The Cupola Christopher Newport University 2014 – 2015

The title of our online undergraduate research journal references the architectural feature that tops Trible Library, thus honoring Cupola authors as the preeminent student researchers at CNU.

In support of its mission, CNU's Undergraduate and Graduate Research Committee (UGRC) honors and promotes up to six outstanding student research papers by publishing them in The Cupola. Student researchers published in The Cupola receive a cash award supported by the Douglas K. Gordon Endowed Undergraduate and Graduate Research Fund.

Submissions are judged based on:

• integration of research

• originality / creativity

• rhetorical qualities / style

• advancement of liberal learning

The Cupola Award is presented to students whose research papers were selected from the top papers submitted to the Undergraduate and Graduate Research Committee. Winners receive $500 and their paper published in The Cupola, CNU’s web based journal for undergraduate research. The top papers received the Douglas K. Gordon Cupola Award.

Research is the essential element of the scholar's craft. It is the means by which scholars pay forward into the fund of human knowledge the debt owed to their predecessors. At its best, research honors the past while enriching the future.

Dr. Richard M. Summerville CNU Provost 1982-1995, 2001-2007

2014 – 2015

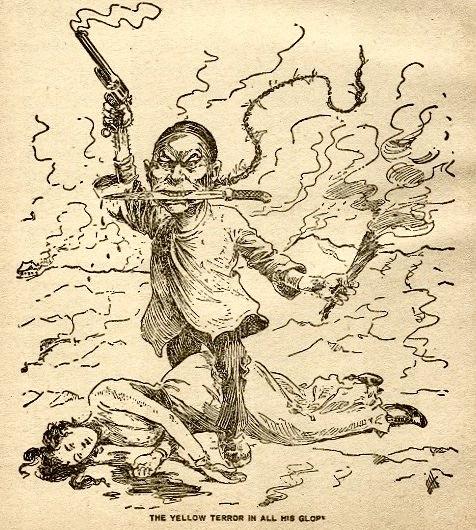

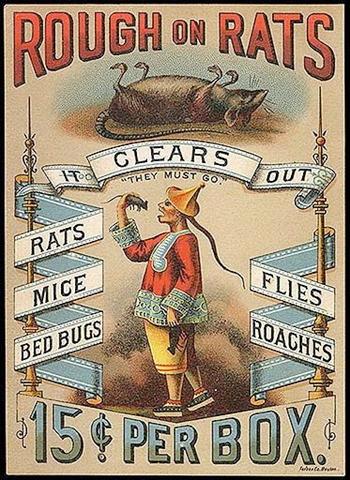

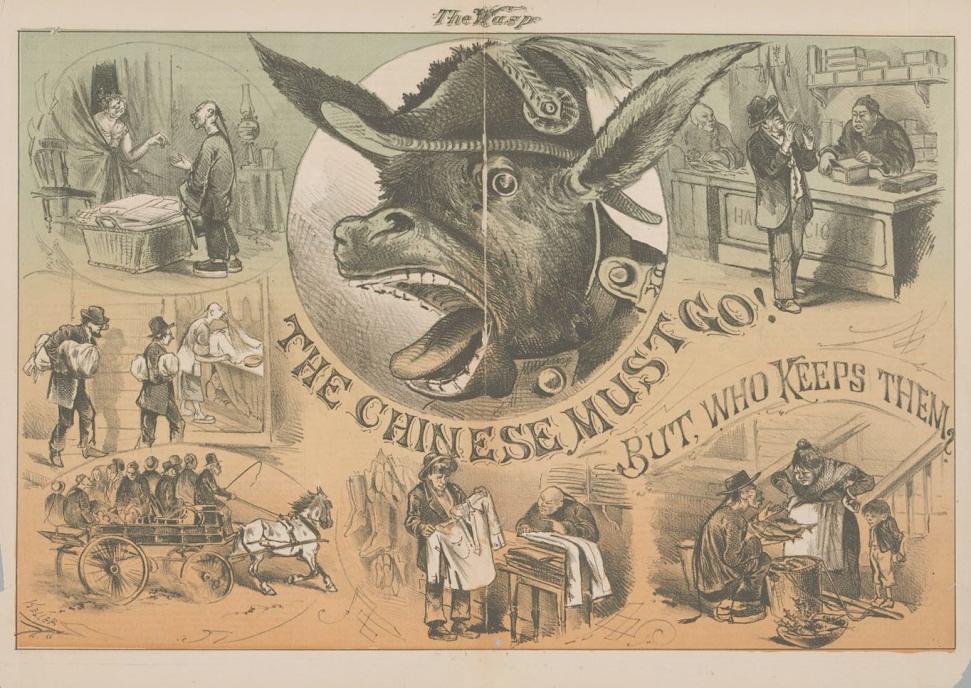

“ 'Who…Or What…Is He?': The Evolving Role of Popular Culture

in

Diplomatic Relations from the 'Yellow Peril' of the Late 1800s to the Early Years of the Cold War”

by Oliver Thomas

The Cupola

TABLE OF CONTENTS “From One Other to Another: 'Othered' Child Protagonists and Helpful Monsters” 1 – 18 by Rachel Condon Douglas K Gordon Award “Stealing the Opera in the Georgian Era: Tracing Michael Kelly and the Forty Thieves” 19 – 27 by Matthew Kelly Douglas K. Gordon Award “Visibility and Victimization: Transgender Youth, Social Media and Violence” 28 – 37 by Hayley Baugham “Reclaiming Center Stage: Britten's Canticle II” 38 – 53 by

“Unintentional Shipment of Species: Transporting Goods Damaging the Ecosystem?” 54 – 66 by Page Daniels

Callie Boone

and Perception

Sino-American 67 – 94

“Othered” Child Protagonists and Helpful Monsters

by Rachel Condon

sponsored by Dr. Jean Filetti (Department of English)

Author Biography

Rachel Condon is a student of English with a concentration in writing. The creation and telling of stories are among her greatest passions, and few stories interest her as much as those featuring the fantastic. She was the kid who went looking for monsters in the woods and found them in books (and maybe has not quite given up on the woods yet, either). Her alma mater is Atlee High School and is about to be Christopher Newport University. She aspires to be an author and write all the books she wishes she had had growing up.

Abstract

Eddie, from Adler’s Eddie’s Blue-Winged Dragon, is “othered” because of his cerebral palsy. He is preyed upon by school bullies and an ableist teacher. His monstrous ally is a dragon that embodies his desire for strength and beauty as well as his anxieties regarding communication and control. Brendan is the protagonist of Moore’s The Secret of Kells, and he is the only child monk in the abbey. He is made to feel inadequate and powerless by his overbearing uncle, and is not permitted to pursue his own interests. The fairy Aisling, though at first lethally threatening and always wild, becomes his playmate and encourages Brendan’s artistic endeavors. The tree-like monster of Ness’ A Monster Calls is a thing that walks between waking and dreaming and it comes for Conor, a boy isolated in part due to his mother’s cancer. He is harassed by a bully and failed by his father. Only with the monster’s help can he begin to put his life back together, and that depends on surviving his final encounter with it.

To be a child or teenager is a vulnerability based “otherness.” This vulnerability can be exacerbated by other circumstances, like disability, abuse, or trauma. In the story of the “othered” child protagonist and the helpful monster, the child begins the story in a disempowered and marginalized space s/he is “othered” during her/his greatest feelings of helplessness, s/he encounters her/his monster the ultimate expression of “the other” and through interaction with this greater “other,” s/he becomes empowered, and her/his feelings of marginalization decrease.

1 From One Other to Another:

There is a story-type that is not uncommon which deals with the powerless, marginalized human “other” and the helpful but dangerous, monstrous “other.” Perhaps the best “real” example is the Jewish legend of the golem, but the theme has found its way into many contemporary stories, too, particularly in those for children and young adults. There is something appealing in the story of the abused outlier and the creature of superhuman power. One particular variety of tales has become rather popular: the story of the “othered” child protagonist and the helpful monster. In these stories, the child protagonist begins the story in a disempowered and marginalized space he or she is effectively “othered” at the point of his or her greatest feelings of helplessness, he or she encounters his or her monster the ultimate expression of “the other” and through interaction with this greater “other,” he or she gradually becomes empowered, and his or her feelings of marginalization decrease. The texts Eddie’s Blue-Winged Dragon (Alder, 1988), The Secret of Kells (Moore, 2009), and A Monster Calls (Ness, 2011) all fall within this story-type. To help support the above theory, some relevant citations from “Monster Culture (Seven Theses)” by Jeffrey Jerome Cohen and “The Monster Chronicles: The Role of Children's Stories Featuring Monsters in Managing Childhood Fears and Promoting Empowerment” Michelle Alison Taylor have been included. Though Cohen’s and Taylor’s texts were used most often, there is further support found in On Monsters: An Unnatural History of Our Worst Fears by Stephen T. Asma, "In and Out of Otherness: Being and Not-being in Children's Literature"

by

Rosemary

Ross Johnston, Strangers: Gods and Monsters by Richard Kearney, and “Swaddling the Child in Children's Literature” by Joseph

Zornado.

Humanity has made a habit of hating and fearing that which it does not understand. This fear and hatred can lead to the marginalization the “othering” of individuals who are somehow unlike the majority (or a sizable and powerful minority) of their peers. These differences can be ability, age, temperament, or virtually any other trait or circumstance. Almost without exception, these “others” are either already without power or they are stripped of it. Outside of their former communities (or inside communities than cannot or will not protect them) and impotent, these “others” are quite frequently preyed upon by stronger and better integrated individuals. Among the most vulnerable of these “others” are those that are children and teenagers. Children and teenagers are physically weaker than adults, are not as developed mentally or emotionally, and are not given the same social status. These vulnerabilities are compounded when accompanied by another marginalized trait, such as disability, or another isolating condition, such as family troubles.

Yet there is another sort of “other” which, though just as hated and feared as the outlier mentioned above, is far from powerless. The monster has haunted human thought for as long as humans have existed. It takes many shapes and has many meanings, but it is always alien. The monster is the ultimate “other” and at the same time a hybrid space personified. A monster is never just one thing. Whether not animal nor human, not living nor dead, or not plant nor beast, monsters are all liminal beings. They walk a razor’s edge between binaries that human minds believe to be absolute. This trait can be as liberating as it is horrifying, as it offers a third option to

2

choosing between two apparently mutually exclusive identities. Most of all, monsters are powerful, and it is a power that impotent human “others” crave. Sometimes, they want it badly enough to call upon (or perhaps make) their own monsters.

Monsters rarely seem to appear when child protagonists are at their strongest, and almost never before the child has become a n “other.” Rather, monsters seem to come only at one’s darkest hour (literally or figuratively). They show up when the “othered” child protagonist is already beaten down by a bully, or a disability, or an overbearing guardian, or any number of troubles. The outcast child protagonist is at his or her lowest, and often loneliest, when his or her monster appears to him or her. A young outlier who is unable to overcome the obstacles of his or her everyday life does not have much in the way of a chance of surviving the arrival of a monster. On the other hand, a child “other” who is able to survive the arrival of a monster has a very good chance of overcoming the obstacles of his or her everyday life. If he or she can survive the monster, he or she can survive the abuse, his or her “otherness,” anything. This is the way of the story of the “othered” child and the helpful monster: he or she begins the story in a disempowered and marginalized space and when he or she is most helpless, his or her monster appears. Through interaction with the monster (the greater “other”) the “othered” child protagonist becomes empowered and his or her feelings of “otherness” decrease.

To be clear, interaction with the monster need not involve slaying it (in fact, it usually does not). The child protagonist c an survive his or her supernatural interaction by taming his or her monster, making a deal, winning its friendship, or a combination of the above. Through interaction with a being of such immense power and astonishing “otherness” as a monster, the child protagonist finds his or her own power and humanity (non-otherness; non-monstrousness), and walks away from the encounter stronger than before. He or she is now strong enough to stand up to perceived limitations, an overbearing guardian, or enormous loss.

The word monster is today used for all manner of things. A monster may be a particularly large animal, a person who has committed great evil, or a thing that lurks beneath a child’s bed at night. For the purposes of this essay, monster will be defined as a powerful and dangerous nonhuman being. The monsters encountered by the child protagonists in the analyzed stories are very different. The monsters are different because the child protagonists and their trials are different, and they therefore need different things from the monsters they encounter. Whatever power a given monster has, danger it poses, and hybrid traits it has are related to the desires or anxieties (or both) possessed by the child protagonist it encounters. Each monster is effectively custom -made for its child protagonist (or, each child protagonist is custom-made for his or her monster).

As with many story-types, the story of the marginalized child protagonist and the helpful monster follows a pattern. The child protagonist is aware of his or her “otherness” and the accompanying isolation and impotency, and it is at this point when the monster arrives. The monster’s first appearance presents itself as something threatening and uncontrollable, which marks it as a different sort

3

of being than the powerless child protagonist. At the same time, the monster’s “otherness” is made apparent. At the first interaction’s conclusion, the monster and the child protagonist come to an agreement that temporarily deflects any possible danger posed by the monster away from the child protagonist. The nature of the agreement depends on the intelligence of the monster and may be as complex as a deal or as simple as a reciprocated gesture of goodwill. After the agreement has been made, the monster will aid the child protagonist in some way (though this aid may have terrible consequences). There will be further interactions between the monster and child protagonist, frequently after instances where the child protagonist’s “otherness” has caused him or her trouble. The climax of the story involves the child protagonist overcoming a great obstacle with minimal or no help from the monster. In his or her triumph over the obstacle, the child protagonist comes into his or her own strength and no longer feels marginalized or impotent. Eddie, the child protagonist of Adler’s Eddie’s Blue-Winged Dragon, is a sixth-grader who is “othered” due to his cerebral palsy. Though he may be “picked last or not at all” for teams in gym class, it isn’t because other students are unaware of him (Adle r 60).

Cerebral palsy, or C.P., is a distinctive condition that causes physical disability. “Everybody in the school knew him [Eddie]. . . . having cerebral palsy made him ‘outstanding’” readers learn early in the story (Adler 12). Not all Eddie’s peers treat him poorly, but “it gall[s] him” to realize that some people “[don’t] think he [is] normal” because he happens to be disabled (Adler 132). Substitute gym teachers excuse him from activities “Without being asked” (Adler 131). Neighbors won’t “trust a kid with cerebral palsy to babysit” despite Eddie’s skill, and his best friend’s father asks Eddie’s friend if “a cripple [is] the best [he] can do for a friend” (Adler 16, 20). Eddie’s disability marks him, in the world’s eyes, as deficient or lesser.

The child-hero of Moore’s The Secret of Kells, Brendan, has a problem similar to Eddie’s. He is a young monk living within the confines of a walled-in monastery in medieval Ireland. Brendan is the only child monk at Kells, and is addressed simply by his first name rather than as Brother Brendan. The only two characters who acknow ledge his status as a monk are his uncle, Abbot Cellach, and Brother Aiden, the master illuminator and Brendan’s mentor (Moore Ch. 1, 2). The other, adult monks will occasionally poke fun at Brendan. While this is never done with any obvious malicious intent, Brendan’s facial expressions indicate quiet annoyance (Moore Ch. 1, 2).

There are children within the abbey walls that are roughly Brendan’s age, but he is not seen playing or interacting with them . He is a monk and he therefore has different responsibilities than those of his age-mates. However, he is also a child and is so regarded by his adult peers. Brendan is “othered” because he is in two apparently conflicting socially prescribed categories. He cannot fit in with the other monks because he is a child. He cannot fit in with the other children because he is a monk.

4

Brendan’s strict and solemn uncle runs the monastery and oversees the building of its massive walls, and he provides another trial for Brendan. Abbot Cellach intends for Brendan to run the monastery someday, and has little patience for Brendan’s childish failings. He demands much of his nephew and is unintentionally abusive, having either a task or a reprimand for Brendan nearly every time they meet. Cellach wants Brendan to focus on helping to build the walls, but Brendan is more interested in the work of the illuminators. He regularly gets into trouble for shirking other duties to help in the scriptorium. Cellach attempts to shape Brendan into the heir Cellach wishes Brendan to be rather than allow Brendan to develop his own skills and interests. To do this, Cellach relies primarily on the sort of psychological manipulation Joseph Zornado, a literature professor at Rhode Island College, calls “modern forms of swaddling” with the purpose of “breaking . . . the child’s will so that adults may form the child in their own image” (105-6). Cellach refuses to allow Brendan to follow his own interests and doesn’t make allowances for his natural impulse to play. Cellach also silences Brendan by cutting him off, even after Cellach has told his nephew, “I’m listening” (Moore Ch. 5). This last behavior appears to be a variation of what Zornado calls “befuddlement” which is “a process of confusion” created by contradiction (105). Claiming to be willing to listen to a child before interrupting him or her is just such a befuddling contradiction. Abbot Cellach exacerbates rather than alleviates Brendan’s feelings of isolation and “otherness.”

Conor O’Malley is the child protagonist of Ness’ A Monster Calls, and his sense of “otherness” is even greater than Brendan’s. He is “othered” because his mother has advanced cancer and his peers don’t know how to deal with that. After Conor’s (former) best friend, Lily, “told a few of her friends about Connor’s mum [having cancer]” word quickly got around school and “All of a sudden, the people [Conor had] thought were his friends would stop talking when he came over . . . He’d catch people whispering as he walked by . . . Even teachers would get a different look on their faces” (Ness 68). The school bully, Harry, begins harassing Conor after Conor “start[s] having the nightmare, the real nightmare . . . with the screaming and the falling, the nightmare he would never tell another living soul about” (Ness 19). The secret of the nightmare is what isolates and “others” Conor most of all, because it is an internalized “otherness.” Eddie does not feel bad for having C.P., nor does Brendan feel wrong for being a child monk. These are traits that prove inconvenient and alienating at times, but they do not cause the possessor to feel sinful the way Conor’s dream does. Conor is struggling with thoughts and emotions that make him feel like he is a monster.

People once considered the disabled monsters and subhuman beings (Asma 15). In Eddie’s time, some people just treat the disabled like monsters. In addition to the physical limitations and speech difficulties caused by his disability, Eddie has to deal with an ableist teacher and a trio school thugs. The readers first meet Eddie when he is mugged on his way to class by the school bullies Darrin, Richard, and Mack (Adler 10-12). When Eddie finds a dragon figurine in his best friend’s father’s pawn shop the next day, however, it changes everything.

5

A dragon is an “other,” a hybrid being. European dragons appear to be reptiles, which are more closely related to birds than mammals, but they have bat-like wings. One would suppose they would be cold-blooded, yet they breathe fire. Eddie’s dragon goes a step further by being an inanimate thing that becomes an animate creature. It is also fragile (having glass wings) in its inanimate state, but powerful when it is animate. The night after purchasing the dragon, it appears to Eddie in a dream with its “blue wings now as big as a hawk ’s . . . the brass body writhe[s] in snaky, sinewy curves . . . eyes, like red embers” (Adler 33). The dragon’s description sharply contrasts with Eddie’s, a boy critical of the way C.P. has shaped his body. Eddie is painfully aware “of his bum arm and leg” (Adler 24). He is also distressed by his “distorted mouth and droopy lip,” which he thinks is “revolting” (Adler 80). Appearances are not all that concern Eddie, and he often laments his physical weakness when suffering Darrin’s abuse. While briefly indulging in a fantasy, Eddie imagines “How great it would be if just once he could be strong enough to knock Darrin down” (Adler 32). Monsters do not always represent a child protagonist’s fear as Michelle Alison Taylor, occupational therapist and arts student, explains “[a] monster can be a metaphor for power and passion . . . children can love these terrifying creatures because they can also be comforted by them” (5-6). Eddie’s dragon is described as something powerful and awesome, a creature in full possession of the strength and grace Eddie craves.

There are two aspects of the dragon that reflect anxieties of Eddie’s rather than desires. The dragon has a fiery temper and is mute.

Eddie knows that he has an “explosive” temper and that his C.P. affects his speech (Adler 125). Sometimes in times of stress, the words he speaks “come out mush” (Adler 77). The dragon displays Eddie’s faults in distorted extremes. It embodies the threat of destructive rage and the loss of language at the same time that it promises liberating strength and terrible beauty.

Brendan meets his monster when Brother Aiden arrives at Kells with the Book of Iona, a book so beautifully illuminated that B rendan calls it “The work of angels” (Moore Ch.3). Brendan eagerly volunteers to help Aiden any way he can. At Aiden’s request, Brendan is persuaded to leave the walls of Kells and venture into the nearby wood for ink berries. It is there that Brendan encounters A isling.

The gender of Aisling, the helpful monster of The Secret of Kells, is never specified within the film and this is a very important detail. While Aisling can easily be read as genderqueer or otherwise of a non-binary gender, English lacks singular pronouns that are not gender specific. Aisling is likely a femandrogyne. Femandrogynes are not female, but they are more feminine than masculine. For simplicity’s sake, feminine pronouns will be used when referring to Aisling.

6

Aisling is a fairy, and unlike Eddie’s dragon, of human intelligence (Moore Ch.4). She has superhuman strength, the ability to climb sheer surfaces, shape shift (into a salmon, deer, and wolf), communicate with animals and the forest, and cast spells with her song and breath. Aisling is everything wild and untamable, and she claims the forest as her domain. She is both alluring and repellant to Brendan when the two first meet, for Aisling has both the absolute freedom he craves and is terrifyingly unpredic table. While she and Brendan are having their first conversation, Aisling continues to move about at impossible speeds (Moore Ch.4). Brendan can’t even look at who he’s talking to for long. Aisling is very much an “other” being: “difference made flesh…an incorporation of the Outside, the Beyond” (Cohen 7). Like all monsters, she is a liminal being that “refuses easy categorization” (Cohen 6). Not only is Aisling not a human, but she defies traditional gender categorization and can take the shape of several different species. Aisling is not strictly male nor female; she is neither human nor animal. Even Brendan refers to her kind (fairies) as “creatures” (Moore Ch.4). While Eddie’s dragon can shift from inanimate to animate, it is at least always a dragon. Aisling flies in the face of binary categories with her queer gender and capacity to shape shift. She is a child of the forest man has failed to tame, and could hardly be more different from the civilized, Catholic boy that Brendan is. On the other hand this difference goes both ways. It is easy to forget that “Strangers are almost always other to each other” (Kearney 3). This can be seen in Brendan’s struggle to explain the concepts of ink, pages, and books to Aisling (Moore Ch.4). Brendan does not understand Aisling, but neither does Aisling understand Brendan.

There is no magical forest for Conor to escape to. At home, he must deal with his mother’s illness and the side effects of he r chemotherapy. At school, he is friendless and preyed upon by a bully. Asleep, he is terrorized by a story his mind tells him again and again. It is at this point in his life that Conor O’Malley’s monster comes to him.

There isn’t a specific name for the type of monster Conor’s is. Rather, there are many names. When Conor a sks “Who are you [the monster], then?” the monster replies “I have had as many names as there are years to time itself! . . . I am this wild earth, come for you, Conor O’Malley” (Ness 31, 34). This is reflected in the fact that “the form [the monster] choos[es] most [often] to walk in” is a yew tree (Ness 136). The monster isn’t an ordinary yew tree, but one that can move and interact with the world. It is made of a colossal yew tree with “branches twist[ing] around one another . . . until they [form] two long arms and a second leg . . . The rest of the tree gather[ing] itself into a spine and then a torso . . . leaves weaving together to make a green, furry skin” (Ness 5). Conor’s monster is a plant that behaves like an animal.

Conor’s monster also acts a herald, in keeping with its title. Monster comes from “monstrum [which] is etymologically ‘that which reveals,’ ‘that which warns’” (Cohen 4). As evidenced by the symbolism of Conor’s monster’s chosen form, the healing yew, the monster is a living metaphor. Cohen says “Like a letter on the page, the monster always signifies something other than itself” and it needs only to be read (4). Conor’s monster comes to him because it already knows what will happen to Conor’s mother, just as Conor

7

does “deep in [his] heart” (Ness 167). It does not come to stop the inevitable, but to make sure Conor is well enough to weather the fallout.

The trait that most strongly marks the monster as an “other” is the nature of its very existence. Conor is never entirely cer tain whether or not the monster is real, or if it’s a figment of his imagination. The monster almost always interacts with Conor at 12:07 at night, and Conor will wake up from these encounters to conflicting signs. A window destroyed by the monster may now be i ntact, but the floor of his room will be covered in yew leaves (Ness 11). When Conor is not sleeping and the monster appears, he generally loses full consciousness of the outside world and no one else claims to see the monster. The monster’s interactions w ith Conor are certainly fantastic in nature. The monster, when telling stories, has the capacity to alter its and Conor’s surroundings so that Conor can see (and sometimes even interact) with the tale. When Conor is visited by the monster the second time, he tells himself “It’s only a dream” to which the monster responds “But what is a dream . . . Who is to say that it is not everything else that is the dream?” (Ness 30). The monster has a point, even ignoring the fact that dreams are considered sacred by many cultures, religions, and people. If Conor is interacting with the monster, listening to its stories, and accepting its aid, then the monster is as real as it needs to be.

Conor’s feelings about his monster’s destructive power are largely positive. Conor can see the potential benefits of having someone “thirty or forty feet” taller than him with “a head and teeth that could chomp him down in one bite” for an ally (Ness 30-1). Indeed, on their second meeting, the monster comments on the fact that Conor is “[thinking] I [the monster] have come to topple [Conor’s] enemies. Slay [Conor’s] dragons” (Ness 51). Conor isn’t intimidated by the monster’s power. Whenever Conor becomes concerned about the monster wrecking something, it’s tied at least in part to concern for other people or other people’s property. Conor asks the monster not to be destructive just once, and that’s only because he “[doesn’t] want [the monster] to wake [Conor’s] mum” which a yew tree busting through a wall would certainly do (Ness 29). In another instance, the monster takes a seat “plac[ing] its entire great weight on top of [Conor’s] grandma’s office” (Ness 137). This naturally makes Conor anxious, and “His heart [leaps] in his throat” because he believes his grandmother is already angry with him for his own act of destruction (Ness 137). When Conor believes the destruction to be contained to the world of the monster’s stories, however, he becomes downright enthusiastic.

Conor’s deepest desire is reflected in the monster’s ability to heal, though Conor doesn’t learn of this characteristic of the monster until it has visited him several times. Conor finds out that his mother’s latest medicine “is actually made from yew trees” soon after the monster has told him “The yew tree is the most important of all the healing trees . . . [all its parts] thrum and twist with life” (Ness 130, 105). More than anything, Conor wants his mother to recover. He knows that he doesn’t have the power to cure his mother’s cancer, but the monster might.

8

Though he is no more certain of the dragon’s reality than Conor is of his monster’s reality, Eddie is at first frightened by his dragon.

When the dragon fixes its gaze on Eddie, “[Eddie] gag[s] on his fear and pull[s] the [bed]cover over his head,” which is an understandable reaction from a sixth-grader (Adler 33). Fortunately for Eddie, he and his monster come to an agreement quickly. The dragon “snuggle[s] against his [Eddie’s] side. Its snaky head rest[s] trustingly right below Eddie’s cheek,” and all that is required of Eddie is that “With his good right hand, he dare[s] himself to touch its hide” for a bond to be made (Adler 34). Eddie’s drag on, his monster, is now more than willing to aid him.

Just like Eddie, Brendan is frightened of Aisling at first, despite the fact that she saves him and Pangar Bán (his cat friend) from a pack of wolves (Moore Ch.4). This fear is a reaction she encourages by threatening Brendan to make him leave the forest saying “If you [Brendan and Pangar] don’t, I’ll make the wolves get you! Raargh!” (Moore Ch.4). Aisling makes it clear that she believes Brendan has come to her forest “to spoil it” or was “sent here by [Brendan’s] family to get food” and that she wants Brendan and Pangar to “go right back where [they] came from” (Moore Ch.4). Brendan tries to defend himself against such accusations, saying he’s “[in the forest] to get things to make ink. I don’t [Brendan doesn’t] have a family,” (Moore Ch.4). Hearing this, Aisling becomes instantly sympathetic, saying “I’m [Aisling is] alone, too” (Moore Ch.4). In discussing the way children relate to stories about monsters, Taylor notes that “[such stories] may even engender a sense of sympathy and responsibility toward the monster who was possibly abandoned or abused” (19). Taylor is speaking of real children and fictional monsters, but her observation appears to apply to Aisling and Brendan as well. Aisling is the last of her people (a sort of involuntary abandonment on their part), and Brendan is being raised by an abusive guardian. If both Aisling and Brendan see the other as an “other” as Kearney suggests, their shared sense of orphanage may lessen that. At any rate, this display of sympathy causes Brendan to fear Aisling less. He becomes bold enough to ask for her help in finding berries for ink. Aisling agrees provided that he and Pangar “promise never to come into [Aisling’s] forest again” (Moore Ch.4). With some hesitance, Brendan promises, and so he and his monster have made their agreement.

The agreement between Brendan and Aisling does not start out quite so cozy as that between Eddie and his dragon; Aisling doesn’t even tell Brendan her name at first. However, as Aisling goes about helping Brendan gather berries and showing him her forest, the two begin a childish game of one-upmanship which breaks the tension between them. Brendan tries to impress Aisling by describing the Book of Iona, describing it as “the most incredible book in the whole world . . , it will turn darkness into light. Wait until you see it;” Aisling responds by telling him “Wait until you see the rest of my forest” (Moore Ch.4). The two have other small contests of agility, speed, and climbing ability, all of which Brendan loses. It is the playing of the game, however, and not its outcome that is important. The child protagonist and his monster have become friends: by the time Brendan is ready to go home to Kells, Aisling decides that Brendan “can visit the forest again, if [he] like[s]. And Pangar can come, too” (Moore Ch.5). Brendan takes Aisling up on this offer after beginning his illuminating work under Aiden (both activities unknown to Cellach). Brendan frequently sneaks out into

9

the woods with drawing materials to show Aisling his artwork. Art is Brendan’s only source of escape outside of the woods, and he is eager to share it with his friend. Aisling appreciates the creativity that Brendan’s uncle does not and supports Brendan’s artistic endeavors.

Unlike Eddie and Brendan, Conor isn’t afraid of his monster when the two first meet. The monster attempts to intimidate Conor as Aisling does Brendan, but with much less success. When the monster appears at his window, all Conor feels is “a growing disappointment” (Ness 8). Though the monster’s “mouth roar[s] open to eat [Conor] alive,” Conor is able to deflect any real danger by sheer apathy (Ness 9). It is not until their second meeting that Conor and his monster reach their agreement. The terms of the agreement are that the monster “will tell [Conor] three stories. Three tales from when [the monster] walked before” and Conor “will tell [the monster] a fourth” or the monster “will eat [Conor] alive” (Ness 35-7). The trouble for Conor is that the monster doesn’t want just any story. The monster wants Conor to tell it “ the truth,” which “is the thing [Conor is] most afraid of” (Ness 36). The monster wants Conor to tell it the nightmare.

Conor’s relationship with his monster is a complicated one. Eddie discovers fairly quickly that his dragon is like a pet, and Brendan considers Aisling a friend after spending most of a day in the forest with her (Adler 34, Moore Ch.5). Unlike the other children and monsters, it takes Conor and his monster a while to decide where to place each other. The meeting between Conor and his monster was no accident: the monster “[has] come walking” because Conor “[has] called for [the monster]” (Ness 51). Conor finds this baffling because he has no conscious knowledge of calling for the monster. He sees the monster as “just a tree” and doesn’t understand why it can’t “just leave [Conor] alone” (Ness 50). For its part, the monster is just as confused by Conor’s behavior and the fact that “Nothing [the monster] do[es] seems to make [Conor] frightened of [it]” (Ness 50). The monster does attempt intimidation throughout the book, it physically restrains Conor, and sometimes lands him in a lot of trouble. However, the monster is at times almost paternal, be it by making a nest of leaves for Conor to sleep in or reprimanding him for using sarcasm (Ness 190, 49). It is not a perfectly straight line of progression, but the monster’s relationship with Conor changes throughout the text. The monster’s role in Conor’s life changes, in time, from adversary to teacher to healer to friend.

Enticing as it may seem, a monster’s aid often comes at a price. In the case of Eddie and his dragon, that price is control. There is a type of monster called “accidental monsters” because they “are dangerous . . . but not intentionally so” (Asma 13). This is the case with Eddie’s dragon, which has the power necessary to avenge any wrongs committed against Eddie, but it lacks the intelligence to keep from going too far. When Darrin embarrasses Eddie in front of a girl he likes, Eddie thoughtlessly says, “I wish he’d [D arrin would] drop dead” (Alder 39). Eddie then notices that the dragon has climbed out of his backpack and is pursuing Darrin. Darrin jams

10

his finger (Alder 40). Eddie isn’t quite willing to believe that he actually saw his dragon attack someone in waking life. As the people who anger him continue to suffer seemingly random misfortunes, however, Eddie begins to seriously suspect his dragon.

The dragon’s acts of violence are very clearly disproportionate to the actions that trigger them, and Eddie knows this: “a li ttle nip or scare [is] enough to even up the score with an enemy. Blood and broken bones [are] wrong, very, very wrong” (Adler 93). However, at the same time that the dragon is out of control, having it gives the illusion of control. The dragon’s might is particularly alluring to those like Eddie’s little sister, Mina, who “can’t kick anybody. So [Mina] need[s] [the dragon] to get people back for [her]” though she returns the dragon in fear of its power later (Adler 79). In moments of rage, Eddie himself gives into the temptation to “sic the dragon” on those who have hurt him (Adler 89).

This attraction is far from uncommon. Jeffery Jerome Cohen says of monsters that “fantasies of aggression . . . are allowed s afe expression in a . . . liminal space. Escapist delight gives way to horror only when the monster threatens to overstep these boundaries” (17). It could be argued that the degree to which boundaries are violated also impacts when (or even if) horror will set in. A portable dragon that can frighten enemies makes for a cute pet; a portable dragon capable of mass destruction and potential manslaughter is terrifying.

Brendan’s acceptance of Aisling’s aid and favor has no obvious drawbacks, unlike the relationships between Eddie and his drag on and Conor and his monster. The only real risk Brendan takes when going into the forest to visit Aisling is his uncle finding out. Brendan would be punished, but he wouldn’t have to worry about Aisling pushing a rock over on Cellach in retaliation. The fact that A isling is much more intelligent than Eddie’s dragon accounts for this in part, but not entirely, seeing as Conor’s monster appears just as smart as Aisling. Another factor appears to be the sharing (or not) of a major flaw, or a monster’s ability to manipulate such a flaw.

Brendan’s major flaws are his lack of confidence and his subservience, which are not traits that appear to hinder Aisling. Conor’s major flaw is his current inability to handle his grief which can, with his monster’s direction, explode into episodes of destructive rage. Because Conor’s monster doesn’t share Conor’s flaw, it can choose when and where to unleash Conor’s rage. Eddie and his dragon, however, both have a tendency to lose their tempers. When Eddie and his dragon lash out, the former doesn’t think and the later can’t

The prices Conor pays for the monster’s aid vary. Like Eddie, Conor must give up control in two of four major instances in wh ich his monster aids him. Unlike Eddie, Conor is only horrified by what he has done under the monster’s influence once: when he destroys his grandmother’s sitting room (Ness 114-6). In one instance, Conor must give up his safety as the monster forces him to complete his great obstacle (Ness 172). Eddie expresses regret for the actions of (himself and) his dragon, even though he chooses to retrieve it in the end. Conor, by the end of the story, has no real regrets about what he has done with the monster’s help.

11

The monster helps Conor primarily by telling him stories. Conor questions how helpful this is likely to be, but the monster assures him that “Stories are the wildest things of all Stories chase and bite and hunt” (Ness 35). The way the monster tells stories, they come to life. When the monster tells its second tale, a story about an apothecary and a parson, Conor is even able to “join in” and helps destroy the parson’s house at the end (Ness 110). The monster tells Conor destruction “ is most satisfying” and Conor “disappear[s] into a frenzy of destruction . . . Conor scream[s] until he [is] hoarse, smashe[s] until his arms [are] sore, roar[s] until he [is] nearly falling down with exhaustion” (Ness 110-1). He finds that “The monster [is] right. [Destruction is] very satisfying” (Ness 111). When the story truly ends and the monster leaves, however, Conor finds that he has wreaked at least as much havoc on his grandmother’s sitting room as on the parson’s house. Conor’s grandmother almost stops speaking to Conor entirely after the event, causing Conor to come to the erroneous (but not unreasonable) conclusion that his actions are the reason behind her silence (Ness 199). This causes Conor to feel even more alone than before. Stories are wild things indeed, especially wh en told by a monster to a grieving boy.

Another time the monster helps Conor is when his abuser, the bully Harry, does “the very worst thing [Harry] can do to [Conor]” (Ness 144). Harry decides that he will “no longer see [Conor],” and treats Conor as though he doesn’t exist (Ness 145). Conor is already alienated from his peers who “[look] away, like it [is] too embarrassing or painful to actually look at [Conor] directly” (Ness 151). To be completely ignored would be too great a social loss to endure. Johnston postulates “that the ultimate ‘otherness’ of children’s literature is . . . otherness of non-being” (45). Conor is already anxious of his mother’s impending death. The idea of his own social non-being is horrifying because, as the monster asks Conor, “if no one sees you are you really there at all?” (Ness 146).

It is at this time that the monster chooses to tell Conor the third story, a story about an “invisible man who [has] grown tired of being unseen” (Ness 146). Conor confronts Harry, shouting “You don’t see me?” to which Harry responds “I see nothing” (Ness 1512). What happens next is left deliberately ambiguous. Conor is the only one who sees the monster beat Harry up; the other students see Conor beat Harry up (Ness 156). Either way, the students believe (rightly or wrongly) that Conor beat Harry into the hospital (Ness 154). The monster warns Conor that “There are worse things than being invisible” after it and/or Conor is done with Harry (Ness 158). Conor finds this to be true because while his classmates “all [see] him now . . . he [is] further away than ever” from everyone but his (possibly ex-)ex-best friend, Lily (Ness 158, 162). Worse than being invisible is being a monster, and that’s exactly what Conor feels like.

After a particularly nasty encounter with Eddie’s personal tormenters, Darrin and his two goons, Eddie also enlists the aid of his monster. Eddie calls on his dragon and tells it to “Get those guys [the bullies] . . . You get them and make them sorry,” (Alder 115).

Eddie dreams of his dragon heaving flames on the bullies’ secret hideout in the woods, and wakes up the next morning to find that the

12

woods have been burned down (Alder 116-117). It is at this point that Eddie realizes the full price of a monster’s aid, and it scares him. Eddie decides that he cannot “trust himself to own a deadly weapon” and gives the dragon back to the store he got it from (Alder 123). Cohen hypothesizes that even Eddie’s “fear of the monster is really a kind of desire” because “the monster can function as an alter ego, as an alluring projection of (an Other) self” (Cohen 16-17). To be sure, returning the dragon has its own price because Eddie and his dragon have formed a bond. The night after giving his dragon up, Eddie dreams of it searching for him and “fe[els] as if he were missing part of himself” (Alder 128). The dragon is even more of an “other” than Eddie is, and he is losing a kindred spirit. For good or for ill, Eddie has seen that the dragon is a reflection of his desires and faults. To try to give it up is to try to run from a piece of himself.

Running from his major flaw, his temper, will not do Eddie any good. Eddie realizes that “if we face what we are afraid of, w e will emerge stronger than if we ignore it,” (Taylor 29). Eddie needs to confront his struggle with self-control head on if he is to conquer it. He cannot merely avoid power, but must become empowered and so be able to master himself.

The great obstacle that Eddie must overcome without his monster’s help takes the form of an essay and speech contest. While he has the option, due to his C.P., to have someone else read the essay he wrote aloud for him, Eddie chooses to read it himself despite being advised against it by his teacher (Adler 136). This is a significant step toward growth because Eddie’s trouble with controlling his speech parallels his struggle with controlling his temper. Eddie’s anger is one of those stressors that occasionally “[breaks] down all his carefully built-up muscle control” and makes his speech unintelligible (Alder 87). He must also exercise an element of self-control in pacing himself while reading to be sure he does not go so fast that his audience cannot understand him.

Winning the contest is, for Eddie, about being understood. Several times throughout the book, Eddie feels “othered” by peoples’ inability (or in some cases unwillingness) to understand his speech. Eddie is outraged when his teacher puts him on the spot to correct a paragraph in class, but then doesn’t listen well enough to hear what he’s actually saying (Adler 87). More than being just a moment of ill-treatment, the incident reawakens an anxiety in Eddie. He asks his best friend, “So how am I going to get to college? How am I going to be a psychologist if [patients] can’t figure out what I’m telling them?” (Adler 89). The silence of the dragon, its inability to express itself, reflects this fear. There is a point when the dragon grows depressed, and its only means of sharing this is “A great sadness [coming] from the dragon, like body heat” when it visits Eddie at night (Adler 99-100). Even when Eddie asks it, “What’s the matter?” he “[doesn’t] expect an answer” (Adler 99). It would be easy, but disastrous for his ambitions, for Eddie to allow himself to become a being like his dragon full of rage and silence.

13

To prepare himself, Eddie practices for hours with the tape recorder in the school library, going over his speech again and a gain. As Eddie carefully reads his essay “slow[ly] and give[s] every word its due,” he finds that he can successfully complete the task (Adler 140). He wins the contest and learns that practice breeds control, and that he can make himself be understood.

Brendan’s great obstacle is a two part task. The time for Brendan’s great obstacle comes when he must, to unleash his full potential as an illuminator, retrieve a magnifying crystal known as the Eye of Crom Cruach. Brendan knows there is a cave of Crom in the woods and attempts to sneak off to find the crystal, but is stopped by Cellach. Cellach decides he has had enough of Brendan’s sneaking off and forbids him to continue his studies saying, “No more excursions, no more scriptorium, and no more Brother Aiden” (Moore C h.7).

To Cellach’s astonishment, Brendan tells his overbearing uncle “No” (Moore Ch.7). For his defiance, Brendan is locked in his tower. Openly disobeying a guardian may seem like a small thing for a child to do, and it would be except for the psychological abus e Brendan has endured under Cellach. As it is, Brendan’s defiance is a sign of significant growth and therefore the first part of Brendan’s great obstacle.

Aisling helps Brendan twice during his great obstacle. The first time she aids Brendan is in unlocking the tower to allow him to escape, which she does by following the diagrams Brendan has drawn. The skills Brendan has learned in the scriptorium allow him to communicate the layout of the tower and exactly what needs to be done. His art, which has allowed him a metaphorical escape from everyday life, now helps Brendan literally escape the confinement his uncle has placed him in.

Aisling’s second instance of aid does not come so readily as the first. When she hears that Brendan wants to search Crom’s cave for the crystal, she is horrified and expresses immediate regret for releasing Brendan from his tower. Aisling is terribly afraid of Crom Cruach, who she calls “the Dark One,” and very reluctant to take Brendan to the cave that holds both Crom and its Eye (Moore Ch.4). Brendan explains to Aisling that “if [Brendan doesn’t] try [to get the crystal], the book [of Iona] will never be complete” (Moore Ch.7). This moves Aisling, who believes in Brendan’s dream. She opens a passageway to Crom’s cave, but she is physically inca pable of doing more (Moore Ch.8). Brendan will receive no more aid from his monster for the duration of his great obstacle.

In order to get the crystal, Brendan must defeat the massive, leviathan-like Crom Cruach with nothing more than a piece of chalk. It at first appears to be a hopeless endeavor, but Brendan discovers that he can draw lines that act as solid barriers. Brendan’s creativity and skills honed as an apprentice illuminator are what saves him, and he is able to trap Crom in a drawing and wrest the Eye away from it (Moore Ch.8). Brendan awakens the next morning inside the cave of Crom Cruach, Eye in hand, beneath a carving of Crom that is missing an Eye (Moore Ch.8). This could easily be interpreted to mean Brendan merely dreamt up his encounter with the Dark One.

14

Even if this is the case, there is psychological truth to the second half of Brendan’s obstacle: his subconscious created the danger of Crom, and then responded to it with an illuminator’s tool.

Conor is offered no way out of or tools to help with his great obstacle. Conor’s great obstacle is thrust upon him after he learns that his mother’s cancer has spread too far, too fast. The medicine made from yew trees didn’t work and “there aren’t any more treatments” (Ness 166). Outraged, Connor confronts his monster and demands that it heal his mother. His monster explains that “[It] did not come to heal [Conor’s mother] . . . [It] came to heal [Conor]” (Ness 172). It is then that the monster decides “it is time . . . for the fourth tale” (Ness 172). It is time for Conor to tell the story of his nightmare and to speak his truth. His monster does not help Conor complete his great obstacle, but forces him to face it.

The monster takes Conor into his nightmare, into “the middle of a cold darkness, one that had followed Conor . . . ever since forever, it felt like, the nightmare had been there . . . cutting him off, making him alone” (Ness 173). This is the nightmare that “others” Conor more than anything else and makes him feel like a monster. In it, Conor’s mother is seized by “The real monster, the one [Conor is] properly afraid of . . . formed of cloud and ash and dark flames . . . and flashing teeth that would eat [Conor’s] mother alive” and Conor catches her hands in his (Ness 179). Conor holds on to his mother’s hands until “the nig htmare reach[es] its most perfect moment . . . And [Conor’s] mother [falls]” (Ness 181).

His mother falling is not what makes Conor’s nightmare so awful, it is the fact that he “ let[s] her go” because “[Conor] wanted her to go” (Ness 187). In order for Conor to leave the nightmare, Conor needs to tell the monster why he let his mother go. It is such a terrible truth that Conor at first refuses to speak it, even knowing the nightmare will kill him if he doesn’t. It is at the climax of his great obstacle that Connor finally says, “I can’t stand it anymore! . . . I can’t stand knowing that [his mother will] go! I just want it to be over!” (Ness 188). By speaking the truth, Conor is freed from his nightmare and his great obstacle is completed.

With his great obstacle overcome, Eddie has found his own power and now feels “strong enough to fight his own battles without any help from magic dragons” (Adler 143). Now that Eddie does not need his dragon to feel strong, he is ready to reclaim it because “he and the dragon [are] bound together,” and Eddie knows he can control himself (Adler 143). If Eddie can control himself, speech and anger both, then he can control his monster.

Much like Eddie, triumphing over his obstacle gives Brendan a newfound sense of contr ol. In Brendan’s case this control is the power and freedom to choose his own path in life. With the Eye in his possession, Brendan is ready to complete his training. Having already confronted both Cellach and Crom, Brendan has discovered that he is willing to pursue his dream regardless of the cost to himself. He

15

embraces his role as an apprentice illuminator and fully dedicates his time to mastering his craft. The other monks come to admire Brendan’s skill and frequently visit the scriptorium to watch him work. Brendan is no longer “othered,” but celebrated.

Eddie and Brendan are ready to be (re)integrated into their social worlds the moment they complete their respective obstacles . This is not the case with Conor. His obstacle is the largest hurdle he has had to overcome, but he still feels like a monster. Conor still needs to be healed, and that is why his monster is still there. Crying, Conor explains that what is making him feel sinful and monstrous is that he “[doesn’t] mean it, though [letting his mother go] . . . Now [Conor’s mother is] going to die and it’s [Conor’s] fault!” (Ness 190). That is a heavy and lonely burden for a thirteen year-old boy to bear. Conor’s monster explains that Conor’s feelings aren’t monstrous at all. Conor is “merely wishing for the end of pain . . . to how it isolate[s Conor]. It is the most human wish of all” (Ness 191). It is now, after his great obstacle, that the monster helps Conor best. It gives Conor what he needs to reintegrate into human society by telling him “What [Conor] think[s] is not important. It is only important what [Conor] do[es]” (Ness 191). Conor is now ready to endure whatever comes next because he is no longer a monster, merely human.

Eddie went to reclaim his dragon when he ceased to feel like an “other,” but the story does not end so happily for Aisling. Even if viewers assume Brendan took time out of his training schedule to visit his monstrous friend, there comes a point when Brendan must flee Kells and the forest Aisling calls her own. He returns many years later as a grown man, and finds Aisling again in her wolf shape (Moore Ch.11). They have not forgotten each other, and she leads him past their childhood play places to the abbey. For one brief moment, she shows herself in her fairy form before disappearing, and she is still a child. Aisling leads Brendan to his old home where there are other humans, but does not join him. She is a monster: not human nor animal, not male nor female, not young nor old. She is the last of her people, and there will never be a place for her as anything other than an “other.”

The monster’s fate after Conor begins to no longer be an “other” is somewhat similar to Aisling’s in that it will not remain with Conor indefinitely. While viewers don’t really know how Aisling feels about her perpetual “otherness,” Conor’s monster doesn’t seem to mind returning to whatever space it came from, speaking of the “last steps of [its] walking” frankly (Ness 193). Conor, on the other hand, isn’t ready for his monster to leave by the end of the story. In the hospital Conor asks if “[It will] stay until…[Conor’s mother dies]” to which it responds “I will stay” (Ness 204). A monster cannot escape its “otherness” and join human society. Conor is going to lose his healer and his mother both, “But not this moment Not just yet” (Ness 205).

In the story of the “othered” child protagonist and the helpful monster, the monster appears to the child protagonist when he or she at the point of his or her greatest feelings of helplessness and marginalization. The monster shows itself to be uncontrollable and usually frightening in its first encounter with the child protagonist, and in possession of powers related to the child protagonist’s desires and

16

anxieties. The initial interaction with the monster acts as a catalyst, setting off a chain of events that ultimately lead to the child protagonist’s (re)integration into society. For the child protagonist to come into his or her own power, he or she must make an agreement with his or her monster, receive the monster’s aid, and finally overcome a personal obstacle with little to no help form his or her monster. Upon triumphing over his or her great obstacle, the child protagonist’s feelings of “otherness” decrease. He or she has survived his or her monster, and he or she has survived his or her great obstacle without his or her monster’s help. The child protagonist is now ready to successfully fight his or her own battles in life while fully integrated into human society.

17

Works Cited

Adler, C. S. Eddie's Blue-Winged Dragon. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1988. Print.

Asma, Stephen T. On Monsters: An Unnatural History of Our Worst Fears. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2009. Print.

Cohen, Jeffrey J. Monster Theory: Reading Culture . Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 1996. Print.

Johnston, Rosemary Ross. "In and Out of Otherness: Being and Not-being in Children's Literature." Neohelicon 36.1 (2009): 45-54. ProQuest. Web. 12 De. 2014.

Kearney, Richard. Strangers, Gods, and Monsters: Interpreting Otherness. London: Routledge, 2003. Print.

The Secret of Kells. Dir. Tomm Moore and Nora Twomey. Perf. Brendan Gleeson, Mick Lally, Evan McGuire, and Christen Mooney. Optimum Releasing Ltd., 2010. DVD.

Ness, Patrick, Jim Kay, and Siobhan Dowd. A Monster Calls. Somerville, MA: Candlewick, 2011. Print.

Taylor, Michelle A. "The Monster Chronicles : The Role of Children’s Stories Featuring Monsters in Managing Childhood Fears a nd Promoting Empowerment." Thesis. Queensland University of Technology, 2010. QUT EPrints. Queensland University of Technology, 27 Sept. 2010. Web. 12 Dec. 2014.

Zornado, Joseph. "Swaddling the Child in Children's Literature." Children's Literature Association Quarterly 22.3 (1997): 105-12. Project MUSE. Web. 12 Dec. 2014.

18

Stealing the Opera in the Georgian Era: Tracing Michael Kelly and the Forty Thieves

by Matthew Kelly

sponsored by Dr. Danielle Ward-Griffin (Department of Music)

Author Biography

Matt Kelly is graduating summa cum laude from Christopher Newport University with a Bacehlor of Music with Distinction in Vocal Performance and a minor in Leadership Studies. Mr. Kelly was part of the President’s Leadership Program and the Honors Program and holds a Service Distinction. This summer he will perform in 44 performances with the Ohio Light Opera Company then head straight to Indiana where he will begin studies for a Master of Sacred Music degree at the University of Notre Dame. A musician equally comfortable onstage and in the stacks, Matthew Kelly first encountered Michael Kelly when preparing to sing the role of Don Basilio/Curzio and decided to further his studies of the composer while browsing the Josephine L. Hughes collection. This pap er was presented at the 2015 Paideia conference where Matthew Kelly sang “Ah! What is the Bosom’s commotion” accompanied by Dr. Danielle Ward-Griffin on piano.

Abstract

The Josephine L. Hughes Collection (JLH) is home to rare American music, providing a glimpse into the musical life of the Ame rican parlor in the South. One might be surprised to discover the Georgian era opera aria, “Ah! What is the Bosom’s Commotion” from The Forty Thieves by Michael Kelly in the collection. This song provides a point of departure into the life of a musician and a period of music that has almost entirely escaped academic attention. A prolific composer, performer, producer, and publisher at the famous Theatre Royal Drury Lane, Michael Kelly’s contribution to opera in the Georgian era deserves attention.

Drawing upon Kelly’s memoirs and clues found in the score, this paper pieces together the history of the aria from its inspiration and performance through its printing and arrival into an American collection. The work’s premiere coincides with a period of great mourning in Kelly’s life, which I argue is expressed in the drama of the aria. Furthermore, based on first person accounts of Kelly’s singing, I demonstrate how he used various compositional techniques to highlight his own vocal strengths. Finally, I situate the score in the context of music publishing in the Georgian era and suggest that the copy of “Ah! What is the Bosom’s commotion” contained in the JLH Collection is likely a bootleg version printed down the street from Kelly’s own shop. Developing upon Girdham’s work on Kelly’s predecessor, Stephen Storace, this paper provides academic entry into one of Georgian opera’s most active men.

19

The Josephine L. Hughes Collection (JLH) is home to many rare pieces and editions that provide a glimpse into the musical lif e of the American parlor in the South.1 While the American compositions and publications comprise the backbone of the collection, a sense of the performing tradition in the United States can be gained by examining the international works. One might be surprised to find the music of a Georgian Era opera composer in the collection. English opera in the Georgina Era (1714-1837 or the period between Handel and Gilbert and Sullivan) is all but entirely exempt from the Western performing canon and is rarely studied. The JLH collection is fortunate to possess music by Michael Kelly including, “Ah! What is the Bosom’s Commotion” from The Forty Thieves, a setting of Hamlet’s letter to Ophelia, “I Fondly Turn to Thee Mary,” “Rest! Warrior Rest,” “Flora McDonald,” “Here’s a Health to Thee,” and the most famous of his compositions, The Woodpecker, with text by Thomas Moore. In particular, “Ah! What is the Bosom’s commotion” provides a point of departure into the life of the prolific composer and performer as well as the operatic climate in which he lived.2 Michael Kelly left behind an extremely detailed two volume memoir that helps place the song in its historical context and offers many insights into the musical tradition from which it is derived. A detailed look into Kelly’s memoirs and the score in the JLH collection uncovers hidden secrets of the aria’s journey from the mind of the composer to the printing press.

Michael Kelly (1762-1826) was an Irish born tenor who spent most of his operatic career in London.3 After getting his start performing abroad in continental Europe, even premiering the comic roles of the conniving Don Basilio and the very incompetent, stuttering lawyer Don Curzio in Le nozze di Figaro by Mozart, Kelly spent the majority of his musical career in London at the Theatre Royal Drury Lane, the most highly regarded opera house London after Covent Garden. Michael Kelly had his hands on almost every aspect of the opera: he was the leading tenor at Drury Lane for multiple decades, allegedly composed more than 60 operas, produced many shows, managed the Italian opera, procured French operas for the English stage, and even ran a music publishing company at 9 Pall Mall. Though he was a prolific composer, he is remembered today almost exclusively for premiering Don Curzio.4

Recalling Kelly through his compositions, however, allows deeper insights into the man’s life, with “Ah! What is the Bosom’s commotion” revealing a unique perspective on Kelly’s many talents. The Forty Thieves premiered at the Theatre Royal Drury Lane in April 1806. Receiving a very brief mention in his memoirs, it appears The Forty Thieves was an average work for Kelly. As Kelly was a popular and prolific composer in his day, one might therefore take The Forty Thieves to be representative of the Georgian Opera era

1 Amy Boykin, “Treasure Trove of American Sheet Music: The Josephine L. Hughes Collection,” Virginia Libraries 50, no. 4 (Fall 2004): 5, accessed March 16, 2015.

2 Michael Kelly, “Ah! What is the Bosom’s commotion,” in The Forty Thieves (London: C. Christmas, c1806).

3 Michael Kelly, Reminiscences of Michael Kelly of the King’s Theatre and Theatre Royal Drury Lane (New York: Da Capo Press, 1968).

4 Walter Monfried, “Mozart’s Irish Singer Friend: Recalling Michael Kelly, Composer of Wines and Music, Who Dared to Disagree With the Master in Interpreting a Figaro Role but Won an Emperor’s Approval,” The Milwaukee Journal, May 15, 1957, accessed May 1, 2015, https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1499&dat=19570515&id=A_BQAAAAIBAJ&sjid=5SUEAAAAIBAJ&pg=7240,3053784 &hl=en.

20

as well. According to the composer it was a “splendid spectacle” with a “very great run.”5 Kelly notes that the spectacle included acting, singing, and dancing by the main character Morgiana, played by a Miss Decamp. The subtitle on the score reads “sung by Mr. Kelly in the Grand Dramatic Romance of The Forty Thieves.”6 As this aria is sung to Morgiana, it is likely that Kelly was playing the male lead opposite Miss Decamp. According to musicologist Jane Girdham, it is very difficult to distinguish between plays and operas of this era in British theater.7 Neither critics, composers, nor publishers were consistent in the terms they assigned to stage works. Operas contained spoken dialogue (much like the German singspiel) and plays traditionally contained music. Based on Kelly’s description of The Forty Thieves as a “splendid” spectacle and the description given in the title, the work can be best described using the terms of the Georgian era as a “musical spectacle” or “musical romance.”8 According to Girdham, the classifications assigned in the Georgian era typically contained the word “opera” or “musical” and then some sort of modifier such as comic, farce, romance, drama, or entertainment.9 The modifier is there simply to suggest themes in the work, thus the exotic them es in The Forty Thieves might have led to its classification as a spectacle.

The Forty Thieves is based on the folktale, “Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves” from the Arabian Nights folktale collection. Ali Baba, the hero who eventually acquires a great treasure, works together with his slave Marjeneh, who uses her wits to save Ali Baba from the forty thieves on multiple occasions. This aria is sung by Ali Baba to Marjeneh, rendered in this English version as Morgiana. The aria seems to contain two verses, but it makes more sense dramatically for the second verse to be a reprise from the end of the show.

Ali Baba gives Marjeneh to his son in marriage at the end of the story, described in the text of the second verse: “Love made by a Parent my duty.” The first verse may refer to Ali Baba’s feeling deceived by Marjeneh when she kills an enemy thought to be a friend by Ali Baba, or it may be a romantic plot modification between Morgiana and Ali Baba, which occurred in the Orientalist 1944 Hollywood movie adaptation.10 The dramatic side of the musical romance is certainly demonstrated in the text of “Ah! What is the Bosom’s commotion,” which reads as follows:

Ah what is the bosom’s commotion In a sea of suspense while ‘tis tost

While the heart, in our passion’s wild ocean

Feels even hope’s anchor is lost:

While the heart in our passion’s wild ocean Feels even Hope’s anchor lost.

Morgiana thou art my dearest:

For thee I have languish’d and griev’d, For thee I have languish’d and griev’d.

5 Michael Kelly, 2:212-213.

6 Michael Kelly, “Ah! What is the Bosom’s commotion,” In The Forty Thieves (London: C. Christmas, c1806).

7 Jane Catherine Girdham, “Stephen Storace and the English Opera Tradition of the Late Eighteenth Century,” (PhD diss., University of Pennsylvania, 1988), 321.

8 Ibid., 322.

9 Girdham, 322.

10 Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves, directed by Arthur Lubin (Universal Pictures 1944), Youtube video. This movie and other adaptations tend to hypersexualize Marjeneh and her the love interest of all male characters.

21

1

And when Hope to my bosom was nearest How oft’ has that hope been deceiv’d And when Hope to my bosom was nearest How oft’ has that hope been deceiv’d Morgiana my hope was deceiv’d Morgiana my hope was deceiv’d

The Storm of despair is blown over, No more by its Vapour depress’d I laugh at the clouds of a Lover, With the sunshine of Joy in my breast. Love made by a Parent my duty, To the wish of my heart now arriv’d, I bend to the power of Beauty, And ev’ry fond hope is reviv’d. Morgiana my hope is reviv’d.

The lyrics to the first verse contain many references to lost hope and deception which may have real life implications for the drama in Kelly’s personal life at the time The Forty Thieves was produced. Furthermore, the majority of lines are repeated, indicating a very pensive character. Michael Kelly’s The Forty Thieves was produced shortly after the death of Anna Maria Crouch, Kelly’s very close friend who sang the lead soprano roles opposite his leading tenor at the Theatre Royal Drury Lane for many years. 11 In this dramatic aria sung to the leading soprano one gets a sense of the personal mourning Kelly was experiencing in the text. Kelly recalls wanting to quit acting altogether at this stage of his life; given his state at the time of the production, the mourning and repeated lines of hopelessness in the aria suggest that he may not have needed to act.12

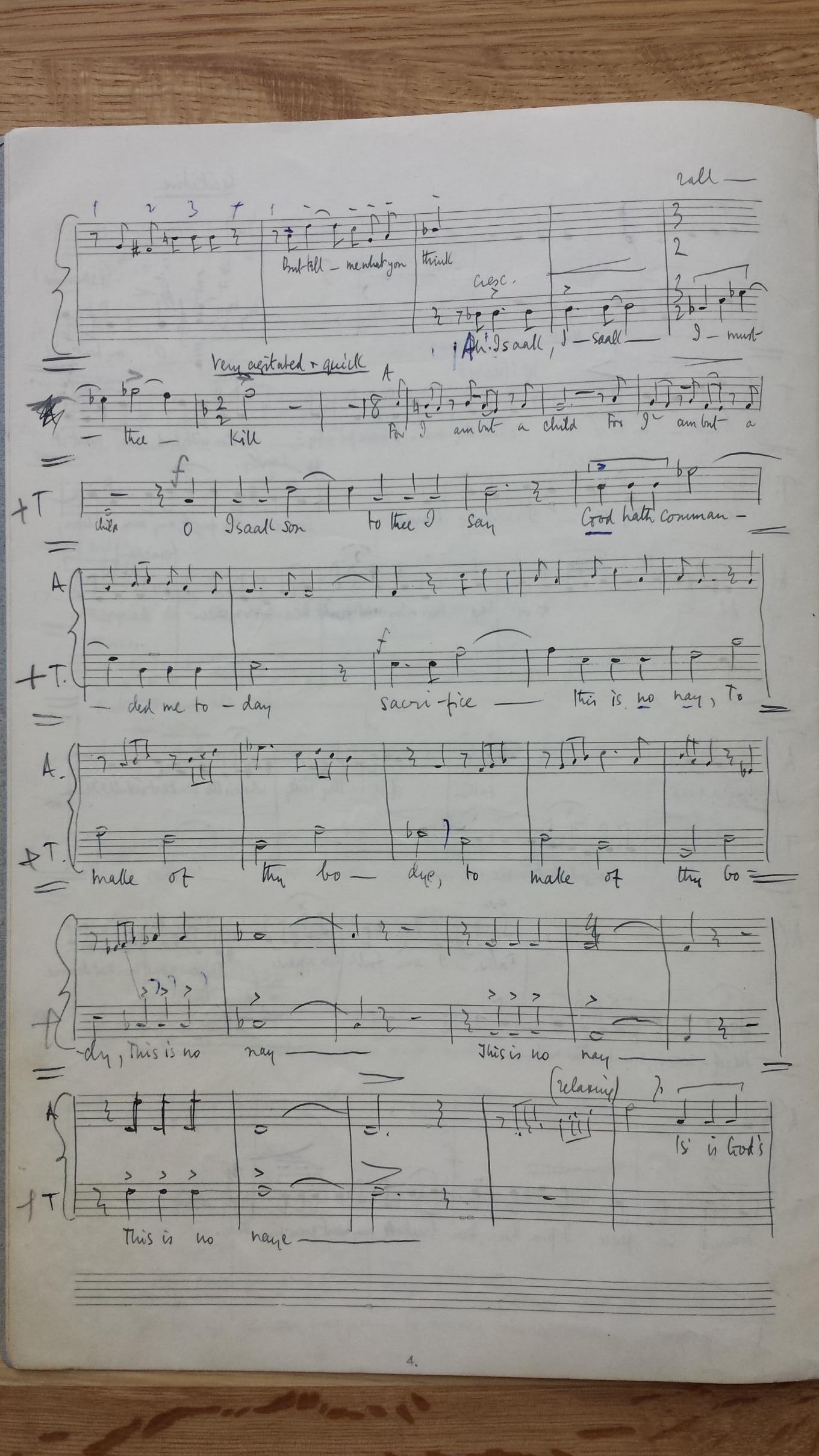

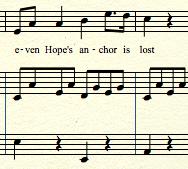

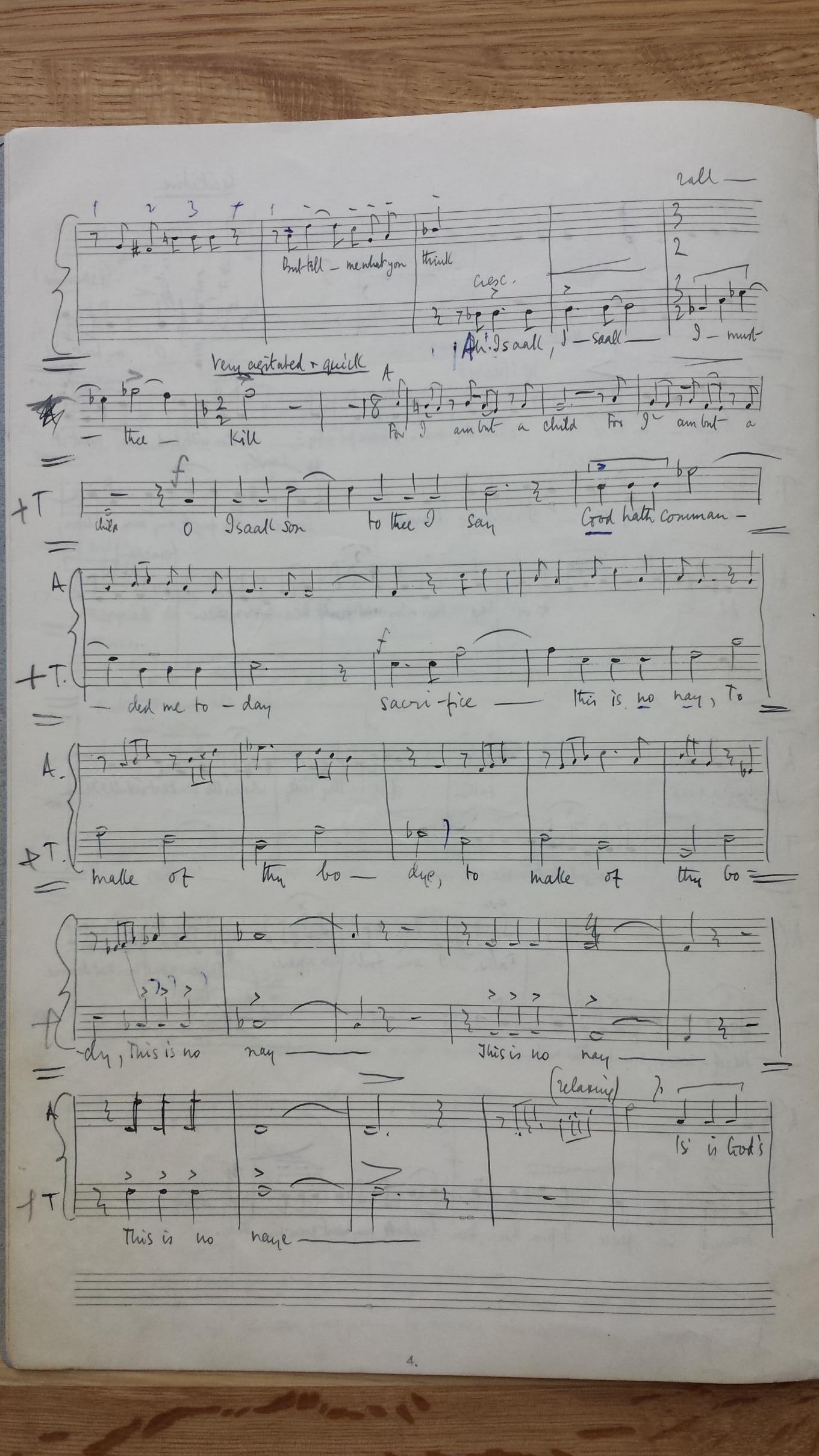

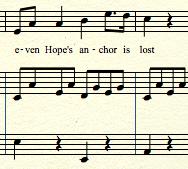

The music itself appears less affected than the text might suggest. Given that the aria was sung by Kelly, it is interesting to note that the aria has a range and tessitura much lower than the role of Don Basilio/Curzio. Whereas Curzio especially sings the majority of the time above the staff, “Ah! What is the Bosom’s commotion” does not go above an F#. Kelly was in his 40s during the premiere of The Forty Thieves and may not have had the same range as his younger days. His memoirs recall an invitation to sing Ferrando in Così fan tutte at the end of his career.13 The key, range, and melodic contour of “Ah! What is the Bosom’s commotion” follow Ferrando’s aria, “Un’aura amorosa” very closely and it is possible that Kelly was thinking of Ferrando as he composed this aria. Figures 1 and 2 resemble the similarities found in the opening measures of the two arias. 11

22

2

2:211.

Kelly,

12 Ibid., 212. 13 Ibid., 271.

He certainly wrote the vocal line to highlight his strengths. Based on an account of the aria given in an American journal regarding the performance of The Forty Thieves, it appears that “Ah! What is the Bosom’s commotion” was a vocal thriller. The Halcyon Luminary describes the American performance as follows:

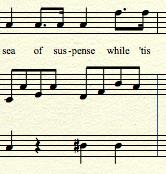

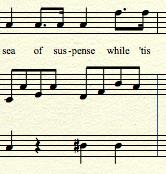

This highly and very justly admired song has met a deserved reception on our stage. It is performed by Mr. Darley , with the exquisite effect which ever accompanies that gentleman’s execution of the vocal tasks assigned to his profession.14 This aria was written to put the tenor’s voice on display. Kelly was distinguished among other tenors of his day for his abil ity to sing high notes in full voice, not resorting to falsetto.15 One critic recalled how Kelly’s ability to sing ascending intervals in full voice “often electrified an audience.”16 Kelly knew this strength of his as the dramatic moments occur on ascending fifths and sixths and the climax of the aria is on an octave leap. For example, there is a major sixth leap to bring out the word “languish’d” in measure 23, and

14 A Society of Gentlemen, “Ah! What is the Bosom’s commotion,” The Halcyon Luminary and Theological Repository, vol. 2 (1813): 184.

15 A. Hyatt King, introduction to Reminiscences of Michael Kelly of the King’s Theatre and Theatre Royal Drury Lane , by Michael Kelly (New York: Da Capo Press, 1968), ix.

16 Ibid.

23

Figure 1. Mozart, “Un’aura amorosa,” Così fan tutte, mm. 1-5.

Figure 2. Kelly, “Ah! What is the Bosom’s commotion,” The Forty Thieves, mm. 1-5.

Kelly also employs word painting in measure 15. As the singer laments, “even Hope’s anchor is lost” there is an ascending leap on the second syllable of “anchor.” These devices can be seen in Figures 3 and 4 below.

Kelly even indulges himself with a fermata over a high F# leading into the final cadence in measure 36. Kelly uses the lyrics and expressive melody to highlight his tenor voice and dramatic ability.

Harmonic variation is rather limited in this aria which is likely due to the compositional process behind The Forty Thieves and Kelly’s other works. Unlike his friends and fellow composers Mozart, Salieri, Gluck, and Haydn, Kelly did not write his own accompaniments or harmonizations. Thomas Moore sheds light on Kelly’s compositional process in a letter dating 1801, which poetically states: “Poor Mick is rather an imposer than a composer. He cannot mark the time in writing three bars of music; his understrappers , howev er, do all that for him.”17 Kelly composed the melody which was then harmonized and orchestrated by his assistants. “Ah! What is the Bosom’s commotion” is set in A major with an eight bar introduction. It is curious that such a lamenting song would be set in a major key. After an exposition of the melody, it passes through a V/V chord and ends solidly in a I, IV, I64, V, I progression ending with a perfect authentic cadence. This is quite literally a textbook chord progression which reinforces the claim that Kelly’s understrappers do his harmonizing for him. The accompaniment uses a broken chord Alberti bass pattern throughout. The aria is strophic and follows an ABA’ form modulating to b minor in the B section. The introduction is quoted to close the aria with one key difference: The arch of the introduction peaks with a fortissimo pounding of a IM7 followed by a rapid scalar descent in the right hand. This same moment occurs at the close of the aria with but the chord spelled as a simple A major triad. Figure 5 demonstrates the IM7 chord in measure 5 while Figure 6 shows the I chord in measure 39.

17 King, x.

24

Figure 3. mm. 23. Figure 4. mm. 15.

One can be certain the IM7 at the beginning was a typo given the harmonic palette of the time. Moreover, if we compare this score to the American editions available online, we see that all other versions show a I chord. This choice also seems representative of the conservative harmonizations encountered in Kelly’s other works, specifically his most successful opera, Blue Beard 18 Another typo occurs in measure 11, shown in Figure 7, where an accidental is missing in the right hand of the accompaniment. While these typos may seem like careless mistakes made by the printers, they may contain great significance with regards to the printing and distribution of the sheet music.

At this point it is certainly relevant to ask how an aria from an almost forgotten Irish composer made its way into an American song collection. According to A. Hyatt King in the introduction to Kelly’s memoirs, his music “enjoyed considerable success in America.”19 Over two hundred separate issues of his music were published in major American cities during his lifetime, with his arias making up the bulk of the publications. Furthermore, it was not uncommon for his operas to be produced in America shortly after their premiers in London. There are seven different American publications of “Ah! What is the Bosom’s commotion,” all published within five years of the opera’s premiere. 20 While Kelly’s music was published in multiple American cities, the Josephine L Hughes collection is unique in that its three copies of “Ah! What is the Bosom’s commotion” were printed and sold in London. On the title

18 Paul Douglass and Frederick Burwick, “Bluebeard; Or, Female Curiosity!,” Romantic-Era Songs, last modified 2009, accessed April 6, 2015, http://www.sjsu.edu/faculty/douglass/music/album-bluebeard.html.

19 King, xiii.

20 These alternate editions were discovered through a search of the aria’s title on WorldCat.

25

Figure 5. mm. 5.

Figure 6. mm. 39.

Figure 7. mm. 11.

page of the aria appears, “Printed and Sold by Chas. Christmas 36 Pall Mall.”21 There is no copyright date provided on the score, however, the date of publication can be deduced from the printer’s name and location. One might presume that the printing is a first edition due to the typos in the music, but also due to the fact that it was printed by Chas. Christmas and not Falkener & Christmas. Michael Kelly’s publishing company occupied 9 Pall Mall (right next to the Theatre Royal Drury Lane) and 4 Pall Mall, while C harles Christmas sold from 36 Pall Mall; after going bankrupt in 1811, Kelly’s shop was acquired by a music publishing merger between H. Falkener & Chas. Christmas.22 Since this copy was printed at 36 Pall Mall prior to the merger, it is likely that Michael Kelly was still publishing and selling at 9 Pall Mall when this copy was printed and sold. One online song database has dated the Charles Christmas edition to 1807, which is well within Kelly’s publishing career.23 Michael Kelly states in his memoirs that he began his music publishing business for the purpose of selling his own compositions, therefore it is highly unlikely that Kelly sold the rights to his own music when he could have printed it himself.24 Thus, it is probable that the edition of “Ah! What is the Bosom’s commotion” contained in the Josephine L. Hughes collection is a “bootleg” copy of Kelly’s aria. In the introduction to Kelly’s memoirs, King mentions that there were instances of publishers pirating Kelly’s music though mostly abroad in America or Ireland.25 During this time period, however, it was also common for publishing companies to pirate the works of local composers within England.26 The pirated editions would often include intentional errors in the score.27 Considering the typos present in this edition, one can infer the Josephine L. Hughes copy was likely pirated just down the street from Michael Kelly.

Studying “Ah! What is the Bosom’s commotion” allows a glimpse into Georgian era opera from the stage to the printing press and across the ocean into the American Parlor. Using first hand accounts of Kelly’s singing combined with knowledge of his composing influences, such as Mozart, one can infer the stylistic tendencies of this aria in order to provide a well informed performance of a work that once thrilled audiences in England and America. Furthermore, despite the fact that Kelly’s works receive little attention today, the study helps provide insights that go beyond the music, particularly the illegal printing of the JLH collection’s edition. This information can help raise questions regarding the authenticity of other scores in the JLH collection. It is hopeful that further research in the Josephine L. Hughes collection can discover more hidden treasures and fresh insights into the individual sheet music practices of the young United States.

21 Kelly, 1.

22 Frank Kidson, British music publishers, printers and engravers: London, Provincial, Scottish, and Irish (London: W. E. Hill & Sons, 1900), 26.

23 “Ah what is the Bosom’s commotion,” Song List, last modified 2011, accessed April 6, 2015, http://arabkitsch.com/directory/ahwhat-is-the-bosoms-commotion.

24 Kelly, 163.

25 King, xiii.

26 Girdham, 167.

27 Girdham., 170.

26

Bibliography

Arab Kitsh. “Ah what is the Bosom’s commotion.” Song List. Last modified 2011. Accessed April 6, 2015. http://arabkitsch.com/directory/ah-what-is-the-bosoms-commotion.

A Society of Gentlemen. “Ah! What is the Bosom’s commotion.” The Halcyon Luminary and Theological Repository, vol. 2 (1813): 184.

Boykin, Amy. “Treasure Trove of American Sheet Music: The Josephine L. Hughes Collection.” Virginia Libraries 50, no. 4 (Fall 2004): 5. Accessed March 16, 2015.

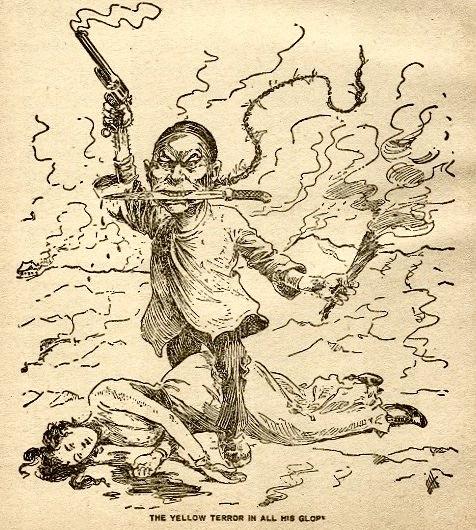

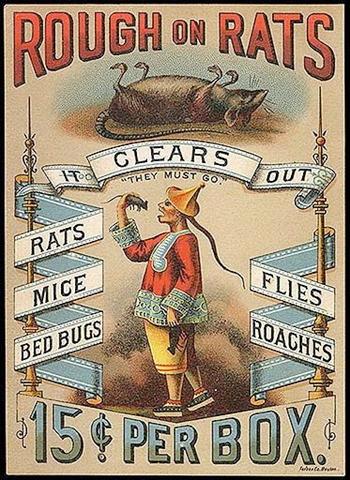

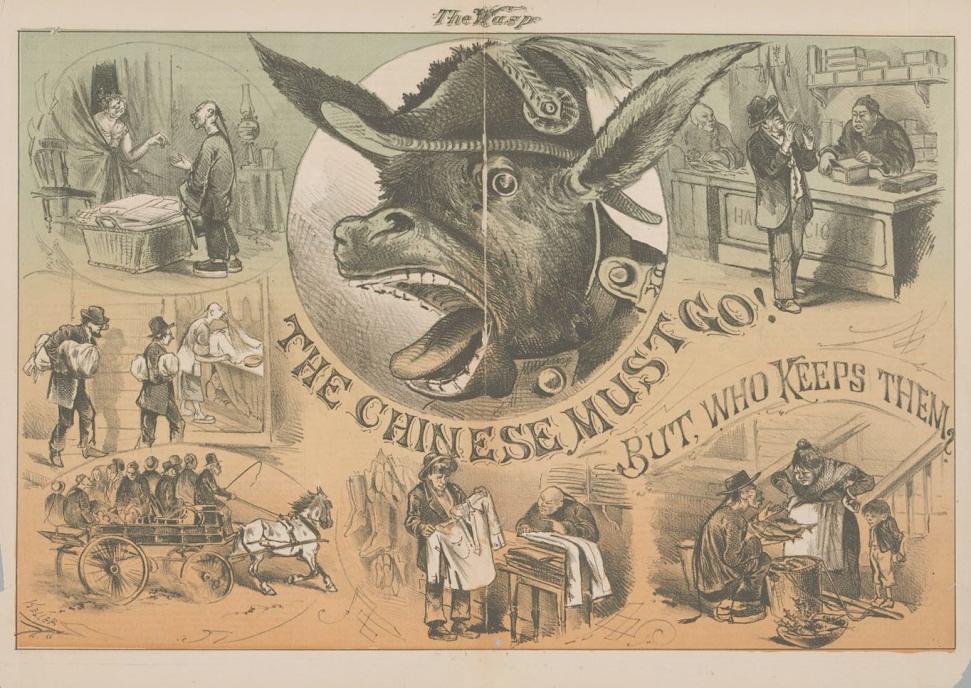

Douglass, Paul & Burwick, Frederick. “Bluebeard; Or, Female Curiosity!.” Romantic-Era Songs. Last modified 2009. Accessed April 6, 2015. http://www.sjsu.edu/faculty/douglass/music/album-bluebeard.html.