50 minute read

Appendices

Appendix 1 – Center for Inspired Teaching consent form used in year 5 & 6 of Real World History.

Informed Consent & Copyright Permission for Oral History Interviews102

The Great Migration Oral History Project is a component of the Real World History Course (District of Columbia Public Schools course H72) run by the Center for Inspired Teaching. In order for the material provided by you to be deposited in the Great Migration Oral History Project Collection, it is necessary for you to sign this form. Before doing so, please read it carefully and ask any questions you may have regarding its terms and conditions.

I, ________________________________________, voluntarily agreed to be interviewed for the Real World History Great Migration Oral History Project. I understand that some or all of the following materials were collected/created as part of the interview process:

An audio and/or video recording An edited transcript, abstract, short analysis & reflection essay, and a tape log A photograph or other still image of me in my home or site of interview

I understand that this project is a class assignment for the Real World History class in which _____________________________ was a student during SY ______________. S/he conducted an audio and/or video recorded oral history interview concerning my participation in the Great Migration, the mass movement of African-Americans from the American South to the North and West during the period 1915 to 1970.

I herein freely share my interview and other material with the Center for Inspired Teaching and the Real World History Great Migration Oral History Project under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. This means I retain the copyright to my material, but that the public may freely copy, modify, and share these items for non-commercial purposes under the same terms if they include original source information.

102This consent form was adapted from online resources made available by the Southern Oral History Program at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

_______________________________________ _______________________________ Narrator Signature Interviewer/course instructor signature

_____________________________________ ______________________________ Date Date

_____________________________________ Street address

_____________________________________ City, State, Zip code

_____________________________________ Email

_____________________________________ Telephone

Please fill out two copies—one stays with the narrator and the other returns to Real World History instructor, Cosby Hunt at Center for Inspired Teaching. Should the narrator have any questions concerning their rights in this research initiative, they may contact Real World History instructors Cosby Hunt (202.412.9213 | cosby@inspiredteaching.org) and Max Peterson (603.412.2500 | Max@inspiredteaching.org).

Appendix 2 – Pre-interview Worksheet used in years 1-3 of Real World History

Your name: ___________________________________________________________________________________

Nameof the interviewee: ___________________________________________________________________

What is your relationship to the interviewee? ____________________________________________ Has the interviewee agreed to sign the release form and be recorded? Yes ____ No ____

S/he was born in the year ___________ . S/he moved to DC from _____________________________________________________ . How old was s/he when s/he came to DC? _________ The first place where s/he lived in DCwas ______________________________________________ . Will you be able to record the interview on your phone? Yes _____ No ______

Will you be able to conduct the initial interview before Thursday December 4? Yes ____ No_____

Where can you conduct the interview in person?*

*Your interviews must be done in person and recorded

Appendix 3 – GMOHP Narrator Identification Handout (2021-2022)

Real World History (H72) Identifying a narrator

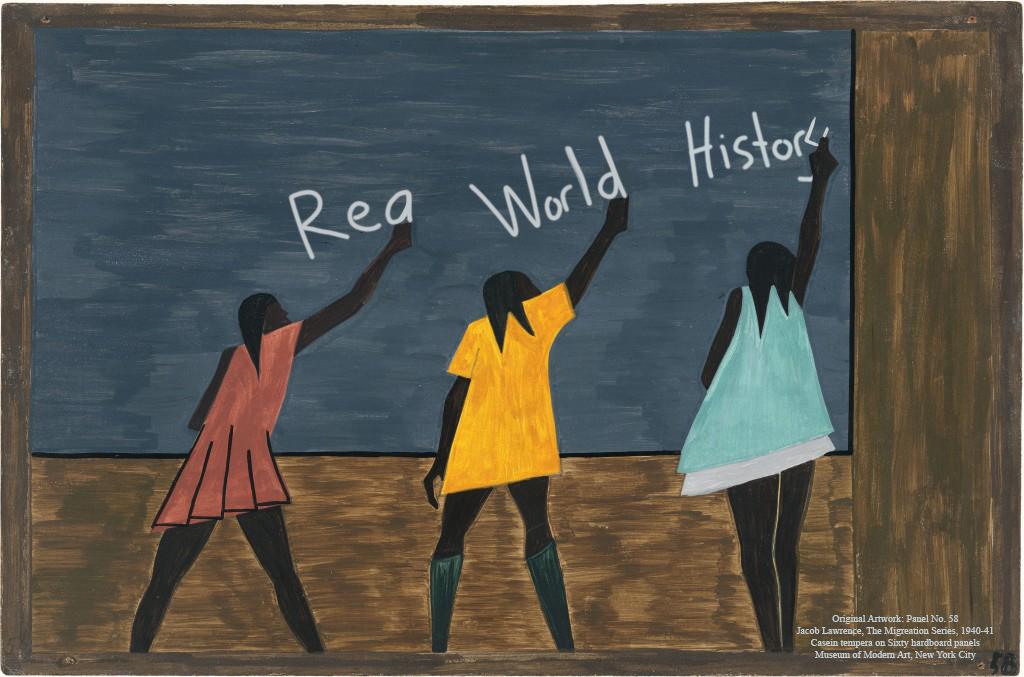

A group of RWH narrators on a field trip to see the Jacob Lawrence’s Migration Series

Welcome to Real World History! The fall semester of RWH will revolve around an in-depth study of the Great Migration – the mass movement of African American people out of the South to the North and West from 1915-1970. As part of this study, you will complete an oral history project with an individual who was a part of the Great Migration. This summer, as we prepare to embark on this semester-long project, you will need to identify the individual with whom you’ll collaborate throughout the fall. For some of you this will be as simple as asking a grandparent or great-grandparent if they would be willing to work with you on this project; for others, this will require a little more work.

Before class begins on August 31st, you must identify a Washingtonian who:

1. Was born and raised in the South 2. Moved to DC before 1970

If you don’t know someone who fits these criteria and you’re already beginning to panic about how you’ll identify a narrator, don’t worry; you’re not alone. We often hear from students that this is one of the more nerve-racking parts of the project.

So, why do we ask you, the students, to do this? There are several important reasons:

1) Real World History positions students as historians, and historians have to get out there, do the research, and engage the communities with whom they work. This process forces students to get out into the city and connect themselves with the people and organizations of their community. 2) Identifying their own narrator gives students a sense of ownership over the project and their collaboration with their partner from the outset. 3) Students have to practice important skills, such as giving a pitch to strangers, and gain experience and comfort conducting cold-calls and presenting themselves respectfully and professionally. 4) All of us are embedded in different communities throughout the city (not only different neighborhoods, but also different communities based on shared interests, belief systems, or common causes), and through our communities we all have access to different people.

Having students identify their own narrators creates a more diverse group of interviewees with individuals coming from a variety of neighborhoods, having a variety of careers and vocations, and representing different socioeconomic backgrounds.

Ideas about how you might want to approach recruiting a narrator.

First and foremost, start as close to home as possible. If there is no one in your family who fits the criteria, reach out to institutions in your neighborhood (churches, community organizations, etc.) where you may be able to find a narrator. Here are some of the ways students have found their narrators in previous years:

Asking parents, older family members, teachers, family friends and others to connect them to potential narrators in their networks Reaching out to community organizations they were a part of (such as their church, community garden, scouting troop, community sports league, etc.) Asking around at community gathering places such as a barber shop or hair salon (yes, two students have identified narrators this way!) Contacting civic organizations in their community (such as the Anacostia Coordinating

Council or Hillcrest Community Civic Association) Calling/stopping by local churches to ask if they might be connected with some who could serve as a narrator. Some churches students have worked with in the past are: o Asbury United Methodist Church o Shiloh Baptist Church o Greater Refuge Temple of Washington, DC o New Bethel Church of God in Christ o Vermont Ave. Baptist Church o St. Augustine’s Episcopal Church o National Presbyterian Church Reaching out to the DC Department of Aging and Community Living (DC DACL) Calling/stopping by local senior centers (such as Bernice Fonteneau Senior Wellness

Center in Petworth or Malta House in Avondale Terrace - Chillum, MD)

Before you begin reaching out to people, prepare a pitch that: 1) explains who you are, 2) explains what you are asking of them, and 3) outlines the project.

As you approach potential narrators, you should not be trying to convince anyone to participate in the project if they are not interested. A successful oral history interview requires a genuine willingness to participate. Without the buy-in of the narrator, your oral history interview is going nowhere, fast.

Here is a loose formula you can use to design your pitch:

Hello, my name is [your name]; I’m a [10th/11th/12th] grader at [your high school] and I’m

seeking some help with a project for my history class. Do you have a moment to talk?

I’m part of an after-school history class called Real World History in which I’m studying

the Great Migration and DC history. The Great Migration was the mass movement of

African Americans from the South to the North during the 20th century.

As part of my class, I need to conduct an interview with a Black/African American

person who moved to DC from the South before 1970. Is there anyone at your [church,

organization, group, etc.] who might be willing to work with me on this project? If so,

could you please give them my contact information: [your name, phone number, email]

If you’re leaving a message, before hanging up make sure to (slowly and clearly) reiterate your name, your school, and your contact information.

Once you have identified an individual who fits the profile and is willing/available to participate in the project:

Complete and submit the Narrator Identification Form

Inform your narrator that your teacher will be following up with more information about the project!

Appendix 4 – GMOHP Overview (2021-2022)

Real World History (H72) Great Migration Oral History Project

Real World History students with their narrators after recording an oral history interview.

The Great Migration Oral History Project is the focus of the fall semester of Real World History and is designed to put students’ learning about the Great Migration and their skills as historians into practice. Over the course of the fall semester, you will collaborate with a Black Washingtonian to record an oral history interview about that person’s life and experiences moving to DC from the Jim Crow South. While research and preparation will be vital for this project, a successful oral history requires that you develop a working relationship of trust and familiarity with your narrator. Thus, in addition to developing your historical thinking skills, this project will help you cultivate important interpersonal skills that are transferable to other forms of community engagement. Through this project you will: Gain experience analyzing primary and secondary source material Become familiar with 20th century American, African American, and DC history Learn how to conduct oral history interviews Gain archival research skills and learn about archival preservation Create and archive your own primary source: an oral history interview with someone who was a part of the Great Migration

You will be doing the work of a historian actively documenting the experience of the Migration, but the work of the historian does not end with information-gathering. As a class, you will share your findings and knowledge with the DC community. First, the oral history you and your narrator record will be archived at the DC Public Library and made fully accessible to the public on Dig DC; Then, together as a class, you will organize and facilitate a public event about the impact of the Migration at the DC Public Library, stimulating discussion about the meaning of this history to the DC community.

What is the Great Migration, and why are we studying it?

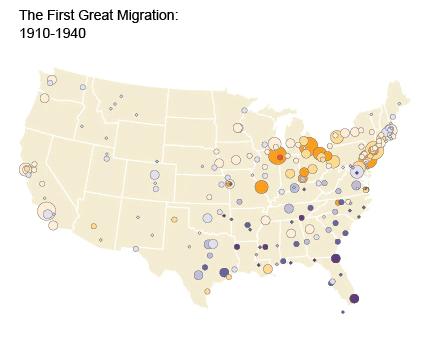

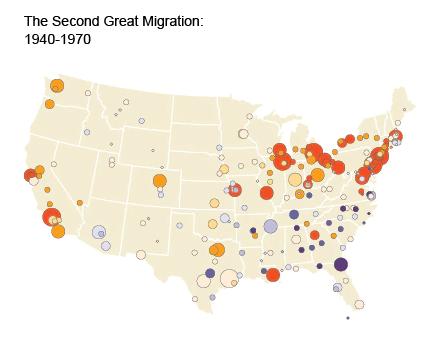

The Great Migration was a massive migration of African Americans from the American South to cities in the northern and western United States. From beginning to end, roughly six million African Americans migrated out of the South. When the Migration began in the 1910s, 10% of African Americans were living outside the Southern U.S.; by its conclusion in the 1970s, nearly half of Black America (47%) lived outside the South! In recent scholarship, the Migration is divided into two periods: the first Great Migration (19151940) & the second Great Migration (1940-1970). Though we will study the Migration in its entirety, through the oral history project we will be recording the history of the latter half of the Migration and how it was experienced in Washington, DC. The Great Migration completely altered the demographic landscape of this country and redefined the modern American city. The DC you know is a product of this history in terms of politics, language, music, food and even the physical layout of the city. Together, you and your narrator will explore this transformation.

Source: “The Great Migration, 1910 to 1970,” United States Census Bureau, September 13, 2012, https://www.census.gov/dataviz/visualizations/020/.

What is oral history, and why will we be conducting interviews?

Oral history is the transmission of history or knowledge from one person to another through narrative and storytelling. This knowledge is usually, though not always, transmitted orally.103 For the purposes of this project, we can think of oral history as people’s recollection and retelling of their first-hand experience of history. Oral history has many different uses, but one of the primary reasons that historians turn to oral history is to understand the human experience of history and the ways that people make meaning of their past. In an oral history interview these two processes are interconnected as the narrator is both recalling and interpreting their past experiences for future listeners. Another common reason that historians record oral history is to fill in gaps and omissions in our understanding of the past. The histories of women, people of color, working-class people, queer communities, etc., have not traditionally been as well documented by professional historians. Beyond that, much of what was recorded about marginalized groups and communities was not created with their input nor inclusive of their perspectives. We’re turning to oral history for our study of the Great Migration for two main reasons: 1. As a leaderless movement spanning six decades, the Migration is a story of everyday people. Oral history interviews allow us to understand this larger history by exploring how it played out in the context of one person’s life. 2. Oral history interviews allow for migrants’ understanding of their own migration experience to take central focus. This focus allows us to see how individuals relate memory and personal experience to a broader collective experience, and thus, how a collective experience starts to become history. Informed by the structure of our main text, Isabel Wilkerson’s The Warmth of Other Suns, your interview will touch upon the following themes: 1. Life in the South 2. Migration 3. Life in the North 4. Retrospection and reflections

103 For example, people who communicate through American Sign Language (ASL) do not transmit their “oral history,” orally. For this reason, oral history is referred to as narrative or story history in ASL.

Project timeline & assignments:

(*** = assignment will have a separate assignment sheet)

Sep. 2nd (Thurs) – Narrator identification form submitted*** At our first in-person class session, students will submit a form with contact information for their narrator. Each student is responsible for identifying their own narrator for the oral history project. Sept. 16th (Thurs) – Narrator-student field trip to Phillips Collection Class will gather at the Phillips Collection to explore Jacob Lawrence’s Migration Series with their narrators. The course instructors will then discuss the oral history project with the group, answer any questions narrators/students may have, and the evening will conclude with the first pre-interview discussion between students and their narrators. Sept. 21st (Tues) – 250-300 word narrator bio completed*** Based on their preliminary discussion at the Phillips, students will write a brief biographical sketch of their narrator. Oct. 5th (Tues) – Interview timeline prepared. Based upon pre-interview discussions with narrators as well as course reading, each student will populate a timeline with biographical information and historical events relevant to their interview. This timeline will serve as an important reference during the interview. Oct. 26th (Tues) – Interview index & abstract complete*** Students will produce an index which divides their interview up into short intervals along with an accompanying summary (brief) of the topics discussed and a list of questions posed. Nov. 4th (Thurs) – Set of interview questions prepared. Students’ questionnaires should have at least 3-5 open questions for each section of the interview: 1) Life in the South, 2) Migration, 3) Life in the North, 4) Retrospection and reflections. Dec. 2nd (Thurs) – Oral history interview complete Students will record an oral history interview with their narrator (minimum duration: 45 minutes). Dec. 14th (Tues) – 10min of interview transcript complete Jan. 4th (Tues) – Interview transcript complete*** Each student will transcribe (type up, word-for-word) the entirety of their oral history interview. Expect roughly six hours of transcription for each hour of audio. Jan. 18th (Thurs) – Final assignment complete*** Each student will complete a final assignment engaging/analyzing their oral history interview as a primary source. Students may elect to complete an analysis/reflection paper, multimedia piece, or an artistic piece with an artist’s statement. These final products will be on display at the end-of-the-year public event.

May – Public event with narrators at DC Public Library Throughout the spring semester, the class will organize a public event about the significance of the Great Migration to Washington, DC. Students will facilitate a roundtable discussion between their narrators about the meaning of the Migration to the DC community.

Appendix 5 – GMOHP Narrator Identification Form (2021-2022)

Real World History (H72) Great Migration Oral History Project Narrator Identification Form

Your name: ___________________________________________________________________________

Name of the interviewee: ________________________________________________________________

When & where were they born?

When did they move to DC?

How old were they when they came to DC?

What was the first place they lived in DC

What is your relationship to the interviewee?

PHONE:

EMAIL: Narrator contact information

Appendix 6 – GMOHP Narrator Information Packet (2021-2022)

Real World History

Thanks for your interest in working with a Real World History student on their Great Migration Oral History Project! Please take a moment to read this information about the project and the Real World History program. This packet will address the following questions: What is Real World History? Who are the teachers? What is the Great Migration Oral History Project about? What is an oral history interview? What should I expect if I agree to work with a Real World History student?

What is Real World History?

Real World History is a year-long after-school history class open to high school students in DC public and public charter schools. With the goal of bringing history to life for young Washingtonians, the class introduces students to the field of history as something people “do,” not memorize.

Real World History has two parts: In the fall, students do a deep-dive on 20th century DC history and the impact of the Great Migration on Washington. As part of this study, students record an oral history interview with someone such as yourself who made the move to Washington from the South before 1970. In the spring, students are placed in internships at museums and historic sites in DC and compete in the National History Day competition. They also organize a public event about their oral history project at the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Library (DCPL) in May.

Who are the teachers?

Our names our Cosby Hunt (left) and Max Peterson (right), and we’re co-teachers of Real World History. Cosby Hunt is a high school teacher here in Washington. A native Washingtonian, he began his teaching career in the District in 1997 at Bell Multicultural High School. He currently teaches history at

Thurgood Marshall Academy in Anacostia. In the fall 2014, he founded the Real World History program and has been teaching the class ever since. He is married and has two sons (12 & 14). Max Peterson works in the Oral History Initiative at the National Museum of African American History and Culture, and has co-taught Real World History with Mr. Hunt since the fall of 2017. He was born and raised in New Hampshire, and has lived in DC since 2017. He is recently married and lives in Anacostia.

The District has changed tremendously over the decades, and it continues to change, fast. The city that young Washingtonians are growing up in today is quite different from the Washington of the 1990s, let alone the 1960s.

How better to get students plugged into the history of their city than to have them talk to older people in their community? In this project, students learn about the past and present of Washington by focusing in on one important aspect of DC history: the movement of Black people from the South to the DC region in the 40s, 50s, and 60s. This influx of

people was part of larger movement now called the Great Migration in which six million Black Americans moved out of the South to cities in the North and West between 1915-1970.

Throughout the fall, students study the Great Migration by reading The Warmth of Other Suns by Isabel Wilkerson and work with someone like you who made the move from the South to Washington, DC, before 1970 to record an oral history interview about the experience moving to DC from the South.

If you decide to participate in this project, you will have the opportunity to review your interview and decide whether or not to have it archived at the DC Public Library in the Real World History Collection.

What is an oral history interview?

Unlike a journalistic interview, an oral history interview centers on people’s recollection and retelling of their life experiences. In other words, oral historians are interested in the stories people tell about their lives. Oral history interviews have the long-term goal of being archived and made accessible (in full) to future generations. This means that interviewers usually take a broad look at an individual’s life starting with their family and upbringing. This helps future listeners get a better sense of the person talking. This style of interviewing often means that the interviews are long, but most Real World History interviews do not exceed an hour. The narrator, or the person being interviewed, has much more control in an oral history interview. Topics of the interview are usually discussed in advance and developed collaboratively between interviewer and narrator. Interviewers ask open-ended questions that prompt the narrator to elaborate on personal experience. Names, dates, and facts are not usually the focus of oral history interviews. After the interview, the narrator is consulted about how the interview can be used, and whether or not it is to be archived.

What should I expect if I agree to work with a Real World History student?

The oral history project will take place in stages between September and January. If you agree to work with a student this fall, there are two things that we ask you to commit to: 1) That you join us for a field trip to the Phillips Collection on September 16th to see Jacob Lawrence’s Migration Series and talk about the oral history project. 2) That you sit for a 45-minute to 1.5-hour oral history interview with the student sometime in November. This meeting can take place wherever is most comfortable for you. The interview may take place at your home, a public library, the interviewer’s school, etc. The student will audio record the interview, so the location should, ideally, be fairly quiet. Through pre-interview discussions, you and the student will work together to decide what topics will be discussed in the interview. The basic structure that we encourage the students to follow (based on our main text, Isabel Wilkerson’s The Warmth of Other Suns) is as follows: 5. Upbringing/life in the South 6. Move to Washington, DC 7. Life in Washington, DC 8. Retrospection and reflections

After the project is done, the students will begin organizing a public program about the Great Migration for the DC Public Library. The event will take place in May at the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Library, and we invite you to participate in the event, if you are interested and available.

At the program, students will facilitate a roundtable discussion between narrators about the meaning of the Migration to the Washington DC community.

Project timeline:

Sept. 16th 4:30-6:00pm (Thurs) – Narrator-student field trip to

Phillips Collection Class will gather at the Phillips Collection to explore Jacob Lawrence’s Migration Series with their narrators. Over dinner, the course instructors will then discuss the oral history project with the group, answer any questions narrators/students may have, and the evening will conclude with the first pre-interview discussion between students and their narrators. Nov. – Dec. – Students & narrators record oral history interviews Students will record an oral history interview with their narrator (minimum duration: 45 minutes). May – Public event with narrators at DC Public Library Throughout the spring semester, the class will organize a public event about the significance of the Great Migration to Washington, DC. Students will facilitate a roundtable discussion between their narrators about the meaning of the Migration to the DC community. Fall 2022 – Interviews are archived by the People’s Archive of the

District of Columbia Public Library and made publicly accessible via Dig DC.

Questions?

Contact Cosby Hunt at Cosby@inspiredteaching.org or 202-412-9213

Appendix 7 – GMOHP Narrator Bio (2021-2022)

Real World History (H72) Narrator Bio

One of the first steps to your oral history project is to write up a short bio (biography) containing basic information about your interviewee’s life from childhood to the present. In order to write this bio, you will need to gather biographical information through pre-interview discussions with your narrator. The narrator bio should be a brief and broad-strokes summary of the interviewee’s life. This bio does not need to be too intensive, but it should be at least 300 words. Two sample narrator bios can be found below. Writing a narrator bio has several purposes:

1) It will provide an opportunity for you to develop familiarity and trust with your narrator. 2) This information will guide further background research as you prepare for the interview. 3) Biographical information is vital for developing appropriate interview questions. 4) The bio will be featured in the catalog record of your interview to introduce the narrator.

Your first pre-interview discussion will take place during our field trip to the Phillips Collection, but you will need to coordinate subsequent conversations with your narrator. During these preliminary conversations, make sure to cover basic information such as:

Their full name When and where they were born Basic information about their family (such as the names and occupations of parents, how many siblings they had, etc.) and where they grew up. What schools they attended Places the narrators has lived When and why they moved to Washington, D.C. Their chosen occupation, profession, vocation, career, etc. (Note: If your narrator does not work in wage-economy, this does not mean that they do not “work.” Indicate their occupation(s) whether or not they are paid for their labor) Their passions and hobbies Any important events, turning points, or milestones in their life. You can ask about common life events, such as when they met their partner or spouse (if they have one) or when their children were born (if they have any), but make sure to ask your narrator to identify any important moments/events in their life.

After you’ve had your conversation, ask if they have a photograph of themselves that they would be willing to share with you, OR if they are willing to let you take their picture. Remember, if your narrator does not want to share a photo with you, that’s totally fine!

Once you’ve written the bio, share it with your narrator for their review.

Appendix 8 – GMOHP Index and Abstract Project

In this assignment you will review an oral history interview from last year’s class, create a timed index of the interview, and write an interview abstract. While this project is an important listening activity for the class and will serve as the basis for class discussion, there is a practical purpose to this assignment as well. As you know, by the end of the semester you will have written a narrator bio, recorded an oral history interview, and created an interview transcription. But, for an interview to be archived at the People’s Archive of the DC Public Library, it must have all of the following: 1) A signed consent form 2) A narrator bio 3) An interview summary 4) A complete interview transcription 5) And a timed interview index Through this project you will produce the final materials for one of your peer’s interviews, allowing for it to be archived and made publicly accessible. Next year, another Real World History student will do the same for your oral history project. An interview index is a document that divides an audio recording into short intervals of time and features a brief (2-3 sentence) summary of the topics discussed in each interval. Indexes increase the accessibility of audio recordings since they help researchers quickly navigate to specific sections of recordings while conducting research. The timed sections featured in your index should reflect shifts in the discussion and do not need to be a uniform interval of time. As you’re listening to the interview and reading the transcript, make a note of the points where the conversation takes a turn or there is a shift in focus. Moments such as these will indicate where you will want to begin a new section in the index. In case it is helpful to be able to physically mark the transcript, everyone will be provided with a hard copy of the transcript for their interview. Each timed section featured in the index must be accompanied with: a brief summary of the topic of discussion, and a list of the questions posed during the section. These short summaries do not need to include the details of what is discussed (the reader can listen to the audio or consult the transcript for the that). Instead, try to identify the topics and themes being discussed by the narrator.

Once you’ve completed the interview index, it’s time for the final piece of the interview, the abstract. An interview abstract is a one-paragraph summary of the contents of the oral history that identifies the key themes and topics addressed in the interview. Abstracts are incredibly important since they often are used by researchers to make quick decisions about whether or not an interview is relevant to whatever it is they are investigating. Below you will find a sample of an interview index with commentary. A properly formatted template will be provided to you before you begin the assignment.

Appendix 9 – In-class Interviewing Lesson Plan

Real World History (H72) In-Class Interview

Materials:

Oral history interviews from the Real World History collection

Learning objectives:

Prepare interview questions informed by preliminary research (class readings and archival listening) Cultivate interviewing skills through interview critique and practice with close listening and posing follow-up questions Learn how to operate recording technologies Develop a more conscientious approach to working with their narrator by listening to a narrator reflect on their experience of working with a Real World History student

Overview:

To provide more face-to-face interaction between students and narrators, people who have been Real World History narrators in the past will join class (one guest at a time) for in-class interviews and discussion. Guests will spend an hour with the class (5:30-6:30pm) to allow for time to prepare and debrief. The in-class interviews will build upon the oral history interviews in the Real World History collection and serve as an opportunity to practice both archival listening skills and the listening skills required during an interview. Before the in-class interview, students will be assigned the archived oral history interview with the narrator and will develop interview questions based on their listening. Students will also be asked to identify what they feel are the strengths and weaknesses of the interviewer’s approach which will serve as the basis of a class discussion with the class guest about their experience in the interview.

Homework:

- Class listens to the narrator’s archived oral history interview in preparation for their visit. Narrators will also be asked to listen to their interview in preparation for class. - Students prepare/identify: At least two questions that they would like to ask the narrator derived from the interview. At least one thing they think interviewer did well in the interview (interviewing strategies/tactics, listening skills, etc.). At least one thing they felt the interviewer could have improved upon.

Procedure/activity:

Before the class guest arrives, instructors discuss the purposes of the in-class interview and explain how the interview will function.

- The instructors will leave the questioning to the class. - One student will manage the recording technology (if narrator has agreed to be recorded) - The narrator will call upon students to ask questions. - After any prepared question is posed to the narrators, the class must ask two follow-up questions or a prepared question which can be directly connected to the topic, before another prepared question can be asked.

The class guest joins class for an in-class interview and discussion. Part 1 (30min): Students are given the opportunity to pose questions to the class guest (alternating between prepared questions and un-prepared follow-up questions). Part 2 (30min): Instructors facilitate a conversation between the class and the class guest about the guest’s experience working with a Real World History student. Together the class and the class guest will discuss what the student did well, what they could have improved upon in their collaboration with their narrator, and what advice the narrator has for the students as they work with their narrators.

Follow-up: Short term

(If recorded) Instructors will review the recording and will use excerpts of the recording as the basis for class discussion.

Long term Instructors will compile a document with narrator’s feedback on their interview experience.

Appendix 10 – Peer Interview Project

Real World History (H72) Peer Interview

Materials:

Timeline template “Helpful Hints for Oral History Interviewing” by Amy Starecheski

Learning objectives:

Learn more about a classmate’s life experiences through an oral history interview Prepare interview questions informed by preliminary research Practice relationship building and historical contextualization Develop interviewing skills through practice and reflection Learn how to operate recording technologies Develop empathy through reflection on the experience of the narrator in an oral history interview

Overview:

To provide students with the opportunity to act as both interviewer and narrator in an oral history interview, students will collaborate with a classmate to record a 20-minute oral history interview. Students may record their interviews remotely or in-person, but they should try to interview their partner in the format in which they plan to interview their narrator. This interview can focus on a specific topic/experience or take the form of a life history interview. This assignment will also allow students to practice having pre-interview conversations with their narrator as they prepare for their interview. During a preliminary meeting (during class time) students will discuss the topic and approach of their interview and prepare an interview timeline with their partner. After conducting the interviews student will write a 1-page reflection about the experience of both interviewing someone and being interviewed. These reflections will serve as the basis of classroom discussions about interviewing and the experience of the narrator. Students will then share their reflection with their partner and have time to debrief with one another. Since this project has the dual purpose of providing the class with study materials for the final exam, the fact that their classmates will have access to these interviews must be emphasized when introducing the assignment. Students may request that their interview not be shared with the class.

Procedure/activity:

- Divide the class into pairs (avoid pairing students with someone from their school) and hand out timeline sheet (one per student). - Re-introduce the interview timeline and discuss its purposes. Then, as a class, brainstorm a list of events/collective experiences that have taken place during the students’ lifetime (online - in shared Google doc. In-person - on board).

- Give students 30 minutes of breakout time to have a preliminary conversation with their partner and indicate that they should: 1) Decide which events (from class discussion) they want to put on their timeline. 2) Talk over basic biographical information and get to know each other. This conversation should be used to add additional information to each student’s interview timeline. 3) Discuss whether or not they wish to focus on a particular topic/experience or take a life history approach. Remind students that they should ask their partner if there are any topics they do not wish to discuss in the interview. 4) Coordinate a time to do their interview in the coming days.

- When student return from the breakout, share and review the handout, “Helpful Hints for Oral History Interviewing,” and explain homework.

Homework:

- Record a 20-minute life history interview with their partner. Interviews should be submitted to the instructors via Dropbox (create folder and provide students with link). - After the interview, write a short (1 page) reflection about the experience of interviewing/being interviewed. Provide the following questions to guide student reflections: (Students do not need to answer all questions.) How did it feel to be interviewed? How did you feel beforehand, during, afterward? How did it feel to be the interviewer? o What was easy/difficult, and why? o What do you think worked well, and why? What didn’t work so well, and why? What did you notice about yourself as an interviewer? What did you notice about yourself as a narrator? What did you notice about your partner as an interviewer? (Be specific.) What did you notice about your partner as a narrator? (Be specific.) How did the knowledge that the interview was going to be shared with your classmates affect you as a narrator? Were you to be interviewed again, what might you do differently? What might you do differently when interviewing your narrator? Do you think you successfully established trust and familiarity in your pre-interview discussions? Why, or why not? What might you do differently next time?

Follow-up:

Short-term - After interviews/reflections have been submitted, use recordings/reflections as the basis for a classroom discussion about the experience of both interviewing and being interviewed. Reflection questions can be used as discussion questions in class. - Each student will then read their partner’s reflection and have breakout time to debrief as a pair.

- Instructors will gather all materials in a Dropbox folder so students can use the collection as study materials for the “US!” section of the final exam. Long-term - Throughout the fall, the instructors will pull clips from peer interviews for classroom critique and discussion of interviewing strategies.

Appendix 11 – GMOHP Interview Transcription Project (2021-2022)

“I didn’t really get all of the things she told me in the interview until I began the next part of the project, the transcript.” – RWH student, 2019-2020

Now that you’ve completed an oral history interview with your narrator, it’s time to transcribe the interview! An interview transcription is a written document that represents (word-for-word) what was communicated in an interview.

Thoughtfully and intelligently transcribing an oral history interview is a difficult and timeconsuming task, and your interview transcription should not be taken lightly. It is safe to expect 6+ hours of transcription for every hour of recording depending on the audio quality and your typing ability.

Transcription is often looked upon as a chore, but it is one of the most important aspects of your oral history project as it increases the accessibility of your interview. For someone who is deaf or hard of hearing, an oral history without a transcription can be completely inaccessible. On top of this, transcripts increase the interview’s accessibility for everyone by providing a written companion that can be referenced while listening to the interview.

It is also much easier to navigate through a written document than an audio file. Oral histories are long, and most people don’t have the time to sit down and listen to them in their entirety. The average person will only selectively engage with your interview in its original form by listening to the sections that interest them.

The written text of your interview transcription is the medium through which most researchers will engage with your interviewee’s oral history narrative. Since most people will be reading your transcription instead of listening to your narrator directly, you must portray your narrator’s words with as much accuracy as possible and stay true to what they were trying to convey. A successful interview transcript not only conveys the narrator’s words, but it also captures the spirit of the encounter and gives the reader a sense of the narrator’s speech patterns – the cadence and tempo of their speech and how they construct sentences. As a transcriber you will (at times) need to make slight edits to assist the readability of the interview as a written text and to ensure that your narrator’s intention is effectively translated. “Translated” may be confusing in this context since your interview will be conducted in English, but as you begin your transcription you will notice the ways in which oral communication does not translate neatly into a readable written text. We transmit thoughts and meanings quite differently orally than we do in written language. Below you fill find transcription guidelines and a sample of a transcript with commentary.

Real World History transcription guidelines:

Work with a copy of the original recording when transcribing.

Listen to the recording fully before beginning the transcription. This will greatly help your ability to understand your narrator and transcribe the interview. Listening to the interview will familiarize you with the voices on the tape, patterns of speech, and the questions being asked.

Formatting – Please use the transcript template as it is properly formatted for you. If you choose to create a new document, format the document as follows: o Margins: 1” margins. o Font: Times New Roman, size 12. o Spacing: double spaced, no spacing before or after lines. o Indentation: .5 first-line indent for each speaker. o Page numbers: top right. o Header: Narrator’s name, bolded, aligned left.

Properly fill in basic information about the interview on the title page: 1) Narrator’s name; 2) date of interview; 3) duration of recording; 4) interviewer’s name; 5) interviewer’s high school.

Identify all speakers’ full names (all caps, followed by a colon) the first time they appear in the transcript. Subsequently, speakers should be identified by their last name. If speakers share the same surname, include the narrator’s first initial.

Create a word-for-word transcript but omit crutch words/phrases such as "um/uh,” “like,” and “you know.” That being said, these crutch words/phrases can remain in the transcript if: 1) their removal would make the narrator’s thought confusing, or 2) their inclusion indicates something important to the reader that would not be conveyed were they omitted. For example, inclusion of “um” or “uh” could help indicate to the reader that the narrator was struggling to find the right word to describe something. You also should eliminate false starts.

When a narrator is quoting someone or recalling something someone said, use quotation marks. Grammar note: Always begin quotations with a capital letter and place punctuation inside the quotes. When a narrator is recalling/quoting their own internal through process, you should also use quotation marks. If a narrator has a quote within a quote, use apostrophes to demarcate the quote within the larger quotation. For example:

PETERSON: I remember Mr. Hunt saying to me, “January is usually when I start getting

the emails from students saying, ‘I didn’t think the transcript would take so much time.’ ”

Nonverbal sounds should be noted and in (parentheses). Some examples of these nonverbal communications are: (laughs), (chuckles), (winks), (groans), (grins), (smirks), (claps), (taps on table), (snaps fingers), etc.

o (Laughs) when speaker laughs o (Peterson laughs) when someone other than the person speaking laughs o (Laughter) or (both laugh) when the speaker and other participants laugh.

Avoid editorializing. I.e. (laughs), not (laughs rudely). When these occur at the end of a sentence or a clause, position them after the punctuation.

While you will, at times, need to break up your narrator’s speech with punctuation to assist the readability of the transcript, try to avoid such arbitrary punctuation as much as possible. For example, run-on sentences should only be closed by a period when it is reaching the point that it will be difficult for a reader to follow the narrator’s thought.

Sentence fragments should be left as is. EM dashes followed by a period (—.) can be used to indicate an incomplete or unfinished thought. Commas may be used to reflect pauses in the narrator’s speech. If a there is a significant pause, insert (pause) in parentheses.

Correct and [bracket] grammatical errors if they are an obvious error of speech. But, if non-standard grammatical structures are a part of your narrator’s speech patterns, ask your narrator how they would like their speech reflected in the transcription. Though we’re aiming for the most accurate portrayal of the individual's speech, our ultimate responsibility is to represent our narrators as they wish to be presented. Some of your narrators may want the transcript edited to reflect standard grammatical structures.

Titles of books, films, songs, etc. should be formatted according to the latest edition of the Chicago Manuel of Style. The Purdue Online Writing Lab has a helpful guide to

Chicago Style Citation.

Preserve chit-chat to indicate the formality or informality of the interview session.

In order to reflect the tone of the interview, vulgar responses and explicit language should be retained in the transcript unless the narrator instructs you to omit or edit the words/phrase/section.

Do not use ellipses (. . .) in your transcription. This will suggest that material was omitted from the transcript.

Note the need for additional information, such as first names, dates, definitions of technical, obsolete, or slang terms. Add information using footnotes at the bottom of the page

If there is an interruption in the interview recording, timestamp the moment the recording was paused and indicate the interruption as follows:

[00:38:46 – Pause in recording]

Format the notation in the center of the page as seen above. Also provide a brief explanation about why the interview was interrupted. For example:

[00:38:46 – Pause in recording. Interview interrupted by phone call]

For any words/phrases that you are unable understand or are uncertain about, ask for someone else to give it a listen. A second opinion goes a long way! If it still cannot be deciphered, underline the section and insert two question marks in [brackets] followed by a timestamp. For example:

COHEN: On, uh, Georgia Avenue, I believe it was. He had a record shop called Earl B’s

Record Shop [??] [0:23:40].

Doing this ensures that the reader is aware that what is in the transcript is the transcriber’s best guess at what was said and not necessarily the narrator’s words. Indicating the timing of such sections allows the reader to navigate to that exact moment in the interview if they wish to double check what you have transcribed.

Share your transcription with your narrator after it is complete. Always respect the narrator's right to review and make changes to the transcript, but note such edits using [brackets] and footnotes.

Appendix 12 – GMOHP Final Assignment – Analysis & Reflection Paper (2021-2022)

Real World History (H72) Interview Analysis & Reflection Paper

The goal of this assignment is for you to reflect on your experience as an oral historian and to analyze your oral history interview in light of what you’ve learned about the Great Migration.

This paper should take the form of a reflection. Where does your interviewee’s story fit into the history of the Great Migration? And what did you learn about history itself through oral history interviewing? This assignment will require thoughtful reflection on, and analysis of, your interview as well as the class text: The Warmth of Other Suns by Isabel Wilkerson.

Your reflection essay should contain three connected elements/discussions: 1) The historical context of your oral history (the history of the Great Migration),

2) your interviewee’s migration experience, and

3) your experience collecting oral history.

The paper can be organized however you see fit, and the topics are interconnected, but we suggest starting with an analysis of your interview in the context of what we’ve learned about the Great Migration and concluding with a reflection on the process of oral history collection.

When discussing your interview and the Great Migration, use your transcript to pull quotes from your interviewee that connect to points you are trying to make. In your paper, you should discuss at least three quotes from your interview (note that quotes will not count toward the word count).

Organizing your ideas:

In this assignment, you will need to refer to The Warmth of Other Suns as well as Jacob Lawrence’s Migration Series while thinking about your interviewee’s story, but the most important piece of this exercise is your analysis and reflection.

To start, you should consider the following questions and make notes about them: The Great Migration & your interviewee How does your interviewee fit into the story of the Great Migration? Does their story reinforce what you’ve learned about the Great Migration? Contradict it? Or both? In what period of the Migration did they move? What was the larger historical context going on around them at that time? What was their experience in the South like, and what were their reasons for leaving? How did they adjust to life in Washington, DC? What did you learn that surprised you most? What was your thinking about the Great Migration going into this project? How has your understanding of the topic changed or evolved through your oral history? What questions were raised for you? What insights have you gained? What was the impact of your interview on your understanding of the Great Migration? How does your interview shed new light on the topic? What are some similarities and differences between your interviewee’s migration story and the stories of Ida Mae Brandon Gladney, George Starling, and Robert Foster? Think about their reasons for leaving, the time period, their education, their gender, their economic opportunity, their family and family history, etc.

Oral history methodology What did you learn from preparing and conducting this interview? Think about the process in its entirety - from finding an interviewee to finishing the transcript What did you learn from the process itself, from participating in this oral history assignment? What did you learn from your conversations and interactions with your interviewee?

Talk about the interactions you had with your narrator (i.e. the Phillips Collection field trip, phone conversations, your interview.) What was that relationship like? What did you find particularly striking about this experience? What are some things you noticed about your interview while transcribing? How did you, as the interviewer, affect the interview? In reviewing your transcript, do you recognize any of your own biases? How did conducting your interview in this historical moment affect the interview? What surprised you about yourself during this process? How did this experience affect your interest in history?

Make notes in response to these questions. Organize these notes into the key points you would like to make in the paper. Your paper should address the two broader topics outlined above (the Great Migration & your interviewee and Oral History Methodology), but you do not need to address every question. Focus on what is most interesting/important to you.

Write an introduction which captures your thinking about the Great Migration and history before you engaged in this project and what your expectations were. Describe and explain aspects of the experience which had the most effect on you. Mention what struck you most about this experience.

In your conclusion, discuss what you see as the strengths and weaknesses of oral history as well as how your feelings about history have been affected by participating in this oral history project. What did you expect, and how was the actual experience different? How have these experiences affected your interest in history? What concerns did it raise? What was affirmed for you?

Length and formatting requirements: Word Count: 750 – 1250 words (double spaced)

Citations: Chicago style. Chicago is the standard for historical writing, and it is what you will be using in your NHD projects this spring. Below you will find a model for the three sources you will need to cite in this assignment.

1) The Warmth of Other Suns

First footnote:

Isabel Wilkerson, The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration (New York, NY: Random House, 2010), [page #s] Subsequent footnotes: Wilkerson, The Warmth of Other Suns, [page #s] Bibliography: Wilkerson, Isabel. The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration. New York, NY: Random House, 2010.

2) Your Oral History Interview

First footnote: [Name of narrator – first name, last name], Oral history interview conducted by [your name –first name, last name], [Interview date], Center for Inspired Teaching ‘Real World History’ Oral History Project, People’s Archive, District of Columbia Public Library, Washington, DC, transcript, [page #s] Subsequent footnotes: [Name of narrator – first name, last name], Oral history interview conducted by [your name –first name, last name], [Interview date], transcript, [page #s] Bibliography: [Name of narrator – last name, first name]. Oral history interview conducted by [your name –first name, last name], [Interview date]. Center for Inspired Teaching ‘Real World History’ Oral History Project, People’s Archive, District of Columbia Public Library, Washington, DC.

3) Lawrence’s Migration Series

First footnote:

One-Way Ticket: Jacob Lawrence’s Migration Series, Museum of Modern Art, 2015, online exhibition, [Panel #], [URL]. Subsequent footnotes: One-Way Ticket, Museum of Modern Art, [Panel #], [URL]. Bibliography: One-Way Ticket: Jacob Lawrence’s Migration Series. Museum of Modern Art. 2015. Online exhibition. [URL].

Appendix 13 – GMOHP Final Assignment – Creative Assignment (2021-2022)

Real World History (H72) Creative Assignment & Reflection Paper

Art can be a means of conveying history to the public, just look at Jacob Lawrence’s Migration Series. The goal of this assignment is for you to translate your learning about the Great Migration into an artistic piece based on your oral history interview. This could take the form of a painting or drawing, a persona poem or a found poem, a short story, a monologue, a short audio or video piece using selections of the interview, a collage, etc.

To accompany your piece, you will need to write an artist’s statement and a reflection. In the artist’s statement, you should discuss the piece, your process of creating it, and explain the connection to your oral history interview. When discussing the inspiration for your artistic production, use your transcript to pull quotes from your interviewee that connect to points you are trying to make. If the piece is based on a particular section, include the whole section as a block quote (note that quotes will not count toward the word count).

In the reflection, you should discuss what you have learned about the Great Migration through your oral history project. Think about your understandings of the Great Migration and history as a field of study before you engaged in this project and what your expectations were. Describe and explain the aspects of the experience of working with your narrator and doing oral history that had the most effect on you. What did you learn about history itself through oral history interviewing?

The statement and the reflection should be in separate sections, but each can be organized however you see fit. The total word count for both pieces combined should be a minimum of 500 words, not including quotations from your interview.

Organizing your thoughts & creating your piece:

As long as the piece is connected to your oral history interview, you have a lot of freedom with this assignment. The piece could be inspired by the interview as a whole or based on a specific story told by your narrator. It could also be inspired by something more specific, such as a particular thought, a vivid description, or an exchange between you and your narrator.

To start, think about what part of the interview stood out to you. What do you most remember? What struck you most? What were you left thinking about?

Once you have identified those moments, think about what drew you to them. Was it the narrator’s words, was it the visual image the words evoked, was it the performance of how they expressed something, was it the rhythm or musicality of their speech... these are all clues as to how you might best represent this artistically. Remember that the material you are drawing inspiration from is someone else’s stories and memories. You want to honor that and think about how your narrator would want to be represented. Remember also that these will be displayed at the public event in May. Try to focus in on something manageable that you can do well within the allotted time. Often a more focused project is more impactful than one that tries to do too much. This assignment is not intended to be onerous. For example, if you want to do an audio or video production, aim for a three-minute piece at the most. Here are some ideas for different formats of artistically presenting your oral history interview:

1. Short Story or scene: Take a page out of Isabel Wilkerson or Edward T. Jones’s book and try your hand at creating a short story narrative based on part of your interview. 2. Persona poem: Write a poem in the voice of your narrator 3. Found Poem: Arrange your narrator’s words into a poem by lifting quotes from the interview. You might repeat quotes or phrases for effect. 4. Visual art: In the tradition of Jacob Lawrence, create a visual representation of some aspect of this history to which your narrator’s story connects. 5. Multimedia piece: This could be a short video or audio piece about an aspect of your narrator’s story. One example of an audio piece based on an oral history interview with

Mr. Hunt can be found here.

These are only suggestions. Let your content (what you would like to convey) suggest the form that your art needs to take. If you like, please feel free to discuss your ideas with the instructors.

Writing your reflection:

Use these questions to guide your thinking as you prepare to write your reflection. You do not need to address every question. Organize your notes into the key points you would like to make and focus on what is most interesting/important to you.

Your learning about the Great Migration What was your thinking about the Great Migration going into this project? What did you learn that surprised you most? How has your understanding of the topic changed or evolved through your oral history? What questions were raised for you? What insights have you gained? What was the impact of your interview on your understanding of the Great Migration?

Experience of oral history interviewing What did you learn from preparing and conducting this interview? Think about the process in its entirety - from finding an interviewee to finishing the transcript What did you learn from your conversations and interactions with your interviewee? What are some things you noticed about your interview while transcribing? How did you, as the interviewer, affect the interview? How did conducting your interview in this historical moment affect the interview? What surprised you about yourself during this process? How did this experience affect your interest in history?