ON THE COVER

Julia Gabitova: Freedom of the Mind

ON THE COVER

Julia Gabitova: Freedom of the Mind

Managing Editors Literature Visual Arts Design & Layout

Patrick Berran, Visual Arts

Dr. Jill Lettieri, Literature

Dr. Jill Lettieri

Isabella Lettieri

Jessica Kesler

Chris Perry

Michele YoungStone

Patrick Berran Fay Edwards

Tiffany Lindsey

Christina Lorena Weisner

Brittany Forbes

This magazine is the eleventh annual edition of Estuaries. It features creative contributions from College of The Albemarle students, faculty, staff and community members.

Mignogna: Stellar Verse

Engner: Solitude

Still

Vazquetelles: Existential

Mize: WhelkinCopper

Mignogna: Geo Chrome

Ephemeral

Ness:

College of The Albemarle (COA) is dedicated to fostering an inclusive, diverse environment. We ensure equal opportunity across all facetsadmissions, employment, and access - and prohibit discrimination or harassment of any kind, based on race, color, national origin, sex, age, religion, disability, or veteran’s status. We actively recruit and support a diverse community of students, faculty, and staff. The following individuals have been designated to handle inquiries regarding the non-discrimination policies: (Employees) Ella Fields-Bunch, Director, Human Resources, 252-335-0821 ext. 2236, ella_bunch44@albemarle.edu; (Students) Kris Burris, Vice-President, Student Success and Enrollment Management, 252-335-0821 ext. 2251, kris_burris76@albemarle.edu.

Ashley Hurst

You are the reason my heart beats strong, The light that guides me, where I belong. Areighna, Ainsleigh—my every choice, I’ve built my life upon your voice.

In a world I feared, I forged new ground, Breaking curses so you’d be unbound. For you, I left dark paths behind, To shape a future, whole and kind.

Like flamingos fade, pink hues drained deep, I give my colors so you may keep The brightness, strength, the world you crave—

In love, I give all that I gave.

I live for you, my loves, each day, My sacrifices, my debts repaid. No drink, no smoke, no careless stride, Every step, with you by my side.

I’ve grown and changed, left scars to heal, Pursuing dreams made strong, made real. For you, I study, I push, I learn— With each page turned, for you I yearn.

Strict, yes, because I see the way To give you strength for each new day. I live for you, my colors true, In every step, in all I do.

You saved me, my girls, my hope, my flame— Because of you, I have a name. As mother, guide, with love that grows, In each pink hue my heart bestows.

So take my love, my hopes, my dreams, For in your laughter, my purpose gleams. For Areighna, Ainsleigh—my reason to be, I live, I thrive, for you, endlessly.

Elle Everheart

In this quiet moment, the world slows, the hunt feels distant, and I’m drawn to its grace, a reflection of my own frailty. Each heartbeat is heavy with regret, the choices I’ve made swirl around me, where pain and beauty intertwine, and I wonder if there’s solace in the silence before the dusk, as the shadows creep in, and I breathe in the weight of it all.

This is how I loved you

All summer in reds and pinks

And yellows swaying in the breeze

You watched the delirious bees and butterflies

Rush from flower to flower I gave them

Everything I had and asked for nothing but sunlight and summer rain

I know how much you admire them wishing to live

One day anchored that fast in the present

Feverish with singular purpose

No time to despise yourself

But you are loved

When you stood next to me and closed your eyes

It was not a dream

Or an impossibility you heard me whisper it

I love you

You are forgiven

Even as I arched towards the sun

Through that hot July I knew this day would come when the cold wind would blow over

The blue ridge and scatter the last of the leaves across the garden

All my seeds gone given to the hungry goldfinch

Now all that is left is my dried seed head twisted and bowed resting like a jagged crown on my brittle stalk

To remind you

Of the summer

When I drank all the sun’s fire

For you

We gathered at the table, not with knives, but with words sharpened from years of hunger. They looked at me like prey, with soft eyes that hid their intent. A hunger not for flesh, but for the marrow of the soul. I felt their teeth long before the bite, how they savored the pieces I didn’t guard, gnawing at the soft parts where my silence had made me tender. And I let them eat.

I let them strip me bare, bone by bone, until there was nothing left but the hollow echo of what I used to be.

They call it survival, this way we consume each other in quiet rooms, disguised as conversations and well-meaning smiles. We are the feast for the ones who feed, endlessly hungry, swallowing what remains of ourselves.

Kendra Graham

The bones of dead butterflies rattle in the pit of my stomach at the thought of you Now, essentially a stranger, an unspoken name. Stolen tenderness has transformed into daily waves of nausea.

A distant, chilling piano melody in the soundtrack of my life. A vinyl record scratched beyond use, condemned to sit on a shelf and collect dust forevermore. A reminder, a warning, endless and useless yearning. Cementing you in my past before you ever considered me a part of your future. Another muse lost to dust but I’m sure the color of your eyes will still bleed from my paintbrush.

Your memory will live upon my canvas and the ink of these pages, your fingerprints visible in the pen smudges, your laugh in the crack of my notebook’s spine.

Filled with what-ifs and could’ve beens, overwhelming and destructive. I am cursed and left with these memories you no longer care to remember.

Ashley Hurst

Each day, a battle within my mind, A war of scars left far behind. Raised in fear, I wore that cage, A child caught in her father’s rage.

I tried to shield, to keep them safe— My mother bruised, my sisters’ faith. His fists found me; I took each blow, Silent wounds they’d never know.

Behind my eyes, a story untold, Of shattered youth and growing cold. Happiness scares me; it’s fragile, thin— When joy appears, fear slips in.

I learned young to guard my heart, To build walls strong, to play my part. Happiness feels like risking loss, A gift too fragile, with too great a cost.

Small triggers pull me back to then, Where demons lurk, dark memories spin. Anxious thoughts take hold, they’re sly, Haunting me, my endless why’s.

In shadows, I found choices lost— Love marred by pain, at a heavy cost. Drinks numbed, but couldn’t erase The echoes of my broken place.

Yet when my daughters filled my life, I vowed they’d never know such strife. But anger haunts me, raw and real, A storm I try so hard to heal.

I tell myself, “You are strong, you’re free, You’ve broken chains no one could see.” Each day I rise, though burdens weigh— I long to live, not just to brave.

I’ve tasted peace, that gentle light, Yet holding it close feels like a fight. But still I strive, though shadows call— To build a life where my daughters stand tall.

Julie Simons

A rose in bloom beneath a meadow tree –

The breeze sets the blossom’s sweet scent free.

Other flowers can never compare

To the rose’s perfume so fragrant and fair.

A rose in bloom in the morning light –Glossy red and pink petals make quite a sight.

Bursting in color on a sunny day, One bright flower keeping clouds away.

A rose in bloom on a thorny stem –

A sharp barrier to guard this radiant gem. But thorns can’t defend against the pain

Of blooming alone through shadows and rain.

A rose in bloom with petals unfurled

Meets another who’s forsook by the world.

This noble blossom is set apart

To connect all those with shattered hearts.

A rose in bloom plucked from the ground –Proffered to the love whom the lost one had found.

A new home, a flower that gilds a vase, Where abounding love fills the humble space.

Alas, a rose in bloom whose time has come –Wilted and dead, it seemed to some.

But to the couple, more than a flower: It was a symbol of love’s enduring power.

A rose once-bloomed now returned to earth Whose value far exceeded its worth.

A true joyful beauty, through sun and rain –Growing tall, bringing hope, despite lonely pain.

This singular flower’s final wisdom to impart: Always keep a rose blooming in your heart.

Devon Fulcher

My first page, a woman in a camo shirt with the American flag on her faux denim shorts.

The second, a cartoon flipping through twenty dollar bills, outlined in hard black marker. A luxury brand logo, with light pencil pressings from the way it was traced onto a template after being finished.

And as the gray lockbox containing a tattoo machine was passed into smaller, less calloused possession, so was I.

Then on my forty-seventh page, a persian cat taking a stroll, and a young woman with a head full of vibrant golden hair.

The fifty-third, a square, cut out and turned into a crane that sits displayed on a close friend’s cluttered desk, and an attempt at a man’s hand that didn’t turn out quite right.

I always fell into the right hands just as they grasped desperately at empty air before me.

There’s a place where the river bends, where the world pulls away from itself and you can hear the Earth breathe. I’ve gone there on days when the sky feels too heavy to hold, when my thoughts run like water but never seem to find the sea. It’s not the river I go to, but the stillness it leaves behind. The way it moves without hurry, carving paths through rock and root, without ever asking if it’s allowed. Here, time slips between stones, wears them smooth like the edges of forgotten promises, and I wonder how long it takes for something so solid

to surrender to the soft touch of water. The birds don’t stay long, but they sing as they pass, their song a fleeting reminder that the world is always in motion, even when you feel still. I sit by the river’s edge and let it teach me how to bend, how to move with what comes without breaking. Because in the end, it’s not the rushing that shapes us, but the gentle persistence–the quiet, unseen ways we are worn smooth by all we carry and all we let go.

Se’Quan Parker

Creativity and dreams are what drives the soul

It is what will help me reach my goals.

When I walk this road, uncertain of what is to come my way I shall strive to push myself forward day by day, whether it be the storm

The judges of our impending doom, or the swarm of demons that haunt our sleep. We will not falter my friends, do not weep, for the light will guide us to this cavern’s end. Dreams are what give us hope, they are what ignites the fire in your soul, Which is the one thing the monsters of the night could never uphold I see visions of riches and gold within our journey.

We were growing ever so bold, never with a sense of fear or worry

Kendra Graham

To sit with so much sadness, comfortable and familiar on my shoulders. So much unexplained grief a soul aching with, and for, tragedy. The fragility of peace, of contentment, only feels more precarious and dangerous by the second. Loneliness, like a familiar friend, waits in the passenger seat of my car in the morning. Familiarity lends itself to a trap. A well worn path to destruction, an old favorite song I know word for word. I sit in the sun, mourning the past and future alike. The “would’ve, could’ve, should’ve”s, the forgotten dreams. Rivulets of misery tracing the imperfections of my skin. The storm lives within me, lulls and pauses, but never truly leaves. Even on the sunniest days, it haunts me.

Elishka Nuzzo

Sometimes, we are not ready

Readiness is no blessing from God, but the unmatched thunder of desire

Emitting from deep in our bellies

It is when I get desperate that I must remind myself that I too, once Sat in the nest on the high branch

Watching the others, with limbs too brittle to chase or stomp

When I was ready, I threw myself out from the quiet

And found you, talented and coiled

And the others, with love that cannot be stowed

I will say it, tomorrow as much as today

How I love you despite the condition under which you exist, raw and human

You may laugh at me or give me that look

Wherein your pupils, that flare before me, dart to the next thing

I could dwell and drift from you, but I will stand

Reluctant and tall

Beside my fleshy heart, which pulses at you

We are not always ready

I am not consistent with remaining independently proud

I trip and cry, as I assume that the baring of teeth means anything other than weariness

But you do not bark, because you simply are not ready

Whether you yearn to hold me with stories of the inside does not concern me

We both know that you do

When the hunger comes and you grow curious to know the name of the song I sing

Carry yourself out

I will always offer you the answer

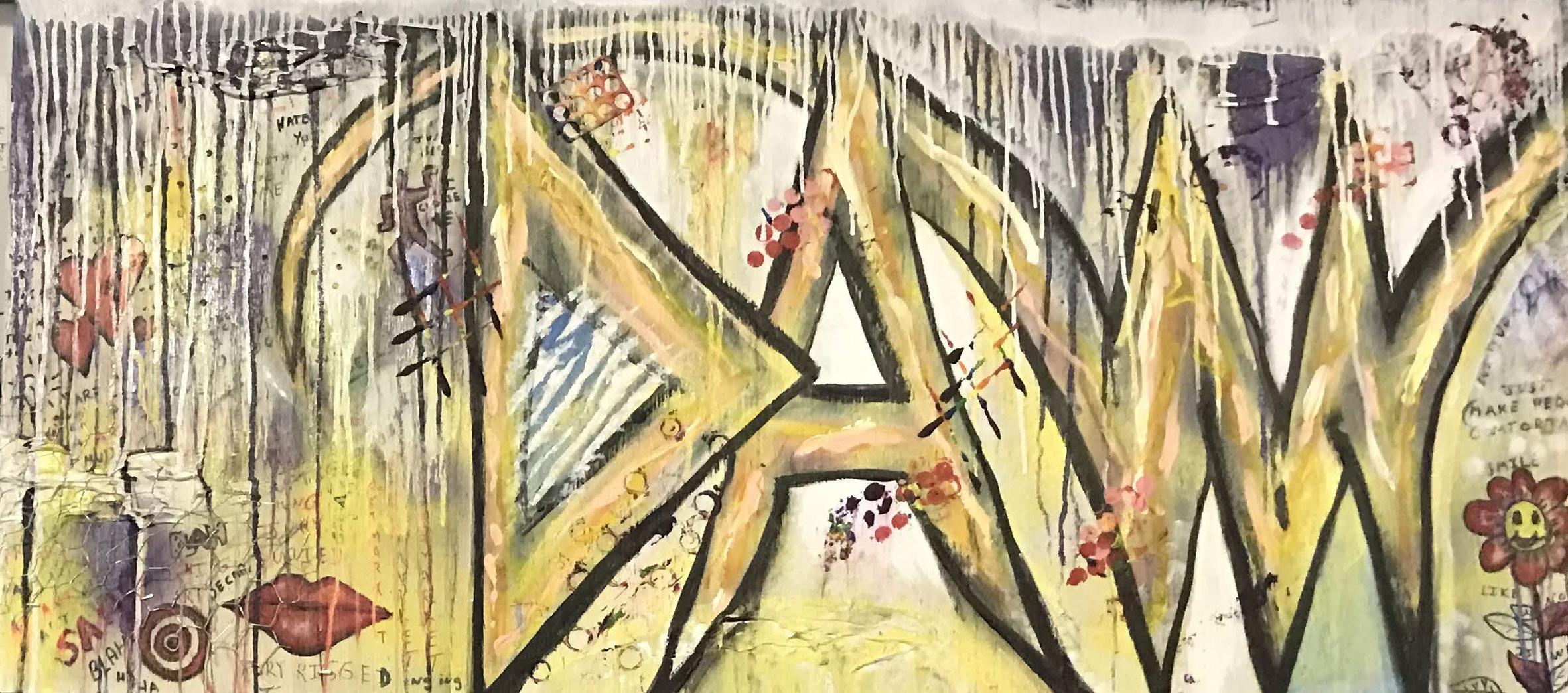

Emma Vazquetelles: Existential

Alice Turney

All my life I have loved the water and the things you can do in and on it, such as skiing, boating, fishing, swimming, and floating with my face to the sun. I like the smell of the ocean, the sun’s warmth on my skin, the sand under my feet, and the treasures to be found on the shore. The birds fascinate me as they scurry and search for little aquatic urchins barely buried in the wet sand. I love seafood, and family gatherings at a special cottage where we all get too much sun and eat too much. I have many cherished memories, most of which revolve around the beaches or rivers in North Carolina.

I also had some near death by drowning experiences. When I was nine months old, my brother, who was eleven, stood in the beautiful Carolina Beach surf, holding me in his arms. My mother watched us from the shore. Without warning, a rogue wave crashed into us, knocking me out of my brother’s arms. Frantically, he began to search for me, but to no avail. Mother panicked and began to run ten paces one way and then ten paces the other hoping to see where I was and direct my brother in the right direction. I was gone. I cannot imagine the fear that filled the two of them as they stared at the endless waves while they felt so completely helpless. It was probably only seconds, but it must have seemed like the world stood still and time stopped. Their thoughts were racing as their fears heightened into panic. Suddenly, mother spotted me washed up on the shore. She rushed to picked me up, not knowing if I was dead or alive. She probably squeezed me a little too tightly and maybe inadvertently pushed out whatever water I had in my lungs.

I protested her embrace with much kicking and squalling. I was alive! I had salty sand in my eyes, ears, nose, and mouth. My head was a matted mess of hair and wet sand. I was not crying from any injury caused by the assaulting waves. To their surprise, I only wanted to go back to the ocean. I don’t know who was more relieved, my mother or my brother. Mother, slow to recover from the event, kept me away from the water for the rest of the vacation.

My Uncle Guy had a cabin on Blount’s Creek near Chocowinity, North Carolina. We often went there for family fun and to fish on my daddy’s little John boat. The cabin was everything you would imagine a fishing cabin should be. Pine floors, iron beds, and little wall plaques spouting wisdom. “I love work. I could sit and watch it for hours” quipped one wall hanging that gave us a little chuckle.

Over the bar hung a large, humorous picture of a group of dogs in brightly colored scarves and hats. They sat laid back, smoking cigars, and playing poker. One of them held an Ace between his toes, while others tried to keep a poker face, as if that was possible for a dog to do. The picture always made me stop and smile as I stared at the details. Without a lecture on the dangers of cheating, drinking, gambling, and smoking, or the improbability of dogs actually doing such things, I somehow knew the picture was not there to teach me anything, but rather to enjoy its comic relief.

My favorite plaque was in the bathroom. A raw wooden box hung on the wall right in front of the toilet. It had a glass front and inside was a very old, very dry corn cob, which of course was void of corn. A tiny hammer hung from the side of the box.

“If you run out of toilet paper, break glass,” the sign directed. I cringed every time I pictured any occasion which might require the use of the rough corn cob substitute. I made sure there was always plenty of TP.

There was a big fireplace in the family room with overstuffed chairs and a brown, well-worn leather sofa. Two poker tables sat ready with playing cards and red, white, and blue poker chips stacked around a brown plastic caddy with cradles for holding the chips. There were board games and jigsaw puzzles in cardboard boxes showing scenes of winter and fall. The house was surrounded by a pine grove and the soft sandy floor was covered with a thick layer of pine straw. As a child, I spent hours of pretend-time raking paths to form rooms, while playing with my imaginary friends. It was a delightful second home.

A never-been-painted small, old garage in which a car was rarely parked stood in the side yard. This was a good thing it was empty, since all the bamboo fishing poles were kept over-head across the ceiling beams. Daddy’s job was the heavy lifting and then he would start to work on the fishing tackle and poles. He had taken down the hammock and hung it between two big pines. This was always our place to wrestle, not sleep, and many times someone would get dumped out on the ground. It was great fun, and no one ever got hurt, except for their pride.

I don’t ever remember being afraid of the water growing up, which is probably why at two years of age, I took an innocent walk to the water’s edge. It was that time of year when fall trees had shed the last of their leaves and winter was creeping in. It was an unusually chilly day, and Mother was in a hurry to get settled. My older sister and brother unpacked the car for the week’s stay. Everyone was busy with their assigned chores, Mother was giving directions, and putting things in their place. My siblings were hauling in suitcases, boxes of food, and sundry items. Daddy was untangling the many fishing poles, taking off the old lines, running up the cork bobbers, replacing the hooks, and led weights. Everything needed to be ready when it came time to fish. Mother was busy getting the kitchen stocked for when the fish were caught, cleaned, and ready to fry.

I’m sure someone was assigned to keep an eye out for my whereabouts, but with all the hustle and bustle, it was easy to forget who was supposed to be watching. I became bored just like you would expect a two-year-old would after a long trip cooped up in the car. So, I wandered toward the pier. Fortunately, someone realized I was missing and everything came to a screeching halt. The search was on. I was found standing in chest high water, wearing my heavy clothes for the colder weather.

“Why did you go to the water, Alice?” Mother half-heartedly scolded me, feeling a little guilty for her neglect.

“I was going swimming,” I said, completely nonplussed by all the hysteria. Saved again.

Do you remember the movie, Jaws? It was a big hit in 1975. It came out in June of that year and millions of people decided not to go in the water, ever again! It was terrifying. My husband and I watch it huddled on the sofa, knees pulled to our chests, hiding behind pillows ready to cover our eyes at the first sign of the shark, or the blood-curdling sound of the absolutely heart-stopping music. How could three musical instruments, composed of six basses, eight celli, and four trombones, repeating the same four notes, E and F or F and F sharp, create such horror? A person doesn’t even have to watch the movie! The music alone gave me chills and nightmares.

My lack of fear and respect for the hazards of water disappeared overnight after watching Jaws. I was forever changed. Every time I was in the ocean, I became as vigil as a soldier on the front lines of war. It was almost impossible to relax and enjoy the waves I had loved so much through the years. I found myself going in the water less and less. If I was alone, I stayed on the beach. When my husband and I had company, I made myself go in the water at least once, but it was never fun. I refused to go out over my head, but always stayed where my feet were on the bottom or landed on the bottom after a wave. If they didn’t, I fled to the shore. I was a fair swimmer, but not great, and certainly no match for a great white shark.

Unfortunately, the ocean cares nothing about my fears or my skills. Its character is to remain an alluring body of water, capturing all my senses. The repetitive sound of waves curling and crashing always draws me in. It is both frightening and exhilarating. The surface shows off its hues of blue and green, sun-studded with diamonds, dazzling my eyes. Its breakers spill on the shore spreading a skirted-edge trimmed with white foam. The waves repeatedly roll on to a sandy floor carpeted with tiny creatures, where opalescent shells lie waiting for discovery. Birds instinctively dance and sing to an unwritten song played for thousands of years. When there, I often take a deep breath to smell the ocean air and taste the salty mist. There’s no other place like it.

On a hot August summer day in 2016, my granddaughter and I went to the beach at Nags Head, North Carolina. We laid out our towels and put up our brightly colored umbrella among the masses of other sunbathers at Jennette’s Pier. We stayed until we were pinked-up from the hot sun and the heat became unbearable. The water was a little rough, but there were no “No Swimming” flags out. We decided to cool ourselves off with some fun in the surf. I relaxed enough to enjoy a few waves, and we laughed and managed to keep our heads above water most of the time. My granddaughter decided she needed to go in and get the accumulated salt and sand out of her eyes. I thought I might stay a little longer. It was a mistake. I felt the waves were becoming more forceful and more frequent. The height was also different. The water pushed me higher and then it happened. When I came down, I could feel the under-tow pulling hard against my legs. I labored to stand and tried to bury my feet on the sandy bottom. It didn’t help. The wave was readying itself to return with more force and it hit me hard. When it released me, my feet did not touch bottom. It was definitely time to head in; but before I could move toward the beach another wave slammed into me and this time, I was horror-struck.

It felt as if something under the water grabbed my ankles and pulled me backwards. I knew it wasn’t a shark, but there was so much power in the current I was unable to do anything but let the ocean have its way. The wave slammed me to the bottom and held me there so long I thought I would surely drown. I battled to hold my breath. My face scraped the gritty ocean floor and then the force thrust me to the surface. I frantically looked around for help. My fear escalated when I saw my granddaughter heading back into the surf toward me.

“Go back! Go back!” I screamed as loud as I could, wildly waving my arms as if I was able to will her to leave the water and return to the sandy beach.

I thank God everyday she understood my warning. She turned and stood frozen at the shore keeping an eye on me. By this time another wave repeated its pounding and under I went. I knew I had to hold my breath and when I surfaced, I gasped for air. I looked to find someone who might be near enough to rescue me. I saw a man about twenty feet to my right on a small boogie board.

“Help me! Help me!” I yelled as loud as I could. The sound of the surf and the roar of the waves drowned out my cries.

I was so fearful of sharks; I could not make myself swim parallel with the beach which may have helped me get out of what I now realized was a riptide. I tried, but I just couldn’t do it. The very thought of purposely swimming out into deeper water was too terrifying. There had to be another way.

I was in panic mode, and I needed to keep my fears at bay so I could concentrate on what to do next. I resolved to fight the waves not knowing if my plan would even work. Another wave came like an angry bull. A repeat of the downward force, the fight to hold my breath, then the upward push. I resurfaced with only a few seconds to recover. I swam as hard as I could toward shore before the next wave hit me. I desperately tried to hold on to my sanity. If I could make some progress, I would be encouraged to keep trying. I saw a lifeguard truck on the beach, and I felt renewed hope and courage to persevere. Every time I came up, I waved my hands and screamed for help. But no help came. Could no one hear me? Did they not see I was in danger? It was then I knew for sure I was alone in this battle to survive. There was no time for self-pity.

Determined, I began to feel emotionally separated from my impending fate. It may have been akin to the feeling I had when I was nine months old and two years old. The dauntless innocence of a child and the reality of danger was a chasm I was restrained from crossing. Although I have no way to be sure if this was true for me back then, I was sure it was true for me in that moment. I didn’t invite it, it just came. At that moment, I felt I was resigned to the possibility of dying, but not without a fight.

˜ ˜ ˜

With the next wave, down I went. I searched for my footing and found the bottom. I waited until I felt the receding wave begin to lift me up. I pushed with all my might and with what was left of my stubborn will. My effort was rewarded. I pressed through the surface of the sea and dove straight out toward the beach, trying to stay as close to the surface as possible. Again, I repeated the same move. Again, and again, and each time I was grateful to see I was gaining a little ground. There was less pull backwards and the water was getting a little shallower. By the time I was out of the waves, I was too exhausted to stand. A kind couple came to me in the surf like Jesus walking on water. I fell into their arms, and they helped me into a beach chair. My granddaughter stood by me, and I could see how frightened she was.

“I’m alright. I’m alright.” I said, trying to comfort her.

Our day at the beach could have been a nightmare. The events of that day leave me thankful and sobered. I will never take the ocean for granted again. It is unpredictable and my fears and naivety almost cost me my life. ˜ ˜ ˜

Several years later, my husband and I spent a lazy afternoon on Pea Island beach. It was a very calm day, and the water was delightfully warm and clear.

“Would you like to try going in a little bit. I’ll stay right by your side and keep all the sharks away,” he said with a teasing smile.

“I should face my fears head on, I guess,” I said as I yielded to his gracious offer. “Stay close though. Okay?”

“Sure,” he said, taking my hand, affirming his faithfulness.

We didn’t go far, but I did it! The dip in the calm waters was short but reassuringly sweet. I felt victorious, no longer a victim to what I was convinced had its control over me.

That one simple gesture felt as if he had reached back to the day I was swept away from my brother’s arms, the day I stood in icy water, innocent, unafraid, and the day I felt the sea pull me into darkness. In that moment, his strong hand drew me into a new reality. It was a spiritual awakening, like being saved from harm, kept from death, and sovereignly rescued.

˜ ˜ ˜

I don’t know if I’ll ever be 100% comfortable in the ocean, but baby steps help reduce my inner turmoil. Due to the fact of my limited skills, strength, and endurance, I will never go into rough waves again if I can help it. Mostly I’m content to stay on the sandy shore, relaxing, reading, and getting a good tan. The ocean still is beautiful to me, and I find myself drawn into its mystery.

˜ ˜ ˜

I’ve learned to have a deep respect for the ocean. My determined efforts to overcome the riptide’s hold on me could have eventually drained my energy, leaving me to surrender to its power, never to surface again. It is a fact; people drown because they underestimate and fail to understand the ways of the sea and overestimate their own power. Knowing these things about the ocean can save a life. Before going in the water, do a little research about riptides, how to get out of one, and what not to do. Riptides are an unexpected danger, void of mercy. Of this I can testify.

Every year someone gets caught in this phenomenon of the sea. Don’t be like me. I discounted the remarkable wildness of the ocean and its unbending character to be true to itself. It can be so serenely calm and untroubled; one can see their mirrored image reflected on its surface. At other times it becomes the mythical Poseidon, rising out of the depths, crashing, churning, swirling, foaming, unpredictable, and constantly changing. My advice--enjoy the sun and sand. Enjoy the beach and all its wonders, but above all remember: The ocean acts as independently as the weather, constantly reminding us of our inability to control what refuses to be conquered without its permission.

I’ve learned a great lesson. These three events have shown me that I can be helpless and still be rescued. I can wander into danger and still be found, and I can be pushed to my limits and still survive. Above all, it has given me a high appreciation for family, friends, the good will of strangers, and the importance of keeping a balance between enjoying a great adventure and using wisdom so you can live to tell about it.

Dawn Van Ness

It was the acrid whiff of smoke from a cheap burning match that ignited my memory. Striker.

Hours, days, and nights around my dad’s pit fire, the pit fire he’d made by digging out a hole as long as a body in the clay that he surrounded with bluestone granite rocks, rocks almost big enough to be boulders. Most had taken notches out of his tiller’s blade during the first spring he’d lived alone in the woods. The tiller was no match for the crops of rocks. The pit fire was a monument to them as it was to other things.

The pit fire dad had made for his camp was on the top of a hill. The camp was in the middle of acres of pines. No electric lines. No pipes. No well. The land was outlined in barbed wire strung tree to tree. The trees’ trunks bulged over the rusty wire and consumed it with their scars. Only thing that would lead you from the paved county road to camp was a winding scar of a dirt road.

That, and a drift of smoke. Smoke drifted from the pit fire day and night and got into everything.

I came back home reeking of smoke.

After a few days of camping, the misty mornings and damp evenings of the season that made the bullfrogs chirp and trill, turned my clothes and sleeping bag sour.

It was always smoke. Even without fire.

Like the smoke from the end of dad’s cigarette that seemed to forever dangle from his mouth. He spoke out of the side of his mouth with the cigarette holder clamped between his partials. The artificial teeth and plastic holder clicked when he talked. The cigarette mostly lit out of habit, burning slowly down.

A smoldering drift.

A tendril.

A whisp extending into the air.

Ash growing spreading absentmindedly haphazardly carelessly

Unlike how he stood

Steadfast Focused Resolved

looking down a line of barbwire a row of pepper plants bunches of collards

The rest of us, his family, left in the background, just as thin as the drift of smoke, growing faint, fading, just a fact or afterthought of his exhalations, never to be breathed in pleasantly again.

My dad had decided that life with most people, including his own family, was intolerable.

He would prefer the whippoorwill click and call to the tick of a clock. He would prefer the moon and the stars to night lights. He would prefer wind to a fan, a fire to a heater, a rain barrel and a bath in a bowl to indoor plumbing.

He walked away from everything civilization had to offer but toilet paper. Toilet paper he kept on hand in a watertight cooler, safe from the gray mice that would nip and rip it and take it up to the frying pans hung on the walls to make their nests and their bedding.

Walls. Walls was an overstatement. What he had was mesh wire stapled to cedar posts with plastic sheeting stretched over it and blankets hung as needed to keep out the wind or keep in the heat.

It wasn’t fit to call a tent.

It was a shelter. Adequate and ugly. Trashy looking. Discarded. And over time the clay splashed up during storms, or maybe he even shoveled it in around the base, making it look like it was becoming one with the hill.

Our dad. The recluse. The survivalist. The hermit.

The makeshift tent was barely shelter during a storm or when the temperatures went to freezing in February day after day.

Mom worried over it in the beginning. Sister remarked on it especially when she wanted to drive him into the ground.

During the dead eyes of winter and during storms he managed to sit up hunkered down close to an old wood stove or hunched over the fire pit at night. Then he’d find comfortable sleep during the day. It just depended on how extreme and uncomfortable it got.

He always knew he could make a judgment call and make it work. If someone remarked on it, he’d ignore the comment without even a shake of his head. He saw the average human as weak and incapable, and that included his own family.

He had survival training. He knew he could be dropped in the middle of a jungle or the tundra, and not only survive, but make his way to civilization.

When he was younger, civilization would have been the objective.

Now civilization was the thing he encountered reluctantly, unless he absolutely had to. His fields, his trails, his pens and shelter and lean-tos. His pit fire was civilized enough. It was civilized more than what he saw towns and cities as. Chaotic. Undisciplined. Full of unnecessary laws and superstitions, and rituals and punishments for weak people. Full of conflict.

In the beginning, we expected him to return to the suburbs, but he wouldn’t, not until a crop came in or he had too many eggs. He returned in his busted ‘67 red Ford to share a harvest or to pick me up to help him with a project.

“He’s out there, punishing himself.”

My sister said with the authority of someone over 15 years older than the person she was addressing, but with little understanding of what she witnessed. It wasn’t clear to me what she saw, ever. Dad had never been close to her like she wanted, and the lack of attention festered into heat and anger inside her, imagining favoritism of his other daughter. She seethed and smoked over the supposed neglect. It pleased her to say he was punishing himself, imagining himself in pain or in danger, versus feeling the sting of his rejections.

Maybe it was because I knew him no other way, but I just accepted that my dad lived in the world two miles off of paved county road with only a broken mailbox saying that he was there.

If I was to see him, he would come get me, which he did seasonally. He needed an extra pair of hands to help with the planting or the harvesting. He needed someone to hold the barbed wire taught while he hammered in the staples. He needed someone to help build back the road and reinforce it with stones.

It never occurred to me that allowing me to stay long weeks or weekends living his lifestyle was anything but the way things were.

I didn’t know to be ashamed or concerned, because after a short time, my mom didn’t seem to care or be concerned. She seemed relieved. Lighter. I never even asked myself what my mom was doing those weekends and those weeks that I was not home in the suburbs with her.

Your mom doesn’t like to camp. She’s a city girl.

“He’s out there punishing himself,” my sister would say at the breakfast table over coffee.

He wore ripped up clothes, torn by pliers, barbed wire, even torn by a goat grabbing his pant leg impatient to be fed. Cuts on his arm would be crusted over with blood. He’d have scrapes on his knuckles, dirt under his nails. I’d see him smile, smoking a cigarette, ash getting longer and longer till it fell to the ground, knocked loose while he hammered in a stake, a nail, or a hook, repairing a fence that was damaged or loose.

If I talked too much or got bored, he’d send me into the woods to find and bring back a bull, a bull that was as docile as a bovine could be, content to follow me even at 8 years old. He’d follow me back, knowing full well there were persimmons or something else sweet in a bucket next to the gate.

Dad loved to treat his animals, even the ones he planned to have butchered.

When I got up at sunrise, dad was already up with the birds. He was drinking coffee, making biscuits and frying bacon in cast iron pans atop a grate licked by flames. The grate was some steel rack from a discarded oven or some other junk. In later years, he collected some duct work and assembled a makeshift chimney. It did not work as designed.

Smoke would come out sideways, making my eyes water. I’d cough and move to another side of the fire and inevitably the smoke would shift around and find me.

smoke follows beauty, but I don’t know it works fine when you aren’t around

I didn’t take this as a compliment or insult. It was just dad. Teasing. And unlike my sister, I could take it and the smoke.

smoke follows beauty but I don’t know….

What didn’t you know dad?

These weekends and weeks of the seasons would last forever. And I never wanted to go back to the suburbs and the schools and sit at desks till my back hurt while wearing shoes that gave me blisters. Taunted by the words of little boys and little girls who could see I was odd and ill at ease. Dad had made me odd. I was raised to be awkward in the confines of school.

It was his fault.

I was attached to the skies that were massive and astounding. The Milky Way stretched out overhead and I knew the stars without being told. The Milky Way was apparent. Undeniable. Obvious. It was thick and rich with dusty light. The night sky was something else. I felt like I could reach my hand up and drift my fingers through stars, dust, gasses, and clouds. I could imagine the clouds swirling around my knuckles. The moon was not the moon but an entire other planet. It was so large on the horizon it appeared you could walk up the hill and just climb up onto it. The first time I saw an orange harvest moon I felt like an astronaut discovering Mars. Was I really on earth when the universe was so close?

“He’s punishing himself out there. No one lives like that.”

Surrounded by sun and blue sky and the trill of cicadas or crickets, dad and I walked between rows of red, green, and gold peppers, asparagus, tomatoes and corn. We stepped over vines of watermelon and honeydew, dusting them with seven dust to keep the beatles at bay.

We’d eat chili or stew out of coffee cups and drink tepid tea.

There were trails left by firefighters when there was a forest fire years ago. The trenches they cut through were perfect to follow from hill to hill, and down into the bottom of a creek that was forming. At some point some of the smaller trees started to disappear, leaving pointy stumps. They reminded me of pencils sticking up out of the ground. Left by giants.

Beavers were the culprits. They were cutting the trees and damming up the creek, starting small ponds.

This animated my dad. He found an old chair and a bucket and a piece of plywood, made himself a chair and table, and watched the beavers and watched the ponds grow. One summer he had a fishing pole and he started to fish. I had no idea where the fish would come from, but sooner or later he caught one.

I learned that he had captured some fish from another pond and put them in the beaver pond. Soon ducks, cranes, and geese started to land and rest, confidently striding along, sheltered by the cattails.

Somehow word of the beavers spread and the next thing he knew he had people cutting the barbed wire line, coming over, and trapping them.

And that’s when he started to get dogs. First, it was just a pair and then it was a pair more. He repaired the fence and let the dogs run, eat, and sleep with the livestock. He walked the property with them checking the wire.

Then he found a deer stand on his side of the wire. He took the stand down and when another was put back up, he cut down the tree.

He got two more dogs, larger than the others, and let them run loose.

Soon when I came to stay, we were greeted by a pack of dogs. They barked, yipped, whined, and howled running around his truck as we bumped down a windy road. Eventually we had to just pull off and park under some trees because the road had washed out too much.

“He’s punishing himself living out there.”

We’d walk up and down the hills for about a mile till we came up on his camp.

The dogs ran circles around us, running in the woods, running back, running to the animals, barking, barking, calling all the livestock to the fences. Shouting their excitement. Some livestock stayed where they were, like the goats and sheep who would only look up. Others meandered, like the bull and the pigs, as close as they could get, stopping at the barbed wire, leaning in to have dad scratch their backs, rub their muzzles, or stroke their ears. Sometimes he would grab a couple of fistfuls of berries, or persimmons or whatever was around and toss them some at the very least. He would grab some wild, sweet grass and drop it over the fence line, promising to let them out in the field later.

“No one lives like that.”

In camp I saw traps hanging from a tree. I didn’t ask. I didn’t ask why there were so many more dogs and why the dogs were so big. We had one named Bear. I just would hold on to his neck and squeeze him tight. I could sit on his back and ride him.

I didn’t ask why Dad walked around with a pistol and a rifle as well as his knife. I didn’t ask why when he said I needed to always at least carry a machete.

At some point, he thought I should start carrying a gun.

I’d never been scared of one till he started insisting on teaching me to shoot. It was his insistence. There was urgency. And then there was disappointment when I resisted. I didn’t see it as necessary either. There was nobody around and we had the dogs. There was Bear and Bully. They were there protecting us, scaring off the wild things.

Just like your mom. City girl.

Dad took me out to some stumps with bottles and cans and lined them up.

You can’t stay scared of stuff

He gave me a brief lesson on stance and how to hold a gun and how not to tense up and how to breathe.

“Breathe and release and squeeze“

Squeezing hard, it resisted like it was rusted tight. Finally, snap. Quiet.

Again. This time be ready.

Squeezing hard it resisted less or I squeezed harder. Snap. Quiet. It hurt my hand. To hold it.

I hated the whole damn thing. This chunk of metal shoved into my life. It didn’t belong in this world of star strewn skies and dogs big enough to ride and pet bulls. Beaver ponds full of silver fish. Harvest moons and whippoorwills.

Then I just did it. I squeezed hard. Everything exploded. The percussion broke me open from bone marrow to the base of my skull. Tears welled up in my eyes and I yelled.

“What the hell was that for!!!”

Dad took the gun from my hand, laughing, ash falling from his cigarette. He checked the gun over.

bad gun terrible recoil If you can deal

S Sh Heh hit target

The words meant nothing. Ringing in my ear. Sour taste in my mouth. Heart pounding. I was angry. I hated guns then. He knew it. He’d set me up. He’d wanted me to learn to shoot and carry a gun and this was how he went about it.

You’ll get used to it, he said later at the fire.

But things had soured between us.

I felt like an idiot. My dad had trophies. He’d trained soldiers. He wanted something from me that wasn’t there. And he’d gone about it the worst way possible.

You’ll get used to it. Shoot good enough with a bad gun you’ll be good with anything.

But I’d been set up.

Between my mother’s world and father’s world. It’d forced me to choose sides. He’d put a wedge between us.

It reminded me of all the other bad lessons. Bad fishing trips. Bad fencing. Bad tilling and pulling weeds. The harder it was on me and the less I succeeded, the happier it made him. I felt lousy. I had no understanding. I couldn’t. I felt awful. I was awful.

I soon concluded he wanted to feel superior and so I quit trying. His insistence on carrying a gun and learning to shoot pulled down the magic.

Then he backed over Bear and Bully got caught in the barbed wire and had to be shot.

He’s just out there punishing himself. No one lives like that.

He stopped having me around summers.

I started to get summer jobs that paid and put gas in my car.

I laid around the beach in a bikini with friends.

I painted my nails and rode in cars with boys. I learned to make myself small and fit in.

I felt awful at the jobs I took. Awkward. Odd.

I quit my jobs and kept moving to new ones. Waitress. Hostess. Cashier. Temp.

Time skipped ahead and I lost track of those seasons walking trails and looking at stars. I found a job I wasn’t awful at and a boyfriend who didn’t know my family. Then family called.

“When did you last talk to dad?”

Accusatory.

The question was hard to answer. I never talked to dad.

I got a letter sometimes that I meant to save but it would get thrown out.

March 12, 1996, Tuesday, 54.5* F

The weather was fair.

The asparagus will be good this year.

A dog had puppies early.

One looks like Bear.

I’m giving them away.

A goat died.

Love, Dad

Dad died.

Dad had died.

He passed away in his camp. People missed him at the corner store in May and June. He was missed at checkers and chess. The librarian had books for him but he never came for them. He hadn’t gotten gas in a long time. Post office box was full but still sparse. The remaining dogs were going feral and had started leaving the property.

Some neighbors had started shooting some.

The sheriff finally came around to find his camp and found him in July in his tent. The tarp on the roof was gone. He was laying on his back On an old army cot

Looking up at the sky

Natural causes. Probably.

Standing on a fresh cut lawn of green

Under blue skies

And a yellow sun

A thin, young black girl played taps

A short, blond white boy gave mom a flag. People said things about a service man I never knew. Medals. Honor. Service. Distinguished.

No one mentioned he was a survivalist.

You can’t be scared of stuff. Breath and release. Let the recoil shatter your marrow. If you can deal with that You can deal with anything.

Oh my god. I wanted the big skies.

Alice Turney

I was six when my Daddy died of consumption. The last days of his life were wasted away lying on an old brown army cot temporarily set up in our dark sitting room. He lay there alone, while Mama and the four of us children, Melissa, Edgar, Beatrice, me, and Jake, my baby brother, stayed in the rest of the house. No one lingered in the room long because of the sickness, but Daddy sometimes asked that I be allowed to come in. “I’m so hot, Sweet Pea. Please uncover my feet.” he pleaded with a voice thick and wet with phlegm. He lifted a weak hand, pointing toward his bare gray toes. I knew he wanted me to give ’em a good rubbing, as he would say. So, I did. Sometimes, we heard Daddy’s fits of coughing way into the night’s wee hours. Exhausted, he lay deadly still, sleeping. A merciful gift, short lived. Day by day, the coughing returned with a vengeance, a relentless villain.

When Daddy was feeling well enough, I would sit close so he could brush out my long wavy, auburn hair until it was tangle free. He gently rolled each of my locks around a clean white rag. Together we knotted and tied them tight for the night. In the morning, I had a head full of ringlets which I proudly showed off. This did not endear me to my sisters and Mama fussed, saying it was a bother taking care of such a mess of hair; but Daddy insisted it not be cut. His intervention convinced me I was indeed my Daddy’s favorite. Over time, my hair was brushed and curled less and less. Daddy’s strength left in slow stages and we felt him slipping away. When Daddy married my Mama, she was hardly more than 16. Old enough, I guess. “Grandpuh” as we called him made a deal with his good friend Mister Matthew, a widower with two children, and that was that. Grandpuh had one less mouth to feed and Mister Matthew had a brand-new mama for his two motherless children, Melissa Jane and Edgar Gene. Mama always called Daddy, “Mist’a Matthew,” I guess because he was just 3 months younger than her Daddy. To Mama, calling him Matthew sounded a little disrespectful.

Times were hard. People had to figure out how to make ends meet. No one faulted the practice of marrying young, having children soon thereafter, and as long as a woman could bear, she kept on having babies. If a man could work, he kept on working. Sometimes there was nothing a man or woman could do but bow and scrape. At least that’s what I heard around the supper table.

Bea was my older sister and there was an expected amount of responsibility to carry. I didn’t need much care, but Jake! What a handful. Mama was always needing Bea’s help.

“Take Jake for me, Bea. Hang out the diapers to dry, Bea. Check on your Daddy, Bea. Bea! Get Jake away from the fire!”

Bea and Melissa were constantly needed, and no one questioned the fairness of it. The older siblings were born with a calling, leading the way for the younger ones. Melissa took care of Edgar, a fearless boy of ten. Bea took care of me and Jake. I too got my share of instructions.

“Don’t grumble or complain, just do it. Even if you don’t feel like it, do it anyway.” Bea commanded. She was bossy, definitely not the warm and fuzzy type. She cared deeply for me, and I loved her for it. When I was frightened or sad, she would read to me the Adventures of Huckleberry Finn or Robinson Crusoe. For a while we could forget the sickness, the chores, the constant gray shroud that seemed to loom over our heads like an impending storm. Books were her passion and our escape. Even though I didn’t always get the meaning, it was her steady calm voice that comforted me.

We all knew eventually Daddy would leave us, but we tried not to speak of it. Curiosity got the best of me, though, so I decided to ask.

“What will happen to Daddy in the end, Mama?”

Her hand rested heavy on my shoulder and I stationed myself on the high stool next to the warm cook stove. I knew Mama had us sit down when she wanted to tell us something important. Almost holding my breath, I listened with great interest.

“One day Daddy won’t cough anymore,” Mama explained. “He’ll go to sleep and when he wakes up, he’ll be in glory.”

I contemplated this vision for a minute or two, cradling my chin in the palms of my small hands, eyes closed. It sounded good to me. I figured Daddy would love to wake up any place other than the hellish sitting room he lay in for so long. Mama was right. Two days later, Daddy went to sleep and woke up in glory.

To prepare Daddy’s body, Mama and Aunt Bessie carried warm water and fresh lavender soap to the kitchen. They carefully covered the clean plank-topped table with a heavy, white linen cloth. Uncle Willie and Uncle Mann came in bearing Daddy’s blanket-veiled body. They gently placed him on the table. Both men stood still, holding their hats, then bowed their heads as if in prayer. After a reverential moment, they nodded to Mama and left without a word.

I squatted in secret peeking through the crack of the barely opened kitchen door. Melissa and Bea were watching from a distance, keeping Edgar and Jake out of trouble. I refused to stay with them, despite their protests. Bea remained reserved, but Melissa was so tenderhearted. I once saw her kneel by Daddy’s bed after supper till late at night. She was our watchman on the wall. She whispered the Lord’s Prayer and long pleaded for Daddy’s release from suffering. She was always the first to give care and show compassion. Her helplessness now overwhelmed her, knowing the sickness had won the fight.

Slowly Mama began to pull back the quilted blanket and Daddy lay naked, motionless. His youthfulness had disappeared. His shell-like body was all that remained. I tightly shut my eyes trying to erase the cruel image of death. The night-thief had finally finished its work, stealing a good man’s life, and I hated it.

Opening my eyes, I watched as Mama and Aunt Bessie shaved and bathed Daddy, speaking in soft whispers. Mama traced a birthmark on Daddy’s shoulder saying she had never noticed it before. She smiled as if discovering a precious stone by a stream or a fallen iridescent feather from a rare bird. They methodically went about the washing, turning his hands, lifting his legs, gently, as if Daddy was a stillborn baby, loved and lost. The strong soapy scent of lavender filled the room, and I felt its peace.

The day Daddy died, Mama called me. “Get out your Daddy’s Sunday suit,” she said.

I found it hanging in the hall closet. I stood on my tippy-toes. It was heavy and I struggled to get it down. I gathered it up in my arms to keep it off the floor. I loved its earthy smell and held its slightly rough texture against my face.

“The material is made from sheep’s wool and sometimes it smells of lanolin,” Mama proudly said and copied my touch and smell of the fabric. We smiled at each other.

“This suit is wool gabardine,” she said squaring her shoulders and gushing with enthusiasm. “And it’s so tightly woven it’s waterproof!”

She carried on as if she was the store owner at Austin’s Mercantile. I wondered why that was an important feature for a man who was dead, but I didn’t ask for fear of ruining this moment of happy reflection.

“They say gabardine is a garment worn by travelers, like pilgrims,” she continued.

Bea had often read to me the story of Christian in Pilgrim’s Progress Instantly, I knew why it was just right for Daddy’s burial. He was leaving one home and going to another, a better place indeed.

With quiet grace, the women dressed Daddy with meticulous care in his best white shirt, starched and pressed, brown socks, brown Sunday shoes, and his gabardine suit. When it was all done, they straightened themselves and looked at Daddy one last time. Mama cried. Aunt Bessie put her strong arm around Mama’s shoulder, consoling, speaking tenderly, relating as women do when they lose a husband. They stood quietly for a spell and then began to put things away. I had forgotten to breathe and quickly caught my breath. Suddenly I was sorely aware of how lonely I felt and bit my lip, trying not to cry. I quietly stepped off the porch, not looking back.

My uncles returned, laid Daddy in his coffin, solemnly placing his hands across his chest and straightened his clothing. The next day, Mr. James, the grave digger, who was also a good friend of our family, came promptly at 10 o’clock that morning. The men folk helped him slide Daddy’s coffin into his old, open wagon. It was made of rough, weathered lumber, but Mr. James had painted the wagon seat a bright blue.

“Why blue?” I asked, as Mr. James thoughtfully smoothed out a black wool blanket to warm his mule’s broad back. Then with a quick jerk, he tightened the straps, giving an affectionate pat, pat, pat to the mule’s flank-side.

Happy to explain his reasoning, he said, “The bright blue helps people forget a little bit of their griev’n. Makes ‘em feel like they’d seen heav’n, right up there over their heads, even on a cloudy day when there’s no sunshine to be had.”

Mr. James thought a lot of his blue wagon seat. I agreed and thought the color was perfect, for Mr. James had the bluest eyes I’d ever seen. They twinkled and peeked teasingly out from under his work hat, which did a poor job of covering his thick, wavy, reddish blond hair. He had the warmest smile, the kind that made

you want to sit and listen as he told tall tales of fight’n in the war, working at the mill, plantin’ fields of ‘bacca, and being a grave digger. On warm Sunday afternoons after church, the re-telling of his adventures delighted mothers while he kept small children sitting cross legged and quiet for a good long while, eyes wide with wonder.

As Mr. James had promised, the digging was done, and Daddy was lowered into his six-foot grave. The funeral was set for 2 o’clock, after lunch so none of the mourners would come hungry expecting food and could leave in time for supper. The Pastor from the Baptist Church presided over the service. I slept through most of his long-winded sermons so I had no idea if he could pull off a good funeral. Mama would have it no other way though, so there he stood in his one and only gray suit and black shine-less shoes.

Mama didn’t own a black funeral garb, but she looked beautiful to me in her best Sunday dress. It was soft blue gingham with tiny white lilies that looked so real I thought I could smell their early spring fragrance. She had a full figure. Even under her heavy knitted shawl, one could see her gentle curves and generous bosoms ‘cause she was still nursing little Jake. Her sandy blond hair was just curly enough to sneak out from the edges of her brimmed, navy wool hat, framing her deep-set eyes. Her fair complexion, the color of peaches and cream, was porcelain-like. When she smiled her whole face lit up, like a room filled with mid-morning sunshine. The cold weather caused us to shiver, as a raw gust of wind turned up our collars and our shoulders unconsciously hunched over. All five of us children had on every stitch of winter clothing we owned; even Jake was double-diapered. We too were void of anything black to wear, but Aunt Bessie had made black crepe arm bands for each of us, even one for little Jake.

Funerals were an important part of country life. Even if you didn’t know the deceased, a funeral could turn out to be a good place to see local drama up close. If you were lucky enough not to be discovered as the fella no one knew, you could get away with eating more than your share of some mighty fine food. Knowing we

always had food at family funerals, I thought it oddly unusual that on this day, there were no tables or chairs and no food or fellowship in the church. Suddenly, a dark cloud covered the sun and for the first time I felt something was very wrong.

I had heard about mourning, and I had seen, mostly women, moan and wail at funerals, but today it was curiously silent. My Daddy’s relatives, which we never saw, arrived all sad, with frowning faces and down turned mouths. They just looked like backward folk to me. Mama, who rarely had a bad word to say about anybody, said they were nothing more than drunkards and needed hangin’. Their expressions were probably meant to say they were serious grievers who had come to pay their respects, but Mama knew they weren’t there to grieve or give respect. Of course, arriving with a wagon full of yungins in tow was a convincing way to show they needed help to get over their great loss. I was sure my Mama was not impressed or moved by their fake masks of sadness. She was smart. She knew what was about to happen. I didn’t have a clue.

We watched in silence as our family’s menfolk covered my Daddy’s wooden box with freshly turned dirt. Uncle Willie, Uncle Mann, Aunt Bessie, and Aunt Agnes stepped back behind us like a readied army, holding their shovels cross-armed over their chests like loaded guns. Ready, I didn’t know what for; but I found solace in knowing they were there. Mama held my baby brother Jake on her hip and squeezed my little hand in hers.

My very stoic older sister, Bea, stood emotionless, not even a tear. She had a way of keeping everything inside, hidden. I looked to her for comfort, expecting some warmth, some sign that she felt like I did, fatherless, but there was nothing. I couldn’t tell if she was mad, sad, or glad; but she was my dear sister, and I knew she’d tell me later what she had locked inside.

Edgar wrapped his small arms around his sister’s thin waist, trying to work up his courage. Melissa leaned over and spoke quietly into Edgar’s ear, cautioning him to stand still. They tried to hide themselves as best they could. I could not figure out why they were hiding. Why were they so afraid? The air was tensionladen and instinctively I moved myself closer to Mama and Jake.

The pastor’s lofty prayer was longer than Daddy’s eulogy, allowing the cold to test our reverence. My whole body seemed acutely chilled as if anticipating a menacing storm. As soon as the pastor’s “Amen” left his lips, the fictitious mourners moved in. One family turned on their heels and began to quickly load up their wagon. The tribe’s father swiftly walked toward Mama as he searched our faces.

Finding Melissa, he quickly broke through and grabbed for both her arms. It was as if she was glued to Edgar and adamantly refused to relent. He proceeded to snatch her this way and that way like a rag doll, and yet, it earned him no success. His embarrassing failure only fueled his anger and fired up his resolve. Obviously, he intended to take her by force, but he had underestimated Melissa’s tenacity. He found it impossible to separate them and resorted to verbal threats. Edgar turned and stood like a little soldier in front of Melissa, showing his brave-heart to defend her.

“Get back, boy, or you’ll regret it!” the gruff man yelled at Edgar. His hot anger flared as he tried desperately to wedge himself between them. Edgar bit his arm like a rabid dog. Yowling in pain, he jerked himself away from both of them.

“You little brat,” he growled. He raised his hand to slap Edgar. Quickly Melissa moved Edgar behind her in one swift motion. Edgar tried to sidestep her, but she kept him out of reach.

“I said let him go,” he spat the words in Melissa’s face. He gave a cautionary glare at Mama and a forewarning stare to the army behind her. It was then I realized their shovels were held in a tight grip by their side. They impatiently rocked from one foot to the other in a fretful posture and I felt my anger ignite. Why did no one come to rescue them!

“These two belong to us, not you! Don’t none of you think you can keep these young’ins. They’re Matthew’s not hers!” he shouted, pointing a dirty finger at Mama. Raising his voice, the unwelcomed, contentious brute began to yell even louder as though he was giving an announcement to everyone present. “You have NO legal rights!”

Seeing no sign from Mama to do otherwise, nobody moved. The air around us was electrified and everyone felt it. Startled awake, little Jake cried out and I heard Mama whisper her shushing sound in Jake’s ear.

“Shush, shush, baby. It’s all right. It’s all right,” she said softly, fighting back her tears.

Everything about country life was slow, anger was not easily riled, and violence was rarely carried out; but at that moment, I tried to step forward, gearing up to kick the man’s shins in and flail his chest with my fists. Mama realized my foolish impulse and firmly seized my hand, pulling me back into the ranks.

“Get over here and help me,” the horn-mad man called to his gang. Mama’s whole body shook next to me. Jake squirmed, wanting to be released from her tightening grip.

“Do something, Mama! Do something!” I wanted to scream it out loud, but my mouth was so dry the words were stuck there like the barb of a bitter root. I had no understanding of Mama’s plight. She had no legal rights to keep Melissa and Edgar. She had no bargaining chip. My innocence had sheltered me from the truth. She was powerless to win the battle she faced that day.

Mama surrendered and stepped away from Melissa and Edgar. The weight of their vulnerability was crushing. Despite the fact of Mama’s forbearance, I knew it was the most courageous thing I had ever seen my Mama do.

Unclear as to what to do, I searched Mama’s face, but she gave no sign to guide me. We watched in horror as Melissa, kicking and screaming, was swept up and over into one of the wagons while Edgar, our little soldier, was carelessly dumped into another wagon like a disobedient dog. Melissa’s screams pierced our hearts. Bea and I felt Mama’s knees begin to buckle and we reached out to steady her. From somewhere deep inside, she drew up strength to stand firm. We all stood speechless like fragile glasses ready to break under pressure.

“Edgar Gene, I promise I’ll find you and I’ll get you back. I promise!” Melissa cried out one last time and then collapsed broken-hearted on the wagon floor. Covering her face with her hands, she shook with uncontrollable sobs. She couldn’t bear to see Edgar taken from her. Edgar remained quiet, resigned to his fate, still the little soldier. No one said a word as their wagons creaked and groaned under their loads. The mules shouldered their harnesses and braced themselves as they pulled against the weight. Whips cracked and the mules brayed and snorted, as if in protest to their master’s cruelty. We watched in silent despair until they disappeared from our sight. Everyone stood in shock, painfully aware of the abyss left by our loss.

Mama had released my hand. Her normally soft, fair face was stone-cast. Her free hand was now clenched into an iron fist. Unknowingly, I clenched mine as well. They swooped in like vultures and took what was precious to all of us. Not once did they say, “I’m sorry for your loss.” Nothing. They robbed my Mama of her children that day and she was incensed. The weight of another loss was overwhelming. Trembling, she knelt and pulled us close, crying inconsolably.

Drained and exhausted we looked to Mama for direction. For what seemed like hours we waited. Finally, she resolutely stood and planted herself on a nearby gray stone bench. Our brave shovel-bearing family members made a reluctant retreat to their wagons, traveling home to prepare supper for us. Beatrice carried Jake and we gathered by Mama’s side. It seemed we sat there for the longest time, still, quiet, until our warmth left us, and melded into the stone we sat on. We huddled close together trying to warm ourselves.

Mr. James shied up beside us and gently touched Mama’s shoulder.

“Mister Matthew is covered real nice, Miss Pearl,” he spoke as if in church. “I can take you home now if you like or wherever you’re wantin’ to go. Just let me know when you’re ready. There’s no hurry. No ma’am, no hurry at all.”

Mama took a deep breath, then yielded up a slow sigh. “No, it’s time to go, I think. Thank you, Mr. James,” Mama said graciously. She stood, steady now.

As she drew up her shoulders, her voice cracked. “I’ll have need of your wagon in a few days to move me and the children in with my brother Willie. Do you think you could help me out when the time comes?” she asked pensively.

Mr. James nervously twisted his hat in his hands. He managed only a soft, brittle, “Yes, ma’am,” that told on him. I looked up to see his face growing crimson, but with a quick turn, he looked away, embarrassed. Firmly re-placing his hat, he headed to his wagon.

Mama’s eyes were losing their angry redness from stinging tears and returning to the crystal blue I loved so much. The setting sun yielded to the winter’s evening stillness. Somehow, I knew my strong-willed, powerful Mama would wait and plan. Time would give us room to heal, and laughter would return to our home. I knew in my heart Mama would fight to keep us together and gain Melissa and Edgar’s safe return. The day would come when our family would be whole again, but for now, we had to move on.

Mr. James pulled the wagon around and we loaded ourselves up into our places. I sat between him and Mama on the worn, well-loved blue wagon seat. He gave a blanket to Bea and Jake as they snuggled together behind us between two bales of hay. Handing one to Mama and me, I saw it was gabardine, warm, and heavy. Its wooly smell reminded me of the pilgrims, such as we were now, leaving one place and going to another.

Mr. James clicked his tongue and called “Giddy-up” to his mule. The mule raised his head and responded to the grave digger’s gentle touch on the reins. Slowly, he drove us home. He was right. The blue wagon seat did help us forget a little bit of our grieving. I looked up to the nearly clear starry sky and wondered what heaven must be like without sorrow or tears. I knew for sure; Daddy would tell us all about it when we met again.

Rhonda Bates

Rhonda Bates has been a student in the Jewelry Department at College of The Albemarle for the last three and a half years. She has explored many different aspects of jewelry making. Her passion has become copper enameling. She started out as a painter and copper enameling has provided another surface to paint on.

Jessel Bullock

Jessel Bullock’s microscope land art symbolizes her profession as a Medical Laboratory Technologist, highlighting the primary tool. The small invention allows her to analyze small things beyond the naked eye to diagnose illnesses. She states the role in noticing the small details is allegorical to the small support role her field conducts in healthcare. She wants this piece to bring awareness to her field because sometimes, the small details make the biggest impact.

Kitty Dough

Kitty Dough is a studio artist, illustrator, graphic and exhibit designer, and metalsmith. Although her 2-D and 3-D work incorporates a wide range of subject, media, and formats, she draws inspiration from her native Outer Banks and always begins with a sketch.

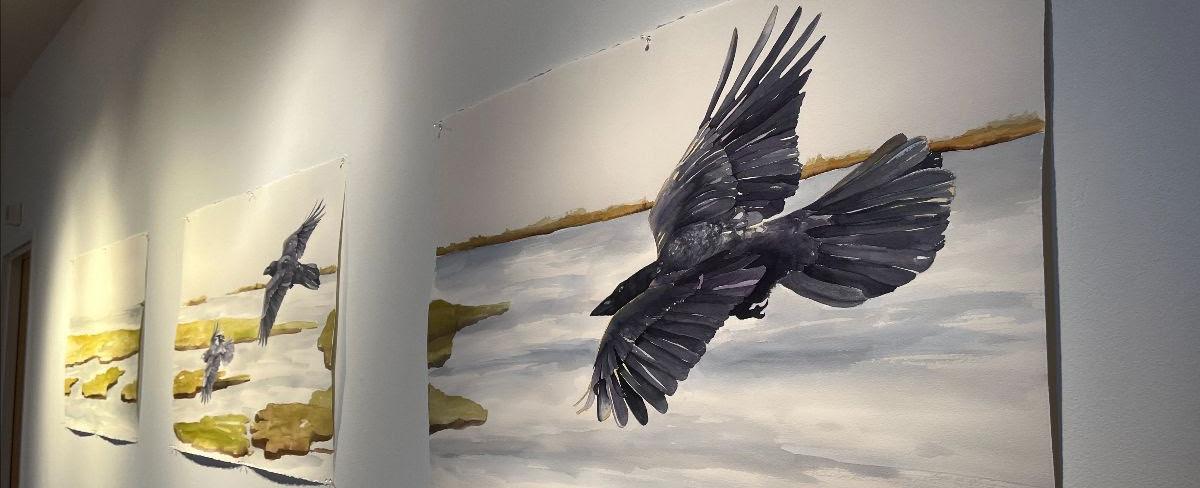

Josefin Engnér

Josefin Engnér is a student at College of The Albemarle. Originally from Östersund, Sweden, she relocated to the Outer Banks in 2024. She has a passion for photography and especially enjoys capturing nature, wildlife, and portraits. Her inspiration comes from spending time outdoors and traveling.

Julia Gabitova

Julia Gabitova graduated in December 2024 from College of The Albemarle with an Associates in Fine Arts in Visual Arts. She often finds inspiration for her art in books, music, and personal experience. Julia often interprets her personal feelings in her art process, which helps to share her story.

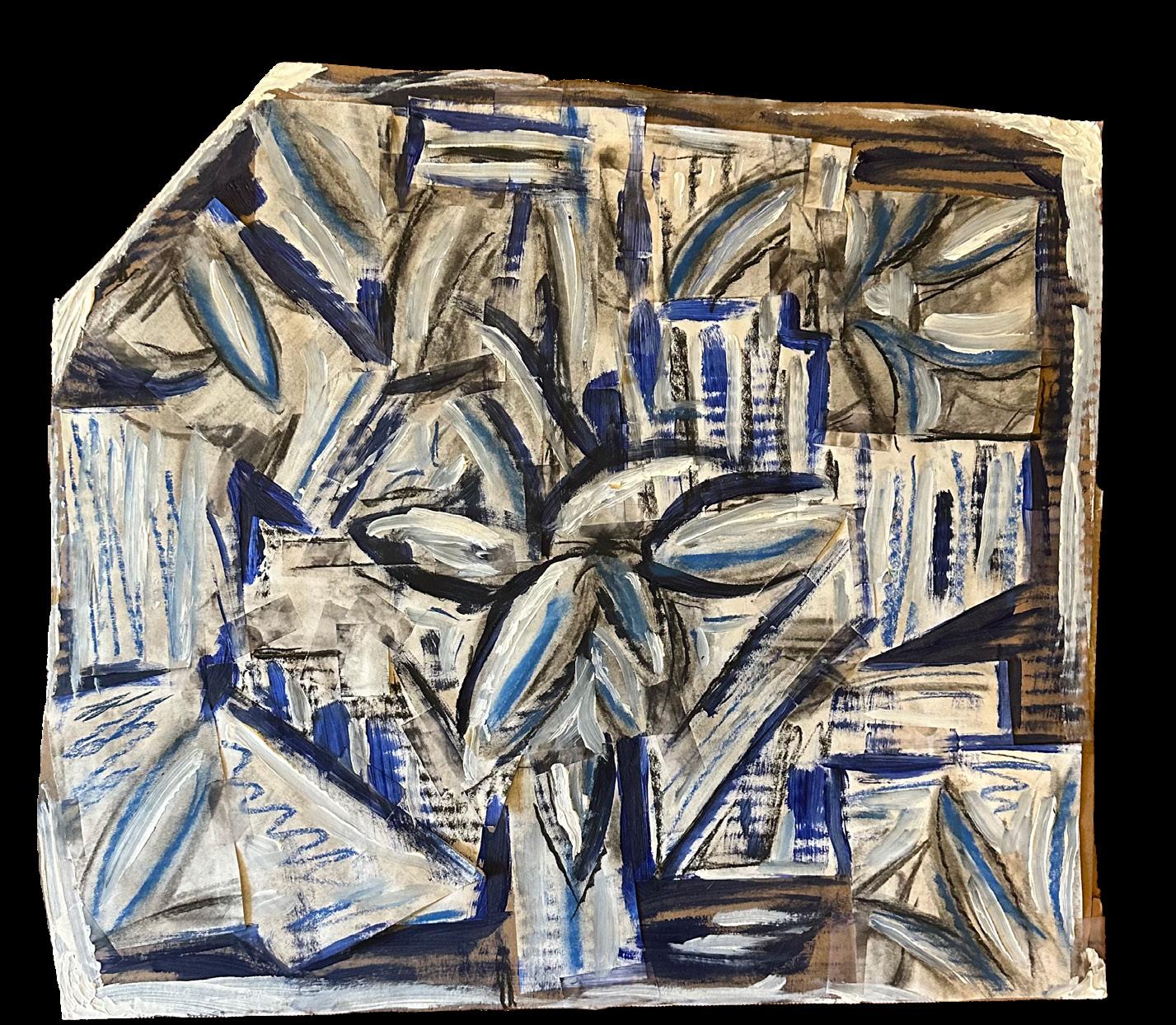

Tara Hall

Tara Hall has been a student at College of The Albemarle for four years, her focus being fine arts in visual arts, and has been influenced with these pieces by European folklore and tapestry work.

Seville Gulmammadova

Seville Gulmammadova is an Azerbaijani visual artist based in Norfolk, Virginia specializing in painting and drawing. Her main themes in art are abstract portraits and figures. She is currently pursuing her Associate in Fine Arts in Visual Arts at College of The Albemarle.

Arthur Mignogna

Arthur Mignogna is a COA - Dare student with a major in Computer Programming and the owner of Stella Arcades. Arthur is former USMC and a Veteran of the Iraq war in a 2005 deployment.

Carolyn Mize

Carolyn Mize was a student in the Professional Jewelry program during its last two years. She started taking classes remotely during the COVID pandemic and continued classes by commuting from Norfolk. She is retired from the corporate world where she used her creativity to implement complex computer systems. Now she is channeling that creativity into lovely art jewelry. Carolyn enjoys working with silver, copper, seaglass, and gemstones. Her current passion is coloring with pencils on copper—a technique introduced in the jewelry classes at COA. Carolyn recently had three pieces of jewelry in the Adorn Exhibit at the d’Art Center in Norfolk.

Kayla O’Brien

Kayla O’Brien is a student at College of The Albemarle currently pursuing her Associates in Fine Arts in Visual Arts. She is planning to earn her bachelor’s and master’s at ODU. She is a comic, digital, and painting artist. Her most favorite medium to work with is mixed media.

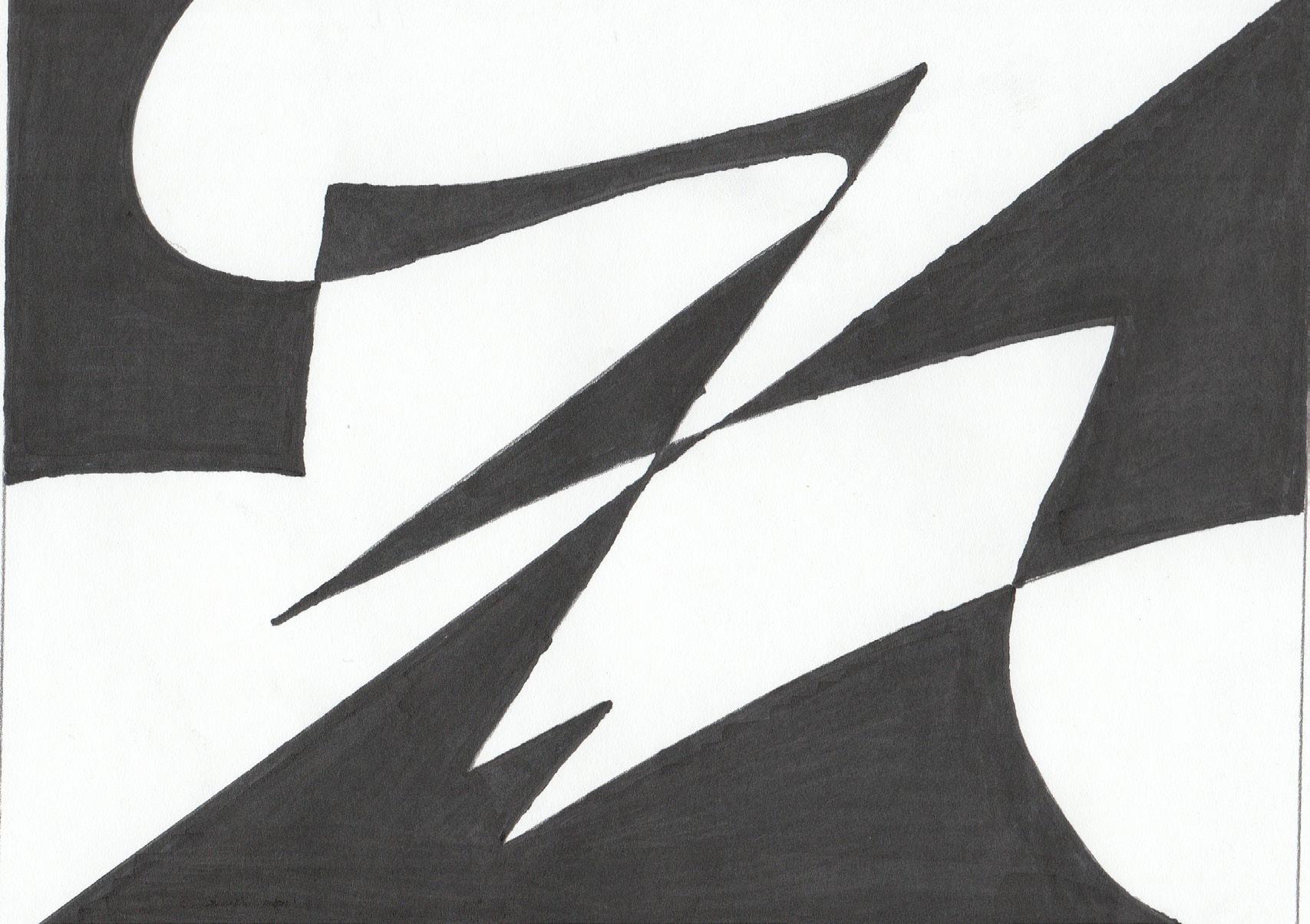

Se’Quan Parker

Se’Quan Parker is an artist residing in Perquimans County, North Carolina, where he is currently working towards earning an Associates Degree for Visual Arts in Fine Arts at College of The Albemarle. He typically specializes in making art traditionally, pulling inspiration from comics, nature, outer space and the mysteries of the unknown. Transferring the ideas of such through the lenses of abstraction and often using colored pencils, charcoal, inks and paint to give his work a tense but vibrant appeal.

Isabella Sanford

Isabella Sanford is a twelth grade homeschool student who is currently working on receiving her Associate of Fine Arts in Visual Arts. After she has completed this degree in the spring of 2025, she plans to continue her education at a fouryear university and receive a bachelor’s degree in animation.

Jamari Smith

Jamari Smith is a student at College of The Albemarle who loves art and dreams of becoming a firefighter. He enjoys his time at COA, especially making friends, including those with disabilities. His passion for art, learning, and building relationships motivates his journey toward achieving his goals.

Dawn Van Ness

Dawn Van Ness was born at Portsmouth Naval Hospital and grew up between Virginia Beach and Skipwith, Virginia, where a deep connection to nature shaped her artistic vision. A largely selftaught artist, her work explores the restorative power of nature, human encroachment, and emotional tensions through expressive color, composition, and experimental techniques.

Emma Vazquetelles

Emma Vazquetelles is an artist and student from coastal NC. Currently enrolled at College of The Albemarle, she creates various artworks, which have impacted her decision to pursue a degree in the visual arts. Despite still trying to find her way in the world, Emma trusts that God has plans for her future.

Visual Arts Jurors

Patrick Berran

Patrick Berran is an artist and educator that lives and works in Kill Devil Hills, NC. He received his BFA at Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA and his MFA from Hunter College, New York, NY. Patrick has exhibited his work both nationally and internationally, recent solo exhibitions include Chapter NY, NY, Dare Arts Vault Gallery, Manteo, NC, White Columns, NY, COA Arts Gallery, Manteo, NC, Hunter Whitfield, London UK, and Reynolds Gallery in Richmond, VA. Recent group exhibitions include The American Academy of Arts and Letters New York, NY, Southampton Art Center, the Hall Art Foundation in Reading, VT, Rod Bianco, Oslo; M+B Gallery, Los Angeles;

Indianapolis Museum of Contemporary Art, Indianapolis; and Gavin Brown’s Enterprise, New York. Patrick has been a visiting artist and guest lecturer at Alfred University, Kent State University and Virginia Commonwealth University. He has completed artist residencies at the Constance Saltonstall Foundation for the Arts in Ithaca, NY, Dial House in Essex, UK, Vermont Studio Center, and the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts in Amherst, VA.

Fay Davis Edwards

Fay Davis Edwards is a painter and multimedia artist from the Outer Banks of NC, whose work centers on the environment and the changing nature of coastlines. She earned her BFA from East Carolina University and her MFA from Maine College of Art & Design. Fay’s home and studio are located on Roanoke Island, which she shares with a variety of critters including a lively flock of chickens and four very opinionated cats.

Tiffany Lindsey

Tiffany Lindsey is an emerging artist living and working on the Outer Banks of North Carolina. Her primary art form is abstract painting and fiber work, although she is known to play with photography and sculpture. Her professional career as Exhibition Director and Gallery Manager at Dare Arts in Manteo, NC, and as a freelance Art Consultant and Advisor helps educate her eye and expand her aesthetic judgments. Recent accomplishments include, solo exhibition 0001, group exhibitions Free Hermit Crab Tomorrow, Which-Craft Art Show, Living Proof, and she has been frequently represented in Estuaries. Tiffany recently completed a commission for the Outer Banks Community Foundation’s permanent collection and has work on permanent display among The Legacy Collective properties.

Christina Lorena Weisner

Christina Lorena Weisner is a visual artist and an Associate Professor in the Department of Humanities and Fine Arts at the College of the Albemarle. She received a Bachelor of Fine Arts (BFA) in Sculpture and Bachelor of Arts (BA) in World Studies from Virginia Commonwealth University (2006) and a Master of Fine Arts (MFA) in Sculpture and Ceramics from University of Texas at Austin (2010). Weisner explores complex relationships between objects, humans, and the natural environment, from the organic to the technological, drawing parallels between the vast and the microscopic, the subjective and the objective.

Elle Everheart

Elle Everheart is a student at Cape Hatteras

Secondary School. She is passionate about animals and spends her time working with horses. Her love for nature defines her character, school, work, and personal connection to everything around her.

Devon Fulcher

Devon Fulcher is a high school freshman. He was born and raised in Portales, New Mexico, and moved to Hatteras Island at the age of thirteen. He has always had a passion for the humanities, anthropology, and history.

Kendra Graham

Kendra Graham is a dual enrollment senior student at Perquimans County High School. She loves writing poetry and short stories, as well as painting and drawing. She is a part of her school’s theatre program and enjoys participating in and supporting all forms of art.

Steven Heritage