Introduction

DeconstructingaLegacy

ForgivingTransgressions

ReadingtheTranscriptsandMicromegas

TheDrawingsof‘IdealSpace’tothe Physicalityof‘RealSpace

Conclusion

Content

’

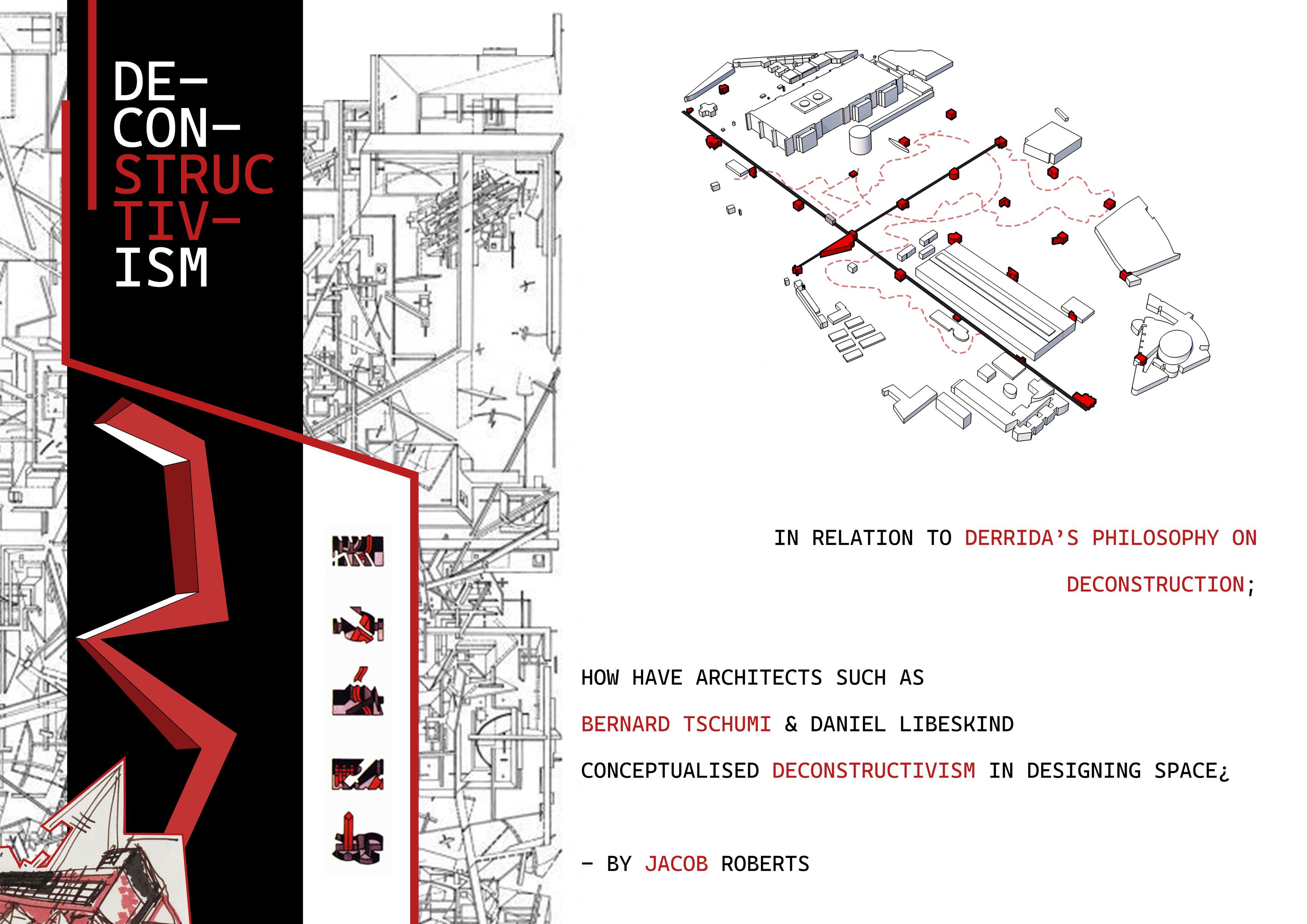

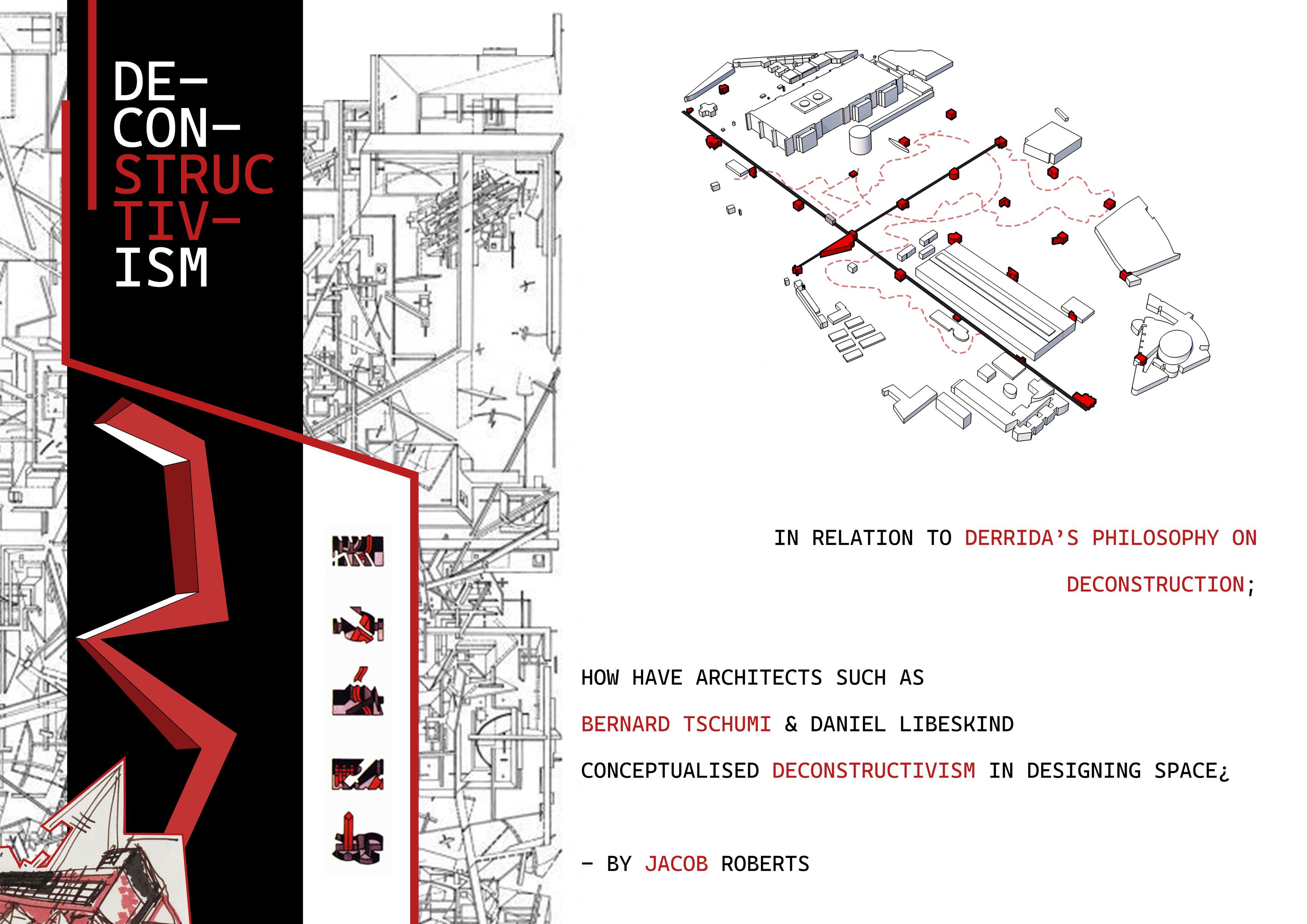

When we look at space, we sometimes misinterpret what it is exactly we are looking at - or not looking at? We also start to unconsciously question its limit, limitless, rigidity or flexibility space can be pushed to. This is where the line of philosophy and architecture blur: when the curiosity of something so unknown yet so present becomes materialised allowing us as architects and designers to start determining an architectural discourse that explores the uncanny. Already we start to conceptualise space as a ‘construct’ that can be ‘deconstructed’, or do we first have to deconstruct the concept of space before we can construct it?

FIGURE 1. DANIEL LIBESKIND

FIGURE 2. BERNARD TSCHUMI

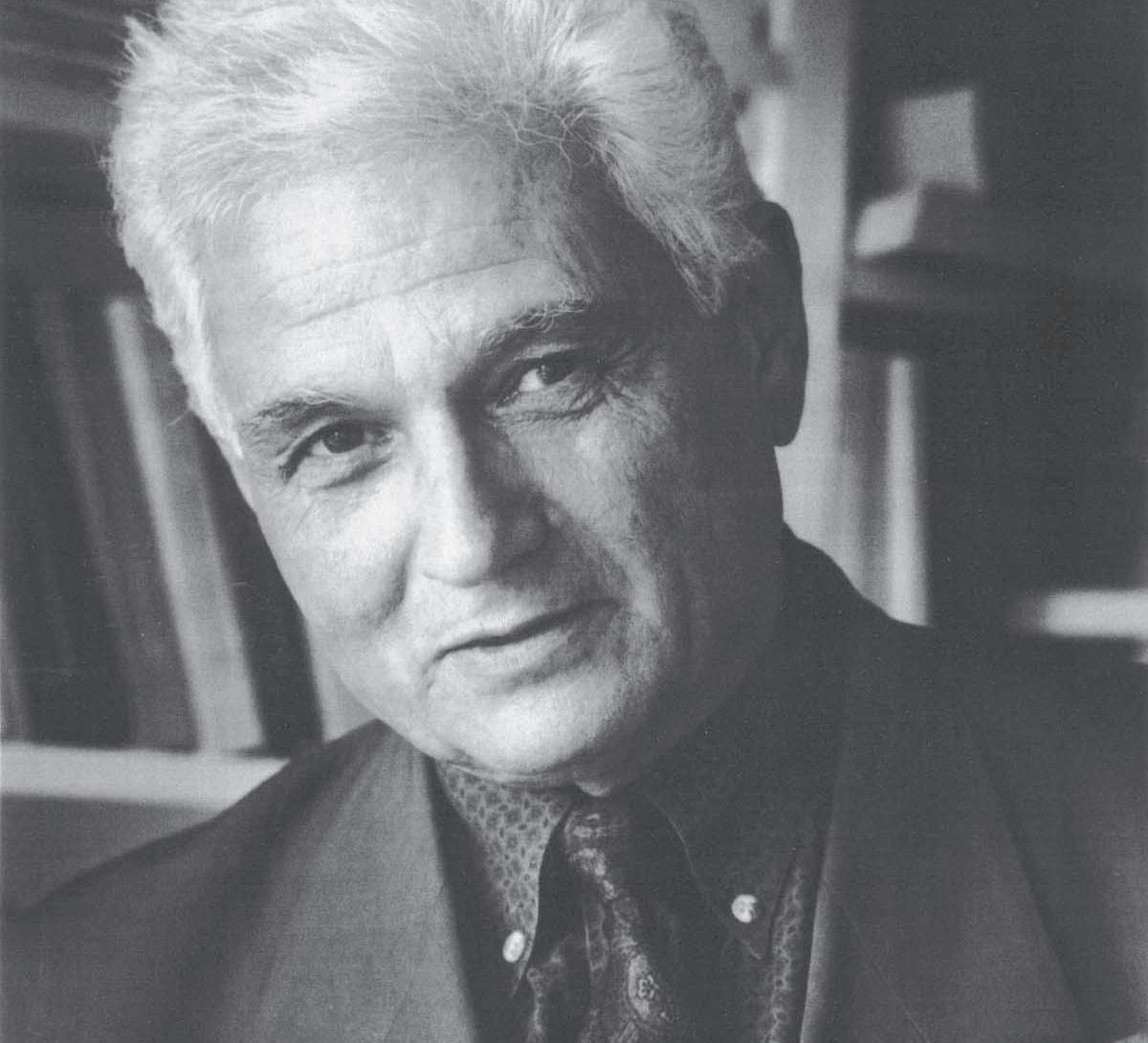

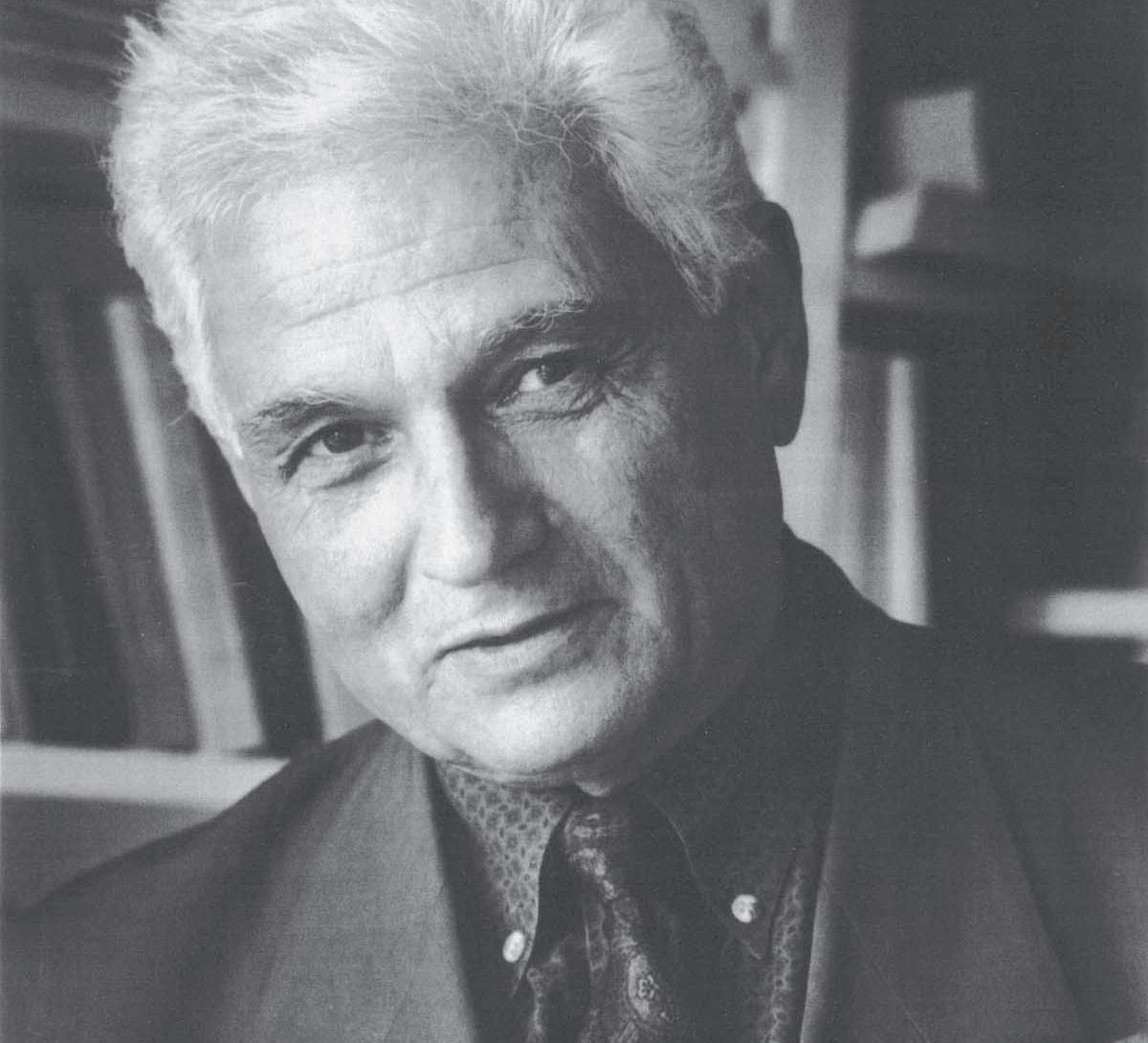

FIGURE 3. JACQUES DERRIDA

FIGURE 1. DANIEL LIBESKIND

FIGURE 2. BERNARD TSCHUMI

FIGURE 3. JACQUES DERRIDA

Deconstructivism became a personal influence after the readings of ‘Gordon Matta-Clarke’. The concept of pushing space to beyond these superimposed ‘Limits’ to the discovery of new dimensions in architecture, new boundaries, fuel curiosity and include a real response to the impact that architecture can really have on an ethical level involving how humans experience space. As an observation we see a lot of the environmental architecture as being the same in a lot of ways, but architecture as important as it is towards making a sustainable approach to society and our eco-system, we must not forget that our development must not disregard to the contribution to the abstractness and experience that we find ourselves immediately involved in when we enter a space.

This essay’s objective is to give a background into Deconstruction in relation to Jacques Derrida’s Theories in his Philosophical profession. Through these theories that I will attempt to gain an understanding of Deconstruction and covey the translations from Philosophy to Architecture using the terms of ‘Deconstruction’ to ‘Deconstructivism’. These translations can be interpreted from many viewpoints from architects, however, the specific conceptualisations I will look at regard the Architectural Philosopher ‘Bernard Tschumi’. Tschumi’s essays specifically address his thoughts and philosophical justifications of how architects can begin to conceptualise Deconstructivism through the explorations of ‘Transgressions’. To produce an unbiased analysis with these translations I will attempt to write on the boarders of a deconstructive way in regard to not set out to find answers to what the translations actually are, but in fact create question regarding what Tschumi is trying to convey in order to allow the conceptualisation of deconstructivism to remain in a state of flux, intended by the original philosophical meaning towards language (Rajput, 2019).

I will move towards analysing how Two key architects; Daniel Libeskind (Fig. 1) and Bernard Tschumi (Fig. 2) communicate their ideas on paper through the concept of ‘Ideal Space’ within the case studies of ‘Micromegas’ and ‘The Manhattan Transcripts’ drawings. Furthermore, I will expand on these ideas using a comparison between the two in order to understand the similarities and differences of the approaches that each architect takes when incorporating Deconstructivism into their work. Furthermore, I will move deeper into both architects minds and question how they have incorporated each of their theoretical drawings from ‘Ideal Space’ into the physicality of ‘Real Space’ by using case studies of Libeskind’s Jewish Museum, Berlin in contrast with Tschumi’s, Parc De La Villette to underline what each structural or non-structural piece of architecture has that indicates the concept of becoming a transgression of this ornamented post modernism way of designing for functionalism.

Ultimately, this essay intends to reach a conclusion on how architects have incorporated a deconstructive approach into their conceptual drawings addressing their similarities and differences of each architects perception on the idea of space. I also aim to conclude how the two architects have incorporated contrasting elements into their design, backed up by independent reading and site visits to ‘Parc De La Villette’ implementing first-hand experience into the formula. Finally, I can start to convey my own conceptualisation based upon my readings and analysis of Deconstructivism through drawings and writings backed up by sources such as Books, e-books, articles, Videos, Podcasts, reliable essays, and personal experiences.

Introduction

Deconstructing a Legacy

Deconstructivism is often questioned as being a style or an avant-garde movement against architecture or society that does not follow rules and specific aesthetics (Stouhi, 2020). To understand the concept of deconstructivism it is first important to appreciate the roots of its original texts in order to understand its translation.

Deconstructivism stems from a term coined by French philosopher ‘Jacques Derrida’ (Fig. 3). Born in 1930 into a Sephardic Jewish Family in the French Governed Algeria. He was educated in the French tradition studying Philosophy at the elite École Normale Supérieure (ENS) (Britannica, 2023). Through his early stages Derrida wrote a selection of important essays leading up to his success, especially relating to ‘Violence and Metaphysics’ (Lawlor, 2022). As Derrida pursued Philosophy his curiosity led his to publishing a series of Three Books almost all at Once ‘Writing and Difference’ ‘Voice & Phenomenon’ and ‘Of Grammatology’. Derrida used the term ‘Deconstruction’ in all Three books written, which caught on almost immediately in the philosophical world of Language (Lawlor, 2022). Ultimately, grabbing the attention of even the most unlikely of specializations. Architecture being the key antagonists of Deconstruction.

Although there is a misconception between ‘Deconstruction’ and ‘Deconstructivism’ as the Two branch from separate professions, they are both much more connected that it may seem. As a summery, deconstruction is a critical school of language, Derrida’s research in the philosophical field of literature brought us to the attention of Deconstruction. The Complexities of Derrida’s mind ask us to question if meaning is fixed? He implies that meaning is not stable and constantly in a state of flux determined by the context in which it is found (Rajput, 2019). What he is expressing is that written words in language form part of a subjective truth where we should look for meaning by deliberation with the approach of an unbiased eye. Derrida states that in Western culture there are hierarchies within binaries such as ‘light’ and ‘Dark’ that give the assumption that there is a dominant of the two oppositions when we see them with this bias view (Guignion, 2020). Ultimately, allowing us to deconstruct the original construct and find the true value of the original concept that is often overlooking in language by breaking it down to expose its underlying meaning (Rajput, 2019).

As a philosopher, these manifestations are contagious, especially in such a field where the underlying concept is detrimental to the way space is interpreted and designed. Therefore, the idea of deconstruction grew of huge interest in architecture and the translation between philosophy to architecture inspired Deconstructivism.

FIGURE 4. MANHATTAN TRANSCRIPTS

FIGURE 5. MICROMEGAS

FIGURE 4. MANHATTAN TRANSCRIPTS

FIGURE 5. MICROMEGAS

Forgiving Transgressions

The transgressions aim to open the door to what lies beyond the limits that are already imposed upon what we know and observe in architecture (Tschumi, 1996). As Derrida’s theory of ‘Deconstruction’ initially set out to question and criticise, architects such as Bernard Tschumi and Daniel Libeskind also set out to achieve the same with basic principles and rules that condition the very concept of how modernists look at space in this ‘Bias’ form. The transgressions on the other hand according to Tschumi; aim to break the conventional rules that have already been applied to what architects already see as ‘logical design’ without destroying them. Tschumi uses Three parts to what he calls the Transgressions.

Part One – The Paradox: Emphasising the strange ‘Paradox’ that seems to haunt architecture. He talks about the impossibilities of simultaneously questioning the ‘Nature of Space’ and the experience or making of ‘Real Space’ (Tschumi, 1996). In one way this implies the idea of questioning space to reveal its ‘limits’ allowing architecture to expose the real experience of itself when it is exposed to the ‘nature of space’. The paradox theory of the transgressions leading to what Tschumi is trying to say is also shown through the drawings on the ‘Transcripts’ (Fig. 4) as well as the ‘Micromegas’ (Fig. 5). These common factors seem to come together to conclude both architect’s theoretical approaches to the design of space as shown in (Fig. 6 and Fig. 7 – Micromegas and Transcripts illusions – annotated). Through these drawings they seem to suggest new horizons once we find the ‘limits’ that space already has imposed on us. As questions arise from these ‘limits’ the paradox starts to emerge from these questions of how and why – not from the architect; but from the existence that is in the space – the opposite binary of the designer: the reader or interpreter. What both architects seem to do at this stage is underlay the idea of challenging the users perception and encouraging them to think and experience space in a different way. Taking the initial concept of Derrida’s deconstructive approach by constantly allowing space to have this flux by engaging with the reader of a space using questions offered through visual interpretation, and the feeling that a space is given due to the readers own understanding. Contradicting the design itself by being an unfinished completion of space defined by architecture or architecture designed by space (Tschumi, 1996).

FIGURE 6. MICROMEGAS ANNOTATED - BY JACOB ROBERTS

FIGURE 7. TRANSCRIPTS ANNOTATED - BY JACOB ROBERTS

FIGURE 6. MICROMEGAS ANNOTATED - BY JACOB ROBERTS

FIGURE 7. TRANSCRIPTS ANNOTATED - BY JACOB ROBERTS

Part Two

eROTicism: Tschumi later expands on the lead towards transgressions by explaining that there is a point in which these contradictions heavily influence deconstruction to be perceived in a contradictory way. What he finds interesting here is that the paradoxes are constantly contradicting each other. However, this is saying that each meaning is required by the other and vice versa. In order to find these meeting points we look at architecture as manipulating the physical form to create erotic emotion in a space or a sense of danger to enable us to feel this emotion created by the physical form of architecture that is around us. Tschumi processes this idea through two correspondences:

The first correspondence he uses is ‘eROTicism’ where he explains it is not the ‘excess of pleasure’ but instead ‘the pleasure of excess’. Understanding ‘eroticism’ is the double pleasure of both the mental construct and the sensuality (Tschumi,1996).

The Second Correspondence suggests that the junction between ‘ideal space’ and ‘real space’ are seen differently. He implies that architects rarely go against the imposed structure that society expects from architecture, such as the representation of social and political outlooks. Through this perception Tschumi suggests that social political structure of society expects architects to domesticate the deeper fears that society often ignores. (Tschumi, 1996). To Summarise, what the second correspondence is implying is that in order to look at eroticism and express this through the transgressions in correlation with the First Correspondence is that we bring these deeper fears to light in order to create the concept of ‘eroticism’ and enlighten these emotions that are created by pushing the physical and metal construct of space and architecture to offer these feelings of danger and unease in correlation with post-structural philosophy of Derrida’s theory of Deconstruction (Wigley, 1997).

Part Three – The Transgressions: Through the process, we head into the direction of disruption and challenging the conventions associated with Notion, Form and Space. The transgressions start to observe and cause the link between mutually interdependent aspects where spatial praxis meets the mental construct used to transgress form the rules already put in place. Secondly, time is relative in the concept of space and its transgressions from the original concept of time leaves its traces in the built form, past of future that is there to resemble everyday life and these traces left behind by the relativity of time are what Tschumi conveys “marks a building” (Tschumi, p.77, 1997).

–

FIGURE 8. TRANSGRESSIONS

Decisively, this meeting place explained by Tschumi causes the threat that challenges the autonomy and the distinction between the contrast of Concepts and Spatial Praxis and that there is a case of decay in architects that choose to question the conventional distinction between concepts and spatial praxis. Tschumi also introduces the idea that most architects work in relation to paradigms set through the education acquired in the study of architecture and elaborating that the specific characteristics that have implied these rules into these practical subsequent taboos that seem to remain fixed (Tschumi, 1997). To transgress, Bernard Tschumi starts to deconstruct these conventional paradigms of taboo as he implied that from these fixed positions starts to cause a state of rot or decay. The rules start to move and become a state of flux through the unveiling of them. The complex process is due to the fact that these hidden rules guide these specific architectural approaches that originally made them, which architects often find themselves fixated on because of the “Conditioning” – (Tschumi, p.78, 1997).

Conclusively, this transgressional concept that Tschumi instigates of architecture exists in a paradox of its own contradictions when the social expectations of architectural form are negated.

Tschumi idealises that the ever contradicting transcendent of paradoxical nature is not to destroy the very rules that make up the conditioned approach that architects are educated into following, but actually it is an act of transgression that ultimately challenges the conventions of the ornamented rules that order a structure in society and architecture. Pushing these ornamented rules into a state of flux by looking beyond these rules without destroying what is existing (Tschumi, 1997).

Through transgression it puts architecture into a perspective lens of sacrilegious and convergence of ideal and real space to overcoming these contradicting binaries as well as objectionable prevalence’s without destroying them (Tschumi, 1997).

FIGURE 9. TRANSGRESSIONS BREAKING

FIGURE 9. TRANSGRESSIONS BREAKING

As we now understand, deconstruction is a way criticising the very conventions of what we already know and don’t know. By criticising we ‘question’ these conventions. We can start to conceptualise these questions as architects by our own language specifically regarding drawing, to allow us to demonstrate that we are questioning space and finding its ‘limits’ (Tschumi, 1994). Tschumi’s thinking is captured in some of his famous drawings ‘The Manhattan Transcripts’ (Fig. 10) where he expands on his idea of notation, that architecture is almost like an experience of symbols that tell the user how the space can function and that these are the limits of space. However, with this said Tschumi goes further with this, stating that “The limits of my language are the limits of my world’. Any attempt to go beyond such limits, to offer another reading of architecture demanded the questioning of these conventions” (Tschumi, P.9, 1997). When Tschumi talks about the limits of his language he is criticising the conventional ways in which architects communicate their concepts such as plans, sections, elevations, and axonometric drawings but also the most accepted of all in modern architecture – Form Follows Function. Bernard Tschumi is saying that when we look at going beyond the pre-existing limits of space then we must first look at the conditioning of the original concept initially to then begin to question space itself (Tschumi, 1994).

Libeskind on the other hand contrasts with the philosophy and conceptualisation of the ‘Limits’ that space has to offer. He uses this concept in the dissolution of space by first beginning to materialise space as a physical entity that can be both present and absent in its rationality (Mandry, 2013). In Libeskind’s own way he questions space as if there are ‘limits’ to it – specifically referring to is as the “End of Space” – (Libeskind, p. 68, 2001). This concept is about finding these ‘Limits’ that have been superimposed on the original concept. Through these findings he communicates these spatial ideas through questioning the conventional strategies of architectural drawing by using Paradoxical drawings that challenge the very dimensions of space that we already know. Furthermore, Libeskind shows his intention to oppose these ‘Limits’ that seem superimposed on the conditioning of communication through drawing but in contrast to Tschumi, explains in that, to oppose we must at the same time destroy or deconstruct the mobility and variation that is incarnated into the very nature of formalism by rejecting the form based upon the architectures function (Libeskind, 2001). Through Libeskind’s ‘Micromegas’ (Fig. 11) it is present that the conceptual agenda looks towards the idea of open and unknowable horizons. What is being conveyed here is that the space we know has more depth to it than that of what we have already seen and facing this allows us to begin to see. The ‘Micromegas’ aim to question through critical analysis of the architectural drawings that seem to be fixated into architecture. These classical outputs that seem mandatory to the success of a construct elaborate its usefulness embedded in a theory of overall order unifying them to make a contemporary formal system of logical approach often related to philosophy. As stated by Libeskind “Formal systems present themselves as Riddles – Unknown instruments for which usage is not yet found” – (Libeskind, p.84, 2001).

the Transcripts & Micromegas

Reading

FIGURE 10. MT 4 ‘THE BLOCK’

FIGURE 11. LIBESKINDS, MICROMEGAS

Through the Transcripts of Bernard Tschumis drawings in a deep analysis we can start to understand how the conventional ways of architecture are questioned in relation to space. He starts to ask if the architecture that we design is conformed to being a physical structure. This seems to be one of the key challenges in the transcripts. As seen in (Fig. 12) it attempts to interpret exactly what an extract from MT 4, ‘The Block’ is trying to convey through Tschumi’s conceptualisation into the design of space. From analysis, it is questioning the physical structure of architecture that moulds the space where we gain these experiences. Nevertheless, what it is actually saying is that the fragments of structure, as relevant as they are part of the architecture is actually incomplete until the experience and ‘Violence’ in Space happen. To summarise this concept, it is saying that the experience that happens in architecture, finish the work of the designer and therefore space is beyond multiple dimensions as infinite experience can happen in a space, suggesting that the concept that the designer is trying to convey is constantly in flux (Tschumi, 1997).

In Contrast to the idea of Bernard Tschumi, Libeskind also challenges the physical structure of architecture. His conceptualisation of space is between the unbiased look towards physical space and absent space – Negative Space (Libeskind, 2001). His approach underlines that there should be this unbiased hierarchy between space and structure, which then can be contrasting between the positive and negative space that he implies. Libeskind does not however, talk of architectural action as ‘violence in space’ – he grows more towards the experience that is created in a piece of architecture, which is also noted in some of the writing of Bernard Tschumi. Therefore, it seems logical to say that areas of deconstructivism move towards a more human interaction and ethical presence to the underlying concept of the designers and authors.

There is evidently a balance between the two, they both seek to reveal the underlying truth of the experience that happens in an architectural space through their own transgressions. On the contrary both have contrasting approaches. Libeskind uses his drawings to provoke emotion into space and stimulates senses of a presence of absence. This is understood in his drawings as presence and absence are both contradicting, so when we look to analyse the embedded meaning behind his drawings – most commonly found in the ‘Micromegas’ we see the paradoxes and illusions that make no sense in the physical world but opens a new dimension of architecture that translates in a metaphorical term. Now we can start to question through the language of drawing what he is trying to communicate? When we look at illusion we start to question if these impossibilities are possible. Libeskind through his use of drawing does this very impressively by using these paradoxes in a more theoretical way using translation of metaphor in order to convey that ‘absence is made present’.

FIGURE 12. TRANSCRIPTS ANNOTATED - BY JACOB ROBERTS’

FIGURE 13. TRANSCRIPTS CONCEPTUALISATION

FIGURE 12. TRANSCRIPTS ANNOTATED - BY JACOB ROBERTS’

FIGURE 13. TRANSCRIPTS CONCEPTUALISATION

The Drawings of ‘Ideal Space’ to the Physicality of ‘Real Space’

Like most architects who design practical ‘Real Space’ first convey their language with pen and paper in the hope of communicating and testing a strong concept. Both Libeskind and Tschumi used the convention of drawing to test the limits and durability of them in order to explore the uncanny of architecture that is usually not legible without conveying the underlying ideas behind the space itself. Unlike most conceptual drawings the concept in both Tschumi’s and Libeskind’s work met reality through the exploration of physical form – ‘Real Space’.

Libeskind’s conceptual drawings of the ‘Micromegas’ are very different in many ways. However, as much as these drawings that Libeskind produces are primarily for conceptual purposes, they are not to be seen as architectural blueprints, but rather to communicate his ideas and translate them through metaphorical compositions that rely heavily on their symbolism in order to convey their meaning in both drawn form and physical space and structure. Initially these conceptual drawings stem from a deconstruction of the space and existing dimensions in the exploration of new metaphorical meanings. On the other hand, the physical structure of the ‘Jewish Museum, Berlin’ (Fig. 14) Libeskind uses the enriched history of the existing knowledge and symbolism to deconstruct the ‘Jewish Star of David’ which, similarly, explores the fragmented dimensions of their past to then enrich knowledge of the future represented by the striking physical architecture displayed on the site (As Seen in Fig. 15 – Deconstruction of the Star of David) (Young, 2000).

FIGURE 14. IMAGE OF JEWISH MUSEUM, BERLIN

FIGURE 15. STAR OF DAVID DECONSTRUCTION - BY JACOB ROBERTS

FIGURE 16. JEWISH MUSEUM PLAN

FIGURE 17. MOVEMENT BETWEEN THE LINES

FIGURE 14. IMAGE OF JEWISH MUSEUM, BERLIN

FIGURE 15. STAR OF DAVID DECONSTRUCTION - BY JACOB ROBERTS

FIGURE 16. JEWISH MUSEUM PLAN

FIGURE 17. MOVEMENT BETWEEN THE LINES

This idea of Libeskind’s ‘absence while being present’ are translated from these ‘micromegas’ and implemented in the design of his ‘Jewish Museum, Berlin’. The space of the building is what constitutes his architecture where the voids and absences are embodied by the ‘Invisible’ and ‘Empty’ spaces that are experienced around the walls (Young, 2000). In his ambitious conceptualization to balance presence with absence succeed in his writing of (Libeskind, The Space of Encounter, 2001) where he elaborates on his concept for the Jewish Museum, Berlin. He represents the future in Juxtaposition to the past alongside the beginning in relation to the end through the use of engaging with the interpreter on a visceral, emotional, and mental level (Libeskind, 2001).

With these contradicting binaries there seems to be an absence of logical configuration of how the spaces may start to work in relation to logical order. However, Libeskind does this very well as he uses the architecture as a sense of fragmentation and deconstruction in order to assemble the zig zag patten and intersecting lines (As seen in - Fig. 16). As the ‘Micromegas’ seem to produce a sense of disorientation to the viewer in the ideal reality of space, it is also implied into the theoretical approaches to movement as part of the experience, like Libeskind is trying to achieve a fixed space with a linear sequence of movement that incorporates a movement of flux with the multiple spaces that are given (Fig. 17 – Image of Libeskind’s drawings that show the movement Between the Lines).

In a contrasting observation, Bernard Tschumi’s conceptual drawings are not formal plan or legible for bringing these conceptual ideals of space into the physically of this dimension, but what they are a tool, like Libeskind; tool for a metaphorical translation of what falls between fantasy and reality - offering legibility to the philosophical meaning of the deconstructed truth behind a buildings concept (Genel, 2019). In Tschumi’s transcripts, the overall purpose he is trying to convey is the exploration of Space, Movement and Events. However, a keynote to understand is that these key implications are explored on the context of Manhattans urban Environment (Tschumi, 1996). As discussed earlier, he goes into the depths of how architecture is not just about the physical forms of buildings that most seem to recognise architecture as, but like Libeskind implies as well is that it is more to do with the space that is between the lines. When Tschumi looks closer into the space what he addresses is the events and actions that take place, expanding that they are embedded with that space, completing the architecture and the perception of the place in which it happens.

Tschumi’s exploration as much as the translations from the ‘Transcripts’ are metaphorical, they are still a vast influence towards his physical constructs of ‘Parc De La Villette’ (Fig. 18) through the exploration of Lines, Points and Surfaces (As Seen in Fig. 20) (Genel, 2019).

FIGURE 18. FOLIES OF PARC DE LA VILLETTE

FIGURE 19. PARC DE LA VILLETTE CONCEPTUAL DRAWINGS

FIGURE 18. FOLIES OF PARC DE LA VILLETTE

FIGURE 19. PARC DE LA VILLETTE CONCEPTUAL DRAWINGS

Firstly, they engage with his conceptual drawings through the exploration of the idea that there is this relationship between space and movement. The programmatic display of movement in Parc De La Villette is associated through one of his superimpositions of ‘Points’ (Fig. 20) that use the idea of a system of points that link to the system of objects incorporated into the park. The points propose a grid system that is separated from a network of the ‘Folies’ (Fig. 18). The bright red markers distributed along a grid of 120 Meter intervals suggest a disruption of a cube with a volume of 10 cubic Meters (Genel, 2019). These points are proposed by Tschumi that they act as ‘Points of Intensity’ that ultimately aim to permit maximum movement through the site and allow the user to explore different parts of the park through an arrangement of organisation, order and continuity.

Furthermore, Tschumi States “there is no space without event, no architecture without program” – (Tshcumi, p.139, 1996). Here he asks us a rhetorical question, that if there is this way of interpreting architecture, then can one attempt to contribute to architectural discourse? Tschumi is asking if architecture, Program, and event are all contributors to architecture itself then is there a need for the physicality of structure. This concept is demonstrated in his work of the transcripts where he demonstrates an understanding of the events that takes place in ‘The Manhattan Transcripts’. Where the architecture is defined by the events that happen to support the program and the program to support the events, ‘Parc De La Villette’ intentionally is designed by Bernard Tschumi to incorporate and address all expression and activity types. Therefore, in a clever way what he incorporates from his drawings into the reality dimension is a ‘Flexible space’ that like Derrida’s Deconstructive Theory becomes a state of flux for public space integrated with the presence of a building. To further this, the space is then deconstructed upon the superimposed layers of Lines, Points and Surfaces that explore the richness and discontinuity that exists within life, as well as being expressed into the conceptual drawings of the ‘Transcripts’ (Genel, 2019).

FIGURE 20. POINTS, LINES AND SURFACES

FIGURE 21. FOLIES DRAWINGS BY BERNARD TSCHUMI

FIGURE 20. POINTS, LINES AND SURFACES

FIGURE 21. FOLIES DRAWINGS BY BERNARD TSCHUMI

In relation to the drawings Tschumi incorporates and expresses the relationship between architecture and narrative by incorporating the ‘Folies’, ‘Grids’ and ‘programming’ suggesting a sense of order and narrative into a space. The way in which he uses this method in contrast to the drawings is by merging a range of recreational and cultural activities that also determine a sense of continuity within the space (As Seen in Fig. 22) (Genel, 2019). The way in which the ‘Folies’ occur in an unfinished manner is what implies to the user the feeling of continuity around a space in juxtaposition to the grid that serves a purpose of order and control or uncontrollable order in the park?

FIGURE 22. CONCEPTUAL DIAGRAM OF PARC DE LA VILLETTE STRATEGY - BY JACOB ROBERTS

FIGURE 22. CONCEPTUAL DIAGRAM OF PARC DE LA VILLETTE STRATEGY - BY JACOB ROBERTS

Conclusion

The understanding of Derrida’s Theories as contradicting as they may be, understands in depth the meaning behind the language we so effortlessly use. In a set way his meaning seems to be about giving our perceptions of language a constant state of flux in regard to the context that it is associated in or not in. Although the translations from Philosophical Deconstruction to Deconstructivism are conveyed through metaphorical interpretation they both still share the same qualities as to what they actually represent. They both share the curiosity to find the limits in order to achieve an antagonist role in both language and architecture and then ultimately push these limits towards a new dimension. As architects we are pioneers for creativity, exploration, and development, therefore, the exploration of the uncanny is most certainly a field that comes of great interest to the powerful minds we possess especially when they begin to question the very logic we deem as necessary to logical thinking in designing space.

The transgressions seem to explain that the translation is going against what we already know, finding its limits and questioning them to the extent of exceeding them but without destroying them, after all what is left to break once destroyed (Tschumi, 1996). As an understanding, what Tschumi’s transgressions state is that there is a ‘Nature of Space’ that is shown in his and Libeskinds conceptual drawings that contradict itself, the idea is finding new dimensions.

Based on my analysis it almost seems as if they refer to these new dimensions as ‘The Experience’. They aim to challenge the user to experience space in a different way, in using this concept the architect is offering a flux around the idea that the experience creates the context, consequently, the building is constantly in a ‘Deconstructive’ state, therefore, finished, but unfinished. This is where the transgressions contradict themselves, do both opposites need each other presence in order to reveal these concepts of emotion when designing space? The process behind waking these emotions in a space is where deconstruction takes a physical state. Both architects start to take away the structure, whether it is a building, formula, process or even a society, anything that is without structure feels loose, unstable and extends to this dimension of emotion and experience. Tschumi, tells us that society expects architects to domesticate their deepest fears to make our architecture feel safe, formal, and functional, but questions this states that by taking away structure we begin to allow users to apply themselves to a space in a different way without rules or boundaries (Tschumi, 1996).

FIGURE 23. CONCEPTUAL DRAWINGS OF STUDIO WORK - BY JACOB ROBERTS

FIGURE 23. CONCEPTUAL DRAWINGS OF STUDIO WORK - BY JACOB ROBERTS

In a comparison Libeskind does the same initial concept, awaking these feelings of danger and fragmentation throughout a space that presents itself as disorientating to the user, this way he uses the two opposite binaries to make the absence, present, and show the past in light of the future and the future in light of the past (Libeskind, 2001). Overall, his drawings try to conclude this as they set out to show what isn’t there – the new horizons and dimensions that he tries to incorporate, which is the experience created that can either past or future, absent and present but both opposites felt as a collective. By assembling the fragmented geometry in both drawings and physical constructs the feeling of uneasiness is what challenges the user to experience space in different way to complete the building.

At first, Deconstructivism almost seems to be a logical comparison to a ‘Black Hole’. However, to fully understand what it is, it seems one must first look inside total darkness to see light. But the analogy in this is that there must already be light in order to know that darkness there. It’s a different way of conceptualising our architecture and applying it to the way that we design space. It allows the users to become challenged when they enter a space, not to enter a space knowing exactly what its purpose is, but more to the point, the space that we as architects design can be interpreted and experienced in a way that allows the user and the designer to become relative to each other and have that freedom to experience space in our own way. To conclude, this essay addresses that there are many different ways that you can experience anything, the dimensions of space are endless. Are architects to govern if architecture is about physical structure and the function that takes place inside it or can we deconstruct the truth of a piece of architecture by taking away its structure to reveal its paradox; the experience of space¿

FIGURE 24. CONCEPTUAL DRAWINGS OF EVENTS AND POINTS OF INTENSITY FRAGMENTATION - STUDIO WORK - BY JACOB ROBERTS

FIGURE 24. CONCEPTUAL DRAWINGS OF EVENTS AND POINTS OF INTENSITY FRAGMENTATION - STUDIO WORK - BY JACOB ROBERTS

Bibliography

• Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia (2023, March 14) Jacques Derrida, Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Jacques-Derrida

• Capanna, Alessandra (n.d) Music and Architecture: A Cross between Inspiration and Method - Scientific Figure on ResearchGate. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Topological-transformation-of-the-Star-of-David-in-the-plan-of-Libeskinds-Berlin-Museum_fig5_226330569

• Genel (2021) From Object to Field, Lumos Maxima, Retrieved From; https://cansukokblog.wordpress.com/category/genel/

• Guignion, David (2020) What is Deconstruction? Jacques Derrida Keyword, Theory & Philosophy, in this episode, I try to explain provide an introduction to Deconstruction, Retrieved From; https://open. spotify.com/episode/3zfK5RozvsK7q9m9hF6mbi

• Lawlor, Leonard (2006) Stanford Encyclopaedia of Philosophy, Jacques Derrida, Revision (2021) Retrieved From; https://plato.stanford. edu/entries/derrida/

• Libeskind, D. (2001). Daniel Libeskind: the space of encounter. London: Thames & Hudson.

• Rajput, Darshika (2019) How Derrida’s theory inspired Deconstructiv-ism - Rethinking The Future, Rethinking the Future, Retrieved from; https://www.re-thinkingthefuture.com/rtf-fresh-perspectives/ a415-how-derridas-theory-inspired-deconstructivism/

• Stouhi, David (2020) What is Deconstructivism? ArchDaily, ISSN 0719-8884, Retrieved from; https://www.archdaily.com/899645/ what-is-de-constructivism

• Tschumi, Bernard (1994). The Manhattan Transcripts (New Edition) Academy Editions.

• Tschumi, Bernard (1996) Architecture and Disjunction, MIT Press, Cam-bridge, Massachusetts & London, England

• Wigley, Mark. (1993). The architecture of deconstruction: Derrida's Haunt. MIT Press. Retrieved from; https://search.ebscohost.com/login. aspx?direct=true&scope=site&db=nlebk&db=nlabk&AN=1377

• Young, J. E. (2000). Daniel Libeskind’s Jewish Museum in Berlin: The Uncanny Arts of Memorial Architecture. Jewish Social Studies, 6(2), 1–23 Retrieved From; http://www.jstor.org/stable/4467574

• Mandry, Sam (2013) Ordered Chaos: The Negotiation of Space in Deconstructivist Museum Buildings, Deconstruction Theory in Architecture. Retrieved from https://www.ukessays.com/essays/architecture/ museum-design.php?vref=1

• FIGURE 1. IMAGE OF DANIEL LIBESKIND, RETRIEVED FROM; https://www.bnaibrith.org/ visualizing-history-and-hope-daniel-libeskind/

• FIGURE 2. IMAGE OF BERNARD TSCHUMI, RETRIEVED FROM; https://www.forbes.com/ sites/yjeanmundelsalle/2015/09/07/bernard-tschumis-architecture-is-not-just-aboutspace-and-form-but-also-the-events-happening-inside/?sh=73fa17e37605

• FIGURE 3. IMAGE OF JACQUES DERRIDA, RETRIEVED FROM; https://contemporarythinkers.org/jacques-derrida/biography/

• FIGURE 4. THE MANHATTAN TRANSCRIPTS, RETRIEVED FROM; https://www.pinterest. co.uk/pin/412220172115726292/

• FIGURE 5. THE MICROMEGAS, RETRIEVED FROM; https://libeskind.com/work/micromegas/

• FIGURE 6. THE MICROMEGAS ANNOTATED – BY JACOB ROBERTS

• FIGURE 7. THE TRANSCRIPTS ANNOTATED – BY JACOB ROBERTS

• FIGURE 8. THE TRANSGRESSIONS, RETRIEVED FROM; https://www.archiwik.org/index. php/File:Tschumi002.jpg

• FIGURE 9. BREAKING THE TRANSGRESSIONS QUOTE, RETRIEVED FROM; https:// designmanifestos.org/bernard-tschumi-advertisements-for-architecture/

• FIGURE 10. MT 4 “THE BLOCK” BY BERNARD TSCHUMI, RETRIEVED FROM; (Book) Tschumi, Bernard (1994). The Manhattan Transcripts (New Edition) Academy Editions.

• FIGURE 11. LIBESKINDS MICROMEGAS, RETRIEVED FROM; https://libeskind.com/work/ micromegas/

• FIGURE 12. MT 4 “THE BLOCK” – ANNOTATED BY JACOB ROBERTS

• FIGURE 13. TRANSCRIPTS MOVEMENT CONCEPTUALIZATION, RETRIEVED FROM; https://publication.avanca.org/index.php/avancacinema/article/view/185/360

• FIGURE 14. IMAGE OF JEWISH MUSEUM, BERLIN, RETRIEVED FROM; https://www.archdaily.com/91273/ad-classics-jewish-museum-berlin-daniel-libeskind

• FIGURE 15. STAR OF DAVID DECONSTRUCTION DIAGRAM – BY JACOB ROBERTS

• FIGURE 16. JEWISH MUSEUM PLAN, RETRIEVED FROM; https://www.archdaily. com/91273/ad-classics-jewish-museum-berlin-daniel-libeskind/5afa58a3f197cc59f700001f-ad-classics-jewish-museum-berlin-daniel-libeskind-ground-floor-plan

• FIGURE 17. MOVEMENTS BETWEEN THE LINES, RETRIEVED FROM; https://artcom.de/ en/?project=composing-the-lines-2

• FIGURE 18. FOLIES OF PARC DE LA VILLETTE, RETRIEVED FROM; https://www.dezeen. com/2022/05/05/parc-de-la-villette-deconstructivism-bernard-tschumi/

• FIGURE 19. PARC DE LA VILLETTE CONCEPTUAL DRAWINGS, RETRIEVED FROM; https://www.domusweb.it/en/reviews/2014/08/19/bernard_tschumi_at_pompidou. html

• FIGURE 20. POINTS, LINES AND SURFACES, RETRIEVED FROM; https://yalestories. wordpress.com/2013/02/27/discussing-bernard-tschumi/

• FIGURE 21. FOLIES DRAWING BY BERNARD TSCHUMI, RETRIEVED FROM; http://architecture-design-mannager.blogspot.com/2014/07/book-review-two-tschumi-titles. html

• FIGURE 22. CONCEPTUAL DIAGRAM OF PARC DE LA VILLETTE STRATEGY - BY JACOB ROBERTS

• FIGURE 23. CONCEPTUAL DRAWINGS OF STUDIO WORK – BY JACOB ROBERTS

• FIGURE 24. CONCEPTUAL DRAWINGS OF EVENTS AND POINTS OF INTENSITY FRAGMENTATION - STUDIO WORK - BY JACOB ROBERTS

Figure List

¿

FIGURE 1. DANIEL LIBESKIND

FIGURE 2. BERNARD TSCHUMI

FIGURE 3. JACQUES DERRIDA

FIGURE 1. DANIEL LIBESKIND

FIGURE 2. BERNARD TSCHUMI

FIGURE 3. JACQUES DERRIDA

FIGURE 4. MANHATTAN TRANSCRIPTS

FIGURE 5. MICROMEGAS

FIGURE 4. MANHATTAN TRANSCRIPTS

FIGURE 5. MICROMEGAS

FIGURE 6. MICROMEGAS ANNOTATED - BY JACOB ROBERTS

FIGURE 7. TRANSCRIPTS ANNOTATED - BY JACOB ROBERTS

FIGURE 6. MICROMEGAS ANNOTATED - BY JACOB ROBERTS

FIGURE 7. TRANSCRIPTS ANNOTATED - BY JACOB ROBERTS

FIGURE 9. TRANSGRESSIONS BREAKING

FIGURE 9. TRANSGRESSIONS BREAKING

FIGURE 12. TRANSCRIPTS ANNOTATED - BY JACOB ROBERTS’

FIGURE 13. TRANSCRIPTS CONCEPTUALISATION

FIGURE 12. TRANSCRIPTS ANNOTATED - BY JACOB ROBERTS’

FIGURE 13. TRANSCRIPTS CONCEPTUALISATION

FIGURE 14. IMAGE OF JEWISH MUSEUM, BERLIN

FIGURE 15. STAR OF DAVID DECONSTRUCTION - BY JACOB ROBERTS

FIGURE 16. JEWISH MUSEUM PLAN

FIGURE 17. MOVEMENT BETWEEN THE LINES

FIGURE 14. IMAGE OF JEWISH MUSEUM, BERLIN

FIGURE 15. STAR OF DAVID DECONSTRUCTION - BY JACOB ROBERTS

FIGURE 16. JEWISH MUSEUM PLAN

FIGURE 17. MOVEMENT BETWEEN THE LINES

FIGURE 18. FOLIES OF PARC DE LA VILLETTE

FIGURE 19. PARC DE LA VILLETTE CONCEPTUAL DRAWINGS

FIGURE 18. FOLIES OF PARC DE LA VILLETTE

FIGURE 19. PARC DE LA VILLETTE CONCEPTUAL DRAWINGS

FIGURE 20. POINTS, LINES AND SURFACES

FIGURE 21. FOLIES DRAWINGS BY BERNARD TSCHUMI

FIGURE 20. POINTS, LINES AND SURFACES

FIGURE 21. FOLIES DRAWINGS BY BERNARD TSCHUMI

FIGURE 22. CONCEPTUAL DIAGRAM OF PARC DE LA VILLETTE STRATEGY - BY JACOB ROBERTS

FIGURE 22. CONCEPTUAL DIAGRAM OF PARC DE LA VILLETTE STRATEGY - BY JACOB ROBERTS

FIGURE 23. CONCEPTUAL DRAWINGS OF STUDIO WORK - BY JACOB ROBERTS

FIGURE 23. CONCEPTUAL DRAWINGS OF STUDIO WORK - BY JACOB ROBERTS

FIGURE 24. CONCEPTUAL DRAWINGS OF EVENTS AND POINTS OF INTENSITY FRAGMENTATION - STUDIO WORK - BY JACOB ROBERTS

FIGURE 24. CONCEPTUAL DRAWINGS OF EVENTS AND POINTS OF INTENSITY FRAGMENTATION - STUDIO WORK - BY JACOB ROBERTS