COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC MAGAZINE

Editorial EDITOR

Daniel Mahoney

EXECUTIVE EDITOR

Rob Levin

COPY EDITOR

Caitlin Meredith

EDITORIAL ADVICE

John Anderson Dru Colbert

Darron Collins ’92

Jennifer Hughes

Suzanne Morse

Chris Petersen

EDITORIAL CONSULTANT

Jodi Baker

DESIGN

Corey Blake

Z Studio Design

Administration

PRESIDENT Darron Collins ’92

PROVOST

Ken Hill

ASSOCIATE ACADEMIC DEANS

Jamie McKown

Bonnie Tai

DEAN OF ADMISSION

Heather Albert-Knopp ’99

DEAN OF INSTITUTIONAL ADVANCEMENT

Shawn Keeley ’00

DEAN OF ADMINISTRATION

Bear Paul

DEAN OF STUDENT LIFE

Joshua Luce

DIRECTOR OF COMMUNICATIONS

Rob Levin

Board of Trustees

TRUSTEE OFFICERS

Beth Gardiner, Chair

Marthann Samek, Vice Chair

Hank Schmelzer, Vice Chair

Ronald E. Beard, Secretary

Barclay Corbus, Treasurer

TRUSTEE MEMBERS

Cynthia Baker

Timothy Bass

Michael Boland ’94

Joyce Cacho

Alyne Cistone

Barclay Corbus

Sarah Currie-Halpern

Heather Richards Evans

Marie Griffith

Cookie Horner

Nicholas Lapham

Casey Mallinckrodt

Anthony Mazlish

Chandreyee Mitra ’01

Roland Reynolds

Nadia Rosenthal

Laura McGiffert Slover

Laura Z. Stone

Steve Sullens

Claudia Turnbull

LIFE TRUSTEES

Samuel M. Hamill, Jr.

John N. Kelly

William V.P. Newlin

TRUSTEES EMERITI

David Hackett Fischer

William G. Foulke, Jr.

Amy Yeager Geier

George B.E. Hambleton

Elizabeth D. Hodder

Philip B. Kunhardt III ’77

Jay McNally ’84

Philip S.J. Moriarty

Phyllis Anina Moriarty

Cathy Ramsdell

Hamilton Robinson, Jr.

William N. Thorndike

John Wilmerding

EX OFFICIO

Darron Collins ’92

At College of the Atlantic, we envision a world where creativity, presentness, compassion, respect, and diversity of nature and human cultures are highly valued. A world where all people have the opportunity to construct meaningful lives for themselves, gain appreciation of the relationships among all forms of life, and safeguard the heritage of future generations.

COA Magazine is published annually for the College of the Atlantic community.

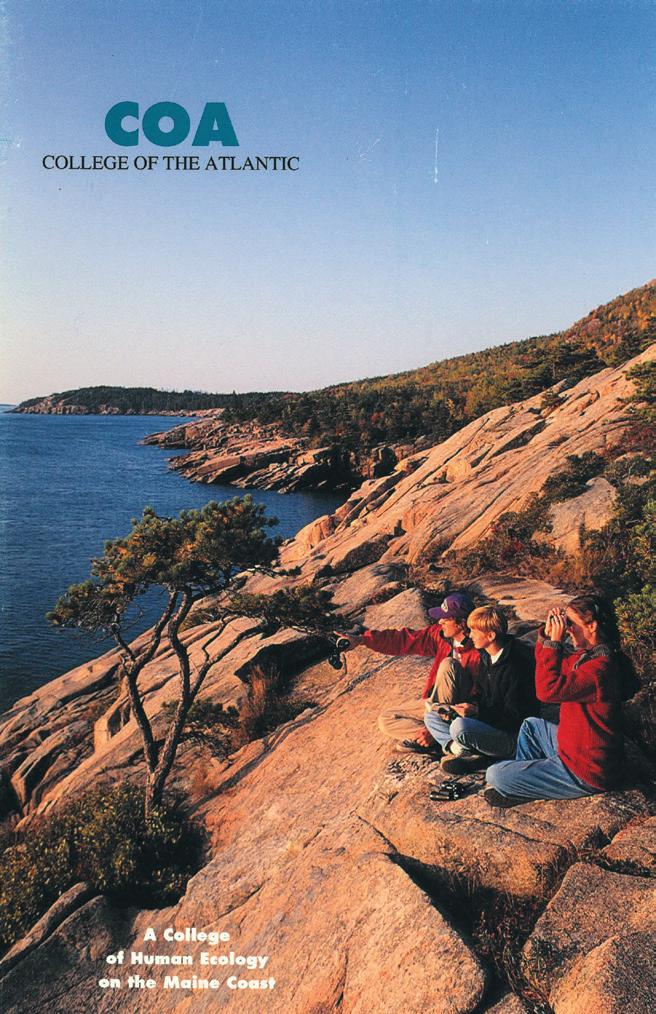

I’MCURIOUS about your thoughts on the cover of this magazine. I can’t get enough of it. Blakeney is a fellow COA alum and I’m therefore wildly biased. But, irrespective of the affiliation of the artist, I find it hard to turn away from that blue Portal among the sky, the rocks, and the sparse vegetation. It also taps into my fascination with Stanley Kubrick and the black, rectangular monolith of 2001: A Space Odyssey. From both, I cannot look away, yet I’m strangely unsettled. In both, I find questions about the future of humanity—maybe that’s the source of the disquiet: moving through that portal, what possibilities might you find on the other side, good or bad?

In this edition of COA Magazine we’ve used that idea—possibilities—as a thread to gather our thoughts, news, and ideas from across the year and from the thousands of people who are part of the College of the Atlantic community. The idea is inherently future-focused and, because we’re embarking on our next long-term strategic plan, the timing is spot on for us. Over the course of this calendar year, we’ll be asking questions steeped in possibility: What can we do differently? What should we do differently?

This kind of strategizing also requires that we think about the ideas and approaches from our history we should be carrying through that portal into our future. Embracing our place is, in my eyes, one such approach, and herein you’ll read about North Woods Ways, COA’s new wilderness outpost in

northern Maine. Conceptually, we have long bathed in the interstices, between disciplinary boundaries and betwixt ridged academic silos. You’ll get a good sense of what that looks like in the world beyond COA in the piece called Keepers of Sheep, featuring entrepreneurial 2018 graduates Arlo Hark and Josie Trople. Finally, although some might conflate human ecology with conservation or environmental science, ours is an expansive curriculum that embraces the arts and humanities with the same vigor we embrace the STEM fields, and you’ll read about that in the news of the Kippy Stroud Artists-in-Residence Program as well as the Supreme Court roundtable discussion, which asks us to consider what might be possible in that institution.

For certain, the most important thing we will collectively carry through that portal and into our institutional future is our commitment to supporting people. We have a unique mission and vision and we cultivate great ideas here. We are blessed with an amazing, inspiring campus and location. But it’s the many incredible people within the COA community who make us our strongest and most creative. More than anything, these pages tell the story of attracting great people, putting them together to work cooperatively on projects, and nourishing their ideas. I’m quite certain that emphasis is what makes our possibilities as breathtaking as they are.

Enjoy,

Darronputs it, “The color of any planetary atmosphere viewed against the black of space and illuminated by a sunlike star will also be blue.” In which case blue is something of an ecstatic accident produced by void and fire.

I love that “ecstatic accident” and think about it on my walk through town to COA. What a double dip of gloriousness to glimpse between houses the blue of the sky and the blue of the ocean converging.

2 News

2 COA Mount Desert Center opens

2 Educator stories sought

3 Energized for change

4 Human ecology in Japan

5 New faces

8 A buggy situation

9 Building a more accessible COA

10 Artists-in-residence program expands

12 Student profile: Linnea Goh ’25

14 Lasting connections

17 Alumnx profile: Hana Keegan ’17

18 Keepers of sheep

WHAT DOES IT MEAN, paraphrasing

Emily Dickinson here, to dwell in possibility? If I’ve learned anything over the last several years, it’s that life can turn chaotic overnight. Those living with disease know this, those living under siege know this, those who must keep their truest selves a secret know this too. If you are old enough to read this magazine, then you too have been dipped into cool pools of chaos and have come out the other side. Congratulations… I mean that. Amid the daily struggle and the large and small disasters that sometimes accompany it, whatever keeps you here a day longer needs to be celebrated. Dwell in that possibility.

When executive editor Rob Levin sent me pictures of Blakeney Sanford’s Portals I knew we had to use one for the cover of this COA Magazine. It was, that day, what kept me here… That blue square in the desert or the blue square on a slated hillside of yellow grasses with a valley oak in the distance, the work spoke about presence, the possibility of transcendence, and the absolute glory of blue. I am reminded here of Maggie Nelson’s book, Bluets, an investigation of all things love and light and blue:

Why is the sky blue? A fair enough question, and one I have learned the answer to several times. Yet every time I try to explain it to someone or remember it to myself, it eludes me. Now I like to remember the question alone, as it reminds me that my mind is essentially a sieve, that I am mortal.

The part I do remember: that the blue of the sky depends on the darkness of empty space behind it. As one optics journal

There are plenty of articles in this year’s magazine to keep you wrapped in the world of possibilities. I hope you enjoy all of them and send us your thoughts.

One of the most informative pieces I’ve had the pleasure of working on for COA Mag is the round table discussion about the history of the Supreme Court. What an immense pleasure it was to sit down with such a smart, generous, committed, and funny group of people. We cannot ignore that possibility also brings with it uncertainty, if not outright fear, for what the future holds. The Supreme Court is badly stacked—what can we do? There are plenty of answers, opinions, and insights in that piece to keep us all motivated for the ongoing fight.

The SCOTUS piece also gave me an opportunity to use Dall·E 2, an OpenAI system that can generate original art. OpenAI made headlines last year for its ability to create content, both visually and verbally. I entered some keywords from the SCOTUS roundtable paired with the words “expressionistic painting” and received the art in the article. It was a fun exercise but one that I will not be repeating for future COA Magazines. I really enjoy commissioning students to make spot art for us. Students make some money, get realworld experience, produce fantastic visuals, and they work. Students do the human work of translating the thing in their heads onto the pages of a magazine. That’s exciting. OpenAI programs are not going anywhere and will continue to upset our placid existences and, hopefully, force us to address what it is we value as a culture. In a New York Times article, illustrator Michael DeForge had this to say about art-generating AI

22 Student profile: Martha Coenen ’26

24 The place of richness

26 Sus ojos brillan rojo en la noche

29 Alumnx profile: Jennifer Prediger ’00

30 Student profile: Raheem Khadour ’25

32 Alumnx profile: Abraham Noe-Hays ’01

33 Let the music play

34 Field ecology almanac

36 How to change the world…

38 The Portals

42 What now / a Supreme Court roundtable

51 Diving into fiction

52 From the archives

54 Alumnx notes

58 Community notes

63 In memoriam

66 Donor profile: Caitlyn Harvey ’02

67 Why I give

programs: “It’s often billed as replacing a job or replacing a person. But usually what happens is it devalues human labor.” At COA we value the human. We value the limitless expanse of human imaginations. We value work. Not to say that using AI programs cannot be fun and entertaining; my son and I create crazy graphics we send back and forth to each other via text. I’m all about fun—and using Dall·E 2 is fun—but supporting art and artists is fun too and, more than just being fun, it is absolutely essential.

Enjoy this issue of the magazine. Abrazos from Bar Harbor. Dan

OF THE ATLANTIC’S new foothold in the town of Mount Desert, featuring both residential and retail space, is up and running at 141 Main Street in the village of Northeast Harbor.

The COA Mount Desert Center comprises living space for 15 students, a staff/faculty apartment, and, at sidewalk level, the new Salt Market, a project of COA alum Maude Kusserow ’15. Salt is an island kitchen collective, Kusserow says, featuring local produce, flowers, and bread, prepared foods and soups, a curated pantry, artisan goods, and specialty coffee drinks made with an authentic Italian La Marzocco espresso machine.

The center, designed by architect and long-time COA collaborator John Gordon to blend in with Northeast Harbor’s Main Street vernacular, is the result of a partnership between COA and MD365, a community-based organization dedicated to promoting long-term economic vitality in

the town of Mount Desert. MD365 owns the land where the building sits, and COA holds a long-term lease with the group. Funding for the project came from COA’s $57 million Broad Reach Capital Campaign.

“When Darron Collins first connected with us in 2017 about having some COA students living in Northeast Harbor, my immediate reaction was YES! Having a cohort of college students and some faculty here could help the town move towards the brighter future we’d like to see,” said MD365 Executive Director Kathy Miller. “This is a village in transition, but it’s still to be determined which way we’ll be heading— into a more vibrant year-round village, or one of increasing darkness, with shops closed and lights out for half the year.”

The building is attuned to COA’s environmental ethos, featuring Gutex brand wood fiberboard insulation, rooftop solar panels, and electric heat pumps for heating and cooling. It also has a super-tight

NEW RESEARCH PROJECT by former COA education program director (1989-2001) Etta Kralovec seeks to explore the stories of alumnx educators.

As a teacher educator, the question of how a COA education shapes the development of future educators has been central to Kralovec’s work since her time at the college. Uncovering their stories is the first step towards uncovering how COA has shaped a generation of educators.

“I know there are many alumnx out there who have become educators, both in formal and informal settings. Many of you have built new schools, led museums, been leaders in online learning, written curriculum, served on local school boards and have led public schools and districts,” Kralovec says. “I’d like to start a conversation with those of you

envelope and heat-capturing ventilation for fresh air. Students living in the space engage with Mount Desert-based organizations in volunteer or internship positions in exchange for reduced rent.

who identify as educators. Hopefully, these conversations will be published in some form and will shape the direction of a larger piece of writing about the college.”

Kralovec, who is professor emerita and the founder of the Borderlands Education Center at University of Arizona, has identified two questions that drive this inquiry. How were COA alumnx shaped as educators by the structure of courses at the college, the governance system, the advising system, internships, senior projects, and the human ecology essay? Secondly, how have the progressive ideas that shaped the college shaped the next generation of educators and their classrooms and learning environments? Please consider reaching out, the more voices the better: endhomework@ gmail.com.

Etta Kralovec.AHOST OF ENERGY SYSTEM

IMPROVEMENTS are occurring across campus as College of the Atlantic strives to meet its ambitious fossil fuelfree goals. Supported by funding from the college’s recent Broad Reach Capital Campaign, new grants, and federal and state energy programs, COA is moving step by step towards a net-zero campus.

Director of Energy David Gibson has spearheaded the charge to power the college as much as possible with renewable sources. Proper weatherization of many older buildings has been an important part of that effort. Last fall, Gibson secured a donation to purchase a cellulose insulation blower, which he has been training students to use in attics and walls. Concurrently, the Campus Committee for Sustainability (CCS) updated the COA Energy Framework by creating the COA Energy Policy, which enshrines the school’s goal to be fossil fuelfree by 2030. The policy was passed by All College Meeting in November 2022.

Students have been front and center in the efforts to move COA to a fossil fuel-free campus, whether through committee work, insulating and waterproofing buildings,

or calculating residential energy needs. Renovations to campus buildings, on- and off-campus housing, and COA farm facilities have saved thousands of gallons of heating fuel annually while providing a range of learning opportunities.

“A lot of the science showing when we need to make these changes in order to sustain a livable earth states that they need to happen by 2030, but then if you look at a lot of larger-scale policies, they aim to be there by 2050. So I think that it’s really important that COA, as a school that has such strong values in sustainability, is a leading example in fossil fuel reduction,” says CCS co-chair Linnea Goh ’25. “This goal is also directly aligned with the goal that Bar Harbor has in their Climate Action Plan of achieving 100% renewable energy sourcing by 2030.”

Clean electricity lies at the center of COA’s efforts to move away from fossil fuels. In 2022, the school signed a 20-year contract with ReVision Energy to provide nearly 100% of COA’s electricity from a new solar field being installed just up the road in Hampden. The college is now using electricity for more and more of its heating, cooling, and hot water needs in the form of heat pumps. For

the uninitiated, heat pumps are electric devices that can heat or cool a building by transferring thermal energy from outside air using the refrigeration cycle.

Heat pumps are now in place in the buildings and grounds headquarters, Studios 5 and 6, Cottage House, Carriage House, Peach House, Witchcliff apartments, and Witchcliff academic building. Gibson has also overseen installation of heat pump water heaters in many of these locations, along with the Arts and Science Building, Davis International Center, and The Turrets, while preparations have been made in Kaelber Hall for pre-heat to the oil-fired hot water heater for the Take-a-Break kitchen.

COA participated in an Efficiency Maine pilot program for commercial split system heat pump water heaters for Blair Tyson residences. This project was led by Ridgeline Energy Analytics, who had a complete domestic hot water system designed and engineered. The system completely removes the domestic hot water from the oil boiler system, saving around 2,000 gallons of oil per year, while demonstrating the viability of the technology for other facilities across the state.

“Even though it’s not as visible as some other projects we are working on, being able to source and heat our buildings with local electricity is leading the way towards a more sustainable way of having a house, while also teaching people how to live sustainably,” Goh says.

Over the 2022/23 winter break, five students worked with Gibson on insulation projects on campus. They installed a full vapor barrier in the Turrets basement and removed old drywall, damaged fiberglass insulation, and rotten wall studs. The space was then fully insulated with three inches (R21) of spray foam, and is predicted to save around 1,000 gallons of heating oil each year, improve air quality in the building, and make the basement a more usable space.

Also on campus, Gibson and his crew

installed nearly fifty 1.5 gallon-per-minute, low-flow showerheads throughout campus. This project, which students have informally reported has created a better shower experience along with being more environmentally friendly, is predicted to save around 250,000 gallons of water and 1,000 gallons of heating oil every year.

Energy improvements have also been afoot at off-campus properties. A dozen residential properties the college purchased in downtown Bar Harbor last year have been taken off fossil fuels entirely. The homes were air sealed and insulated, heat pumps for heating and cooling, and heat pump water heaters were installed in each building. All six apartments next door to the college that came online a few years ago were also air sealed, insulated, and equipped with heat pumps. All 18

COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC has a new affiliate school, the Setouchi Global Academy, located in Osakikamijima, Japan.

Setouchi Global Academy is a one-year program focused in interdisciplinary human ecology. Similar to COA, Setouchi is also a tiny institution located on an island that highlights place-based learning and ecologically reciprocal relationships to the surrounding environment. Drawing inspiration from College of the Atlantic and Ashoka, both of which have been educating and supporting social innovators for decades, Setouchi aims to present an alternative to the Japanese model of lecturing and compartmentalization, and help usher in an age of educational reform.

“I have been working for the betterment of Japanese higher education for many years and, after learning about COA, I am trying to make a fundamental educational model in Japan to let people know that education is not just paper work done in the classroom, but in an environment full of nature,” said Hiromi Nagao, founder and president of Setouchi Global Academy, professor of socio-lingusitics, and previous president of Hiroshima Christian Women’s College.

“Students need to touch the soil and live with nature.”

Setouchi Global Academy, in collaboration with COA, held its inaugural courses in July of 2016 for the Human Ecology Lab & Island Odyssey (HELIO) summer institute. In 2020, the first year-round student enrolled in Setouchi. Since then, there have been eight students, three of which have come to COA to complete their degrees.

properties were further set up with low-flow showerheads and LED lightbulbs by Ben Pannullo ’22.

Finally, a whole-house ducted heat pump system was installed at the farmhouse at COA Beech Hill Farm through an Efficiency Maine pilot program. The farmhouse there and the house at COA Peggy Rockefeller Farm were also super insulated and are now completely off of fossil fuels.

As of this writing, Gibson is working on securing $150,000 in funding to lead a professional development workshop focused on hands-on energy efficiency education for middle and high school teachers in the summer of 2023. This will include providing the teachers with all of the tools and materials needed to implement the lessons in their classrooms.

Students who attend Setouchi can come to COA as second-year students and then receive a COA degree. COA students are also offered opportunities to fly to Japan to study at Setouchi for residencies, senior projects, and monster courses. This collaboration has brought and will continue to bring many new, exciting, unique, and inspirational educational opportunities to both Setouchi Global Academy and College of the Atlantic.

COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC is pleased to welcome Roland Reynolds to the COA Board of Trustees. Reynolds is a senior managing director at Industry Ventures, where he has spent the past 13 years helping build their venture capital platform. Today, the organization has over $5 billion in assets, which they invest on behalf of pension funds, endowments, foundations, and families.

Reynolds serves on the governing board of the National Cathedral School in Washington, DC, from which his daughter, India, graduated in 2020. He has previously served on the board of trustees of the Groton School, as well as on the foundation board of a community college in Richmond, Virginia, where he was born and raised.

After graduating from Groton, Reynolds attended Princeton University. After college, he worked for JP Morgan’s investment banking division in New York for several years before attending Harvard Business School. Upon graduation he entered the venture capital business, soon founding a venture capital fund of funds before merging with Industry Ventures in 2009.

Reynolds is excited to serve an active role in stewarding COA’s unique, interdisciplinary, experiential approach to education, he says.

WILLOW GIBSON Financial aid assistant

KELLY DICKSON MPHIL ’97

Grant writer

JASON FORD Coordinator of international student services

REGAN GREER ’22 Assistant director of buildings, grounds, and campus safety

“Over the past 50 years, COA has emerged a leader in American higher education with its unique focus on human ecology,” Reynolds says. “The COA experience is transformational, not only for students, but for the broader community of Mount Desert Island, and I am grateful to join an extraordinary group of trustees to help steward COA for the next 50 years and beyond.”

Reynolds first came to Mount Desert Island with his future wife in the summer of 1997 to stay with her family in their summer house in Southwest Harbor. The pair were married at St. Mary’s by the Sea in Northeast Harbor in August 2000. They are members of the Causeway Club in Southwest Harbor and the Pot & Kettle Club in Bar Harbor.

“25 years after first coming to MDI, it is hard for me to remember a time when the restorative power, intergenerational connection, and extraordinary beauty of Acadia National Park were not an integral part of my life,” Reynolds says.

Reynolds and his wife, Diana (Buchanan) Reynolds, have lived in Alexandria, Virginia for more than 20 years. Their daughter, India, is a junior at Hamilton College in Clinton, New York and their son, Samuel, will be joining his sister at Hamilton next year.

KATIE HODGKINS ’16 Conferences and events coordinator

KELLIE HOFFART Assistant registrar

LOTHAR HOLZKE ’16 Academic services administrator

STEVE LAMBERT Buildings and grounds associate

JOSHUA LUCE Dean of student life

JOSH MILLER Lead groundskeeper

KATHLEEN MULLIGAN Day cook

SAFFRONIA DOWNING , an artist whose work reflects the histories of land and the relationship between people and the environment, is a teaching fellow joining the College of the Atlantic community for the academic year. Her work revolves primarily around clay, and she is teaching courses focused on the study of ecology, art, and ceramics.

“I am really excited by the whole concept of an education based around human ecology, and how people fit into systems, especially because my practice is all about looking at systems and tracing them through different cultural and natural permutations,” she said. “So COA feels like a really good fit for the kind of teaching that I want to do.”

Downing works with wild clay to map material residues across time and place, foraging local material to create site-specific installations and sculptures. She is the co-creator of the digital publication Viral Ecologies, “a multipronged investigation of emergence.”

“I’m really interested in helping artists realize the processes behind their art practices, and to start to investigate and broaden those processes, and to see that as part of the art itself. It’s not just what goes on the pedestal,

but it’s the whole process of what made that work,” she said. “Looking at it like that can offer a lot of new ways to engage with the materials and concepts you’re working with.”

COA’s teaching fellow program is intended to broaden students’ horizons by bringing educators from across the spectrum of approaches and practices to campus. Downing’s inclusion in the program is a great example of this, said COA Allan Stone Chair in the Visual Arts Catherine Clinger.

“Saffronia is excellent, exciting, and offers a departure from previous offerings by bringing humanecological insights from having practiced in different places with varied approaches,” Clinger said.

Downing holds an MFA degree in ceramics from the Art Institute of Chicago and a BA in studio art from Hampshire College. She taught the course Knowledge Lab: Craft Ecologies in the sculpture department at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Downing is the recipient of awards and residencies such as the Oxbow School of Art Fellowship, ACRE Residency, and Salem Art Works Studio Artist Residency. She recently completed a year-long residential fellowship at the Lunder Institute For American Art at Colby College.

Her work has been featured in publications such as Sixty Inches From Center, Newcity, LVL3, and Number. Her work was recently featured in exhibitions at Roots and Culture Contemporary Art Center (Chicago, Illinois), Bad Water (Knoxville, Tennessee), Resort (Baltimore, Maryland), and The Franklin (Chicago, Illinois).

Downing said she is excited to meet others who are thinking about and working within the intersection of art and natural science. “I’m also excited to explore the park. I’m trying to hike as many mountains as I can. It’s my first time living near the ocean—it’s really cool,” she said.

In her free time, Downing likes to cook. “I have a farm share at COA Beech Hill Farm, so I’ve been enjoying trying really hard to use up all my vegetables,” she laughs.

I’m really interested in helping artists realize the processes behind their art practices, and to start to investigate and broaden those processes.

THECOLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC COMMUNITY is excited to welcome Laurie Baker as a new faculty member in computer science. With her rich academic background and her experience working with statisticians and data scientists from across the globe, Baker brings new perspectives and innovative approaches to this important field.

Baker, who was drawn to COA’s self-directed, interdisciplinary program, said she is looking forward to expanding course offerings in computer science and to collaborating with and learning from students here.

“One of the things I find really exciting about computer science and data science is that they can touch so many different fields,” Baker said. “I love the breadth of what’s possible to do in data science and in computer science, and I really like the ways that student interests extend my own learning into other topic areas that I haven’t looked at or thought about before.”

Baker is a disease ecologist and marine biologist by training, with a keen interest in programming, data science, and the use of novel data sources in research. Her work focuses on understanding how dynamics change over time and space in human and natural systems, including how diseases spread, how animals move, and how fish populations are managed. She uses special tools and techniques from the field of data science to study these patterns and to see how different interventions and policy decisions can affect them.

“One of the courses that I’m really excited about is teaching a community-engaged data science class that works with regional partners on data science questions. These projects can give students really valuable experience in applying data science techniques to local problems and working in partnership with organizations to understand local needs and to exchange knowledge. These projects also present great opportunities for students to connect with the community around them,” she says.

Baker reflects all the best of what is happening in computer science, said COA provost Ken Hill.

“Dr. Baker’s research is action-oriented, her teaching is inspiring, and her commitment to social justice is sound,” Hill said. “Her cutting-edge work on disease ecology fits very well into the broader frame of human ecology. We’re so happy to have her teaching here at COA.”

Baker holds a PhD in ecology and evolution from University of Glasgow, an MSc in marine biology from Dalhousie University, and a BSc in marine biology from the University of St. Andrews. She has held positions as a visiting assistant professor of digital and computational studies at Bates College, head of faculty and data science lecturer in the UK at the Data Science Campus at the Office for National Statistics, and Medical Research Council fellow at University of Glasgow. She has also spent time as a visiting researcher at the Universidade Federal do Paraná in Curitiba, Brazil, King Abdullah University of Science and Technology in Thuwal, Saudi Arabia, the Norwegian University of Science and Technology in Trondheim, Norway, and the Instituto de Fomento Pesquero in Valparaíso, Chile.

Baker has authored a number of papers about her research on rabies, gray seals, fisheries, and pulmonary arterial hypertension in journals including PLOS One, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, Movement Ecology, Environmental Biology of Fishes, and the American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine.

When she isn’t working behind a computer, Baker is an enthusiast of all things outdoors.

“I love hiking, sailing, and biking, and playing sports like soccer and ultimate. I am working on becoming a better skater—I’ve got a pair of Nordic skates that your Nordic ski boots can clip into. They are great for going out on rougher ice, I’m hoping to explore some more of the frozen ponds and lakes in the area,” she said, “I also really enjoy learning languages, I have been practicing Spanish, Italian, and Portuguese over the years, and I’m looking forward to continuing with that.”

ABUSTLING WORLD that’s typically hidden away is the focus of a sculpture newly adorning the front of the George B. Dorr Museum of Natural History. Saproxylic Food Web, by Robert Haskell MPhil ’22, showcases in bright, shiny colors some of the thousands of creatures that inhabit the ecosystems around decaying trees.

“The sculpture is designed to educate people about dead wood and the vast array of creatures that all live on dead wood and depend on dead wood for their survival,” Haskell says. “These are teeny, tiny, crawly things that no one will ever see, so, I’m bringing them out in the open and making them big and colorful.”

The Saproxylic Food Web, Haskell’s thesis for his MPhil degree, details 120 larger-than-life metal bugs circling the wide trunk of a dead red pine that was otherwise destined for the wood chipper. The tree is stabilized by a hidden steel beam anchored to a buried, three-foot concrete footer, which also holds the hundreds of feet of solid COR-TEN steel circling the tree. Haskell estimates the metal infrastructure weighs 4,000-5,000 pounds, and says it is designed to outlast the decaying tree.

“People destroy dead wood wherever they see it, but really it’s the fundamental building block of this hugely important ecosystem. Saving this tree by making a sculpture that will hold it up is really important to the piece.”

Haskell came to COA for a master’s degree after earning a BFA in sculpture from The University of the Arts in Philadelphia. His self-directed path at COA gave him the opportunity to incorporate ecology and science into his artwork in thoughtful and novel ways, he says.

“I spent my time here melding my metalworking and other sculptural practices with biology and ecology and all these different science classes,” he says. “I got to personally work with the professors to see how this knowledge intersects with the sculptures I’m making and how can I really meld them together into something that’s more than the sum of its parts.”

WHILE ROBERT HASKELL’S WORK is busy illuminating the hidden ecosystem in front of the Museum, the facility is also buoyed as of late by an elegant, accessible route of entry thanks to the thoughtful work of Lauren Brady ’21. Brady’s senior project, Bringing the Dorr Museum Entrances into ADA Compliance: From Development to Implementation of a Landscape Architecture Design, addressed an access problem that had been with the museum since its opening, while framing the landscape with artful stonework and native plantings.

Brady was first introduced to the need for an accessible entrance, and pathway to the back door of the museum, in the Landscape Architecture Studio Class, and as she thought more about the problem she realized she could help address it by making it the focus of her senior project. She engaged closely with museum stakeholders, worked collaboratively with the relevant COA governance committees, drafted design options and, with community support, moved a final design into construction drawings, materials estimates, and site permitting. COA President Darron Collins ’92 was taken with the project and began seeking support right away.

“Darron showed an immediate desire to push the plans forward despite their unapproved and early-process character, and began pursuing leads for donors,” Brady wrote in her senior project papers. “By the final week of fall term, to my shock, and to the pleased surprise of

committee members, the president had raised $25,000 from an anonymous donor.”

After the Dorr Museum was opened about 25 years ago, the landscape was never completed and a temporary wooden ramp and gravel path became the front entryway, Brady notes in her senior project. This front entrance was not in compliance with the Americans with Disabilities Act because it is too steep. In addition, the rear entrance had no formal path to it, despite the fact that for most of the year it is the primary entrance and exit used daily to access classes and staff offices.

“Making the museum entrances accessible is critical,” Brady wrote. “The Dorr Museum is the public face of the college, hosting 12,000-14,000 people annually. Those visitors range from summer tourists to educational programs, and they frequently have no other tie to or experience of the campus.”

“As I reflect on this project, I am thinking about landscape architecture as a form of facilitation, first among people and their various needs and wants; in this case I learned a lot about how the museum hosts visitors and how things change within the institution of COA,” Brady wrote. “I also think about this role as facilitating relationships between the land itself and the people who live on it. Beyond the straightforward need for accessibility, I hope this landscape will create new space for community events, and invite people to engage with our native ecosystems.”

The COA Dorr Museum of Natural History has a beautiful, accessible entrance thanks to the work of Lauren Brady ’21. By Rob Levin

By Rob Levin

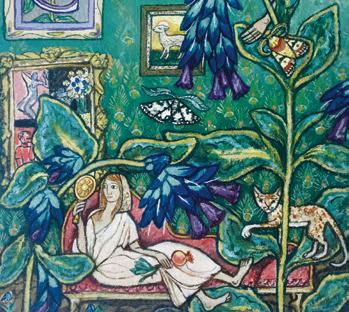

AFTERTHREE YEARS of bringing working artists to campus, the College of the Atlantic Kippy Stroud Artists-in-residence program has been permanently endowed and is set to expand. Thanks to a $1.14 million grant from the Marion Boulton “Kippy” Stroud Foundation (MBSF), the program will be funded in perpetuity and grow from an established early fall residency into the academic year.

“Connecting with art can show us that culture is continuously produced and is not locked into narrow timeframes that freeze moments and peoples—rather it reforms, rebuilds, and rejuvenates worlds and world views,” says COA Allan Stone Chair in the Visual Arts Catherine Clinger, who has led development of the program. “The artists who visit COA and Mount Desert Island as part of this program can help us enter into conversation with culture and nature in ways that can nourish our spirits as a broadened learning community.”

As part of the endowment agreement, the established month-long fall residency program will continue as it has in 2019, 2021, and 2022, while two new programs, the Kippy Stroud Emerging Visiting Maine Artist(s) and the The Kippy Stroud Memorial COA Lecture will further add to the offerings. The two-week visitor program will allow a Maine artist, chosen by COA arts faculty, to contribute directly to the studio classroom as a collaborative shared space, incorporating the program into a COA arts course in the late winter or early spring term in context with COA’s core human-ecological field of study. The public lecture, set for late May each year, honor’s Stroud’s original Acadia Summer Arts Program in Bar Harbor, which included several lectures per week. Lecturers will be selected from three nominations from COA and three candidates identified by the MBSF board.

“The much-amplified COA Kippy Stroud Artists-in-Residence Program will perpetuate the vision and spirit of Kippy’s commitment to generous hospitality, creativity, artistic achievement, and bringing artists together with time to relax, foment new ideas, and be inspired by the natural splendor of MDI,” says Stroud foundation board member Patterson Sims. “This program powerfully builds upon the legacy of Kippy’s legendary Acadia Summer Arts Program, familiarly known as Kamp Kippy, and her role as the founder, director, and funder of the Fabric Workshop and Museum in Philadelphia, along with her family’s deep, multi-generational attachment to Mount Desert Island.”

The creation, expansion, and endowment of the program would not have been possible without Clinger’s work, said COA Dean of Institutional Advancement Shawn Keeley ’00.

“I want to thank Catherine for her vision for the program, management of the first several years, and excellent stewardship of the relationship with the foundation, which has led us to this point.

BRAVA CATHERINE!!” he wrote in a recent email to the COA community. “This program will not only bring wonderful opportunities to our students, faculty, and staff in the years to come, but it will also further establish COA as a center of gravity for the arts here on MDI and in Maine.”

Stroud was a talented artist, teacher, generous philanthropist, and impassioned promoter of contemporary art and artists. Starting in 1977, she founded, funded, and directed The Fabric Workshop and Museum in Philadelphia, an experimental program for artists working in textiles and many other media. On MDI, where she spent summers, she oversaw and funded the Acadia Summer Arts Program (ASAP), or as it was affectionately known, “Kamp Kippy.” For almost three decades ASAP hosted hundreds of artists with their guests and families.

Kamp Kippy, in the words of the scholar and curator Debra Bricker Balkan, “represented a high-octane salon, an exhilarating retreat where ideas were exchanged over dinner, before lectures, and on boat trips, walks, and off nights with fellow guests…

ASAP was the outgrowth of her phenomenal largess, of her desire to bring extraordinary people together.” Kippy passed away in 2015 and her foundation is committed to carrying her passion for art forward.

“W HAT WOULD BE YOUR IDEAL college experience?” A friend asked me this question a couple months before I applied for college. I described my dream university experience as an intimate school community

situated by the ocean with small class sizes, hands-on, place-based learning, and a focus on both marine biology and sustainable development. Smiling, he told me about College of the Atlantic. Intrigued, I immediately began

researching COA and fell in love with the school. Although you can never quite tell what a place will be like from websites and brochures, COA has been everything I was looking for and more.

Silt, coarse gravel, cobble, boulder. As an outsider, you might have wondered why the 15 students of earth science professor Sarah Hall’s Watersheds class were zigzagging across a stream, picking up every rock at the toe of their boots. By measuring rocks, we were able to learn about the effects of erosion and sedimentation on the composition of Breakneck Brook. During this class, we learned many techniques to monitor streams, but my favorite data collection days always involved standing hip deep in water as the stream flowed past me. At the end of the course, we synthesized this data to create a report for Acadia National Park. I particularly enjoyed this class, and I learned concrete, field-based skills while simultaneously getting to know the watersheds of MDI. This helped me feel more connected to the place I now call home.

Waking up at 6:30 in the morning to trudge across a mud flat is not the first thing that came to mind when I was thinking about college, but it was definitely a highlight of my Marine Ecology class. On this one early Tuesday morning, ecology and biology professor Chris Petersen picked me up to drive to Otter Creek. As we wandered down to the flat dressed in waders and carrying wooden frames stapled to mesh sheets, the sulfuric smell of mud woke me up with its pungent odor. Although we were there to install the recruitment boxes to measure predation on clams, I probably spent more time trying to figure out how to walk in mud. Coming back to campus completely drenched in sludge was a highlight of my term and made me feel rejuvenated.

DEPT/ID COURSE NAME

ES 5045 Marine Ecology

ES 3085 Watersheds

ES 10762 Polar Ecology and Exploration

Monday/Thursday Petersen, Chris

Monday/Thursday Hall, Sarah

Todd, Sean

Monday/Thursday

1

1 1

A FOGGY SUMMER MORNING as the tide rolled in and the smell of salt wafted through the air, we examined garlic-scented sea stars, barnacles the size of cups, and bright orange sea cucumbers. For my internship I was a kayak guide in Haida Gwaii, an archipelago off the West Coast of Canada. One of my favorite aspects of kayak guiding was having the opportunity to share my excitement and care for the ocean.

While backpacking on a seemingly pristine beach on Vancouver Island, I discovered broken laundry baskets nestled between logs, fragments of microplastics scattered throughout the sand, and even a buoy from Singapore. That moment was when I became concerned about humans’ environmental impacts on remote locations. When marine sciences professor Sean Todd asked me to write an eight-page essay on any topic related to the Arctic or Antarctica for his class, Polar Ecology and Exploration, I decided to use this opportunity to dive deep into my passion for microplastic pollution. At first, the length of the essay seemed daunting, but once I started researching, I couldn’t stop. Time flew by and mealtimes slipped past as I sat in the computer lab sifting through paper after paper on different aspects of microplastics in the polar regions. What scared me the most was a study I read disclosing the presence of microplastics on the Byers Peninsula, one of the least-visited places on the planet. This got me thinking; if there’s plastic in desolate locations of Antarctica, do areas of untouched wilderness even exist? Although the research project raised more questions than it answered, it inspired me to continue searching for and creating solutions and answers as I continue with my time at COA and beyond.

By Jeremy Powers ’24

By Jeremy Powers ’24

It’s the cold that wakes you up, and it’s the achy pinch of the wood plank floor that keeps you from going back to sleep. The room is silent, save for the occasional rustle, and it seems that even the birch bark canoes, hanging on the wall, slumber still in the glow of the early-morning sun. You sit up, disentangle yourself from your sleeping bag, and quietly shuffle your way through a minefield of sleeping forms and slumbering shapes.

The door to the lodge squeaks a little, so you open it ever so slowly, and for a moment you stand on the porch and marvel at the glory of winter in the far north— wind-carved snowdrifts sparkling in the sun, icy arctic fingers pinching your nose and your ears, the bonedeep silence blanketing everything in a curious, intangible feeling.

Your chattering teeth remind you to go back inside, and the woodstove greets you warmly as you enter, inviting you to pick out a book from the pine-clad wall on the right. You oblige, and throw your eyes across titles that tell tales of grueling expeditions north, others that describe the land and who was here before us, and at least one that tells you how to build a sauna.

FOR DECADES, Alexandra Conover Bennett ’77 and Garrett Conover ’78 used this lodge as a base for their Registered Maine Guide business, North Woods Ways. Here, they taught and practiced traditional skills in the North Woods of Maine, and provided long distance backcountry expeditions to people from all across the world. For at least 25 years, College of the Atlantic classes have been visiting and using the property for coursework, recreation, and outdoor leadership training and adventure. Now, as Conover and Conover Bennett prepare to retire, ownership of North Woods Ways is transferring to College of the Atlantic, under whose supervision it will continue as a premier resource for experiential learning in the outdoors.

“We had an approach and a uniqueness and a way of doing things, but we are not interested in cloning that in whoever comes next,” Conover says of the property, and their way of life there. “We want people to accept things that are useful, modify what’s different now, keep it flexible and evolving and growing, for the needs of whoever is currently keeping those flames. I think there is a tendency for some places to preserve the exactness of something, and I don’t think that’s necessarily good or smart.”

Conover and Conover Bennett founded North Woods Ways together in 1980, and over their 27-year career they made a lasting name for themselves with their traditional approach to traveling through untrammeled wild places. They specialize in using woodcanvas canoes and handmade wooden paddles for summer

travel, and they have mastered the use of traditional ash/rawhide snowshoes, handmade toboggans, and wood-heated canvas tents for the winter. Often traveling hundreds of miles in the span of a few weeks, their expeditions attracted people from all around the world, and their techniques garnered widespread attention.

“We just kind of followed our passion and we became known for using traditional classic skills to travel in the North Woods… and we just suddenly realized that everybody else wasn’t that way, so all the journalists came flocking to us,” Conover Bennett laughs. “We didn’t ask for the attention.”

The purchase of the property was made possible by a generous donation from the Cornelia Cogswell Rossi Foundation, an organization dedicated to community needs such as healthcare, education, and environmental conservation. The main structure at the property will be renamed the Rossi Lodge in honor of the gift.

Anne Green, a Rossi Foundation board member, said she was inspired by the potential that the property has for COA and others. “We loved the concept of a winter academic basecamp, and the year-round educational component and platform for engaging surrounding schools,” Green says. “The collection of wilderness equipment, tools, and books represent a rich cultural history of the North Woods that will provide additional knowledge and learning opportunities for students.”

COA began using North Woods Ways decades ago for field trips

for courses like Winter Ecology and as a training ground for the outdoor leadership program. The relationship evolved organically over the years and COA students have long been welcome guests on the property, Conover Bennett says.

“We maintained this connection with the college, just naturally, we didn’t go out of our way, it wasn’t any plan; it’s just that these were human beings that we were really fond of,” she says.

One of the most remarkable things about this moment, as the property transfers into the college’s hands, is how reciprocal the relationship has been and continues to be, Conover says.

“The college thinks we’re the legacy people, and treats us as such, but we’re saying, No, no, no… COA is the legacy. And we each think the other is the better entity of the bunch,” he says. “To me, that just speaks well of all of us.”

As part of the property transfer, Conover and Conover Bennett are donating a considerable amount of outdoor gear, including tents, axes, skis, toboggans, canoes, and other assorted camping gear.

“We’ve had so many completely generous mentors and donors and friends who’ve contributed to our venture here in all sorts of ways, and it’s just the fabric of the tradition that we are happy to contribute to,” Conover says.

Aside from being world-renowned wilderness experts and travelers, Conover and Conover Bennett both enjoy getting creative in their free time, something that has helped fill the long, dark, cold winter nights in the north country.

“Music is probably my strongest passion. I think for a few decades now, I’ve been playing at this Finnish Farmer’s Club, playing this traditional 1920’s Finnish dance music,” Conover Bennett says. “And I would say the other thing is picking walks in the woods at my own pace, not being distracted by guiding, and getting to look at stuff, study stuff, discovering freshwater jellyfish, and do some natural studies on my own.”

Conover, for his part, continues to write and hone his photography skills. “It’s all related, it all circles back to northern cultures and skill groupings and stuff that’s always fueled me, but it’s fun to be in a place now where the pace isn’t so dependent on making a living from it. In some ways it’s more fun, I can just do exactly what the primary obsessions are, the goals and interests,” he says.

Both say that welcoming so many COA community members to North Woods Ways over the years has been an inspirational, rewarding, and essential part of their adventure, and knowing that the property will continue to grow and evolve under COA’s leadership is reassuring.

“Working with COA students means so much to me,” Conover Bennett says. “Having students pitch in and help with little things here and there, eating together and hanging out, listening to them, what they talk about, think about, wonder about… their questions are just remarkable, and that just means an enormity to me.”

Conover nods in agreement. “It’s the fire that’s important,” he adds. “The fuel can change a little bit, but the fire has to keep going.”

Alexandra Conover Bennett ’77 encounters a moose while paddling a traditional birch bark canoe in the waters of northern Maine.HANA KEEGAN’S COA JOURNEY

began at the back of a crowded lecture hall at a sprawling university in London. Keegan, who graduated in 2017, remembers the moment she knew she needed a more hands-on approach. “I found my way to COA by trying the polar opposite first,” she jokes. “I was sitting with 400 other students in a lecture on economics and scrolling through COA’s website. I remember thinking, Wow, these students get to go kayaking!”

The academic flexibility and small size of the college also appealed to Keegan, who grew up on the 13-mile long Tortola Island in the British Virgin Islands and was homeschooled until late high school. Initially, she focused on climate politics, gravitating towards Doreen Stabinsky’s classes and the climate justice advocacy of the student-run Earth In Brackets. “The climate policy track was a big pull for me when I was considering COA,” she says. “But I also remember emailing [Joanne Woodward and Paul Newman Chair in Performing Arts] Jodi Baker before I even arrived asking her if I could be in her Play Production course.”

Keegan decided on other classes that first semester, but theater was never far from

her imagination. When she finally took the plunge—signing on as an actor and dramaturg for the 2016 COA production of The Sneeze, a vaudevillian collection of Chekhov shorts—she knew she’d found her place. “It was the happiest I ever felt at COA,” she recalls.

Building on what she learned working on The Sneeze, Keegan used her senior project as an opportunity to try her hand at directing. Collaborating with community members and a local theater in Crested Butte, Colorado—a tiny ski town where she has close family ties—Keegan produced and directed Waiting for Lefty, an American classic she studied in one of Baker’s courses. “In many ways, I didn’t really know what I was doing at the time. But Jodi’s trust, and her encouragement to go try and figure it out on my own, was fundamental.”

Since that first foray into directing, she’s never looked back. Now based in London, Keegan has worked as an associate director, dramaturg, and accessibility consultant for almost a dozen productions at the National Theater and the Old Vic, including a 2019 revival of Arthur Miller’s All My Sons starring Sally Field.

The path has not always been easy. Shortly after leaving COA, Keegan enrolled in an intensive program for emerging directors. “They had us working for three weeks, no days off, 10 a.m. to 10 p.m. every day. My journey to identifying as having a disability began with that training.” Sharing her diagnosis of mild cerebral palsy with me during our interview,

she reflects, “I’ve had to constantly fight so hard to stay in the industry because it is not set up to be inclusive or accessible, in so many ways.”

Keegan knew that to continue working in theater, she needed to find a different model. This led her to the UK-based Graeae Theatre Company. According to their mission statement, “Graeae is a force for change in world-class theater, boldly placing Deaf and disabled actors center stage and challenging preconceptions.”

Training with Graeae not only brought Keegan back to London but also connected her with other companies, directors, and artists working at the intersections of theater, access, and disability justice.

Most recently, she collaborated with Sacha Wares, associate director of the National Theater’s Immersive Storytelling Studio, to mount Museum of Austerity, a virtual/mixed reality installation that explores the lived consequences of British austerity measures of the 2010s.

“One of my biggest roles for the show was as an access consultant,” says Keegan. “But I think Wares wanted me on the job because I’m not afraid to have honest conversations with her about the technology and to say, I don’t know. Let’s try and figure it out. What happens when we use the technology this way or that?” She continues: “Mixed reality is incredibly interdisciplinary—I think this project is the most human-ecological thing I’ve done since leaving COA.”

Keegan is specifically compelled by the questions that emergent mediums like virtual reality raise for artists and audiences alike: “One of the things that fascinated me working on this project is that this medium is so new, there aren’t any rules yet. So we need artists and writers and dramaturgs to be part of the development process.” Human ecologists, too.

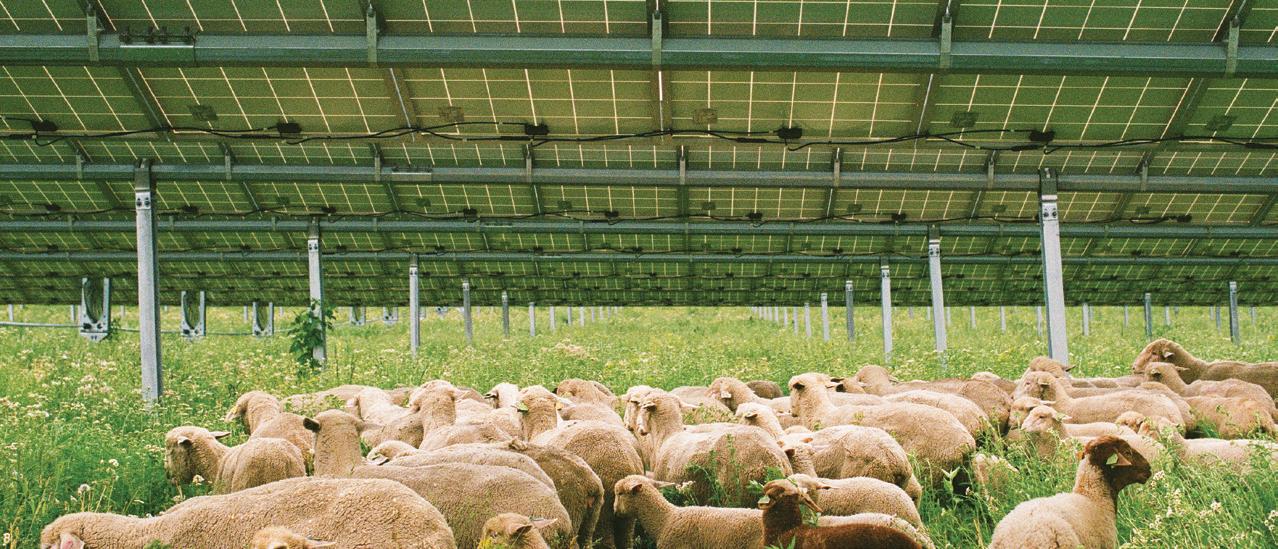

STILL DARK when Arlo Hark ’18 and Josie Trople ’18 start their morning. After breakfast and coffee, they call for their border collie, Frazey, and hop into their green 1994 Dodge 2500 pickup and set off. After driving for a bit through the vast cornfields of Northfield, Minnesota, the trio pick up their semi truck and quadruple-decker Merrit livestock trailer. As the daylight settles in, they arrive at their destination: a 30-acre solar array. Framed by a sea of shimmering photovoltaic panels, Hark and Trople set up a temporary corral while Frazey goes to work rounding up their flock of just over 100 Rambouillet sheep. The aluminum chute clangs as the flock loads into the trailer single file, from bottom to top. Hark cinches the doors and hitches up their 500-gallon water tank. With all of the flock accounted for, the team takes one last look around and heads off to their next gig.

couple have found themselves working in the burgeoning field of agrivoltaics, which fuses clean energy and animal husbandry. As Cannon Valley Graziers work to expand their flock and their range, so too is the United States working to expand the use of solar energy. Hark and Trople are on the cusp of something big.

Hark, Trople, and Frazey are Cannon Valley Graziers, a family enterprise specializing in adaptive livestock grazing and vegetation management. They’ve flipped the traditional grazing narrative of paying for access to land on its head; rather, they are paid for their sheep-powered landscape management services. While they started out aiming to apply their grazing methods to prairie and forest settings, the

The United States is poised to experience a solar installation boom, following the passage of the Inflation Reduction Act in August 2022 and the setting of ambitious carbon reduction goals for the next decade. The opportunities to incorporate novel agricultural practices such as solar grazing into this development are many. For young sheep farmers like Hark and Trople, the opportunity to earn a living while creating lasting positive impacts on the land around them is incredibly valuable. In a modern twist on an ancient relationship, humans and sheep are coming together as vehicles of ecological transformation and sustainability—an exciting prospect in this changing world.

“The land going into solar here in the Midwest has often been over-extracted through decades of conventional monoculture. There’s been a push from environmentalists and conservationists to incorporate native species for pollinator habitat, but there’s also a bunch of folks who really want to see the land stay in agriculture,” says Trople. “Sheep are an excellent solution.”

The two started their flock in 2018 with hopes of having a lasting positive impact on the ecology and soil health of Southern Minnesota while also providing food for their community. They dove into adaptive grazing while also generating lamb sales through local CSAs, coops, and restaurants. A year later, they came into contact with American Solar Grazers Association cofounder Lexi Hain, who helped them learn about and break into solar grazing. Since then, they have secured landscape management contracts with solar developers, getting paid for every acre their flock grazes. This year, they expanded their business with the launch of Bayl, a sustainable woolen goods company using hand-spun fiber from their flock.

Hark and Trople’s flock grew to just over 100 sheep this year, and Hark thinks that they can keep growing—a lot. With their business model, he says, they can multiply that number exponentially. The sites they currently graze range from 5 to 50 acres, but they both want to go bigger, hoping to graze sites as big as 1,500 acres with a massive flock of sheep.

“I’d like to be grazing thousands of sheep. Like five or ten thousand sheep on big sites,” he says.

The installation of large solar arrays can be controversial in rural communities, as it removes land from agricultural production, and can be perceived as an eyesore. Solar grazing changes that by keeping the land in agriculture, and, for some critics, the familiar sight of livestock grazing beneath the panels can change how they feel about a solar project in their county.

“Managing the vegetation on these sites is not only critical for the aesthetic, but also for the site function,” explains Hark. “In order to keep these sites operating safely and efficiently, good vegetation management plans are crucial. So what we are doing is using targeted grazing as a land management tool to meet very specific site objectives.”

When explaining their business model, Hark has found that some have trouble wrapping their heads around it. People cannot figure out how on earth these two young farmers have managed to flip the grazing narrative. What Hark tries to drive home to people is the ecological service they are providing. It’s landscape management, but with stacked benefits for the soil, pollinators, sheep, and people.

“Land access is one of the biggest barriers to entry in Minnesota. Young farmers generally have a really hard time finding land, which is one of the reasons that solar grazing is a great way to grow a profitable land management/livestock company,” Hark says.

Sheep are perfect for solar grazing both in size and behavior. Mowing under the panels requires expensive, specialized equipment, but sheep have no trouble fitting beneath the arrays. The sheep go through less water when grazing on solar sites; the panels provide shade for the sheep, keeping them cool on hot days. Solar grazing is a win for developers who save money when switching from commercial landscape management practices, which can cost more and can also have the potential to cause damage to panels.

The lives of sheep and humans have been tightly knit together in the Western world for thousands of years. Throughout history, sheep have served as potent cultural symbols, appearing in mythology and religion around the globe. Humanity’s wooly, four-legged friend has historically been vital to survival, producing food and fiber essential to existence, but sheep, as part of the portmanteau biota—a collective term used to describe the organisms Europeans brought to the lands they

The US is poised for record-breaking installation of solar and wind power as the government works on reducing carbon emissions by 50% by 2030. The US currently has 139 GW of solar capacity, enough to power 23 million homes. The Inflation Reduction Act set the stage for an increase of operational capacity of at least 40% over the next five years, with some organizations predicting as much as a threefold increase.

Both Hark and Trople come from agricultural backgrounds; Trople’s family raised cow and calf pairs and cut hay, while Hark grew up in Cannon Valley with his family’s small flock of sheep. The couple met at College of the Atlantic.

While at COA, Hark gravitated towards English and creative writing, studying poetry with writing professor emeritus Bill Carpenter and diving into music composition with former music professor John Cooper. Trople studied agroecology and field botany, taking classes in food anthropology and food systems. Trople spent the winter of her senior year in Spain with history and Latin American studies professor Todd Little-Siebold’s Cidra, Queso y Granjas: Agriculture’s Past and Present course, an intensive three-week, field-based exploration of the history and contemporary reality of Spanish agriculture. Both Hark and Trople have found their studies in human ecology to be very connected and intertwined with what they are doing now with Cannon Valley Grazers.

“Human ecology is at the core of solar grazing,” Hark says. “You have issues of land management, soil health, ecology, sustainable energy production, agriculture, and

colonized—have also been vehicles of destruction and colonization.

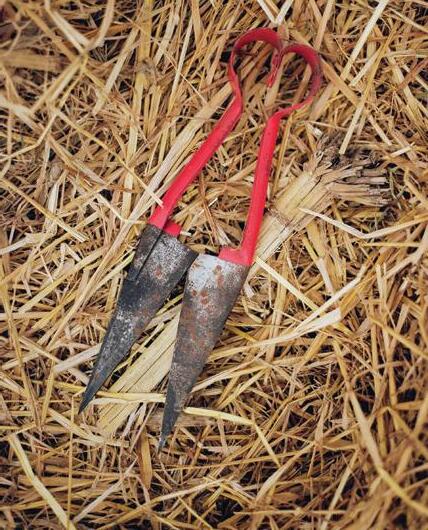

“There’s so much sheep, wool, and fiber arts symbolism woven into cultures at so many levels,” says COA Elizabeth Battles Newlin Chair in Botany Susan Lecher, who teaches Sheep to Shawl, a course on the human ecology of sheep. Lecher notes it’s difficult to talk about the symbolism without making terrible puns. “So much of the way we talk about the fabric of the universe, how

livestock. There are so many different touchpoints, so you really have to be able to think on a systems level in this work.”

Both Hark and Trople knew they wanted to do something related to agriculture in the midwest after graduation.

different bodies of knowledge are woven together, so many metaphors that we use to describe existence tie back to the arts of making textiles and cordage. In prehistory, a lot of those textiles were coming from sheep.”

Sheep are thought to be the first animal domesticated for food by humans 11,000 years ago. While they were initially domesticated for their milk and meat, around 6,000-9,000 years ago wooly sheep appeared and were rapidly selected for breeding because of their ability to produce fiber. It’s difficult to imagine sheep without the

fluffy wool coats they have today, and this development radically changed humanity, not just within humans’ relationship with sheep, but with the world.

“Through their wool, sheep also impacted the development of commerce and stock markets. A lot of what was traded was futures in wool. If you look at the history of economic systems and trade networks, much of it was initially built around wool production, wool manufacturing, and cloth production,” says Lecher, “Sheep are deeply tied to a lot of human history.”

During their senior year, an elder from Hark’s hometown of Northfield asked if they were interested in grazing an eight-acre piece of overgrown silvopasture. They jumped at the opportunity.

“There was this intention going into it that our animals would do something good for the land while we would also be producing food for our community,” says Trople. “Using animals to have a positive ecological impact on the land was important to our goals and what we wanted to do from the beginning.”

During their senior year, Hark and Trople pooled their savings and bought 20 lambs, sight unseen, off of Craigslist, sending a deposit through the mail. After graduating, they headed to Northfield, met their new flock, and began grazing on the land that had been offered to them.

Hark and Trople worked on small grazing projects all over Rice County, traveling scores of miles from their Northfield home with their flock. As they expanded their scope and pushed the boundaries of what they were trying to do, they started pitching their services to developers, sending emails, making cold calls. Their persistence has paid off.

Trople first became involved with fiber processing in 2019, when she and several other small producers from Minnesota and Wisconsin pooled their fiber to have it processed and made into socks to be sold at a fiber tour event. This gave Trople an opportunity to see what fiber processing looks like, and it felt like something she wanted to pursue. From then until the recent launch, Trople has been working diligently on feasibility studies and business planning for processing and using their fl ock’s fiber.

Trople has worked to incorporate traceability and sustainability into the business model, closely working with the few remaining domestic wool processors and using only natural dyes for Bayl’s garments. She is active in her involvement and understanding of the whole process, from shearing to processing, to garment making, labeling, and packaging. Each stage of the process is slow and thoughtful.

“I think it comes back to integrity,” says Trople. “There’s a lot out there that’s being marketed as ethical and sustainable. It’s important to me as somebody who’s producing the fiber—the first step—that the integrity follows through with every part of the process.”

Trople has been working towards launching a woolen goods company since 2020. This past December, her brand, Bayl, launched its first batch of heirloom-quality, utilitarian, gorgeous wool products.

“The products are designed to be worn by rural folks and farmers, but also for people who are interested in slow, ethical fashion,” says Trople.

Eva McMillan ’24 is a third-year student at College of the Atlantic. She wrote this article as part of an independent study in nonfi ction writing in fall 2022.

INA WAY, COA chose me before I decided on COA. I was adamant about not wanting to study in the US. In the US, education is something that people go into debt for; I did not want to support that system, and I couldn’t imagine living in a place that didn’t have free healthcare. I still feel this way. I have paid more for healthcare since being in the US than I have paid in medical fees for my entire life, and yet here I am feeling more

at home than I ever have. COA was, as dramatic as it sounds, a lifeline for me. It helped me out of one of the biggest struggles of my life. I was burned out and struggling with depression after working in healthcare during a global pandemic, and COA was the thing that made me get up again. After two years alone in an apartment in central Berlin— surrounded by people and yet incredibly lonely—I was longing for community, longing for the

intercultural exchange that I had experienced at United World College, and longing for a path that had more than one direction.

My fall term classes were the exact mix that I wished for before coming to COA; a science class, a writing course, and a course that cannot be put into a single subject group.

COA is my home now; a place I didn’t look for, but found me.

The Human Ecology Core Course was confusing, sometimes irritating, and other times wonderfully exciting. It made me want to learn more, it made me understand less, but it also allowed me to see there is a lot that goes into the work of understanding. I loved the fact that we had an opportunity to learn with so many different faculty members, even though sometimes the one-week intervals felt too short. I am looking forward to reading the first draft of my “What is Human Ecology” essay in four years and seeing if and how my perspectives have changed, who I’ve become, and how my perceptions of this place have grown.

My writing course with Palak Taneja, Amitav Ghosh and Climate Change, was an incredibly engaging academic experience. I still often think about passages I read in The Great Derangement by Amitav Ghosh and the discussions we had in that class. I wrote a ten-page paper about the failings of fictional media in regards to the climate change crisis, which was an eye opening research process. As someone who would love to write a book or two in my lifetime, understanding the power of fictional media is something I will hopefully never lose sight of.

DEPT/ID COURSE NAME

HS 5055 Tutorial:

Amitav Ghosh and Climate Change

HE 1010 Human Ecology Core Course

ES 1086

Introduction to Field Sampling

TALK about my experience at COA without mentioning buildings and grounds (B&G). When I got assigned to them through work-study I cried. I had been told that it was the worst work-study to have, and all I would be doing was shoveling snow. So, of course, I choose to include a picture of me on one of those shoveling days, but as you can see, there is very little misery in my expression. B&G has turned into my anchor on campus. The crew is like a quirky family to me. There is so much to learn from all of them and they are such incredibly kind, helpful, and funny human beings. I couldn’t be more grateful for all they have done for me at COA.

My Introduction to Field Sampling class was connected to the Human Ecology Achievement Program of the Sciences. We arrived on campus a couple weeks earlier than other incoming students and had the chance to take trips into the field and learn sampling techniques in a way that would have not been possible during the term. As an international student, it was a great experience to be able to participate in. Professor Reuben Hudson and teaching assistant Maddie O’Brien ’22 were an incredible team. I had so much fun learning from them. We had many excursions, but my favourite one was probably the day we spent at Little Long Pond taking core samples of sediment from a canoe platform. Analysing a sample that you have taken yourself and knowing exactly where it is coming from is an incredibly rewarding experience.

An interview with COA Spanish professor KARLA PEÑA, the director of Programas de Inmersión Cultural en Yucatán, COA’s hallmark language immersion program in México. Peña joined the full-time faculty this year after many years of running the program.

By Dan MahoneyHow does it feel to see these students immerse themselves in Yucatán culture?

TO ANSWER this question, I have to take you back to the beginning: the winter of 1999 when the students of COA and Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán met. They sat one in front of the other along with professors and administrators from both organizations. It was a moment full of magic; after one fall term of Spanish classes, our students were in Yucatán talking and interacting with huge smiles and bright eyes. The magic is still there after all these years, with each new group that embarks on this amazing immersion journey. Every year it reminds me that a positive attitude is the doorway to the destiny of your choice.

What is one of your favorite memories from Programas de Inmersión Cultural en Yucatán (PICY)?

THERE ARE TOO MANY to count, but here are two that come to mind:

In 2010, Don Francisco Canul Poot of Yaxunah was standing with his host son, COA student Stu Weymouth ’12. There were hugs and tears, because it was time for Stu to leave what had been his home and his family for three weeks. With sincere emotion and his heart in his hands, Don Francisco told me, “This is our son Stu. He looks a little different, but he is ours.” These relationships established through the hearts of the families and students last forever.

In February 2019, Iain Cooley ’21 couldn´t believe that after a basketmaking workshop, he could understand that when your basket is full, the only way to let something new in is by taking something out, just like in PICY´s immersion program. To be fully immersed, you have to empty out some things that you carry inside in order to let new things in. His presentation was a welcome reminder that the cultural immersion process is complex, fascinating, and demands personal growth.

What draws you back to COA year after year?

THE STUDENTS are the most important reason that I return to COA. Each one has their own history and so many talents to share. They are sources of never-ending inspiration and learning. We are all students and teachers at different times in our lives.

I really love the collaborative approach that comes with COA’s vision of a humanecological approach to learning, both in what it lets me do and in the kind of students it attracts and with whom I get to do it.

Student projects mix every kind of discipline and approach, from artistic studies of making jewelry with palm leaves, to puppet theater with children, to anthropological studies of cooking, farming, or gender differences, to scientific studies of arthropods or bird migration or fisheries conservation. So every day brings fascinating new adventures. Every student gives me an excuse to meet new people and explore new aspects of the people and culture of my own beloved Bella República de Yucatán.

How has PICY changed over the years, and what are your hopes for the future of the program?

AFTER 24 YEARS, the biggest change is the kind of students we see, although it is impossible to compare the different generations. PICY has always been a personalized program, tailored to each group and each student, so each year is different. Each time a student is able to broaden their perspective and leave their familiar surroundings, the motto Life Changing, World Changing rings true. I’m convinced that a broader approach to human ecology is a way of understanding the micro-universes within our societies, and PICY allows our students to change and adapt their worldview to include these interconnections.

As I always say in my classes, “Without context it is impossible to understand the text.”

The first generation of faculty who started the COA program in México are starting to be succeeded by others who are also interested in supporting students in a variety of ways. I very much look forward to collaborating with them as their Spanish skills improve and their knowledge of the area and connections and collaborations with people in Yucatán grow. The challenges of COVID-19 forced us to experiment with variations in ways we work with rural communities.

I hope we can continue to learn from those experiences, and push the limits of what is possible for giving students really accelerated and profoundly transformative experiences through immersion in language and culture. I also hope we can continue to develop the resources for supporting and sustaining our physical facilities and, even more importantly, the team of people who work with us in PICY. They include, for example, wonderful teachers like Raul Manzanilla, as well as incredibly effective administrative staff like Lucero Guttierez and logistics staff like Don Francisco.

COA Spanish professor and Yucatán program director Karla Peña, in red pants, with 2022-23 students; photo credit Enrique Solís.

COA Spanish professor and Yucatán program director Karla Peña, in red pants, with 2022-23 students; photo credit Enrique Solís.