly, own a car. They then underwent military training for one week to two weeks, which included infantry (close order) drill, practiced marksmanship, attended first aid, stretcher bearing, driving, and mechanics classes to name a few (FIG 2). They would then have weekly classes in those subjects during their term of enlistment. They would pass in review at the end of their training2 (FIG 3). The women were expected to not only drive but also maintain their own or assigned vehicles.

Organized into chapters, their purpose was for emergency needs and they worked closely with area hospitals in the United States. Private automobiles were required as the chapters had to wait until ambulances and other trucks were either bought or donated to them (FIGs 4, 5). Their main task was to transport the injured and sick. Chapters near ports also met transports coming back from France and drove the wounded and sick to the hospital with which their particular chapter was associated. They also transported supplies and material for the hospitals and nearby camps. They were continually on call and had to report immediately when summoned. Failure to do so could result in discharge from the organization.

The Women’s Motor Corps of America was one of many women’s organizations established during World War I. The exact number of women who joined the motor corps is uncertain but the estimate is between 3,000 and 5,000 (FIG 6). While some members of the Women’s Motor Corps of America went overseas to France during the war, most did not.

FIG 2. National League for Women’s Service personnel at stretcher training, Fort Totten, NY, circa 1918. Courtesy of the Brooklyn Public Library, Brooklyn, NY. FIG 3. Women’s Motor Corps of America on parade, New York City, circa 1918. Courtesy of the Brooklyn Public Library, Brooklyn, NY.

FIG 7 FIG 9

FIG 8

FIG 4. Newly purchased ambulance for the New York Chapter with Women’s Motor Corps of America insignia stenciled onto the side, circa 1918. Courtesy of the Museum of the City of New York.

FIG 5. Ambulances of the Women’s Motor Corps of America in line formation ready for inspection, circa 1918. Courtesy of the Brooklyn Public Library, Brooklyn, NY.

FIG 6. Lincoln, NE, Chapter of the Women’s Motor Corps of America, circa 1918. Courtesy of the Lincoln, NE, Historical Society.

Different women’s organizations wore uniforms unique to their particular organization. The patterns, color, accessories, and insignia showed which organization a person belonged to. The coat in this case is from a member of the Women’s Motor Corps of America.

Women’s Motor Corps of America Coat

This uniform coat is the regulation cut and is based upon the design of a similar British organization. They were purchased by the individual who had them custom made. The coat is olive drab, long, single breasted with

FIGs 7, 8, 9. Uniform coat showing the blue tabs with embroidered insigina. Collar tabs showing the embroidered Women’s Motor Transport Corps insignia. Right sleeve showing the sergeant of Hospital Corps chevron, honorable discharge chevron, and blue felt war service chevron. All courtesy of the U.S. Army Transportation Museum, Fort Eustis, VA. a stand-and-fall collar, and notch lapels. The sleeve cuffs are pointed after the British style. There are two pleated breast patch pockets and two large pockets on the coat skirt. All four pockets have flaps with buttons. Three large buttons along the front and one at each skirt pocket. A faux waist belt is sewn over the waist seam hiding it from view. One small button at the breast pockets. All are the dull bronze U.S. Army. The collar tabs are “King’s Blue” (also called Royal Blue) felt with the winged wheel insignia of the Women’s Motor Corps of America embroidered onto it with silver thread (FIGs 7, 8). Some uniform coats had red collar tabs. The reason for the difference is not known.

The coat is of cotton, with the body unlined and machine stitched. The chevrons are all hand stitched onto the sleeve but do not penetrate into the sleeve lining. There are several holes, most probably caused by moths, less than ⅛-inch (3mm) on the collar tabs with one hole approximately ¼-inch (6mm). No holes appear on the coat body itself. There are many stains from various causes and what appears to be some foxing. Because of this, a dry vacuum was used to clean the coat rather than soap and water. A label for Franklin Simon & Company is sewn at the neck. Franklin Simon & Company was a department store chain specializing in women’s fashions and furnishings based in New York City. The store was conceived as a collection of specialty shops rather than a traditional department store and closed in 1979. While the label doesn’t mean the individual who wore this coat lived in the New York City area, it also doesn’t seem necessary for a women in another area to purchase the coat from Franklin Simon if there are equally fashionable clothiers in their respective city or area. So we may suspect the

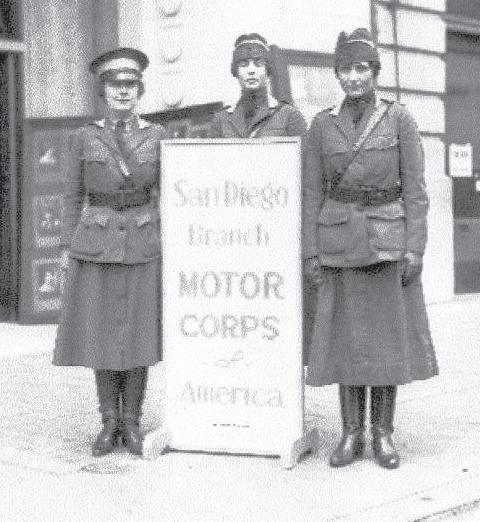

FIG 10. San Diego, CA, Chapter of the Women’s Motor Corps of America showing the various ways of wearing the Sam Browne belts, circa 1918. Courtesy of the San Diego Historical Society, San Diego, CA.

owner was from the New York City area.

Their uniform would also have consisted of a soft service cap or an overseas style cap, a waist (shirt), cravat, and a long skirt that buttoned along the middle in the front. The service cap had a band around it while cord edge braid along the edge of the curtain appears on some, but not all, of the overseas style caps. The color apparently match that of the collar tabs being either King’s Blue or red.

Rank structure and insignia were similar to the U.S. Army’s, thus the sergeant of the Hospital Corps chevron on the right sleeve. The dark blue chevron is for less than six months service. The red chevron is an honorable discharge chevron worn upside down and on the opposite sleeve per regulation3 (FIG 9).

Another interesting feature is the officers among them wore Sam Browne belts, which were unauthorized for stateside Army officers. Some wore no belts. Some belts with no straps; some had the straps over the left shoulder and some over the right shoulder (FIG 10). The author has not been able to find references for the reason for these different means of wearing the belts but looking at photographs, it appears it may have had something to do with the rank of the individual.

A complete uniform identified to Leonila Durieux Tedford is in the collection at the Women in Military Service for America, Alexandria, Virginia.4 Another uniform is in the collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City.5 It does not identify to whom the uniform may have belonged.

PITTSBURGH CHAPTER STATISTICS

Below are listed the statistics of the Pittsburgh Chapter of the Women’s Motor Corps of America during their time of service (1 December 1917–1 January 1920) as documented in their official records published in 1921.6 These totals represent service for both World War I and the influenza epidemic of 1918–1919. They give a good account of the contribution to the war effort by the Women’s Motor Corps of America and other volunteer organizations.

Served General Hospital No. 24 197—women served during all or part of the time period 3,348—articles lifted at depots totaling 489,118 pounds 389—cases shipped to auxillaries totaling 40,000 pounds 7,560—goods shipped to Division HQ in Philadelphia totaling 600,000 pounds Activities: 1 November 1918–1 November 1919 60,162—containers handled totaling 5,420,285 pounds 2,711 tons —total tonnage 3,325.5 gallons—amount of gasoline consumed 83.75 gallons—amount of oil consumed 64,292 miles—total miles driven 14,636—hours of service rendered Activities December 1919 – May 1920 18,714—containers transported by large trucks 7,165—containers transported by small trucks 25,879—total of containers carried Vehicles in use The vehicles listed below were used by the Pittsburgh chapter at no cost to the Red Cross or government. As was the case with all chapters, costs were paid by the chapter members. 7—½-ton to 2-ton trucks 43—private automobiles owned by members 200—automobiles available for use in emergencies 600—trucks available for use in emergencies

The Khaki Girls

The early twentieth century saw a great demand by the public for adventure stories. Series such as Nancy Drew, Tom Swift, the Hardy Boys, and others now long forgotten, all got their start around the time of World War I. The trend continued after the war and one of the new adventure series was “The Khaki Girls” written by Edna Brooks. The stories followed the adventures in New York and France of several women who join the Women’s Motor Corps of America. A total of six books in all were written in the early 1920s before the series ended.

Notes

1. Columbia (University) Daily Spectator, 16 July 1917, spectatorarchive.library.columbia.edu/cgi-bin/

Columbia?a=d&d=cs19179716-01.2.11, accessed 3 February 2017. 2. “The National League of Women’s Services, 1918,” Brooklyn Public

Library, 29 July 2010, brooklynology.brooklynpubliclibrary.org/ post/2010/07/09/national-league-of-women’s-services, 1918, accessed 3 February 2015. 3. Jill Halcomb Smith, Dressed for Duty, America’s Women in

Uniform, 1898–1973 (San Jose, CA: R. James Bender Publishing, 2001), I: 372–376. 4. Ibid. 5. Metropolitan Museum of Art, Online Collection, Franklin Simon & Co., www.metmuseum.org/colleciton/the-colleciton-online/ search/155838, accessed 5 January 2015. 6. The Pittsburgh Chapter, American Red Cross: A History of the

Activities of the Chapter from its Organization to January 1, 1921, with an Appendix Containing All Available Names of Those who Rendered Red Cross Service During that Period (Pittsburgh,

PA: American Red Cross, Pittsburgh Chapter, 1921), 146–152.