74 minute read

Capt. George T. Balch, U.S. Army Ordnance Department, and his 1861–1862 Letter Book, by Charles Pate

Capt. George T. Balch, U.S. Army Ordnance Department, and his 1861–1862 Letter Book

Charles Pate

Advertisement

On 2 October 1858, Sam Colt complained to the secretary of war about the “tardy” manner in which his pistols were being inspected and received by government inspectors, saying they were frequently called away to do other work and when they were at his factory they typically did not put in full days of effort.1 Although it took him a while to compile a response to this complaint, the officer in charge of the inspection, Capt. William A. Thornton, refuted the specifics of Colt’s complaint and did so in a very convincing fashion.2 Thornton’s response made it clear he had extensive records for the inspection work done under his supervision as well as that done by his predecessor in the position, Capt. Robert H. K. Whiteley. Furthermore, such records were maintained for some time, for after the Civil War then Colonel Thornton was able to provide the chief of ordnance with very specific information on inspections done during his service as “Inspector of Contract Arms” in 1864–1865. Thornton died in April 1866 and was succeeded as Inspector of Contract Arms by Maj. Julian McAllister. When in April 1867 it was no longer necessary to continue this inspection office, McAllister was told to send the inspection records to the New York Arsenal for storage.3 Unfortunately, it appears almost all of the records related to small arms inspection were subsequently lost. To the author’s knowledge, the

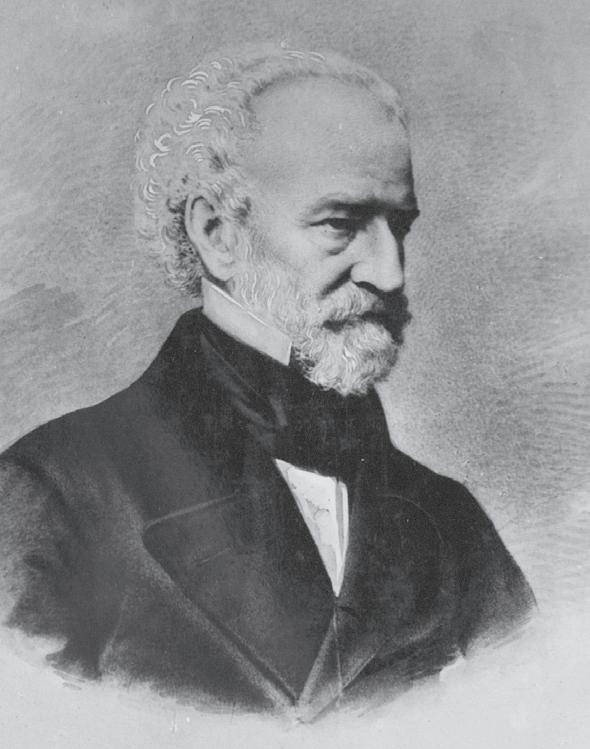

FIG 1. Capt. George T. Balch. U.S. Army photo. only records that have survived from Civil War inspecting officers of contract small arms are individual original copies of letters and reports the inspecting officers sent to Ordnance Department facilities, such as the Springfield Armory, and the chief of ordnance, and two “letter books.” One of these books was used by Whiteley in 1861–1862 and for a short time later in 1862 by Thornton. It is now in the regional branch of the National Archives in New York City. The other letter book was used by Lt./Capt. George T. Balch from 26 October 1861 to 10 March 1862. It, and Balch’s subsequent service, is the subject of this paper.4

Before continuing, it would be appropriate to define what is meant by “letter book.” In the context of this paper, a letter book was a book containing record copies of letters sent by an originator. Usually these were books containing “fair copies” of the letters but they might also be bound “press copies.” A “press copy” is a copy of a written document made in a copying press, which transfers some ink from the original to another sheet of paper, usually thin onion-skin or tissue paper. The copy is then read from the other side of the sheet. Most often these press copies are barely usable if at all and, consequently, if time and clerical resources were available “fair copies” were manually transcribed in blank ledgers provided for that purpose. A “fair copy” is a neat and exact (and easily readable) copy of an original document that is copied either from the original or from a press copy of the original. Both the Whiteley/Thornton and Balch letter books are, fortunately, fair copies.

The Balch letter book measures approximately 13 inches in length and 10.5 inches in width. The book contains a name index and 317 pages with the first letter dated 26 October 1861 and the last dated 10 March 1862. The original spine is missing but the worn original covers are with the volume. The previous owner, the noted U.S. martial arms collector and researcher Anthony Daum, had the volume rebound in leather with “Letters” on the upper spine and “ORDNANCE DEPARTMENT” on lower spine in gilt letters. After Daum’s untimely death the book was sold by Cowan’s Auctions in October 2014. The catalog description listed the book as containing “hand-written journal entry records of orders, shipments, etc., from the Springfield Arsenal during the Civil War.” Given Balch’s office was located at the armory and some of the book’s contents, the auction description is understandable. However, George Balch was at the armory primarily as a matter of convenience and this book is a record of his correspondence as an inspecting officer of contract ordnance rather than one dealing with Springfield Armory

FIGs 2 & 3. The 1861–1862 George T. Balch letter book, cover and spine. Max Guenthert collection; photo courtesy of Paul Davies.

operations.5 An astute and knowledgeable Swiss collector who now lives in Japan, Max Guenthert, noted the book on the Internet, recognized its importance to American Civil War contract arms collecting, especially to the collecting of martial Colt revolvers, and bid accordingly.

Prior to and at the start of the Civil War, contract arms for the U.S. Army were procured primarily by the commanding officer of the New York Arsenal and that officer served as the Inspector of Contract Arms. In August 1861 that officer was Whiteley and he continued in this role for some arms bought under formal contract.6 However, due to the press of business brought about by the war and the need to buy all available serviceable arms that could be found, Chief of Ordnance James W. Ripley assigned Maj. Peter V. Hagner as the Ordnance Department agent for procurement of ordnance stores on the open market with his station in New York City. On 3 August 1861, Ripley told Hagner it was important he be in New York City at all times to purchase arms and other ordnance stores as they arrived and that Lt. George T. Balch was being sent to him to assist with other duties that might take him away from the city. Hagner was to restrict his efforts to the New York City area. Balch was told the same thing and his place of duty would be Springfield, Massachusetts. On the same day Ripley advised George Dwight, the civilian superintendent of the Springfield Armory, Balch was to visit Springfield soon and he was to confer with Dwight regarding expediting the armory’s manufacture of arms.7 It should be noted here this was after the far more experienced Major Hagner had already visited and made numerous suggestions to the same end.

The tasking given to Balch at this time, and to Hagner and Whiteley, reflect two things about Ripley. First and foremost, he had great confidence in Balch. This confidence appears to have been well placed from the standpoint of technical competency and energy. From the standpoints of trust and loyalty it is less clear. Second, Ripley did not display good personnel management skills, at least at this time, for on more than one occasion he failed to establish clear lines of authority and responsibility and, in fact, assigned the same duties to two of these men.8

On 5 August, Hagner advised Ripley of Balch’s arrival and Baich had been briefed on all work north and east of New York City.9 It is not clear Hagner had any inspecting officer responsibilities for arms under formal contract in these areas, but apparently Ripley intended Balch to have such responsibility for arms (and other ordnance stores) as on 6 August he telegraphed the lieutenant telling him to “urge all contractors forward. Work nights and put on more hands ... .”10 Either Ripley intended Balch to do exactly that or his directions to him were ambiguous, as on 17 August Balch reported on a visit he had made to the Sharps Rifle Company even though Ripley was well aware that Whiteley was in charge of the inspectors already working at the Sharps Company.11 On 22 August, Ripley advised Whiteley of Balch’s report of the visit and instructed him to inspect carbines Balch had said would soon be ready.12 Perhaps Ripley recognized his redundant tasking of these three officers, as on the following day he wrote Major Whiteley as follows:

I desire that you will make some arrangement with Maj. Hagner and Lt. Balch with regard to the inspection of contract supplies that will suit the convenience of all. If you cannot find it convenient to attend to this business yourself, by increasing your force of sub-inspectors, you will please inform these gentlemen of the fact and request them to attend to the inspection of the supplies that each may contract for.13

If this meeting occurred, it did not change responsibilities for the Sharps contracts and at least temporarily did not change responsibilities for those at the Colt’s Patent Firearms Company. But on 18 September, Ripley wrote to Whiteley, informing him he did not think the major’s duties at the arsenal would permit him to inspect as rapidly as required by the significantly increased number of Colt revolvers that were to be supplied and, therefore, he had assigned the duty to Balch. On the same day he wrote to Balch, forwarding copies of letters to and from Colt regarding deliveries and explaining what was expected and promised. Balch was to ensure the expectations of the department were met. This was to be a temporary assignment after which Balch was to return to the Ordnance Office and resume his duties as an assistant to the chief.14

Balch probably used Springfield Armory clerical assistance initially, but on 19 August he asked for the

authority to hire a clerk at $3 per day.15 Ripley, who wanted Balch to return to the Ordnance Office as soon as possible, answered on the 23 August, stating that he was authorized to do so on a temporary basis but only for as long as necessary.16 However, due to the press of wartime business and the shortage of experienced ordnance officers, Balch had to remain on this duty for over eight months. By the end of the period he had employed four clerks, had received goods valued at two and a quarter millions of dollars, and had dealt with more than forty suppliers.17 As his letter book shows, he clearly was a very busy man.

There is no indication in Ordnance Department records Balch, who was promoted to captain on 1 November 1861, had anyone to assist him in this work other than clerks.18 He probably hired his first clerk, C. O. Chapin, shortly after receiving the above approval, but as noted above, the first entry in the letter book was not made until 26 October 1861. The book’s subsequent entries concerned all manner of ordnance stores. Just as examples from the first few pages, Balch corresponded with the following concerns:

James Ames, Chicopee, Massachusetts—cannons

O. Bradley, Worcester, Massachusetts—forges

E & G Fairbanks, St. Johnsbury, Vermont—stirrups and bits

W & E Graley, Troy, New York—cavalry saddle trimmings, which were to be sent to J. B. Baker & Co. of Boston, W. H.

Wilkins of Springfield, W. Crowley of Troy, New York, and J.

S. Read of Boston.

James R. Hill, Concord, New Hampshire—harnesses

J. G. Chase, Springfield, Massachusetts—packing boxes

Wilkinson & Cumming, Springfield, Massachusetts— harnesses, slings for Smith carbines, etc.

Balch also obtained harnesses from E. Gaylord, Chicopee, Massachusetts, but of more general interest, Gaylord was one of several suppliers of accouterments and many of the entries in the book related to procurement and inspection of those stores. In fact, one factor making this book so significant is it contains Balch’s letters to his inspectors; letters that can be found nowhere else. As one example regarding cartridge boxes, on 31 October 1861 Balch wrote J. L. Wilder in Hartford, Connecticut, instructing him regarding the poor sewing (machine sewn rather than hand sewn) of the pocket flaps of infantry cartridge boxes made by Smith, Bourne & Co. Balch wrote him again on 6 November and said the acceptability of machine sewing depended upon the type of stitch and machine used. He said the stitching done by Cook & Co. (of New Haven) was acceptable but the stitch used by SB&Co (of Hartford) would come out if cut or broken in one place.19

Balch apparently hired some of his inspectors directly for stores such as leather goods. But for small arms he obtained them from among the Springfield Armory’s most experienced workmen, just as Thornton and Whiteley before him had done. Balch was responsible for the inspection of some swords and sabers but his most important small arms duty was the inspection of Colt revolvers. That work had the personal interest of Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan, then the most influential officer in the U.S. Army. Regarding those arms, Ripley wrote him on 20 September:

Referring to the enclosed copy of a letter from Gen. McClellan to the Secy. of War, (which is sent for your information only), and to the telegram from Saml. Colt and reply thereto, I wish you to visit Colt’s Armory, frequently, and to spend as much time there as you can spare in order to secure the delivery of all the pistols possible to the U.S. government. If it is possible to convert the machinery and appliances there now engaged in the manufacture of Navy pistols to that of Army pistols of the new model, it should be done so as to increase the deliveries of the latter kind. But if not, then we should have the entire product of both kinds. Let all the pistols you can get be sent on here every two or three days to Washington Arsenal, and report frequently as to the progress made in supplying them. It will be well for you also to call as often as you can at Ames’ works, Chicopee, and hasten the deliveries of sabers, swords, and other articles he may be making for this Dept. Report each shipment from either place by letter.20

The only other revolver under contract to the Ordnance Department at this time was the Savage, which was far inferior to the new Colt Model 1860 Army revolver. Balch was also responsible for inspection at Savage but in addition to being less desirable, production of the Savage was not great while Colt was promising to soon deliver at the rate of one thousand pistols per week.21 Army leadership had initially resisted the use of volunteer cavalry but the disaster at the Battle of First Manassas, and other reversals, showed the error in this position. Consequently the cavalry force was expanding greatly and rapidly but there were very few suitable arms available for its use. From all the author can tell through Ordnance Department records, the weapon most in demand during the period of Balch’s service as an inspecting officer was the revolver and Colt was the only source for pistols of army (.44) caliber.22

While there are many Colt-related letters in this volume not available in any other source known to the author, the same is true for other suppliers. Balch also inspected Smith carbines being made by the Massachusetts Arms Company. As one example of a significant letter for that company, on 17 December 1861 Capt. Balch wrote to Ames’ agent, T. W. Carter, and ordered four hundred Smith carbines to be delivered as soon as possible, saying this lot of carbines, which Carter had reported ready for inspection, would form part of a larger order and an inspector would be sent in a few days.23

However, the letters related to Colt and Sharps are more important to later events in Balch’s life and his relationships with other Ordnance Department officers.

Balch was initially very accommodating in his dealings with the Colt Company. For example, he removed one of his inspectors from the company when Sam Colt objected to his presence, even though Thornton had refused to do so when Colt had requested the man’s removal earlier.24 As the following series of letters will show, Balch was more lenient with Colt than he should have been.

On 4 December 1861, Balch telegraphed Ripley, “Please stop payment immediately on last certificate presented by Col. Colt for one thousand pistols. The receipt from Major Whiteley was obtained by false representations. The certificates were not approved by me. More by mail.” A scathing letter about Colt followed. Balch had gone to Troy, New York, and claimed to have been in communication with Colt about signing papers regarding deliveries before leaving. Only his side of the issue is documented and it is impossible to say for certain what the true story was but his letter of the fourth was regarding papers finalizing the delivery of one thousand Colt army pistols. These revolvers had been delivered to Whiteley at the New York Arsenal and Colt claimed the paper work had been sent to Springfield by messenger, believing Balch would be there to sign them. When he was not they attempted to get Whiteley to sign them, stating Balch could not be found. But Whiteley would only, as was proper, sign a receipt for the pistols received, not the inspection certificate that was also needed to submit the bill. Whiteley sent the papers to the Ordnance Office and so advised Balch. Balch angrily stated Colt knew where he was and when he would return but choose not to wait, adding:

The company have displayed much greater zeal in obtaining the necessary signatures to their certificates, desiring as they repeatedly do the sub-inspector’s certificates, before the pistols are even boxed, than they do in keeping the promises made in Sept. last in regard to an increased product, and giving the Ord. Dept. the whole of it and to say the least, such precipitate and fraudulent means to obtain their pay comes with very ill grace from them. When I was directed by you to take charge of this inspection, with a view of accommodating the company, and to enable it the sooner to obtain pay for the pistols we received, I receipted on my own certificate of inspection instead of leaving the company to wait one, two and perhaps three weeks for the receipt of the officer to whom they were ultimately sent. If the company have (sic) been obliged to wait on one or two occasions because I was absent, they have been more than compensated for the delay by the time I have repeatedly saved them awaiting the receipts of the officer to whom they were consigned. As long as I am the Inspector at this establishment it is of the first importance that the business of the inspection should be done as I direct, and that my authority should be obeyed and respected ... . 25

This letter is in the Chief of Ordnance files and is on page 106 in the letter book. Regarding its contents, it should be noted while Balch was responsible for inspection of other ordnance stores beside Colt revolvers and may well have had official business in Troy, the Ordnance Department files contain no official orders for the travel and Troy happened to be where his wife was living. More importantly, Balch had been negligent in this matter. He also later admitted he had, in fact, told Colt to send the certificate to Springfield for his signature.26 He closed this letter with, “If I have neglected my duty it is a matter to which I am alone answerable to the Dept. and to its decision I am always ready cheerfully to submit.” Given he was a great favorite of Ripley’s, he probably was not worried. However, General Ripley would come to regret the trust he had placed in the captain. Likewise, if Whiteley had previously had a good relationship with Balch, this incident may have ended it. On 4 December, Balch wrote Whiteley:

The pistols were issued to you by me and I must hold you accountable for them. I greatly regret that you should have lent an ear to any representations made by Col. Colt’s agent as in stating to you that I could not be found. He stated a deliberate untruth. I was in Troy on duty, where I could have been easily reached and Col. Colt’s agent knew it, as the messenger dispatched by Col. Colt was so informed by my clerk, Mr. Chapin. … I beg that in future you will pay no heed whatever to solicitations such as these, at least so long as I am the party to be aggrieved.27

The following day Balch wrote Hugh Harbison, Colt treasurer, telling him to immediately return by express the eighteen blank inspection certificates sent to him some time since. This is another accommodation to Colt that Balch had made, one neither of his predecessors would have done. In all other cases the author has seen in Ordnance Department records, only the inspecting officer or his principal sub-inspector held these certificates and they were signed and given to the contractor only after a delivery was ready. On the same day Balch wrote his principal sub-inspector at Colt, John Taylor, as follows:

The last certificates signed by you were sent here by special messenger by Col. Colt last week. Not finding me here Col. Colt took the liberty of presenting the certificates to Major Whiteley for his approval and he very properly refused to sign them. In consequence to this disregard of my authority … I have directed Mr. Harbison to return to me immediately all the blank certificates of mine now in his possession and you will in future be governed strictly by the following directions in signing certificates. You will sign no certificate whatsoever unless they are sent you by myself. When 1000 pistols are ready for shipping, you will give Mr. Harbison three blanks to fill up. If correct you will then sign as “principal sub-inspector” and transmit the papers to me by mail directly, in no case permitting them to pass through Col. Colt’s office or through the hands of any of his agents. I will forward them to the Company’s Secretary myself. I enclose three blank certificates for the next 1000, 500 of which have already been forwarded to Col. Ramsay.28

FIGs 4 & 5. Colt Model 1860 number 87477 was delivered to the New York Arsenal on 6 January 1863 but is representative of those delivered during Captain Balch’s service as inspecting officer. John Taylor’s cartouche on the grip. Photos courtesy of Paul Davies.

Regarding the shipment in question and its related paperwork, Captain Balch wrote Harbison on 9 December regarding an inquiry from the Colt Company,

… of the 5th making inquiry as to the disposition made of the certificates for 1000 pistols brought here by your agent on the 27th ultimo. The letter is not satisfactory as I do not see what authority Major Whiteley has to sign certificates for me so long as I am inspector at your works. I have therefore requested General Ripley to stop payment on the certificates until they may have been approved by me as prescribed by my instructions. In order to prevent in future any such disrespect of my authority while connected with your company, I have directed my principal sub-inspector upon signing the duplicate certificates to transmit them directly to me by mail, in no case permitting them to pass through the hands of agents of the company, and in view of the manner in which both my authority and my confidence have been abused, I intend to see that the instructions are strictly obeyed.29

Balch had been doing the company a favor in the procedures he was using and they appear to have been overly aggressive in attempting to get their payment as soon as possible. In the process of doing so they attempted to go around him as the inspecting officer and made an enemy of a man who had far more influence than most Army captains. In November 1863, nearly a year and a half before the end of the war, Balch would be instrumental in the Army’s decision to stop contracting with Colt for revolvers.30

Balch does not appear to have attended any of the final inspections for Colts delivered while he was inspecting officer. If he did, no records reflect that fact. While he did inspect Ames cannon in person and was described by James Ames as being too exacting, no small arms are known bearing his initials.31 Certainly, he was less involved than any of the other officers who served as inspector officer for Civil War or pre-war Colt pistols. As an example, there was considerable confusion regarding his records of deliveries compared to those of the factory. On one occasion he had to go to Hartford to meet with Harbison to resolve differences in their respective records.32 In his

FIGs 6, 7, 7a – This 1861-dated Ames 12-pounder mountain howitzer has Balch’s initials “G.T.B.” on the muzzle. Photos courtesy of James D. Julia Auctioneers, Fairfield, ME.

defense it should be stated he was a very busy man at a very chaotic period during the war and, unlike Whiteley and Thornton, he did not have extensive experience as an inspecting officer.

The inspection of Sharps arms provided another situation that lead to conflict between Balch and Whiteley, which was precipitated by an order from the War Department. On 23 October 1861, the War Department directed Ripley to send one thousand breech-loading carbines (Burnside or Sharps) and sabers to Col. T. L. Dickey, Springfield, Illinois. The letter indicated the regiment was “now ready” and an order for immediate delivery was to be sent to Hagner. Ripley immediately sent a copy of the War Department order to Hagner and ordered him to comply. Perhaps recognizing that Hagner had no role in inspection and receipt of carbines, on the twenty-fifth, Ripley then ordered Balch to send the first one thousand Sharps carbines he could get delivered to Dickey. Hagner was advised of this and told to send the sabers, which he could obtain in New York City.33 This was in spite of the fact Whiteley was the inspecting officer in charge of the Sharps contract and normally received such orders. On 30 October, Balch first wrote Palmer at Sharps saying to forward the first one thousand carbines he had completed after the receipt of this order to Colonel Dickey in Springfield, Illinois, and to report to Balch when the order was filled. It was to supersede all other orders he had. It should be noted here the Army policy at the time, and for most of the war, was to issue a cavalryman only one firearm, either a pistol or a carbine, and a saber. In

FIG 8. Balch Letter Book, page 9. The Balch letter book contains 317 pages with some letters that can be found nowhere else, such as this direction to the Sharps Rifle Company. Max Guenthert collection; photo courtesy of Paul Davies.

all cases where the author has seen this policy violated it was with officers having great political influence, which was the case with Dickey. Balch did as directed and in this case he then coordinated his action with Whiteley the next day.34 Unfortunately such coordination did not occur in the next instance, which was again a matter of political influence, the Sharps rifles for the Berdan Sharpshooters. The Berdan Sharpshooter arms’ story is lengthy and convoluted, but the bottom line is, thanks to Major General McClellan and Secretary of War Stanton, Colonel Berdan could (and did) get whatever arms he wanted. He first asked for 750 Springfield rifled muskets in July and was told they could be issued to him in Washington when the regiment arrived there. After getting this answer he then asked for them to be “bronzed and made easier on the trigger.”35 It is unlikely the rifles were blued or made easy on the trigger for him and it is also unlikely any were ever even issued to him. But the order reflects Berdan’s influence since at this point in the war most volunteer regiments were lucky to get enough rifles to arm their flank companies and had to take smooth bore muskets for the others. Regardless, the Springfield rifle was not good enough for him and in November McClellan’s ordnance officer requested one thousand Colt revolving rifles be bought for Berdan.36 These Colts were shipped in late December and issued shortly thereafter but ultimately proved to be unpopular with the Sharpshooters. In January 1862, the Ordnance Department was directed to order one thousand Sharps rifles for Berdan, who had complained his regiment was unarmed. Ripley replied to the secretary of war on 27 January, stating he had procured the Colt rifles as directed and also, regarding the regiment being “without arms,” he quoted the letter from Berdan dated 19 July in which the colonel asked for 750 Springfield rifles saying he preferred them to all others. The Springfield rifles were accordingly sent to the Washington Arsenal for the regiment and there were also Harpers Ferry rifles with sword bayonets the colonel could have had if he had requisitioned them but he would not take them. The Ordnance Department ordered the Sharps rifles as directed but noted the order might impact delivery of Sharps carbines, which it did.37 Further, the department was soon directed to order an additional one thousand Sharps rifles for Berdan’s second regiment. Unfortunately, Sharps could not deliver the rifles as early as initially promised, which caused the exchange of numerous telegrams and letters regarding their delivery. Finally, on 4 March, Palmer at Sharps optimistically reported the first one thousand rifles would be ready by the twentieth and the rest by 10 April, adding “interfered as little as possible with delivery of carbines … .” In a letter on the tenth, he stated Berdan had no cause to complain because the delay in delivery had been due to his insistence on having the sights and bayonets changed and double set triggers added.38

Ripley’s reliance on Balch soon made the situation worse, for in spite of the fact Whiteley was responsible for the carbine contract and already had inspectors at the company, he assigned Balch to the inspection of the Berdan rifles. He further compounded his error by making his direction ambiguous. His 13 March telegraphic order read, “Inspect and send on all the Sharps rifles ready on Saturday.”39

On 14 March, Balch wrote Ripley saying he had gone

FIG 9. This Sharps rifle with double set triggers, number 56753, is in serial number range of rifles documented to the Berdan Sharpshooters. Photo courtesy Rock Island Auction Company, Rock Island, IL.

to Sharps to inspect and ship the rifles but none had been ready. Palmer told him he would have five hundred ready in ten days but Balch doubted he would make that schedule. Balch said if Berdan had not insisted on double triggers and a hair lock the whole two thousand would have been in service by this date.40 Due to the wording of Ripley’s telegram, Balch believed his responsibility in the matter was finished and he did nothing further until Ripley telegraphed him again on 5 April to ship the first one thousand rifles directly to Fort Monroe for the 1st Regiment, Berdan’s Sharpshooters.41

Balch’s surviving letter book ends with an entry dated 10 March 1862, but fortunately his response to Ripley is in the Chief of Ordnance files. In his letter dated 7 April, Balch said he had immediately telegraphed Sharps asking the status of the arms and had gotten a reply on the sixth stating all the accouterments and ammunition had gone forward and one hundred rifles would be ready on the seventh and 60 to 75 per day would be afterwards. He said the only orders he had gotten regarding these arms before this was Ripley’s telegram of 13 March directing him to inspect and send forward all that the company had ready and he had reported they had nothing ready to inspect. He added:

No further instructions having been received by me on the subject, in view of the fact that Major Whiteley had control of the inspection at Sharps works, I did not feel authorized to take any further steps in the matter. On the receipt of your telegram of the 5th instant however, it evidently being your intention that I should take up and forward these arms, I immediately (on the 6th) gave explicit verbal instructions to one of the most energetic and competent inspector I have to proceed to inspect and forward the arms with utmost dispatch. A copy of my instructions to him is enclosed. As Major Whiteley has but two sub-inspectors at Sharps to examine the same number of arms for which I find four imperatively necessary, I did not feel authorized to call on his men, and have therefore temporarily assigned enough of my men there, to take up two hundred arms per day if offered, and the Dept. may therefore rest assured that this lot of arms will go forward just as rapidly as the manufacturers turn them out.42

In his instructions to Principal Sub-inspector John Taylor, Balch said to take all the men he needed from their inspection duties at Colt and, in order to further expedite the inspection, to examine strictly only the most important parts of the rifles. Taylor appears to have taken three inspectors from Colt. Due to the fact that most arms contracts were at this time being held in abeyance while the Holt-Owen Commission examined all outstanding contracts for arms, this does not appear to have adversely affected Colt, but it did have a negative impact on Sharps.43

On 9 April Palmer wrote Ripley:

Mr. Hartwell and Mr. Chapman, Sub Inspectors stationed with us by Major Whiteley last fall, have first proved near 2000 rifle barrels for the Berdan Sharp Shooters, and inspected several hundred finished barrels, receivers, stocks, bands, locks, screws and other parts, and some 150 to 200 of the rifles are assembled ready to snap off and be sent forward. I yesterday received instructions from Capt. Balch, Ord. Corps, as follows. “I do not feel authorized to call on Capt. Whiteley’s inspectors to examine these arms in view of all the other work they have to do. I have directed Mr. John Taylor to take charge of the inspection of these rifles and have given him ample assistants to inspect if necessary two hundred arms per day. You will please give him all necessary facilities to push forward the inspection with utmost dispatch, but no arms are to go forward until passed by him. As soon as one hundred arms are inspected they will be forwarded to the following address—Lt. J. G. Baylor, Fort Monroe Arsenal, for First Regiment Berdan’s Sharp Shooters, care of Col. D. D. Tompkins, Asst. Q.M. General, New York. And as fast as 100 are inspected they will be shipped to this address until 1000 have been sent. The remainder will be kept until you receive further instructions from me.” Mr. Taylor has entered upon his duties with three assistants this morning. It is not possible for us to turn out more than 65 to 75 rifles per day and very little can be done on carbines until the rifles are turned in. Hartwell & Chapman, by hard work day and night and sometimes on Sunday, have kept the work up on carbines so that we have made near 2000 a month for the last 4 or 5 months or about 80 per day. To forward the arms with the greatest dispatch we want all of the bench room we can have, and two sets of Sub Inspectors crowd upon us very much and the state of feeling exists between them is anything but agreeable. If, however, in your opinion the public interests will be promoted by keeping the two sets here we shall cheerfully conform to your wishes and do the best we can to get off the arms.44

Ripley’s only reply to Palmer was to say Balch’s actions were approved and Palmer was to “afford his inspections [sic] all necessary facilities for a rapid completion of this work.”45 Whiteley had forwarded a letter from Palmer to Ripley that probably said the same as his letter to Ripley above, but we don’t know what Whiteley said in his endorsement. However, Whiteley’s response to this situation is given in two letters in his letter book. On 10 April, he reassigned William Chapman to Chicopee to assist John Hannis inspecting swords and sabers at Ames, telling him he would return Chapman to Sharps when Sharps resumed carbine work in full. He then informed Hartwell of Chapman’s reassignment and told him to remain at Sharps and inspect as many carbines as the company could furnish. He added, “Give Capt. Balch’s assistants all the information in reference to the work as far as you progressed but do not touch it again. You will not obey any orders from Capt. Balch, if he gives you any you will refer him to me. I wish 500 carbines as soon as possible and as many as the company can make immediately after.”46

In spite of all the special tasking Ripley gave Balch, as

FIG 10. The cartouches on Berdan configuration Sharps rifle number 54733, are those of Allen W. Mather, Edward Flather, and Thomas W. Russell. Mather’s service is not documented in the few surviving inspection records for the Berdan rifle period but his cartouche is found on some Smith carbines from the 1862–1863 period. Flather’s early service is not documented either, although his cartouche is found on some Colt revolvers delivered in June-August 1862. But on 7 April 1862 Capt. Dyer at Springfield Armory ordered Russell, the most senior of the three men, to report to Balch for inspection duty (RG156, E1351, Springfield Armory letters sent). Photo courtesy Rock Island Auction Company, www.rockislandauction.com.

FIG 11. James W. Ripley, Chief of Ordnance, 1861–1863. Courtesy of the National Archives , Washington, DC.

noted above, the general was anxious for him to return to Washington. As early as 23 November 1861, he told Balch he wanted the captain to turn over his business to another officer “who will probably relieve you in a short time” and Balch would then be ordered to duty at the Ordnance Office. That was not to be and instead, later on this same day, Ripley authorized Whiteley to call on Balch for inspection assistance since the major had so much to do at the New York Arsenal.47 Ripley next wrote Balch, on 25 March 1862, stating he was to close his present business as soon as practicable and report to the Ordnance Office for duty.48 This was after placing Balch in charge of inspecting the Berdan rifles on 13 March, and at the time of his letter none of the rifles had been delivered. Balch replied saying he was hiring a fourth clerk to expedite preparation of his paperwork.49 Again, on 7 April, Ripley telegraphed Balch Lt. Col. William Maynadier, Ripley’s principal assistant, was too ill to work and Balch should report to Washington for duty immediately. He sent another telegram on the tenth asking if Balch had received the earlier one. The captain finally showed up at the Ordnance Office on 12 April, but by the twenty-fourth he was back in Springfield working on the Sharps rifle inspection and two days later he was told to take charge of the inspection of ten thousand sabers made by D. J. Millard, Clayville, New York.50 However, Ripley was in the process of setting up an office of “Inspector of Contract Arms and Accouterments,” to which duty he assigned Thornton on 23 May 1862. Except for the completion of the Savage revolver contract, the last delivery of which was on 10 June, on 3 June, Balch was ordered to turn over his inspector duties to Thornton along with all books and papers related to his inspection assignments.51 His last remaining task was given on 11 June, when he was ordered to return to Springfield and to close out his duties there, turn over public property to the military store keeper, and his remaining books and papers to Capt. Alexander Dyer. He was then to return to the Ordnance Office for duty.

Obviously, Balch’s letter book was government property and presumably it would have been turned over to Thornton. How it got into private hands is unknown. In addition, given the book ended on 13 March 1862 and Balch’s duties did not end until months later, there probably was another letter book that followed this one. The Whiteley-Thornton inspection letter book remained in the records of the New York Arsenal to this day, probably placed there by Maj. Julian McAllister in 1867.

George Balch is often described as the “de facto Chief of Ordnance” for the period September 1863 to September 1864, the period when George D. Ramsay held the chief’s position. He is even included in the Ordnance Corps Hall of Fame with the rationale being based on his service during the above period. That service has gotten the most attention from historians, while Balch had also served as an assistant to General Ripley from June 1862 to Ripley’s retirement in September 1863. Some have said Ripley’s retirement was forced upon him due to his “refusal to utilize and promote newly developed weapons.” That is at least in part true. But, for the most part, in the author’s opinion, Ripley was not wrong in what he did. However, in doing what he thought was right he made enemies of many influential men. Other factors were at play in his removal as well. As indicated in the above material, Ripley does not appear to have used his personnel most effectively, which probably contributed to the dissatisfaction felt by both his

superiors as well as some subordinates, chief among them being Captain Balch. But it appears there was much more to the story.

The author has been researching Ordnance Department records for forty years and still has not had an opportunity to review many thousands of documents. But he happened upon an obscure entry titled, “Miscellaneous Correspondence, 1833–1912,” which contained an extraordinary package of documents related to this subject. To the author’s knowledge, these documents are published here for the first time. This small package contains a hand written copy of a letter dated 31 August 1864 from General Ripley to Captain Balch and a printed document consisting of an undated introduction and a letter from Ripley to Balch dated 19 September 1864. All of the material was found in an Ordnance Department envelope that bore General Dyer’s name and the words “Ripley–Balch Papers” written on it. The 31 August 1864 letter reads as follows:

I have understood within a few days that during my connection with the Ordnance Office, even as far back as 1862, you were using your efforts through official and political services to affect my removal from the position of Chief of

Ordnance. Considering our official relations at that time and the personal intimacy then subsisting between ourselves and families, I am reluctant to believe you capable of pursuing a course so entirely inconsistent with those relations.

It is nevertheless due to you that I should inform you of what

I have understood, and thus offer you the opportunity of removing the unfavorable impression which the information

I have received is so calculated to provide.

Your early reply will oblige.

The printed and undated introductory page reads:

Rumors, apparently well founded, having reached me, that

Capt. Balch, with other well-known conspirators, had been secretly plotting to accomplish my removal from my position as Chief of Ordnance, (even as far back as August, 1862,) I addressed him a civil note, informing him of the nature of the reports alluded to, and inquiring whether I had been correctly informed, thus affording him an opportunity for explanation, if he had any to offer. To this simple note of inquiry, I received a studied and most insulting reply of four closely written pages, and under these circumstances the following rejoinder was written.

The printed Ripley letter to Balch, dated Hartford, 19 September 1864 reads:

Your letter of the 3rd instant is received and read. Although you begin by a profession of candor in a simple reply to a plain question, your long and labored letter shows evident duplicity, sought to be hidden by you under the ostensible garb of duty. But your heartless impudence cannot cover up or conceal from any honest mind your total want of candid frankness in answering a plain question, or hide your disgrace and dishonor in what you have impudently avowed, only because you dared not deny it from fear of the proof at hand. From this plain insight into your character, furnished by yourself and from other indisputable evidence in my possession, I cannot but reach the conviction that the “complaints and charges” in regard to my official conduct, to which you refer, as well as to the assaults on my personal integrity, which you take credit for defending, have been originated and spread by yourself, whether from malicious heartlessness of from self-interest, or whatever motive, your own consciousness can alone tell. So much in regard to the general character and purport of your letter. As respects its particulars, they, like all other mean subterfuges, may be readily exposed. Your audacious assertion that at my earnest request, you called on Senators Fessenden, Grimes and Pomeroy, for the purpose of placing my “services and merits” before them in such a light as would induce them to vote for my confirmation, is the coolest piece of impudence ever uttered, even by you, and on my responsibility I pronounce it an unmitigated and malicious falsehood. My nomination, with hundreds of others, was for a long time before the Senate unacted upon, but I never asked any Senator for his vote, though I did request several, as opportunity offered, to endeavor to have my nomination called up and acted upon at as early a day as possible, and it is quite probable that I may have asked outside friends to use their efforts to the same end. To this extent I may also have requested, among others, your co-operation, but that I should have solicited Captain Geo. T. Balch to place my “services and merits” in a favorable light before the three Senators you name, one of whom I have known intimately more years than you have numbered since your birth, is too preposterous for belief. It is, indeed, a monstrous lie. From the time I took charge of the Ordnance Office till the day I left it, Colonel Maynadier occupied the same room and a desk beside me, and was cognizant of almost every business matter that occurred during that time. I can confidently appeal to him to prove the falsity of your general charge of my “official rudeness.” I must admit that, on one occasion, Major Benton witnessed a scene in the office that might be considered somewhat rude on my part, when I ordered an infamous fellow, who dared to offer to “make it for my interest” to give him a contract, out of my office, and threatened to kick him out if he did not go immediately. Were you ever tried in any such way, and did your sense of wounded honor induce you to spurn the base proposition as well as the fellow? Did you feel insulted and express your indignation in unmistaken terms, or did you pocket the affront? I have heard of such instances of official courtesy and honesty on your part, intimated, and without being able to find a warrant for denying their truth. I could not, therefore, defend your personal integrity, as there were no grounds on which to base such defense; but on the contrary there has recently come into my possession evidence confirmatory of that style of courtesy in your official transactions. You further state that as you gradually obtained a clearer insight into the duties and responsibilities of the Bureau, and became familiar with the manner in which I administered its affairs, you discovered many evil practices and wrong doings. Even you will not deny that Col. Maynadier and Maj. Benton, who were more intimately acquainted with my official acts, are observant men, possessing fair ability, at least equal to your own, and if, as you asserted, the Department was “daily losing

FIGs 12, 13. George Balch had some influential friends who came close to getting him promoted to the Chief of Ordnance position. Perhaps they presented him with this pistol, a Colt Model 1849 Pocket model, serial number 185912, with an inscription that appears to read: “Presented to Capt. George T. Balch, USA, by his friends in New York, 1862.” Photos courtesy of Paul Davies.

position, reputation, everything, neglecting our duty, and making enemies,” how shall these gentlemen stand excused for not sounding the alarm, and making an effort to arrest the impending destruction of our Corps? Have they less interest in protecting its honor, interests, and usefulness than yourself? They are not only able, but honorable men, who would scorn to seek a private benefit at the expense of one jot or tittle of their conscientious sense of uprightness. But you are incapable of appreciating the motives which govern the actions of such men, and are driven to assign false reasons to hide your baseness and treachery. The real motives for the dishonorable course you have pursued must be sought for, and will be found, elsewhere than in my “mal-administration” of the Department, or your high sense of “duty,” of which you prate so glibly. They may find in your correspondence with one of your fellow-conspirators, “My dear General.” Did you ever indulge in aspirations for the succession in case the conspiracy to affect my removal should succeed? If not, will you with your usual candor and frankness, interpret the following passages contained in some of the letters to “My dear General,” in your own handwriting and bearing your own signature? “I have fully made up my mind that I can fill the position you spoke of, as I believe, with credit to the Department, and acquit myself of the trust in a manner which will not disappoint the confidence which you and other friends repose in me.” “I feel that if anything is done by my friends in the matter, it should be done now, and I am going to ask you to take up the matter, and after obtaining all the influence you can bring to bear, push the business.” “I shall be able, before the end of the year, to give the most detailed and extended statement, readily, on any matter connected with the Bureau.” But I will not multiply these damning proofs of your unparalleled perfidy. They will suffice perhaps, to convince you that I am acquainted with your dishonorable and dishonest practices for more than two years past. If not, there are more of the same kind, which in due time shall be brought to light, and will make known to the world your true character, as plainly as if the brand of Cain were seared on your forehead. They will show you that the way of the transgressor is hard, and that the vilest reptile that crawls the earth, however serpentine his course, leaves a track behind, by which he may be followed, and if need be, his head may be bruised under our heel. You speak generally of favoritism on my part. Can you specify a single authenticated instance of such favoritism during the whole period of my service in the Ordnance Office? If you can you are bound, and I challenge you to do it. If not, you stand forth a convicted liar. But not only in this have you lied. Your statement in your letter to me, that you did not at any time during my term of office, that you are aware of, use any efforts whatever, through political channels, to affect my removal, is proved to be a lie by your own letters, addressed to Charles T. James,52 of Rhode Island, in your own handwriting and over your own sign manual. These letters prove that you did use such efforts during my term of office, privately, surreptitiously, and deliberately; and without the possibility of your not being aware of it. You speak of the reputation of the Ordnance Bureau for fair dealing being in question. It was never to my knowledge or belief, since I took charge of the Bureau, called in question till in an evil day you were introduced into it, and have since had too much to do with the conduct of its affairs. Recently throughout the army, complaints and curses loud and deep, are heaped upon it, or rather upon your head; for it is well understood with whom originate the many vexatious and petty annoyances to which officers of all grades have been subjected, to say nothing of the curt and uncivil letters addressed to them. You speak of your “official” connection with the War Department. You never had any such connection with it while serving under my command. You were simply on duty in the office of the Chief of Ordnance, as one of his assistants, and while serving in that capacity, you basely and falsely conspired against him, and perfidiously betrayed the confidence, both personal and official, which was necessarily reposed in you, from the position you occupied. The annals of the Army may be searched in vain, I am happy to say, for as flagitious an instance of moral and professional turpitude. As regards the instance you adduce of assaults on my private character, viz.: the connection of Mr. Knapp with my purchase of a house in Washington, it has too little ground, in fact, on which to base a plausible scandal. I have ample proof in my possession of the character of that transaction (and it may also be found on application to Riggs & Co., Bankers, Washington, with whom the purchase money was deposited by me months before the deed of the property was delivered,) throughout, and on which I am entirely willing to base the defense of my personal reputation, if it should be called in question by anyone whose character and previous

conduct do not render him unworthy of belief. I have already expressed my conviction that the slander originated from the same source that concocted the conspiracy against my official reputation, and I must adhere to that conviction notwithstanding your assertion that when you have heard my reputation for “integrity” “frequently assailed” you have “invariably defended me.” If so, it must have been from some motive of self-interest, and I think I duly appreciate the obligation. But when you add “my testimony on this point has, I have reason to believe, counteracted the effect of accusations, which, if true, would ruin your personal reputation,” my mortification is extreme. I cannot think that I have fallen so low as to have ever done an act, which should subject me to the deep humiliation of having my “integrity” defended by you, and I must beg, as the only favor you can do me, that you will, hereafter, entirely refrain from any further efforts in my defense.

(signed) Jas. W. Ripley53

Alexander B. Dyer was appointed Chief of Ordnance on 13 September 1864 and this package of documents was probably given to Dyer sometime after 19 September 1864. Gen. George D. Ramsay had been placed on the retirement list but Balch also had already been reassigned by then, so these documents probably played no role in Balch’s removal from the Ordnance Office. Ramsay’s forced retirement and Balch’s reassignment instead appear to have been the result of several incidents that showed a near total collapse in the working relationship between the two men. But this relationship was doomed from the start.

When the decision was made to force General Ripley to retire, Secretary Stanton had favored promotion of Balch to the position of Chief of Ordnance. President Lincoln, however, favored Colonel Ramsay, commander of the Washington Arsenal and a friend of the President’s. Reportedly President Lincoln and Secretary Stanton compromised by giving the title to Ramsay and naming Balch as his “Principal Assistant,” but with everyone (except the unfortunate Ramsay) having the understanding that Balch was to run the Ordnance Department. Lt. Col. Maynadier, Ripley’s principal assistant of long standing, was reassigned outside the Ordnance Office, which caused Ramsay to rely almost exclusively upon Balch. This must have been very disappointing to Balch and it is not clear why he agreed to the arrangement, but he did.54 Not

FIG 14. George D. Ramsay, Chief of Ordnance, 1863–1864. Courtesy of the U.S. Army Heritage and Education Center, Carlisle, PA. surprisingly, due to the arrangement and Balch’s own nature, problems soon arose and on 10 February 1864 Balch asked to be reassigned to other duties. The following is his letter to General Ramsay:

I have the honor to request that I may be relieved from duty as Principal Military Assistant in this office by some officer who can perform the duties of the position more acceptably than myself, and that on being so relieved I may be assigned to some other station. My reasons for taking this step are as follows: So long as I hold my present position as your confidential assistant, it is only proper that I should be consulted on all matters which relate directly to the great interest or duties of the Ordnance Department. Recently events which have transpired [unreadable] about me, among which may be noticed the reference to my juniors in rank and experience of important questions hitherto peculiarly within my province and hitherto solely referred to me, are too significant to be misunderstood. It is evident that official confidence in me, so necessary to ensure harmonious action between us, no longer exists; and hence it is a duty I owe to you as well as myself that by voluntarily requesting to be relieved by another officer, I leave you free to take that course, which you deem the most conducive to the public interest. In our conversation this morning you were pleased to state several of the objections, which you and a number of the senior officers of the Department made to my course of action, since I had held my present position; some of these, such as a misuse of your name and authority; oppressing the officers of the Department with unnecessary labor; unnecessarily complicating the system of doing business in this office; pressing upon your notice vast schemes for enlarging and improving the principal arsenals with plans for an armory and foundries, too comprehensive to be considered when the wants of the Army were so pressing and demanded all of your attention; communicating with the War Department proper, without informing you of what transpired at such interviews; and lastly, an undignified, curt, and harsh style of correspondence by letter and telegraph. All these are charges of such a nature that even if not true, the mere fact that my course may seem to have warranted their being made is reason sufficient for my being relieved. For while I can conscientiously say I have done nothing since we have been associated which was not prompted by the purest of motives, with only what I considered to be the best interests of the Department and the service in view. I can readily understand how my instructions may have given offence and my motives been misunderstood by those who knew nothing of the circumstances, or who did not see the events and obligations of the Department from the same standpoint as myself. My views of the duties which devolve upon this office and upon me in my present position are of that character, though to continue to discharge them conscientiously would I am convinced only bring us continually in conflict.

This I most sincerely desire to avoid and hence I consider it my duty to prefer this request to be relieved and resign my position in favor of some other officer of the Corps whose method of transacting the business of the office, whose style of correspondence and whose view of the responsibilities of his position will be found more congenial with your own.55

Two points should be noted in Balch’s letter. First, Colonel Ramsay, not knowing he was expected to be only a figurehead, had consulted other officers on matters that Balch felt should have gone through him, the “real” Chief of Ordnance. Second, Balch was sending other Ordnance Department officers letters, under Ramsay’s signature, which were quite negative, curt, and offensive. Not knowing his own true status, Ramsay forwarded Balch’s letter on 11 February and recommended his reassignment:

When I took charge of the Ordnance Bureau in Sept. last, Capt. Balch was assigned as my principal assistant; and from his having previously served under my command where relations of the greatest kindness and the most friendly intimacy and confidence had existed between us, that assignment was not unacceptable to me. This relation, as well as the necessity of my relying on his knowledge of previous transactions of the Bureau, led me to consult with and confide in him almost exclusively until I could have time to learn and understand the various and multitudinous duties of the Department, and this, in the midst of pressing current duties allowing but little time for investigation. This confidence, Capt. Balch’s previous long experience in the Bureau, led me to adopt and to sanction by my official signature, much correspondence and many orders and instructions, and thus to assume a responsibility which with less assured confidence and with more time to have considered and scrutinized, I would and have done. My attention has been called unofficially to the effects of this course by some of the most trustworthy and experienced officers of the Dept. who have complained of a style and manner of correspondence seeming to reflect on their professional ability by a system of instructions in minute details, unnecessary for officers of so long and varied experience, and offensive to their self-respect. Circumstances rendered it necessary for me to mention this matter to Capt. Balch as our relations were not as cordial as heretofore; and I did so, openly and cordially, and stating that I had no other desire than that the affairs of the office should be carried on frankly and harmoniously. Hence comes the action which has been taken in the matter, as shown in his letter herewith submitted on the main subject of which I have respectfully to remark that while fully acknowledging his talents, industry and attention to his duties I can best believe that his mode of doing business is calculated to disturb the harmony and good will which should [exist] between the Department and its officers. I therefore recommend the acceptance of the resignation he now offers of his position in this Bureau and his assignment to another of equal honor and dignity.56

It was probably at this point General Ramsay had come to understand his true position. According to one source, Secretary Stanton gave him one week to “make up with Balch or be relieved from command.” Stanton also discussed the matter with Balch and on 13 February, Ramsay reported to Secretary Stanton, “It gives me pleasure to inform you that mutual friendly relations have been restored between Capt. Balch and myself, and I can but hope and believe that by cordial cooperation the affairs of the Ordnance Department will be conducted to your entire satisfaction and to the best interests of the service.”57

This cordial cooperation did not last long. According to one historian, by August, Ramsay was being “bombarded” with searching inquiries about various topics, “all implying negligence on Ramsay’s part, all signed by Stanton and all in Balch’s handwriting.” On 9 August 1864, Balch once more submitted his request for reassignment, this time directly to Secretary Stanton and not through Gen. Ramsay:

On the 15th Sept. 1863 in obedience to your order I was assigned to duty as Principal Military Assistant to General Geo. D. Ramsay, who was on that day appointed Chief of Ordnance. Two days before at an interview with the Hon. [Assistant Secretary] P. H. Watson he intimated that in the new arrangement of the Ordnance Office the War Department would expect me to be responsible for the efficient conduct of its business and looked to me to infuse into its acts new life and vigor. These remarks served to quicken my determination to give my best energies to the work before me, but I did not fail to perceive the difficult position in which this confidence of the War Department placed me as regarded my conduct towards the head of the Bureau. I undertook the task assigned me, however, hoping that by the exercise of patience and discretion and reliance on the personal friendship which for ten years had existed between General Ramsay and myself, to be able to preserve our pleasant personal relations and at the same time carry out the wishes of the Dept. as indicated by the Assistant Secretary of War. Although I have strenuously endeavored for eleven months to conscientiously discharge the duties assigned me, without wounding General Ramsay’s pride or encroaching on his prerogatives, however successful I may have been in discharging my duty I have failed in avoiding the two last evils and it is plainly evident today, not only that my presence is personally distasteful to General Ramsay, but that that official confidence in me so necessary to ensure harmonious action is entirely wanting. General Ramsay’s views of the duties and obligations of the Ordnance Department and his habits of thought and action are so essentially at variance with my own that I feel to be any longer associated with him under the present circumstances will only bring us in continued conflict. This I most sincerely desire to avoid and hence as to you I owe the position I hold, I have felt it but proper that to you I should explain the present situation of this affair. Without attempting to enter into the merits or demerits of the differences which have led to the present rupture I feel that it is better for the interests of the Bureau and the Ordnance Department that I should leave the Ordnance Office. I have the honor therefore respectfully to request that I may be relieved from my present position as Principal Military

Assistant to the Chief of Ordnance and assigned to some other duty where I can be of equal service to the Department during the continuance of the war.58

The “present rupture” was a very significant one and was one the new Assistant Secretary of War, Charles Dana, would not tolerate. On 30 July 1864, Dana had asked the Ordnance Department for information on its plans for improving the manufacturing capacities of its arsenals “upon which [an] appropriation of $2,000,000 was predicate,” and which had been granted by Congress at its last session:

You will state upon what specific data the plans are based, the nature of the data, and how they have been obtained, and the general principles which have governed the Bureau in assigning under these plans to each arsenal its appropriate work. You will also state what progress has been made in the detailed plans and estimates for the necessary shops, laboratories and storehouses, and what means have been [unreadable] to secure to the government for its use in these shops and laboratories, the benefit of the valuable experience in manufacturing material of war, gained during the past three years.

You will further report at what arsenals improvements under these plans are now in progress, when they may be expected to be completed, and also when all the improvements contemplated will be so far completed as to make this appropriation available for, and contribute to, meeting the immediate military wants of the country.59

This was not an unreasonable request, as anyone who has worked in agency budgeting in the federal government knows, for the request should have been based on detailed plans and operational data. On 2 August, Ramsay referred the request to Balch saying “as this branch of the Ordnance Bureau has been more particularly under your charge, [you will] cause to be prepared and submitted to me the necessary information to enable me promptly to comply with the Secretary’s order.”60 Balch’s answer on the fifth was far from satisfactory. Ramsay responded to Dana on 8 August. In a long letter that probably was painful to write, Ramsay said he had reviewed the records of his predecessor and there had been no such plans made “circumstances have rendered it inexpedient, if not impracticable, to continue the custom formerly in vogue of requiring plans and estimates of proposed [word not readable] at each post, to be furnished by the commanding officer in time to embody them, if approved, in the general estimate submitted annually to Congress through the Secretary.” He said according to the records of his predecessor for the last two years, no detailed estimates on accounts of arsenals was made and only a general appropriation of $500,000 was funded on the probable wants of the department. Since he took over as Chief of Ordnance on 15 September 1863, he had assigned the related duty to his Principal Assistant [Captain Balch]. The $2,000,000 request in question had been submitted to the secretary of war on 25 October 1863, and probably prepared some days before. Given, he had just taken over and was pressed with the associated responsibilities he had to rely on “the experience and faithfulness” of those assisting him. He had approved Balch’s estimate not doubting that it was “prepared with care and that it was based upon the well matured wants of the service … .”

Dana also asked what had been done to prepare plans for extending manufacturing capabilities, which should have been part of the overall plan used to develop the estimate. Ramsay was able to list some such plans (those to manufacture metallic cartridges, expand musket manufacturing at Springfield Armory, establish an arsenal at Rock Island, etc.), but it is clear these were not a part of any master plan used to develop the estimate for congress. There were also several defensive statements by Ramsay in this letter such as the following:

I would remark on this question in general that as Chief of

Ordnance it is not expected that I should give my personal attention to all the details of the business going on in my

Dept., but I am expected to depend, for the proper execution of such duties, upon the experience and fidelity of those who are associated with me, and upon whose earnest, honest cooperation greatly depend the preservation of that system of harmony and division of labor so indispensable to the prompt and correct dispatch of business.

To Capt. Balch above all others, as my principle assistant, I have given a carte blanche only restricted of course by my approbation. In the department of improvements at Arsenals he has selected his own architects, draughtsman and other assistants, such as Mr. Reynolds of Springfield and Mr.

Waters of Troy, of whom I personally know nothing; and I cannot but hope that with such resources as he himself had provided this preparatory work has been executed with all desirable accuracy.

Ramsay was correct in saying he could not have been expected to have been personally involved with the preparation of the budget submission and the associated detailed plans so soon after being assigned as Chief of Ordnance. But he should have verified the work had been done, or was being done, and was being properly documented. The submission was one of the most important responsibilities of his office and an increase in the appropriation from $500,000 to $2,000,000 was quite significant. However, while Ramsay may not have become directly involved with planning the expansion of the department’s manufacturing capability immediately upon assuming its leadership, it is clear that by this time he was well informed and engaged. He closed the letter with a statement of how the appropriation would be used, although it included a balance of $699,000 “not disposed of … .”61

This did not resolve the matter and Dana requested additional information, which was compiled by Balch. On 29 August, Ramsay responded to the War Department with Balch’s material, which the author has not found, and an endorsement that, together, sealed the fate of both men:

Capt. Balch presents an array of statistics, much of which, if not all, he has derived from the archives of this office. From his statements and deductions others might be lead to the very erroneous conclusion that the Ordnance Department had been since the commencement of the revolution in a comatose state; that nothing had been effected, and that it is behind the wants and necessities of the country. Whilst I will not engage in an official controversy with Captain Balch, I cannot allow the possibility of such an inference without asserting that no department of the government has since and during the rebellion furnished its supplies more fully, more promptly or more satisfactorily to the troops in the field. Not a cent appropriated for its service has been misapplied or wasted, so far as the Ordnance Bureau has had the power to control its application; and the capacity of the Arsenals for manufacture and storage has been much enlarged; as much, I think as was possible during the time, and with the immense amount of other work of the most pressing necessity … . … In whatever respect the Ordnance Department may be behind the wants of the country (which it has however, by untiring exertions and labor so far supplied) it has resulted from a want of that authority and those means. The $2,000,000 specifically referred to as appropriated for improving the manufacturing capacity of the Arsenals, has only been available since the 1st July 1864, a period less than two months; and as much has been accomplished towards that object as the limited time and circumstances would allow. Perhaps it may be superfluous for me to notice that Capt. Balch in his letter to me of the 5th instant states that he can find no data pertinent to the question as to the general plans of the Bureau for improving the manufacturing capacity of the Arsenals; in this letter of the 29th instant he states that the details of the estimate for that purpose were left to him, and goes on to say – first, generally for what Arsenals specific amounts of the estimate were to be expended—and second, to answer your question as to the specific data upon which the plans are based.62

On 12 September 1864, General Ramsay was relieved and placed on the retired list. The following day Captain Balch was reassigned to the military academy.63 Alexander Dyer was assigned as the new Chief of Ordnance.64 If the above sequence of events was not enough to end Balch’s military career, General Ripley’s 19 September open letter certainly was. On 12 June 1865, General Dyer asked the adjutant general to issue orders to Balch to take charge of the arsenal in Charleston, South Carolina.65 Balch chose to submit a letter of resignation instead. Dyer recommended

FIG 15. Alexander B. Dyer, Chief of Ordnance, 1864–1874. Courtesy of the National Archives, Washington, DC.

Balch’s resignation be accepted but it was not. Balch renewed his request on the thirtieth, but it was again denied.66 He reported for duty at Charleston Arsenal on 21 August, but was there only briefly, as his resignation, submitted by another letter dated 18 September, was finally approved.67 Balch reported himself as being in New York on leave on 1 November and his resignation was made effective as of 1 December 1865.68

After his resignation, George Balch worked as an auditor, initially for the Erie Railroad and later for the New York City Board of Education. According to the U.S. Army Ordnance Corps & School website he also published several technical volumes concerning the nature of railroad property, plants, right-of-way, and other related issues. While working for the Board of Education he worked

… to promote patriotism in the children of the nation’s public schools. A motto he drafted in this connection, “We give our heads and hearts to God and our country; one country, one language, one flag!” was adopted by a number of schools in many states. It was George Balch who proposed that flagpoles be erected on or in front of all the public schools in the nation, and he became nationally known for his work on this project.69

One of Balch’s related publications is illustrated here. Most significantly in this regard, Balch’s above quoted “salute” played a significant role in development of our country’s Pledge of Allegiance. Balch died of apoplexy on 15 April 1894 at his home in New York City and was buried in Troy, New York. He was 65 years of age.

FIGs 16, 17. George Balch’s patriotic primer for school children cover and spine. U.S. Army Heritage and Education Center, Carlisle, PA. Photos courtesy of Paul Davies.

FIG 18. George Balch late in life. Photo from Galusha Burchard, Balch, Genealogy of the Balch Families in America, https:// archive.org/details/genealogyofbalch00balc.

For their contributions to this article, the author would like to express his appreciation to Paul Davies, Max Guenthert, James D. Julia Auctioneers, Rock Island Auction Company, and Cowan Auctions.

Notes

1. Letter WD583 of 1858, Entry (E) 21, Record of the Office of the

Chief of Ordnance, Record Group (RG) 156, National Archives,

Washington, DC (NA). 2. Letter T409 of 1858, op. cit. 3. Vol. 33, page 415, E6, op cit. 4. Francis B. Heitman, Historical Register and Dictionary of the

United States Army, 1789–1903 (Washington: GPO, 1903), gives the following summary for Balch: Graduated third in his class at the Military Academy and was given a brevet as second lieutenant on 1 July 1851. Made second lieutenant on 26 February 1853 and promoted to first lieutenant on 1 July 1854. Promoted to captain on 1 November 1861.Given brevets to major and lieutenant colonel on 13 March 1865 (the date a great many brevet promotions were awarded). He resigned on 1 December 1865 and died on 15 April 1894. 5. Balch did play a temporary role in management of the Springfield

Armory during the transition from civilian management under

Mr. George Dwight to military management under Captain Dyer.

He is known to have signed some Springfield Armory letters and during the transition, on 16 August 1861, he wrote the Chief of

Ordnance recommending the services of Dwight be retained for a while as assistant superintendent. Vol. 32, B521, E20, RG 156. 6. Captain Whiteley had also served as Inspecting Officer from 1855 to 1858. 7. Vol. 21, page 155, E6, RG 156. 8. For a July 1861 example related to a problem with the Colt revolver design, see Charles W. Pate, “Colt’s ‘Cavalry Cylinder’ Model 1860

Army Revolvers,” Man At Arms, 30, no. 4 (August 2008). 9. Letter H398 of 1861, E21, RG 156. 10. Vol. 21, page 162, E6, RG 156. 11. Letter B535, vol. 32, E20, RG 156. In this letter Balch asked who was to inspect the Sharps carbines. Ripley answered on 22 August 1861 (vol. 21, page 214, E6, RG 156) saying Captain Whitley would do the inspection. 12. Vol. 21, 213, E6, RG 156. 13. Ibid., 216. 14. Ibid., 295, 296. 15. Letter B540 of 1861, vol. 32, E20, RG 156. 16. Vol. 21, 216, E6, RG 156. 17. Letter, B430 of 1862, 31 March 1862, Box 258, E21, RG 156. 18. He asked for a junior officer to assist him in inspection work at

Ames, 8 January 1862, Lieut./Capt. George T. Balch Letter-book, 10/26/1861–3/10/1862, 148 (hereafter Balch Letter-book), but the author could find no indication in Ordnance Department records that one was provided. 19. Balch Letter-book, 16, 26. 20. Vol. 21, 303, E6, RG 156. 21. Colt eventually reached that level of production but was slow in doing so. On 31 October 1861, Balch reported sending three hundred Colts to Washington Arsenal that day and said, “Col. Colt

I believe gives us his whole product, but after five weeks trial he has as yet failed to go beyond 600 pistols per week although he promised 1000. I shall believe he can come up to that when I have that number presented for inspection.” B822 of 1861, Box 243, RG 156. 22. The U.S. Army much preferred .44 caliber revolvers to those of .36 (“Navy”) caliber. The Savage was a .36 caliber pistol and in addition to it the Army purchased at this time some Remington and Starr .36 caliber pistols on the open market. Some 11mm

Lefaucheux pin-fire revolvers were bought in Europe but were very unpopular with the troops. 23. Balch Letter-book, 136. At the direction of the secretary of war,

General Ripley had given Poultney & Trimble a contract for ten thousand Smith carbines on 27 August 1861 to be delivered at the