Well-Being Whole-Person Healing P.36 Sustainability Campus Canopy P.12 Discover Food as Medicine P.26

HEALTH EDITION SPRING 2024

THE

mark diorio

Want bugs with that? Chef Joseph Yoon (left), the selfproclaimed edible insect ambassador and founder of Brooklyn Bugs, visited Colgate in November. Yoon prepped entomological delicacies like guacamole dusted with crispy, crushed black ants as well as brownies flavored with mealworm powder. He also gave a presentation at an ENST Brown Bag Lunch where he discussed the potential of not only edible insects, but also the burgeoning industry of insect agriculture to create resilient solutions for our global food systems.

— Jasmine Kellogg

Read this issue and all previous issues at colgate.edu/magazine. look

Spring 2024 Colgate Magazine 1

Whole-Person Healing Anti-inflammatory diets, acupuncture, Reiki, and more: Learn about complementary medicine from alumni practitioners.

Contents

2 Colgate Magazine Spring 2024 Cover: Illustration by Dan Page President’s Message 4 Editor’s Letter 5 letters 6 Voices Chasing Fire Hotshot crew member Caio Driver ’20 writes about unprecedented fire behavior becoming commonplace in this changing environment. 8

Call Andrea Schaffer ’01 buys herself a lifesaving birthday present. 11 Scene Colgate News 12 Discover Food as Medicine For those who require specialized diets, Sharon Coyle ’86 Weston researches blenderized formulas. 26 Searching for a Cure Ross Fredenburg ’93 is leading efforts to tackle a rare disease. 27

Vital Nature of Exploration and Discovery In Singapore, Gretchen Coffman ’91 empowers students and communities to restore wildlife habitats. 28 Genetic Code-ing Computer scientist Soo Bin Kwon ’16 uses algorithms to fight infectious diseases. 29

SPRING 2024

A Close

The

mental

44

Weaving Stronger Safety Nets To improve

health care, these alumni are strengthening support systems for vulnerable populations.

30

A Picture of Health Have you ever wondered what it’s like to perform open-heart surgery? Medical professionals from various specialties describe their work.

36

JoAnn Inserra ’82 Duncan

Endeavor

The Psychology of Kids’ TV

Ditch the Clutter

Making Waves

Vice President for University Communications

Daniel DeVries

Director of University Publications

Aleta Mayne

Assistant Editor

Rebecca Docter

Associate Vice President for University Communications

Mark Walden

Senior Art Director

Karen Luciani

University Photographer

Mark DiOrio

Communications Specialist

Kathy Jipson

Contributors: Omar Ricardo Aquije, athletics communications manager; Kelli Ariel, web manager; Mary Donofrio, advancement communications dir.; Jordan Doroshenko, dir., athletic communications; Bernie Freytag, art dir.; Garrett Mutz, sr. designer; Brian Ness, sr. multimedia producer; Kristin Putman, sr. social media strategist; Amber Springer, web content specialist

physical or mental disability, age, marital status, sexual orientation, veteran or military status, predisposing genetic characteristics, domestic violence victim status, or any other protected category under applicable local, state, or federal law. For inquiries regarding the University’s non-discrimination policies, contact Renee Madison,

Spring 2024 Colgate Magazine 3

Printed and mailed from Lane Press in South Burlington, Vt. Colgate Magazine Volume LIII Number 3 Colgate Magazine is a quarterly publication of Colgate University. Online: colgate.edu/magazine Email: magazine@colgate.edu Telephone: 315-228-7407 Change of Address: Alumni Records Assistant, Colgate University, 13 Oak Drive, Hamilton, NY 13346-1398 Email: alumnirecords@colgate.edu Telephone: 315-228-7453 Opinions expressed are not necessarily shared by the University, the publishers, or the editors. Colgate University does not discriminate in its programs and activities because of race,

sex,

religion, creed, national origin, ancestry,

status,

Title IX coordinator and vice president for equity and inclusion, 13 Oak Drive, Hamilton, NY 13346; 315-228-7014.

color,

pregnancy,

citizenship

new Netflix show

first deserves a second chance.” 48

A

by Alexandra Cassel ’11 Schwartz tells viewers “every

Becker ’01 Denney is giving clients a stress-free living experience. 49

Jen

Kern ’94 has launched the first all-electric chartered sailing service in the Hawaiian Islands. 50 Bring Her Kitchen Into Your Kitchen Through The Optimal Kitchen, Heather Kroll ’93 Bailey makes healthier eating easier. 51 Salmagundi Read about the University’s first infirmary — built just before the Spanish flu hit campus — as well as the beginnings of Community Memorial Hospital. 96 Alumni News 52 It’s not just what you eat, it’s how you eat it. Evey Schweig ’82 p. 39 Dr. Gonzalo Bearman ’93, p. 79 OT Tang ’17, p. 92

Nick

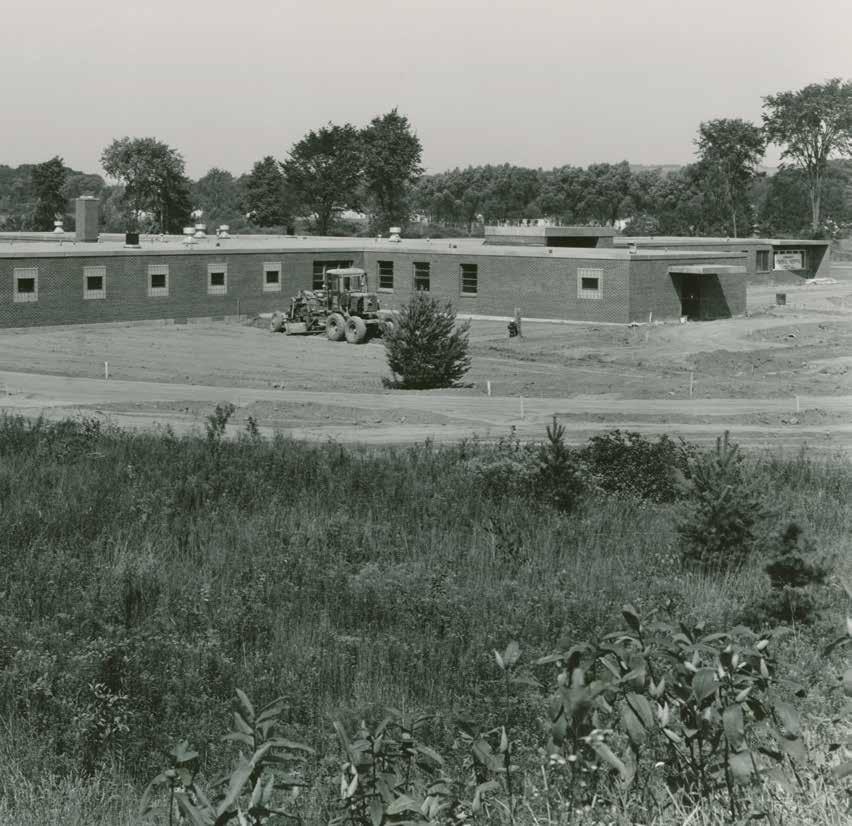

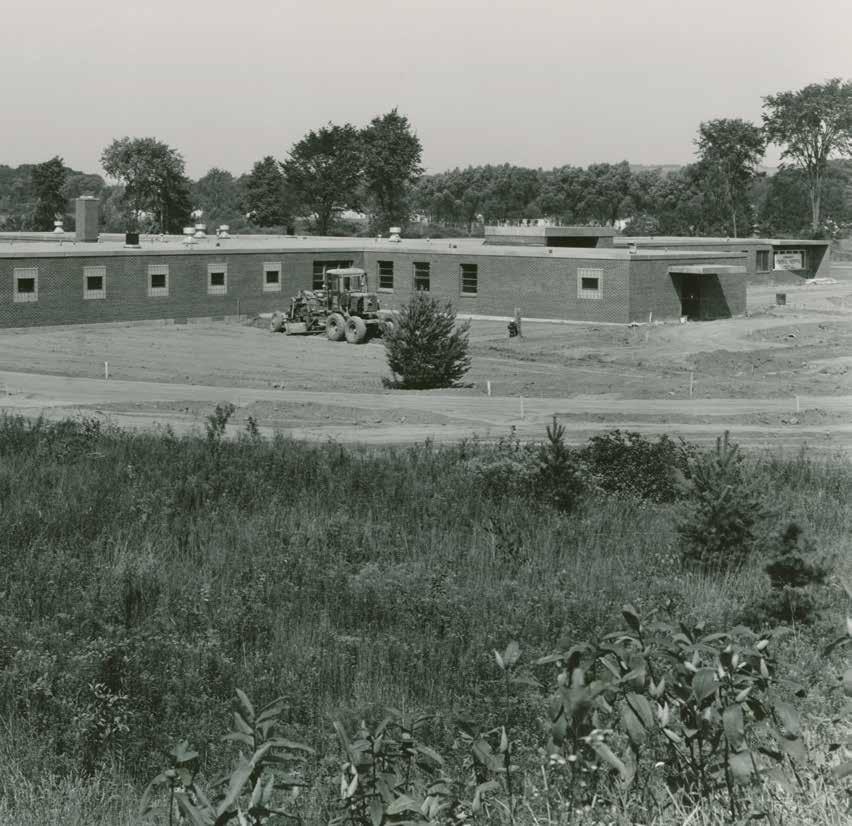

Building Colgate

Every now and then, in a college or university’s history, you can actually see significant changes. This is one of those times at Colgate. It’s a rare moment at any college and university when the physical campus clearly enters a new chapter.

But, both by plan, and also due to some serendipity, the physical expression of Colgate’s third century is becoming more apparent on the campus.

The 19th century at Colgate is most visible in the line of buildings from Alumni Hall to East Hall. The 20th century has two visible chapters. First is the completion of the quads up on the hill with the construction of the chapel and the major academic buildings to the west, as well as the completion of the residential quad. The second half of the 20th century can be seen in the rise of the modern buildings, from Reid to Dana to the original Case Library. Student life at Colgate has changed in fits and starts with the residence halls up on the hill developing first, and Broad Street developing and changing over many decades. The addition of several hundred beds in apartments and townhouses started in the 1970s and continued into the early 21st century.

Right now on the campus, the Robert H.N. Ho Mind, Brain, and Behavior Center (and the related renovation of Colgate’s

1827 West Hall, 1834 East Hall, 1862 Alumni Hall

1900

1906 Lathrop Hall, 1918 Memorial Chapel, 1926 Lawrence Hall, 1930 McGregory Hall

1959 Reid Athletic Center, 1959 Case Library, 1965 Dana Arts Center

2000

1966 113 Broad, 1995 Curtis and Drake halls

2005 The Townhouses

2019 Pinchin and Burke halls

2024

What is this period now? I think of it as a period in which Colgate embraces its national role and recognizes that it has a campus that includes not simply the upper quadrangles but also a large region along Broad Street.

2024 Olin Hall renovation

2024 Bernstein Hall

2025 Peter’s Glen

2026 18–22 Utica St.

largest academic building, Olin Hall) is nearing completion. Down the hill, the new building to house our Department of Computer Science as well as numerous arts departments and programs is fully formed next to Whitnall Field. Slated for completion this summer, faculty, staff, and students will utilize the building in the fall semester for classes and creative endeavors facilitated by the building’s fabrication labs, a robotics lab, a digital recording studio, five computer labs, an experimental exhibition and performance space, a media archaeology lab, and flexible classrooms. (For more, see p. 24.)

Clearing for the glen that will connect what are now two distinct “academic neighborhoods” has begun, and Peter’s Glen will soon be a several-acre green zone for Colgate. A new mixed-use apartment building downtown in the village has begun. In the months ahead, we will begin the Lower Campus Initiative, which will see Colgate renovate the existing structures on Broad Street while adding new beds in a new row of structures in a line to the west of the existing buildings. We hope soon to announce plans for a full renewal of our athletics facilities and athletics campus.

I’m an historian by training, and it is tempting to name periods, to define them by a title. The 19th-century building program was surely The Period of the College on the Hill. With the emergence of McGregory, Lawrence, and Lathrop halls, we can see The Academic Program Emerges. The last period of significant growth — when in post–World War II Colgate we see the new Case Library, Reid Athletic Center, Dana Arts Center, and Olin Hall — is Colgate and the American Century, when a booming national economy is reflected in a booming campus.

What is this period now? I think of it as a period in which Colgate embraces its national role and recognizes that it has a campus that includes not simply the upper quadrangles but also a large region along Broad Street.

Colgate is truly a national, exceptional university of quite significant reach and reputation. Its emerging campus expresses that in stone. We are, in short, in an exciting time.

— Brian W. Casey

4 Colgate Magazine Spring 2024

President’s Message

A Season of Change

Welcome to the health-themed edition of Colgate Magazine

You’re hopefully celebrating spring — a season of renewal — with the mental boost that accompanies better weather. Perhaps you’re evaluating your physical wellness, assessing your living space, or enjoying the dopamine rush of planning a summer vacation.

With this special issue, it’s our intention to provide compelling pieces that are both informational and express the beauty of humanity.

Colgate’s database of alumni includes approximately 2,500 graduates (whom we know of) working in a health care–related field. In these pages, you’ll read about an alumna finishing her residency with Native peoples in rural Alaska, as well as a cardiothoracic surgeon who helped save David Letterman’s life and performs more mini-aortic valve surgeries than anyone else in New England. We talked to graduates who deliver babies and those who hold the hands of the dying.

In addition, we learned from alumni who specialize in mental wellness and complementary medicine. The radiance illustrated by our cover art reminds me of advice offered by JoAnn Inserra ’82 Duncan, who is a Reiki master teacher: “Think of the positive energy that’s out there in the universe.” Many of the alumni we interviewed spoke from the heart about how their work enables them to help others in life-changing ways.

We stretched our theme to explore financial well-being, spirituality, the health of the planet, and, yes, how to organize your home.

Closer to our home, we met with Colgate counselors who are teaming up with athletics to support student-athletes’ mental wellness, as well as sustainability staff members working with our landscape project manager to preserve the campus.

This season of change is a good time to announce a forthcoming modification in Colgate Magazine’s frequency. After the summer issue, we will be combining the autumn issue with the winter issue; and mailing with the autumn/winter issue will be the President’s Report. We surveyed alumni to hear their thoughts on these publications, and we learned that the majority of our readers still prefer to read the magazine in print. Due to rising costs, we need to change our publishing frequency to three times a year, but we are dedicated to providing the same high-quality print publication our readers expect.

Share your thoughts on this health edition by writing to us at magazine@colgate.edu. In the meantime, we wish you all the best for your well-being.

— Aleta Mayne, director of University publications

We Asked, You Answered

In February, we sent a survey to alumni to gauge readership engagement with Colgate Magazine and the President’s Report

Here’s what we learned from the 1,261 respondents

Gender: 69% men, 30% women

Race/ethnicity: 89% white, 2% Black/African American, 2% Asian, 1% Hispanic/Latinx, 1% other, 5% prefer not to say

Age: 50% 65 and over, 29% 50–64, 14% 35–49, 5% 25–34, 2% under 25

Magazine Engagement

Readership: 68% read every issue, 20% read most issues, 10% read occasional issues, 1% never read an issue

Issue engagement: 16% read all of the issue, 46% read most of the issue, 38% read some of the issue

Print vs. digital: 69% read the magazine exclusively in print; 25% read it mostly in print, occasionally online

Favorite articles: 53% favor alumni activities, 39% favor campus life, 8% favor faculty activities

President’s Report

80% of respondents read the President’s Report

Of those respondents, 31% read all of the report, 34% read most of it, 30% read some. Topics respondents found the most interesting, in order of popularity: Third-Century Plan updates, admissions, the financial report, and academic and faculty endeavors.

One reader wrote: I LOVE the Colgate Magazine. The large format allows for luxurious type and photo displays. Generous white space gives the eye and mind elbow room/breathing room for taking in the content. One wants to amble through an article, not race through it. I love learning

about the interesting things that people are involved in. Each story illustrates the value that a liberal arts foundation provides for creative thought and action. I like the combination of big, meaty articles and little tidbits. I admire the excellent paper you use. The landscape photos are so well done. The colors and tone of the cover of the President’s Report make it breathtaking — the rich, saturated gray of the slate dormers and the misty pastel of late afternoon make me stare and stare at them. So for me, reading the magazine is an intellectual and aesthetic pleasure.

Keep up the good work! I am happy for the sound management and ethical grounding of Colgate.

Meg LeSchack MA’68

Spring 2024 Colgate Magazine 5 editor’s letter

Letters

Core Comments

The winter 2024 issue introduced the revised Core Curriculum that the University implemented in the fall 2023 semester. Readers commented on the revised Core and remembered their own experiences.

I am age 95 and was in the first class that experienced the new Core Curriculum in 1946 through 1950. It was a broadening experience, especially the freshman course titled Philosophy and Religion, taught by Quaker professor Ken Morgan, the Colgate chaplain. This was a novel appointment since Colgate has Baptist roots. Quite a one-year course that challenged all our beliefs and laid the groundwork for our futures.

david n. kluge ’50

I was particularly interested in the piece on revamping Colgate’s Core Curriculum. As I reminisce on my days at Colgate and anticipate attending my 50th Reunion, I thought back to the Core Curriculum when I was at Colgate 1970–74. In retrospect there was only one Core course that I remember and had a longterm impact on my life and my career. That was Philosophy, Religion & Drama taught by Professor Jerry Balmuth. Professor Balmuth was not an easy grader, and errors in spelling, grammar, and

punctuation were always marked down. In retrospect, the two critical life lessons I took away from his class were the ability to write cogently and the ability to condense a large amount of information into a short critical analysis of the subject material. This has served me incredibly well in my career. The skills I learned in Professor Balmuth’s class are still completely relevant 50-plus years later. A successful career in just about any field chosen will be based, in large part, on the individual’s ability to think, critically assess, and effectively communicate. I continue to believe in the usefulness of the liberal arts education and hope that Colgate never loses sight of the lessons we learned in Professor Balmuth’s class. The University will serve its students well by continuing to require them to learn how to think, critically assess, and communicate in written form. I expect this is a significant part of the reason that a large percentage of Colgate graduates become very successful in life after graduation.

Bob Chamberlain ’74

The topic of the Core Curriculum has long been important to me. I have remained delighted that Colgate has continued in its Core approach to education. Colgate has withstood and prospered against the aggressive opposition to the importance and benefits of a liberal arts education. I welcome and support that commitment. The Core Curriculum is fundamental to the Colgate experience. I graduated from Colgate in 1963. I did well academically and went on to receive my degree in law from Harvard Law School. I was also one of the first nine participants in the initial

London Economics Study group. I took most of my Core courses in my freshman year. I did not then know my areas of interest, and the Core courses were both a way to avoid decisionmaking, while also participating in legitimate courses. Core 11 Philosophy and Religion, taught by Jerome Balmuth, was an incredible experience. My art course was thoroughly enjoyable and quite broadening. My writing course, Core 22, had an especially important impact on me in that the professor commented positively on my approach to writing. Those words resonated with me, particularly since they contrasted with some of the less favorable reactions my high school English teachers conveyed. Core 22 made me feel good about myself. Then, as an attorney, I went on to use the written word in ways fundamental to my career and my legal and nonlegal undertakings.

In reading the Colgate Magazine story, I found myself being very supportive of the course selections and my sense of their content. I am intrigued by the regular 10-year review. I think a review of those reviews would be intellectually worthwhile. Since my years, six reviews and changes would have been implemented. Most likely those 10-year analyses reflect social and academic trends. Some reflect significance, others the more ephemeral. Both could become learning vehicles. They also become a test of the historic longevity of the Core commitments, commitments that should have impacts long beyond their years experienced by individual Colgate students. I recommend that such an inquiry be conducted. It could well prove instructive and reassuring. In essence, one more proof of the value of the Core Curriculum.

Don Bergmann ’63

For decades, the Core Curriculum has been a distinctive feature of Colgate’s educational program. In addition to the usual freshman composition course (Core 15), my class took six or seven Core courses, spread out over our first

three years, with all students in the class taking the same courses at the same time. Prospective science majors were exempt from the two-semester Core 11–12 sequence in physical and biological science; we took the one-semester Core 10 on the history and philosophy of science instead. As a result, we were all studying and discussing the same texts at the same time: the Book of Job and Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics in Core 17, Janson’s History of Art in Core 21, Friedman’s Capitalism and Freedom, and Galbraith’s The New Industrial State in Core 37. In Core 38, we had a choice of courses on such “emerging” countries as China, India, or Kenya; but even there, a student who was reading Red Star Over China could have a discussion with his roommate, who might be reading Facing Mount Kenya. When the whole student body met in the chapel to consider its response to the 1970 killings at Kent State, the discussion was laced with references to Kant’s categorical imperative: Everyone present knew what that was because all four classes had read Kant’s Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals in Core 18.

With the new Core, introduced in 2023, that has mostly disappeared. As far as I can tell, students in the Class of 2027 will have only one course in common — the Conversations course. The rest is, essentially, a garden-variety distribution requirement: one course each in literature, math, natural science,

The skills I learned in Professor Balmuth’s class are still completely relevant 50-plus years later.

Bob Chamberlain ’74

6 Colgate Magazine Spring 2024

social science, etc. I am sure that these courses have been specifically designed or chosen to be interdisciplinary, or to connect to topics of societal concern. But there is no longer a core holding the entire class together and connecting it with adjacent classes. This is a great loss — to the University and to its students.

I understand that curricula must evolve and that students don’t like requirements. I am also painfully aware that, in these days of increasing specialization, it is difficult to get faculty to teach introductory courses even in their own fields — much less to step outside their comfort zones to teach something that is truly interdisciplinary. Then again, the University has an identity too, and that identity is expressed in its curriculum. Colgate should continue to honor a commitment to the kind of Core Curriculum that makes Colgate Colgate, and that distinguishes its students from those of other liberal arts colleges.

John F. Kihlstrom ’70, University of California–Berkeley, distinguished professor emeritus

The magazine invited Professor Christian DuComb, Core Revision Committee member, to respond to John Kihlstrom’s feedback: I am moved by Professor Kihlstrom’s vivid recollection of the Core courses he took as a member of the Class of 1970. There is no doubt that the new Core includes fewer common elements than the Core of 50 years ago, but the Core remains a fundamental, unifying, and intellectually rigorous aspect of a Colgate education. Professor Kihlstrom’s letter inspired me to review a copy of the 1960–70 Course catalog, in which I discovered a surprising continuity in the Core Curriculum over time. For example, the Core Sciences component in the new Core Curriculum addresses the history and philosophy of science, much

like Core 10; and the Core Communities component offers multidisciplinary courses on regions and nation states across the globe, much like Core 38.

It could be argued that today’s Core courses take a more topical approach than in the past, with fewer shared texts and more instructor discretion over course content and pedagogy. But Colgate today is a different institution than it was in 1970. Members of Professor Kihlstrom’s class could select from among 28 majors (or concentrations, as they were called then). Today, Colgate offers twice this number of majors, in disciplines such as Chinese, computer science, creative writing, and environmental studies — subjects that were barely taught at this institution 50 years ago, but that are essential to a 21stcentury liberal arts curriculum. Today’s students also have the option to double major, to declare a minor (or even two!), and to choose from a much wider array of off-campus study options. These changes reflect the needs of a student body that is 50% larger than in 1970 and significantly more diverse, especially given that Colgate did not begin to admit women until just after Professor Kihlstrom and his class celebrated their commencement. (The first female student matriculated at Colgate in the fall of 1970.) Although some members of the Colgate faculty lament the recent changes to the Core Curriculum, overall faculty participation in the Core is more robust than it has been in years. For me and many of my colleagues, the new Core has reinvigorated our enthusiasm for interdisciplinary teaching by providing a framework that balances flexibility and commonality, and that opens the Core to perspectives that have long been marginalized or excluded from academic discourse. The Core Curriculum has evolved with the institution and with society at large, but it reflects Colgate’s ongoing

commitment to a common intellectual enterprise, shared by faculty and students, as the foundation of a liberal arts education.

Christian DuComb, ColgatE’s associate dean of the faculty for faculty recruitment and development Weekend Reading

I decided to start 2024 with “Screenless Saturdays.” After barely resisting my 5-year-old’s entreaties — “Daddy! I am so bored! I need electronics!” — I sat down to enjoy the autumn 2023 issue while my daughters prepared plastic salads in their living room restaurant.

In particular I could empathize with Jean Gordon ’87 Kocienda’s “The Kindness of Strangers” (p. 10). I volunteered to teach ESL adults for a few years, and they are remarkable people. Many of my students rose before the sun, worked three low-paying jobs, and before returning home to dinner and their families, took my class with more energy and positivity than most people I know, including myself.

For those of you who don’t have young children and do have the time, I can’t recommend [Screenless Saturdays] more.

Jacob Sydney ’93

Don’t Be Afraid of the Dark

I enjoyed reading the winter 2024 article about Associate Professor Jeff Bary’s work concerning light pollution and its effects on humans (“The Bright Side of the Dark,” p. 15). How wonderful that Colgate is fostering research in this arena. Unmentioned in the article but

also of concern is the potential effect light pollution has on other animals and insects. This is another burden that humankind is placing upon a fragile ecosystem, and the question is not if it will cause problems, but how serious will those problems be for those organisms and for humankind.

Robert Rosen P’10,’17

On the Radio

I always look forward to receiving and reading the Colgate Magazine. I was especially pleased to find in the winter 2024 issue a photo of the general manager of WRCU radio on p. 39. I learned everything I possibly could about being on the radio at Colgate and have continued my love of broadcasting ever since. For many years, I was a talk show host in Philadelphia and Washington, D.C. Most recently, I cohost two medical-related shows in San Antonio, Texas. There isn’t a day that goes by when I don’t think fondly of my days “spinning the wax” at WRCU.

Ron Aaron Eisenberg ’64

Spring 2024 Colgate Magazine 7 To submit a letter to the editor, email us at magazine@colgate.edu. Letters may be edited for editorial style, length, clarity, and civility and must be relevant to Colgate Magazine’s editorial coverage. Generally, only one letter to the editor is published in Colgate Magazine by the same author in a calendar year. Letters to the editor represent the individual views of the authors. They do not reflect the views of Colgate University, Colgate Magazine, or its staff.

IVoices

Chasing Fire

n early August 2021 we are in western Idaho chasing lightning bolts that always beat us to the ground. The forest is dry, with red needle cast and sagebrush covering the ground and ponderosa pines dotting the foothills. The hills and canyons are sharp in places and rolling in others, but together the mountains serve as a massive catcher’s mitt for lightning. Lightning that drives up steadily on the backs of giant clouds from the never-ending desert. The desert that stretches from the Gulf to us. The storms are patterned, predictable — that’s why we’re here. Why we lie up at night, sleeping on the ground at a remote ranger station with something like hand-crank Wi-Fi, only powerful enough to check the radar on our phones to see if lightning will start a fire to keep us busy the next day. The duality of wildland firefighting, someone says. You’re either getting your butt kicked or kicking it. I can’t sleep. I turn sideways, so I have a view downcanyon and out over the whole expanse of high desert, and see distant flashes hovering in the sky. In the moonless night, it’s hard to see the clouds that play host to lightning’s energy, so the faraway flashes seem to appear from nothing. Like flickering yellow and white light bulbs high up near the roof of the world. When they draw closer and into the mountains, the thunder I hadn’t heard before now shakes branches loose from trees and causes needles to jump around, and the lightning has a start and end, jagged in between, finding outcrops of rocks or isolated pine trees high on reaching peaks. The electricity

in the air calls my hair to attention. In a bright flash I see my squad boss standing, prepared for rain that never arrives, scribbling in a notebook every time he sees where a bolt lands.

Back in May, deep into the backcountry in no-man’s land between Idaho and Wyoming, we watch a fuels crew set off a prescribed burn at 8,500 feet while there is still white snow on the ground. They drip lighted fuel onto a patch of downed trees and spring back in surprise as it rips upward immediately. We are lined up on a dirt road, holding the burn, which means standing close to the flames and sucking smoke, ready in case fire jumps the road. As the fire climbs and roars like a jet, it becomes harder to brave, but I’m stuck staring, my face glowing hot. I see a lone sagebrush 30 feet away start to shiver and shake and then it pops all at once and becomes fire. Within 20 seconds we are walking, jogging, then sprinting with our 40 pounds of gear as fire jumps the road, uphill and around the flaming front that it has become. I see wide eyes and smiles around me; we’re gripped from the escape we just made, we’re psyched at the new excitement of the day. Later, my crew boss gathers us to say he had never seen that before. Fire did not used to behave like this, at this elevation, at this time of year, in these conditions. But fire does not behave anymore. It sheds genre. It burns through trees still wet from winter.

It’s only my second year on the crew, which means I don’t know anything, so I ask questions, and I listen. In southern Utah’s heat, we hide beneath juniper trees. When

junipers burn, the berries and twigs they’ve shed over the years wheeze and complain beneath them and release a cat piss smell. Under ones not yet burnt we try to escape the sun. Our Nomex shirts used to be bright yellow, our pants green, the Kevlar chaps sawyers wear orange. Now they are browned and blackened by charcoal and dirt, and we blend into the desert. Clear sweat teases its beauty against our ash-covered faces and drips onto the earth below, and we can hear the drops sizzle against the burnt-up grass like bacon grease. The water from our plastic canteens that are kept nested in two side pockets of our faded black packs is scalding. I breathe shallow and slow, relishing in the canyon’s midday calm before my head is filled again with the chainsaw’s mechanical roar. I think that if I follow this slot canyon until it winds and deepens, I must be able to find the cold air slinking around carefully at the bottom of the desert, and a puddle of

8 Colgate Magazine Spring 2024

Perspective

View from hotshot crew member Caio Driver ’20: Unprecedented fire behavior has become commonplace in this changing environment.

Fred Greaves

cold, green water to jump into.

I know how bad the drought is in the West; I can feel it in the heat and I can see it in front of me in fire that’s hardly ever acted this way. I listen when there’s talk of the drought of 2002, or the Yellowstone fires of 1988, or even the Great Fire of 1910. Talk of these watershed events proves two things: though fire seems to disobey logic and reason now, it has done so in the past, and we need to reach further and further back to find parallels to the fire activity we’ve seen in the last decade. This summer, in western Montana and the Idaho panhandle, large fires sparked earlier than firefighters there had ever experienced. When we are in the northern Idaho rainforest, low-mountain country that hugs Washington and Canada, the heat record is broken multiple times over.

The trees talk up here, and they chatter and shriek all night long. Forests chock-full of tamarack, Douglas fir, ancient cedar,

mountain hemlock, and Engelmann spruce — they sound like coyotes in their surprise. They don’t remember heat like this, or nearby fires sparking so early in the summer, in this place that buzzes and breathes.

During the day, I walk through the cedars, feeling their unfamiliar leaves and bark. My squad boss yells from 50 feet downhill: “Watch out for IEDs!” He’s mostly joking, but there is a warning out for this beautiful forest we’re in. Anti-government extremists have been planting explosive devices. I come across a giant cedar that was victim of a different explosion: 20 feet up, it looks as if it had been torn in two, with straps of smoking bark sticking up like an amputation gone wrong, and massive pieces of wood strewn about as evidence of the lightning strike. The trees still standing spew fireballs back at roiling thunder cells, which pass overhead like thick ocean currents. In the rainforest with no rain, we talk too.

Stories are traded like cards. I hear about the way it was through coughs that wrack bodies. In the Great Fire of 1910, the largest wildfire in U.S. history, crew foremen used to grab young men from farms and bars and hand them hoes and crosscut saws to form a crew. How Ed Pulaski — the Pulaski tool now named for him — led his crew of felons, farmers, and kids into a cave to avoid being burned, just 50 miles from where we are now. Still, it’s estimated that 75 firefighters died in the fire. How we used to fight fire under the out-by-10-a.m. rule, which didn’t allow any fire on the landscape, helping to create the overgrown, primed-to-burn forests we have today. How, as recently as the ’90s, hotshot crews used to work 400 hours of overtime in a busy summer, while they now work at least 1,000 overtime hours every year. Working that number of hours in a six-month period grinds down even the toughest bodies, but with the seasonal work, low pay, and lack of benefits, it is also the only way most firefighters can earn a living.

We are sitting pretty at 600 hours of overtime. We get called to initial attack a fire at 2 in the morning. Tucked between a defunct ski resort and a stretch of newly built seasonal homes, there is a stand of fir trees that look black against a moonlit night sky. Some of the trees burn, some will soon. The tips of trees are like cresting waves. We stand to the side as someone falls a flaming tree, chugging powdered coffee and rushing to eat pocket snacks. We throw little sticks and rocks at each other, trading friendly insults, hilarious in our exhaustion. The tree falls and a rush of fire darts into the sky, and I see alluvial washes of embers chasing after the flames before being swept carelessly downwind, to flutter and extinguish in the air, or to start countless new small fires downhill. Alongside the embers, stars dance and blink across the sky.

There’s a gap between what scientists understand and what people have experienced, and wildland firefighters sit in that gap with a tired grin and a mouthful of chew. There’s a lot of science

They don’t remember heat like this, or nearby fires sparking so early in the summer, in this place that buzzes and breathes.

Spring 2024 Colgate Magazine 9

— meteorology, ecology, climatology, atmospheric physics, to name a few — that goes into wildland firefighting. Using these sciences, we’ve almost kept up with the changing fire environment. But in the field we sharpen our tools in the dirt before bed and repair broken boots with superglue and paracord. The currency between us is experience. We talk about slides — each slide is a memory a firefighter has of an incident they were on, when fire behaved a certain way, and they reacted a certain way. The more slides you have to draw from, the more fire behavior you’ve seen, the more likely it is you’ll figure out what to do when you find yourself in a situation you’ve never been in before. In today’s climate, where unprecedented fire behavior is commonplace and we often find ourselves in new situations, slides are even more essential. Slides of extreme fire behavior are ingrained into experienced firefighters, so that when the situation arises, they react quickly. Tales around the campfire double as practice for the real thing. Stories, then, in concert with science, are what keep us alive. There is the simple formula to put out a wildfire: work long, hard hours, using chainsaws and hand tools, to remove fuel from the fire’s edge to secure it. After the edge is secure, go through on hands and knees and touch everything to make sure it’s out. Even with aircraft, engines, and bulldozers, it can take thousands of people working around the clock for months to put large fires out. We wake up every morning in the dirt, head to the fire, cut and dig line around it, then head back to the dirt to sleep. We work 16-hour days for two- or threeweek tours, then have three days off before the next one.

We are sent south from the Teton area, to the North Rim of the Grand Canyon for a new start, only to find it had been monsooned on, effectively stamping it out by the time we arrive a day and a half later. So, we are sent back up north, to a fire an hour from where we came, in remote mountains along the Salmon River. When we arrive, it’s clear why I’d been told it was a storied — and dangerous — place to fight fire. From the network of creeks and rivers, the hills shoot 2,000 feet straight upward at 100% slope or steeper. One side of the canyons is covered in all kinds of pines — Dougs, lodgies, and whitebarks — while the other, southerly facing sides are imposing walls of flammable brown grass, sprinkled with the more desert-happy sagebrush or Ponderosa pine. The whole place is admired by a dull orange sun; made somber by the smoke squatting all throughout the valleys.

At sunset, it feels calm, but with fastburning fuels on that steep a slope, fire can cover hundreds of feet in seconds.

For days, then, we wait. We cut contingency fire line miles from the actual fire. Even so, every morning and again in the afternoon we rehash our escape route, should the winds change and blow the fire upcanyon at us. Five days into our time at the fire, we’re rushed to a cobalt mine, rumored to be the only working cobalt mine in the country, to fight the fire direct. Apparently we have the president’s best wishes. We pick up the line near an immense sludge pond and fall into the normal routine: cut, move, dig. It feels good to be working, to have ash everywhere, to see open flame. The next day, we keep working, picking up where we left off. Only this time, the winds pick up. The forecast predicted this, but not to this extent. Winds flow in at 60, 70 miles per hour. We end up huddled as a crew in the only spot of burntout black where there are no trees within falling distance. A gust sprays my face with sticks, and through the swirling ash I see 30 trees drop one after another. Green trees, dead trees, it makes no difference. All across radio frequencies, people are checking in on one another. It’s frantic, dangerous, and fun as hell.

The next day the incident commander pulls us from the line because the command team doesn’t know whether cobalt — in the air, the dirt, the trees that turned into the smoke we breathed in — is poisonous to inhale or not. With the downtime, we sit at the bottom of a socked-in valley filled with that same smoke, and we tell stories about the last couple days — the medevacs that led

to us being pulled from the line, the wind event. Everyone has their own version of the events. Even our crew boss chimes in, telling us he’d never seen anything like what had happened with the wind event; here was another new slide for him. We feel jerked around, misled, and unknowledgeable. But we’re used to that. We’re flexible; we laugh at ourselves and the job. There’s a saying when the work gets tough: The best fire is the one you’re on.

So why do we chase lightning? Why do we stick our bare hands into the burnt carcasses of trees to see if they’re still hot, though we’re not sure if they might burn us? Not just because it’s what we’ve always done, but because the absurdity makes sense. Nonsense lives in the space between facts and experience, and in the dissonance between the macro and the micro. When a grand canvas is painted, with ineffective politics, millions of miles of ice caps melting, a decried worldwide economic system, then sure — it’s ridiculous for four of us with garden tools to drive, circling on old logging roads cut into mountains, after a wisp of smoke reported by a tourist driving through a canyon miles from here. But when the smoke turns out to exist, when we stamp out the small fire before it slicks off the entire hillside, and we hear the aspen around us dance in the wind, the absurd becomes intelligible.

Even so, there are many more moments to the opposite effect. Times when the job feels so ridiculous, it can’t be coherent. But we know the worst is partnered with the most euphoric; these are the moments we learn to embrace. When we’re asked to dig and cut like our lives depend on it in the

10 Colgate Magazine Spring 2024 voices

Fred Greaves

middle of the Nevada desert because sage grouse is a protected species, and on the third day we look up from our work to see a family of those grouse waddle past us and right into the flaming column. No wonder they’re endangered. Or when we are on day 11 of an assignment and the incident commander keeps us around even though the fire’s out. On a day like this, three of us are sent 100 feet into the black, trudging through charcoal trees and next to candied fields painted by retardant drops. We’re sent to knock out a smoking stump, which essentially means, keep busy. For the next two hours, then, we take turns hitting the stump with our Pulaskis, scraping away the embers to let them cool in the open. We laugh, imitate friends and bosses, and spit. Downhill, away from the fire, the whole of Montana stretches out, just for us. On these days that lack meaning, we find it in ourselves, and in each other. My boss once said that when you’re working a stumphole, on some mountain, on a 100-degree day, and you’re shootin’ the breeze with your crew, life just makes sense.

So when friends and family across the country ask why there is so much smoke and haze in the air, I joke that it’s because I’m not doing my job properly, and hang up the phone to take off my left boot before bed, but not my right, since my ankle is so swollen I wouldn’t be able to get the boot back on in the morning, and it has been this way for weeks. We sleep in a squat valley, 20 of us strewn across the prairied ground in sleeping bag–shaped bumps. Just a few miles away, in the steep, forested mountains, the fire is only 20% contained. We can just make out its nighttime glow. And there are Cottonwoods here, and in them the wind sounds like rain, and rain also comes as dark and meandering virga over the horizon as dogs are beaten and yelp on private land near where we sleep, and there are trains whistling and gunfire pop pop popping in the just barely audible distance. I roll over to my side, and sleep with blades of bear grass crawling over my hand.

Reflection

A Close Call

What a difference a year makes.

Ihave worked in the nutrition world since 2010, and health has been very important to me: eating organic, paying attention to chemical exposures, and incorporating exercise into my routine.

My mom had breast cancer when she was my age, so in early February 2023, as I was turning 44, I decided to get a Prenuvo fullbody MRI scan as a birthday gift to myself. I also had some perimenopause symptoms, and it seemed like a great idea to get a baseline scan so that I could see changes in my body as I aged.

I had learned about Prenuvo, a private company that offers whole-body MRI scans that can detect more than 500 conditions, through my work. I have been studying oncology nutrition and metabolic therapies for several years with the Oncology Nutrition Institute, and I see clients remotely to help them change their health. If anyone was equipped to deal with what was to come, it was me.

went to cancer, and it was a sleepless night.

The next morning, I called Prenuvo at 6:30 a.m. and scheduled time to speak with the nurse practitioner at 5 p.m. I went to work and anxiously awaited my appointment.

When the time came, the nurse practitioner started at the top of the body and with the most immediate concern: “You have a 2.3- by 2.4-cm mass in the right temporal lobe of your brain.” It was the size of a walnut! How could I have had no symptoms? I was dumbfounded. But I kept my calm as we went through the rest of the results, and I learned a few more things about what was going on inside my body.

This defining moment initiated the journey I have been on ever since. At that point, we did not know whether the mass was benign or malignant, but my oncology nutrition spidey sense kicked in. I immediately started a therapeutic ketogenic diet as my training dictates, in case it was the worst-case scenario, and I started working on figuring out other contributing factors that could have impacted this tumor.

Over the next couple of months, I was recommended to one of the best surgeons in the world to do my brain surgery in Arizona. I had surgery on April 5, 2023, at Barrow Neurological Institute. In our consultation on the day before, the surgeon said to me, “Are you sure you haven’t had any seizures? This tumor is compressing your right hippocampus nearly in half, and that can cause seizures.” I had never felt so grateful in my life. A seizure while driving could very well have killed me and/or others.

The surgery went well, the surgeon removed the whole tumor, and I was discharged from the ICU 24 hours after it ended. Two weeks later, I found out that my tumor was a grade 3 oligodendroglioma, which means it was cancerous. What would have happened if I had not done the wholebody MRI? It is impossible to know.

— Since graduating from Colgate as an international relations major, Caio Driver ’20 has spent his summers as a wildland firefighter for the U.S. Forest Service. He grew up in San Francisco, where he lives when he’s not on base in Pollock Pines, Calif. Driver earned his MFA at the University of Wyoming. A version of this essay was originally published in the North American Review on Oct. 20, 2022.

I went in to get my scan while on a trip to the Bay Area. This was the first MRI I had ever had. When it was finished, the tech asked me about a note in my intake form about losing my sense of smell, and I explained that I lost it during a COVID-19 infection in early 2022. I didn’t realize it at the time, but this was a clue to what was to come.

Afterward, I went to work, followed by a dinner with colleagues. When I arrived back at my hotel at 9 p.m., I had a message from Prenuvo, telling me that there was something concerning in my scan, and that they needed to speak with me as soon as possible. I called back, but it was late, and the nurse practitioner who explains the results was not available. Given my work experience, my mind

In the 11 months following the scan, I made great changes to my diet and lifestyle — even moving cross-country in order to be closer to my neurosurgeon and better health care options. Because the entire tumor was removed, I am currently classified as “no evidence of disease.” My surgeon thinks that I will be just fine, as long as I maintain my diet and stay in good health. I will live a much longer, healthier, and happier life, and I am grateful to have had the ability to take control of my health.

— Andrea Schaffer ’01 sees clients remotely through her Mesa, Ariz., practice, Not Just Broccoli Oncology Nutrition. She helps clients personalize their diets and lifestyles to discourage cancer.

Spring 2024 Colgate Magazine 11 voices

Bruce morser ’76

Sustainability

SCENE

Colgate’s Canopy

Since 2018, the University has planted 763 trees — bringing the total number of trees on campus to approximately 3,500. This represents a more than 20%

increase in the number of campus trees during the last five years, excluding naturally wooded areas.

This work “makes campus more beautiful, but it’s more than just that,” says Landscape Project Manager Katy Jacobs. “We’re making campus more resilient.” Adding tree cover and increasing the diversity of tree species on campus helps make

the campus more adaptable to extreme weather and climate change, she explains. These efforts are a mixture of resilience and mitigation, adds Director of Sustainability John Pumilio. “As trees grow, they sequester carbon,” he says. “It’s part of a strategy to reduce the impacts of climate change by taking carbon out of the atmosphere.”

The following numbers are indicators of Colgate’s healthy campus, but they also demonstrate benefits for humans and animals. Forests purify the air, reduce soil runoff, provide cooling, mitigate storm impacts, and provide ecosystem services and habitats for wildlife. “A healthy tree canopy helps make the campus landscape more healthy, habitable, and enjoyable — which is good for physical and mental well-being,” Jacobs says.

→ Most common species of trees on campus: Sugar maple, Norway spruce, Northern red oak

→ Pollution removal: 1,215 pounds/year

→ Carbon sequestration*: 22 tons/year

→ Carbon storage*: 1,830 tons stored in 2021

→ Oxygen production: 57.81 tons/year

→ Avoided runoff: 82,340 cubic feet/year

→ Bird species seen on and around campus: 81

*Pumilio explains carbon sequestration and storage as follows: “As trees grow, they’re pulling carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere and turning it into branches, roots, and leaves. They’re turning the carbon dioxide into carbon, the building material. They’re sequestering it. That becomes the storage. Each time [we’ve measured] our forest, the annual rate of sequestration increased, and our amount of storage continues to increase, which is an indicator that our forests continue to grow and mature.”

These data were analyzed using the i-Tree Eco model developed by the U.S. Forest Service, Northern Research Station. The data were last collected in 2021, so the numbers have likely increased some. “Trees are pretty slow growing, so we don’t anticipate tons of changes,” Pumilio says.

— Aleta Mayne

In addition to campus trees, Colgate has more than 1,000 acres of nearby forested land.

12 Colgate Magazine Spring 2024 CAMPUS LIFE | ART | ATHLETICS | INITIATIVES | CULTURE | GLOBAL REACH

diorio

mark

Q&A

The Essentials of Colgate’s Hiking Club

The wilderness surrounding Colgate University is a nature lover’s dream. In the fall of 2016, the Colgate Hiking Club was established to help more students realize this dream. But during the pandemic, the once-thriving club nearly died out because most of the original leaders graduated. Yet, there were still hundreds of registered members, so Ryan D’Errico ’25 took the initiative to revive the club. By the next semester, hundreds more joined. Today, it has 300 active members and is one of the most popular clubs on campus. “Appreciation for Mother Nature is something a lot of students value,” he says. Here’s more from D’Errico:

What’s the club’s mission?

The Hiking Club provides opportunities for students interested in spending time with each other outdoors in a less formal manner than Outdoor Education’s skillbased P.E. classes. Our more casual and spontaneous hikes on campus are always popular, and we love to go to places in the region that club members suggest. To promote being active in the outdoors to a wide range of students, we have also collaborated with other organizations on campus,

such as Chapel House, ALANA Cultural Center, and Colgate’s international community.

What are the most popular hikes you’ve done?

Probably due to convenience, the most popular hiking destination is the Colgate Cross Country Trails. We have had more than 40 people join us on our on-campus hikes. The trails on campus are a fantastic escape from the hustle and bustle of student life. We have collaborated with Chapel House, meditating before walking through the forest at night. We love touring the quarry, walking through fields of asters and goldenrod, and seeing views of the sweeping rolling hills that surround Hamilton. One fun tradition we have every December is our sleddingunder-the-meteor-shower hike. The Geminid meteor shower peaks every December around finals, making this hike and sledding event a perfect study break. Despite Colgate being notoriously cloudy in December, we have had breaks in the clouds every time we do a meteorshower hike. It’s almost as if nature is supporting our club.

In terms of off-campus destinations, Tinker Falls [in

Tully, N.Y.] has consistently had a great turnout. The hike goes behind a gorgeous waterfall and up to a beautiful overlook. The falls freeze in the winter and create fascinating ice formations. There was one trip to Tinker Falls when the van got stuck in the mud, and everyone had to work together to push the van out!

What’s your favorite memory from a hike?

One great memory I have was from climbing the Kane Mountain fire tower in the southern Adirondacks. I remember being with a few others and climbing to the top of the rickety tower as the wind picked up and we could see sheets of rain approach us. Spectacular views of lakes and mountains in all directions emerged as we climbed higher above the trees, but the visibility soon dropped as the rain engulfed us. The experience was thrilling, with the adrenaline making me feel like I was on a roller coaster. When we reached the top, we looked down at the tiny club members beneath us who could barely hear anything we tried to yell down to them.

— Bri Liddell ’25

13 bits

1

Diana and John Colgate ’57 helped support a new imaging center at Glen Cove Hospital on Long Island.

2

The Minority Association of PreMed Students hosted events with the biology department, including a scientific literature workshop.

3

Fox Sports host Rob Stone ’91 was named the 2023 recipient of the Jerry Yeagley Award for Exceptional Personal Achievement.

4

Dining Services’ “feel good” series put their spotlight on omega-3 rich foods during the month of February.

5

At a ’Gate After Dark event, mentalist Dustin Dean read students’ minds.

6

Former NFL quarterback Tim Tebow met with studentathletes and spoke at a University Church service.

Spring 2024 Colgate Magazine 13

Illustrations by Toby Triumph

▼

The Hiking Club at Bald Mountain in the Adirondacks mark diorio (TOP)

7

A “Helping Is Healing” dialogue about faith, mental well-being, counseling, and charity was led by psychotherapist

Mohammed ElFiki.

8

The COVE hosted two spring break service trips with Habitat for Humanity in Winston-Salem, N.C., and Pathfinder Village in Edmeston, N.Y.

9

Shaw Wellness Institute hosts Wagging for Wellness study breaks with therapy dogs.

10

A group of first-generation students toured grad schools offering public health, psychology, and social justice programs in Philadelphia.

11

A beginner’s boxing class is offered in the Huntington Gym MMA studio.

12

Kathryn Bertine ’97 made the list of 50 Most Influential People in American Cycling.

13

Colgate’s Women’s Studies Program has been renamed to the Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Program

Spirituality Student-Led Serenity

Look around. The warm glow of amber stained glass envelops the circle of strangers and friends — Colgate students and faculty and staff members — gathered for an early morning meditation

At Chapel House, just grab a cushion and engage in a practice that allows student meditation leader Chris Vanderhoef ’27 to settle down, breathe, and reflect.

“As serious as I am about my studies, meditation allows me to step back and say, OK, maybe you don’t have to be a student right now,” says Vanderhoef. “Maybe you can just simply be.”

Vanderhoef’s day starts just before 8:30 a.m., when he heads up to Chapel House to lead a 15-minute session. As an employee of Colgate’s workstudy program, Vanderhoef was trained by Chapel House staff. They encouraged him to attend a variety of their meditation programs, such as guided outdoor walks and their sound-bowl series, to build his knowledge.

“These practices have improved my quality of life,” he says, “so I want to help the campus community by spreading them.”

Since Vanderhoef took Professor of Religion Georgia Frank’s FSEM class called Belonging, Becoming, and Beyond, he has continued to question the beyond. “Meditation is a type of belonging,” he says, as he is often joined in his sessions by returning students. “But there’s certainly a higher level to it, a beyond. It’s really a mysterious practice, with elements you can’t explain.” Student meditation leaders hail from all disciplines, such as peace and conflict studies major Gillian Lustenberger ’27. Lustenberger, who also took her FSEM with Frank, fills the 5 p.m. slot. Her sessions adopt a Zen Buddhist style.

“We focus on the body to improve the participants’ ability to be in the present moment,” says Lustenberger, who has found anxiety relief in the process. “I don’t get panic attacks anymore.”

Each of her sessions ends with a group debriefing, where participants are called upon to share their experience. “To hear that the meditation helped someone relax or be in a better head space for the day is so rewarding,” says Lustenberger.

“I love being a part of Chapel House,” she adds. “It is such an uplifting, welcoming space where people can take a break from their busy lives and just exist.”

— Tate Fonda ’25

Unity. It began with an introduction from Rhoman Elvis ’25 and a performance of the Black National Anthem by Blessed Jimoh ’24.

A trailblazer in LGBT African American history, Brooks shared his perspectives on the transformative power of love as understood through his examination of the sermons of Martin Luther King Jr.

“I feel as though MLK is my personal mentor despite his being assassinated many years before my birth,” Brooks shared.

Drawing inspiration from King’s 1967 speech outlining the three sins of the country — racism, excess materialism, and

14 scene ▼

Chris Vanderhoef ’27 leads meditation at Chapel House.

Mike Roy (BROOKS); mark diorio (Vanderhoef)

At the intersection of love and oppression is where we can find a love drought.

militarism — Brooks delved into the theme of love as a means to combat societal challenges. He emphasized the centrality of love to the human experience, invoking King’s words, “Darkness cannot drive out darkness, only love can do that.”

In the interactive session that followed his speech, Brooks encouraged those gathered to engage in a collective pause, reflect on their motivations for attending, and personally define love. “What is love to the oppressed?” inquired Brooks. “What is love to the socially marginalized? What is love to the person who has been pushed to the margins of society, left out, exploited, and manipulated?”

Brooks argued that love, when unexamined, can become a tool of oppression. “At the intersection of love and oppression is where we can find a love drought,” he said. “So many of us operate and walk around so desperate for affirmation that we actually dry up. We are deprived, become desperate, and finally desiccate. To fix a love drought, a person must be treated much in the same way that a desiccated plant is treated with water: The person must be submerged in love.”

In addition to the keynote, the MLK Week celebration included a unity dinner, a day of community service, a Social Justice Summit, an Interfaith Creativity in Justice Dialogue, and a Sunday service.

— Bri Liddell ’25

Colgate’s celebration of Martin Luther King Jr. was organized by the ALANA Cultural Center and the Office of the Dean of the College.

Eco-art Breaking Down Boundaries, Building Up Community

Drawings by Troy, N.Y., community members inspired the design of the fence posts installed in Professor Margaretha Haughwout’s DE-FENCE. She traced the drawings using vector graphics, which were carved into kiln-fired walnut posts. Colgate carpenter Chris Naylor CNC (computer numerical control) routed the wood. Haughwout then filled the carvings with pewter, a process helped by studio safety technician Kevin Donlin.

Fences coming down and neighbors coming together. That’s the concept behind Associate Professor of Art Margaretha Haughwout’s living participatory art installation titled DE-FENCE.

The installation connects people with their community — and their environment — along the Sanctuary Eco-Art Trail in Troy, N.Y. The trail embeds art, culture, ecology, and history into a nature walk. It’s part of the NATURE Lab, coordinated by Kathy High ’77, which links local scientists and artists with an international network in the field of bio-arts.

The NATURE Lab and adjacent Eco-Art Trail are located in an impoverished neighborhood on 6th Street in Troy near the Hudson River. “There’s a long history of environmental racism [there],” says Haughwout. “So [NATURE Lab does] a lot of work in the community to try to reckon with that.”

Haughwout’s project began last summer with a drawing event during which participants discussed the neighborhood’s environmental health conditions, discovered medicinal plants growing in the marginal spaces and edges of the neighborhood, and sketched medicinal plants that have historically been used for the immune system. Examples include elderberry, which grows in hedgerows and is traditionally used for the flu; yarrow, which is found on the roadside and is for the cardiovascular system; and nettle seed, an edge plant that is used to induce a healthy response to external stressors.

DE-FENCE is “thinking about making the fence line its own

space that can actually bring people together,” Haughwout says, “but also bringing about greater health, greater bodily defense, through collectivity.”

She took the sketches drawn by community members (with participants’ permission), digitally traced them, and etched them onto fence posts she filled with pewter. Participants drew their sketches in a nonlinear way, having multiple endpoints so that they could connect to other participants’ drawings.

This May, Haughwout is placing the first group of fence posts around the living installation — “not in a row, but this deconstructed fence feeling,” she says. During that community event, neighbors will plant medicinal plants alongside Haughwout, whose work typically involves a pedagogical element with sitespecific teach-ins to talk about the context of the project.

Another phase of planting is planned for this fall or next spring. “It’s staggered because I want to see what’s doing well, what might need to be replaced, and work with the site instead of just dropping in, planting everything, and leaving,” Haughwout says.

She told Hudson Mohawk Magazine: “As individuals our health means nothing unless we’re thinking about our larger ecologies, our larger environment, as well as the health of one another.”

— Aleta Mayne Haughwout’s father, Peter ’50, was a medical practitioner, which motivated Margaretha to learn about herbalism at an early age.

Spring 2024 Colgate Magazine 15

SCENE

Sina Basila Hickey for The Sanctuary of Independent Media; Bottom (3): Mark DiOrio

Senior project

It’s Alive!

What do you get when you combine majors in studio art and environmental geology?

A tree in the Clifford Gallery.

A studio art project by Riley Farbstein ’24 comes in two parts, just like her major programs in studio art and environmental geology. The first piece, made of discarded fastfashion mailers sewn together, resembles a dress. The second piece is, well, alive — it’s a small apple tree supported by its own “dress,” made of cardboard and emerging vines.

Farbstein’s project was displayed among those of other senior art students in the exhibition Pushback — a series of vivid, cumulative pieces. With her specialized knowledge in eco-art, Professor Margaretha Haughwout served as her mentor.

“I’m a multimedia artist, so I wanted my final project to combine the topics of environmental consciousness, art, and fashion,” says Farbstein.

Thus, her two-part project came to life — in the first, A Repurposed Fashion Studio, this happened in a literal way.

“I made a dress-shaped ecosystem for a tree to offer a means of protection,” Farbstein explains. “I wanted to critique fashion as a sort of armor or something that only humans have.”

Farbstein’s tree is supported by a base of recycled cardboard in tiers that resemble a dress. A strip of grow lights installed by the Clifford Gallery staff keeps underlying vines and mushrooms alive, as they grow to shape the style from holes and propagation tubes in the base. Farbstein asserts this piece in contrast to its neighbor, Fast Fashion, her mailer-made dress. As vines envelop the base of her treeproject, Farbstein’s Fast Fashion dress remains unchanged.

“Placing my pieces next to each other conveys a message:

the duality of artificial and disposable fast fashion versus more sustainable, conscious protections for our planet,” says Farbstein. “The fast-fashion industry generates so much plastic that just gets thrown away, and a lot of people do the same thing with clothes.”

To make the plastic dress, Farbstein mimicked the massproduced styles sold by fastfashion retailers — she sewed their mailers into a wearable garment, which she displayed on a mannequin.

“By repurposing plastic bags as fabric and assembling a flashy gown, I ask that observers reconsider how their plastic waste can be reutilized,” says Farbstein.

And although her art critiques mass purchasing from fast-fashion websites, she contends that these purchases need not be the end of the cycle.

“By cherishing waste as a precious material, garbage could be reutilized and explored as a source of material,” she says.

— Tate Fonda ’25

Other senior art projects include:

Emma Barrison’s Three Steps to Forget a Memory You Never Wanted to Make overlays personal photographs with colorful brushstrokes to reconstruct painful memories.

Thomas Cernosia’s One and Chairs juxtaposes AI-generated images with his illustrations to argue for the necessity of handmade images in today’s digital landscape.

Jordan Hurt’s Such a Chore social experiment features takehome postcards with playful instructions for mundane tasks (e.g., “Disorganize the silverware!”) to evoke joy and spontaneity in the viewer.

16 Colgate Magazine Spring 2024 scene

Mark Williams (4)

Academics

A SAMPLING OF SPRING HEALTH-RELATED COURSES

Cancer Biology (BIOL 337 A) with Professor Engda Hagos. How can cancer develop, worsen, or eventually subside in affected patients? This course provides students with knowledge of tumor cell signaling, DNA damage, and current therapies as they investigate this medical phenomenon.

Out of Control: Pre-Modern Psychology (ENGL 153 A) with Professor Lynn Staley. What can Aristotle, Virgil, and Homer tell us about the way our brains work? These early writers, who express anger, passion, and despair in their stories, are at the forefront of this contemplative, cross-subject course. Students combine the principles of English and neuroscience studies as they ponder how pre-modern writers have personified the workings of various mental faculties.

Public Health in Africa (ALST 334 AX) with Professor Rebecca Upton. Using an anthropological lens, students in this course review African institutions and practices pertaining to public health. They reflect on the history of the continent up to the present day, where politicians and forms of knowledge production are but a few factors

that influence disease prevention across the region. To learn about these dynamics, students complete a Community Needs Assessment based on in-depth learning about a community on the continent.

Hunting, Eating, Vegetarianism (ENST 324 A) with Professor Ian Helfant. Is the “hunting instinct” an innate aspect of human identity? How do human intervention and agriculture affect ecosystems, and what emerging technological and cultural trends offer promise for the future? These questions, among others, enter the classroom in this ethics-based investigation into how we source our food and what we decide to eat.

Genetics (BIOL 202 A) with Associate Professor Jason Meyers. This course introduces students to the study of how organisms encode, regulate, and inherit their genomes. To engage with the subject, students read primary literature and learn how to design their own studies. They bring their studies to a social-critical level as they consider the ethics regarding genomic editing and other technologies.

Health and Healing in Ancient Mediterranean Religions (RELG 232 A) with Professor Georgia Frank. In parts of the Ancient Mediterranean world (c.500 BCE), illness was defined as more than a physiological problem — it was also seen as a spiritual, aesthetic ailment. In this course, students develop an appreciation for the culturally patterned ways in which people have come to identify and treat bodily distress.

Medical Anthropology: Culture, Health, and Social Justice (ANTH 222 A) with Assistant Professor Emily Avera. Students are introduced to an interdisciplinary field that synthesizes relationships among cultures, institutions, the environment, disease, and healing. Discussions center around cultural interpretations of sickness and healing, the effects of poverty on health, and the importance of doctors in society, among other topics.

Close Relationships (PSYC 342 A) with Associate Professor Jennifer Tomlinson. Relationships can be a source of great joy when they’re strong and great sorrow when they’re weakened. Only recently, behavioral researchers have turned their attention to this familiar process as they inspect the inner workings of platonic, familial, and romantic relationships. In this course, students explore leading theories and empirical studies about adult relationships.

Critical Global Health (ANTH 226 A) with Visiting Professor Milica Kolarevic. This course examines how people experience, use, and critique global health interventions, and why sociological and anthropological approaches to global health are critical to improving these interventions.

— Tate Fonda ’25

Learn how Colgate prepares students for careers in the health sciences: colgate.edu/ academics/pre-professional-programs/ health-sciences

Spring 2024 Colgate Magazine 17 SCENE

Illustrations by Bernie Freytag

Athletics and Counseling Team Up

National statistics show that the number of student-athletes who struggle with mental health is comparable to the general student population. Even so, only 10% of college athletes who have mental health conditions seek help, according to the nonprofit Athletes for Hope.

At Colgate, the Office of Counseling and Psychological Services has teamed up with the athletics staff to normalize and reduce any stigma associated with mental health care.

“Athletes struggle historically to utilize these services,” says Steve Chouinard, senior associate athletics director for health and performance. “There has been an ‘athletes are tougher’ [attitude] that you can battle through anything, from [a hurt] ankle to a mental health issue.” Chouinard has been collaborating with counseling staff members Dawn LaFrance, Christian Beck, and Christy Reed.

For the past five years, Beck has hosted satellite hours at Reid Athletic Center. Students can sign up for a meeting with him or just drop in for casual conversation. In the beginning, Beck wasn’t seeing a lot of faces come through his door, but “now there’s plenty of traffic, so that tells me that there was a need and we just had to make it more accessible,” says LaFrance, assistant vice president of counseling and psychological services.

Beck’s clinical interest is in sports performance anxiety, and he’s also been an athlete himself, so “I’m able to understand their timelines, their commitments with lifts, practice, traveling — all that they’re juggling.”

The counselors also have Wellness Wednesdays for the coaches and athletics administrators, leading seminars, workshops, or presentations on various health and wellness topics. Sometimes, they’ll enlist the help of other Colgate experts — for example, Dr. Ellen Larson ’94 (director of Student Health Services) and professors Krista Ingram (biology) and Lauren Philbrook (psychology) came to talk to the group about the importance of good sleep habits.

“The work we’ve been doing on Wednesdays is invaluable, and the conversations that occur after are sometimes even more valuable,” Chouinard says. “I know, for a fact, that a bunch of coaches feel a lot better having gone through it.”

He says that this training is “not dissimilar to teaching a coach how to do CPR. They can be a really important resource for a student in crisis.” LaFrance adds that they’re giving coaches some skills, but also helping them know when it’s time to refer the students to a counselor.

One assessment measure the athletics staff has implemented is on the survey student-athletes complete before their workouts. The eight questions ask about the student-athlete’s current status and condition, but there are two questions related to mental health. By combining these responses with their personal knowledge of student-athletes, athletic trainers and strength coaches can have a sense of when to check in with student-athletes or guide them toward other resources. Sometimes they’ll refer a student to counseling, but often the conversation can end with the student just being grateful someone is looking out for them.

For an additional safety net, student wellness advocates who are volunteers on each athletic team are trained by counselors to offer peer-to-peer support. “If you don’t want to talk to a coach or a counselor, but you want a resource on campus, they’re well versed,” Chouinard says.

The work we’ve been doing on Wednesdays is invaluable, and the conversations that occur after are sometimes even more valuable.

This multipronged approach is just one part of the University’s integrated health and wellness programming, where staff members from various areas come together to keep students safe and healthy. “We’re learning more and more about how the brain and body work together,” LaFrance says, “so we can’t just involve one area without it all.”

— Aleta Mayne

Volleyball Fifth-Year Senior Continues Career Overseas

Middle blocker Sophie Thompson ’24 signed a professional contract with Volley Club Marcq en Baroeul in France.

18 Colgate Magazine Spring 2024 scene

sports

Mark DiOrio

Thompson will be competing for the team in Marcq-enBaroeul, France, with its regular season running from October–April. Thompson is one of two Americans on the current roster, joined by UCLA star Tristin Savage. The team competes in the LNV Ligue A Féminine (LAF), the top division of French women’s volleyball.

“We couldn’t be more proud of Sophie,” Head Coach Ryan Baker says. “She had an unbelievable career here capped by finishing in the top five nationally in blocks/set during her fifth year. She’s been a tireless worker from the day she arrived on campus, and now she’s doing great things on the pro circuit.”

Thompson helped lead Colgate to its third-consecutive Patriot League championship by leading the conference in blocks and blocks per set (1.53), good for fifth in the country. She set an NCAA single-match record with 17 blocks against Bucknell (Oct. 20).

“Winning the Patriot League three times and getting to compete against top-10 teams in the nation has prepared me for the high-level play in France,” Thompson says.

The Frisco, Texas, native completed her Colgate career ranked No. 1 in the record books in block assists (428) and eighth in solo blocks (90). A second team All-Patriot League selection in 2023, Thompson suited up in 129 matches, compiling 578 kills, 52 service aces, 154 digs, 518 total blocks, and a .285 hitting percentage.

Thompson continues Baker’s strong pipeline of recent graduates — Julia Kurowski ’22, Alli Lowe ’21, and Alex Stein ’20 — as former Raiders to sign with professional teams overseas.

— Jordan Doroshenko

Raising Money for Childhood Cancer Research

Hunter Drouin ’26 was a happy, seemingly healthy kid. But just days before his third birthday, his life and his family’s lives changed.

Hunter was wrestling with his 5-year-old brother, Mason, when Mason landed on top of Hunter. The younger boy suddenly felt a sharp, fiery pain in his stomach. His mother held him, trying to ease his discomfort, until he fell asleep. The hope was he’d feel better after a good nap. But things only got worse.

While Hunter was asleep, he started heaving; his skin turned cold and clammy. He was taken to the local emergency room and then transferred to a children’s hospital in New Hampshire. Doctors found a ruptured tumor in his kidney and diagnosed him with a rare kidney cancer called Wilms tumor, which generally affects children.

Drouin underwent emergency surgery to remove the organ before the tumor spread, followed by months of chemotherapy and radiation. Life slowly returned to normal for Drouin and his family, though every five years he needed blood tests to ensure the cancer had not returned. Drouin has been in remission for the last 16 years.

“If my brother didn’t land on me that day, who knows what would have happened,” says Drouin, a member of the men’s lacrosse team. He wants to use his story to give hope to others with the disease, as well as help raise money for childhood cancer research.

Each season, men’s lacrosse selects a cause for raising awareness and donations. This year, the team partnered with Lacrosse Out Cancer, a

nationwide campaign that raises money for the Pediatric Cancer Research Foundation. Men’s lacrosse gathered donations throughout the season. At press time, the team had raised more than $16,000.

“It means the world to me that my teammates and coaching staff are as invested in supporting childhood cancer research as I am,” Drouin says.