In January 1974, at the Academy of Music, New York City, a nervous manager, Clifford Davis, announced the arrival of the band Fleetwood Mac on stage, only not one of the original line-up appeared. It was a completely fake Fleetwood Mac. Unsurprisingly, the crowd was not amused. This scene highlights the incredible journey of a band that had more personnel changes than hot baths in the early days, and found themselves at one stage not even in the band at all. It’s a fascinating study in how a band can evolve through changes as extreme as this and still retain its music and its fans.

Despite the turmoil, Fleetwood Mac would achieve platinum sales with several of their albums, and would eventually be enrolled in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. They played a pivotal role in popularizing the blues in the late sixties, and certainly ‘Rumours’ and ‘Tango in the Night’ provided the backdrop to many people’s

lives and loves in the eighties. During the intervening years they turned out superb albums that have stood the test of time and were created using some of the most talented songwriter teams of the era.

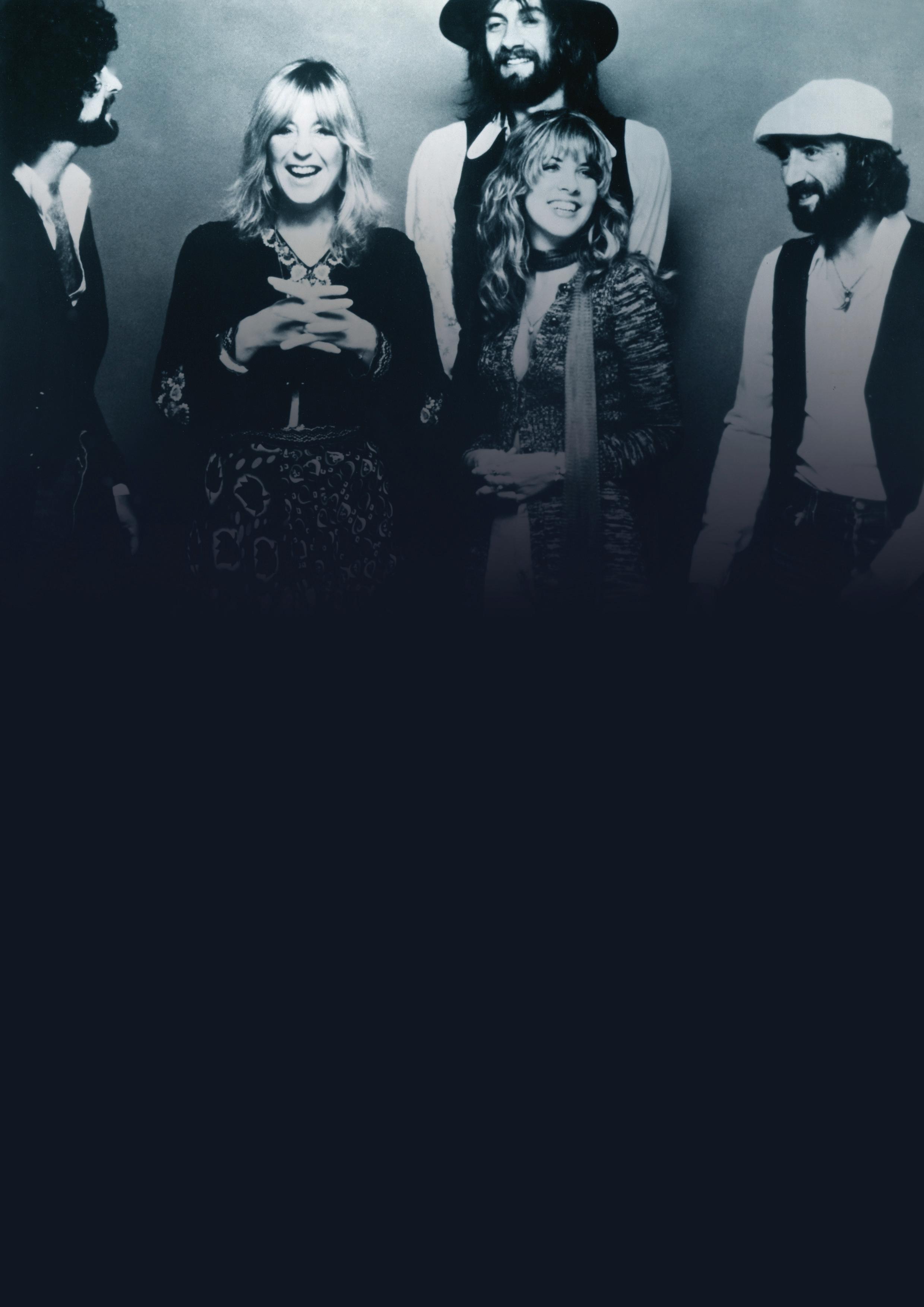

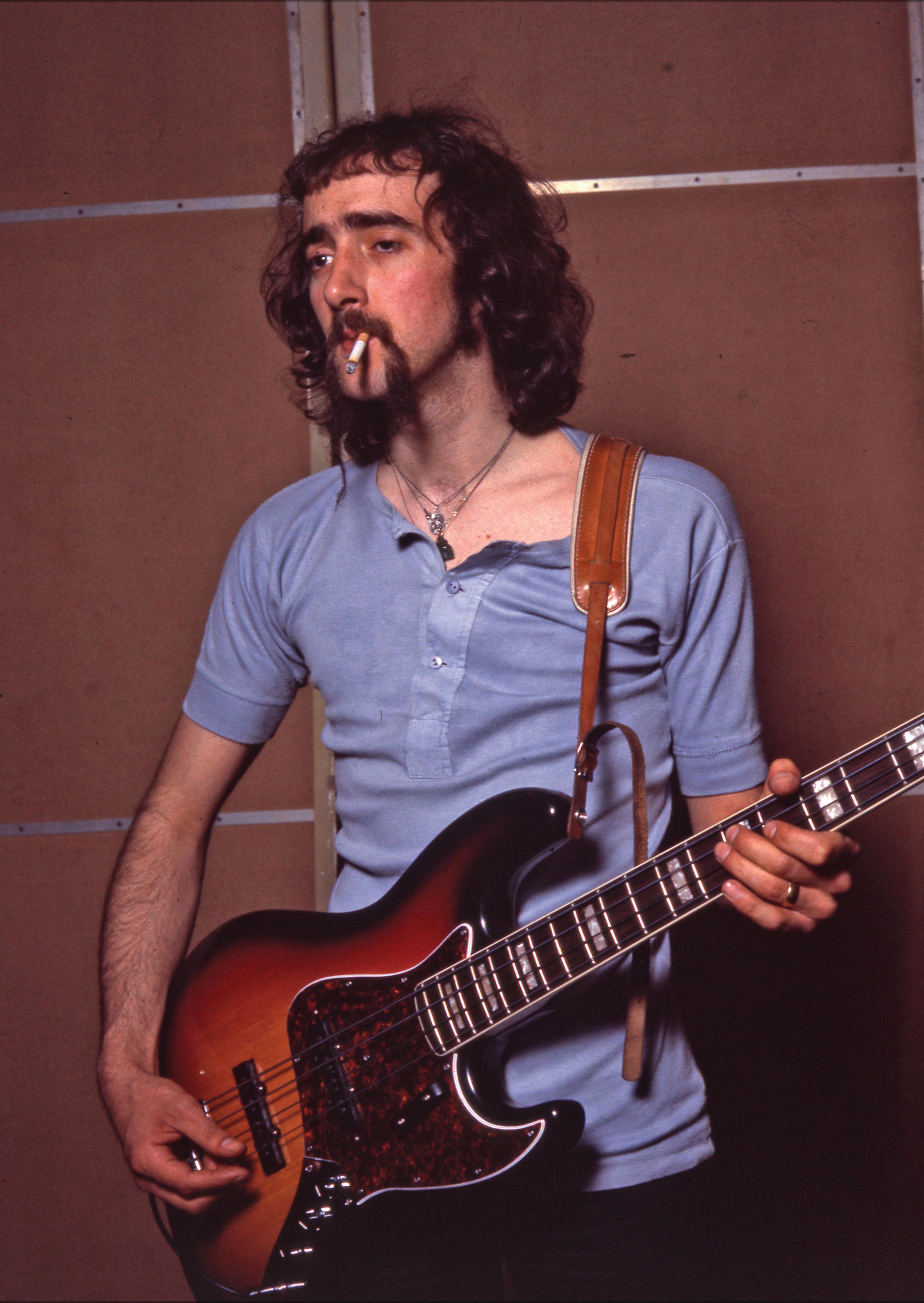

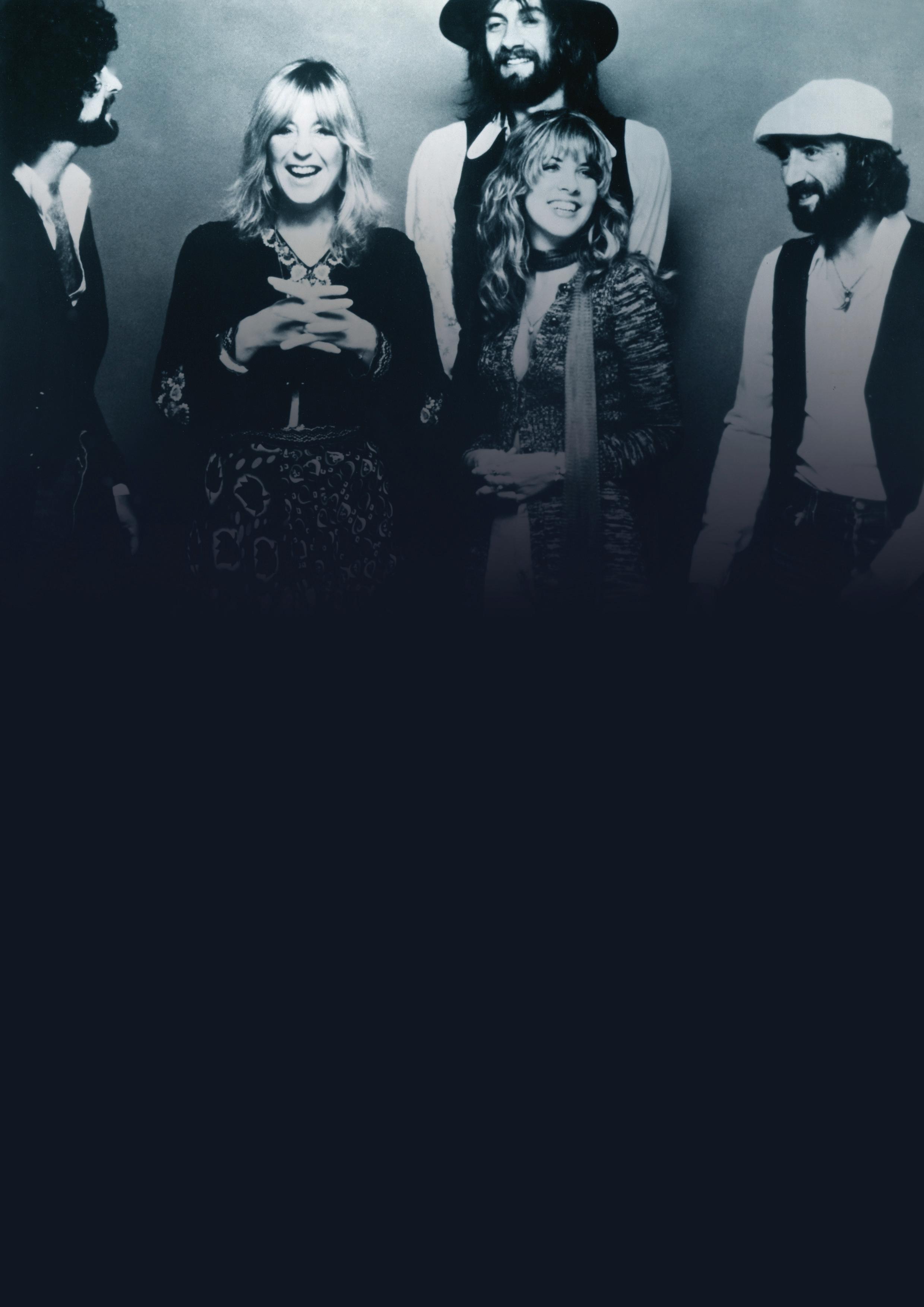

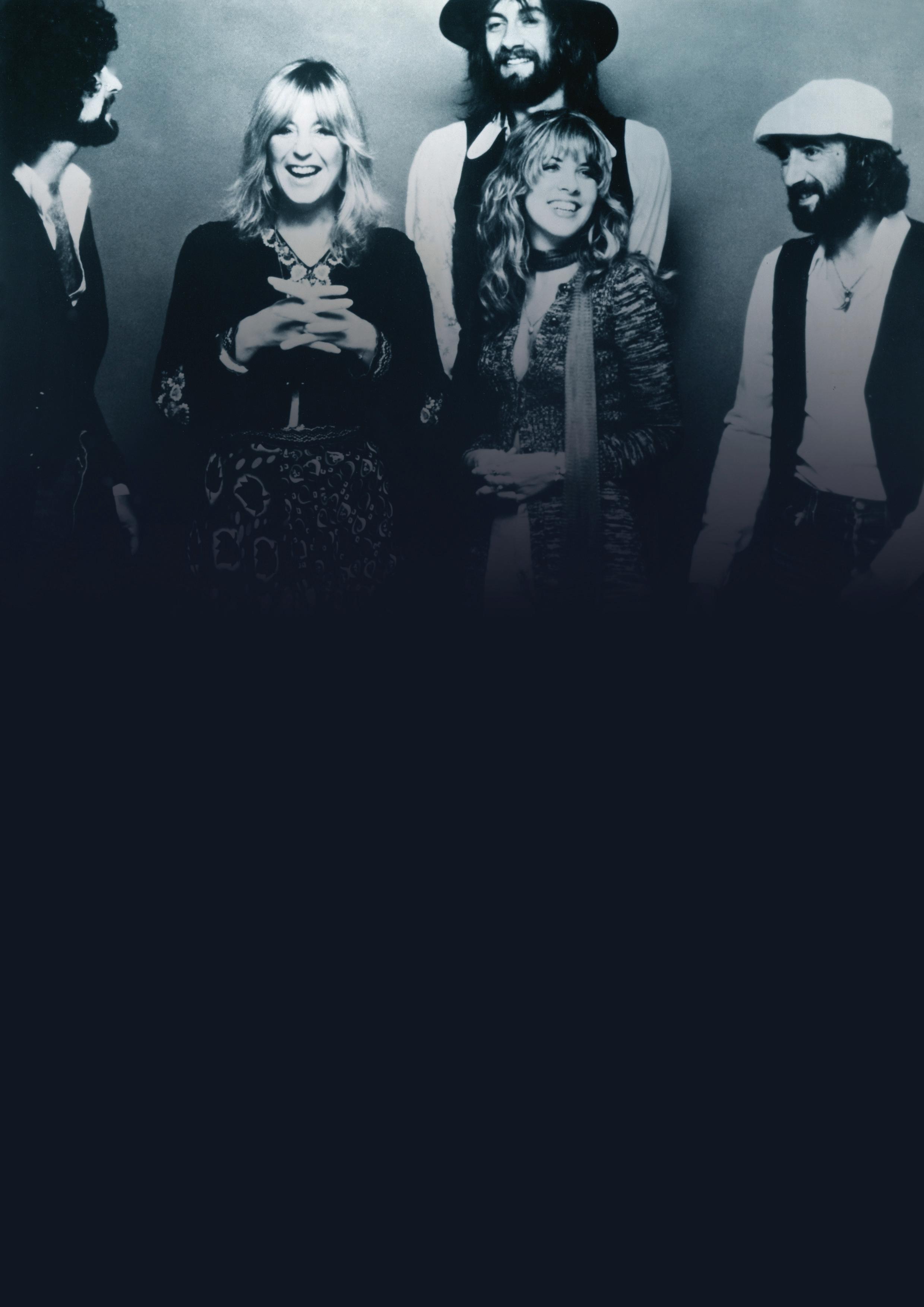

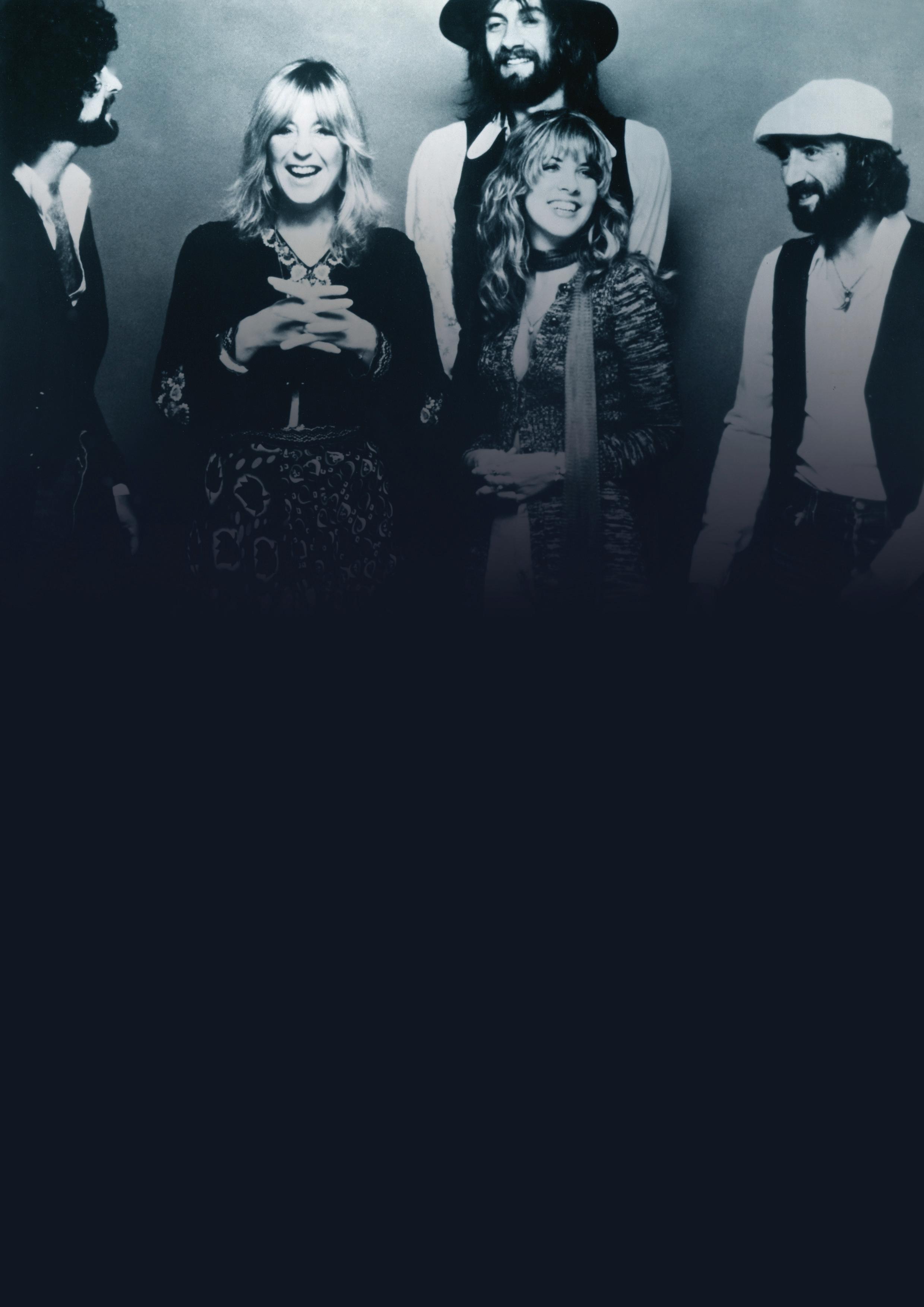

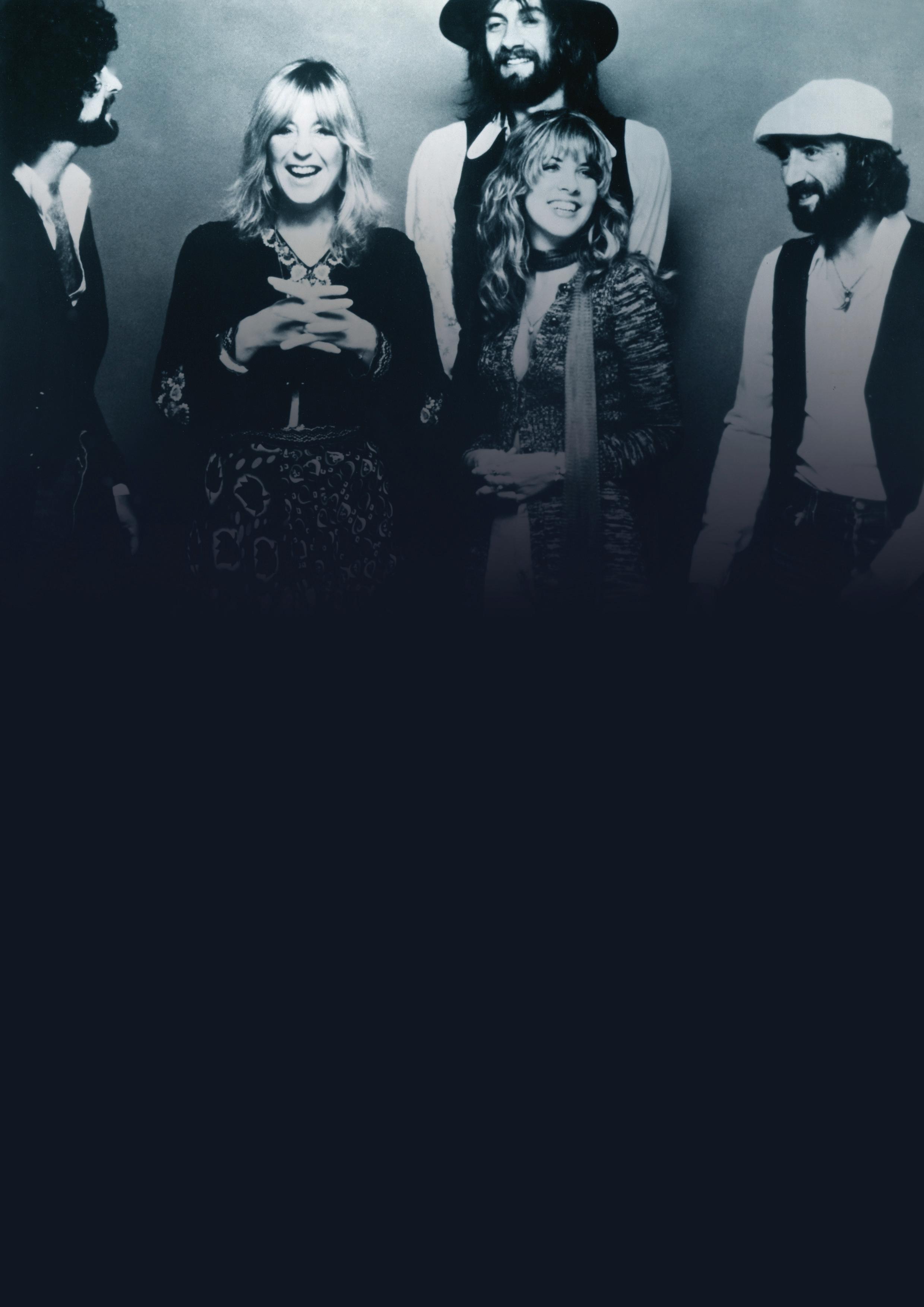

Amidst the band’s numerous changes, two of Fleetwood Mac’s main characters have been at the centre since day one, lending some continuity to the twists and turns of this story. They are Mick Fleetwood, providing the drums and the Fleetwood, and John McVie, adding the bass and the Mac.

These two would occupy a strange role as band leaders, with Mick Fleetwood often being touted as the figurehead, whilst neither of them were the principal songwriters. As successful bands go, it’s an un unusual arrangement, because it’s often the band members who write the songs that determine the direction a group goes, and it pays credit to the strength of Fleetwood Mac’s rhythm section that they’ve managed to retain some of the original essence of the band throughout the years.

The musical evolution of Fleetwood Mac is what makes their story so interesting. Having lived through the social changes that accompanied the music, I can attest that they were a credible reflection of what was happening in youth culture during the ’60s, ’70s and ’80s, but change is not always so readily accepted by the die-hard purist fans who want a band to remain as they were when they first discovered them. This was particularly true of the British fans of their early blues period, who wanted the band to stick with the blues and nothing but the blues.

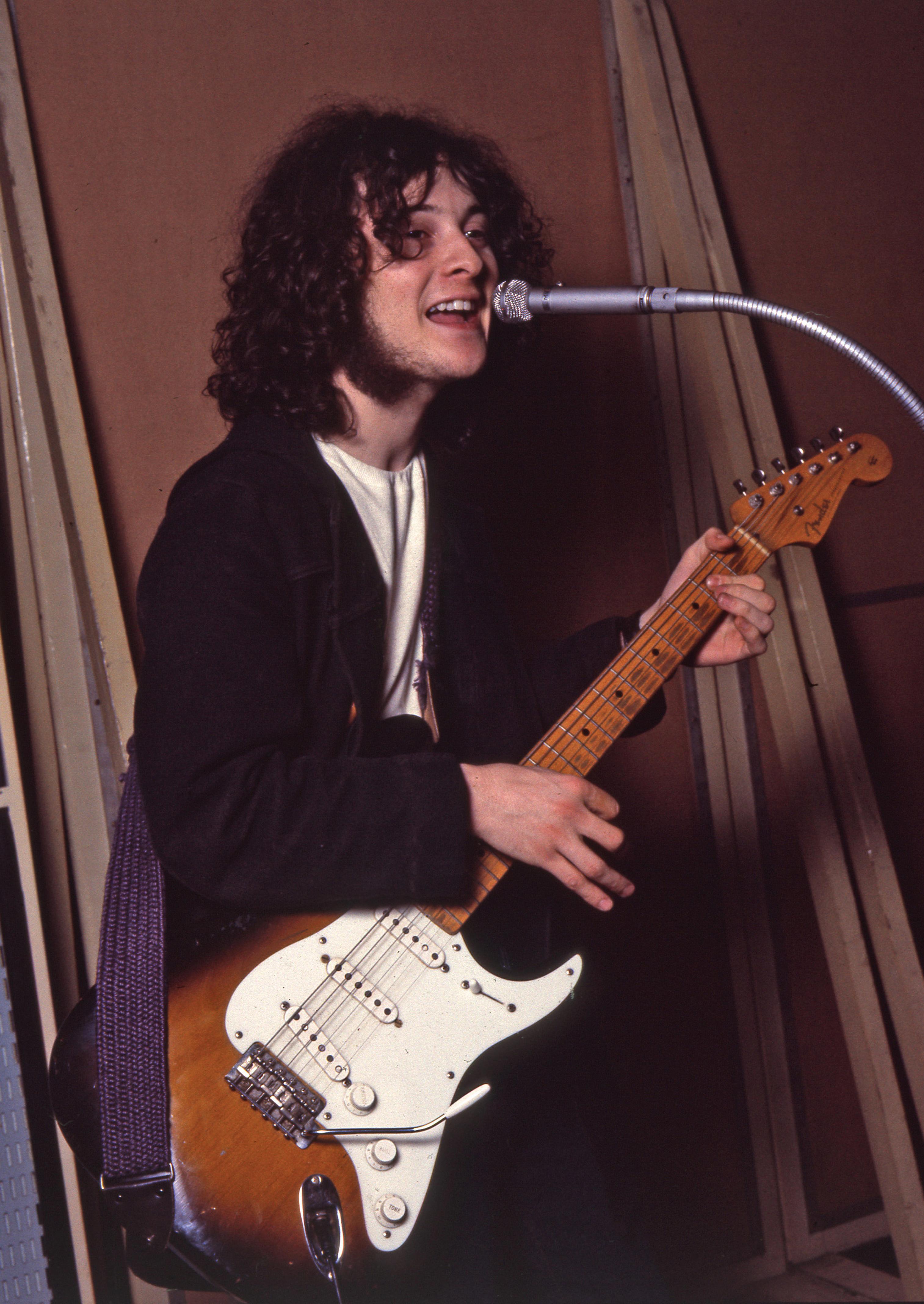

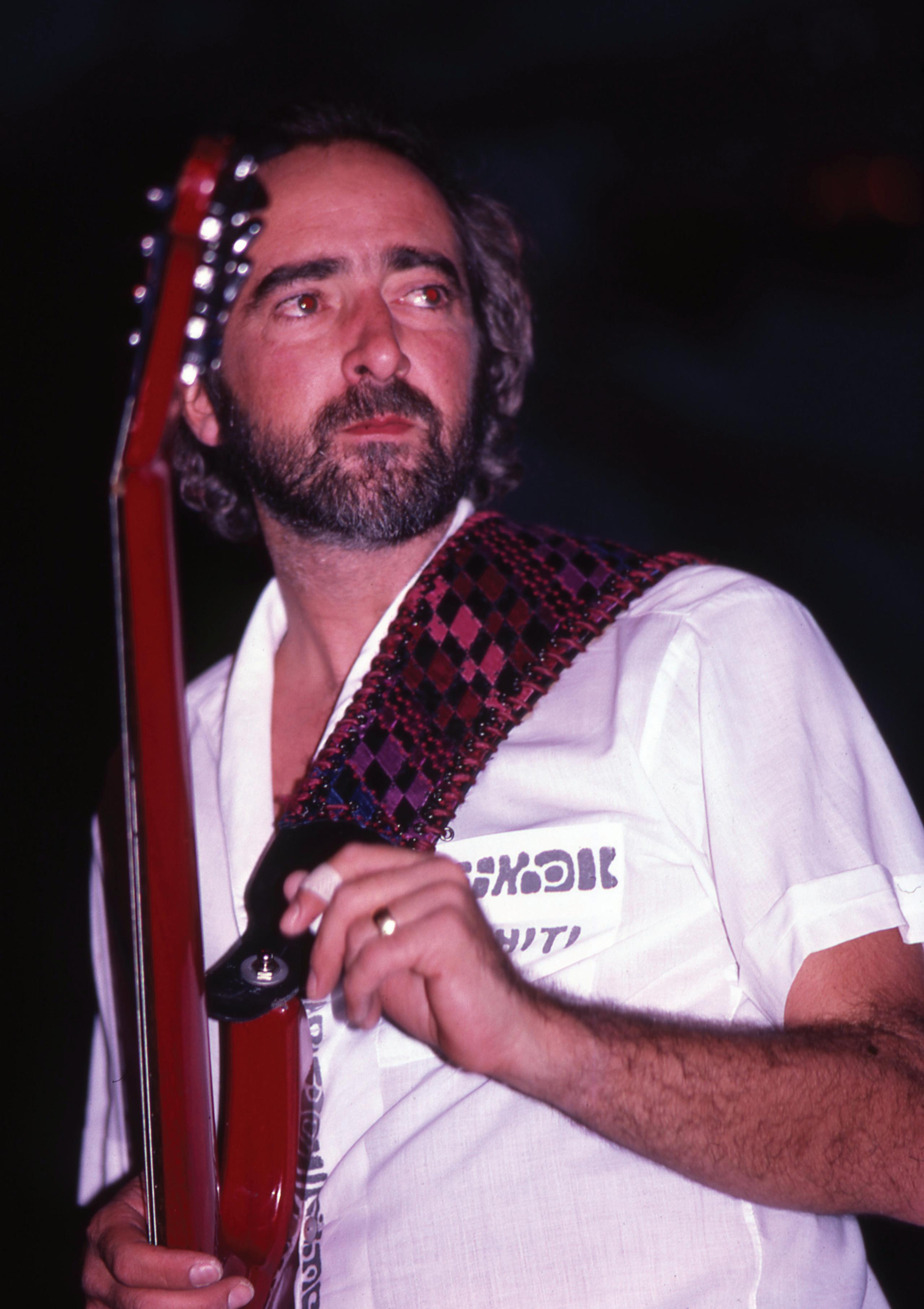

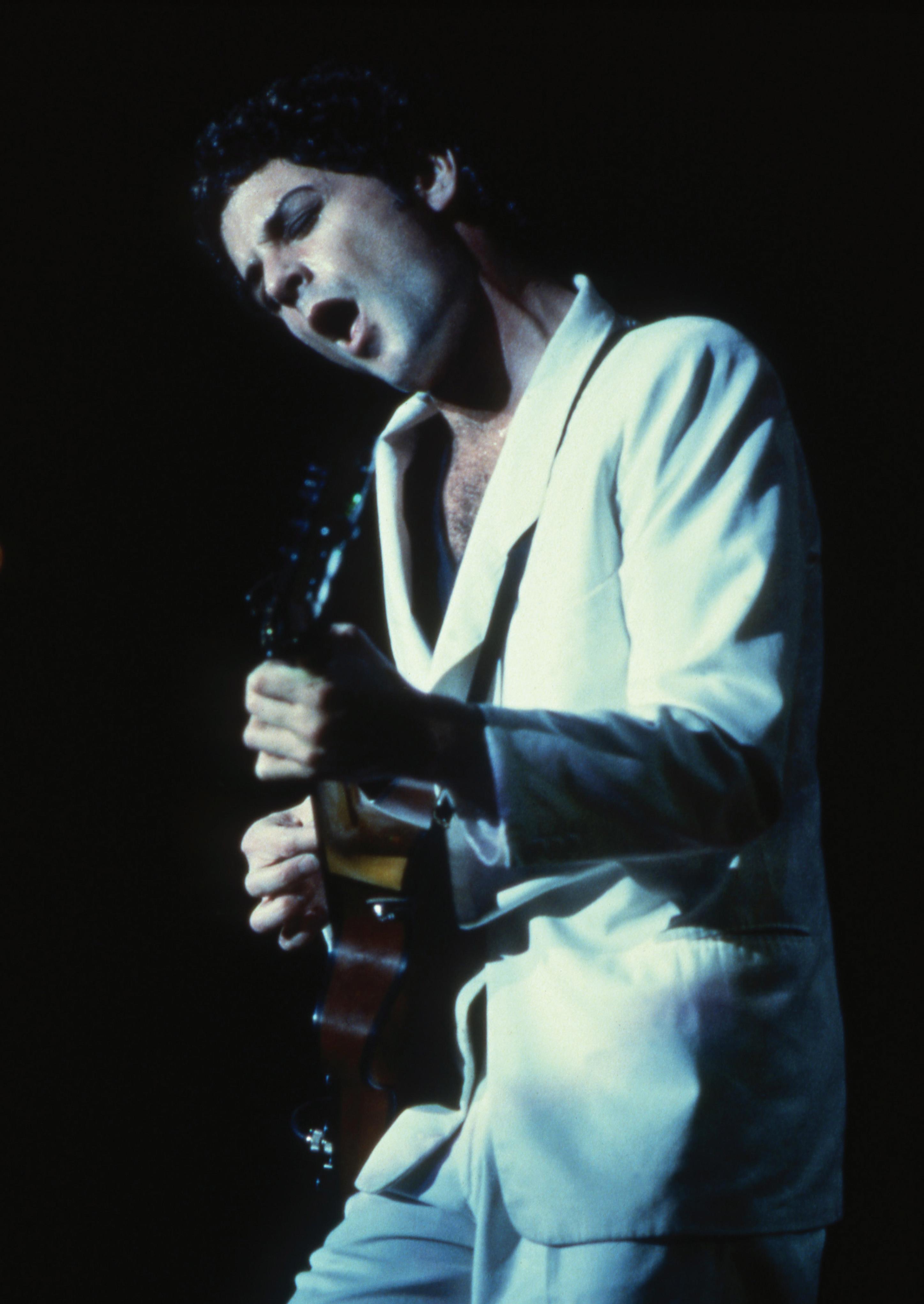

This might have been possible, except for the demise of the other key player in the genesis of Fleetwood Mac, Peter Green. He was the initial visionary who stamped the blues trademark riffs on the band’s first recordings. He was by far the most accomplished technical musician at the time, but, more importantly, he had the gift of really being able to get across the feel of the music, which is so important in the blues. He had an innate sensitivity in his

guitar playing, and this gave the early incarnations of Fleetwood Mac the edge on other blues bands of that era, of which there were plenty.

Peter Green was the captivating force that ignited Fleetwood Mac’s fire, but the heat of fame and stardom sadly just proved too much for him. Coupled with some disastrous experiences on hallucinogenic drugs, he buckled under the strain and was lost to the world for 20 years. Strangely enough, his story echoes that of Brian Jones of the Rolling Stones in that he provided that allimportant belief and direction at the start, only to be manipulated away from centre stage and left to lick his wounds. Luckily, Peter Green managed to escape the chemical monster that claimed Brian Jones, and he has carved out a solo career in recent years.

The birth of Fleetwood Mac began, as did so many bands in the sixties, in the arms of another band. In April 1967 John Mayall, the keyboard player and singer-songwriter of the Bluesbreakers, brought Peter Green, Mick Fleetwood, and John McVie all together for the first time. Mayall had just lost his guitarist, one Eric Clapton, who had decided to pack all his troubles and a bunch of musicians and head off south to Greece for a while. This trip was always assumed to be a temporary departure, and the worship of Clapton’s followers was so strong that he resumed his place in the band on his return. His return did spell the end of Green’s temporary stint in the band, but Green had gone down well with the fans, and Mayall never forgot the favour.

Peter Green was born Peter Greenbaum in October 1946. His first band, a covers outfit called Bobby Denim and the Dominoes, eked a living rolling out all the usual rock and pop hits of the time, but Peter’s real passion was the blues, in particular the blues guitarists and singers from the depressed southern states of America. His favourites were B.B. King, Muddy Waters, John Lee Hooker, and Howlin’ Wolf. These musicians inspired many of the great bands that came out of the sixties, including Brian Jones and

Keith Richards of the Rolling Stones, who have cited these blues legends as their guitar heroes.

Green joined John Mayall, and together they recorded an album called ‘A Hard Road’. They were joined by Aynsley Dunbar on drums whilst John McVie held the bass. This album aptly demonstrates Peter’s skills on guitar, and one track, ‘Supernatural’, bears all the hallmarks of the Fleetwood Mac sound still to be incarnated. The arrival of Mick Fleetwood coincided with Aynsley Dunbar going off to work on solo projects two months after the album was completed. Fleetwood didn’t last long, though, as Mayall was a formidable taskmaster as band leader, and he sacked him for getting drunk. As if that wasn’t enough, an argument between Green and Mayall prompted Green to quit the band. He eventually followed Fleetwood into another band, which also acted as midwife to Fleetwood Mac. This was Peter Barden’s band, amusingly called The Looners.

Still, all along the road – and it was a long bumpy road in the back of beaten-up old vans from gig to gig, with a mattress if you were lucky – Peter Green was dreaming of his own vision for a band, one that would better reflect his musical heritage and give him more prominence in the mix. Ironically, he latched onto the name of one of the instrumentals all three musicians had been involved with in the Bluesbreakers, which was called ‘Fleetwood Mac’. With typical humility, Green never angled for his name to be up there in lights. Whether it was part of his medical condition or not, Green’s humility and generosity towards other people was legendary, with it only needing a mention that somebody liked something for him to give it to them. This generosity came at a cost, though, as many of Green’s guitars disappeared to hangers-on and opportunists.

The final place in this emerging quartet was provided by Mike Vernon, a producer for the Decca label who doubled up as a talent scout for the band. It was while he was on a jaunt to Birmingham

in search of talent that he came across a local blues outfit called the Levi Set Blues Band, most of whom were not yet up to London standards of playing, except for the diminutive guitarist, who had a penchant for sounding like Elmore James, the legendary bottleneck blues performer. When Vernon played the audition tapes of this band to Green, he nearly jumped out of his seat, grabbed the keys to the band’s van and went out to nab the guy. Less than a week later, Jeremy Spencer was fully enrolled in Fleetwood Mac and the band was officially born.

Although Green had chosen the members of his band, he hadn’t quite managed to secure them all. John McVie was reluctant to give up the security of regular work with John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers, a well-reviewed band with plenty of gigs lined up, so temporary stand-in Bob Brunning was brought in on bass, and rehearsals began for an upcoming tour from September to December 1967. Before the tour kicked off, the band played its rite-of-passage gig, the first official Fleetwood Mac engagement, at the Windsor Jazz and Blues Festival. This weekend of unbridled frivolity would eventually move west to become the Reading Festival.

As the tour progressed, McVie heard good reports and decided he wanted to join the band full time. Brunning graciously stepped aside and went on to carve himself a respectable career as a teacher, while still finding time to work on records.

So, at last, the group assembled in the bleary dawn of 1968 and set about carving out their slice of musical history.

The first album was recorded in a couple of days, on a budget that was not so much minimal as next to nothing. Called ‘Peter Green’s Fleetwood Mac’, it was an unashamed attempt to capitalise on Green’s growing reputation as one of Britain’s outstanding blues guitarists, and for good reason. Without his remarkable playing, there is no reason why Fleetwood Mac should ever have popped their heads up above the parapet of mediocrity. Bands like the

Animals and the Rolling Stones, performers like Alexis Korner and Eric Clapton, had all played their part in a growing number of fans enjoying this white man’s version of Black American blues. Acts still had to be world-class to cut the mustard. Then there was that guy Jimi Hendrix, who, just when you thought you’d mastered the technique, came along and re-wrote the rules on playing the guitar, or rather, set fire to them.

To some extent, Fleetwood Mac owed their early success to factors outside their control. Britain’s top bands were playing the blues, the phenomenon of Jimi Hendrix brought blues to the masses, and the whole blues genre was enjoying something of a popular revival in Britain at the time. Musicians are so often prey to what is actually happening in the wider spectrum of music that events way beyond their control can determine whether an album is going to be a success or not. It was definitely on the back of this rising tide of blues-inspired music that ‘Fleetwood Mac’ hit the

charts with resounding results. The band members must have been aware that they were at the mercy of the fickle winds of change, for when the album was released in February 1968 and shot into the charts, no one was more surprised than the band itself.

A combination of some positive music reviews and Peter Green’s awesome guitar work catapulted the album ‘Peter Green’s Fleetwood Mac’ into the Top 5. It remained in the Top 10 for another fifteen weeks. With the lads doing endless rounds of gigs to plug the album, it would be a year before it eventually dropped out of the Top 20. In the late sixties, this was an incredible feat, as most albums in those days needed one or two chart toppers to bring the band into every radio playlist, and therefore into the public’s record collection.

Fleetwood Mac had actually tried this conventional route the previous year, releasing their debut single, ‘I Believe My Time Ain’t Long’, just before Christmas. The title was certainly a premonition of better things to come, but the Jeremy Spencer version of this Elmore James classic just fell flat on its face.

I think that had they put out a Peter Green original composition the first single might have done better. The problem with the Elmore James number was that it didn’t allow the talents of the whole band to shine through. Jeremy Spencer was renowned as an Elmore James devotee, and the group’s management might have been better advised to release this as a solo effort.

When Mike Vernon, the band’s manager, sat down with Green to discuss the second single from the band, they unanimously decided that it had to be one of Green’s songs to display his burgeoning talent as a writer and to feature his guitar-playing up front. The resulting song was the awesome ‘Black Magic Woman’, which, although it only enjoyed modest chart success for Fleetwood Mac, went on to be a huge hit for Carlos Santana in the States. This success across the pond was the first of many for Fleetwood Mac, and foretold the way things would generally pan

out in the years to come, that releases which bombed in the UK would go stratospheric in the States, and vice versa.

With the relative success of their first album, Vernon dipped into the coffers of his Blue Horizon record label and, utilizing the talents of the Gunnel Brothers, who did all his concert bookings, he sent the band off to Scandinavia on a short tour. He also began to secure them more radio airplay and their first TV broadcasts. Radio One recorded the band’s debut on Live Session in the Studio on 16 and 17 January, 1968.

Fleetwood Mac had arrived, or more accurately, given their heavy gig schedule, it was more like, ‘Fleetwood Mac have just left the building.’

With the spring tour over and the band firmly ensconced back in beer-bleary Blighty, it was time to think about feeding the beast, the record label, which was baying for the next album. Although signed to Blue Horizon, Fleetwood Mac were under the wider umbrella of CBS, whose main aim was of course to maximize sales and distribute the merchandise as widely as possible.

The question was, what would be the follow-up to ‘Peter Green’s Fleetwood Mac’? The band was at a stage that nearly all bands find themselves – that is, they had been kicking around for endless years fine-tuning their sound, only to put all their best work into that all-important first break. Then, if it makes any headway, or, more importantly, any money, they find record company executives breathing down their necks crying out for the next hit. Unfortunately, a band doesn’t have the luxury of a lifetime on its hands, and has to turn out in six months what had previously taken six years.

Fortunately for Fleetwood Mac, much of the first album had contained cover songs written by other artists, so it seemed good sense for their next album to be one that featured more of the group’s self-penned songs and that made better use of Green’s songwriting abilities.

The album was to be named ‘Mr Wonderful’, and in an attempt to recreate some of the authentic sound of the early blues musicians, the band, with producer Mike Ross, deliberately dumbed down the sound and ruffled the edges of the recording process to make it sound dirty, as if they’d just walked into one of those old Alabama studios with one dodgy microphone and too many cockroaches. They even committed such heresies as putting the vocals through a Vox amplifier before the mixing desk, and purposely distorting the guitars, turning the volume knob way past eleven, to get that edgy feel.

Despite the band wading through these muddy waters, they still managed to cut it with their collective talents, and on its release in August 1968, ‘Mr Wonderful’ climbed steadily up the UK charts to peak at a nicely respectable number four. Again, this was a major achievement for any new band, especially one that was not mainstream pop and was definitely trying to hang on to its integrity and credibility as a blues outfit. Earning respect as a blues player was probably harder than in most genres of music because the blues audience demanded total authenticity. No charlatans need apply. However, having won the hearts of this discerning audience, it was to be the cause of much anguish later on when the band began to veer away from hard-core blues and into the murky mire of R&B, and onwards towards the slippery slopes of – dare I say it – pop.

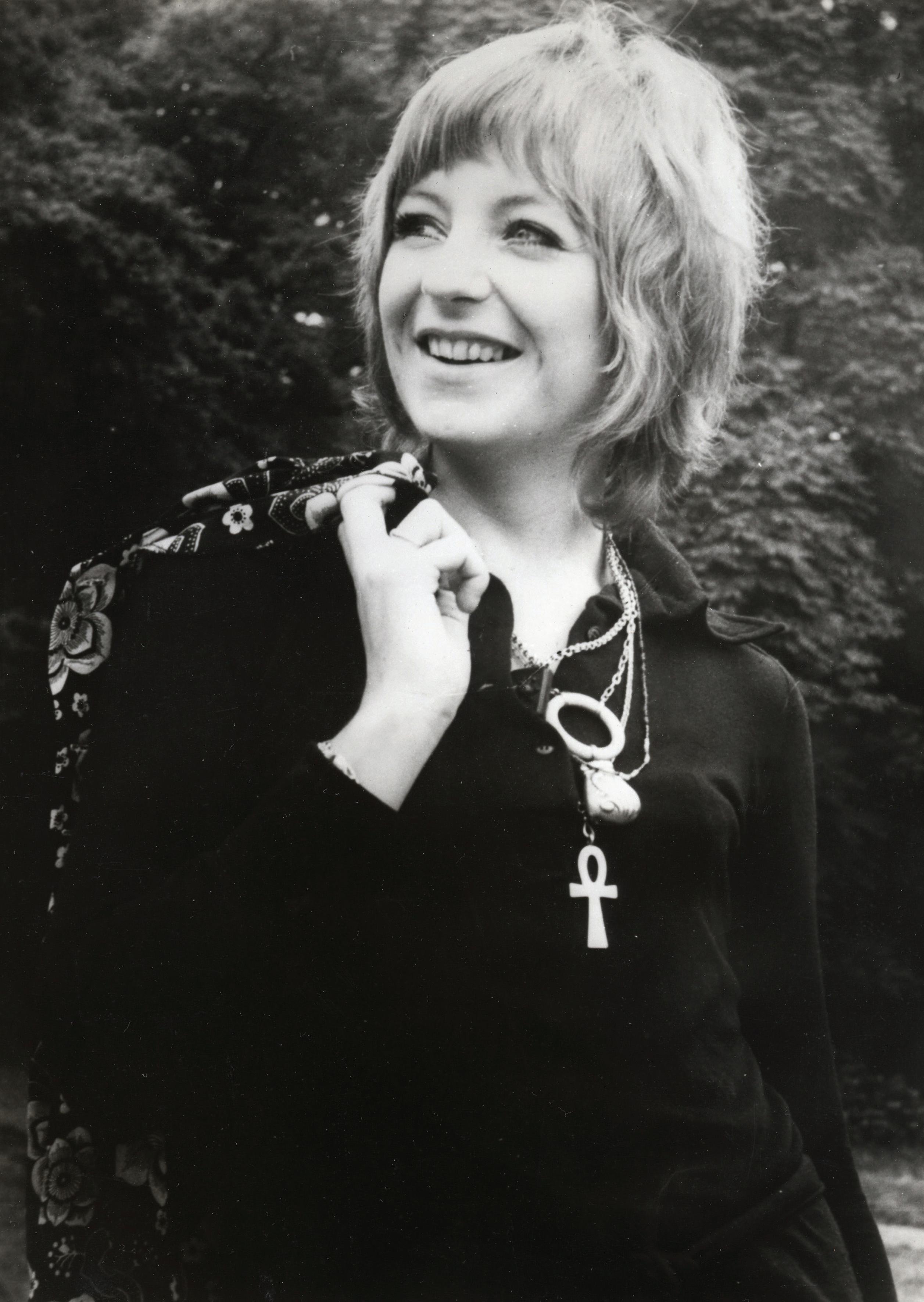

Those days were yet to come, however, so in the meantime Fleetwood Mac concentrated on the next hurdle they had to overcome, their first tour of America – the home of the blues. There was one guest artist, or perhaps artiste, who featured on ‘Mr Wonderful’, which was the Miss Wonderful, Christine Perfect. She was John McVie’s girlfriend at the time and quite a prodigious talent on keyboards and vocals. Her temporary inclusion was to become permanent a short while later when she eventually exchanged the title Miss Perfect for Mrs McVie.

Strangely, the summer tour of America wasn’t on this occasion the amazing trip they’d been hoping for. The first single and album had been released on the Epic label, but most members of the band felt they had done little to promote it successfully. The American management didn’t seem to grasp how well the band had been doing in England and gave them some lousy graveyard slots supporting bands that they would have run rings around back home. However, no visit to the States for any British band was a completely lost cause, as it gave the boys a chance to catch up with the real blues players of the day. So Peter Green was able to meet Buddy Guy and Howlin’ Wolf. He also met The Grateful Dead and Janis Joplin, all of whom made a tremendous impression on him.

Despite their underwhelming tour of the US, they did return to some good news. Their third single, the Little Willy John song, ‘I Need Your Love So Bad’, had scored a reasonable hit and was getting airplay on some of the more mainstream pop radio programmes.

Despite the success of their first two albums and the relative headway the singles were making, Green wasn’t one to rest on his laurels. He started thinking about ways to expand the band’s sound and make it more interesting. He also read the riot act to the Gunnel Brothers, as he felt they weren’t pushing hard enough to get them gigs, while at the same time he hijacked one of their employees, Clifford Davis, to be their manager.

Green’s instinct was fairly astute, and having got Davis on his side, he sent him down to see the Gunnel Brothers to rattle their cage a bit. As it happened, he did rather more than that. Unfortunately, the discussions quickly escalated into an argument that Davis succinctly won – by delivering a knockout blow to one of the brothers. Luckily, Fleetwood Mac’s management also turned out to be a black belt in bargaining, which in practical terms meant that Davis had a reputation in the business that was

watertight and strong as titanium. His reputation would later prove a useful card to play when dealing with aggressive music-industry heavyweights.

Green didn’t want to end his long love affair with the blues, but he had a prophetic inkling that if he wanted to avoid stagnating, he needed to expand the band’s musical territory. He achieved this by bringing in Danny Kirwan, whose previous incarnation had been with a band called Boilerhouse, on guitar. Realising that Kirwan had more talent than the rest of Boilerhouse put together, Green didn’t feel too guilty about poaching him for Fleetwood Mac.

At only 18 years old, Kirwan’s wide musical tastes exceeded his years. He swung from the guitar playing of Hank Marvin to, perhaps more importantly, the famous French gypsy guitarist Django Reinhart. Bringing in somebody who wasn’t blues, born and bred, was an inspired leap of faith for Fleetwood Mac, and began the transition that would eventually catapult them out of the blues and into mega-stardom as more mainstream performers. Had any of the band members known what a fury their gradual shift from blues to pop would cause, they might well have dumped Kirwan in the nearest canal, no questions asked, but as it was, their naïvety protected them from such worries. For the time being, they bravely sauntered into whichever musical grove looked most appealing, the result of which was perhaps one of the most inspired lateral choices for a single any so-called blues band ever released. It broke most of the rules in the book, being an instrumental for starters. It was also about as far removed as they could get from anything the band had ever done before. It should have been a complete disaster.

This, however, wasn’t any old ramshackle single; it was ‘Albatross’.

Of all the million or so bird names the band could have chosen, they settled on ‘Albatross’, for whatever reason, perhaps utterly

unaware of the bird’s bad press with mariners ancient and new. Maybe they just felt invincible, riding the crest of stardom’s wave.

As with most journeys through life, the initial reviews were relatively positive; actually, they couldn’t have been better.

‘Albatross’ scored the band’s first number-one in the UK chart in December 1968. Sadly, the band were in America on tour at the time and couldn’t enjoy the thrill of Christmas at the top of the charts, but as the band’s story unfolds, it’s tempting to speculate how things might have turned out if they’d just called that single ‘Seagull’, instead.

While they were in Chicago, Fleetwood Mac received the highest accolade in blues terms, the chance to record at the legendary Chess Studios. Along for the ride were some top-class blues players, including Buddy Guy, Willie Dixon, Honey Boy Edwards, and Walter ‘Shaky’ Horton, to name but a few. The entire session, including all the out-takes, bum notes, and chat from the band, was released a year later on a double album entitled ‘Blues Jam at Chess’. They also recorded an album in New York without Mick or Jeremy, but using Otis Spann on keyboards and SP Leary on drums, called ‘The Biggest Thing Since Colossus’. This band wasn’t certainly one to underestimate itself.

However, Fleetwood Mac had underestimated the reaction of their die-hard blues fans, who weren’t impressed by number-one hits and wondered just where the band were heading with a tune like ‘Albatross’. If Peter Green was worried, he certainly didn’t show it. He brushed off the fans’ speculation by declaring, ‘I’m going to play what I like when I like.’

Sadly, he and the band would later discover that any attempt to step outside the narrow confines of the blues territory would earn them catcalls and boos at concerts.

This prospect troubled some of the band, but Mick Fleetwood was more stoic, realizing that the single had earned them a much wider audience and had opened the door to real experimentation

with their sound. The follow-up single was a tragic song by Green entitled, ‘Man of the World’, in which he pours out his frustration and disillusionment with the trappings of fame and fortune. Ironically, ‘Man of the World’ was just what Green wasn’t going to be in the future. If anything, ‘Man Off the World’ might have been a more pertinent title, considering the madness that was later to invade his entire persona.

Even more sinister and prophetic was the single’s B side, called ‘Somebody’s Gonna Get Their Head Kicked In Tonight,’ attributed to Earl Vince and The Valiants. Sadly it was Green who was to have his head metaphorically kicked in while on tour in Germany in 1969.

One subtle point about this single, which the more diligent fans will have picked up on, is that it was released on Andrew Loog Oldham’s Immediate Records, rather than on Mike Vernon’s Blue Horizon. There was a cunning reason for this. Clifford Davis had been waiting for the date that Fleetwood Mac’s contract ran out with Blue Horizon, and the moment it did, he quashed their right to take up an option on the band and signed them to Immediate Records. All of this was a slap in the face for Mike Vernon, who had already negotiated a contract on the band’s behalf with CBS worth a quarter of a million. Needless to say, when Fleetwood Mac joined in with the notorious and nefarious Andrew Loog Oldham, they hardly received a penny.

Clifford Davis had also arranged for the band to own their own publishing rights, but only by setting up his own company to do so. He also made sure they got an advance from Immediate’s parent company, Reprise, under Warner Brothers, to record Fleetwood Mac’s next project, which was their third album, ‘Then Play On’.

The recording of this album triggered another line-up change in the band, as Jeremy Spencer bowed out to pursue his veneration of Elmore James. At the same time, Peter Green seemed to

be gradually slipping away from the heart of the band and contributing less and less to the recording process. This left the songwriting demands pretty much up to Danny Kirwan, who shouldered the responsibility well enough.

It’s odd that all this disruption and uncertainty didn’t prompt Fleetwood and McVie to get their heads round this creativity thing and start writing, themselves, but strangely they didn’t, and this has been one of the definitive characteristics of Fleetwood Mac as a band. Because Fleetwood and McVie have been the only consistent members of the band, but not the songwriters, it has been left to all the comers and goers to write the band’s material, and it’s probably this one aspect of the band’s evolution over the years that has most made it interesting to follow. Had we had 25 years of Fleetwood-McVie songs, we may not have enjoyed the diversity of style and the changes of musical direction that the use of itinerant band members has given us.

Meanwhile it was the same old story of another single being released while the public waited for the next Fleetwood Mac album to come along. Green was tasked with putting this one together and he came up with a song title that must rank as the direst eulogy to lethargy, ‘Oh Well’, to which he added the stunning afterthought, ‘Parts One and Two’. Even the rest of the band thought it was abysmal and bet Green some serious cash that it would nosedive, but with that characteristic effortlessness which all geniuses have for hitting the spot without so much as an atom of effort, it made number two in the UK charts and Green’s flabbergasted co-musicians had to pay up.

Just as the band’s fame and wealth were really escalating, the gulf that had opened up between Green and the rest of the band was rapidly widening. In December 1969 the band were voted in the UK music press as the most successful in ’69, outgunning both the Beatles and the Rolling Stones, and Christine McVie, now officially John’s wife, picked up Best Female Vocalist. Despite the accolades, however, all was not well.

Probably no one will ever really know the truth about the disastrous events that led up to Peter Green completely losing it, unless in the future they finally invent a machine that can read back all the brain’s files, including the ones labelled, ‘Top Secret – this file will self destruct in 10 seconds.’ The end result, though, was tragic and undeniable. Like Syd Barratt and Brian Wilson, Green lost his mind and to all intents and purposes disappeared off the face of the planet for the next 20 years.

Stories abound as to the cause of all this, but the thread which keeps recurring in accounts of the period is that while on tour in Germany in late ’69, Green was hustled off after a gig to join a party with the Jet Set Freaks of Munich, from which he never fully returned. The rumour is that he had taken some super strong LSD, a potent hallucinogenic drug, and somewhere on that trip he blew some serious fuses in his head, and was never the same again.

LSD-induced psychosis is not uncommon; it can strike any time, whether it’s the first, the 31st, or the last dose. It’s not clear if Green had already inflicted the neural damage before that fateful trip to Germany, and that his pharmaceutical carnival with the Jet Set Freaks was the simply the straw that broke the camel’s back. No one will ever know except Green himself, and it’s likely that most of the memory from this time has been pretty much overwritten or erased. To be honest, though, it doesn’t really matter what caused it, for the end result was there for all to plainly see. And the first steps of his 20-year expedition into madness were noticeable. Apart from the usual claims to be God, Jesus, or Jimi Hendrix, there was his wish to give all his money away. Even for a generous man, this wish was without logic, and unfortunately it didn’t take long for many unscrupulous friends and hangers-on to realize this and grab their share of his fortune. Saddest of all was that as the ’60s departed and became the ’70s, something of Peter Green, and ultimately, something from Fleetwood Mac itself, was left behind.

The ’70s were ushered in by pall-bearers. Music fans all over the world were mourning the demise of the Beatles, who officially threw in the towel on ever recording or gigging together again. The grave had already claimed Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, and Jim Morrison, and countless others had also fallen by the wayside. The Rolling Stones debacle at the Altamont festival, at which a fan was stabbed to death by the Hell’s Angels security, signalled the death knell for the hippie peace-and-love dream.

Fleetwood Mac also suffered another casualty in the everchanging saga of their line-up, the only difference being this departure marked the end of the era of the band’s blues-oriented music, because the person leaving was Peter Green. Was it the bad acid, or just the coronary-inducing stress of keeping the hits coming and the endless touring? Who knows? It was whilst

on tour in Sweden that Green broke the news, first to manager Clifford Davis and then to the band. Green had had enough and was getting out.

With his customary generosity and consideration, Green honoured all outstanding gigs and there were no ugly arguments with the other band members. He officially left on 31 May 1970, just as one of his final contributions to the Fleetwood Mac catalogue was climbing the charts, ‘Green Manalishi’. This was to be the last chart hit for the band for over five years, and just highlighted what an immense talent Peter Green was and the size of the gap his departure left behind.

Many a lesser band might have agreed to call it a day, but not Fleetwood Mac. The burden of songwriting now fell to Jeremy Spencer and Danny Kirwan. However, Spencer was also exhibiting signs of cracking at the seams, hanging on more and more to his extreme religious beliefs for inner strength, whereas Kirwan was just hitting the bottle in a band where drinking was something of a religion for a time. John McVie was always a willing drinking partner, giving Kirwan plenty of scope for boozy sessions. The next album was dominated by Spencer’s ’50s and early’60s- inspired rockers and Kirwan’s more soulful ballads. Called ‘Kiln House’, it was warmly received by fans and critics alike, but could not be heralded as a great success, as it yielded no hit singles. Although she was still contracted to Blue Horizon, Christine McVie came in as a session musician and provided some of that

classic style which had won her the vocalist of the year award from Melody Maker more than once. She would eventually become a fully-fledged member of the band in the autumn of 1970.

In 1971 the band, now with its fifth line-up, set off on tour again to promote the album and to let the fans know they were still alive after Green’s very public departure. A mere fortnight into the tour, however, disaster struck again. It seemed as if the albatross was still flying over their heads. Jeremy Spencer just disappeared overnight. Initially, it looked as if he had been coerced into joining the American cult, the Children of God, but as more details emerged, it seemed as though he went willingly and had planned such an event for some time. All this took place in Los Angeles, as the band were due to play the Whisky a Go-Go, the venue made famous for being where Jim Morrison and the Doors got their first break.

Just two weeks into the tour manager Clifford Davis was facing financial ruin, but he had a brainwave and called Peter Green. Initially, Green was reluctant to get involved with the band again, but seeing the predicament Davis was in, he joined the band to fill Spencer’s gap until they could get somebody else, in a gesture that demonstrated that he hadn’t taken total leave of his senses. Fleetwood Mac managed to honour all their tour dates and his arrival back in the band provided fans with an unexpected bonus. Green stressed that his inclusion in the band was purely temporary and urged his fellow band members to keep looking for a replacement. Meanwhile, they had moved together into a huge mansion, called Benifold, in Hampshire. There, John and Christine McVie inhabited one wing while Mick Fleetwood and his partner Jenny Boyd lived in another. Danny was in the attic with his girlfriend. This creative communal living in such an opulent setting truly epitomized the rock and roll dream. Into this fantasy world stepped the band’s newest recruit, Bob Welch.

The band hired Welch for more than his songwriting ability and

guitar skills. At this stage Danny and Christine McVie were the principal songwriters, but they needed to expand their sound and looked to Bob to inject the Fleetwood Mac sound with that allimportant X-factor.

So, with the band settled and re-grouped, manager Clifford Davis brought the Rolling Stones’ mobile recording unit down to Benifold and work started on the album ‘Future Games’.

Once the album was complete, true to form, the band packed off to the States to promote it on yet another tour. The gigs were reasonably successful, but filling the chasm left by Green proved an uphill struggle for Welch. Under immense pressure to live up to Green’s standards, a situation made worse by his weaker vocals, it was only a matter of time before cracks started appearing in the band’s set. Unfortunately for Welch, his voice was the first thing to go when the band were on stage.

The band returned to England to work on their seventh album, ‘Bare Trees’. Released in 1972, it was the least well-received of their work. The trouble was that Fleetwood Mac’s sound no longer fitted in with the popular music of the time. By 1972, Britain was in the grip of the legion of platformed, glitter-encrusted bands that made up the glam-rock movement. Arguably, only T.Rex showed any real signs of creativity, while the rest was just fun, cheap, throwaway pop. While younger music fans went ballistic for the sheer entertainment and spectacle of the glam rockers, older music fans, raised on Hendrix, Pink Floyd and the Doors, were simply left to gasp, despair, and wonder what on earth all the fuss was about.

‘Bare Trees’ was mostly a product of the songwriting duo of Danny and Christine McVie, but it was a Bob Welch composition, ‘Sentimental Lady’, that made the first release as a single. The band toured the States with the album, and yet again ended up losing one of their members in transit. The casualty this time was Kirwan. His drinking had worsened to such an extent that he

ended up throwing a wobbly at one gig, refusing to join the band onstage, and instead heckling them from the crowd. What a night that must have been for the other musicians, who promptly sacked him.

It was becoming a cycle – record the album, tour the album, lose a band member, find another, record the next album, and so on. Dave Walker joined as a vocalist next, and then in the autumn of ’72, Bob Weston received a call from Chicago asking him to join the band. He thought it was an elaborate hoax at first but a call from Mick Fleetwood himself finally convinced him.

The new line-up returned to Benifold in Hampshire to solidify themselves and to record some new material before heading off to Scandinavia for a tour specifically aimed at ironing out all the creases between the new members on stage. They could afford to make some errors and try out new material in front of this audience.

The next album was ‘Penguin’, and as soon as it was in the can it was off to the States again to sell it. Even the lives of successful rock stars can seem predictable at times, but this album attracted fairly negative reviews across the board and seemed to be a filler album. Fleetwood Mac had not found their real personality yet. Of the new members, Dave Walker’s contribution was minimal, and it was Bob Weston who seemed to be settling in better.

Eventually, by the summer of 1973, Walker was sacked, and Weston departed months later. Fleetwood Mac were definitely going through a phase of transition, and was yet to find its voice and sound.

Bob stayed long enough to record ‘Mystery to Me’, the next Fleetwood Mac offering, which was again recorded on the Rolling Stones’ mobile unit at Benifold in Hampshire. Unfortunately for a band already at the breaking point, this album received far worse reviews than the previous one, and Fleetwood Mac’s woes were only just beginning. Despite hiking off to America for the

usual tour, it was the McVie’s marriage which would collapse en route this time. Christine had an affair with Martin Birch, the sound producer on the Rolling Stones’ mobile unit, while John was enjoying the delights of a debauched rock lifestyle without the stabilizing influence of his wife. It was a recipe for disaster.

The saga didn’t end there. Bob Weston was sleeping with Jenny Boyd, Mick Fleetwood’s wife and sister to Pattie Boyd, who’d once been married to George Harrison. It was turning into more of a Shakespearean plot than the story of a rock band.

All these traumas would result in the band disintegrating on tour and lead to the completely bizarre scene outlined at the very beginning of this biography, when Clifford Davis had to plonk an entirely fake Fleetwood Mac on stage in a desperate attempt to honour some gigs. The details of this would fill a book itself, but the basic premise was that Davis was convinced the band was finished, so he attempted to build a band around Mick

Fleetwood. He thought he had Fleetwood’s approval in this, but he hadn’t, and eventually Fleetwood left him in the torturous position of trying to convince the world that Fleetwood Mac were on stage on a night where all the band members were nowhere to be found.

The wrangles naturally resulted in the lawyers getting involved until an out-of-court settlement finally put the matter to rest. It was an ugly scene in the band’s history, and it’s a credit to their unbelievable resilience that they ever bounced back from that infamous episode.

The fake American tour of 1974 must go down as the most brazen attempt by a manager to keep the semblance of a band alive. It would mark Davis’s swan song to the industry. After the whole show descended into a legal battle, he stopped all his dealings with the music business and refused ever to manage an act again, a vow to which he has sadly stuck. Though he might have been a bit of an East End London character, he brought some panache and verve to all his dealings with artists, management, and bookers. He also helped Fleetwood Mac realise their ambitions musically without trying to determine their direction with too strong a hand.

A footnote to all this fakery was that apparently a Peter Green clone was doing the rounds of pubs and clubs in Europe and getting away with it. If that wasn’t enough, a guy passing himself off as Jeremy Spencer even managed to bluff his way through a concert with the band until he eventually cracked when faced with Spencer’s parents, who rumbled him immediately. Called Andrew Clarke, this Spencer wannabe had been at it for years, even getting to jam with Rory Gallagher at the Montreux Festival in Switzerland.

These were strange days indeed and summed up the madness of the post-Hippie, pre-Punk era. It was also a difficult time for the great stadium bands that had been so popular in the late ’60s

and early ’70s. They now began to be seen as anachronisms. The days of massive productions somehow seemed out of place, an indulgence too far, particularly in a country then being shaken by strikes and economic uncertainty.

The mid ’70s also witnessed the first wave of disco fever. It was a more of a tsunami, and really took off, with studios all over Britain and America kicking out single after single of up-tempo dancefloor mayhem. Combined with movies popularizing it, the whole disco movement left the folk-rockers looking decidedly jaded, compared with the spangly, mirrorball world of the clubs. Like the glam rock era preceding it, the age of disco was one dominated by the teenybopper market. Keen to tap into this younger, hormonefuelled audience, the music industry suits churned out bands like the Bay City Rollers and The Sweet, who lived at the opposite end of the spectrum from Fleetwood Mac.

Alas, Fleetwood Mac found themselves in legal turmoil yet again, with the old problem of the fake band rearing its head. Part of the litigation was founded on the premise that Clifford Davis, not Fleetwood Mac, owned the name of the group. This raised fears at Warner Brothers, to whom the band were signed at the time, that they might end up in court for putting out an album with the band’s name on it. It was a plot twist too ridiculous even for the most far-fetched soap opera, and it could only have happened to Fleetwood Mac. Not only had a fake band done the rounds, but half of their members had clones running around the world impersonating them, and it had come to the point at which they didn’t even own their name, which was comprised of two of their surnames. The record-buying public was just as lost, and sales during this period were depressingly poor.

Despite everything, Fleetwood Mac released ‘Heroes Are Hard to Find’ in 1974 on the Reprise label under Warner Brothers, and in their own name, before setting off on the usual tour of the USA. Who would get lost on this escapade?

Bob Welch stepped up to the microphone, saying, ‘“Heroes” was the fifth album I’d done with the band. It wasn’t all that wellreceived. It was apparent to me that something had to change.

I didn’t really see myself as a front man any more in the context of Fleetwood Mac. I think the other members of the band were seeing me in a particular light. I wanted to do things they didn’t want from me.’

Which is a rather convoluted way of saying there were insurmountable artistic differences between him and the band and that he wanted to leave. Like Peter Green before him, however, Bob honoured all the gigs the band were contracted to do and didn’t let them down by any stretch of the imagination. He left officially in December 1974, and the band said their farewells from their new residences in Los Angeles. Without Clifford Davis and Benifold at hand, the band had less reason to remain in England. They always seemed to do better with stateside audiences, and the tax breaks were probably better. They certainly couldn’t have been worse than in Britain, where successful artists could find 90% of their earnings going straight into the Exchequer’s coffers.

So, as 1975 rumbled in, Fleetwood Mac were on the prowl for more band members. This time the new recruits would make a difference the world would never forget, eventually releasing two or three of the most outstanding albums the band would ever record, and earning them fame and fortune that utterly eclipsed the Peter Green era.

New Year’s Eve 1974 had found Lindsey Buckingham and Stevie Nicks at their lowest ebb for some time. Then the phone rang and their lives would never be the same again, but that’s rock and roll for you.

Fleetwood met Buckingham and Nicks in Sound City Studios in LA on a random visit that had more to do with a trip to the supermarket than finding new members for his band. That’s the way real magic works. The pair were working on some songs for

a new album, but hadn’t really had any luck with their previous efforts and were on the point of calling it a day, when in walked Mick Fleetwood. He had been brought there by Keith Olsen, who really wanted him to consider the merits of the studio for rent, rather than the errant musicians who happened to be there, but in the process Fleetwood’s ears pricked up when he heard Buckingham play and he knew he’d found the next guitarist for the band.

Unfortunately he wasn’t looking for any other musicians beyond a guitar player. However, when he got in contact with the pair it was obvious they lived, worked, and dreamt as a duo, so it would be both of them or nothing. Fleetwood made one of the best choices for the listening public when he decided to give the pair a break. He was already hoping to change the musical direction of the band, because the previous album had floundered, and here he had found new songwriting blood in the form of Stevie Nicks.

So it was that the tenth line-up of Fleetwood Mac was given birth in a downtown studio in LA. What none of them could guess at the time was that this melting pot of musicians was to provide a dynamic chemistry on stage and in the studio that would propel the band to even greater heights than they had experienced during the Peter Green era.

Mick Fleetwood would comment later on this. ‘The first time we played together,’ he recalled, ‘was in the basement of our agent’s office, and it was at that point the real, true excitement came. It was very apparent that something was really happening. It was very much like when the band first started.’

Christine McVie was slightly more reticent about having another woman in the band. Not that she was possessive or bitchy in any way, but she knew that one female amongst a band of rock and roll boys was complex enough, especially considering the band’s track record of incestuous relationships and general shenanigans. She summed up the situation quite succinctly, saying, ‘Mick and John

said to me, “If you don’t like the girl, then we can’t have either of them, because they are a duo.” The last thing I was thinking about at the time was to have another girl in the band. I had been so used to being the only girl.’ However, her concerns were soon assuaged. ‘We met them both.’ she recalled. ‘We all really got on well together. Stevie was a bright, very humorous, very direct, tough little thing. I liked her instantly, and Lindsey too.’

Mick Fleetwood still had his work cut out convincing Warner Brothers that this new incarnation of the band was the best thing yet, and that the next album was going to prove to the suits and to the fans that Fleetwood Mac were back. With hindsight, it’s easy to wonder what all the fuss was about, knowing as we do that the band were on the verge of a major breakthrough, but in the mid’70s, Fleetwood Mac were still just a rocking, folky, blues band that had by all intents and purposes passed their sell-by date and were trying to make headway in a music market that had already

written off their particular genre of music as old, faded, worn-out, and highly unlikely to appeal to the kids.

Up to this point, Fleetwood Mac’s major impact had actually been in the States, leaving Britain and Europe rather nonplussed about the whole deal. They’d had this bizarre see-saw effect with their record sales on either side of the Atlantic, where albums and singles that did well in the States hardly scored in England, and the one or two that sank without a trace on the US hit parade invariably did better at home. It must have been difficult to know where and to whom they wanted to target their next offering.

One thing was certain, though; they weren’t going to waste any time debating the issues, so less than a month after the group first got together they headed back to Sound City Studios in LA to begin work on the album they would simply call ‘Fleetwood Mac’.

I think all the hassles over the name and all the doubts as to whether Fleetwood Mac could rise, phoenix-like, from the ashes of so many line-up changes encouraged them to state their name boldly as a gesture of solidarity. It perhaps also served to convince anybody who had any doubts, after the court case with Clifford Davis, over who owned the name. It was definitely Fleetwood Mac.

The desire to get cracking in the studio and come up with an album meant the band didn’t really have a lot of time to get to know the new members, so the album was created by the bringing together of the individual units rather than the individuals all having gelled into one unit. Thus, Buckingham and Nicks added in their back catalogue of songs which made up virtually half of the material, while Christine McVie and the rhythm section covered the remainder of the tracks, except for one cover song of the Curtis Brothers’ number, ‘Blue Letter’.

One song which served to prove Stevie Nicks had been a good addition to the band was the beautiful ‘Rhiannon’, a wonderfully crafted ballad about a Welsh witch, that was to become one of

the band’s most popular songs with the fans and always requested at gigs. Christine’s ‘Sugar Daddy’ also became one of the band’s staples, while ‘Over My Head’ and ‘Say You Love Me’ showed that she had by no means lost her talent for writing top-class lyrics and melodies.

The album ‘Fleetwood Mac’ was released in July 1975 and didn’t take long to reach the prestigious number-one slot in the American album charts. Christine summed up their appeal simply enough. ‘I think we were just a product that everybody wanted at the time,’ she said. ‘It was a very versatile album, and on stage the band projected a kind of exciting image, a new sort of image which hadn’t been seen before. It was unique to have two women in a band who where not just back-up singers, or singers period… The five characters on stage became five characters, as opposed to just five members of the band.’

Personally, I think the band’s success at that time had a lot to do with what was happening with their audience. By the mid-’70s, the music-listening public from the ’60s had grown up. They were no longer a bunch of reprobate teenagers, all taking their clothes off for the first time and running around the festival fields while singing hymns to peace ‘n’ love, man. They had seen what war, and in particular Vietnam, had done to a lot of young people. They had witnessed the race riots and the protest marches. They had matured, and by that time wanted a kind of music and lyric that reflected that older viewpoint. The appeal of 20-minute lead guitar and drum solos was beginning to wane; they were looking for something a bit deeper and more melodic.

This extrinsic element to the music scene is what keeps the X-factor in business. No matter how amazing the songs, or how well they’re produced, it comes down to public opinion in the end as to what sells, what doesn’t sell, and, most importantly, what goes platinum. Sometimes the oddest and most uncommercial albums can cut right through all the baloney of the music industry, and by

sheer public demand create a monster hit. At other times an artist can turn out an album that is at least as good as its predecessor, only to find the listening audience has moved on and doesn’t want that kind of sound any more. Punk rock, which was about to be born, provides a perfect example of this, when virtually overnight, courtesy of the Sex Pistols, a whole genre of ballad-writing, folky, bluesy artists found themselves to be classed miserably as last week’s news.

The key aspect to Fleetwood Mac’s appeal was that their songs had an intelligence, a maturity of content, and style that reflected the mores and the lifestyle of their audience. This is why, when all the hype had died down and the record executives had retired to their beds, the album continued to get airplay on a diverse range of stations in America, therefore managing to stay in the Top 10 for well over a year.

Meanwhile, back in Blighty, it was the same see-saw sales conundrum, with the band struggling to make headway in either the singles or album charts. It must have been a depressing situation for the Brits in the band, but Mick Fleetwood was characteristically forthright in his summation of it all. ‘We were primarily interested in getting out of England altogether,’ he said. ‘The band wasn’t working in England. At that point we were playing more and more over here, the States. Also, I thought England was very grey and full of depressed people. We just got out.’

The huge sales of the album went way beyond the band’s expectations. They had always sold comfortable amounts, but had never really ascended to platinum status. ‘We’ve always kept a low profile,’ John McVie explained, ‘away from hype. That’s the way we are. We never wanted to be viewed or reported as the biggest thing since sliced bread. Me, Chris, and Mick have been working together for a long time. We’ve eaten every day and always had money for smokes. I’m proud we pushed ahead. The success now makes some justification for the efforts of the past.’

Following on from the band’s album success, Warner Brothers decided to go ahead and release one of its songs as a single.

Christine’s ‘Over My Head’ was put out and made an immediate impact, which further broadened the band’s fan base in America. This was their first chart-topper in the singles market since Peter Green’s offerings in the late ’60s. This says a lot about how the way record labels used to look after their artists, compared to now. Today, if an act doesn’t have a steady stream of chart-topping singles, or at least a huge blockbuster album, it’s likely to find its contract has expired and won’t be renewed. Back in the ’60s and ’70s, the music industry took a longer-term view and nurtured its talent.

Naturally, having produced such a fine album, it came to be time again to take it out on the road. You’re beginning to see a pattern emerging now of how all this music business works: get a new line-up of musos together, record the album, release the single, go on tour, go crazy, lose a band member or two, get a new line-up, record the album, and so on. Easy, really?

Most surprisingly of all, this time Fleetwood Mac managed a tour, through the autumn of 1975, without any casualties. Buckingham and Nicks were keen to prove their worth, so they didn’t mind roughing it from time to time with all the rigours of being on the road. Meanwhile, the old hands were intent on showing them just what a professional outfit they were. The result was a stupendous tour with a fresh sound and image for the band. This irresistible combination went down a storm with the existing fans and won the band even more new followers.

The tired and worn-out blues numbers were abandoned to the back catalogue while the bright, tight, West Coast production and delivery of rock and pop ballads had the fans filling the aisles. Any doubts the long-term blues devotees had of the band were instantly dispelled upon seeing the exciting stage show, which included not one, but two pretty women – always a real bonus with the

rock and roll gentlemen of yore. The thumping drums and bass of Fleetwood and John McVie just wouldn’t let your feet stay still; in between these thumps was the clean, proficient guitar work of Lindsey Buckingham cranking out some awesome riffs.

The band had a short break in Hawaii to brush the studio dust off their shoulders before returning to the States to prepare themselves for – yes, you guessed it – another tour to promote the album.

This first tour of the band with the definitive tenth line-up probably found them at their happiest and most dynamic for many years, but how long would it last before hairline fissures started appearing in the band’s make-up? Buckingham was already feeling the strain that playing somebody else’s guitar licks has on a musician. Being a decidedly independent man and wanting to retain his personal style made it hard for him to dovetail sweetly into playing Bob Welch songs without a second thought, but he persevered, probably because Nicks was apparently enjoying the trip and felt more at home in the group than he did.

They started on 9 September, 1975 and didn’t return to LA until 22 December, gigging virtually every night and working hard to sell the new album, the new band, and the new look. It was hardly as lavish an affair as later tours would be, with the band still relatively roughing it; they hadn’t yet reached the stretchedlimo-for-every-member kind of indulgence that would inevitably accompany their increasing success.

The tour was naturally a chance for the band really to get to know one another and to establish their core identity. It had the effect of smoothing out any glitches in their performances and creating that natural rapport which is so important between band members on stage. Having made that happen, though, could it sustain itself under the pressure that comes from the business side of the music industry?

Well, there’s nothing like good record sales to take some of that pressure away, and, with that in mind, Warner’s released ‘Rhiannon’ in early 1976. It was an instant hit for the band and did much to vindicate Stevie Nicks’s place in the band and to settle any doubts Christine McVie may have initially had about another woman being part of the crew. After ‘Rhiannon’, Christine’s ‘Say You Love Me’ was released to similar plaudits. Sadly this was only true of their sales in America. Up to that point in the mid-’70s, the band were finding it hard to get anywhere in the British charts. For example, when ‘Rhiannon’ was put out as a single in Britain it struggled lamentably to make the Top 100, let alone the Top 20; Its highest recorded place was a miserable 46.

The difficulty the band experienced in Britain was more than likely due in some small measure to the loyalty showed by the fans to Peter Green’s version of the band, which was a blues and rock outfit rather than rock and pop. I’d hate to infer that the Americans are anything less than honest in their appreciation of music, so perhaps it’s better to say the Brits have a bit more integrity in where they hang their loyalties, and, once given, are slower to change. Back in ’75 and ’76, the music industry in Britain was turning out the last of the glitter bands before the murderous advent of punk came along to kill any musical speculation whatsoever.

The listening public, of which I was one, were somewhat lost, to put it mildly. Having been raised on the Beatles and the Stones, having taken the seminal trips as we grew with bands like the Pink Floyd, Frank Zappa, or Bob Dylan, we were now expected to lap up the Bay City Rollers and Donny Osmond. It was a tough time. Admittedly these bands were the teeny-bop chart makers, but we still had to listen to this pap regularly on the radio, and, worse still, watch it on the telly. Many musical aficionados were seen edging their way into the midnight sea at high tide, clutching their

Hendrix and Doors albums, with their heads suicidally pressed to their chests, never to look up again.

Okay, so that’s a bit extreme, but for people with an ounce of musical taste, the British charts in the mid-’70s made tough listening. Punk could only possibly have followed this, because what went before was so paper-thin and soulless. At least Sid Vicious looked like he meant it. Into this mass culture, then, Fleetwood Mac were trying to sell what was seen as outdated arena pop-rock.

The kind of people who were British blues music fans, and who had taken on board Peter Green’s immense talent, were not going to fall for what was seen as a less noble substitute. Whereas in the States, musical appreciation was a much more fluid thing and didn’t really have a countrywide basis. One thing could be kicking off in New York while an entirely different scene was breaking through on the West Coast. All of this meant the American audience was more open to what Fleetwood Mac were trying to achieve.

It sounds odd by today’s standards, but to have two women providing the creativity and, more importantly, fulfilling the job of a front man was something of a novel concept in ’75-’76. Most rock bands are utterly devoted to the concept of having a male rock god out there fronting the group. Women performers were for the most part either successful solo singers or banished to the harmony department. For such macho figures as Mick Fleetwood and John McVie to relinquish this age-old status was revolutionary, and something of a revelation in the ’70s.

More to the point, the approach proved highly successful. Christine McVie was not an unattractive woman, but Stephanie Nicks, as she was first named, was sexy and feisty. She was the foxy lady personified, and exuded that kind of passionate, fiery aura that Mick Jagger achieved with his lips and hips. Putting these two women together on stage gave the male audience something to

look at – and lust after. American audiences were also more likely to accept a good image even if the product wasn’t 100% ready, whereas the British fans wouldn’t be fooled, no matter how much glitter you sprinkled over it.

Stevie Nicks must have felt like she was living in a fairy tale, going from rags to riches in less than a year. The one-time waitress and cleaner was propelled to the dizzy heights of rock’s royalty quicker than you can say ‘millionaire’. Many people might have lost themselves in such a rapid transition from anonymity to stardom. It says volumes about her character, and perhaps about how solid she was in her hippie ideals, that Stevie didn’t let it all go to her head.

s 1976 unfolded it became clear that the band’s success had clearly divided Stevie and Lindsey, while John and Christine were as usual living in separated dis-harmony; Mick, who was supposed to be the solid, father-type figure of the band, was pressed to the point of splitting with his wife and divorcing her – before he remarried her again, and then divorced her again. It probably would have been worthwhile for them to have had a marriage guidance counsellor on the permanent payroll of Fleetwood Mac back then. He or she would have certainly had plenty of serious work to do.

Despite all this emotional turmoil going on behind the scenes, all them seemed to have a loyalty to their marriage with the band that kept them going. Somehow, they never let personal problems supersede the demands of the group. No matter what, Fleetwood Mac and the fans came first and foremost in all their lives, and the

band members were intelligent enough to realise they’d never get such a great chance to make it big again.

Amidst the soap opera, Warner Brothers were on their case looking for another album and the next string of hits. Rather than succumbing to the emotional divides in the band, the songwriters went off and put it all down in material that would make the next album. That this album would be the greatest breakthrough for the group and one of its all-time best sellers says something about the nature of the creative process and its relationship to trauma.

It was Eric Clapton who admitted that there was nothing worse than being happily ensconced in a relationship to dry up all his creative juices. He went as far as purposely wrecking any stable relationship with his partner just so he could come up with a bit of angst and few good tunes for his next album. This was one problem from which Fleetwood Mac never suffered, for there was no shortage of stress and arguments between the couples in the band. Click

Such troubled waters led them to produce some of their lifetimes’ best work in the shape of ‘Rumours’. The comings and goings of each band member had certainly given the West Coast press more than enough to chew on, and it was this capitalising on seedy, showbiz rumours that actually prompted the band to call the album ‘Rumours’. We certainly can’t berate them for not having a sense of humour – or was that just a healthy sense of irony?

Christine McVie would later admit, ‘The outcome of the various separations and emotional upheavals in the band that caused so many rumours are in the songs. We weren’t aware of it at the time, but when we listened to the songs together, we realised they were telling little stories. We were looking for a good name for the album that would encompass all that, and the feeling that the band had given up, the most active rumour flying about. And I believe it was John, one day, who said we should call it “Rumours”.’

This time the band all withdrew to the Record Plant studio in Sausalito, California with producer Richard Dashut to record the songs that were coming out of this difficult period. However, it turned out to be so stressful that eventually Fleetwood Mac went out on the road just to relieve the tension that being cooped up in a studio brings to any band. This did give them an opportunity to test out any of the new songs they had been working on and provided a good level of feedback, so that when they returned to recording again they had some idea of what was working for the fans and what wasn’t going down so well.

Instead of carrying on at the Record Plant studio, they shifted back to LA, and eventually would record the album in no less than four different studios as it progressed. The services of Keith Olsen had been discarded, not through any major problems with him, but because the band wanted to take greater control of what was happening at the mixing desk. They now exhibited the kind of

confidence in themselves that favourable record sales encouraged, and were prepared, at the risk of disappearing up their own proverbial backsides, to stamp their character firmly on this album called ‘Rumours’.

Taking this desire to have greater control over all the aspects of producing the albums and touring the band, Mick Fleetwood and John McVie set up their own managerial company, rather amusingly called Seedy Management. It was obvious that despite any niggles in the band they certainly hadn’t lost their sense of humour.

The bulk of the responsibility for this enterprise fell on Mick’s shoulders, ‘We’re much less insulated,’ he said, explaining their ethos, ‘because I make sure everybody knows what’s going on. An outside manager has a tendency to try to make it look as though everything is going smoothly even when it’s not. I think we’ve got complete peace of mind. I think, for instance, that if someone from outside had been handling this band we would have probably broken up when there were problems. This band is like a highly tuned operation, and wouldn’t respond to some blunt instrument coming in. There’s a trust between all of us that would make that a problem.’

John McVie was particularly proud of their efforts and was keen to point out that, ‘The hardest thing for people in the business to accept is the fact that the band achieved all that it has without professional help. Some people still think that Mick’s just a dumb drummer and I’m a dumb bass player.’

Most of the work the band had done in the studio in the past had been recorded mostly live, with the necessary overdubs going on later, but with ‘Rumours’ the band didn’t work as such a cohesive whole, preferring instead to build up the songs layer by layer. They still, however, did everything they could to retain some verve and vibe in the process. ‘The way we approach it,’ Lindsey added, ‘is more like the way the Beatles used to approach their

thing in the studio; having a general idea and then going into the studio and letting the spontaneity happen. There was nothing specifically worked out when we went into the studio. We didn’t have demo tapes like the last time. The whole thing just happened. That’s where you capture the magic.’

Of course, such luxury in the recording process is only accorded to extremely successful bands, and even though Fleetwood Mac could warrant these expenses, the moguls at Warner Brothers were getting jumpy at the huge costs involved. This was usually where the band’s manager would take the brunt of the flak, so unfortunately it fell to Mick Fleetwood to go to Warner’s and assure them that a product was on its way and would be worth the wait. He didn’t even allow them to hear any of the rough mixes, preferring instead to let them sweat a bit. Had they known what was going down in all these several studios and with all these diverse songwriters, they may have been less worried, but Fleetwood was never one for having massive sympathy with the business side of the music industry, and I think he enjoyed having them over a barrel for once.

Meanwhile Christine had been having a few doubts and the odd downright moment of panic because she was finding it hard to come up with any new material. It seemed as if for once her muse had deserted her. Then one day, ‘In Sausilito,’ as she later recalled, ‘I just sat down and wrote in the studio, and the four or four and a half songs of mine on the album are a result of that.’ This was an incredible statement; just as well she wasn’t having her hair done that day, or the world might only have had half of the masterpiece that was to become ‘Rumours’.

Lindsey was also having a few doubts about the whole situation, feeling that his songs weren’t coming out how he wanted them to sound once the band got a hold of them. However, faced with Mick’s take-it-or-leave-it attitude, he settled down a bit and agreed to take it for the betterment of the whole enterprise.

Meanwhile, Nicks summed up her way of writing songs by saying, ‘All my songs are personal. They are all about things which did happen. The only way I can be is honest. I can’t make up a song. I can’t make up a story. I promised myself from when I was 16 years old and wrote my first song about the break-up from my boyfriend Steve that I would never lie in my songs. I would not say, “I broke up with him”, if the truth was he broke up with me. I would stay clearly truthful to the people.’ This may or may not have been a good philosophy to have, depending on where a person stood in the lifeline of Stevie Nicks.

With her relationship to Lindsey still hanging precariously in the balance, we can bet that most of her love songs on ‘Rumours’ concern their past, particularly ‘Dreams’. In a reflection of this from the other side of the mirror, Lindsey’s ‘Go Your Own Way’ was a subtle slap with a sledge hammer on how he felt about the whole thing.

Ironically when the Warner’s men in black suits finally demanded to hear something, that was the track that Fleetwood offered up. Six and a half minutes later there was a stunned silence from the suits, and they never bothered to hassle the band again. On the strength of that one listening they knew the band were onto something really special.

All in all, it took 14 months to complete the recording of ‘Rumours’, plus a further five months just mixing it. Warner Brothers were eventually able to release it in February 1977. ‘Go Your Own Way’ had been released as a single just before Christmas ’76, first as a taster of the forthcoming album for the fans, and also to mop the fevered brows of the men in suits. It’s also likely that the band wanted to remind them not to forget their Christmas bonus. The single nudged its way swiftly into the Top 10 and was a portent of the gold dust yet to come when the album struck the streets – and boy, never mind the gold dust, Fleetwood Mac could have paved the streets with gold blocks from the awesome sales this album would net them.

Within a year, Fleetwood Mac had managed the amazing feat of having sold nearly 10 million copies of ‘Rumours’, with the album sitting pretty at the number-one slot for over six months. At the height of the fans’ feeding frenzy, up to a quarter of a million copies were being sold every week. It is difficult to imagine such impressive sales figures, but any band that sells 100,000 copies of an album in total are usually moderately satisfied with that as a result. Considering that some of Fleetwood Mac’s earlier albums in Britain were only shifting a maximum of 10,000 copies, it’s easy to see what a real achievement ‘Rumours’ really was.

It must have been an incredible time for the band, with each of them rushing out to buy houses – well, mansions – and fleets of top-of-the-range sports cars, or vintage cars, which was Fleetwood’s particular weakness. Christine summed up the wealth issue and how it had affected the band by saying, ‘It’s enabled all

of us to realise a few dreams that we never thought would happen, but I haven’t egoed out. I’m pretty much of a recluse, as it happens. What has this done, though? Well, the doors have just opened. Now I have the money to get my studio sculpture together, and the whole way of looking at my life has expanded over the last six months.’

Naturally, the music industry were keen to heap awards on this fine achievement; among them were best album of the year 1977, best single, best band, and artist of the year. Perhaps the only downside to all this phenomenal success was the old conundrum –how on earth do we follow that?

Although it probably seemed superfluous to requirements, the band gathered their old gigging heads together and prepared for another tour to promote ‘Rumours’. This goes to show how dedicated the musicians were to their fans. With albums flying off the shelves faster than they could be replenished and records being broken right, left, and centre, many less-committed bands might have just rested on their laurels and left the promotion to the executives and sales teams.

Not Mick Fleetwood and his crew. Despite the reservations of Lindsey, who was never mad for the live tours, and Stevie, who always seemed to be suffering from some throat bug or virus, they prepared for what must have been a tumultuous reception from their fans at every concert. With much greater financial security, the band were able to do it in style this time. No more sleeping on the speaker cabinets for Christine. No more dirty scrubby vans with no seats in the back careering down endless miles of motorway madness. No more greasy-spoon cafes. This was the high life now, and like many musicians before them they took to all this luxury like ducks to water.

Of course there were always a few problems to surmount; one being Nicks’s medical weaknesses, which meant several of the early gigs being postponed. Buckingham’s wisdom teeth were

giving him hassle, so he had to have them removed, but once these problems had been sorted, the band hit the road for six months’ solid touring, attracting rave reviews wherever they went.

The band would usually play an hour-and-a-half-long set, with Nicks prancing around like a bewitched angel in satins and silks, while Buckingham looked the suave debonair rock and roll gent in his crushed velvet loons and swanky jackets. Christine was just as attractive and alluring as Stevie, but in an entirely different way. Audiences could imagine her being the one in control of any relationship and having that more mature edge to her, while Nicks was the perpetually flighty teenage spirit that they wanted to wrap up in their arms and protect.

Meanwhile, back at the ranch, the swarthy Fleetwood beat hell and heaven out of the drums, appearing at one point in the gig with a load of electronic pads all linked up to his body, which he hammered and battered with demonic force, filling the auditorium with a sound and spectacle second perhaps only to Keith Moon in its electrifying energy. He also used an African talking drum to great effect, striking up a rhythmic conversation with the audience.

The bass player in any band is usually the more reserved of the bunch and John McVie was no exception. He wasn’t one for extravagant displays of musical epiphanies. He just played some of the most pumping and memorable bass licks to ever come out of the ’70s. How many times have we heard those same riffs backing up some commercial or TV programme? He really knew how to play his instrument for maximum effect and there was no need to stage dive into the mosh pit just to prove it.

Of course, back stage there were still emotional ripples from the relationship fallouts of the individual band members, but every one of them knew and accepted that the momentous success of the band was more important than their petty squabbles, and so it was a case of let’s-get-on-with-the-job-in-hand-and-for-God’s-sakelet’s-not-screw-it-up-for-everybody. In this band, as in many, the

total sum of the group added up to far more than all its individual musicians.

Nicks summed up the precarious nature of relationships in regard to any fairly successful band that had commitments to go on the road and work hard in the studio, ‘How can you have a relationship with somebody who is in a band, and yet how can you have a relationship with somebody who isn’t? How many doctors or lawyers are going to look at you and say, “Sure Stevie, I’ll see you in three months; I’ll read about you in the papers every day.” Then, when you come home on vacation, you’re doing an album which means you’ll be in the studio all day and half the night, until four in the morning, when you roll in and say, “I’m so tired.” Then, when you finish the album, you get a call saying you’ve got two weeks off. Then you’re going on the road to promote the album!’

She wasn’t far wrong in her appraisal of the situation in regard to her own life, and really hit the nail on the head as to why so many showbiz relationships fall by the motorway roadside as the tour bus rolls and rocks and rolls on.

Indeed, within the next couple of years, all the Fleetwood Mac members would have changed their partners for better or for worse. It’s a sad side-effect of success that the more people have of it in the public gaze the more likely it is to ruin their private lives. It takes a strong character to resist all the temptations that the fans and the road have to offer without completely losing sight of what’s important in personal affairs of the heart.

In a bizarre reversal of what normally happens when bands try to break both the American and the British music markets, it was now down to Fleetwood Mac to replicate the gains they had made in the States with a similar level of sales in Europe, and in particular England, where three of the five current members hailed from. Most British-based bands achieve a degree of fame in Britain and then try to crack the American market. For Fleetwood Mac it had become a case of could they do this the other way round?

In the spring of 1977, the group returned to the UK to try and achieve this aim. They already had some impressive sales figures with ‘Rumours’ to back them up, and nobody in the British press corps could be left in any doubt that they were determined this time to make a creditable impression on British fans.

The concern that Fleetwood and John McVie had was that they would be dogged by the legend of Peter Green and that most of their audience this side of the pond saw them as a blues-oriented band. Fleetwood reflected on this at one of their early press conferences, saying, ‘We are all worried about being labelled as the blues band gone wrong… We’ve been in a whole different world over in the States. Perhaps people will say, “What about Peter Green, then?” We hope not.’

Luckily, they needn’t have worried themselves too much because the first Fleetwood Mac concert was a positive breakthrough. It seemed as if the fans appreciated that the band had kept some of the original Peter Green material in the set and had liberally interspersed this with the new songs.