Introduction to Part I

They put flowers on tombs and warm the Unknown Soldier. But you, my dark brothers, no one calls your names.

—Léopold Sédar Senghor, “To the Senegalese Soldiers Who Died for France”

Testimony by victims and survivors of Nazi persecution who were of African descent is relatively scarce. Nonetheless, a number of individuals did document their experiences either during the war or retrospectively. While some produced poetry, paintings, and drawings in the camps as acts of what the Holocaust historian and curator Miriam Novitch calls “spiritual resistance,” after the war others gave newspaper or oral history interviews or published memoirs.1 Focusing on artistic forms of testimony, part 1 of this book identifies two genres of creative expression in particular that have preserved Black wartime memories: internment camp art and survivor memoir. The internment camp paintings and drawings discussed in chapter 1 record in a condensed and encoded fashion possible only through a visual medium African diaspora perspectives that are largely unavailable in the textual archive of World War II. For their part, the Black European survivor accounts examined in chapter 2 illustrate the capacity of memoir, as an unusually democratic and accessible literary genre, to expose blind spots in mainstream historiography. Both genres of testimonial art document quotidian experiences of Black individuals in wartime Europe that defy received narratives of the past. They record what Campt in her analysis of Black German oral histories calls the “monumental minutiae”

of daily life. Much like Campt’s oral history interviews, through their emphasis on the quotidian, the visual diary and memoirs that I discuss in part 1 bring to the fore “questions that we frequently overlook or that often get obscured in our desire to explain the larger overarching social and political systems.”2 Yet as vehicles of wartime memory, artworks are distinct from oral histories in harnessing the particular affordances of their aesthetic media. Accordingly, part 1 establishes a joint focus on the mnemonic force of art and on auto/biographical genres of artistic representation that will be sustained through the second half of this book. Moreover, part 1 introduces two further interlocking themes that will carry through part 2: the relationship between artistic activity and wartime survival, and practices of self-invention among African diaspora people in wartime Europe.

In 2010, the Senegalese statesman and writer Léopold Sédar Senghor (1906–2001) was identified by the historian Raffael Scheck as the author of an anonymous June 1942 POW report. After pursuing his studies in Paris and teaching at a lycée in Tours, Senghor had been called up in September 1939 to serve in the 3rd Regiment of the Colonial Infantry. Upon the capture of Senghor’s unit in 1940, the Black soldiers were separated out by the Germans and lined up to be shot—a fate they only narrowly avoided by calling out “Vive la France! Vive l’Afrique noire!,” inspiring a French officer to intervene on their behalf.3 Senghor’s hitherto unknown seven-page report describes the difficult conditions subsequently experienced by his unit and the roughly one hundred thousand other colonial troops who were imprisoned in Frontstalags (POW camps) in the Occupied Zone of France after the German invasion in 1940.4 In unadorned prose, Senghor’s report offers an orderly, empirical account of a variety of facets of the Frontstalags in Poitiers and Bordeaux in 1940–1942, including their governance, housing, clothing, food, relations among prisoners, and prisoner morale. Yet as remarkable as it is, as a record of the wartime internment of colonial troops—a memory that would subsequently be suppressed in France for some seventy years—Senghor’s report cannot match the mnemonic force or emotional power of his POW poetry.5 During his two-year imprisonment, Senghor composed a series of poems that were later included in his 1948 collection Hosties noires (Black Hosts). The poems, many of which include the date and location of their composition, eulogize his fellow Tirailleurs Sénégalais while simultaneously recording Senghor’s own wartime experiences of fear, loneliness, humiliation, and intellectual awakening. In his POW poems, Senghor gives voice to the colonial soldiers discussed by Paul Gilroy who fought on Europe’s battlefields during World War II and there became “black witnesses to European barbarity.”6

Hosties noires displays a prescient preoccupation with monuments, memorialization, and the problem of invisibilization.7 The opening poem of Senghor’s

collection, dated 1940, expresses the speaker’s rage at France’s failure to recognize the sacrifices made by colonial soldiers (the Black sacrificial “hosts” of the book’s title). Simultaneously foreseeing and resisting the erasure of the role of France’s colonial troops in World War II, the speaker of the poem refuses to allow the “scornful praise” of “government ministers nor / generals” to “secretly bury / you.”8 Instead, he defiantly appoints himself the caretaker of their memory:

Who can praise you if not your brother-in-arms, your brother in blood,

You, Senegalese soldiers, my brothers with warm hands, Lying under ice and death?9

In “Camp 1940,” written in the Amiens camp (Frontstalag 204) in Nazi-occupied France several months after his capture, Senghor portrays the despairing French colonial troops as motherless baby birds:

We are small birds fallen from the nest, Drooping bodies without hope, Beasts with clipped claws, soldiers without weapons, Naked men.10

The praise poem “Taga for Mbaye Dyôb,” composed in Frontstalag 230, near Poitiers, memorializes a humble Senegalese soldier “Who lay down under the bombs of the giant vultures.”11 Throughout Hosties noires, Senghor employs the flexible line length and emotional intensity of the verset stanza form to convey the depths of the colonial POWs’ despair, their traumatic suffering on European soil, and their profound sense of betrayal by the colonial mother country— by “France that is not France.”12 The poems produce countermemories of World War II through liturgical motifs and visceral sensory images such as that of Frontstalag 230 as “a village crucified / By two pestilential ditches” and populated by colonial internees “haunted by the fleas of care / And the lice of captivity.”13 The potency of these countermemories resides less in their mimetic value—in the factual details they convey—than in their emotional and psychological poignancy. Much as will be the case with the larger body of testimonial and postmemorial artworks discussed in this book, the mnemonic force of Senghor’s POW poems— their capacity to lodge themselves in the reader’s mind and by extension in collective memory—stems from their aesthetic and affective qualities.

While my focus in Black Lives Under Nazism is on Black civilians rather than soldiers, I have dwelled briefly here on Senghor’s moving POW poems because

they illuminate both the countermemorial potency of art and the relationship between artistic creativity and wartime survival that will be central to my discussions of internment art in chapter 1 and survivor memoir in chapter 2. Alongside Josef Nassy’s visual diary of musical and artistic activity in Ilag VII and John William’s autobiographical account of discovering his singing voice while incarcerated in the Mal Coiffée prison in 1944, Senghor’s POW poems suggest the importance of art making as a survival strategy for Black prisoners in the Nazi camp system. At the same time, the relative neglect of Senghor’s POW poems visà-vis his other literary works is illustrative of the larger problem confronted by my corpus: the illegibility of Black European wartime experience and the consequent lack of attention that artworks documenting or imaginatively reconstructing the experiences of Black victims of Nazi persecution have received.

Both the relationship between art making and wartime survival and the problem of invisibility also emerge as themes in the life and career of the Caribbean jazz trumpeter Arthur Briggs (1901–1991). Briggs, who was imprisoned for four years in civilian internment camps in France during World War II, provided inspiration for the jazz novels that I will discuss in chapter 3. Now largely forgotten, he was well known in the interwar European jazz scene and performed with such jazz luminaries as Django Reinhardt, Coleman Hawkins, and Josephine Baker.14 Shortly after Briggs’s liberation from the Saint-Denis internment camp in 1944, an article in the Chicago Defender described him as “reputed to be the best trumpet player in Europe . . . who achieved fame in practically every European capital.”15 First arriving in Europe in 1919 with the Southern Syncopated Orchestra, Briggs went on to perform across the continent throughout the 1920s and ’30s with various groups including Noble Sissle’s orchestra and the Hot Club de France, which he helped found in Paris in 1932.16 In the early 1930s, Briggs developed a close collaboration with the African American jazz pianist Freddy Johnson, who would subsequently be interned in Nazi Germany alongside the artist Josef Nassy.

Briggs addressed his own internment experience during a six-hour oral history interview conducted in the early 1980s.17 In the interview, he described his arrest in Paris in 1940,18 brief detention at Compiègne (Frontstalag 122), and subsequent transfer to the Saint-Denis camp for Allied civilian internees, where he remained a prisoner until August 1944. Briggs’s friend, the jazz pianist Tom Waltham, petitioned the Germans to move Briggs from Compiègne to Ilag Saint-Denis (Ilag is an abbreviation for Internierungslager, or internment camp), where, according to Briggs’s account, Waltham led a thirty-piece orchestra but “didn’t have satisfaction with the brass or the trumpets because they were more or less amateurs.” After his transfer, Briggs joined Waltham’s orchestra and also formed a vocal

trio with Nigerian and Black British internees.19 Briggs recounts that upon arriving at Saint-Denis, he was able to negotiate with a German officer for better food in exchange for playing the Reveille for the camp. Moreover, if musical activity aided Briggs’s material survival during his internment, it also provided spiritual sustenance and a means of resistance. Briggs recalled that during a visit by the Nazi general and military commander of Paris Karl-Heinrich von Stülpnagel, he defied the Nazis’ view “that everything that was not Caucasian . . . was a monkey or something” by performing Beethoven, which earned him a salute from the general and a handshake from the aide de camp. The daily orchestra rehearsals helped Briggs withstand the difficult conditions of his internment, as did more secretive jazz sessions in the prisoners’ rooms. 20 At the end of each camp concert, Briggs would play a song on his trumpet that covertly communicated a message of solidarity to the other internees.21 Thus, as reported in the Chicago Defender, “The orchestra became a source of much happiness and comfort to the 2,000 internees of the camp.” Another source of solace was a theater that the prisoners constructed out of Red Cross boxes and cigarette tins. It was decorated by the artists in the camp, the most skilled of whom (according to Briggs) “was a colored man.”22

Art and music making are, of course, important facets of the history of Nazi internment and concentration camps more generally. Yet these biographical details from Briggs’s internment experience point to a particular relationship between artistic activity in the Nazi camp system and the presence of prisoners of African descent. A significant proportion of the Black civilian prisoner population consisted of entertainers, musicians, writers, and artists. During their internment, they were able to draw on the resources of their respective art forms to help sustain them through their ordeal. Moreover, as chapter 2 will make clear, not only Black expatriates in wartime Europe but also many German and French people of African descent who were persecuted or imprisoned by the Nazis were also involved in the entertainment industry. Briggs’s oral history interview thus establishes a crucial relationship between art, performance, and survival for Black people in Europe during World War II that will play out across the chapters of this book.

While Briggs’s story of survival and creativity resonates with those of other historical figures addressed in this study, as we will see in chapter 1, it exhibits particular parallels with that of the artist Josef Nassy. Like Briggs, Nassy emigrated in the early twentieth century from the Caribbean first to the United States as a teenager (where he arrived in New York one year after Briggs in 1918) and then to Europe seeking career opportunities and a refuge from American racism. Both men married Belgian women, both decided to remain in Europe when the

war broke out, and both were interned as enemy aliens as a consequence. Much as Briggs performed music in Ilag Saint-Denis, which sustained him both materially and spiritually through his captivity, so Nassy painted and drew throughout his three-year internment in Ilag VII in Bavaria. Yet perhaps the most striking point of resemblance between the two men’s stories is that both men passed as African Americans. At the beginning of his 1982 oral history interview, Briggs states his place and year of birth as Charleston, South Carolina, in 1899 and his parents’ hometown as Grenada, Mississippi. In fact, Briggs was born on the island of Grenada in the British West Indies in 1901. The pattern of emancipatory emigration, fluid identities, strategic self-fashioning, versatility, resourcefulness, and survival that emerges in Briggs’s biography is one that repeats across the lives and careers of many of the figures discussed in this book, including John William, Hans J. Massaquoi, Valaida Snow, Jean-Marcel Nicolas, Tatjana Barbakoff, and especially Josef Nassy.

“Sarah Phillips Casteel’s beautifully written Black Lives Under Nazism offers a startling new account of the memory of World War II and the Holocaust that centers Black artists and writers. Moving from internment camp art and memoirs by historical eyewitnesses to the novels, photography, and dance of later generations, this book reveals how certain histories are rendered invisible while simultaneously showing us the power of art and literature to reanimate the forgotten past and decolonize hegemonic perspectives. Black Lives Under Nazism is a fascinating work of recovery and a strong argument for a relational approach to memory.”

—Michael Rothberg, author of The Implicated Subject: Beyond Victims and Perpetrators

“Casteel’s rich, imaginative, and compelling study seeks to make visible the Black experience of the wartime period. Through a deft analysis of a diverse range of Black testimonial and creative work, she brilliantly illustrates the limitations and possibilities these offer in creating countermemories of the Holocaust.”

—Robbie Aitken, coauthor of Black Germany: The Making and Unmaking of a Diaspora Community, 1884–1960

“The experience of people of African descent in the Third Reich has been hauntingly absent in the public imagination of the Holocaust. With this penetrating and sophisticated study, Casteel illuminates the lived histories of Black victims and survivors of the Nazi regime, thereby expanding the canon of Holocaust representation.”

—Erin McGlothlin, author of The Mind of the Holocaust Perpetrator in Fiction and Nonfiction

“Casteel provides an in-depth analysis of a largely unknown corpus of Black African diaspora artworks and literature that address Black lives under Nazism. By making this corpus visible, this book illuminates the complex relations of Black and Jewish experiences in World War II Europe and challenges extant scholarship in Black and Holocaust studies.”

—Chigbo Arthur Anyaduba, author of The Postcolonial African Genocide Novel: Quests for Meaningfulness

SARAH PHILLIPS CASTEEL is professor of English at Carleton University, where she is cross-appointed to the Institute of African Studies, and a member of the Holocaust Educational Foundation’s Academic Council. Her most recent books are Calypso Jews: Jewishness in the Caribbean Literary Imagination (Columbia, 2016) and the coedited volume Caribbean Jewish Crossings: Literary History and Creative Practice (2019).

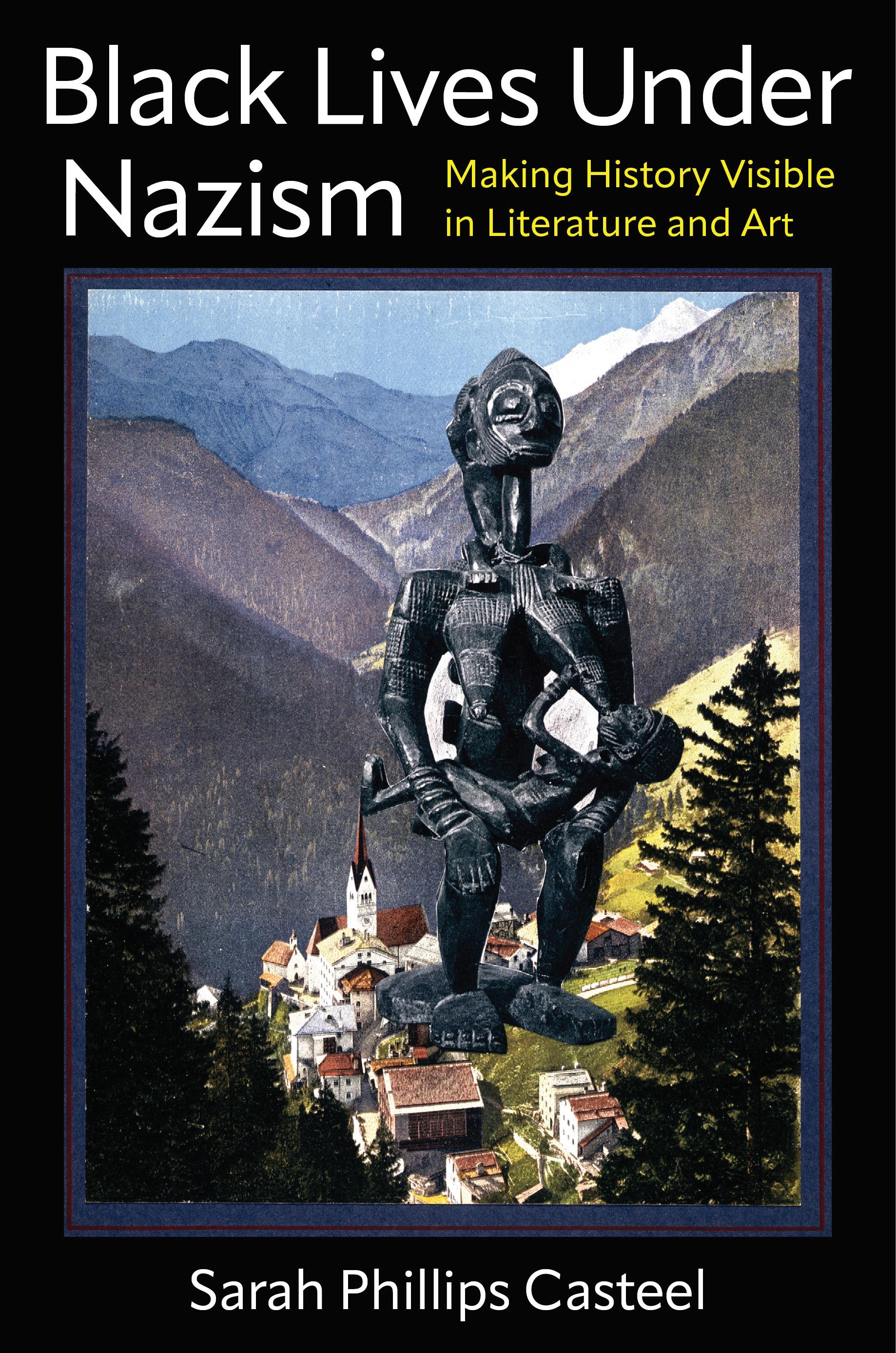

Cover design: Milenda Nan Ok Lee

Cover art: Maud Sulter, Noir et Blanc: Un. From Syrcas (1993).

Columbia University Press | New York

PRINTED IN THE U.S.A.